Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Capacity Optimization

- (2)

- Operation Optimization

- (3)

- Co-optimization of Capacity and Operation

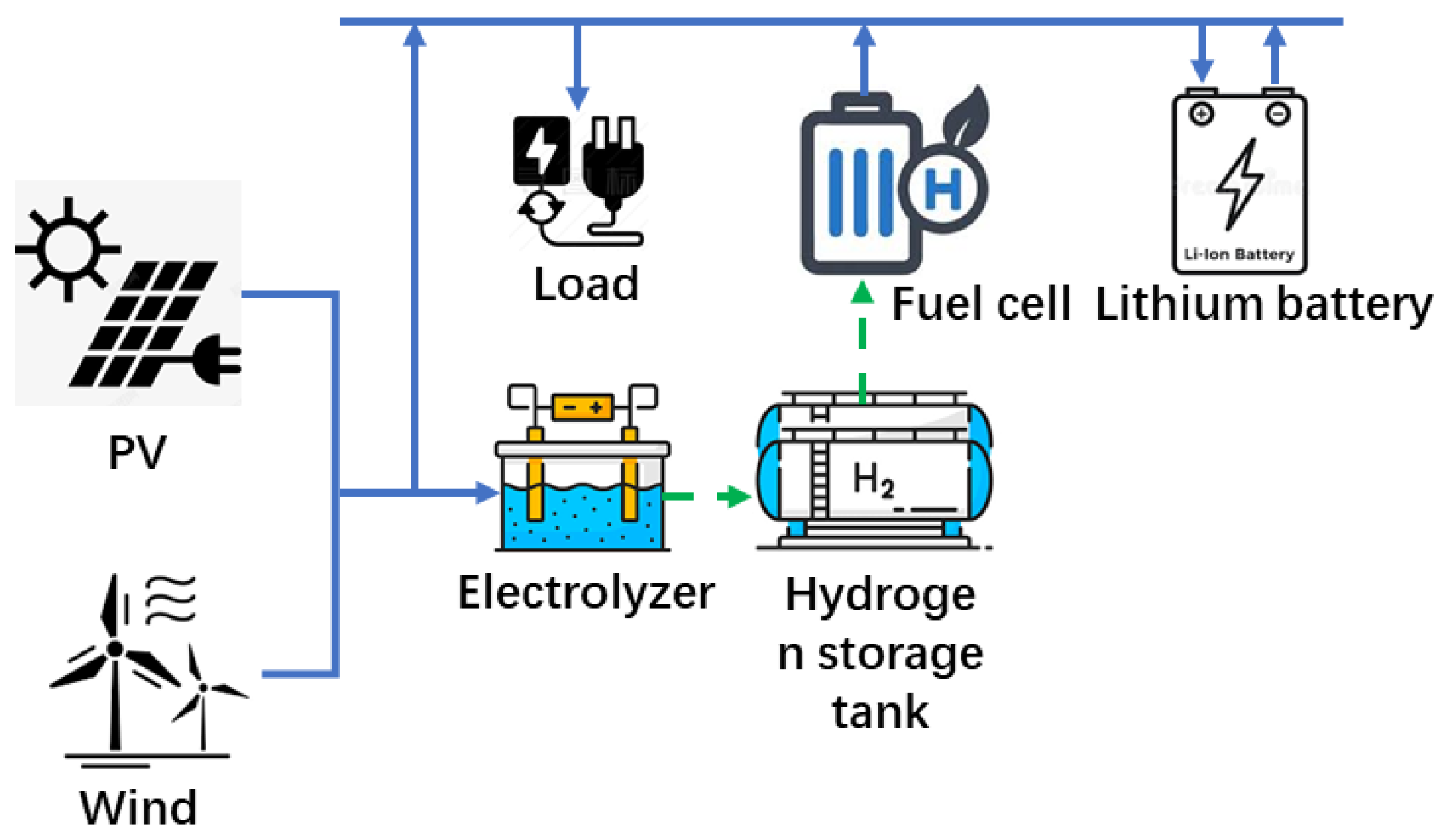

2. System Model

2.1. Inner-Layer Operation Optimization

2.1.1. Objective Function

2.1.2. Constraints

2.1.2.1. Hydrogen Energy Storage System Constraints

- (1)

- Power operation constraints

- (2)

- Mutual-exclusion constraint (to prevent the electrolyzer and fuel cell from operating simultaneously)

- (3)

- Hydrogen storage tank dynamic balance equation

- (4)

- Hydrogen storage tank state constraints

- (5)

- To ensure the feasibility and stability of the system during multi-day continuous operation, periodic constraints are imposed.

- (9)

- To prevent frequent start-stop cycling of the electrolyzer, which may accelerate its degradation, a start-stop operation constraint is imposed.

