Submitted:

22 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

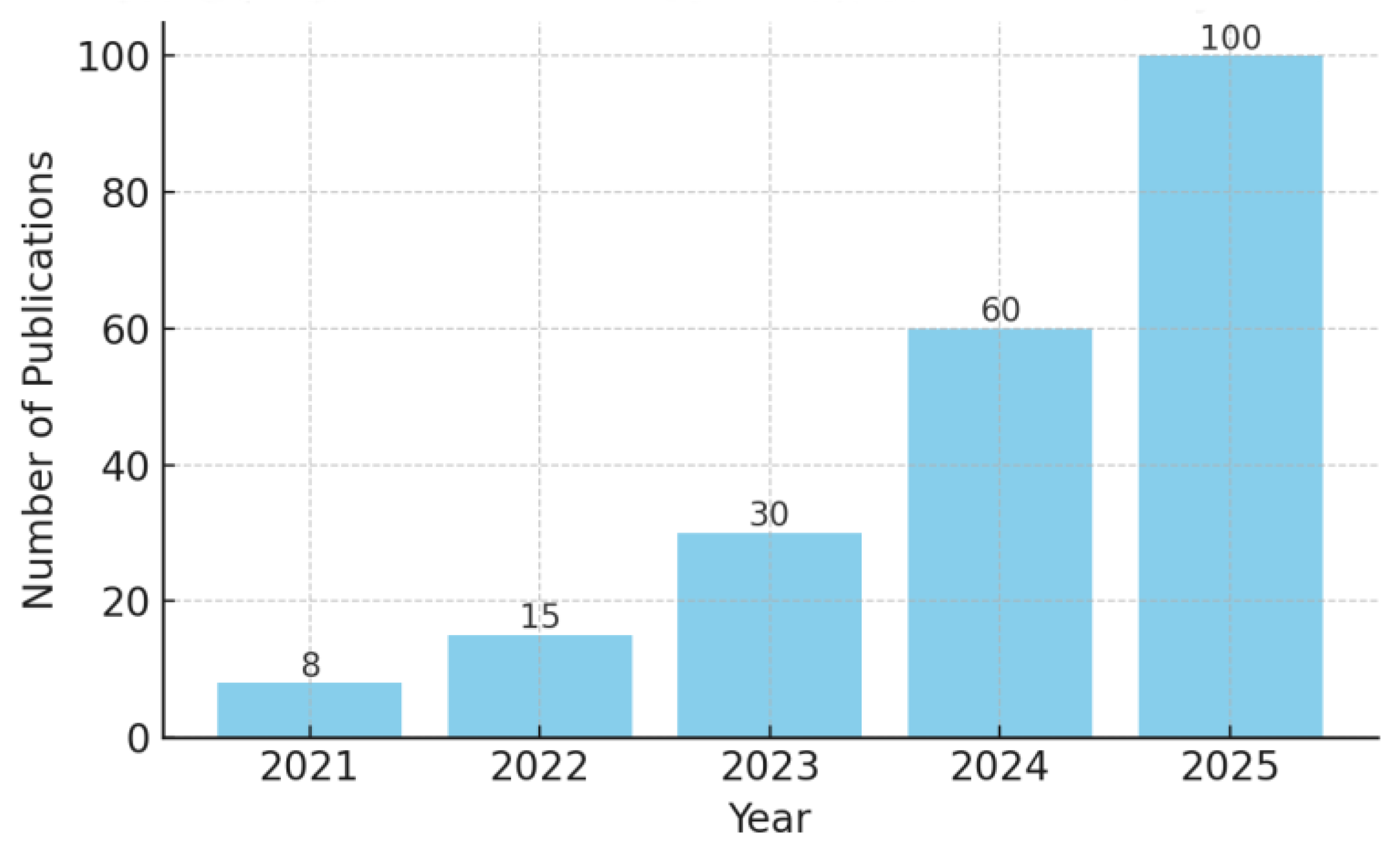

2. Background: Digital Transformation and AI in the Water Sector

- Prediction and Forecasting: Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), Support Vector Machines (SVMs), and Random Forests have been widely used for tasks like water demand forecasting, water quality prediction and stream flow forecasting.

- Classification and Anomaly Detection: These models are also used for classification tasks, such as identifying pipes at high risk of failure or detecting anomalies in sensor data that could indicate a leak or contamination event.

- Asset Management: In asset management, AI has been used for automated condition assessment. For example, computer vision combined with ML methods like Random Forest has been successfully applied to analyse CCTV footage of sewer pipes, automatically detecting faults like cracks and displaced joints with high accuracy [15].

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are adept at capturing spatial patterns, making them ideal for analysing geospatial data like satellite imagery for land use classification or remote sensing of water bodies.

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and particularly their advanced variant Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), are designed to handle sequential data, making them state-of-the-art for time-series forecasting of hydrological variables like rainfall, stream flow and water demand.

- Hybrid Models: researchers are increasingly creating hybrid models that combine the strengths of different architectures. A CNN-LSTM model, for instance, can use CNN layers to extract spatial features from weather maps and LSTM layers to model the temporal evolution of a flood event.

- A powerful application of GenAI is in creating high-fidelity synthetic data to augment limited real-world datasets, which is crucial for training robust AI models. For example, a generative AI approach was developed for spatiotemporal imputation and demand prediction in water distribution systems, exploiting sensor data to reconstruct missing data and improve forecasting accuracy. [21] Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) have been used to generate realistic time-series data for water demand, synthetic acoustic signals for leak detection, and patterns of water quality parameters to train anomaly detection systems. A recent study explored using LLMs to generate synthetic hydrological data (e.g., daily rainfall and reservoir levels) by providing prompts engineered with key statistical properties from a real dataset. Models trained on the augmented dataset showed improved forecasting accuracy [22]. Generative models like VAEs, GANs and diffusion models can be trained on digital twin data for data augmentations, hence generating high-fidelity synthetic water consumption samples already labeled to train supervised learning models and can simulate different scenarios such as changes in water demand, infrastructure failures, or weather conditions [23].

- A multi-agent LLM framework has been presented to automate water-distribution optimisation [24]. An Orchestrating Agent coordinates knowledge, modelling (EPANET), and coding agents for hydraulic model calibration and pump-operation optimisation. Tested on Net2 and Anytown, the Coding agent performed most accurately across both benchmarks; natural-language reasoning lacked numerical precision, while tool integration improved reliability.

- Projects like WaterER and DRACO are creating standardised benchmarks to rigorously evaluate the performance of different LLMs (e.g., GPT-4, Gemini, Llama) on domain-specific tasks. The Drinking water and wAstewater COgnitive assistant (DRACO) initiative [25] released a dataset for benchmarking open- and closed-source models and found that state-of-the-art open-weight models can match, and sometimes outperform, proprietary systems, which is promising for utilities seeking secure, on-premise deployments.

