1. Introduction

The first confirmed case of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the Philippines was reported on January 30, 2020. Since then, more than four million Filipinos have contracted the virus, according to official records from the Department of Health (DOH). In response to the rapid increase in cases worldwide, the Philippine government adopted a science-based, multi-agency approach to managing the pandemic. Central to this effort was the formation of the Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF) in January 2020, which was tasked with coordinating and leading the national respons One of the key elements of the IATF’s strategy was the implementation of a data-driven decision-making framework, based on specific epidemiological thresholds and operational standards. To ensure scientific accuracy and technical validity, experts from academic and research institutions were involved. Additionally, information technology solutions were prioritized to align data management practices with global standards.

On March 15, 2020, the Government announced the implementation of the strictest mobility restriction at that time—Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ)—across mainland Luzon, including the National Capital Region (NCR). The ECQ, formally enforced from March 17 to April 13, 2020, aimed to reduce viral transmission and give the Government critical lead time to establish structural measures for long-term containment. The ECQ period was extended until May 2020, with subsequent region-specific and localized quarantines continuing intermittently until 2022.

Throughout this period, the DOH issued daily public bulletins on confirmed cases, deaths, and recoveries. This transparency allowed both the government and citizens to track the pandemic’s course and better understand policy decisions. For example, on March 17, 2020, the DOH reported 178 confirmed cases—a number that seemed relatively low compared to thousands of new cases daily in European countries like Italy and Spain. Nonetheless, the Philippine Government kept strict restrictions, emphasizing a precautionary approach to prevent rapid spread.

During the initial two months of the pandemic, the IATF established governance mechanisms to ensure a comprehensive response. One of these was the Sub-Technical Working Group on Information and Communications Technology (STWG-ICT), responsible for ensuring the availability, integration, and coordination of digital systems to support pandemic management. Recognizing the importance of accurate and timely data in controlling an “invisible enemy,” the IATF mandated the creation of multiple technical workstreams, including Workstream 4 (WS4) on End-to-End Data Integration. WS4 specifically focused on enabling interoperability among the various COVID-19 data systems used across the country.

This paper shares the experiences and lessons learned from WS4 during its efforts to enable interoperability in the first year of the pandemic (March 2020–March 2021). It covers the governance, architectural, and technical measures taken to integrate various systems, along with the role of interoperability laboratories, such as the Standards and Interoperability Lab-Asia (SIL-Asia), in maintaining an ecosystem of more than a dozen applications. By presenting these findings, this study aims to add to the growing body of literature on pandemic information systems and provide practical insights for future implementation of interoperability frameworks in emergency response settings.

