Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

01 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

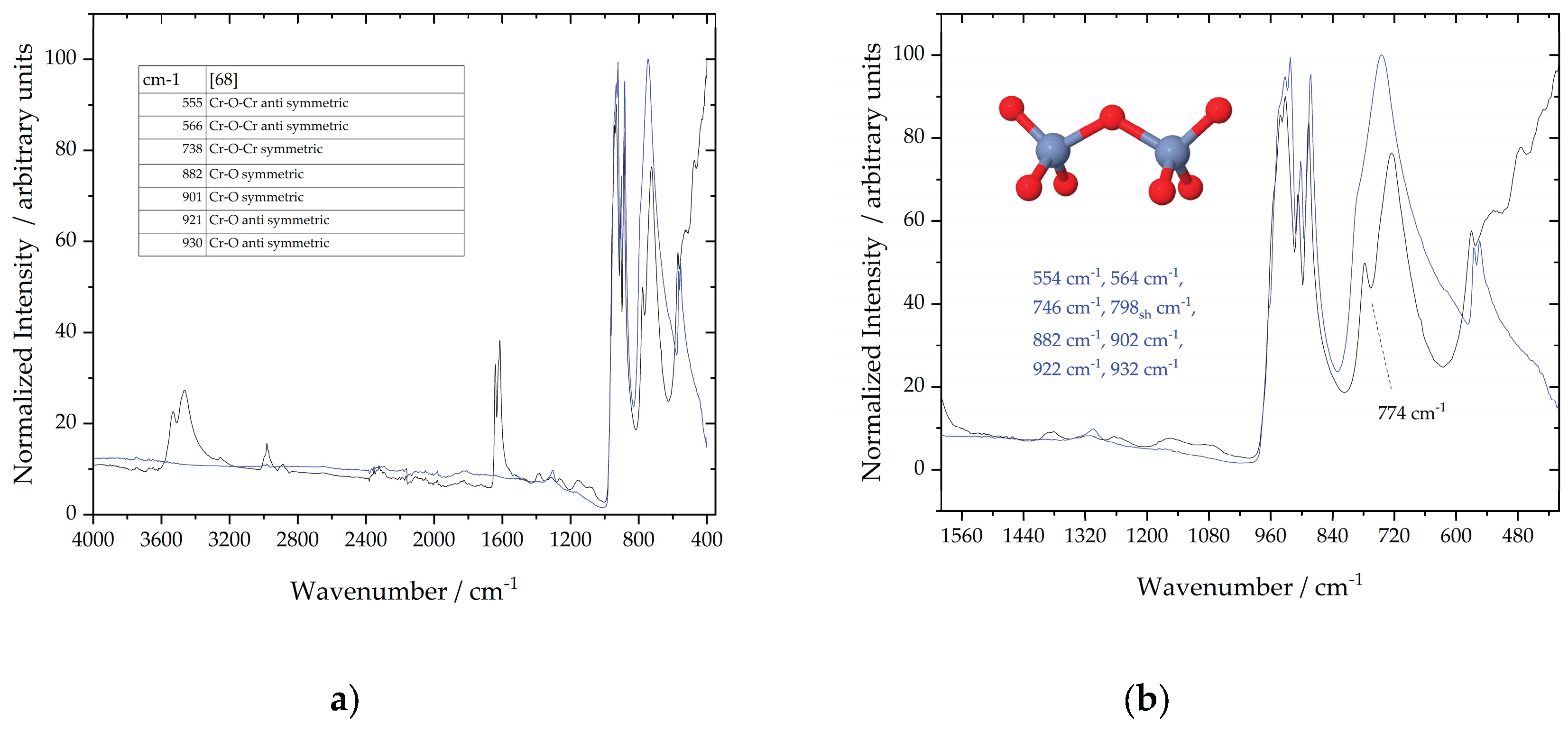

2. Vibrational Spectroscopy to Elucidate the Structures of the Coatings

2.1. Studies of Hexavalent Chromium Conversion Coatings

2.2. Studies of Trivalent Chromium Conversion Coatings

2.3. Studies of Coatings Formed from Electroplated Cr(VI) Baths

2.4. Studies of Coatings Formed from Electroplated Cr(III) Baths

3. Vibrational Studies on Aqueous Solutions

3.1. Studies of Hexavalent Chrome Baths for Conversion Coatings or Electrodeposition Processes

3.2. Studies of Trivalent Chromium Baths Used for Conversion Coatings or Electrodeposition Processes

4. Reference Spectra of the Pure Chromium Compounds

5. Future Needs: Perspective on Methodology

6. Conclusions

- Studies of hexavalent chromium conversion coatings

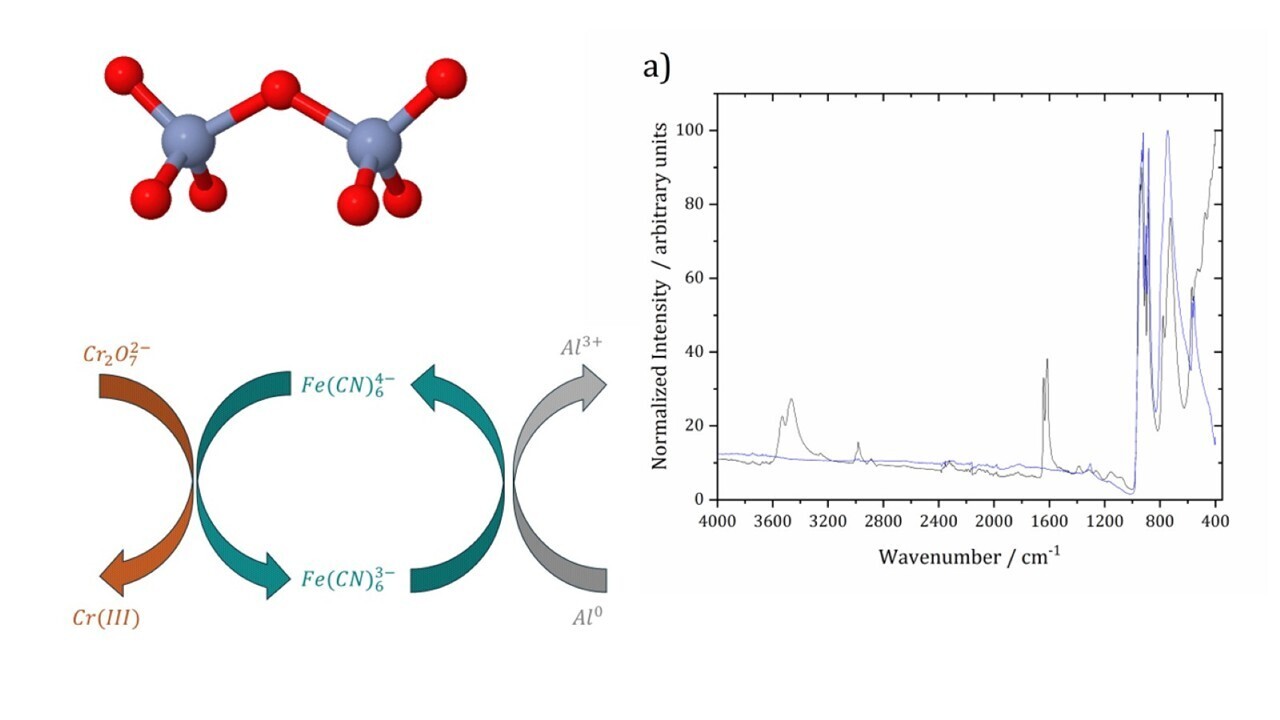

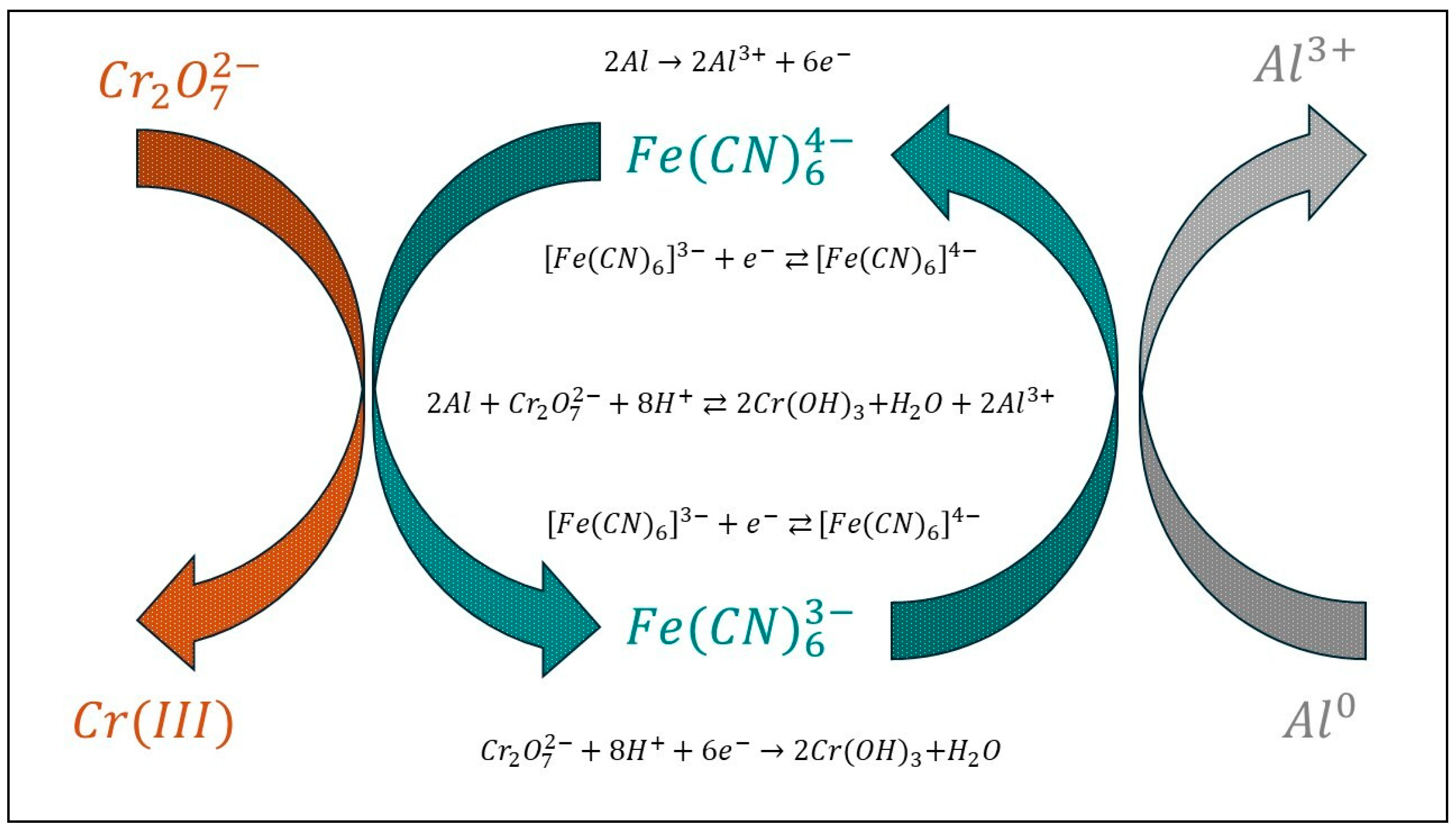