- Researchers can use LLMs to perform AI driven literature mapping. For example, using an LLM and geocoding on 310,000 hydrology papers (1980–2023), a study mapped basin trends, collaborations, and hotspots [26]. Research has surged since the 1990s, shifting from groundwater/nutrients toward climate change and ecohydrology. Activity concentrates in North America and Europe, with rising China/South Asia attention but persistent gaps in extreme-rainfall regions.

- HydroSuite-AI, an LLM-enhanced web application that generates code snippets and answers questions related to open-source hydrological libraries, lowering the entry barriers for researchers and practitioners in the field without extensive programming expertise [9].

- A vast repository of knowledge in the water sector remains locked in non-machine-readable legacy documents like handwritten maintenance logs, scanned reports, and old maps. Traditional Optical Character Recognition (OCR) engines like Tesseract struggle with so called "dark data," especially with complex layouts and handwriting. A case study on Danish water utility documents demonstrated that a Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM), Qwen-VL, dramatically outperformed Tesseract [18]. The MLLM reduced the Word Error Rate by nearly nine fold, accurately transcribing handwritten notes and correctly interpreting complex forms in a zero-shot setting.

3. Drinking Water Quality AI Analytics

3.1. Overview

3.2. Traditional Machine Learning and Deep Learning in Water Quality

- Water Quality Parameter Prediction. Early neural networks were applied to water quality modeling [31,32]. More recently, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks have demonstrated success in predicting specific water quality parameters, such as dissolved oxygen (DO) levels, effectively capturing peaks and troughs, even during periods of low stream flow and data fluctuations [33]. Hybrid models, like the SOD-VGG-LSTM, have achieved high accuracy in short-term water quality prediction, particularly in capturing extreme values. An LSTM-based encoder-decoder model has also been shown to predict water quality variables with satisfactory accuracy after data denoising [34]. Further advancements include hybrid encoder-decoder BiLSTM models with attention mechanisms, which outperform state-of-the-art algorithms by efficiently handling noise, capturing long-term correlations, and performing dimensionality reduction [35]. Other techniques such as Ensemble decision tree ML algorithms have been applied, including for predicting low chlorine events [36].

- Potability Prediction. DL models, including Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLP), LSTM, and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), have been comparatively analysed for water potability classification in rural areas, with CNNs achieving higher accuracy than other ML models like Random Forest, Decision Jungle, Naive Bayes, Logistic Regression and SVM. These predictions often rely on parameters such as pH, total dissolved solids, chloramines, sulfate and turbidity, with data often sourced from public datasets like Kaggle [22].

- Contamination Event Detection. ML and DL models are widely used for water quality anomaly detection, addressing point, contextual, and collective anomalies [30,37,38]. A hybrid framework combining deep learning and extreme machine learning has been proposed for detecting anomalies in high-dimensional water quality data [39]. Most data-driven methods suffer drawbacks associated with high computational cost, imbalanced anomalous-to-normal data ratio resulting in high false positive rates and poor handling of missing data [22]. LSTM models have been specifically designed for monitoring water distribution systems, detecting anomalies based on changes over time in water indicators [40].

- Remote Sensing and Vision-based AI. Remote sensing data enables ML to serve as an efficient alternative to traditional manual laboratory analysis, offering real-time detection feedback crucial for rapid contamination detection [21]. Computer vision techniques are also being employed for tasks such as algal bloom monitoring. Efforts are directed towards using advanced image description mechanisms to detect and analyse water pollution sources, facilitating prompt intervention and mitigation measures [41].

- Data mining for data visualisation and knowledge discovery for water quality. Self-organising maps (SOM), a form of unsupervised artificial neural network (ANNs) [42], have been demonstrated in water distribution system data mining for microbiological and physico-chemical data at laboratory scale [43]; in clustering of water quality, hydraulic modelling and asset data for a single water supply zone [44]; for multiple DMAs [45]; in interpreting the risk of iron failures [46]; in relating water quality and age in drinking water [47] and in exploring the rate of discolouration material accumulation in drinking water [48]. Other approaches to data-driven visualisation/mapping and cluster analysis include using k-means (typically with Euclidean distance), hierarchical clustering, distribution models (such as the expectation-maximisation algorithm), fuzzy clustering and density-based models, e.g. DBSCAN [49] and Sammon’s projection [50]. Work has also developed techniques to explore correlations (using semblance analysis) between water quality and hydraulic data streams in order to assess asset deterioration and performance [28].

- Model calibration and tuning. A combined accumulation–mobilisation model for distribution-system discolouration was calibrated and validated using particle swarm optimisation [51]. The formulation tracks pipe-wall deposit build-up and erosion with two empirical parameters, reproducing turbidity responses from field trials. Results enable risk-based planning of flushing and maintenance, forecasting discolouration propensity across assets and operating regimes.

3.3. Generative AI for Enhanced Water Quality Modelling

- Synthetic Data Generation to address scarcity. One of the significant limitations of traditional ML/DL models in water quality is the difficulty in obtaining large amounts of high-fidelity, domain-specific data, especially for rare events like contamination. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are proving useful for creating synthetic data that mimics real measurements, thereby augmenting sparse datasets and improving model robustness [34].

- Contamination detection. A case study involved a novel GAN architecture that generated expected normal water quality patterns across multiple monitoring sites in China’s Yantian network. By comparing real measurements against these GAN-generated baseline patterns, the system effectively detected contamination events, demonstrating the model's capability to capture complex spatiotemporal relationships with high detection performance and low false alarm rates [52].

- Multimodal Monitoring and Visualization. MLLMs (e.g., GPT-4 Vision, Gemini, LLaVA, QWEN-VL) are being evaluated for hydrological applications such as water pollution management, demonstrating exceptional proficiency in interpreting visual data for water quality assessments. These models can integrate visual and textual data for real-time monitoring and analysis, enabling dynamic, real-time visualisations of complex water quality scenarios, including potential contaminant spread patterns [35].

- AI-Assisted Information Retrieval. LLMs are being integrated into platforms to enable conversational queries about operational data. For instance, Klir’s "Boots" chatbot, powered by ChatGPT, can summarize lab results, flag anomalies in water quality readings, and assist with report generation to regulators by drawing on the utility’s secure internal database [54].

