Submitted:

10 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

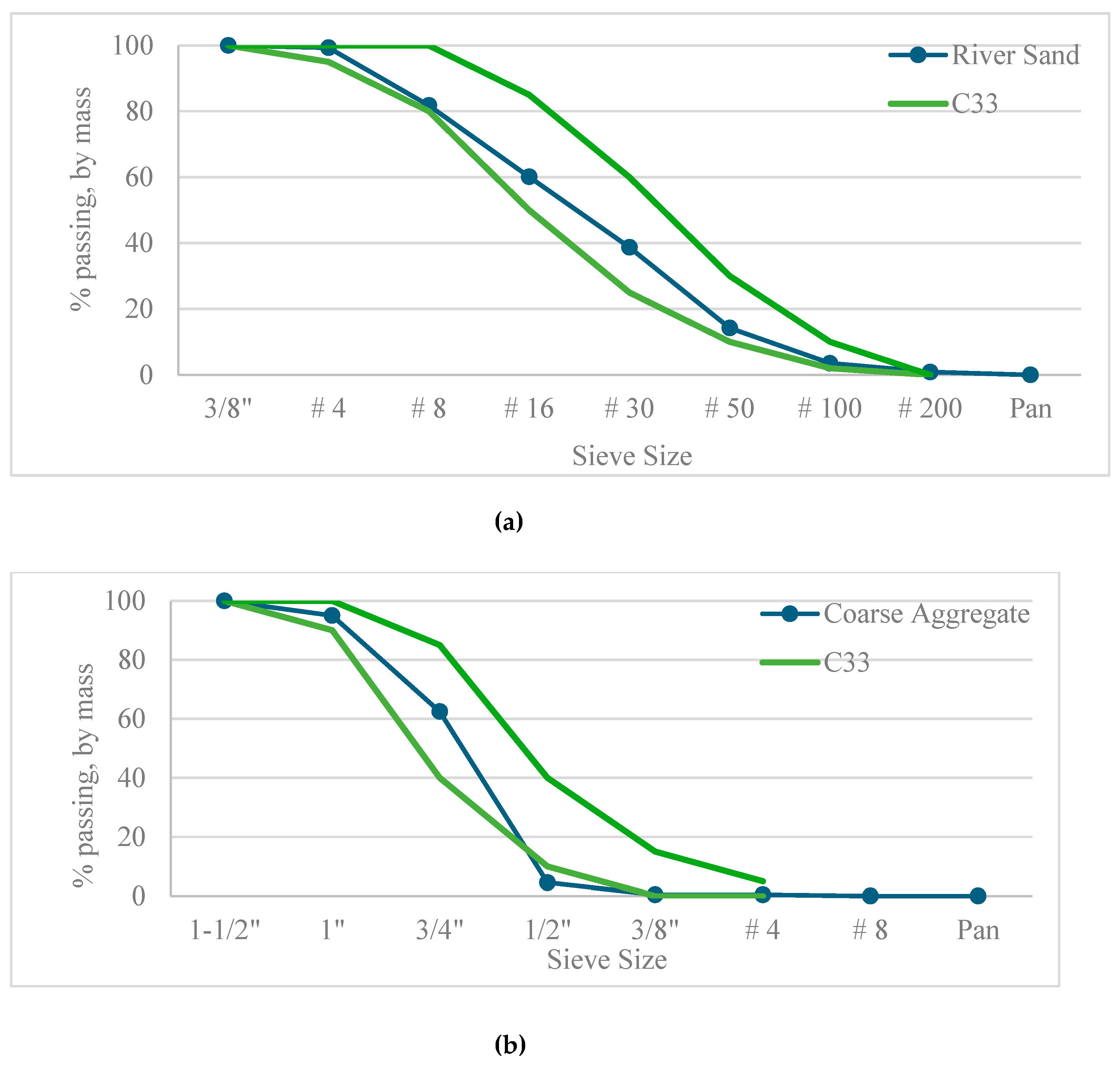

2.1. Materials

2.2. Laboratory Tests

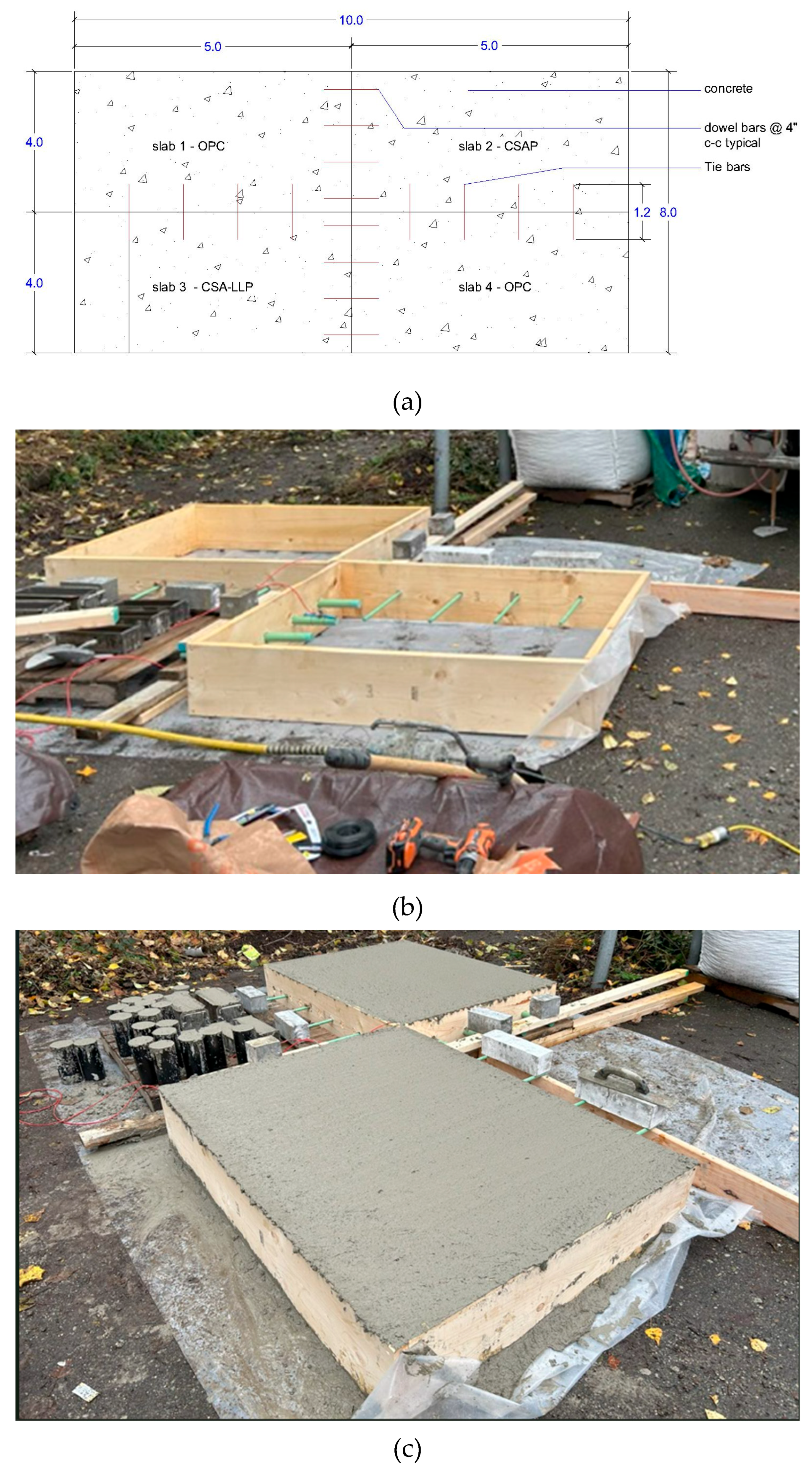

2.3. Outdoor Exposure Tests

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fresh Concrete Properties

3.1.1. Workability

3.1.2. Air Content

3.1.3. Initial Temperature

3.2. Mechanical Properties

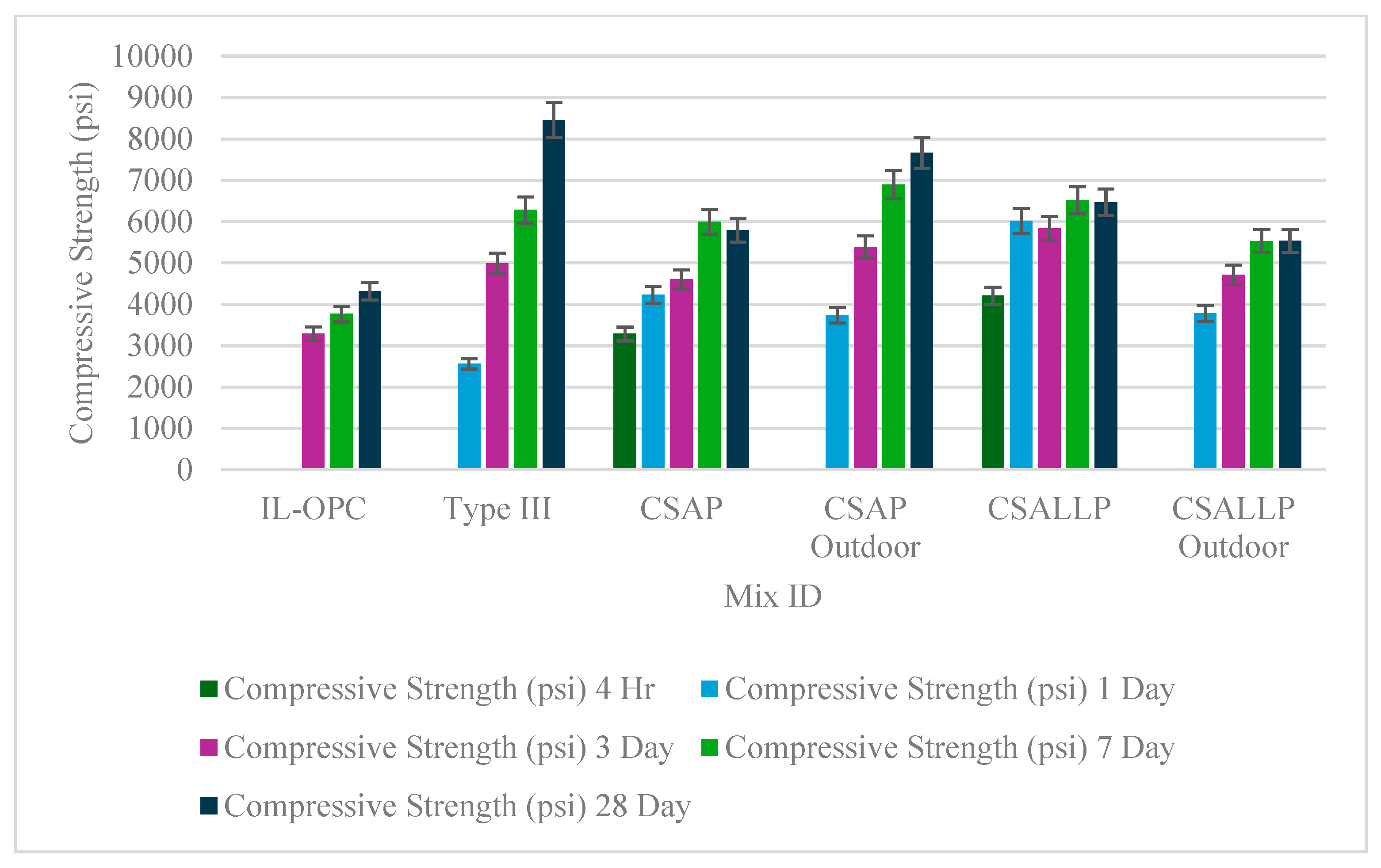

3.2.1. Compressive Strength

