Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

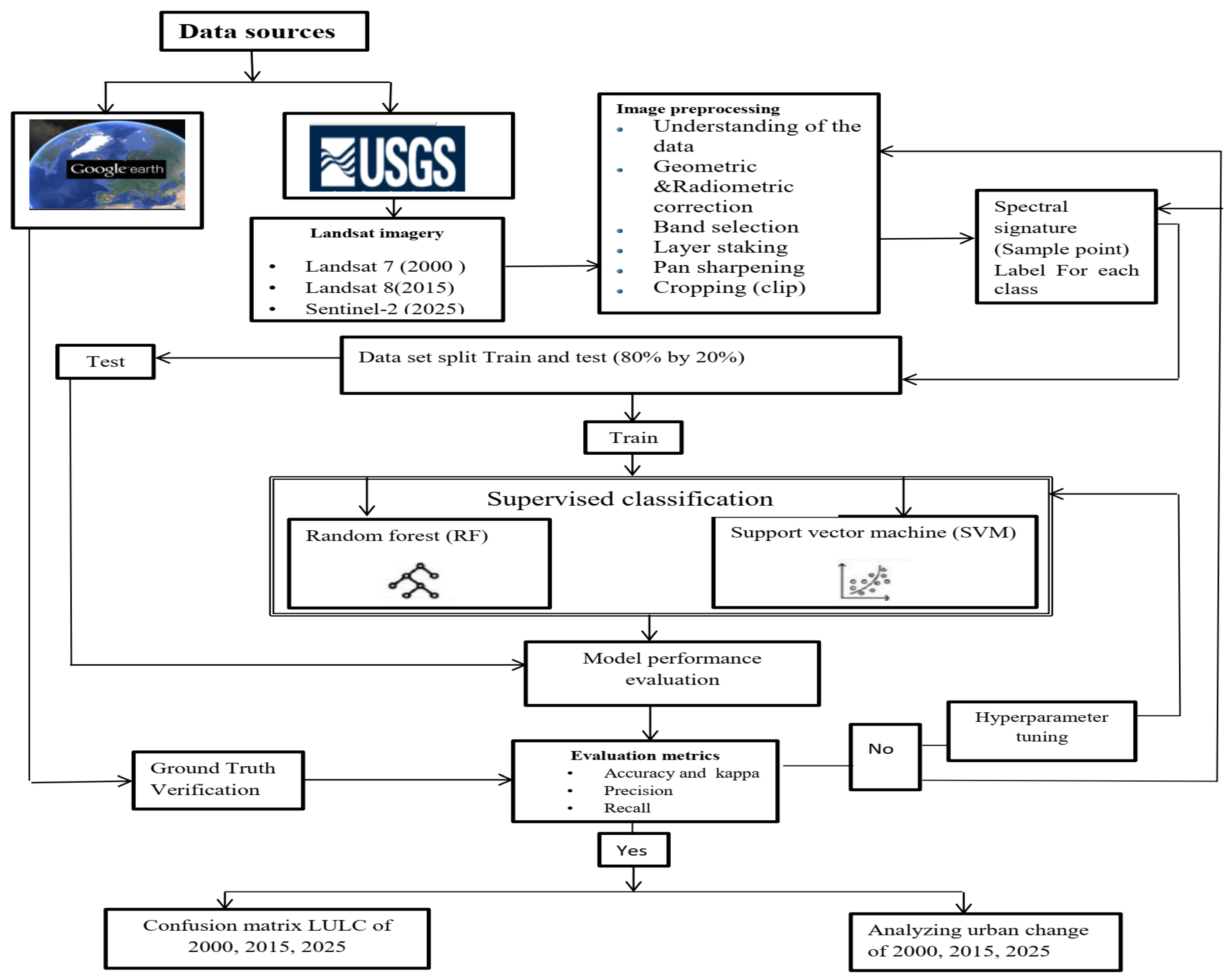

2. Materials and Methods

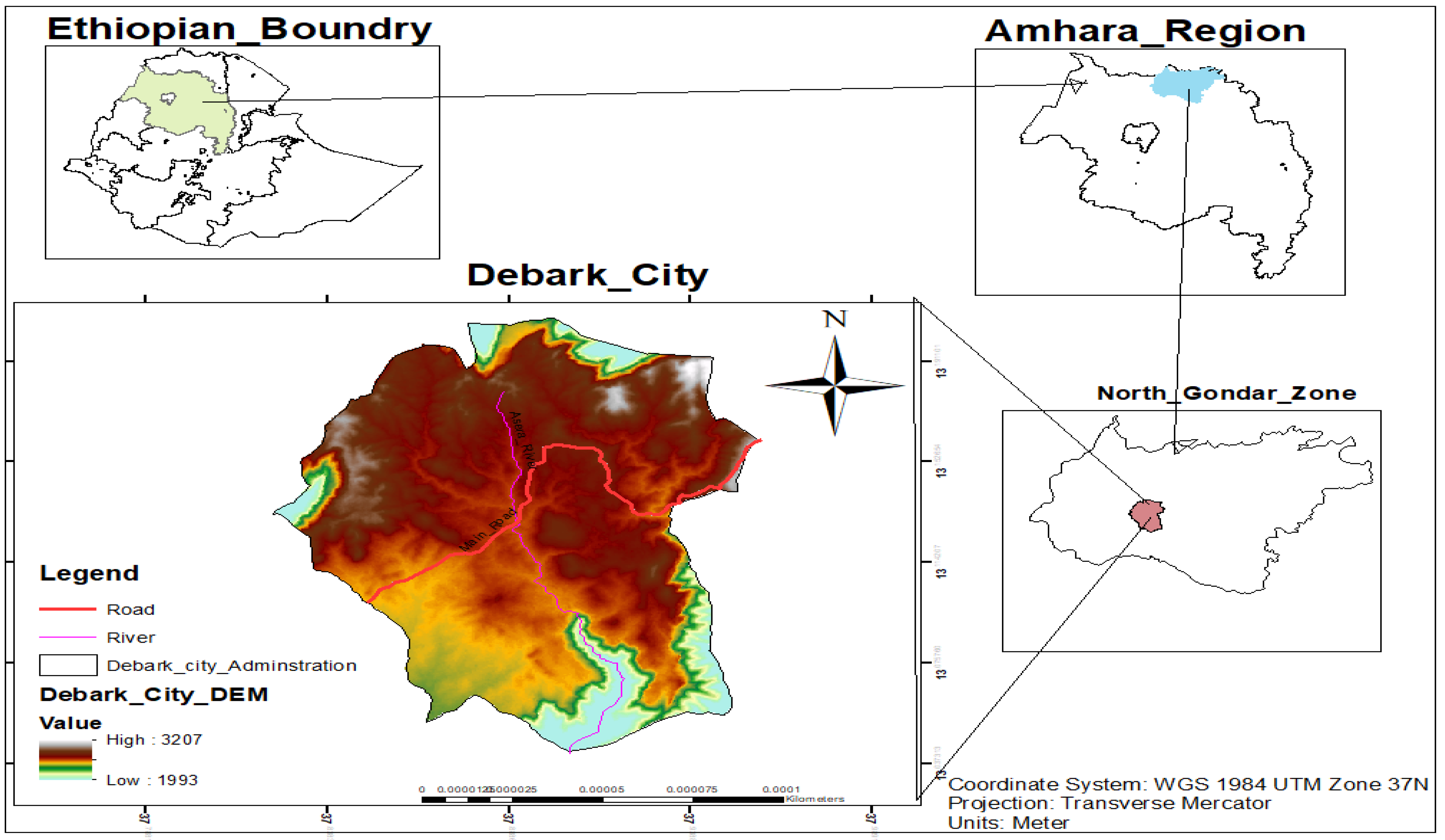

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Dataset

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Data Preprocessing

2.3.2. Train and Testing Split

2.3.3. Implementing the ML Algorithm

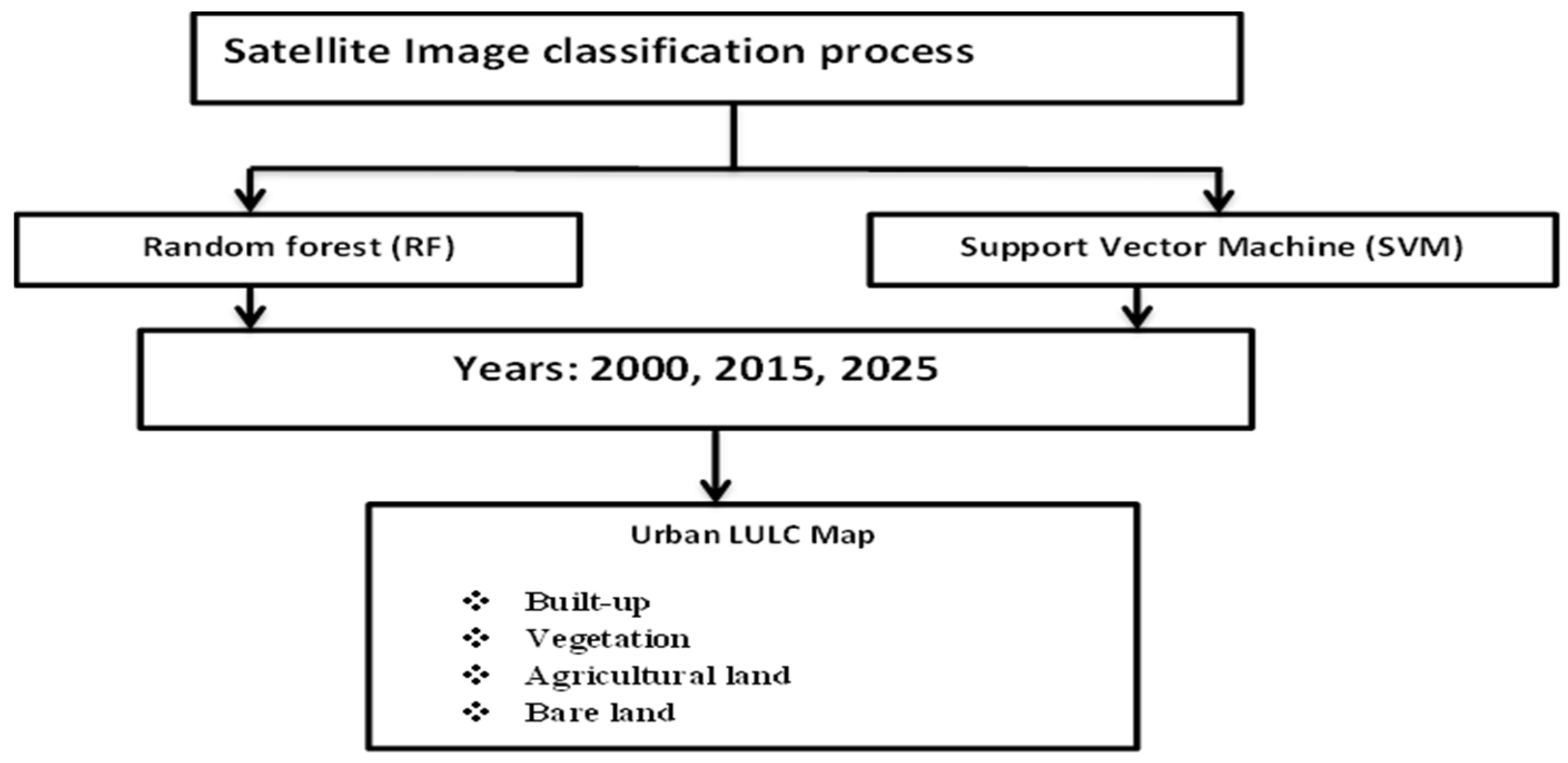

2.3.4. Image Classification

2.3.5. Accuracy Assessment

- ❖

- Overall Accuracy (OA): is the number of pixel correctly classified by the total number of instances, indicating the extent to which the classification outcomes match the reference data (Al-Saady et al., 2015).

- ❖

- Recall: The link between true positives and the sum of true positives and false positives is another way to define PA, or recall the omission error's complement is the PA.

- ❖

- Precision: the relationship between true positives and the overall number of true positives and false negatives is another definition of the UA, or precision (Yang et al., 2025). The commission error's complement is the UA.

- ❖ Kappa coefficient: measures agreement between predicted and actual classifications while correcting for chance agreement. One of the most widely utilized accuracy indicators (Bedada et al., 2024), the accuracy of land use classification in this study, was tested using the Kappa coefficient.

2.3.6. Change Detection

- ❖

- Rate of change (RC)

