1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic faced worldwide since 2020 has led to an unprecedented health-disaster situation. Owing to this disaster situation, which lasted for over three years, most countries in the world have paid serious social and economic costs [

1]. Additionally, COVID-19 has become an opportunity to raise public interest in the role of government in disaster management due to the pandemic. In particular, the governments of each country have tried to block the spread of infectious diseases through non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs). Some studies have argued that these policy interventions have had some effects, although they vary by country [

2,

3,

4].

1

The main measures taken by governments have mainly focused on NPIs, aiming to alleviate the spread of infectious diseases by directly intervening in people’s daily life and economic activities and restricting behavior. However, unlike its original purpose of preventing the spread of infectious diseases, this government’s policy response also caused unintended consequences that severely damaged the burden of the national economy and people’s income level [

5].

In 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared the end of COVID-19 [

6]. Nevertheless, the COVID-19 pandemic has sparked the need for appropriate government response in health-disaster situations worldwide. From this point of view, research is being conducted to retrospectively evaluate the effectiveness of the government's policy response in the pandemic situation [

5].

This study extends these preceding studies. In other words, this study analyzes the effectiveness of the government's policy response to COVID-19. In particular, it focuses on NPIs among government’s policy responses.

The questions of this study are as follows. First, did the government's non-pharmaceutical response to COVID-19 have a positive effect? Second, do the effects between various government measures differ? Finally, is the effect of government response to infectious diseases strengthened by people's trust in the government?

This study conducts a comparative analysis between countries in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Scholars' concern in the effectiveness of government policy has continued, but owing to differences in policy priorities and policy targets by country, conducting a comparative analysis between countries has been difficult [

8]. However, the pandemic period provides an opportunity for a comparative analysis between countries on the effectiveness of the same policy in that it highlights a common policy priority of overcoming the pandemic worldwide [

9].

Experts have pointed to the possibility of future infectious diseases even after the COVID-19 pandemic [

10,

11]. Understanding the effects of the government's various NPIs during a health disaster is expected to contribute to the government's search for appropriate policy responses in similar health-disaster situations in the future.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Types of Policy Response in COVID-19 Pandemic

The government's policy prescriptions for responding to COVID-19 pandemic have been diverse. The response can be divided into two main categories: regulation and support. The various government responses suggested in previous studies comprise specific measures within these two categories.

Hale et al. [

12] divided the government's actions against infectious diseases into four categories - “Containment and closure,” “Economic response,” “Health systems,” and “Miscellaneous” - with 20 specific measures presented for each category. Eight measures are included in “Containment and closure,” including “School closing,” “Workplace closing,” and “Cancel public events.” “Economic response” includes economic support measures such as “Income support” and “Debt/Contact relievers for households.” “Health systems” includes seven measures, such as “Public information campaign,” “Testing policy,” and “Contact tracing.” Their classification can also be divided into “Economic response” as a support policy, and “Containment and closure” as a deterrent policy. In the case of “Health systems”, various policy types such as regulation, support, and medical measures (e.g., “Vaccination Policy”) are mixed.

They presented several indexes by combining specific measures included in three categories. Particularly, the Stringency Index focusing on “Containment and closure” was proposed. Additionally, the “Containment and Health Index (CHI),” which comprises “Containment and closure” and “health systems,” and the “governance response index (GRI),” which is the broadest government response index, are additionally presented by adding an economic support index to CHI.

A number of studies have revealed that the government's response to COVID-19 has focused on containment policies compared to support policies [

13]. The containment policy centered on social distance has shown the effect of weakening the spread of the initial pandemic despite the costs it incurs, but as the pandemic has dragged on, the socioeconomic costs caused by containment policies have raised the need for the government to adjust the intensity of NPIs. Nevertheless, containment policies have become an important policy tool to mitigate health disasters during the pandemic. Moreover, similar measures have been adopted in most countries of the world during the pandemic's spread [

13].

Prior to the declaration of the COVID-19 virus as a pandemic by the World Health Organization [

14], WHO recommended campaign-level responses such as hand hygiene and respiratory etiquettes and considered measures such as restrictions on social gatherings, school, and workplace classes and quantifying asymptomatic contacts depending on the severity of the virus’ spread in each country. However, after the COVID-19 pandemic declaration , social distancing and movement control measures were recommended at the national level. These include specific measures such as prohibiting gatherings, closing schools and workplaces, and reducing public transportation.The OECD [

15] evaluated government measures conducted in major countries and included “lockdown and restrictions” as NPIs. According to the OECD, evaluations focused on measures to control the movement of people in 10 major countries, including “school restrictions,” “bans on public collections,” and “travel restrictions.”

Additionally, Rahmouni [

16] presented five major ways for the government to respond to the pandemic. These include movement restrictions, social distancing, state closures, public health prescriptions, and social and economic prescriptions. In particular, as the government's NPIs, movement restrictions, social distancing, and state closures are representative measures to curb virus transmission. Toshkov et al. [

17] also categorized the government's response to the pandemic into three main types. School closure is a measure that forcibly closes most elementary and secondary schools. National lockdown means widespread restrictions on movement of citizens, including prohibition of going out, restrictions on the business of collective facilities, prohibition of travel, and entry through border blockade. Finally, by declaring a national emergency, the government’s actions institutionalize the temporary strengthening of the authority of the administration or related organizations. Excluding the declaration of a national emergency, the government's direct intervention in the lives of its people can be divided into school and state closures.Previous studies analyzing the effectiveness of government responses have also included similar government responses in the analysis target. In this way, the government's measures to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic specifically suggested similar measures, such as prohibiting gatherings, restricting business, restricting movement, closing schools and workplaces, and national closures, focusing on social distancing.

Conversely, the individual measures listed above are summarized and divided into two conceptual categories; mitigation and suppression strategies [

18,

19]. The mitigation strategies aim not to completely block transmission but to slow the spread and become immune, while suppression strategies aim to reduce the number of cases by completely eliminating transmission [

18]. Therefore, these are government measures with stronger suppression strategies than mitigation ones. These suppression strategies are controversial in that they limit individual freedom [

20]. For this reason, when the government's measures included in the suppression strategies are effective in responding to pandemic, this can lead to people's compliance.

By applying the concepts proposed by Ferguson et al. [

18] and González-Bustamante [

19], this study divides the government's NPIs to cope with COVID-19 into mitigation and suppression strategies, and attempts an analysis based on these two concepts.

2.2. The Effectiveness of Government Responses

The purpose of government response during the COVID-19 pandemic was to mitigate the spread of the pandemic and prevent infection. Additionally, the results of these government responses include decreases in the numbers of confirmed cases and deaths by COVID-19 infection. Studies analyzing the effectiveness of government responses to the pandemic have used the increase or decrease in the number of new cases or deaths caused by infection as an indicator of the measures’ effectiveness [

1,

5]. They have also agreed to regard infected people or deaths as the effect of the government's COVID-19 measures, but indicated that various indicators, such as the number of infections, deaths from COVID-19, and mortality from COVID-19, need to be considered in the measurement [

21].

In addition to these outcome indicators, people’s degree of mobility has sometimes been used as the effect of government response [

5,

13]. The decrease in movement has been regarded as the degree of people's policy compliance with suppression measures such as social distancing and an effect of the policy as an outcome variable.

Meanwhile, Dergiades et al. [

1] emphasized intensity and speed as the effects of government measures. They presented the results of empirical analysis, by which the strong measures at an early stage are most effective in reducing the number of new cases and deaths. However, Agyapon-Ntra & McSharry [

5] argued that mask-wearing is considerably more cost-effective than measures such as school closures and movement restrictions among government responses. Additionally, the influence of overseas travel control and public information campaigns is insignificant. They analyzed the relationship between the intensity of government measures and people’s mobility. The increase in the number of infected people and deaths in the early stages of the pandemic strengthened the intensity of government intervention, and as a result, people’s mobility decreased, resulting in high compliance with government measures. However, as the pandemic continued for a long time, the degree of compliance with measures weakened as people’s mobility increased owing to public fatigue, economic damage, and vaccination. Mitze et al. [

7] argues that as a result of comparing areas where mask wearing was forced in Germany with areas that were not, the number of infection cases tended to decrease in areas where mask wearing was enforced.