2. An Interoperability Problem

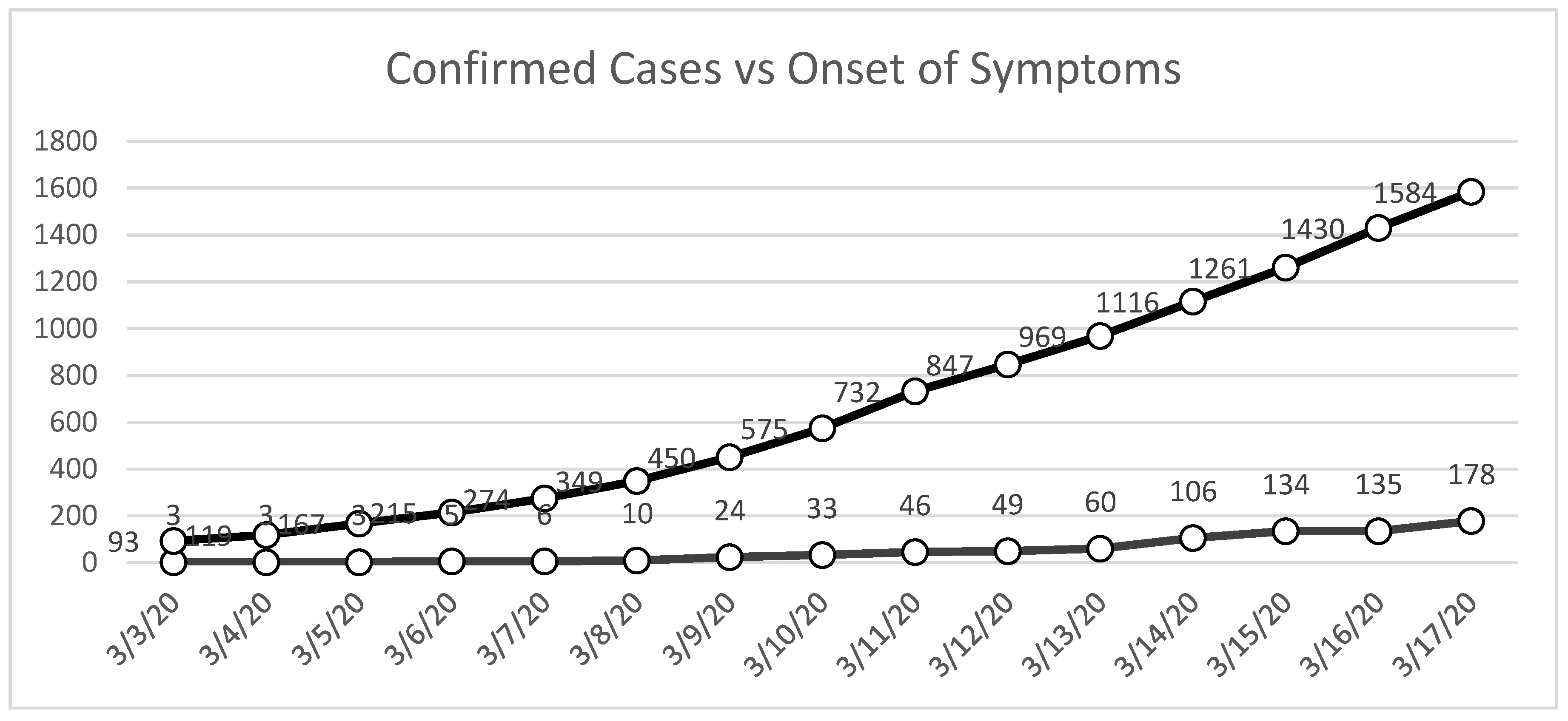

As noted earlier in this paper, official reports from the DOH (DOH Data Drop) indicated that as of March 17, 2020, the Philippines had confirmed 178 cases of COVID-19. However, subsequent reviews of the DOH’s publicly released data dumps, which were made available several months later, revealed a significant discrepancy: by the same date, there were already more than 1,584 cases in the country (

Figure 1). This nearly eightfold difference between contemporaneous official bulletins and retrospective datasets highlights a critical challenge in the early stages of pandemic management—namely, the reliability and timeliness of reported data.

Policy decisions, especially those concerning quarantine enforcement, mobility restrictions, and the distribution of vital resources, were based on the assumption that official case counts accurately reflected the epidemiological situation. The existence of such discrepancies suggests that decision-makers may have been operating with incomplete or outdated information, which in turn affects the timing, scope, and scale of government actions.

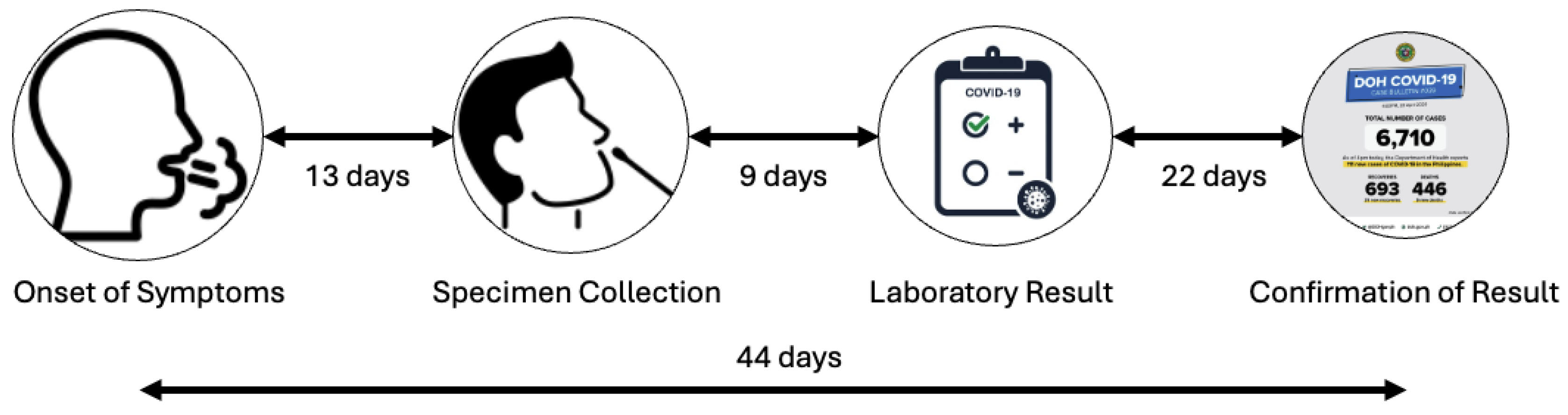

An analysis of available datasets reveals that a significant factor behind this reporting discrepancy was the delay in case confirmation. Review of DOH records from the first four months of the pandemic shows that the average time from symptom onset to official COVID-19 case confirmation was about 44 days. This delay can be broken down into several phases (

Figure 2).

Symptom onset to specimen collection: On average, 13 days passed between the start of symptoms and the collection of a COVID-19 specimen. This delay was partly due to limited awareness of testing protocols among patients and healthcare providers, as well as logistical barriers to reaching accredited testing centers.

Specimen collection to release of results: The time between specimen collection, laboratory testing, and results release was about 9 days. This delay mainly resulted from the significant shortage of accredited COVID-19 testing labs during the early months of the pandemic, when testing capacity was focused primarily on the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM) and a few regional hubs.

Result release to official case confirmation: The most significant bottleneck was likely the time between laboratory confirmation and official DOH case reporting, which averaged 22 days. This delay was not due to a lack of information systems but rather the need to validate patient records, reconcile laboratory results with case investigation forms, and start contact tracing. These tasks caused considerable administrative work, leading to further delays.

Together, these factors contributed to a reporting lag of over six weeks, obscuring the accurate scale of transmission at critical junctures.

