Introduction & Motivation

Very few error-free computer programs have ever been written[

1]. In fact, in professional software development, the industry average is around 1–25 errors per 1,000 lines of code for delivered software[

2]. While there is a growing interest in improving programming skills in academia[

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8], few researchers benefit from comprehensive training in software engineering and testing[

3,

9]. Whereas scientists invest a significant portion of their time in creating software, they frequently fail to leverage modern advancements in software engineering[

10]. One reason for the limited adoption of software engineering practices is a general lack of awareness about their benefits[

11]. For instance, in a survey in 2017, only around 50% of postdoctoral researchers had received any formal training in software development[

12]. Illustrating this further, a minority of scientists are familiar with or make use of basic testing procedures[

13]. Thus, it is most likely the case that the error rate in code written by academic scientists is much higher than in the software industry.

This raises concerns regarding the accuracy of scientific results. Indeed, there are numerous high-profile examples from the recent past where scientific conclusions have been affected by coding errors[

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. These examples include cases with major implications for political and societal decisions[

16,

17,

24]. While honest errors are an inevitable part of science — and their voluntary disclosure should be applauded, not punished — it is our duty to mitigate their occurrence.

One way to tackle this challenge is to establish code review as an integral step of all scientific projects. Code review is defined as “

an activity in which people other than the author of a software deliverable examine it for defects and improvement opportunities”[

25], with some hailing this practice as “

the single biggest thing [one] can do to improve [their] code”[

26]. Peer code review represents one of the most effective methods for detecting errors and is a standard process in the software industry[

2].

Yet, code review is not a common practice in science. Several reasons account for this: lack of knowledge, cultural opposition, or resistance to change[

25]. Indeed, there is often the perception that a certain project is not large or critical enough to warrant code review. In addition, there is a widely held belief that code reviews take up too much time and could slow projects down[

25]. However, this perspective neglects the fact that any technique enabling early corrections and improvements has the potential to save disproportionately more time in the future. In addition, early detection of critical issues can avoid costly corrections down the line, including amendments or, in the worst case, retraction of publications[

27]. Most importantly, it is central to the scientific process that any known source of potential errors is addressed proactively in order to protect the reliability of specific conclusions and the trustworthiness of science in general.

While we are not aware of any investigations that compare the frequency and/or impact of software errors across scientific fields, we deem it plausible that interdisciplinary fields which combine computational with other approaches may face particular challenges. This is because the very nature of these fields requires scientists, regardless of their background and experience with software engineering, to engage in the use, modification and construction of complex software.

Here, we focus on mental health research, a scientific field that increasingly relies on computational approaches and brings together scientists from very different backgrounds. In particular, we draw on our experience in computational subfields of mental health, specifically Translational Neuromodeling (TN; developing computational assays of brain [dys]function) and Computational Psychiatry (CP; the application of computational assays to clinical problems). These closely related fields are useful targets for discussing principles of code review in mental health research because they have a long tradition of using sophisticated computational methods (e.g., generative models, machine learning) and numerous data types (e.g. neuroimaging, electrophysiology, behavior, self-report, clinical outcomes).

This article does not address the general principles of good code design and documentation directly. These principles have been expanded upon in many previous excellent (and sometimes even humorous) references and resources[

9,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. In addition, we do not aim to prescribe rules or guidelines for code review. Again, many experienced software engineers have written excellent articles on the topic[

25,

38,

39,

40,

41], and several publications related to code review in research already exist[

42,

43,

44]. Instead, in order to lower barriers for researchers not yet familiar with code review, we aim to share our concrete workflows, experience with, and learnings from introducing code review into our research work. We hope that this pragmatic approach will provide a concrete point of entry for researchers who are looking to add code review to their project workflow but are unsure where to start.

Our Experience

At the institution where all co-authors work or used to work — the Translational Neuromodeling Unit in Zurich — code review by an independent scientist became mandatory in early 2019, after a prolonged phase-in period. We have since made independent code review a condition that must be fulfilled before accessing test (held-out) data in machine learning analyses and, in general, before submitting any articles for publication. This decision, as well as the requirements for a sufficient code review, were documented in an internal working instruction (WI). Initially, no detailed checklist was provided; instead, the initial WI described the mindset, principles and goals of code review in our unit. It focused on three main points: (1) reproduction of results on a different system/machine; (2) checking the overall steps of the analysis pipeline and searching for any obvious flaws; and (3) checking for “typical” errors that occur frequently in the context of the specific analysis approach. Finally, the code reviewer was asked to submit a brief written review, which documented what was done and what issues (if any) were encountered. This report was then timestamped and stored along with the code.

This process of code review also has implications for the code author. In addition to requiring well-structured and readable code, analyses are to be conducted in end-to-end pipelines, from raw data to the final results, including figures. Manual interventions are discouraged; if they are inevitable, they need to be documented in a precise manner so that the results can be reproduced.

In the last few years, this procedure has led to several significant errors being uncovered in our work, some early in the analyses, others later on. Examples of mistakes detected in our research group include:

Loading of incorrect data files.

Errors in the calculations of test statistics.

Indexing errors (e.g., in vector operations, during data anonymisation) leading to row-shifted data, resulting in subjects being associated with incorrect data.

Incorrect custom implementations of complex operations (i.e., nested cross-validation).

Unintended use of default settings in (external) open-source toolboxes. In this particular case, issues in the code were detected after publication. Once the programming mistake was discovered, the journal was proactively contacted and informed of the situation, analyses were rerun with the correct settings, and the updated results were published as a Corrigendum[

18].

Having one’s work scrutinized and criticized can be a difficult process, even when the reviewer is a colleague with good intentions. In order to increase acceptance of code review in our unit, a culture of openness is encouraged, and polite and constructive feedback is defined as a must. Furthermore, issues of wider interest (e.g. errors in the context of complex statistical or computational approaches) are openly discussed in larger rounds, e.g. our weekly methods or group meetings. Thus, while communication typically happens most intensively between the code author and the code reviewer, any other member of the research group can be consulted. In addition, the time for code review is factored into the timeline of a project. Thus, despite the additional efforts, the overall feeling in our research group is that code review not only plays a crucial role for detecting errors and fosters more trust in our results, but also offers learning opportunities for researchers that will likely prove useful for their future careers, whether in academia or industry.

A Proposal

In a dual effort to further standardize our code review procedures and make them available to interested scientists outside our unit, we have been developing a structured checklist based on our own experience, discussions within the lab, and external sources. The checklist is neither intended as a rigid standard nor does it claim to cover all possible aspects of code review; instead, it is meant to serve as a practical guide that lowers the barrier for research groups to introduce code review and helps them prioritize the most important steps in this process. By offering this pragmatic checklist, this paper aims to encourage a culture of regular and collaborative code review that ultimately increases the trustworthiness and robustness of mental health research.

In terms of external sources, we supplemented our own lab experience with established guidance from the broader software engineering community. Several resources contributed to our understanding of what makes code review effective, including practical guides on identifying potential issues related to functionality, performance, and maintainability[

45,

46]. These emphasize the importance of clear reviewer responsibilities, the role of testing, and the value of early and frequent feedback during code development[

26,

38,

39]. Best practices from large-scale software projects provided insight into systematic review standards, including expectations around readability, modularity, and minimizing technical debt[

32]. We also consulted curated collections of tools and methodologies for managing code review in collaborative settings, as well as discussions of common pitfalls specific to machine learning pipelines[

47,

48].