3. Results

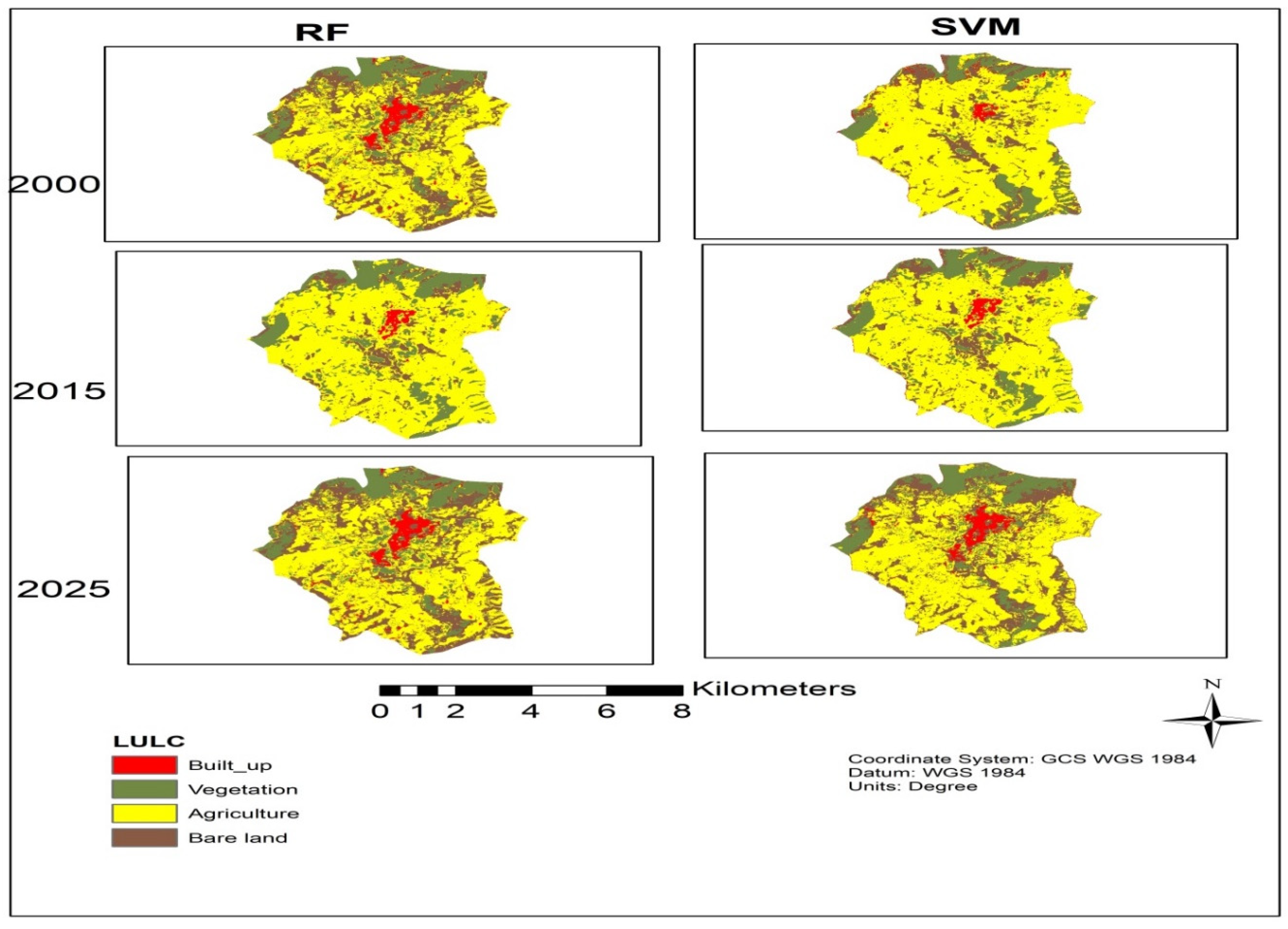

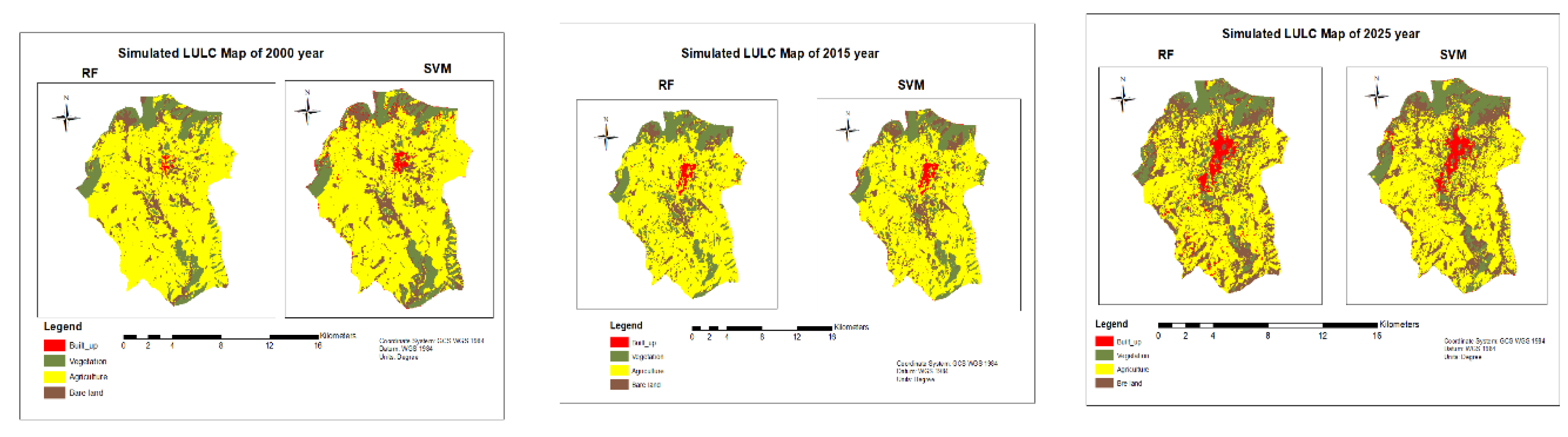

3.1. Image Classification and Accuracy Assessment

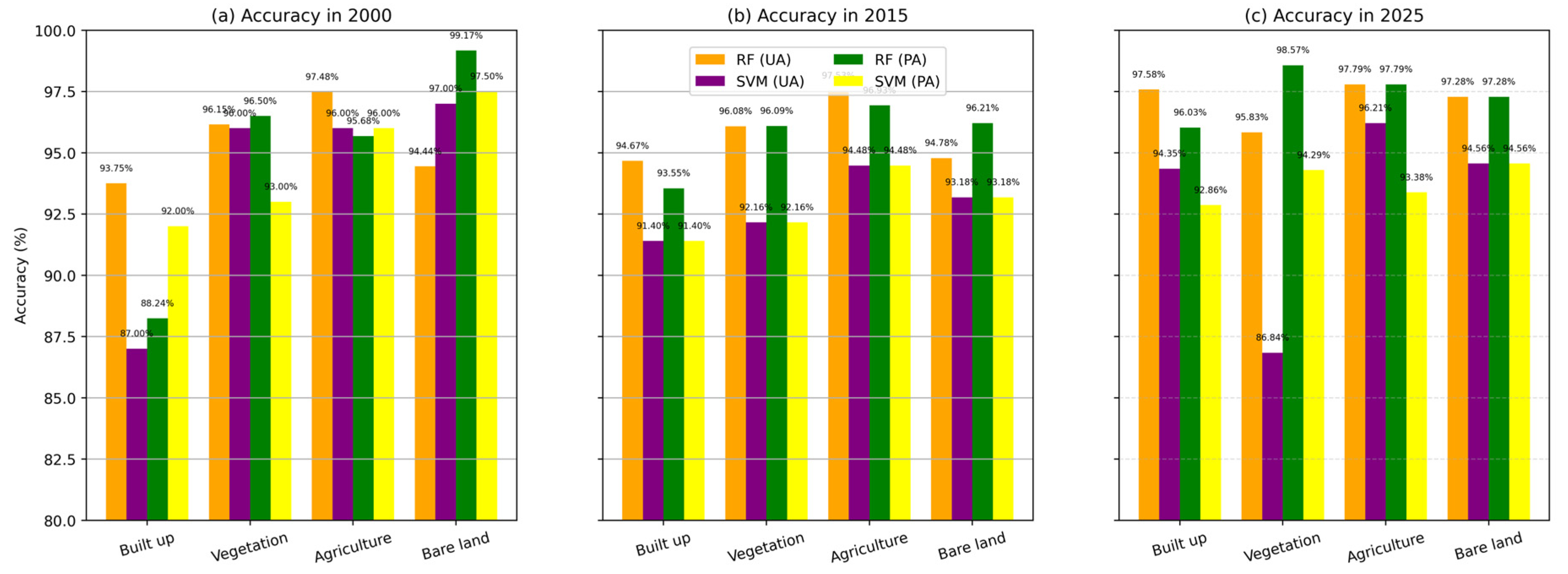

3.2. Accuracy Assessment and Comparison of Classification Models

3.3. Urban Simulation

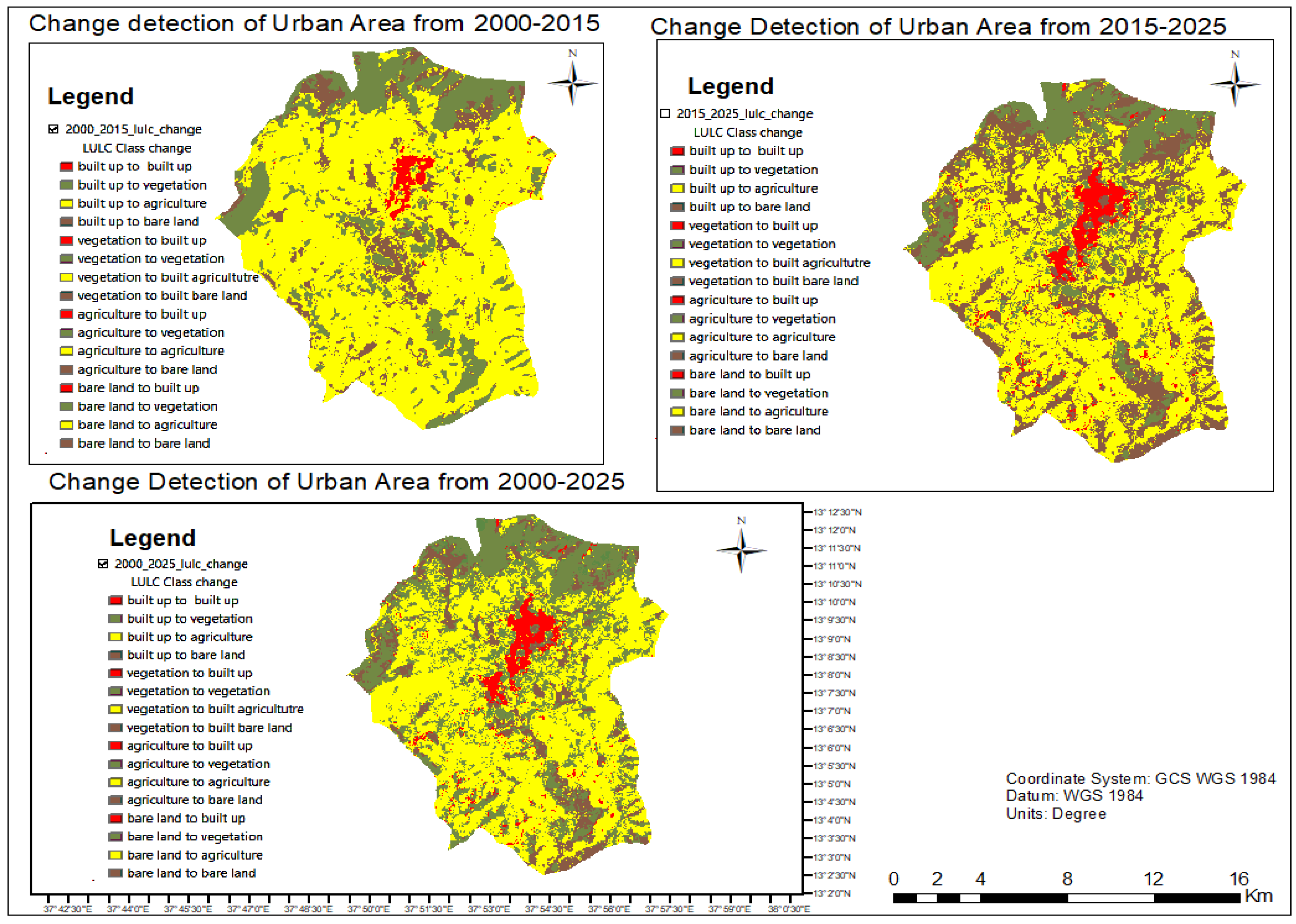

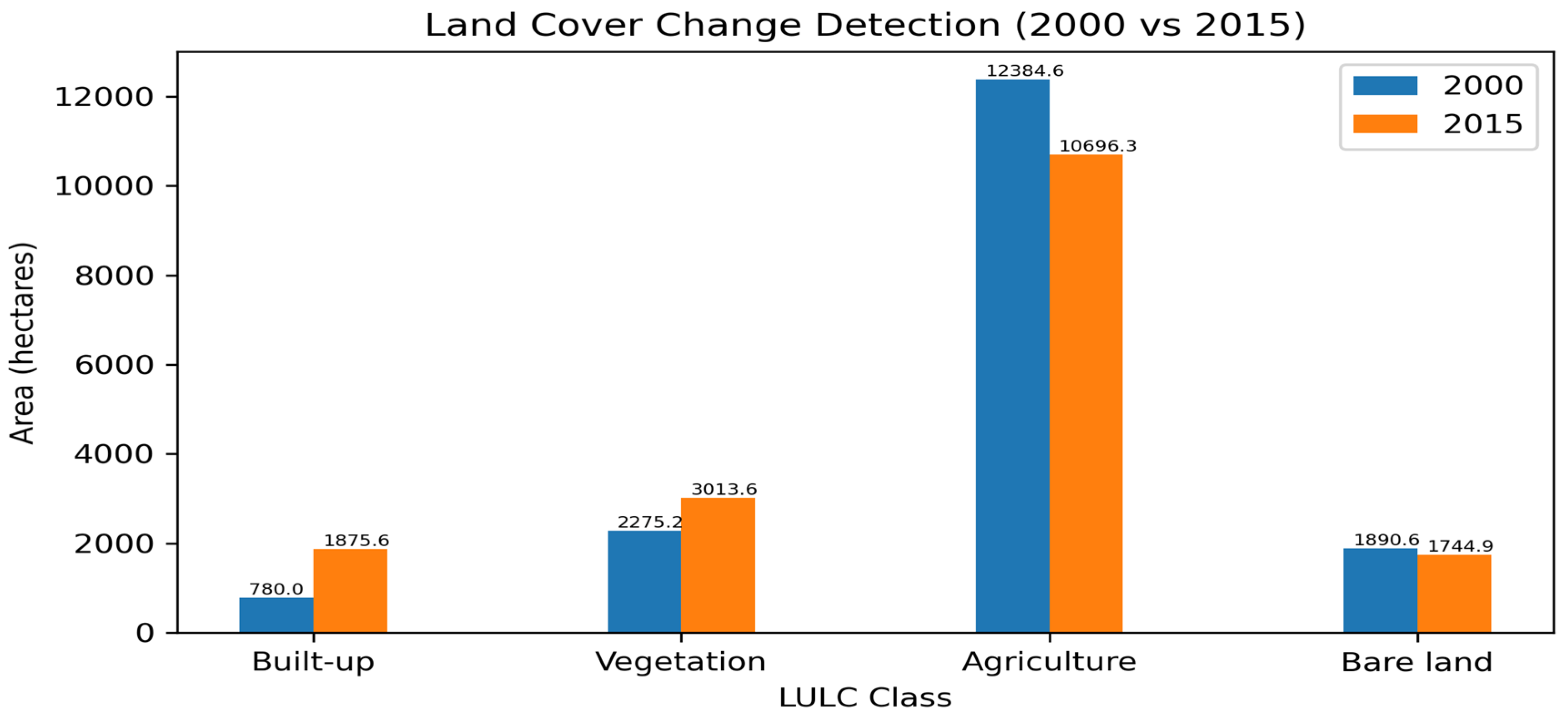

3.4. Change Detection Between 2000 and 2025

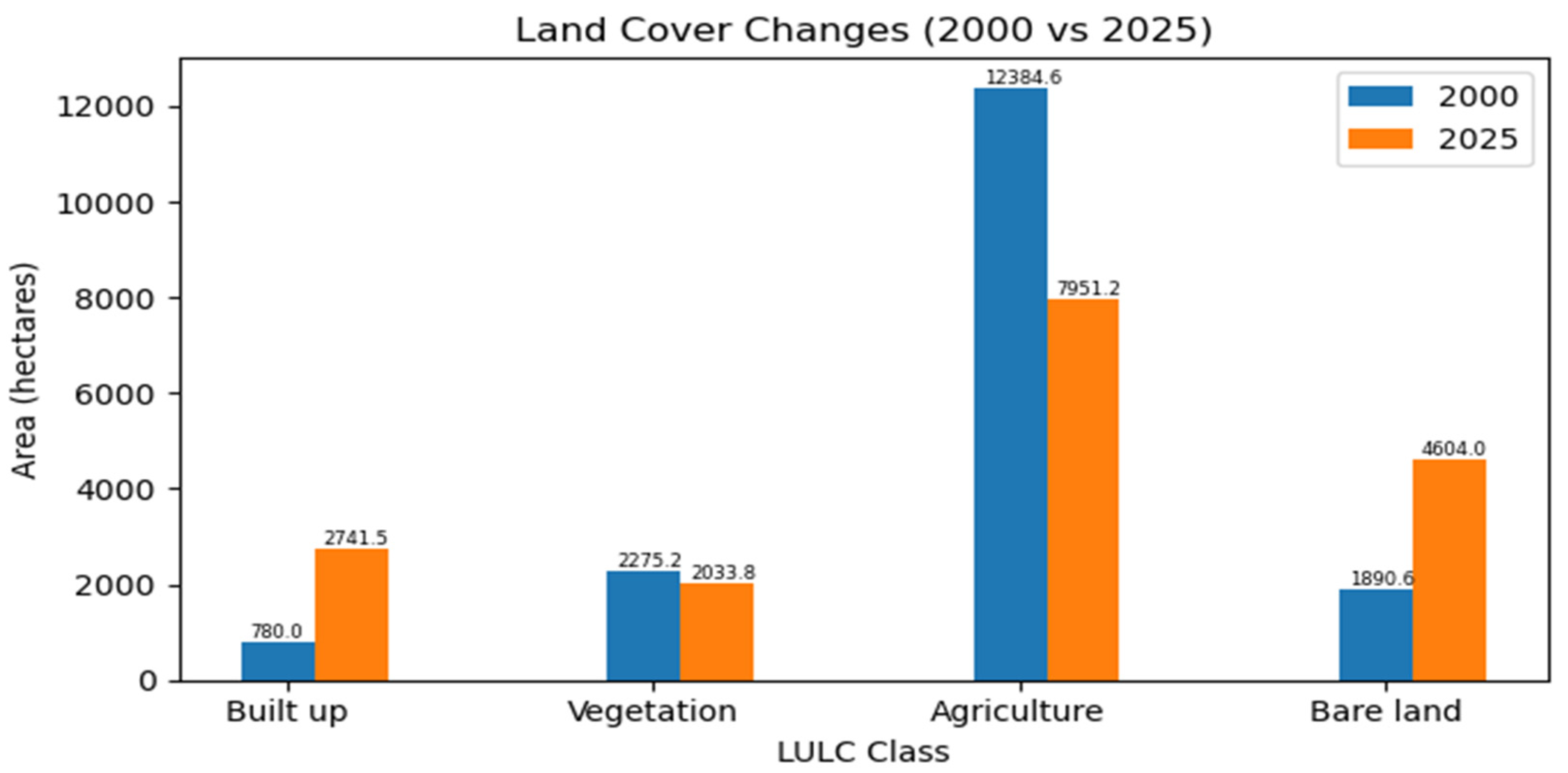

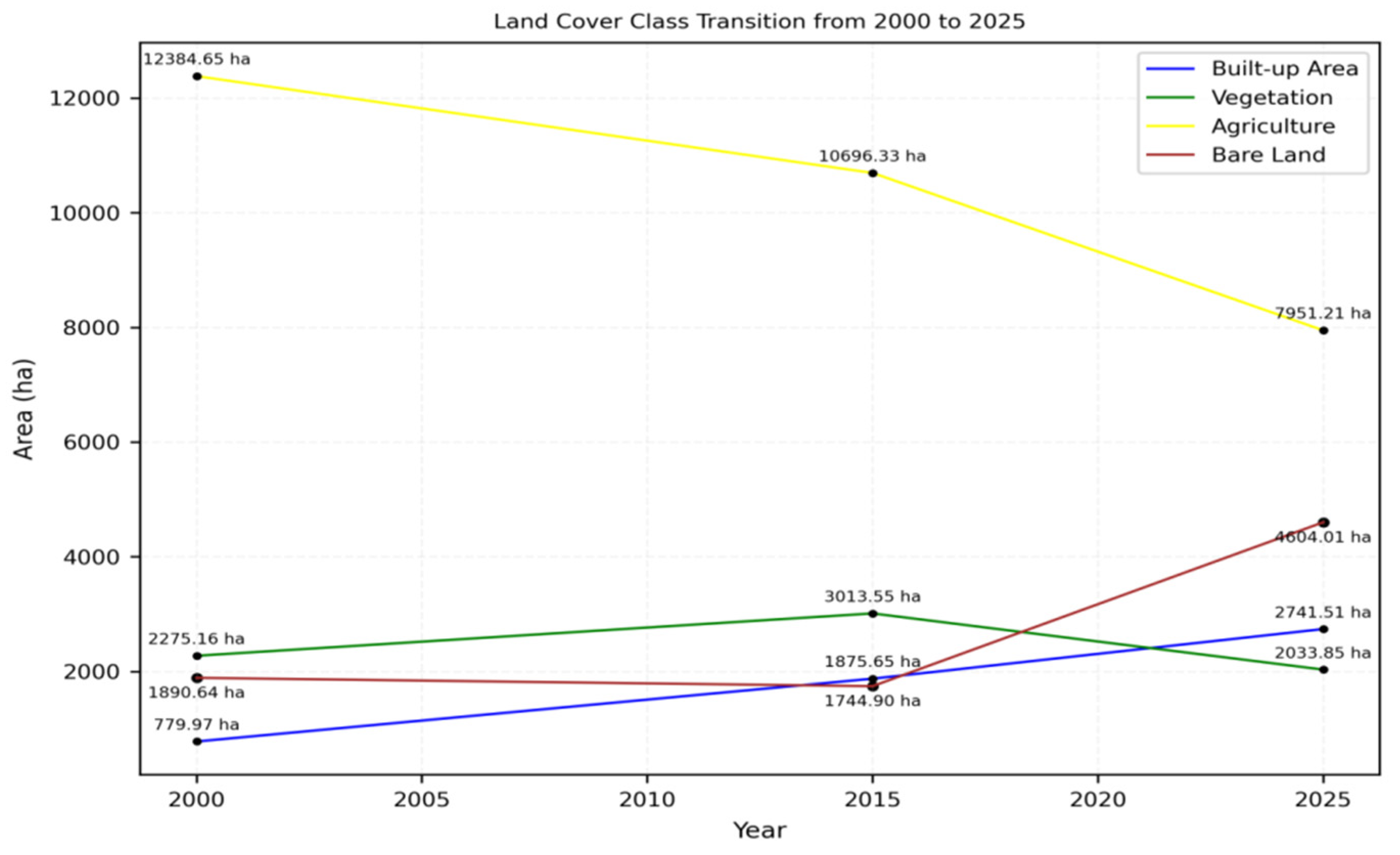

| LULC Class |

Area 2015(ha) |

Area 2015(%) | Area 2025 (ha) | 2025 Area (%) |

Change (ha) |

Change Area (%) |

| Built up | 1875.646 | 10.82% | 2741.515 | 15.82% | +865.869 | +5.0% |

| Vegetation |

3,013.55 |

17.39% | 2,033.85 | 11.74% |

−979.700 |

-5.65% |

| Agriculture |

10,696.33 |

61.69% | 7,951.21 | 45.88% |

−2,745.120 |

-15.81% |

| Bare land |

1,744.90 |

10.07% | 4,604.01 | 26.56% |

+2,859.110 |

+16.49% |

4. Discussion

4.1. Result Comparison with Other LULC Datasets

4.2. Machine Learning Model Performance Comparisons

4.3. Urban LULC Change Detection

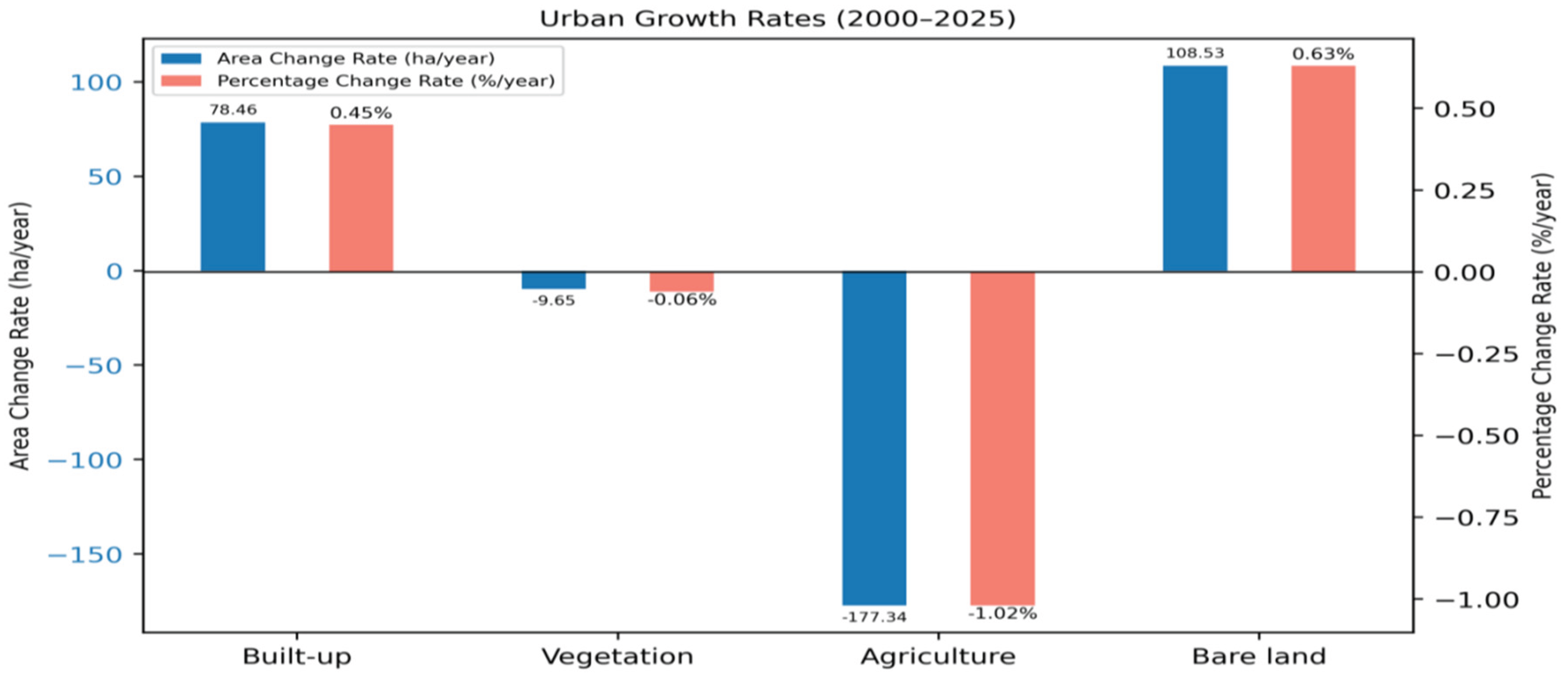

4.4. Annual Rate Change of Urban Expansion

5. Conclusion

Funding

References

- Abdi, A. M. (2020). Land cover and land use classification performance of machine learning algorithms in a boreal landscape using Sentinel-2 data. GIScience and Remote Sensing, 57(1), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Al-Saady, Y., Merkel, B., Al-Tawash, B., & Al-Suhail, Q. (2015). Land use and land cover (LULC) mapping and change detection in the Little Zab River Basin (LZRB), Kurdistan Region, NE Iraq and NW Iran. FOG - Freiberg Online Geoscience, 43, 1–32.

