Introduction

Reptiles, particularly exotic pet snakes, are recognized carriers of

Salmonella spp. [

1]. While most infections in these reptiles are subclinical, they may occasionally lead to gastrointestinal disease in the host [

2]. Additionally, reptile-associated salmonellosis represents a significant zoonotic threat, particularly for children, elderly and immunocompromised individuals [

3,

4]. Reports of clinically relevant

Salmonella enterica group B infections in corn snakes

(Pantherophis guttatus) are rare, indicating the necessity for thorough documentation of such cases.

Case Description

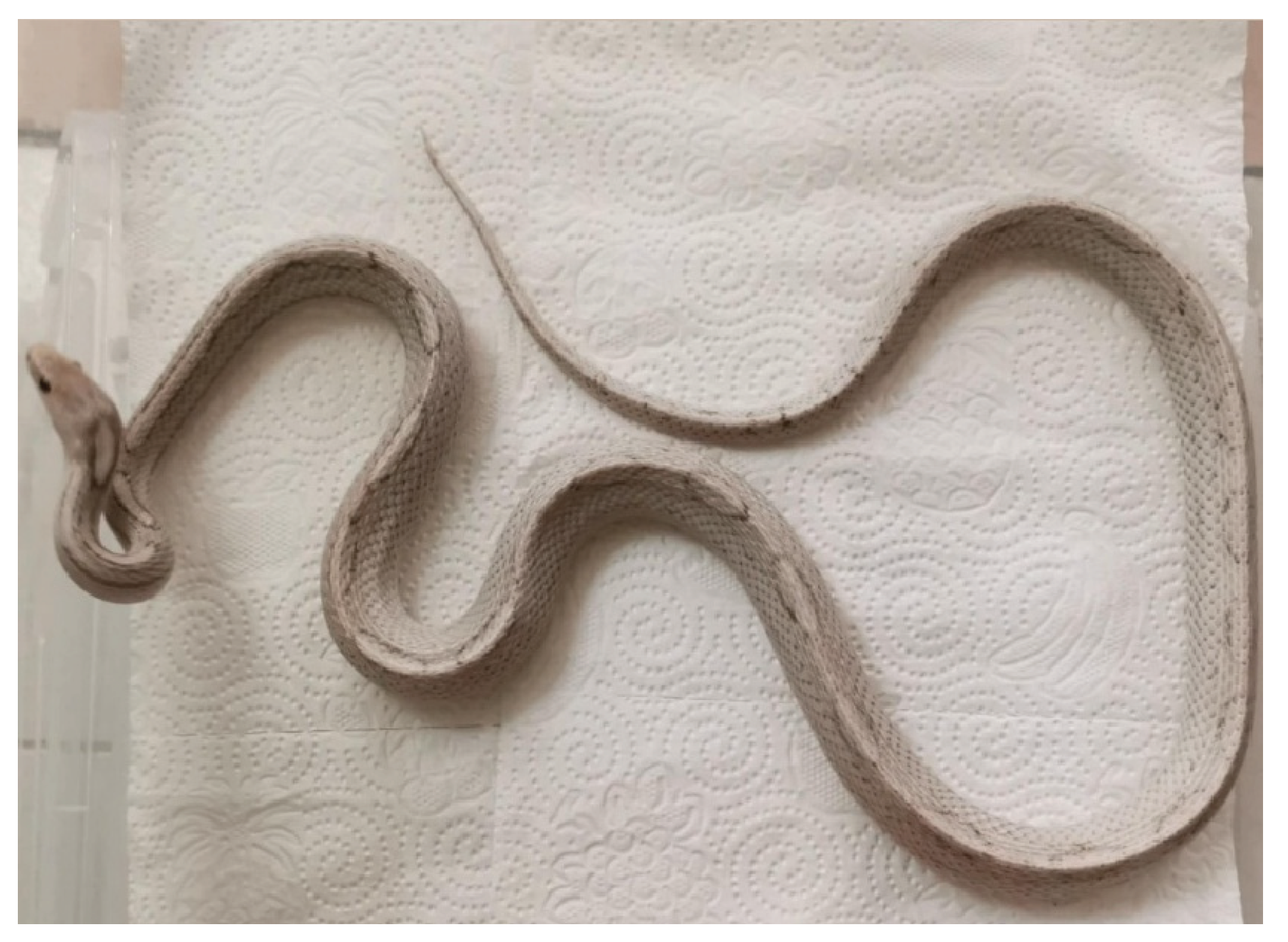

A 2-year-old female corn snake (P. guttatus), was adopted from a previous owner who could not care for it. The snake was maintained in a controlled environment within a terrarium (with enclosure size: 121.9 x 33.0 x 43.2 cm) that provided optimal temperature and humidity conditions, with no other snakes or animals present at the site. The snake was fed frozen/thawed mice at intervals of 10 to 14 days. Soon after being adopted, the snake stopped eating and lost a third of its weight within 50 days. The owners observe mushy feces, report that the snake prefers to hide and shows no interest in the food provided.

Clinical Examination

Clinical assessments were carried out, including measurements of body weight, evaluation of hydration status, and coelomic palpation to assess internal health. The clinical examination revealed lethargy, poor condition, weight of 550g, high-grade dehydration and tenderness on palpation of the abdominal wall. The snake tends to remain stationary during the examination, even when encouraged to move (

Figure 1).

Diagnostic Methods and Laboratory Findings

Fecal samples were collected from the cloaca using sterile swabs. Due to the inability to obtain larger amounts of feces during the examination, it was recommended to collect a larger sample after defecation for further testing, specifically for parasitological examination.