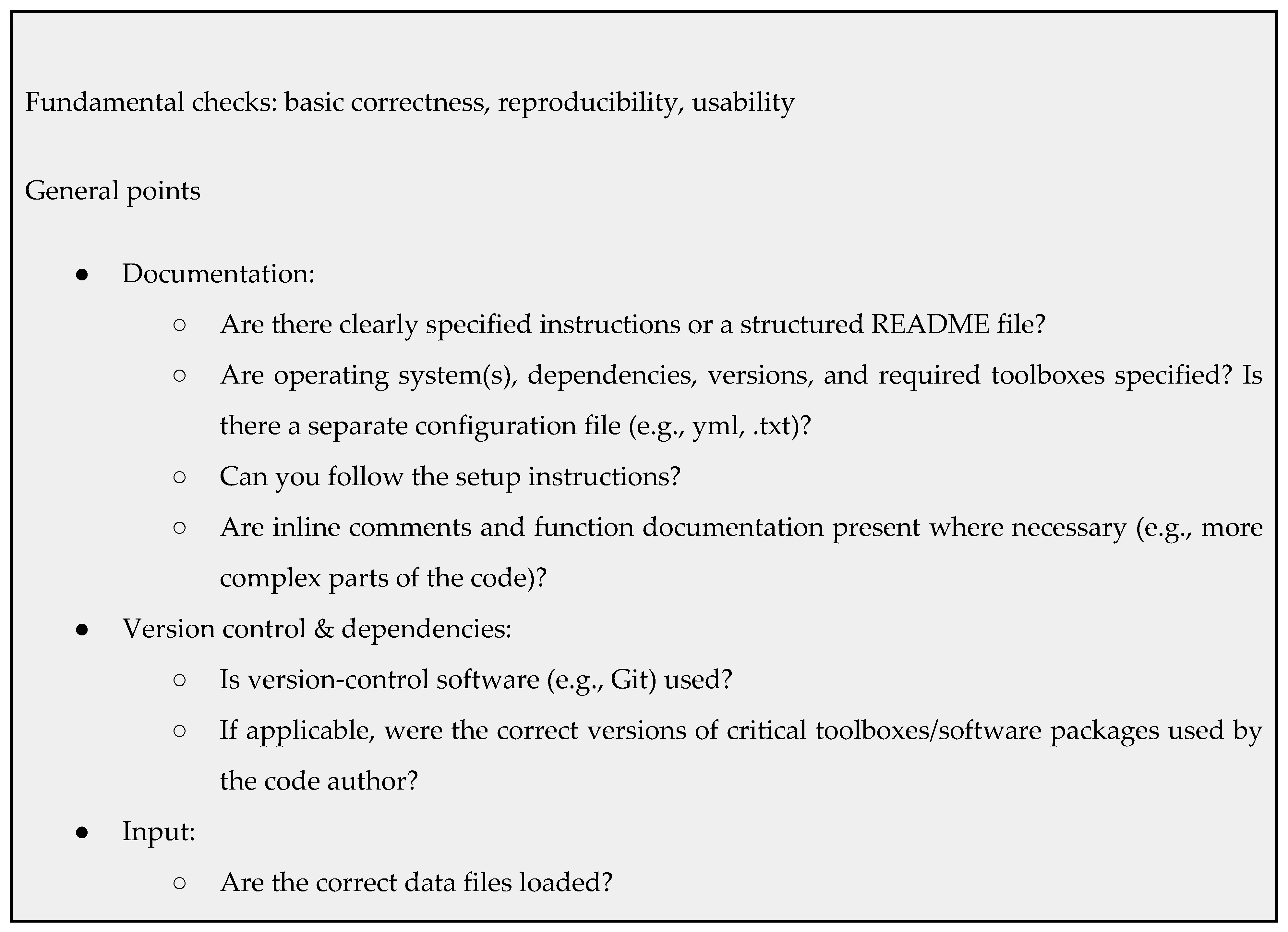

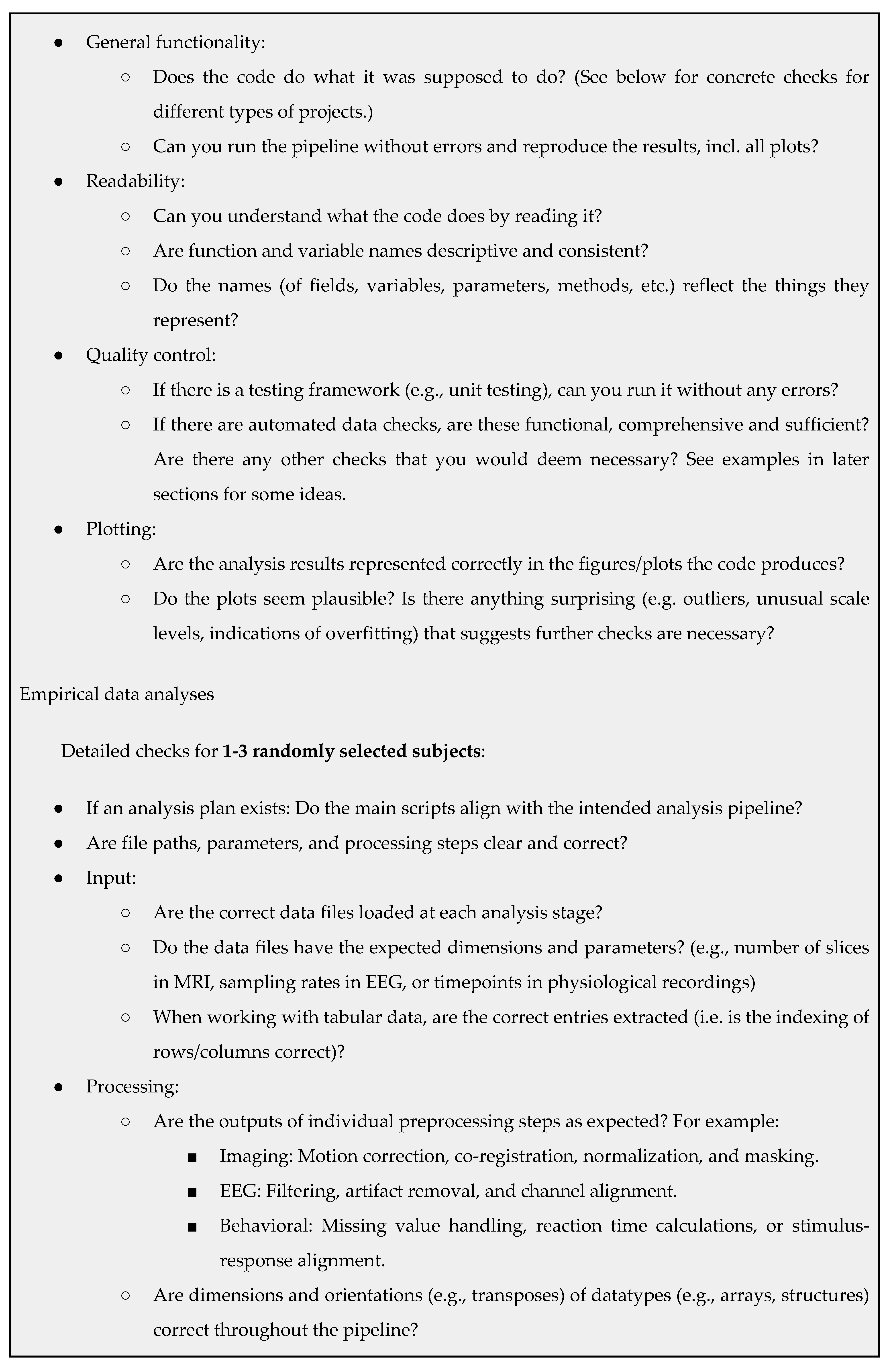

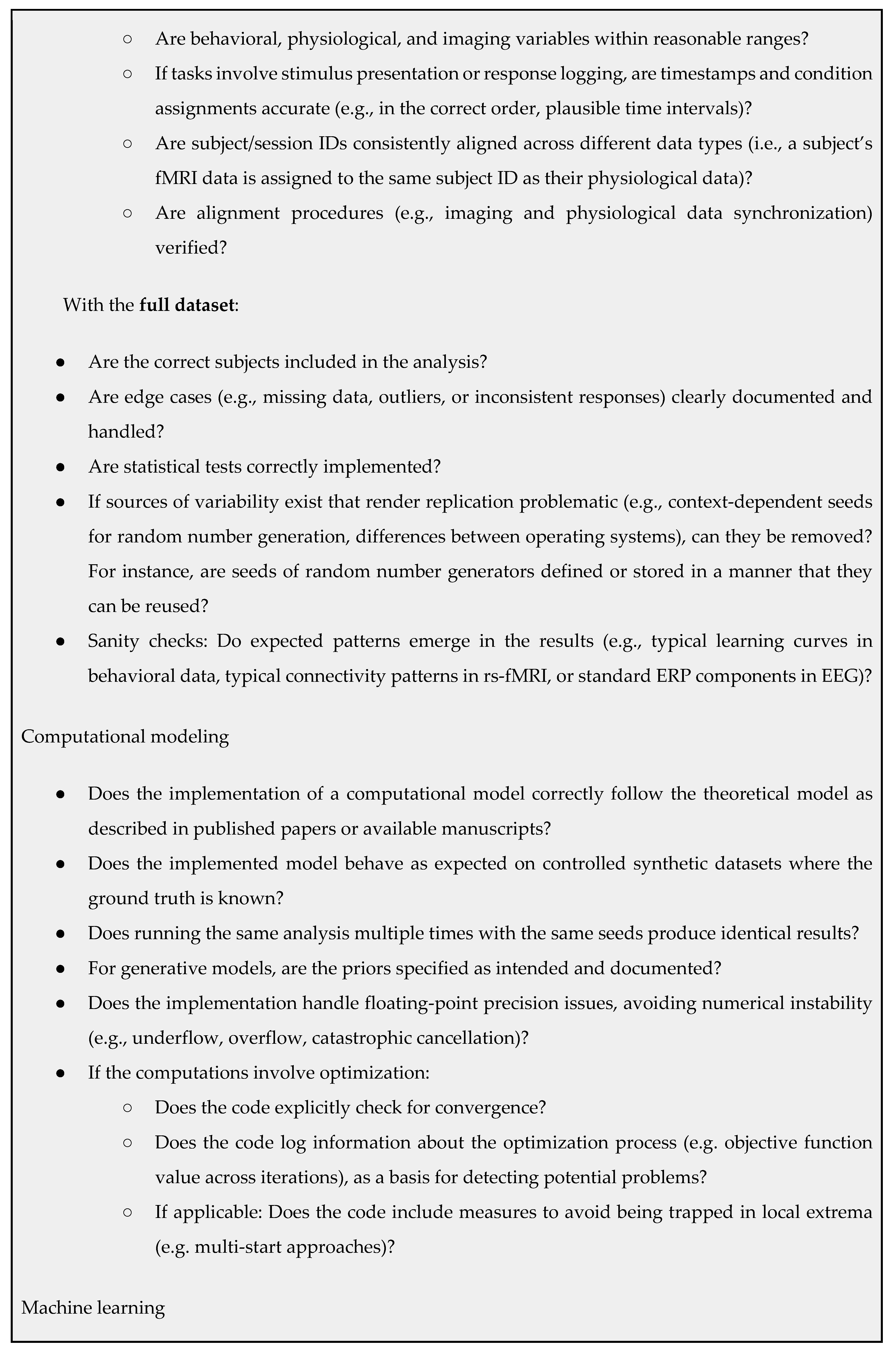

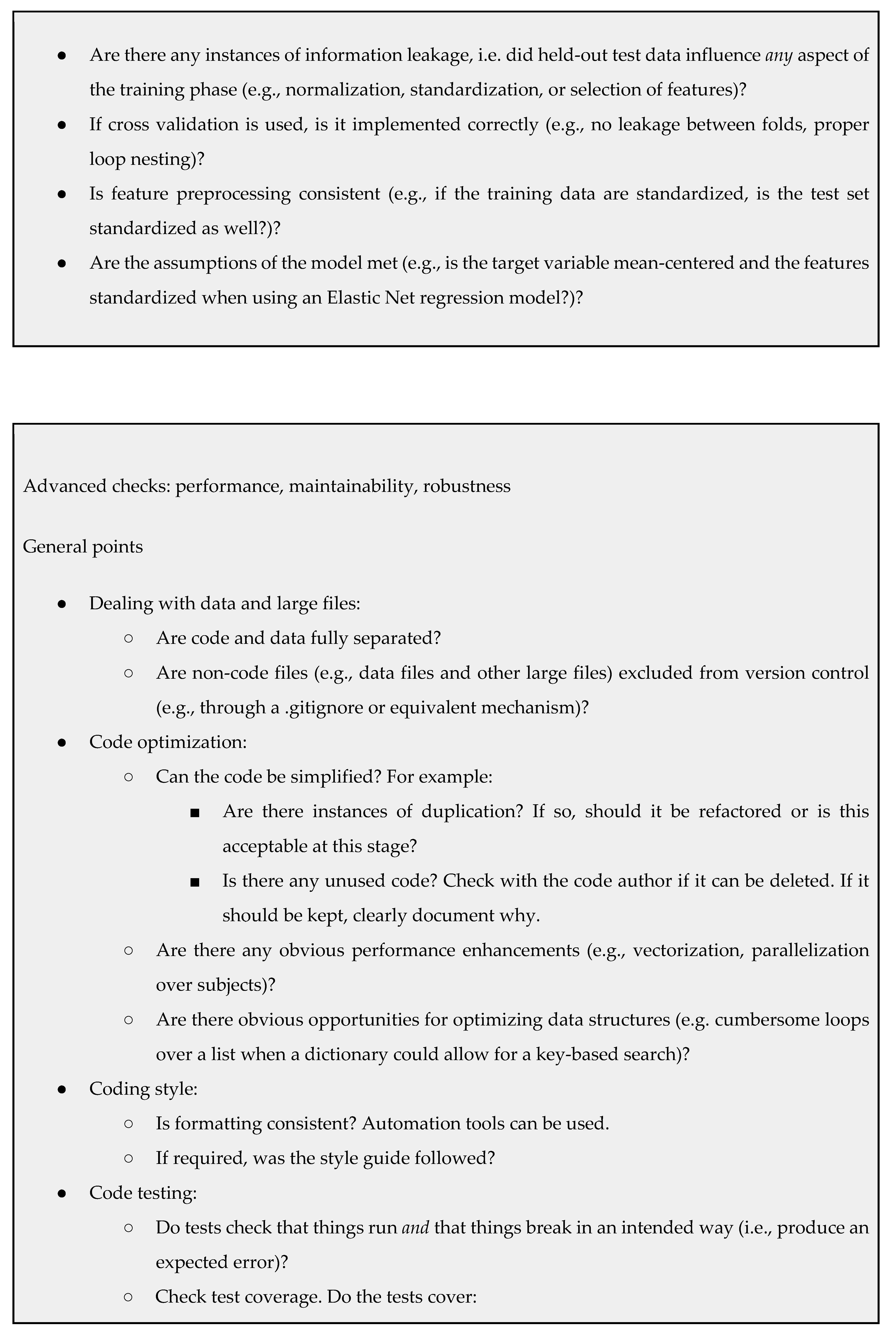