- Amini, S., Saber, M., Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H., & Homayouni, S. (2022). Urban Land Use and Land Cover Change Analysis Using Random Forest Classification of Landsat Time Series. Remote Sensing, 14(11), 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Atef, I., Ahmed, W., & Abdel-Maguid, R. H. (2023). Modelling of land use land cover changes using machine learning and GIS techniques: a case study in El-Fayoum Governorate, Egypt. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 195(6). [CrossRef]

- Barow, I. , Megenta, M., & Megento, T. (2019). Spatiotemporal analysis of urban expansion using GIS and remote sensing in Jigjiga town of Ethiopia. ( 11(2), 121–127. [CrossRef]

- Bedada, B. A., Engine, G. E., & Scholar, G. (2024). Urban Land Use Land Cover Dynamics and Urban Expansion Intensity Assessment Using Multi-Temporal Landsat Imageries and Google Earth Engine over Adama City , Ethiopia Urban Land Use Land Cover Dynamics and Urban. 0–19. [CrossRef]

- Belay, E. (2014). Impact of Urban Expansion on the Agricultural Land Use a Remote Sensing and GIS Approach : A Case of Gondar City , Ethiopia. International Journal of Innovative Research & Development, 3(6), 129–133.

- Chowdhury, M. S. (2024). Comparison of accuracy and reliability of random forest, support vector machine, artificial neural network and maximum likelihood method in land use/cover classification of urban setting. Environmental Challenges, 14(November 2023), 100800. [CrossRef]

- Coq-Huelva, D., & Asián-Chaves, R. (2019). Urban sprawl and sustainable urban policies. A review of the cases of Lima, Mexico City and Santiago de Chile. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(20). [CrossRef]

- D., S., Deepa, P., & K., V. (2017). Remote Sensing Satellite Image Processing Techniques for Image Classification: A Comprehensive Survey. International Journal of Computer Applications, 161(11), 24–37. [CrossRef]

- Dadras, M., Shafri, H. Z. M., Ahmad, N., Pradhan, B., & Safarpour, S. (2015). Spatio-temporal analysis of urban growth from remote sensing data in Bandar Abbas city, Iran. Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science, 18(1), 35–52. [CrossRef]

- Deribew, K. T. (2020). Spatiotemporal analysis of urban growth on forest and agricultural land using geospatial techniques and Shannon entropy method in the satellite town of Ethiopia, the western fringe of Addis Ababa city. Ecological Processes, 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Desta, S. Z., & Gugssa, M. A. (2022). The Implementation of Andragogy in the Adult Education Program in Ethiopia. Education Research International, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Dharani, M., & Sreenivasulu, G. (2021). Land use and land cover change detection by using principal component analysis and morphological operations in remote sensing applications. International Journal of Computers and Applications, 43(5), 462–471. [CrossRef]