The COVID-19 Data Ecosystem

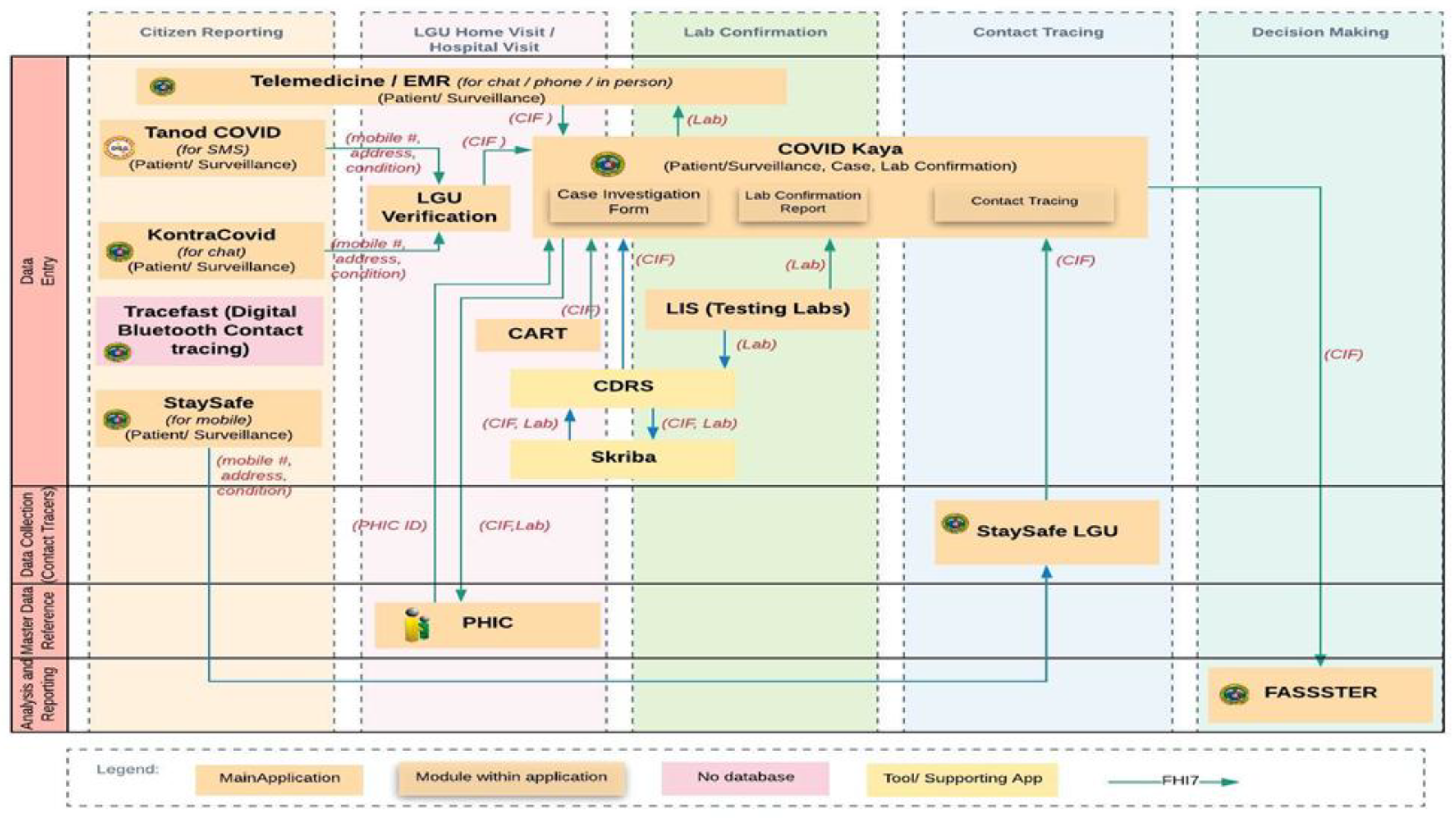

By May 2020, the country already had a suite of ICT solutions that could be used to collect COVID-19-related data (Uy, 2025). This implies that the problems related to data collection during the COVID-19 period are no longer issues of data collection, storage, or analysis. The Philippine COVID-19 response involved a proliferation of digital applications designed to capture, store, and process information at various points in the data lifecycle (Uy, 2025) Aside from the nationally developed systems, LGUs have also created their own information systems for COVID-19 data management.

Figure 3 illustrates the COVID-19 data ecosystem, which includes more than a dozen distinct applications, each with specific roles in validation and reporting processes.

Table 1.

COVID-19 ICT Ecosystem.

Table 1.

COVID-19 ICT Ecosystem.

| System |

Role |

Description |

| COVID Kaya |

Case reporting |

Primary DOH platform for case investigation and reporting |

| EMR |

Facility-level record |

Electronic Medical Records used by hospitals and clinics |

| Tanod COVID |

Community-level monitoring |

Barangay-level surveillance tool for suspected cases |

| Kontra COVID |

Public engagement |

Citizen reporting and information platform |

| StaySafe |

Contact tracing |

Mobile application for exposure notification and symptom reporting |

| CART |

Case assessment |

DOH tool for rapid lab result generation |

| CDRS |

Central data repository |

Unified reporting platform for laboratory results |

| Skriba |

Data entry support |

Facilitates digitization of paper-based records |

| PHIC |

Insurance-linked data |

PhilHealth database for claims and patient records |

| LIS |

Laboratory Information System |

Manages specimen tracking and laboratory workflows |

| FASSSTER |

Modeling and analytics |

Forecasting tool for case trajectories and projections |

| StaySafe LGU |

Localized variant of StaySafe |

Customized deployments for local governments |

While these systems enabled the collection of large volumes of data at the national, regional, and local levels, the main challenge was ensuring they worked together in a coordinated and integrated way. Redundancies, broken data silos, and the lack of a single source of truth hampered the Government’s ability to consolidate information in real time. This fragmentation wasn’t due to the absence of digital infrastructure but rather a lack of software interoperability across applications.

The presence of multiple overlapping systems underscores the need for strong interoperability frameworks in pandemic data management. While individual platforms could collect and process data effectively within their specific scopes, the lack of standardized protocols for data sharing and integration hindered the quick reconciliation of case information. Therefore, the main challenge was not just collecting data, but also harmonizing different systems into a unified ecosystem capable of delivering accurate, real-time insights for decision-makers.