- The majority of these studies focus on this kind of coating, and several powerful techniques have been used, including synchrotron infrared microspectroscopy. It was possible to understand the structure of the two-layer coating and the chemical composition of each layer.Additionally, the distributions on the surfaces of the different phases present were accurately identified; for example, vibrational spectroscopy reveals zones with high Cr(VI) contents, which are located at the edges of the scratch. Vibrational spectroscopy confirmed the mechanism for coating formation, in which ferricyanide was a redox mediator. In addition, vibrational spectroscopy was effective in determining the mechanism of corrosion resistance of the coatings. When pitting corrosion occurs, the migration process of Cr(VI) ions to repair the coating in damage zones was described on the basis of Raman or IR spectra.

- Studies of trivalent chromium conversion coatings

- The toxicity of Cr(VI) species has restricted their use in surface finishing, and they have been replaced by Cr(III) species. Raman spectroscopy is a very effective technique for surface characterization because it clearly shows how the constituent ions of the bath are transformed into surface species. Vibrational spectroscopy revealed the formation mechanism of the coating on an alloy from a bath, which contains , and a Cr(III) sulfate salt. The trivalent chromium conversion coating consists of two main layers, whose compositions were identified on the basis of vibrational spectroscopy. The presence of Cr(VI) in these coatings is promoted by the presence of hydrogen peroxide, which is formed by the reduction of dissolved oxygen gas in the bath. The formation of Cr(VI) in these coatings is controversial with respect to environmental directives. Consequently, it has been proposed that baths containing Cu(II) or Fe(II) species suppress the formation of Cr(VI). This strategy was evaluated via vibrational spectroscopy.