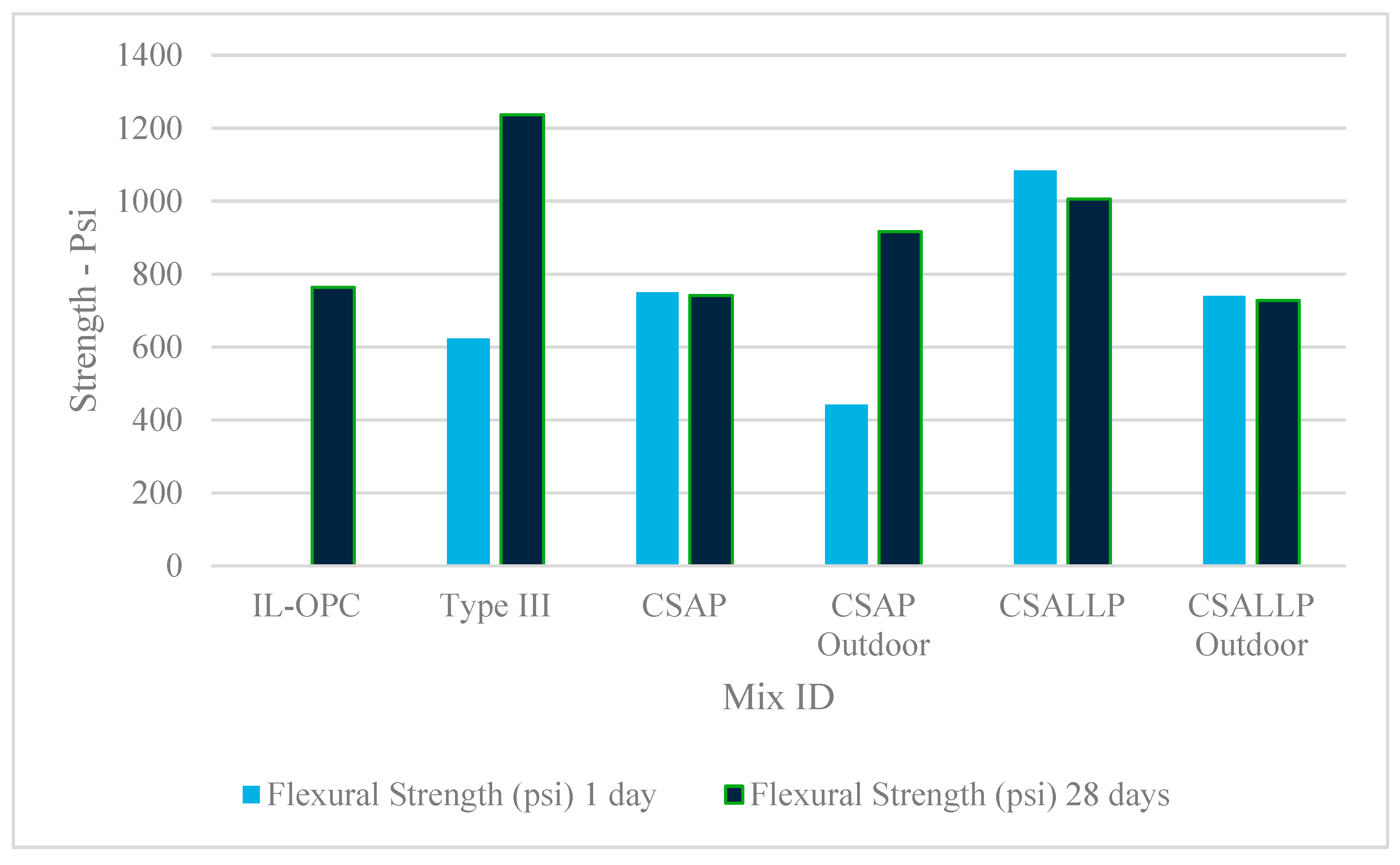

3.2.2. Flexural Strength

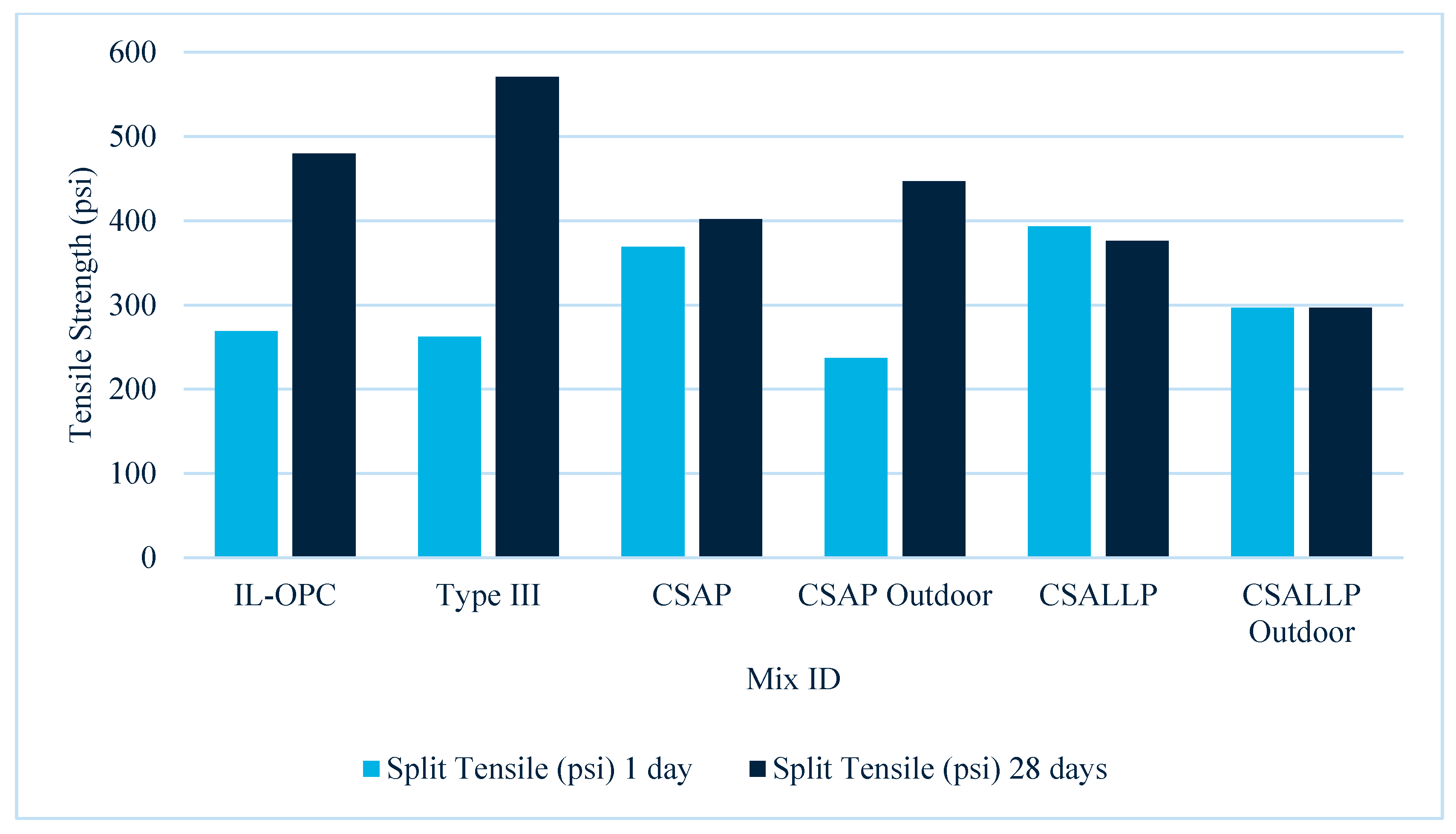

3.2.3. Splitting Tensile Strength

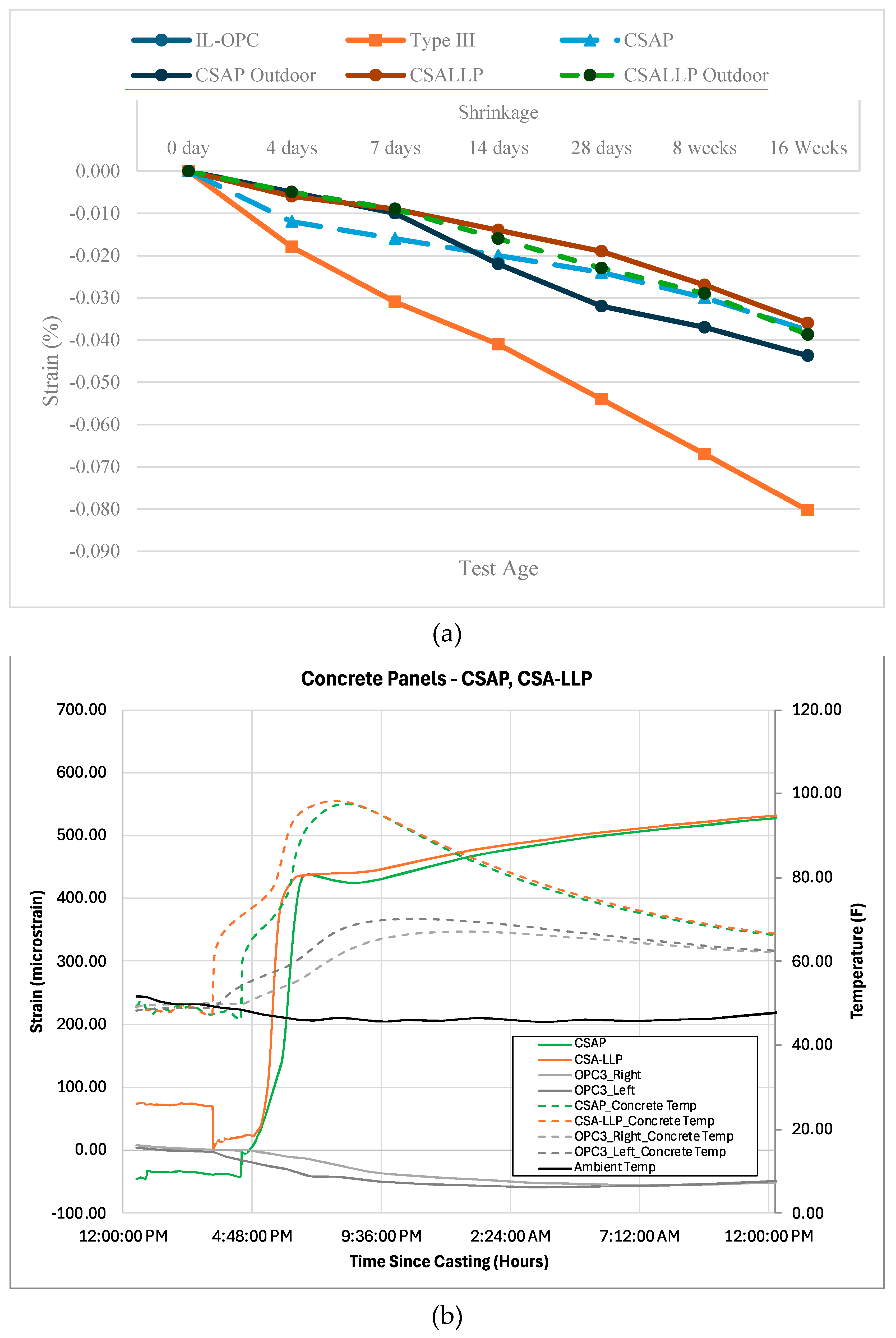

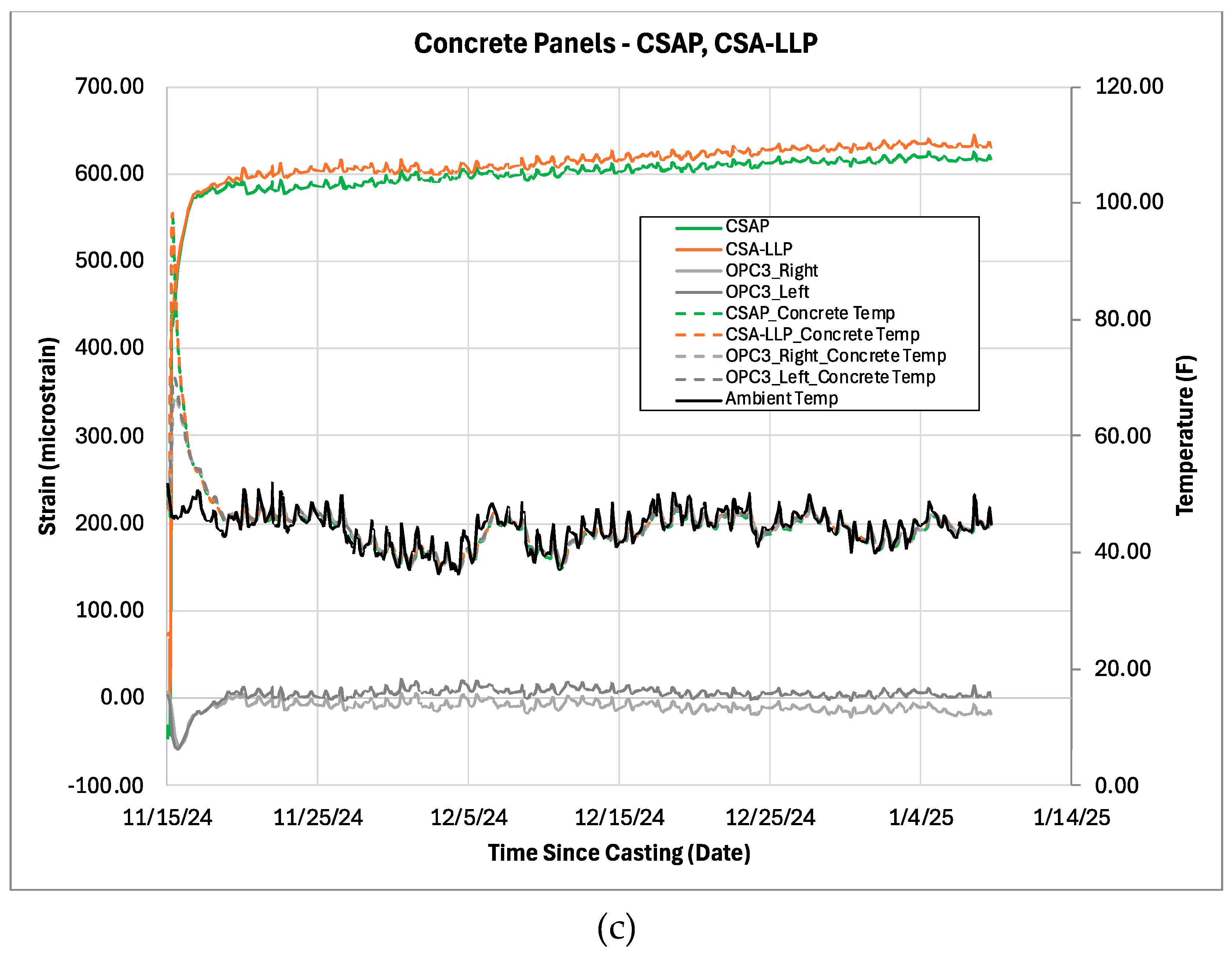

3.3. Shrinkage and Temperature-induced Strain Behavior

3.3.1. Laboratory vs Outdoor Shrinkage

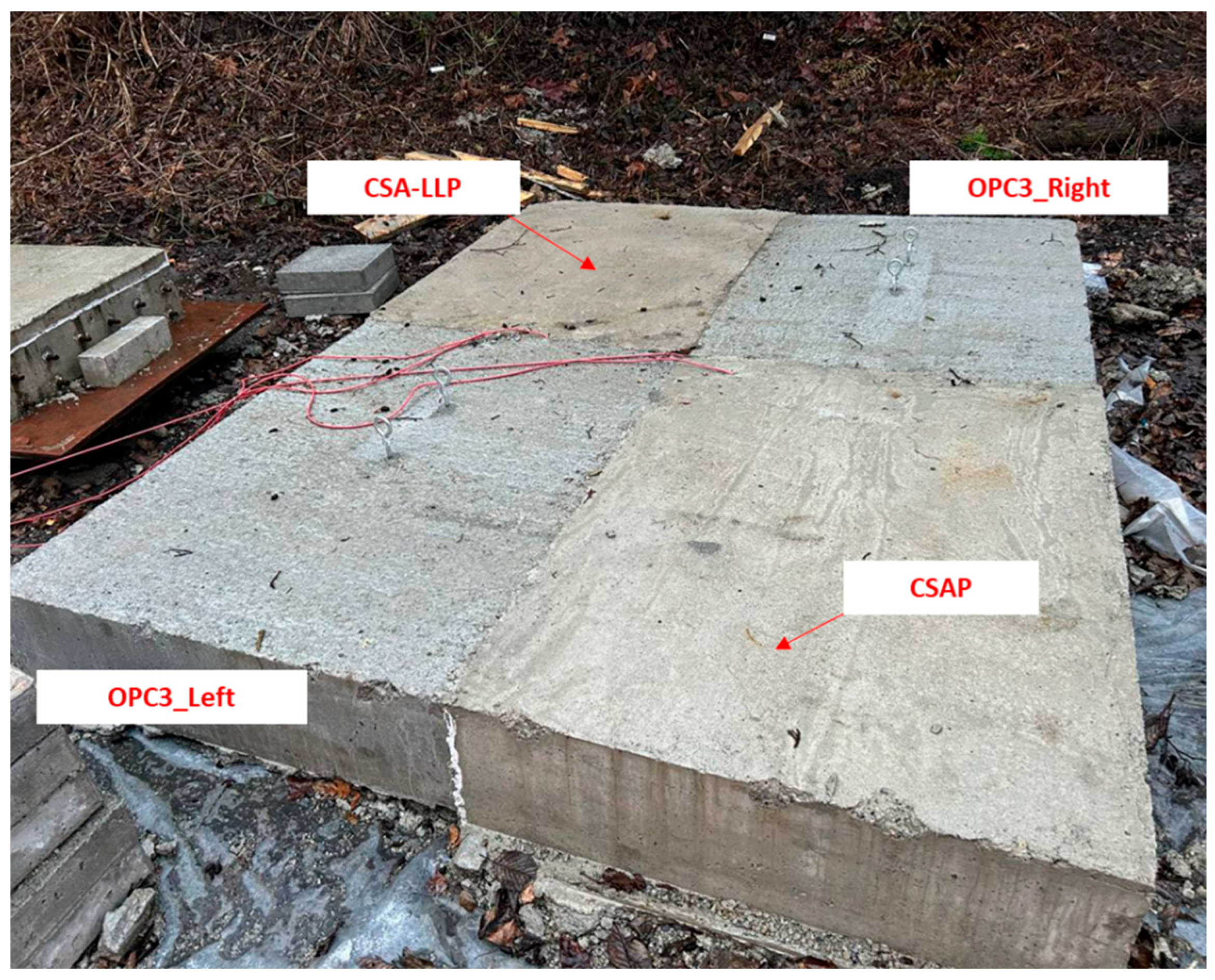

3.3.2. Temperature-Induced Strain

4. Conclusions and Practical Implications

4.1. Conclusions

