Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

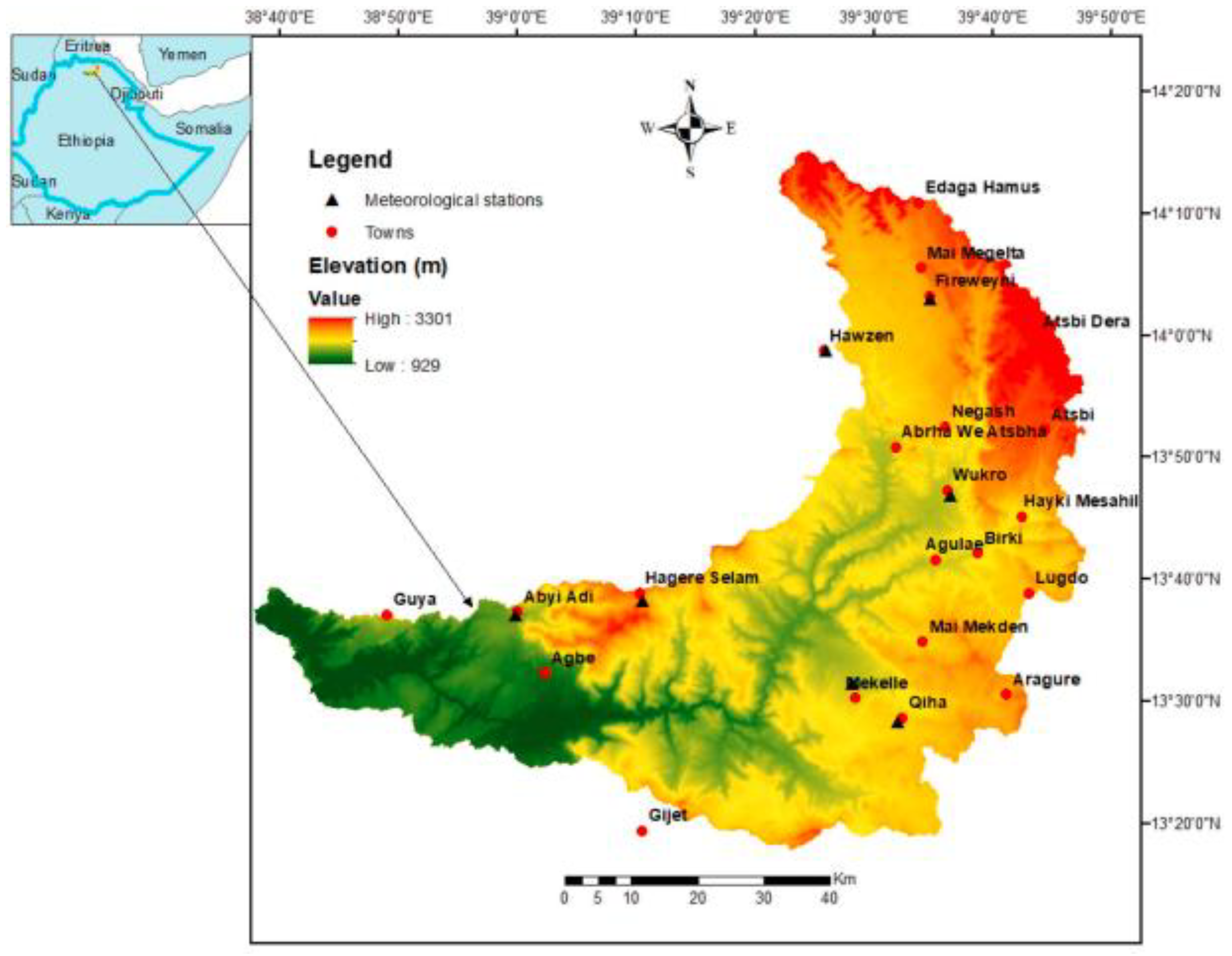

2.1. Study Area Description

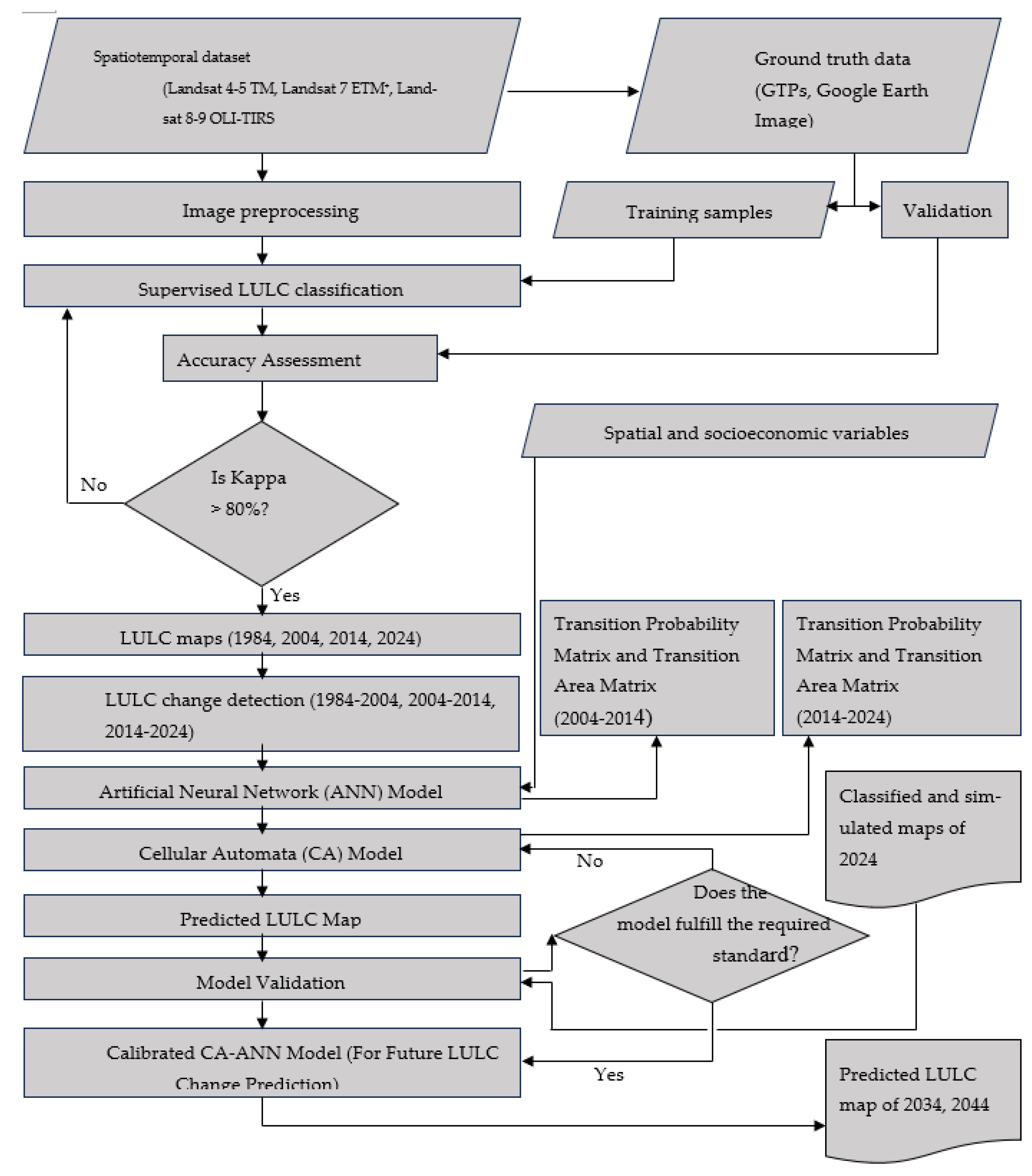

2.2. Data and Methods

2.2.1. Historical LULC Classification

2.2.2. Future LULC Prediction

3. Results and Discussion

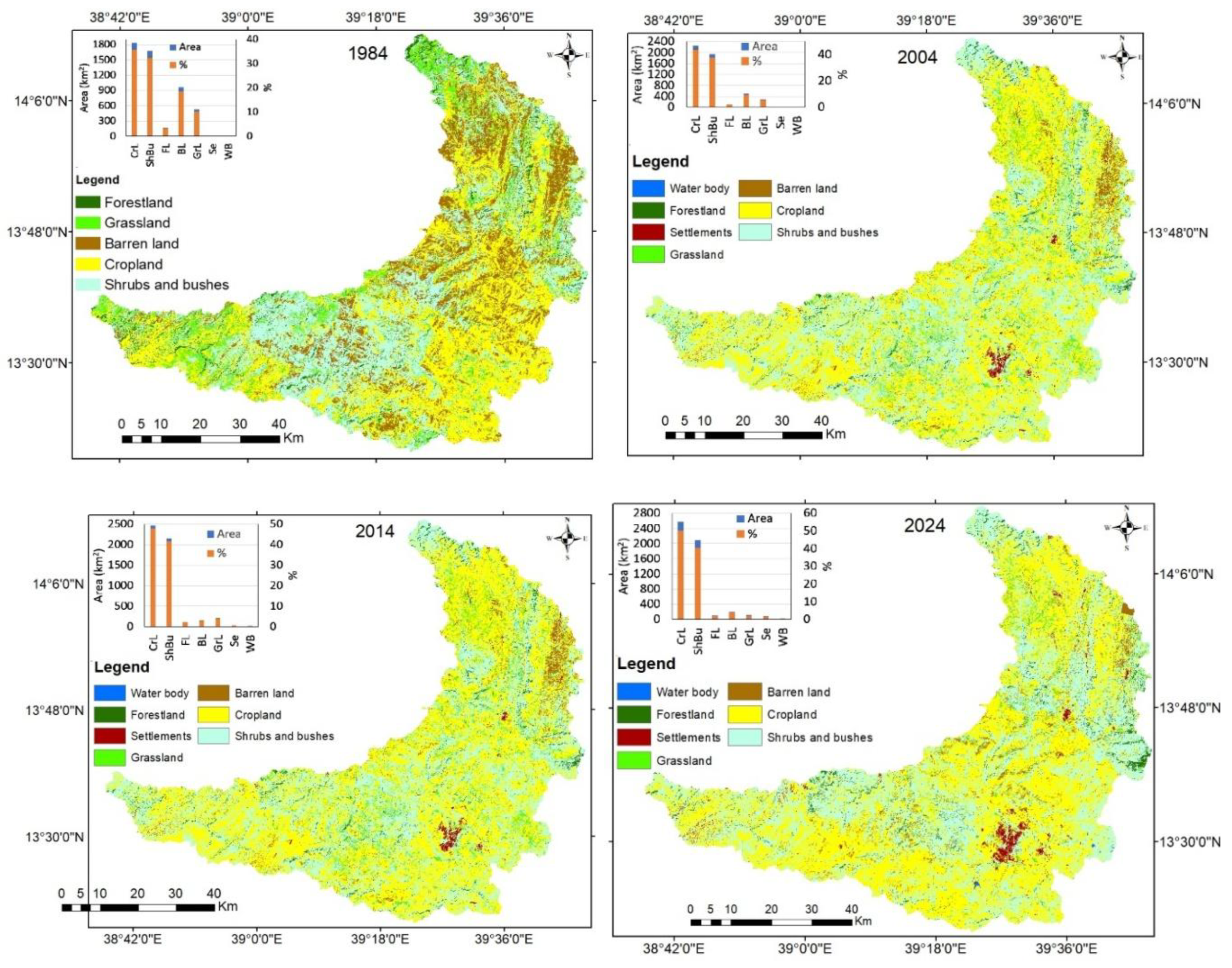

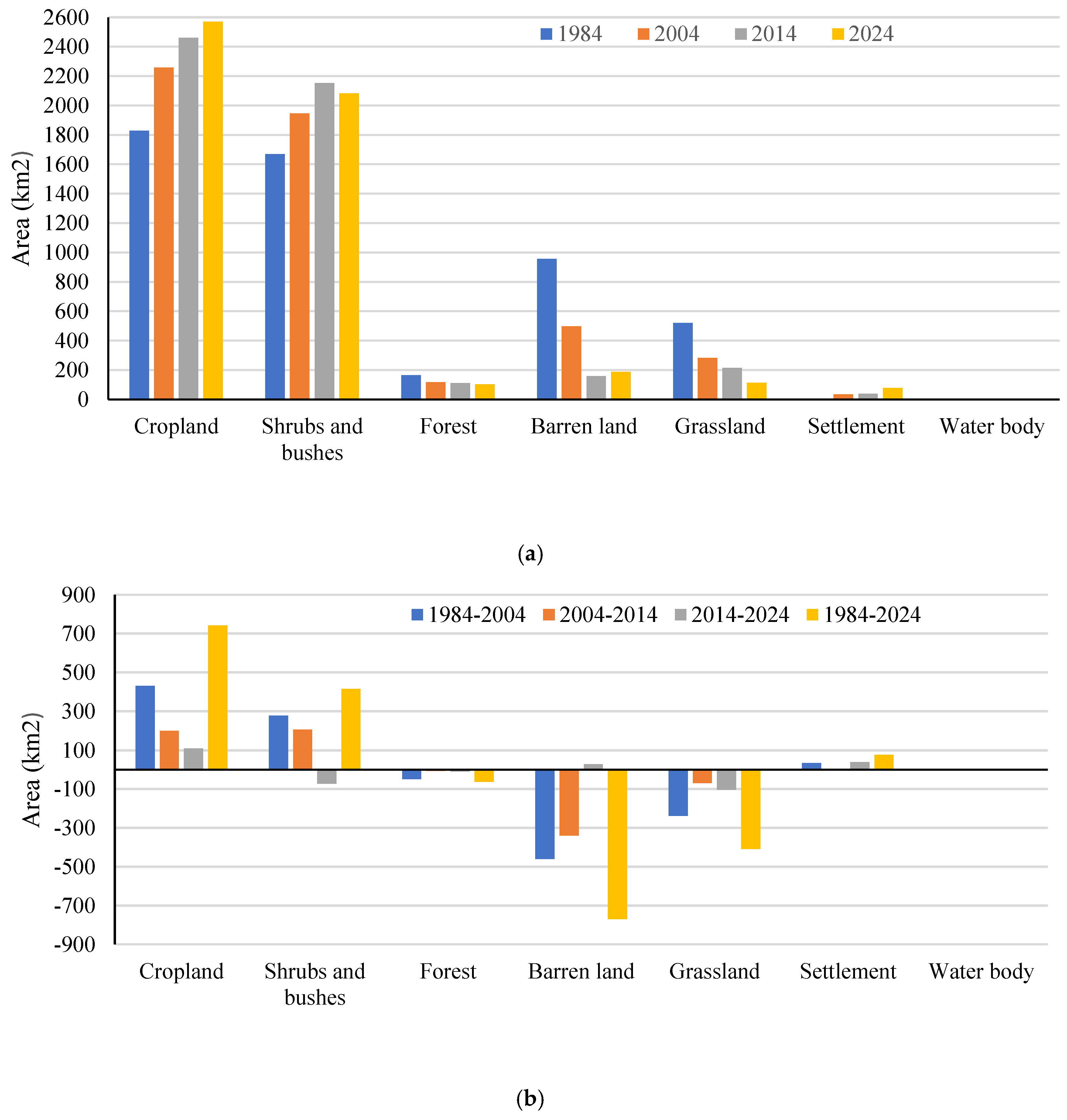

3.1. LULC Classification and Change Detection

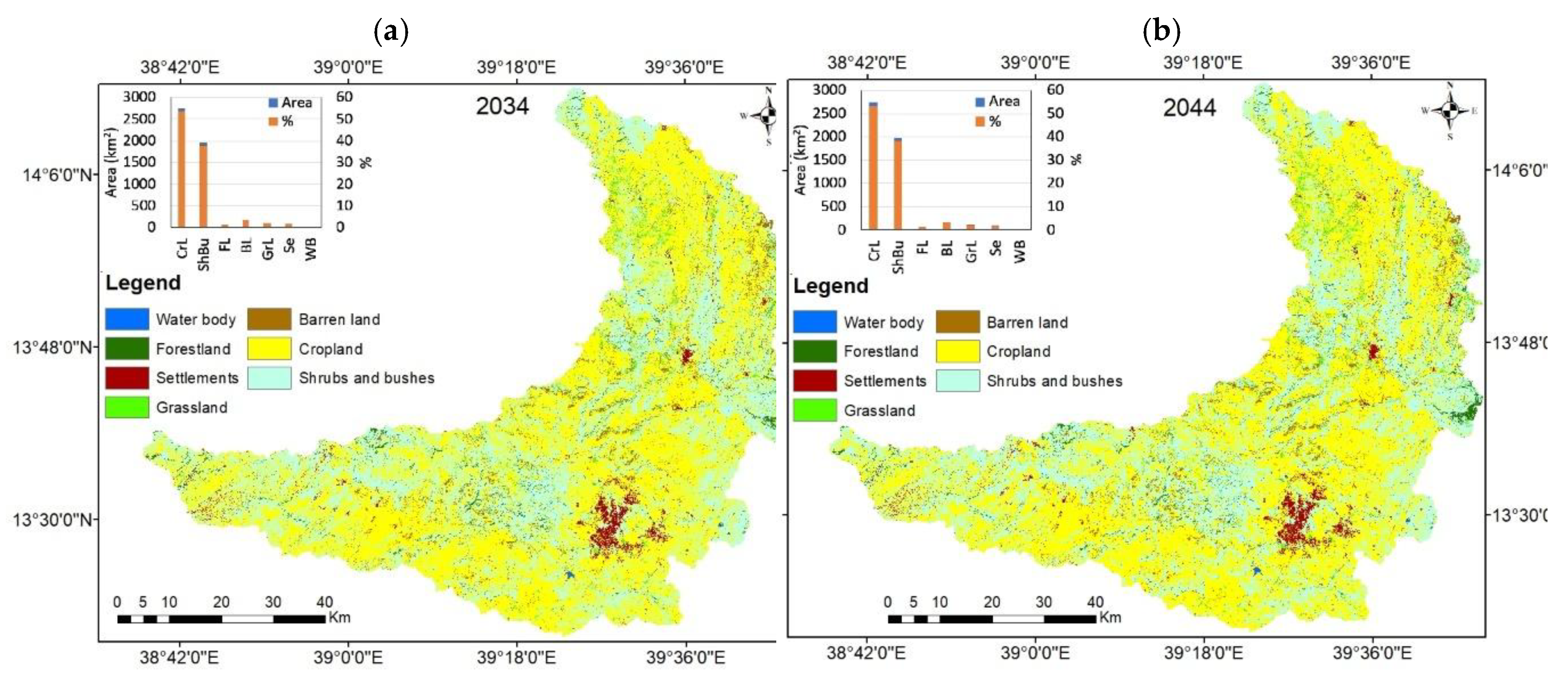

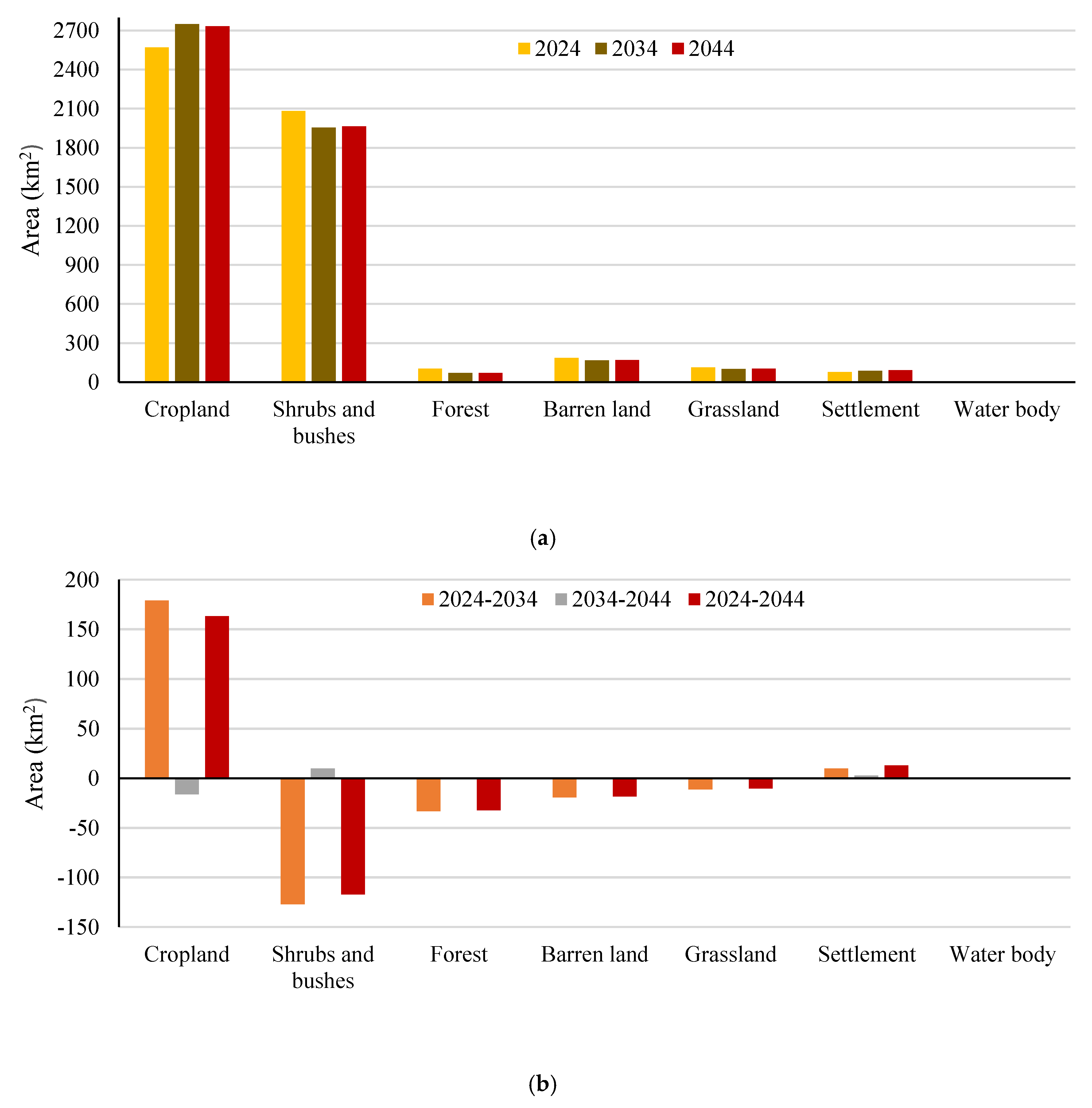

