Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

04 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

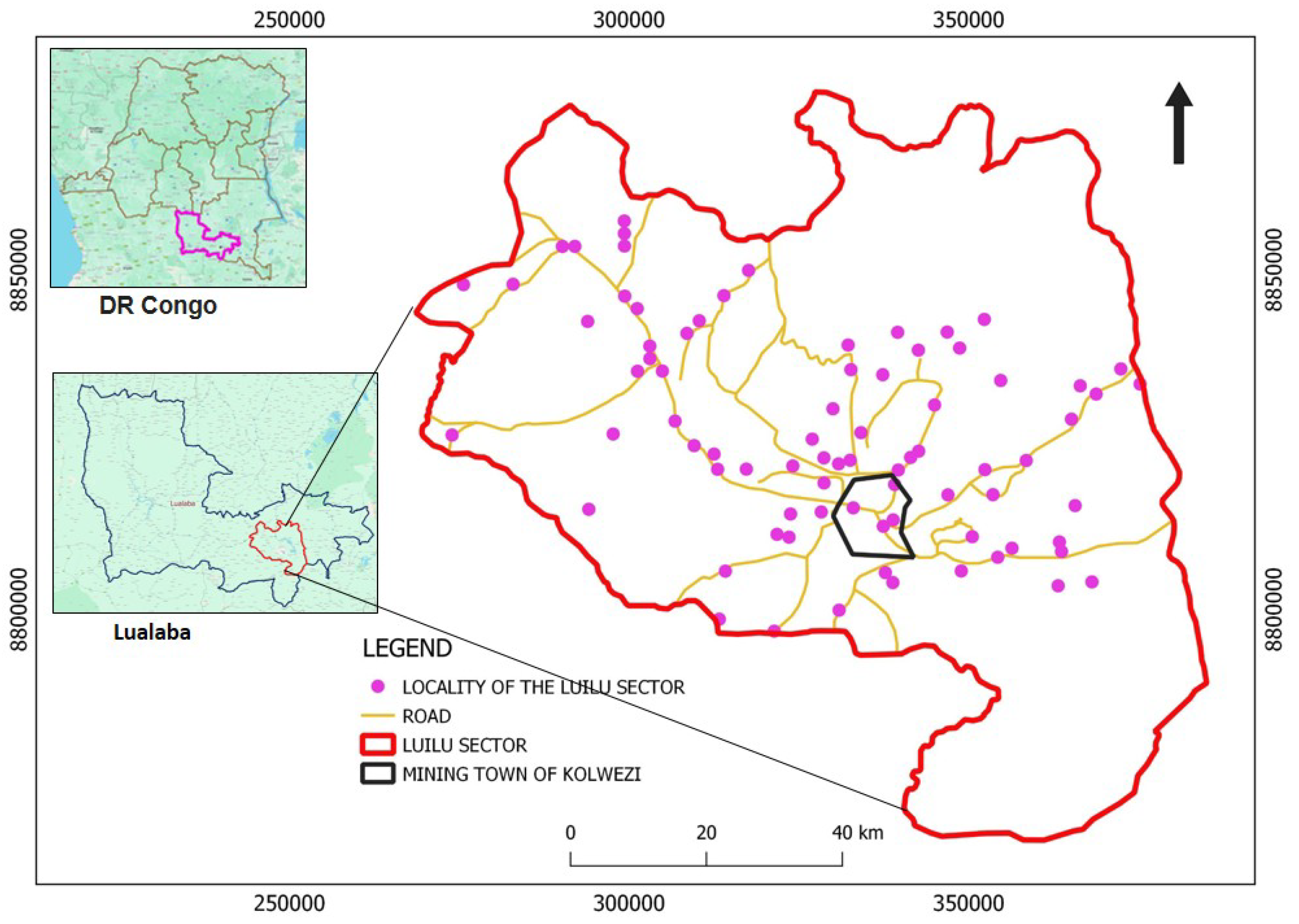

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Acquisition and Processing of Satellite Data

2.2.1. Source of Satellite Data

2.2.2. Preprocessing of Satellite Images

2.2.3. Selection of Training Areas

- Forest: mixed formations with a sparse herbaceous layer under a 15–20 m canopy, including dry dense forest, gallery forests, and Miombo woodland dominated by Brachystegia, Julbernardia, and Isoberlina [43].

- Shrub savanna: shrub and tree formations, often resulting from Miombo degradation or the evolution of grass savannas; their expansion generally indicates anthropogenic influence [28].

- Grassland: steppe and herbaceous savannas, either natural or anthropogenic, whose extent also reflects human pressures [28].

- Agriculture: cultivated plots, either in rotation or fallow [44].

- Bare soil and built-up areas: bare or rocky soils, roads, settlements, and mining sites, particularly around Kolwezi.

- Water: rivers, lakes, and ponds.