Furthermore, a study by Zaki et al. [

21] suggested that the intensity of government response has a direct positive effect on the reduction of mortality caused by COVID-19. Additionally, certain measures are more effective than others [

1,

9]. Degiades et al. [

1] argued that school closures are highly effective among the government's various measures, while Ji et al. [

9] suggested that compulsory masking is a cost-effective method.

As described above, studies analyzing the effectiveness of government responses to COVID-19 have presented various results. While some have claimed that the government's various measures have mitigated the spread of infection, others have highlighted differences by period. Moreover, some studies have pointed to differences in the effectiveness of specific measures. These differences may result from differences in the measures’ characteristics and may also vary depending on which effectiveness index is used. In other words, judging the effectiveness of government response in health disasters implies complexity and suggests the need to carefully consider differences by response measures and period.

2.3. Government Trust and Pandemic Performance

Trust in the government in risk situations leads to stronger compliance with government policies. Government or political trust acts as an important factor that positively affects acceptance of government policies and reduction of risk perception [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

In the COVID-19 period, which can be called a health disaster, the effect of the government's policy response was not due to the role of the government alone, but rather, it was the result of cooperation through interactions between government and people [

28]. This perspective emphasizes political trust as an important variable in explaining differences in pandemic performance between countries. The higher the political trust, the stronger the participation and compliance with government policies, leading to higher performance.

The “coproduction” perspective to explain the relationship between trust and the policies’ effectiveness argues that the government’s effectiveness depends not only on the government’s actions but also on the people’s acceptance and support [

9]. Additionally, the relationship between the government’s actions and people’s acceptance and support exists on the basis of mutual trust. In other words, trust in the government becomes an important factor in linking the government’s actions and people’s support.

Trust in the government is more important in disaster situations such as the pandemic. A review of previous studies found that trust in related organizations in a pandemic situation positively affects the public's willingness to accept the actions recommended by the government [

24]. Moreover, trust in government has an important influence on the government's policy style and response [

26]. Health-disaster situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic involve high uncertainty, and verifying the effectiveness of government measures is difficult in that they require rapid government responses. In this situation, trust in the government is important to induce people to comply with the government's policy response. Therefore, in times of disaster crisis, government trust plays a more important role than it does in normal times. In particular, trust in the government can be a key factor in the effectiveness of disaster response in that health disasters cause direct and high sensitivity to people's lives. Previous studies have also analyzed the relationship between the stringency and timing of government responses as NPIs to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and the results of government responses [

7,

18,

29,

30].

2 In particular, the government's policy responses are socially and behaviorally moderated [

21,

29]. These arguments imply that the effectiveness of government responses may vary depending on the policy environment.

Additionally, a positive relationship exists between compliance with government measures and trust [

31,

32]. Nevertheless, trust in the government is not necessarily positive for compliance with government policies depending on the environment in the rapidly increasing wicked crisis situation [

21].

Ji et al. [

9] verified whether the effect of government measures on COVID-19 was further strengthened by government trust. Their research showed that the degree of mask-wearing enforcement by the government had a positive effect on increasing the proportion of actual mask-wearing. Additionally, the degree of coercion in mask wearing showed the effect of further increasing the rate of mask wearing by interacting with a high level of trust in government. These results imply that the level of government trust has a moderating effect on the relationship between the strength of government measures in response to COVID-19 and the actual effects. This is because the government's responses during the health disaster are short-term measures, but trust in the government is an accumulated result in the long term. This means that trust in government can be an environmental condition for successfully implementing of government responses.

However, in the study of Zaki et al. [

21], although government trust directly affected the effectiveness of government response, the moderating effect of government trust between government response measures and policy effects measured by mortality from COVID-19 could not be verified. Rather, the results were contrary to the assumption that government trust would further increase the effectiveness of government countermeasures. Zaki et al. [

21] interpreted that in countries with high trust in the government, people's autonomy is high; thus, they are more likely to feel rejected and not comply with government measures that suppress freedom. People’s low compliance with government response is a factor that lowers the measures’ effectiveness. However, the research results of Zaki et al. [

21] have a limitation in that they did not distinguish the intensity of government response by measures. Therefore, for their results to be more persuasive, they must be analyzed separately from government response measures. The results of the abovementioned studies show that trust in the government is an important factor in determining the effectiveness of measures.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measurement

The government has implemented various measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which have been evaluated through various approaches. Many studies analyzing the effectiveness of these measures have employed the "Stringency Index" as an indicator to assess the intensity of government responses [

5,

13,

21,

30]. The "Stringency Index" is a composite measure derived from the "Containment and Closure" indicators included in the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) [

13]. Similarly, Fetzer et al. [

33] calculated the stringency index by incorporating measures such as school closures, workplace closures, cancellation of public events, public transportation closures, public information campaigns, and restrictions on internal movement. This approach synthesized diverse containment measures into a single composite index to assess the overall intensity and extent of government responses.

Conversely, some studies have focused exclusively on specific, relatively stringent individual measures, such as school closures, workplace closures, gathering restrictions, and stay-at-home orders [

9]. Adolph et al. [

34] similarly categorized government responses into measures focused on closures and isolation, including restrictions on large gatherings, school closures, restaurant closures, workplace closures, and stay-at-home orders. These studies have primarily encompassed responses with relatively high intensity. Additionally, some research has analyzed the effectiveness of less stringent measures, such as mandatory mask-wearing [

7]. This study aims to address both stringent measures and mitigation measures.

Despite variations in scope and intensity, government responses to the COVID-19 pandemic largely fall under the category of NPIs, predominantly characterized by regulatory and containment policies. These measures have generally been assessed using two main approaches. First, many studies have adopted the "Stringency Index," which focuses primarily on "containment and closure" measures, offering the advantage of evaluating the overall intensity of government responses. Second, some studies have measured individual policy responses, which allows to analyze the effectiveness and intensity differences among specific measures. While the "Stringency Index" provides a comprehensive view of the overall response intensity, it does not capture the unique characteristics and effects of individual measures. Conversely, focusing selectively on certain measures may overlook the diversity of government responses.

Government measures include both relatively low-intensity strategies, such as promoting mask-wearing, handwashing, and public awareness campaigns, as well as high-intensity strategies, such as social distancing, lockdowns, and mobility restrictions that impose significant limitations on daily life. Limited research has been conducted to comprehensively consider such diverse response strategies at an intermediate level of analysis. Consequently, this study adopts the concepts of suppression strategies and mitigation strategies introduced by Ferguson et al. [

18] and González-Bustamante [

19]. Suppression strategies aim to eliminate infections and include NPIs such as social distancing, school closures, workplace closures, and restrictions on public transport, meetings, and domestic and international travel [

19]. Mitigation strategies, while less intense, aim to slow the rate of infection, with policies such as isolating confirmed cases being representative examples. This study intends to categorize and measure diverse government responses based on these two conceptual frameworks. By doing so, it considers both the differences in their intensity among individual responses and the overall degree of government intervention as a whole.

To measure the effectiveness of government responses, previous studies have utilized two types of metrics. The first includes indicators such as the number of COVID-19 confirmed cases, mortality, and new cases or deaths caused by the virus [

1,

5,

7,

9,

18,

19,

21,

29]. These indicators are often interpreted as the outcomes of government responses, and most studies have utilized such measures. The second type measures the degree of population mobility, which reflects the effectiveness of NPIs. Hale et al. [

13] and Agyapon-Ntra & McSharry [

5] evaluated how government interventions, particularly social distancing measures, limited population movement to curb the spread of the virus. While case and death indicators represent the outcomes of government responses, mobility reduction is considered a direct result. This study employs the number of total deaths and new deaths due to the COVID-19 as metrics; these have been widely used in previous studies.

