Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

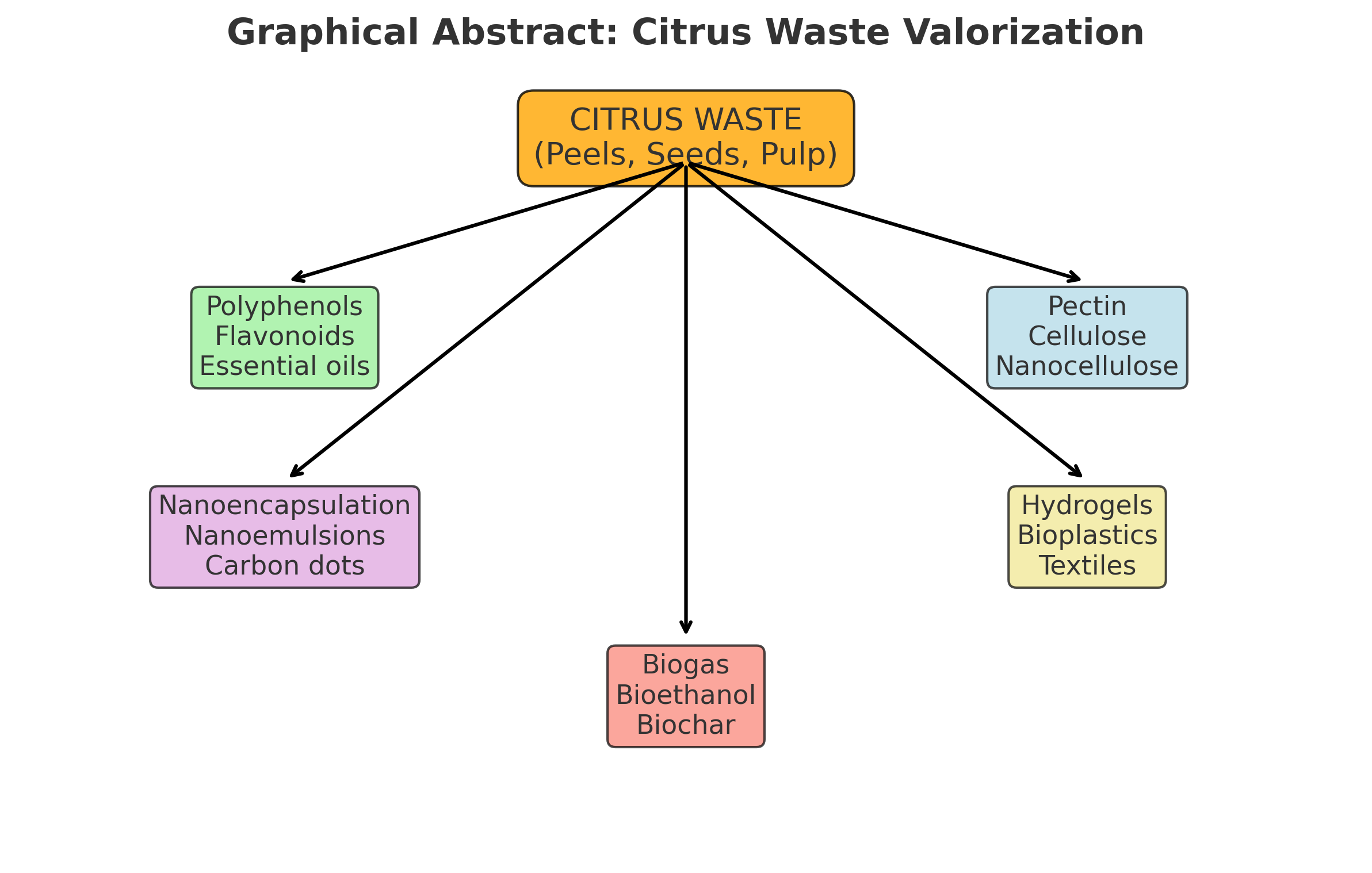

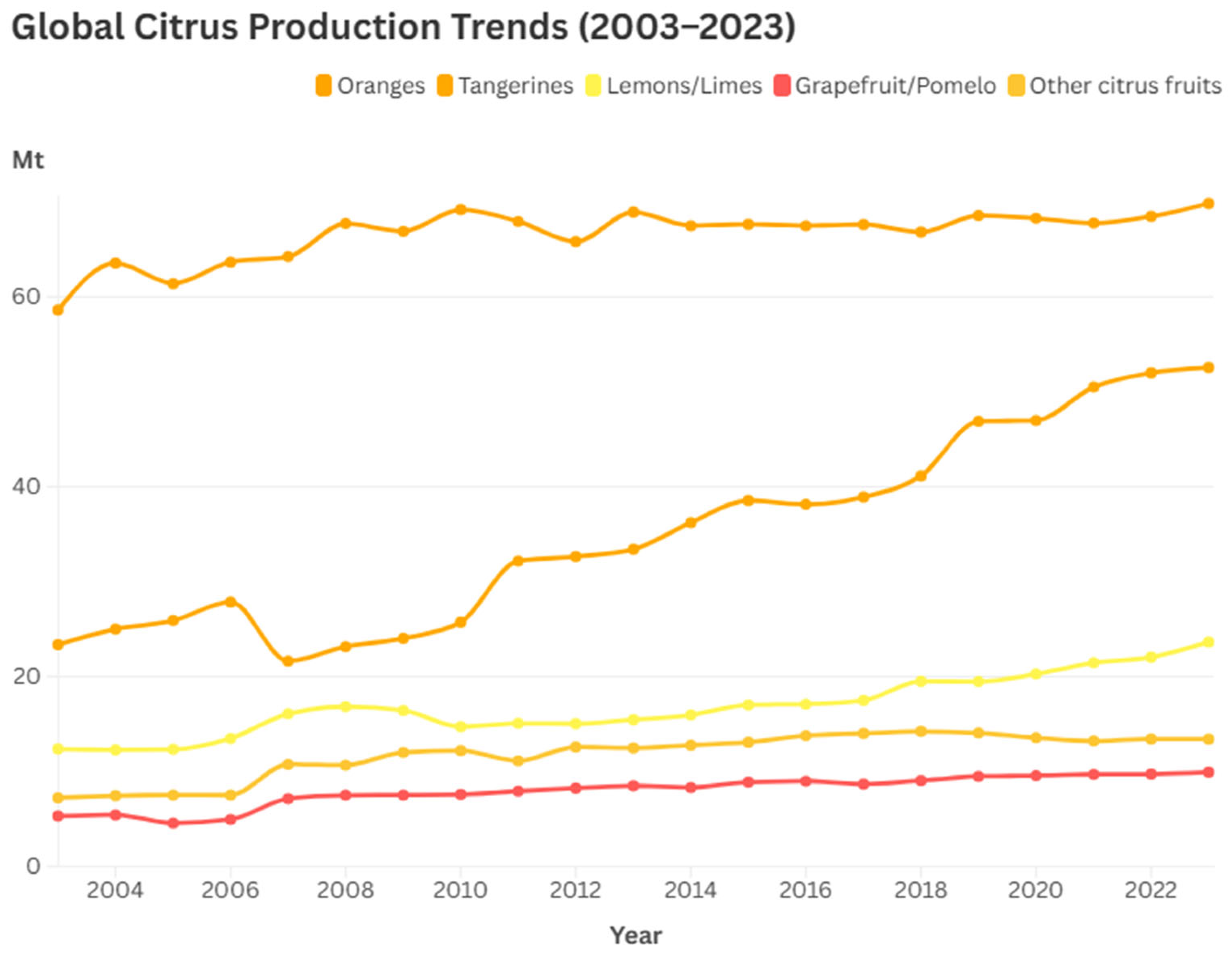

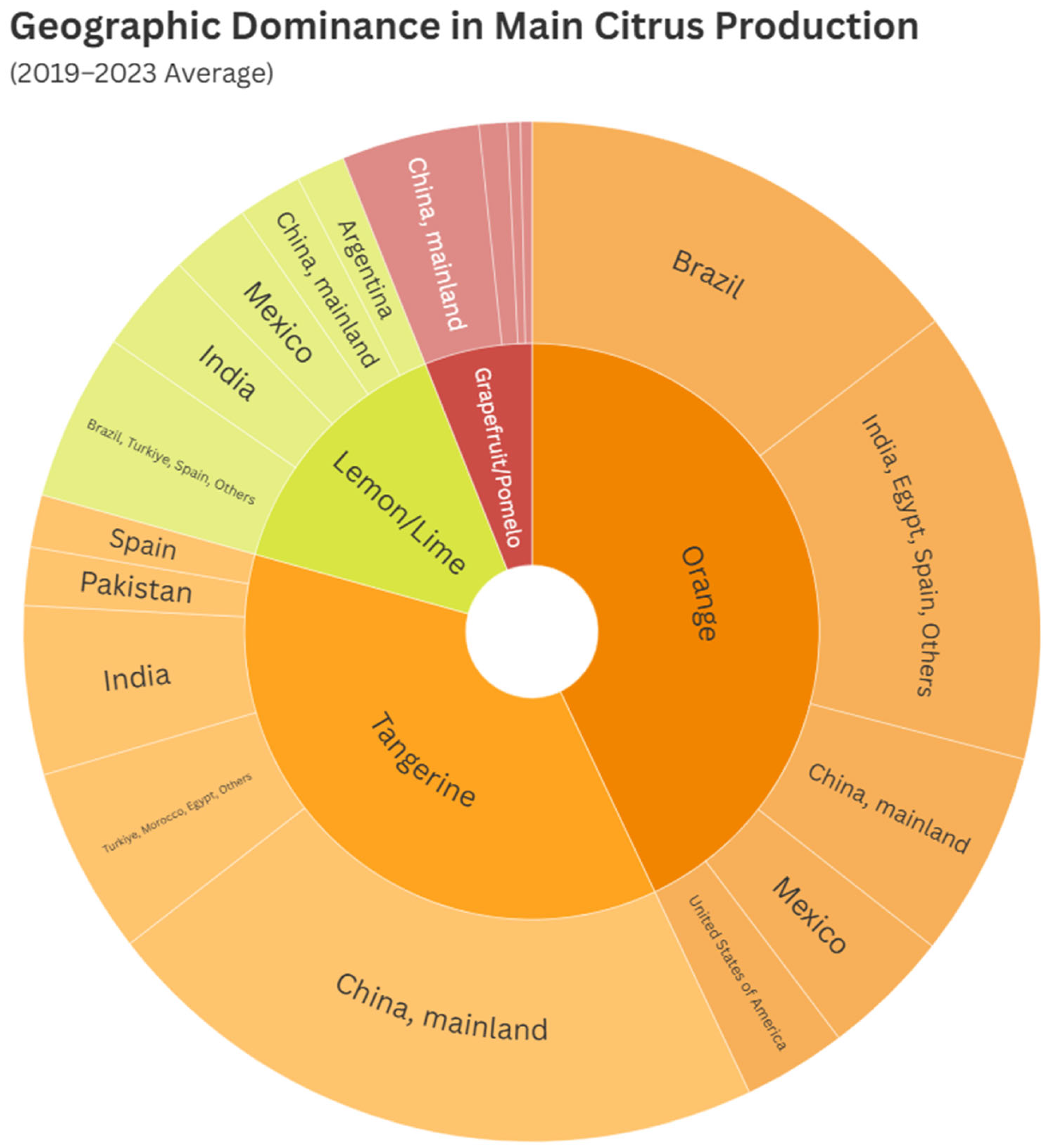

1.1. The Global Citrus Waste Challenge

1.2. Beyond Conventional Uses: The Need for Innovation

1.3. Objectives

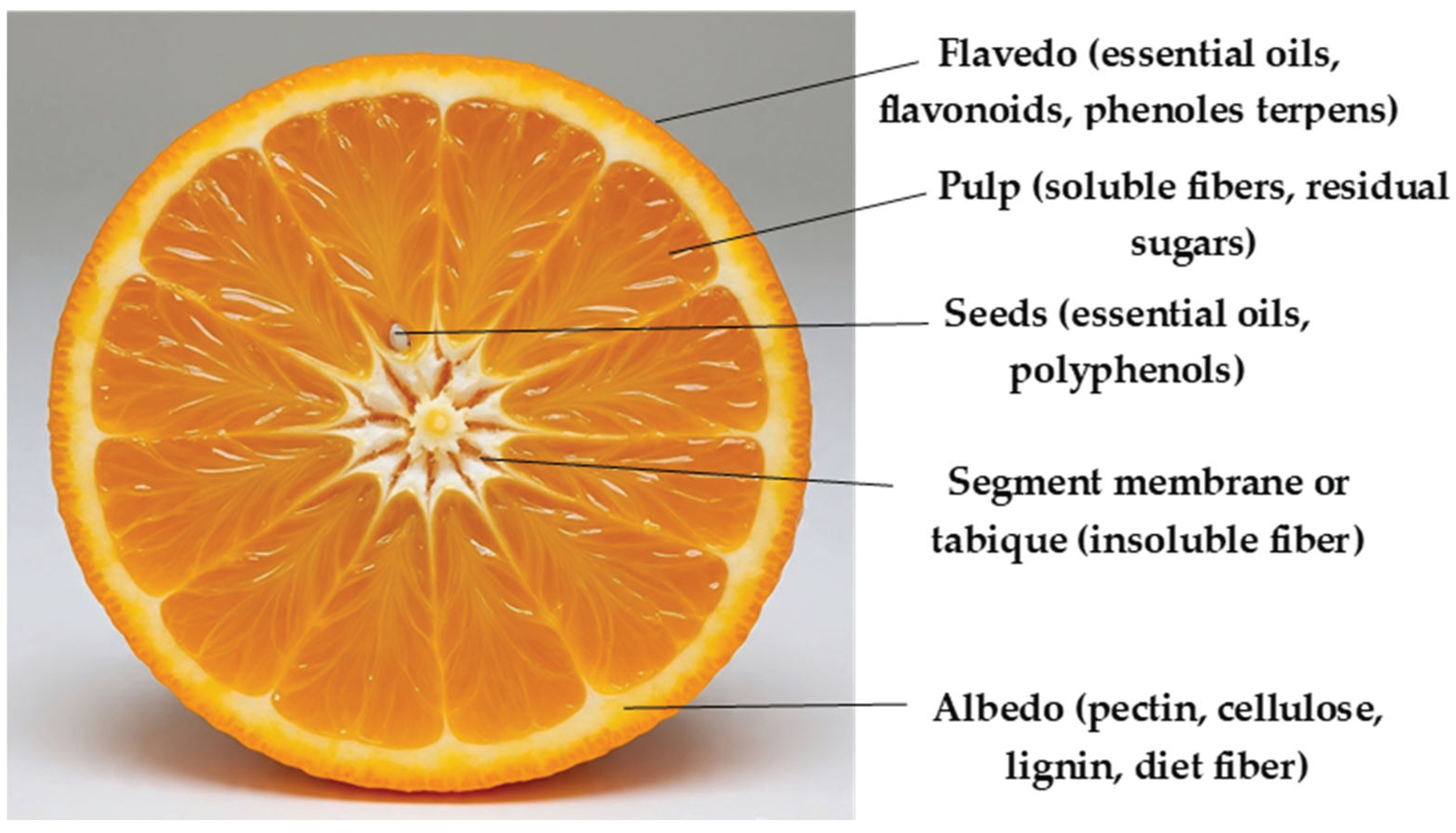

2. Citrus Waste Composition: A Treasure Trove of Bioactive Resources

2.1. Key Components by Waste Type

2.2. Comparative Analysis of Citrus Varieties

3. Emerging Extraction and Processing Technologies

3.1. Green Solvent Systems

3.2. Nanotechnology-Driven Approaches to Enhance Bioactive Compound Delivery

3.3. Biotechnological Innovations

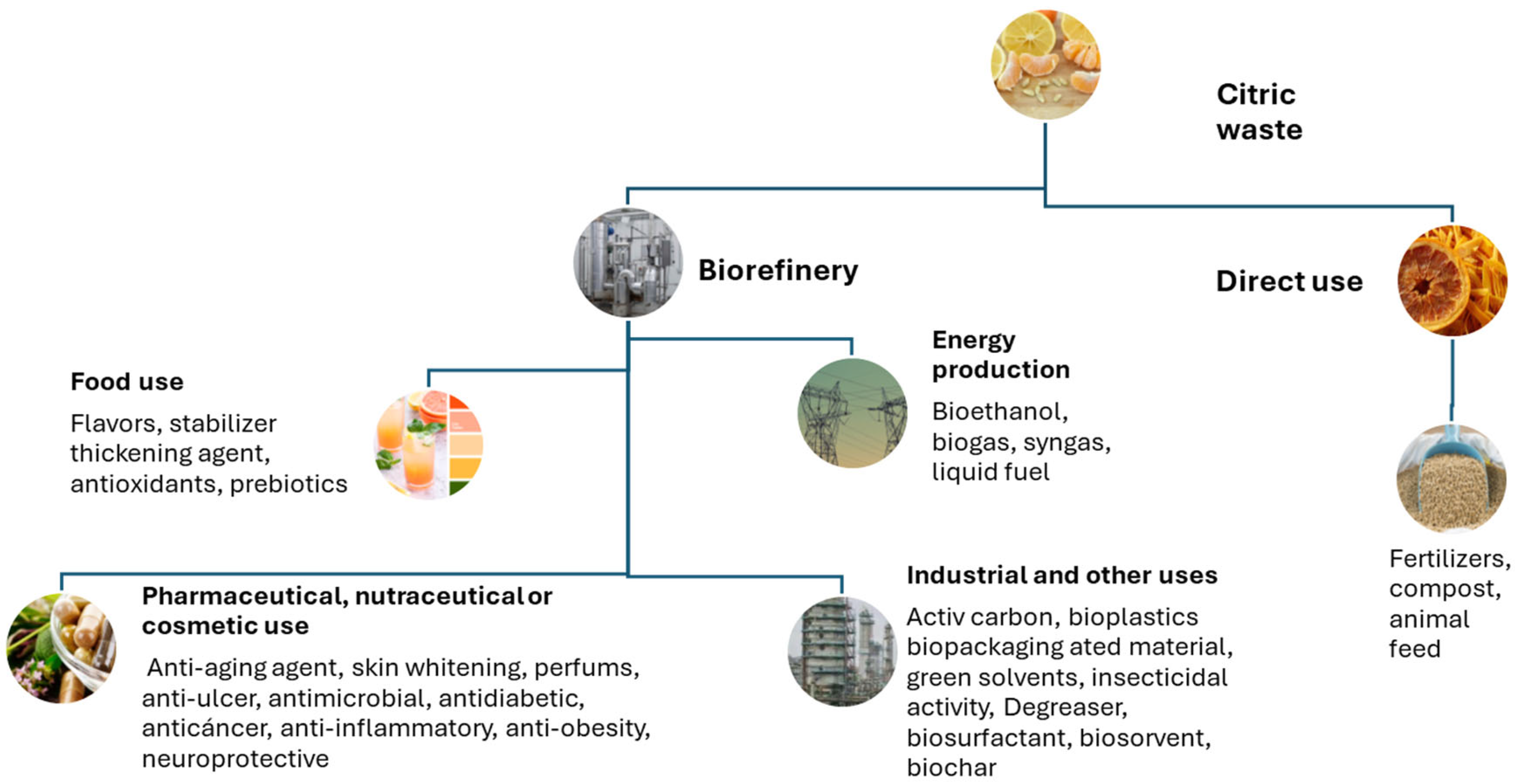

4. Less Conventional Applications: From Lab to Market

4.1. Citrus Waste Valorization: Bioactive Innovations for Health, Wellness, and Sustainable Food Systems

4.2. Advanced Biomaterials

4.3. Sustainable Consumer Goods

4.3.1. Citrus Fiber Composites in Sustainable Textiles

4.3.2. Limonene as a Green Solvent in Biodegradable Electronics

4.4. Agri-Tech Synergies

5. Challenges and Unresolved Issues

5.1. Technical Barriers

5.1.1. Seasonal Variability in Citrus Waste Composition

5.2. Economic and Regulatory Hurdles

5.2.1. High Costs of Green Extraction Methods

5.2.2. Lack of Standardized Regulations for Citrus-Derived Nanomaterials

5.3. Environmental and Social Trade-offs

5.3.1. Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) to Obtain Derivatives from Citrus Waste