2.2.4. Supervised Classification

2.2.5. Landscape Dynamics Analysis

3. Results

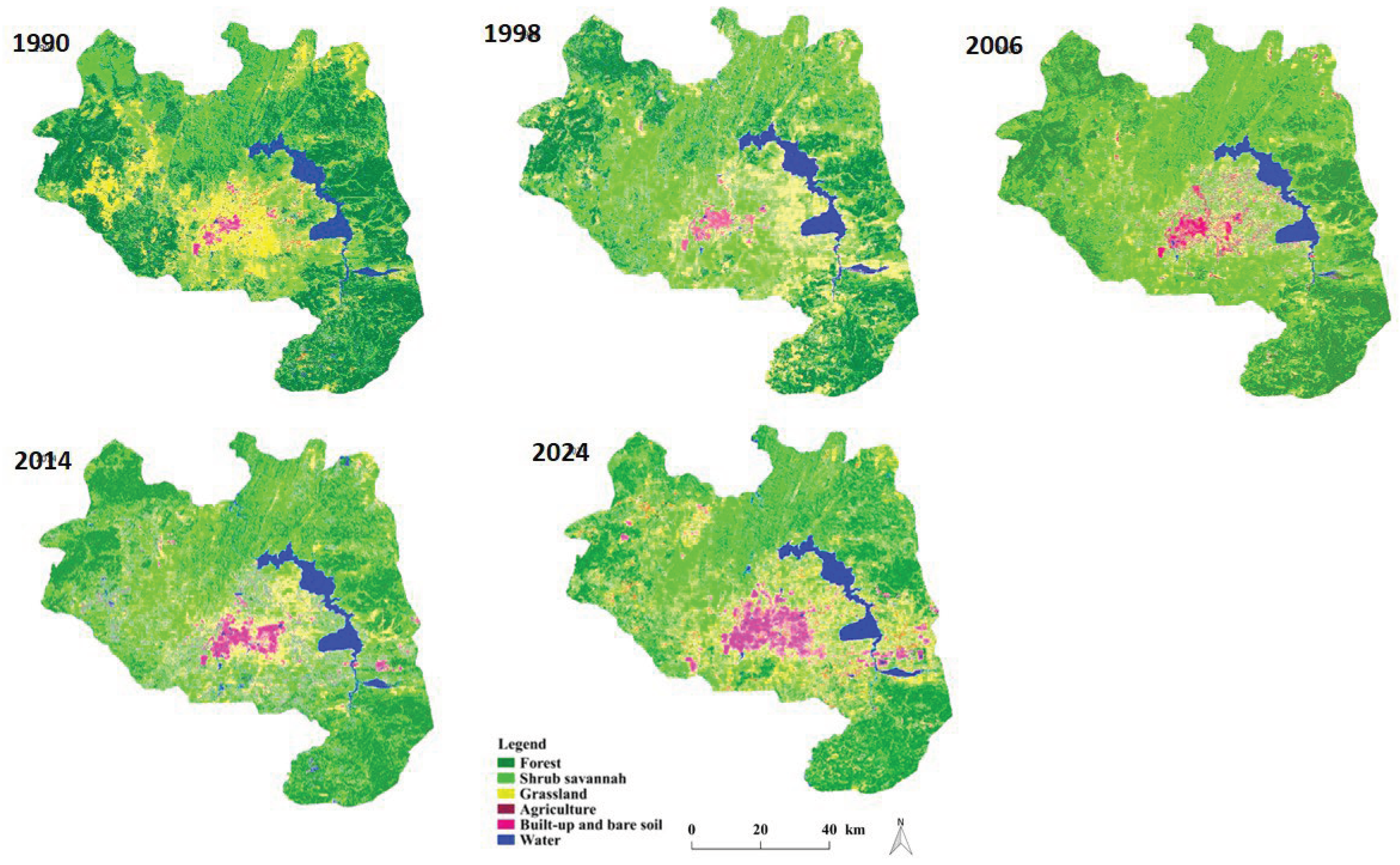

3.1. Land-Use Mapping

3.2.1. Spatial Recomposition and Anthropization Dynamics

3.2.2. Class Stability and Ecological Resiliences

3.2.3. Evolution of Landscape Diversity in the Luilu Sector (1990–2024)

3.3. Structural Dynamics and Spatial Transformation Processes in Luilu (1990–2024)

3.3.1. Spatial Configuration of the Landscape

3.3.2. Spatial Transformation Processes

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Approach

4.2. Spatial Dynamics and Landscape Recomposition in the Luilu Sector (1990–2024)

4.3. Socio-Ecological Implications of the Findings for Conservation and Sustainable Management

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fahrig, L. Effects of Habitat Fragmentation on Biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003, 34, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, K.; Tiho, S.; Ouattara, K.; Konate, S.; Kouakou, L.; Fofana, M. Impact de la fragmentation et de la pression humaine sur la relique forestière de l’Université d’Abobo-Adjamé (Côte d’Ivoire). J. Appl. Biosci. 2013, 61, 4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoji Muteya, H.; N’tambwe Nghonda, D.D.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J.; Useni Sikuzani, Y. Mapping and quantifying deforestation in the Zambezi ecoregion of Central-Southern Africa: extent and spatial structure. Front. Remote Sens. 2025, 6, 1590591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Pulido, J.A.; Guevara-Sanginés, A.; Arias Martelo, C. A meta-analysis of economic valuation of ecosystem services in Mexico. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orimoloye, I.R.; Ololade, O.O. Spatial evaluation of land-use dynamics in gold mining area using remote sensing and GIS technology. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 17, 4465–4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamba, I.; Barima, Y.S.S.; Bogaert, J. Influence de la densité de la population sur la structure spatiale d’un paysage forestier dans le bassin du Congo en R. D. Congo. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2010, 3, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; Bamba, I.; Koffi, K.J.; Sibomana, S.; Djibu, J.-P.K.; Champluvier, D.; Robbrecht, E.; De Cannière, C.; Visser, M.N. Fragmentation of Forest Landscapes in Central Africa: Causes, Consequences and Management. In Patterns and Processes in Forest Landscapes; Lafortezza, R., Sanesi, G., Chen, J., Crow, T.R., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, P.; Vermeulen, C.; Feintrenie, L.; Dessard, H.; Garcia, C. Quelles sont les causes de la déforestation dans le bassin du Congo? Synthèse bibliographique et études de cas. BASE 2016, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchatchou, B.; Sonwa, D.J.; Ifo, S.; Tiani, A.M. Déforestation et dégradation des forêts dans le Bassin du Congo: État des lieux, causes actuelles et perspectives. CIFOR, 2015.