4.2. Practical Implications and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scrivener, K.L.; John, V.M.; Gartner, E.M. Eco-efficient cements: Potential economically viable solutions for a low-CO2 cement-based materials industry. Cement and Concrete Research 2018, 114, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juenger, M.C.G.; Snellings, R.; Bernal, S.A. Supplementary cementitious materials: New sources, characterization, and performance insights. Cement and Concrete Research 2019, 122, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishnoi, S. Carbon Emissions and Their Mitigation in the Cement Sector. In Carbon Utilization: Applications for the Energy Industry; Goel, M., Sudhakar, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Glasser, F.P.; Zhang, L. High-performance cement matrices based on calcium sulfoaluminate–belite compositions. Cement and Concrete Research 2001, 31, 1881–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. Shrinkage characteristics of calcium sulphoaluminate cement concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2022, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markosian, N.; Tawadrous, R.; Mastali, M.; Thomas, R.J.; Maguire, M. Performance Evaluation of a Prestressed Belitic Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement (BCSA) Concrete Bridge Girder. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X. More than smart pavements: connected infrastructure paves the way for enhanced winter safety and mobility on highways. Journal of Infrastructure Preservation and Resilience 2020, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirtoli, D.; Wyrzykowski, M.; Riva, P.; Tortelli, S.; Marchi, M.; Lura, P. Shrinkage and creep of high-performance concrete based on calcium sulfoaluminate cement. Cement and Concrete Composites 2019, 98, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen Tan, M. Okoronkwo, Aditya Kumar, Hongyan Ma: Durability of calcium sulfoaluminate cement concrete 2020.

