1. Introduction

Nursing is an essential pillar in health systems, playing a key role in the promotion, prevention, and comprehensive care of individuals. Its scope of practice ranges from individualized patient care to the design of public policies aimed at improving collective health [

1]. In this context, nursing professionals take on multiple roles: clinical, managerial, educational, and research-oriented [

2], in addition to actively participating in the formulation and implementation of health policies and programs in healthcare institutions [

3]. Nevertheless, their fundamental mission remains the management and direct provision of patient care [

4].

Scientific knowledge in health sciences has traditionally been associated with disciplines such as medicine, biology, and chemistry [

5]. However, in recent decades, there has been a significant increase in scientific production within the field of nursing [

6]. This progress seeks to address the issue highlighted by Gómez [

5], who warns that, in the absence of sufficient evidence, nursing decisions are often based on knowledge generated by other professions. Thus, nursing faces the ongoing challenge of developing its own body of scientific knowledge [

7], strengthening its professional autonomy and providing a solid foundation for clinical decision-making [

8].

Challenges in scientific production have established nursing as a robust and expanding science [

9,

10]. This achievement has been largely driven by the growth of research output, thereby strengthening its theoretical foundation. This progress also fosters the development of models and theories capable of describing, predicting, prescribing, and controlling phenomena inherent to the discipline [

11]. The scientific foundation of nursing lies in the integration between practical expertise and interdisciplinary knowledge [

12], where knowledge emerges from the synergy between theory and practice [

13]. The results of these investigations should not only contribute to improving professional practices but also offer concrete solutions to specific care-related problems [

4].

In the current context, evidence-based practice has become a fundamental pillar in nursing. This approach promotes the use of the best available information to optimize clinical outcomes and guide daily practice. It integrates the generation of evidence through research, its implementation in clinical settings, and its incorporation into professional education [

3,

14]. Professionals who base their decisions on scientific evidence act responsibly, strengthen the profession’s identity, and promote excellence through the continuous development of knowledge [

8].

Scientific research requires the application of rigorous methodologies, encompassing hypothesis formulation, study execution, and result interpretation [

15]. In nursing, as in other health sciences, it is crucial for research to uphold ethical principles and moral values inherent to the discipline [

2]. The application of bioethics is essential to ensuring good practices and scientific integrity [

16]. However, there are still cases in which these standards are not met due to either intentional or unintentional errors by researchers.

Like other sciences, nursing is not exempt from producing flawed literature, as evidenced in recent studies [

17,

18]. Defective literature can negatively impact the credibility and advancement of the discipline, as well as professional practice. For this reason, scientific retractions have become a fundamental tool for addressing this issue [

19]. These mechanisms allow for the removal of fraudulent publications or those containing significant errors that compromise the integrity of the literature [

20]. By alerting readers to unreliable results and conclusions—whether due to misconduct, plagiarism, ethical violations, or errors—retractions help maintain academic integrity [

21,

22].

In the health field, flawed literature can have serious effects on patient safety, influencing clinical decisions and increasing the risk of inappropriate treatments [

23,

24]. In nursing, this could compromise the quality of care in both prevention and treatment of health issues, which are fundamental objectives of research in the field [

4].

One of the main concerns in modern scientific practice is the shift in publication culture. The pressure to “publish or perish” has led to an increase in productivity but not necessarily in the credibility of publications [

25,

26,

27,

28]. While gaining recognition and incentives is legitimate [

2], these achievements should not come at the expense of academic integrity.

In recent years, interest has grown in understanding the motives and patterns behind retractions, particularly in the health sciences [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. However, in the field of nursing, studies remain limited [

38]. This research aims to analyze retractions in nursing publications worldwide, examining their temporal evolution, main patterns and causes, authors’ countries of origin, and the time to retraction.

2. Materials and Methods

The data collection was carried out using the RetractionWatch (RW) database, downloaded from Crossref. This source was selected because it is publicly accessible [

31] and is recognized as the most comprehensive and far-reaching in the field of scientific retractions [

36,

37].

From RW, all retracted articles in the health sciences field up to October 15, 2024, were collected. A specific filter was then applied to identify the retractions corresponding to the nursing field. A total of 408 documents were retrieved, from which the following variables were extracted: i) journal of publication; ii) publication date; iii) retraction date; iv) authors; v) institutional affiliations; vi) country of the institutions; vii) reasons for retraction.

The information for each retracted article was tabulated, including the following variables: i) year of publication; ii) year of retraction; iii) origin of the research; iv) reasons for retraction; v) time to retraction (days, months, and years); vi) number of patients participating in the studies.

Additionally, complementary information was gathered from other sources. To determine the journal quartile, the Scimago Journal Rank was used, assigning the quartile corresponding to the document’s year of publication. The number of citations per document was obtained from Google Scholar, due to its broader coverage compared to other databases [

39].

Citations before retraction were counted retrospectively up to the year of retraction, while post-retraction citations included those produced from the first year following the document’s retraction.