5.3.2. Competition with Food-Grade Applications

5.4. Consumer Acceptance & Market Integration in Latin America

5.5. Public Policy & Regulatory Landscape in Latin America

6. Future Perspectives: Roadmaps for Sustainable Valorization

6.1. Integration with Circular Economy Models

6.2. Innovations in Materials Science

6.2.1. Advanced Hybrid Biomaterials

6.2.2 Catalytic Thermochemical Conversion

- Hydrogen-rich syngas (52–58%)

- Biochar (28–32%) suitable for soil remediation

- Phenolic oils (14–17%) as precursors for epoxy resins [6].

6.3. Cutting-Edge Research (2020–2024)

6.4. Emerging Trends and Knowledge Gaps

- Circular business models based on industrial symbiosis.

- Integration of biocatalytic processes for rapid and low-impact conversion.

- Industrial-scale nanocellulose production without generating toxic byproducts.

- Comprehensive long-term ecotoxicological assessments of citrus-derived nanomaterials and additives.

7. Conclusions

References

- FAO. CITRUS FRUIT FRESH AND PROCESSED Statistical bulletin 2020. 2020.

- Suri S, Singh A, Nema PK. Recent advances in valorization of citrus fruits processing waste: a way forward towards environmental sustainability. Vol. 30, Food Science and Biotechnology. The Korean Society of Food Science and Technology; 2021. p. 1601–26. [CrossRef]

- Satari B, Karimi K. Citrus processing wastes: Environmental impacts, recent advances, and future perspectives in total valorization. Vol. 129, Resources, Conservation and Recycling. Elsevier B.V.; 2018. p. 153–67. [CrossRef]

- English Alicia. The state of food and agriculture. 2019, Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2019. 156 p.

- Maqbool Z, Khalid W, Atiq HT, Koraqi H, Javaid Z, Alhag SK, Al-Shuraym LA, Bader DMD, Almarzuq M, Afifi M, AL-Farga A. Citrus Waste as Source of Bioactive Compounds: Extraction and Utilization in Health and Food Industry. Vol. 28, Molecules. MDPI; 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ciriminna R, Petri GL, Angellotti G, Fontananova E, Luque R, Pagliaro M. Nanocellulose and microcrystalline cellulose from citrus processing waste: A review. Int J Biol Macromol [Internet]. 2024 Nov;281:135865. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0141813024066741. [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAOSTAT Statistical Database [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL/visualize.

- Russo C, Maugeri A, Lombardo GE, Musumeci L, Barreca D, Rapisarda A, Cirmi S, Navarra M. The second life of citrus fruit waste: A valuable source of bioactive compounds†. Vol. 26, Molecules. MDPI; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Y, Cao X bing, Liu J meng, Yu Q qin, Zhang Q, He K bin. Agricultural fire impacts on brown carbon during different seasons in Northeast China. Science of the Total Environment. 2023 Sep 15;891.

- IQAir. World Live Air Quality Map [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.iqair.com/world-air-quality.

- Alpizar F;, Backhaus T;, Decker N, Eilks I, Escobar-Pemberthy N, Fantke P, Geiser K, Ivanova M, Jolliet O, Kim HS, Khisa K, Gundimeda H, Slunge D, Stec S, Tickner J, Tyrer D, Urho N, Visser R, Yarto M, Suzuki . . General rights UN Environment Global Chemicals Outlook II-From Legacies to Innovative Solutions: Implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. UN Environment Global Chemicals Outlook II-From Legacies to Innovative Solutions: Implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Citation. APA; 2019.

- Li J, Liang S, Liang X, Wang X, Bai X, Chen Y, Wu K, Liu X, Dong Z, Tan Q, Sun X, Hu C, Wu S. The carbon footprint and ecological costs of citrus production in China are going down. J Clean Prod. 2025 Mar 10;496. [CrossRef]

- Tayengwa T, Mapiye C. Citrus and winery wastes: Promising dietary supplements for sustainable ruminant animal nutrition, health, production, and meat quality. Vol. 10, Sustainability (Switzerland). MDPI; 2018. [CrossRef]

- Alnaimy A. Using of Citrus By-products in Farm Animals Feeding. Open Access Journal of Science. 2017 Sep 15;1(3). [CrossRef]

- Azizi M, Seidavi AR, Ragni M, Laudadio V, Tufarelli V. Practical applications of agricultural wastes in poultry feeding in Mediterranean and Middle East regions. Part 1: Citrus, grape, pomegranate and apple wastes. Worlds Poult Sci J. 2018 Sep 1;74(3):489–98. [CrossRef]

- Baker L, Bender J, Ferguson J, Rassler S, Pitta D, Chann S, Dou Z. Leveraging dairy cattle to upcycle culled citrus fruit for emission mitigation and resource co-benefits: A case study. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2024 Apr 1;203. [CrossRef]

- Andrianou C, Passadis K, Malamis D, Moustakas K, Mai S, Barampouti EM. Upcycled Animal Feed: Sustainable Solution to Orange Peels Waste. Sustainability (Switzerland). 2023 Feb 1;15(3). [CrossRef]

- Seidavi A, Zaker-Esteghamati H, Salem AZM. A review on practical applications of Citrus sinensis by-products and waste in poultry feeding. Vol. 94, Agroforestry Systems. Springer; 2020. p. 1581–9. [CrossRef]

- Kato-Noguchi H, Kato M. Pesticidal Activity of Citrus Fruits for the Development of Sustainable Fruit-Processing Waste Management and Agricultural Production. Vol. 14, Plants. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2025. [CrossRef]

- Consoli S, Caggia C, Russo N, Randazzo CL, Continella A, Modica G, Cacciola SO, Faino L, Reverberi M, Baglieri A, Puglisi I, Milani M, Longo Minnolo G, Barbagallo S. Sustainable Use of Citrus Waste as Organic Amendment in Orange Orchards. Sustainability (Switzerland). 2023 Feb 1;15(3). [CrossRef]

- Jeong D, Park H, Jang BK, Ju Y Bin, Shin MH, Oh EJ, Lee EJ, Kim SR. Recent advances in the biological valorization of citrus peel waste into fuels and chemicals. Vol. 323, Bioresource Technology. Elsevier Ltd; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Sanchez M, Omarini AB, González-Aguirre JA, Baglioni M, Zygadlo JA, Breccia J, D’Souza R, Lemesoff L, Bodeain M, Cardona-Alzate CA, Pejchinovski I, Fernandez-Lahore MH. Valorization routes of citrus waste in the orange value chain through the biorefinery concept: The Argentina case study. Chemical Engineering and Processing - Process Intensification. 2023 Jul 1;189. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Herrera N, Martínez-Ávila GCG, Robledo-Jiménez CL, Rojas R, Orozco-Zamora BS. From Citrus Waste to Valuable Resources: A Biorefinery Approach. Vol. 4, Biomass (Switzerland). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2024. p. 784–808. [CrossRef]

- Lee SH, Park SH, Park H. Assessing the Feasibility of Biorefineries for a Sustainable Citrus Waste Management in Korea. Vol. 29, Molecules. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2024. [CrossRef]

- Patsalou M, Chrysargyris A, Tzortzakis N, Koutinas M. A biorefinery for conversion of citrus peel waste into essential oils, pectin, fertilizer and succinic acid via different fermentation strategies. Waste Management. 2020 Jul 15;113:469–77. [CrossRef]

- Santiago B, Moreira MT, Feijoo G, González-García S. Identification of environmental aspects of citrus waste valorization into D-limonene from a biorefinery approach. Biomass Bioenergy. 2020 Dec 1;143. [CrossRef]

- Zema DA, Calabrò PS, Folino A, Tamburino V, Zappia G, Zimbone SM. Valorisation of citrus processing waste: A review. Vol. 80, Waste Management. Elsevier Ltd; 2018. p. 252–73. [CrossRef]

- Malik A, Najda A, Bains A, Nurzyńska-Wierdak R, Chawla P. Characterization of citrus nobilis peel methanolic extract for antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory activity. Molecules. 2021 Jul 2;26(14). [CrossRef]

- Mahato N, Sharma K, Sinha M, Cho MH. Citrus waste derived nutra-/pharmaceuticals for health benefits: Current trends and future perspectives. Vol. 40, Journal of Functional Foods. Elsevier Ltd; 2018. p. 307–16. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim S, Elsayed H, Hasanin M. Biodegradable, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Biofilm for Active Packaging Based on Extracted Gelatin and Lignocelluloses Biowastes. J Polym Environ. 2021 Feb 1;29(2):472–82.