- Studies of coatings formed from electroplated Cr(VI) baths.

- Studies of coatings formed from electroplated Cr(III) baths

- Studies of hexavalent chrome baths for conversion coatings or electrodeposition processes

- Studies of trivalent chromium baths used for conversion coatings or electrodeposition processes

- Reference spectra of the pure chromium compounds

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| ATR | Attenuated total reflectance |

| DRIFTS | Diffuse reflectance infrared spectroscopy |

| RAIRS | Reflection absorption infrared spectroscopy |

| IRSE | Infrared spectroscopic ellipsometry |

| GAIRS | Grazing angle infrared spectroscopy |

| SIRMS | synchrotron infrared microspectroscopy |

| EXAFS | Extended X-ray absorption fine structure |

| XANES | X-ray absorption near edge structure |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| CE | Current efficiency |

References

- Dubpernell G.; History of chromium plating, Plat. Surf. Finish., 1984, 71, 84-91.

- Mandich N.V.; Snyder D.L.; Electrodeposition of chromium, In Modern Electroplating; M., Schlesinger, M. Paunovic, Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Inc, Hoboken, New Jersey, U.S. 2010, pp 205-211,214,233. [CrossRef]

- Prakash B. S.; Balaraju J. N.; Chromate (Cr6+)-free surface treatments for active corrosion protection of aluminum alloys: a review, J. Coat Technol Res., 2024, 21, 105–135. [CrossRef]

- Protsenko V. S.; Kinetics and Mechanism of Electrochemical Reactions Occurring during the Chromium Electrodeposition from Electrolytes Based on Cr(III) Compounds: A Literature Review, Reactions, 2023, 4, 398–419. [CrossRef]

- Tian X.; Chen S.; F. Zhu; Z. Cai; L. Wang; Review, Towards cleaner production of trivalent chromium electrodeposition: Mechanism, process and challenges, J. Clean. Prod., 2024, 476, 143768. [CrossRef]

- Protsenko V.; A review on electrodeposition and tribological performance of chromium-based coatings from eco-friendly trivalent chromium baths, Discover Electrochemistry, 2025, 2, 22. [CrossRef]

- Hesamedini S.; Bund A., Trivalent chromium conversion coatings, J. Coat. Technol. Res., 2019, 16, 623–641. [CrossRef]

- Becker M.; Chromate-free chemical conversion coatings for aluminum alloys, Corros. Rev, 2019, 37, 321–342. [CrossRef]

- Ahern A. M.; Schwartz P. R.; Shaffer L. A.; Characterization of Conversion-Coated Aluminum Using Fourier Transform Infrared and Raman Spectroscopies, Appl. Spectrosc., 1992, 46, 1412-1419 https://opg.optica.org/as/abstract.cfm?URI=as-46-9-1412. [CrossRef]

- Matienzo L. J.; Holum K. J.; Surface studies of corrosion-preventing coatings for aluminum alloys, Appl. Surf. Sci., 1981, 9, 47—73.

- Lytle F. W.; Greegor R. B.; Bibbins G. L.; Blohowiak K. Y.; Smith R. E.; Tuss G. D.; An investigation of the structure and chemistry of a chromium-conversion surface layer on aluminum, Corros. Sci., 1995, 37, 349-369. [CrossRef]

- Lenglet M.; Petit F.; Malvault J. Y.; Reflectance spectroscopy (0.03 to 6 eV) of Cr3+ and Cr (VI) products of chromate conversion coatings, Phys. Status Solidi (a), 1994, 143, 361-365. [CrossRef]

- Xia L.; McCreery R. L.; Chemistry of a Chromate Conversion Coating on Aluminum Alloy AA2024-T3 Probed by Vibrational Spectroscopy, J. Electrochem. Soc., 1998, 145, 3083-3089. [CrossRef]