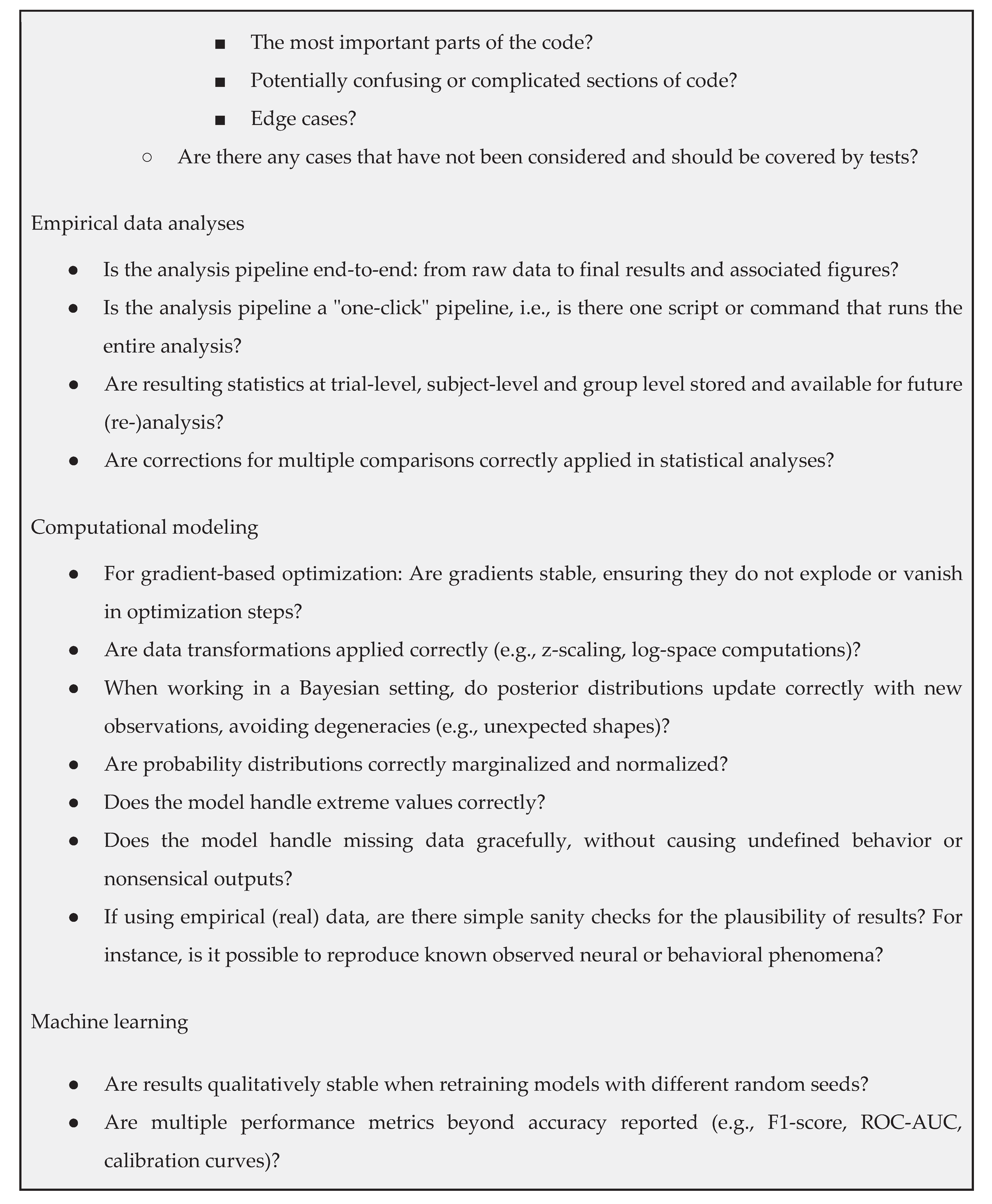

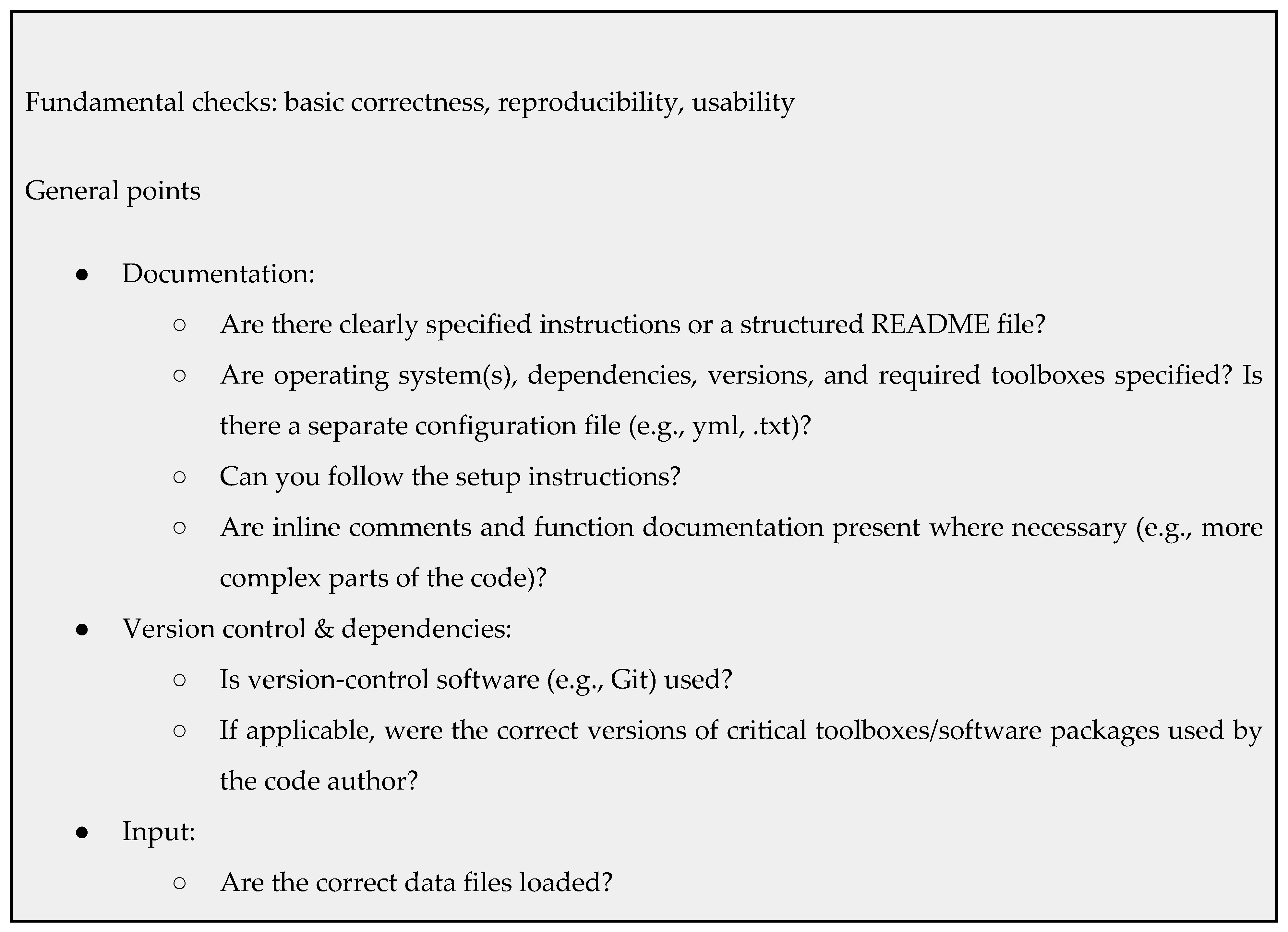

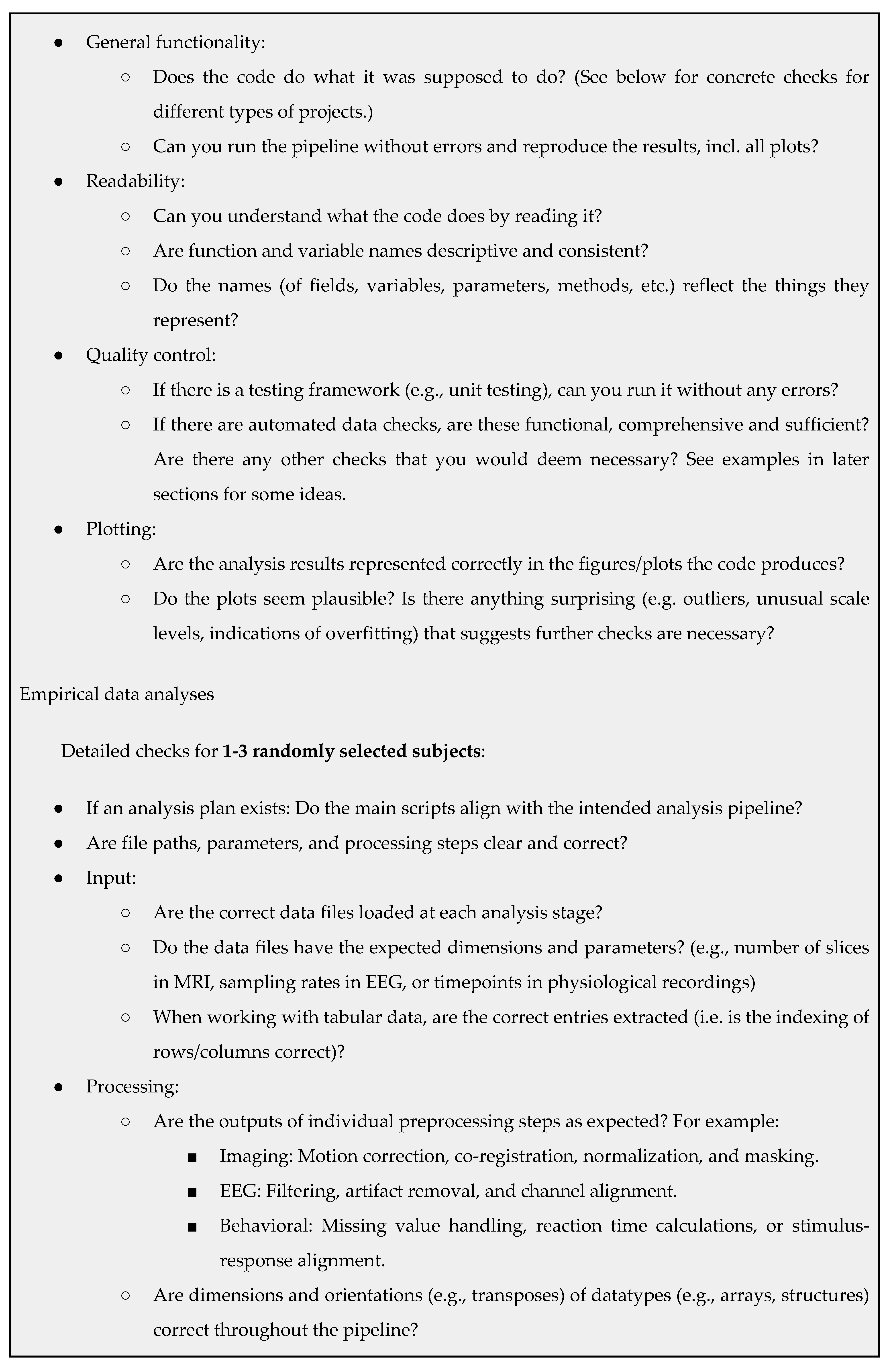

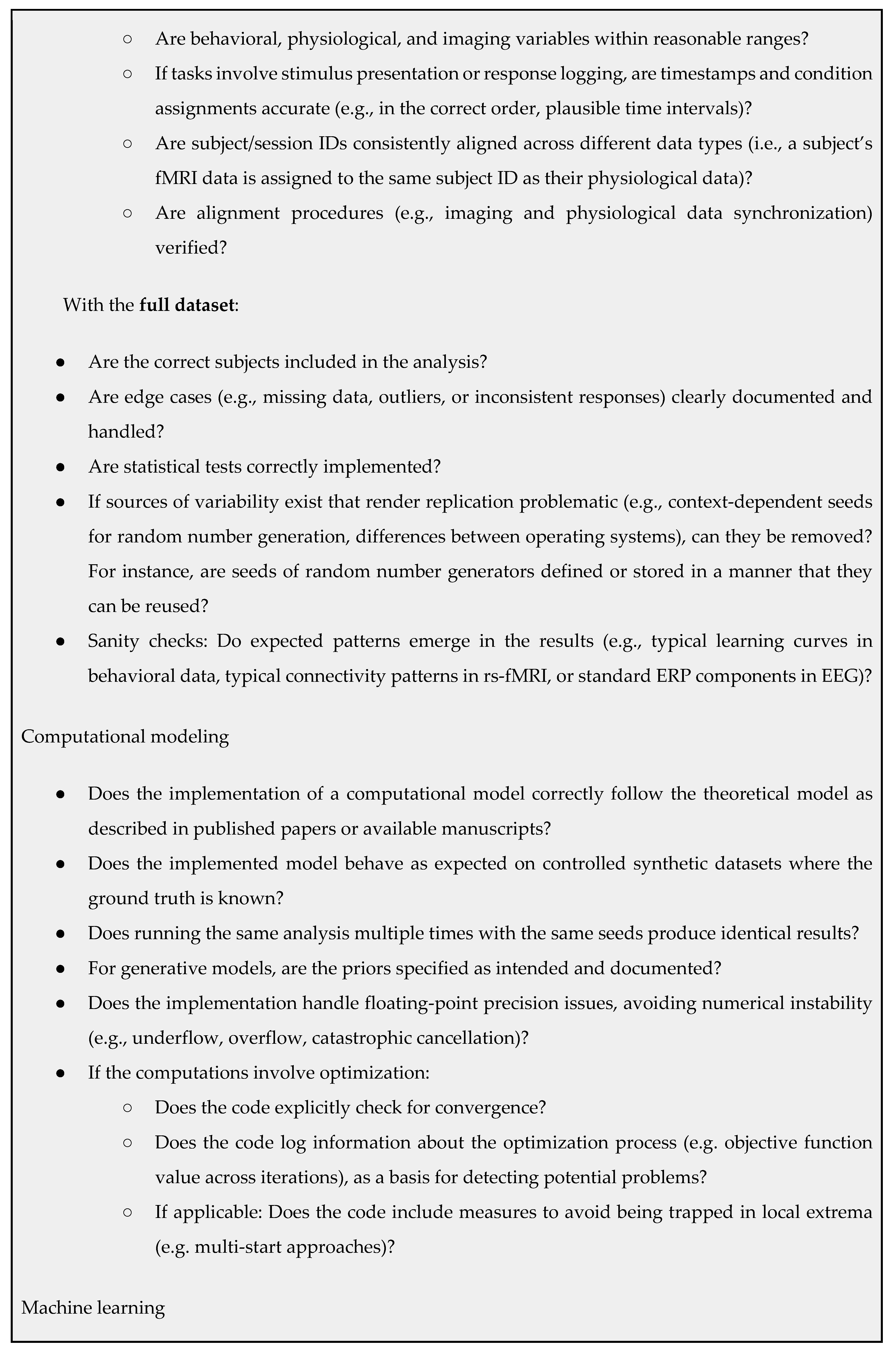

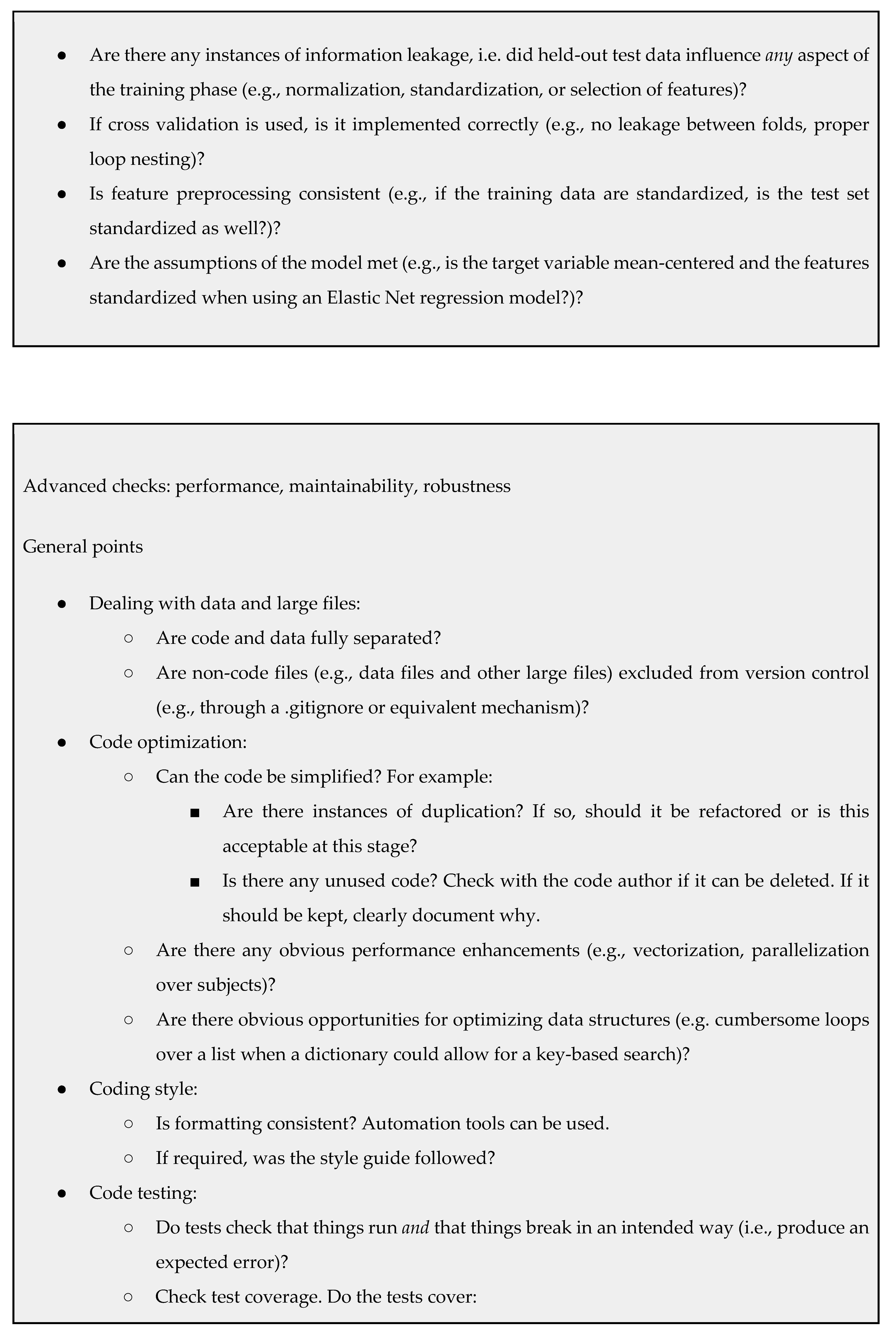

