1. Introduction

The growth in the number of end-of-life tyres (ELT) represents a significant environmental challenge. It is estimated that one billion tyres are discarded every year worldwide, constituting a considerable volume of waste, that is challenging to degrade due to its composition [

1]. Inadequate management of this waste has been demonstrated to have a significant impact on soil, water, emissions of volatile compounds, and the generation of microplastics [

2]. In contrast, the recycling of ELTs has been demonstrated to have a considerable effect on the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Products manufactured from these tyres exhibit a distinctly lower carbon footprint in comparison to alternative virgin materials [

3].

Tyres are mainly composed of vulcanized rubber, steel, and textile fibers. After removal, mechanical processes of shredding, metal/textile separation and grinding are carried out to obtain recycled rubber in the form of crush, granules or powder [

2,

4].

A promising valorization of ELT is its incorporation into thermoplastic elastomers (TPE) and especially into thermoplastic vulcanized elastomers (TPV) [

5]. Thermoplastic elastomers are a class of materials that combine the elasticity of rubber with the processing properties of thermoplastics. These properties render them as a competitive alternative to recycled rubbers, particularly in the context of thermoplastic vulcanized elastomers (TPV). Vulcanized thermoplastics are a subcategory of thermoplastic elastomers (TPEs), in which the elastomeric phase is crosslinked by vulcanization, resulting in the formation of a rubber phase that is dispersed within a soft thermoplastic matrix [

6]. During the vulcanization process, the rubber particles formed inside the thermoplastic matrix are cross-linked and forming a rubber network. Once this structure is formed, the cross-linked rubber particles increase the elasticity of the formed TPV, prevent the formation of larger rubber aggregates and thereby helping to maintain the desired mechanical properties. These materials have a wide range of applications in various sectors. These sectors include, but are not limited to, the automotive industry, construction, sealant component production, profile and gasket manufacturing [

7,

8,

9,

10].

The integration of this recycled material into new materials can be affected by various factors that present technical challenges, such as interfacial compatibility with polymer matrices, homogeneous dispersion, appearance of impurities, deterioration of thermal and mechanical properties, stability during processing, and the effects of aging. Consequently, within the domain of research, there is an imperative to investigate diverse methodologies for treating ELT, with the objective of enhancing compatibility between disparate matrices and increase the final properties of the resulting materials [

11].

The aim of this project is to introduce powder from end-of-life tyres into vulcanized thermoplastic elastomer (TPV) formulations. In order to determine the effect of varying loading ratios on the final material’s properties, the present study will evaluate a range of loading ratios. The impact of the processing conditions on the mechanical properties of the material, as well as on the reprocessability of the final material, will be examined. Furthermore, the impact of these modifications on the microstructure of the material will be evaluated, with particular attention paid to the distribution of recycled rubber, the dimensions and configuration of the elastomeric phases, and the quality of adhesion at the interface between the rubber and the thermoplastic matrix.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The preparation of thermoplastic vulcanized (TPV) materials was achieved by utilizing high-density polyethylene (HDPE) supplied by Repsol as the thermoplastic matrix, in conjunction with ethylene-propylene-diene monomer (EPDM) supplied by VERSALIS under the trade name of Dutral® TER 4038 EP, which served as the elastomeric phase.

The utilization of end-of-life tyre derivatives (ELT) as complementary materials was a key element of the study. The first was end-of-life tyre powder (ELTp) with a particle size of 800 μm, obtained by shredding and granulating discarded tyres, kindly supplied by Valoriza Servicios Medioambientales. The second material, designated as ELTp-B, is a commercial product consisting of a blend of ELTp and bitumen, together with specific additives for use in asphalt blends. This material was kindly provided by Cirtec.

Furthermore, a variety of solvents were employed, including acetone (Carlo Erba), toluene (J.T. Baker), hexane-1-thiol, and n-hexylamine (TCI Chemicals). All the chemicals were used in the same conditions as received unless it is explicitly indicated in the following sections.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Reclaiming and Devulcanization Processes

ELTp and ELTp-B raw materials were subjected two types of treatment to improve the final properties of the TPV and achieve better interaction between the raw material and the EPDM rubber: first, a thermomechanical devulcanization process was carried out using an industrial extruder (Haake Rheocord 9000) at 180 °C and at a rate of 100 revolutions per minute (rpm) for 5 minutes. The samples produced were labeled “Desv”. Secondly, a mechanical regeneration treatment was applied, for which an external mixer or two-roll mill (Comercio Ercole) with rollers measuring 15 cm in diameter and 30 cm in length, operating at a friction ratio of 1:1.4. The raw material was then subjected to shear stress for 10 minutes, producing a strip of material that was easier to incorporate in the final blend. Materials that undergo this process were designated as “Rod”. A treatment combining both processes was finally administered and the samples were named “Desv Rod”.

2.2.2. Solid-Liquid Extraction and Chemical Probe Treatment

The ELT materials, both treated and untreated, were subjected to an extraction procedure to quantify the extractable compounds present in them and thus evaluate the effectiveness of the applied reclaiming and devulcanization treatments. In order to avoid the loss of powder during the extraction process, the samples were contained in cylinders made of stainless-steel wire mesh (mesh size of 180 μm) with a height and diameter of 2.0 cm. The cylinders were then filled with 1 g of sample.

In order to eliminate soluble organic compounds from the samples, the cylinders were placed in centrifuge tubes and filled with acetone for a period of 24 hours. After that time, the cylinders were removed, and the solvent was replaced by fresh acetone to continue with the extraction process for additional 24 hours. Finally, the cylinders were taken out from the solvent and allowed to dry prior to being weighed.

The process continued with the immersion of the acetone extracted samples (contained in the cylinders) in toluene for a period of 48 hours, renewing after 24 hours with fresh solvent. This procedure extracts the non-crosslinked polymer chains (sol fraction) and also swells the rubber particles in order to facilitates treatment with chemical probe.

Finally, the pre-swollen samples were immersed in a solution of 2 M hexanethiol and 4 M n-hexylamine in toluene for a period of 48 hours at room temperature to cleavage the poly- and di-sulfidic bonds in the networks [

12]. After this treatment, the samples were cleaned using toluene for a period of 48 hours, refreshing the solvent every 24 hours, with the aim of ensuring the complete removal of residues from the solution. Finally, samples were dried and their weight was measured.

2.2.3. TPV Blends

The following ingredients were used to formulate a thermoplastic elastomer containing a matrix of high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and an ethylene propylene diene monomer (EPDM), as shown in

Table 1. The concentration of each ingredient in the recipe was defined in parts per hundred of rubber (phr).

In order to evaluate the effect of ELT powder on the TPV, a fraction of ELTp equivalent to 20% and 40% of the total TPV was incorporated, replacing 30% and 60% of the original EPDM rubber in order to maintain the weight ratio between HDPE and rubber fraction at a constant value of 1.25. The remaining ingredients were adjusted in accordance with the amount of rubber, as illustrated in

Table 2.

In those samples, ELTp and ELTp-B were used to study the effect of adding bitumen to the ELT powder (ELTp-B) in the mechanical properties of the prepared TPVs. Additionally, in order to evaluate the effect of different rubber recycling processes, the same recipes were used by replacing the raw ELTp and ELTp-B with those materials after regeneration and devulcanization treatments.

The effect of the cross-link density in the rubber fraction was also evaluated by increasing the sulphur concentration in the TPV. The sulphur concentration was increased from 2.74 to 5 phr, and the other vulcanization system ingredients were adjusted in accordance with the specifications provided in the

Table 3.

Finally, the tensile mechanical properties of the ELTp-B content were evaluated. In order to achieve this, the amount of ELTp-B with different treatments was reduced to 10% by weight of the total blend. Furthermore, the amount of the previous vulcanization system was maintained at a constant level, with the other ingredients adjusted as shown in

Table 4.

2.2.4. TPV Processing

This section delineates the procedure employed for the preparation and processing of mixtures intended for the manufacture of TPVs. The process is subdivided into three stages. Firstly, the elastomer compound was prepared using a two-roll-mill. Secondly, this elastomer compound was added to the polyolefin to produce the TPV using an internal mixer. Finally, the press molding of the so-obtained TPV provides the samples for the mechanical analysis.

2.2.4.1. Rubber Compound

Initially, the rubber compounds were prepared in a two-roll-mill. Initially, the mastication of EPDM allows the formation of a continuous rubber band. After that, ELTp or ELTp-B was added (except for the case of the virgin TPV that does not contains this ingredient) and mixed until optimal dispersion and homogenization were achieved. The subsequent ingredients were introduced in the following sequence: activators (ZnO and stearic acid), accelerators (TMTD and MBTS), and sulphur.

2.2.4.2. TPV Blend

The rubber compound performed in the previous step was incorporated into the HDPE matrix using an internal Haake-Rheomix mixer at a temperature of 160 °C and a rotor speed of 80 revolutions per minute (rpm). The internal mixer possesses a total capacity of 78 cm³ and is equipped with Bambury type rotors. It is imperative to consider the filling factor, which reached 60%, equivalent to 42-44 g of blend, to ensure effective sharing and mixing effort.

The HDPE firstly incorporated to the internal mixer and molten during two minutes. After that, the rubber compound (previously prepared) was incorporated until a total of 15 minutes of mixing was completed at a temperature of 160 °C.

2.2.4.3. Compression Molding

The TPV samples were press molded using a Collin 200P automatic press. The process was carried out at a temperature of 170 °C using a steel mold with dimensions of 10 mm x 10 mm x 1 mm. The compression molding process were carried according to the following stages:

The mold with the TPV sample was introduced into the press at without pressure during 5 minutes.

Subsequently, the pressure was increased until 50 bar, maintained it constant for a period of 10 minutes.

The pressure was then increased until reach 150 bar and maintained during 10 minutes.

Finally, the sample was cooled up to 70 °C for a period of 10 minutes.

Once the TPV sheets were obtained, the specimens for the mechanical tests were obtained by using a CEAST pneumatic die cutter.

2.2.5. Characterization Tests

This section presents the tests carried out for the characterization of the vulcanized thermoplastic elastomers in this work.

2.2.5.1. Mechanical Properties

A tensile test was carried out in order to evaluate the mechanical properties of the obtained materials. The tests were carried out in compliance with the ISO 37 standard [

13], using the Instron 3366 universal testing machine. Type 2 dumb-bells test piece were used, recording the average thicknesses at three different measurement points and establishing a test length of 20 mm to record the results by video. The test procedure was carried out at a speed of 500 mm/min, using a load cell of 1 kN. Five test pieces were analyzed, and the median value was taken as a result of each property: the stress at 50% strain or modulus 50 (M50), stress at 100% deformation or modulus 100 (M100) as well as the maximum stress and deformation at break.

2.2.5.2. Differencial Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis were performed using a Netzsch DSC 214 equipment to evaluate the HDPE crystallinity in the different TPV blends. Three temperature ramps were implemented with a nitrogen flow of 50 mL/min, at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. The first ramp eliminated the thermal history of the sample, covering a range from a temperature of -90 °C to 150 °C. The second ramp started at 150 °C, descending to -90 °C. Finally, the third ramp ended with an increase in temperature until reach 150 °C.

2.2.5.3. Freezing Point Depression

Additional differential scanning calorimetry analysis was performed to characterize the freezing point depression of the solvent absorbed in the rubber compounds to estimate the formation of vacuoles and empty spaces at the rubber interface (with fillers or with ELP-p). Vulcanized rubber samples with an approximate size of 5 mm³ were swollen in cyclohexane, a solvent selected for its favorable behavior in terms of crystallization according to the DSC [

14]. During the swelling process, the samples were kept protected from light to prevent photo-oxidative degradation [

15]. The samples reached equilibrium swelling were placed in a DSC capsules with an excess of solvent. In this test, a temperature ramp ranging from 25 °C to -40 °C has been programmed. The nitrogen flow rate was set at 30 mL/min, and the cooling rate was 5 °C/min.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of ELTp and ELTp-B

The aim of this study is to evaluate the effect of different recycling procedures applied to ELTp to minimize the interfacial issues with other matrices used in TPV preparation. Initially the mechanically recycled ELTp was treated by the company Cirtec with bitumen in a thermo-chemical treatment to obtain its commercial product ELTp-B for use in asphalt blends. Finally, two different recycling treatments were conducted on our laboratories on the ELTp and ELTp-B raw materials: a regeneration treatment and a devulcanization process. The first treatment was carried out on a two-roll mill, where shearing forces are applied to the material, thus breaking the rubber network randomly. On the other hand, the devulcanization treatment involves the use of an internal mixer in which the materials are subjected to high temperatures and shear forces, followed by post-treatment in a two-roll mill.