- Mousavi Kalajahi SE, Alizadeh A, Hamishehkar H, Almasi H, Asefi N. Orange Juice Processing Waste as a Biopolymer Base for Biodegradable Film Formation Reinforced with Cellulose Nanofiber and Activated with Nettle Essential Oil. J Polym Environ. 2022 Jan 1;30(1):258–69. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Chen X, Guo Z, Feng X, Huang P, Du M, Zalán Z, Kan J. Distribution and natural variation of free, esterified, glycosylated, and insoluble-bound phenolic compounds in brocade orange (Citrus sinensis L. Osbeck) peel. Food Research International. 2022 Mar 1;153. [CrossRef]

- Afifi SM, Gök R, Eikenberg I, Krygier D, Rottmann E, Stübler AS, Aganovic K, Hillebrand S, Esatbeyoglu T. Comparative flavonoid profile of orange (Citrus sinensis) flavedo and albedo extracted by conventional and emerging techniques using UPLC-IMS-MS, chemometrics and antioxidant effects. Front Nutr. 2023;10. [CrossRef]

- Alperth F, Pogrilz B, Schrammel A, Bucar F. Coumarins in the Flavedo of Citrus limon Varieties—Ethanol and Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent Extractions With HPLC-DAD Quantification. Phytochemical Analysis [Internet]. 2025 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Jul 20];36(4):1141–52. Available from: /doi/pdf/10.1002/pca.3499. [CrossRef]

- Lin LY, Peng CC, Huang YP, Chen KC, Peng RY. p-Synephrine Indicates Internal Maturity of Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck cv. Mato Peiyu—Reclaiming Functional Constituents from Nonedible Parts. Molecules 2023, Vol 28, Page 4244 [Internet]. 2023 May 22 [cited 2025 Jul 20];28(10):4244. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/28/10/4244/htm. [CrossRef]

- Anmol RJ, Marium S, Hiew FT, Han WC, Kwan LK, Wong AKY, Khan F, Sarker MMR, Chan SY, Kifli N, Ming LC. Phytochemical and Therapeutic Potential of Citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck: A Review. J Evid Based Integr Med. 2021;26.

- Tsai ML, Lin C Di, Khoo KA, Wang MY, Kuan TK, Lin WC, Zhang YN, Wang YY. Composition and bioactivity of essential oil from citrus grandis (L.) Osbeck ‘Mato Peiyu’ leaf. Molecules. 2017 Dec 1;22(12).

- Lv X, Zhao S, Ning Z, Zeng H, Shu Y, Tao O, Xiao C, Lu C, Liu Y. Citrus fruits as a treasure trove of active natural metabolites that potentially provide benefits for human health. Vol. 9, Chemistry Central Journal. BioMed Central Ltd.; 2015. [CrossRef]

- Multari S, Licciardello C, Caruso M, Anesi A, Martens S. Flavedo and albedo of five citrus fruits from Southern Italy: physicochemical characteristics and enzyme-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization [Internet]. 2021 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Jul 20];15(2):1754–62. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11694-020-00787-5. [CrossRef]

- Arora S, Kataria P, Ahmad W, Mishra R, Upadhyay S, Dobhal A, Bisht B, Hussain A, Kumar V, Kumar S. Microwave Assisted Green Extraction of Pectin from Citrus maxima Albedo and Flavedo, Process Optimization, Characterisation and Comparison with Commercial Pectin. Food Anal Methods [Internet]. 2024 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jul 20];17(1):105–18. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Aftab J, Abbas M, Sharif S, Mumtaz A, Zafar K, Ahmad N, Mohammed OA, Nazir A, Iqbal S, Iqbal M. LC-MS/MS Profiling, Antioxidant Potential and Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Citrus reticulata Albedo. Nat Prod Commun [Internet]. 2024 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Jul 20];19(8). Available from: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_url?url=https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1934578X241272471&hl=es&sa=T&oi=ucasa&ct=ufr&ei=d-9-aNWUEpOIieoP1r2BgQM&scisig=AAZF9b82h5taYZY9suawCIrHnLzX.

- Seyyedi-Mansour S, Carpena M, Donn P, Barciela P, Perez-Vazquez A, Echave J, Pereira AG, Prieto MA. Citrus Seed Waste and Circular Bioeconomy: Insights on Nutritional Profile, Health Benefits, and Application as Food Ingredient. Applied Sciences 2024, Vol 14, Page 9463 [Internet]. 2024 Oct 16 [cited 2025 Jul 20];14(20):9463. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/14/20/9463/htm. [CrossRef]

- Zayed A, Badawy MT, Farag MA. Valorization and extraction optimization of Citrus seeds for food and functional food applications. Food Chem. 2021 Sep 1;355. [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Alisaraei A, Hosseini SH, Ghobadian B, Motevali A. Biofuel production from citrus wastes: A feasibility study in Iran. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews [Internet]. 2017 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Sep 2];69:1100–12. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032116305949. [CrossRef]

- Cypriano DZ, da Silva LL, Tasic L. High value-added products from the orange juice industry waste. Waste Management [Internet]. 2018 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Sep 2];79:71–8. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0956053X18304501. [CrossRef]

- Putnik P, Bursać Kovačević D, Režek Jambrak A, Barba FJ, Cravotto G, Binello A, Lorenzo JM, Shpigelman A. Innovative “Green” and Novel Strategies for the Extraction of Bioactive Added Value Compounds from Citrus Wastes—A Review. Molecules 2017, Vol 22, Page 680 [Internet]. 2017 Apr 27 [cited 2025 Sep 2];22(5):680. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/22/5/680/htm. [CrossRef]

- Figueira O, Pereira V, Castilho PC. A Two-Step Approach to Orange Peel Waste Valorization: Consecutive Extraction of Pectin and Hesperidin. Foods 2023, Vol 12, Page 3834 [Internet]. 2023 Oct 19 [cited 2025 Aug 1];12(20):3834. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/12/20/3834/htm. [CrossRef]

- Anticona M, Blesa J, Frigola A, Esteve MJ. High Biological Value Compounds Extraction from Citrus Waste with Non-Conventional Methods. Foods 2020, Vol 9, Page 811 [Internet]. 2020 Jun 20 [cited 2025 Jul 29];9(6):811. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/9/6/811/htm. [CrossRef]

- Twinomuhwezi H, Godswill AC, Kahunde D. Extraction and Characterization of Pectin from Orange (Citrus sinensis), Lemon (Citrus limon) and Tangerine (Citrus tangerina). American Journal of Physical Sciences [Internet]. 2023 Mar 9 [cited 2025 Sep 15];1(1):17–30. Available from: https://iprjb.org/journals/AJPS/article/view/1049. [CrossRef]

- Kiteto MK, Vidija BM, Mecha CA. Production of bioethanol from citrus peel waste: A techno – economic feasibility study. Energy Conversion and Management: X [Internet]. 2025 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Aug 10];26:100916. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590174525000480. [CrossRef]

- Vadalà R, Lo Vecchio G, Rando R, Leonardi M, Cicero N, Costa R. A Sustainable Strategy for the Conversion of Industrial Citrus Fruit Waste into Bioethanol. Sustainability (Switzerland) [Internet]. 2023 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Jul 28];15(12):9647. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/15/12/9647/htm. [CrossRef]

- Panwar D, Saini A, Panesar PS, Chopra HK. Unraveling the scientific perspectives of citrus by-products utilization: Progress towards circular economy. Trends Food Sci Technol [Internet]. 2021 May 1 [cited 2025 Aug 4];111:549–62. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924224421002107?via%3Dihub. [CrossRef]

- Andrade MA, Barbosa CH, Shah MA, Ahmad N, Vilarinho F, Khwaldia K, Silva AS, Ramos F. Citrus By-Products: Valuable Source of Bioactive Compounds for Food Applications. Antioxidants 2023, Vol 12, Page 38 [Internet]. 2022 Dec 25 [cited 2025 Sep 8];12(1):38. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3921/12/1/38/htm. [CrossRef]

- Singh V, Chahal TS, Gill PPS, Jawandha SK, Singh V. Fruit colour progression in grapefruit with relation to carotenoid and Brix-acid ratio. Indian Journal of Horticulture. 2023 Jun 29;80(2):184–9. [CrossRef]

- Ghani A, Mohtashami S, Jamalian S. Peel essential oil content and constituent variations and antioxidant activity of grapefruit (Citrus × paradisi var. red blush) during color change stages. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Sep 15];15(6):4917–28. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11694-021-01051-0. [CrossRef]

- Toprakçı G, Toprakçı İ, Şahin S. Highly clean recovery of natural antioxidants from lemon peels: Lactic acid-based automatic solvent extraction. Phytochemical Analysis [Internet]. 2022 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Sep 15];33(4):554–63. Available from: /doi/pdf/10.1002/pca.3109. [CrossRef]

- Argun ME, Öztürk A, Argun MŞ. Comparison of Different Extraction Methods on the Recovery Efficiencies of Valuable Components from Orange Peels. Turkish Journal of Agriculture - Food Science and Technology [Internet]. 2023 Dec 28 [cited 2025 Sep 16];11(12):2417–25. Available from: https://agrifoodscience.com/index.php/TURJAF/article/view/6519.