- Alexander, M.; Bentur, A.; Mindess, S. Durability of Concrete: Design and Construction; CRC Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-J.; Shin, H.-J.; Park, C.-G. Strength and Durability of Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Latex-Modified Rapid-Set Cement Preplaced Concrete for Emergency Concrete Pavement Repair. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ke, G.; Liu, Y. Early Hydration Heat of Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement with Influences of Supplementary Cementitious Materials and Water to Binder Ratio. Materials 2021, 14, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerele, D.D.; Aguayo, F. Evaluating the Impact of CO2 on Calcium SulphoAluminate (CSA) Concrete. Buildings 2024, 14, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Rahul, A.V.; Mohan, M.K.; De Schutter, G.; Van Tittelboom, K. Recent progress and technical challenges in using calcium sulfoaluminate (CSA) cement. Cement and Concrete Composites 2023, 137, 104908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dr. B.C. Roy Engineering College, Durgapur, Bhattacharya, S.; Ranjan Das, S. SBR-Latex modified concrete: A new avenue for concrete materials, a review. BEST 2023, 4. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim Haruna, S.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, W.; Shao, J. Evaluation of impact resistance properties of polyurethane-based polymer concrete for the repair of runway subjected to repeated drop-weight impact test. Construction and Building Materials 2021, 309, 125152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIQUID_LOW-P_Datasheet_DS_245_EN.pdf. Available online: https://www.ctscement.com/assets/doc/datasheets/LIQUID_LOW-P_Datasheet_DS_245_EN.pdf.

- ACI Committee 548: Report on Polymer-Modified Concrete. America Concrete Institute, American Concrete Institute 38800 Country Club Drive Farmington Hills, MI 48331 U.S.A. (2009).

- Palamarchuk, A.; Yudaev, P.; Chistyakov, E. Polymer Concretes Based on Various Resins: Modern Research and Modeling of Mechanical Properties. Journal of Composites Science 2024, 8, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CTS Cement Manufacturing: Product Liquid Low-PTM | CTS Cement. Available online: https://www.ctscement.com/product/liquid-low-p.

- Wang, K.; Melugiri, B.; Anand, A.; Sargam, Y.; Phares, B. Performance Evaluation of Very Early Strength Latex-Modified Concrete (LMC-VE) Overlay, TR-771, 2024. Iowa State University Institute for Transportation, Institute for Transportation Iowa State University 2711 South Loop Drive, Suite 4700 Ames, IA 50010-8664, 2024.

- CTS Cement Manufacturing: Low-PTM Cement Datasheet | CTS Cement. Available online: https://www.ctscement.com/datasheet/LOW-P_CEMENT_Datasheet_DS_016_EN?c=PAVEMENT%20&t=Professionals.

- WSDOT. Pavement Patching and Repair. In WSDOT Maintenance Manual; Washington State Department of Transportation, 2020; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- WSDOT. Construction Manual 2024. Available online: https://www.wsdot.wa.gov/publications/manuals/fulltext/M41-01/Construction.pdf.

- WSDOT, H.C. Cement Concrete Pavement. 2024. Available online: https://wsdot.wa.gov/publications/manuals/fulltext/M41-10/Division5.

- WSDOT Manual: 2025 Standard Specifications for Road, Bridge, and Municipal Construction. 2025. Available online: https://www.wsdot.wa.gov/publications/manuals/fulltext/M41-10/SS.pdf.

- WSDOT Manual: Division 5 Surface Treatments and Pavements. 2025. Available online: https://wsdot.wa.gov/publications/manuals/fulltext/M41-10/Division5.pdf.

- Li, G.; Zhang, J.; Song, Z.; Shi, C.; Zhang, A. Improvement of workability and early strength of calcium sulphoaluminate cement at various temperature by chemical admixtures. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 160, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, E. The Influence of Citric Acid on Setting Time and Temperature Behavior of Calcium Sulfoaluminate-Belite Cement. 2019. Available online: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/cveguht/50.

- Zhu, H.; Yu, K.; Li, V. Citric Acid Influence on Sprayable Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement-Engineered Cementitious Composites’ Fresh/ Hardened Properties. MJ 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, W.; Ma, S.; Shen, X. Influence of borax and citric acid on the hydration of calcium sulfoaluminate cement. Chem. Pap 2017, 71, 1909–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.M.; Unluer, C.; Shi, J.Y. Rheo-viscoelastic behavior and viscosity prediction of calcium sulphoaluminate modified Portland cement pastes. Powder Technology 2021, 391, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simandl, L.; Biparva, A.; Gupta, R. Cement-based Repair Materials: A Review of Methods for Assessing Durability. Innovations in Corrosion and Materials Science (Discontinued) 2016, 6, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WSDOT Materials Manual: TEMPERATURE OF FRESHLY MIXED PORTLAND CEMENT CONCRETE FOP FOR AASHTO T 309. 2024. Available online: https://www.wsdot.wa.gov/publications/manuals/fulltext/M46-01/t309.pdf.

