Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Motivation

2.2. Key Notions

2.2.1. Intelligent Transportation Systems

- Proactive capabilities: ITS employ techniques from artificial intelligence and predictive analytics to implement preemptive measures and anticipate potential issues.

- Data-driven nature: ITS continuously collect and analyze large volumes of data to optimize system performance.

- User-centric orientation: ITS prioritize delivering personalized guidance and real-time information to travelers, thereby enhancing the overall travel experience.

- Interconnected architecture: ITS leverage advanced information and communication technologies to enable seamless data exchange between infrastructure, vehicles, and travelers.

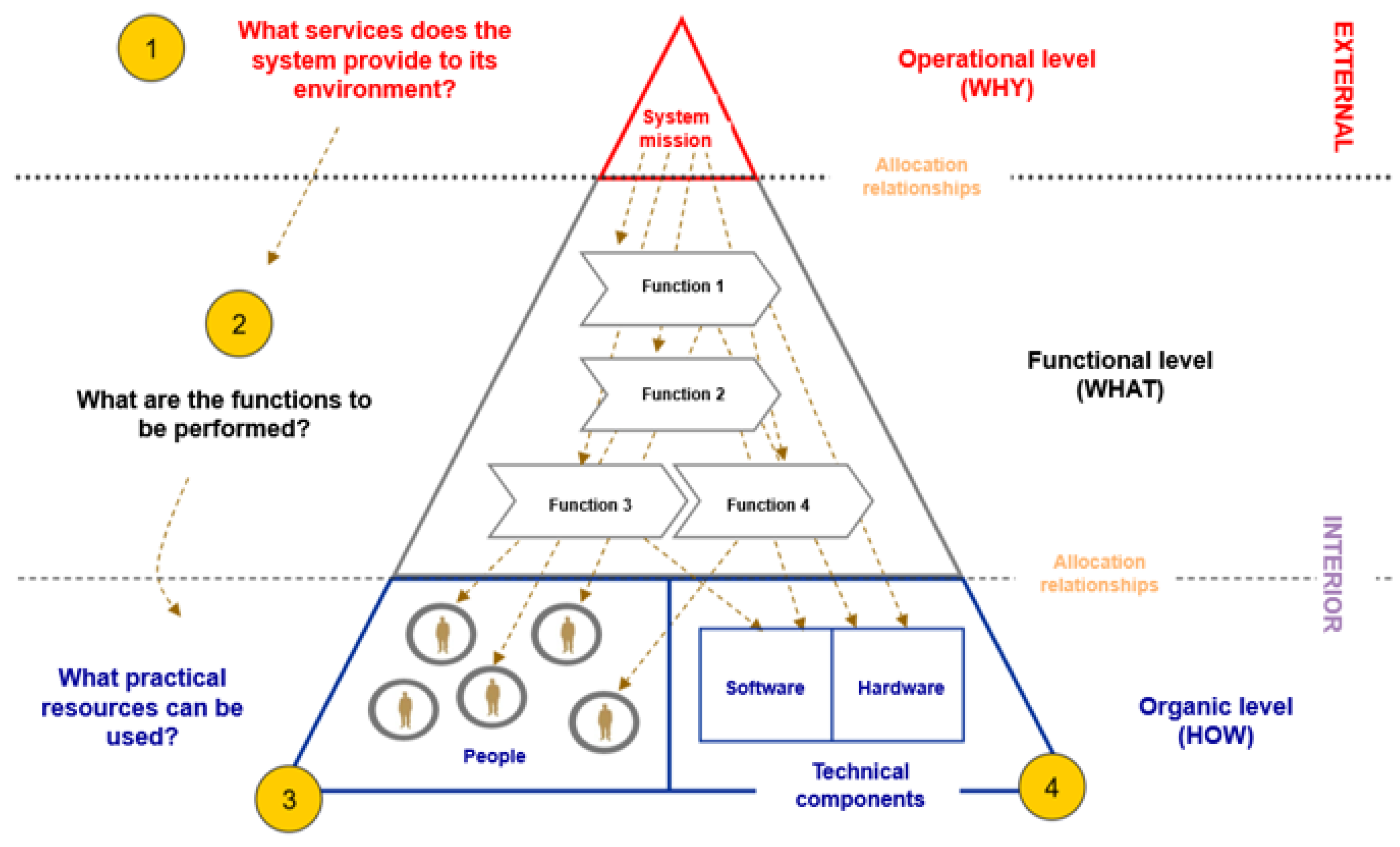

2.2.2. ITS Reference Architectures

- User Needs: the expectations that an ITS deployment and its associated services are required to meet.

- Functional Viewpoint: the set of functionalities that the ITS must provide to satisfy user needs, usually organized into functional areas and further detailed into specific functions.