- Gómez-Mejía E, Sacristán I, Rosales-Conrado N, León-González ME, Madrid Y. Valorization of Citrus reticulata Blanco Peels to Produce Enriched Wheat Bread: Phenolic Bioaccessibility and Antioxidant Potential. Antioxidants (Basel) [Internet]. 2023 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Sep 9];12(9). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37760045/. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim FM, Abdelsalam E, Mohammed RS, Ashour WES, Vilas-Boas AA, Pintado M, El Habbasha ES. Polyphenol-Rich Extracts and Essential Oil from Egyptian Grapefruit Peel as Potential Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Anti-Inflammatory Food Additives. Applied Sciences 2024, Vol 14, Page 2776 [Internet]. 2024 Mar 26 [cited 2025 Sep 16];14(7):2776. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/14/7/2776/htm. [CrossRef]

- Kalompatsios D, Palaiogiannis D, Makris DP. Optimized Production of a Hesperidin-Enriched Extract with Enhanced Antioxidant Activity from Waste Orange Peels Using a Glycerol/Sodium Butyrate Deep Eutectic Solvent. Horticulturae 2024, Vol 10, Page 208 [Internet]. 2024 Feb 22 [cited 2025 Jul 28];10(3):208. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2311-7524/10/3/208/htm. [CrossRef]

- Ozturk B, Parkinson C, Gonzalez-Miquel M. Extraction of polyphenolic antioxidants from orange peel waste using deep eutectic solvents. Sep Purif Technol [Internet]. 2018 Nov 29 [cited 2025 Jul 28];206:1–13. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1383586618310499. [CrossRef]

- Panić M, Andlar M, Tišma M, Rezić T, Šibalić D, Cvjetko Bubalo M, Radojčić Redovniković I. Natural deep eutectic solvent as a unique solvent for valorisation of orange peel waste by the integrated biorefinery approach. Waste Management [Internet]. 2021 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Jul 28];120:340–50. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0956053X20306802. [CrossRef]

- Xu M, Ran L, Chen N, Fan X, Ren D, Yi L. Polarity-dependent extraction of flavonoids from citrus peel waste using a tailor-made deep eutectic solvent. Food Chem [Internet]. 2019 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Jul 28];297:124970. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308814619310726?via%3Dihub. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar CM, Carullo D, Saitta F, Krishnamachari H, Bellesia T, Nespoli L, Caneva E, Baschieri C, Signorelli M, Barbiroli AG, Fessas D, Farris S, Romano D. Valorization of citrus peel industrial wastes for facile extraction of extractives, pectin, and cellulose nanocrystals through ultrasonication: An in-depth investigation. Carbohydr Polym [Internet]. 2024 Nov 15 [cited 2025 Jul 28];344:122539. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0144861724007653?via%3Dihub. [CrossRef]

- Amador-Luna VM, Herrero M, Jiménez de la Parra M, Arribas ÁG, Ibáñez E, Montero L. Maximizing the neuroprotection from Citrus aurantium leaves: Optimization of a blended extract from a sequential extraction process with compressed fluids and NADES. Advances in Sample Preparation [Internet]. 2025 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Jul 28];13:100149. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772582025000038?via%3Dihub. [CrossRef]

- Midolo G, Cutuli G, Porto SMC, Ottolina G, Paini J, Valenti F. LCA analysis for assessing environmenstal sustainability of new biobased chemicals by valorising citrus waste. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jul 28];14(1):1–13. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-72468-y. [CrossRef]

- Argun ME, Argun MŞ, Arslan FN, Nas B, Ates H, Tongur S, Cakmakcı O. Recovery of valuable compounds from orange processing wastes using supercritical carbon dioxide extraction. J Clean Prod [Internet]. 2022 Nov 15 [cited 2025 Jul 28];375:134169. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652622037416. [CrossRef]

- Romano R, De Luca L, Aiello A, Rossi D, Pizzolongo F, Masi P. Bioactive compounds extracted by liquid and supercritical carbon dioxide from citrus peels. Int J Food Sci Technol [Internet]. 2022 May 18 [cited 2025 Jul 28];57(6):3826–37. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Batista MG, Herbst G, Kolicheski MB, Voll FAP, Corazza ML. d-Limonene extraction from Citrus reticulata Blanco wastes with compressed propane and supercritical CO2. J Supercrit Fluids [Internet]. 2025 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jul 28];215:106426. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0896844624002614. [CrossRef]

- Saini A, Panesar PS, Bera MB. Valorization of fruits and vegetables waste through green extraction of bioactive compounds and their nanoemulsions-based delivery system. Bioresour Bioprocess [Internet]. 2019 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jul 28];6(1):1–12. Available from: https://bioresourcesbioprocessing.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40643-019-0261-9. [CrossRef]

- Oprea I, Fărcaș AC, Leopold LF, Diaconeasa Z, Coman C, Socaci SA. Nano-Encapsulation of Citrus Essential Oils: Methods and Applications of Interest for the Food Sector. Polymers 2022, Vol 14, Page 4505 [Internet]. 2022 Oct 25 [cited 2025 Sep 18];14(21):4505. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4360/14/21/4505/htm. [CrossRef]

- Aulitto M, Alfano A, Maresca E, Avolio R, Errico ME, Gentile G, Cozzolino F, Monti M, Pirozzi A, Donsì F, Cimini D, Schiraldi C, Contursi P. Thermophilic biocatalysts for one-step conversion of citrus waste into lactic acid. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jul 28];108(1):1–12. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00253-023-12904-7. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Guo L, Mao X, Ji C, Li W, Zhou Z. Changes in the nutritional, flavor, and phytochemical properties of Citrus reticulata Blanco cv. ‘Dahongpao’ whole fruits during enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2024 Oct 3;8:1474760. [CrossRef]

- Lu X, Zhao C, Liu D, Hu M, Cui J, Wang F, Zeng L, Zheng J. A novel prebiotic enzymatic hydrolysate of citrus pectin during juice processing. Food Hydrocoll [Internet]. 2024 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jul 28];146:109198. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0268005X23007440?via%3Dihub. [CrossRef]

- Protzko RJ, Latimer LN, Martinho Z, de Reus E, Seibert T, Benz JP, Dueber JE. Engineering Saccharomyces cerevisiae for co-utilization of d-galacturonic acid and d-glucose from citrus peel waste. Nat Commun [Internet]. 2018 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jul 28];9(1). Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Saeed M, Kamboh AA, Huayou C. Promising future of citrus waste into fermented high-quality bio-feed in the poultry nutrition and safe environment. Poult Sci [Internet]. 2024 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Jul 28];103(4):103549. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0032579124001287?via%3Dihub. [CrossRef]

- Wani KM, Nayana P, Khalid ·, Wani M, Wani KM. Unlocking the green potential: sustainable extraction of bioactives from orange peel waste for environmental and health benefits. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2024 18:10 [Internet]. 2024 Aug 23 [cited 2025 Jul 29];18(10):8145–62. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11694-024-02779-1. [CrossRef]

- Boukroufa M, Boutekedjiret C, Chemat F. Development of a green procedure of citrus fruits waste processing to recover carotenoids. Resource-Efficient Technologies [Internet]. 2017 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Jul 29];3(3):252–62. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405653716301981.

- Bigi F, Maurizzi E, Haghighi H, Siesler HW, Licciardello F, Pulvirenti A. Waste Orange Peels as a Source of Cellulose Nanocrystals and Their Use for the Development of Nanocomposite Films. Foods [Internet]. 2023 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Jul 29];12(5):960. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/12/5/960/htm. [CrossRef]

- Fakhariha M, Rafati AA, Garmakhany AD, Asl AZ. Nanoencapsulation enhances stability, release behavior, and antimicrobial properties of Sage and Thyme essential oils. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2025 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jul 29];15(1):1–18. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-00022-5. [CrossRef]

- Yadav S, Sharma CS. Novel and green processes for citrus peel extract: a natural solvent to source of carbon. Polymer Bulletin [Internet]. 2018 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Jul 29];75(11):5133–42. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00289-018-2310-5. [CrossRef]

- Tang W, Han T, Liu W, He J, Liu J. Pectic oligosaccharides: enzymatic preparation, structure, bioactivities and application. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2025;65(11):2117–33. [CrossRef]

- Foti P, Ballistreri G, Timpanaro N, Rapisarda P, Romeo F V. Prebiotic effects of citrus pectic oligosaccharides. Nat Prod Res [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Jul 29];36(12):3173–6. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14786419.2021.1948845. [CrossRef]

- de Paula F, Vieira NV, da Silva GF, Delforno TP, Duarte ICS. A Comparison of Microbial Communities of Mango and Orange Residues for Bioprospecting of Biosurfactant Producers. Ecologies [Internet]. 2022 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Jul 29];3(2):120–30. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2673-4133/3/2/10/htm. [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman S, Rajendran DS, Kumar PS, Rangasamy G, Vaidyanathan VK. A Comprehensive Review on the Refinery of Citrus Peel Towards the Production of Bioenergy, Biochemical and Biobased Value-Added Products: Present Insights and Futuristic Challenges. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2024 15:11 [Internet]. 2024 Jun 12 [cited 2025 Jul 29];15(11):6491–512. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12649-024-02557-6. [CrossRef]

- He Y, Zhu Y, Lv J, Gu Y, Wang T, Chen J. Effects of lactic acid bacteria fermentation on the bioactive composition, volatile compounds and antioxidant activity of Huyou (Citrus aurantium ‘Changshan-huyou’) peel and pomace. Food Quality and Safety [Internet]. 2023 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jul 29];7:1–13. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Tropea A, Potortì AG, Turco V Lo, Russo E, Vadalà R, Rando R, Di Bella G. Aquafeed Production from Fermented Fish Waste and Lemon Peel. Fermentation 2021, Vol 7, Page 272 [Internet]. 2021 Nov 21 [cited 2025 Jul 29];7(4):272. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2311-5637/7/4/272/htm. [CrossRef]

- Lima CA, Contato AG, de Oliveira F, da Silva SS, Hidalgo VB, Irfan M, Gambarato BC, Carvalho AKF, Bento HBS. Trends in Enzyme Production from Citrus By-Products. Processes 2025, Vol 13, Page 766 [Internet]. 2025 Mar 6 [cited 2025 Jul 28];13(3):766. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9717/13/3/766/htm. [CrossRef]

