1. Introduction

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses, particularly those of the H5 subtype, continue to pose significant threats to animal health, agricultural production, and public health [

1,

2]. Outbreaks of HPAI in the United States have traditionally been associated with wild aquatic birds, which serve as natural reservoirs and play a central role in the dissemination of the virus through migratory flyways [

3]. In recent years, multiple incursions of HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b have been documented in wild birds across North America, leading to spillover into domestic poultry populations and causing substantial economic losses [

1,

4].

Unexpectedly, detections of HPAI in U.S. dairy cattle have emerged, raising concerns about the virus’s capacity for cross-species transmission and adaptation [

5,

6]. While respiratory and oral routes remain the primary focus for transmission studies, the detection of HPAI RNA in non-traditional sample types such as raw milk has prompted new questions about alternative pathways for viral spread [

7,

8]. Bovine semen can be a vector for transmitting a variety of viral, bacterial, and protozoal pathogens, especially when proper screening and biosecurity measures are not in place [

9]. Hypothetically, the presence of HPAI virus in bovine semen could represent another potential risk factor, particularly given the widespread use of artificial insemination in the beef and dairy industry. In addition, foot and mouth disease virus (FMDV), a foreign animal disease in the United States, is detectable and can spread in semen [

9]. The potential shed of these viruses in semen could facilitate dissemination both within and between herds, including across geographic boundaries. At present, however, confirmations of HPAI detection in bull semen are lacking; the scenario of HPAI remains speculative, and FMDV is absent from the US. However, the topic is important for animal health surveillance and trade requirements.

Detection of viral RNA in semen presents unique technical challenges due to its viscosity, complex biochemical composition with high concentrations of proteins, nucleases, and polysaccharides, as well as lipid-rich seminal plasma, all of which can interfere with nucleic acid extraction efficiency and downstream amplification, leading to decreased assay sensitivity and the potential for false negatives [

9,

10,

11]. In addition, bovine semen extender is added to raw bull semen to preserve sperm viability and create multiple doses [

12,

13]. Extenders contain key components such as egg yolk, milk proteins, soy lecithin, or other plant-based derivatives, which shield the sperm cell membrane from physical and chemical damage, maintain optimal pH (6.8 - 7.2), and supply metabolizable sugars like fructose or glucose to fuel sperm motility [

12,

13]. Antibiotics are also included to control bacterial contamination, which can compromise sperm quality and transmit venereal diseases [

13]. However, proteins and lipids from extender components can act as PCR inhibitors, potentially complicating nucleic acid extraction and downstream assay performance.

Overcoming these numerous issues to obtain high-quality nucleic acid from semen often requires modified extraction protocols, inclusion of internal positive controls, and the use of reagents capable of mitigating inhibitory effects. As a result, two National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN)-approved extraction platforms, MagMAX CORE Nucleic Acid Purification Kit and IndiMag Pathogen Kit, were targeted for method development to ensure reliable detection of various pathogens in semen matrices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field and Reference Samples

Residual semen samples submitted to the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (WVDL) for routine diagnostic testing were pooled by submission and extender type to provide sufficient material for method evaluation. For routine diagnostic testing, three of the 0.25 cc semen straws per animal were pooled. Known negative residual straws from 3-4 animals per submission were combined to create 88 pooled field bovine semen samples for this study. The extended semen samples consisted of four categories: egg yolk-based extender (Yellow), milk-based extender sexed-semen (Green or Pink), and milk-based extender (White). All semen samples were stored in an ultralow freezer at −80°C until ready for use with the various extraction protocols.

A total of 36 naturally infected semen samples, as determined previously by the WVDL, were used for diagnostic sensitivity evaluation. The positive extended semen consisted of eight Mycoplasma bovis (M. bovis), five bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), and 23 bovine herpesvirus-1 (BHV-1) samples. Multiple frozen 0.25 cc semen straws from each of the infected animals were pooled into a homogenized mixture and stored in an ultralow freezer at −80°C until ready for use in the study.

To determine the limit of detection (LOD) for influenza A virus (IAV) in semen, three IAV reference strains were kindly provided by the National Veterinary Service Laboratories (NVSL) Diagnostic Virology Laboratory (Ames, IA) for the analytical sensitivity evaluation (

Appendix A,

Table A1). Ten-fold serial dilutions of the references were prepared in negative semen pools and stored in an ultralow freezer at −80 °C until ready for use.

Nine HxNx IAV strains (

Appendix A,

Table A1) at various concentrations were spiked into twenty-seven negative semen for sensitivity evaluation (see

Supplementary Table S7). Thirty previously negative field residual semen samples were used to evaluate diagnostic specificity. All samples were dispensed and stored in an ultralow freezer at −80°C until ready for use.

2.2. Extraction Chemistries and Equipment

The Thermo Fisher SCIENTIFIC MagMAX CORE Nucleic Acid Purification Kit (MagMAX CORE) (Thermo Fisher SCIENTIFIC, Waltham, MA, USA) and the INDICAL IndiMag Pathogen Kits (INDICAL BIOSCIENCE, Leipzig, Germany) approved by National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) for IAV, African swine fever virus, classical swine fever virus, and FMDV testing were evaluated [

14,

15,

16,

17]. The manufacturer’s recommended and several modifications of the MagMAX CORE and the IndiMag Pathogen Kit extraction protocols were compared and extracted using the Kingfisher Flex (Thermo Fisher SCIENTIFIC, Waltham, MA, USA).

For the MagMAX CORE extraction evaluation, each of the samples was extracted using the 200 µL sample input volume per kit instruction (CORE 200-na); a reduced 50 µL sample input volume (CORE 50-na); a reduced 50 µL sample input volume with a pretreatment process using 10 µL of proteinase K, 5 µL of 1M DTT, and 35 µL of 2% SDS with heating at 60°C for 5 minutes (CORE 50-pretreatment); and a reduced 12.5 µL sample input volume with above pretreatment process (CORE 12.5-pretreatment). When the sample input was less than 200 µL, 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was added to achieve a total input volume of 200 µL.

For the IndiMag Pathogen Kit extraction evaluation, samples were extracted using the 200 µL sample input volume per kit instruction (Pathogen 200-na); 100 µL semen and 100 µL PBS (Pathogen 100-na); and a 100 µL semen with a pretreatment process using 20 µL of proteinase K, with 90 µL of Buffer ATL (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) and heating and mixing at 56°C for 10 minutes (Pathogen 100-pretreament).

Two microliters of VetMAX Xeno Internal Positive Control RNA (Xeno RNA, Thermo Fisher SCIENTIFIC, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1 µL of the WVDL internal control (WVDL IC) were added to the lysis solution per sample for each extraction kit. The remainder of the extraction process was conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Eluted RNA was used for Polymerase Chain Reactions (PCR) evaluation or stored in an ultralow freezer at −80°C until ready for use.

2.3. Polymerase Chain Reactions (PCR)

The RNA extracted using the described methods was evaluated using the NAHLN IAV Matrix PCR assay (NAHLN assay) and the WVDL in-house influenza A Matrix PCR assay (WVDL assay). The NAHLN assay utilized AgPath-ID One Step PCR reagents (Thermo Fisher SCIENTIFIC, Waltham, MA, USA) and the VetMAX Xeno Internal Positive Control-VIC Assay for master mix per NVSL-SOP-0068 [

6]. The harmonized IAV thermocycling program was used on ABI 7500 (Thermo Fisher SCIENTIFIC, Waltham, MA, USA), and the IAV and Xeno RNA controls were analyzed at a 5% manual threshold value. A 5% manual threshold setting for Xeno RNA deviated from the auto threshold setting in the NAHLN NSVL-SOP-0068. The auto-threshold algorithm was influenced by the samples within each run, resulting in fluctuations between runs. The 5% manual threshold value for Xeno RNA accurately positioned the threshold around the midpoint of the log-linear phase for the Xeno RNA analysis across all runs. The NAHLN-approved protocols are available online:

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/lab_info_services/downloads/ApprovedSOPList.pdf. The NAHLN program office controls the distribution of protocols and the detailed information in the previously listed protocols; these can be requested by emailing NAHLN@usda.gov.

The WVDL IAV,

M. bovis, BVDV, and BHV-1 assays utilized the VetMAX Master Mix (Thermo Fisher SCIENTIFIC, Waltham, MA, USA). Each assay consisted of primers and probes for the pathogen and the WVDL IC (see

Supplementary Table S1) and 5 µL of extracted nucleic acids in a 15 µL reaction. A thermocycling program of 50°C for 5 minutes, 95°C for 10 minutes, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 3 seconds and 58°C for 30 seconds was used on ABI 7500 (Thermo Fisher SCIENTIFIC, Waltham, MA, USA). Analysis was performed at a 5% manual threshold value for the IAV,

M. bovis, BVDV, BHV-1, and WVDL IC.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The various pathogen and internal positive control targets with no amplification were assigned a cycle threshold (CT) value of 40 (the maximum cycle of the assays). The IAV assay performance was evaluated using LOD, the coefficient of correlation of the standard curve (R2), PCR efficiency, diagnostic sensitivity, and diagnostic specificity. A standard curve was generated using ten-fold dilutions for each of the reference viruses that were extracted in triplicate. The endpoint dilution of the reference strains determined the LOD, where all three replicates were detected. PCR efficiency and R2 were obtained from the standard curve generated by the ABI 7500 analysis software.