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Bogaert, J. The Evolution of Landscape Ecology in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (2005–2025): Scientific Advances, Methodological Challenges, and Future Directions. Earth 2025, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pro, G.F.W.; Watcher, F.; Atlases, F. Global Forest Watch. Update, 2023.

- Cabala Kaleba, S.; Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Sambieni, K.R.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F. Dynamique des écosystèmes forestiers de l'Arc Cuprifère Katangais en République Démocratique du Congo. I. Causes, transformations spatiales et ampleur. Tropicultura 2017, 35, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Assani, A.A.; Petit, F.; Mabille, G. Analyse des débits de la Warche aux barrages de Butgenbach et de Robertville. Bull. Soc. Géogr. Liège, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Muledi, J.I.; Momo, S.T.; Ploton, P.; Kamukenge, A.L.; Ibey, W.K.; Pamavesi, B.M.; … Barbier, N. Allometric Equations for Aboveground Biomass Estimation in Wet Miombo Forests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo Using Terrestrial LiDAR. Environments 2025, 12, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’tambwe Nghonda, D.-D.; Muteya, H.K.; Kashiki, B.K.W.N.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Malaisse, F.; Sikuzani, Y.U.; Kalenga, W.M.; Bogaert, J. Towards an Inclusive Approach to Forest Management: Highlight of the Perception and Participation of Local Communities in the Management of Miombo Woodlands around Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, D.R. Congo). Forests 2023, 14, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’tambwe Nghonda, D.-D.; Khoji Muteya, H.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Cabala Kaleba, S.; Malaisse, F.; Koy, J.K.; Masengo Kalenga, W.; Bogaert, J.; Useni Sikuzani, Y. Exploring the Role of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Restoring and Managing Miombo Woodlands: A Case Study from the Lubumbashi Region, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Forests 2025, 16, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabala Kaleba, S.; Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Mwana Yamba, A.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F.; Bogaert, J. Activités anthropiques et dynamique des écosystèmes forestiers dans les zones territoriales de l’Arc Cuprifère Katangais (RD Congo). Tropicultura 2022. [CrossRef]