Regarding the measurement of trust in government, traditional methods have involved surveys conducted at the individual level [

9]. These surveys typically include questions assessing trust in national institutions or political systems (e.g., central government, local government, legislature, judiciary). For cross-national comparisons, aggregate measures at the national level are derived from individual survey data. The World Value Survey, for instance, measures confidence in government across approximately 190 countries [

35]. Similarly, Zaki et al. [

21] utilized Eurobarometer datasets aggregated at the national level. Following this precedent, this study uses aggregated survey data, initially measured at the individual level, to measure trust in government at the national level.

3.2. Data and Methods

The dependent variables of this study are total deaths per million and new deaths per million, which were derived from “Our World in Data” [

36]. The original data provides daily figures for total and new deaths. For cross-country comparisons on a yearly basis (ranging from 2020 to 2022), the data were converted to an annual scale. Specifically, the original data contains the counts for total deaths presented as cumulative figures on an annual basis. To obtain the total death values for each year, we utilized the cumulative total deaths count recorded on December 31. Subsequently, we calculated the total deaths per million by dividing the total number of COVID-19 deaths for each year by the population and multiplying the result by one million. For new deaths, we constructed the annual data by summing the daily counts of new deaths over 365 days. We also calculated new deaths per million with the same method used for the total deaths per million. In essence, both dependent variables–total deaths per million and new deaths per million–were created to represent the number of deaths or new deaths per one million population in each country.

The main independent variables are suppression and mitigation measures. We utilized data on eight different COVID-19 policy measures extracted from "Containment and Closure" indicators included in the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) (Hale et al., 2020) to construct two composite indices: suppression and mitigation measures. The eight types of government measures in response to the COVID-19, utilized in this study, include facial coverings (0-4 scale), restrictions on internal movement (0-2 scale), international travel controls (0-4 scale), public information campaigns (0-2 scale), cancel public events (0-2 scale), restrictions on gatherings (0-4 scale), stay-at-home requirements (0-3 scale), and workplace closures (0-3 scale), among others. For each indicator, a higher score on the scale represents a greater level of policy implementation. Two composite indices, suppression and mitigation measures, were constructed based on the results of factor analysis, using principal component analysis of these eight response indicators (see Appendix Table A1). Specifically, the first component, or suppression measures encompasses six different indicators: (1) restrictions on internal movement, (2) international travel controls, (3) cancel public events, (4) restrictions on gatherings, (5) stay-at-home requirements, and (6) workplace closures. The other component, mitigation measures, includes facial coverings and public information campaigns. Both suppression and mitigation measures were created with factor-analytic weighted average scores, using factor loadings from the principal component factor analysis.

Additionally, as a key variable, trust in the government used data provided by the OECD was measured as the proportion of the population aged 15 or older who trusted the government [

37]. All other control variables–population over 65 years old, GDP per capita, hospital beds per thousand, and Human Development Index (HDI)–were derived from the World Bank Indicators [

38].

To estimate the relationship between various policy measures and COVID-19 related deaths, this study employed panel data analysis using random effects, since only three-year data, ranging from 2020 to 2022, were utilized for the analysis owing to the limited period of COVID-19 pandemic. Huber-White robust standard errors were estimated and clustered at the country level in the analysis model.

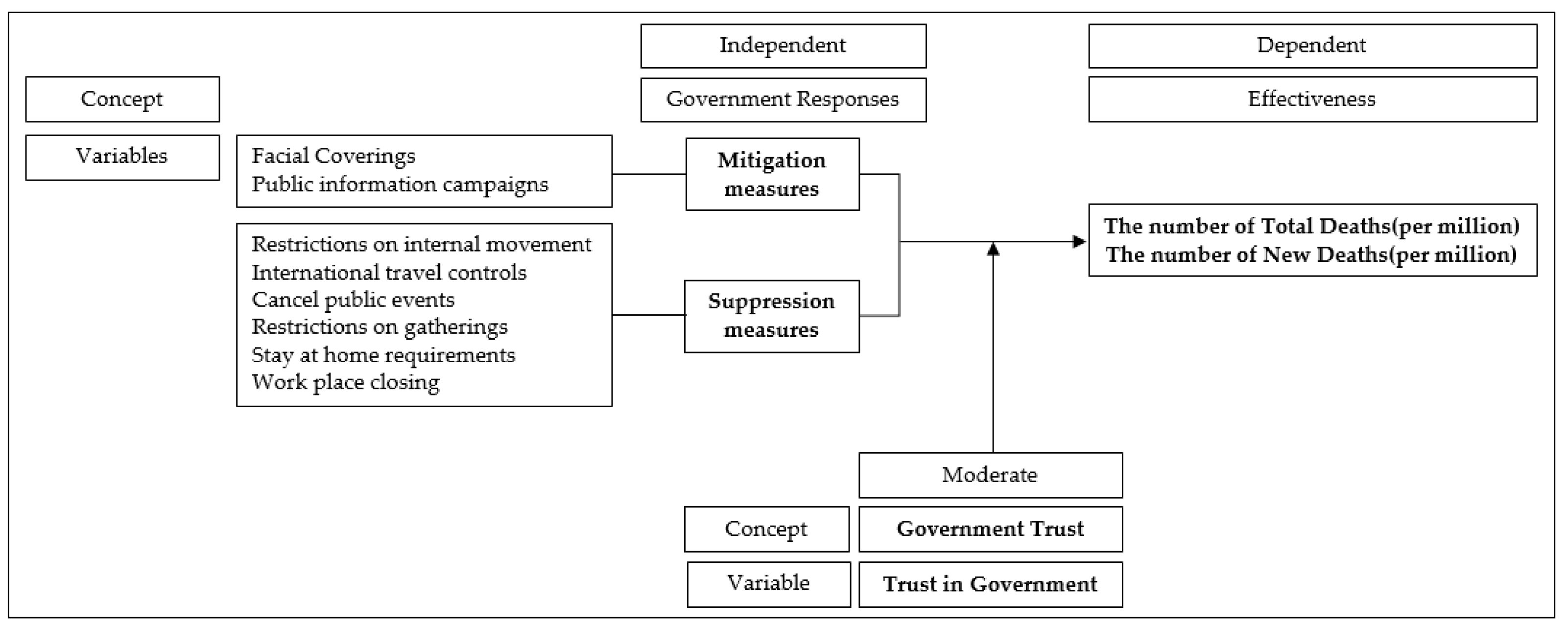

Figure 1 presents an analysis framework for this study.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

The descriptive statistics summarized in

Table 1 offer valuable insights into the key variables examined in the study. The total number of deaths reported has a mean of 1,487 (SD = 1,133.79), which indicates substantial variability among OECD countries. Similarly, new deaths exhibit a mean of 746(SD = 556.78), which also highlights differences in the distribution of newly reported fatalities.

As for the main independent variables, suppression and mitigation measures represent government responses. In this study, eight individual measures were divided into Suppression and Mitigation [

18,

19] through factor analysis. Descriptive statistical analysis was conducted after the sum of scores of specific individual measures included in each of suppression and mitigation was obtained. Suppression measures range from 0 to 18, and mitigation range from 0 to 6. As a result of the analysis, suppression measures have an average value of 7.23 (SD=4.06), with a minimum value of 0.18 and maximum value of 15.04. Mitigation measures have an average of 3.84 (SD=0.87) with a maximum value of 1.74 and a minimum value of 6.00.

These values suggest that the application of these measures varies significantly across countries. Trust in government displays a mean score of 48.38 (SD = 15.75), reflecting moderate variability and providing a baseline understanding of public confidence levels in governmental institutions.

Additionally, as for control variables, economic development, measured by GDP per capita, averages $38,420.32 (SD = 15,373.47). The aging population rate averages 16.98% (SD = 4.35), while the number of hospital beds per thousand people averages 4.47 (SD = 2.62), suggesting disparities in healthcare infrastructure availability. Finally, the human development index (HDI) exhibits a mean of 0.90 (SD = 0.05), which demonstrates a relatively high and consistent level of human development in OECD countries.