Repeatability within a single assay was assessed with the samples used for diagnostic sensitivity and specificity evaluation. Testing was performed on a second set of samples 4 months later to evaluate the inter-run repeatability and reproducibility.

Paired T-tests and Analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were used to infer statistical significance among various methods. The statistical analysis was performed using Prism software version 10.6.0 (GraphPad, Boston, MA, USA). Figures were generated using Tableau software, Public Edition (Salesforce, San Francisco, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Extraction Method Optimization

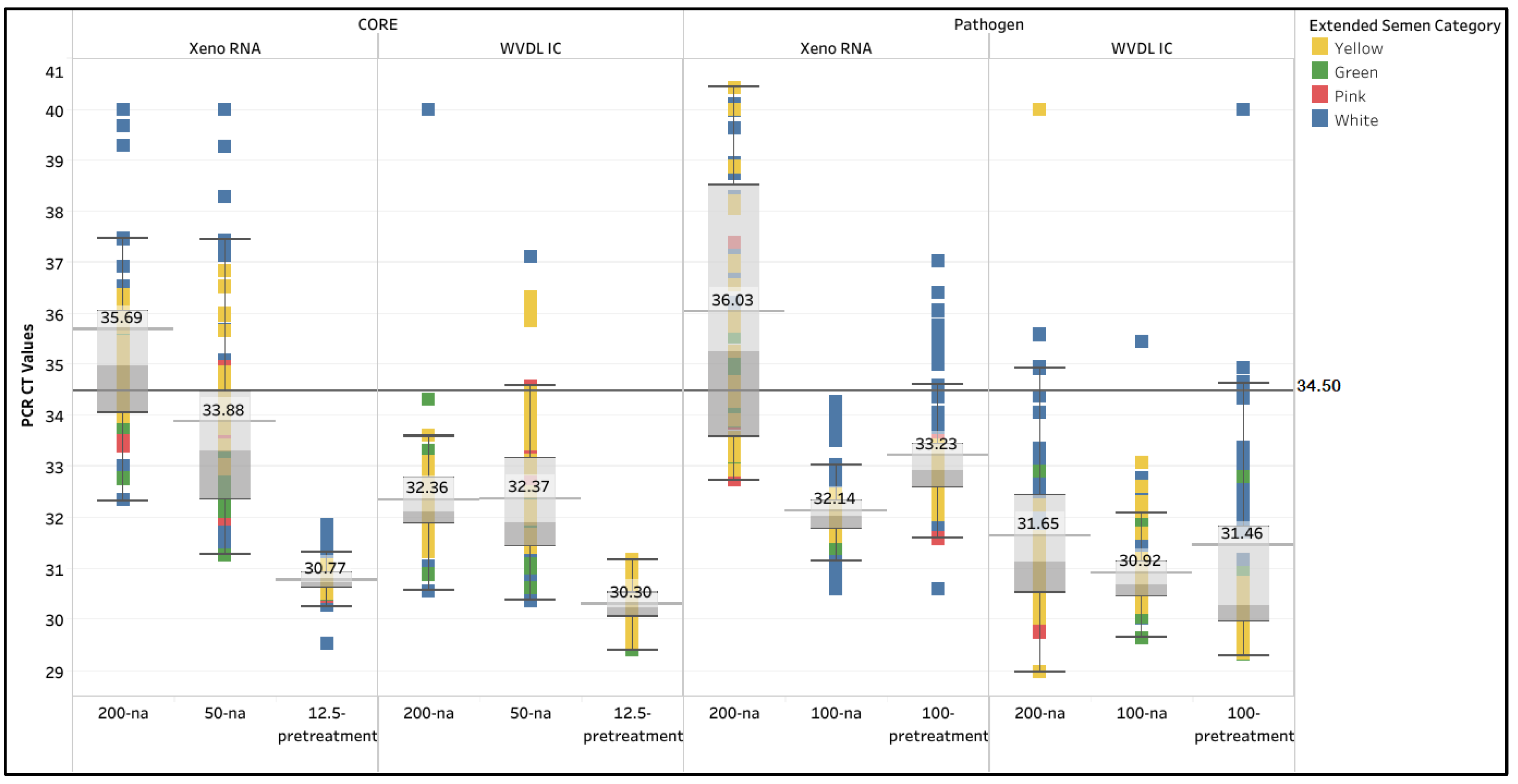

The first part of the study evaluated the current NALHN-approved extraction kits, the MagMAX CORE and IndiMag Pathogen kits. Each kit’s performance was evaluated using 88 negative extended semen samples and PCR analysis using Xeno RNA with the NAHLN IAV matrix and the WVDL IC with the WVDL in-house influenza A PCR assays. The effectiveness of the extraction protocol was determined by PCR amplification of the Xeno RNA and WVDL IC. Both PCRs were performed to 40 cycles. In accordance with the NAHLN acceptance criteria, the passing CT for Xeno RNA and WVDL IC was set at a CT value of < 34.5.

Using the manufacturer’s recommended sample input of 200 µL, the overall passing rate for the MagMax CORE was only 31.8% and 97.7.5% for Xeno RNA and WVDL IC, respectively. The overall passing rate for the IndiMag Pathogen was 37.5% and 94.3% for Xeno RNA and WVDL IC, respectively (

Table 1). The passing rate varied significantly (3.1% to 100%) depending on the type of semen extender and internal positive control; see

Table 1 and

Supplemental Table S2. Based on communication with the kit manufacturers, additional modifications were attempted. With CORE 50-pretreatment, the elution contained significant bead residue and could not be pipetted due to its clumpiness. Thus, 50 µL input without pretreatment (CORE 50-na) and a 12.5 µL input with pretreatment (CORE 12.5-pretreatment) were attempted. With the IndiMag Pathogen Kit, a 100 µL sample without pretreatment (Pathogen 100-na) and a 100 µL sample with pretreatment (Pathogen 100-pretreatment) were attempted.

Upon testing with the CORE 50-na, overall passing rate increased to 73.9% and 93.2% for the Xeno RNA and the WVDL IC, respectively, while the CORE 12.5-pretreatment overall passing rate was 100% for the Xeno RNA and the WVDL IC. For the Pathogen 100-na, the overall passing rate increased to 100% for the Xeno RNA and the WVDL IC. The Pathogen 100-pretreatment reduced the overall passing rate to 88.6% and 85.2% on the Xeno RNA and the WVDL IC, respectively. The CT values for the non-passing samples moved into the passing criteria as the successful modifications were applied (

Figure 1).

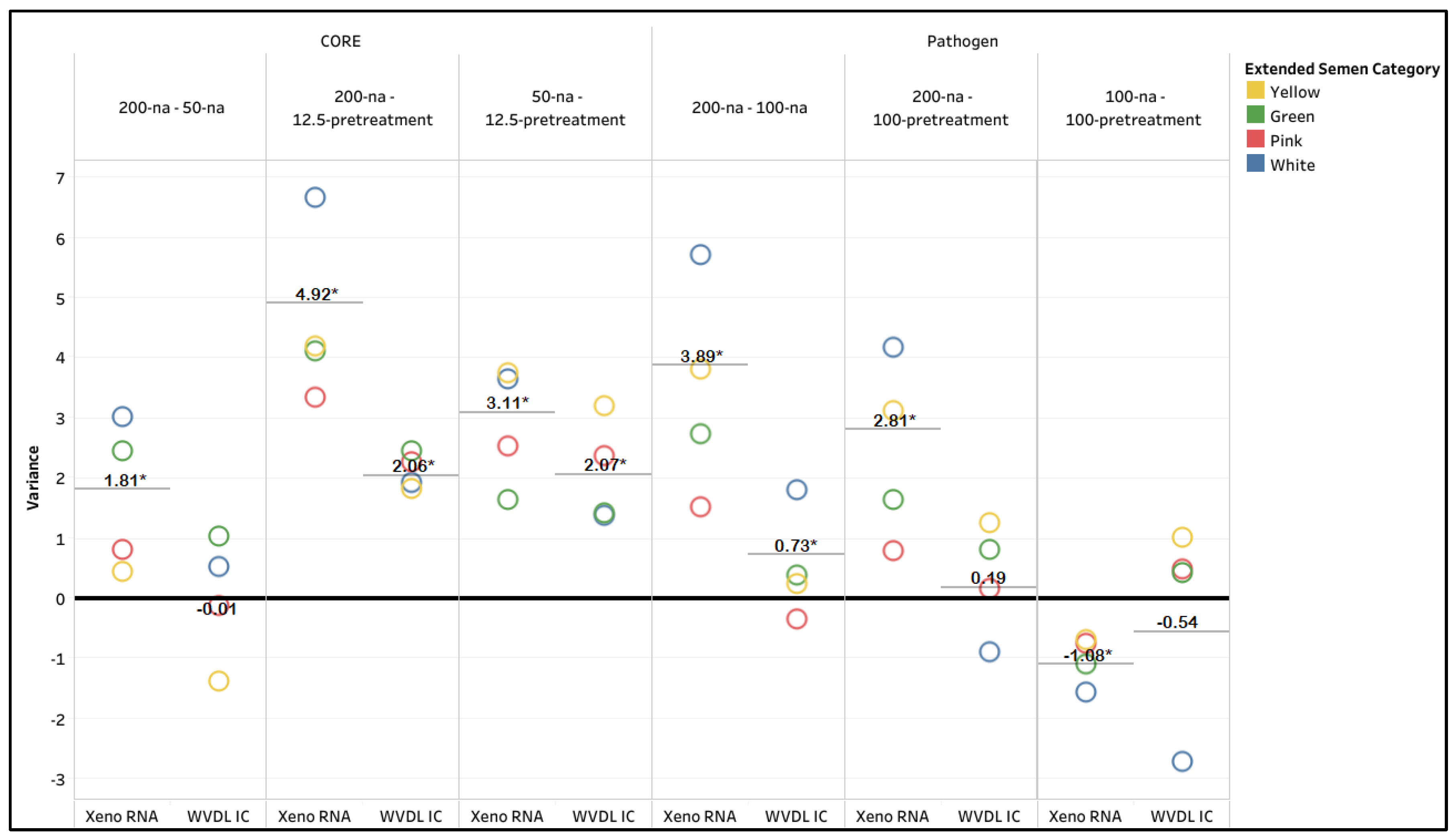

The CT values for the various methods were further analyzed. The internal positive control CT values ranged from 29.51 to 40 with the NAHLN assay and from 29.4 to 40 with the WVDL assay (