- Physical Viewpoint: the organization of functions into physical components and their allocation to modules or subsystems.

- Communications Viewpoint: the communication links necessary to support the exchange of physical data flows.

2.2.3. Large Language Models and Retrieval-Augmented Generation

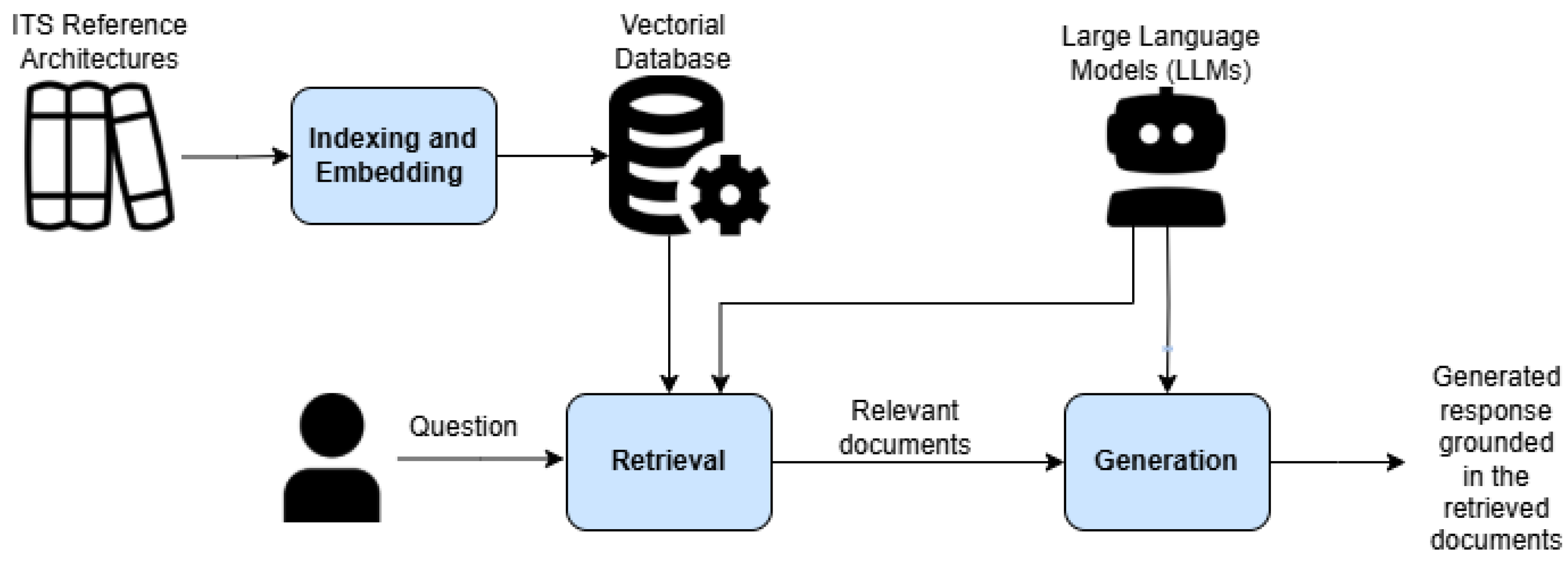

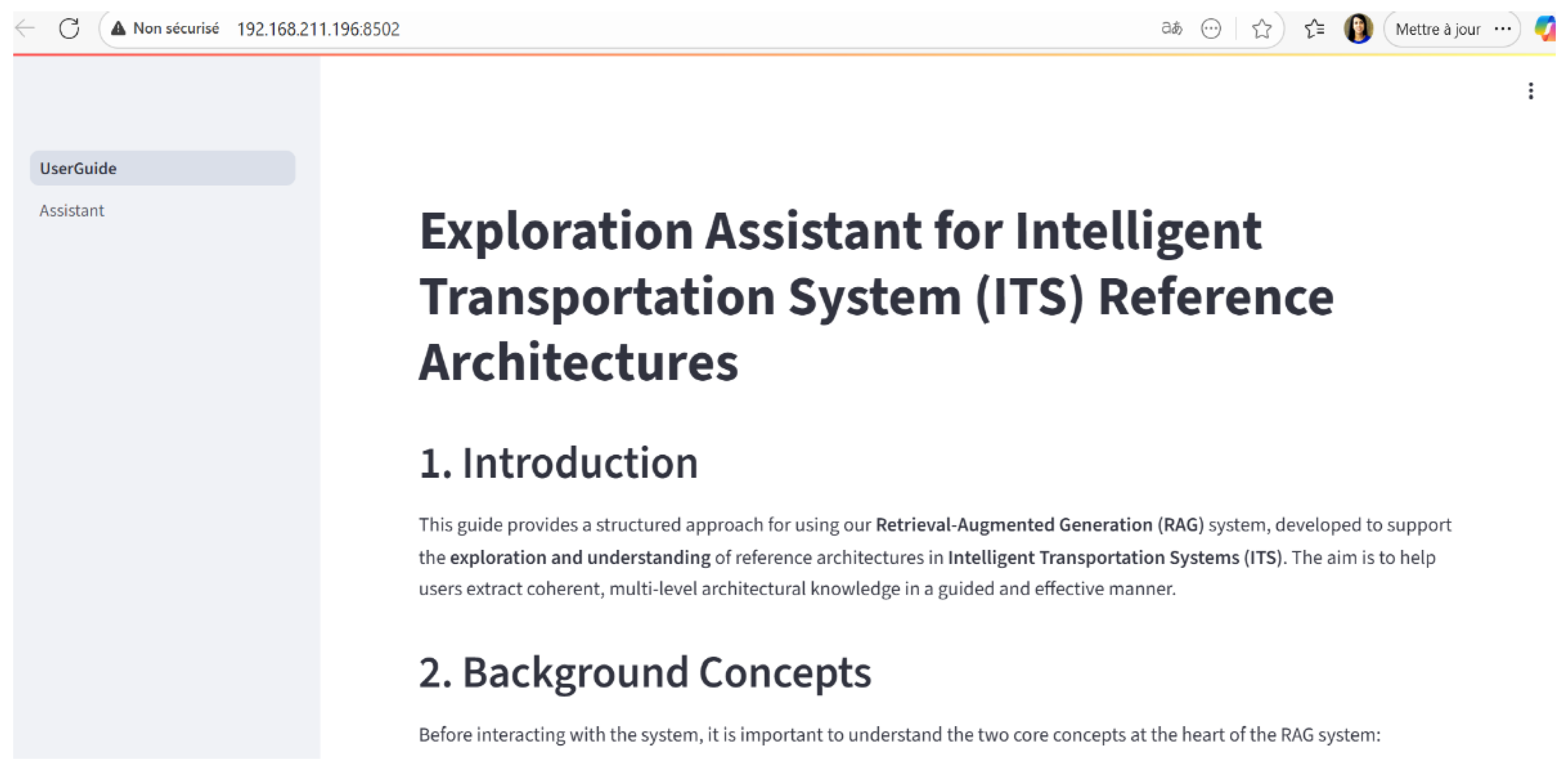

3. Retrieval-Augmented Generation System Pipeline

3.1. Indexing and Embedding

3.2. Retrieval

3.2.1. Retrieval – Similarity-Based Methods

3.2.2. Retrieval – Pre-Filtering Methods

3.3. Generation

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation of Retrieval Methods

4.1.1. Evaluation of Models for the Filter-Extraction Task

4.1.2. Retrieved Context Quality Evaluation

- METEOR [38]: originally developed for machine translation evaluation, this metric relies on unigram matching and incorporates stemming, synonymy, and paraphrasing.

- BERTScore [39]: designed for text generation evaluation, this metric computes token similarity using contextual embeddings rather than exact matches.

- BLEURT [40]: extends BERT by improving its correlation with human ratings through pre-training on synthetic data and fine-tuning on human evaluation datasets.

- LLM-as-a-Judge: an LLM is prompted to assess the quality of the retrieved context, given both the reference context and the user query. The evaluation considers two aspects: accuracy (whether all assertions are factually correct) and relevance (the closeness to the reference context). The model assigns a score from 1 (off-topic context) to 4 (high accuracy and relevance), accompanied by an explanation. These explanations are essential to verify the alignment between the model’s judgment and human ratings. We used Mistral-small 3.1:24B as the judging model.

- Vanilla: a similarity-based retrieval method relying on basic semantic search without query processing, applied to an index built from raw-extracted data of the reference architectures using a recursive chunking method (see Section 3.2.1).

- Structured Vanilla: a similarity-based retrieval method that applies the vanilla approach to the structured index (see Section 3.2.1).

- Extract-and-Associate (EA): a pre-filtering-based retrieval method (see Section 3.2.2).

- Extract-and-Align (EAL): a pre-filtering-based retrieval method (see Section 3.2.2).

- Adaptive: a pre-filtering-based retrieval method (see Section 3.2.2).