A refinement process was then carried out to filter retraction reasons, eliminating causes not attributable to errors in the article (e.g., third-party investigations, journal or editorial decisions, and articles withdrawn and replaced). Retractions labeled as "withdrawn" mostly corresponded to systematic reviews removed due to lack of interest or the authors’ inability to update them. In response, a new retraction category was created, named “outdated review.”

Subsequently, a categorization process was performed, grouping retraction reasons into three main categories:

Misconduct: Includes cases of plagiarism, article duplication, lack of informed consent, fake peer review, random content generation, falsification, fabrication, and manipulation of images, data, and/or results, among others.

Unintentional error: Includes errors in methods, analysis, text, conclusions, and/or results, among others.

Other reasons: Includes journal or editor errors, outdated reviews, and copyright-related issues.

3. Results

3.1. Evolution of Retractions

The RetractionWatch (RW) database records a total of 52,990 retractions of scientific publications, of which 16,210 (30.6%) correspond to disciplines related to health sciences. Within this group, 2.5% of the retractions specifically belong to the nursing discipline [

40].

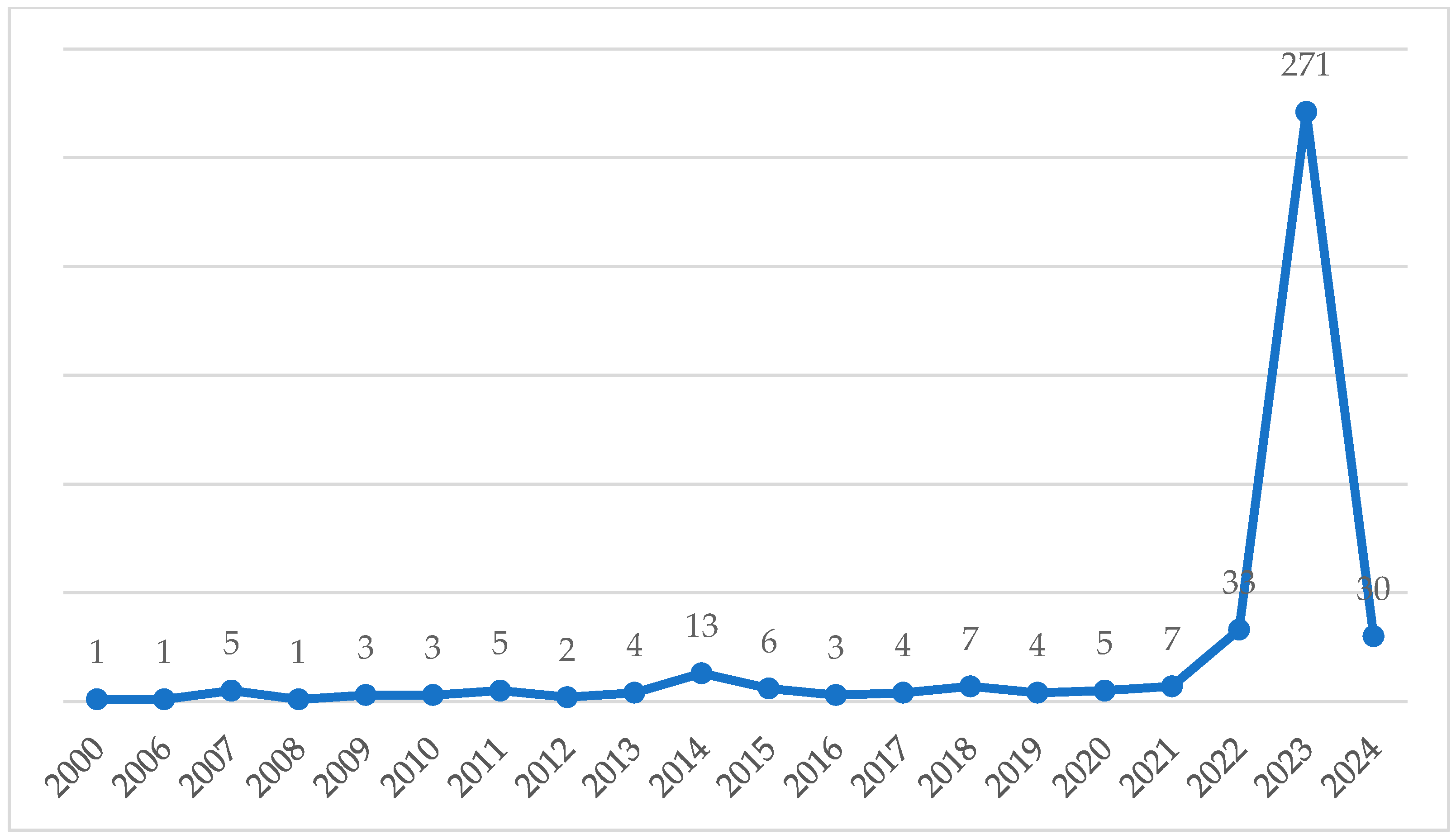

Over the past 25 years (2000-2024), a total of 408 documents in the nursing field have been retracted. A notable concentration of retractions is observed in the 2020-2024 period, during which 346 documents were withdrawn, representing 84.8% of the total (

Figure 1).