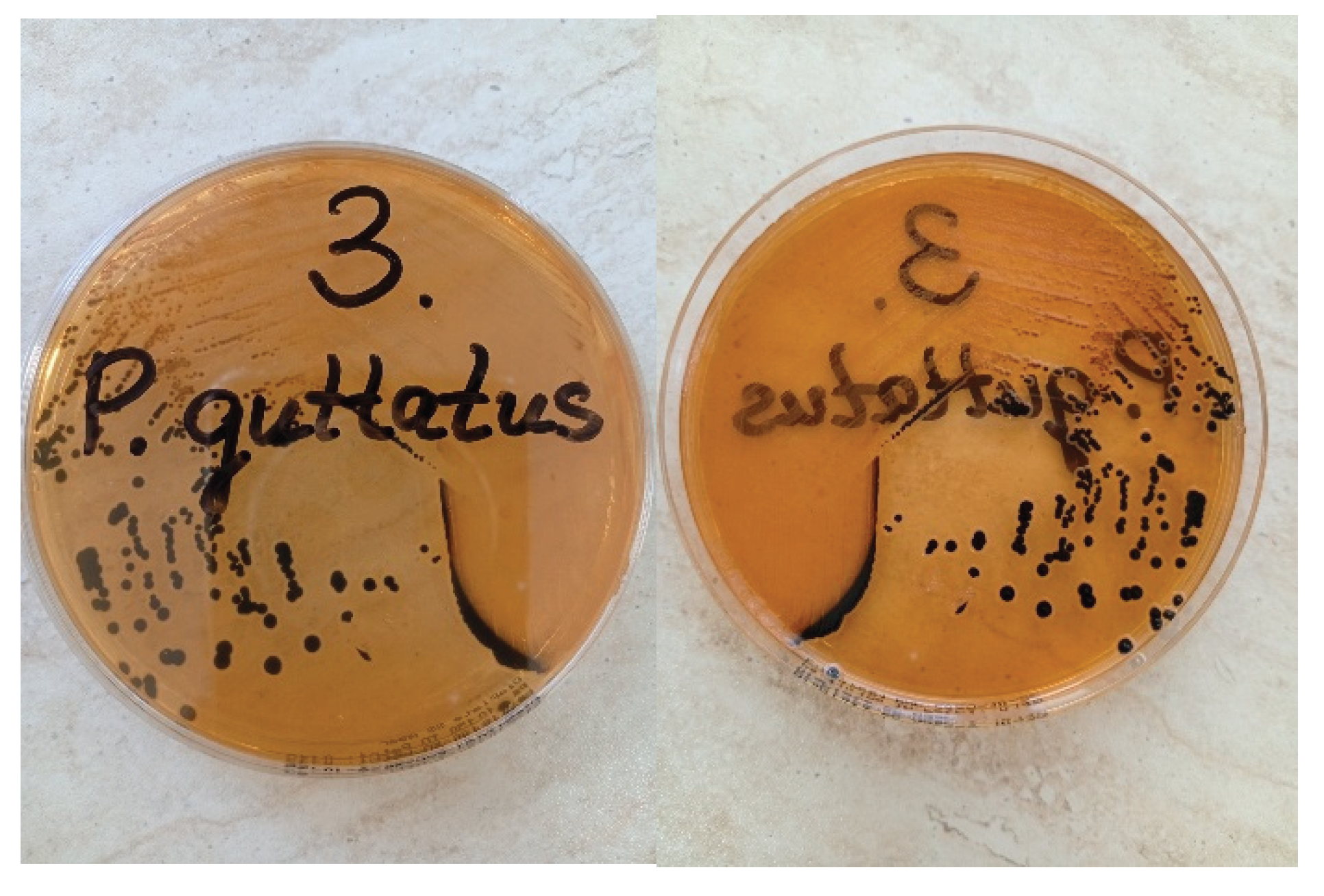

The swab samples were later inoculated for liquid enrichment, utilizing Tryptone Soya Broth (Soyabean Casein Digest Broth, HiMedia®) and Selenite Broth. After this, a loop is taken from the broth and streaked onto solid nutrient media (Blood Agar Base supplemented with 5% defibrinated ovine blood and MacConkey Agar, HiMedia®, India) using four-quadrant streak plate method [

5]. The process of incubation typically takes place at a controlled temperature of 37°C for a duration of 24 hours. Lactose-negative colonies on MacConkey agar were specifically examined for the possibility of being

Salmonella. After suspecting the presence of

Salmonella, the identified colonies were sent for further examination. They were transferred onto SS agar (HiMedia®, India) and incubated for 24 hours (