2.1.2.2. Battery System Constraints

- (1)

- Power operation constraints

- (2)

- Charging/discharging mutual-exclusion constraint (to prevent simultaneous charging and discharging)

- (3)

- Battery state balance equation

- (4)

- Battery state upper and lower bound constraints

2.1.2.3. System Power Balance Equation

2.2. Outer-Layer Capacity Optimization

2.2.1. Objective Function

2.2.2. Constraints

- (1)

- System reliability constraints

- (2)

- Capacity configuration boundary constraints

- (3)

- Battery charging/discharging duration constraints

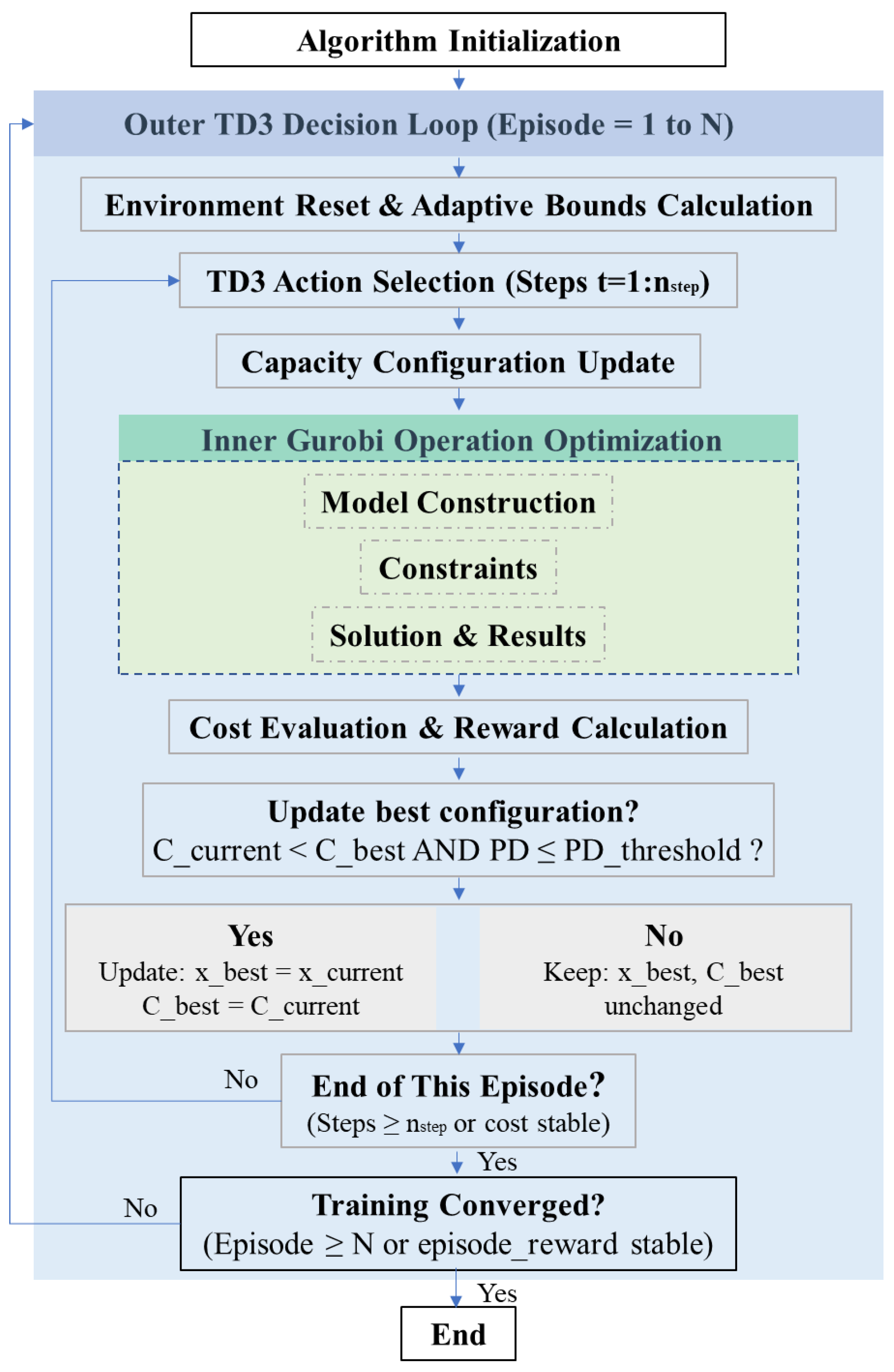

3.1. Collaborative Optimization Mechanism

3.1.1. Outer Layer Design

3.1.2. Inner Layer Design

- State and action space design

- 2.

- Reward function design

- 3.