Figure 1,

Supplemental Table S2). For MagMAX CORE, reduced sample input (CORE 50-na) had minimal effect on the mean variance compared to CORE 200-na with the NAHLN and WVDL assays (

Figure 2,

Supplemental Table S3). However, the CORE 12.5-pretreatment drastically improved the CT values with the lowest and tightest CT range (29.51 - 31.85 and 29.4 - 31.17 for the NAHLN and WVDL assays, respectively) and highest variance, demonstrating successful modification of the protocol for minimizing PCR inhibitory effects. A significant difference in CT values was observed for improvement from CORE 200-na to CORE 50-na on the NAHLN assay and to CORE 12.5-pretreatment for both the NAHLN and WVDL assays (Paired ANOVA test, p < 0.0001).

For the Pathogen Kit, major improvements were achieved by reducing the sample input volume (Pathogen 100-na) or by incorporating additional pretreatment steps at the reduced volume (Pathogen 100-pretreatment) (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The pretreatment provided no further improvement to the reduced volume samples (see

Figure 2 and

Supplemental Table S3). The CT value for Pathogen 100-na ranged from 30.61 to 34.28 and 29.64 to 35.43 for the NAHLN and WVDL assays, respectively. The CT value for Pathogen 100-pretreatment ranged from 30.6 to 37.06 for the NAHLN assay and 29.30 to 40.0 for the WVDL assay. The PCR inhibitory effect seemed to be overcome by simply reducing the sample input to half of the recommended volume for this kit. A significant difference in CT values was observed for improvement from Pathogen 200-na to Pathogen 100-na for both the NAHLN and WVDL assays and to Pathogen 100-pretreatment on the NAHLN assay (Paired ANOVA test, p < 0.0001))

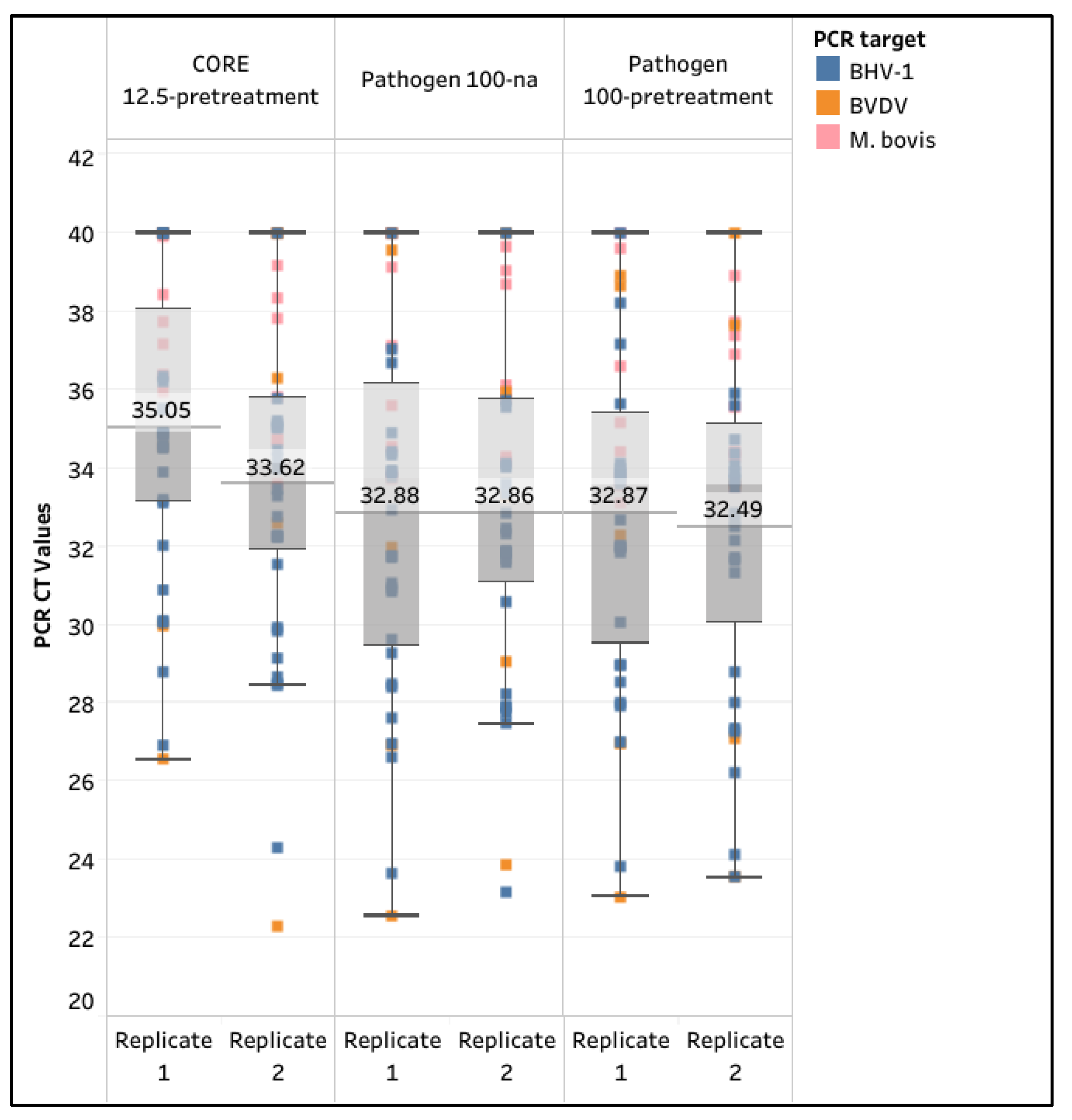

3.2. Evaluation of Diagnostic Sensitivity for the Selected Extraction Protocols

A total of 36 naturally infected extended semen samples with

M. bovis (n=8), BVDV (n=5), or BHV-1 (n=23) were extracted in duplicate using separate extractions for the CORE 12.5-pretreatment, Pathogen 100-na, and Pathogen 100-pretreatment protocols with the WVDL pathogen-specific assays (

Table 2). The Core 12.5-pretreatment and the Pathogen 100-na were selected based on the 100% passing rate for internal positive controls; the Pathogen 100-pretreatment was also included to investigate the effect of pretreatment in naturally infected samples. Samples with a pathogen CT value less than 40 were considered positive, regardless of the CT value of the internal positive controls.

The diagnostic sensitivity of the CORE 12.5-pretreatment was the lowest, with one replicate at 80.6%, while the Pathogen 100-pretreatment had the highest sensitivity, with one replication at 97.2%. One replication of the Pathogen 100-na shared the same sensitivity as the other CORE 12.5-pretreatment replicate (88.9%), while the other replicate had the same sensitivity as Pathogen 100-pretreatment (94.9%). The overall mean CT values for the CORE 12.5-pretreatment were 35.05 (95% CI: 33.76 - 36.35) and 33.62 (95% CI: 32.2 - 35.04), while the Pathogen 100-na CT values were 32.88 (95% CI: 31.29 - 34.46) and 32.86 (95% CI: 31.45 - 34.27), and the Pathogen 100-pretreatment CT values were 32.88 (95% CI: 31.41 - 33.34) and 32.49 (95% CI: 31.05 - 33.94), respectively. Overall, the Pathogen 100-na and Pathogen 100-pretreatment protocols provided higher detection rates and lower mean CT values for

M. bovis, BVDV and BHV-1, indicating significantly better diagnostic sensitivity compared to the CORE 12.5-pretreatment protocol (ANOVA test,

p < 0.0001), while a lack of significant difference existed between Pathogen 100-na and Pathogen 100-pretreatment protocols (Paired T test, p = 0.3849) (

Figure 3, and

Supplemental Table S4).

