Submitted:

12 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Analytical Framework and Content Analysis

3. Theoretical Background

3.1. UAE COVID-19 Response Timeline

3.2. Governance and Accountability in Crisis Management

3.3. Implications for Future Crisis Preparedness

4. Empirical Results Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Addustour. UAE ‘G42’ and ‘BGI’ international are establishing a modern laboratory with superior diagnostic capabilities to combat ‘COVID-19’. Addustour, 2020. Available online: https://www.addustour.com/articles/1142913?s=4a1d8fd6a82b09286f188995a8ab90eb (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Ahmad, S.; Connolly, C.; Demirag, I. Testing times: Governing a pandemic with numbers. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, P.D.; Wickramasinghe, D. Pushing the limits of accountability: Big data analytics containing and controlling COVID-19 in South Korea. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, T.; Ferry, L. Accounting and accountability practices in times of crisis: A Foucauldian perspective on the UK government’s response to COVID-19 for England. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mahameed, M.; Belal, A.; Gebreiter, F.; Lowe, A. Social accounting in the context of profound political, social and economic crisis: The case of the Arab Spring. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsuwaidi, A.R.; Elbarazi, I.; Al-Hamad, S.; Aldhaheri, R.; Sheek-Hussein, M.; Narchi, H. Vaccine hesitancy and its determinants among Arab parents: A cross-sectional survey in the United Arab Emirates. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, J.; Baker, M.; Guthrie, J. Accounting, inequality and COVID-19 in Australia. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, C.; Guarini, E.; Steccolini, I. How do governments cope with austerity? The roles of accounting in shaping governmental financial resilience. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal. [CrossRef]

- Barbera, C.; Jones, M.; Korac, S.; Saliterer, I.; Steccolini, I. Local government strategies in the face of shocks and crises: The role of anticipatory capacities and financial vulnerability. International Review of Administrative Sciences 2021, 87(1), 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracci, E.; Saliterer, I.; Sicilia, M.; Steccolini, I. Accounting for (public) value(s): Reconsidering publicness in accounting research and practice. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Branicki, L.; Linnenluecke, M.K. COVID-19, societalization, and the future of business in society. Academy of Management Perspectives 2020, 34(4), 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelo, M.; Araújo, P. Ad hoc accounting and accountability for the local governance of an epidemic crisis: The yellow fever in Cádiz in 1800. De Computis - Revista Española de Historia de la Contabilidad. [CrossRef]

- Carungu, J.; Di Pietra, R.; Molinari, M. The impact of a humanitarian disaster on the working approach of accountants: A study of contingent effect. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, K.L.; Burritt, R.L. Accounting for modern slavery risk in the time of COVID-19: Challenges and opportunities. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNN Arabic. Watch. Build a laboratory to conduct coronavirus tests in the Emirates in 14 days. CNN Arabic, 1 April 2020. Available online: https://arabic.cnn.com/amphtml/health/video/2020/04/01/v87125-uae-based-covid-19-testing-lab-built-in-14-days (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Delfino, G.F.; van der Kolk, B. Remote working, management control changes and employee responses during the COVID-19 crisis. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2008, 62(1), 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Experian. Fraud rate rises 33% during the Covid lockdown. Experian, 2020. Available online: https://www.experianplc.com/media/news/2020/fraud-rate-rises-33-during-covid-19-lockdown/ (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- G42 Healthcare Innovations. AI in Healthcare; G42 Healthcare Innovations: Abu Dhabi, UAE, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, S. Coronavirus: Face masks sell out across the UAE. The National, 2020. Available online: https://www.thenational.ae/uae/health/coronavirus-face-masks-sell-out-across-the-uae-1.971394 (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Government of Dubai. Home isolation and quarantine guidelines during coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic, Third Issue. Government of Dubai, 2020, p. 1. Available online: https://www.dhcc.ae/gallery/COVID19_HomeIsolationGuidelines_v15.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures, and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today 2004, 24(2), 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulf News. COVID-19: UAE announces 45 new coronavirus cases. Gulf News, 2020. Available online: https://gulfnews.com/uae/covid-19-uae-announces-45-new-coronavirus-cases-1.1584969735068 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Gulf News. Coronavirus: UAE urges people to stay in their homes. Gulf News, 2020. Available online: https://gulfnews.com/uae/government/coronavirus-uae-urges-people-to-stay-in-their-homes-1.1584916668613 (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Gulf News. Coronavirus: UAE suspends all passenger and transit flights. Gulf News, 2020. Available online: https://gulfnews.com/business/aviation/coronavirus-uae-suspends-all-passenger-and-transit-flights-1.1584917287850 (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Haas, E.J.; Angulo, F.J.; McLaughlin, J.M.; Anis, E.; Singer, S.R.; Khan, F.; et al. Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: An observational study using national surveillance data. The Lancet 2021, 397(10287), 1819–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, A.; Chaudhary, S.B.; Hilotin, J. Watch: How the first coronavirus case in UAE was cured. Gulf News, 2020. Available online: https://gulfnews.com/uae/health/watch-how-the-first-coronavirus-case-in-uae-was-cured-1.1581323524356 (accessed on 22 January 2023).