The trend peaked in 2023, with 271 retractions. This increase was largely influenced by a massive cleanup carried out by the Hindawi publishing house between 2022 and 2023, during which more than 8,000 publications were retracted, 254 of which belonged to the nursing field [

41].

The increase from 2022 onwards is due to the influence of the Hindawi publishing house. In 2022, 60.7% of retractions were associated with this publisher, in 2023, 94%, and in 2024, 70%.

3.2. Characteristics of the Documents and Sources of Publication

Table 2 presents a list of the five journals with the highest number of identified retractions. A total of 69 publication sources were associated with the 408 retracted documents, with these five journals accounting for 56.7% of the retractions.

Notably, the journals Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, and Journal of Healthcare Engineering each had more than 60 retracted publications.

It is important to highlight that three of these five journals have been discontinued from the Scimago Journal Rank (SJR), reflecting potential issues with editorial quality. Furthermore, none of the five journals with the highest incidence of retracted articles are specific to the nursing field.

3.3. Reasons for Retractions

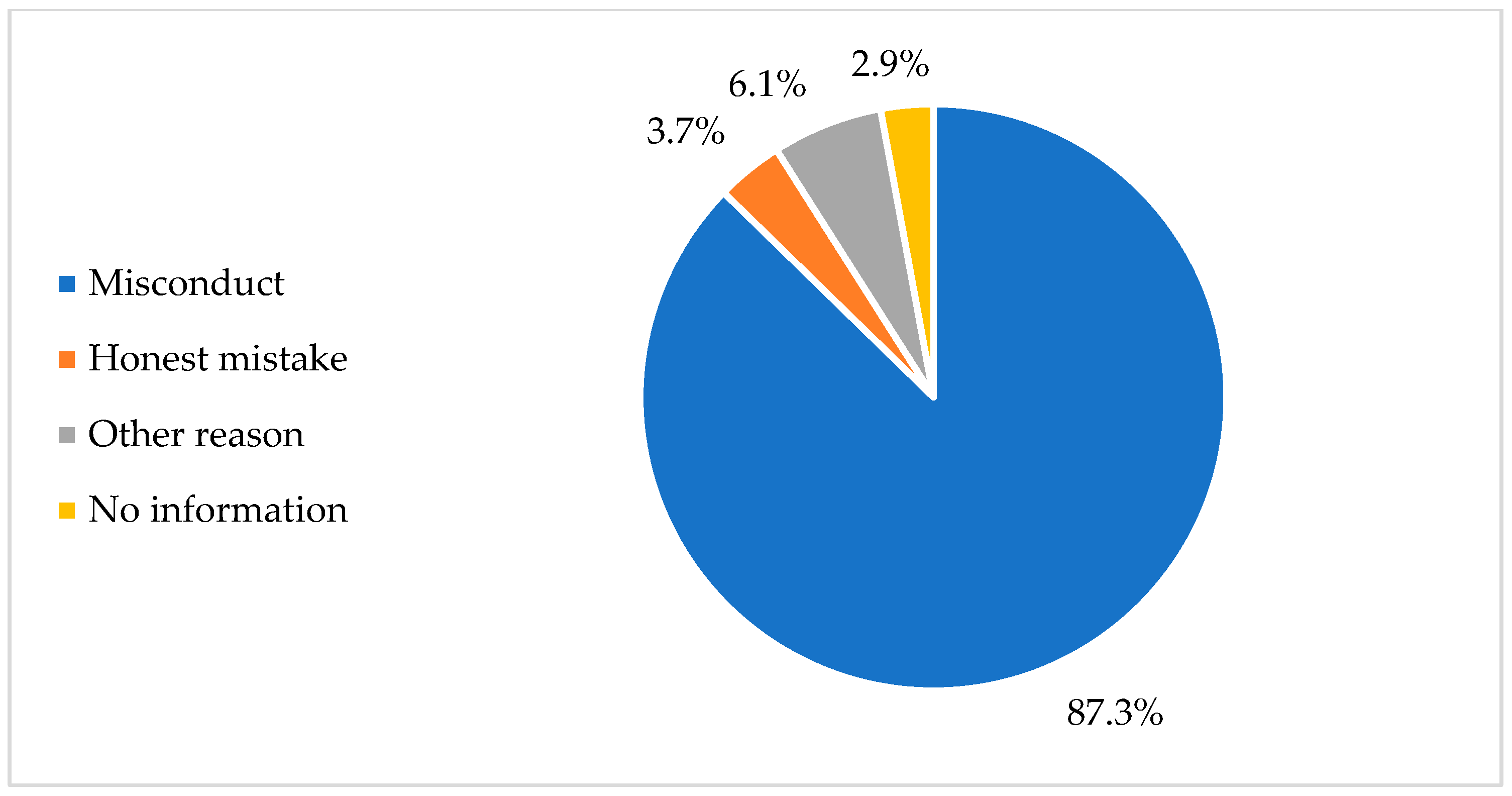

An analysis of scientific retractions in the field of nursing reveals a concerning reality: 87.3% of the documents were retracted due to scientific misconduct. This category includes serious issues such as plagiarism. data falsification. and other behaviors that compromise research integrity.