- Ramseyer, C.; Bescher, E. Performance of Concrete Rehabilitation Using Rapid Setting Calcium SulfoAluminate Cement at the Seattle-Tacoma Airport. Presented at the Transportation Research Board 93rd Annual MeetingTransportation Research Board, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Deo, O.; Win, D.; Bhuskute, N.; Chung, D.; deOcampo, N.; Bescher, E. Fast Setting, Low Carbon Infrastructure Rehabilitation Using Belitic C alcium Sulfoaluminate (BCSA) Concrete. MATEC Web Conf 2022, 361, 00002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Liu, B. Preparation and Characterization of Polymer-Modified Sulphoaluminate-Cement-Based Materials. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroughsabet, V.; Biolzi, L.; Monteiro, P.J.M.; Gastaldi, M.M. Investigation of the mechanical and durability properties of sustainable high performance concrete based on calcium sulfoaluminate cement. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 43, 102656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Gao, X.; Gao, X. Use of carbonation curing to improve mechanical strength and durability of pervious concrete. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2020, 8, 3872–3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Najimi, M.; Shafei, B. Chloride penetration in shrinkage-compensating cement concretes. Cement and Concrete Composites 2020, 113, 103656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Kurtis, K.E. Early-stage assessment of drying shrinkage in Portland limestone cemen t concrete using nonlinear ultrasound. Construction and Building Materials 2022, 342, 128099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, B.A.; Bahraq, A.A.; Haq, M.M. ul; Ojelade, O.A.; Taiwo, R.; Wahab, S.; Adewumi, A.A.; Ibrahim, M. Polymer-enhanced concrete: A comprehensive review of innovations and pathways for resilient and sustainable materials. Next Materials 2024, 4, 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberly, K.; Prasanth, A. Lisa Burris: Alternative Cementitious Materials: An Evolution or Revolution? US Department of Transportation, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rudnicki, T.; Stałowski, P. Fast-Setting Concrete for Repairing Cement Concrete Pavement. Materials 2023, 16, 5909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Han, S.; Luo, Z.; Hao, J.; Zhang, J. Laboratory investigation on early-age shrinkage cracking behavior of partially continuous reinforced concrete pavement. Construction and Building Materials 2023, 377, 131125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WSDOT: Standard plans | WSDOT. Available online: https://wsdot.wa.gov/engineering-standards/all-manuals-and-standards/standard-plans.

- Ghafari, E.; Ghahari, S.A.; Costa, H.; Júlio, E.; Portugal, A.; Durães, L. Effect of supplementary cementitious materials on autogenous shrinkage of ultra-high performance concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2016, 127, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovler, K.; Zhutovsky, S. Overview and Future Trends of Shrinkage Research. Mater Struct 2006, 39, 827–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. Shrinkage characteristics of calcium sulphoaluminate cement concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2022, 337, 127627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Chen, Y.; Lindquist, W.; Ibrahim, A.; Tobias, D.; Krstulovich, J.; and Hindi, R. Large-scale testing of shrinkage mitigating concrete. Journal of Sustainable Cement-Based Materials 2019, 8, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lura, P.; Winnefeld, F.; Klemm, S. Simultaneous measurements of heat of hydration and chemical shrinkage on hardening cement pastes. J Therm Anal Calorim 2010, 101, 925–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortelli, S.; Reggia, A.; Marchi, M.; Plizzari, G.A. Performance of calcium-sulpho aluminate cement for concrete pavement applications: A numerical and experimental investigation. Presented at the 11th International Concrete Sustainability Conference, Washington DC, USA, May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Wei, X.; Cai, X.; Deng, H.; Li, B. Mechanical and Microstructural Characteristics of Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement Exposed to Early-Age Carbonation Curing. Materials 2021, 14, 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.; Afroz, S.; Zhang, Y.; Kim, T.; Li, W.; Castel, A. Autogenous and total shrinkage of limestone calcined clay cement (LC3) concretes. CONSTRUCTION AND BUILDING MATERIALS 2022, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quezada, I.; Thomas, R.J.; Maguire, M. Internal Curing to Mitigate Cracking in Rapid Set Repair Media. Advances in Civil Engineering Materials 2018, 7, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. The Role of Polymer in Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement-Based Materials. In Concrete-Polymer Composites in Circular Economy; Czarnecki, L., Garbacz, A., Wang, R., Frigione, M., Aguiar, J.B., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Wang, R.; Lu, Q. Influence of polymer latex on the setting time, mechanical properties and durability of calcium sulfoaluminate cement mortar. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 169, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.L.; Guinn, R.J. ASSESSMENT OF DOWEL BAR RESEARCH. Center for Transportation Research and Education Iowa State University ( 2002.

- Guan, Y.; Gao, Y.; Sun, R.; Won, M.C.; Ge, Z. Experimental study and field application of calcium sulfoaluminate cement for rapid repair of concrete pavements. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng 2017, 11, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mix Type | Cement (lb/yd3) | Coarse Aggregate (¾ in., lb/yd3) | Fine Aggregate (lb/yd3) | Water (w/cm ratio) | Admixtures per mass of Cement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory | CSAP | 658 | 1783 | 1192 | 0.38 | 1% MasterAir, 0.15% Citric Acid |

| CSA-LLP | 658 | 1787 | 1202 | 0.38 | 1% MasterAir, 0.15% Citric Acid, 0.40% MasterGlenium, 10 fl oz/cwt Liquid Polymer | |

| Type III (Control) | 658 | 1783 | 1192 | 0.38 | 0.10% MasterAir, 0.25% MasterGlenium | |

| Outdoor | CSAP | 658 | 1783 | 1192 | 0.36 | 1% MasterAir, 0.15% Citric Acid |

| CSA-LLP | 658 | 1787 | 1202 | 0.36 | 1% MasterAir, 0.15% Citric Acid, 0.40% MasterGlenium, 10 fl oz/cwt Liquid Polymer | |

| Type IL | 564 | 2180 | 1011 | 0.44 | 0.496 lb. Daravair 1000, 1.286 lb. WRDA 64 |

| Mix Type | Initial Slump (in.) | Air Content (%) | Initial Placement Temperature (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSAP (Lab) | 31-inch spread (slump flow) | 3.4 | 87 |

| CSA-LLP (Lab) | 8.5 | 4.0 | 78 |

| Type III (Control -Lab) | 9.0 | 4.7 | 84 |

| CSAP Outdoor | 8.5 | 4.5 | 62 |

| CSA-LLP Outdoor | 4.8 | 4.0 | 62 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).