- AI Assistants for professionals. LLMs can serve as ‘water expert models’ to assist professionals by answering questions, summarising compliance documents (enhanced decision support), and generating reports or code [55,56]. The WaterER benchmark suite has evaluated LLMs (e.g., GPT-4, Gemini, Llama3) for their ability to perform water engineering and research tasks, demonstrating their proficiency in generating precise research gaps for papers on ‘contaminants and related water quality monitoring and assessment’ and creating appropriate titles for drinking water treatment research. It is expected that the field of hydrology can benefit from LLMs, by addressing various challenges within physical processes [57]. WaterGPT is a domain-adapted large language model for hydrology [58]. The authors curated hydrology corpora, perform incremental pretraining and supervised fine-tuning, and enable multimodal inputs. WaterGPT supports knowledge-based Q&A, hydrological analysis, and decision support across water resources tasks, showing improved performance versus general LLMs on domain benchmarks and case studies reported. Another perspective on customising general LLMs into domain-adapted “WaterGPTs” for water and wastewater management appears in [59]. The authors outline methods—prompt engineering, knowledge and tool augmentation, and fine-tuning—discuss dataset curation and ethics, and propose benchmarking tasks and evaluation suites. A roadmap highlights reliability, safety, and practical use cases across stakeholders.

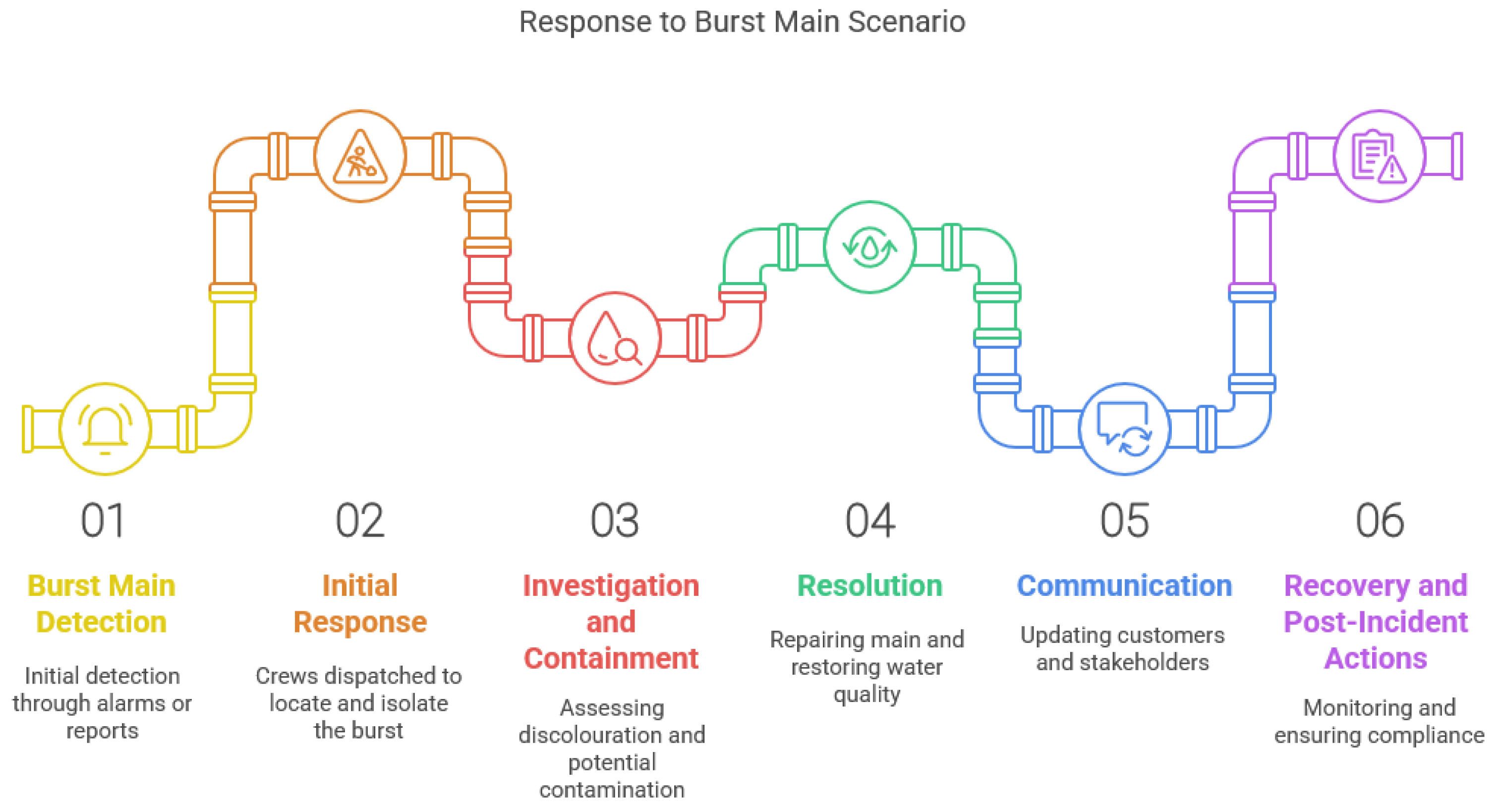

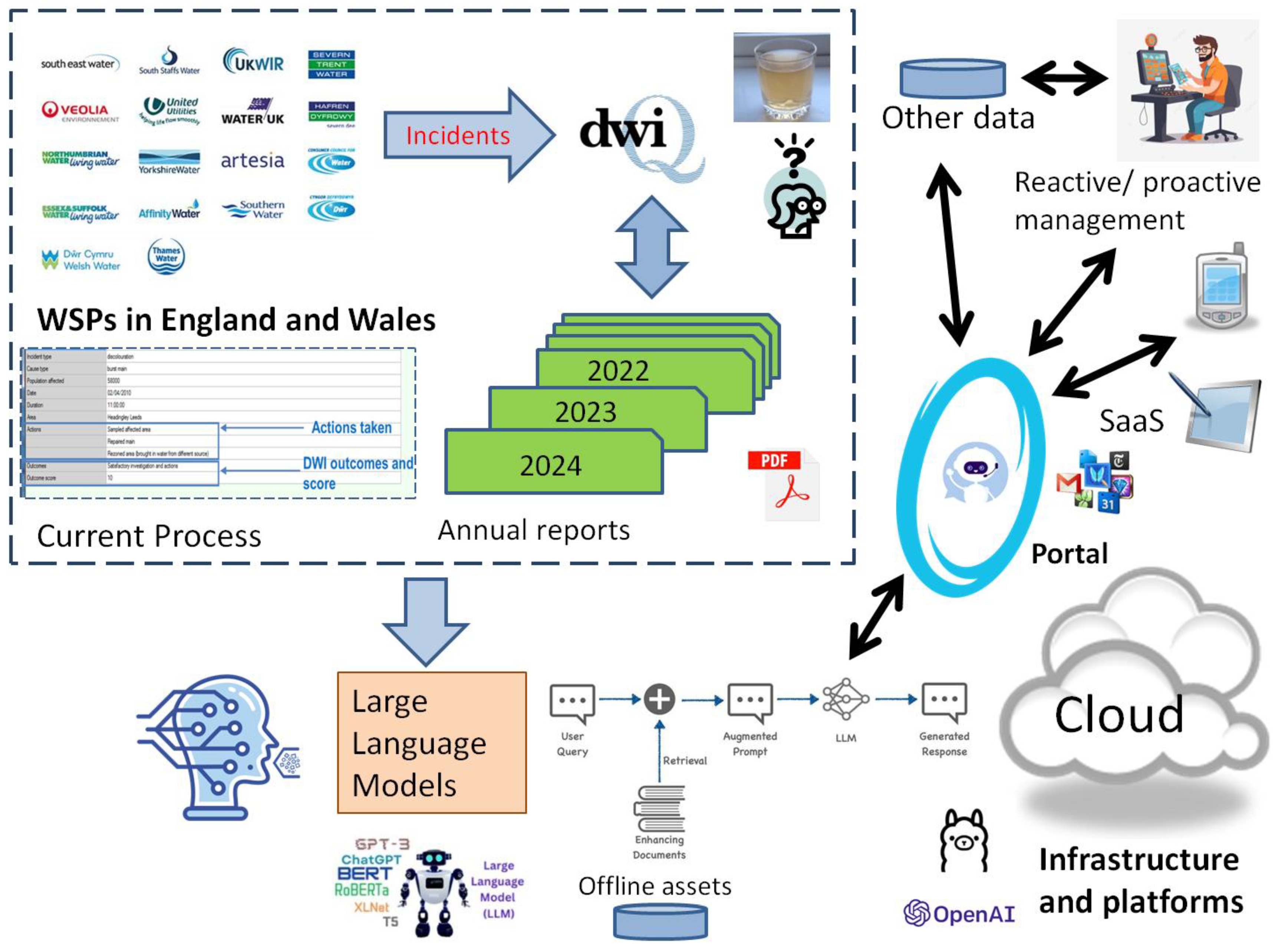

4. Case Study: Drinking Water Quality Event Management

4.1. Introduction

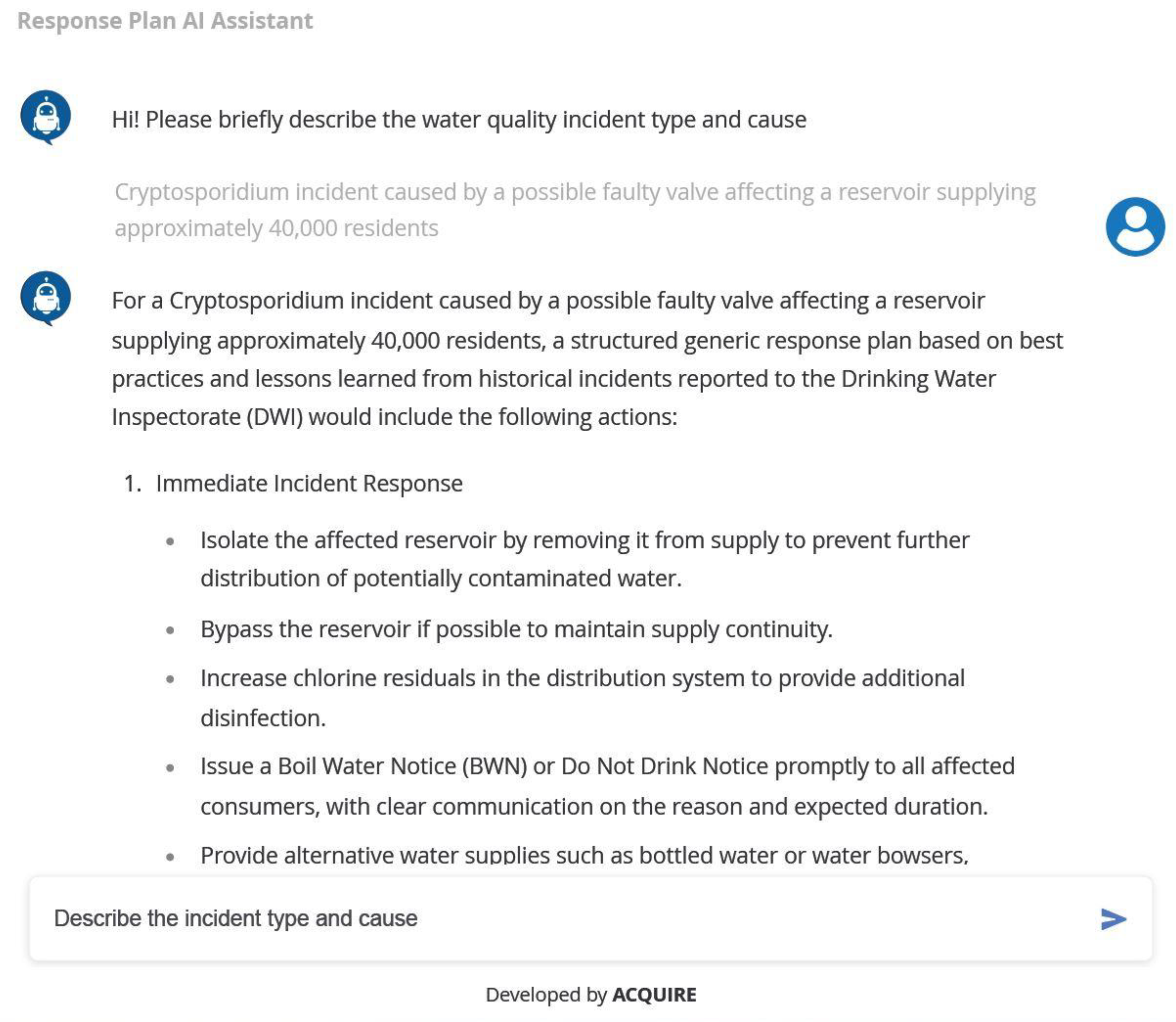

4.2. ACQUIRE Project

4.3. RAG for Generic Response Plan

5. Discussion and Future Work

5.1. Overview

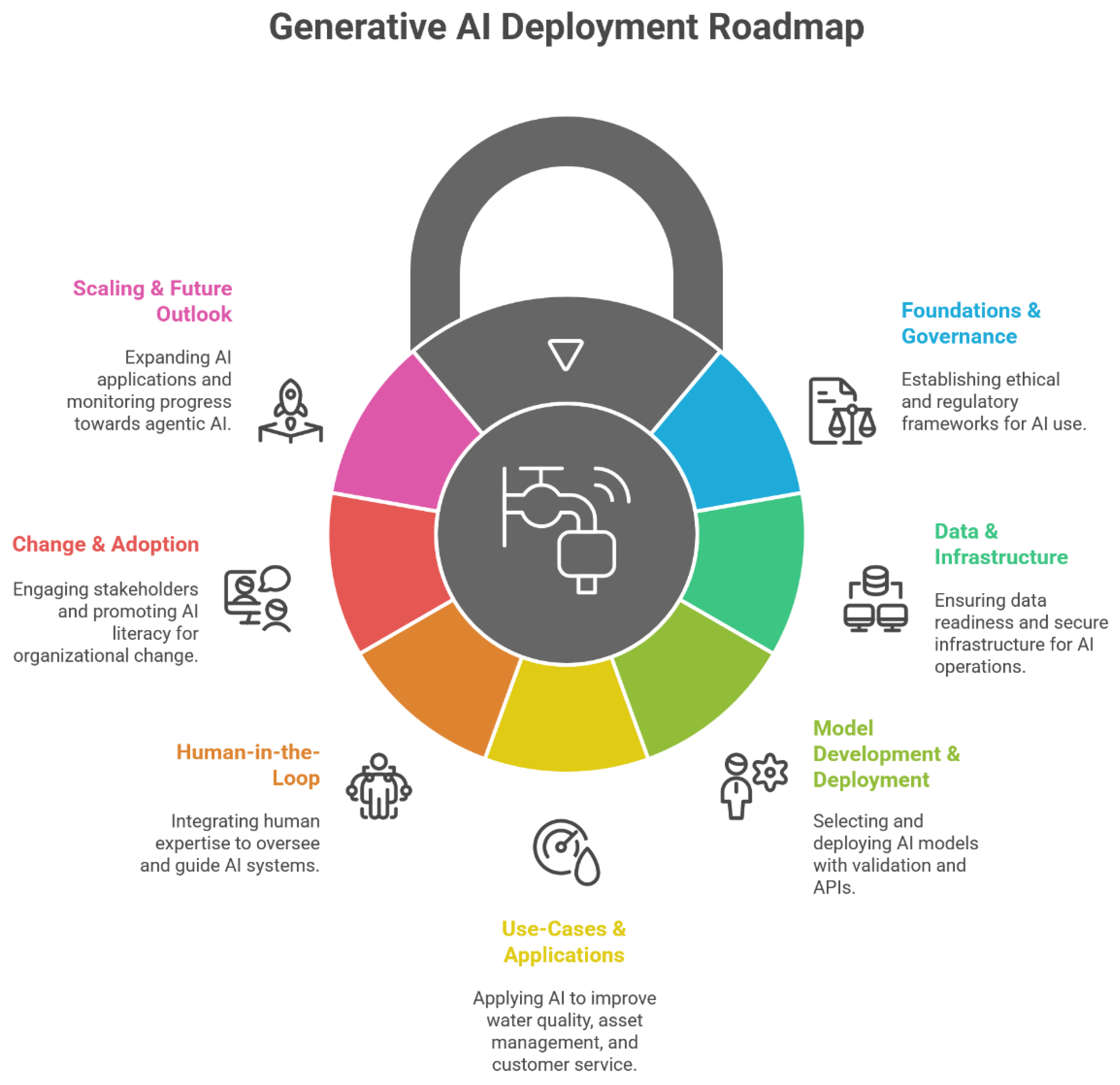

5.2. Roadmap

- Key areas:

- Foundations and governance. Foundations and governance provide the strategic bedrock for GenAI deployment in the water sector. Establishing a clear business case is essential, ensuring that investment delivers measurable benefits in efficiency, resilience, or customer service. Alignment with regulators safeguards compliance, while ethical frameworks address bias, fairness, and transparency. Building trust in AI requires proactive communication and embedding responsible AI practices from the outset. Crucially, success rests on positioning AI as a partner to human expertise, enabling collaboration rather than substitution.

- Data and infrastructure. Data readiness entails ensuring quality, availability, and interoperability across diverse sources such as SCADA, GIS, and asset management systems. Establishing targeted governance frameworks—focused on specific use cases—supports compliance without stifling innovation. Cloud, edge, or hybrid architectures must be evaluated for scalability, latency, and resilience, with cybersecurity protections built into every layer. With so much data available, it can be overwhelming to identify the most valuable insights for decisions. If data is machine readable in knowledge repositories then humans can be AI assisted to be more productive and effective. By addressing data fragmentation and prioritising metadata and standards, utilities can build robust pipelines that allow AI to process, contextualise, and integrate operational data into actionable intelligence.