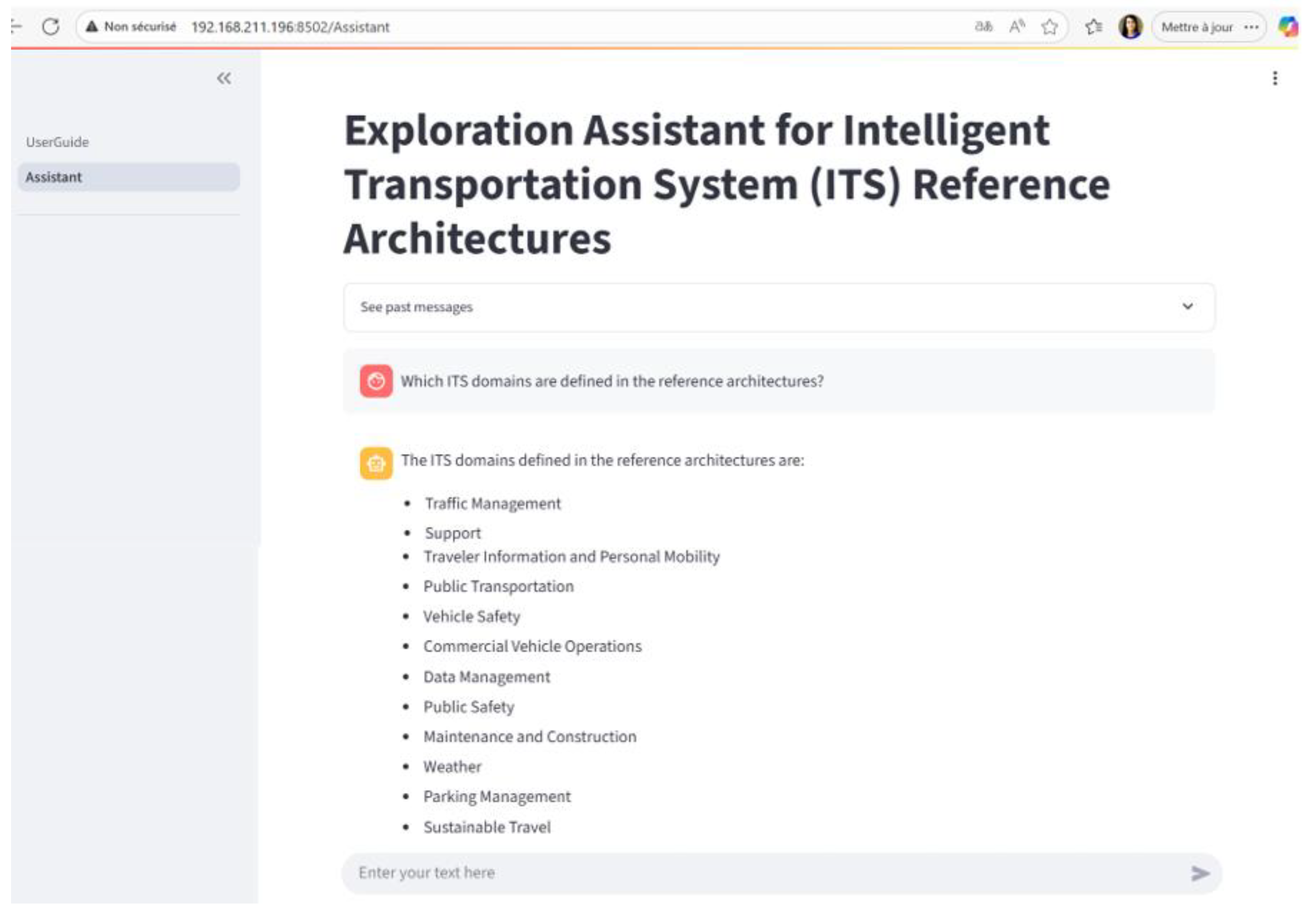

4.2. User-Oriented Evaluation of the System

- Identify ITS domains;

- Action: Ask the system for the list of ITS domains defined in the reference architectures;

- Expected output: A list of key domains (e.g., Traffic Management, Public Transport, etc.);

- 2.