3.2. Future LULC Projection

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lambin, E.F.; Turner, B.L.; Geist, H.J.; Agbola, S.B.; Angelsen, A.; Bruce, J.W.; Coomes, O.T.; Dirzo, R.; Folke, C.; Bruce, J.W.; et al. The causes of land-use and land-cover change : moving beyond the myths. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2001, 11, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, R.; Pielke Sr, R.A.; Hubbard, K.G.; Niyogi, D.; Bonan, G.; Lawrence, P.; Mcnider, R.; Mcalpine, C.; Etter, A.; Gameda, S.; et al. Impacts of Land Use/Land Cover Change on Climate and Future Research Priorities. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2010, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, A.; Poesen, J.; Haile, M.; Deckers, J.; Nyssen, J. Geomorphology Quantifying long-term changes in gully networks and volumes in dryland environments : The case of Northern Ethiopia. Geomorphology 2013, 201, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremicael, T.G.; Mohamed, Y.A.; Zaag, P. Van Der; Hagos, E.Y. Quantifying longitudinal land use change from land degradation to rehabilitation in the headwaters of Tekeze-Atbara Basin, Ethiopia. Sci. Total Environ. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyssen, J.; Poesen, J.; Moeyersons, J.; Deckers, J.; Haile, M.; Lang, A. Human impact on the environment in the Ethiopian and Eritrean highlands — a state of the art. Earth-Science Rev. 2004, 64, 273–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreyohannes, T.; Smedt, F. De; Walraevens, K.; Gebresilassie, S.; Hussien, A.; Hagos, M.; Amare, K.; Deckers, J.; Gebrehiwot, K. Application of a spatially distributed water balance model for assessing surface water and groundwater resources in the Geba basin, Tigray, Ethiopia. J. Hydrol. 2013, 499, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebru, A.B.; Gebreyohannes, T.; Kahsay, G.H. Modelling climate change and aridity for climate impact studies in semi-arid regions: The case of Giba basin, northern Ethiopia. Heliyon 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtie, T.T.; Teferi, E.; Guta, F. Multi-level determinants of land use land cover change in Tigray, Ethiopia : A mixed- effects approach using socioeconomic panel and satellite data. PLoS One 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyassa, E.; Frankl, A.; Lanckriet, S.; Demissie, B.; Zenebe, G.; Zenebe, A. Changes in land use / cover mapped over 80 years- in the Highlands of Northern Ethiopia. 2018, 28, 1538–1559.