Beyond technical barriers, the COVID-19 pandemic added layers of complexity to achieving interoperability across different information systems. The most significant of these were governance issues. Many of the digital systems used during the early response phase were developed in an ad hoc manner, often as single-purpose projects focused only on COVID-19. Several platforms were provided as in-kind donations from international development partners—such as COVID Kaya, supplied by the World Health Organization (WHO) to the Department of Health (DOH)—while others were created and donated by private sector organizations, including Tanod COVID, Kontra COVID, StaySafe, CDRS, CART, and various Laboratory Information Systems (LIS).

Despite the proliferation of these tools, there was no precise governance mechanism to manage interoperability and integrated data sharing. Although an enterprise architecture was established immediately (Uy, 2025) and identified integration points, a project group is needed to oversee end-to-end integration. This lack of a unified governance framework meant that systems operated primarily in silos, with overlapping functionalities and fragmented datasets. Moreover, unlike in the domain of routine health information systems, there were no pre-existing best practices or reference models available to guide the integration of multiple platforms within the context of a rapidly evolving pandemic.

This unprecedented situation marked the first time the Philippines faced the challenge of managing a national-scale, mission-critical health information technology (IT) system under emergency conditions. The experience emphasizes the importance of establishing governance structures, standards, and integration protocols from the start of digital health initiatives, especially during large-scale public health emergencies.

This experience highlights the importance of interoperability not just as a technical need, but also as a governance and policy priority. In situations like pandemics, where the speed and accuracy of data directly impact public health outcomes, delays of several weeks can significantly affect both the course of disease spread and the effectiveness of government actions.

3. Interventions

As part of the governance structure of the IATF STWG ICT, the workstream on End-to-End Integration (WS4) was established to address the critical need for interoperability across the diverse information systems within the COVID-19 ICT ecosystem(Uy, 2025)by June 2020. WS4 was designed as the primary mechanism for consolidating, aligning, and integrating the multiple platforms that emerged during the pandemic response, ensuring a smooth flow of data across national and local levels.

The capacity of WS4 was significantly enhanced through the technical expertise of the Standards and Interoperability Lab–Asia (SIL-Asia). SIL-Asia is an interoperability laboratory established by the Asia e-Health Information Network (AeHIN) and mainly supported by the Asian Development Bank (ADB). It has become a shared knowledge and capability hub to strengthen digital health interoperability across the Asia-Pacific region(Zuniga, 2020) Before the COVID-19 pandemic, SIL-Asia supported more than ten countries in the area by providing technical guidance and capacity-building on health data standards, including HL7 FHIR(About SIL-Asia, 2021) Its location as a Manila-based regional hub, combined with its accumulated expertise, made its involvement in WS4 both strategic and essential.

Utilizing SIL-Asia’s knowledge base, WS4 accelerated the adoption of interoperability-related initiatives. The endorsement of HL7 FHIR by the IATF as the primary standard for data exchange provided a unifying framework, enabling different systems to work together within a common architecture and standard. The following are some of the interventions undertaken by WS4:

1. Peer-to-Peer Technical Engagements

Given the diversity of developers involved in building and maintaining COVID-19 information systems, along with restrictions on in-person meetings due to the pandemic, WS4 adopted a peer-to-peer approach for its technical coordination. Instead of holding large, general meetings that risked diluting focus, sessions were designed to be targeted and issue-specific. Developers were only invited to discussions directly related to their platforms or data pipelines, which helped make the best use of limited developer time and ensured meetings produced actionable results. This peer-to-peer format also encouraged a more collaborative environment, allowing technical teams to exchange expertise directly and practically.

2. Development of a Philippine COVID-19 HL7 FHIR Implementation Guide

To promote the adoption of HL7 Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR)(HL7 FHIR, n.d.)across different information systems, WS4 led the development of a localized Philippine COVID-19 HL7 FHIR Implementation Guide. Before the pandemic, HL7 FHIR adoption in the Philippines was limited, with most systems using non-standardized or proprietary formats. The IATF’s official designation of HL7 FHIR as the national standard for health data exchange made it necessary to create a customized guide that addressed the local context.

HL7 FHIR includes over 160 resources, which created a steep learning curve and significant implementation challenges under tight deadlines. The Philippine Implementation Guide(Philippine COVID 19 Implementation Guide, 2020)simplified this complexity by focusing on five essential resources, each aligned with the DOH Minimum Data Set(2020 Revised IRR for RA 11332, 2020) Only the necessary data fields within these resources were kept, making implementation easier and reducing the technical burden on developers. The Implementation Guide thus served as a practical tool to standardize system interfaces, allowing developers to focus only on what was essential for COVID-19 response.

3. Deployment of Interoperability Tools

To provide developers with practical tools for testing and integration, WS4 facilitated the deployment of several enabling technologies. An open-source HAPI FHIR sandbox server was established, allowing developers to verify whether their systems could interact with a production-level HL7 FHIR server. This was especially important since systems such as the FASSSTER data warehouse were already set up to use HL7 FHIR-based APIs.

Another key innovation was the creation of a CSV-to-JSON FHIR Converter tool. While some facilities use HL7 FHIR–compliant electronic medical record (EMR) systems that can send data directly to COVID Kaya through its FHIR pipeline, many others depend on spreadsheets as their main data source. To address this, the converter transformed spreadsheet data (in CSV format) into HL7 FHIR–compliant JSON files, which could then be uploaded to COVID Kaya. This solution allowed health facilities and LGUs to keep their current workflows while ensuring their data could still be integrated into national systems without losing fidelity or breaking interoperability standards.

4. Capacity-Building and Knowledge Transfer

Recognizing that technical standards alone would be insufficient without the corresponding human capacity, WS4 and SIL-Asia initiated a series of capacity-building activities across organizations. These sessions ranged from comprehensive trainings on HL7 FHIR for system developers who were unfamiliar with the standard, to brief, targeted consultations addressing specific implementation challenges. The peer-to-peer approach was extended to these capacity-building efforts, allowing for personalized support that matched the readiness levels of each development team.