3.3. Evaluation of Performance for IAV Assays

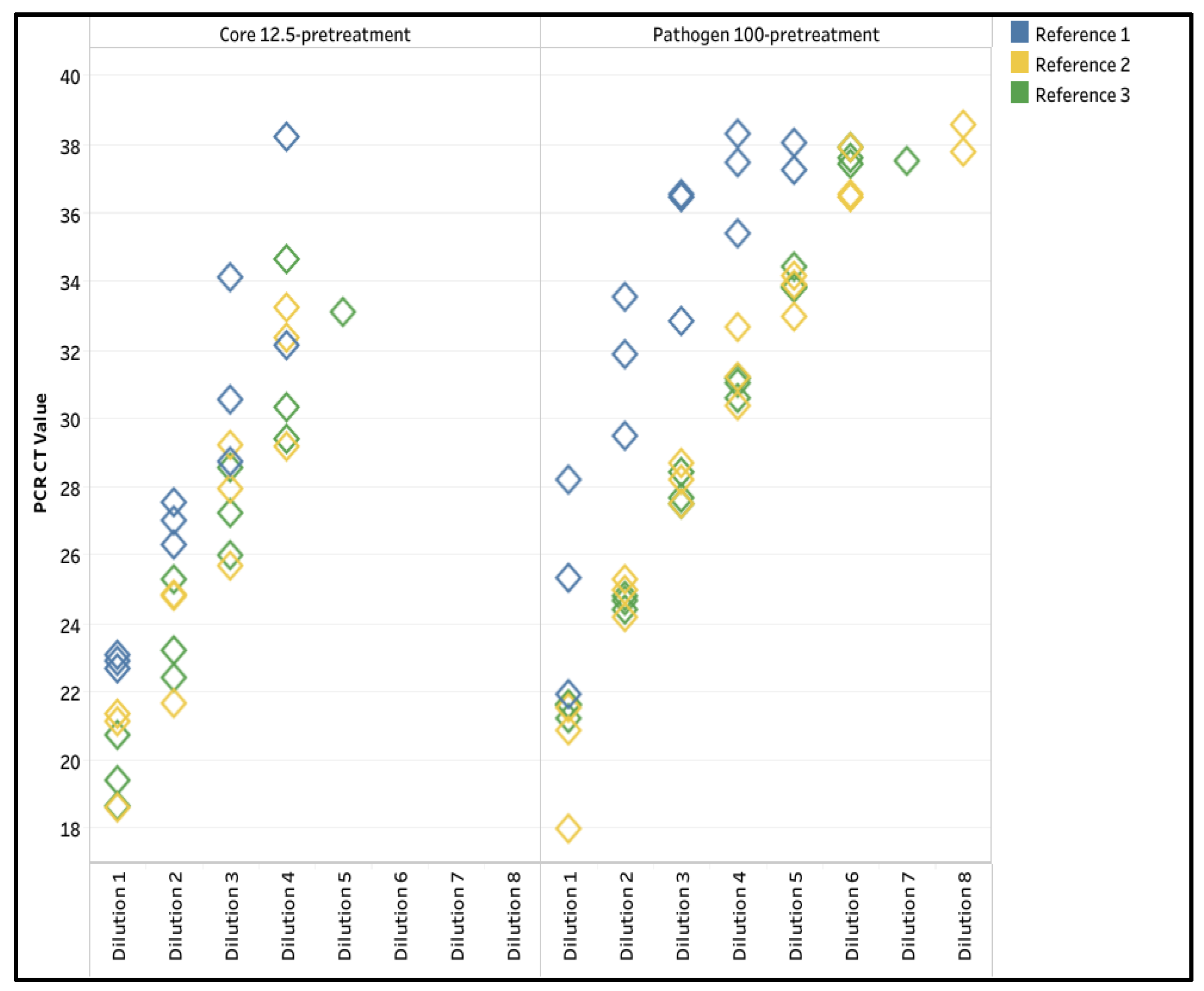

Three low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) virus reference strains were used to evaluate the analytical sensitivity of the extraction protocol for the IAV assays. Ten-fold serial dilutions of the references were prepared in negative semen pools (White, Yellow, and Green). Initially, the CORE 12.5-pretreatment and Pathogen 100-pretreatment were evaluated, using the NAHLN assay. For reference strain 1, the LODs for CORE 12.5-pretreatment and Pathogen 100-pretreatment appeared inaccurate, and Xeno RNA failed in 11 of the 24 PCR reactions. The CORE 12.5-pretreatment had a 2-log reduction in sensitivity compared to Pathogen 100-pretreatment (

Figure A1 and

Supplemental Table S5). The data suggested the heat treatments were negatively affecting the artificially spiked samples. Further evaluation was not completed with these two protocols.

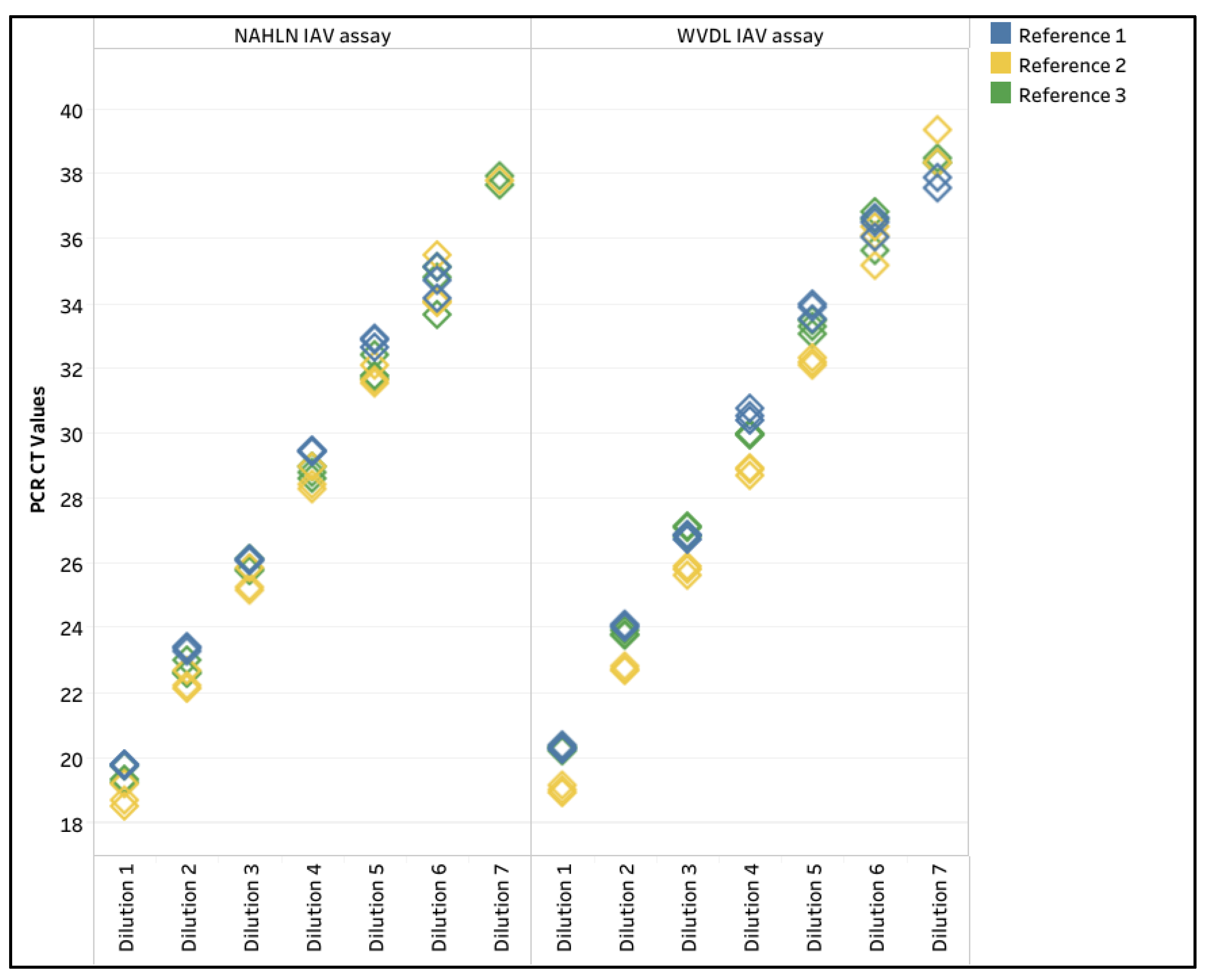

The IndiMag Pathogen 100-na was evaluated for the remainder of the study. Three replicates of the three LPAI IAV reference strains were evaluated with the NAHLN and WVDL PCR assays. The LOD for the three reference strains was 6 dilutions for both the NAHLN and WVDL PCR assays (

Table 3 and

Figure 4). Dilution 7 was detected once or twice out of the three replicates for reference strains 2 and 3 for the NAHLN and WVDL PCR assays (

Table 3). The R

2values ranged from 0.990 to 0.999, with the percent PCR efficiency ranging between 97.8% and 120.7%.

