1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognized the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that spread in countries and territories as a global pandemic on March 11, 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020). As early as May 2020, over 5 million people had been infected with the virus across 213 countries and territories, which led to more than 300,000 deaths (WHO, 2020). During these times, both the national and local governments in many countries have been at the forefront of the COVID-19 pandemic response (Zhou & Xin, 2021) and continuously implemented, reformed, and adapted public health interventions (PHI) based on the WHO guidelines and recommendations to curb the widespread transmission of COVID-19 among its constituents (Talabis et al., 2021).

The Philippines is one of the hard-hit countries because of this global pandemic. COVID-19 cases maintained a steady rise during the first months of the pandemic, which prompted the Philippine government to close international and local borders and implement stringent screening measures. Almost 80% of new cases from contact tracing were quarantined within 48 hours of detection (Paddock & Sijabat, 2020). In addition, based on numerous research studies that implemented optimal control theory, the DOH set the minimum public health standards as a guide for implementing non-pharmaceutical interventions in the COVID-19 response (Lemecha Obsu & Feyissa Balcha, 2020; Madubueze et al., 2020; Perkins & España, 2020; Sasmita et al., 2020; Tsay et al., 2020). The ramping up of different combinations of rapid testing, contact tracing, and awareness campaigns and the minimum public health standards, such as physical distancing, cough etiquette and respiratory hygiene, personal and environmental hygiene, symptom monitoring, and promotion of mental health were prioritized by the national government (Freeman & Eykelbosh, 2020).

Highly Urbanized Cities (HUCs) naturally became the hotspots for COVID-19 because of denser populations, more economic activities, and greater mobility of people (Sharifi & Khavarian-Garmsir, 2020). While the national government implemented policies to support the Philippine National Action Plan for the COVID-19 pandemic, the local government units (LGUs), especially in the urban cities, bore the strict implementation of PHI. As such, LGUs all over the Philippines continually assessed the effectiveness of existing PHIs and strengthened these control measures to suit the prevailing local contexts (Talabis et al., 2021), as poor PHIs translate to substantial public health consequences (Ornell et al., 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic is multifaceted; hence, there are innumerable effects on society. Therefore, governments all over the world must make use of data coming from all fronts. With this, the WHO enjoined governments to facilitate open data sharing to support policies related to the COVID-19 response (Park et al., 2022). According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Open-Source Government Data or OSGD is a “non-discriminatory data access and sharing arrangements where data can be accessed and shared free of charge and used by anyone for any purpose subject to requirements that preserve integrity, provenance, attribution, and openness” (González-Zapata et al., 2021). The use and reuse of COVID-19-related OSGD facilitate informed decision-makers to provide appropriate and timely interventions, mitigate the consequences (health, social, and economic) of COVID-19, rebuild and transition to the new normal, and prepare for future pandemics. Moreover, it encourages citizen engagement, fuels innovation in the private sector and the academe, and increases government accountability and transparency (OECD, 2018).

Data sharing and open knowledge are essential in guiding decision-makers in mitigating the COVID-19 crisis. Several data hubs for COVID-19 policies and non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) collected country-level metadata from publicly available online resources (Desvars-Larrive et al., 2020) that reused OGSD, including CoronaNet Research Project (

https://www.coronanet-project.org), the COVID Analysis and Mapping of Policies (

https://covidamp.org), and the Complexity Science Hub COVID-19 Strategies List (CCCSL) (

https://covid19-interventions.com/). Various approaches relating to public health interventions (PHI) data collection were identified (Hartley & Perencevich, 2020). Some of these approaches were particular to specific public health interventions, such as discontinuing face-to-face school learning (Brauner et al., 2021), mobility and travel restrictions (Lai et al., 2020), and initiatives to guarantee the uninterrupted supply of personal protective equipment and critical medical products (Park et al., 2020). In contrast, others deal with a more extensive scope of PHIs. These data hubs and their visualizations may give insights into the effect of public health interventions implemented in a country. In the Philippines, OSGD related to COVID-19 surveillance and interventions were made publicly available by national and local government units and health agencies primarily for information purposes. In this study, we highlight the importance of documenting city-level interventions against COVID-19, and incorporating local metadata in PHI assessments since these may provide unique insights into epidemic response and epidemic preparedness in HUCs.

Open data must be publicly available and accessible, in an open or machine-readable format, with an open license, and be timely and updated regularly (Wang & Shepherd, 2020). Steps to make government data “open” in the Philippines have been taken as early as 2013 with the launch of Open Data Philippines (ODPH) (

https://data.gov.ph/). ODPH is the repository of open government data from different government agencies (GovPH, 2023). Other government data can also be accessed through the electronic Freedom of Information (eFOI) Program created in 2016 to increase government transparency. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Philippine Department of Health regularly released national and local COVID-19 surveillance data. PHIs were reported as part of regular bulletins of the national Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF-EID). However, reports on PHIs are commonly aggregated in the national and regional level.

How did HUCs in the Philippines respond to the COVID-19 pandemic? This study aimed to consolidate COVID-19 public health surveillance and interventions in selected HUCs in the Philippines using OSGD. The results of this study can be used for post-pandemic assessments and improvement of local and national epidemic preparedness and response programs against future emerging or re-emerging infections in the Philippines. This approach can also be applied to other emerging or re-emerging public health events in countries or cities with constrained or developing public health surveillance infrastructure.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This study is a descriptive documentation of the COVID-19 public health interventions in the Philippines from February 2020 to January 2023, based on OSGD data. HUCs are designated land areas certified by the Philippine Statistics Authority in the Philippines with a minimum population of 200,000 inhabitants. These HUCs have an annual income of at least P50,000,000.00 (US$ 1 = 57 Philippine Pesos) based on 1991 constant prices, according to Section 452 of Republic Act 7160 or the Act providing for a local government code (Rivera, 2010). HUCs for the three major islands were selected based on their population number; Quezon City and the City of Manila for Luzon, Cebu City for the Visayas Region, and Davao City for Mindanao. OSGD information on COVID-19 statistics, control strategies, and vaccination coverage for each city were searched and collected.

The study protocol was approved by the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB 2021-0314-01).