Where necessary, WS4 via SIL-Asia also utilized international expertise to incorporate perspectives and lessons learned from other jurisdictions, ensuring that local implementations aligned with global best practices. This combination of localized guidance and international benchmarking bolstered the technical community’s confidence and skills in adopting HL7 FHIR, supporting the sustainability of interoperability initiatives beyond the immediate pandemic response.

5. Overall Project Management

Before the creation of individual workstreams, the management of COVID-19 information systems was mostly centralized, with little focus on interoperability issues. This centralized method tended to focus on system-level functions and immediate operational needs, often neglecting or only partially addressing interoperability problems.

The creation of specialized workstreams, especially WS4 focused on end-to-end data integration, introduced a more structured governance system dedicated to interoperability. WS4 served as the main group responsible for handling both technical and non-technical interoperability issues. This governance structure ensured that integration-related problems were consistently identified, discussed, and resolved. It also made interoperability a fundamental part of project management, rather than an afterthought.

4. Monitoring Progress in Interoperability

Monitoring progress in system integration is one of the biggest challenges in large-scale interoperability efforts. During the COVID-19 response, the urgency of linking different information systems increased the need for clear and accountable monitoring methods. For WS4, this meant monitoring could not just observe final results (i.e., whether systems were connected), but also had to track the small steps that, together, made interoperability possible. To work well, progress monitoring needed to assign task ownership and include measurable metrics, making sure accountability was part of the process.

The work of Kasunic and Anderson on Measuring Systems Interoperability was reviewed to find a good way to track progress in interoperability. In their work(Kasunic, 2001) the authors describe interoperability as having multiple parts, including technical, operational, organizational, and cultural areas. They highlight that measuring interoperability clearly and systematically is very important, especially in situations where quick decisions are needed and there is uncertainty. The Levels of Information Systems Interoperability (LISI) model offers a method that uses a maturity framework to evaluate how systems move from being separate to fully integrated at the enterprise level. Although it is detailed, LISI also stresses the need to define small, measurable steps that can be tracked in procedures, applications, infrastructure, and data.

Building on these insights, WS4 adopted a hybrid monitoring approach that combined a scorecard model with LISI-style principles. The scorecard presented results in a simple and easy-to-understand format, while the LISI framework offered a thorough way to assess progress. This combination allowed for measuring incremental successes rather than just a yes-or-no decision on whether systems were connected. As a result, progress was visible even before full integration, which was especially important in a crisis-driven environment where timely insights matter.

A key design principle of this hybrid framework was that monitoring checkpoints needed to match existing developer workflows to reduce disruption. Each checkpoint was described in simple, verifiable terms, enabling transparent assessment. The following checkpoints were established:

- 1.

API Documentation Provided.

This initial checkpoint was essential because it established transparency regarding how systems revealed their services and data. API documentation offered developers a clear guide on data access, interaction methods, and limitations. For systems already using HL7 FHIR, the Implementation Guide served as the official API documentation. This step formed the foundation for all future integration efforts, as interoperability depends on a common understanding of how systems communicate.

- 2.

Mapping of Data Dictionary.

The second checkpoint focused on semantic alignment, making sure data elements like patient identifiers, laboratory results, and case classifications were consistently defined across systems. This mapping step was essential for maintaining data accuracy and comparability, which allowed for meaningful exchange rather than just technical connectivity.

- 3.

ETL Template Provided.

To operationalize data flows, WS4 needed Extract, Transform, Load (ETL) templates. These acted as blueprints for extracting data from source systems, converting it into the agreed-upon format, and loading it into the target system. This step was especially important for spreadsheet-based systems at the local government level, where standardized pipelines lowered the risk of transformation errors.

- 4.

System Modification.

Achieving interoperability often requires modifications to existing applications. These include adding new fields, refining workflows to capture minimum datasets, or producing HL7 FHIR–compliant outputs. By explicitly monitoring system modifications, WS4 ensured that technical readiness was achieved and documented, bridging the gap between planning and implementation.

- 5.

Integration Testing.

Integration testing was the validation phase where systems were connected and tested for actual data exchange. This checkpoint enabled the identification of errors, bottlenecks, or unexpected incompatibilities in a controlled environment. Detecting issues early allowed for quick iteration and reduced risks during live deployment, strengthening the reliability of the interoperability framework.

- 6.

Technical Integration Achieved.

The final checkpoint indicated that two or more systems had successfully exchanged data according to agreed standards. This step provided clear evidence of interoperability, showing that the systems had moved beyond standalone operation and were functioning as part of an integrated ecosystem.

Taken together, these checkpoints formed a progressive path toward interoperability. Instead of viewing interoperability as a single milestone, the hybrid framework redefined it as a series of verifiable achievements. The scorecard format provided quick visibility of progress for stakeholders, while the LISI-based structure added rigor and accountability. This dual approach not only promoted transparency but also improved coordination among diverse stakeholders, helping the Philippines’ COVID-19 ICT ecosystem move toward greater interoperability.