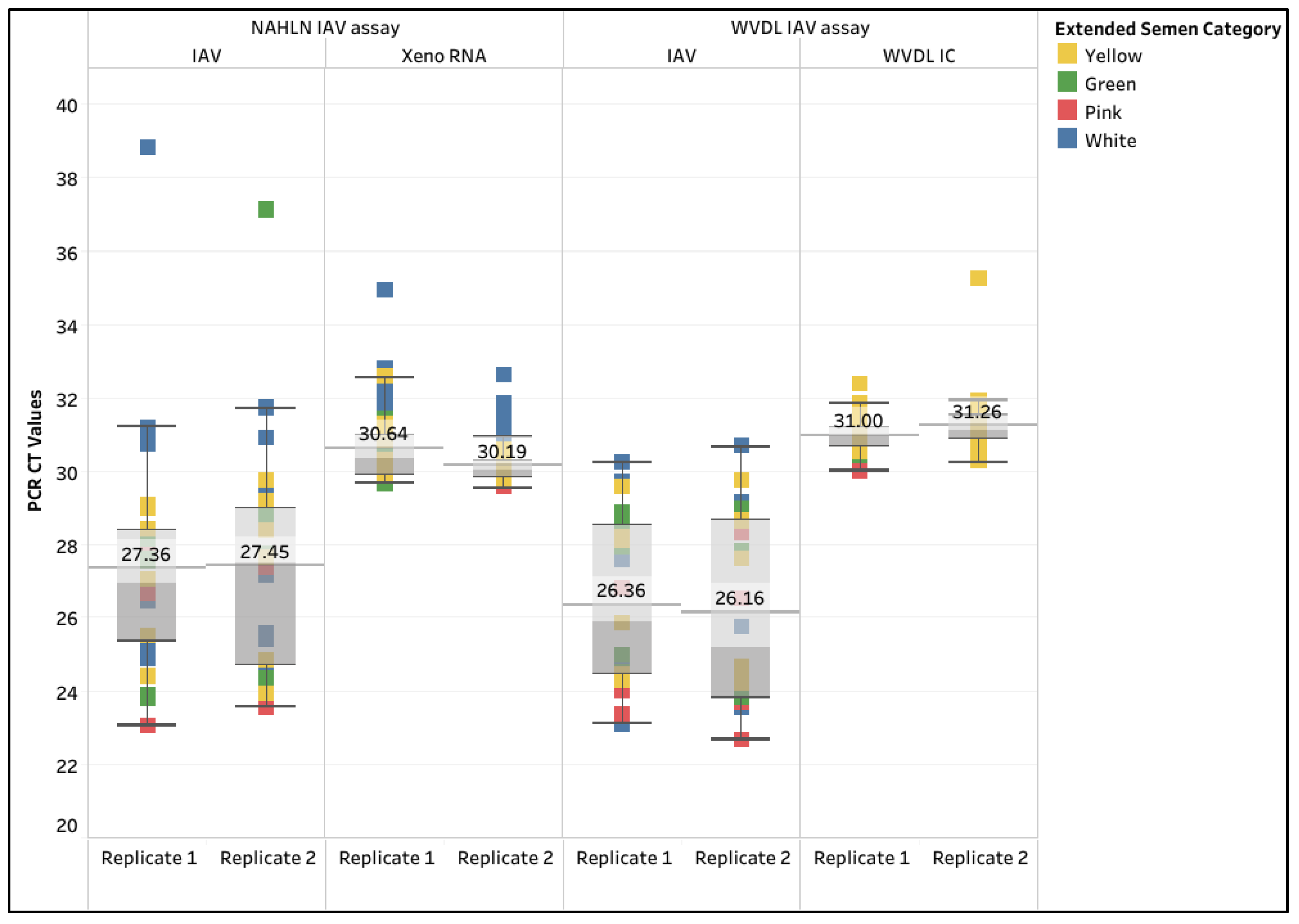

For diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, a total of 27 IAV spiked-positive and 30 negative extended semen samples were evaluated using the NAHLN and WVDL PCR assays. The inter-run repeatability was assessed by extracting the same set of samples four months after the initial extraction. The overall mean CT values for the IAV using the NAHLN assay were 26.92 (95% CI: 26.04 - 27.79) and 27.12 (95% CI: 26.20 - 28.04), while the IAV CT values using the WVDL assay were 26.26 (95% CI: 25.37 - 27.16) and 26.11 (95% CI: 25.14 - 27.09), respectively. The overall mean CT values for the Xeno RNA were 30.66 (95% CI: 30.39 - 30.92) and 30.22 (95% CI: 30.05 - 30.39), while the WVDL IC CT values were 30.99 (95% CI: 30.88 - 31.11) and 31.26 (95% CI: 31.08 - 31.43), respectively (

Figure 5 and

Supplemental Table S6). One hundred percent diagnostic sensitivity and specificity were achieved for the evaluated samples.

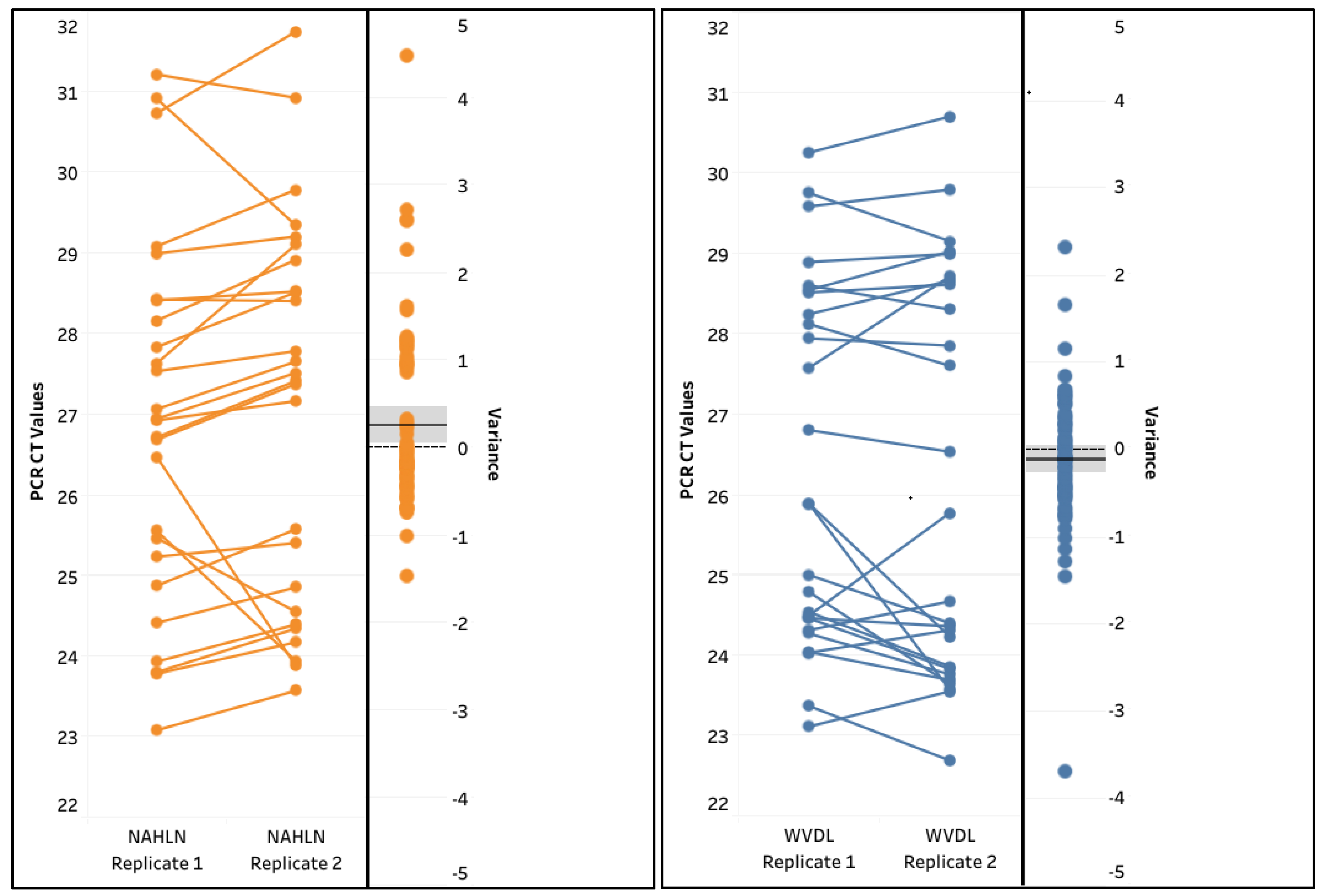

The repeatability and reproducibility of the method were assessed through a pairwise comparison of the two sets of replicated testing. Overall, excellent correlations were observed among the positive replicates, Pearson correlation coefficients, r = 0.9215 and r = 0.9448 for the NAHLN and WVDL assays, respectively (

Figure 6). There was a lack of significant difference between the IAV CT values among the two replicates (Paired T test, p = 0.2556 and p = 0.3557 for the NAHLN and WVDL assays, respectively). The cross-classification of the positive/negative results was 100% in agreement for all 57 samples. The data suggested excellent repeatability and reproducibility of the Pathogen 100-na extraction method.

4. Discussion

PCR inhibition is a common problem in veterinary diagnostics because animal samples often contain proteins, lipids, and other compounds, and storage before testing can further interfere with nucleic acid extraction and reduce assay sensitivity, potentially generating false negatives [

18]. Effective isolation of pathogen nucleic acids using commercial nucleic acid extraction kits relies on successfully releasing and purifying intact DNA or RNA from infected cells/tissues, while efficiently eliminating potential PCR inhibitors and nucleases during the extraction process. In this study, the two NAHLN-approved extraction kits, MagMax CORE and IndiMag Pathogen, were evaluated for detecting high-consequence diseases in various sample types, including swabs, tissues, milk, and whole blood [

14,

15,

16,

17]. These kits were rapidly adapted for IAV surveillance in milk, enabling reliable detection and streamlining the laboratory’s surveillance testing. Optimizing the semen extraction protocols for these kits can streamline the detection and surveillance of common pathogens and high-consequence diseases, such as FMDV and potentially HPAI, during an outbreak.