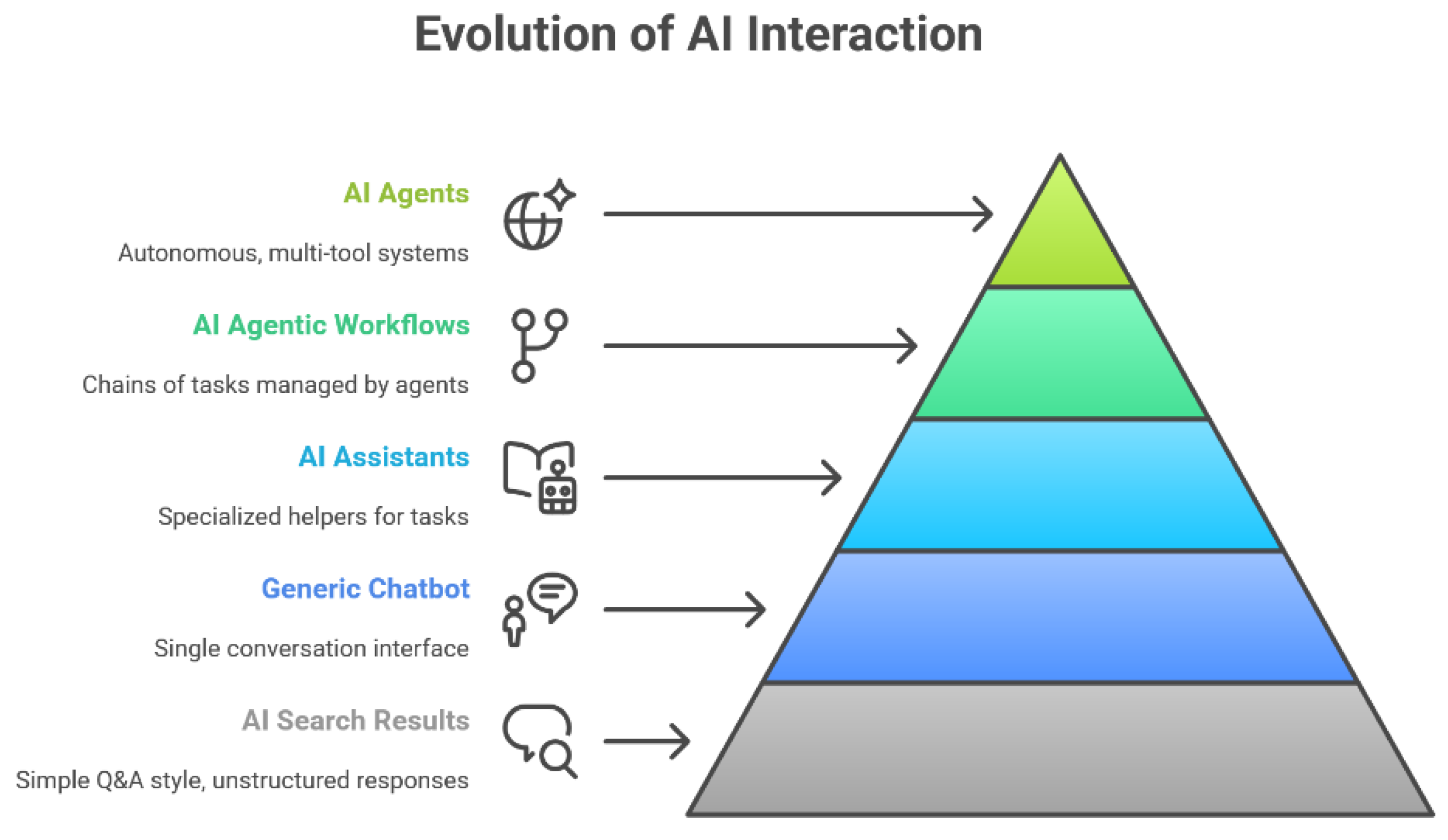

- Model development and deployment. Generative AI is emerging as a ‘game changer’ by democratising access to complex AI tools through natural language interactions, enabling intuitive communication with complex systems and reducing the steep learning curve associated with traditional software and advanced analytics [19]. Model development involves the systematic selection, adaptation and validation of generative AI tools for water applications. Choosing between commercial and open-source large language models requires balancing transparency, licensing and support. Fine-tuning models with sector-specific documentation enhances contextual accuracy. RAG offers an effective mechanism to reduce hallucinations and ground outputs in verified sources. Rigorous benchmarking and validation ensure robustness and reliability, while modular deployment strategies—whether on-premises, cloud-based, or via APIs—facilitate integration into operational workflows and maintain flexibility as foundation models evolve.

- Use-cases and applications. The true value of GenAI lies in its application to priority use cases that deliver tangible benefits. When considering GenAI, keep an open mind – it is not all about chat functions. For example, incorporating AI into reporting/ dashboard tools, or exploring how automation and Agentic AI could be used to enhance business processes and decision-making. In water quality monitoring, AI can synthesise laboratory data, regulatory limits and historical trends to flag emerging risks. Asset management and predictive maintenance are strengthened by analysing sensor data to anticipate failures and optimise investment. Customer service can be enhanced through AI-enabled chatbots that provide clear responses to queries. Furthermore, regulatory compliance activities benefit from automated report generation, structured audit trails and streamlined document retrieval, collectively driving efficiency, transparency, and resilience.

- Human-in-the-Loop. HITL/HOTL approaches ensure that AI deployment remains guided by expert judgment and domain-specific oversight. Rather than replacing operators, GenAI functions as a co-pilot, augmenting their capacity to interpret complex datasets and make informed decisions. Structured frameworks for human oversight safeguard against errors and reinforce accountability. Developing hybrid expertise—engineers proficient in both water systems and AI— will enable organisations to critically assess outputs. Fusion skills, particularly judgement integration, support the evaluation of AI suggestions for trustworthiness, and relevance, ensuring that GenAI systems complement, rather than supplant, human analytical and ethical capabilities. This collaborative intelligence, where human ingenuity combines with AI systems, consistently outperforms either humans or machines working alone and helps address and mitigate job fears as human engineering experience is still essential.

- Change and adoption. Successful GenAI integration demands comprehensive change and adoption strategies. Users need to be involved in the process as the process: it should be about what people need from AI, not the technology itself. Integration and change management are key to ensuring any new AI solution is properly adopted and embedded in processes. Stakeholder engagement—spanning regulators, operators, and customers—fosters legitimacy and confidence. Upskilling programmes in AI literacy will equip staff to use tools effectively, reducing resistance and building organisational trust. Building systems that excel at preserving institutional knowledge by processing historical records and creating accessible repositories of operational expertise is particularly valuable during workforce transitions. Change management must also address cultural concerns, including fears of redundancy or technological disruption, by framing AI as an enabler of higher-order and more productive work. Incremental adoption through pilots builds confidence and delivers demonstrable value, while embedding AI into business processes requires strong leadership to champion innovation and sustain momentum across the organisation.

- Scaling and future outlook. Scaling GenAI from pilots to sector-wide adoption requires careful planning and sustained monitoring. Early projects should focus on quick wins, delivering measurable improvements that secure organisational confidence. Continuous retraining and adaptation are necessary to maintain accuracy, particularly as new foundation models and regulatory requirements emerge. Over time, adoption can progress from reactive generative tools towards agentic AI systems capable of autonomous goal-setting and adaptive strategy.

5.3. Challenges and Future Developments

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mounce, S. R. (2020). Data Science Trends and Opportunities for Smart Water Utilities. In D. Han, S. Mounce, A. Scozzari, F. Soldovieri, & D. Solomatine (Eds.), ICT for Smart Water Systems: Measurements and Data Science. Handbook of Environmental Chemistry. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Bettin, A. (2023). Digital transformation for the water industry: how a data-driven business intelligence platform can improve operations. Water Practice & Technology, 18(7), 1599-1607. [CrossRef]

- Zolghadr-Asli, B., Ferdowsi, A.and Savić, D. (2024). A call for a fundamental shift from model-centric to data-centric approaches in hydroinformatics. Cambridge Prisms: Water, 2, e7, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y., & Hinton, G. (2015). Deep learning. Nature, 521(7553), 436–444. [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, R., Yussif, A.-M., & Zayed, T. (2025). Making waves: Generative artificial intelligence in water distribution networks: Opportunities and challenges. Water Research X, 28, 100316. [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I. J., Pouget-Abadie, J., Mirza, M., Xu, B., Warde-Farley, D., Ozair, S., Courville, A., & Bengio, Y. (2014). Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1406.2661. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, Ł., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 30, 5998–6008.

- Wala, J., & Rüppel, U. (2025). Leveraging Large Language Models for Synthetic Data Generation for AI Applications for Water Infrastructure Management. Paper presented at EG-ICE 2025. [CrossRef]

- Pursnani, V., Ramirez, C. E., Sermet, Y., & Demir, I. (2024). HydroSuite-AI: Facilitating Hydrological Research with LLM-Driven Code Assistance. EarthArXiv preprint.

- World Economic Forum & Capgemini. (2024). Navigating the AI Frontier: A Primer on the Evolution and Impact of AI Agents.

- Agentic Platforms and APIs: Global Market Outlook. (2025).

- International Data Corporation (IDC). (2024). The global impact of artificial intelligence on the economy and jobs. IDC. https://my.idc.com/getdoc.jsp?containerId=prUS52600524. Accessed: September 2025.

- World Economic Forum. (2023). Digital transition framework. World Economic Forum. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Digital_Transition_Framework_2023.pdf. Accessed: September 2025.