- Network architecture and training strategy

- (1)

- Network architecture

- (2)

- TD3 core strategy

- (3)

- Network update mechanism

- (4)

- Soft update mechanism

- (5)

- Prioritized experience replay

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Case Setting

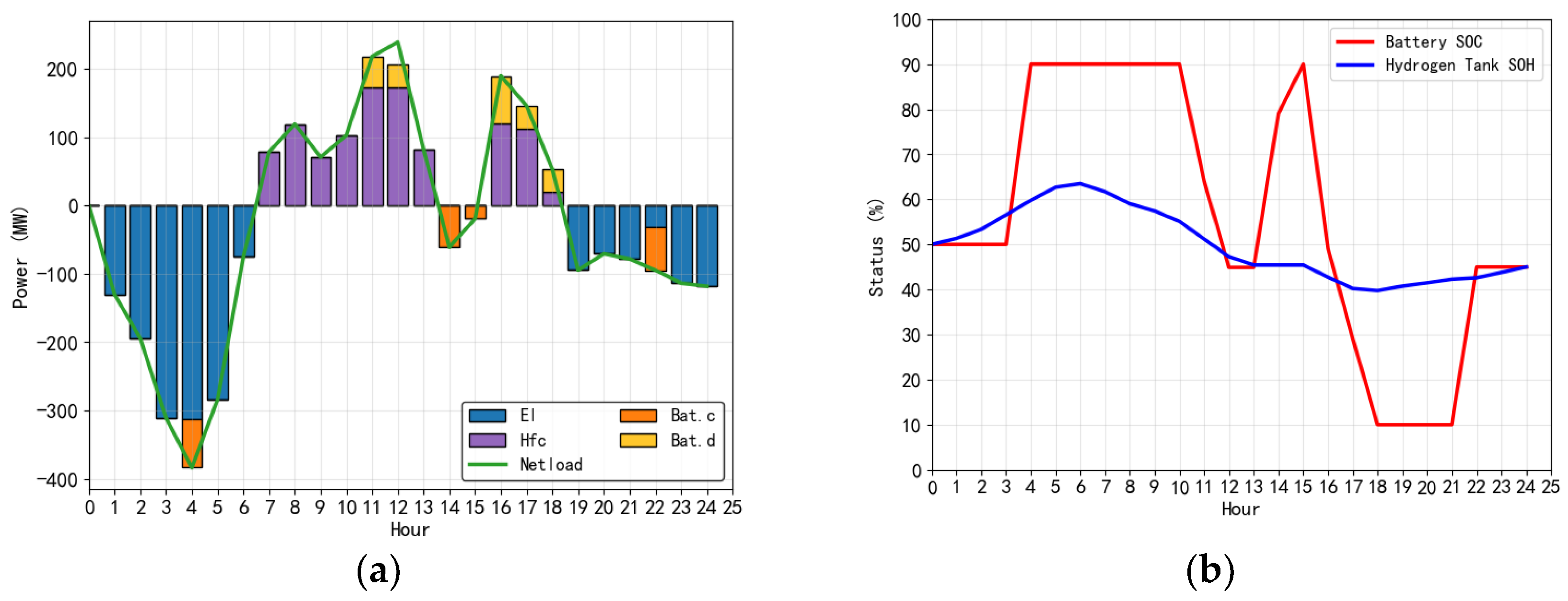

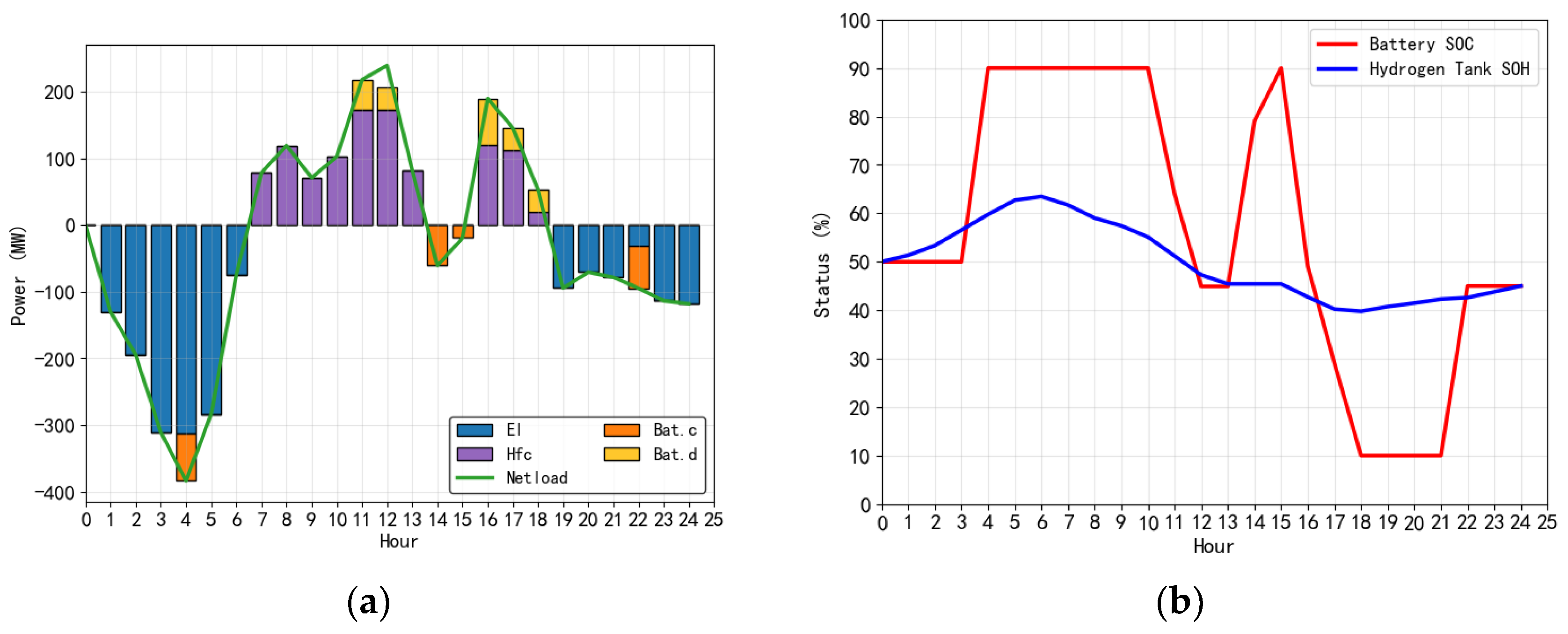

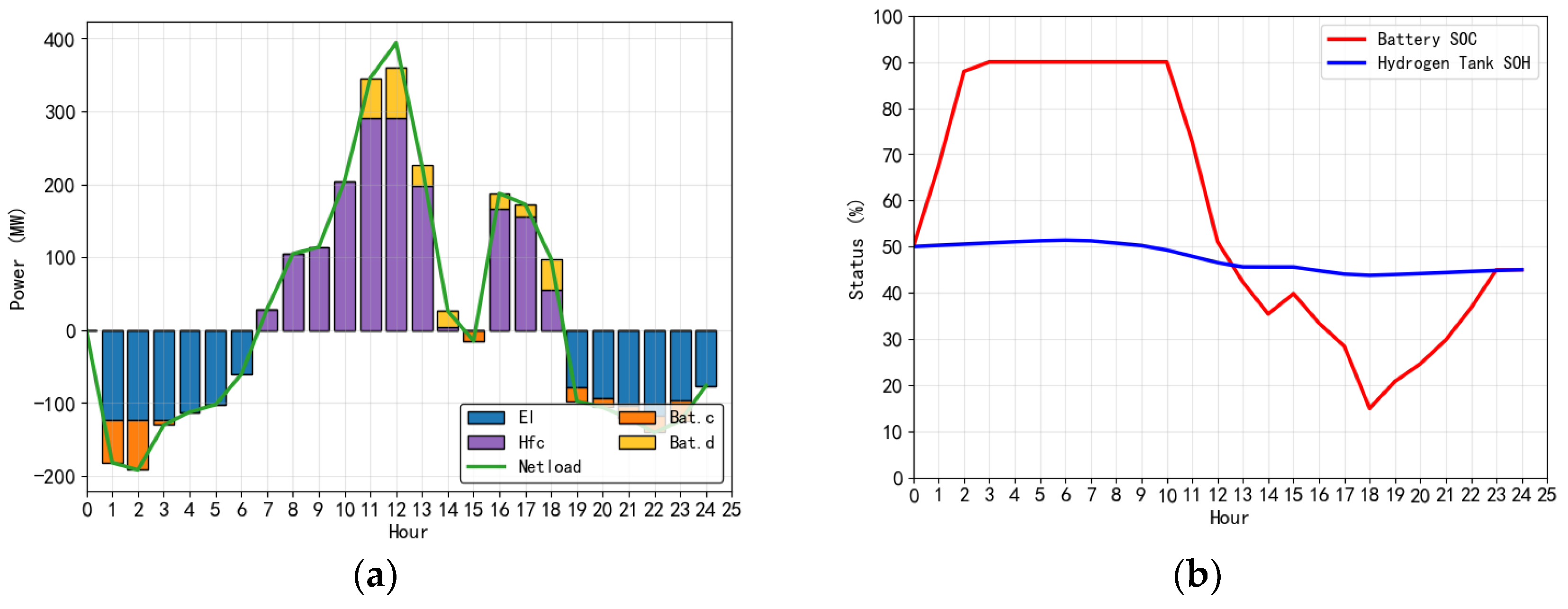

4.2. Algorithmic Solution and Results Analysis

4.3. Comparative Analysis

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis

4.4.1. Sensitivity Analysis of Key Component Costs

- (1)