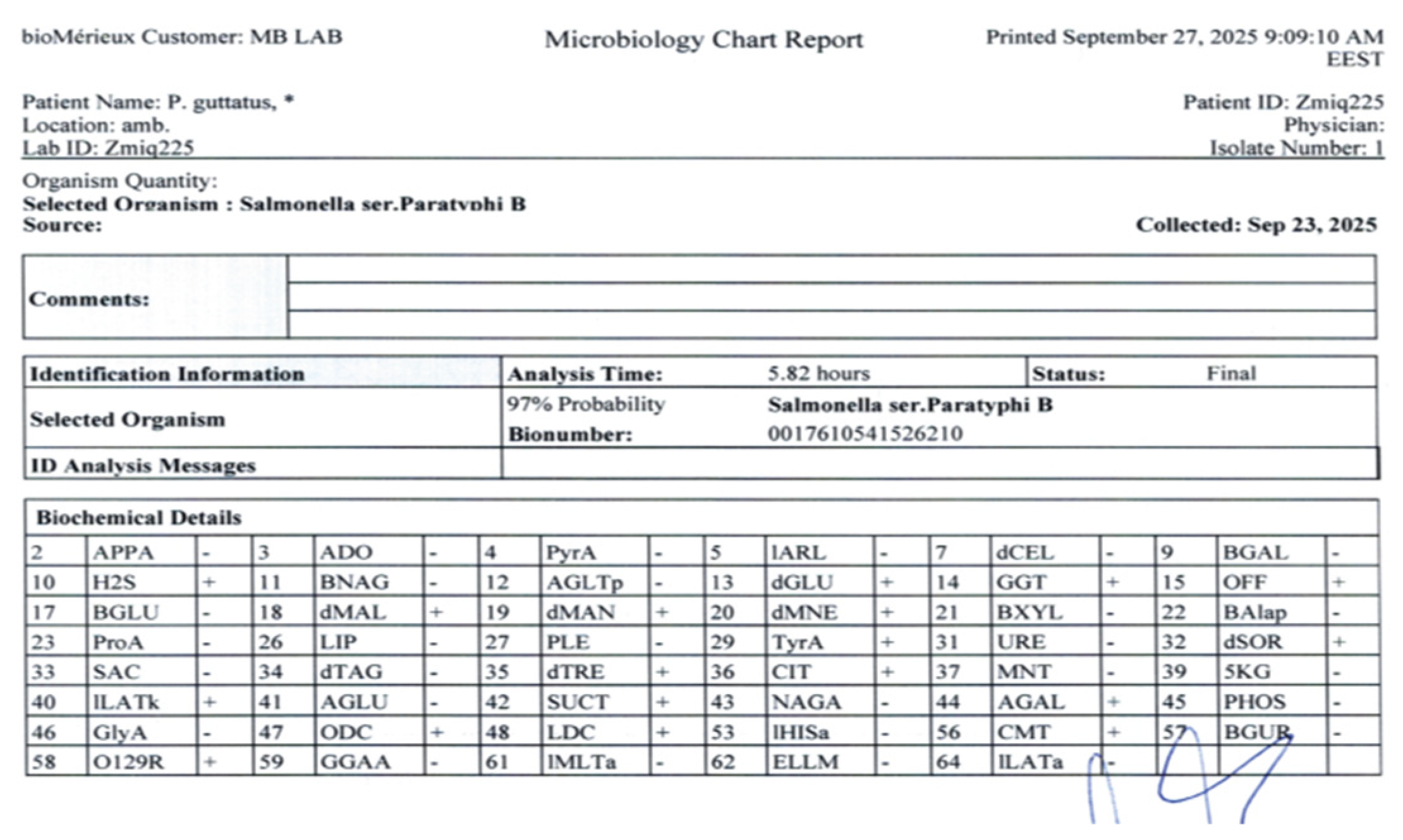

Figure 2). Following this step, single colonies that appeared colorless or transparent with black centers were subjected to automated biochemical profiling using the Vitek 2 Compact system (bioMérieux, France). Serological differentiation was conducted using serotyping methods according to the White-Kauffmann-Le Minor scheme [

6]. This process involves slide agglutination with specific sera for O- and H- antigens (Sifin Diagnostics, Berlin, Germany).

Results

The gastrointestinal tract interacts with the external environment, making it non-sterile. Initial bacterial isolation identified

Salmonella spp., E. coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Semi-quantitative assessment of different bacteria revealed confluent growth of

Salmonella spp. in the first three quadrants, characterized by overlapping colonies on the agar surface, while only single colonies were observed in the fourth quadrant. The other bacterial species were detected solely as single colonies. The Vitek 2 identification system confirmed

Salmonella enterica subsp.

enterica, serovar Parathyphi B, with probability of 97% [

7] (

Figure 3). This identification was further validated through slide agglutination techniques. The isolate was characterized as Salmonella enterica serotype O1,4,5,12:Hb:1,2, which is classified as