- Kiptala, J.K.; Mohamed, Y.; Mul, M.L.; Cheema, M.J.M.; Van der Zaag, P. Land use and land cover classification using phenological variability from MODIS vegetation in the Upper Pangani River Basin, Eastern Africa. Phys. Chem. Earth 2013, 66, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betru, T.; Tolera, M.; Sahle, K.; Kassa, H. Trends and drivers of land use / land cover change in Western Ethiopia. Appl. Geogr. 2019, 104, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.L.; Lambin, E.F.; Reenberg, A. The emergence of land change science for global environmental change and sustainability. PNAS 2007, 105, 20690–20695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallupattu, P.K.; Reddy, J.R.S. Analysis of Land Use / Land Cover Changes Using Remote Sensing Data and GIS at an Urban Area, Tirupati, India. Sci. J. 2013, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburg, P.H.; Schot, P.P.; Dijst, M.J.; Veldkamp, A. Land use change modelling : current practice and research priorities. GeoJournal 2004, 61, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halmy, M.W.A.; Gessler, P.E.; Hicke, J.A.; Salem, B.B. Land use / land cover change detection and prediction in the north-western coastal desert of Egypt using Markov-CA. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 63, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, C.; Green, G.M.; Grove, J.M.; Evans, T.P.; Schweik, C.M. A Review and Assessment of Land-Use Change Models: Dynamics of Space, Time, and Human Choice; General Technical Report; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station: Newton Square, PA, USA; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Q. Land use change analysis in the Zhujiang Delta of China using satellite remote sensing, GIS and stochastic modelling. J. Environ. Manage. 2002, 64, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamaraj, M.; Rangarajan, S. Predicting the future land use and land cover changes for Bhavani basin, Tamil Nadu, India, using QGIS MOLUSCE plugin. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, W. Multiple land use change simulation with Monte Carlo approach and CA-ANN model, a case study in Shenzhen, China. Environ. Syst. Res. 2015, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koko, A.F.; Yue, W.; Abubakar, G.A.; Hamed, R.; Alabsi, A.A.N. Monitoring and Predicting Spatio-Temporal Land Use / Land Cover Changes in Zaria City, Nigeria, through an Integrated Cellular Automata and Markov Chain Model (CA-Markov). Sustainability 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.C.; Gaydos, L.J. Loose-coupling a cellular automaton model and GIS : long-term urban growth prediction for San Francisco and Washington / Baltimore. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 1998, 12, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidey, E.; Dikinya, O.; Sebego, R.; Segosebe, E.; Zenebe, A. Cellular automata and Markov Chain ( CA _ Markov ) model-based predictions of future land use and land cover scenarios ( 2015 – 2033 ) in Raya, northern Ethiopia. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2017, 0, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadese, S.; Soromessa, T.; Bekele, T. Analysis of the Current and Future Prediction of Land Use/Land Cover Change Using Remote Sensing and the CA-Markov Model in Majang Forest Biosphere Reserves of Gambella, Southwestern Ethiopia. Sci. World J. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entahabu, H.H.; Minale, A.S.; Birhane, E. Modeling and Predicting Land Use/Land Cover Change Using the Land Change Modeler in the Suluh River Basin, Northern Highlands of Ethiopia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshetie, A.A.; Wubneh, M.A.; Kifelew, M.S.; Alemu, M.G. Application of artificial neural network ( ANN ) for investigation of the impact of past and future land use – land cover change on streamflow in the Upper Gilgel Abay watershed, Abay Basin, Appl. Water Sci. 2023, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, P.; Melesse, A.M.; Kenea, T.T. Prediction of Future Land Use / Land Cover Changes Using a Coupled CA-ANN Model in the Upper Omo – Gibe River. Remote Sens. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfagiorgis, K.; Gebreyohannes, T.; De Smedt, F.; Moeyersons, J.; Hagos, M.; Nyssen, J.; Deckers, J. Evaluation of groundwater resources in the Geba basin, Ethiopia. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2010, 70, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godif, G.; Manjunatha, B.R. Prioritizing sub-watersheds for soil and water conservation via morphometric analysis and the weighted sum approach : A case study of the Geba river basin in Tigray, Ethiopia. Heliyon 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyssen, J.; Frankl, A.; Haile, M.; Hurni, H.; Descheemaeker, K.; Crummey, D.; Ritler, A.; Portner, B.; Nievergelt, B.; Moeyersons, J.; et al. Environmental conditions and human drivers for changes to north Ethiopian mountain landscapes over 145 years. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanckriet, S.; Derudder, B.; Naudts, J.; Bauer, H.; Deckers, J.; Haile, M.; Nyssen, J. A Political Ecology Perspective of Land Degradation in the North Ethiopian Highlands. L. Degrad. Dev. 2015, 26, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meaza, H.; Ghebreyohannes, T.; Tesfamariam, Z.; Gebresamuel, G.; Demissie, B.; Gebregziabher, D.; Nyssen, J. The effects of armed conflict on natural resources and conservation measures in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondie, M.; Schneider, W.; Melesse, A.M.; Teketay, D. Spatial and Temporal Land Cover Changes in the Simen Mountains National Park, a World Heritage Site in Northwestern Ethiopia. Remote Sens. 2011, 3, 752–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meire, E.; Frankl, A.; Wulf, A. De; Haile, M.; Deckers, J.; Nyssen, J. Land use and cover dynamics in Africa since the nineteenth century : warped terrestrial photographs of North Ethiopia. 2013, 717–737. [CrossRef]