Table 2 shows the average of total deaths (per million), new deaths, suppression, and mitigation measures by year. The cumulative number of deaths is increasing over time, but the number of new deaths has decreased from the highest in 2021. In other words, 2021 was the period when the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic reached its peak. In 2022, the new deaths in OECD countries were 627 on average, despite the fact that the spread of the pandemic was weakening. This suggests that deaths from COVID-19 may continue to occur in the future, and the government's continued response is necessary.

Table 3 analyzes the average difference in the values of the dependent variables by classifying groups with below and above average of the independent variable through a t-test. As a result of the analysis, the group with high trust in the government has lower average total deaths and new deaths compare to the group with low trust in the government, and both are statistically significant. These results show that trust in the government can be an important factor in reducing the number of deaths from COVID-19. Directly explaining the difference in the number of deaths depending on the degree of trust in the government has limits, but if the government trusts the policy, the possibility of compliance is high, which suggests the possibility of a decrease in the number of deaths.

The difference in the number of deaths between the above- and below-average groups of suppression measures was found to be statistically significant. The number of total deaths (per million) is lower in the group with strong suppression measures, while the number of new deaths (per million) is higher in this group. Suppression measures with relatively strong intensity show that they can induce a decrease in the number of total deaths.

Finally, the mitigation measures show that the below-average group has lower total deaths and new deaths compare to the above-average group. In other words, the mitigation measures composed of weak-intensity measures show the results that the effects of the measures are not clearly shown. Rather, mitigation measures alone can have an adverse effect on preventing the spread of the pandemic. These results suggest that mitigation methods need to be implemented in connection with other measures rather than independently.

4.2. Regression Analysis

This study investigates how various policy measures are associated with the numbers of total and new deaths in a pandemic context. The regression analysis results are presented in

Table 4.

Columns 1 and 2 show that the regression estimates for suppression measures, such as lockdowns (β= -458.0555 and -641.899, respectively) are negative and statistically significant at least at p<0.05. The estimated results from column 1 indicate that a one-unit increase in implementing suppression measures corresponds to a reduction of approximately 458 deaths per mission, thereby suggesting the critical role in reducing the death rates in pandemic responses. Columns 3 and 4 demonstrate that mitigation measures such as mask mandates and social distancing are positively associated with total deaths per million (β= 487.623 and 1,075.580, respectively), which is statistically significant at p<0.001. The estimated coefficient of mitigation measures suggests that a one-unit increase in these measures likely correlates with an increase of approximately 487 deaths per million, which could reflect the possibility of delayed implementation of mitigation measures in some regions. Thus, while these measures are essential, their effectiveness may depend on its implementation timing and interaction with other factors.

Third, the estimates for trust in government (β= -16.456 and -19.566, respectively) are negative and statistically significant at least at p<0.01. Column 1 indicates that for every one-unit increase in trust, total deaths per million decrease by approximately 16. This underscores the importance of public confidence in government during health crises, likely owing to higher compliance with policies and improved communication effectiveness. Additionally, as presented in column 2, trust in government emerges as a crucial moderating variable. The results show that countries with higher trust levels are consistently associated with reduced deaths compared to those with lower trust levels. Interaction effects in the model provide additional insights into the dynamic between policy measures and public trust in government. Specifically, the coefficient for the interaction between suppression measures and trust in government (β= 3.583) is positive and not statistically significant at p<0.05. This suggests that suppression measures do not strongly depend on public trust in government for their effectiveness.

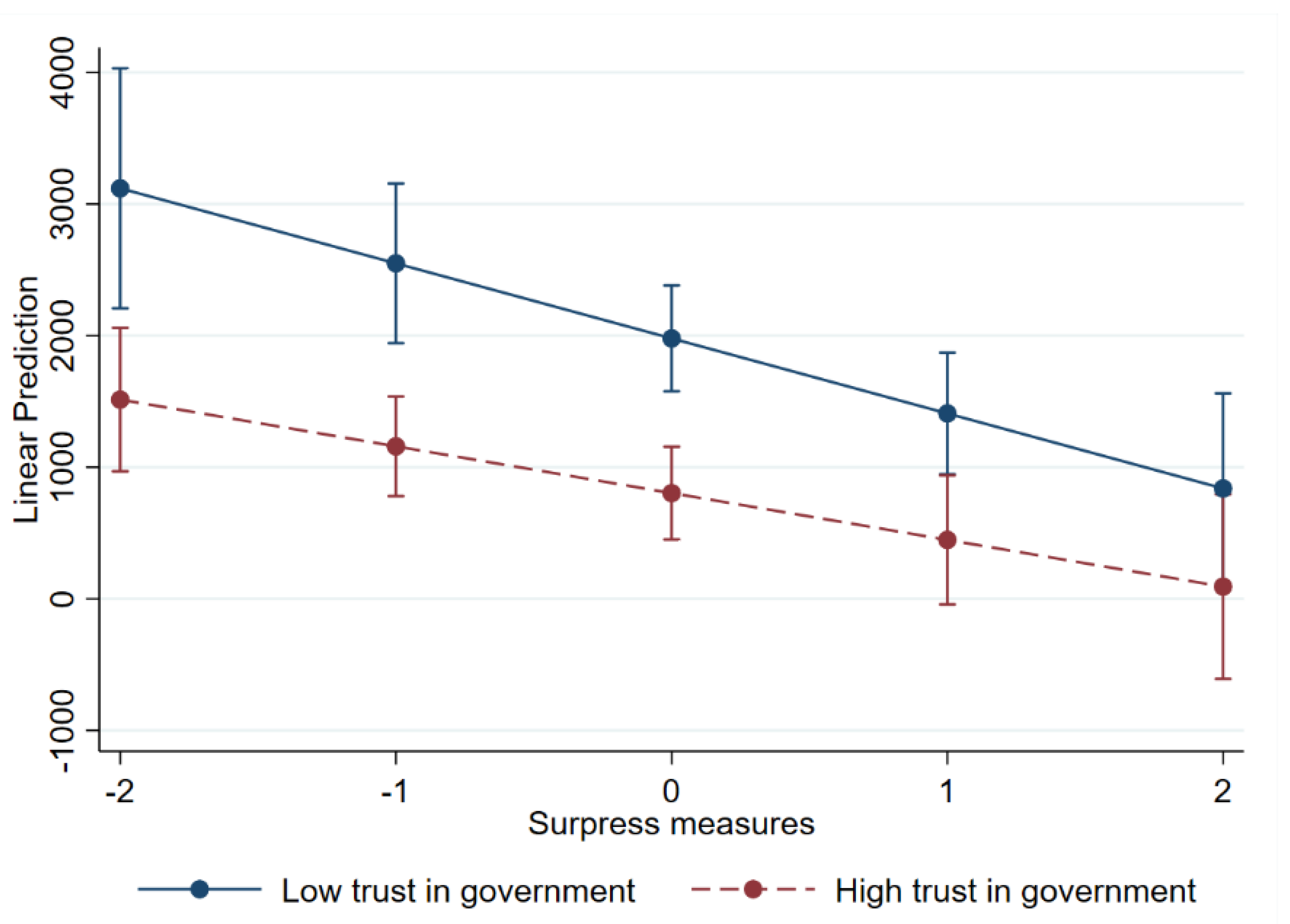

Figure 2 illustrates how trust in government influences the effectiveness of suppression measures in reducing total deaths per million. It shows a slight negative trend, suggesting that while suppression measures alone are effective at reducing deaths, the effectiveness is not significantly amplified by varying levels of trust in government, especially when stronger suppression measures are implemented.