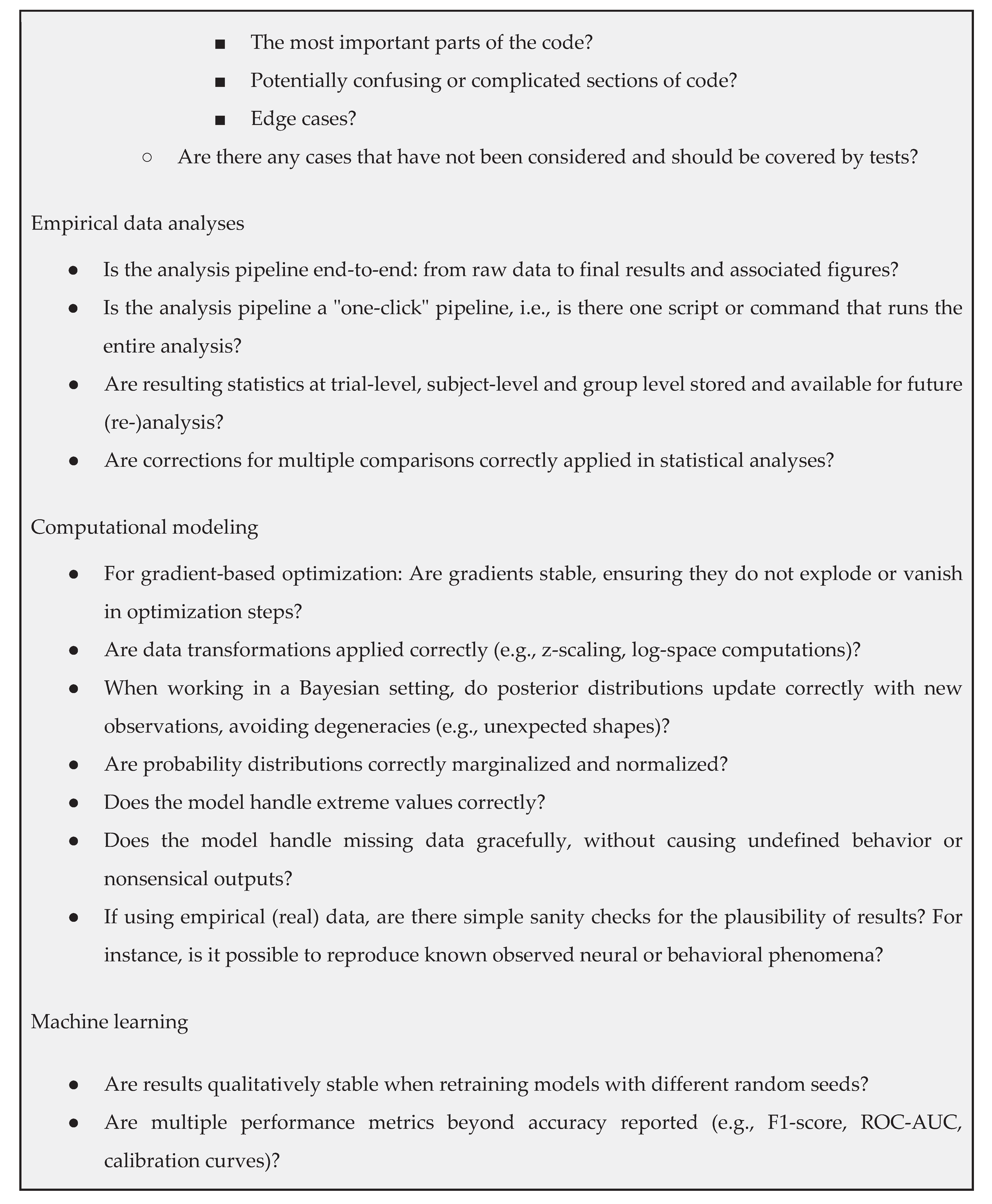

The checklist presented below is organized along two axes: level of priority and type of work. At the top level, we differentiate between fundamental checks (basic correctness, reproducibility, usability) and more advanced checks (performance, maintainability, robustness). Within each of these, we further separate general review points from domain-specific considerations. The latter are grouped according to the nature of the work: empirical data analyses, computational modeling, and machine learning[

