Submitted:

25 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction: The Immunometabolic Paradigm of Chronic Disease

1.1. The Central Role of Leptin and the Challenge of Resistance

Molecular Mechanisms of Chronic Inflammation and the Role of miR-146a

2.1. MicroRNAs as Key Regulators

2.2. The IRAK1/TRAF6 Signaling Pathway and miR-146a Negative Feedback

Rationale and Advantages of Injectable Formulations

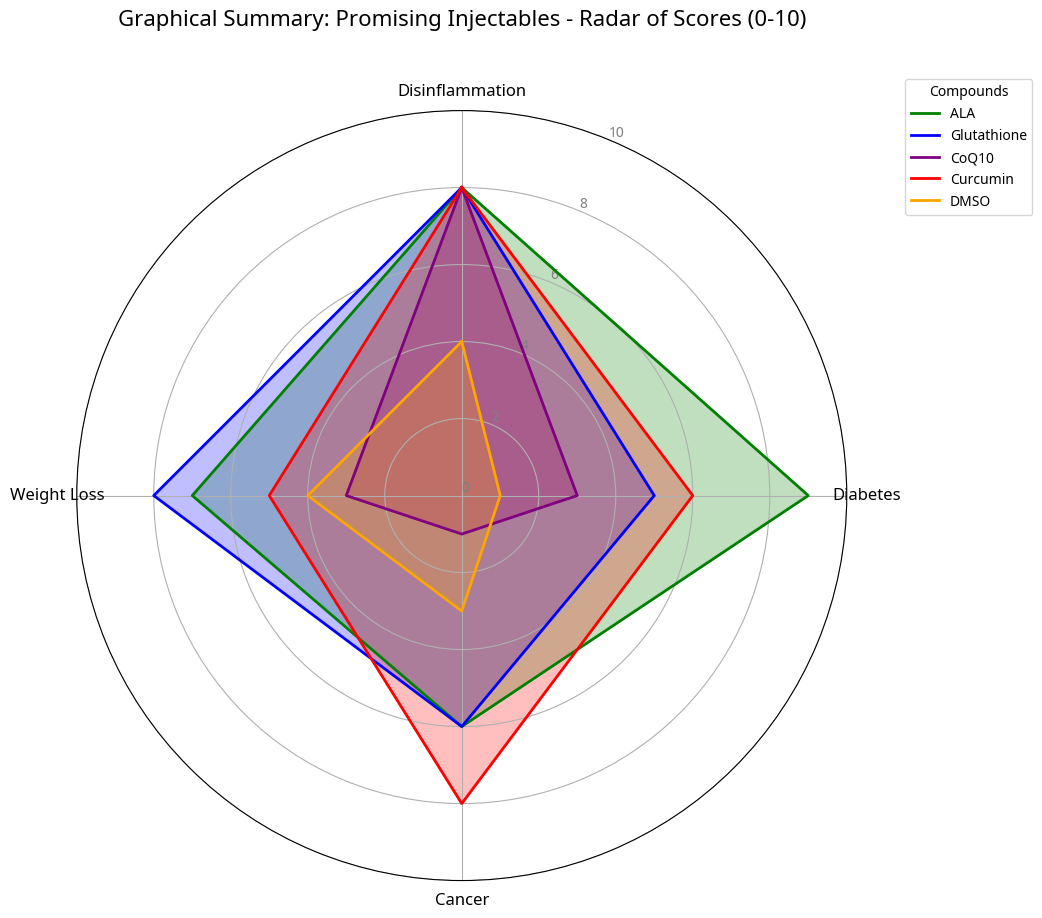

Selected and Synergistic Injectable Agents

4.1. Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO)

4.2. Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)

4.3. Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA)

4.4. Curcumin

4.5. Glutathione (GSH)

4.6. miR-146a Mimetics

Discussion and Future Perspectives

References

- Hotamisligil, GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 2006, 444, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002, 420, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen TM, Cullis PR. Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science 2004, 303, 1818–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, R. Drug delivery and targeting. Nature 1998, 392, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen TM, Cullis PR. Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science 2004, 303, 1818–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA-146a regulates signaling through the TLR pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 12481–12486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boldin MP, et al. miR-146a is a significant brake on the innate immune response. Cell 2009, 137, 1084–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 2010, 140, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 2006, 444, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. Accessed , 2025. 20 October.