On the other hand. only 6.1% of retractions were related to honest errors. meaning unintentional mistakes that. while affecting the credibility of the results. did not stem from ethical violations. To a lesser extent. 3.7% of cases were attributed to other reasons. such as editorial errors or administrative issues.

However. there remains a group of 12 documents for which the reason for retraction was not disclosed. leaving open questions about the factors that led to their withdrawal (Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Retraction Rates of Documents by Category.

Figure 3.

Retraction Rates of Documents by Category.

The most striking aspect is that before the massive wave of retractions in 2023. the scenario was different: approximately 55% of retractions in the nursing field were due to scientific misconduct. While this figure is alarming. it represents a lower proportion compared to the impact of the mass retraction review conducted by some publishers in recent years.

This situation highlights the need to reflect on ethical practices in scientific publishing and to strengthen control and review mechanisms. not only to prevent unintentional errors but also to eradicate unethical practices that undermine trust in nursing research.

Table 3 presents a list of the 15 most common reasons for retraction. among which the most notable are concerns or issues with peer review. reported in 295 documents (74.5%); concerns or issues related to data. present in 271 documents; unreliable results. mentioned in 269 documents, and concerns or issues with references or attributions. observed in 266 publications.

3.4. Authorships

The analysis of retracted documents identified 1.552 authorship signatures. corresponding to a total of 1.434 distinct authors. The distribution of the number of authors per document reveals an interesting pattern: the largest proportion of articles (41.9%) had 2 to 3 authors. followed by those with 4 to 5 authors (29.7%). On the other hand. single-author documents accounted for 9.6%. while 18.8% of publications had more than 6 authors.

One particularly noteworthy aspect is the recurrence of certain authors. Among the 1.434 authors. 96 (6.7%) appeared repeatedly. meaning they were involved in more than one retraction. These authors collectively accounted for 214 authorship signatures. averaging 2.23 signatures per recurring author (

Table 4).

This phenomenon suggests the existence of a small but significant group of authors whose publications have been retracted multiple times. which could indicate problematic or persistent patterns of behavior within scientific production.

Table 5 presents an analysis of the 10 countries with the highest number of first authorships affiliated with institutions from these nations. China leads the ranking with an overwhelming 77.7% of first authorships, followed by the United Kingdom (3.2%) and the United States (2.2%), though with a significantly lower proportion.

In total, authors from 30 different countries were identified as first authors. However, only 4 Latin American countries appeared in this category, highlighting the low regional representation in terms of primary authorship in retracted documents.

3.5. Citation of Retracted Documents

Of the 408 analyzed documents, 388 (95.1%) have been cited, accumulating a total of 5,693 citations (

Table 6), which corresponds to an average of 13.95 citations per document. A closer look at these citations reveals an interesting pattern: 3,005 citations (52.8%) occurred before or during the year of retraction, while the remaining 47.2% took place at least one year after the retraction. This indicates that even after being withdrawn, these documents continued to circulate within scientific literature.

In fact, 60.3% of cited articles (234 documents) received post-retraction citations, raising concerns about the persistence of flawed knowledge. Regarding the distribution of these citations, a particular trend emerges: most documents received a relatively low number of citations, with 63.9% accumulating between 1 and 5 citations. Other documents had a greater impact: 16.8% were cited between 6 and 10 times, 8% received between 11 and 20 citations, 4.4% accumulated between 21 and 49 citations, and 3.6% recorded between 50 and 99 citations. Finally, 13 documents (3.4%) exceeded 100 citations, positioning themselves as highly referenced pieces despite their retraction.

These findings highlight a concerning phenomenon: the continued citation of retracted documents, which perpetuates the dissemination of flawed knowledge in scientific literature. This situation not only undermines scientific credibility but may also have direct consequences on knowledge advancement and professional practice, particularly in a field as sensitive as nursing.