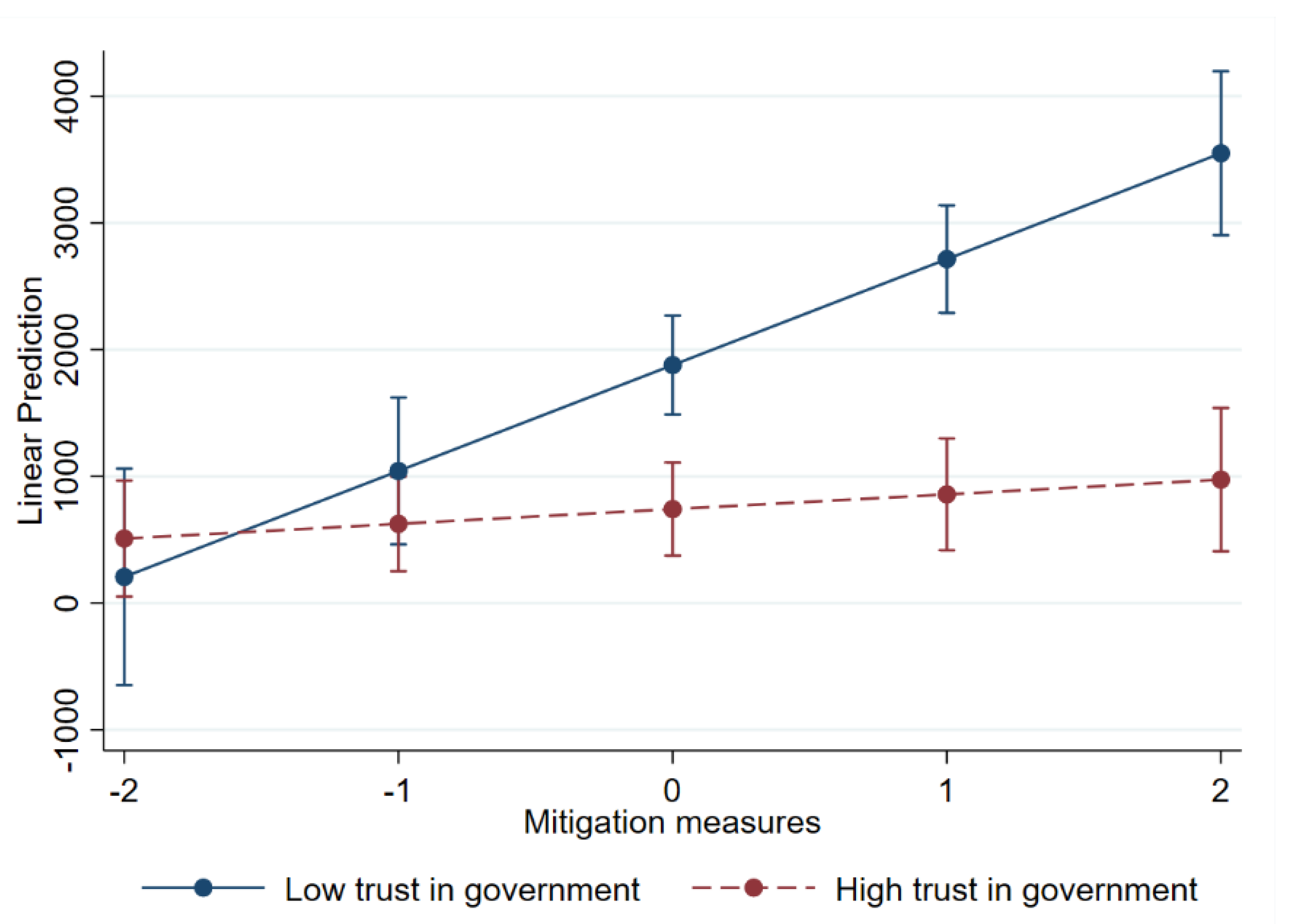

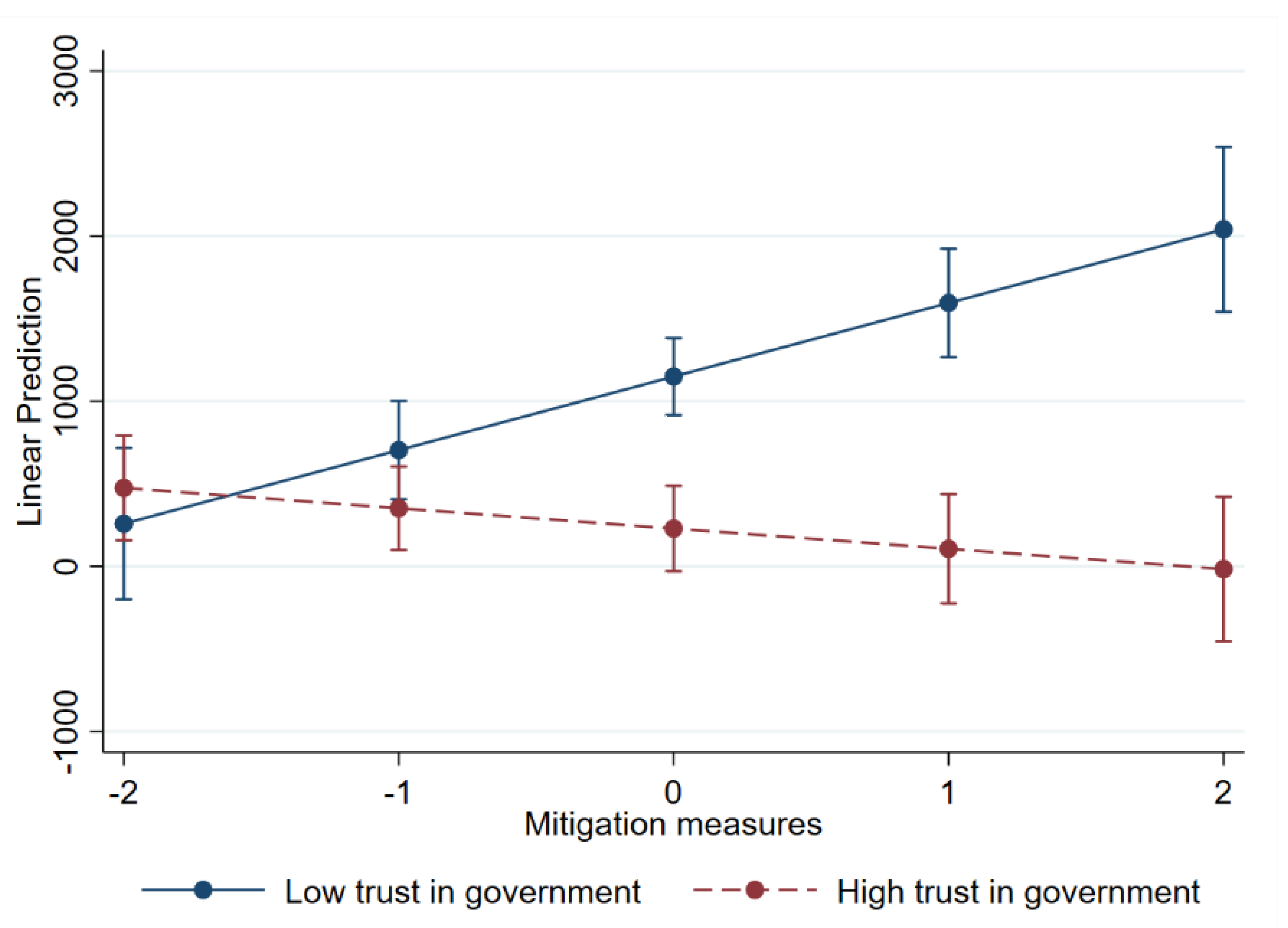

Conversely, the interaction term for mitigation measures and trust in government (β= -11.991) is negative and statistically significant at p<0.01, which indicates that higher trust in government weakens the positive relationship between mitigation measures and total deaths per million.

Figure 3 graphically presents the interaction between mitigation measures and trust in government. It indicates that countries with high trust levels had lower mortality than those with low trust levels, when mitigation measures (higher than zero) were taken. Where trust in government is especially low, mitigation measures may not be effective but rather more related to higher mortality. This underscores the importance of public trust in government and their compliance for optimizing mitigation strategies during a health crisis.

Additionally, the coefficients for the aging population rate (β= 89.682 and 85.662) are positive and significant at least at p<0.01, reflecting the heightened vulnerability of older populations. Conversely, hospital beds per thousand and economic development show no statistical significance, which suggests that resource availability alone is insufficient without effective governance and strategic planning. Overall, these findings emphasize the interplay of policy, public trust, and socioeconomic factors in shaping public health outcomes during crises. To sum up, suppression measures are highly effective in reducing deaths, while trust in government significantly enhances the success of mitigation measures.