In order to characterize the effect of these recycling processes on the structure and composition of ELTp, a procedure based on solvent extraction and treatment with chemical prove was applied to all these materials derived from ELT-p. The results of this analysis are shown in

Table 5. The treatment with acetone is able to extract the organic compounds in studied samples, except for the soluble polymer. As is demonstrated in

Table 5, ETLp-B contain a greater fraction of extractable organic compounds, because of the presence of bitumen in the rubber powder.

The weight loss after the extraction with toluene quantifies the extractable non-crosslinked rubber chains in the samples, the so-called sol fraction.

Table 5 shows that the amount of sol fraction increases from the initial 2% showed by the raw ELTp until 6% after the devulcanization treatment. These results are related with the efficiency of the applied process to break the rubber network, demonstrating that regeneration method is less efficient than the devulcanization process for both ELTp and ELTp-B. At this point it is important to highlight the variation in the sol fraction produced by the thermo-chemical treatment with bitumen, reaching a value around 12% for the sample ELTp-B. This increasing in the sol fraction clearly shows the efficiency of this industrial process to breakdown the rubber network. Nevertheless, these sol fraction results are the combination of two processes, the breaking of the sulfur cross-links and the scission of the rubber chains.

The ability of the applied recycling process to selectively break the sulfur cross-links was evaluated by the selective cleavage of sulfur bonds by a chemical probe using a thiol-amine solution in toluene. The sol fraction obtained from ELTp after this treatment quantify the amount of extractable rubber after the complete cleavage of poly- and di-sulfidic cross-links, that are the treatable bonds during a selective devulcanization process. According to this statement and the results showed in

Table 5, the treatment with bitumen (sample ELTp-B) are able to increase the fraction treatable (devulcanizable) sulfur cross-links as compared with the pristine ELTp counterpart. On the other hand, when both ELTp and ELTp-B samples were submitted to a regeneration or devulcanization process, some fractions of these treatable sulfur crosslinks are actually broken, thus reducing the sol fraction extractable after the treatment with thiol-amine. In this sense, the obtained results prove that the applied devulcanization process is more selective than the regeneration treatment, although it is not able to achieve a complete breakdown of the treatable crosslinks.

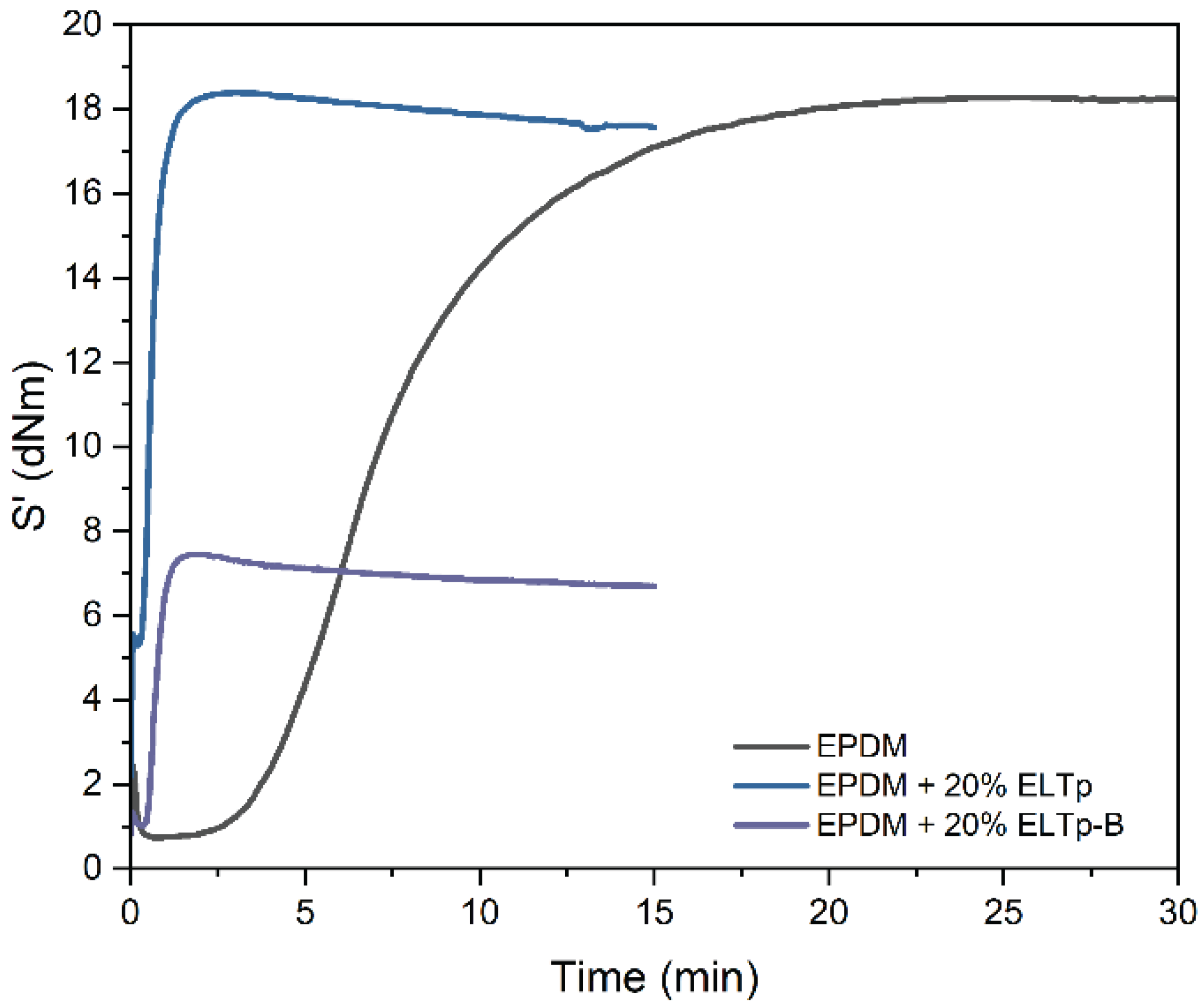

3.2. Vulcanization Curves

The vulcanization curves of the EPDM rubber compounds were measured on a Rubber Process Analyzer (RPA 2000 from Alpha Technologies) at a temperature of 170 °C with a strain amplitude of 6.98% and a frequency of 1.667 Hz. The vulcanization process was studied on a Rubber Process Analyzer, RPA 2000 from Alpha Technologies (Wiltshire, UK) at a temperature of 160°C with a strain amplitude of 6.98% at a frequency of 1.667 Hz. The time required to achieve 97% of vulcanization (t

97) for the EPDM sample was 17 minutes (see

Figure 1), supporting the successful vulcanization of EPDM phase during the mixing process with the HDPE to achieve an TPV with appropriate mechanical properties.

Figure 1 shows that incorporation of ELTp and ELTp-B to this EPDM compound reduces drastically the induction time and accelerates the cross-linking reaction. This behavior may be attributed to the strong effect of substances that contains the ELT rubber powder (e.g., processing oils, antioxidants, accelerants, and their by-products) in the re-vulcanization process. The rubber compounds filled with ELTp shows a similar maximum torque as compared to the pristine EPDM sample, whereas the minimum torque is higher. The latter may be related with the increasing viscosity of EPDM matrix by the addition of a solid vulcanized rubber particle. In contrast the sample filled with ELTp-B shows a minimum torque value quite similar to pristine EPDM compound with a lower maximum torque, because bitumen acts as a plasticizer in the compound, thus reducing the viscosity during the scorch time and the final stiffness of the rubber compound when the vulcanization process is completed.