- Gooruee R, Hojjati M, Behbahani BA, Shahbazi S, Askari H. Extracellular enzyme production by different species of Trichoderma fungus for lemon peel waste bioconversion. Biomass Convers Biorefin [Internet]. 2024 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jul 29];14(2):2777–86. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13399-022-02626-7. [CrossRef]

- MEDELEANU ML, FĂRCAȘ AC, COMAN C, LEOPOLD LF, DIACONEASA Z, SENDRA E, CARBONELL PEDRO AA, SOCACI SA. Citrus Essential Oils’ Nano-emulsions: Formulation and Characterization. Bulletin of University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca Food Science and Technology. 2024 Nov 15;81(2):95–113. [CrossRef]

- Chen C, Meng FB, Lv HJ, Gou ZZ, Qiu J, Li YC. Study on the bacteriostasis of lemon essential oil and the application of lemon essential oil nanoemulsion on fresh-cut kiwifruit. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2024 May 22;8:1394831. [CrossRef]

- Meng FB;, Gou ZZ;, Li YC;, Zou LH;, Chen WJ;, Liu DY, Meng FB, Gou ZZ, Li YC, Zou LH, Chen WJ, Liu DY. The Efficiency of Lemon Essential Oil-Based Nanoemulsions on the Inhibition of Phomopsis sp. and Reduction of Postharvest Decay of Kiwifruit. Foods 2022, Vol 11, Page 1510 [Internet]. 2022 May 22 [cited 2025 Sep 19];11(10):1510. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/11/10/1510/htm. [CrossRef]

- Caballero S, Li YO, McClements DJ, Davidov-Pardo G. Encapsulation and delivery of bioactive citrus pomace polyphenols: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 19];62(29):8028–44. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33983085/. [CrossRef]

- Li F, Song X, Chen Y, He L, Wu Y, Huang Q, Huang M, Li X. Effect of barrier function of lemon essential oil-gelatin composite coating on flavor quality of kiwifruit during storage. Journal of Future Foods [Internet]. 2025 Aug 19 [cited 2025 Sep 19]; Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2772566925002204. [CrossRef]

- Dalei G, Das S, Mohanty D, Biswal S, Jena D, Dehury P, Das BR. Xanthan gum-Pectin Edible Coating Enriched with Sweet Orange (Citrus sinensis L.) Peel Essential Oil for Chicken Meat Preservation. Food Biophys [Internet]. 2025 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Aug 1];20(1):1–16. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11483-025-09949-8. [CrossRef]

- Rawat S, Pavithra T, Sunil CK. Citrus byproduct valorization: pectin extraction, characterization, and research advances in biomaterial derivation for applications in active film packaging. Discover Food 2024 4:1 [Internet]. 2024 Nov 19 [cited 2025 Aug 1];4(1):1–33. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s44187-024-00238-w. [CrossRef]

- Sharma P, Vishvakarma R, Gautam K, Vimal A, Kumar Gaur V, Farooqui A, Varjani S, Younis K. Valorization of citrus peel waste for the sustainable production of value-added products. Vol. 351, Bioresource Technology. Elsevier Ltd; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Suri S, Singh A, Nema PK. Current applications of citrus fruit processing waste: A scientific outlook. Applied Food Research [Internet]. 2022 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Jul 28];2(1):100050. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772502222000105?via%3Dihub. [CrossRef]

- Silla A, Punzo A, Caliceti C, Barbalace MC, Hrelia S, Malaguti M. The Role of Antioxidant Compounds from Citrus Waste in Modulating Neuroinflammation: A Sustainable Solution. Antioxidants [Internet]. 2025 May 1 [cited 2025 Aug 1];14(5):581. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12108332/. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud SH, Moselhy WA, Azmy AF, El-Ela FIA. Hesperidin loaded bilosomes mitigate the nephrotoxicity induced by methotrexate; biochemical and molecular in vivo investigations. BMC Nephrol [Internet]. 2025 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Aug 1];26(1):1–16. Available from: https://bmcnephrol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12882-025-04328-4. [CrossRef]

- Gözcü S, Polat HK, Gültekin Y, Ünal S, Karakuyu NF, Şafak EK, Doğan O, Pezik E, Haydar MK, Aytekin E, Kurt N, Laçin BB. Formulation of hesperidin-loaded in situ gel for ocular drug delivery: a comprehensive study. J Sci Food Agric [Internet]. 2024 Aug 15 [cited 2025 Aug 1];104(10):5846–59. Available from: /doi/pdf/10.1002/jsfa.13407. [CrossRef]

- Samota MK, Kaur M, Sharma M, Sarita, Krishnan V, Thakur J, Rawat M, Phogat B, Guru PN. Hesperidin from citrus peel waste: extraction and its health implications. Quality Assurance and Safety of Crops and Foods. 2023;15(2):71–99.

- Sultana N. Biological Properties and Biomedical Applications of Pectin and Pectin-Based Composites: A Review. Molecules 2023, Vol 28, Page 7974 [Internet]. 2023 Dec 6 [cited 2025 Aug 2];28(24):7974. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/28/24/7974/htm. [CrossRef]

- Xue L, An R, Zhao J, Qiu M, Wang Z, Ren H, Yu D, Zhu X. Self-Healing Hydrogels: Mechanisms and Biomedical Applications. MedComm (Beijing) [Internet]. 2025 May 1 [cited 2025 Aug 2];6(5):e70181. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12018771/. [CrossRef]

- Calì F, Cantaro V, Fichera L, Ruffino R, Trusso Sfrazzetto G, Li-destri G, Tuccitto N. Carbon Quantum Dots from Lemon Waste Enable Communication among Biodevices. Chemosensors 2021, Vol 9, Page 202 [Internet]. 2021 Jul 30 [cited 2025 Jul 31];9(8):202. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9040/9/8/202/htm. [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar A, Radoor S, Shin GH, Kim JT. Lemon peel-based fluorescent carbon quantum dots as a functional filler in polyvinyl alcohol-based films for active packaging applications. Ind Crops Prod [Internet]. 2024 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Aug 2];209:117968. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0926669023017338. [CrossRef]

- Kundu A, Basu S, Maity B. Upcycling Waste: Citrus limon Peel-Derived Carbon Quantum Dots for Sensitive Detection of Tetracycline in the Nanomolar Range. ACS Omega [Internet]. 2023 Oct 3 [cited 2025 Aug 2];8(39):36449–59. Available from: /doi/pdf/10.1021/acsomega.3c05424?ref=article_openPDF. [CrossRef]

- Imran A, Ahmed F, Ali YA, Naseer MS, Sharma K, Bisht YS, Alawadi AH, Shehzadi U, Islam F, Shah MA. A comprehensive review on carbon dot synthesis and food applications. J Agric Food Res [Internet]. 2025 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Aug 2];21:101847. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666154325002182. [CrossRef]

- Tavan M, Yousefian Z, Bakhtiar Z, Rahmandoust M, Mirjalili MH. Carbon quantum dots: Multifunctional fluorescent nanomaterials for sustainable advances in biomedicine and agriculture. Ind Crops Prod [Internet]. 2025 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Aug 2];231:121207. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0926669025007538. [CrossRef]

- Aksu M, Güzdemir Ö. Food Waste-Derived Carbon Quantum Dots and Their Applications in Food Technology: A Critical Review. Food Bioproc Tech [Internet]. 2025 Apr 29 [cited 2025 Aug 2];18(8):6753–78. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11947-025-03854-1. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Chen T, Ge S, Fan W, Wang H, Zhang Z, Lichtfouse E, Van Tran T, Liew RK, Rezakazemi M, Huang R. Synthesis and applications of carbon quantum dots derived from biomass waste: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2023 21:6 [Internet]. 2023 Aug 12 [cited 2025 Aug 2];21(6):3393–424. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10311-023-01636-9. [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan M, Palanisamy S, Khan R, H.Alrasheedi N, Tadepalli S, Murugesan T mani, Santulli C. Synthesis and suitability characterization of microcrystalline cellulose from Citrus x sinensis sweet orange peel fruit waste-based biomass for polymer composite applications. Journal of Polymer Research [Internet]. 2024 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Aug 2];31(4):1–16. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10965-024-03946-0. [CrossRef]

- Mahato N, Sharma K, Sinha M, Baral ER, Koteswararao R, Dhyani A, Cho MH, Cho S. Bio-sorbents, industrially important chemicals and novel materials from citrus processing waste as a sustainable and renewable bioresource: A review. J Adv Res [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Aug 1];23:61–82. Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Julaeha E, Nurzaman M, Wahyudi T, Nurjanah S, Permadi N, Anshori J Al. The Development of the Antibacterial Microcapsules of Citrus Essential Oil for the Cosmetotextile Application: A Review. Molecules 2022, Vol 27, Page 8090 [Internet]. 2022 Nov 21 [cited 2025 Aug 2];27(22):8090. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/27/22/8090/htm. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed AL, El-Zawahry M, Hassabo AG, Abd El-Aziz E. Encapsulated lemon oil and metal nanoparticles in biopolymer for multifunctional finishing of cotton and wool fabrics. Ind Crops Prod [Internet]. 2023 Nov 15 [cited 2025 Aug 2];204:117373. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S092666902301138X. [CrossRef]

- Corzo D, Rosas-Villalva D, Amruth C, Tostado-Blázquez G, Alexandre EB, Hernandez LH, Han J, Xu H, Babics M, De Wolf S, Baran D. High-performing organic electronics using terpene green solvents from renewable feedstocks. Nat Energy [Internet]. 2023 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jul 31];8(1):62–73. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41560-022-01167-7. [CrossRef]

- Negro V, Mancini G, Ruggeri B, Fino D. Citrus waste as feedstock for bio-based products recovery: Review on limonene case study and energy valorization. Bioresour Technol [Internet]. 2016 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Aug 1];214:806–15. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960852416306460?via%3Dihub. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary H, Dinakaran J, Rao KS. Comparative analysis of biochar production methods and their impacts on biochar physico-chemical properties and adsorption of heavy metals. J Environ Chem Eng [Internet]. 2024 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Aug 2];12(3):113003. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213343724011333. [CrossRef]

- Lawal SY, Batagarawa SM, Musa A. Effect of Citrus sinensis peel-derived biochar on the concentrations of heavy metals in soil irrigated with municipal wastewater. Jabirian Journal of Biointerface Research in Pharmaceutics and Applied Chemistry [Internet]. 2024 Jan 7 [cited 2025 Aug 2];1(1):18–22. Available from: https://sprinpub.com/jabirian/article/view/jabirian-1-1-3-18-22. [CrossRef]

- Yekzaban A, Moosavi AA, Sameni A, Rezaei M. Effect of palm leaf and lemon peel biochar on some physical and mechanical properties of a sandy loam soil. Water and Soil Management and Modeling. 2023;3(1):69–83.