S. enterica serotype Paratyphi B according to the Kauffmann-White-Le Minor scheme.

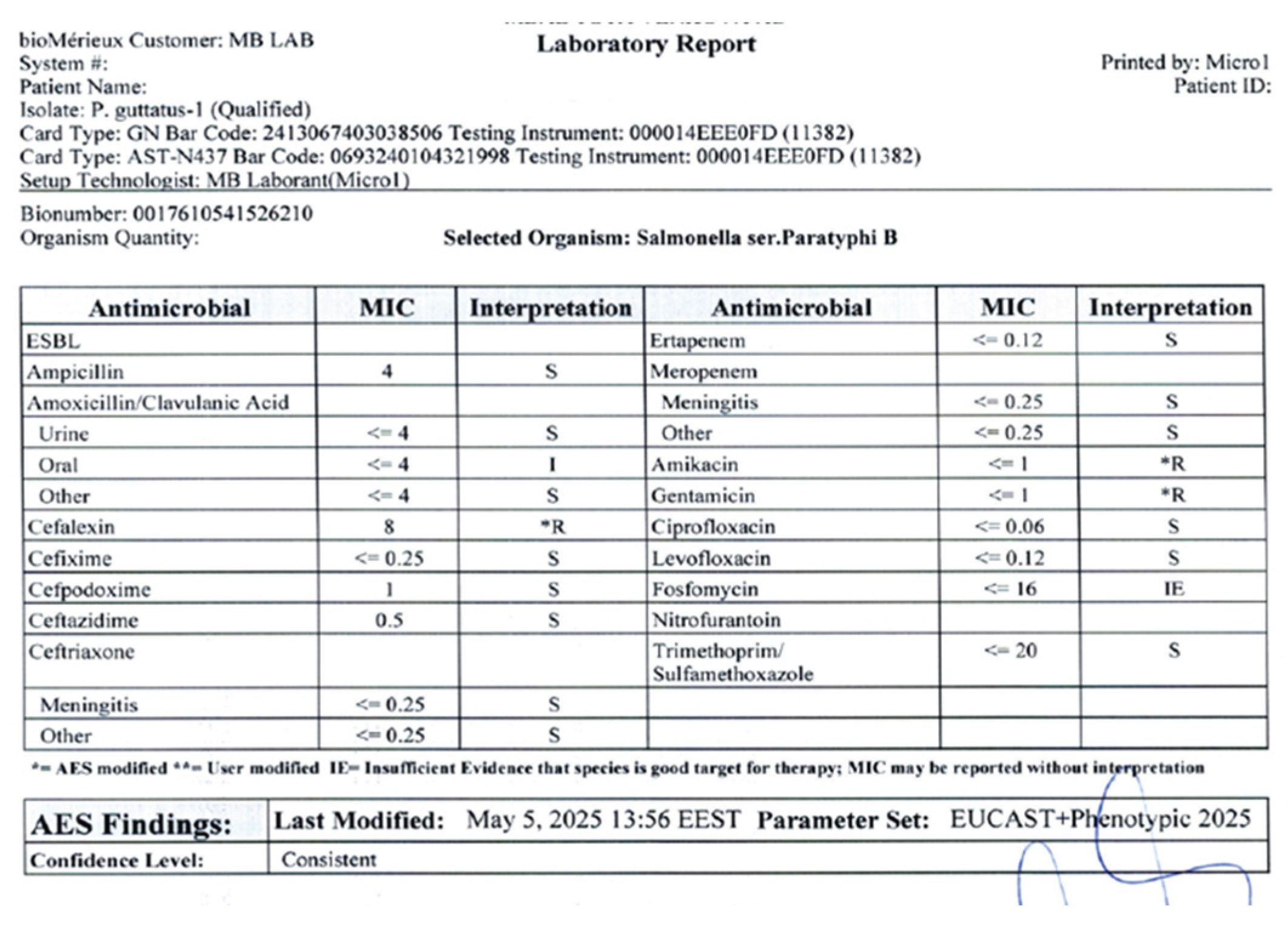

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was conducted using the Vitek 2 AST-GN panel, with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) interpreted according to CLSI standards. The antibiotics tested included ampicillin, amoxicillin/ clavulanic acid, cephalexin, cefixime, cefpodoxime, ceftazidime, ertapanem, amikacin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, fosfomycin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (

Figure 4).