49,

50]. The list is not intended to be exhaustive or final, but to provide a structured and adaptable reference to researchers and laboratories not yet familiar with code review.

Code Review and Analysis Plans

For clarity, it is important to distinguish the goals of code review from those of predefining analyses before the data are touched (i.e., analysis plans). Analysis plans prespecify the scientific questions (e.g., hypotheses) of a project and how they are addressed by concretely defined analyses. Defining analysis plans ex ante is an important and effective strategy to improve reproducibility and robustness of the scientific process. For example, they protect against cognitive biases, shield against mistaking postdictions for predictions, and prevent p-hacking[

51,

52]. In our unit, analysis plans were made mandatory in parallel to code review.

Analysis plans often include planned checks for robustness, such as sensitivity analyses or benchmarking predictive models of interest against simpler baseline models. In order to place constraints on the efforts of code reviewers, it is important to emphasize that their responsibility is not to search for potential gaps in analysis plans. In other words, the checks for robustness that code reviewers perform are conditional on the given analysis plan (if it exists). Of course, this should not prevent code reviewers from alerting the responsible scientists to missing robustness checks in an analysis plan; these can then be implemented post hoc as a deviation from the analysis plan that should be reported transparently in the manuscript.

Benefits, Costs, and a Way Forward

Despite the growing awareness of the importance of code quality in scientific computing, formal code review is rarely applied in the academic environment. One barrier may be the perceived costs: code review can be time-consuming and may expose errors that complicate ongoing work. However, in our view, the benefits (early error detection, enhanced reproducibility, and more robust scientific results) vastly outweigh these costs. Especially in high-impact research contexts, such as work with direct clinical or societal impact, the cost of undetected software errors may be far higher than the investment required for a review process. Furthermore, code review can also enhance the reputation of individual researchers and research groups as it signals a commitment to quality. As reproducibility crises across disciplines have shown, it is far more costly, professionally and scientifically, to issue corrections or retractions than to catch problems early in the process.

Looking ahead, the integration of large language models (LLMs) into the code review process presents an opportunity to both scale and systematize review efforts. Recent advances have shown that LLMs, particularly those with long-context capabilities, can assist in identifying bugs, suggest code improvements, and enforce standards across entire codebases. In particular, fine-tuned models have demonstrated significantly higher accuracy than general-purpose models, and techniques such as few-shot prompting, metadata augmentation, and parameter-efficient fine-tuning continue to improve performance while reducing computational overhead[

53,

54,

55,

56]. These systems are increasingly capable of generating readable comments, detecting latent defects, and even repairing code based on review feedback[

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62]. Of particular interest in scientific contexts is their emerging ability to retroactively analyze published code repositories (as well as the associated papers[

63]) and surface previously undetected errors, potentially preventing flawed findings from being propagated. At the same time, challenges such as hallucinations, training data bias, and interpretability of automated reviews highlight the need for human oversight and domain-specific tuning[

64,

65]. Nevertheless, as LLM tools become more reliable and privacy-aware, their role in routine code validation, and ultimately in the safeguarding of scientific integrity, is likely to expand.

In summary, we have presented a pragmatic, experience-based proposal for structured code review. The proposed framework is specifically motivated by our experiences with challenges encountered in computational subfields of mental health research, in particular Translational Neuromodeling and Computational Psychiatry, but will also broadly apply to other areas of neuroscience. Our proposed checklist offers a structured yet adaptable framework for identifying and prioritizing common issues, spanning experimental pipelines, theoretical modeling, and machine learning applications. By combining lessons from our own practice with insights from software engineering and considering the potential of emerging tools such as large language models, we hope to contribute to a more systematic and sustainable review culture in academic research. As the research community continues to confront challenges of reproducibility and software reliability, we see structured code review not as an administrative burden but as an opportunity for collaboration, quality assurance, and scientific integrity.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all present and past members of the Translational Neuromodeling Unit for their contributions to discussions and feedback about the code review process. This work was supported by funding from the René and Susanne Braginsky Foundation, ETH Foundation, and the University of Zurich (K.E.S.).

References

- Soergel, D. A. W. Rampant software errors may undermine scientific results. Preprint at (2015). [CrossRef]

- McConnell, S. Code Complete. (Microsoft Press, Redmond, Washington, 2004).

- Arvanitou, E.-M., Ampatzoglou, A., Chatzigeorgiou, A. & Carver, J. C. Software engineering practices for scientific software development: A systematic mapping study. Journal of Systems and Software 172, 110848 (2021).

- Storer, T. Bridging the Chasm: A Survey of Software Engineering Practice in Scientific Programming. ACM Comput. Surv. 50, 1–32 (2018).

- Woolston, C. Why science needs more research software engineers. Nature (2022). [CrossRef]

- RSECon 2025. RSECon25 https://rsecon25.society-rse.org/ (2025).

- Nordic RSE. Nordic RSE https://nordic-rse.org/.

- nl-rse. nl-rse https://nl-rse.org/.

- Merali, Z. Computational science: ...Error. Nature 467, 775–777 (2010).

- Heaton, D. & Carver, J. C. Claims about the use of software engineering practices in science: A systematic literature review. Information and Software Technology 67, 207–219 (2015).

- Schmidberger, M. & Brügge, B. Need of Software Engineering Methods for High Performance Computing Applications. in 2012 11th International Symposium on Parallel and Distributed Computing 40–46 (2012). doi:10.1109/ISPDC.2012.14.

- Nangia, U. & Katz, D. S. Track 1 Paper: Surveying the U.S. National Postdoctoral Association Regarding Software Use and Training in Research. 4361681 Bytes (2017) doi:10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.5328442.

- Wilson, G. Software Carpentry: Getting Scientists to Write Better Code by Making Them More Productive. Computing in Science & Engineering 8, (2006).

- Reynolds, M. Science Is Full of Errors. Bounty Hunters Are Here to Find Them. Wired.

- Knight, W. Sloppy Use of Machine Learning Is Causing a ‘Reproducibility Crisis’ in Science. Wired.

- He, X. et al. Author Correction: Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med 26, 1491–1493 (2020).

- Ashcroft, P. et al. COVID-19 infectivity profile correction. Swiss Medical Weekly 150, w20336–w20336 (2020).

- Iglesias, S. et al. Hierarchical Prediction Errors in Midbrain and Basal Forebrain during Sensory Learning. Neuron 101, 1196–1201 (2019).

- Marcus, A. Doing the right thing: Psychology researchers retract paper three days after learning of coding error. Retraction Watch https://retractionwatch.com/2019/08/13/doing-the-right-thing-psychology-researchers-retract-paper-three-days-after-learning-of-coding-error/ (2019).