3.6. Impact on Patients

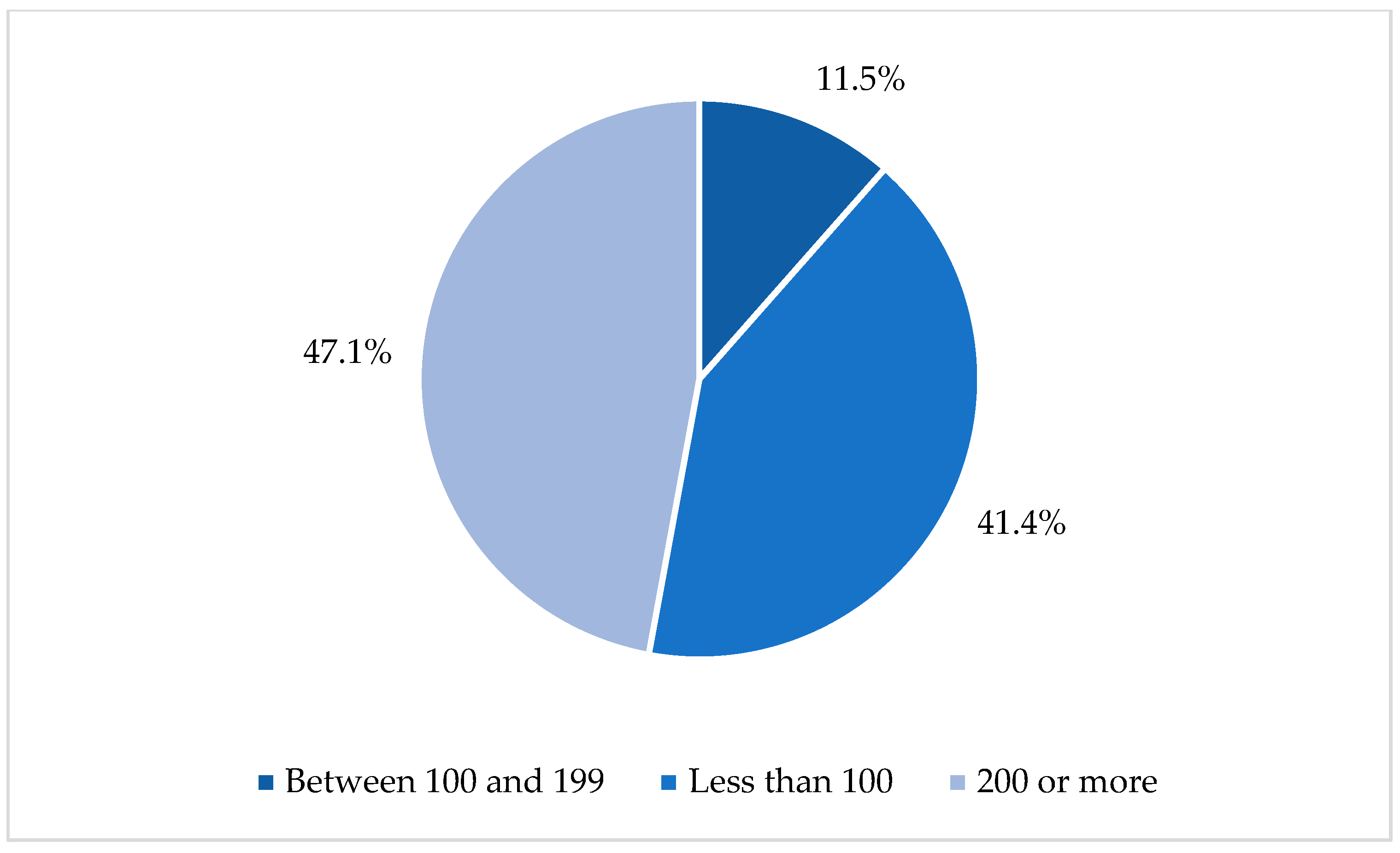

Of the 408 analyzed documents, more than half, 234 studies (57.4%), did not include patients in their research, indicating a predominance of studies without direct human participation. However, in the remaining 42.6%, human subjects were involved in the research.

Within this group, interesting patterns emerged regarding the magnitude of the samples: in 82 documents (47.1%), participation involved fewer than 100 patients; in 72 studies (41.4%), the number of participants ranged between 100 and 199. Finally, a smaller group of 20 studies reached higher figures, with more than 200 patients (

Figure 4).

This scenario reflects the diversity in the design and scope of studies in nursing, highlighting the variability in patient inclusion in retracted research, which raises questions about the quality and impact of these works within the scientific field.

The study titled "Data Analysis of Nursing Effects in Pediatric Gastroenterology Department under High Content Image Analysis Technology" stands out not only for its sample size but also for the ethical controversies that led to its retraction. With 2,465 participants, all under the age of 3 years, the study divided the children into two groups: the observation group, which received routine nursing care, and the control group, which was subjected to nest nursing and quality nursing [

42].

However, serious ethical irregularities emerged behind these findings. The study was retracted due to the lack of informed consent and the absence of approval from the institutional ethics review committee, two fundamental bioethical principles that ensure the dignity and safety of participants.

This case was not an isolated incident. In the overall analysis of the 174 studies involving human patients, bioethical violations were found to be concerning. In 69 studies (39.7%), there was no approval from the institutional ethics committee, while the lack of informed consent was the reason for retraction in 38 cases (21.8%). Additionally, in 31 documents (17.8%), retractions were linked to concerns regarding the well-being and integrity of human subjects.