- Hassan, A.; Nando, M.; Roberts, L. Does loss of biodiversity by businesses cause COVID-19? European Association for the Study of the UK, 2020. Available online: https://www.eauc.org.uk/does_loss_of_biodiversity_by_businesses_cause_c (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Hassan, A.; Nando, M.; Roberts, L.; Elamer, A.; Lodh, S. The future of business reporting: Learning from financial and COVID-19 crises. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 2005, 15(9), 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, C.; Gerhardt, N.; Reilley, J. Organizing care during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of accounting in German hospitals. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal. [CrossRef]

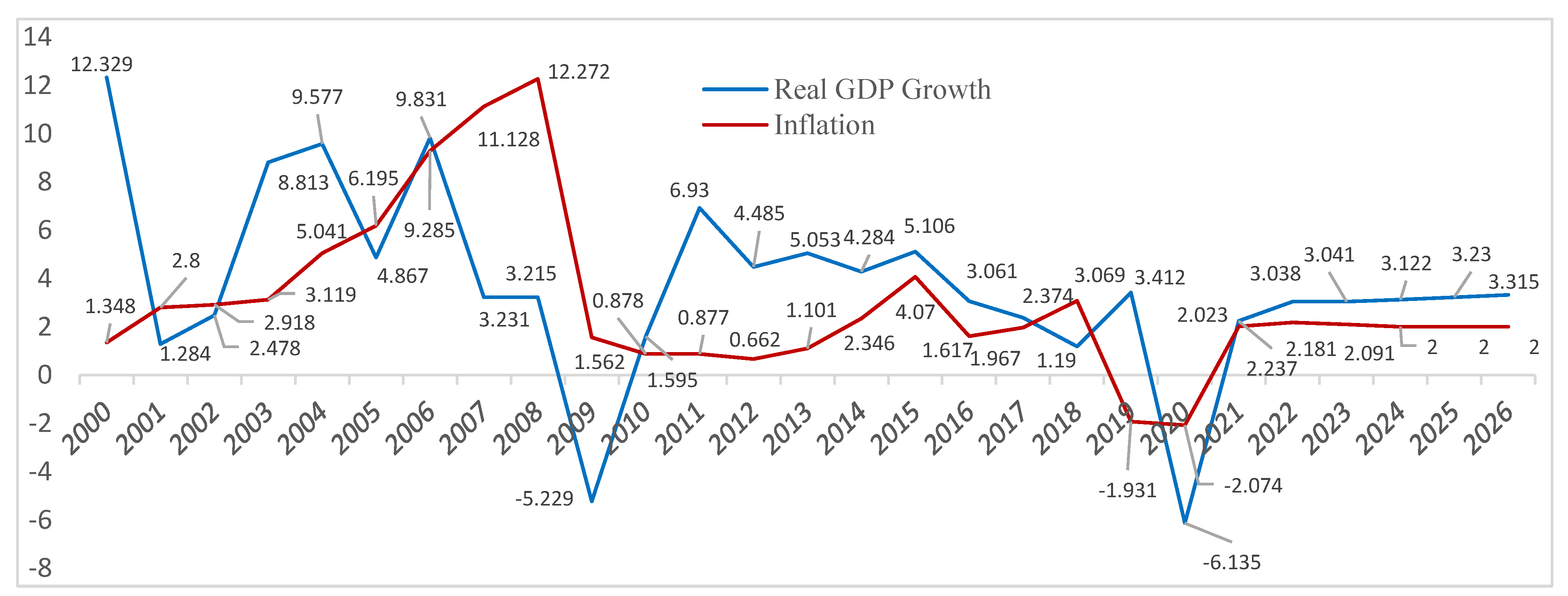

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). International Monetary Fund, UAE, 2022. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/ARE (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Lai, A.; Leoni, G.; Stacchezzini, R. The socialising effects of accounting in flood recovery. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 2014, 25(7), 579–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, H. Six months of COVID vaccines: What 1.7 billion doses have taught scientists. 7 billion doses have taught scientists. Nature 2021, 594(7862), 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leider, J.P.; DeBruin, D.; Reynolds, N.; Koch, A.; Seaberg, J. Ethical guidance for disaster response, specifically around crisis standards of care: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health 2017, 107(9), e9–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; McKernan, J.; Chen, M. Turning around accountability. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal. [CrossRef]

- Masoud, N.; Bohra, O.P. Challenges and opportunities of distance learning during COVID-19 in UAE. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal 2020, 24(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilal, S.; Adhikari, P. Accounting in Bhopal: Making catastrophe. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 2019, 72, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikidehaghani, M.; Cortese, C. (Job) keeping up appearances. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Enhancing public trust in COVID-19 vaccination: The role of governments. OECD, 2021. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=1094_1094290-a0n03doefx&title=Enhancing-public-trust-in-COVID-19-vaccination-The-role-of-governments (accessed on 23 August 2022).