Open Data Sources

We obtained metadata for this study from an internet source, Google/Google Trend Index, and used these data to facilitate subsequent analysis. In the Google search engine, the following general keywords were used to retrieve metadata:

“COVID-19 Philippines”, “DOH COVID-19 tracker”, “DOH COVID-19 vaccination”, “COVID-19 protocol Philippines”, “COVID-19 protocol+[HUC]”, “COVID-19 vaccine coverage+[HUC]”, “COVID-19 vaccination report+[HUC]”.

We collected country-level metadata for all analyses and retrieved data for a specific time. In addition, we did not select any particular categories and subcategories when searching for keywords. The time for the data retrieval started from the first confirmed COVID-19 case in the Philippines and ended on January 31, 2023. This time frame allowed us to conduct a more in-depth examination of the search trends.

Data on COVID-19 cases reported by date of illness onset for each HUC beginning February 27, 2020, until January 31, 2023, were extracted from DOH COVID-19 Tracker Dashboard (

https://doh.gov.ph/covid19tracker). The DOH COVID-19 tracker is a public dashboard showing a daily tally of confirmed COVID-19 cases, positivity rate, occupancy rate of medical health facilities, and aggregated case information (DOH, 2020).

To obtain data on control strategies/PHIs implemented in the selected HUCs, different local and national COVID-19 policies were retrieved from their respective websites. National and local legislations and executive issuances (e.g., executive orders, proclamations, memorandum orders, memorandum circulars, presidential decrees, letters of instruction, letters of implementation, administrative orders, special orders, and general orders) were reviewed. Recommendations of the Interagency Task Force (IATF) and the National Task Force (NTF) for COVID-19, official LGU web pages and verified Facebook accounts, official newspaper articles, and COVID-19 protocols, guidelines, and action plans from March 3, 2020, to January 31, 2023, were also evaluated.

National and regional vaccination statistics were obtained from the DOH National COVID-19 Vaccination Dashboard (

https://doh.gov.ph/covid19-vaccination-dashboard). Each selected HUC’s most recent reported vaccination coverage was obtained from either the LGU’s official Facebook account, the Department of Health Regional Center for Health Development, or reputable newspaper articles.

Data Analysis

Categorization and Data Quality Assessment of Web Resources

Web resources were categorized based on the sources of data (website or social media), types of affiliation (international organization, national or local government, news), and language (English or Filipino) (Cuan-Baltazar et al., 2020). The web resources were also grouped based on the type of analysis presented.

The quality of web resources was assessed using Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) benchmarks. The JAMA benchmark employs four core standards to evaluate web resources: Authorship, Attribution, Disclosure, and Currency (Silberg et al., 1997). Authorship was scored if the web resources showed the author/s, contributors, affiliations, and credentials. Attribution is the provision of all references and sources for the web resources’ content and relevant copyright information. Disclosure refers to the web resources’ “ownership,’’ such as sponsors and funding arrangements. Currency indicates the date of posting and updating of the web resources.

Two evaluators (LJLB and RMM) initially assessed the included web resources using the JAMA benchmark, and a third evaluator (MCBO) settled conflicts in scoring if a dispute arose. There was no established acceptable or cut-off JAMA Benchmark score across the literature. Hence, the authors included all web resources with scores of 1 and above.

Open Government Data Analysis and Synthesis

The timeline of COVID-19 PHIs was generated using the reconstructed epi-curves for the entire Philippines and each representative HUC from February 2020 to January 2023. The prevention and control strategies (PHIs) implemented from February 2020 to January 2023 in the City of Manila, Quezon City, Cebu City, and Davao City were categorized into case management, contact management, control of imported cases, behavior modification, and pharmaceutical interventions. The categories of non-pharmaceutical interventions were adapted with a few modifications from previous literature (Liu et al., 2021).