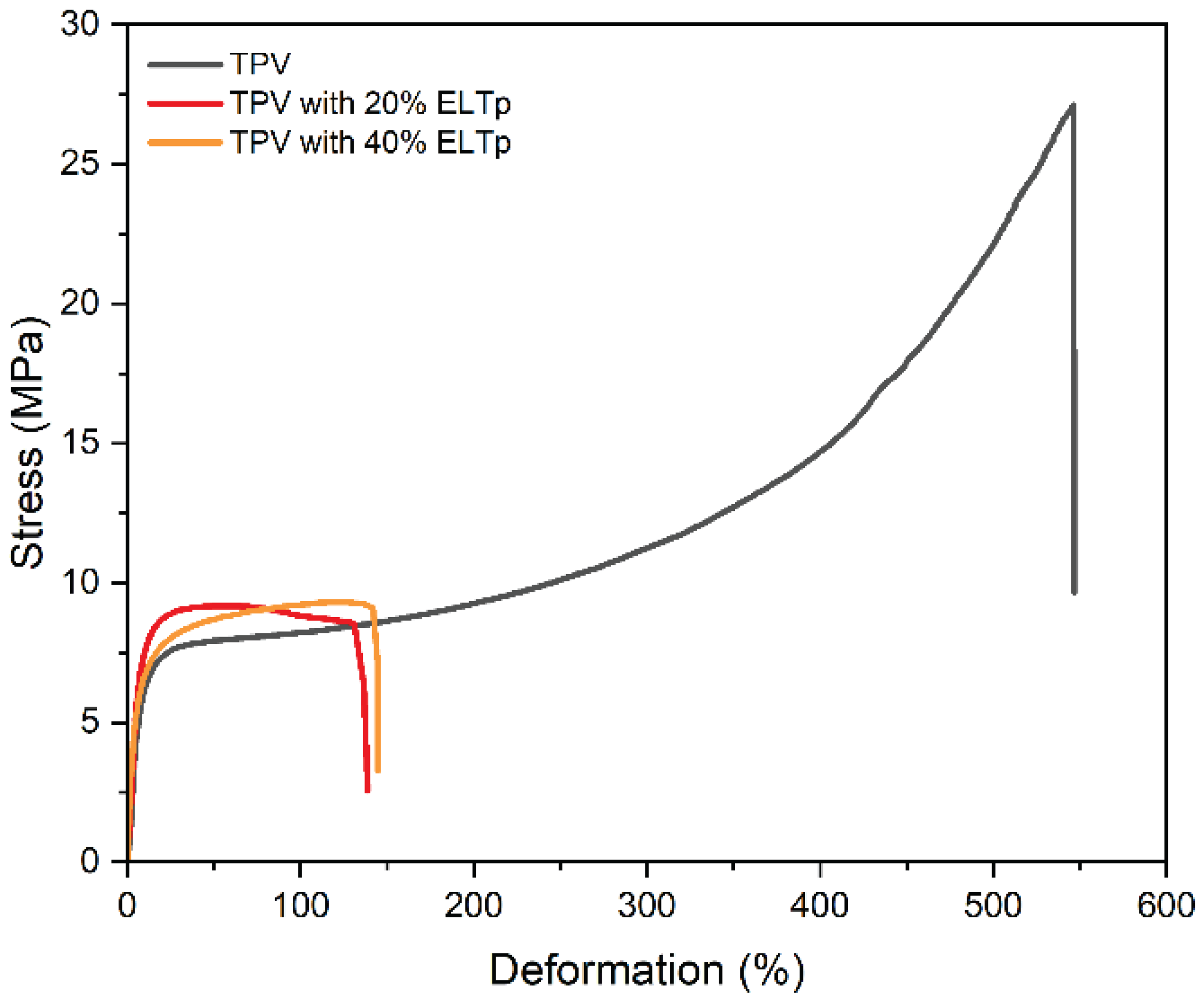

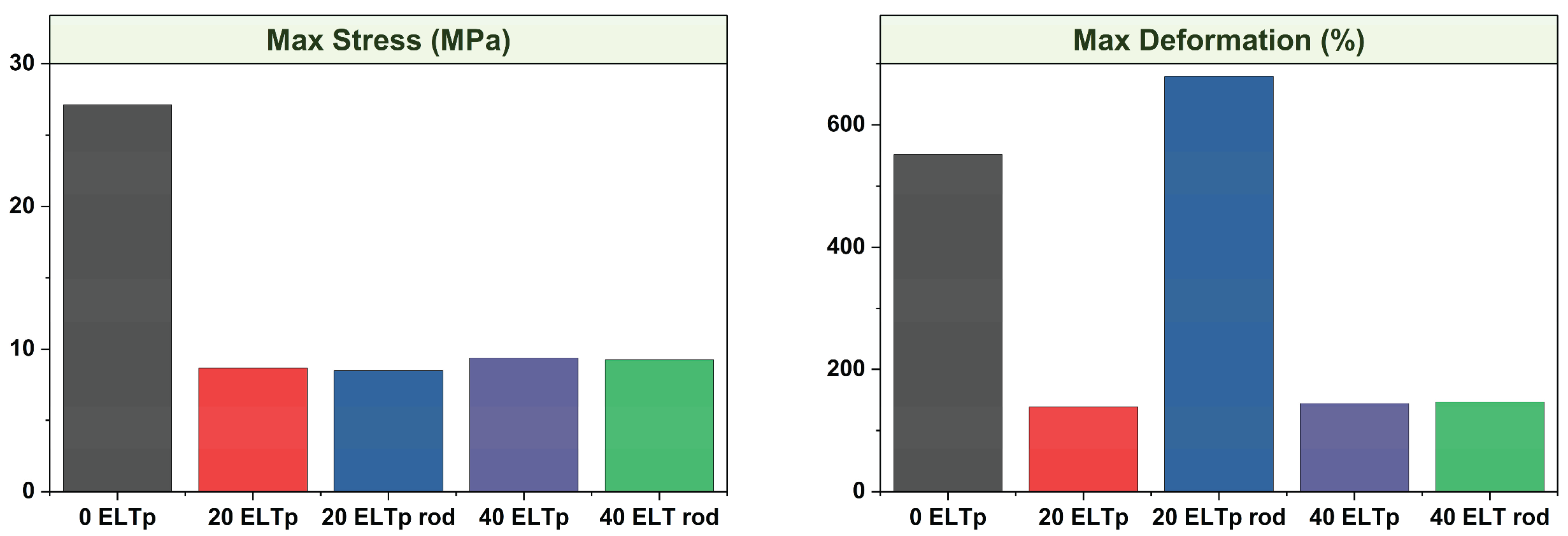

3.3. Effect of ELTp Fraction on the Mechanical Properties of TPV

Figure 2 illustrates the effect of adding different ELTp fractions on the mechanical behavior of TPV as described by their tensile stress–strain response. It was described that mechanical properties of TPV blends strongly depends on the dispersion of elastomeric phase in the thermoplastic matrix [

16], the rubber particle size [

17] and the achieved morphology, that is influenced by the cross-linking of the rubber phase during the dynamic vulcanization [

18]. Rubber particle size in the range of tens of micrometers are required to achieve enhanced ultimate tensile properties since the deformation mechanism of TPVs under tensile conditions is dominated by localized yielding of the semicrystalline thermoplastic matrix and the rubber particles of smaller sizes seem to suppress the formation of interlamellar voids [

17]. This seems to be the case of the prepared TPV blend that achieve more than 25 MPa of tensile strength and more than 500% deformation at break.

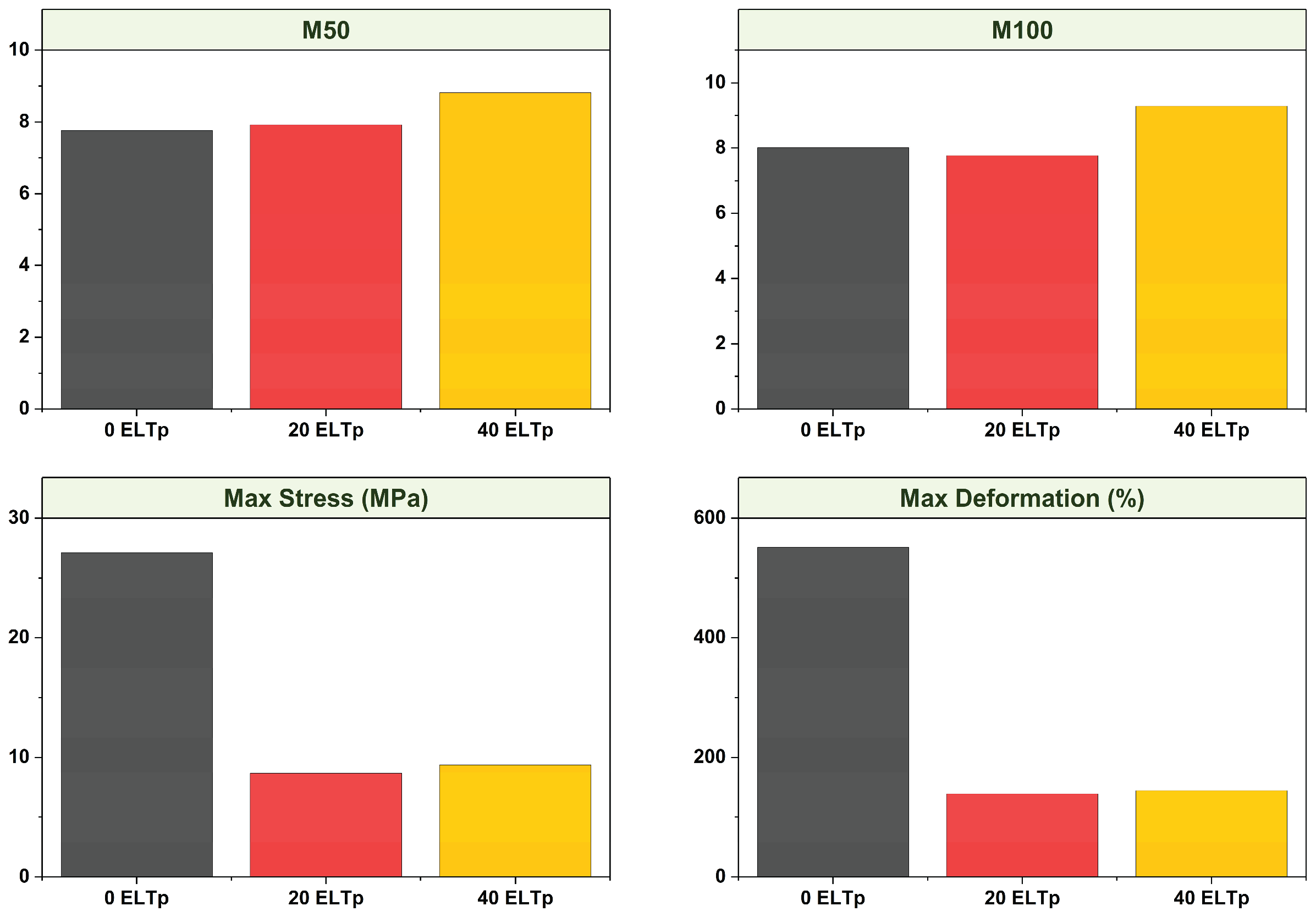

Incorporation of ELTp in the rubber phase resulted in a significant change in stress-strain curves as shown in

Figure 2. The TPVs containing 20% and 40% of ELTp show similar tensile stress behavior than the virgin TPV at the low deformation region, as it is showed in the M50 and M100 values in

Figure 3. This mechanical behavior is dominated by the semicrystalline thermoplastic matrix. For this reason, the effect of ELTp on the crystallinity of HDPE was evaluated by adjusting the melting peak enthalpy (ΔH

HDPE) corresponding only to the thermoplastic fraction in the TPVs. The results reported in

Table 6 suggest that the crystallinity of the thermoplastic matrix is not affected by the incorporation of ELTp.

However, in those samples filled with ELTp, the premature failure of the thermoplastic matrix contributes to observe a remarkable drop in the ultimate tensile properties (see

Figure 3). This behavior could be due to the presence of high amount of ELTp with particle size in the range of hundreds of microns or a poor interaction between the ELTp and the EPDM matrix.