- Muteya, H.K.; Nghonda, D.-D.N.; Malaisse, F.; Waselin, S.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Kaleba, S.C.; Kankumbi, F.M.; Bastin, J.-F.; Bogaert, J.; Sikuzani, Y.U. Quantification and Simulation of Landscape Anthropization around the Mining Agglomerations of Southeastern Katanga (DR Congo) between 1979 and 2090. Land 2022, 11, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Kikuni Tchowa, J.; Kabamb Kanyimb, D.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Hierarchical Analysis of Miombo Woodland Spatial Dynamics in Lualaba Province (Democratic Republic of the Congo), 1990–2024: Integrating Remote Sensing and Landscape Ecology Techniques. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Investigating of spatial urban growth pattern and associated landscape dynamics in Congolese mining cities bordering Zambia from 1990 to 2023. Resources 2024, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukenza, M.M.; Muteya, H.K.; Nghonda, D.-D.N.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Malaisse, F.; Kaleba, S.C.; Bogaert, J.; Sikuzani, Y.U. Uncontrolled Exploitation of Pterocarpus tinctorius Welw. and Associated Landscape Dynamics in the Kasenga Territory: Case of the Rural Area of Kasomeno (DR Congo). Land 2022, 11, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Kipili Mwenya, I.; Khoji Muteya, H.; Malaisse, F.; Cabala Kaleba, S.; Bogaert, J. Anthropogenic pressures and spatio-temporal dynamics of forest ecosystems in the rural and border municipality of Kasenga (DRC). Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 20, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Khoji Muteya, H.; Yona Mleci, J.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. The Restoration of Degraded Landscapes along the Urban–Rural Gradient of Lubumbashi City (Democratic Republic of the Congo) by Acacia auriculiformis Plantations: Their Spatial Dynamics and Impact on Plant Diversity. Ecologies 2024, 5, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.X.; Tao, Y.U.; Huang, X.Z.; Gu, X.F. Agricultural remote sensing big data: Management and applications. J. Integr. Agric. 2018, 17, 1915–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, C.; Adamo, M.; Mairota, P. Remote sensing for conservation monitoring: Assessing protected areas, habitat extent, habitat condition, species diversity, and threats. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 33, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, J.S.; Kumar, M. Monitoring land use/cover change using remote sensing and GIS techniques: A case study of Hawalbagh block, district Almora, Uttarakhand, India. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2015, 18, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohn, R.C. Remote Sensing for Landscape Ecology: New Metric Indicators for Monitoring, Modeling, and Assessment of Ecosystems; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 1–350. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, M.A.; Cardille, J.A. Remote sensing’s recent and future contributions to landscape ecology. Curr. Landsc. Ecol. Rep. 2020, 5, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Z. 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaisse, F. How to Live and Survive in Zambezian Open Forest (Miombo Ecoregion); Les Presses Agronomiques de Gembloux: Gembloux, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hamadi, A.; Borderies, P.; Albinet, C.; Koleck, T.; Villard, L.; Ho Tong Minh, D.; Le Toan, T.; Burban, B. Temporal Coherence of Tropical Forests at P-Band: Dry and Rainy Seasons. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2015, 12, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflumm, L.; Kang, H.; Wilting, A.; Niedballa, J. GEE-PICX: Generating cloud-free Sentinel-2 and Landsat image composites and spectral indices for custom areas and time frames – a Google Earth Engine web application. Ecography 2025, 5, e07385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermida, S.L.; Soares, P.; Mantas, V.; Göttsche, F.-M.; Trigo, I.F. Google Earth Engine Open-Source Code for Land Surface Temperature Estimation from the Landsat Series. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.N.; Kuch, V.; Lehnert, L.W. Land Cover Classification using Google Earth Engine and Random Forest Classifier—The Role of Image Composition. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Song, J.; Zhang, Z. In-Memory Distributed Mosaicking for Large-Scale Remote Sensing Applications with Geo-Gridded Data Staging on Alluxio. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senay, G.B.; Schauer, M.; Friedrichs, M.; Velpuri, N.M.; Singh, R.K. Satellite-based water use dynamics using historical Landsat data (1984–2014) in the southwestern United States. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.; Mattoo, M.; Deshpande, A.M.; Dey, A.; Akiwate, S. Vegetation Change Detection Through NDVI Analysis Using Landsat-8 Data. 2024 4th Int. Conf. Comput., Commun., Control & Inf. Technol. (C3IT) 2024, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Udin, W.S.; Zahuri, Z.N. Land Use and Land Cover Detection by Different Classification Systems using Remotely Sensed Data of Kuala Tiga, Tanah Merah Kelantan, Malaysia. J. Trop. Resour. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 5, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedona, R.; Paris, C.; Tian, L.; Riedel, M.; Cavallaro, G. An Automatic Approach for the Production of a Time Series of Consistent Land-Cover Maps Based on Long-Short Term Memory. IGARSS 2022 - 2022 IEEE Int. Geosci. Remote Sens. Symp. 2022, 203–206. [CrossRef]

- Tomaselli, V.; Veronico, G.; Sciandrello, S.; Blonda, P. How does the selection of landscape classification schemes affect the spatial pattern of natural landscapes?

- Lu, K.; Ma, Z.; Huo, P.; He, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, X. Mixed Pixel Saturability Based Area Estimation Model on Remote Sensing Image. 2023 IEEE 6th Int. Conf. Pattern Recognit. Artif. Intell. (PRAI) 2023, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B.M.; Campbell, B. ; Center for International Forestry Research (Eds.). The Miombo in Transition: Woodlands and Welfare in Africa; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Muteya, H.K.; Nghonda, D.-D.N.; Kalenda, F.M.; Strammer, H.; Kankumbi, F.M.; Malaisse, F.; Bastin, J.-F.; Sikuzani, Y.U.; Bogaert, J. Mapping and Quantification of Miombo Deforestation in the Lubumbashi Charcoal Production Basin (DR Congo): Spatial Extent and Changes between 1990 and 2022. Land 2023, 12, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Lee, C.-D.; Chen, G.; Zhang, J. Research on the Prediction Application of Multiple Classification Datasets Based on Random Forest Model. 2024 IEEE 6th Int. Conf. Power, Intell. Comput. Syst. (ICPICS), 2024; 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakir, G.; Sivrikaya, F.; Keleş, S. Forest cover change and fragmentation using Landsat data in Maçka State Forest Enterprise in Turkey. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2008, 137, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, P.; Foody, G.M.; Stehman, S.V.; Woodcock, C.E. Making better use of accuracy data in land change studies: Estimating accuracy and area and quantifying uncertainty using stratified estimation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 129, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; Barima, Y.S.S.; Ji, J.; Jiang, H.; Bamba, I.; Mongo, L.I.W.; Mama, A.; Nyssen, E.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F.; Koedam, N. A Methodological Framework to Quantify Anthropogenic Effects on Landscape Patterns. In Landscape Ecology in Asian Cultures; Hong, S.-K., Kim, J.-E., Wu, J., Nakagoshi, N., Eds.; Springer Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2011; pp. 141–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; Ceulemans, R.; Salvador-Van Eysenrode, D. Decision Tree Algorithm for Detection of Spatial Processes in Landscape Transformation. Environ. Manage. 2004, 33, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musavandalo, C.M.; Sambieni, K.R.; Mweru, J.P.M.; Bastin, J.F.; Ndukura, C.S.; Nguba, T.B.; … Bogaert, J. Land cover dynamics in the northwestern Virunga landscape: An analysis of the past two decades in a dynamic economic and security context. Land 2024, 13, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; Ceulemans, R.; Salvador-Van Eysenrode, D. Decision Tree Algorithm for Detection of Spatial Processes in Landscape Transformation. Environ. Manage. 2004, 33, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haulleville, T.; Rakotondrasoa, O.L.; Rakoto Ratsimba, H.; Bastin, J.-F.; Brostaux, Y.; Verheggen, F.J.; Rajoelison, G.L.; Malaisse, F.; Poncelet, M.; Haubruge, É.; Beeckman, H.; Bogaert, J. Fourteen years of anthropization dynamics in the Uapaca bojeri Baill. Forest of Madagascar. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 14, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarigal, K.; Cushman, S.A. Comparative evaluation of experimental approaches to the study of habitat fragmentation effects. Ecol. Appl. 2002, 12, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mama, A.; Sinsin, B.; Cannière, C.D.; Bogaert, J. Anthropisation et dynamique des paysages en zone soudanienne au nord du Bénin, 2013.