3. Results

Identification, Screening, and Assessment of OGD Web Sources

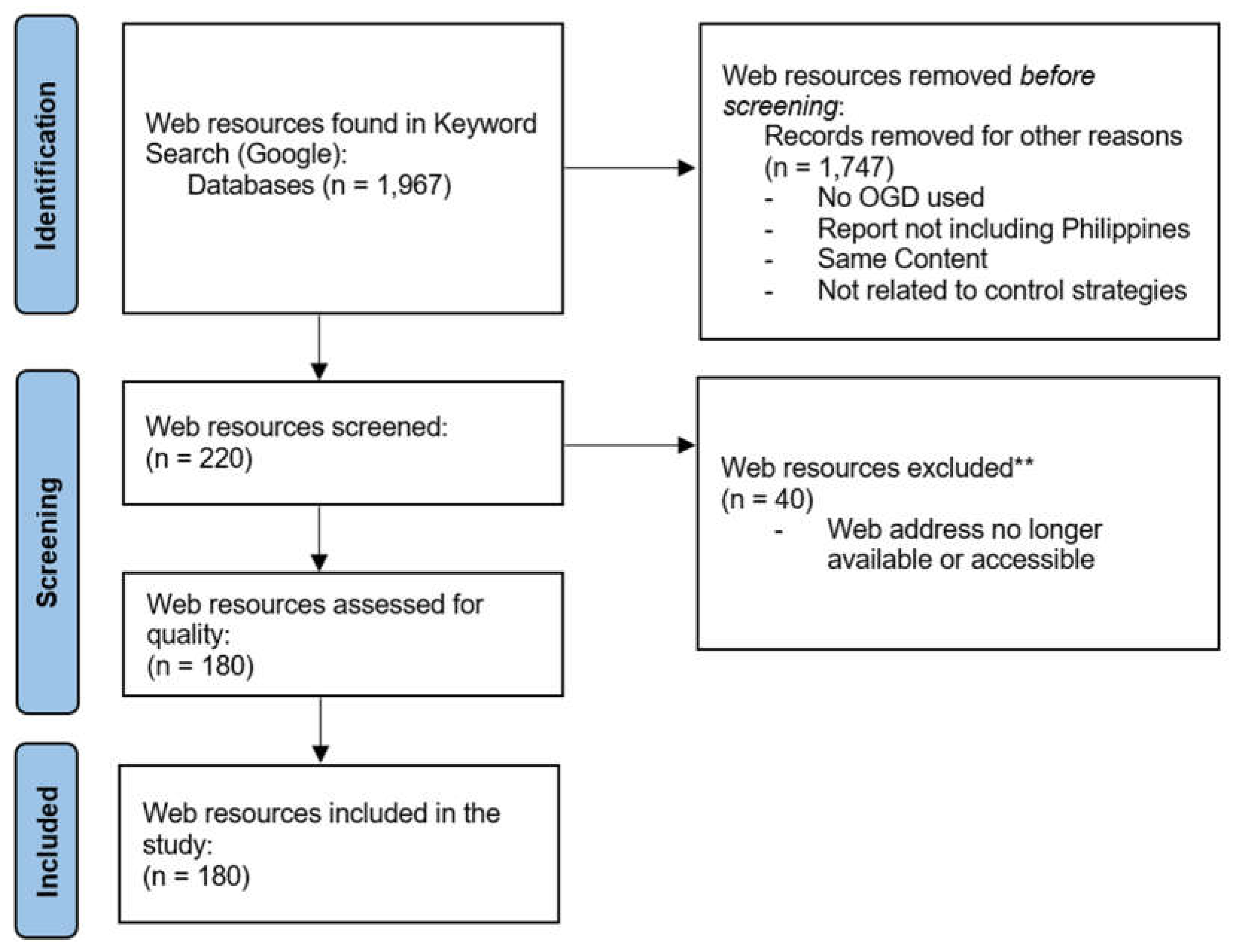

A total of 1,967 metadata from Google searches were identified, of which 1,747 were removed as these did not include/use OSGD, or did not report about the Philippines, or had the same content. From the 220 metadata, 40 were removed after screening because the web addresses were no longer available, or the reports were done outside the Philippines (see

Figure 1 for details). After data quality assessment using the JAMA benchmark, all web resources included in this study achieved at least 2 of the four core standards, with a mean (±SD) JAMA score of 3.03 (±0.90). About 30.0% of the identified OSGD sources achieved 2 JAMA benchmark criteria, 11.1% achieved three criteria, and 58.9% achieved all four criteria. All web resources have Currency and Authorship, while only 36.1% had Attribution and 35.0% had Disclosure.

In terms of sources of data, 93.3% of the web resources were from official websites, while only 6.7% were from social media. Most of the web resources on control strategies (PHIs) were published by the National Government (43.3%) and the Local Government (28.9%), followed by online newspapers (25.6%), and lastly, academic institutions (1.7%). Reused OSGD appearing in news articles were published by private news agencies (56.5%) and the government-owned Philippines News Agency (43.5%). Most web resources were written in English (97.8%), and only 4 (2.2%) were written in Filipino.

COVID-19 HUC Control Strategies (PHIs)

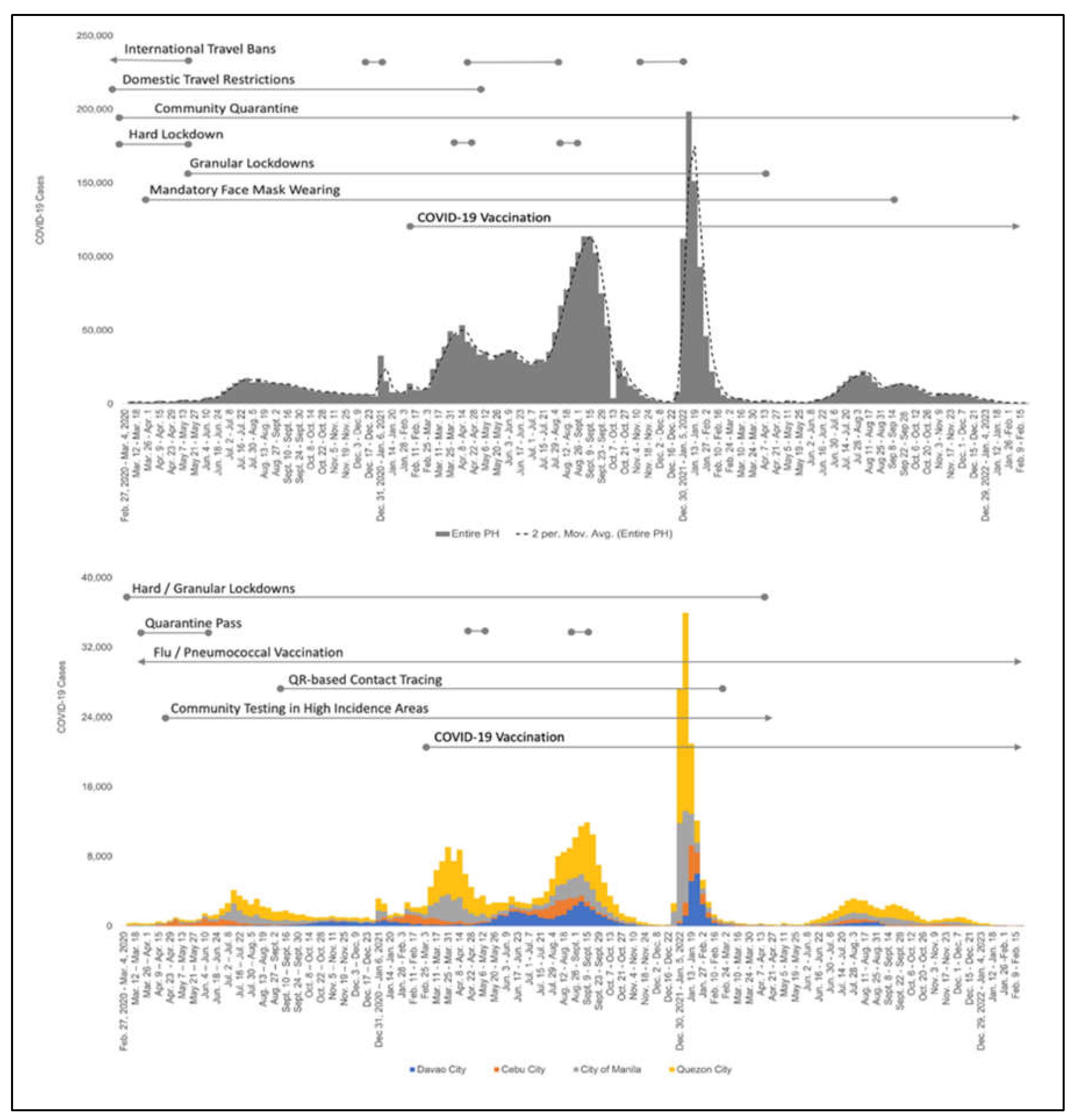

Figure 2 shows the epidemic curves and timeline of the major PHIs against COVID-19 in the Philippines and the four representative HUCs (Quezon City and City of Manila, Cebu City, and Davao City). At least five surges of COVID-19 cases were observed in the entire Philippines and the representative HUCs, with the most significant number of reported cases occurring from December 30, 2021, to January 5, 2022.