3.7. Retraction Time

In the analysis of the 408 retracted documents, it was identified that 4 studies lacked information on the exact date of their retraction. Examining the remaining cases revealed interesting patterns regarding the time elapsed between publication and retraction. A total of 138 documents were retracted in less than a year after publication, while 214 studies had a retraction time of between 1 and less than 2 years. Additionally, 31 documents took between 2 and less than 5 years to be withdrawn, and 21 studies were retracted more than 5 years after their publication (

Table 7).

Exceptionally, 7 documents took more than 10 years to be retracted. The most extreme case corresponds to a study published in 1998 and retracted in 2014, with an interval of 15.79 years, making it the document with the longest recorded retraction time.

The overall average retraction time was 1.66 years, but notable differences were identified when broken down by retraction cause. Documents withdrawn due to misconduct had an average retraction time of 1.42 years, heavily influenced by the massive retractions of 2023. During this period, of the 271 retracted documents, 222 (81.9%) had been published just a year earlier, in 2022.

On the other hand, documents retracted due to honest errors had an average retraction time of 2.33 years, a longer period compared to misconduct cases. Finally, studies retracted for other reasons exhibited a significantly higher average of 5.17 years between publication and retraction.

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to analyze retractions in nursing, observing their evolution over time and describing their main characteristics. Globally, retractions in this discipline remain relatively low, accounting for only 2.5% of all health-related retractions. However, this number should not be underestimated, as recent years have seen a significant increase, particularly driven by events such as the mass retraction by Hindawi in 2023, where 254 documents were withdrawn due to scientific misconduct.

Our findings reveal that the majority of retracted documents correspond to research articles (69.6%) and clinical studies (20.6%). These publications were distributed across 69 different journals, 98% of which were indexed in the Scimago Journal Rank (SJR) at the time of publication. Notably, the highest rate of retractions originated from journals classified in the Q1 and Q2 quartiles (78%). This result contrasts with previous studies, such as that of Al-Ghareeb et al. [

17], which suggested a higher likelihood of retractions in lower-impact journals.

87% of the retractions identified in this study were due to scientific misconduct, a figure strongly influenced by the massive cleanup conducted by Hindawi in 2023. Specific causes included paper mills, peer review manipulation, randomly generated content, and lack of informed consent. Prior to this event, misconduct already accounted for a concerning 55% of nursing-related retractions, a finding consistent with previous studies, which reported similar figures: 68% [

18] and 69% [

31].

This situation is alarming, especially considering that in health sciences, and particularly nursing, professionals rely on academic literature as a source of evidence for clinical decision-making. Inaccurate findings not only compromise clinical practice but also put patient safety at risk.

When analyzing the country affiliation of first authorships, China led with 77% of cases, a finding that aligns with Al-Ghareeb et al. [

17], who reported that 31% of corresponding authors in retracted nursing and obstetrics papers were affiliated with Chinese institutions. These data align with other studies in health sciences, which highlight China’s significant challenges concerning the integrity of its scientific publications [

15,

43,

44,

45]. Additionally, various studies emphasize that China faces a particularly significant issue regarding the retraction phenomenon [

46].

Regarding retraction time, we found interesting results. While previous studies suggested that misconduct-related retractions tend to take longer, in our research, the "other reasons" category had the longest retraction times, largely influenced by outdated Cochrane reviews, which may be withdrawn after 5.5 years of inactivity [

47]. The overall average retraction time was 1.66 years, a figure lower than that reported by Al-Ghareeb et al., but higher than the 12-month average found by Joaquim et al. [

18] and very similar to the 1.89 years reported by Nicoll et al. [

38].

The time it takes for an article to be retracted has important implications. The longer a flawed study remains active, the higher the likelihood of it being cited in later publications or applied in clinical practice. Our data show that documents retracted after more than 5 years accumulated an average of 57 post-retraction citations, whereas those withdrawn between 2 and 5 years had 13 citations, and those retracted within less than 2 years received an average of 3.2 citations.

Finally, to assess patient impact, we conducted an analysis similar to Steen [

23], who found that 9,189 patients participated in retracted primary studies, and 70,501 patients were involved in secondary studies. In our study on nursing retractions, we identified 21,369 patients who participated in 164 retracted studies, with an average of 130 patients per document. While this figure reflects the direct impact on participants in flawed studies, its reach extends further when nursing professionals apply erroneous evidence in patient care, potentially leading to serious health consequences.

5. Conclusions

Research plays a fundamental role in a professional discipline like nursing, as its primary purpose is to guide care practices based on reliable scientific evidence. For this reason, it is imperative that knowledge production in this field strictly adheres to bioethical principles and maintains the highest methodological rigor, not only to ensure the validity of results but also to prevent unintentional errors that could negatively impact professional practice.

However, the increase in the number of retractions observed in nursing suggests the presence of patterns similar to those identified in other health sciences disciplines. This sustained rise not only reflects issues in scientific production but also highlights retraction reasons that are mostly linked to ethical misconduct and a lack of scientific integrity.