- Mounce, S. R., Shepherd, W., Boxall, J. B., Horoshenkov, K. & Boyle, J. (2021). Autonomous robotics for water and sewer networks. Hydrolink, IAHR. No. 2/2021, pp.55-62.

- Li, Y., Wang, H., & Dang, L. M. (2022). Vision-Based Defect Inspection and Condition Assessment for Sewer Pipes: A Comprehensive Survey. Sensors, 22(7), 2722. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. T. and Mishra, K. (2024). Deep learning in hydrology and water resources disciplines: concepts, methods, applications, and research directions. Journal of Hydrology, 628, 130458. [CrossRef]

- Fu, G., Jin, Y., Sun, S., Yuan, Z., & Butler, D. (2022). The role of deep learning in urban water management: A critical review. Water Research, 223, 118973. [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum & Accenture. (2025). AI in Action: Beyond Experimentation to Transform Industry.

- Ramachandran, A., Neergaard, T. F. B., Maier, A., & Bayer, S. (2025). Digitization Framework of Water Utility Documents for Digital Twins. Paper presented at CCWI 2025 - 21st Computing & Control for the Water Industry Conference.

- Sela, L., Housh, M., & Vairavamoorthy, K. (2025). Making waves: The potential of generative AI in water utility operations. Water Research, 272, 122935. [CrossRef]

- Velayudhan, N. K., Devidas, A. R. & Savić, D. A. (2025). Generative AI for spatio-temporal multivariate imputation and demand prediction in water distribution systems. Results in Engineering, 27, 106178. [CrossRef]

- Wala, J. & Rüppel, U. (2025). Leveraging large language models for synthetic data generation for AI applications for water infrastructure management. In A. Moreno-Rangel & B. Kumar (Eds.), EG-ICE 2025: AI-Driven Collaboration for Sustainable and Resilient Built Environments: Proceedings of the 32nd International Workshop on Intelligent Computing in Engineering (ISBN 978-1-914241-82-6). University of Strathclyde Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Taloma, R. J. L., Cuomo, F., Comminiello, D., & Pisani, P. (2025). Machine learning for smart water distribution systems: Exploring applications, challenges and future perspectives. Artificial Intelligence Review, 58, 120. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Fu, G., & Savić, D. A. (2025). Leveraging large language models for automating water distribution network optimization. Water Research. Advance online publication. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S004313542501440X.

- Taormina, R., Kyritsakas, G., Sourlos, N., van der Werf, J. A., & Soodan, A. (2025). DRACO: A Large Language Model Initiative for Urban Water Systems. Paper presented at CCWI 2025 - 21st Computing & Control for the Water Industry Conference, Sheffield, UK.

- Miao, C., Hu, J., Moradkhani, H., & Destouni, G. (2024). Hydrological Research Evolution: A Large Language Model-Based Analysis of 310,000 Studies Published Globally Between 1980 and 2023. Water Resources Research, 60, e2024WR038077. [CrossRef]

- Collier, S. A., Deng, L., Adam, E. A., Benedict, K. M., Beshearse, E. M., Blackstock, A. J., … Beach, M. J. (2021). Estimate of burden and direct healthcare cost of infectious waterborne disease in the United States. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 27(1), 140–149. [CrossRef]

- Mounce, S. R., Gaffney, J. W., Boult, S. & Boxall, J. B. (2015). Automated data driven approaches to evaluating and interpreting water quality time series data from water distribution systems. ASCE Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management, Vol 141 (11), pp. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, K., Husband, S., & Boxall, J. B. (2025). Multi-parameter multi-sensor data fusion for drinking water distribution system water quality management. AQUA - Water Infrastructure, Ecosystems and Society, 74(7), 451–465. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Ma, W., Zhong, D., Ma, J., Zhang, Q., Yuan, Y., Liu, X., Wang, X., & Zou, K. (2024). Applications of machine learning in drinking water quality management: A critical review on water distribution system. Journal of Cleaner Production, 481, 144171. [CrossRef]

- Skipworth, P.J., Saul, A. & Machell, J. (1999). Predicting water quality in distribution using artificial neural networks, ICE J., Water Marit. Energy 136 (1) (1999) 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Singh, K. P., Basant, A., Malik, A., & Jain, G. (2009). Artificial neural network modeling of the river water quality—A case study. Ecology and Modelling, 220(5), 888–895. [CrossRef]

- Zhi, W., Feng, D., Tsai, W.-P., Sterle, G., Harpold, A., Shen, C., & Li, L. (2021). From hydrometeorology to river water quality: Can a deep learning model predict dissolved oxygen at the continental scale? Environmental Science & Technology, 55(4), 2357–2368. [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, K. P., & Mishra, A. K. (2024). Deep learning methods in hydrology and water resources: A critical review. Journal of Hydrology, 628, 130458. [CrossRef]

- Bi, J., Zhang, L., Yuan, H., & Zhang, J. (2023). Multi-indicator water quality prediction with attention-assisted bidirectional LSTM and encoder-decoder. Information Sciences, 625, 65–80. [CrossRef]

- Kyritsakas, G., Boxall, J., & Speight, V. (2024). A data-driven predictive model for disinfectant residual in drinking water storage tanks. AWWA Water Science, 6(3), Article e1376. [CrossRef]

- Eliades, D. G., Vrachimis, S. G., Moghaddam, A., Tzortzis, I., & Polycarpou, M. M. (2023). Contamination event diagnosis in drinking water networks: A review. Annual Reviews in Control, 55, 420–441. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J., Guo, X., Yan, X. & Hu, C. (2023). Review of urban drinking water contamination source identification methods. Energies, 16(2), 705. [CrossRef]

- Dogo, E. M., Nwulu, N. I., Twala, B., & Aigbavboa, C. (2019). A survey of machine learning methods applied to anomaly detection on drinking-water quality data. Urban Water Journal, 16(3), 235–248. [CrossRef]

- Qian, K., Jiang, J., Ding, Y., & Yang, S. (2020). Deep learning based anomaly detection in water distribution systems. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Networking, Sensing and Control (ICNSC) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Kadiyala, L., Mermer, O., Samuel, D. J., Sermet, Y., & Demir, I. (2024). The Implementation of Multimodal Large Language Models for Hydrological Applications: A Comparative Study of GPT-4 Vision, Gemini, LLaVa, and Multimodal-GPT. Hydrology, 11(9), 148. [CrossRef]

- Kalteh, A. M., Hjorth, P., & Berndtsson, R. (2008). Review of the self-organizing map (SOM) approach in water resources: Analysis, modelling and application. Environmental Modelling & Software, 23(7), 835–845. [CrossRef]

- Mounce, S. R., Douterelo, I., Sharpe, R.& Boxall, J. B. (2012). A bio-hydroinformatics application of self-organizing map neural networks for assessing microbial and physico-chemical water quality in distribution systems, Proceedings of 10th international conference on hydroinformatics, Hamburg, Germany.