Table 1 summarizes the specific control strategies implemented in the four HUCs categorized by the focus of the interventions. The first case of locally transmitted COVID-19 in the Philippines was confirmed on March 7, 2020 (Edrada et al., 2020). In response, the entire country was placed under a State of Public Health Emergency on March 8, 2020, and a State of Calamity on March 16, 2020 (Arguelles, 2021). The National Capital Region and most of Luzon were placed under Enhanced Community Quarantine (hard lockdown) from March 17 until May 15, 2020 (Manacsa et al., 2023).

For the first twelve months of the COVID-19 pandemic, prevention and control strategies were focused on (a) the control of imported cases (travel restrictions), and (b) behavioral modifications (lockdowns, wearing of face masks), while (c) case management and (d) contact management (QR-based contact tracing, use of quarantine pass, community testing) were important once sustained local transmission of COVID-19 was observed. Free flu and pneumococcal vaccinations for the elderly were also implemented to protect against severe COVID-19 infection starting in March 2020 (

Table 2). In Davao City, only one COVID-19 Referral Hospital, Southern Philippines Medical Center (SPMC), operated from March to November 2020 to maximize the use of scarce resources for COVID-19 response while effective management and treatment were being optimized, and while testing capacity in private laboratories and hospitals was still being developed (Lacorte, 2021). Private hospitals were requested to open COVID-19 wards only during COVID-19 surges when bed capacity in the SPMC reached critical levels. All confirmed COVID-19 cases from March 2020 to September 2021 were isolated in Temporary Treatment and Monitoring Facilities (TTMFs) since home isolation was prohibited (Quillamor et al., 2021).

COVID-19 vaccine roll-out in the Philippines began on March 1, 2021 (Escosio et al., 2023). Frontline health workers were given priority, followed by senior citizens, people with comorbidities, indigents, and the rest of the population, considering the risk of exposure, death, and vaccine supply (Escosio et al., 2023). As of March 19, 2023, over 179.04 million COVID-19 vaccines have been administered in the country, and 103.34 million Filipinos are fully vaccinated or have received one booster dose.

The national and local government units in the Philippines also engaged the private sector, local and international civic groups, and the academe to support the implementation and improve the effectiveness of PHIs against COVID-19. Civic society provided massive donations (cash and in-kind) of medical supplies, COVID-19 testing kits and equipment, and logistical and training support to the medical front liners before COVID-19 vaccines were available (Rampal et al., 2020).

4. Discussion

Open-source data, whether from the government, non-government agencies, or the private sector, is a vital source of health data for public health surveillance and interventions for lower middle-income island countries like the Philippines with variable public health surveillance resources and infrastructure. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, massive amounts of health-related government data on the COVID-19 response were made available to the public (Assefa et al., 2022), and open data infrastructure in Philippine HUCs evolved quickly. COVID-19-related open data (e.g., case information, COVID-19 epi curves, COVID-19 risk categories, health facility utilization, vaccination accomplishment and coverage, etc.) were regularly shared not only by the Department of Health (

https://doh.gov.ph/covid19tracker) and other national government agencies, but also by local governments units and DOH counterparts in the regions, provinces, cities, and barangays (or the smallest unit of government in the Philippines). Our study demonstrates how major public health interventions implemented by the national and local government units in the Philippines as part of the COVID-19 response can be reconstructed chronologically from high-quality web resources that contain or reuse open-source government data (OSGD).

The timely declaration of travel restrictions was vital in reducing the importation rate of SARS-CoV-2 and its more contagious variants. International air travel significantly contributed to the global spread of COVID-19, prompting the Philippines to implement early travel bans to delay the introduction of the virus to the cities and provinces (Sharun et al., 2020). Its effects are evident in the flattening of the epi curves in the Philippines during the first three COVID-19 surges (between June 2020 and November 2021) (

Figure 1A). However, their benefits diminish once local transmission becomes widespread (Russell et al., 2021).

With vaccines and effective treatments unavailable during the first year of the pandemic, the Philippines relied heavily on non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) like mobility restrictions and social distancing to curb COVID-19 transmission. Social distancing reduces the interaction between susceptible individuals and pre-symptomatic, asymptomatic, or symptomatic COVID-19 cases (Aquino et al., 2020). Mask-wearing is crucial when social distancing is inadequate or impossible. The hard lockdown in Luzon from February to May 2020 delayed the spread of SARS-CoV-2 to other regions and cities in the Philippines, and this was crucial since testing capacity and healthcare infrastructure were still developing (Amit et al., 2022). A study of 27 countries, including the Philippines, showed that hard lockdowns significantly reduced the growth of daily COVID-19 cases and deaths after 15 days (Meo et al., 2020). Manchein et al. (2020) also found that soft lockdowns alone were inefficient in reducing COVID-19 transmission during the alert phase (early stages with limited human-to-human transmission) of the pandemic.

During lockdowns, significant social and economic hardships emerged while the spread of COVID-19 was controlled. Nine HUCs in the Philippines found that over 62% of households faced food insecurity during hard lockdowns due to a lack of funds (Angeles-Agdeppa et al., 2022). National and local governments have carried out economic support measures (ESM) such as food subsidies and the distribution of food packs as sanctioned by national and local policies. ESMs can enhance the effectiveness of high-severity interventions (such as large-scale lockdowns) in reducing COVID-19 infections by lowering the work hours needed to provide the basic needs of low-income households (Aquino et al., 2020; Dergiades et al., 2023). Moreover, ESMs must be put in place, especially in HUCs, to increase the acceptance and adherence of the constituents to stringent lockdowns.

Local governments units played a key role by conducting local risk assessments while adhering to national guidelines. Aspects of COVID-19 outbreaks may vary in each locale, and thus, require comprehensive and tailor-fitted PHIs in HUCs. The country’s unique geography and high population density, especially in urban areas like the City of Manila and Quezon City, influence the spread of contagions and the effectiveness of response measures. Moreover, higher population density complicates social distancing and predicts increased COVID-19 transmission rates, highlighting the need for localized prevention strategies (Chen & Li, 2020; Kodera et al., 2020; Kousi et al., 2022; Martins-Filho, 2021; Wong & Li, 2020), which most of the HUCs implemented in the Philippines.