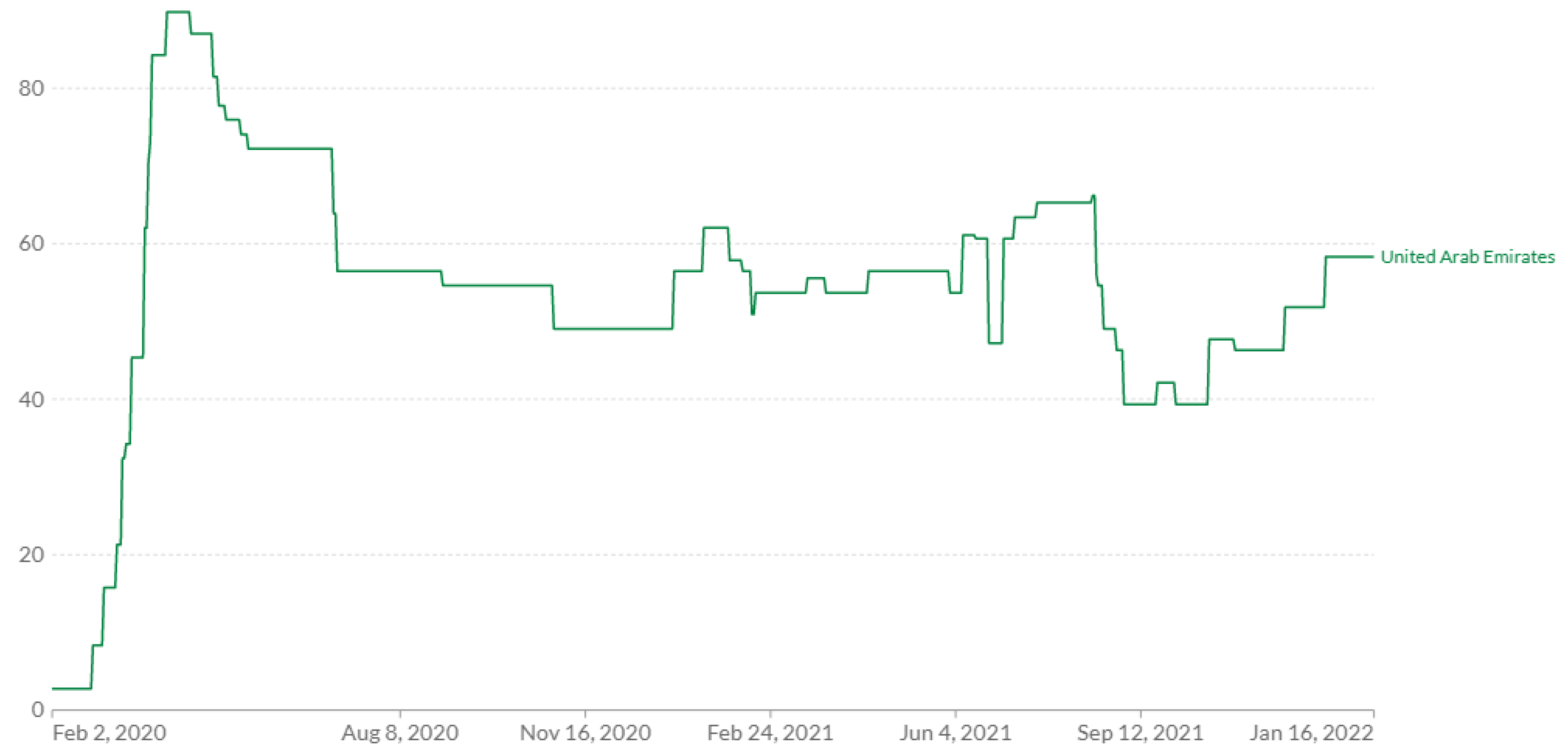

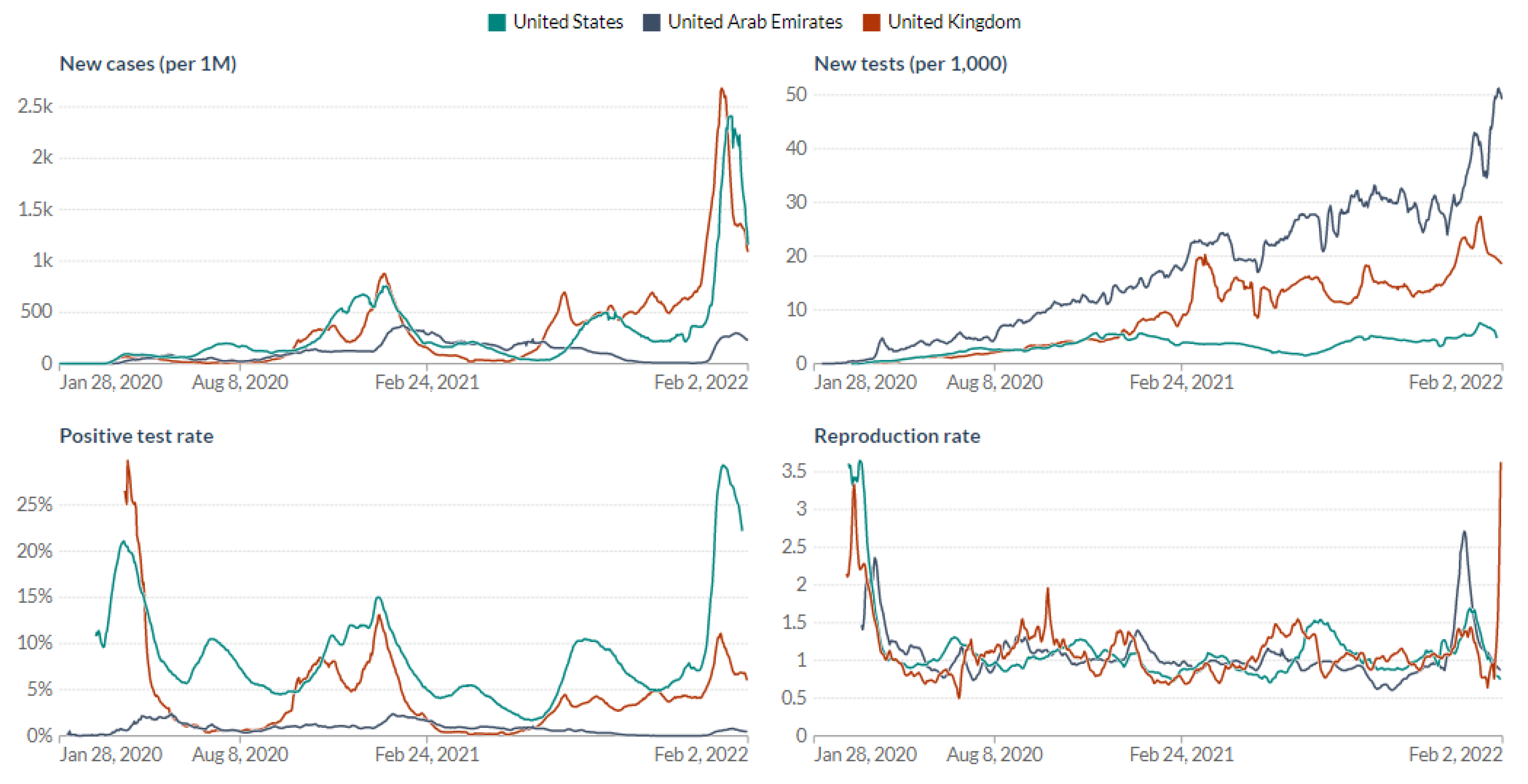

- Our World in Data. Policy responses to the coronavirus pandemic. University of Oxford, 2020. Available online: https://www.ourworldindata.org/policy-responses-covid (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Passetti, E.; Battaglia, M.; Bianchi, L.; Annesi, N. Coping with the COVID-19 pandemic: The technical, moral and facilitating role of management control. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