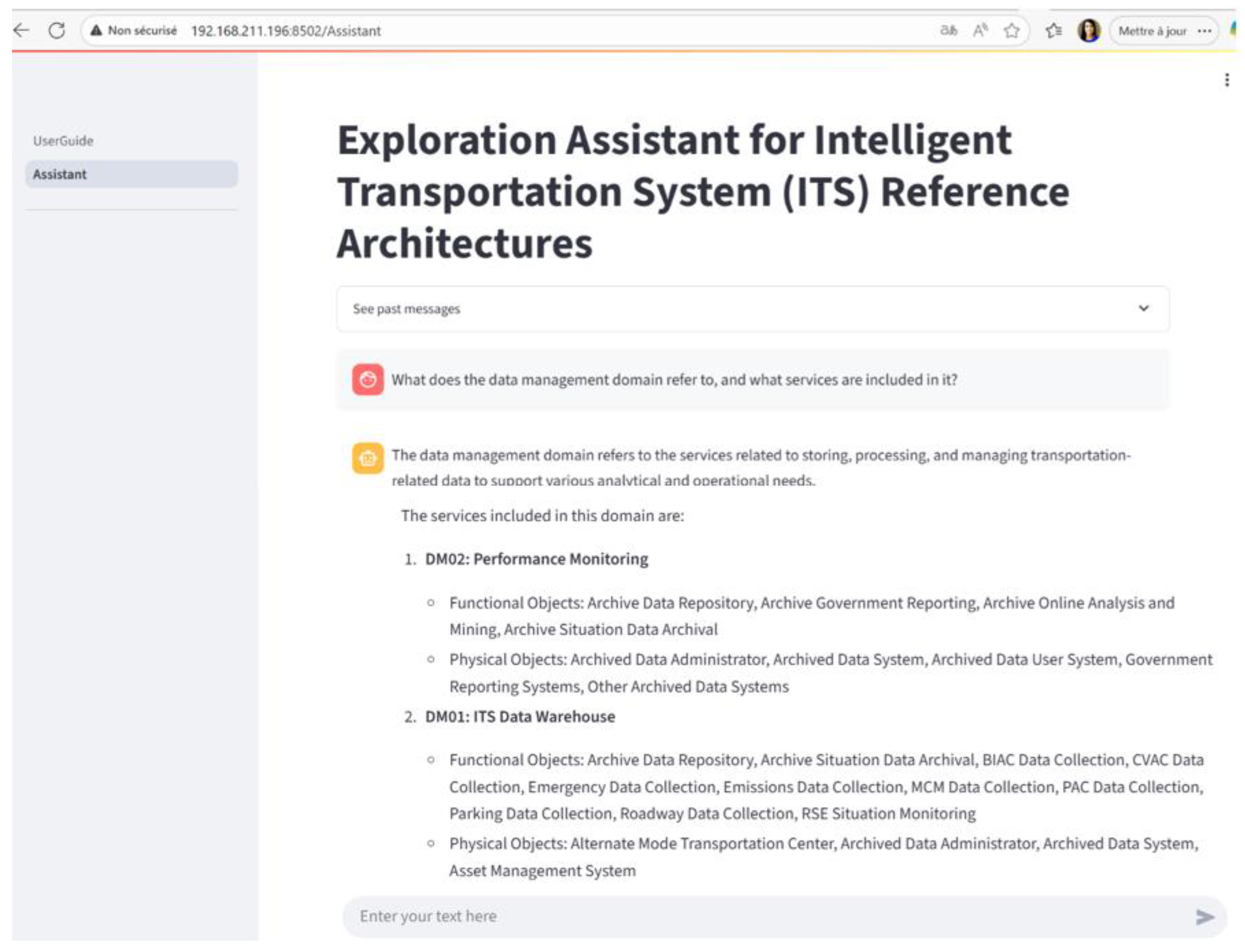

- Explore a selected domain;

- Action: Choose one domain and ask for detailed information;

- Expected output: A description of the domain and a list of ITS services it contains;

- 3.

- Investigate an ITS service;

- Action: Select a service relevant to your needs and ask for its functional overview;

- Expected Output: A brief explanation of the service’s objectives and its main architectural components;

- 4.

- Retrieve architectural objects;

- Action: Ask for the list of functional or physical objects associated with the selected service;

- Expected output: A structured list of relevant architectural elements (e.g., sensors, systems, users);

- 5.

- Deep dive into specific objects;

- Action: Request a description of a specific object;

- Expected Output: A detailed explanation of the object’s role, purpose, and characteristics;

- 6.

- Discover related objects;

- Action: Ask the system to identify objects related to a selected object;

- Expected output: A list of linked or interacting objects in the architecture;

- 7.