Columns 3 and 4 demonstrate how policy measures are related to new deaths per million during the crisis. Specifically, suppression measures (β= 70.599) show a positive association with new deaths in column 3, but the relationship is not statistically significant. These measures were either insufficient to curb the spread of new infections in the short term or implemented reactively in areas with already rising new cases. Additionally, mitigation measures are positively and significantly associated with new deaths. A one-unit increase in mitigation measures is correlated with an increase of approximately 70 new deaths per million. Contrary to the expectation, it likely reflects the context in which these measures were introduced: regions experiencing substantial outbreaks might have adopted these measures as a reactive strategy. Conversely, countries with higher confidence in government are consistently and significantly associated with lower mortality both in terms of total and new deaths. For every one-unit increase in trust, new deaths decrease by 14.421, as shown in column 3.

Column 4 shows the estimated interaction between policy measures–both suppression and mitigation measures–and trust in government. The estimated coefficient for the interaction term between suppression measures and trust (β= -8.003) is negative and statistically significant at p<0.05.

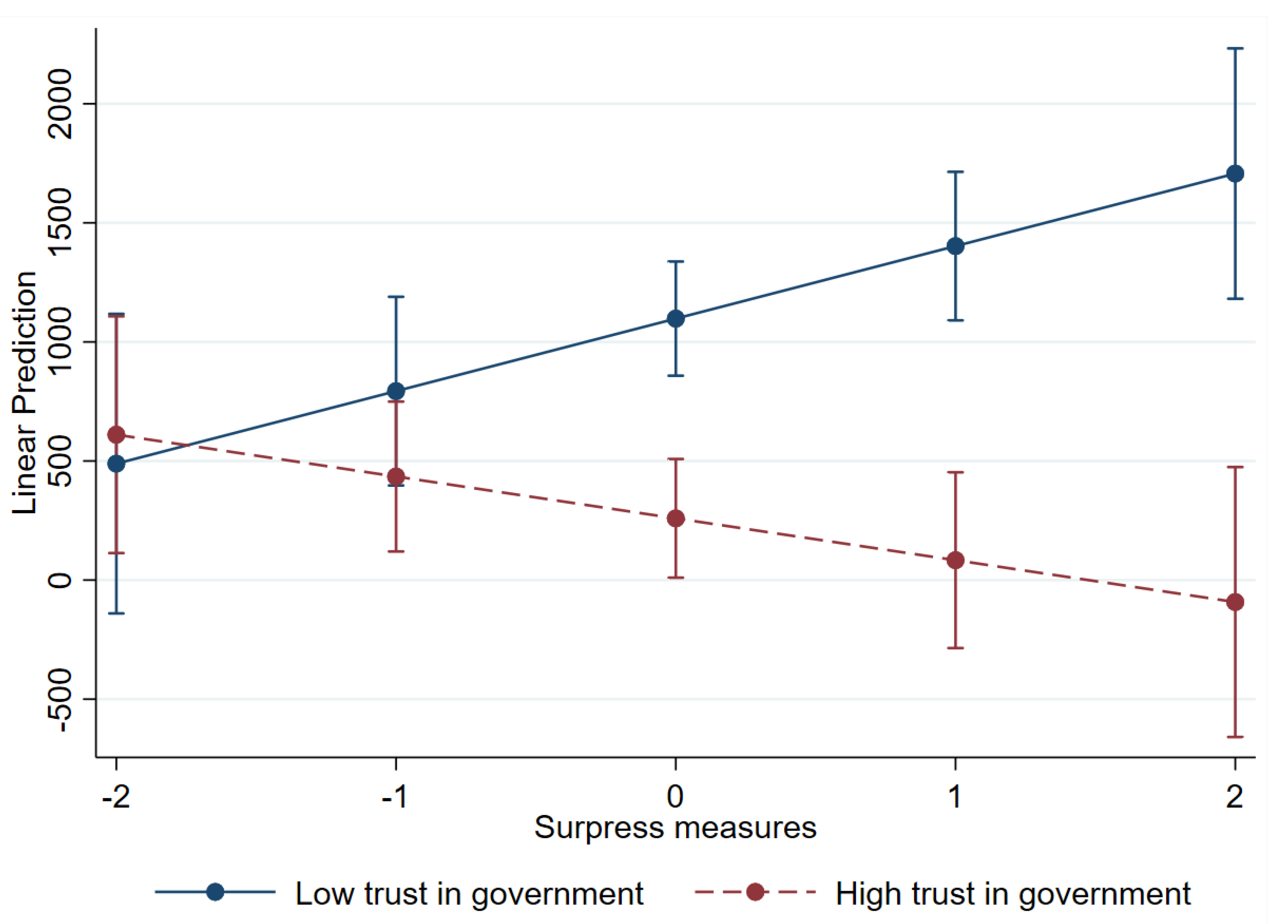

Figure 4 graphically shows how the relationship between suppression measures and new deaths is contingent on the level of trust in government. It indicates that where trust in government is high, suppression measures (higher than zero) are effective in reducing new mortality in the crisis. Conversely, where trust in government is low, new deaths likely increase, even with the implementation of suppression measures. These findings confirm the critical role of public trust in ensuring compliance with policies and mitigating the spread of infections, ultimately reducing new fatalities.

Similarly, the coefficient for the interaction between mitigation measures and trust in government (β= -9.473) is negative and statistically significant at p<0.001. It indicates that trust in government enhances the effectiveness of mitigation measures in reducing new deaths. When the public trusts the government, compliance with mitigation policies, such as mask-wearing and social distancing, is higher, less likely leading to new deaths.

Figure 5 shows the relationship between mitigation measures and new deaths at varying levels of trust in government. Similar to

Figure 4, the downward slope indicates that where trust in government is high, the effectiveness of mitigation measures improves, leading to fewer new deaths. However, where trust is low, new deaths tend to increase even with the higher level of mitigation measures. In sum, trust in government plays a crucial role in reducing new deaths when both suppression and mitigation measures are implemented. These findings reflect the critical need for governments to foster trust to maximize the impact of policies during health crises.

For control variables, a higher aging population rate is strongly associated with increased new deaths, while hospital beds, economic development, and the HDI are not statistically significant in the models. Overall, both suppression and mitigation measures are likely to be reliant on trust in government in controlling new deaths, which emphasizes the need for building public trust in a crisis.

5. Discussion

This study aims to theoretically verify the effectiveness of the government's policies. Policies are defined as “actions that the government decides to do or not do” [

36], “government activities on the premise of social change to solve problems” [

37], and “Future Action Guidelines determined by government agencies” [

38]. After all, policies are the government’s active or passive actions for problem solving.

Presenting generalized results with a comparison of national policies was difficult owing to the specificity of the national situation and diversity of policy problems and measures. However, the COVID-19 pandemic situation was a common health-disaster situation experienced worldwide, and the response by country was also characterized by similar prescriptions, albeit to different degrees. Therefore, presenting generalized results on the effectiveness of the government's non-pharmaceutical measures to cope with the pandemic may be reasonable.

Therefore, this study analyzed how the government's non-pharmaceutical measures affect the number of deaths from COVID-19 and verified the moderating effect of government trust as a situational variable. As a result of the analysis, several topics for discussion can be derived.

First, this study categorized government responses to COVID-19 policies into suppression and mitigation measures, revealing differing effects for each type. Specifically, suppression measures had a significant relationship with the reduction in the number of total deaths, but their relationship with the number of new deaths was not statistically significant. In contrast, mitigation measures exhibited consistent and significant relationships with increases in both total deaths and new deaths. These findings suggest that government policies, such as mandatory mask-wearing during the early stages of the pandemic, might not have been highly effective. Instead, they imply that the failure to implement appropriately timed and adequately scaled policies can be associated with increases in mortality. Suppression measures, by contrast, aim for the complete containment of the virus through strategies that more directly restrict people's mobility and behavior [

18,

19]. These strategies demonstrate effectiveness in significantly reducing total deaths, indicating the potential impact of government interventions. Overall, the results highlight that the intensity of government measures leads to differences in direct effects, while also pointing to the potential for unintended consequences.