- Thenkabail, P.S.; Teluguntla, P.G.; Xiong, J.; Oliphant, A.; Congalton, R.G.; Ozdogan, M.; … Foley, D. Global cropland-extent product at 30-m resolution (GCEP30) derived from Landsat satellite time-series data for the year 2015 using multiple machine-learning algorithms on Google Earth Engine cloud (No. 1868). US Geological Survey, 2021.

- Hussain, K.; Mehmood, K.; Anees, S.A.; Ding, Z.; Muhammad, S.; Badshah, T.; … Khan, W.R. Assessing forest fragmentation due to land use changes from 1992 to 2023: A spatio-temporal analysis using remote sensing data. Heliyon 2024, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, C.; Walton, G.; Santi, P.; Luza, C. Random Cross-Validation Produces Biased Assessment of Machine Learning Performance in Regional Landslide Susceptibility Prediction. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, A.; Boukir, S.; Haywood, A.; Jones, S. Exploring issues of training data imbalance and mislabelling on random forest performance for large area land cover classification using the ensemble margin. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2015, 105, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicol, I.M.; Ryan, C.M.; Williams, M. How resilient are African woodlands to disturbance from shifting cultivation? Ecol. Appl. 2018, 28, 1645–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaba, F.K.; Quinn, C.H.; Dougill, A.J.; Vinya, R. Floristic composition, species diversity and carbon storage in charcoal and agriculture fallows and miombo woodland in Zambia. For. Ecol. Manage. 2013, 304, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.M.; Pritchard, R.; McNicol, I.; Owen, M.; Fisher, J. Ecosystem services from southern African woodlands and their future under global change. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2016, 371, 20150312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurance, W.F.; et al. The fate of Amazonian forest fragments: A 32-year investigation. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.E.; Rocliffe, S.; Haddaway, N.R.; Dunn, A.M. The role of mining in land use change in Africa: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 1224–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidumayo, E.N. Forest degradation and recovery in a miombo woodland landscape in Zambia: 22 years of observations on permanent sample plots. For. Ecol. Manage. 2013, 291, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Boisson, S.; Cabala Kaleba, S.; Nkuku Khonde, C.; Malaisse, F.; Halleux, J.M.; … Munyemba Kankumbi, F. Dynamique de l'occupation du sol autour des sites miniers le long du gradient urbain-rural de la ville de Lubumbashi, RD Congo. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2020, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mununga Katebe, F.; Raulier, P.; Colinet, G.; Ngoy Shutcha, M.; Mpundu Mubemba, M.; Jijakli, M.H. Assessment of heavy metal pollution of agricultural soil, irrigation water, and vegetables in and nearby the Cupriferous City of Lubumbashi,(Democratic Republic of the Congo). Agronomy 2023, 13, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wasseige, C.; Flynn, J.; Louppe, D.; Hiol Hiol, F.; Mayaux, P. Les forêts du bassin du Congo-Etat des forêts 2013; Weyrich, 2014.

- Bourgeois, M.; Cossart, É.; Fressard, M. Mesurer et spatialiser la connectivité pour modéliser les changements des systèmes environnementaux. Approches comparées en écologie du paysage et en géomorphologie. Géomorphologie 2017, 23, 289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Decocq, G.; Dupouey, J.L.; Bergès, L. Dynamiques forestières à l'ère anthropocène: mise au point sémantique et proposition de définitions écologiques. Rev. For. Fr. 2021, 73, 21–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameja, L.G.; Ribeiro, N.; Sitoe, A.A.; Guillot, B. Regeneration and restoration status of Miombo woodland following land use land cover changes at the buffer zone of Gile National Park, Central Mozambique. Trees For. People 2022, 9, 100290. [Google Scholar]