- Dibaba, W. T. (2023). Urbanization-induced land use/land cover change and its impact on surface temperature and heat fluxes over two major cities in Western Ethiopia. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 195(9). [CrossRef]

- Durowoju, O. S., Obateru, R. O., Adelabu, S., & Olusola, A. (2025). Urban change detection: assessing biophysical drivers using machine learning and Google Earth Engine. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 197(4). [CrossRef]

- Fenta, A. A., Yasuda, H., Haregeweyn, N., Belay, A. S., Hadush, Z., Gebremedhin, M. A., & Mekonnen, G. (2017). The dynamics of urban expansion and land use/land cover changes using remote sensing and spatial metrics: The case of Mekelle city of northern Ethiopia. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 38(14), 4107–4129. [CrossRef]

- Frimpong, B. F., & Molkenthin, F. (2025). Tracking Urban Expansion Using Random Forests for the Classification of Landsat Imagery ( 1986 – 2015 ) and Predicting.

- Gawali, B. W. (2009). Classification of land use / land cover using artificial intelligence.

- Gessesse, B., Bewket, W., & Ababa, A. (2015). Why Does Accuracy Assessment and Validation of Multiresolution based Satellite Image Classification Matter ? Ethiopian Journal of Science and Technology, 38(1), 29–42.