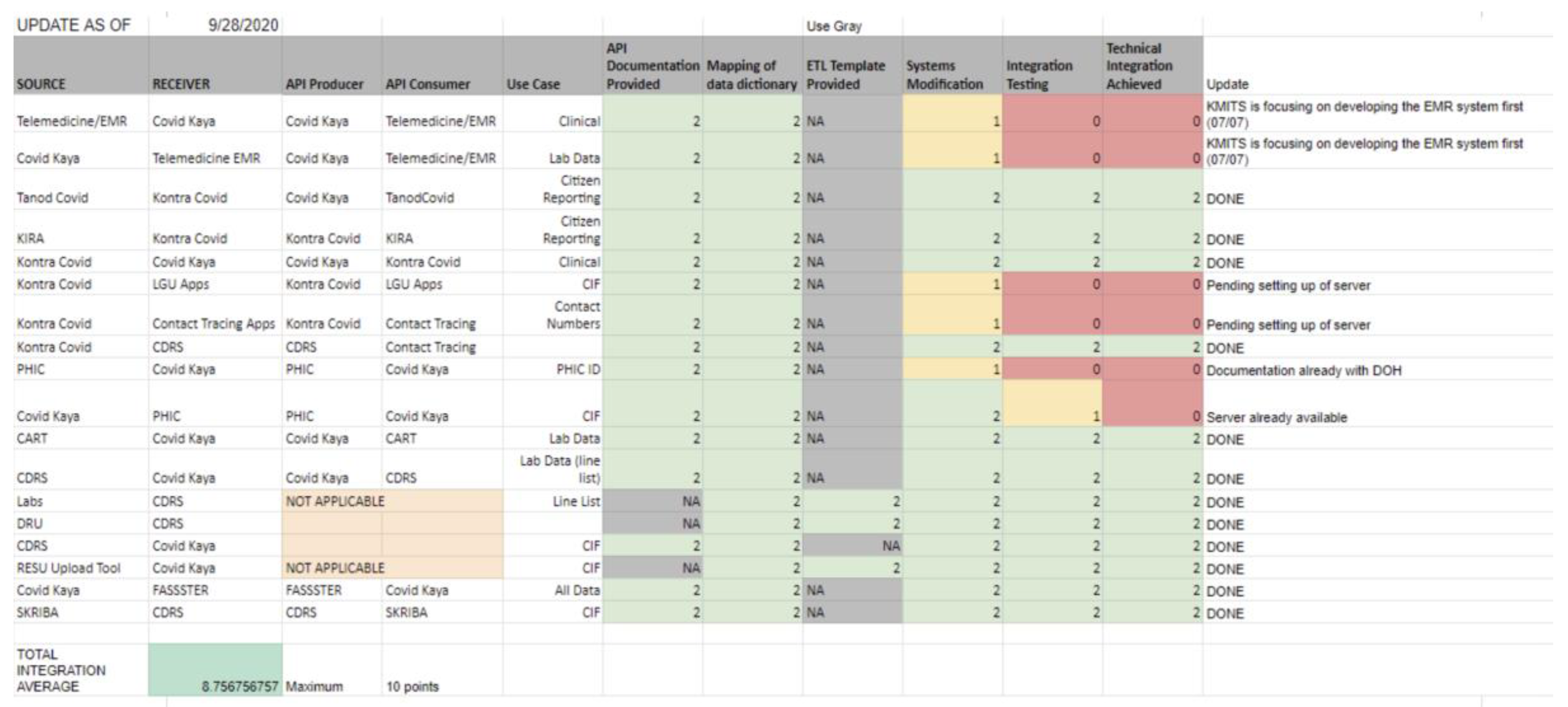

To measure the progress of the interoperability workstream, an integrated scorecard was created. For each pair of applications, a data source and data receiver were identified. When two-way interoperability is required, the application pair should also be monitored with reversed roles.

For each system pair, interoperability progress was evaluated using a step-by-step scoring system aligned with specific checkpoints. Each checkpoint was given a value based on its completion status: a score of 2 for fully completed steps, 1 for steps in progress, and 0 for steps not started. This ordinal scoring method allowed for measuring incremental progress rather than just binary interoperability measures.

Figure 4 displays a sample snapshot of the scorecard.

The total score for each system pair was calculated by adding the points from all checkpoints, creating a standard measure of progress. To enable comparison across pairs and support ecosystem-level monitoring, the scores were averaged across all participating pairs and then scaled to a 0–10 range. This normalization offered an easy-to-understand metric that indicated the overall interoperability status within the ecosystem while maintaining sensitivity to small improvements.

Using this scoring method, progress can be tracked both at the micro-level (system pair interactions) and the macro-level (overall ecosystem performance). The approach provides a balanced view: detailed insights into where integration bottlenecks happen, and overall indicators to guide governance and policy decisions.