- Mohawesh O, Albalasmeh A, Gharaibeh M, Deb S, Simpson C, Singh S, Al-Soub B, Hanandeh A El. Potential Use of Biochar as an Amendment to Improve Soil Fertility and Tomato and Bell Pepper Growth Performance Under Arid Conditions. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2021 Dec 1;21(4):2946–56. [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi AG, Ighalo JO, Onifade DV. Biochar from the Thermochemical Conversion of Orange (Citrus sinensis) Peel and Albedo: Product Quality and Potential Applications. Chemistry Africa [Internet]. 2020 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Aug 2];3(2):439–48. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42250-020-00119-6. [CrossRef]

- Mruthunjaya K, Manjula SN, Sharma H, Anand A, Kenchegowda M. Valorization of Citrus Waste for the Synthesis of Value Added Products. In: Valorization of Citrus Food Waste [Internet]. Springer, Cham; 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 2]. p. 179–213. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-77999-2_10.

- González-Miquel M, Díaz I. Valorization of citrus waste through sustainable extraction processes. Food Industry Wastes: Assessment and Recuperation of Commodities [Internet]. 2020 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jul 30];113–33. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780128171219000061.

- Kumar R, Ali A, Sheoran SS. Challenges and Opportunities in Citrus Waste Valorization. Valorization of Citrus Food Waste. 2025;435–47.

- Zema DA, Calabrò PS, Folino A, Tamburino V, Zappia G, Zimbone SM. Valorisation of citrus processing waste: A review. Vol. 80, Waste Management. Elsevier Ltd; 2018. p. 252–73. [CrossRef]

- Riaz S, Hyder M, Xian L, Yue ZK, Abbas G, Waqar M, Irfan F, Kamal D, Tabassum H, Ali A. Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Citrus Waste Through Green Technologies. Valorization of Citrus Food Waste [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 29];215–30. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-77999-2_11.

- Khalati E, Oinas P, Favén L. Techno-economic and safety assessment of supercritical CO2 extraction of essential oils and extracts. Journal of CO2 Utilization [Internet]. 2023 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Jul 31];74:102547. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212982023001580. [CrossRef]

- Amenta V, Aschberger K, Arena M, Bouwmeester H, Botelho Moniz F, Brandhoff P, Gottardo S, Marvin HJP, Mech A, Quiros Pesudo L, Rauscher H, Schoonjans R, Vettori MV, Weigel S, Peters RJ. Regulatory aspects of nanotechnology in the agri/feed/food sector in EU and non-EU countries. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology [Internet]. 2015 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Jul 30];73(1):463–76. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26169479/. [CrossRef]

- More S, Bampidis V, Benford D, Bragard C, Halldorsson T, Hernández-Jerez A, Hougaard Bennekou S, Koutsoumanis K, Lambré C, Machera K, Naegeli H, Nielsen S, Schlatter J, Schrenk D, Silano V, Turck D, Younes M, Castenmiller J, Chaudhry Q, Cubadda F, Franz R, Gott D, Mast J, Mortensen A, Oomen AG, Weigel S, Barthelemy E, Rincon A, Tarazona J, Schoonjans R. Guidance on risk assessment of nanomaterials to be applied in the food and feed chain: human and animal health. EFSA Journal. 2021 Aug 1;19(8). [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay A. Global Regulatory Framework for Nano-Agri-Input Products for Commercialization. Nanobiotechnology for Agricultural Sciences: Nano-Agri-Input Products for Crop Production and Environmental Protection [Internet]. 2025 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jul 31];177–95. Available from: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9781003620273-6/global-regulatory-framework-nano-agri-input-products-commercialization-arkadeb-mukhopadhyay.

- Crenna E, Hischier R, Defraeye T, Onwude D. Ecological hotspots of the journey of a South African citrus fruit. 2024 Dec 23 [cited 2025 Jul 31]; Available from: https://engrxiv.org/preprint/view/4251.

- Iñigo Martínez ME, Fuentes R, Ploper A, Paz D, Arena AP. Optimizing supply chains of citrus products with analysis across several design configurations. Environ Syst Decis [Internet]. 2025 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Jul 31];45(2):1–21. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10669-025-10008-3. [CrossRef]

- Dhahri S, Shall H, Thabet Mliki N. Towards sustainable Nanomaterials: Exploring green synthesis methods and their impact on electrical properties. Inorg Chem Commun. 2024 Oct 1;168. [CrossRef]

- Gaur R. Environmental impact and life cycle analysis of green nanomaterials. Green Functionalized Nanomaterials for Environmental Applications [Internet]. 2022 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jul 31];513–39. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B978012823137100018X.

- Kane S, Miller SA, Kurtis KE, Youngblood JP, Landis EN, Weiss WJ. Harmonized Life-Cycle Inventories of Nanocellulose and Its Application in Composites. Environ Sci Technol [Internet]. 2023 Dec 5 [cited 2025 Jul 31];57(48):19137–47. Available from: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/acs.est.3c04814?ref=article_openPDF. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Aljafree NF, Norrrahim MNF, Samsuri A, Wan Yunus WMZ. Environmental impact and sustainability of nanocellulose-based nitrated polymers in propellants. RSC Adv [Internet]. 2025 Jul 10 [cited 2025 Jul 31];15(30):24167–91. Available from: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2025/ra/d5ra02169c.

- Li D qiang, Li J, Dong H lin, Li X, Zhang J qi, Ramaswamy S, Xu F. Pectin in biomedical and drug delivery applications: A review. Int J Biol Macromol [Internet]. 2021 Aug 31 [cited 2025 Jul 31];185:49–65. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0141813021013167.

- Munarin F, Tanzi MC, Petrini P. Advances in biomedical applications of pectin gels. Int J Biol Macromol [Internet]. 2012 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Jul 31];51(4):681–9. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0141813012002759. [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel J, Bizzo HR, Doria Chaves ACS, Faria-Machado AF, Gomes Soares A, de Oliveira Fonseca MJ, Kidmose U, Rosenthal A. Sustainable use of tropical fruits? Challenges and opportunities of applying the waste-to-value concept to international value chains. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2023;63(10):1339–51. [CrossRef]

- Raimondo M, Caracciolo F, Cembalo L, Chinnici G, Pecorino B, D’Amico M. Making Virtue Out of Necessity: Managing the Citrus Waste Supply Chain for Bioeconomy Applications. Sustainability 2018, Vol 10, Page 4821 [Internet]. 2018 Dec 17 [cited 2025 Jul 31];10(12):4821. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/10/12/4821/htm. [CrossRef]

- Asveld L. Inclusion and Resilience in the Bioeconomy. Bio Futures: Foreseeing and Exploring the Bioeconomy [Internet]. 2021 May 6 [cited 2025 Jul 31];605–19. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-64969-2_27.

- The 2025 Sustainable Packaging Consumer Report | Shorr Packaging [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 25]. Available from: https://www.shorr.com/resources/blog/sustainable-packaging-consumer-report/.

- Huaman-Moran RF, Chávez-Huaycuche V, Crhistian ;, Larrea-Cerna O, David ;, Callirgos-Romero A, Daniel ;, Alvarado Leon E. Nanotecnología y biopolímeros: Una alternativa sostenible para los empaques y embalajes. Manglar [Internet]. 2024 Dec 18 [cited 2025 Sep 25];21(4):545–60. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2414-10462024000400545&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es.

- 76% dos consumidores se importam com embalagens sustentáveis [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 25]. Available from: https://sagresonline.com.br/76-dos-consumidores-brasileiros-se-importam-com-embalagens-sustentaveis/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- ERT revela crecimiento de la demanda de bioplásticos en Brasil en 2025 - Conecta Verde [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 25]. Available from: https://conectaverde.com.br/ert-revela-crescimento-na-demanda-por-bioplasticos-no-brasil-em-2025/.

- Biswas R, Alam M, Sarkar A, Haque MI, Hasan MM, Hoque M. Application of nanotechnology in food: processing, preservation, packaging and safety assessment. Heliyon [Internet]. 2022 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Sep 25];8(11):e11795. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844022030833. [CrossRef]

- Shorbagi M, Fayek NM, Shao P, Farag MA. Citrus reticulata Blanco (the common mandarin) fruit: An updated review of its bioactive, extraction types, food quality, therapeutic merits, and bio-waste valorization practices to maximize its economic value. Food Biosci [Internet]. 2022 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Sep 25];47:101699. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212429222001584?via%3Dihub. [CrossRef]

- Law 20920. Establishment of a framework for waste management, extended producer responsibility and recycling. – Policies - IEA [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 28]. Available from: https://www.iea.org/policies/16005-law-20920-establishment-of-a-framework-for-waste-management-extended-producer-responsibility-and-recycling?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Chile: Is your company affected by the recent changes? - ERP Global [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 28]. Available from: https://erp-recycling.org/news-and-events/2023/10/chile-is-your-company-affected-by-the-recent-changes/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Chile targets fast fashion waste with landmark desert cleanup plan | Chile | The Guardian [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 28]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jun/26/chile-fast-fashion-waste-atacama-desert?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- L E Y D E E C O N O M Í A C I R C U L A R D E L A C I U D A D D E M É X I C O.