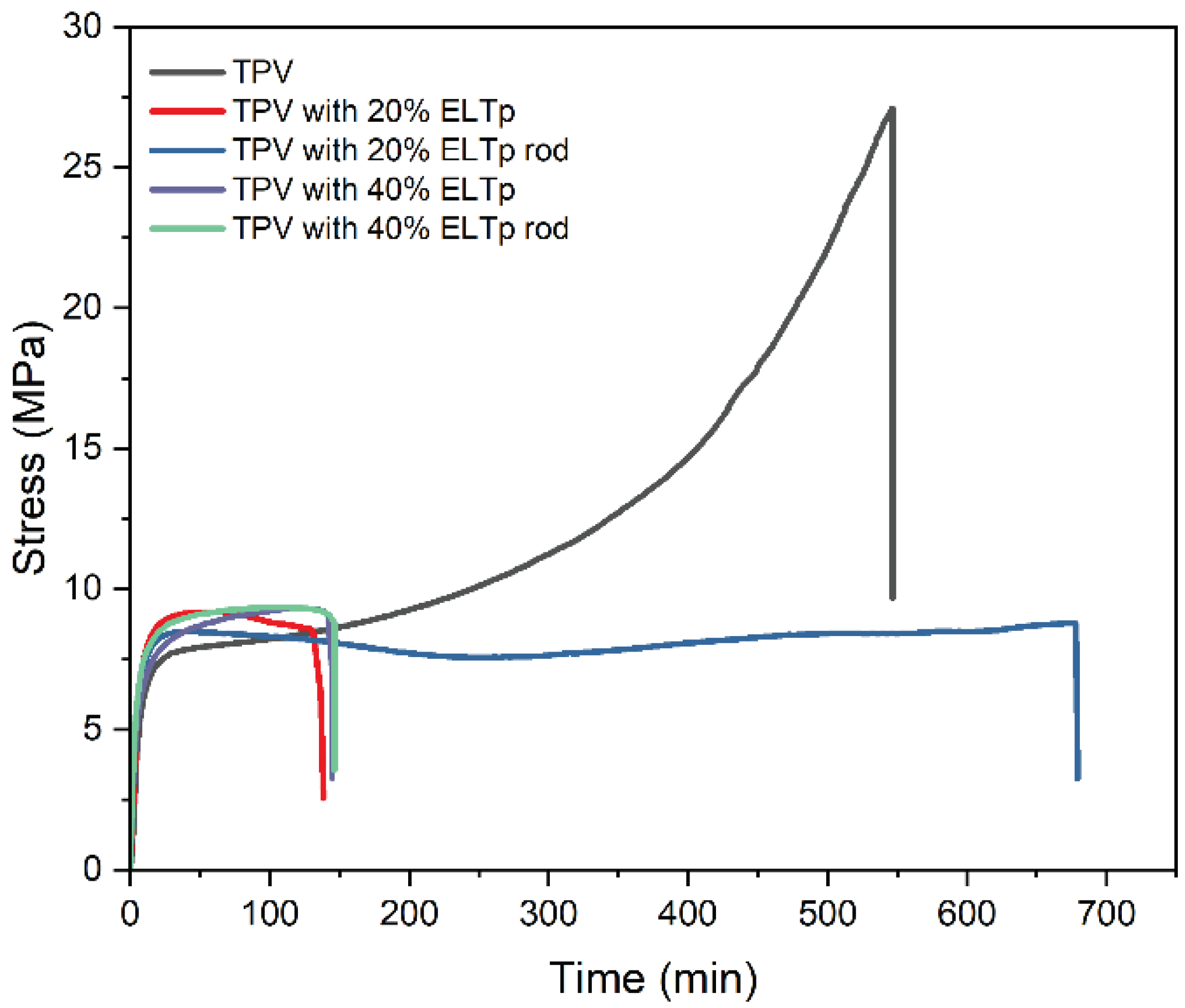

3.4. Effect of Recycling Procedures on ELTp

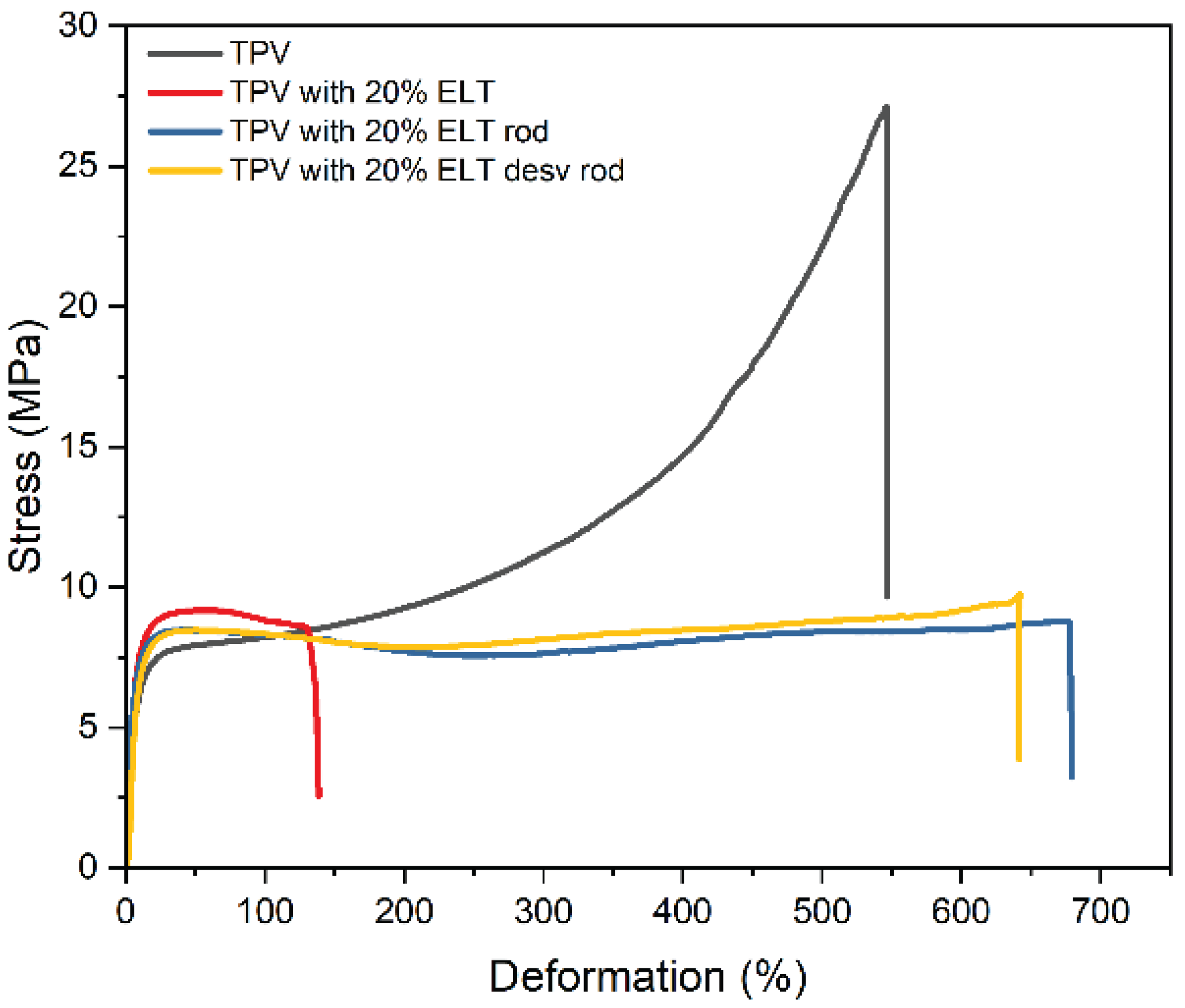

Application of regeneration and devulcanization treatments were applied to ELTp to break down the rubber network structure and increase the sol fraction in these recycled materials in order to minimize the interfacial issues between ELTp and the EPDM phase.

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the stress-strain curves and ultimate tensile properties of TPV samples with 20% and 40% ELTp that underwent the regeneration treatment (named ELTp rod), respectively. The regeneration treatment is not able to enhance the mechanical properties of the TPV that contains 40% of ELTp, however the sample that contains 20% or regenerated ELTp is able to minimize the formation of interlamellar voids in the HDPE, preventing its premature failure and contributing to achieve the high elongation behaviour typically observed in TPVs.

According to the results showed in

Table 5, (partially) devulcanized ELTp sample (named ELTp desv rod) contains higher sol fraction and lower fraction remaining sulfur cross-links than the regenerated counterpart. It can be observed that both treatments, regeneration and devulcanization, are able to increase the deformation at break in those TPV samples with 20% ELTp, although there are not noticeable differences between them (see

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

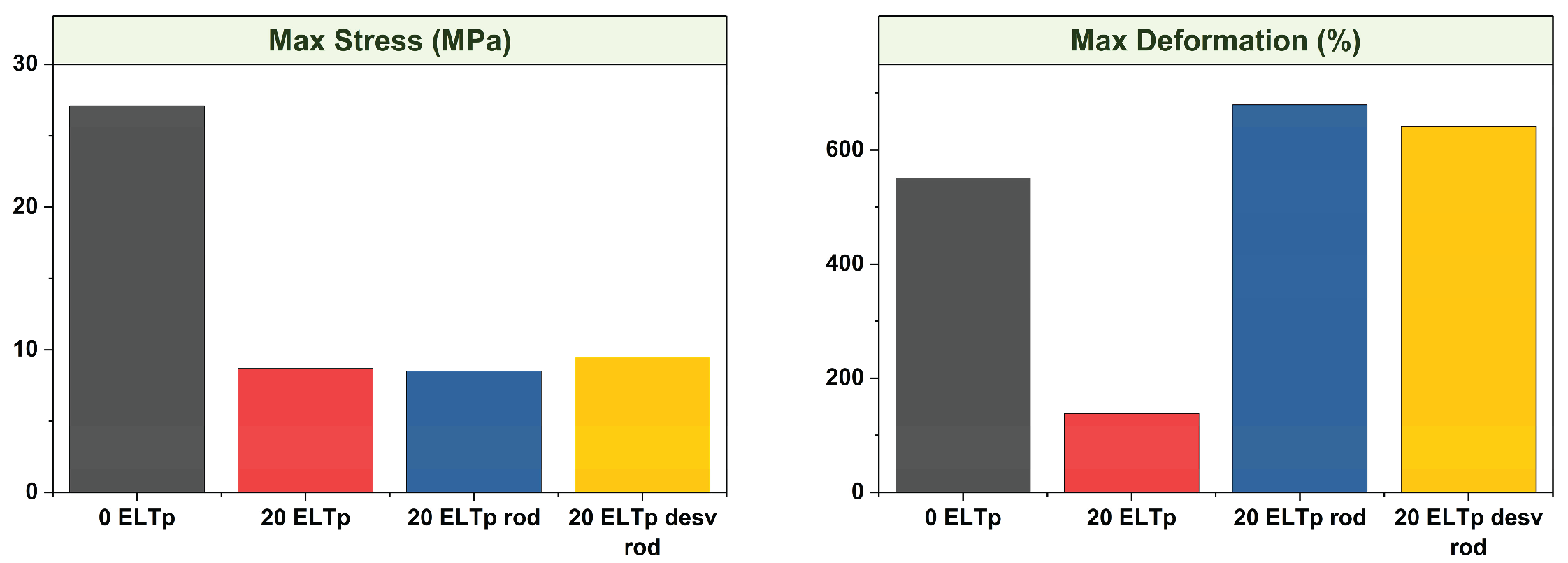

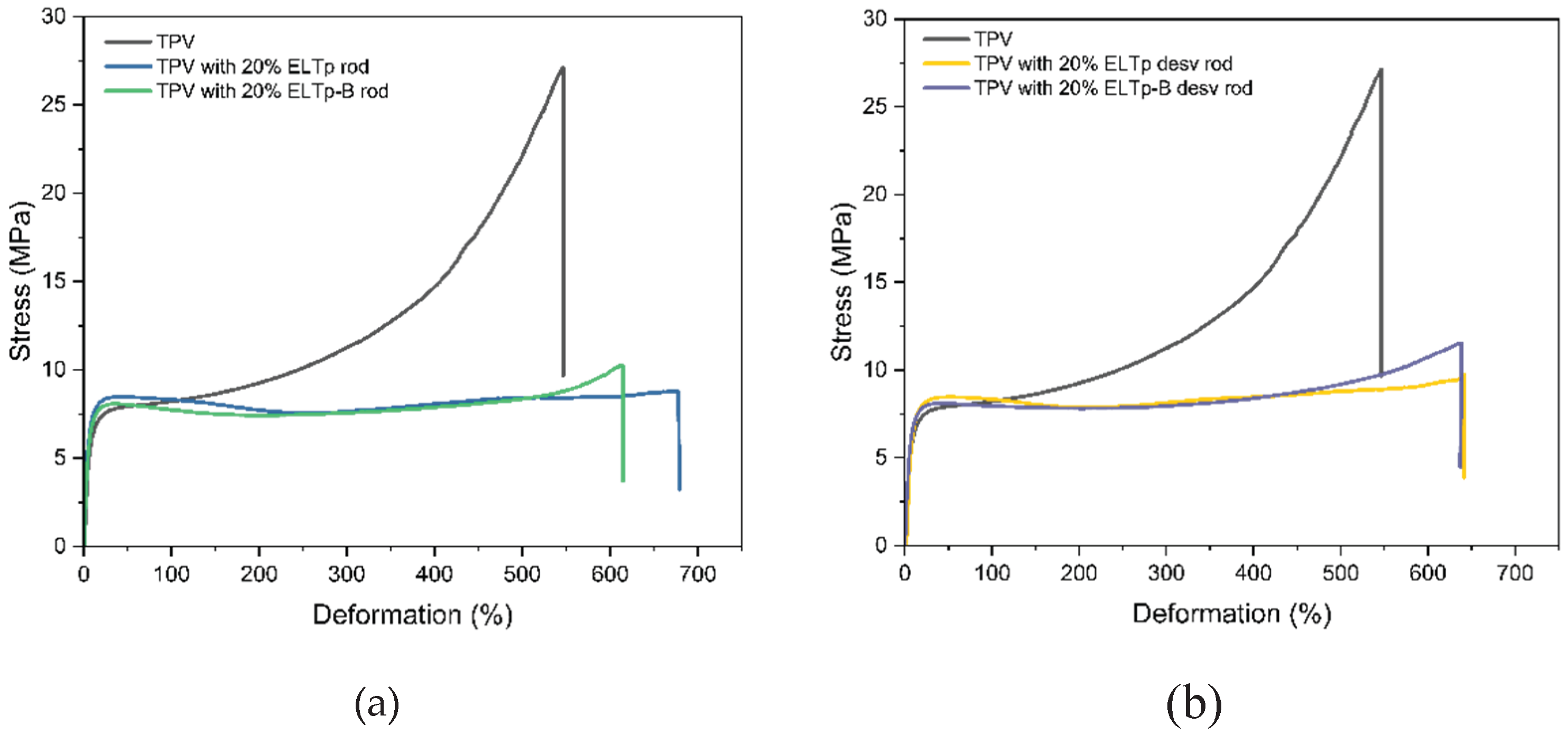

3.5. Effect of Adding ELTp with Bitumen

The mechanically recycled ELTp was treated by the company Cirtec with bitumen in a thermo-chemical treatment to obtain its commercial product ELTp-B that is able to increase the sol fraction of this product and activate it to promote the breakdown of the rubber network during the devulcanization and regeneration as compared to the non-activated pristine ELTp (see data in

Table 5).