The high occurrence of inhibitors in animal samples, particularly in semen with disulfide-linked nuclear proteins and lipid-rich seminal plasma, can be addressed by optimizing lysis chemistries using Proteinase K, detergents, reducing agents, and heat treatments to disrupt protein complexes and enhance nucleic acid recovery [

19,

20,

21,

22]. In our evaluation of extended semen samples, the manufacturer-recommended MagMax CORE protocol (CORE 200-na) and IndiMag Pathogen Kit protocol (Pathogen 200-na), and reduced-input modification (CORE 50-na), did not sufficiently remove inhibition, consistent with the challenges described for other veterinary matrices [

18,

19]. Interestingly, the standard IndiMag Pathogen Kit with half the sample input (Pathogen 100-na) reduced inhibition, possibly due to the kit’s third wash step containing 100% ethanol to remove additional inhibitors. With the CORE kit, a reduced sample volume in combination with Proteinase K, DTT, SDS, and heat pretreatment (CORE 12.5-pretreatment) was effective to remove inhibition, while adding half the input volume with the IndiMag Pathogen Kit (Pathogen 100-na) was slightly better at removing inhibition compared to the addition of Buffer ATL and heat pretreatment (Pathogen 100-pretreatment).

While reducing sample input can help minimize PCR inhibition, lower sample volume may also decrease the sensitivity of pathogen detection. Thus, subsequent testing of naturally infected field samples containing

M. bovis, BVDV, or BHV-1 was conducted to verify that both the modified CORE (CORE 12.5-pretreatment) and Pathogen Kit (Pathogen 100-na and Pathogen 100-pretreatment) protocols achieved high sensitivity for pathogen detection, with a slight performance advantage for the Pathogen 100-pretreatment. A similar effect also occurred when optimizing the extractions for the surveillance of IAV in milk samples [

23]. In veterinary diagnostics, careful monitoring of inhibition is critical to avoid reporting of false-negative results, leading to the spread of disease [

18,

24].

Due to the lack of naturally IAV-infected semen, the evaluation for IAV was conducted using spiked semen samples. While improvement was observed with the pretreatment protocols (CORE 12.5-pretreatment and Pathogen 100-pretreatment) for naturally infected samples, the pretreatment may have had a negative impact on the extracellularly spiked virus. The Pathogen 100-na protocol achieved high sensitivity for speculative IAV detection and provides the framework for validating this protocol for FMDV detection, if a US outbreak were to occur. A well-developed semen extraction protocol is important for the detection of FMDV, which can be found in semen and spread through artificial insemination [

25]. If FMDV were to spread to the United States, the economic and animal health consequences would be devastating, making rapid and reliable semen testing protocols essential for prevention and control [

26]. Establishing standardized nucleic acid extraction and pretreatment strategies that preserve viral integrity while removing inhibitors inherent to semen is crucial to ensure sensitive and specific detection, limit the spread of endemic and exotic pathogens through germplasm exchange, and support international biosecurity measures [

27].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights the critical role of optimizing nucleic acid extraction protocols to overcome PCR inhibition in milk-based and egg-based extended semen samples. While reducing sample input volumes and incorporating pretreatments effectively minimized inhibition, a balance must be struck between inhibitor removal and preserving viral integrity to maintain assay sensitivity. Validation with both naturally infected and spiked samples demonstrated that refined extraction protocols can support the reliable detection of viruses and bacteria, including high-consequence pathogens such as HPAI and FMDV.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Table S1: Primers and probes information for the Mycoplams bovis, bovine viral diarrhea virus and bovine herpesvirus-1 PCR assays. Table S2: CT values and variance for the NAHLN IAV Matrix and the WVDL in-house influenza A PCR assays for the 88 negative semen samples using the various methodologies with the MagMAX CORE (CORE) and the IndiMag Pathogen (Pathogen) kits. Table S3: Variance between the extraction methods for the MagMAX CORE and the IndiMag Pathogen Kits using 88 negative semen samples. RNA was evaluted using the NAHLN IAV Matrix and the WVDL in-house influenza A PCR assays. Table S4: CT values for M. bovis, BVDV, or BHV-1 specific PCR assays to assess the extraction method sensitivity for the modified MagMAX CORE (CORE) and the modified IndiMag Pathogen (Pathogen) kits extraction protocols using 36 naturally-infected semen samples. Table S5: CT values for NAHLN IAV Matrix PCR assay to assess the modified MagMAX CORE (CORE) and the modified IndiMag Pathogen (Pathogen) kits extraction protocols with the influenza A virus-spiked samples. Table S6: CT values for NAHLN IAV and WVDL in-house influenza A PCR assays to assess the reduced input (100 µL) IndiMag Pathogen Kit extraction protocol with the influenza A virus-spiked standard curves. Table S7: CT values for the NAHLN IAV and WVDL in-house influenza A PCR assays to assess the sensitivity and specificity for the reduced input (100 µL) IndiMag Pathogen Kit extraction protocol with the influenza A virus-spiked samples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M. and A.L.; methodology, A.Z., D.M., and A.L.; software, A.V.C. and A.L.; validation, A.Z., A.V.C., D.M., and A.L.; formal analysis, A.Z., D.M., and A.L.; investigation, A.Z., A.V.C., D.M., and A.L.; resources, A.L.; data curation, A.Z., A.V.C., and A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Z., A.V.C., D.M., and A.L.; writing—review and editing, A.Z., A.V.C., D.M., and A.L.; visualization, A.V.C. and A.L.; supervision, A.L.; project administration, A.L.; funding acquisition, A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

WVDL funded the personnel and reagents for the study. INDICAL BIOSCIENCE provided some of the IndiMag Pathogen Kits for the study. This research received no extramural funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We thank the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Veterinary Services Laboratory for providing reference materials for this study; ThermoFisher SCIENTIFIC and INDICAL BIOSCIENCE Research & Development teams for their technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors (A.Z., A.V.C., and A.L.) declare no conflicts of interest. D.M. is employed by INDICAL BIOSCIENCE, which provided some IndiMag Pathogen Kits for the study, participated in the design of the study, data analyses, and writing of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

ANOVA

BHV-1

BVDV

CT |

Analysis of Variance

Bovine herpesvirus-1

Bovine viral diarrhea virus

Cycle threshold |

FMDV

HPAI |

Foot and mouth disease virus

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza |

| IAV |

Influenza A virus |

| LOD |

Limit of detection |

| LPAI |

Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza |

| MagMAX CORE |

MagMAX CORE Nucleic Acid Purification Kit |

M. bovis

NAHLN

NVSL |

Mycoplasma bovis

National Animal Health Laboratory Network

National Veterinary Service Laboratories |

PBS

PCR |

Phosphate-buffered saline

Polymerase chain reactions |

| R2

|

Coefficient of correlation of the standard curve |

Xeno RNA

WVDL |

VetMAX Xeno Internal Positive Control RNA

Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory |

| WVDL IC |

WVDL internal control |

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of low pathogenic influenza A viruses used as reference strains and for generation of positive IAV samples for diagnostic sensitivity evaluation.

Table A1.

List of low pathogenic influenza A viruses used as reference strains and for generation of positive IAV samples for diagnostic sensitivity evaluation.

| IAV |

Subtype |

Strain ID |

| IAV reference 1 |

H9N2 |

Influenza A Virus A/Turkey/CA/6889/1980 |

| IAV reference 2 |

H5N9 |

Influenza A Virus A/Turkey/Wisconsin/1968 |

| IAV reference 3 |

H7N3 |

Influenza A Virus A/Turkey/Oregon/1977 |

| LPAI 1 |

H3N8 |

Influenza A Virus A/Equine/Miami/1/63 |

| LPAI 2 |

H1N7 |

Influenza A Virus A/NJ/8/76/EQ-1 |

| LPAI 3 |

HON3 |

Influenza A Virus A/NWS-NOV2 |

| LPAI 4 |

H10N7 |

Influenza A Virus A/CK/GERM/49 |

| LPAI 5 |

H2N3 |

Influenza A Virus A/Mallard/A16/77 |

| LPAI 6 |

H4N8 |

Influenza A Virus A/MYNAH/Mass/71 |

| LPAI 7 |

H7N3 |

Influenza A Virus A/TY/ORE |

| LPAI 8 |

H4N8 |

Influenza A Virus A/DK/England/62 |

| LPAI 9 |

H3N8 |

Influenza A Virus A/DK/Ukraine/1/63 |

Figure A1.

Standard curve for the three influenza A (IAV) reference strains in different extended semen using the MagMax CORE with 12.5 µL semen input and pretreatment (CORE 12.5-pretreatment) and the IndiMag Pathogen Kit with 100 µL semen input and pretreatment (Pathogen 100-pretreatment) on the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) IAV assay. Reference 1 was spiked into negative semen with milk-based extender (White), Reference 2 was spiked into negative semen with egg yolk-based extender (Yellow), and Reference 3 was spiked into negative milk-based sexed-semen extender (Green).

Figure A1.

Standard curve for the three influenza A (IAV) reference strains in different extended semen using the MagMax CORE with 12.5 µL semen input and pretreatment (CORE 12.5-pretreatment) and the IndiMag Pathogen Kit with 100 µL semen input and pretreatment (Pathogen 100-pretreatment) on the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) IAV assay. Reference 1 was spiked into negative semen with milk-based extender (White), Reference 2 was spiked into negative semen with egg yolk-based extender (Yellow), and Reference 3 was spiked into negative milk-based sexed-semen extender (Green).