- News Anvisa’s Latest Guidance on Food Contact Materials and Susta [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 29]. Available from: https://gpcgateway.com/common/news_details/MTM2MA/MTQ/zlib?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Recycling food packaging: Anvisa answers questions - Brazilian NR [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 29]. Available from: https://braziliannr.com/2024/03/01/recycling-food-packaging-anvisa-answers-questions/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Anvisa and the New Regulation on Food and Packaging - CGM [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 29]. Available from: https://cgmlaw.com.br/en/anvisa-and-the-new-regulation-on-food-and-packaging/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Brazil Updates Food Contact Material Regulations: Adds Two New Substances with Usage Restrictions | News | ChemRadar [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.chemradar.com/en/news/detail/efo7hujctszk?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Estrategia Nacional de Economía Circular - [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.minambiente.gov.co/asuntos-ambientales-sectorial-y-urbana/estrategia-nacional-de-economia-circular/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Estrategia Nacional de Economía Circular | Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 29]. Available from: https://archivo.minambiente.gov.co/index.php/estrategia-nacional-de-economia-circular-ec?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Vera-Acevedo LD, Raufllet E, Vera-Acevedo LD, Raufllet E. Análisis de la Estrategia Nacional de Economía Circular de Colombia a partir de dos modelos. Estudios Políticos [Internet]. 2022 May 16 [cited 2025 Sep 29];(64):27–52. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0121-51672022000200027&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=es. [CrossRef]

- Gobierno aprueba “Hoja de Ruta hacia una Economía Circular en Sector Industria” - Noticias - Ministerio del Ambiente - Plataforma del Estado Peruano [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minam/noticias/84631-gobierno-aprueba-hoja-de-ruta-hacia-una-economia-circular-en-sector-industria?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Hoja de Ruta Nacional de Economía Circular al 2030 – Economia circular en Perú [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 29]. Available from: https://economiacircularperu.pe/hoja-de-ruta-nacional-al-2030/.

- Benalia S, Falcone G, Stillitano T, De Luca AI, Strano A, Gulisano G, Zimbalatti G, Bernardi B. Increasing the Content of Olive Mill Wastewater in Biogas Reactors for a Sustainable Recovery: Methane Productivity and Life Cycle Analyses of the Process. Foods 2021, Vol 10, Page 1029 [Internet]. 2021 May 10 [cited 2025 Aug 9];10(5):1029. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/10/5/1029/htm. [CrossRef]

- Facchinelli T, D’Amato E, Bettotti P, Trenti F, Guella G, Bartali R, Laidani NB, Spigno G, Scarpa M. Nanocellulose with hydrophobic properties by a one-step TEMPO-periodate oxidation of citrus waste. Cellulose [Internet]. 2024 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Aug 10];31(18):10895–913. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10570-024-06259-z. [CrossRef]

- Günter E, Popeyko O, Vityazev F, Popov S. Effect of Callus Cell Immobilization on the Textural and Rheological Properties, Loading, and Releasing of Grape Seed Extract from Pectin Hydrogels. Gels 2024, Vol 10, Page 273 [Internet]. 2024 Apr 17 [cited 2025 Aug 2];10(4):273. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2310-2861/10/4/273/htm. [CrossRef]

- Hamed R, Magamseh KH, Al-Shalabi E, Hammad A, Abu-Sini M, Abulebdah DH, Tarawneh O, Sunoqrot S. Green Hydrogels Prepared from Pectin Extracted from Orange Peels as a Potential Carrier for Dermal Delivery Systems. ACS Omega [Internet]. 2025 May 6 [cited 2025 Aug 2];10(17):17182–200. Available from: /doi/pdf/10.1021/acsomega.4c08449?ref=article_openPDF. [CrossRef]

- Das S, Singh VK, Dwivedy AK, Chaudhari AK, Dubey NK. Insecticidal and fungicidal efficacy of essential oils and nanoencapsulation approaches for the development of next generation ecofriendly green preservatives for management of stored food commodities: an overview. Int J Pest Manag [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 28];70(3):235–66. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09670874.2021.1969473. [CrossRef]

- Quiñonez-Montaño LJ, Núñez-Pérez J, Prado-Beltrán JK, Cañarejo-Antamba MA, Burbano-García JL, Chiliquinga-Quispe AJ, Rodríguez-Cabrera HM, Pais-Chanfrau JM. Ethanolic Extracts from Tangerine (<em>Citrus reticulata</em> L.) Peels as an Eco-Friendly Botanical Pesticide for Small-Farm Potato (<em>Solanum tuberosum</em> L.) Cultivation. 2025 Mar 18 [cited 2025 Jul 28]; Available from: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202503.1380/v1.

| Compoud | Orange | Lemon | Tangerine, mandarin or clementine | Grapefruit | Reference |

| Pectin (% DW) | 23.02 ± 2.12 18.49 ± 1.74 18.73 ± 1.19 |

13.00 ± 1.06 16.61 |

16.0 21.95 15.23 |

8.5 17.92 |

[44,45,46,47,48,49,50] |

| Cellulose (% DW) | 37.08 ± 3.10 19.73 ± 0.93 17.02 ± 2.70 |

23.06 ± 2.11 | 22.5 17.29 ± 1.02 |

26.57 | [17,44,45,46,50,51] |

| Hemicellulose (% DW) | 11.04 ± 1.05 6.33 ± 0.14 37.2 ± 3.3 |

8.09 ± 0.81 | 6.0 11.38 ± 0.98 |

5.60 | [17,44,45,46,50,51] |

| Lignin (% DW) | 7.52 ± 0.59 4.18 ± 0.69 |

7.56 ± 0.54 | 8.8 0.56 |

11.6 | [44,45,46,50,52] |

| Sugars (% DW) | 9.6 21.06 ± 1.93 |

6.5 | 10.1 | 8.1 | [44,45,50] |

| Carotenoids (μg/gβ-caroten) | 50.94 ± 2.28 6.30 |

11.09 ± 0.47 | 98.80 ± 2.95 | 3.61 - 61.42 | [48,53,54] |

| D-Limonene (% EO) | 94.88 | 94.427 | 97.38 | 90.92–93.98 | [48,55] |

|

Hesperidin (mg/g DW) |

2.07 ± 0.38 2.052 |

0.07 | 29.50 ± 0.32 13.74 64.45 58.60 |

0.071 0.62 – 1.09 |

[48,53,56] |

| TPC (mg GAE/g) | 12.20 66.36 12.59 |

15.74 18.12 15.22 |

30.84 152.57 58.68 |

21.17 12.48 |

[46,48] |

| TFC (mg QE/g) | 36.29 ± 5.69 | 30 ± 3 |

25.40 7.93 6.38 |

13.09 ± 0.06 | [48,57,58,59] |

| Technology | Target Product(s) | Key Advantage | Author(s) |

| Deep eutectic solvents (DES) | Flavonoids, microcellulose | high selectivity, green chemistry | [60,63,64] |

| Supercritical CO₂ extraction | Limonene, phenolics | no thermal degradation, high purity | [65,67,77] |

| Ultrasonication | Pectin, CNCs | energy efficient, high yield | [64,78,79] |

| Nanoencapsulation | Essential oils | controlled release, enhanced food safety | [2,5,80] |

| Enzymatic hydrolysis | Prebiotic oligosaccharides, sugars | mild conditions, prodution of functional products | [81,82,83] |

| Microbial fermentation | Biosurfactants, L-lactic acid, bioethanol, feed | Biochemical diversity, sustainability, high yield | [2,51,72,76,84,85,86,87] |

| Enzyme production | Cellulases, pectinases, xylanases | Supports biorefineries, circular economy | [23,88,89] |

| Focus Area | Recent Advances | Key Challenges | References |

| Nanocellulose | Flexible electronics, biopolymer high-performance reinforcement, composites | industrial scale-up, reproducibility, byproduct safety | [6,64,163] |

| Limonene-based polymers | Bio-based plastics, vitrimers, sustainable coatings | process optimization, market adoption | [52,117] |

| Biochar | Soil remediation, carbon sequestration, nutrient retention | standardization of pyrolysis processes, long-term agronomic trials, scaling in diverse soils | [73,81,95,96,102,164,165] |

| Nutraceuticals (Hesperidin & Flavonoids) | Advanced drug delivery (nanoformulations, bilosomes), anti-inflammatory therapies | clinical validation, bioavailability, regulatory approval in functional foods and nutraceuticals | [8,76,77,78,79,80] |

| AI & circular models | Process optimization, industrial symbiosis, blockchain-based traceability | technological integration, real-time compositional data, cost of implementation | [66,69,162] |

| Ecotoxicity & LCA | Initial risk assessments for citrus-derived nanomaterials, partial LCAs reported | long-term ecotoxicological studies, comprehensive cradle-to-grave life cycle analyses | [112,121,166,167] |

| Consumer acceptance & market integration | Growing demand for natural additives, functional packaging, textiles (Orange Fiber S.r.l.) | consumer awareness, certification frameworks, equitable access for SMEs in emerging economies | [27,75,83,125] |

| Policy & governance | National circular economy roadmaps, EU Green Deal alignment, pilot regulations | lack of harmonized standards for nanomaterials, limited incentives in Latin America/Asia | [22,109,110,111,112,114,115] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).