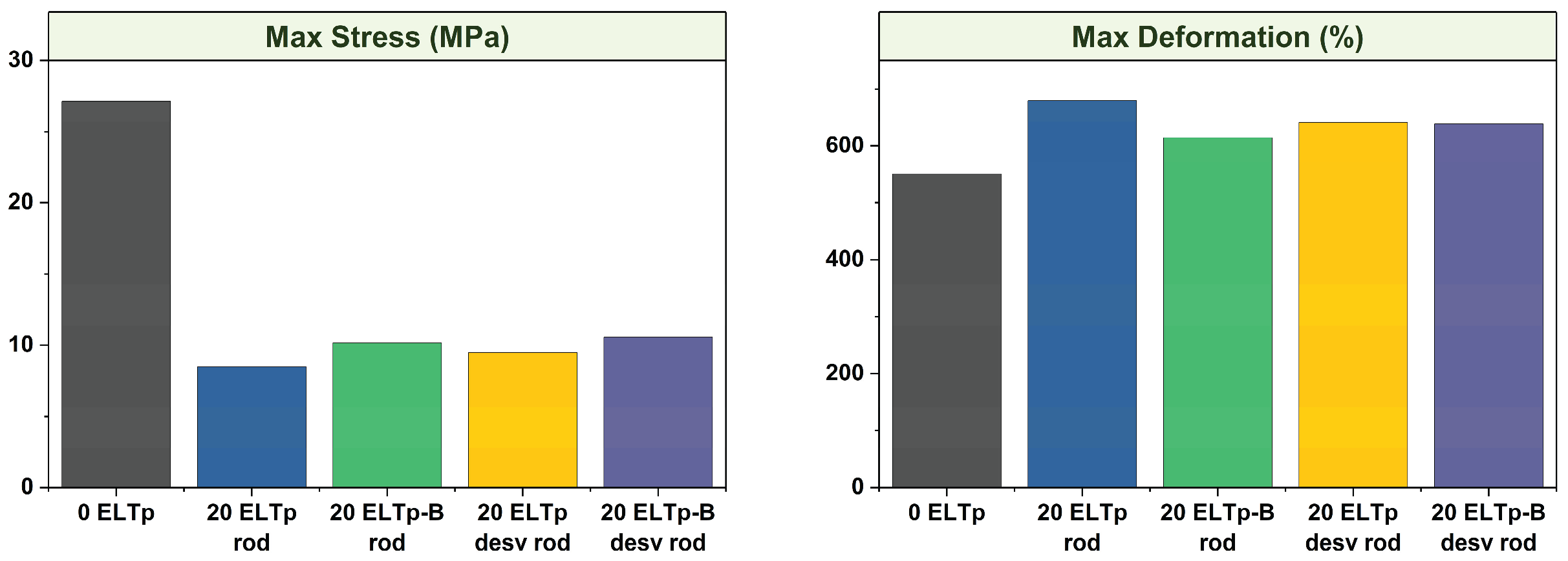

Figure 8 shows the stress-strain curves of TPVs filled with 20% ELTp and ELTp-B after subjected to the regeneration and devulcanization treatments, respectively. A similar behavior was observed for both materials, although the tensile strength of regenerated and devulcanized ELTp-B is slightly higher than the ELTp counterparts (see

Figure 9). This mechanical response may be related to two opposing mechanisms. In one hand, ELTp-B samples contain higher sol fraction, which may enhance the interactions between these recycled particles and the EPDM rubber phase. On the other hand, a significant proportion of the sulfur crosslinks are broken during the recycling processes. Although complete devulcanization cannot be achieved, the cross-link density and therefore the mechanical properties of this rubber powder are significantly modified. Additionally, ELTp-B samples contain a significant fraction of bitumen which acts as a plasticizer, softening the final TPV.

3.6. Effect of Vulcanization System

Thermo-chemical treatment of ELTp with bitumen may improve the interaction between ELTp and rubber, as well as the efficiency of recycling treatments. When ELTp has been treated, the crosslinked polymer chains break down and become available again for vulcanization. Because of this, a portion of the vulcanization system introduced into the TPV formulations may be partially consumed to re-vulcanize the devulcanized ELTp-B and thus being not available for the cross-linking reaction of less reactive EPDM rubber. The effect of adding ELTp-B on the vulcanization curve of the rubber phase is evident according to the results showed in

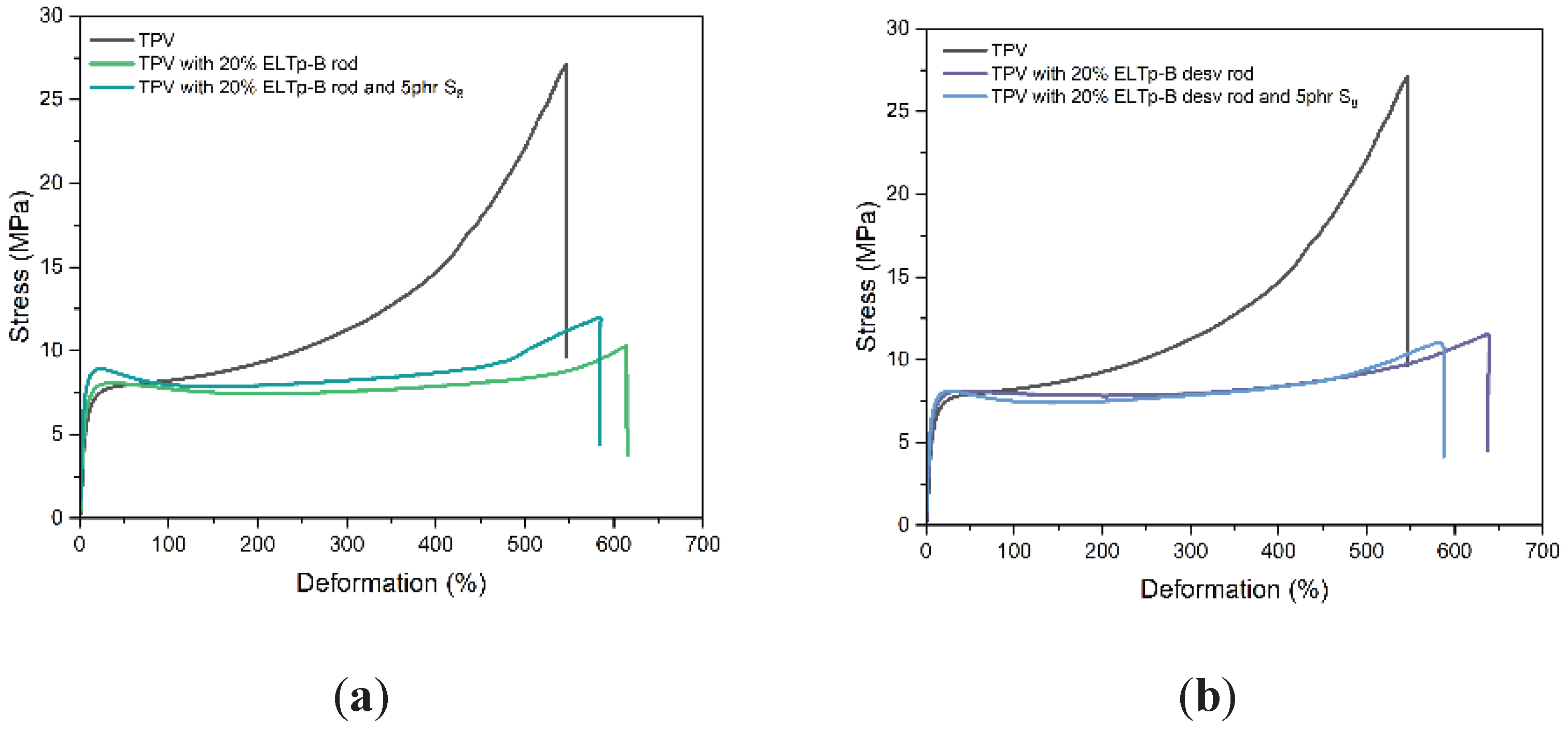

Figure 1. For this reason, incorporation of an additional amount of sulfur would assist the crosslinking reaction of the EPDM phase in the TPV.

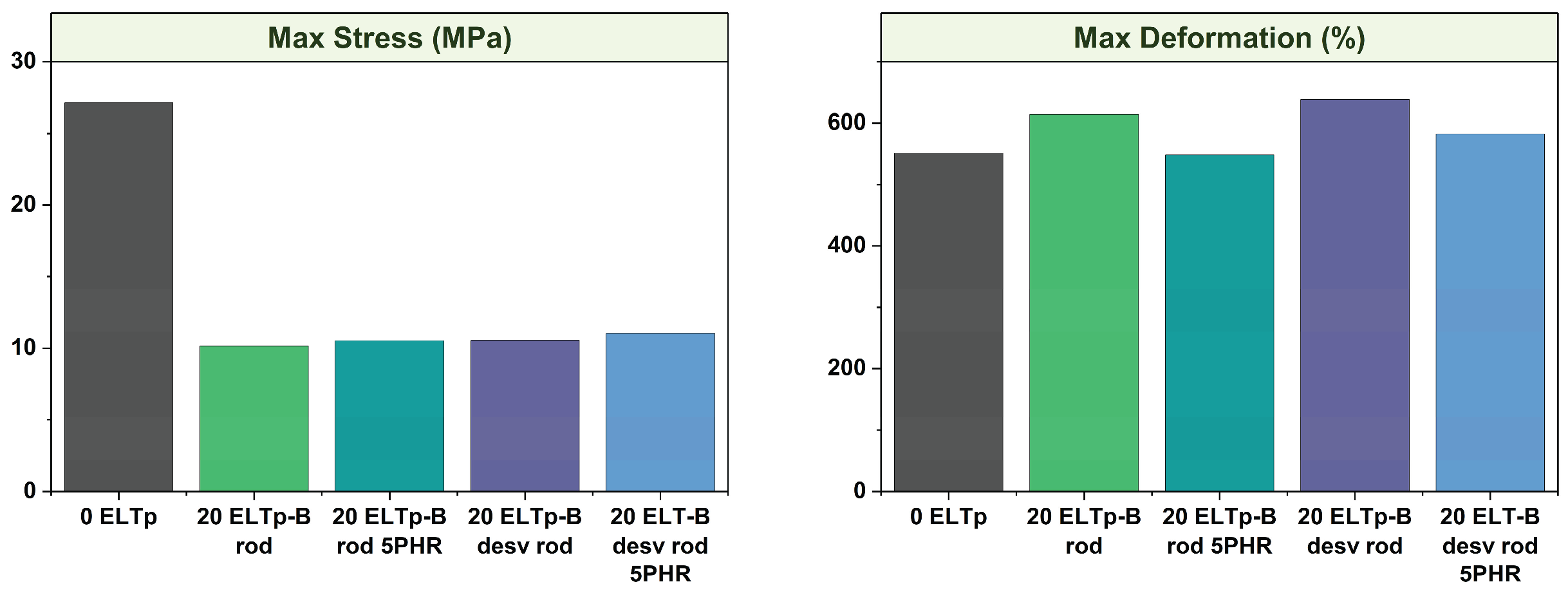

Figure 10 shows the effect of adding 5 phr of sulfur on the stress-strain curve of TPVs filled with 20% ELTp-B subjected to a regeneration treatment (a) and a devulcanization treatment (b). Although the increase in the amount of sulfur slightly enhances the tensile strength of the TPV samples (

Figure 11), this is not the main reason to explain the absence of the characteristic stress upturn at the high strain regimen (above 200%) for TPV when it is filled with recycled ELTp materials.