- L. Xia; R.L. McCreery; Structure and Function of Ferricyanide in the Formation of Chromate Conversion Coatings on Aluminum Aircraft Alloy, J. Electrochem Soc., 1999, 146, 3696-3701. [CrossRef]

- Juffs L.; Hughes A. E.; Furman S.; Paterson P. J. K.; The use of macroscopic modelling of intermetallic phases in aluminium alloys in the study of ferricyanide accelerated chromate conversion coatings, Corros. Sci., 2002, 44, 1755-1781. [CrossRef]

- Campestrini P.; Böhm S.; Schram T.; Terryn H.; Wit J. H. W. de; Study of the formation of chromate conversion coatings on Alclad 2024 aluminum alloy using spectroscopic ellipsometry, Thin Solid Films, 2002, 410, 76–85. [CrossRef]

- Petit F.; Debontride H.; Lenglet M.; Juhel G.; Verchere D.; Contribution of Spectrometric Methods to the Study of the Constituents of Chromating Layers, Appl. Spectrosc., 1995, 49, 207-210. [CrossRef]

- Schram T.; Laet J. De; Terryn H.; Nondestructive optical characterization of chemical conversion coatings on aluminum, J. Electrochem Soc., 1998, 145, 2733-2739. [CrossRef]

- Schram T.; Terryn H.; The use of Infrared spectroscopic ellipsometry for the thickness determination and molecular characterization of thin films on aluminum, J. Electrochem Soc., 2001, 148, F12-F20. [CrossRef]

- Chidambaram D.; Halada G. P.; Clayton C. R.; Synchrotron Radiation Based Grazing Angle Infrared Spectroscopy of Chromate Conversion Coatings Formed on Aluminum Alloys, J. Electrochem Soc., 2004, 151, B160-B164. [CrossRef]

- R. Holze; Surface and Interface Analysis, An Electrochemists Toolbox, Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 2009, PP.102, 128, 137-139. [CrossRef]

- J. Vasquez; M.; G.P. Halada; C.R. Clayton; J.P. Longtin; On the nature of the chromate conversion coating formed on intermetallic constituents of AA2024-T3. Surf. Interface Anal., 2002, 33, 607-616. [CrossRef]

- Vasquez M. J.; Halada G.P.; Clayton C.R.; The application of synchrotron-based spectroscopic techniques to the study of chromate conversion coatings, Electrochim. Acta, 2002, 47, 3105-3115. [CrossRef]

- Chidambaram D.; Vasquez M. J.; Halada G. P.; Clayton C. R.; Studies on the repassivation behavior of aluminum and aluminum alloy exposed to chromate solutions, Surf. Interface Anal., 2003, 35, 226-230. [CrossRef]

- McGovern W. R.; Schmutz P.; Buchheit R. G.; McCreery R. L.; Formation of Chromate Conversion Coatings on Al-Cu-Mg Intermetallic Compounds and Alloys, J. Electrochem. Soc., 2000, 147, 4494-4501. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J.; Xia L.; Sehgal A.; Lu D.; McCreery R.L.; Frankel G.S.; Effects of Chromate Conversion Coatings on Corrosion of Aluminum Alloy 2024-T3, Surf. Coat. Technol., 2001,140, 51-57. [CrossRef]

- Hurley B. L.; McCreery R. L.; Raman Spectroscopy of Monolayers Formed from Chromate Corrosion Inhibitor on Copper Surfaces, J. Electrochem. Soc., 2003, 150, B367-B373. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X.; Van Den Bos C.; Sloof W.G.; Terryn H.; Hovestad A.; Wit J. H. W. De; Investigation of Cr(III) based conversion coatings on electrogalvanised steel, Surf. Eng., 2004, 20, 244-250. [CrossRef]

- Li L.; Swain G. P.; Howell A.; Woodbury D.; Swain G. M.; The formation, structure, electrochemical properties and stability of trivalent chrome process (TCP) coatings on AA2024, J. Electrochem. Soc., 2011, 158, C274-C283. [CrossRef]

- Li L.; Kim D. Y.; Swain G. M.; Transient formation of chromate in trivalent chromium process (TCP) coatings on AA2024 as probed by Raman spectroscopy, J. Electrochem. Soc., 2012, 159 C326-C333. [CrossRef]

- L. Li, G. M., Swain, Formation and structure of trivalent chromium process coatings on aluminum alloys 6061 and 7075, Corrosion, 2013, 69, 1205-1216.

