Submitted:

01 November 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: The Immunometabolic Paradigm of Chronic Disease

1.1. Dysfunction of the Leptin-Hypothalamic Axis and Central Resistance

1.2. The Rationale for Multidimensional Injectable Therapy

- 1

- Central Epigenetic Modulation: Through miR-146a mimetics, restoring the inflammatory negative feedback in the hypothalamus and AT.

- 2

- Suppression of Systemic Inflammation: With DMSO and Curcumin, inhibiting the NF-κB pathway and the NLRP3 inflammasome.

- 3

- Combating Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction: With CoQ10, ALA, and GSH, optimizing the electron transport chain and cellular antioxidant capacity.

2. Molecular Mechanisms and Modulation by miRNA Mimetics and Nutraceuticals

2.1. MicroRNAs as Key Regulators: The miR-146a Circuit

2.2. Resveratrol, Sirtuins, and Epigenetic Modulation

2.3. Curcumin and NF-κB Inhibition

3. Pharmacokinetic Justification and Injectable Nanomedicine

3.1. Nanomedicine for the Delivery of miR-146a Mimetics

- 4

- Protection: Protecting miRNA molecules from degradation by nucleases in the plasma.

- 5

- Targeting: Optimizing delivery to the target tissue (e.g., adipose tissue, immune cells, hypothalamus).

- 6

- Permeability: Facilitating passage through biological barriers, such as the blood-brain barrier (BBB) for the hypothalamus [54].

- Lipid Nanocarriers (LNCs): These are the most advanced delivery platform for nucleic acids, including mRNA vaccines. LNCs can be modified with ligands (e.g., peptides or antibodies) that bind to specific receptors on AT macrophages or BBB endothelial cells [55]. Preclinical studies demonstrate that LNCs can effectively deliver miR-146a, reducing inflammation and improving insulin sensitivity in animal models [56].

- Exosomes: Naturally occurring extracellular vesicles that possess innate mechanisms for intercellular communication and the ability to cross the BBB [57]. Exosomes loaded with miR-146a, derived from mesenchymal stem cells, have been shown to protect against pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction and alleviate diabetic complications, acting as a natural and highly efficient delivery system [58,59].