References

- Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE. H5N1 Influenza. H5N1 Influenza. Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-detections?utm (accessed 2025-09-27).

- American Veterinary Medical Association. Avian Influenza Virus Type A (H5N1) in U.S. Dairy Cattle. Available online: https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/animal-health-and-welfare/animal-health/avianinfluenza/avian-influenza-virus-type-h5n1-us-dairy-cattle (accessed 2025-09-27).

- Fourment, M.; Darling, A. E.; Holmes, E. C. The Impact of Migratory Flyways on the Spread of Avian Influenza Virus in North America. BMC Evol. Biol. 2017, 17 (1), 118.

- Congressional Research Service; Biondo. The Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) Outbreak in Poultry, 2022-Present; R48518; 2025. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R48518 (accessed 2025-09-27).

- Burrough, E. R.; Magstadt, D. R.; Petersen, B.; Timmermans, S. J.; Gauger, P. C.; Zhang, J.; Siepker, C.; Mainenti, M.; Li, G.; Thompson, A. C.; Gorden, P. J.; Plummer, P. J.; Main, R. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Clade 2.3.4.4b Virus Infection in Domestic Dairy Cattle and Cats, United States, 2024. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30 (7), 1335–1343. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid3007.240508. [CrossRef]

- Caserta, L. C.; Frye, E. A.; Butt, S. L.; Laverack, M.; Nooruzzaman, M.; Covaleda, L. M.; Thompson, A. C.; Koscielny, M. P.; Cronk, B.; Johnson, A.; Kleinhenz, K.; Edwards, E. E.; Gomez, G.; Hitchener, G.; Martins, M.; Kapczynski, D. R.; Suarez, D. L.; Alexander Morris, E. R.; Hensley, T.; Beeby, J. S.; Lejeune, M.; Swinford, A. K.; Elvinger, F.; Dimitrov, K. M.; Diel, D. G. Spillover of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Virus to Dairy Cattle. Nature 2024, 634 (8034), 669–676. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07849-4. [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Eisfeld, A. J.; Pattinson, D.; Gu, C.; Biswas, A.; Maemura, T.; Trifkovic, S.; Babujee, L.; Presler, R.; Dahn, R.; Halfmann, P. J.; Barnhardt, T.; Neumann, G.; Thompson, A.; Swinford, A. K.; Dimitrov, K. M.; Poulsen, K.; Kawaoka, Y. Cow’s Milk Containing Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus — Heat Inactivation and Infectivity in Mice. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391 (1), 87–90. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2405495. [CrossRef]

- Frye, E. A.; Nooruzzaman, M.; Cronk, B.; Laverack, M.; Oliveira, P. S. B. de; Caserta, L. C.; Lejeune, M.; Diel, D. G. Isolation of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus from Cat Urine after Raw Milk Ingestion, United States - Volume 31, Number 8—August 2025 - Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal - CDC. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid3108.250309. [CrossRef]

- Givens, M. D. Review: Risks of Disease Transmission through Semen in Cattle. Animal 2018, 12, s165–s171. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731118000708. [CrossRef]

- Samanta, L.; Parida, R.; Dias, T. R.; Agarwal, A. The Enigmatic Seminal Plasma: A Proteomics Insight from Ejaculation to Fertilization. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018, 16 (1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-018-0358-6. [CrossRef]

- Gautier, C.; Aurich, C. “Fine Feathers Make Fine Birds” – The Mammalian Sperm Plasma Membrane Lipid Composition and Effects on Assisted Reproduction. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 246, 106884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anireprosci.2021.106884. [CrossRef]

- Raheja, N.; Choudhary, S.; Grewal, S.; Sharma, N.; Kumar., N. A Review on Semen Extenders and Additives Used in Cattle and Buffalo Bull Semen Preservation. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 6 (3), 293–245.

- Bodu, M.; Hitit, M.; Greenwood, O. C.; Murray, R. D.; Memili, E. Extender Development for Optimal Cryopreservation of Buck Sperm to Increase Reproductive Efficiency of Goats. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2025.1554771. [CrossRef]

- National Animal Health Laboratory Network. Standard operating procedure for Real-time RT-PCR Detection of Influenza A and Avian Paramyxovirus Type-1. (NVSL-SOP-0068). Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/lab_info_services/downloads/ ApprovedSOPList.pdf (accessed 2025-09-26).

- National Animal Health Laboratory Network. Standard operating procedure for Nucleic Acid Extraction Using the MagMAX Core Nucleic Acid Purification Kit on a Magnetic Particle Processor. (NVSL-SOP-0643). Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/lab_info_services/downloads/ApprovedSOPList.pdf (accessed 2025-09-26).

- National Animal Health Laboratory Network. Standard operating procedure for Nucleic Acid Extraction Using the INDICAL BIOSCIENCE IndiMag Pathogen Kit on a Magnetic Particle Processor. (NVSL-SOP-0645). Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/lab_info_services/downloads/ApprovedSOPList.pdf (accessed 2025-09-26).

- Vandenburg-Carroll, A.; Marthaler, D. G.; Lim, A. Enhancing Diagnostic Resilience: Evaluation of Extraction Platforms and IndiMag Pathogen Kits for Rapid Animal Disease Detection. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16 (4), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16040080. [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Toohey-Kurth, K. L.; Crossley, B. M.; Bai, J.; Glaser, A. L.; Tallmadge, R. L.; Goodman, L. B. Inhibition Monitoring in Veterinary Molecular Testing. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Vet. Lab. Diagn. Inc 2020, 32 (6), 758–766. https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638719889315. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. M.; Balakrishnan, H. K.; Doeven, E. H.; Yuan, D.; Guijt, R. M. Chemical Trends in Sample Preparation for Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing (NAAT): A Review. Biosensors 2023, 13 (11), 980. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios13110980. [CrossRef]

- Schellhammer, S. K.; Hudson, B. C.; Cox, J. O.; Dawson Green, T. Alternative Direct-to-amplification Sperm Cell Lysis Techniques for Sexual Assault Sample Processing. J. Forensic Sci. 2022, 67 (4), 1668–1678. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.15027. [CrossRef]

- Hennekens, C. M.; Cooper, E. S.; Cotton, R. W.; Grgicak, C. M. The Effects of Differential Extraction Conditions on the Premature Lysis of Spermatozoa. J. Forensic Sci. 2013, 58 (3), 744–752. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.12098. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Sekiguchi, K.; Mizuno, N.; Kasai, K.; Sakai, I.; Sato, H.; Seta, S. The Modified Method of Two-Step Differential Extraction of Sperm and Vaginal Epithelial Cell DNA from Vaginal Fluid Mixed with Semen. Forensic Sci. Int. 1995, 72 (1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/0379-0738(94)01668-U. [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.-C.; Lin, C.-C.; Chen, Y.-M.; Cheng, M.-C.; Davison, S.; Ma, J.; Dai, H.-L. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Detection of Inactivated H5 Avian Influenza Virus in Raw Milk Samples by Miniaturized Instruments Designed for On-Site Testing. bioRxiv 2025, 2025.06.02.657307. https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.06.02.657307. [CrossRef]

- Miller, M. R.; Braun, E.; Ip, H. S.; Tyson, G. H. Domestic and Wild Animal Samples and Diagnostic Testing for SARS-CoV-2. Vet. Q. 43 (1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/01652176.2023.2263864. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Subramaniam, S.; De, A.; Das, B.; Dash, B.; Sanyal, A.; Misra, A.; Pattnaik, B. Detection of Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus in Semen of Infected Cattle Bulls. Indian J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 82, 1472–1476.

- Alexandersen, S.; Zhang, Z.; Donaldson, A. I.; Garland, A. J. M. The Pathogenesis and Diagnosis of Foot-and-Mouth Disease. J. Comp. Pathol. 2003, 129 (1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9975(03)00041-0. [CrossRef]

- World Organisation for Animal Health. Foot and Mouth Disease; OIE Terrestrial Manual 2009. Available online: https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Animal_Health_in_the_World/docs/pdf/2.01.05_FMD.pdf (accessed 2025-09-26).

Figure 1.

Box and whisker plot illustrating the Xeno RNA and Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory internal control (WVDL IC) CT values for each semen sample using the MagMAX CORE (CORE) with 200 µL semen input (200-na), 50 µL semen input (50-na), and 12.5 µL semen input with pretreatment (12.5-pretreatment); and the IndiMag Pathogen Kit (Pathogen) with 200 µL semen input (200-na), 100 µL semen input (100-na), and 100 µL semen input with pretreatment (100-pretreatment). The categories of semen extenders are egg yolk-based (Yellow), sexed milk-based (Green or Pink), and milk-based (White). The passing CT value criteria of 34.50 is represented by the black colored horizontal line.

Figure 1.

Box and whisker plot illustrating the Xeno RNA and Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory internal control (WVDL IC) CT values for each semen sample using the MagMAX CORE (CORE) with 200 µL semen input (200-na), 50 µL semen input (50-na), and 12.5 µL semen input with pretreatment (12.5-pretreatment); and the IndiMag Pathogen Kit (Pathogen) with 200 µL semen input (200-na), 100 µL semen input (100-na), and 100 µL semen input with pretreatment (100-pretreatment). The categories of semen extenders are egg yolk-based (Yellow), sexed milk-based (Green or Pink), and milk-based (White). The passing CT value criteria of 34.50 is represented by the black colored horizontal line.