- Gharaibeh, A. A., Jaradat, M. A., & Kanaan, L. M. (2023). A Machine Learning Framework for Assessing Urban Growth of Cities and Suitability Analysis. Land, 12(1), 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Gondwe, J. F., Lin, S., & Munthali, R. M. (2021). Analysis of Land Use and Land Cover Changes in Urban Areas Using Remote Sensing: Case of Blantyre City. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q., Sun, W., Li, X., Jiang, S., & Tian, J. (2023). A new ensemble classification approach based on Rotation Forest and LightGBM. Neural Computing and Applications, 35(15), 11287–11308. [CrossRef]

- Hamud, A. M., Shafri, H. Z. M., & Shaharum, N. S. N. (2021). Monitoring Urban Expansion and Land Use/Land Cover Changes in Banadir, Somalia Using Google Earth Engine (GEE). IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 767(1). [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M. M., & Southworth, J. (2018). Analyzing land cover change and urban growth trajectories of the mega-urban region of Dhaka using remotely sensed data and an ensemble classifier. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(1), 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Hassen, K., Anteneh, Y., Iguala, D., & Bedo, T. (2025). Discover Sustainability Spatiotemporal analysis of urban expansion and its impact on farmlands in the central Ethiopia metropolitan area. Discover Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Kang, N. N. H. (2019). © 2019. This manuscript version is made available under the Elsevier user license https://www.elsevier.com/open-access/userlicense/1.0/. In Reseachgate (Vol. 95616, Issue 509).

- Khan, A., & Sudheer, M. (2022). Machine learning-based monitoring and modeling for spatio-temporal urban growth of Islamabad. Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science, 25(2), 541–550. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M., & Johnson, K. (2013). Applied Predictive Modeling with Applications in R. In Springer (Vol. 26). http://appliedpredictivemodeling.com/s/Applied_Predictive_Modeling_in_R.pdf.

- Loukika, K. N., Keesara, V. R., & Sridhar, V. (2021). Analysis of land use and land cover using machine learning algorithms on google earth engine for Munneru river basin, India. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(24). [CrossRef]

- Mantero, P., Moser, G., & Serpico, S. B. (2004). Partially supervised classification of remote sensing images using SVM-based probability density estimation. 2003 IEEE Workshop on Advances in Techniques for Analysis of Remotely Sensed Data, 43(3), 327–336. [CrossRef]

- Megahed, Y., Cabral, P., Silva, J., & Caetano, M. (2015). Land cover mapping analysis and urban growth modelling using remote sensing techniques in greater Cairo region-Egypt. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 4(3), 1750–1769. [CrossRef]

- Moisa, M. B., Dejene, I. N., Roba, Z. R., & Gemeda, D. O. (2022). Impact of urban land use and land cover change on urban heat island and urban thermal comfort level: a case study of Addis Ababa City, Ethiopia. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 194(10). [CrossRef]

- Molla, M. B., Gelebo, G., & Girma, G. (2024). Urban expansion and agricultural land loss : a GIS-Based analysis and policy implications in Hawassa city , Ethiopia. November. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, E., Li, X., Sadek, M., & Dossou, J. F. (2021). Monitoring and Forecasting of Urban Expansion Using Machine Learning-Based Techniques and Remotely Sensed Data: A Case Study of Gharbia Governorate, Egypt. Remote Sensing, 13(22), 4498. [CrossRef]

- Mutale, B., Withanage, N. C., Mishra, P. K., Shen, J., Abdelrahman, K., & Fnais, M. S. (2024). A performance evaluation of random forest, artificial neural network, and support vector machine learning algorithms to predict spatio-temporal land use-land cover dynamics: a case from lusaka and colombo. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 12(September), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Nigar, A., Li, Y., Jat Baloch, M. Y., Alrefaei, A. F., & Almutairi, M. H. (2024). Comparison of machine and deep learning algorithms using Google Earth Engine and Python for land classifications. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 12(May), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Nyamekye, C., Kwofie, S., Ghansah, B., Agyapong, E., & Boamah, L. A. (2020). Assessing urban growth in Ghana using machine learning and intensity analysis: A case study of the New Juaben Municipality. Land Use Policy, 99. [CrossRef]

- Ouma, Y. O., Keitsile, A., Nkwae, B., Odirile, P., Moalafhi, D., & Qi, J. (2023). Urban land-use classification using machine learning classifiers: comparative evaluation and post-classification multi-feature fusion approach. European Journal of Remote Sensing, 56(1). [CrossRef]

- Pandit, S., Shimada, S., & Dube, T. (2024). Comprehensive analysis of land use and cover dynamics in djibouti using machine learning technique: A multi-temporal assessment from 1990 to 2023. Environmental Challenges, 15(February), 100920. [CrossRef]

- Park, J., Lee, Y., & Lee, J. (2021). Assessment of machine learning algorithms for land cover classification using remotely sensed data. Sensors and Materials, 33(11), 3885–3902. [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, S., Areendran, G., Punia, M., & Sahoo, S. (2022). Spatio-temporal pattern of urban eco-environmental quality of Indian megacities using geo-spatial techniques. Geocarto International, 37(17), 5067–5090. [CrossRef]

- Pushpalatha, V., Mahendra, H. N., Prasad, A. M., Sharmila, N., Kumar, D. M., Basavaraju, N. M., Pavithra, G. S., & Mallikarjunaswamy, S. (2024). An Assessment of Land Use Land Cover Using Machine Learning Technique. Nature Environment and Pollution Technology, 23(4), 2211–2219. [CrossRef]

- Puttinaovarat, S., & Horkaew, P. (2017). Urban areas extraction from multi sensor data based on machine learning and data fusion. Pattern Recognition and Image Analysis, 27(2), 326–337. [CrossRef]

- Ranagalage, M., Ratnayake, S. S., Dissanayake, D. M. S. L. B., Kumar, L., Wickremasinghe, H., Vidanagama, J., Cho, H., Udagedara, S., Jha, K. K., Simwanda, M., Phiri, D., Perera, E. N. C., & Muthunayake, P. (2020). Spatiotemporal variation of urban heat islands for implementing nature-based solutions: A case study of kurunegala, Sri Lanka. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 9(7). [CrossRef]

- Regassa, B., Kassaw, M., & Bagyaraj, M. (2020). Analysis of Urban Expansion and Modeling of LULC Changes Using Geospatial Techniques: The Case of Adama City. Remote Sensing of Land, 4(1–2), 40–58. [CrossRef]

- Roy, D. P., Wulder, M. A., Loveland, T. R., C.E., W., Allen, R. G., Anderson, M. C., Helder, D., Irons, J. R., Johnson, D. M., Kennedy, R., Scambos, T. A., Schaaf, C. B., Schott, J. R., Sheng, Y., Vermote, E. F., Belward, A. S., Bindschadler, R., Cohen, W. B., Gao, F., … Zhu, Z. (2014). Landsat-8: Science and product vision for terrestrial global change research. Remote Sensing of Environment, 145, 154–172. [CrossRef]

- Sahak, A. S., Karsli, F., Ahmadi, K., & Saraj, M. A. (2024). Geospatial Assessment of Urban Sprawl: A Case Study of Herat City, Afghanistan. Australian Journal of Engineering and Innovative Technology, May, 51–69. [CrossRef]

- Salim, M., Bhattacharjee, S., Sharma, N., Sharma, K., & Garg, R. D. (2025). Spatial analysis and classification of land use patterns in Lucknow district , UP , India using GIS and random forest approach Spatial analysis and classification of land use patterns in Lucknow district , UP , India using GIS and random forest approach. January. [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, S., Bhurtyal, U., & Campus, P. (2024). Urban Growth Prediction Using Satellite Imageries with Applications of Machine Learning Algorithm in Pokhara Metropolitan City. 3(2).

- Schneider, A., & Woodcock, C. E. (2008). Compact, dispersed, fragmented, extensive? A comparison of urban growth in twenty-five global cities using remotely sensed data, pattern metrics and census information. Urban Studies, 45(3), 659–692. [CrossRef]

- Shifaw, E., Sha, J., Li, X., Jiali, S., & Bao, Z. (2020). Remote sensing and GIS-based analysis of urban dynamics and modelling of its drivers, the case of Pingtan, China. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 22(3), 2159–2186. [CrossRef]

- Sigopi, M., Shoko, C., & Dube, T. (2024). Advancements in remote sensing technologies for accurate monitoring and management of surface water resources in Africa: an overview, limitations, and future directions. Geocarto International, 39(1). [CrossRef]

- Sofi, A. A. (2005). Urban growth and its impact on environment in Kashmir valley. Mukt Shabd Journal, 9(5), 5558–5564.