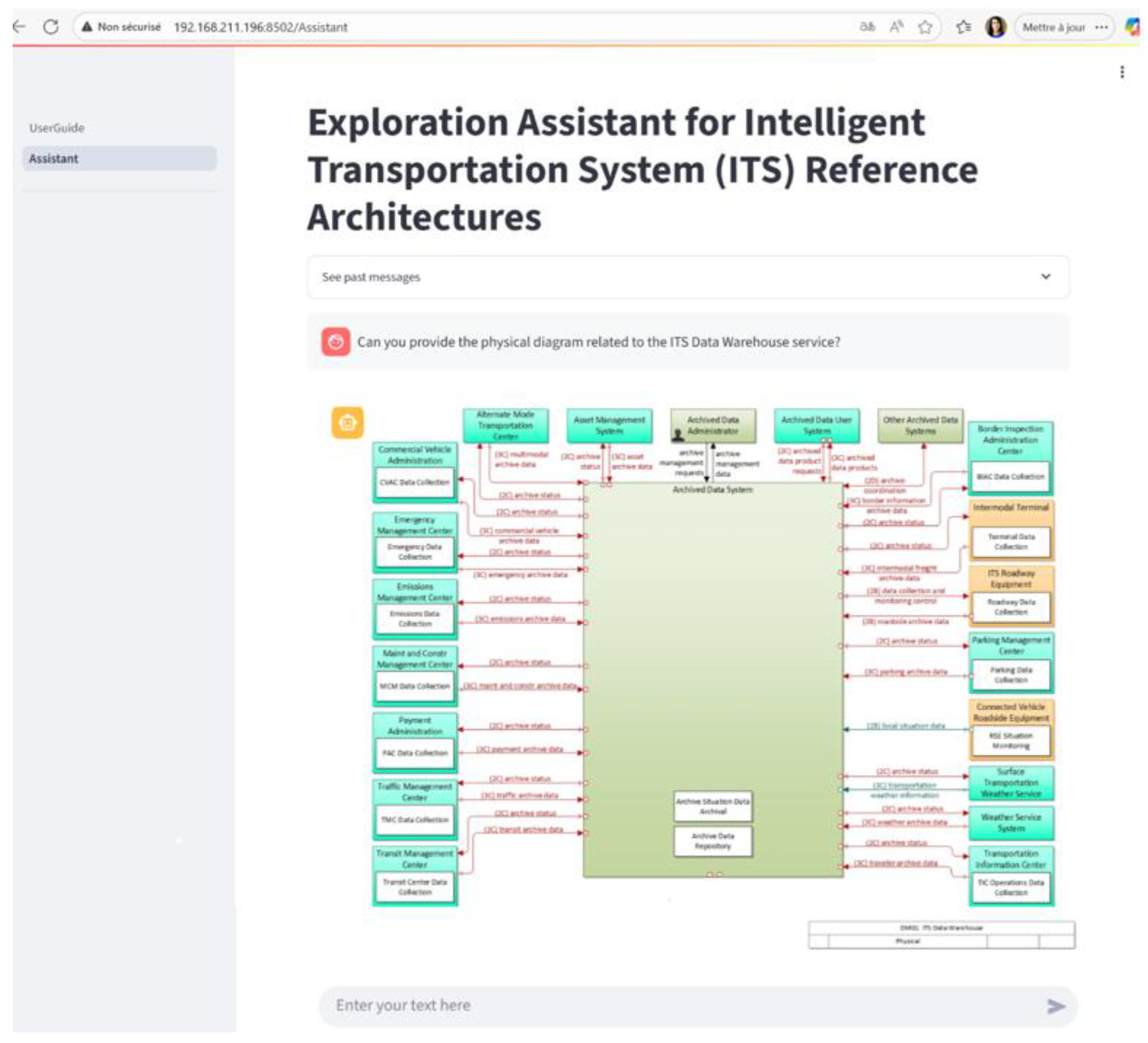

- Visualize the architecture;

- Action: Ask for the physical architecture diagram of the selected ITS service;

- Expected output: A visual representation showing the key objects and their interactions;

5. Discussion and Conclusions

References

- Tochygin, M. (2024, November). Integration of Intelligent Transportation Systems in the Context of Sustainable Development: Challenges and Opportunities for Smart Cities. In International Scientific Conference Intelligent Transport Systems: Ecology, Safety, Quality, Comfort (pp. 120-131). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Elassy, M., Al-Hattab, M., Takruri, M., & Badawi, S. (2024). Intelligent transportation systems for sustainable smart cities. Transportation Engineering, 100252.

- Qureshi, K. N., & Abdullah, A. H. (2013). A survey on intelligent transportation systems. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 15(5), 629-642.

- Greer, L., Fraser, J. L., Hicks, D., Mercer, M., & Thompson, K. (2018). Intelligent transportation systems benefits, costs, and lessons learned: 2018 update report (No. FHWA-JPO-18-641). United States. Dept. of Transportation. ITS Joint Program Office.

- Othman, K. M., Alzaben, N., Alruwais, N., Maray, M., Darem, A. A., & Mohamed, A. (2024). Smart Surveillance: Advanced Deep Learning based Vehicle Detection and Tracking Model on UAV Imagery. Fractals.

- ISO/IEC/IEEE 42020:2019:2019-07.: Software, systems and enterprise — Architecture processes. Int. Organ. Stand. Geneva, Switzerland (2019).

- Nakagawa, E. Y., Antonino, P. O., Becker, M.: Reference architecture and product line architecture: A subtle but critical difference. In: European Conference on Software Architecture. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 207-211 (2011).