Given this reality, the implementation of alert measures aimed at nursing professionals, researchers, and students is urgently needed. The first is to question the available evidence, verifying it through other studies or literature reviews. The second is to strengthen ethical and methodological training, as well as develop effective practices that prevent flawed decision-making in patient care

If these actions are not carried out, the consequences could be severe: the use of flawed evidence in healthcare directly endangers patients, compromising the quality of care and trust in professional practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization. María Contreras-Muñoz, Cristian Zahn-Muñoz, Elizabeth Solís-Albanese, and Ezequiel Martínez-Rojas.; Methodology. Cristian Zahn-Muñoz and Ezequiel Martínez-Rojas.; Software. Cristian Zahn-Muñoz.; formal analysis. Cristian Zahn-Muñoz.; writing—original draft preparation. María Contreras-Muñoz and Cristian Zahn-Muñoz.; writing—review and editing. Ezequiel Martínez-Rojas. Visualization. Ezequiel Martínez-Rojas and Elizabeth Solís-Albanese.; supervision. Cristian Zahn-Muñoz.; project administration. Ezequiel Martínez-Rojas. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. Study does not involve humans.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Public Involvement Statement

No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This article was written following the PRIBA guidelines for Reporting of bibliometric studies.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

An artificial intelligence tool specialized in translation was used to grammatically check the English.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guía-Yanes MA. Enfermería: evolución, arte, disciplina, ciencia y profesión. revistavive [Internet]. 2019;2(4): 33-41.

- Alejos M, Vargas M. Bioética y su aplicación en la investigación en enfermería; una visión reflexiva. Salud, Arte y Cuidado. 2023; 16(1): 35-38. [CrossRef]

- Benítez J. La importancia de la investigación en Enfermería. Enfermería Investiga. 2019; 5(1): 1-2.

- Castro M, Simian D. La Enfermería y la Investigación. Revista Médica Clínica Las Condes. 2018;29(3): 301-310. [CrossRef]

- Gómez A. La investigación en enfermería. Enferm Nefrol. 2017;20(1). [CrossRef]

- Gue J. Producción científica de la enfermería. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem. 2009 ;62(6): 809.

- Triviño Z, Sanhueza O. Paradigmas de Investigación en Enfermería. Ciencia y Enfermería. 2005;XI(1): 17-24. [CrossRef]

- Fain J. Reading, Understanding and Applying Nursing Research. Quinta. Estados Unidos: F. A. Davis Company; 2024.

- Amezcua M. ¿Por qué afirmamos que la Enfermería es una disciplina consolidada? Index de Enfermería. 2018;27(4).

- Sanhueza-Alvarado OI. Código UNESCO para la disciplina de enfermería. Rev. iberoam. Educ. investi. Enferm. 2023;13(4): 4-6. [CrossRef]

- Medina I, Tafur J, Vigil M, Hernández R. La internacionalización y el desarrollo de la Enfermería como ciencia desde los intercambios científicos. Educación Médica Superior. 2018;32(4): 286-292.

- Palencia-Gutiérrez E, de la Rosa-Ferrera J, Rodríguez-Cepeda L. Evolución de la investigación en Enfermería en Ecuador desde su producción científica. Index de Enfermería. 2018;31(1). [CrossRef]

- Zárate R. La investigación un desafío para la enfermería en la Región de las Américas. Enfermería Universitaria. 2012;9(4): 4-8.

- Vélez, E. Investigación en Enfermería, fundamento de la disciplina. Revista de Administración Sanitaria. 2009;7(2): 341-356.

- Kocyigit BF, Akyol A, Zhaksylyk A, Seiil B, Yessirkepov M. Analysis of Retracted Publications in Medical Literature Due to Ethical Violations. J Korean Med Sci. 2023;38(40): e324. [CrossRef]

- Aldana G, Tovar B, Vargas Y, Nohora J. Formación bioética en enfermería desde la perspectiva de los docentes. Revista Latinoamericana de Bioética. 2020;20(2): 121-142. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghareeb A, Hillel S, McKenna L, Cleary M, Visentin D, Jones M, Bressington D, Gray R. Retraction of publications in nursing and midwifery research: a systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. (2018);81: 8–13. [CrossRef]

- Joaquim S, Longhini J, Palese A. What can we learn from retracted studies in the nursing field in the last 20 years? Findings from a scoping review. Acta Biomed. (2022);93(Suppl 2): e2022193. [CrossRef]

- Hasselmann F, Graf V, Schmidt M, Reinhart M. The visibility of scientific misconduct: A review of the literature on retracted journal Articles. Current Sociology Review. 2017;65(6): 814-845. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson Ch. y Brown N. Editorial: Retractions and their discontents. Current Psychology. 2024. [CrossRef]

- COPE. Guidelines. Retraction Guidelines. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Robazzi M, Valenzuela S. La retractación de las publicaciones científicas de enfermería. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem. 2023;31: e3920. [CrossRef]