The scenario of local COVID-19 epidemics in cities and provinces may vary at certain timepoints, hence, specific interventions may be needed to control local outbreaks. The availability of OSGD may have enhanced local COVID-19 responses, enabling data-driven decisions and sharing of good practices among LGUs. One of the good practices in the local control of COVID-19 include the use of quarantine passes, curfews, and liquor bans during hard lockdowns to limit the movement of their constituents to access basic needs only. Quick Response (QR)-based contact tracing was also adopted in HUCs included in this study to aid the government in identifying cases and their contacts (Ramos et al., 2023). Identifying persons with an increased risk of infection due to exposure to confirmed COVID-19 cases assisted the gradual resumption of normal activities without sacrificing COVID-19 containment and mobility control (Nakamoto et al., 2020). Several HUC LGUs also imposed fines on individuals for not wearing masks in public spaces. To this day, mask-wearing is still imposed even after all other COVID-19 related mandatory requirements were lifted, especially in poorly ventilated or crowded areas because mask-wearing benefits extend beyond COVID-19 prevention (Dans et al., 2023).

Community testing in high-risk areas and free public swabbing for RT-PCR were also implemented in selected HUCs in the Philippines to quickly identify cases and their contacts (Yang et al., 2024). Regular mass testing of the general population, as done in countries like South Korea and Germany, drastically reduce new cases of emerging infectious diseases like COVID-19 by detecting symptomatic, asymptomatic, or pre-symptomatic individuals (Aquino et al., 2020; Philippe et al., 2023). Early detection of infections, timely isolation of cases, and quarantine of their contacts can be implemented to curb further COVID-19 transmission (Wilder-Smith & Freedman, 2020). Mass testing is more effective than contact tracing, considering the airborne transmission of COVID-19, where transmission may extend to individuals with no contact with known cases (Philippe et al., 2023). Furthermore, non-invasive wastewater surveillance can complement individual or pooled testing for faster and more cost-efficient screening covering a large population at one time (Otero et al., 2022).

Among the PHIs implemented in the Philippines during the pandemic, the pharmaceutical intervention of massive COVID-19 vaccination was the most effective and long-lasting. In the Philippines, COVID-19 vaccination by priority groups started on March 2021 with healthcare frontliners, and then expanded to the elderly population and persons with comorbidities, other frontliners in essential sectors, and the indigent community, and the rest of the population as more COVID-19 vaccines became available (Philippine News Agency, 2021 February 6). By July 2022, 70.5% of the population was fully vaccinated (Cardenas, 2022).

COVID-19 vaccines protect against severe illness, even with the emergence of more transmissible variants like Delta and Omicron (Khan et al., 2022). Using global vaccination data, Singh et al. (2024) observed that COVID-19 vaccination substantially reduced the incidence and number of hospitalizations due to COVID-19 as early as 90 days after targeted immunizations. However, it should be emphasized that continued adherence to non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) like contact tracing, social distancing, mask-wearing, social distancing, and isolation is essential to benefit from protection afforded by COVID-19 vaccination (Moghadas et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2024). In the Philippines, the beneficial effects of COVID-19 vaccination were initially limited possibly due to the prioritization of high-risk groups, constrained vaccine supply, vaccine delivery challenges in the Philippine archipelago (Zhao et al., 2024), and vaccine hesitancy especially in the elderly population (Tejero et al., 2023). A good practice in Philippine HUCs like Davao City is their mobile vaccination campaign targeting the elderly to ensure greater vaccine coverage in this vulnerable population (Llemit, 2021 August 11).

As cases of locally transmitted COVID-19 rose daily and new variants emerged, it became apparent that a successful national and local control program against COVID-19 required a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach (Ortenzi et al., 2022). Public-private partnerships facilitated speedy vaccine procurement, efficient vaccine distribution systems, and incentivized vaccination (Daems & Maes, 2022). Similar trends were seen in low-resource countries like Nepal, Ghana, Bangladesh, and Nigeria, where the public-private partnerships augmented the resources for public health response and mitigated the economic impact of the pandemic by ensuring that industries and services continued to operate (Wallace et al., 2022). Furthermore, public-private partnerships and engagement of stakeholders must be strengthened in the national and local EID preparedness programs, and regulatory frameworks that align with these programs must be developed (Kabwama et al., 2022).

In this study, only the internet sources with at least two JAMA benchmarks (Authorship and Currency) were considered good-quality resources with valid and reliable information. JAMA benchmarks can be used to assess the quality of any web resource, whether health related or not, however, JAMA benchmarks cannot be used for comprehensive assessments (Cassidy and Baker, 2016). Other quality assessment tools, such as HONcode and Google Ranks, can also be used, but the choice of tool should be based on the objectives of the study. HONcode is a website certification issued based on ethical standards in offering quality health information and is approved and used by the World Health Organization (HONcode, 2000). HONcode certification can be obtained after voluntary registration of the website, hence, there may be credible websites without this certification (The Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority, 2011; Mac et al., 2020). Google ranks can also be used to determine the relative importance of a web resource by ranking the number and quality of links associated with it (Cuan-Baltazar et al., 2023), however, whether the health information written is credible cannot be reliably determined using Google ranks alone.

Our paper assessed control strategies from four HUCs in the Philippines. However, our study does not capture all innovative and locally relevant measures implemented in other HUCs, independent component cities, municipalities, and provinces across the country. In addition, the OSGD used in this study to assess the COVID-19 public health control strategies and interventions only included data repurposed from online news outlets and official social media accounts of local government units (LGUs). Furthermore, a comprehensive analysis of the utilization and re-utilization of OSGD throughout the COVID-19 response in the Philippines is warranted since it is beyond the scope of this study.