- ARC-IT Version 9.3 (2025). Available at https://www.arc-it.net/.

- The FRAME Architecture. Available at https://frame-online.eu/frame-architecture/.

- ISO/IEC/IEEE 42010:2022: Software, Systems and Enterprise Architecture Description. ISO. https://www.iso.org/standard/74393.html.

- Zemmouchi-Ghomari, L. (2025). Artificial intelligence in intelligent transportation systems. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing and Special Equipment.

- Husak, A., Politis, M., Shah, V., Eshuis, H., & Grefen, P. W. P. J. (2015). Reference architecture for mobility-related services: a reference architecture based on GET service and SIMPLI-CITY project architectures.

- Molinete, B., Campos, S., Olabarrieta, I., Torre, A. I., Perallos, A., Hernandez-Jayo, U., & Onieva, E. (2015). Reference ITS architectures in Europe. Intelligent Transportation Systems: Technologies and Applications, 3-17.

- Ezgeta, D., Čaušević, S., & Mehanović, M. (2023, May). Challenges of physical and digital integration of transport infrastructure in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In International Conference “New Technologies, Development and Applications” (pp. 696-701). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Awadid, A. (2022, March). Reference Architectures for Cyber-Physical Systems: Towards a Standard-Based Comparative Framework. In Future of Information and Communication Conference (pp. 611-628). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Katz, D. M., Bommarito, M. J., Gao, S., & Arredondo, P. (2024). Gpt-4 passes the bar exam. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 382(2270), 20230254.

- Yadav, B. (2024). Generative AI in the Era of Transformers: Revolutionizing Natural Language Processing with LLMs. J. Image Process. Intell. Remote Sens, 4(2), 54-61.

- Rezk, N. M., Purnaprajna, M., Nordström, T., & Ul-Abdin, Z. (2020). Recurrent neural networks: An embedded computing perspective. IEEE Access, 8, 57967-57996.

- Mondal, H., Mondal, S., & Behera, J. K. (2025). Artificial intelligence in academic writing: Insights from journal publishers’ guidelines. Perspectives in Clinical Research, 16(1), 56-57.

- Xia, Y., Jazdi, N., & Weyrich, M. (2024, September). Enhance FMEA with Large Language Models for Assisted Risk Management in Technical Processes and Products. In 2024 IEEE 29th International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA) (pp. 1-4). IEEE.

- Awadid, A., Robert, B., & Langlois, B. (2024, February). Mbse to support engineering of trustworthy ai-based critical systems. In 12th International Conference on Model-Based Software and Systems Engineering.

- Lewis, P., Perez, E., Piktus, A., Petroni, F., Karpukhin, V., Goyal, N., ... & Kiela, D. (2020). Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive nlp tasks. Advances in neural information processing systems, 33, 9459-9474.

- Lei, L., Zhang, H., & Yang, S. X. (2023). ChatGPT in connected and autonomous vehicles: benefits and challenges. Intelligence & Robotics, 3(2), 144-147.

- Singh, G. (2023). Leveraging chatgpt for real-time decision-making in autonomous systems. Eduzone: International Peer Reviewed/Refereed Multidisciplinary Journal, 12(2), 101-106.

- Narimissa, E., & Raithel, D. (2024). Exploring Information Retrieval Landscapes: An Investigation of a Novel Evaluation Techniques and Comparative Document Splitting Methods. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.08479.

- Zhang, X., Zhang, Y., Long, D., Xie, W., Dai, Z., Tang, J., ... & Zhang, M. (2024). mgte: Generalized long-context text representation and reranking models for multilingual text retrieval. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.19669.

- Guo, Z., Xia, L., Yu, Y., Ao, T., & Huang, C. (2024). Lightrag: Simple and fast retrieval-augmented generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.05779.

- Chen, J., Lin, H., Han, X., & Sun, L. (2024, March). Benchmarking large language models in retrieval-augmented generation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (Vol. 38, No. 16, pp. 17754-17762).

- Yu, H., Gan, A., Zhang, K., Tong, S., Liu, Q., & Liu, Z. (2024, August). Evaluation of retrieval-augmented generation: A survey. In CCF Conference on Big Data (pp. 102-120). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Es, S., James, J., Anke, L. E., & Schockaert, S. (2024, March). Ragas: Automated evaluation of retrieval augmented generation. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations (pp. 150-158).

- Ru, D., Qiu, L., Hu, X., Zhang, T., Shi, P., Chang, S., ... & Zhang, Z. (2024). Ragchecker: A fine-grained framework for diagnosing retrieval-augmented generation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 37, 21999-22027.