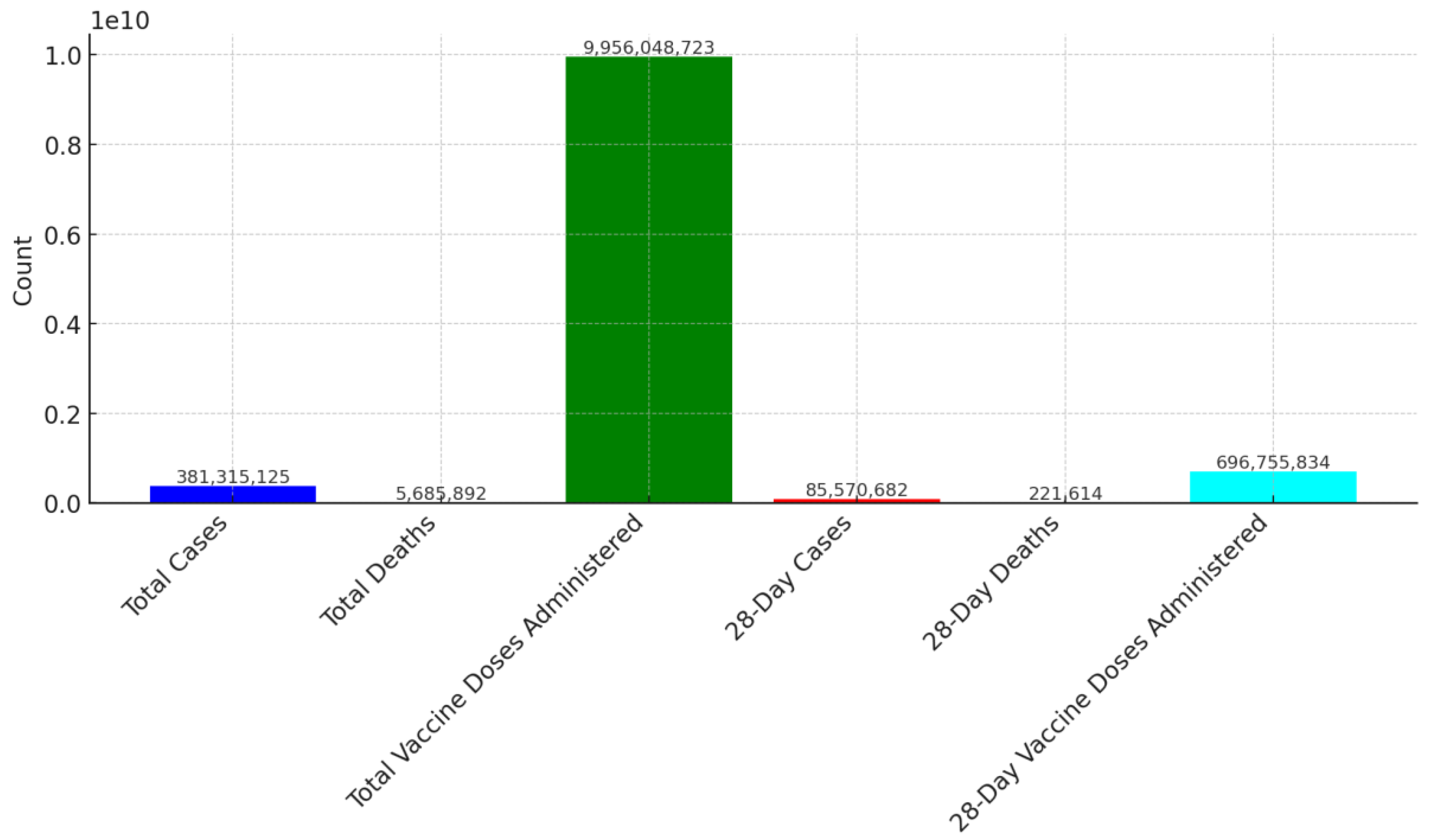

- Reuters. COVID-19 Tracker. Reuters, 2022. Available online: https://graphics.reuters.com/world-coronavirus-tracker-and-maps/countries-and-territories/united-arab-emirates/ (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. Sage Publications Ltd., 2012.

- Sciulli, N. Weathering the storm: Accountability implications for flood relief and recovery from a local government perspective. Financial Accountability & Management. [CrossRef]

- Sian, S.; Smyth, S. Supreme emergencies and public accountability: The case of procurement in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal. [CrossRef]

- Solomon, J.F. Corporate Governance and Accountability, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2021.

- TAG911. Covid-19: Updates from UAE Government Media Briefing. TAG911, 2021. Available online: https://www.tag911.ae/news/local-news/covid-19-updates-from-uaegovernment-media- (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- United Arab Emirates. Vaccines against COVID-19 in the UAE. UAE Government, 2021. Available online: https://u.ae/en/information-and-services/justice-safety-and-the-law/handling-the-covid-19-outbreak/vaccines-against-covid-19-in-the-uae (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- UAE Health Data Hub. Annual Report. UAE Health Data Hub, 2023.

- UAE Ministry of Health and Prevention. Annual Report on COVID-19 Response. UAE Ministry of Health and Prevention, 2020.

- UAE Ministry of Health and Prevention. COVID-19 Portal. UAE Ministry of Health and Prevention, 2023. Available online: https://www.mohap.gov.ae/ (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- UAE Ministry of Health and Prevention. Strategic Health Initiatives. UAE Ministry of Health and Prevention, 2024.

- UAE National Vaccination Program. Strategic Plan Document. UAE National Vaccination Program, 2020.

- WAM. Referral of 129 quarantine violators to the Attorney General (In Arabic). WAM, 2020. Available online: https://www.wam.ae/ar/details/1395302835874 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- World Economic Forum. Insight Report: The Global Competitiveness Report 2019. World Economic Forum, 2019. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2019.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Dashboard. World Health Organization, 2024. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 24 January 2023).