In summary, the timely declarations of international and local travel bans, and hard lockdowns were crucial in the alert phase of the pandemic by controlling case importation and modifying behaviors to reduce COVID-19 transmission. Once sustained local COVID-19 transmission was observed, case and contact management PHIs were widely implemented in HUCs before COVID-19 vaccines became available. Pharmaceutical interventions, specifically the COVID-19 vaccination, was the most effective and longest-lasting PHI in the Philippines. Massive vaccination campaigns in the HUCs were achieved by engaging the private sector, academe, and civic societies. Data sharing and open knowledge on locally implemented public health interventions against COVID-19 were vital the COVID-19 response in the Philippines since the availability of PHI-related OSGD promoted innovation and rapid sharing of good practices among local government units. Highly urbanized cities from low- and middle-income countries may also benefit from the experiences of Philippine HUCs at different stages of the pandemic. Lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic must be integrated into maintaining and improving national and local epidemic preparedness programs against emerging or re-emerging infections.

5. Conclusions

Hard lockdowns at the start of the pandemic delayed the introduction of COVID-19 to other areas in the Philippines. Local risk assessments using OSGD prompted LGUs to be innovative and to follow good practices of other LGUs to improve local control of COVID-19 while still adhering to the minimum community quarantine protocols set by the national government. These COVID-19 Public Health Control Strategies and Interventions include quarantine passes, setting curfews and liquor bans, using QR-based contact tracing, implementing massive community testing in high-risk communities, and opening public and free swabbing centers. The national and local governments engaged stakeholders such as the private sector, the academe, and civic groups in improving the country’s COVID-19 response. Lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic must be integrated into maintaining and improving national and local epidemic preparedness programs against emerging or re-emerging infections. The developments in health-related OSGD brought by the COVID-19 pandemic should be sustained and extended to other sectors of society to encourage innovation and involvement.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB 2021-0314-01).

Contributors

MCBO: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing; LJLB: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation; Writing - original draft; RMM: Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing - original draft; ZJGR: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing; LEM: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing; ESB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. All authors contributed substantially to the development, revision, and finalization of the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the 1) Science Education Institute of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) through the Advanced Science and Technology Human Resource and Development Program Scholarship of Ms. Otero at the University of the Philippines Manila, and 2) the DOST Philippine Council for Health and Research Development (PCHRD) funded project, “Integrated Wastewater-Based Epidemiology and Data Analytics for Community-Level Pathogen Surveillance and Genetic Tracking” under the University of the Philippines Mindanao.

References

- Amit, A. M. L., Pepito, V. C. F., Sumpaico-Tanchanco, L., & Dayrit, M. M. (2022). COVID-19 vaccine brand hesitancy and other challenges to vaccination in the Philippines. PLOS Global Public Health, 2(1), e0000165. [CrossRef]

- Angeles-Agdeppa, I., Javier, C. A., Duante, C. A., & Maniego, M. L. V. (2022). Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on household food security and access to social protection programs in the Philippines: findings from a telephone rapid nutrition assessment survey. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 43(2), 213-231. [CrossRef]

- Aquino, E. M., Silveira, I. H., Pescarini, J. M., Aquino, R., Souza-Filho, J. A. d., Rocha, A. d. S., Ferreira, A., Victor, A., Teixeira, C., & Machado, D. B. (2020). Social distancing measures to control the COVID-19 pandemic: potential impacts and challenges in Brazil. Ciencia & saude coletiva, 25, 2423-2446.

- Arguelles, C. V. (2021). The Populist Brand is Crisis. Southeast Asian Affairs, 257-274.

- Assefa, Y., Gilks, C. F., Reid, S., van de Pas, R., Gete, D. G., & Van Damme, W. (2022). Analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons towards a more effective response to public health emergencies. Globalization and health, 18(1), 10. [CrossRef]

- Brauner, J. M., Mindermann, S., Sharma, M., Johnston, D., Salvatier, J., Gavenčiak, T., Stephenson, A. B., Leech, G., Altman, G., & Mikulik, V. (2021). Inferring the effectiveness of government interventions against COVID-19. Science, 371(6531), eabd9338. [CrossRef]

- Cardenas N. C. (2022). Correspondence Harnessing strategic policy on COVID-19 vaccination rollout in the Philippines. Journal of public health (Oxford, England), 44(2), e279–e280. [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, J. T., & Baker, J. F. (2016). Orthopaedic patient information on the World Wide Web: an essential review. JBJS, 98(4), 325-338.

- Chen, K., & Li, Z. (2020). The spread rate of SARS-CoV-2 is strongly associated with population density. Journal of travel medicine, 27(8), taaa186.

- Cuan-Baltazar, J. Y., Muñoz-Perez, M. J., Robledo-Vega, C., Pérez-Zepeda, M. F., & Soto-Vega, E. (2020). Misinformation of COVID-19 on the internet: infodemiology study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(2), e18444. [CrossRef]

- Daems, R., & Maes, E. (2022). The race for COVID-19 vaccines: accelerating innovation, fair allocation and distribution. Vaccines, 10(9), 1450. [CrossRef]

- Dergiades, T., Milas, C., Mossialos, E., & Panagiotidis, T. (2023). COVID-19 anti-contagion policies and economic support measures in the USA. Oxford Economic Papers, 75(3), 613-630. [CrossRef]

- Desvars-Larrive, A., Dervic, E., Haug, N., Niederkrotenthaler, T., Chen, J., Di Natale, A., Lasser, J., Gliga, D. S., Roux, A., & Sorger, J. (2020). A structured open dataset of government interventions in response to COVID-19. Scientific data, 7(1), 285. [CrossRef]

- DOH. (2020). DOH LAUNCHES NEW COVID-19 TRACKER AND DOH DATACOLLECT APP PRESS RELEASE /13 APRIL 2020. Department of Health. Retrieved September from https://doh.gov.ph/doh-press-release/DOH-LAUNCHES-NEW-COVID-19-TRACKER-AND-DOH-DATACOLLECT-APP.

- Edrada, E. M., Lopez, E. B., Villarama, J. B., Salva Villarama, E. P., Dagoc, B. F., Smith, C., Sayo, A. R., Verona, J. A., Trifalgar-Arches, J., & Lazaro, J. (2020). First COVID-19 infections in the Philippines: a case report. Tropical medicine and health, 48, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Escosio, R. A. S., Cawiding, O. R., Hernandez, B. S., Mendoza, R. G., Mendoza, V. M. P., Mohammad, R. Z., Pilar-Arceo, C. P., Salonga, P. K. N., Suarez, F. L. E., & Sy, P. W. (2023). A model-based strategy for the COVID-19 vaccine roll-out in the Philippines. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 573, 111596. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S., & Eykelbosh, A. (2020). COVID-19 and outdoor safety: Considerations for use of outdoor recreational spaces. National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health, 829, 1-15.