- Steen G. Retractions in the medical literature: how can patients be protected from risk? Journal of Medical Ethics. 2012;38(4): 228-232. [CrossRef]

- Rapani A, Lombardi T, Berton F, Del Lupo V, Di Lenarda R, Stacchi C. Retracted publications and their citation in dental literature: A systematic review. 2020;6: 383–390. [CrossRef]

- Wray K, Andersen L. Retractions in Science. Scientometrics. 2018;117: 2009–2019. [CrossRef]

- Ghorbi A, Fazeli-Varzaneg M, Ghaderi-Azad E, Ausloos M, Kozak M. Retracted papers by Iranian authors: causes, journals, time lags, affiliations, collaborations. Scientometrics 2021;126: 7351–7371. [CrossRef]

- Brown S, Lund J. POP culture: the increasing perils of publish or perish. A farewell from the Editors in Chief. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2024;28(21). [CrossRef]

- Cakir A, Kuyurtar D, Balyer A. The effects of the publish or perish culture on publications in the field of educational administration in Türkiye. Social Sciences & Humanities Open. 2024;9: 100817. [CrossRef]

- Nair S. Yean C. Yoo J. Leff J. Delphin E, Adams M. Reasons for article retraction in anesthesiology: a comprehensive analysis, Can. J. Anaesth. 2019;67: 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Bozzo A. Bali K. Evaniew N. Ghert M. Retractions in cancer research: a systematic survey, Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2017;12: 2-5. [CrossRef]

- Zilberman T. Margalit I. Yahav D. Tau N. Retracted publications in infectious diseases and clinical microbiology literatura. 2023; 29(11): 1454.e1-1454.e3. [CrossRef]

- Dave L. Lipner S. Retractions of dermatology articles are uncommon in the Retraction Watch database 1994–2021. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315(8): 2459-2461. [CrossRef]

- Levett, J.J., Elkaim, L.M., Alotaibi, N.M. et al. Publication retraction in spine surgery: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2023;32: 3704–3712. [CrossRef]

- Kwee R. Kwee T. Retracted Publications in Medical Imaging Literature: an Analysis Using the Retraction Watch Database. Academic Radiology, 2023;30(6): 1148-1152. [CrossRef]

- Panahi S, Soleimanpour S. The landscape of the characteristics, citations, scientific, technological, and altmetrics impacts of retracted papers in hematology. Account Res. 2023;30(7): 363-378. [CrossRef]

- Dal-Ré R. Analysis of biomedical Spanish articles retracted between 1970 and 2018. 2019; 154(4): 125-130. [CrossRef]

- Freijedo-Farinas F, Ruano-Raviña A, Pérez-Ríos M, Ross J, Candal-Pedreira C. Biomedical retractions due to misconduct in Europe: characterization and trends in the last 20 years. Scientometrics. 2024; 129:2867–2882. [CrossRef]

- Nicoll LH, Carter-Templeton H, Oermann MH, Bailey HE, Owens JK, Wrigley J, Ledbetter LS. An examination of retracted articles in nursing literature. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2024;56(3): 478-485. [CrossRef]

- Santos-d´Amorim K, Ribeiro de Melo R, Coutinho Correia A, Fernandes M, Araújo da Silveira M. Retratados e ainda citados: perfil de citações pós-retratação em artigos de pesquisadores brasileiros. Em Questão. 2023;29:e-125494. [CrossRef]

- Retraction Watch. Repository Retraction Watch Database. 2024. Available online: https://gitlab.com/crossref/retraction-watch-data.

- RetractionWatch. Hindawi reveals process for retracting more than 8,000 paper mill Articles. 2023. Available online: https://retractionwatch.com/2023/12/19/ hindawi-reveals-process-for-retracting-more-than-8000-paper-mill-articles/.

- Yanli M, Liang H, Jin Y. (Retracted) Data Analysis of Nursing Effects in Pediatric Gastroenterology Department under High Content Image Analysis Technology. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2022;30: 4302331. [CrossRef]

- Dave L. Lipner S. Retractions of dermatology articles are uncommon in the Retraction Watch database 1994–2021. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315(8): 2459-2461. [CrossRef]

- Kwee R. Kwee T. Retracted Publications in Medical Imaging Literature: an Analysis Using the Retraction Watch Database. Academic Radiology. 2023;30(6): 1148-1152. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Ku JC, Alotaibi NM, Rutka J. Retraction of neurosurgical publications: A systematic review.. World Neurosurg 2017;103: 809-814.

- Yang W, Sun N, Song H. Analysis of the retraction papers in oncology field from Chinese scholars from 2013 to 2022. J Cancer Res Ther. 2024;20(2): 592-598. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmeyer B, Fonnes S, Andresen K, Rosenberg J. Use of inactive Cochrane reviews in academia: A citation analysis. Scientometrics. 2023;128: 2923-2934. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).