- Sensitivity to Electrolyzer Power Cost

- (2)

- Sensitivity to Fuel Cell Power Cost

- (3)

- Sensitivity to Hydrogen Tank Cost

- (4)

- Sensitivity to Lithium Battery Power Cost

- (5)

- Sensitivity to Lithium Battery Energy-Capacity Cost

4.4.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Renewable Energy Penetration

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HESS | Hybrid energy storage system |

| DRL | Deep reinforcement learning |

| EL | Electrolyzer |

| BESS | Battery energy storage system |

| MIP | Mixed integer programming |

| FC | Fuel cell |

| HST | Hydrogen storage tank |

| MDP | Markov Decision Process |

| TD3 | Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient |

References

- Zhou, Z.; Ma, Z.; Mu, T. Hybrid energy storage capacity optimization based on VMD-SG and improved Firehawk optimization. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 239, 111218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, N.; Cao, F. Capacity optimization of hybrid energy storage systems for offshore wind power volatility smoothing. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Shang, W.; Feng, G.; Huang, B.; Xiong, X. Coordinated control algorithm of hydrogen production-battery based hybrid energy storage system for suppressing fluctuation of PV power. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 88, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghazaly, M.; Abdel-Salam, M.; Nayel, M.; Hashem, M. Techno-economic utilization of hybrid optimized gravity-supercapacitor energy-storage system for enriching the stability of grid-connected renewable energy sources. J. Energy Storage 2025, 107, 115002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkholy, M.; Schwarz, S.; Aziz, M. Advancing renewable energy: Strategic modeling and optimization of flywheel and hydrogen-based energy system. J. Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; et al. Model simulation and multi-objective capacity optimization of wind power coupled hybrid energy storage system. Energy 2025, 319, 134887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Quraan, A.; Athamnah, I. Economic tri-level control-based sizing and energy management optimization for efficiency maximization of stand-alone HRES. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 302, 118140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guven, A.F.; Abdelaziz, A.Y.; Samy, M.M.; Barakat, S. Optimizing energy dynamics: A comprehensive analysis of hybrid energy storage systems integrating battery banks and supercapacitors. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 312, 118560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, H.; Tan, Z. Capacity optimization of hybrid energy storage system for flexible islanded microgrid based on real-time price-based demand response. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 136, 107581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Deng, H.; Qi, X. Cost-based site and capacity optimization of multi-energy storage system in the regional integrated energy networks. Energy 2022, 261, 125240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; et al. Optimal planning of electric-heating integrated energy system in low-carbon park with energy storage system. J. Energy Storage 2024, 99, 113327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, K.; Mokryani, G.; Cooke, K.; Campean, F.; Chambers, T. Bi-level optimal sizing, siting and operation of utility-scale multi-energy storage system to reduce power losses with peer-to-peer trading in an electricity/heat/gas integrated network. J. Energy Storage 2024, 83, 110738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; et al. Research on planning optimization of integrated energy system based on the differential features of hybrid energy storage system. J. Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, M.; Habibi, M.; Najaafi, N.; Safarpour, H. Optimization of hybrid energy management system based on high-energy solid-state lithium batteries and reversible fuel cells. Energy 2023, 283, 128454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Xu, B.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Lawler, B.; Ayalew, B. Deep reinforcement learning-based energy management system enhancement using digital twin for electric vehicles. Energy 2024, 312, 133384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; et al. Integrated battery thermal and energy management for electric vehicles with hybrid energy storage system: A hierarchical approach. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 317, 118853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barelli, L.; Bidini, G.; Ciupageanu, D.A.; Pelosi, D. Integrating hybrid energy storage system on a wind generator to enhance grid safety and stability: A levelized cost of electricity analysis. J. Energy Storage 2021, 34, 102050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Liao, Y.; He, J. Economic dispatch for grid-connected wind power with battery-supercapacitor hybrid energy storage system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 1118–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharatee, A.; Ray, P.K.; Ghosh, A. A power management scheme for grid-connected PV integrated with hybrid energy storage system. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2022, 10, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, L.; Wu, Y.; Luo, C.; Tang, Z.; Kerekes, T. Near-optimal energy management strategy for a grid-forming PV and hybrid energy storage system. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025, 16, 1422–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dsouza, O.D.; Shilpa, G.; Rajnikanth; Irusapparajan, G. Optimized energy management for hybrid renewable energy sources with hybrid energy storage: An SMO-KNN approach. J. Energy Storage 2024, 96, 112152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathishkumar, R.; Venkateswaran, M.; Deepamangai, P.; Rajan, P.S. An efficient power management control strategy for grid-independent hybrid renewable energy systems with hybrid energy storage: Hybrid approach. J. Energy Storage 2024, 96, 112685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.H.A.; Chen, J.; Kamel, S.; Safaraliev, M.; Matrenin, P. Power management and control of hybrid renewable energy systems with integrated diesel generators for remote areas. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 89, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, U.; Zhang, X.; Beng, G.H.; Subramanian, L.; Lu, H.H.C.; Fernando, T. Enhanced energy management system for isolated microgrid with diesel generators, renewable generation, and energy storages. Appl. Energy 2023, 350, 121624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, P.K.; Pattnaik, M. Supervisory power management scheme of a laboratory scale wind-PV based LVDC microgrid integrated with hybrid energy storage system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 4723–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramu, S.K.; Vairavasundaram, I.; Palaniyappan, B.; Bragadeshwaran, A.; Aljafari, B. Enhanced energy management of DC microgrid: Artificial neural networks-driven hybrid energy storage system with integration of bidirectional DC-DC converter. J. Energy Storage 2024, 88, 111562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkwanyana, T.B.; Siti, M.W.; Wang, Z.; Mulumba, W. Hybrid energy storage lifespan optimization based on an enhanced fuel-cell degradation model and meta-heuristic algorithm. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 5712–5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, H.-N.; Tran, L.; Vu, T.; Vo-Duy, T.; Nguyễn, B.-H. A global optimal benchmark for energy management of microgrid (GoBuG) integrating hybrid energy storage system. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2024, 15, 5429–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zou, G.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Sun, Y.; Li, G. Microgrid energy management strategy considering source-load forecast error. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 164, 110372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Xun, Q.; Liserre, M.; Yang, H. Energy management of electric-hydrogen hybrid energy storage systems in photovoltaic microgrids. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 80, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepehrzad, R.; Moridi, A.R.; Hassanzadeh, M.E.; Seifi, A.R. Intelligent energy management and multi-objective power distribution control in hybrid micro-grids based on the advanced fuzzy-PSO method. ISA Trans. 2021, 112, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekira, O.; Boujoudar, Y.; El Moussaoui, H.; Boharb, A.; Lamhamdi, T.; El Markhi, H. An improved microgrid energy management system based on hybrid energy storage system using ANN NARMA-L2 controller. J. Energy Storage 2024, 98, 113096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lyu, C.; Bai, Y.; Yang, K.; Song, Z.; Meng, J. Optimal scheduling strategy for hybrid energy storage systems of battery and flywheel combined multi-stress battery degradation model. J. Energy Storage 2024, 99, 113208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkholy, M.H.; et al. A resilient and intelligent multi-objective energy management for a hydrogen-battery hybrid energy storage system based on MFO technique. Renew. Energy 2024, 222, 119768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intra-day and seasonal peak shaving oriented operation strategies for electric–hydrogen hybrid energy storage in isolated energy systems. Sustainability 2024.