- Sokolova, M., Japkowicz, N., & Szpakowicz, S. (2006). AI 2006: Advances in Artificial Intelligence: 19th Australian Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Hobart, Australia, December 4-8, 2006. Proceedings. AI 2006: Advances in Artificial Intelligence, c, 1015–1021. [CrossRef]

- Subasinghe, S., Estoque, R. C., & Murayama, Y. (2016). Spatiotemporal analysis of urban growth using GIS and remote sensing: A case study of the Colombo metropolitan area, Sri Lanka. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 5(11). [CrossRef]

- Tassi, A., Gigante, D., Modica, G., Di Martino, L., & Vizzari, M. (2021). Pixel-vs. Object-based landsat 8 data classification in google earth engine using random forest: The case study of maiella national park. Remote Sensing, 13(12). [CrossRef]

- Terfa, B. K., Chen, N., Liu, D., Zhang, X., & Niyogi, D. (2019). Urban expansion in Ethiopia from 1987 to 2017: Characteristics, spatial patterns, and driving forces. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(10), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, F. T. (2020). Analysis of Spatio-temporal urban expansion of Bure town since. 19(4), 2875–2885. [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, W., Elias, E., Warkineh, B., Tekalign, M., & Abebe, G. (2024). Modeling of land use and land cover changes using google earth engine and machine learning approach: implications for landscape management. Environmental Systems Research, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Tessema, M. W., & Abebe, B. G. (2023). Quantification of land use / land cover dynamics and urban growth in rapidly urbanized countries : The case Hawassa city , Ethiopia. Urban, Planning and Transport Research, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Tikuye, B. G., Rusnak, M., Manjunatha, B. R., & Jose, J. (2023). Land Use and Land Cover Change Detection Using the Random Forest Approach: The Case of The Upper Blue Nile River Basin, Ethiopia. Global Challenges, 7(10), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, A. (2024). a Review: Machine Learning Algorithms. Data Science: Practical Approach with Python & R, August, 162–175. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D., Gao, X., Yang, Y., Guo, K., Han, K., & Xu, L. (2025). Advances and Future Prospects in Building Extraction from High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 18, 6994–7016. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Wang, H., Xie, P., Rao, Y., & He, Q. (2020). Revisiting Spatiotemporal Changes in Global Urban Expansion during 1995 to 2015. Complexity, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., & Ling, G. H. T. (2024). Spatio-Temporal Changes and Driving Forces Analysis of Urban Open Spaces in Shanghai between 1980 and 2020: An Integrated Geospatial Approach. Remote Sensing, 16(7). [CrossRef]

| Landsat7 (ETM+) | Landsat8 (LOI) | Sentinel-2 | ||||||

| Band no | Wavelength (µm) | Pixel size(m) | Band no | Wave length (µm) | Pixel size(m) | Band no | Wave length (µm) | Pixel size(m) |

| B1 | 0.45 -0.52 | 30 | B1 | 0.433-0.45 | 30 | B1 | 0.443 | 60 |

| B2 | 0.52 - 0.60 | 30 | B2 | 0.45- 0.515 | 30 | B2 | 0.490 | 10 |

| B3 | 0.63 - 0.69 | 30 | B3 | 0.525- 0.60 | 30 | B3 | 0.560 | 10 |

| B4 | 0.76 - 0.90 | 30 | B4 | 0.630- 0.68 | 30 | B4 | 0.665 | 10 |

| B5 | 1.55 - 1.75 | 30 | B5 | 0.845-0.88 | 30 | B5 | 0.705 | 20 |

| B6 | 10.4 -12.3 | 60 | B6 | 1.56 -1.66 | 30 | B6 | 0.740 | 20 |

| B7 | 2.08 - 2.35 | 30 | B7 | 2.10 - 2.30 | 60 | B7 | 0.783 | 20 |

| B8 | 0.52 -0.90 | 15 | B8 | 0.50 - 0.68 | 15 | B8 | 0.842 | 10 |

| B9 | 1.36 - 1.39 | 30 | B8A | 0.865 | 20 | |||

| B10 | 10.3- 11.3 | 100 | B9 | 0.945 | 60 | |||

| B11 | 11.5 -12.5 | 100 | B10 | 1.375 | 60 | |||

| B11 | 1.610 | 20 | ||||||

| B12 | 2.190 | 20 | ||||||

| Urban cover class Data sets | |||||||

| Years | Built up | Vegetation | Agriculture | Bare land | Training | Testing | Total |

| 2000 | 490 | 505 | 530 | 530 | 1644 | 411 | 2055 |

| 2015 | 593 | 615 | 621 | 621 | 1960 | 490 | 2450 |

| 2025 | 586 | 603 | 603 | 603 | 1916 | 479 | 2395 |

| LULC class (features) | Description of the class (features) |

| Vegetation Area |

Areas characterized by natural or partially natural vegetation, such as urban forests, areas dominated by shrubs, and grass land |

| Built Up Area | Areas decided on as residential, commercial, industrial, urban settlements, and transportation facilities |

| Bare Land |

Areas with minimum plants in the main comprise uncovered earth substances which include stone, gravel, sand, silt, and clay. Examples include sandy areas, barely exposed rocks, degraded lands, and quarries. |

|

Agricultural Area |

Agricultural croplands, cultivated lands, and agricultural fallow lands and irrigated agriculture area, perennial crops |

| Model | Evaluation metrics | years | |||

| 2000 | 2015 | 2025 | |||

| Accuracy | 95.86% | 95.9% | 97.29% | ||

|

RF |

User’s accuracy (Precision) | Built up | 93.75% | 94.67% | 97.58% |

| Vegetation | 96.15% | 96.08% | 95.83% | ||

| Agriculture | 97.48% | 97.53% | 97.79% | ||

| Bare land |

94.44% |

94.78% | 97.28% | ||

| Produce’s Accuracy (Recall) | Built up | 88.24% | 93.55% | 96.03% | |

| Vegetation | 96.5% | 96.09% | 98.57% | ||

| Agriculture | 95.68% | 96.93% | 97.79% | ||

| Bare land | 99.17% | 96.21% | 97.28% | ||

| Kappa coefficient | 94.15% | 94.5% | 96.32% | ||

|

SVM |

Accuracy | 95% | 93.06% | 93.74 | |

| User’s accuracy (Precision) | Built up | 87% | 91.40% | 94.35% | |

| Vegetation | 96% | 92.16% | 86.84% | ||

| Agriculture | 96% | 94.48% | 96.21% | ||

| Bare land | 97% | 93.18% | 94.56% | ||

| Produce’s Accuracy (Recall) | Built up | 92% | 91.40% | 92.86% | |

| Vegetation | 93% | 92.16% | 94.29% | ||

| Agriculture | 96 % | 94.48% | 93.38% | ||

| Bare land | 97.50% | 93.18% | 94.56% | ||

| Kappa coefficient | 93.94% | 90.63% | 91.5% | ||

|

LULC Class |

Area 2000 (ha) |

2000 Area (%) |

Area 2015 (ha) |

2015 Area (%) |

Change (ha) |

Change Area (%) |

| Built up | 779.969 | 4.50% | 1875.646 | 10.82% | +1,095.68 | +6.32% |

| Vegetation | 2,275.16 | 13.13% | 3,013.55 | 17.39% | +738.39 | +4.26% |

| Agriculture | 12,384.65 | 71.45% | 10,696.33 | 61.69% | –1,688.32 | –9.76% |

| Bare land | 1,890.64 | 10.91% | 1,744.90 | 10.07% | –145.74 | –0.84% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).