| Measures taken | Timeline |

|---|---|

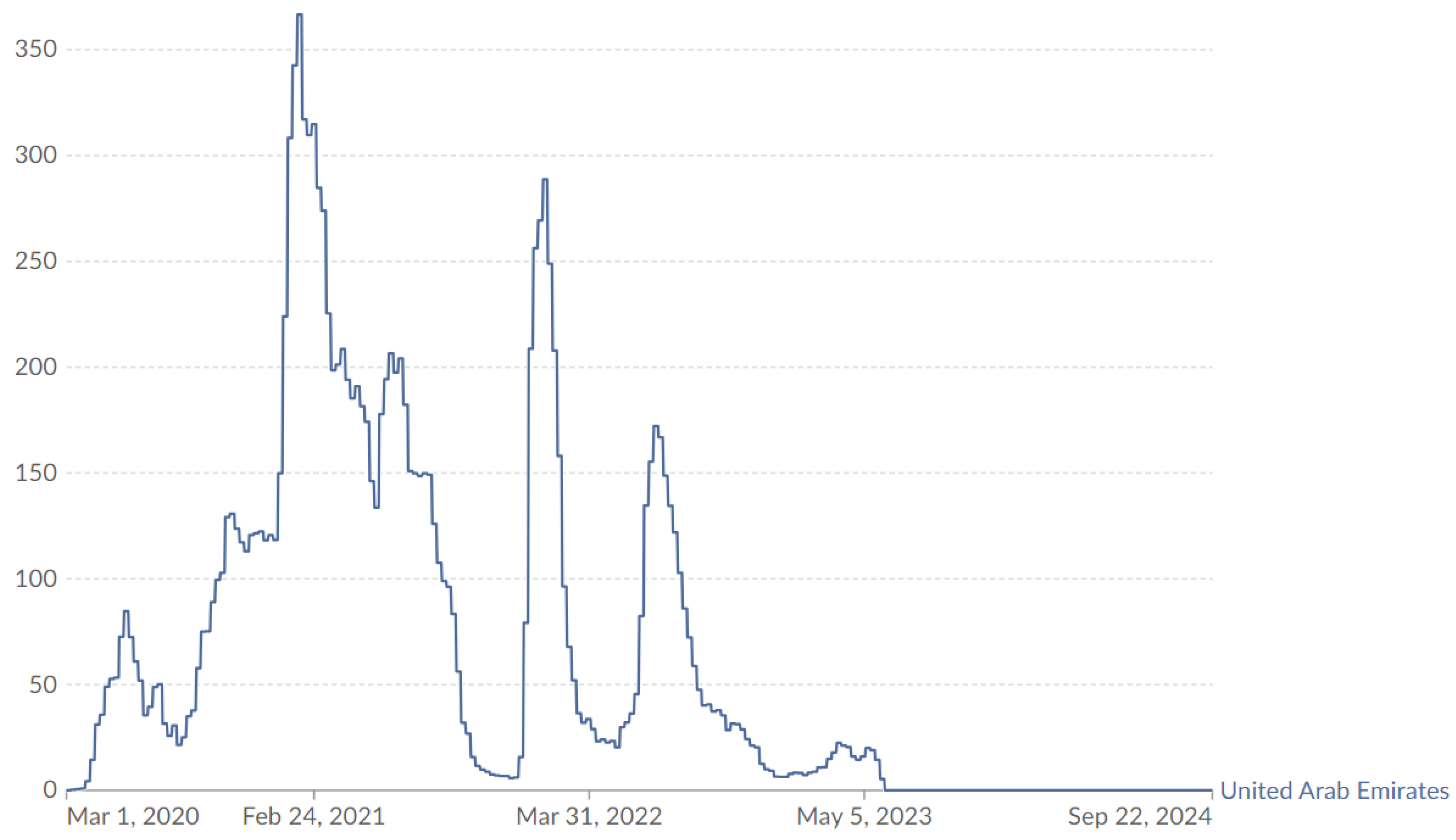

| First recorded case | January 29, 2020 |

| First recorded death | March 21, 2020 |

| Confirmed cases as of February 28, 2021 | 391,524 |

| Rate of infection per million people | 295 |

| Confirmed deaths as of February 28, 2021 | 1,221 |

| Case fatality rate | 0.31% |

| Closure of schools and universities | March 8, 2020 |

| Lockdown introduced | March 22, 2020 |

| Cancellation of public events and gatherings | March 22, 2020 |

| started educating students at schools and higher education institutes through distance learning | March 22, 2020 |

| International and domestic travel restrictions | March 23, 2020 |

| Gatherings during the first phase of lockdown Maximum | 30% |

| Stay-at-home restrictions | April 4, 2020 |

| SEHA opens 13 additional drive-through COVID-19 testing centres | April 9, 2020 |

| MOHAP hosts the world’s first Phase III clinical trials of an inactivated vaccine to combat COVID-19 | June16, 2020 |

| Reopening for international tourists | July 7, 2020 |

| UAE authorises emergency use of COVID-19 vaccine for frontline health workers | September 16, 2020 |

| Vaccination launched for the residents to get free vaccination | December 14, 2020 |