Figure 2.

Xeno RNA and Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory internal control (WVDL IC) CT value variance between the different extraction methods using MagMax CORE (CORE) with 200 µL semen input (200-na), 50 µL semen input (50-na), and 12.5 µL semen input with pretreatment (12.5-pretreatment); and the IndiMag Pathogen Kit (Pathogen) with 200 µL semen input (200-na), 100 µL semen input (100-na), and 100 µL semen input with pretreatment (100-pretreatment). The categories of semen extenders are egg yolk-based (Yellow), sexed milk-based (Green or Pink), and milk-based (White). * indicates significance with p < 0.0001.

Figure 2.

Xeno RNA and Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory internal control (WVDL IC) CT value variance between the different extraction methods using MagMax CORE (CORE) with 200 µL semen input (200-na), 50 µL semen input (50-na), and 12.5 µL semen input with pretreatment (12.5-pretreatment); and the IndiMag Pathogen Kit (Pathogen) with 200 µL semen input (200-na), 100 µL semen input (100-na), and 100 µL semen input with pretreatment (100-pretreatment). The categories of semen extenders are egg yolk-based (Yellow), sexed milk-based (Green or Pink), and milk-based (White). * indicates significance with p < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

Box and whisker plot illustrating the Mycoplasma bovis (M. bovis), bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), and bovine herpesvirus-1 (BHV-1) positive extended semen samples with passing internal controls using the MagMAX CORE KIT (CORE) extraction with 12.5 µL semen input and pretreatment (12.5-pretreatment) and using the IndiMag Pathogen Kit (Pathogen) with 100 µL semen input (100-na) and 100 µL semen input with pretreatment (100-pretreatment) extractions.

Figure 3.

Box and whisker plot illustrating the Mycoplasma bovis (M. bovis), bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), and bovine herpesvirus-1 (BHV-1) positive extended semen samples with passing internal controls using the MagMAX CORE KIT (CORE) extraction with 12.5 µL semen input and pretreatment (12.5-pretreatment) and using the IndiMag Pathogen Kit (Pathogen) with 100 µL semen input (100-na) and 100 µL semen input with pretreatment (100-pretreatment) extractions.

Figure 4.

Standard curve for the three influenza A (IAV) reference strains in different extended semen using the IndiMag Pathogen Kit with 100 µL semen input with the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) and Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (WVDL) IAV assays. Reference 1 was spiked into negative semen with milk-based extender, Reference 2 was spiked into negative semen with egg yolk-based extender, and Reference 3 was spiked into negative sexed-semen with milk-based extender.

Figure 4.

Standard curve for the three influenza A (IAV) reference strains in different extended semen using the IndiMag Pathogen Kit with 100 µL semen input with the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) and Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (WVDL) IAV assays. Reference 1 was spiked into negative semen with milk-based extender, Reference 2 was spiked into negative semen with egg yolk-based extender, and Reference 3 was spiked into negative sexed-semen with milk-based extender.

Figure 5.

Box and whisker plot of the CT values for the spiked influenza A virus (IAV) and the internal controls in semen extracted using the IndiMag Pathogen Kit with 100 µL semen input on the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) and Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (WVDL) IAV assays.

Figure 5.

Box and whisker plot of the CT values for the spiked influenza A virus (IAV) and the internal controls in semen extracted using the IndiMag Pathogen Kit with 100 µL semen input on the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) and Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (WVDL) IAV assays.

Figure 6.

Repeatability for the spiked influenza A virus (IAV) samples using the IndiMag Pathogen Kit with 100 µL semen input on the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) and Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (WVDL) IAV assays. The solid black line near zero represents mean variance.

Figure 6.

Repeatability for the spiked influenza A virus (IAV) samples using the IndiMag Pathogen Kit with 100 µL semen input on the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) and Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (WVDL) IAV assays. The solid black line near zero represents mean variance.

Table 1.

Percentage of samples passing using the MagMAX CORE Kit (CORE) with 200 µL semen input (200-na), 50 µL semen input (50-na), and 12.5 µL semen input with pretreatment (12.5-pretreatment); and the IndiMag Pathogen Kit (Pathogen) with 200 µL semen input (200-na), 100 µL semen input (100-na), and 100 µL semen input with pretreatment (100-pretreatment) using Xeno RNA and Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory internal control (WVDL IC). The categories of semen are egg yolk-based extender (Yellow), milk-based extender sexed-semen (Green or Pink), and milk-based extender (White).

Table 1.

Percentage of samples passing using the MagMAX CORE Kit (CORE) with 200 µL semen input (200-na), 50 µL semen input (50-na), and 12.5 µL semen input with pretreatment (12.5-pretreatment); and the IndiMag Pathogen Kit (Pathogen) with 200 µL semen input (200-na), 100 µL semen input (100-na), and 100 µL semen input with pretreatment (100-pretreatment) using Xeno RNA and Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory internal control (WVDL IC). The categories of semen are egg yolk-based extender (Yellow), milk-based extender sexed-semen (Green or Pink), and milk-based extender (White).

| PCR Methodology |

CORE |

Pathogen |

| Extraction Kit |

Xeno RNA |

WVDL IC |

Xeno RNA |

WVDL IC |

| Semen input & modification |

200-na |

50-na |

12.5-pretreat-ment |

200-na |

50-na |

12.5-pretreat-ment |

200-na |

100-na |

100-pretreat-ment |

200-na |

100-na |

100-pretreat-ment |

| Yellow (n=24) |

25.0 |

62.5 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

83.3 |

100.0 |

41.7 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

95.8 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| Green (n=16) |

12.5 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

50.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| Pink (n=16) |

81.3 |

87.5 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

93.8 |

100.0 |

87.5 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| White (n=32) |

21.9 |

62.5 |

100.0 |

93.8 |

96.9 |

100.0 |

3.1 |

100.0 |

59.4 |

83.3 |

100.0 |

68.8 |

| Overall Passing rate (n=88) |

31.8 |

73.9 |

100.0 |

97.7 |

93.2 |

100.0 |

37.5 |

100.0 |

85.2 |

94.3 |

100.0 |

88.6 |

Table 2.

Percentage of pathogen detection for Mycoplasma bovis (M. bovis), bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), and bovine herpesvirus-1 (BHV-1) positive extended semen samples using the MagMAX CORE KIT (CORE) extraction with the 12.5 µL semen input and pretreatment (12.5-pretrement) and using the IndiMag Pathogen Kit (Pathogen) with 100 µL semen input (100-na) and 100 µL semen input with pretreatment (100-pretreatment) extractions.

Table 2.

Percentage of pathogen detection for Mycoplasma bovis (M. bovis), bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), and bovine herpesvirus-1 (BHV-1) positive extended semen samples using the MagMAX CORE KIT (CORE) extraction with the 12.5 µL semen input and pretreatment (12.5-pretrement) and using the IndiMag Pathogen Kit (Pathogen) with 100 µL semen input (100-na) and 100 µL semen input with pretreatment (100-pretreatment) extractions.

| Extraction Kit |

Core |

Pathogen |

| Semen input & Modification |

12.5-pretreatment |

100-na |

100-pretreatment |

| Extraction Rep |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

|

M. bovis (n=8) |

75.0% |

87.5% |

75.0% |

100.0% |

87.5% |

100.0% |

| BVDV (n=5) |

60.0% |

60.0% |

80.0% |

80.0% |

100.0% |

80.0% |

| BHV-1 (n=23) |

87.0% |

95.7% |

95.7% |

95.7% |

95.7% |

100.0% |

| Sensitivity (n=36) |

80.6% |

88.9% |

88.9% |

94.4% |

94.4% |

97.2% |

Table 3.

The limit of detection (LOD), coefficient of correlation of the standard curve (R2), and percent PCR efficiency for the three reference strains using the IndiMag Pathogen Kit with 100 µL semen input on the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) and Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (WVDL) assays.

Table 3.

The limit of detection (LOD), coefficient of correlation of the standard curve (R2), and percent PCR efficiency for the three reference strains using the IndiMag Pathogen Kit with 100 µL semen input on the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) and Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (WVDL) assays.

| |

Reference

Strain |

NAHLN IAV assay |

WVDL IAV assay |

| |

Replicate 1 |

Replicate

2 |

Replicate 3 |

Replicate 1 |

Replicate

2 |

Replicate 3 |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) |

1 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

| 2 |

7 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

7 |

7 |

| 3 |

7 |

6 |

7 |

6 |

7 |

7 |

| R2 value |

1 |

0.997 |

0.99 |

0.994 |

0.997 |

0.995 |

0.999 |

| 2 |

0.999 |

0.998 |

0.998 |

0.999 |

0.999 |

0.996 |

| 3 |

0.997 |

0.995 |

0.999 |

0.997 |

0.995 |

0.996 |

| PCR Efficiency (%) |

1 |

110.6 |

118.0 |

113.3 |

102.1 |

104.8 |

103.8 |

| 2 |

98.5 |

109.0 |

101.3 |

106.2 |

97.8 |

101.5 |

| 3 |

100.6 |

120.7 |

110.9 |

116.4 |

112.2 |

109.9 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).