5. Results and Discussion

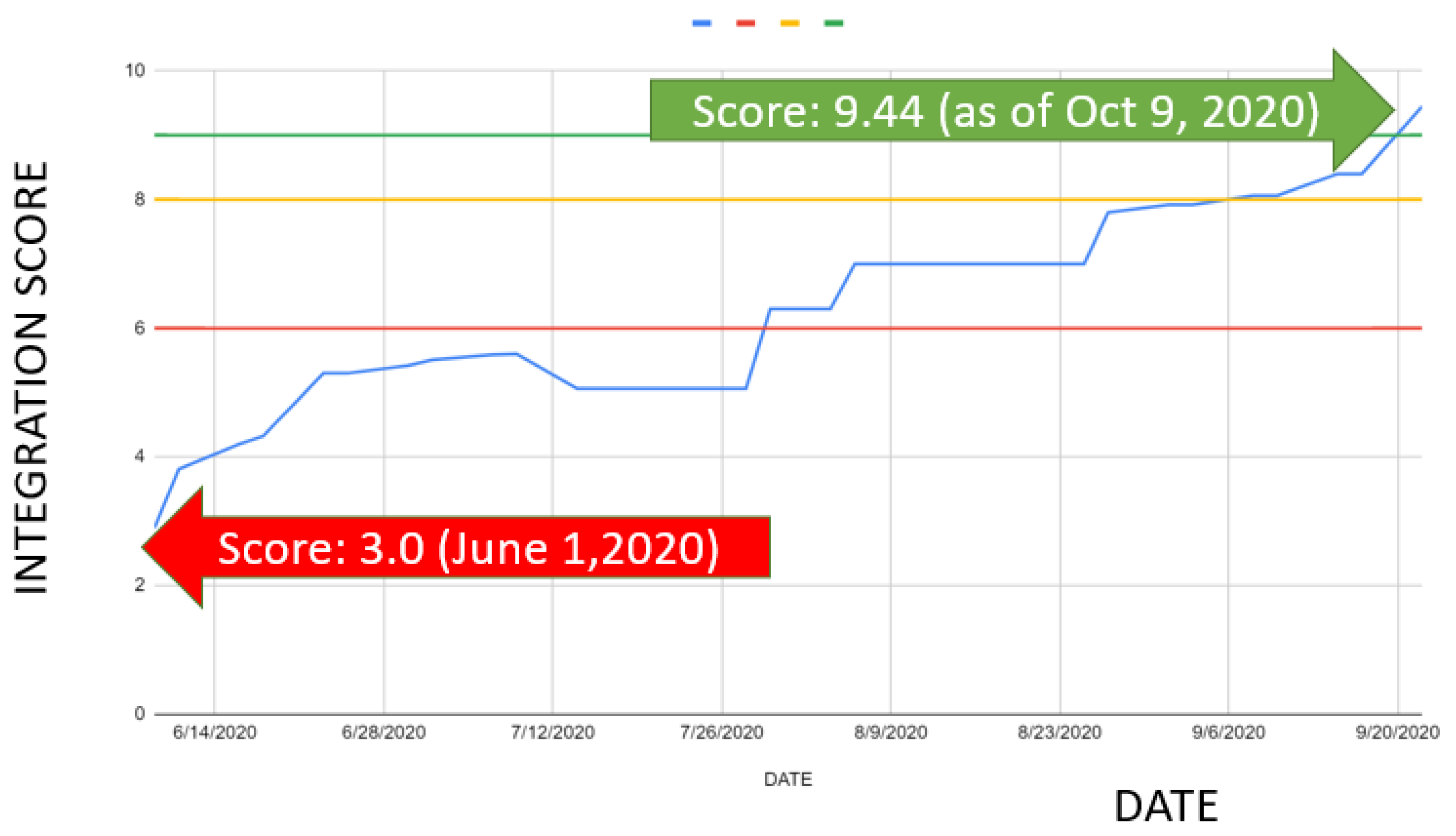

When the interoperability monitoring framework was first put into place in June 2020, the average interoperability score across the ecosystem was 3.0 (

Figure 5). This initial score showed that most information systems had not yet taken significant steps toward data integration, and only a few system pairs had achieved early-stage interoperability. In other words, although technical basics like API documentation or data dictionary mapping were starting to emerge, the overall ecosystem remained scattered, with limited ability for cross-system data exchange.

Following the implementation of the interoperability interventions discussed in the previous section—including peer-to-peer developer engagements, the development of a localized HL7 FHIR Implementation Guide, the deployment of interoperability tools, and targeted capacity building—a significant improvement was observed. Progress was tracked alongside these efforts, and by October 2020, the interoperability score had reached 9.0. At this point, almost all participating systems in the COVID-19 ICT ecosystem were functionally integrated, enabling near real-time data sharing across platforms. The rapid rise in scores over a four-month span demonstrated the effectiveness of adopting a structured, step-by-step monitoring approach combined with targeted technical and organizational support.

The following question was to evaluate the practical impact of this interoperability on pandemic response. In earlier sections, we hypothesized that the lack of interoperability contributed to delays in confirming cases, especially in bridging the gap between symptom onset and official COVID-19 case reporting. To test this hypothesis, Department of Health (DOH) datasets were re-examined to compare timelines before and after the interoperability efforts.

The results, summarized in

Table 2, show a significant decrease in the time between symptom onset and case confirmation. In March 2020, the average delay was 44 days, but by October 2020, it was reduced to 6 days, an almost 80% improvement. The most notable reduction occurred in the sub-interval between the release of laboratory results and official case confirmation: from 22 days in June to 3 days in October, a reduction of about 87%. These results indicate that interoperability improvements not only boosted data exchange efficiency but also had a clear impact on speeding up case reporting times.

It is important, however, to situate these results within the broader pandemic response context. While the reduction in reporting delays can be considered a strong indicator of the positive effects of interoperability, other contributing factors must be acknowledged. Non-technical improvements—such as the expansion of laboratory capacity, process streamlining, increased familiarity of health personnel with reporting workflows, and improved governance mechanisms—likely complemented the technical interventions. Thus, while interoperability played a critical enabling role, the observed improvements are best understood as the result of a combination of technological, organizational, and experiential learning effects.

6. Lessons and Recommendations

The implementation of interoperability efforts during the Philippines’ COVID-19 response provided several important insights that go beyond the immediate context of the pandemic. While the main goal of WS4 was to facilitate the seamless exchange of health data across different systems, designing, coordinating, and implementing these efforts revealed deeper lessons about governance, technical standards, capacity building, and equity. These lessons highlight that interoperability is not just a technical achievement but a continuous, multi-faceted process that relies on clear governance structures, practical adoption strategies, effective monitoring, and inclusive approaches that consider various resource environments. Additionally, the experience showed the strategic importance of dedicated interoperability laboratories as hubs of innovation, technical validation, and institutional knowledge. Overall, these lessons lay the groundwork for strengthening digital health systems and provide practical guidance for future public health emergencies.