- Han, F.; Zeng, J.; Lin, J.; Gao, C. Multi-stage distributionally robust optimization for hybrid energy storage in regional integrated energy system considering robustness and nonanticipativity. Energy 2023, 277, 127729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, J.; Lu, R. Multi-objective economic optimization scheduling of CCHP micro-grid based on improved bee colony algorithm considering the selection of hybrid energy storage system. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, T.; Meng, F. An energy router based on multi-hybrid energy storage system with energy coordinated management strategy in island operation mode. Renew. Energy 2023, 212, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Zhu, H.; Tong, Y.; Dong, Z. Optimal design and control of battery-ultracapacitor hybrid energy storage system for BEV operating at extreme temperatures. J. Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehraban, A.; Farjah, E.; Ghanbari, T.; Garbuio, L. Integrated optimal energy management and sizing of hybrid battery/flywheel energy storage for electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2023, 19, 10967–10976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z. Sizing optimization and energy management strategy for hybrid energy storage system using multiobjective optimization and random forests. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 11421–11430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; et al. Optimal hybrid energy storage system planning of community multi-energy system based on two-stage stochastic programming. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 61035–61047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Li, X.; Jin, C. Optimal capacity configuration and dynamic pricing strategy of a shared hybrid hydrogen energy storage system for integrated energy system alliance: A bi-level programming approach. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 69, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Han, Z.; Zhang, C.; Li, P.; Wu, D.; Li, P. Optimal configuration for regional integrated energy systems with multi-element hybrid energy storage. Energy 2023, 277, 127672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Guo, S.; Zhou, J.; Song, G.; Kurban, A.; Wang, H. The multi-stage framework for optimal sizing and operation of hybrid electrical-thermal energy storage system. Energy 2022, 245, 123248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, X. Optimal sizing of hybrid energy storage system under multiple typical conditions of sources and loads. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2025, 44, 2439298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atawi, I.E.; Abuelrub, A.; Al-Shetwi, A.Q.; Albalawi, O.H. Design of a wind-PV system integrated with a hybrid energy storage system considering economic and reliability assessment. J. Energy Storage 2024, 81, 110405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganege, H.C.; Chandima, D.P.; Karunadasa, J.P.; Wheeler, P. Optimization of grid-connected solar PV systems with hybrid energy storage system: A case study of the Sri Lankan power system. J. Energy Storage 2025, 114, 115634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Han, J.; Chen, H.; Houari, A.; Saim, A. Research on power allocation strategy and capacity configuration of hybrid energy storage system based on double-layer variational modal decomposition and energy entropy. J. Energy Storage 2024, 95, 112492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, Y.-C.; Banyupramesta, I.G.A.; Lu, J.-C. Optimal operation and capacity sizing for a sustainable shared energy storage system with solar power and hydropower generator. J. Energy Storage 2025, 110, 115173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Blondeau, J. Optimal combination of daily and seasonal energy storage using battery and hydrogen production to increase the self-sufficiency of local energy communities. J. Energy Storage 2024, 92, 112206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Chu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, D. Operation strategy and optimization configuration of hybrid energy storage system for enhancing cycle life. J. Energy Storage 2024, 95, 112560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Gonzalez, M.; Hernandez, J.C.; Vidal, P.G.; Jurado, F. Novel optimization algorithm for the power and energy management and component sizing applied to hybrid storage-based photovoltaic household-prosumers for the provision of complementarity services. J. Power Sources 2021, 482, 228918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Quraan, A.; Athamnah, I.; Malkawi, A.M.A. Efficiency maximization of stand-alone HRES based on tri-level economic predictive technique. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; et al. Collaborative optimization of VRB-PS hybrid energy storage system for large-scale wind power grid integration. Energy 2023, 265, 126292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, D.; Xiao, Z.; Qiu, Q.; Tao, X.; Qian, Q. Power Allocation and Capacity Optimization Configuration of Hybrid Energy Storage Systems in Microgrids Using RW-GWO-VMD. Energies 2025, 18, 4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modu, B.; Abdullah, M.P.; Alkassem, A.; Hamza, M.F. Optimal rule-based energy management and sizing of a grid-connected renewable energy microgrid with hybrid storage using Levy flight algorithm. Energy Nexus 2024, 16, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, S.; van Hoof, H.; Meger, D. Addressing Function Approximation Error in Actor-Critic Methods. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2018), Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Component | Economic/Technical parameter | Value | Unit |