| School reopening | February 14, 2021 |

| Social distancing | 2.5m |

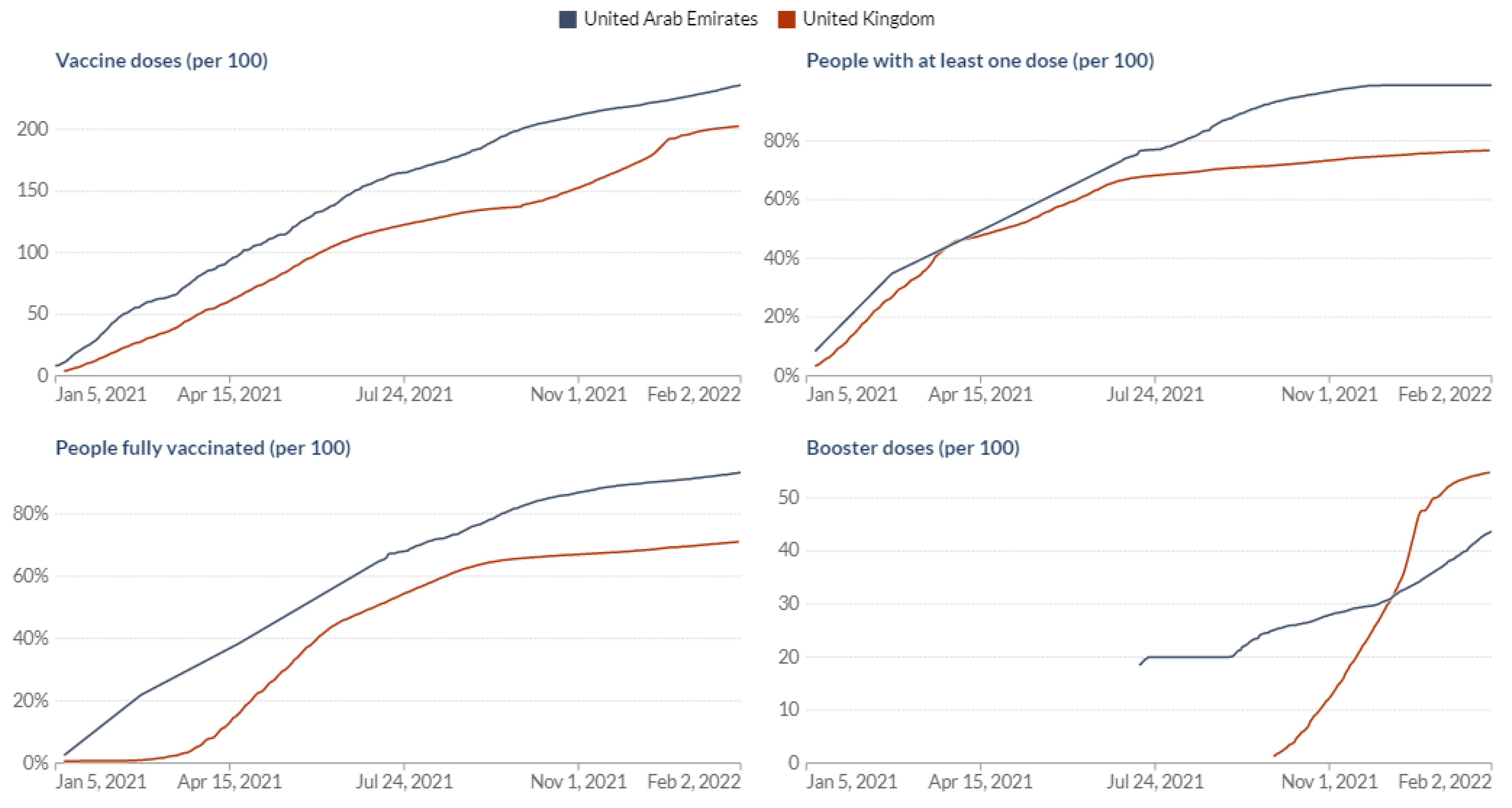

| More than 50 % of the UAE population is vaccinated | March 17, 2021 |

| Reopening of schools with total capacity | August 29, 2021 |

| - COVID-19 infections down by 62% compared to January 2021- More than 76% of the population is fully vaccinated | August 31, 2021 |

| Al Hosn app gets global recognition as ‘App of the Year’ in the COVID-19 response category. | February 1, 2022 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).