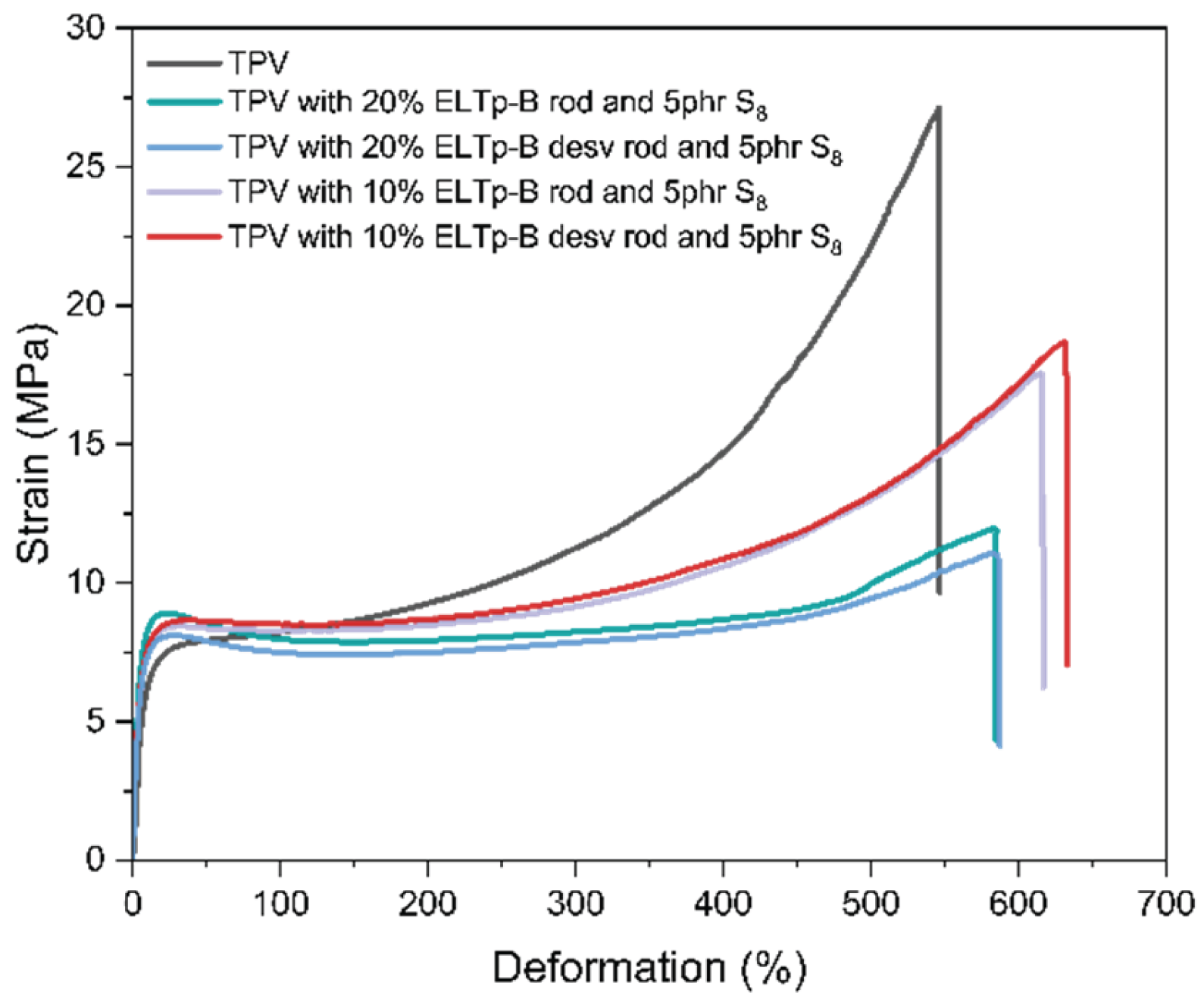

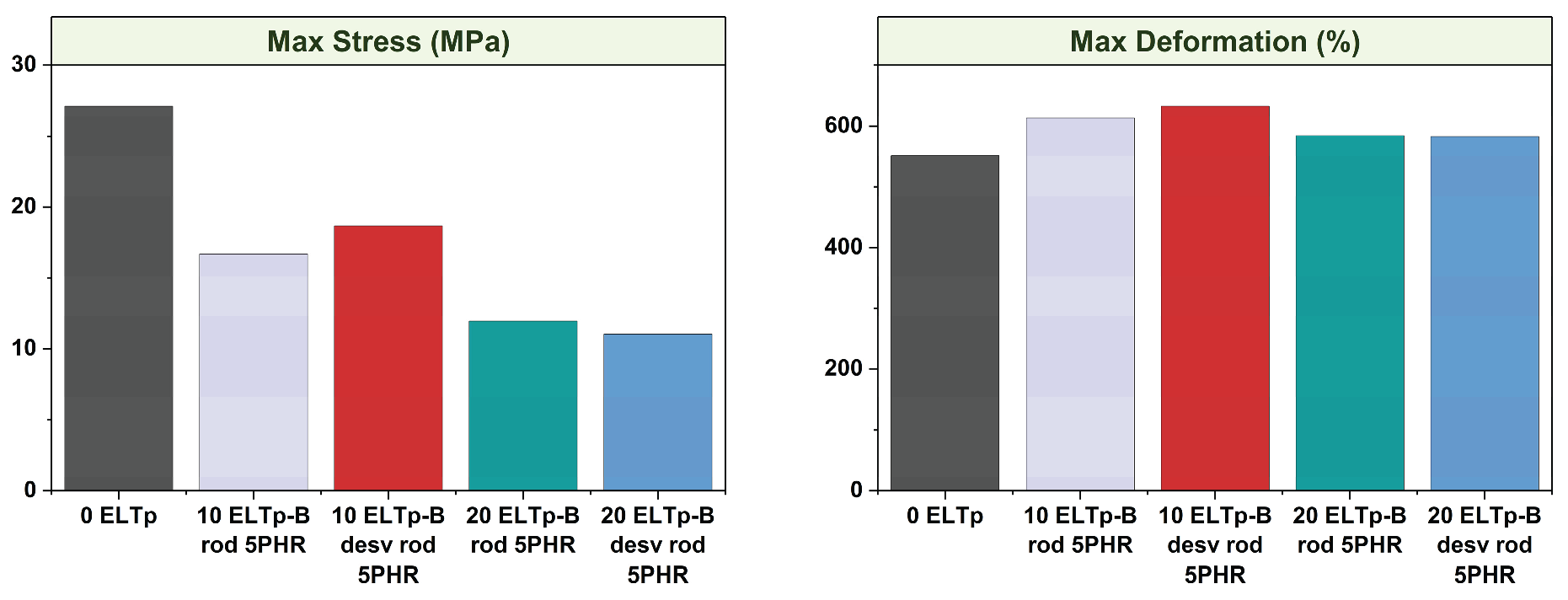

3.7. Effect of ELTp-B Fraction

An analysis of the behavior of ELTp with bitumen in thermoplastic vulcanizates (TPV), taking into account both the treatments applied and the increment in the vulcanization system, has been conducted. The findings of this analysis suggest a slight (not meaningful) enhancement in the mechanical properties of the material caused by the increment on the devulcanization degree and sol fraction of ELTp and the increment on the cross-link density in the rubber phase. Consequently, the disparity in the rubber particle size dispersed in the thermoplastic matrix seems to be the main factor that hinders the proper mechanical behavior of TPV at the high strain regimen. This difference can be explained by the comparison of ELT powder, which has a maximum particle size of 800 μm (defined as the 95-percentile) with a nominal particle size of 550 μm according to the information provided by the supplier, and EPDM droplets which may have a diameter of around tens of micrometers according to the ultimate properties of HDPE/EPDM thermoplastic vulcanizates. A decrease in the fraction of ELT powder in the TPV reduces the number of high sized rubber particles in the blend, enhancing the mechanical properties of TPV filled with these recycled ELTp-B products, as it is shown in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13.

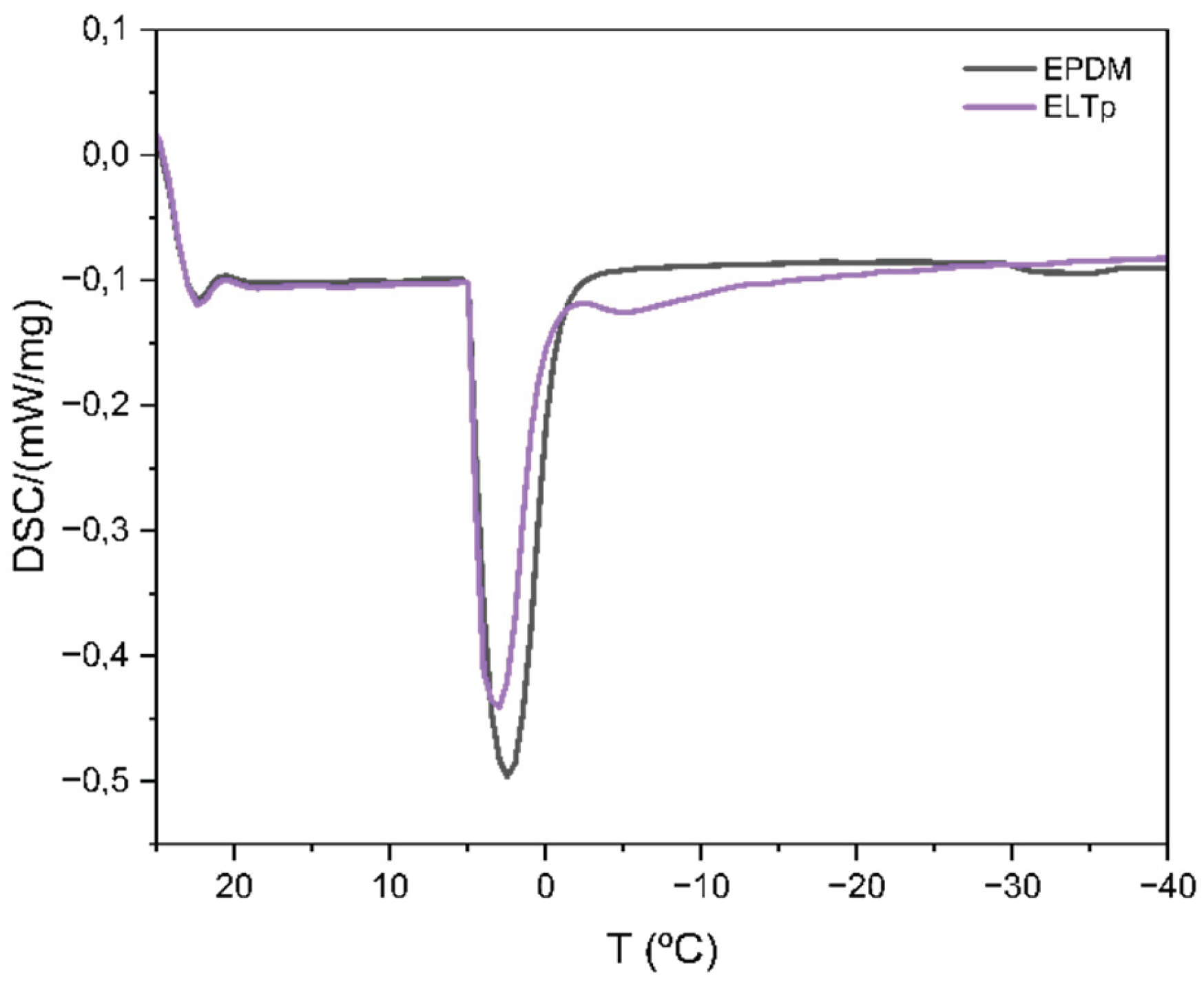

3.8. Evaluation of ELTp-EPDM Interface by Depression of the Freezing Point

In this section, the ELTp-EPDM interface will be studied by determining the freezing point depression of a solvent imbibed in the rubber compound. This experimental approach has been previously used to obtain qualitative information on the structure of the rubber network [

14] and to study filler-rubber interactions [

15,

20]. In the case of the unfilled EPDM rubber sample, two peaks attributed to freezing process of the solvent outside (higher freezing temperature above 0 °C) and inside (lower freezing temperature below -30 °C) the rubber matrix are observed (see

Figure 14). The anomalous low-temperature shift of peak attributed to the solvent that is swelling the rubber network is caused by the small mesh size of the polymer network that interferes in the nucleation process of cyclohexane. Consequently, the depression of the freezing point can be related with the cross-link density of EPDM sample and hence the dimensional constraints that it causes on the solvent nucleation.

Figure 14 shows that in the case of ELTp sample, although it is possible to discriminate two freezing peaks, the freezing temperature of the solvent inside the rubber matrix is only slightly shifted towards lower temperatures as compared to the freezing peak attributed to the solvent excess that is in the DSC pan. This is caused by the decrease in the size restrictions inside the rubber compounds and should be related with a rubber network with lower cross-link density or more probable, with the presence of larger empty spaces at the filler-rubber interface (with reduced dimensional constraints for solvent nucleation) in these ELTp samples.