- Qi J. T.; Hashimoto T.; Walton J. R.; Zhou X.; Skeldon P.; Thompson G. E.; Trivalent chromium conversion coating formation on aluminium, Surf. Coat. Technol., 2015, 280, 317–329. [CrossRef]

- Qi J.; Walton J.; Thompson G. E.; Albu S. P.; Carr J.; Spectroscopic studies of chromium VI formed in the trivalent chromium conversion coatings on aluminum, J. Electrochem. Soc., 2016,163, C357. [CrossRef]

- Munson C. A.; Swain G. M.; Structure and chemical composition of different variants of a commercial trivalent chromium process (TCP) coating on aluminum alloy 7075-T6. Surf. Coat. Technol., 2017, 315, 150-162. [CrossRef]

- Qi J.; Gao L.; Liu Y.; Liu B.; Hashimoto T.; Wang Z.; Thompson G. E.; Chromate formed in a trivalent chromium conversion coating on aluminum, J. Electrochem. Soc. 164 (2017) 442-C449. [CrossRef]

- Qi J.; Miao Y.; Wang Z.; Li Y.; Zhang X.; Skeldon P.; Thompson G.E.; Influence of copper on trivalent chromium conversion coating formation on aluminum, J. Electrochem. Soc., 2017, 164, C611-C617. [CrossRef]

- Qi J.; Zhang B.; Wang Z.; Li Y.; Skeldon P.; Thompson G. E.; Effect of an Fe (II)-modified trivalent chromium conversion process on Cr (VI) formation during coating of AA 2024 alloy, Electrochem. commun., 2018, 92 (1-4. [CrossRef]

- Qi J.; Światowska J.; Skeldon P.; P. Marcus; Chromium valence change in trivalent chromium conversion coatings on aluminium deposited under applied potentials, Corros. Sci., 2020, 167, 108482. [CrossRef]

- Qi J.; Z. Ye; Gong N.; Qu X.; Mercier D.; Światowska J.; Skeldon P.; Marcus P.; Formation of a trivalent chromium conversion coating on AZ91D magnesium alloy, Corros. Sci., 2021, 186, 109459. [CrossRef]

- Sun W.; Bian G.; Jia L.; Pai J.; Ye Z.; Wang N.; Qi J.; Li T.; Study of trivalent chromium conversion coating formation at Solution—Metal interface. Metals, 2023, 13, 93. [CrossRef]

- Hedenstedt K.; Gomes A. S. O.; Busch M.; Ahlberg E, Study of Hypochlorite Reduction Related to the Sodium Chlorate Process, Electrocatalysis (2016) 7:326–335. [CrossRef]

- Hatch J. J; Gewirth A A.; Potential dependent chromate adsorption on gold, J. Electrochem. Soc., 2009, 156, D497-D502. [CrossRef]

- Gomes A. S. O.; Busch M.; Wildlock M.; Simic N.; Ahlberg E.; Understanding Selectivity in the Chlorate Process: A Step towards Efficient Hydrogen Production, Chemistry Select, 2018, 3, 6683 – 6690. [CrossRef]

- Gomes A. S. O.; Simic N.; Wildlock M.; Martinelli A.; Ahlberg E.; Electrochemical Investigation of the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction on Electrodeposited Films of Cr(OH)3 and Cr2O3 in Mild Alkaline Solutions, Electrocatalysis, 2018, 9 333–342. [CrossRef]

- Mardanifar A.; Mohseni A.; Mahdavi S.; Wear and corrosion of Co-Cr coatings electrodeposited from a trivalent chromium solution: Effect of heat treatment temperature, Surf. Coat. Technol., 2021, 422, 127535. [CrossRef]

- Kus E.; Haciismailoglu M.; Arper M.; Binary potential loop electrodeposition and corrosion resistance of Cr coatings, J. Appl. Electrochem., 2024, 54, 2871-2886. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Q.; Lu Z.; Ling Y.; Wang J.; Wang R.; Li Y.; Zhang Z.; Characteristic and behavior of an electrodeposited chromium (III) oxide/silicon carbide composite coating under hydrogen plasma environment, Fusion Eng. Des., 2019, 143, 137-146. [CrossRef]