Second, trust in the government has a positive effect on the decrease in the total number of deaths and new deaths. Nevertheless, simply interpreting that trust in government has a direct causal relationship with the number of deaths has a limit [

21]. The effect of reducing the number of deaths in countries with high trust in the government may be due to high compliance with the government's measures. Ji et al. [

9] supported these results, conforming that trust in the government increases compliance with government measures. Additionally, the effect of trust in government can be explained owing to each country’s various specificities [

21]. Therefore, discussing various characteristics of each country along with trust in government is necessary.

Finally, according to the analysis results, the moderating effect of government trust has a significant negative and statistically significant on the number of new deaths. In other words, suppression measures showed a direct effect on the increase in the number of new deaths, but the stronger the degree of government trust, the weaker the effect of these suppression measures. The moderating effect of government trust with mitigation measures is statistically significant with regard to both total and new deaths, showing a negative effect. Mitigation measures show a direct effect on the increase in the number of total and new deaths, but the higher the government trust, the less the effect of increasing the number of deaths. Strong lockdowns implemented by governments have no moderating effect on trust, but weak lockdowns have a moderating effect [

21]. Additionally, the interaction effect of government trust in compulsory mask-wearing measures has been verified [

9]. According to the analysis results of this study and previous studies, government trust, by combining with weak-intensity measures, suppressed the increase in the number of deaths. Since weak-intensity measures are mainly implemented at the beginning of the pandemic, the effect of government trust needs to be considered with regard to the stage of the spread of the pandemic.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to verify the effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical measures implemented by the government during the COVID-19 pandemic. For verification, this study conducted an analysis using panel data for three years for OECD countries. The analysis results have several implications. First, governments around the world implemented similar measures, such as social distancing, to respond to the spread of the pandemic. Nevertheless, the range and intensity of responses varied by country. In other words, the response to the pandemic can be differentiated according to each country’s specificities. These results suggest that non-pharmaceutical measures of countries in pandemic times need to consider the country’s various environmental factors.

Second, trust in the government had a positive effect on the decrease in the number of deaths and also a moderating effect with mitigation measures. The results showed that trust in the government can be an important factor in overcoming health disasters such as COVID-19. Mitigation measures had a positive effect on the increase in the number of total and new deaths. These results conflict with the expectation that both measures will reduce the number of deaths; rather, they may have the side effects of increasing the number of deaths. Government trust, combined with two measures, has a moderating effect of reducing the magnitude of the increase in the number of deaths. Therefore, trust in the government has the effect of weakening the side effects that can be caused by the two measures.

In particular, mitigation measures, which consist of mask wearing and campaigns, independently increase the number of deaths. Mitigation measures were recommended or enforced by the governments of each country in the pandemic’s early stages. Since mask wearing causes inconvenience to people, resistance to forcing it appeared in some regions [

9]. These people's discomfort and resistance weakened their compliance with mitigation measures in the period before the pandemic spread in earnest. This phenomenon might have resulted in an increase in the number of deaths by failing to prevent the spread of the pandemic.

However, in countries with high trust in the government, people's compliance with the government's mitigation measures can increase. Additionally, high compliance with government policies can weaken the increase in the number of deaths. Therefore, the importance of the government's trust accumulated in the people as well as the government's direct measures to cope with the pandemic can be confirmed. Moreover, great effect of trust in the government can vary depending on the intensity of non-pharmaceutical measures and the stage of the spread of the pandemic. Weak-intensity measures such as wearing a mask are likely to be implemented in the early stages of the pandemic, and the higher the government's trust, the higher the compliance with weak-intensity measures. As a result, it can reduce the increase in the number of deaths caused by the pandemic.

Third, suppression measures, which directly affect people's movement and daily life, have a negative relationship with total deaths. The interaction effect between suppression measures and trust in government has been confirmed only in reducing new deaths, but the direct relationships with both total and new deaths have been strongly supported.

Suppression measures, which are more intense in constraints than mitigation ones, were mainly implemented when the spread of the pandemic reached its peak. In the annual analysis, suppression measures scored the highest in 2021, at the peak of COVID-19. Since this was the period when health risks were the most serious, people naturally complied with the government's strong deterrence measures regardless of whether they had trust in the government. Thus, the direct effect of suppression measures was positive according to these situational conditions. The results of this analysis emphasize that strong deterrence policies are inevitably used during the period of rapid spread of the pandemic, and the effects of such measures are also positive.

The above analysis results, suggest that the overall effectiveness of OECD countries' measures to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic is limited, but trust in the government directly or indirectly affects the number of deaths. Therefore, how the government gains people’s trust can act as an important environmental condition in overcoming the crisis in a time of health disaster. Additionally, the effectiveness of each measure may be differentiated by the period of the pandemic, and the mechanism of effectiveness may vary. Trust in government may reduce the side effects of weak measures at the beginning of the pandemic, but at the pandemic’s peak of the pandemic, the direct effect of strong measures may be even greater. The government needs to establish a differentiated response strategy according to the timing and spread of the pandemic, and the degree of public trust in the government.

This study has several limitations. First, the classification of the timing of the analysis was excessively simple. Responses to COVID-19 can vary sensitively on a monthly or daily basis as well as on an annual basis. Therefore, the change in government response can be accurately grasped by further subdividing and analyzing the period of the pandemic. This study had the limitation that elaborately analyzing the government's response during the COVID-19 period was insufficient because variables other than the government's response were provided annually.

Next, vaccination was not considered. The situation before and after vaccination may show differences with regard to the effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical measures, but our analysis did not reflect this. Finally, inverse causality must be considered. This study assumed a causal relationship between the strictness of the government measures and the number of deaths, but some studies have found an inverse causal relationship between the number of deaths and government measures [

9]. In other words, as the number of deaths increases, the strictness of the government's NPIs becomes stronger. Additionally, a study found that government trust increases when the number of deaths from COVID-19 decreases [

21]. Future studies must verify the inverse causality between these government measures and the number of deaths.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization; methodology, Jaesun Wang; Analysis, Hyunjung Kim. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by 2021 Research Grant from Kangwon National University.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting analysis of this article are included within the article and reference.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Factor Analysis.

Table A1.

Factor Analysis.

| Component |

Suppression |

Mitigation |

| Facial Coverings |

.409 |

.748 |

| Restrictions on Internal Movement |

.787 |

-.002 |

| International Travel Controls |

.807 |

-.056 |

| Public Information Campaigns |

-.239 |

.858 |

| Cancel Public Events |

.945 |

.026 |

| Restrictions on Gatherings |

.876 |

.068 |

| Stay-at-Home Requirements |

.873 |

.055 |

| Workplace Closures |

.933 |

.139 |

Notes

| 1 |

For example, in Germany, wearing a mask for 20 days reduced infectious disease cases by 45%, while economic costs were lower compared to other measures [ 7]. |

| 2 |

Two studies have focused on the causality between trust in the government and effectiveness of government response. Contrary to some studies that have verified whether government trust affects the effectiveness of government response, others have verified whether the effectiveness of government response affects government trust. Some studies have verified the former’s causality but also considered the existence of inverse causality [ 21]. Stanica et al. [ 30] empirically verified that the strictness of government response to COVID-19 affected government trust. |

References

- Dergiades, T.; Milas, C.; Mossialos, E.; Panagiotidis, T. Effectiveness of government policies in response to the first COVID-19 outbreak. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2(4), e0000242. [CrossRef]

- Cowling, B.J.; Ali, S.T.; Ng, T.W.Y.; Tsang, T.K.; Li, J.C.M.; Fong, M.W.; Liao, Q.; Kwan, M.Y.W.; Lee, S.L.; Chiu, S.S.; Wu, J.T.; Wu, P.; Leung G.M. Impact assessment of non-pharmaceutical interventions against coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza in Hong Kong: an observational study. The Lancet Pub. Health 2020, 5, e279–88. [CrossRef]

- Hartl, T.; Wälde, K.; Weber, E. Measuring the impact of the German public shutdown on the spread of Covid-19. Covid Econ. 2020, 1, 25-32.

