Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

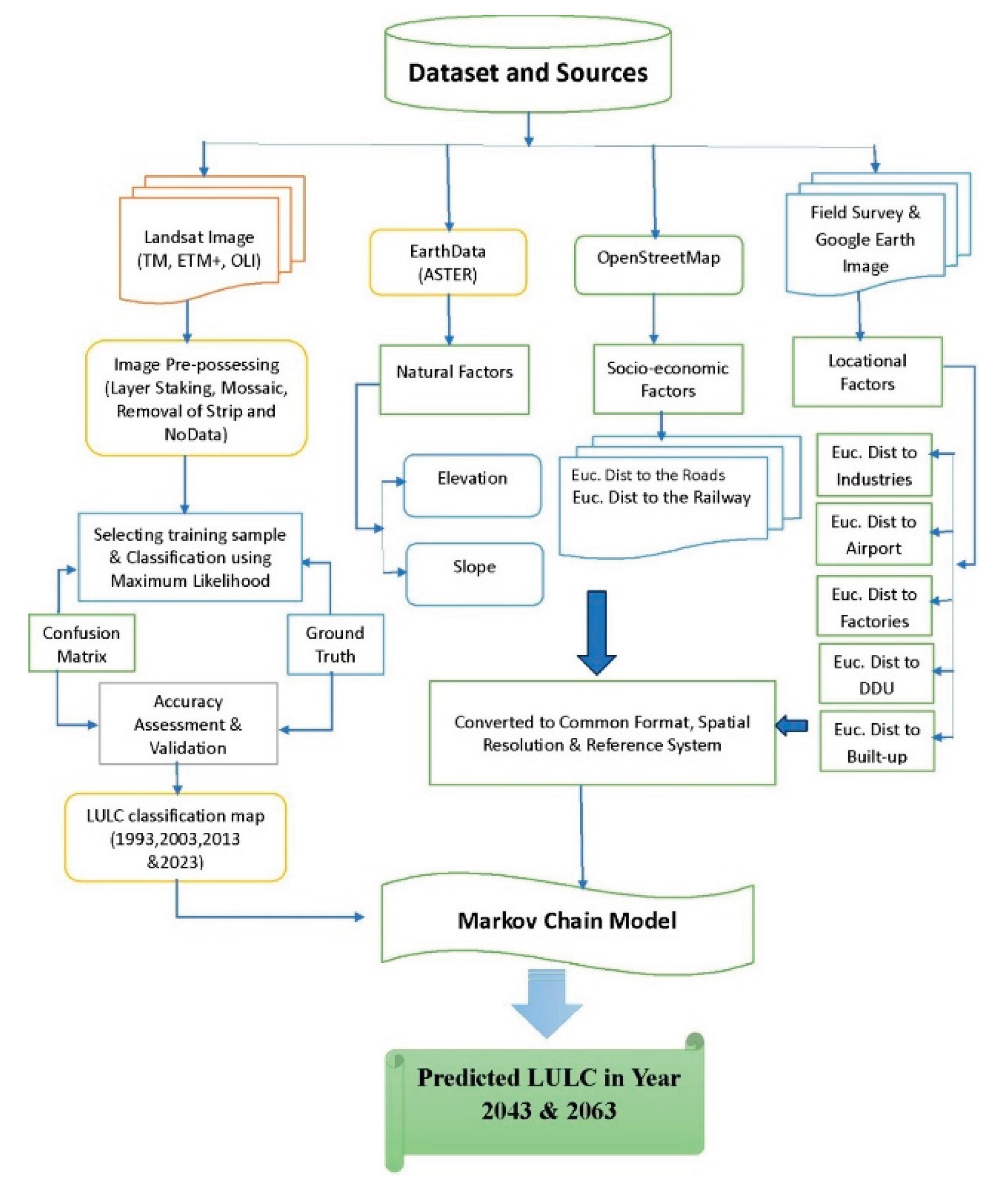

2. Materials and Methods

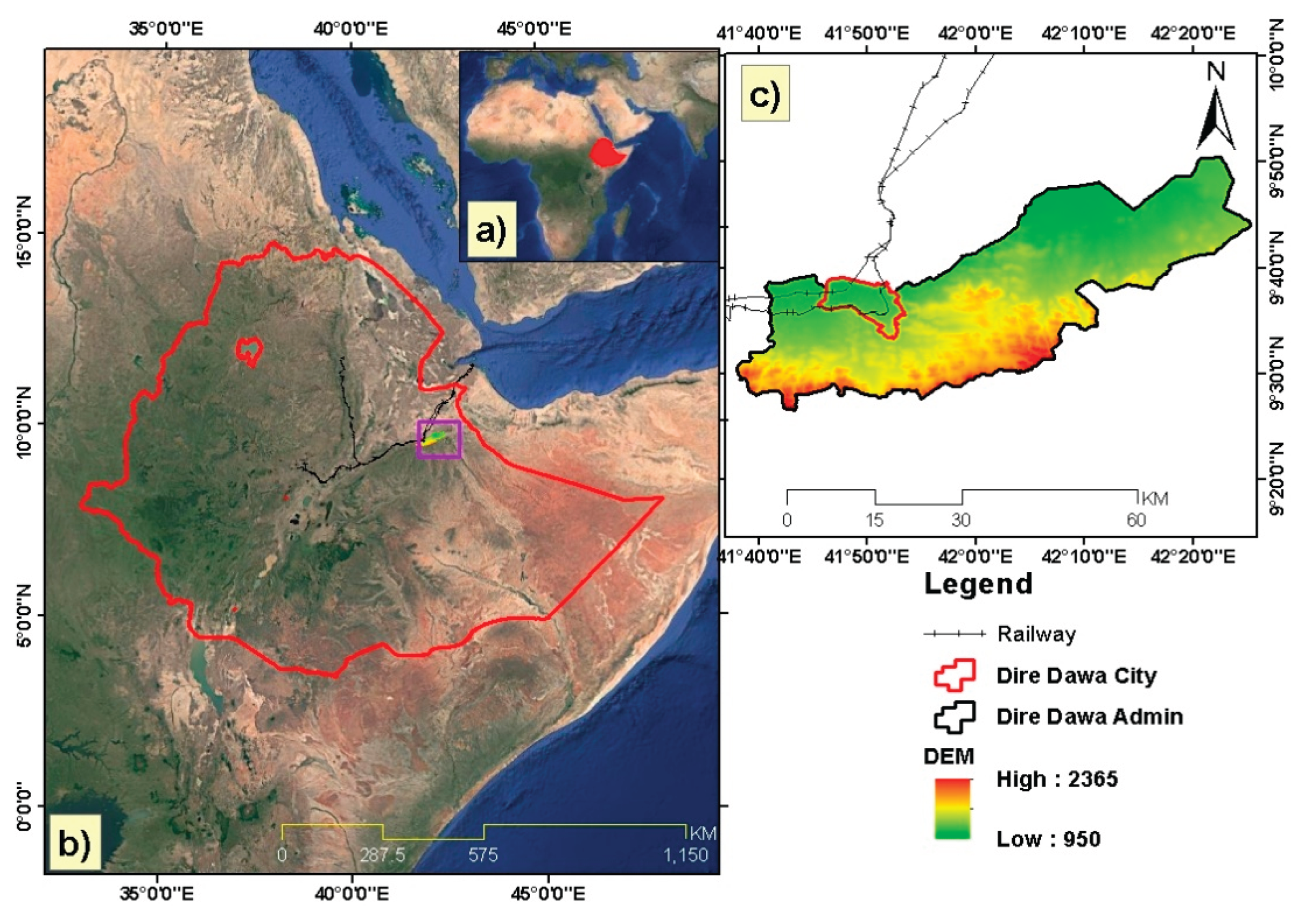

2.1. Description of the Study Area

2.2. Data Source and Processing

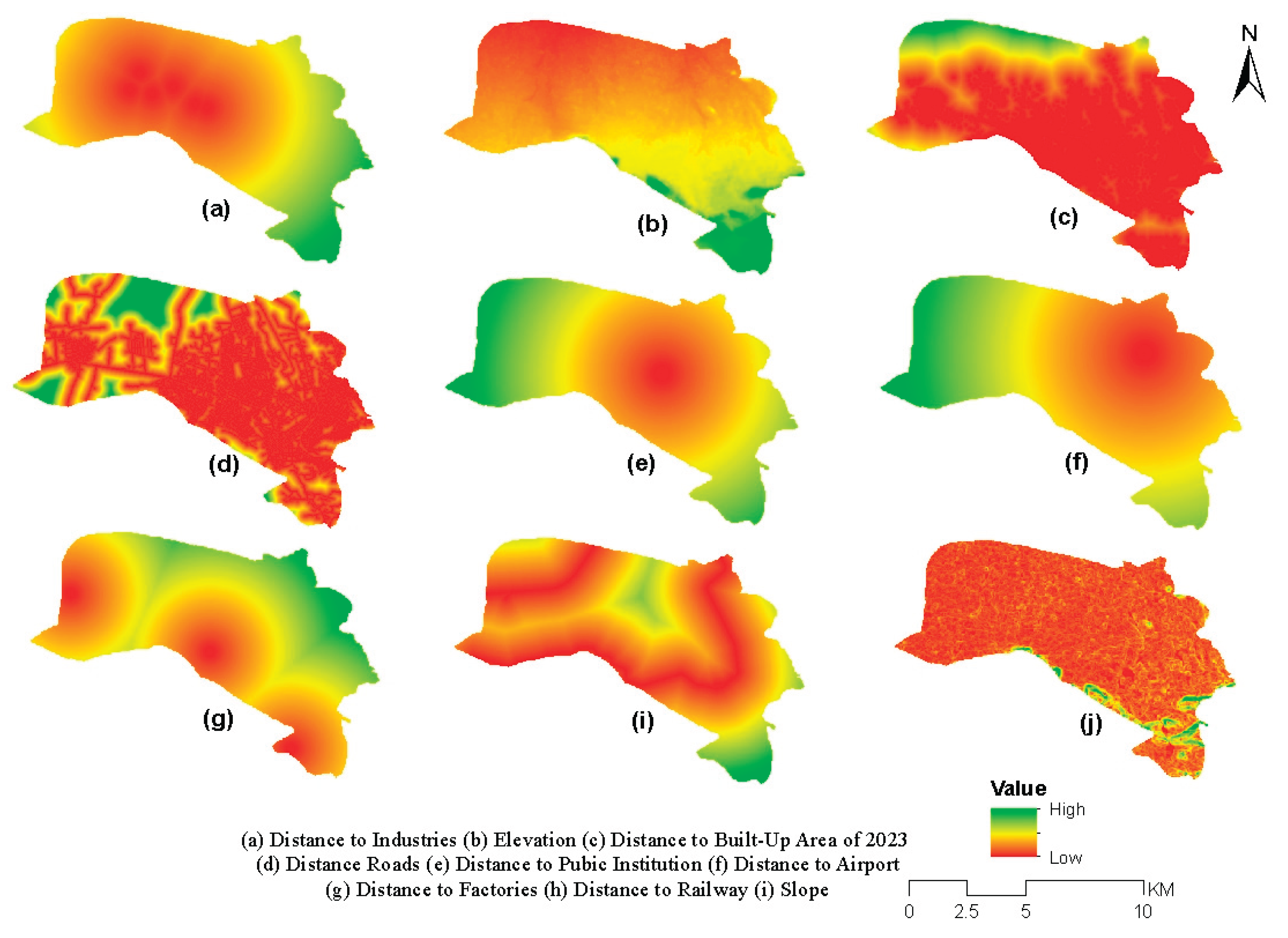

2.3. Drivers of Urban Expansion and Hypothesis

3. Method of Data Analysis for Urban Expansion and Simulation

3.1. Rate of Urban Expansion

3.2. Landscape Expansion Index

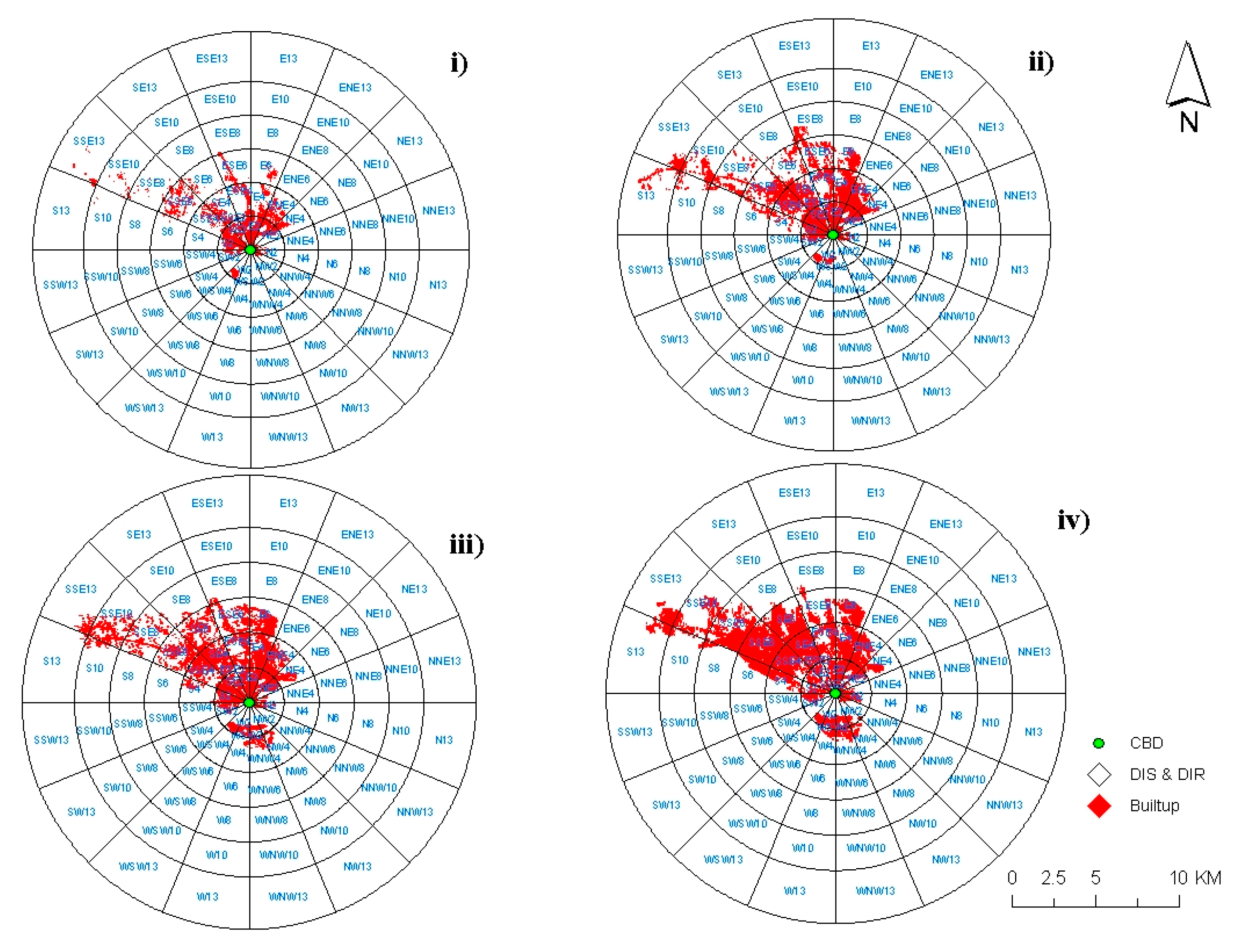

3.3. Urban Expansion Direction

3.4. Simulation of Urban Expansion

4. Results

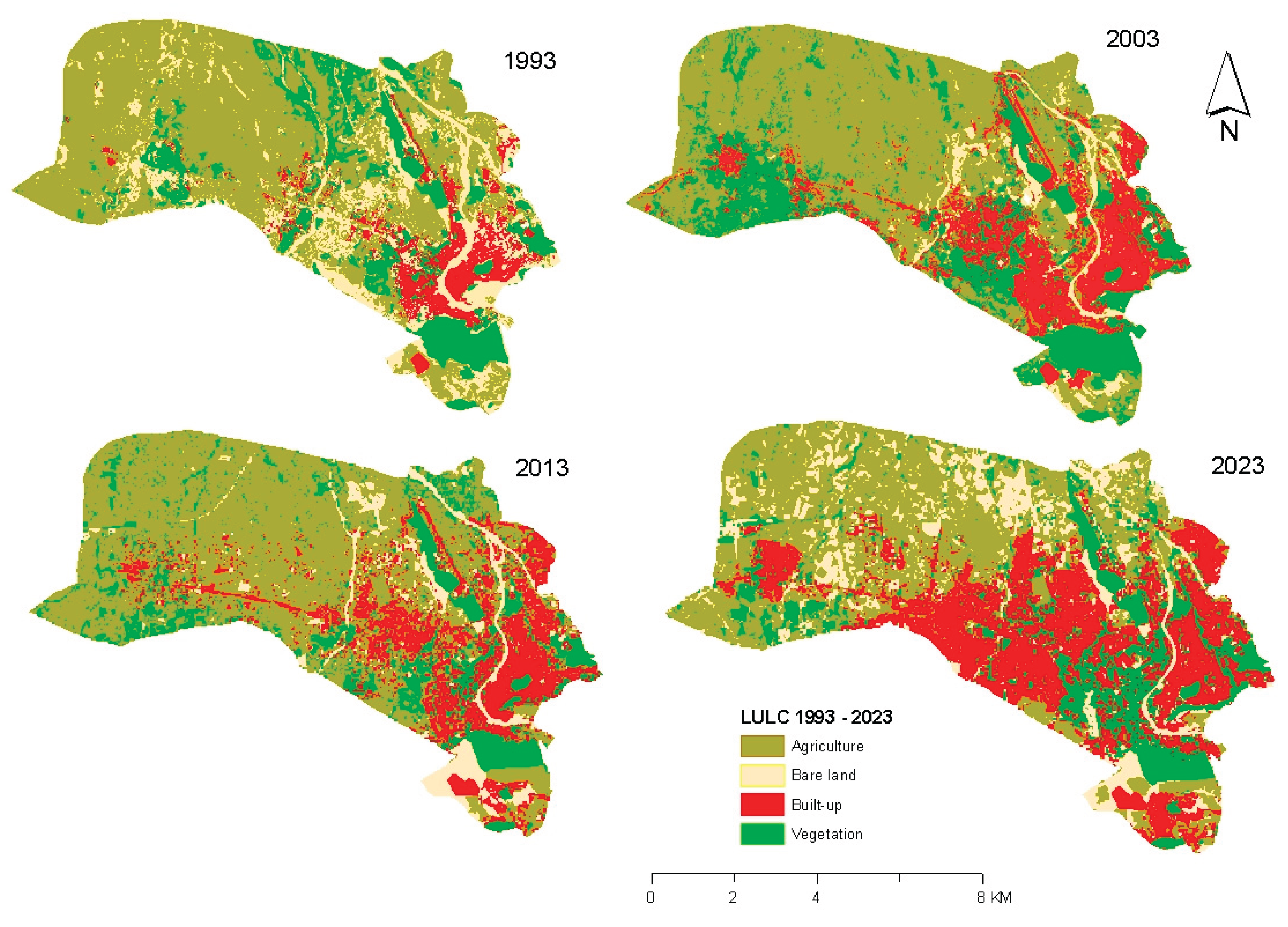

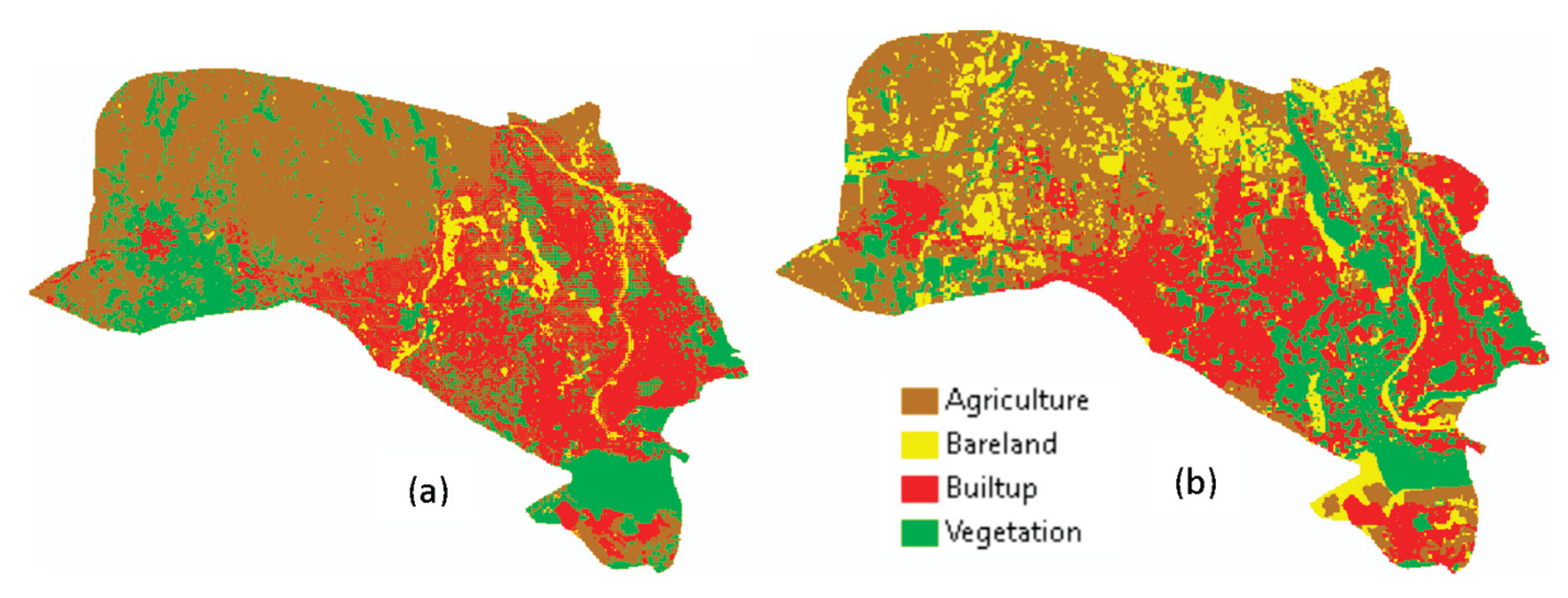

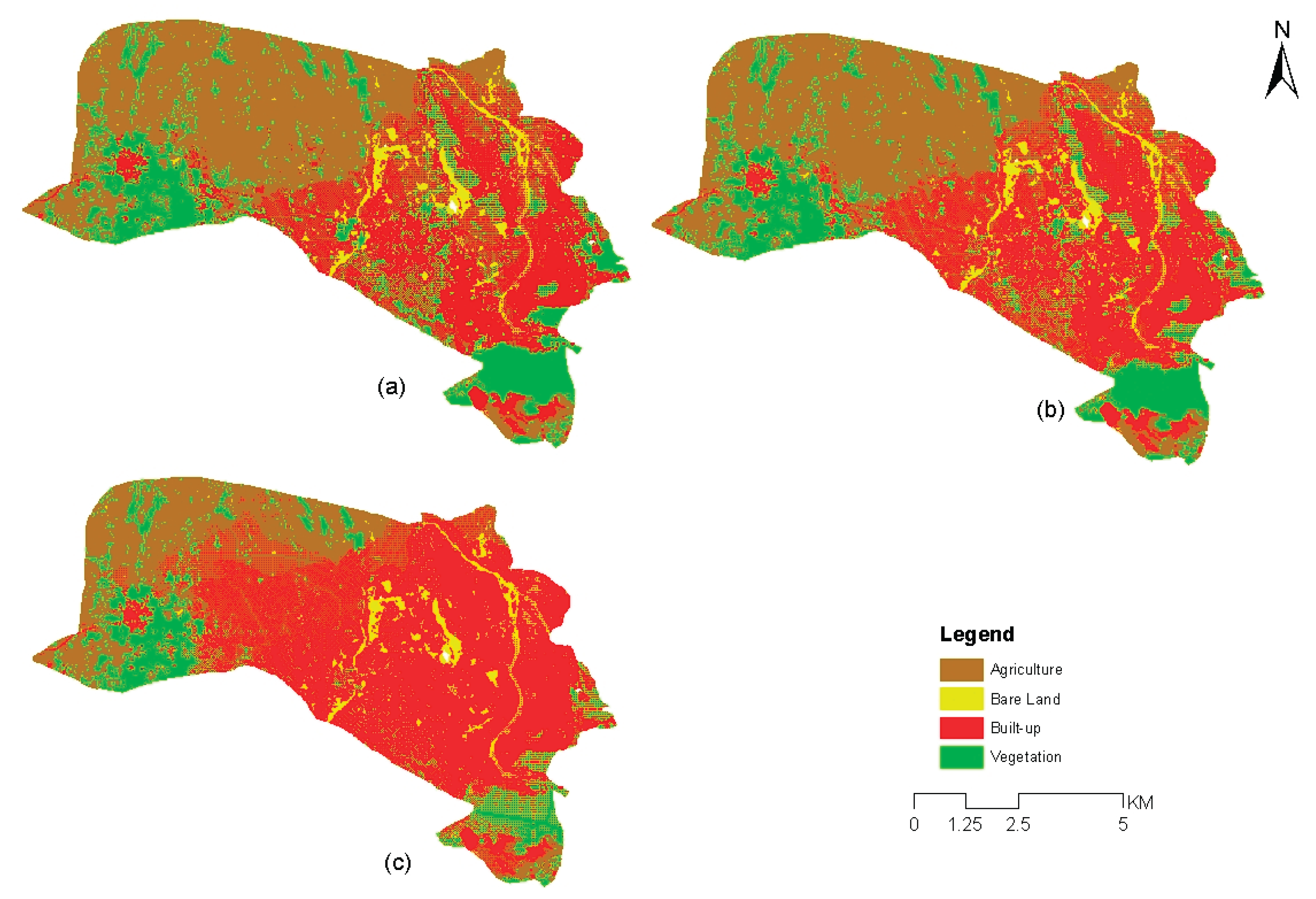

4.1. LULC Map of the Study Area

| LULC Class | 1993 | 2003 | 2013 | 2023 | ||||

| Area (KM2) | % | Area (KM2) | % | Area (KM2) | % | Area (KM2) | % | |

| Agriculture | 41.62 | 54.02 | 40.28 | 52.23 | 43.50 | 56.46 | 29.33 | 38.07 |

| Bare land | 15.20 | 19.72 | 4.55 | 5.90 | 6.14 | 7.97 | 11.49 | 14.92 |

| Built-up | 6.21 | 8.06 | 12.55 | 16.27 | 13.76 | 17.86 | 21.54 | 27.96 |

| Vegetation | 14.02 | 18.20 | 19.75 | 25.60 | 13.64 | 17.70 | 14.68 | 19.06 |

4.2. Accuracy Assessment for the Classified Map

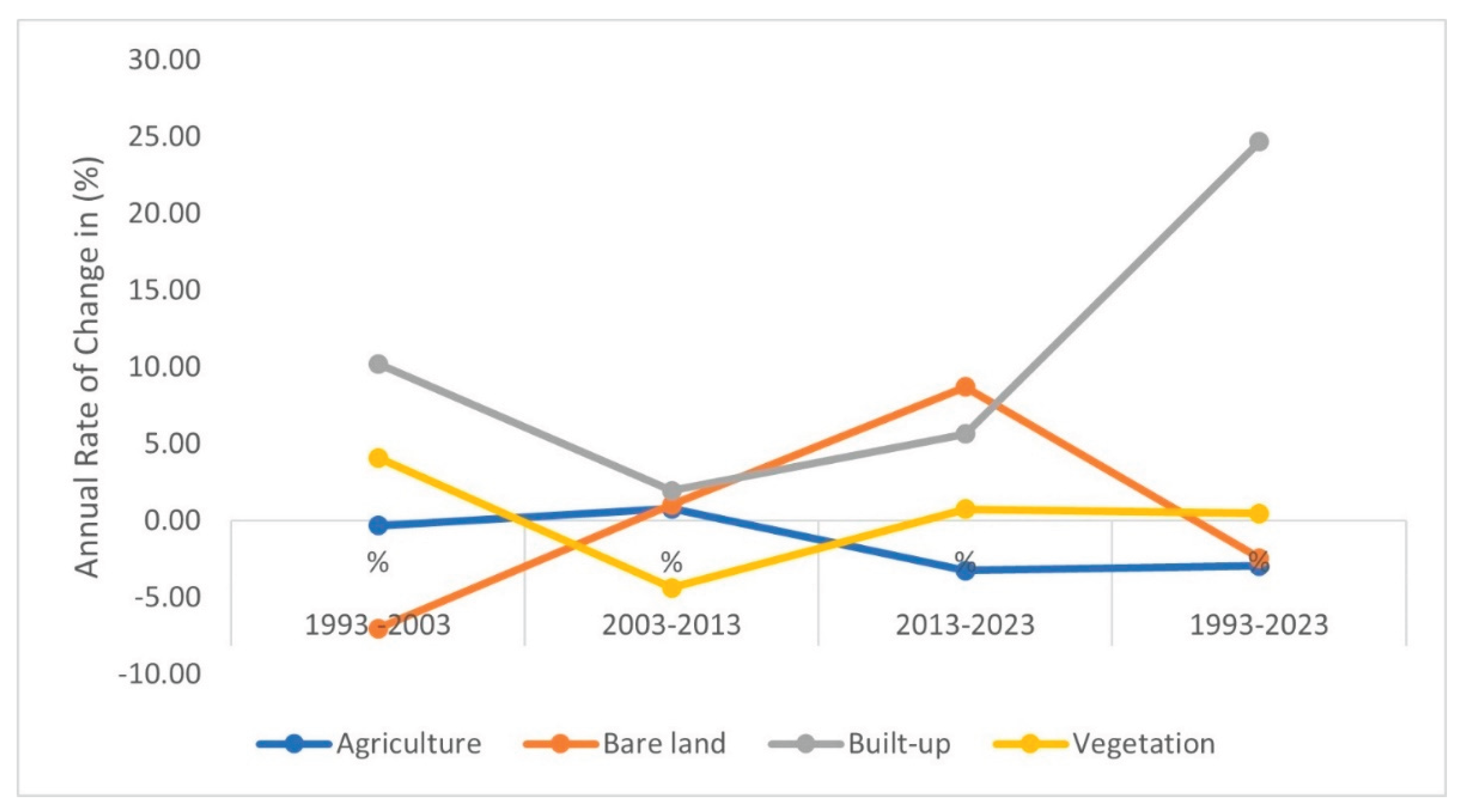

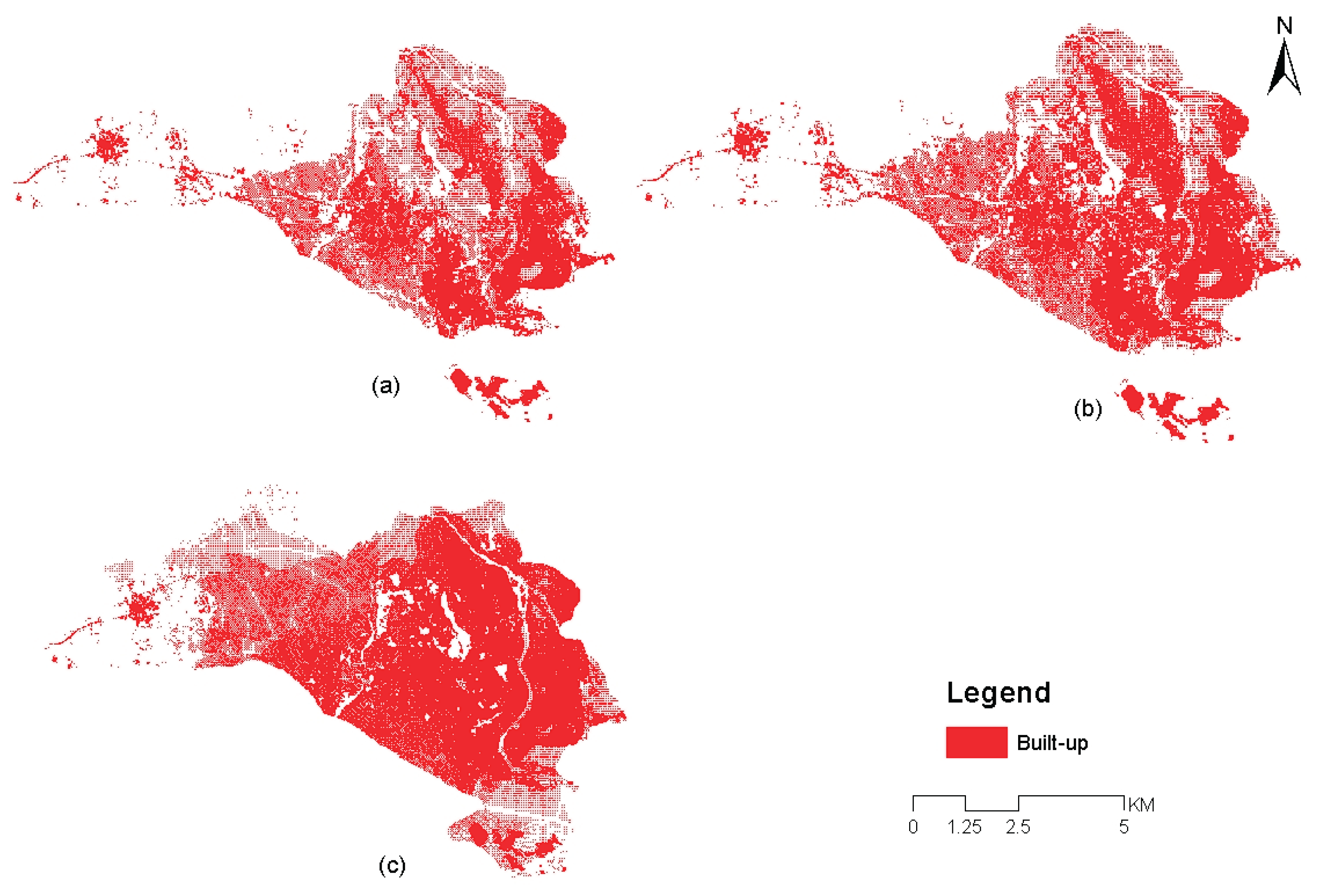