- González-Zapata, F., Rivera, A., Chauvet, L., Emilsson, C., Zahuranec, A. J., Young, A., & Verhulst, S. (2021). Open data in action: initiatives during the initial stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Available at SSRN 3937613.

- GovPH. (2023). Open Data Philippines. Republic of the Philippines. https://data.gov.ph/index/about-us.

- Hartley, D. M., & Perencevich, E. N. (2020). Public health interventions for COVID-19: emerging evidence and implications for an evolving public health crisis. Jama, 323(19), 1908-1909.

- HON code of conduct for medical and health Web sites. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2000;57(13):1283. [CrossRef]

- Kabwama, S. N., Kiwanuka, S. N., Mapatano, M. A., Fawole, O. I., Seck, I., Namale, A., Ndejjo, R., Kizito, S., Monje, F., & Bosonkie, M. (2022). Private sector engagement in the COVID-19 response: experiences and lessons from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, Senegal and Uganda. Globalization and health, 18(1), 60. [CrossRef]

- Khan, K., Khan, S. A., Jalal, K., Ul-Haq, Z., & Uddin, R. (2022). Immunoinformatic approach for the construction of multi-epitopes vaccine against omicron COVID-19 variant. Virology, 572, 28-43. [CrossRef]

- Kodera, S., Rashed, E. A., & Hirata, A. (2020). Correlation between COVID-19 morbidity and mortality rates in Japan and local population density, temperature, and absolute humidity. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(15), 5477. [CrossRef]

- Kousi, T., Vivacqua, D., Dalal, J., James, A., Câmara, D. C. P., Mesa, S. B., Chimbetete, C., Impouma, B., Williams, G. S., & Mboussou, F. (2022). COVID-19 pandemic in Africa’s island nations during the first 9 months: a descriptive study of variation in patterns of infection, severe disease, and response measures. BMJ global health, 7(3), e006821.

- Lacorte, G. (2021). Davao City assigns SPMC as sole hospital for COVID-19 patients. Retrieved March 30 from https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1510470/davao-city-assigns-spmc-as-sole-hospital-for-covid-19-patients#ixzz83HL0j0FH.

- Lai, S., Ruktanonchai, N. W., Zhou, L., Prosper, O., Luo, W., Floyd, J. R., Wesolowski, A., Santillana, M., Zhang, C., & Du, X. (2020). Effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions to contain COVID-19 in China. Nature, 585(7825), 410-413. [CrossRef]

- Lemecha Obsu, L., & Feyissa Balcha, S. (2020). Optimal control strategies for the transmission risk of COVID-19. Journal of biological dynamics, 14(1), 590-607. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Morgenstern, C., Kelly, J., Lowe, R., & Jit, M. (2021). The impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on SARS-CoV-2 transmission across 130 countries and territories. BMC Medicine, 19(1), 1-12.

- Llemit, R. L. G. (2021 August 11). Davao City starts mobile vaccination for seniors. Sunstar Publishing, Inc. https://www.sunstar.com.ph/davao/local-news/davao-city-starts-mobile-vaccination-for-seniors. Accessed on December 30, 2024.

- Mac, O. A., Thayre, A., Tan, S., & Dodd, R. H. (2020). Web-based health information following the renewal of the cervical screening program in Australia: evaluation of readability, understandability, and credibility. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e16701. Accessed on July 23, 2020.

- Madubueze, C. E., Dachollom, S., & Onwubuya, I. O. (2020). Controlling the spread of COVID-19: optimal control analysis. Computational and Mathematical methods in Medicine, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Manacsa, M. C., Vigonte, F. G., & Abante, M. V. (2023). Economic Issues Significantly Affected by the COVID-19 Pandemic and Policies Implemented by the Government to Mitigate Its Impact. Available at SSRN 4340267.

- Manchein, C., Brugnago, E. L., da Silva, R. M., Mendes, C. F., & Beims, M. W. (2020). Strong correlations between power-law growth of COVID-19 in four continents and the inefficiency of soft quarantine strategies. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science, 30(4). [CrossRef]

- Martins-Filho, P. R. (2021). Relationship between population density and COVID-19 incidence and mortality estimates: A county-level analysis. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 14(8), 1087. [CrossRef]

- Meo, S. A., Abukhalaf, A. A., Alomar, A. A., AlMutairi, F. J., Usmani, A. M., & Klonoff, D. C. (2020). Impact of lockdown on COVID-19 prevalence and mortality during 2020 pandemic: observational analysis of 27 countries. European journal of medical research, 25(1), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Moghadas, S. M., Vilches, T. N., Zhang, K., Wells, C. R., Shoukat, A., Singer, B. H., Meyers, L. A., Neuzil, K. M., Langley, J. M., & Fitzpatrick, M. C. (2021). The impact of vaccination on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreaks in the United States. Clinical infectious diseases, 73(12), 2257-2264. [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, I., Wang, S., Guo, Y., & Zhuang, W. (2020). A QR code–based contact tracing framework for sustainable containment of COVID-19: Evaluation of an approach to assist the return to normal activity. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(9), e22321. [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2018). Embracing Innovation in Government: Global Trends 2018. In: OECD Paris.

- Ornell, F., Schuch, J. B., Sordi, A. O., & Kessler, F. H. P. (2020). “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: mental health burden and strategies. In (Vol. 42, pp. 232-235): SciELO Brasil.

- Ortenzi, F., Marten, R., Valentine, N. B., Kwamie, A., & Rasanathan, K. (2022). Whole of government and whole of society approaches: call for further research to improve population health and health equity. In (Vol. 7, pp. e009972): BMJ Specialist Journals. [CrossRef]

- Otero, M. C. B., Murao, L. A. E., Limen, M. A. G., Caalim, D. R. A., Gaite, P. L. A., Bacus, M. G., Acaso, J. T., Miguel, R. M., Corazo, K., & Knot, I. E. (2022). Multifaceted assessment of wastewater-based epidemiology for SARS-CoV-2 in selected urban communities in Davao City, Philippines: a pilot study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(14), 8789.