- Simeon, K.; Alphonse, K.; Trésor, M.; Clément, T.; Thierry, A.S.; Aloïse, B.; Urbain, M.; Joel, L.; Ezéchiel, M.; Sylvestre, C. Land Use and Land Cover Change in the Urban Landscape of Butembo, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Int. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 7, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muimba-Kankolongo, A.; Banza Lubaba Nkulu, C.; Mwitwa, J.; Kampemba, F.M.; Mulele Nabuyanda, M. Impacts of trace metals pollution of water, food crops, and ambient air on population health in Zambia and the DR Congo. J. Environ. Public Health 2022, 2022, 4515115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lines, R.; Bormpoudakis, D.; Xofis, P.; Tzanopoulos, J. Modelling Multi-Species Connectivity at the Kafue-Zambezi Interface: Implications for Transboundary Carnivore Conservation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Bamford, A.J.; Ferrol-Schulte, D.; Hieronimo, P.; McWilliam, N.; Rovero, F. Vanishing wildlife corridors and options for restoration: a case study from Tanzania. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2012, 5, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleper, S. Pister les gnous: Médiation technologique entre humains et faune sauvage au Serengeti depuis les années 1950. In Protéger et détruire: Gouverner la nature sous les Tropiques; CNRS Editions: Paris, France, 2022; pp. 269–298. [Google Scholar]

- Nackoney, J.; Williams, D. Conservation prioritization and planning with limited wildlife data in a Congo Basin forest landscape: assessing human threats and vulnerability to land use change. J. Conserv. Plan. 2012, 8, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mayifilua, J.; Mbula, D.; Muliele, J.C.; Ombeni, I. Maringa-Lopori-Wamba Landscape; Center for International Forestry Research, 2022.

- Vaglio, S.; Mauno, U.; Chiarelli, B. Application of Kyoto Protocol in the Conservation of Bonobos (Pan paniscus). Glob. Bioeth. 2007, 20, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Forest UA | Forest PA | Shrub Savanna UA | Shrub Savanna PA | Grassland UA | Grassland PA | Agriculture UA | Agriculture PA | Built-up & Bare Soil UA | Built-up & Bare Soil PA | Water UA | Water PA | Overall Accuracy (%) | Kappa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 91 | 100 | 94 | 94 | 78 | 70 | 71 | 71 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 93 | 91 |

| 1993 | 95 | 96 | 89 | 78 | 48 | 60 | 59 | 59 | 99 | 97 | 100 | 100 | 87 | 83 |

| 1998 | 67 | 95 | 78 | 66 | 73 | 80 | 89 | 47 | 96 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 86 | 82 |

| 2001 | 84 | 100 | 82 | 72 | 47 | 45 | 52 | 76 | 98 | 88 | 100 | 100 | 83 | 79 |

| 2006 | 84 | 100 | 79 | 69 | 57 | 60 | 56 | 59 | 86 | 94 | 100 | 97 | 84 | 80 |

| 2010 | 100 | 100 | 76 | 100 | 92 | 60 | 64 | 82 | 98 | 84 | 100 | 97 | 89 | 87 |

| 2014 | 75 | 100 | 74 | 72 | 53 | 45 | 71 | 59 | 94 | 93 | 97 | 100 | 83 | 78 |

| 2017 | 78 | 100 | 77 | 72 | 71 | 50 | 63 | 88 | 97 | 88 | 97 | 100 | 85 | 81 |

| 2021 | 81 | 100 | 79 | 81 | 56 | 50 | 56 | 53 | 100 | 97 | 100 | 97 | 86 | 82 |

| 2024 | 78 | 100 | 81 | 69 | 65 | 55 | 75 | 88 | 98 | 94 | 94 | 100 | 87 | 82 |

| Period | From \ To | Forest | Shrub Savanna | Grassland | Agriculture | Bare Soil & Built-up | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–1993 | Forest | 29.74 | 9.01 | 2.32 | 9.88 | 0.01 | 50.97 |

| Shrub Savanna | 2.49 | 12.58 | 4.27 | 5.52 | 0 | 24.86 | |

| Grassland | 0.91 | 3.07 | 4 | 7.27 | 0.11 | 15.34 | |

| Agriculture | 0.16 | 0.64 | 1.85 | 1.57 | 0.05 | 4.28 | |

| Bare Soil & Built-up | 0 | 0 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.65 | |

| 1993–1998 | Forest | 23.67 | 4.85 | 4.09 | 0.76 | 0.01 | 33.39 |

| Shrub Savanna | 8.84 | 11.07 | 4.17 | 1.23 | 0.11 | 25.42 | |

| Grassland | 1.24 | 5.83 | 3.52 | 1.27 | 0.69 | 12.55 | |

| Agriculture | 3.97 | 12.39 | 5.24 | 2.55 | 0.29 | 24.44 | |

| Bare Soil & Built-up | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.68 | 0.72 | |

| 1998–2001 | Forest | 25.24 | 9.55 | 1.64 | 1.27 | 0 | 37.7 |

| Shrub Savanna | 8.01 | 12.54 | 6.88 | 6.65 | 0.07 | 34.15 | |

| Grassland | 2.16 | 6.24 | 4.33 | 4.29 | 0.12 | 17.15 | |

| Agriculture | 0.83 | 1.36 | 1.51 | 2.09 | 0.03 | 5.81 | |

| Bare Soil & Built-up | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.4 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 1.79 | |

| 2001–2006 | Forest | 26.73 | 8.04 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 36.26 |

| Shrub Savanna | 10.16 | 16 | 1.84 | 1.81 | 0.11 | 29.92 | |

| Grassland | 1.16 | 6.65 | 3.29 | 3.32 | 0.36 | 14.78 | |

| Agriculture | 0.6 | 6.52 | 2.4 | 4.85 | 0.65 | 15.02 | |

| Bare Soil & Built-up | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.65 | 0.87 | |