Treatment

Supportive therapy included the administration of subcutaneous fluids, maintenance of temperature control, and probiotic supplementation. An antimicrobial treatment protocol was initiated using enrofloxacin at a dosage of 10 mg/kg, administered subcutaneously once daily. To increase safety and prevent transmission of bacteria to humans or other species, additional measures were recommended. These measures focused on emphasizing hygiene practices, consistent use of protective equipment, and thorough disinfection.

Outcome

Unfortunately, the snake was discovered deceased on day 3 following the initiation of treatment. A necropsy was not conducted due to the owner’s refusal.

To enhance safety and prevent the transmission of Salmonella to humans or other species, it was recommended to implement additional measures. These measures focus on emphasizing hygiene practices, the consistent use of protective equipment, and thorough disinfection protocols.

Discussion

This case highlights the clinical relevance of

Salmonella enterica group B infection in corn snake (

Pantherophis guttatus). Salmonellosis in snakes is often underreported, although reptiles are recognized carriers. The clinical picture of infection can vary, and signs are frequently nonspecific. Commonly associated conditions include septicaemia, pneumonia, enterocolitis, abscesses, and osteomyelitis. Clinical disease is relatively rare and is typically linked to factors such as stress, immunosuppression, or inadequate care practices [

1,

8,

9]. In this case, there is no evidence indicating that the snake was ill before its transfer to the new owner. Stressors such as transportation, acclimatization to a new environment, and exposure to unfamiliar noise and vibration (the new owners live on a high-traffic boulevard) may have contributed to its condition [

10]. In addition, the change in food supplier is notable. Numerous documented outbreaks have been associated with contaminated feeder rodents, which are recognized as a significant reservoir for various species of Salmonella [

11].

Genetic immunosuppression may contribute to the development of clinical diseases in corn snakes. Different morphs of corn snakes result from selectively breeding naturally occurring genetic mutations that produce various colors and patterns. Sometimes, breeders employ inbreeding to maintain these patterns. Although inbreeding in snakes generally causes fewer issues than in mammals, it can still lead to genetic problems and health issues, particularly with designer morphs [

12,

13].

The use of automated identification systems such as the Vitek 2 Compact represents a valuable diagnostic tool in exotic animal medicine [

14]. The Vitek 2 system provides rapid, standardized identification and antimicrobial susceptibility results within hours, which facilitates targeted therapeutic decisions [

7,

15]. In our case, the high-confidence identification of

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica, serogroup B, underscores the reliability of this system for reptile samples. Antimicrobial resistance among reptile-derived

Salmonella isolates has been reported worldwide. Resistance to amikacin, cefalexin and gentamicin, as detected here, is consistent with previous findings in both reptiles and feeder rodents [

16,

17]. This highlights the importance of culture-guided therapy, as empirical treatment may fail in the presence of resistant strains. Enrofloxacin and ceftazidime proved effective in this case, in line with reports recommending fluoroquinolones or third-generation cephalosporins for severe salmonellosis in reptiles [

5,

18,

19]. Nevertheless, antimicrobial therapy in reptiles should be judicious, given the risk of resistance selection and potential impacts on the microbiota. Despite evidence-based therapy, the outcome can be death, probably due to delayed intervention and severe organ damage caused by infection and prolonged starvation. Other authors have also described possible complications that result in sudden death [

20].

Serotype Paratyphi B of

Salmonella enterica is known to cause paratyphoid fever in humans. This illness is typically milder, shorter in duration, and less prone to severe complications compared to classic typhoid fever; however, it can still be serious particularly for young children under the age of 5, adults over 65, and individuals with weakened immune systems. The zoonotic implications of this finding must be emphasized. Corn snakes are increasingly popular as pets, and their close contact with humans, particularly children, poses a risk of transmission [

3,

4,

21].

This case highlights the importance of combining clinical, microbiological, and epidemiological approaches in the management of diseases associated with reptiles. Effective prevention relies on proper care, monitoring of feeder rodents, and educating owners, all of which are essential for reducing both animal morbidity and the risk of zoonotic diseases.