- Kajita M.; Saito K.; Abe N.; Shoji; K. Matsubara; T. Yui; M. Yagi; Visible-light-driven water oxidation at a polychromium-oxo-electrodeposited TiO2 electrode as a new type of earth-abundant photoanode, Chem. Commun., 2014, 50, 1241-1243. [CrossRef]

- Huang C.A.; Liu Y.W.; Chuang-Chen Y.; Role of carbon in the chromium deposit electroplated from a trivalent chromium based bath, Surf. Coat. Technol, 2011, 205, 3461-3466. [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar J. M.; Varanasi R. S.; Silva C. C. da; Saood S.; Vooys A. de; Erbe A.; Rohwerder M.; Chromium coatings from trivalent chromium plating baths: Characterization and cathodic delamination behaviour, Corros. Sci., 2021, 187, 109525. [CrossRef]

- Survilienė S.; Jasulaitienė V.; Nivinskienė O.; Češūnienė A.; Effect of hydrazine and hydroxylaminophosphate on chrome plating from trivalent electrolytes, Appl. Surf. Sci., 2007, 253 6738-6743. [CrossRef]

- Zheng J-X.; Ou Yang S.Q.; Feng L.; Sun J-J.; Xuan Z-W.;. Fang J-H; In-situ Raman spectroscopic studies on electrochemical oxidation behavior of chromium in alkaline solution, J. Electroanal. Chem., 2022, 921, 116682. [CrossRef]

- Ramsey J. D., Xia L., Kendig M. W., McCreery R. L., Raman Spectroscopic Analysis of the Speciation of Dilute Chromate Solutions, Corros. Sci., 2001, 43, 1557-1572. [CrossRef]

- Ottonello G.; Zuccolini M. V.; Ab-initio structure, energy and stable Cr isotopes equilibrium fractionation of some geochemically relevant HO-Cr-Cl complexes. Geochim Cosmochim Act., 2005, 69, 851-74. [CrossRef]

- Michel G.; Machiroux R.; Raman spectroscopic investigations of the CrO42-/Cr2O72- equilibrium in aqueous solution, J. Raman Spectrosc., 1983, 14, 22. [CrossRef]

- Michel G.; Cahay R.; Raman spectroscopic investigations on the chromium(VI) equilibria part 2—species present, influence of ionic strength and CrO42--Cr2O72- equilibrium constant, J. Raman Spectrosc., 1986, 17, 79-82. [CrossRef]

- Honesty N. R., Gewirth A. A., Investigating the effect of aging on transpassive behavior of Ni-based alloys in sulfuric acid with shell-isolated nanoparticle enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SHINERS), Corros. Sci., 2013, 67, 67-74. [CrossRef]

- Dvoynenko O.; Lo S. L.; Chen Y. J.; Chen G. W; Tsai H. M.; Wang Y. L.; Wang J. K.; Speciation Analysis of Cr (VI) and Cr (III) in Water with Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. ACS omega, 2021, 6, 2052-2059. [CrossRef]

- Atkins P.; Paula J. de; Keeler J.; Physical Chemistry, Eighth Edition, Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 467. ISBN: 0-7167-8759-8.

- T. Radnai, C. Dorgai, An X-ray diffraction study of the structure of di- and trichromate ions in solutions used for electrochemical chromium deposition, Electrochim. Acta, 1992, 37 1239-1246. [CrossRef]

- Szabó M.; Kalmár J.; Ditrói T.; Bellér G.; Lente G.; Simic N.; I. Fábián; Equilibria and kinetics of chromium(VI) speciation in aqueous solution –A comprehensive study from pH 2 to 11, Inorganica Chim. Acta, 2018, 472, 295–301. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z.; Clark S. B.; Rao L.; Puzon G. J.; Xun L.; Further structural analysis of Cr(III) oligomers in weakly acidic solutions, Polyhedron, 2016, 105, 77–83. [CrossRef]

- Survilienė S.; Nivinskienė O.; Češūnienė A.; Selskis A.; Effect of Cr(III) solution chemistry on electrodeposition of chromium, J. Appl. Electrochem., 2006, 36, 649-654. [CrossRef]

- Survilienė S.; Češūnienė A.; Selskis A.; Butkienė R.; Effect of Cr(III)+Ni(II) solution chemistry on electrodeposition of CrNi alloys from aqueous oxalate and glycine baths, Int. J. Surf. Sci. Eng., 2013, 91, 24-31. [CrossRef]