| 2006–2010 | Forest | 27.81 | 9.77 | 0.91 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 38.87 |

| Shrub Savanna | 4.68 | 25.11 | 5.65 | 1.75 | 0.07 | 37.25 | |

| Grassland | 0.13 | 4.07 | 1.95 | 1.93 | 0.13 | 8.21 | |

| Agriculture | 0.37 | 6.01 | 1.65 | 2.48 | 0.36 | 10.88 | |

| Bare Soil & Built-up | 0.03 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 1.01 | 1.92 | |

| 2010–2014 | Forest | 26.94 | 4.05 | 1.45 | 0.32 | 0.05 | 32.82 |

| Shrub Savanna | 11.36 | 19 | 6.2 | 7.92 | 0.45 | 44.93 | |

| Grassland | 1.05 | 4.85 | 2.04 | 2.09 | 0.2 | 10.24 | |

| Agriculture | 0.12 | 1.47 | 2.39 | 2.24 | 0.57 | 6.79 | |

| Bare Soil & Built-up | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 1.16 | 1.48 | |

| 2014–2017 | Forest | 25.29 | 11.71 | 1.13 | 1.24 | 0.03 | 39.4 |

| Shrub Savanna | 1.85 | 18.89 | 4.83 | 3.72 | 0.07 | 29.36 | |

| Grassland | 0.93 | 3.48 | 4.13 | 3.31 | 0.33 | 12.19 | |

| Agriculture | 0.05 | 3.72 | 2.67 | 6.07 | 0.16 | 12.67 | |

| Bare Soil & Built-up | 0 | 0.04 | 0.36 | 0.51 | 1.55 | 2.45 | |

| 2017–2021 | Forest | 18.32 | 9.27 | 0.49 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 28.27 |

| Shrub Savanna | 7.7 | 22.23 | 4.75 | 3.15 | 0.2 | 38.02 | |

| Grassland | 0.6 | 4.27 | 4.35 | 3.41 | 0.61 | 13.24 | |

| Agriculture | 1.16 | 4.32 | 3.39 | 5.15 | 0.92 | 14.94 | |

| Bare Soil & Built-up | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.2 | 0.13 | 1.75 | 2.15 | |

| 2021–2024 | Forest | 23.02 | 2.21 | 1.13 | 1.44 | 0.15 | 27.95 |

| Shrub Savanna | 14.56 | 15.34 | 4.85 | 4.88 | 0.39 | 40.02 | |

| Grassland | 0.84 | 5.27 | 2.88 | 3.28 | 0.91 | 13.18 | |

| Agriculture | 0.77 | 4.39 | 2.56 | 3.36 | 0.88 | 11.96 | |

| Bare Soil & Built-up | 0 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.64 | 2.73 | 3.49 |

| Period | Forest PSI | Forest ASI | Shrub Savanna PSI | Shrub Savanna ASI | Grassland PSI | Grassland ASI | Agriculture PSI | Agriculture ASI | Bare & Built PSI | Bare & Built ASI | Landscape PSI | Landscape ASI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–1993 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 1.04 | 0.35 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 8.41 | 2.8 | 1.7 | 0.57 | 1.02 | 0.34 |

| 1993–1998 | 1.45 | 0.29 | 1.61 | 0.32 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 27.5 | 5.5 | 0.75 | 0.15 |

| 1998–2001 | 0.88 | 0.29 | 0.8 | 0.27 | 0.81 | 0.27 | 3.46 | 1.15 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.87 | 0.29 |

| 2001–2006 | 1.26 | 0.25 | 1.53 | 0.31 | 0.43 | 0.09 | 0.59 | 0.12 | 5.48 | 1.1 | 1.14 | 0.23 |

| 2006–2010 | 0.47 | 0.12 | 1.65 | 0.41 | 1.34 | 0.34 | 0.52 | 0.13 | 0.75 | 0.19 | 1.51 | 0.38 |

| 2010–2014 | 2.14 | 0.54 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 1.24 | 0.31 | 2.3 | 0.58 | 3.97 | 0.99 | 1.15 | 0.29 |

| 2014–2017 | 0.2 | 0.07 | 1.81 | 0.6 | 1.12 | 0.37 | 1.33 | 0.44 | 0.65 | 0.22 | 1.39 | 0.46 |

| 2017–2021 | 0.95 | 0.24 | 1.13 | 0.28 | 0.99 | 0.25 | 0.7 | 0.18 | 4.43 | 1.11 | 1.16 | 0.29 |

| 2021–2024 | 3.28 | 1.09 | 0.48 | 0.16 | 0.84 | 0.28 | 1.19 | 0.4 | 3.07 | 1.02 | 0.96 | 0.32 |

| Mean | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.65 | 1.19 | 0.31 | ||||||

| Year | Simpson Diversity Index (SIDI) | Simpson Evenness Index (SIEI) |

|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 0.65 | 0.58 |

| 1993 | 0.75 | 0.8 |

| 1998 | 0.71 | 0.69 |

| 2001 | 0.74 | 0.76 |

| 2006 | 0.69 | 0.65 |

| 2010 | 0.67 | 0.61 |

| 2014 | 0.73 | 0.73 |

| 2017 | 0.74 | 0.76 |

| 2021 | 0.73 | 0.74 |

| 2024 | 0.74 | 0.76 |

| Year | Index | Forest | Shrub Savanna | Grassland | Agriculture | Bare & Built | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | n | 111702 | 257212 | 235334 | 94265 | 1850 | 11489 |