- Paddock, R., & Sijabat, D. (2020). Indonesia overtakes the Philippines as the hardest-hit country in Southeast Asia. The New York Times, 16.

- Park, C.-Y., Kim, K., & Roth, S. (2020). Global shortage of personal protective equipment amid COVID-19: supply chains, bottlenecks, and policy implications. Asian Development Bank.

- Park, C. H., Richards, R. C., & Reedy, J. (2022). Assessing emergency information sharing between the government and the public during the COVID-19 pandemic: An open government perspective. Public Performance & Management Review, 1-32. [CrossRef]

- Perkins, T. A., & España, G. (2020). Optimal control of the COVID-19 pandemic with non-pharmaceutical interventions. Bulletin of mathematical biology, 82(9), 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Philippe, C., Bar-Yam, Y., Bilodeau, S., Gershenson, C., Raina, S. K., Chiou, S.-T., Nyborg, G. A., & Schneider, M. F. (2023). Mass testing to end the COVID-19 public health threat. The Lancet Regional Health–Europe, 25. [CrossRef]

- Philippine News Agency, 2021 February 6.IATF adopts Covid-19 vaccination priority framework. Accessed on May 30, 2023 at https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1129880.

- Quillamor, K. K., Regalado, D. M., Romualdo, R. A., Sandig, K., Secondes, J. R., Sicat, A. G., Sigaya, K. E., Firmase, J., Padilla, P. I., & Puno, A. (2021). In-depth Analysis of Iloilo City’s Health System Based on COVID-19 Pandemic Response.

- Ramos, T. P., Lorenzo, P. J. M., Ancheta, J. A., & Ballesteros, M. M. (2023). Are Philippine Cities Ready to Become Smart Cities? Philippine Institute for Development Studies Research Papers, 2023(2).

- Rampal, L., Liew, B., Choolani, M., Ganasegeran, K., Pramanick, A., Vallibhakara, S., Tejativaddhana, P., & Hoe, V. (2020). Battling COVID-19 pandemic waves in six South-East Asian countries: A real-time consensus review. Med J Malaysia, 75(6), 613-625.

- Rivera, R. L. K. (2010). Gender and Transport: Experiences of Marketplace Workers in Davao City, Philippines. Environment and Urbanization ASIA, 1(2), 171-186.

- Russell, T. W., Wu, J. T., Clifford, S., Edmunds, W. J., Kucharski, A. J., & Jit, M. (2021). Effect of internationally imported cases on internal spread of COVID-19: a mathematical modelling study. The Lancet Public Health, 6(1), e12-e20. [CrossRef]

- S Talabis, D. A., Babierra, A. L., H Buhat, C. A., Lutero, D. S., Quindala, K. M., & Rabajante, J. F. (2021). Local government responses for COVID-19 management in the Philippines. BMC public health, 21(1), 1-15.

- Sasmita, N. R., Ikhwan, M., Suyanto, S., & Chongsuvivatwong, V. (2020). Optimal control on a mathematical model to pattern the progression of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Indonesia. Global Health Research and Policy, 5(1), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A., & Khavarian-Garmsir, A. R. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on cities and major lessons for urban planning, design, and management. Science of The Total Environment, 749, 142391. [CrossRef]

- Sharun, K., Tiwari, R., Natesan, S., Yatoo, M. I., Malik, Y. S., & Dhama, K. (2020). International travel during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications and risks associated with ‘travel bubbles’. In (Vol. 27, pp. taaa184): Oxford University Press.

- Silberg, W. M., Lundberg, G. D., & Musacchio, R. A. (1997). Assessing, controlling, and assuring the quality of medical information on the Internet: Caveant lector et viewor—Let the reader and viewer beware. Jama, 277(15), 1244-1245.

- Singh, P., Anand, A., Rana, S., Kumar, A., Goel, P., Kumar, S., Gouda, K. C., & Singh, H. (2024). Impact of COVID-19 vaccination: a global perspective. Frontiers in public health, 11, 1272961. [CrossRef]

- Tejero LM, Seva RR, Petelo Ilagan BJ, Almajose KL. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccination decision among Filipino adults. BMC Public Health. 2023 May 10;23(1):851. [CrossRef]

- The Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. 2011. National Report on Schooling in Australia 2009.

- URL: https://www.acara.edu.au/reporting/national-report-on-schooling-in-australia/nrosia2009. Accessed July 23, 2024.

- Tsay, C., Lejarza, F., Stadtherr, M., & Baldea, M. (2020). Modeling, state estimation and optimal control for the US COVID-19 outbreak. Sci. Rep. 10, 10711. In. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L. J., Agyepong, I., Baral, S., Barua, D., Das, M., Huque, R., Joshi, D., Mbachu, C., Naznin, B., & Nonvignon, J. (2022). The role of the private sector in the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences from four health systems. Frontiers in public health, 10, 878225. [CrossRef]

- Wang, V., & Shepherd, D. (2020). Exploring the extent of openness of open government data–A critique of open government datasets in the UK. Government Information Quarterly, 37(1), 101405. [CrossRef]

- WHO, C. O. (2020). World health organization. Responding to Community Spread of COVID-19. Reference WHO/COVID-19/Community_Transmission/2020.1.

- Wilder-Smith, A., & Freedman, D. O. (2020). Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. Journal of travel medicine, 27(2), taaa020. [CrossRef]

- Wong, D. W., & Li, Y. (2020). Spreading of COVID-19: Density matters. PloS one, 15(12), e0242398. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), 12 October 2020.

- Yang, J. E. U., Jackarain, F. H., de Vergara, T. I. M., Santillan, J. F., Reyes, P. W. C., Arellano, M. C. V. B., Garcia, J. T. U., Samonte, S. J. G., Marfori, A. J. G., & Guerrero, A. M. S. (2024). Acceptability of self-administered antigen test for COVID-19 in the Philippines. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 40(1), e10. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Wu S, Rafal RA, Manguerra H, Dong Q, Huang H, Lau L, Wei X. Vaccine equity implementation: exploring factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine delivery in the Philippines from an equity lens. BMC Public Health. 2024 Nov 5;24(1):3058. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K., & Xin, G. (2021). Who are the front-runners? Unravelling local government responses to containing the COVID-19 pandemic in China. China Review, 21(1), 37-54.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).