- Liu L. C.; Jin L.; Yang J-Q; Yang F-Z; Tian Z-Q; Electro-reduction of Cr(III) ions under the effects of complexing agents and Fe(II) ions, J. Electroanal. Chem., 2021, 882, 114987. [CrossRef]

- García-Antón J.; Fernández-Domene R.M.; Sánchez-Tovar R.; Escrivà-Cerdán C.; Leiva-García R.; García V.; Urtiaga A.; Improvement of the electrochemical behaviour of Zn-electroplated steel using regenerated Cr (III) passivation baths, Chem. Eng. Sci., 2014, 111, 402–409. [CrossRef]

- Bates J. B.; Toth L. M.; Quist A. S.; Boyd G. E.; Vibrational spectra of crystalline, molten and aqueous potassium dichromate, Spectrochim. Acta Part A, 1973, 29, 1585-1600. [CrossRef]

- Vats V.; Melton G.; Islam M.; Krishnan V. V.; FTIR spectroscopy as a convenient tool for detection and identification of airborne Cr(VI) compounds arising from arc welding fumes, J. Hazard. Mater., 2023, 448, 130862. [CrossRef]

- NIST Chemistry WebBook, NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69, Eds. P.J. Linstrom and W.G. Mallard, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg MD, 20899. [CrossRef]

- Jmol: an open-source Java viewer for chemical structures in 3D. Available online: http://www.jmol.org/ Consulted (1, September, 2025).

| Wavenumber cm-1 | Technique | Vibration assignment | Reference |

| 398,416,417 | IR | rock | [12] |

| 492, 510sh,526,528,555 | IR | [13,15,16] | |

| 592-593 | IR | [13,14,15] | |

| 606 | IR | [20] | |

| 805,817,933,934 | IR | asymmetric stretching | [12] |

| 852,862,955,957, | IR | symmetric stretching | [12] |

| 816-817, 840, 903, 919-933, 960sh | IR | [15] | |

| 1400,1384 | IR | [13] | |

| 1621, 1623 | IR | bending | [11,13,15] |

| 2083, 2088, 2090,2098 2154sh, 2145 | IR | [11,13,14,15] | |

| 3386, 3000, 3338 | IR | stretching | [11,13,15] |

| 535, 665 | Raman | oxyhydroxide | [27] |

| 750-950 | Raman | stretching | [27] |

| 858-860 | Raman | ) mixed oxide | [25,26] |

| 987 | Raman | sulfate ions | [27] |

| 1709 | Raman | bending | [13] |

| 2095,2145 | Raman | [25] | |

| 3600-3000 | Raman | stretching | [13] |

| Wavenumber cm-1 | Vibration assignment | Reference |

| 526–540 | [13,29,30,32,34,35,39] | |

| 550-580 | [33] | |

| 550-552 | [42,43] | |

| 625 | [42] | |

| 995, 1050, 1155 | [32,34] | |

| 538-540,543 | [33,34] | |

| 255 | * | [42] |

| 446 | * | [42] |

| 800 | bound to Au | [42] |

| 848 | mixed oxide Cr(III)/Cr(VI) ** | [42,44] |

| 946 | dichromate | [42] |

| Wavenumber cm-1 | Bath or Solution | Assignee | Reference |

| 373 | Alodine | unassigned | [26] |

| 944sh, 906 | Alodine | [13,26] | |

| 1050 | Alodine | [13,26] | |

| 1648 | Alodine | bending | [13,26] |

| 2134 | Alodine | [13,26] | |

| 3600-3000 | Alodine | [13] | |

| 347-349 | Electroplated | [53,54] | |

| 364,368-398 | Electroplated | [52,53,54] | |

| 844-847 | Electroplated | [52,53,54,57] | |

| 884-891 | Electroplated | [53,54] | |

| 217,220 | [52,53] | ||

| 320 | [52] | ||

| 340 | [52] | ||

| 364,365 | [52,53] | ||

| 553 | [52] | ||

| 558 | [5][] | ||

| 772,783 | [53,5][] | ||

| 833sh | [5][] | ||

| 898 | [53] | ||

| 903,904 | [52,53] | ||

| 942,946,943 | [52,53,57] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).