- Team, G., Kamath, A., Ferret, J., Pathak, S., Vieillard, N., Merhej, R., ... & Iqbal, S. (2025). Gemma 3 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.19786.

- Dubey, A., Jauhri, A., Pandey, A., Kadian, A., Al-Dahle, A., Letman, A., ... & Ganapathy, R. (2024). The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv e-prints, arXiv-2407.

- https://mistral.ai/news/mistral-small-3.

- Abdin, M., Aneja, J., Behl, H., Bubeck, S., Eldan, R., Gunasekar, S., ... & Zhang, Y. (2024). Phi-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.08905.

- Yang, A., Yu, B., Li, C., Liu, D., Huang, F., Huang, H., ... & Zhang, Z. (2025). Qwen2. 5-1m technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.15383.

- Jin, R., Du, J., Huang, W., Liu, W., Luan, J., Wang, B., & Xiong, D. (2024, August). A comprehensive evaluation of quantization strategies for large language models. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics ACL 2024 (pp. 12186-12215).

- Banerjee, S., & Lavie, A. (2005, June). METEOR: An automatic metric for MT evaluation with improved correlation with human judgments. In Proceedings of the acl workshop on intrinsic and extrinsic evaluation measures for machine translation and/or summarization (pp. 65-72).

- Zhang, T., Kishore, V., Wu, F., Weinberger, K. Q., & Artzi, Y. (2019). Bertscore: Evaluating text generation with bert. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.09675.

- Sellam, T., Das, D., & Parikh, A. P. (2020). BLEURT: Learning robust metrics for text generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.04696.

| Model | Accuracy | Recall | Precision | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gemma3:1b | 0,33 | 0,18 | 0,29 | 0,22 |

| qwen3:1,7b | 0,75 | 0,62 | 0,76 | 0,68 |

| gemma3:4b | 0,57 | 0,47 | 0,59 | 0,52 |

| mistral:7b | 0,56 | 0,45 | 0,52 | 0,48 |

| llama3.1:8b | 0,57 | 0,43 | 0,55 | 0,48 |

| gemma3:12b | 0,71 | 0,71 | 0,64 | 0,67 |

| mistral-nemo:12b | 0,7 | 0,59 | 0,68 | 0,63 |

| phi4:14b | 0,73 | 0,74 | 0,67 | 0,7 |

| qwen2.5:14b | 0,68 | 0,64 | 0,66 | 0,65 |

| qwen3:14b | 0,81 | 0,8 | 0,78 | 0,79 |

| mistral-small3.1:24b | 0,84 | 0,86 | 0,8 | 0,83 |

| gemma2:27b | 0,74 | 0,76 | 0,68 | 0,72 |

| Method | Meteor | Bert f1 | Bleurt | Judge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vanilla | 0,23 | 0,27 | 0,4 | 0,45 |

| Structured Vanilla | 0,32 | 0,41 | 0,45 | 0,55 |

| EA | 0,12 | 0,15 | 0,15 | 0,33 |

| EAL | 0,29 | 0,31 | 0,38 | 0,48 |

| Adaptative | 0,31 | 0,41 | 0,45 | 0,59 |

| Method | Judge |

|---|---|

| Structured vanilla | 0,55 |

| Structured vanilla (summarized) | 0,69 |

| Adaptative | 0,59 |

| Adaptative (summarized) | 0,74 |

| Criterion | Definition | Score | Label | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Conciseness and synthesis |

Assesses whether the system presents the main points in a clear, synthesized form, rather than copying raw content. |

0 |

No synthesis |

The answer is a raw copy-paste or poorly structured content. |

|

1 |

Some synthesis |

Partial reformulation, but the answer is still redundant or lacks clarity. | ||

|

2 |

Well-synthesized |

The answer is clearly reformulated and structured in a concise, coherent way. | ||

|

Comprehensibility |

Evaluates whether the answer is understandable and adapted to non-expert users. | 0 | Hard to understand | The answer is too technical or unclear for non-specialists. |

| 1 | Moderately clear | Some parts are understandable; others require expert background. | ||

| 2 | Clear and accessible | The answer is easy to understand and well-adapted for non-expert users. | ||

|

Informative value |

Measures the extent to which the answer introduces new, relevant information that the user may not have known or expected. | 0 | No new content | The answer contains only familiar or obvious information. |

| 1 | Partially new | The answer includes some new or enriching information, but nothing substantial. | ||

| 2 | Highly informative | The answer brings clearly new, useful knowledge or insights for the user. |

| User | Criteria | Total score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conciseness & synthesis | Comprehensibility | Informative value | ||

| User 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| User 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| User 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| User 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| User 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| User 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| User 7 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| User 8 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| User 9 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| User 10 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).