4.3. Rate of Urban Expansion from 1993 – 2023

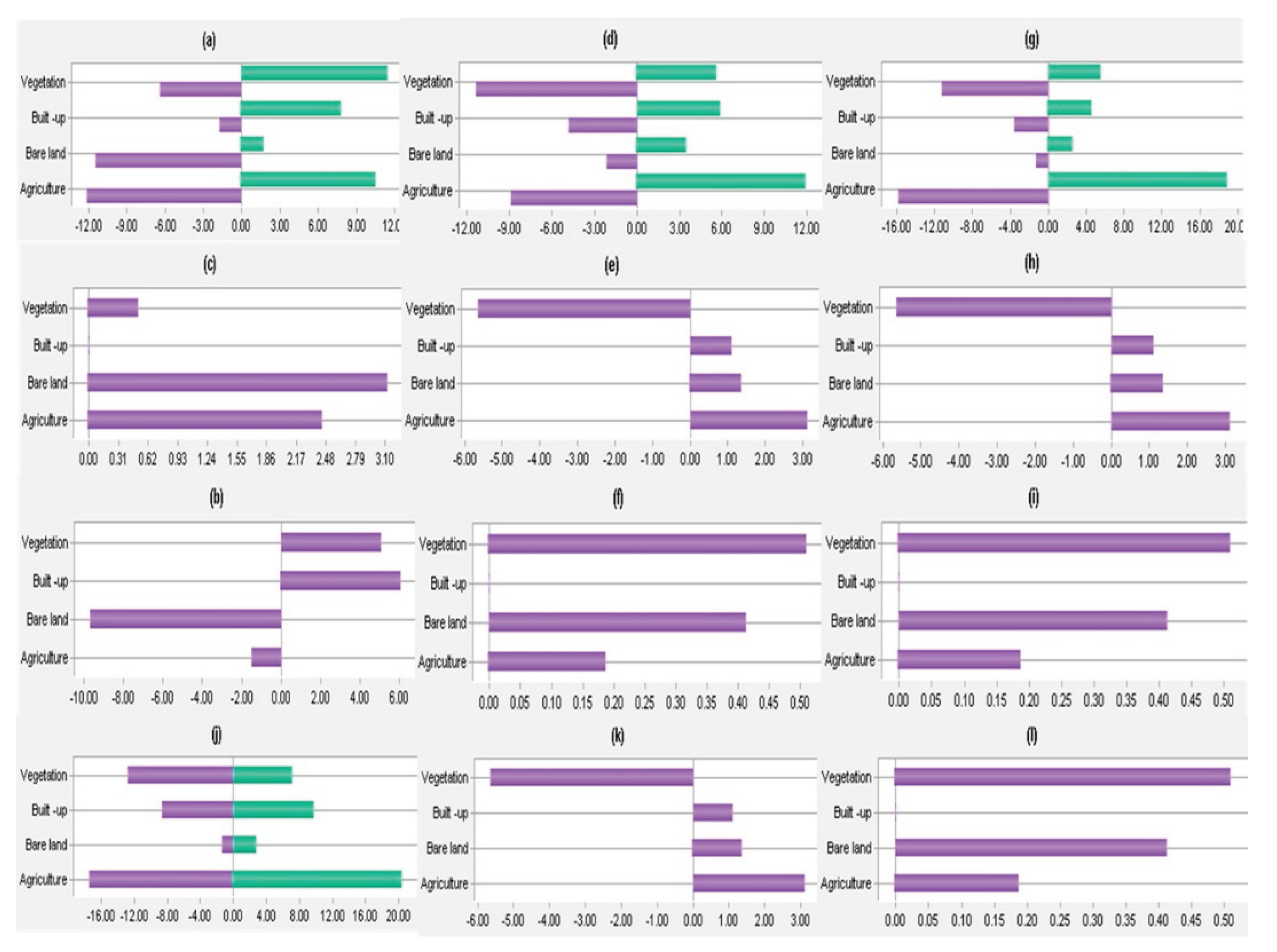

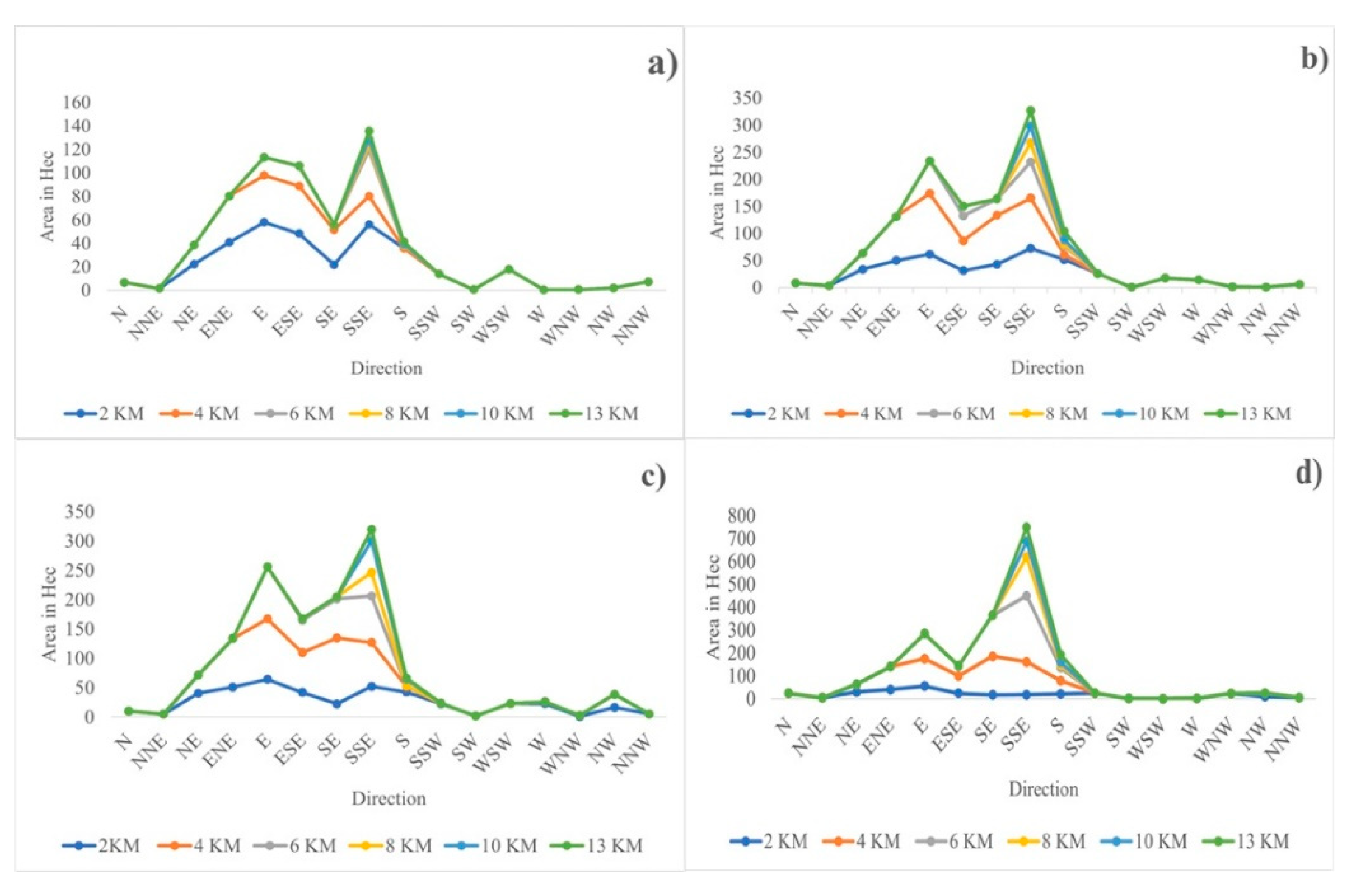

4.4. Directional Concentration of Urban Expansion

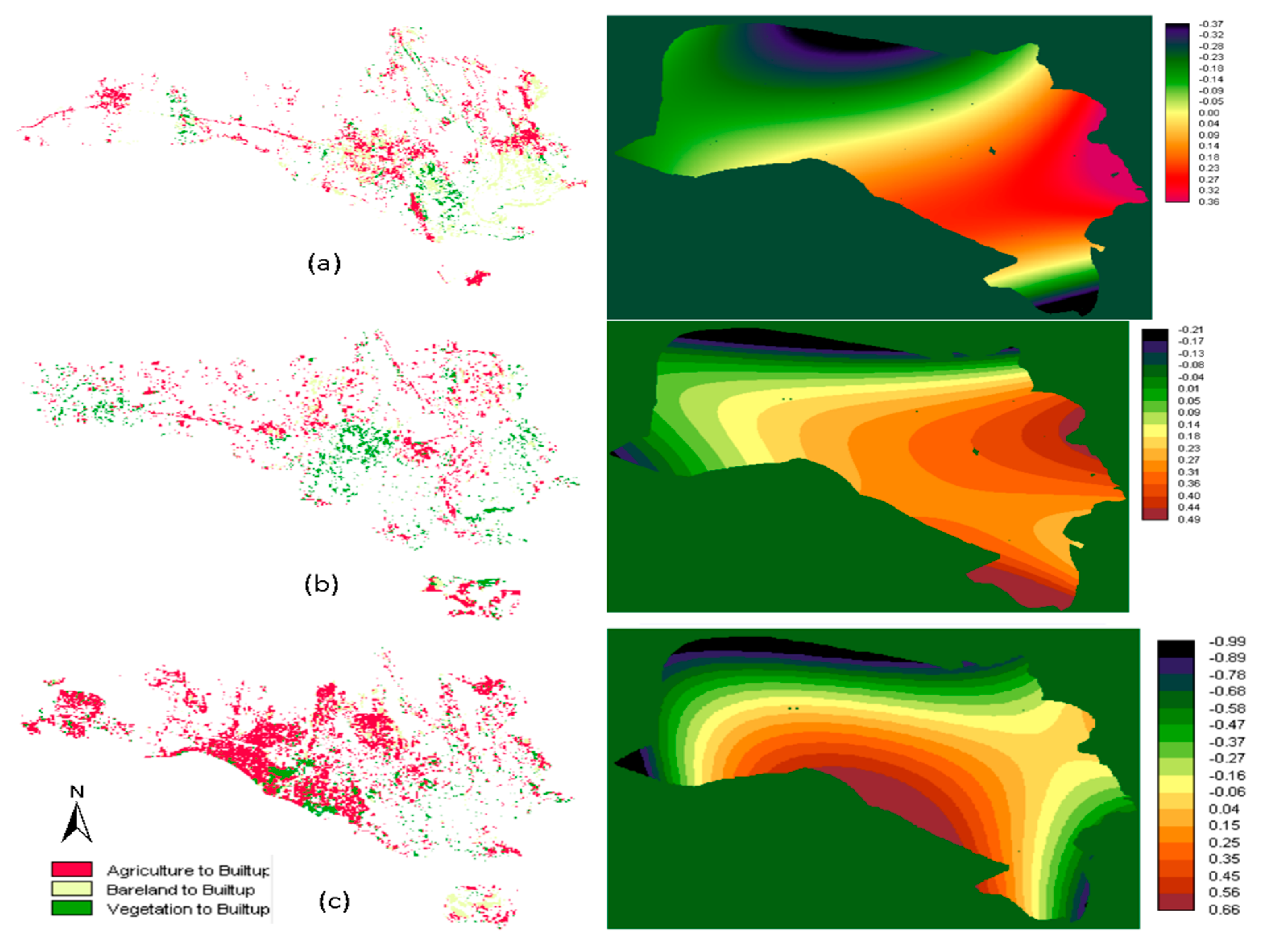

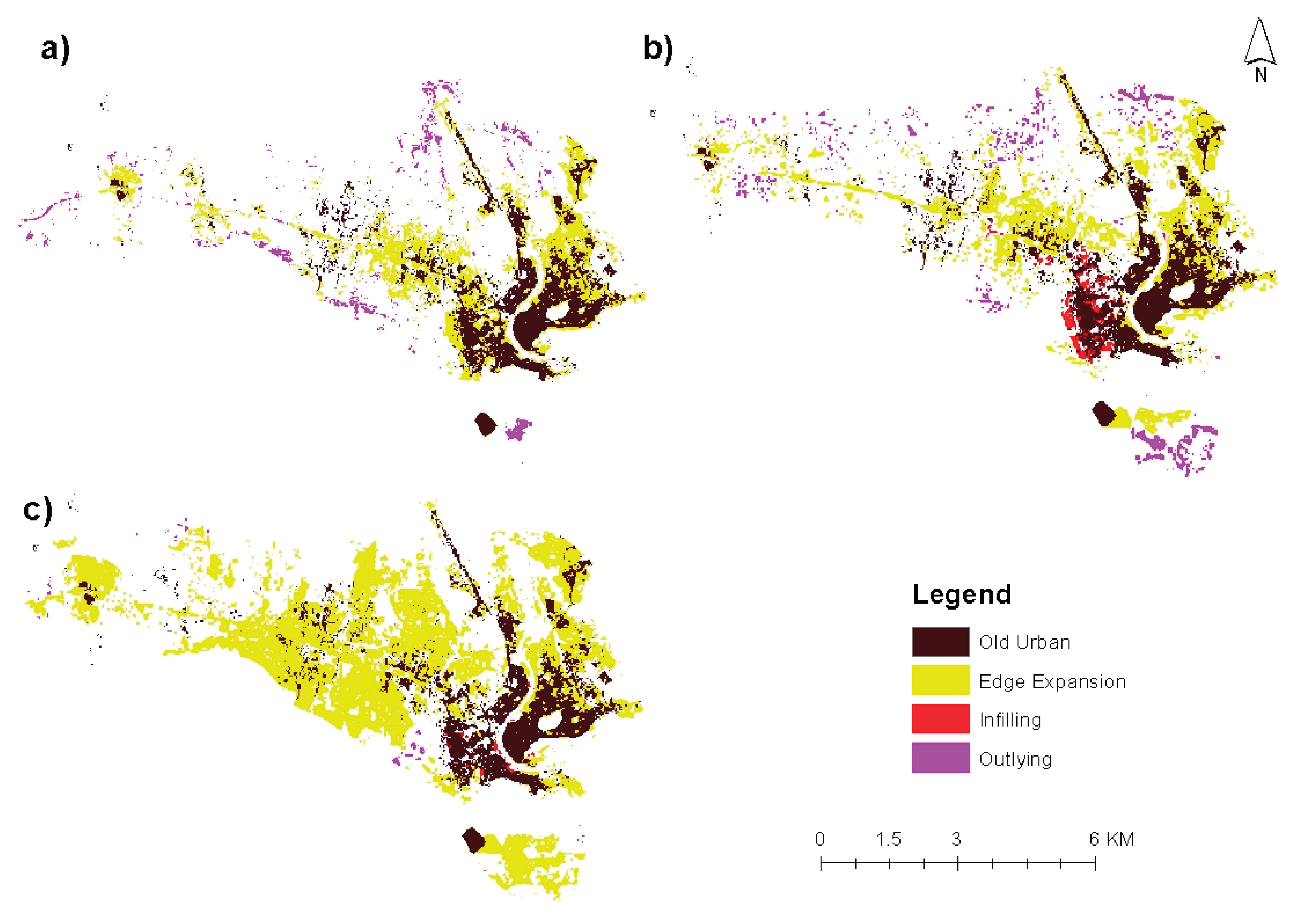

4.5. Urban Growth Pattern

4.6. Prediction of Urban Expansion for Dire Dawa City

| LULC Class | Predicted for 2023 (KM2) |

Predicted for 2043 (KM2) |

Predicted for 2063 (KM2) |

| Agriculture | 32.9328 | 30.6153 | 21.2031 |

| Bare Land | 3.1437 | 3.1716 | 3.2013 |

| Buit-up | 21.5640 | 25.0389 | 38.9844 |

| Vegetation | 15.8985 | 14.7267 | 10.1637 |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Avtar, R.; Tripathi, S.; Aggarwal, A.K.; Kumar, P. Population–Urbanization–Energy Nexus: A Review. Resources 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C. Urbanization: Processes and Driving Forces. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2019, 62, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneralp, B.; Zhou, Y.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Gupta, M.; Yu, S.; Patel, P.L.; Fragkias, M.; Li, X.; Seto, K.C. Global Scenarios of Urban Density and Its Impacts on Building Energy Use through 2050. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, 8945–8950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukanya, R.; Tantia, V. Urbanization and the Impact on Economic Development. In New perspectives and possibilities in strategic management in the 21st century: Between tradition and modernity; IGI Global, 2023; pp. 369–408.

- Anees, M.; Yan, W. An Overview about the Challenges of Urban Expansion on Environmental Health in Pakistan. J. Energy Environ. Policy Options 2019, 2, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Arfanuzzaman, M.; Dahiya, B. Sustainable Urbanization in Southeast Asia and beyond: Challenges of Population Growth, Land Use Change, and Environmental Health. Growth Change 2019, 50, 725–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuah, K.G.B.; Abdulai, R.T. Urban Land and Development Management in a Challenged Developing World: An Overview of New Reflections. Land 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifat, S.A.A.; Liu, W. Quantifying Spatiotemporal Patterns and Major Explanatory Factors of Urban Expansion in Miami Metropolitan Area During 1992–2016. Remote Sens. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Feng, Y.; Tong, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhai, S. Impacts of Spatial Scale on the Delineation of Spatiotemporal Urban Expansion. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Li, Z.; Wang, S. The Varying Driving Forces of Urban Land Expansion in China: Insights from a Spatial-Temporal Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 766, 142591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Xie, P.; Rao, Y.; He, Q. Revisiting Spatiotemporal Changes in Global Urban Expansion during 1995 to 2015. Complexity 2020, 2020, 6139158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Ou, J.; Niu, N.; Jin, Y.; Shi, H. Will the Development of a High-Speed Railway Have Impacts on Land Use Patterns in China? Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2019, 109, 979–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekuriaw, T.; Gokcekus, H. The Impact of Urban Expansion on Physical Environment in Debre Markos Town, Ethiopia. Civ Env. Res 2019, 11, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A.; Worku, H.; Lika, T. Urban and Regional Planning Approaches for Sustainable Governance: The Case of Addis Ababa and the Surrounding Area Changing Landscape. City Environ. Interact. 2020, 8, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchelo, R.O.; Bishop, T.F.A.; Ugbaje, S.U.; Akpa, S.I.C. Patterns of Urban Sprawl and Agricultural Land Loss in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Cases of