- Congalton, R.G. Accuracy assessment and validation of remotely sensed and other spatial information. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2001, 10, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haregeweyn, N.; Poesen, J.; Nyssen, J.; Wit, J. De; Haile, M.; Govers, G.; Deckers, S. Reservoirs in Tigray (Northern Ethiopia): Characteristics and Sediment Deposition Problems. L. Degrad. Dev. 2006, 17, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, R.N.; Deckers, J.; Haile, M.; Grove, A.T.; Poesen, J.; Nyssen, J. Soil landscapes, land cover change and erosion features of the Central Plateau region of Tigrai, Ethiopia : Photo-monitoring with an interval of 30 years. Catena 2008, 75, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyssen, J.; Clymans, W.; Descheemaeker, K.; Poesen, J.; Vandecasteele, I.; Vanmaercke, M.; Zenebe, A.; Camp, M. Van; Haile, M.; Haregeweyn, N.; et al. Impact of soil and water conservation measures on catchment hydrological response — a case in north Ethiopia. Hydrol. Process. 2010, 24, 1880–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hishe, S.; Gidey, E.; Zenebe, A.; Bewket, W.; Lyimo, J.; Knight, J.; Gebretekle, T. The impacts of armed con fl ict on vegetation cover degradation in. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2024, 12, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraha, A.Z. Assessment of spatial and temporal variability of river discharge , sediment yield and sediment-fixed nutrient export in Geba River catchment, northern Ethiopia. PhD Thesis, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven., 2009.

- Ashenafi, A.A. Modeling Hydrological Responses to Changes in Land Cover and Climate in Geba River Basin , Northern Ethiopia. 2014.

- Abebe, B.A. Modeling the Effect of Climate and Land Use Change on the Water Resources in Northern Ethiopia: the Case of Suluh River Basin. PhD Thesis, Freie Universität Berlin., 2014.

- Gebremicael, T.G.; Mohamed, Y.A.; van der Zaag, P.; Hagos, E.Y. Quantifying longitudinal land use change from land degradation to rehabilitation in the headwaters of Tekeze-Atbara Basin, Ethiopia. Sci. Total Environ. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Satellite | Sensor | Path/row | Resolution (m) | Acquisition date |

| Landsat 4-5 | TM Multispectral | 168/50 168/51 169/50 169/51 |

30 | 03/09/1984 30/10/1984 |

| Landsat 7 | ETM+ Multispectral | 30 | 05/11/2004 14/11/2004 |

|

| Landsat 8 | OLI-TIRS | 30 | 17/10/2014 24/10/2014 |

|

| Landsat 9 | OLI-TIRS | 30 | 18/09/2024 25/09/2024 |

| LULC class | Code | Description |

| Water body (WB) | 0 | All types of surface water, mainly small man-made lakes |

| Forestland (FL) | 1 | Forests that are tall and dense, and mainly located in churches and closed areas |

| Settlements (Se) | 2 | Bult up areas including villages, towns, and cities |

| Grassland (GrL) | 3 | Areas covered with grasses, e.g., grazing lands |

| Barren land (BL) | 4 | Open spaces with no vegetation, e.g., degraded lands and rock outcrops |

| Cropland (CrL) | 5 | Areas covered with all types of crops in the whole year |

| Shrubs and bushes (ShBu) | 6 | Areas covered by low-woody and less-dense vegetation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).