| a | 2966.32 | 1867.66 | 1151.47 | 320.87 | 49.18 | 285.28 | |

| ā | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.02 | |

| D | 29.62 | 2.66 | 9.57 | 0.72 | 30.75 | 81.26 | |

| Df(p) | 1.42(0.00) | 1.40(0.00) | 1.42(0.00) | 1.42(0.00) | 1.40(0.00) | 1.47(0.00) | |

| 1993 | n | 129801 | 334719 | 250210 | 216034 | 2590 | 4793 |

| a | 1946.77 | 1909.21 | 942.58 | 1832.91 | 55.18 | 238.54 | |

| ā | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 | |

| D | 29.51 | 7.63 | 5.03 | 13.1 | 30.92 | 91.32 | |

| Df(p) | 1.42(0.00) | 1.42(0.00) | 1.45(0.00) | 1.42(0.00) | 1.50(0.00) | 1.52(0.00) | |

| 1998 | n | 156838 | 179298 | 198450 | 239031 | 10007 | 8617 |

| a | 2828.96 | 2560.83 | 1292.52 | 435.38 | 134.63 | 247.88 | |

| ā | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| D | 19.97 | 13.78 | 2.85 | 0.16 | 43.4 | 82.6 | |

| Df(p) | 1.41(0.00) | 1.41(0.00) | 1.45(0.00) | 1.48(0.00) | 1.50(0.00) | 1.51(0.00) | |

| 2001 | n | 131569 | 251658 | 246762 | 125929 | 10534 | 1034 |

| a | 2719.76 | 2243.39 | 1108.43 | 1126.07 | 65.32 | 236.83 | |

| ā | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.23 | |

| D | 23.6 | 5.27 | 2.75 | 12.83 | 18.92 | 95.24 | |

| Df(p) | 1.41(0.00) | 1.40(0.00) | 1.43(0.00) | 1.42(0.00) | 1.50(0.00) | 1.55(0.00) | |

| 2006 | n | 97820 | 174142 | 169684 | 156703 | 18776 | 705 |

| a | 2920.42 | 2793.83 | 616.76 | 816.97 | 147.39 | 204.49 | |

| ā | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.29 | |

| D | 24.07 | 17.86 | 0.48 | 5.87 | 17.95 | 94.41 | |

| Df(p) | 1.43(0.00) | 1.41(0.00) | 1.44(0.00) | 1.43(0.00) | 1.49(0.00) | 1.47(0.00) | |

| 2010 | n | 77213 | 169674 | 140084 | 78906 | 12475 | 972 |

| a | 2479.07 | 3389.46 | 775.41 | 514.72 | 139.37 | 202.47 | |

| ā | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.21 | |

| D | 15.44 | 23.62 | 0.72 | 6.22 | 22.25 | 92.16 | |

| Df(p) | 1.42(0.00) | 1.41(0.00) | 1.44(0.00) | 1.42(0.00) | 1.43(0.00) | 1.45(0.00) | |

| 2014 | n | 117902 | 186960 | 232705 | 110251 | 13082 | 9323 |

| a | 2964.21 | 2204.81 | 915.97 | 952.15 | 184.07 | 279.3 | |

| ā | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| D | 22.38 | 4.57 | 2.33 | 6.18 | 51.79 | 75.64 | |

| Df(p) | 1.43(0.00) | 1.40(0.00) | 1.45(0.00) | 1.44(0.00) | 1.48(0.00) | 1.51(0.00) | |

| 2017 | n | 72279 | 152582 | 161123 | 83121 | 9753 | 7187 |

| a | 2121.22 | 2853.33 | 994.22 | 1123.81 | 163.79 | 244.14 | |

| ā | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | |

| D | 23.53 | 17.27 | 1.81 | 13.27 | 32.49 | 83.27 | |

| Df(p) | 1.43(0.00) | 1.43(0.00) | 1.43(0.00) | 1.43(0.00) | 1.48(0.00) | 1.47(0.00) | |

| 2021 | n | 142860 | 209388 | 209696 | 183891 | 12790 | 1771 |

| a | 2116.62 | 3013.03 | 993.22 | 900.54 | 263.63 | 213.45 | |

| ā | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.12 | |

| D | 22.45 | 10.51 | 2.01 | 5.93 | 35.86 | 89.11 | |

| Df(p) | 1.43(0.00) | 1.40(0.00) | 1.44(0.00) | 1.42(0.00) | 1.46(0.00) | 1.51(0.00) | |

| 2024 | n | 121087 | 256435 | 287181 | 126465 | 41166 | 10818 |

| a | 2239.82 | 2043.84 | 863.63 | 1023.7 | 382.29 | 246.92 | |

| ā | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

| D | 24.34 | 6.18 | 0.52 | 2.61 | 46.87 | 76.48 | |

| Df(p) | 1.43(0.00) | 1.40(0.00) | 1.44(0.00) | 1.43(0.00) | 1.46(0.00) | 1.52(0.00) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).