the Ugandan Cities of Kampala and Mbarara. Land 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, D.; Gashu, K.; Shiferaw, G.T. Effects of Agricultural Land and Urban Expansion on Peri-Urban Forest Degradation and Implications on Sustainable Environmental Management in Southern Ethiopia. Sustainability 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, G.M.; Kombe, W. Sprawling Cities, Shrinking Farmland: Urban Expansion and Smallholder Farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2025, 17, 154–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroso, N.H.; Zevenbergen, J.A.; Lengoiboni, M. Urban Land Use Efficiency in Ethiopia: An Assessment of Urban Land Use Sustainability in Addis Ababa. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, K.H.; Iguala, A.D.; Gelete, T.B. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Urban Expansion and Its Impact on Farmlands in the Central Ethiopia Metropolitan Area. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, M.W.; Abebe, B.G.; Bantider, A. Physical and Socioeconomic Driving Forces of Land Use and Land Cover Changes: The Case of Hawassa City, Ethiopia. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1203529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, M.W.; Abebe, B.G. Quantification of Land Use/Land Cover Dynamics and Urban Growth in Rapidly Urbanized Countries: The Case Hawassa City, Ethiopia. Urban Plan. Transp. Res. 2023, 11, 2281989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adigeh, D.T.; Abebe, B.G. The Practice of Peri-Urban Land Acquisition by Expropriation for Housing Purposes and the Implications: The Case of Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Urban Sci. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitawok, M.B.; Derudder, B.; Minale, A.S.; Van Passel, S.; Adgo, E.; Nyssen, J. Modeling the Impact of Urbanization on Land-Use Change in Bahir Dar City, Ethiopia: An Integrated Cellular Automata–Markov Chain Approach. Land 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wubie, A.M.; de Vries, W.T.; Alemie, B.K. A Socio-Spatial Analysis of Land Use Dynamics and Process of Land Intervention in the Peri-Urban Areas of Bahir Dar City. Land 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Tian, Y.; Tian, J.; Yuan, C.; Cao, Y.; Liu, K. Research Progress in Spatiotemporal Dynamic Simulation of LUCC. Sustainability 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, V. The Return of the City-Region in the New Urban Agenda: Is This Relevant in the Global South? In Planning Regional Futures; Routledge, 2021; pp. 34–52.