| EL (Electrolyzer) | 786 | $/kWh | |

| 0.8 | - | ||

| 0.4 | - | ||

| 70000 | Hour | ||

| HFC (Fuel Cell) | 286 | $/kW | |

| 0.6 | - | ||

| 0.3 | - | ||

| 30000 | Hour | ||

| HT (Hydrogen Tank) | 1143 | $/kg | |

| 0 | - | ||

| 1 | - | ||

| 0.97 | - | ||

| 0.98 | - | ||

| Battery | 429 | $/kW | |

| 357 | $/kWh | ||

| 0.98 | - | ||

| 0.98 | - | ||

| 0.1 | - | ||

| 0.9 | - | ||

| 10 | $/kWh | ||

| HESS(Hybrid Energy Storage System) | 20 | Year | |

| i | 0.08 | - | |

| Other | 33.33 | kWh/kg |

| Decision variable | Optimized result | Unit |

| 312.23 | kW | |

| 173.26 | kW | |

| 225.90 | kg | |

| 71.60 | kW | |

| 174.68 | kWh | |

| Minimum daily total cost | 209.10 | $ |

| Cases | (kW) | (kW) | (kg) | (kW) | (kWh) | ($) | Computation time (s) | |

| Case 1 | DRL+G | 312.23 | 173.26 | 225.90 | 71.60 | 174.68 | 209.10 | 1.3 |

| Case 2 | GA+G | 262.88 | 93.19 | 112.77 | 133.42 | 460.72 | 219.34 | 250 |

| PSO+G | 279.96 | 115.35 | 146.30 | 104.32 | 353.56 | 211.87 | 225 | |

| G | 309.16 | 173.33 | 220.43 | 74.39 | 186.89 | 208.73 | 1800 | |

| Case 3 | Battery-only | - | - | - | 383.57 | 3297.74 | 473.35 | - |

| Hydrogen-only | 383.57 | 238.93 | 76.25 | - | - | 140.19 | - | |

| ($/kW) | (kW) | (kW) | (kg) | (kW) | (kWh) | ($) |

| 550 | 319.07 | 172.27 | 232.94 | 64.53 | 158.19 | 186.71 |

| 629 | 274.13 | 109.31 | 132.36 | 109.37 | 386 | 198.5 |

| 707 | 307.63 | 156.85 | 217.02 | 75.94 | 194.1 | 203.3 |

| 786 | 312.23 | 173.26 | 225.9 | 71.6 | 174.68 | 209.1 |

| 864 | 270.75 | 106.74 | 122.61 | 112.82 | 406.87 | 218.51 |

| 943 | 266.8 | 102.38 | 109.69 | 116.77 | 435.96 | 225.15 |

| 1021 | 255.13 | 93.96 | 72.45 | 128.44 | 521.15 | 231.62 |

| ($/kW) | (kW) | (kW) | (kg) | (kW) | (kWh) | ($) |

| 200 | 304.59 | 167.7 | 210.58 | 81.9 | 208.87 | 205.98 |

| 229 | 317.57 | 175.64 | 230.91 | 68.55 | 163.37 | 207.27 |

| 257 | 317.28 | 173.78 | 231.34 | 68.11 | 162.31 | 207.79 |

| 286 | 312.23 | 173.26 | 225.9 | 71.6 | 174.68 | 209.1 |

| 314 | 318.06 | 173.25 | 231.93 | 65.71 | 160.49 | 210.95 |

| 343 | 280.19 | 108.37 | 154.28 | 103.38 | 338.23 | 213.84 |

| 371 | 273.75 | 109.99 | 132.11 | 109.82 | 385.45 | 215.13 |

| ($/kg) | (kW) | (kW) | (kg) | (kW) | (kWh) | ($) |

| 800 | 334.53 | 181.63 | 255.82 | 49.54 | 120.08 | 187.76 |

| 914 | 320.07 | 175.68 | 234.14 | 63.54 | 155.56 | 194.59 |

| 1029 | 286.16 | 115.47 | 164.88 | 96.73 | 327.47 | 206.44 |

| 1143 | 312.23 | 173.26 | 225.9 | 71.6 | 174.68 | 209.1 |

| 1257 | 253.81 | 102.13 | 65.9 | 129.77 | 534.64 | 215.21 |

| 1371 | 251.5 | 90.13 | 59.94 | 132.91 | 548.25 | 216.69 |

| 1486 | 254.86 | 95.91 | 57.52 | 128.72 | 553.54 | 219.14 |

| ($/kW) | (kW) | (kW) | (kg) | (kW) | (kWh) | ($) |

| 300 | 305.77 | 169.31 | 212.97 | 80.29 | 203.19 | 207.81 |

| 343 | 306.89 | 171.54 | 215.44 | 77.49 | 197.67 | 208.86 |

| 386 | 306.34 | 171.57 | 215.45 | 78.51 | 199.52 | 209.82 |

| 429 | 312.23 | 173.26 | 225.9 | 71.6 | 174.68 | 209.1 |

| 471 | 273.55 | 125.53 | 131.58 | 110.09 | 386.62 | 213.42 |

| 514 | 314.97 | 180.85 | 259.79 | 57.69 | 143.77 | 216.62 |

| 557 | 278.22 | 146.66 | 131.77 | 107.87 | 386.84 | 217.57 |

| ($/kWh) | (kW) | (kW) | (kg) | (kW) | (kWh) | ($) |

| 250 | 249.66 | 88.36 | 53.83 | 134.04 | 561.86 | 179.71 |

| 286 | 244.15 | 99.73 | 53.04 | 146.54 | 611.26 | 198.23 |

| 321 | 264.4 | 99.8 | 101.19 | 119.17 | 455.11 | 203.01 |

| 357 | 312.23 | 173.26 | 225.9 | 71.6 | 174.68 | 209.1 |

| 393 | 285.23 | 150.21 | 168.27 | 98.33 | 304.06 | 217.79 |

| 429 | 311.65 | 168.48 | 225.19 | 77.5 | 177.39 | 218.42 |

| 464 | 325.33 | 174.73 | 241.01 | 58.71 | 142.63 | 220.08 |

|

Renewable energy penetration scenario |

(kW) | (kW) | (kg) | (kW) | (kWh) | ($) |

| High | 312.23 | 173.26 | 225.9 | 71.6 | 174.68 | 209.1 |

| Medium | 318.37 | 212.37 | 51.83 | 117.86 | 372.66 | 203.48 |

| Low | 123.18 | 290.64 | 1083.62 | 69.76 | 327.83 | 470.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).