- Mounce, S. R., Sharpe, R., Speight, V., Holden, B. & Boxall, J. B. (2014). Knowledge discovery from large disparate corporate databases using self-organising maps to help ensure supply of high quality potable water. Proceedings of 11th international conference on hydroinformatics, New York, USA.

- Speight, V., Mounce, S. R. and Boxall, J. B. (2019). Identification of the causes of drinking water discolouration from machine learning analysis of historical datasets. Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology (Royal Society of Chemistry), Vol 5, pp 747 – 755. [CrossRef]

- Mounce, S. R., Ellis, K., Edwards, J., Speight, V., Jakomis, N. and Boxall, J. B. (2017). Ensemble decision tree models using RUSBoost for estimating risk of iron failure in drinking water distribution systems. Water Resources Management,Vol 31 (5), pp 727-738. [CrossRef]

- Blokker, E. J. M., Furnass, W. R., Machell, J., Mounce, S. R., Schaap, P. G. & Boxall, J. B. (2016). Relating water quality and age in drinking water distribution systems using self-organising maps. Environments 3(2):10. [CrossRef]

- Mounce, S. R., Blokker, E. J. M., Husband, S. P., Furnass, W. R., Schaap, P. G. & Boxall, J. B. (2016). Multivariate data mining for estimating the rate of discoloration material accumulation in drinking water distribution systems. IWA J Hydroinf 18(1):96–114. [CrossRef]

- Mounce, S. R., Machell, J. & Boxall, J. B., (2012). Water quality event detection and customer complaint clustering analysis in distribution systems. IWA Journal of Water Science and Technology: Water Supply, Vol. 12 (5), pp. 580-587. [CrossRef]

- Sammon, J. W. (1969). A nonlinear mapping for data structure analysis. IEEE Trans Comput,C-18(5):401–409. [CrossRef]

- Furnass, W. R., Mounce, S. R., Husband, P. S., Collins, R. P. & Boxall, J. B. (2019). Calibrating and validating a combined accumulation and mobilisation model for water distribution system discolouration using particle swarm optimisation. Journal of Smart Water, Springer (Open Access),Vol 4 (3), pp 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Liu, H., Zhang, C., & Fu, G. (2023). Generative adversarial networks for detecting contamination events in water distribution systems using multi-parameter, multi-site water quality monitoring. Environmental Science & Ecotechnology, 14, 100231. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, D. J., Sermet, Y., Cwiertny, D. & Demir, I. (2024). Integrating vision-based AI and large language models for real-time water pollution surveillance. Water Environment Research, 96(8), e11092. [CrossRef]

- (2023). WaterWorld. Retrieved from https://www.waterworld.com/smart-water-utility/press-release/14295040/klir-unveils-chatgpt-integration-for-its-water-utility-management-platform. Accessed: September 2025.

- Pursnani, V., Erazo Ramirez, C., Sermet, M. Y., & Demir, I. (2024). HydroSuite-AI: Facilitating hydrological research with LLM-driven code assistance. EarthArXiv. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, D. J., Sermet, M. Y., Mount, J., Vald, G., Cwiertny, D., & Demir, I. (2024). Application of Large Language Models in Developing Conversational Agents for Water Quality Education, Communication and Operations. EarthArXiv, 7056. [CrossRef]

- Pursnani, V., Sermet, Y., Kurt, M., & Demir, I. (2023). Performance of ChatGPT on the US fundamentals of engineering exam: Comprehensive assessment of proficiency and potential implications for professional environmental engineering practice. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 5, 100183. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y., Zhang, T., Dong, X., Li, W., Wang, Z., He, J., Zhang, H., & Jiao, L. (2024). WaterGPT: Training a large language model to become a hydrology expert. Water, 16(21), 3075. [CrossRef]

- Xu, B., Wu, G., Li, Z., Xu, G., Zeng, H., Tong, R., & Ng, H. Y. (2025). Towards domain-adapted large language models for water and wastewater management: Methods, datasets and benchmarking. npj Clean Water, 8, 82. [CrossRef]

- DWI (2025). Drinking Water 2024: The Chief Inspector’s report for drinking water in England. Accessed: Sep 2025.

- Ofwat (2024). https://waterinnovation.challenges.org/news/discovery-winners/ Accessed: Sep 2025.

- Mounce, S. R., Mounce, R. B. and Boxall, J. B. (2016). Case-based reasoning to support decision making for managing drinking water quality events in distribution systems. Urban Water Journal, 13 (7), pp. 727–738. [CrossRef]

- Mounce, S. R., Mounce, R. B. & Boxall, J. B. (2025). Case-based reasoning and Generative AI decision support tools for managing drinking water quality events in distribution systems. Proceedings of the 21st International Computing and Control for the Water Industry (CCWI2025), Sheffield, UK, 1st to 3rd September 2025.

- Kyritsakas, G., Boxall, J.B. and Speight, V. (2023). A Big Data framework for actionable information to manage drinking water quality. Journal of Water Supply: Research and Technology-Aqua . [CrossRef]

- Leyden, T. & Hart-Davis, G. (2025). Agentic AI For Dummies®, Integrail Special Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Agentic Platforms and APIs: Global Market Outlook. (2025).

- Bresnahan, J., Gauthier, C., Gunkel, M., Hafskjold, H., Järvinen, M., Lindberg, K., Makropoulos, C., Neergaard, T. F. B., Niemi, P., Novara, V., O’Connor, M., Savic, D., Spreng, L., Taormina, R., Tondera, K., Urich, C., & Virtanen, V. (2022). IWA Trends and challenges in the water sector: A selection of insights from IWA Specialist Groups 2020–2021. Urban Water Journal, 19(5), 458–483.

- Daniel, I., Ajami, N. K., Castelletti, A., Savic, D., Stewart, R. A., & Cominola, A. (2023). A survey of water utilities’ digital transformation: drivers, impacts, and enabling technologies. npj Clean Water, 6(51). [CrossRef]

- The UK Water Partnership & Aiimi. (2025). AI Within Reach (White Paper). The UK Water Partnership. https://www.theukwaterpartnership.org/publications/ukwp-and-aiimi-ai-white-paper.

- Water Magazine. (2025). AI tool transforms access to UKWIR research. Water Magazine. https://www.watermagazine.co.uk/2025/08/05/ai-tool-transforms-access-to-ukwir-research/ Accessed: September 2025.

- Torello, M., Seshan, S., van der Meulen, S. & Vamvakeridou-Lyroudia, L. (2024). WATERVERSE: Strategies in stakeholder engagement for the digitalization of a water data management ecosystem. Engineering Proceedings, 69(1), 209. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, M. & Pandey, S. (2025). Water Sector 5.0: Harnessing digital transformation opportunities and mitigating risks. Water Resources Management. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).