- 1.

Interoperability as Both a Governance and Technical Challenge

Interoperability cannot be viewed only as a technical issue. The Philippine experience shows that dedicated governance structures—such as Workstream 4 (WS4)—are vital for effective coordination. With clear mandates, decision rights, and escalation mechanisms, WS4 sped up resolving cross-system problems and kept integration a priority in the broader pandemic response. This demonstrates that governance mechanisms are just as important as technical standards in maintaining large-scale interoperability.

- 2.

Adopt a “Minimum, Then Mature” Strategy

The rapid development of a locally tailored HL7 FHIR Implementation Guide (IG), along with the DOH Minimum Data Set, significantly lowered the barriers to system adoption. By focusing on a narrowly scoped set of core data elements, the approach created a shared vocabulary that enabled immediate exchange while keeping implementation demands manageable under emergency conditions. This incremental strategy highlights the importance of establishing minimal interoperability first, with deeper semantic and functional integration to follow as systems stabilize and mature.

- 3.

The Value of Scorecards in Monitoring Progress

Using a simple, ordinal scoring model—mapped against clear checkpoints—proved very effective in making interoperability progress visible and easy to manage. This method let stakeholders see incremental improvements even before systems fully integrated into production. By making progress measurable and transparent, the scorecard approach supported timely governance decisions, helped prioritize resources, and encouraged accountability across involved organizations.

- 4.

Designing for Heterogeneity and Low-Resource Settings

A key lesson from the COVID-19 response is that interoperability solutions must support diverse systems and resource environments. Connecting spreadsheets and paper-based workflows with HL7 FHIR pipelines allowed facilities without electronic medical records (EMRs), including those in geographically isolated and disadvantaged areas (GIDAs), to still submit timely data. This approach strengthened the principle of equity in national surveillance and highlighted the need for interoperability frameworks that include varying levels of technological readiness.

- 5.

The Strategic Role of Interoperability Laboratories

One of the most important lessons from the Philippine COVID-19 response was the value of dedicated interoperability laboratories as technical and knowledge hubs. The Standards and Interoperability Lab–Asia (SIL-Asia) played a crucial role in helping WS4 turn global standards into local practice. As a regional facility with experience supporting more than ten Asia-Pacific countries, SIL-Asia provided technical expertise, implementation guidance, and practical tools such as FHIR sandboxes and validators. These resources let developers test integrations in controlled environments, reducing risks before live deployment. Additionally, interoperability labs act as centers for capacity building by offering training, peer-to-peer consultations, and reference implementations that speed up adoption. Having a permanent lab also preserves institutional knowledge, ensuring continuity beyond the immediate crisis and creating a repository of artifacts, templates, and playbooks for future use. The Philippine experience shows that integrating interoperability labs into national and regional health information systems strengthens both preparedness and resilience for future pandemics and health emergencies.

The country’s response to COVID-19 emphasized the vital role of ICT in lessening the effects of a public health crisis. ICT efforts, especially those enabling quick data sharing, decision-making, and coordinated service delivery, helped improve pandemic management’s speed and effectiveness. A key part of this experience was the development and use of interoperability and systems integration techniques, which tackled long-standing issues of fragmented health information systems. These lessons go beyond the immediate pandemic situation; they lay a foundation for ongoing health sector reforms, particularly as the country moves toward full implementation of Universal Health Coverage (UHC). In this paper, we highlight the specific contributions of WS4 in promoting interoperability, placing these initiatives within the larger reform agenda. By reflecting on these experiences, we advocate for establishing effective practices to ensure continuity, scalability, and sustainability—reducing the risk of duplicated or temporary responses in future health crises and system reforms.

Acknowledgements

This work would not have been possible without the support of the Asian Development Bank. Equally important was the guidance of Dr. Eric Paringgit from the Philippine Council for Industry, Energy, and Emerging Technology Research and Development (PCIEERD), whose leadership kept the interoperability agenda focused on its main goal of saving lives. The efforts of Workstream 4 (WS4) were also greatly enhanced by the collaboration and support of fellow workstream leaders, including Francis Uy, Pablo Yambot, Emily Razal, Sua Casanova, Dr. Reena Estuar, Lorraine Goyena, and Tom Corleto, whose combined contributions added technical depth and strategic focus.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors acknowledge their roles in the project described in this paper. Philip Zuniga was the Project Manager for WS4, while Raymond Sarmiento served as the overall Project Lead for the sTWG on ICT.

References

- Vallejo, B. Policy responses and government science advice for the COVID 19 pandemic in the Philippines: January to April 2020; Progress in Disaster Science, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Uy, F. From Blueprint to Breakthrough: Digital Transformation in the Philippines’ Pandemic Response Rapid Enterprise Architecture Deployment in National Crisis Management; The Open Group, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga, P. C. Establishing a Regional Digital Health Interoperability Lab in the Asia-Pacific Region: Experiences and Recommendations. In Leveraging Data Science for Global Health; Springer, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- About SIL-Asia. Retrieved from SIL-Asia website. 2021. Available online: www.sil-asia.org.

- HL7 FHIR. Retrieved from HL7 FHIR website. n.d. Available online: https://www.hl7.org/fhir/.

- Philippine COVID 19 Implementation Guide. Retrieved from Philippine COVID 19 Implementation Guide. 2020. Available online: https://pczuniga.notion.site/Philippine-COVID-19-Implementation-Guide-b62d46afbfb14ee797e6cf9f14b05e1d.

- 2020 Revised IRR for RA 11332. The 2020 Implementing Rules and Regulations for RA 11332; Philippine Government, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kasunic, M. Measuring Systems Interoperability, Challenges and Opportunities. 2001, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).