- Hsiang, S.; Allen, D.; Annan-Phan, S.; Bell, K.; Bolliger, I.; Chong, T.; Druckenmiller, H.; Huang, L.Y.; Hultgren, A.; Krasovich, E.; Lau, P.; Lee, J.; Rolf, E.; Tseng, J.; Wu, T. The effect of large-scale anti-contagion policies on the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature 2020, 584, 262-267. [CrossRef]

- Agyapon-Ntra, K.; McSharry, P.E. A global analysis of the effectiveness of policy responses to COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5629. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kwak, D.; Park, C.M. Pandemic and Role of Government. In COVID-19 Pandemic in Korea: Public Views, 1st ed.; Park, C.M., Yoon, G.S., Eds.; Park Young-sa: Seoul, S.Korea, 2024; pp.323-354.

- Mitze, T.; Kosfeld, R.; Rode, J.; Wälde, K. Face masks considerably reduce COVID-19 cases in Germany. PNAS 2020, 117(51), 32293-32301. [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, F. Governance: What Do We Know, and How Do We Know It?. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2016, 19(1), 89–105. [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y. Political trust and government performance in the time of COVID-19. World Dev. 2024, 176, 106499. [CrossRef]

- Thoradeniya, T.; Jayasinghe, S. COVID-19 and future pandemics: a global systems approach and relevance to SDGs. Glob. Health 2021, 17(1), 59. [CrossRef]

- Behl, A.; Nair, A.; Mohagaonkar, S.; Yadav, P.; Gambhir, K.; Tyagi, N.; Sharma, R. K.; Butola, B.S.; Sharma, N. Threat, challenges, and preparedness for future pandemics: A descriptive review of phylogenetic analysis based predictions. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2022, 98, 105217. [CrossRef]

- Hale, T.; Angrist, N.; Goldszmidt, R.; Kira, B.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; Webster, S.; Cameron-Blake, E.; Hallas, L.; Majumdar, S.; Tatlow, H. A global panel database of pandemic policies(Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5(April), 529-538. [CrossRef]

- Hale, T.; Angrist, N.; Kira, B.; Goldszmidt, R.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T. Pandemic Governance Requires Understanding Socioeconomic Variation in Government and Citizen Responses to COVID-19. SSRN 2020, June. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3641927.

- World Health Organization(WHO). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020. 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-sopening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020.

- OECD. First lessons from government evaluations of COVID-19 responses: A synthesis. OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19) 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- Rahmouni, M. Efficacy of Government Responses to COVID-19 in Mediterranean Countries. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 3091-3115. [CrossRef]

- Toshkov, D.; Carroll, B.; Yesilkagit, K. Government capacity, societal trust or party preferences: what accounts for the variety of national policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe. J. Eur. Public Policy 2022, 29(7), 1009-1028. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, N.M.; Laydon, D.; Nedjati-Gilani, G.; Imai, N.; Ainslie, K.; Baguelin, M.; Bhatia, S.; Boonyasiri, A.; Cucunubá, Z.; Cuomo-Dannenburg, G.; Dighe, A.; Dorigatti, I.; Fu, H.; Gaythorpe, K.; Green, W.; Hamlet, A.; Hinsley, W.; Okell, L.C. .; van Elsland, S.; Thompson, H.; Verity, R.; Volz, E.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Walker, P. G.T. .; Walters, C.; Winskill, P.; Whittaker, C.; Donnelly, C.A. .; Riley, S.; Ghani, A.C. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand. MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis Report9 2020, Imperial College London.

- González-Bustamante, B. Evolution and early government responses to COVID-19 in South America. World Dev. 2021, 137, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. The Pandemic and the light and shade of the government intervention. In COVID-19 Pandemic in Korea: Public Views, 1st ed.; Park, C.M., Yoon, G.S., Eds.; Park Young-sa: Seoul, S.Korea, 2024; pp.179-225.

- Zaki, B.L.; Nicoli, F.; Wayenberg, E.; Verschuere, B. In trust we trust: The impact of trust in government on excess mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Policy Adm. 2022, 37(2), 226-252. [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perceived risk, trust, and democracy. Risk Anal. 1993, 13(6), 675–682. [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Pidgeon, N.F. Exploring the Dimensionality of Trust in Risk Regulation. Risk Anal. 2003, 23(5), 961-972. [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Zingg, A. The Role of Public Trust During Pandemics. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19(1), 23–32. [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M. Trust and Risk Perception: A Critical Review of the Literature. Risk Anal. 2019, 41(3), 480-490. [CrossRef]

- Zahariadis, N.; Petridou, E.; Exadaktylos, T.; Sparf, J. The Politics of National Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Policy Styles and Trust in the Age of Pandemics: Global Threat, National Responses, 1st ed.; Zahariadis, N., Petridou, E., Exadaktylos, T., Sparf, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, USA, 2022; pp.3-16.

- Bulut, H.; Samuel, R. The role of trust in government and risk perception in adherence to COVID-19 prevention measures: survey findings among young people in Luxembourg. Health Risk Soc. 2023, 25(7-8), 324-349. [CrossRef]

- Steen, T.; Brandsen, T. Coproduction during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic: Will It Last?. Public Adm. Rev 2020, 80(5), 851-855. [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Li, N.; Liu, L. Do national cultures matter in the containment of COVID-19?. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2020, 40(9/10), 939-961. [CrossRef]

- Stanica, C.; Crosby, A.; Larson, S. Trust in Government and COVID-19 Response Policy: A Comparative Approach. J. Compar. Policy Anal.: Res. & Prac. 2023, 25(2), 156-171. [CrossRef]

- Harring, N.; Jagers, S.C. Should We Trust in Values? Explaining Public Support for Pro-Environmental Taxes. Sustainability 2013, 5(1), 201-227. [CrossRef]

- Widaningrum, A. Public trust and regulatory compliance. Jurnal ISIP 2017, 21. [CrossRef]

- Fetzer, T.; Witte, M.; Hensel, L.; Jachimowicz, J.M.; Haushofer, J.; Ivchenko, A.; Caria, S.; Reutskaja, E.; Roth, C.; Fiorin, S.; Gomez, M.; Kraft-Todd, G.; Goetz, F.; Yoeli, Erez. GLOBAL BEHAVIORS AND PERCEPTIONS IN THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC. CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP14631 2020, Available online : SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3594262 (accessed on 4th October 2024).

- Adolph, C.; Amano, K.; Bang-Jensen, B.; Fullman, N.; Wilkerson, John. Pandemic Politics: Timing State-Level Social Distancing Responses to COVID-19. J. Health. Polit. Policy Law 2021, 46(2), 211-233. [CrossRef]

- Haerpfer, C.; Inglehart, R.; Moreno, A.; Welzel, C.; Kizilova, K.; Diez-Medrano, J.; Lagos, M.; Norris, P.; Ponarin, E.; Puranen,B. World Values Survey Wave 7 (2017-2022) Cross-National Data-Set. Version: 4.0.0. World. Values Survey Association. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, E.; Ritchie, H.; Rodés-Guirao, L.; Appel, C.; Gavrilov, D.; Giattino, C .; Hasell, J .; Macdonald, B .; Dattani, S.; Beltekian, D.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Roser, M. COVID-19 Pandemic. Published online at OurWorldinData.org. 2020, Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (accessed on 3rd October 2024).

- OECD. Trust in Government Indicator. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/trust-in-government.html (accessed on 24th October 2024).

- World Bank. World Development Indicators. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/ source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 11th November 2024).

- Dye, T.R. Understanding public Policy, 15rd ed.; Pearson: New Jersey, USA, 2016, pp. 3-13.

- Lasswell, H.D. The Policy Orientation. In The Policy Sciences: Recent Developments in Scope and Method, 1st ed.; Lerner, D., Lasswell, H.D., Eds.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1951, pp. 3-15.

- Dror. Y. Public Policy Making Reexamined, 1st ed.; Routledge: New Your; USA, 1983; pp. 25-32.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).