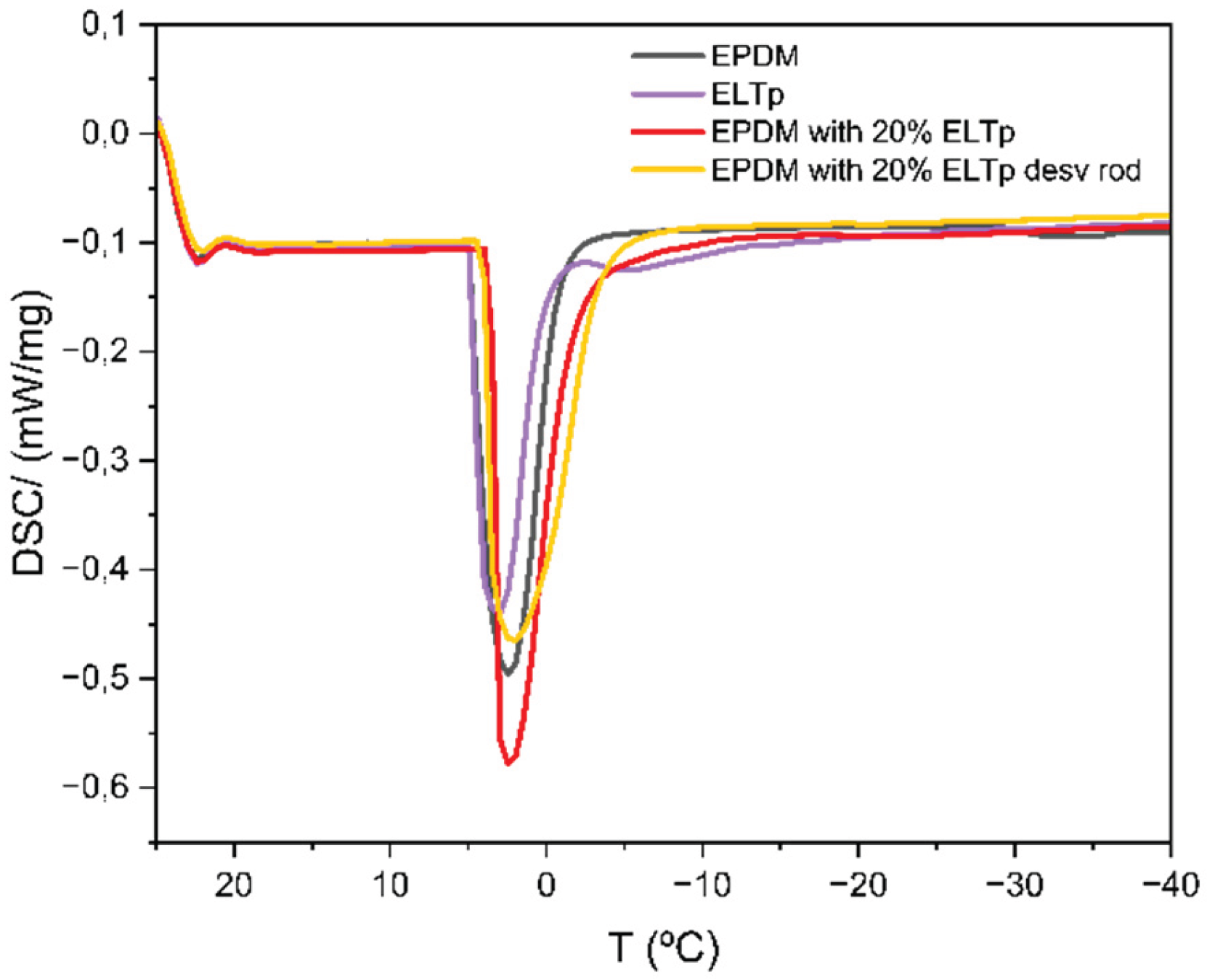

Figure 15 shows the DSC freexing curves of cyclohexane in swollen EPDM filled with pristine ELTp and with devulcanized ELTp, respectively. In both cases, only one freezing peak is observed. It means that solvent imbibed in these vulcanized rubber samples does not find any dimensional constraint to nucleate (as compared to the solvent in the DSC pan) because a considerable fraction the solvent is in larger empty vacuoles, where the freezing process starts. This behavior is not modified with the devulcanization treatment of ELTp, reflecting that in both cases a lack of interactions at the ELTp-EPDM interface.

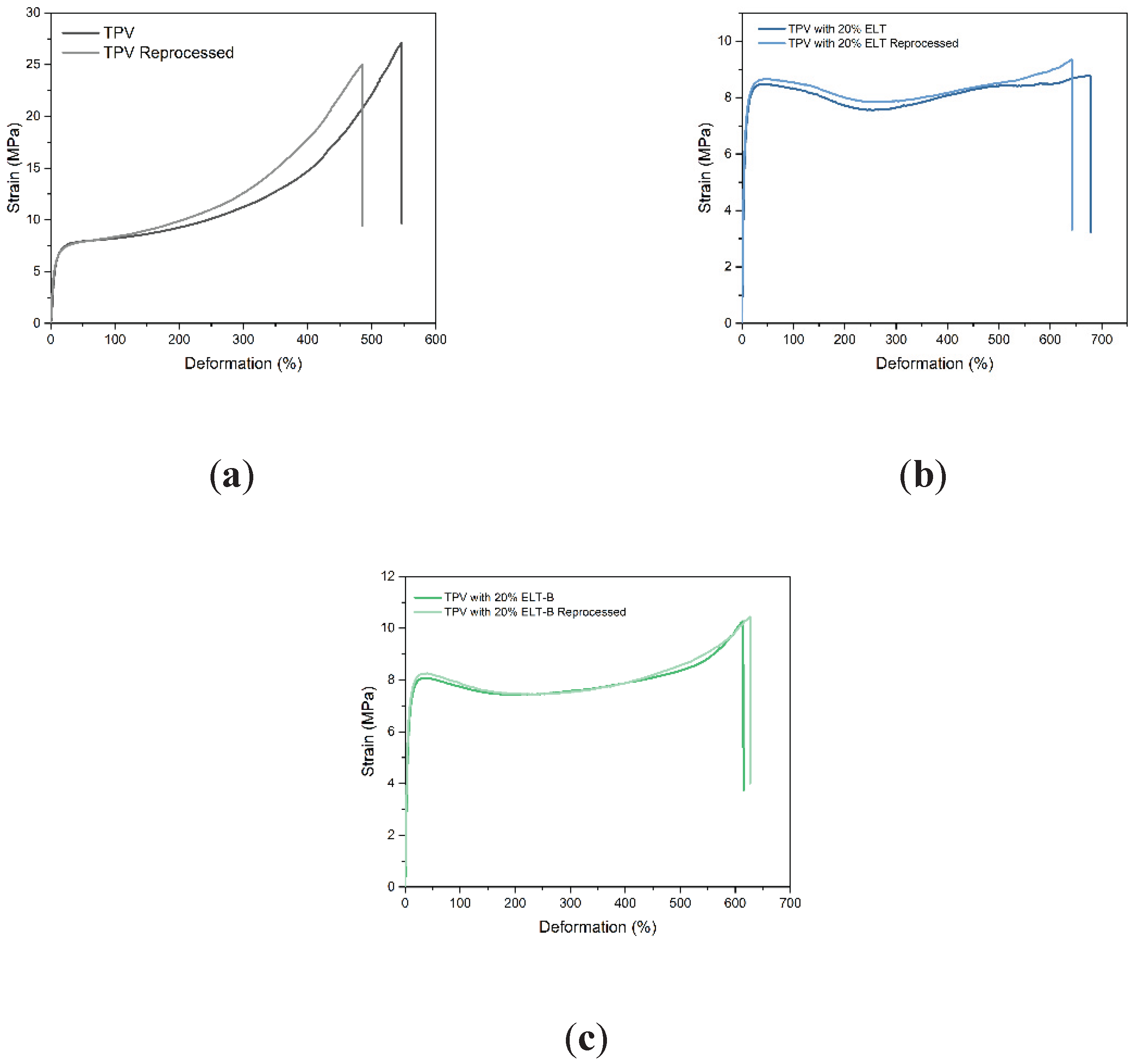

3.9. TPV Reprocessing

Vulcanized thermoplastic materials can be reprocessed while preserving their original mechanical properties.

Figure 16 shows that incorporation of ELTp and ELTp-B does not disturb the re-processability properties of these TPVs, maintained their mechanical properties, thereby emphasizing their technological, economic, and environmental relevance.

4. Conclusions

Mechanical recycling of end-of-life tyres provides a rubber powder (ELTp) which can be used as secondary raw material in rubber industry, including vulcanized thermoplastic elastomers (TPVs). The results obtained in this work provide relevant evidences about the challenges and difficulties of using ELTp as filler in TPVs based on HDPE/EPDM blends, including higher viscosity, interferences in the dynamic vulcanization process, poor compatibility with other rubber/thermoplastic matrices and the large rubber particle size.

The particle size of the ELTp (in the range of in the range of hundreds of microns) is considerably larger than the EPDM droplets (in the range of tens of microns) dispersed in the thermoplastic matrix. This limits the mechanical performance of these TPVs when this secondary raw material is incorporated at elevated concentrations (higher than 20% w/w). Although the crystallinity of HDPE remains unaffected by the presence of ELTp, resulting in an almost unaltered mechanical response in the low strain regime (below 100% deformation), the premature failure of the thermoplastic matrix contributes to observe a remarkable drop in the ultimate tensile properties of TPVs.

In order to address these difficulties, different recycling procedures based on thermal, chemical and mechanical methods, and combinations thereof were applied to ELT-p. In particular, ELTp was treated with bitumen in a thermo-chemical treatment that was demonstrated an efficient industrial process to breakdown the rubber network, increasing the rubber sol fraction up to 12%. This commercially available material (named ELTp-B in this manuscript) is able to increase the fraction treatable (devulcanizable) sulfur cross-links as compared with the pristine ELTp counterpart, thus activating this material for further recycling processes. Finally, two different recycling treatments were conducted on our laboratories on the ELTp and ELTp-B raw materials: a regeneration treatment and a devulcanization process. It was proved that the applied devulcanization process is more selective than the regeneration treatment, although it is not able to achieve a complete breakdown of the treatable crosslinks.

The ELTp based materials obtained after the application of these recycling treatments showed similar behavior regarding the mechanical properties of the TPV when they are used as fillers, resulting in a substantial improvement in the mechanical properties of the final product. In this sense, all TPV samples that were filled with 20% w/w of recycled ELTp are able to minimize the formation of interlamellar voids in the HDPE, preventing its premature failure and contributing to achieve the high elongation behavior typically observed in TPVs. It is important to note that the bitumen present in the ELTp-B based materials acted as a plasticizer, thereby reducing the viscosity of those materials.

It was established that an increase in the quantity of vulcanizing agents (sulfur) has favorable effects on the mechanical properties of TPVs when devulcanized ELTp is applied as filler. Nevertheless, the fraction of treated ELTp incorporated in the rubber phase is the main factor that modifies (optimizes) the mechanical properties of TPVs.

This work demonstrates that treated ELTp is a viable and sustainable raw material to be used in the rubber phase in TPV formulations, contributing to the development of sustainable strategies for the recovery of tyre waste, thus opening new perspectives for its integration into products of commercial interest.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MINECO) under grants PID2020-119047RB-I00, PLEC2021-00779 and PID2023-147542OB-I00 and EU under the program ERASMUS-EDU-2022-PI-ALL-INNO-BLUEPRINT, project 101103234.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MINECO) and EU for the partial financial support of this work (PID2020-119047RB-I00, PLEC2021-00779, PID2023-147542OB-I00 and ERASMUS-EDU-2022-PI-ALL-INNO-BLUEPRINT, project 101103234). Authors thank the companies Valoriza Medioambiente and Cirtec for providing materials for this study. MNF acknowledges Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MINECO) for her PhD grant PREP2023-001425. All authors are members of the SusPlast platform from the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC).