- Dolk, T., Freigang, C., Bogon, J. & Dreisbach, G. RETRACTED: Auditory (dis-)fluency triggers sequential processing adjustments. Acta Psychologica 191, 69–75 (2018).

- Henson, K. E. et al. RETRACTED: Inferring the Effects of Cancer Treatment: Divergent Results From Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group Meta-Analyses of Randomized Trials and Observational Data From SEER Registries. JCO 34, 803–809 (2016).

- In Sickness and in Health? Physical Illness as a Risk Factor for Marital Dissolution in Later Life - Amelia Karraker, Kenzie Latham, 2015. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0022146515596354.

- Mandhane, P. J. Notice of Retraction: Hahn LM, et al. Post–COVID-19 Condition in Children. JAMA Pediatrics. 2023;177(11):1226-1228. JAMA Pediatr 178, 1085–1086 (2024).

- Reinhart, C. & Rogoff, K. Errata: “Growth in A Time of Debt”. Harvard University https://carmenreinhart.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/36_data.pdf (2013).

- Wiegers, K. Humanizing Peer Reviews. https://web.archive.org/web/20060315135514/http://www.processimpact.com/articles/humanizing_reviews.html (2006).

- Atwood, J. Code Reviews: Just Do It. Coding Horror https://blog.codinghorror.com/code-reviews-just-do-it/ (2006).

- Miller, G. A Scientist’s Nightmare: Software Problem Leads to Five Retractions. Science 314, 1856–1857 (2006).

- MIT. The Missing Semester of Your CS Education. Missing Semester https://missing.csail.mit.edu/.

- Balaban, G., Grytten, I., Rand, K. D., Scheffer, L. & Sandve, G. K. Ten simple rules for quick and dirty scientific programming. PLOS Computational Biology 17, e1008549 (2021).

- Green, R. How To Write Unmaintainable Code. https://www.doc.ic.ac.uk/~susan/475/unmain.html.

- Motivation — Reproducible research documentation. https://coderefinery.github.io/reproducible-research/motivation/.

- Martin, R. C. Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship. (Pearson, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2008).

- Lynch, M. & published. Rules for Writing Software Tutorials. https://refactoringenglish.com/ (2025).

- Software Carpentry Lessons. Software Carpentry https://software-carpentry.org/lessons/.

- CodeRefinery. https://coderefinery.org/lessons/.

- UNIVERSE-HPC. Byte-sized RSE. UNIVERSE-HPC http://www.universe-hpc.ac.uk/events/byte-sized-rse/.

- Hastings, J., Haug, K. & Steinbeck, C. Ten recommendations for software engineering in research. GigaSci 3, 31 (2014).

- Lynch, M. How to Do Code Reviews Like a Human (Part One). https://mtlynch.io/human-code-reviews-1/ (2017).

- Lynch, M. How to Do Code Reviews Like a Human (Part Two). https://mtlynch.io/human-code-reviews-2/ (2017).

- Lynch, M. How to Make Your Code Reviewer Fall in Love with You. https://mtlynch.io/code-review-love/ (2020).

- Tatham, S. Code review antipatterns. https://www.chiark.greenend.org.uk/~sgtatham/quasiblog/code-review-antipatterns/ (2024).

- Ivimey-Cook, E. R. et al. Implementing code review in the scientific workflow: Insights from ecology and evolutionary biology. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 36, 1347–1356 (2023).

- Rokem, A. Ten simple rules for scientific code review. PLOS Computational Biology 20, e1012375 (2024).

- Vable, A. M., Diehl, S. F. & Glymour, M. M. Code Review as a Simple Trick to Enhance Reproducibility, Accelerate Learning, and Improve the Quality of Your Team’s Research. American Journal of Epidemiology 190, 2172–2177 (2021).

- Gee, T. What to Look for in a Code Review. (Leanpub, 2015).

- What to look for in a code review. eng-practices https://google.github.io/eng-practices/review/reviewer/looking-for.html.

- Common pitfalls and recommended practices. scikit-learn https://scikit-learn.org/stable/common_pitfalls.html.

- Barton, J. awesome-code-review. GitHub https://github.com/joho/awesome-code-review/blob/main/readme.md.

- Bennett, D., Silverstein, S. M. & Niv, Y. The Two Cultures of Computational Psychiatry. JAMA Psychiatry 76, 563 (2019).

- Breiman, L. Statistical Modeling: The Two Cultures (with comments and a rejoinder by the author). Statistical Science 16, 199–231 (2001).

- Nosek, B. A., Ebersole, C. R., DeHaven, A. C. & Mellor, D. T. The preregistration revolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, 2600–2606 (2018).

- Brodeur, A., Cook, N. M., Hartley, J. S. & Heyes, A. Do Pre-Registration and Pre-Analysis Plans Reduce p-Hacking and Publication Bias? https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/262738 (2022).

- Pornprasit, C. & Tantithamthavorn, C. Fine-tuning and prompt engineering for large language models-based code review automation. Information and Software Technology 175, 107523 (2024).

- Yu, Y. et al. Fine-Tuning Large Language Models to Improve Accuracy and Comprehensibility of Automated Code Review. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 34, 14:1-14:26 (2024).

- Haider, M. A., Mostofa, A. B., Mosaddek, S. S. B., Iqbal, A. & Ahmed, T. Prompting and Fine-tuning Large Language Models for Automated Code Review Comment Generation. Preprint at (2024). [CrossRef]

- Lu, J., Yu, L., Li, X., Yang, L. & Zuo, C. LLaMA-Reviewer: Advancing Code Review Automation with Large Language Models through Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning. in 2023 IEEE 34th International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering (ISSRE) 647–658 (2023). doi:10.1109/ISSRE59848.2023.00026.

- Kwon, S., Lee, S., Kim, T., Ryu, D. & Baik, J. Exploring LLM-based Automated Repairing of Ansible Script in Edge-Cloud Infrastructures. Journal of Web Engineering 889–912 (2023) doi:10.13052/jwe1540-9589.2263.

- Li, Z. et al. Automating code review activities by large-scale pre-training. in Proceedings of the 30th ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering 1035–1047 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2022). doi:10.1145/3540250.3549081.

- Fan, L. et al. Exploring the Capabilities of LLMs for Code Change Related Tasks. Preprint at (2024). [CrossRef]

- Martins, G. F., Firmino, E. C. M. & De Mello, V. P. The Use of Large Language Model in Code Review Automation: An Examination of Enforcing SOLID Principles. in Artificial Intelligence in HCI (eds Degen, H. & Ntoa, S.) 86–97 (Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2024). doi:10.1007/978-3-031-60615-1_6.

- Tang, X. et al. CodeAgent: Autonomous Communicative Agents for Code Review. in Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (eds Al-Onaizan, Y., Bansal, M. & Chen, Y.-N.) 11279–11313 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Miami, Florida, USA, 2024). doi:10.18653/v1/2024.emnlp-main.632.

- Zhao, Z. et al. The Right Prompts for the Job: Repair Code-Review Defects with Large Language Model. Preprint at (2023). [CrossRef]

- Gibney, E. AI tools are spotting errors in research papers: inside a growing movement. Nature (2025). [CrossRef]

- Krag, C. H. et al. Large language models for abstract screening in systematic- and scoping reviews: A diagnostic test accuracy study. 2024.10.01.24314702 Preprint at (2024). [CrossRef]

- Nashaat, M. & Miller, J. Towards Efficient Fine-Tuning of Language Models With Organizational Data for Automated Software Review. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 50, 2240–2253 (2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).