- Blüher, M. Adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2013, 121, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegelman BM, Flier JS. Adipogenesis and obesity: rounding out the big picture. Cell 1996, 87, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil, GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 2006, 444, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda H, et al. MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J Clin Invest 2006, 116, 1494–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wajchenberg, BL. Adipose tissue: a vast endocrine organ. Horm Metab Res 2000, 32, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitson, SM. Sphingosine kinase 1 as a potential therapeutic target for cancer, inflammation and other diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2011, 15, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoelson SE, Herrero L, Naoki F. Inflammation and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest 2007, 117, 3562–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donath, MY. Targeting inflammation in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014, 16, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 2010, 140, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J Clin Invest 2005, 115, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneghan HM, et al. Circulating microRNAs as novel biomarkers for obesity and type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 96, E203–E209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Connell RM, Rao DS, Baltimore D. microRNA regulation of inflammatory responses. Annu Rev Immunol 2010, 28, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltiel AR, Olefsky JM. Inflammatory mechanisms linking obesity and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest 2017, 127, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 2006, 444, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoelson SE, Herrero L, Naoki F. Inflammation and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest 2007, 117, 3562–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donath, MY. Targeting inflammation in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014, 16, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 2010, 140, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J Clin Invest 2005, 115, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Connell RM, Rao DS, Baltimore D. microRNA regulation of inflammatory responses. Annu Rev Immunol 2010, 28, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneghan HM, et al. Circulating microRNAs as novel biomarkers for obesity and type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 96, E203–E209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltiel AR, Olefsky JM. Inflammatory mechanisms linking obesity and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest 2017, 127, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tili E, et al. MicroRNA-155 is a key regulator of inflammation and cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 11614–11619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA-146a regulates signaling through the TLR pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 12481–12486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA-146a regulates signaling through the TLR pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 12481–12486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boldin MP, et al. miR-146a is a significant brake on the innate immune response. Cell 2009, 137, 1084–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA-146a regulates signaling through the TLR pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 12481–12486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boldin MP, et al. miR-146a is a significant brake on the innate immune response. Cell 2009, 137, 1084–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma F, et al. miR-146a and miR-146b regulate the NF-κB pathway by targeting IRAK1 and TRAF6 in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneghan HM, et al. Circulating microRNAs as novel biomarkers for obesity and type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 96, E203–E209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Connell RM, Rao DS, Baltimore D. microRNA regulation of inflammatory responses. Annu Rev Immunol 2010, 28, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, et al. Reduced serum levels of microRNA-146a in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig 2011, 2, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, et al. Reduced serum levels of microRNA-146a in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig 2011, 2, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoba G, et al. Influence of piperine on the pharmacokinetics of curcumin in animals and human volunteers. Planta Med 1998, 64, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loftsson T, et al. Cyclodextrins in drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2005, 2, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen TM, Cullis PR. Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science 2004, 303, 1818–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, R. Drug delivery and targeting. Nature 1998, 392, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen TM, Cullis PR. Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science 2004, 303, 1818–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Hage S, et al. Nanoparticle-mediated delivery of microRNAs for cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2019, 145, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadi H, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is an ancient intercellular communication mechanism. Nat Cell Biol 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Hage S, et al. Nanoparticle-mediated delivery of microRNAs for cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2019, 145, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadi H, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is an ancient intercellular communication mechanism. Nat Cell Biol 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notman H, et al. Dimethyl sulfoxide: an organic solvent for all seasons. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2006, 27, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brayton, CF. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO): a review. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1986, 189, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Santos-Pinto J, et al. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in the treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: a review of the literature. Int Braz J Urol 2018, 44, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li YM, et al. Dimethyl sulfoxide inhibits zymosan-induced intestinal inflammation in mice. World J Gastroenterol 2015, 21, 10622–10631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brayton, CF. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO): a review. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1986, 189, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ernster L, Dallner G. Biochemical, physiological and medical aspects of ubiquinone function. Biochim Biophys Acta 1995, 1271, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, R. Coenzyme Q10: The essential nutrient. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2011, 3, 466–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, R. Coenzyme Q10: The essential nutrient. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2011, 3, 466–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen TM, Cullis PR. Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science 2004, 303, 1818–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmelzer C, et al. Coenzyme Q10 in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a status report. Biofactors 2008, 32, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer L, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid as a biological antioxidant. Free Radic Biol Med 1995, 19, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer L, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid as a biological antioxidant. Free Radic Biol Med 1995, 19, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midaoui AE, de Champlain J. Prevention of hypertension, insulin resistance, and oxidative stress by alpha-lipoic acid. Hypertension 2003, 41, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid improves endothelial function and reduces inflammatory markers in patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Med 2011, 124, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler D, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid in the treatment of diabetic polyneuropathy in Germany: current evidence from clinical trials. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2007, 115, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal BB, Harikumar KB. Potential therapeutic effects of curcumin, the anti-inflammatory agent, against neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, autoimmune and neoplastic diseases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2009, 41, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma F, et al. Curcumin-induced miR-146a inhibits cell proliferation and invasion in human glioblastoma cells. Oncol Rep 2015, 33, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoba G, et al. Influence of piperine on the pharmacokinetics of curcumin in animals and human volunteers. Planta Med 1998, 64, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen TM, Cullis PR. Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science 2004, 303, 1818–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal BB, Harikumar KB. Potential therapeutic effects of curcumin, the anti-inflammatory agent, against neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, autoimmune and neoplastic diseases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2009, 41, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishodia S, et al. Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) inhibits nuclear factor-kappaB activation through inhibition of IkappaBalpha kinase and NF-kappaB-independent mechanisms. Biochem Pharmacol 2005, 70, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meister, A. Glutathione, ascorbate, and cellular protection. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1992, 669, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witschi A, et al. The systemic availability of oral glutathione (GSH) is poor. J Clin Pharmacol 1992, 32, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhar RV, et al. Deficient synthesis of glutathione underlies oxidative stress in aging and can be corrected by dietary cysteine and glycine supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr 2011, 94, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhar RV, et al. Deficient synthesis of glutathione underlies oxidative stress in aging and can be corrected by dietary cysteine and glycine supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr 2011, 94, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhar RV, et al. Deficient synthesis of glutathione underlies oxidative stress in aging and can be corrected by dietary cysteine and glycine supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr 2011, 94, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Hage S, et al. Nanoparticle-mediated delivery of microRNAs for cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2019, 145, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadi H, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is an ancient intercellular communication mechanism. Nat Cell Biol 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Hage S, et al. Nanoparticle-mediated delivery of microRNAs for cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2019, 145, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadi H, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is an ancient intercellular communication mechanism. Nat Cell Biol 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 2006, 444, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002, 420, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen TM, Cullis PR. Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science 2004, 303, 1818–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer L, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid as a biological antioxidant. Free Radic Biol Med 1995, 19, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brayton, CF. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO): a review. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1986, 189, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allen TM, Cullis PR. Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science 2004, 303, 1818–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 2010, 140, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneghan HM, et al. Circulating microRNAs as novel biomarkers for obesity and type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 96, E203–E209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Connell RM, Rao DS, Baltimore D. microRNA regulation of inflammatory responses. Annu Rev Immunol 2010, 28, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Hage S, et al. Nanoparticle-mediated delivery of microRNAs for cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2019, 145, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadi H, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is an ancient intercellular communication mechanism. Nat Cell Biol 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA-146a regulates signaling through the TLR pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 12481–12486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boldin MP, et al. miR-146a is a significant brake on the innate immune response. Cell 2009, 137, 1084–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma F, et al. miR-146a and miR-146b regulate the NF-κB pathway by targeting IRAK1 and TRAF6 in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal BB, Harikumar KB. Potential therapeutic effects of curcumin, the anti-inflammatory agent, against neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, autoimmune and neoplastic diseases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2009, 41, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishodia S, et al. Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) inhibits nuclear factor-kappaB activation through inhibition of IkappaBalpha kinase and NF-kappaB-independent mechanisms. Biochem Pharmacol 2005, 70, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma F, et al. Curcumin-induced miR-146a inhibits cell proliferation and invasion in human glioblastoma cells. Oncol Rep 2015, 33, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernster L, Dallner G. Biochemical, physiological and medical aspects of ubiquinone function. Biochim Biophys Acta 1995, 1271, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, R. Coenzyme Q10: The essential nutrient. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2011, 3, 466–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmelzer C, et al. Coenzyme Q10 in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a status report. Biofactors 2008, 32, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer L, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid as a biological antioxidant. Free Radic Biol Med 1995, 19, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midaoui AE, de Champlain J. Prevention of hypertension, insulin resistance, and oxidative stress by alpha-lipoic acid. Hypertension 2003, 41, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid improves endothelial function and reduces inflammatory markers in patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Med 2011, 124, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meister, A. Glutathione, ascorbate, and cellular protection. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1992, 669, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witschi A, et al. The systemic availability of oral glutathione (GSH) is poor. J Clin Pharmacol 1992, 32, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhar RV, et al. Deficient synthesis of glutathione underlies oxidative stress in aging and can be corrected by dietary cysteine and glycine supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr 2011, 94, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, et al. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature 1994, 372, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Considine RV, et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med 1996, 334, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Considine RV, et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med 1996, 334, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers MG, et al. The actions of leptin and their therapeutic potential. Nature 2008, 454, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enriori PJ, et al. Increased expression of the central leptin receptor in obesity. J Clin Invest 2006, 116, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loffreda S, et al. Leptin regulates proinflammatory immune responses. FASEB J 1998, 12, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantuzzi G, Faggioni R. Leptin in the regulation of immunity, inflammation, and hematopoiesis. J Leukoc Biol 2000, 68, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jager J, et al. Hypothalamic inflammation: a key role in the pathogenesis of obesity-related diseases. FEBS Lett 2007, 581, 1987–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers MG, et al. The actions of leptin and their therapeutic potential. Nature 2008, 454, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers MG, et al. The actions of leptin and their therapeutic potential. Nature 2008, 454, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjöström L, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 2004, 351, 2683–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilding JPH, et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med 2021, 384, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr 2005, 82, 200S–205S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 2006, 444, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elisia I, et al. DMSO Represses Inflammatory Cytokine Production from Human Blood Cells and Reduces Autoimmune Arthritis. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0152538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan P, et al. Dimethyl sulfoxide suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inhibiting the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Neuroimmunol 2019, 332, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang SH, et al. Immunomodulatory effects and potential clinical applications of dimethyl sulfoxide. J Formos Med Assoc 2020, 119, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou B, et al. Creation of an Anti-Inflammatory, Leptin-Dependent Anti-obesity Agent from a Natural Product. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 718973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li YM, et al. Dimethyl sulfoxide inhibits zymosan-induced intestinal inflammation in mice. World J Gastroenterol 2015, 21, 10622–10631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao WT, et al. Antioxidant glutathione inhibits inflammation in synovial fibroblasts by suppressing the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway. Aging (Albany NY) 2021, 13, 19438–19451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvagno F, et al. The Role of Glutathione in Protecting against the Severe Inflammatory Response Triggered by COVID-19. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diotallevi M, et al. Glutathione Fine-Tunes the Innate Immune Response toward Antiviral Pathways in a Macrophage Cell Line. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain SK, et al. Glutathione stimulates vitamin D regulatory and glucose-metabolism genes, lowers oxidative stress and inflammation, and increases 25-hydroxy-vitamin D levels in blood of obese mice. Antioxid Redox Signal 2018, 29, 1626–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santacroce G, et al. Glutathione: Pharmacological aspects and implications for clinical use. Pharmacol Res 2023, 190, 106720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu M, et al. Regulation mechanism of curcumin mediated inflammatory response through miR-146a. J Inflamm Res 2025, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, et al. Induction of microRNA-146a is involved in curcumin-mediated enhancement of temozolomide cytotoxicity against human glioblastoma. Mol Med Rep 2015, 12, 5461–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao W, et al. Curcumin prevents high fat diet induced insulin resistance and obesity via attenuating lipogenesis in liver and inflammatory pathway in adipocytes. PLoS One 2012, 7, e28784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, PG. Curcumin and obesity. Biofactors 2013, 39, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He Y, et al. Curcumin, Inflammation, and Chronic Diseases: How Are They Linked? Molecules 2015, 20, 9183–9213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tibullo D, et al. Biochemical and clinical relevance of alpha lipoic acid: antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity, molecular pathways and therapeutic potential. Inflamm Res 2017, 66, 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghighatdoost F, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid effect on leptin and adiponectin concentrations: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2020, 76, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, et al. The immunomodulatory effect of alpha-lipoic acid in obesity. Mediators Inflamm 2019, 2019, 8086257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhiyenko V, et al. The impact of alpha-lipoic acid on insulin resistance and inflammatory parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiac autonomic neuropathy. Am J Int Med 2020, 8, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunina NV, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid as a means of influence on systemic inflammation in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with prior myocardial infarction. J Med Life 2020, 13, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi B, et al. Insights on the Use of α-Lipoic Acid for Therapeutic Purposes. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casagrande D, et al. Mechanisms of action and effects of the administration of coenzyme Q10 on metabolic syndrome. J Acupunct Meridian Stud 2018, 11, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantle D, Heaton RA, Hargreaves IP. Coenzyme Q10 and Degenerative Disorders. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Camacho JD, et al. Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation in Aging and Disease. Front Physiol 2018, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez-Mariscal FM, et al. Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation for the Reduction of Oxidative Stress: Clinical Implications in the Treatment of Chronic Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 7870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zozina VI, et al. Coenzyme Q10 in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases: current state of the problem. Curr Cardiol Rev 2018, 14, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholami M, Khosrowbeygi A. Review on the mechanisms of the effects of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on serum levels of leptin and adiponectin. Rom J Diabetes Nutr Metab Dis 2023, 30, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaolapo OJ, Omotoso SA, Onaolapo AY. Anti-Inflammatory, anti-oxidant, and anti-lipaemic effects of daily dietary coenzyme-Q10 supplement in a mouse model of metabolic syndrome. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem 2021, 20, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalenikova EI, et al. Prospects of Intravenous Coenzyme Q10 Administration in Clinical Practice. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu Z, et al. Coenzyme Q10 improves lipid metabolism and protects against diet-induced hepatic steatosis in mice. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 8899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turunen M, Olsson J, Dallner G. Metabolism and function of coenzyme Q. Biochim Biophys Acta 2004, 1660, 171–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).