References

- Sienkiewicz, M.; Kucinska-Lipka, J.; Janik, H.; Balas, A. Progress in used tyres management in the European Union: A review. Waste Management 2012, 32, 1742–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markl, E.; Lackner, M. Devulcanization Technologies for Recycling of Tire-Derived Rubber: A Review. Materials 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemi, M.; Zarmehr, S. P.; Yazdani, H.; Fini, E. Review and Perspectives of End-of-Life Tires Applications for Fuel and Products. Energy & Fuels 2023, 37, 10758–10774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Pramanik, A.; Basak, A. K.; Prakash, C.; Shankar, S. Material recovery and recycling of waste tyres-A review. Cleaner Materials 2022, 5, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sienkiewicz, M.; Kucinska-Lipka, J.; Janik, H.; Balas, A. Progress in used tyres management in the European Union: A review. Waste Management 2012, 32, 1742–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legge, N. R.; Holden, G.; Schroeder, H. E. Thermoplastic elastomers: A Comprehensive Review; 1987.

- Markl, E.; Lackner, M. Devulcanization Technologies for Recycling of Tire-Derived Rubber: A Review. Materials 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archibong, F. N.; Sanusi, O. M.; Médéric, P.; Hocine, N. A. An overview on the recycling of waste ground tyre rubbers in thermoplastic matrices: Effect of added fillers. Resources Conservation And Recycling 2021, 175, 105894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A. B.; Chatterjee, T.; Naskar, K. Automotive applications of thermoplastic vulcanizates. Journal Of Applied Polymer Science 2020, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazli, A.; Rodrigue, D. Waste Rubber Recycling: A Review on the Evolution and Properties of Thermoplastic Elastomers. Materials 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S. L.; Xin, Z. X.; Zhang, Z. X.; Kim, J. K. Characterization of the properties of thermoplastic elastomers containing waste rubber tire powder. Waste Management 2008, 29, 1480–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.-S.; Kim, E. A novel system for measurement of types and densities of sulfur crosslinks of a filled rubber vulcanizate. Polymer Testing 2014, 42, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNE-ISO 37:2013. “Rubber vulcanized or thermoplastic. Determination of tensile stress-strain properties”.

- Valentín, J. L.; Fernández--Torres, A.; Posadas, P.; Marcos--Fernández, A.; Rodríguez, A.; González, L. Measurements of freezing--point depression to evaluate rubber network structure. Crosslinking of natural rubber with dicumyl peroxide. Journal Of Polymer Science Part B Polymer Physics 2007, 45, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentín, J. L.; Mora-Barrantes, I.; Carretero-González, J.; López-Manchado, M. A.; Sotta, P.; Long, D. R.; Saalwächter, K. Novel Experimental Approach to Evaluate Filler−Elastomer Interactions. Macromolecules 2009, 43, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Hel, C.; Bounor-Legaré, V.; Catherin, M.; Lucas, A.; Thevenon, A.; Cassagnau, P. TPV: A New Insight on the Rubber Morphology and Mechanic/Elastic Properties. Polymers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- l’Abee, R. M. A.; van Duin, M.; Spoelstra, A. B.; Goossens, J. G. P. The rubber particle size to control the properties-processing balance of thermoplastic/cross-linked elastomer blends. Soft Matter 2010, 6, 1758–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Tian, M.; Zhang, L.; Tian, H.; Wu, Y.; Ning, N; Chan, T. W. New Understanding of Morphology Evolution of Thermoplastic Vulcanizate (TPV) during Dynamic Vulcanization. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, C. A. Polymer handbook: Third edition Edited by J. Brandrup and E. H. Immergut, Wiley--Interscience, Chichester, 1989. ISBN 0–471–81244–7. British Polymer Journal 1990, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Manchado, M. A.; Valentín, J. L.; Herrero, B.; Arroyo, M. Novel approach of evaluating polymer nanocomposite structure by measurements of the freezing-point depression. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2004, 25, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Vulcanization curves of EPDM compound and the effect of filling with ELTp and ELTp-B, respectively.

Figure 1.

Vulcanization curves of EPDM compound and the effect of filling with ELTp and ELTp-B, respectively.

Figure 2.

Stress-Strain curves of TPV and TPV filled with different fraction of ELTp.

Figure 2.

Stress-Strain curves of TPV and TPV filled with different fraction of ELTp.

Figure 3.

Mechanical properties of TPV with 0%, 20%, and 40% ELTp.

Figure 3.

Mechanical properties of TPV with 0%, 20%, and 40% ELTp.

Figure 4.

Stress-Strain curves of TPV and TPV filled with different fraction of ELTp and regenerated ELTp rod.

Figure 4.

Stress-Strain curves of TPV and TPV filled with different fraction of ELTp and regenerated ELTp rod.

Figure 5.

Ultimate tensile properties of TPVs with 0%, 20%, and 40% ELTp (pristine and regenerated).

Figure 5.

Ultimate tensile properties of TPVs with 0%, 20%, and 40% ELTp (pristine and regenerated).

Figure 6.

Stress-Strain curves of TPV and TPV filled with 20% pristine ELTp, and after regeneration (ELTp rod) and devulcanization treatments (ELTp desv rod).

Figure 6.

Stress-Strain curves of TPV and TPV filled with 20% pristine ELTp, and after regeneration (ELTp rod) and devulcanization treatments (ELTp desv rod).

Figure 7.

Ultimate tensile properties of TPVs with 0% and 20% pristine ELTp, and after regeneration (ELTp rod) and devulcanization treatments (ELTp desv rod).

Figure 7.

Ultimate tensile properties of TPVs with 0% and 20% pristine ELTp, and after regeneration (ELTp rod) and devulcanization treatments (ELTp desv rod).

Figure 8.

Stress-strain curves of TPV and TPV filled with 20% of (a) regenerated ELTp and ELTp-B and (b) devulcanized ELTp and ELTp-B.

Figure 8.

Stress-strain curves of TPV and TPV filled with 20% of (a) regenerated ELTp and ELTp-B and (b) devulcanized ELTp and ELTp-B.

Figure 9.

Ultimate tensile properties of TPV and TPV filled with 20% of ELTp and ELTp-B after regeneration and devulcanization treatments.

Figure 9.

Ultimate tensile properties of TPV and TPV filled with 20% of ELTp and ELTp-B after regeneration and devulcanization treatments.

Figure 10.

Effect of increasing the amount of sulfur on the stress-strain curves TPV blends filled with 20% of a) regenerated and b) devulcanized ELTp-B.

Figure 10.

Effect of increasing the amount of sulfur on the stress-strain curves TPV blends filled with 20% of a) regenerated and b) devulcanized ELTp-B.

Figure 11.

Effect of increasing the amount of sulfur on the ultimate properties of TPV blends filled with 20% of regenerated and devulcanized ELTp-B.

Figure 11.

Effect of increasing the amount of sulfur on the ultimate properties of TPV blends filled with 20% of regenerated and devulcanized ELTp-B.

Figure 12.

Stress-Strain curves of TPV blends filled with a variable fraction of recycled (regenerated and devulcanized) ELTp-B and 5 phr of sulfur.

Figure 12.

Stress-Strain curves of TPV blends filled with a variable fraction of recycled (regenerated and devulcanized) ELTp-B and 5 phr of sulfur.

Figure 13.

Ultimate properties of TPV blends filled with a variable fraction of recycled (regenerated and devulcanized) ELTp-B and 5 phr of sulfur.

Figure 13.

Ultimate properties of TPV blends filled with a variable fraction of recycled (regenerated and devulcanized) ELTp-B and 5 phr of sulfur.

Figure 14.

DSC freezing curves of cyclohexane in swollen EPDM and pristine ELTp.

Figure 14.

DSC freezing curves of cyclohexane in swollen EPDM and pristine ELTp.

Figure 15.

DSC freezing curves of cyclohexane in swollen EPDM samples filled with pristine ELTp and devulcanized ELTp.

Figure 15.

DSC freezing curves of cyclohexane in swollen EPDM samples filled with pristine ELTp and devulcanized ELTp.

Figure 16.

Stress-strain curves of reprocessed TPV. a) TPV pre-processing without recycled material. b) TPV pre-processing with 20% ELTp and regeneration treatment. c) TPV pre-processing with 20% ELTp-B and regeneration treatment.

Figure 16.

Stress-strain curves of reprocessed TPV. a) TPV pre-processing without recycled material. b) TPV pre-processing with 20% ELTp and regeneration treatment. c) TPV pre-processing with 20% ELTp-B and regeneration treatment.

Table 1.

Recipe of the virgin TPV.

Table 1.

Recipe of the virgin TPV.

| Ingredient |

Amount (phr) |

| HDPE |

124.95 |

| EPDM |

100.00 |

| ZnO |

5.01 |

| Stearic acid |

1.02 |

| TMTD |

1.02 |

| MBTS |

0.48 |

| S8

|

1.99 |

Table 2.

TPV blends with 20% and 40% ELTp/ELTp-B.

Table 2.

TPV blends with 20% and 40% ELTp/ELTp-B.

| |

20% ELT-p |

40% ELT-p |

| Ingredient |

phr |

phr |

| HDPE |

171.75 |

326.75 |

| EPDM |

100.00 |

100.00 |

| ELTp/ELTp-B 1

|

72.04 |

310.61 |

| ZnO |

6.89 |

13.10 |

| Stearic acid |

1.41 |

2.68 |

| TMTD 2

|

1.41 |

2.68 |

| MBTS 3

|

0.67 |

1.27 |

| Sulphur |

2.74 |

5.21 |

Table 3.

Reformulation of TPV blends with 20% ELT-p.

Table 3.

Reformulation of TPV blends with 20% ELT-p.

| Ingredient |

Amount (phr) |

| HDPE |

171.75 |

| EPDM |

100.00 |

| ELTp/ELTp-B |

72.04 |

| ZnO |

6.89 |

| Stearic acid |

1.41 |

| TMTD 2* |

2.57 |

| MBTS 3* |

1.22 |

| Sulphur |

5.00 |

Table 4.

TPV blends with 10% and 20% ELTp-B.

Table 4.

TPV blends with 10% and 20% ELTp-B.

| |

10% |

20% |

| Ingredient |

Amount (phr) |

Amount (phr) |

| HDPE |

143.40 |

171.75 |

| EPDM |

100.00 |

100.00 |

| ELTp-B |

28.41 |

72.04 |

| ZnO |

5.75 |

6.89 |

| Stearic acid |

1.17 |

1.41 |

| TMTD 2* |

2.57 |

2.57 |

| MBTS 3* |

1.22 |

1.22 |

| Sulphur |

5.00 |

5.00 |

Table 5.

Percentage of weight loss after solvent extraction and chemical probe treatment for ELTp and ELTp-B samples subjected to different recycling treatments.

Table 5.

Percentage of weight loss after solvent extraction and chemical probe treatment for ELTp and ELTp-B samples subjected to different recycling treatments.

| |

Initial |

Regeneration |

Devulcanization |

| |

ELTp |

ELTp-B |

ELTp Rod |

ELTp-B rod |

ELTp desv rod |

ELTp-B desv rod |

| Acetone |

8.6 |

19.7 |

6.3 |

13.7 |

7.1 |

26.8 |

| Toluene |

2.0 |

11.8 |

3.1 |

10.4 |

6.4 |

14.6 |

| Thiol-Toluene |

19.0 |

35.2 |

16.0 |

19.5 |

7.8 |

13.5 |

Table 6.

Crystallinity of HDPE in TPV compounds with 20% and 40% ELTp.

Table 6.

Crystallinity of HDPE in TPV compounds with 20% and 40% ELTp.

| Material |

ΔHtot (J/g) |

ΔHHDPE (J/g) |

Crystallinity (%) |

| Theorical HDPE [19] |

293 |

293 |

100 |

| Experimental HDPE |

193,9 |

193,9 |

66,2 |

| TPV |

100,3 |

188,2 |

64,2 |

| TPV with 20% ELTp |

94,34 |

196,0 |

66,9 |

| TPV with40% ELTp |

71,25 |

166,2 |

56,7 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).