- Broadberry, S.; Wallis, J.J. Growing, Shrinking, and Long-Run Economic Performance: Historical Perspectives on Economic Development. J. Econ. Hist. 2025, 85, 505–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, P.; Yue, W.; Song, Y. Impacts of Land Finance on Urban Sprawl in China: The Case of Chongqing. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, M.; Rodrik, D.; Verduzco-Gallo, Í. Globalization, Structural Change, and Productivity Growth, with an Update on Africa. Econ. Transform. Afr. 2014, 63, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, K.C.; Fragkias, M.; Güneralp, B.; Reilly, M.K. A Meta-Analysis of Global Urban Land Expansion. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e23777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dritsas, E.; Trigka, M. Remote Sensing and Geospatial Analysis in the Big Data Era: A Survey. Remote Sens. 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs-Györi, A.; Ristea, A.; Havas, C.; Mehaffy, M.; Hochmair, H.H.; Resch, B.; Juhasz, L.; Lehner, A.; Ramasubramanian, L.; Blaschke, T. Opportunities and Challenges of Geospatial Analysis for Promoting Urban Livability in the Era of Big Data and Machine Learning. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adzandeh, E.A.; Alaigba, D.; Nkemasong, C.N. Application of Geospatial Techniques and Logistic Regression Model for Urban Growth Analysis in Limbe, Cameroon. Niger J Env. Sci TechnolNIJEST 2020, 4, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Huang, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, Z. Parametric Design of Ecological Park Landscape with DLA-GIS and GANs-GIS Based on Remote Sensing Data. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Telecommunications, Optics, and Computer Science (TOCS 2024); Pedrycz, W., Agaian, S.S., Eds.; SPIE, 2025; Vol. 13629, p. 1362902.

- Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, K.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, D. Artificial Neural Network Modelling in GIS Spatial Analysis. Acad. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 7, 1809–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, M.; Oshnooei-Nooshabadi, A.; Saleh, S.-S.; Habibnezhad, F.; Sarafraz-Asbagh, S.; Van Genderen, J.L. Urban Sprawl Simulation Mapping of Urmia (Iran) by Comparison of Cellular Automata–Markov Chain and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Modeling Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzakhani, A.; Behzadfar, M.; Azizi Habashi, S. Simulating Urban Expansion Dynamics in Tehran through Satellite Imagery and Cellular Automata Markov Chain Modelling. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 11, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, N.N.; Al Rakib, A.; Kafy, A.-A.; Raikwar, V. Geospatial Modelling of Changes in Land Use/Land Cover Dynamics Using Multi-Layer Perceptron Markov Chain Model in Rajshahi City, Bangladesh. Environ. Chall. 2021, 4, 100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hameedi, W.M.M.; Chen, J.; Faichia, C.; Al-Shaibah, B.; Nath, B.; Kafy, A.-A.; Hu, G.; Al-Aizari, A. Remote Sensing-Based Urban Sprawl Modeling Using Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network Markov Chain in Baghdad, Iraq. Remote Sens. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivappa Masalvad, S.; Patil, C.; Pravalika, A.; Katageri, B.; Bekal, P.; Patil, P.; Hegde, N.; Sahoo, U.K.; Sakare, P.K. Application of Geospatial Technology for the Land Use/Land Cover Change Assessment and Future Change Predictions Using CA Markov Chain Model. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 24817–24842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S.; Ghoneim, E.; El-Kersh, A.; Said, S.; Abdelnaby, S. Spatiotemporal Monitoring of Urban Sprawl in a Coastal City Using GIS-Based Markov Chain and Artificial Neural Network (ANN). Remote Sens. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, W.; Elias, E.; Warkineh, B.; Tekalign, M.; Abebe, G. Modeling of Land Use and Land Cover Changes Using Google Earth Engine and Machine Learning Approach: Implications for Landscape Management. Environ. Syst. Res. 2024, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabisa, M.; Kabite, G.; Mammo, S. Land Use and Land Cover Change Trends, Drivers and Its Impacts on Ecosystem Services in Burayu Sub City, Ethiopia. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1557000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, A.; Keesstra, S.D.; Stroosnijder, L. A New Agro-Climatic Classification for Crop Suitability Zoning in Northern Semi-Arid Ethiopia. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2010, 150, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, M. Heritage-Tourism Resources of the Franco-Ethiopian Railway in Dire Dawa, Ethiopia. Afr J Hosp Tour Leis 2018, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Dustdar, S.; Ranjan, R.; Morgan, G.; Dong, Y.; Wang, L. Remote Sensing Image Interpretation With Semantic Graph-Based Methods: A Survey. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 4544–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Fu, K. Research Progress on Few-Shot Learning for Remote Sensing Image Interpretation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 2387–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.A.; Abdel-Rahman, E.M.; Onono, J.O.; Olaka, L.A.; Elhag, M.M.; Adan, M.; Tonnang, H.E. Mapping, Intensities and Future Prediction of Land Use/Land Cover Dynamics Using Google Earth Engine and CA-Artificial Neural Network Model. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0288694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroonsri, I. Comparative Analysis of Land Use Classification Accuracy Using Maximum Likelihood Classification (MLC) and Spectral Angle Mapping (SAM) Methods. Int. J. Adv. Res. Comput. Sci. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengist, W. An Overview of the Major Vegetation Classification in Africa and the New Vegetation Classification in Ethiopia. Am. J. Zool. 2019, 2, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mfitumukiza, D.; Kayendeke, E.; Mwanjalolo, J.G.M. Classification and Mapping of Rangeland Vegetation Physiognomic Composition Using Landsat Enhanced Thematic Mapper and IKONOS Imagery. South Afr. J. Geomat. 2014, 3, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Breugel, P.; Kindt, R.; Lillesø, J.P.B.; Bingham, M.; Dudley, C.; Friis, I.; Gachathi, F.; Kalema, J.; Mbago, F.; Minani, V. Potential Natural Vegetation of Eastern Africa (Ethiopia, Kenya, Ma; Forest & Landscape Denmark University of Copenhagen 23 Rolighedsvej DK-1958 …, 2011; ISBN 87-7903-562-0.