Ethical Considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from the owner for diagnostic testing and publication of this case report.

Conclusions

This case illustrates that corn snakes can develop clinical salmonellosis caused by Salmonella enterica group B. Furthermore, maintaining proper hygiene and practicing responsible pet management are essential to mitigating the risk of zoonotic transmission.

References

- Pees, M., Brockmann. Salmonella in reptiles: a review of occurrence, interactions, shedding and risk factors for human infections. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2023, 11, 1251036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zając, M. , Skarżyńska, M., Lalak, A., Kwit, R., Śmiałowska-Węglińska, A., Pasim, P.,... & Wasyl, D. Salmonella in captive reptiles and their environment—can we tame the dragon? Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bjelland, A. M. , Sandvik, L. M., Skarstein, M. M., Svendal, L., & Debenham, J. J. Prevalence of Salmonella serovars isolated from reptiles in Norwegian zoos. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 2020, 62, 3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meletiadis, A., Biolatti. Surveys on Exposure to Reptile-Associated Salmonellosis (RAS) in the Piedmont Region—Italy. Animals 2022, 12, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, ER. Aseptic laboratory techniques: plating methods. J Vis Exp JoVE 2012, 63, e3064. [Google Scholar]

- Grimont, P. A. , & Weill, F. X. Antigenic formulae of the Salmonella serovars. WHO collaborating centre for reference and research on Salmonella 2007, 9, 1–166. [Google Scholar]

- Funke, G., & Funke-Kissling. Evaluation of the new VITEK 2 card for identification of clinically relevant gram-negative rods. Journal of clinical microbiology (Sanders ER (2012) Aseptic laboratory techniques: plating methods. J Vis Exp JoVE 63:e3064). 2004, 42, 4067–4071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Claunch, N. M., Lind, C., Lutterschmidt, D. I., Moore, I. T., Neuman-Lee, L., Stahlschmidt, Z., ... & Penning, D. Stress ecology in snakes. editor Penning D. Snakes. Nova Science Publishers, Inc 2023, 415-478.

- Khan, H. A., Almalki. Antibiotic-resistant salmonellae in pet reptiles in Saudi Arabia. Microbiology Independent Research journal 2022, 9, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancera, K. F. light. In Health and welfare of captive reptiles; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 357–378. [Google Scholar]

- Basiouni, S., Rodriguez-Morales. Silent Carriers: The Role of Rodents in the Emergence of Zoonotic Bacterial Threats. Pathogens 2025, 14, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fankhauser, G., & Cumming, K. B. Snake hybridization: A case for intrabaraminic diversity. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism (Vol. 6, No. 1, p. 13). 2008.

- Clark, M. I., Hileman. Inbreeding reduces fitness in spatially structured populations of a threatened rattlesnake. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2025, 122, e2501745122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristina, R. T., Kocsis. Pathology and prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria: a study of 398 pet reptiles. Animals 2022, 12, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchens, S. R., Wang. Bridging classical methodologies in Salmonella investigation with modern technologies: A comprehensive review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwenzi, W., Chaukura. Insects, Rodents, and Pets as Reservoirs, Vectors, and Sentinels of Antimicrobial Resistance. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, C., Lorenzo-Rebenaque. Pet reptiles: a potential source of transmission of multidrug-resistant Salmonella. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2021, 7, 613718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedley, J., Whitehead. Antibiotic stewardship for reptiles. Journal of Small Animal Practice 2021, 62, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maugeri, G., Lychko. Identification and antibiotic-susceptibility profiling of infectious bacterial agents: a review of current and future trends. Biotechnology journal 2019, 14, 1700750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meletiadis, A., Romano. A case of food-borne salmonellosis in a corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus) after a feeder mouse meal. Animals 2024, 14, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasmans, F., Martel. Bacterial diseases of reptiles. Infectious diseases and Pathology of reptiles 2020, 705–794. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).