- Sharma, R.; Garg, P.K.; Dwivedi, R.K. Analysis of Uncertainty Ratio in Classified Imagery Using Independent Indicator Entropy. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2020, 23, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A.H.; Abbasi, H.; Karas, I.R. A Review on Change Detection Method and Accuracy Assessment for Land Use Land Cover. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2021, 22, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhuang, Q.; Meng, X.; Guo, H.; Han, J. An Improved Nightlight Threshold Method for Revealing the Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Driving Forces of Urban Expansion in China. J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 289, 112574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jia, Y.; Li, X.; Gong, P. Analysing the Driving Forces and Environmental Effects of Urban Expansion by Mapping the Speed and Acceleration of Built-Up Areas in China between 1978 and 2017. Remote Sens. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Sumari, N.S.; Dong, T.; Xu, G.; Liu, Y. Characterizing Urban Expansion Combining Concentric-Ring and Grid-Based Analysis for Latin American Cities. Land 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, W.; Li, M.; Yu, Q.; Wang, Y. Identifying the Effects of Industrial Land Expansion on PM2.5 Concentrations: A Spatiotemporal Analysis in China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 141, 109069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; He, F.; Si, Y. Spatial Effects of Railway Network Construction on Urban Sprawl and Its Mechanisms: Evidence from Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration, China. Land 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, J.; Chen, Z.; Huang, J. Predicting Urban Expansion to Assess the Change of Landscape Character Types and Its Driving Factors in the Mountain City. Land 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, W.; Li, M.; Yu, Q.; Wang, Y. Identifying the Effects of Industrial Land Expansion on PM2.5 Concentrations: A Spatiotemporal Analysis in China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 141, 109069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, S. Urban Expansion: Theory, Evidence and Practice. Build. Cities 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, E.; Banos, A.; Abrantes, P.; Rocha, J. Assessing the Effect of Spatial Proximity on Urban Growth. Sustainability 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejrananda, C. From Runway to Cityscape: Challenges of Airport-Driven Urban Growth. Int. J. Build. Urban Inter. Landsc. Technol. BUILT 2024, 22, 256538–256538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getaneh, Z.A.; Demissew, S.; Woldu, Z. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Land Use Land Cover Change and Its Drivers in the Western Part of Lake Abaya, Ethiopia. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoshnood Motlagh, S.; Sadoddin, A.; Haghnegahdar, A.; Razavi, S.; Salmanmahiny, A.; Ghorbani, K. Analysis and Prediction of Land Cover Changes Using the Land Change Modeler (LCM) in a Semiarid River Basin, Iran. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 3092–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salarin, F.; TATIAN, M.; Ghanghermeh, A.; Tamartash, R. Modeling Land Cover Changes in Golestan Province Using Land Change Modeler (LCM). 2022.

- Tian, Y.; Shuai, Y.; Ma, X.; Shao, C.; Liu, T.; Tuerhanjiang, L. Improved Landscape Expansion Index and Its Application to Urban Growth in Urumqi. Remote Sens. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldesemayat, E.M.; Genovese, P.V. Monitoring Urban Expansion and Urban Green Spaces Change in Addis Ababa: Directional and Zonal Analysis Integrated with Landscape Expansion Index. Forests 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Tang, W.; Gong, J.; Shi, R.; Zheng, M.; Dai, Y. Simulating Urban Expansion Using Cellular Automata Model with Spatiotemporally Explicit Representation of Urban Demand. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 231, 104640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baqa, M.F.; Chen, F.; Lu, L.; Qureshi, S.; Tariq, A.; Wang, S.; Jing, L.; Hamza, S.; Li, Q. Monitoring and Modeling the Patterns and Trends of Urban Growth Using Urban Sprawl Matrix and CA-Markov Model: A Case Study of Karachi, Pakistan. Land 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.W.; Gebru, B.M.; Lamchin, M.; Kayastha, R.B.; Lee, W.-K. Land Use and Land Cover Change Detection and Prediction in the Kathmandu District of Nepal Using Remote Sensing and GIS. Sustainability 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, S.; Singha, P.; Mahato, S.; Shahfahad; Pal, S.; Liou, Y.-A.; Rahman, A. Land-Use Land-Cover Classification by Machine Learning Classifiers for Satellite Observations—A Review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Raghubanshi, A.; Srivastava, P.K.; Raghubanshi, A.S. Appraisal of Kappa-Based Metrics and Disagreement Indices of Accuracy Assessment for Parametric and Nonparametric Techniques Used in LULC Classification and Change Detection. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2020, 6, 1045–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeni, A.O.; Aborisade, A.G.; Aiyegbajeje, F.O.; Soneye, A.S.O. The Dynamics of Peri-Urban Expansion in Sub-Saharan Africa: Implications for Sustainable Development in Nigeria and Ghana. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daba, M.H.; You, S. Quantitatively Assessing the Future Land-Use/Land-Cover Changes and Their Driving Factors in the Upper Stream of the Awash River Based on the CA–Markov Model and Their Implications for Water Resources Management. Sustainability 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitawok, M.B.; Derudder, B.; Minale, A.S.; Van Passel, S.; Adgo, E.; Nyssen, J. Analyzing the Impact of Land Expropriation Program on Farmers’ Livelihood in Urban Fringes of Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Habitat Int. 2022, 129, 102674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Jia, H. Simulating the Spatial Dynamics of Urban Growth with an Integrated Modeling Approach: A Case Study of Foshan, China. Spec. Issue China-Korea Jt. Semin. Multi-Discip. Multi-Method Approaches Sustain. Hum. Nat. Interact. 2017, 353, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vani, M.; Prasad, P.R.C. Modelling Urban Expansion of a South-East Asian City, India: Comparison between SLEUTH and a Hybrid CA Model. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2022, 8, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terfa, B.K.; Chen, N.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Niyogi, D. Urban Expansion in Ethiopia from 1987 to 2017: Characteristics, Spatial Patterns, and Driving Forces. Sustainability 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahfahad; Talukdar, S.; Naikoo, M.W.; Rahman, A. Urban Expansion and Vegetation Dynamics: The Role of Protected Areas in Preventing Vegetation Loss in a Growing Mega City. Habitat Int. 2024, 150, 103129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Sun, W.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, L. Impact of Urban Expansion on Vegetation: The Case of China (2000–2018). J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 291, 112598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.; Worku, H. Simulating Urban Land Use and Cover Dynamics Using Cellular Automata and Markov Chain Approach in Addis Ababa and the Surrounding. Urban Clim. 2020, 31, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Ma, L.; Liu, Y. Comparing the Driving Mechanisms of Different Types of Urban Construction Land Expansion: A Case Study of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region. J. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 722–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, B.; Zhang, L.; Stork, N.; Sloan, S.; Rijal, S. Urban Expansion Occurred at the Expense of Agricultural Lands in the Tarai Region of Nepal from 1989 to 2016. Sustainability 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zou, Y.; Xia, C.; Lu, Y. Unraveling the Mystery of Urban Expansion in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area: Exploring the Crucial Role of Regional Cooperation. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2025, 52, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Source | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Landsat 5 (TM), 1993 | USGS Earth Explorer | Preparation of LULC maps for the study area for 1993, 2003, 2013 and 2023 |

| Landsat 7 (ETM+), 2003 | USGS Earth Explorer | |

| Landsat 8 OLI, (2013) | USGS Earth Explorer | |

| Landsat 9 OLI, (2023) | USGS Earth Explorer | |

| Aerial photograph (1993,2003,2013) and Google Earth | Ethiopian Geospatial Information Institute (EGII) | For validation of classified LULC |

| ASTER (DEM) | Earthdata | Preparation of Elevation and Slope maps |

| Road | OpenStreetMap | Preparation of Road maps |

| Railway | OpenStreetMap | Preparation of Railway maps |

| Point Location of (Public Institution, industries, Factories and Airport) | Google Earth & Field Survey | Preparation of Euclidean distance maps |

| LULC Class | Description |

| Agriculture | Areas dedicated to agricultural production include cultivated fields, grazing lands, fruit orchards, and livestock confinement facilities. This includes both actively farmed land and fallow fields |

| Bare land | Areas with minimal vegetation primarily contain exposed earth materials such as stone, gravel, sand, silt, and clay. Examples include sandy areas, barely exposed rocks, and quarries and dry-up rivers |

| Built-up | Areas of high-density usage where structures dominate the landscape include urban centers, rural settlements, roadside developments, infrastructure for transportation and utilities, industrial and commercial zones, and institutional facilities |

| Vegetation | Areas characterized by natural or partially natural vegetation, such as urban forests, areas dominated by shrubs, and grasslands |

| LULC Class | Accuracy (%) | |||||||

| 1993 | 2003 | 2013 | 2023 | |||||

| Producer’s | User’s | Producer’s | User’s | Producer’s | User’s | Producer’s | User’s | |

| Agriculture | 92.96% | 90.41% | 96.05% | 93.59% | 94.94% | 92.59% | 89.06% | 90.48% |

| Bare land | 92.86% | 81.25% | 70.00% | 87.50% | 83.33% | 83.33% | 92.31% | 85.71% |

| Built-up | 78.57% | 91.67% | 84.21% | 88.89% | 80.77% | 84.00% | 83.33% | 92.59% |

| Vegetation | 75.00% | 93.75% | 84.62% | 81.48% | 78.95% | 83.33% | 84.21% | 72.73% |

| Overall Accuracy | 88.72% | 90.08% | 89.23% | 87.30% | ||||

| Kappa Coefficient | 0.8206 | 0.8315 | 0.8079 | 0.8068 | ||||

| Given | Probability of Change | |||

| Agriculture | Bare land | Built-up | Vegetation | |

| Agriculture | 0.3785 | 0.0238 | 0.4553 | 0.1424 |

| Bare land | 0.4262 | 0.0556 | 0.2606 | 0.2576 |

| Built-up | 0.0095 | 0.0290 | 0.9539 | 0.0076 |

| Vegetation | 0.2658 | 0.0366 | 0.2000 | 0.4976 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).