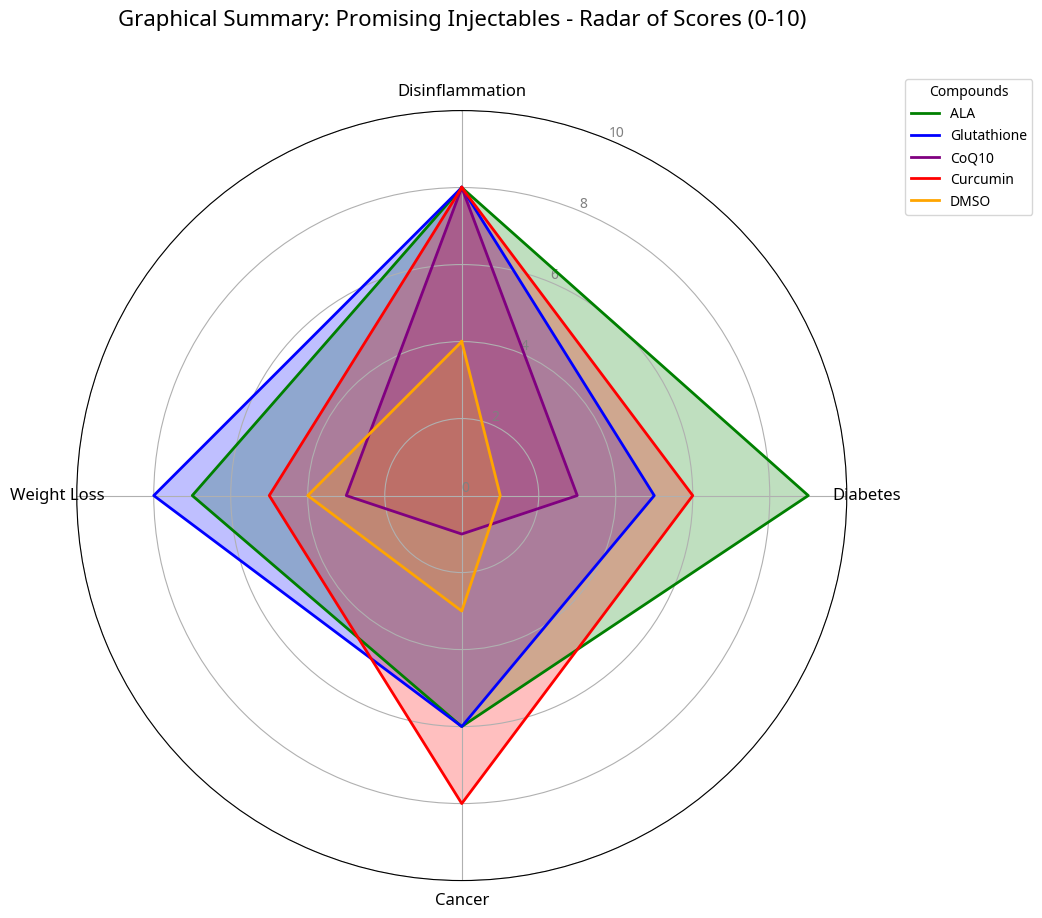

4. Selected Injectable Agents: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications

4.1. Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO): Optimization and Safety

4.2. Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) and Mitochondrial Optimization

- Mitochondrial Optimization: Mitochondrial dysfunction is a hallmark of insulin resistance and LGCI [70]. CoQ10 is crucial for ATP production and the stability of the mitochondrial membrane.

4.3. Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA) and Antioxidant Regeneration

4.4. Glutathione (GSH): The Master Antioxidant

5. Discussion: Comparison of the Integrated Approach with Gold-Standard Therapies

5.1. Challenges and Next Steps (Addition)

- 7

- Injectable Formulation Validation: Curcumin and Resveratrol, despite their synergy, require stable and safe injectable nano-liposomal formulations, with robust toxicity and pharmacokinetic data in humans [81].

- 8

- DMSO Safety: The safety and maximum tolerated dose of injectable DMSO, at therapeutic concentrations for LGCI, must be established in phase I clinical trials, outside the context of cryopreservation [67].

- 9

- 10

- Synergistic Efficacy: Proving the synergistic efficacy of this combination in a randomized, controlled clinical trial is the final step to validate the immunometabolic hypothesis.

6. Conclusion

References

- Hotamisligil, G.S. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 2006, 444, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coussens, L.M.; Werb, Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002, 420, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.M.; Cullis, P.R. Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science 2004, 303, 1818–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, L.; et al. Alpha-lipoic acid as a biological antioxidant. Free Radic Biol Med 1995, 19, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runtsch, M.C.; et al. Anti-inflammatory microRNA-146a protects mice from diet-induced metabolic disease. PLoS Genet 2019, 15, e1007970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taganov, K.D.; et al. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA-146a regulates signaling through the TLR pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 12481–12486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldin, M.P.; et al. miR-146a is a significant brake on the innate immune response. Cell 2009, 137, 1084–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grivennikov, S.I.; et al. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 2010, 140, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneghan, H.M.; et al. Circulating microRNAs as novel biomarkers for obesity and type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 96, E203–E209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2021). Obesity and overweight. Acesso em 28 de Outubro de 2025.

- Brayton, C.F. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO): a review. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1986, 189, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gesta, S.; et al. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007, 92, 859–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltiel, A.R.; Olefsky, J.M. Inflammatory mechanisms linking obesity and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest 2017, 127, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantuzzi, G. Adipose tissue, adipokines, and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005, 116, 940–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouchi, N.; et al. Adiponectin and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2011, 123, 1913–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoelson, S.E.; et al. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 2007, 117, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Moschen, A.R. Adipocytokines and immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2010, 10, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianna, G.F.; et al. The role of microRNAs in the link between obesity and cancer. Obes Rev 2018, 19, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wensveen, F.M.; et al. The metabolic syndrome, the immune system, and adipose tissue inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol 2015, 33, 371–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donath, M.Y. Targeting inflammation in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014, 16 Suppl 1, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneghan, H.M.; et al. Circulating microRNAs as novel biomarkers for obesity and type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 96, E203–E209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. MicroRNA-155 is involved in the pathogenesis of obesity-related insulin resistance. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 26915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature 1994, 372, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flier, J.S. Obesity wars: molecular targets of a modern epidemic. Cell 2004, 116, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Considine, R.V.; et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med 1996, 334, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, M.G.; et al. The actions of leptin and their therapeutic potential. Nature 2008, 454, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enriori, P.J.; et al. Increased expression of the central leptin receptor in obesity. J Clin Invest 2006, 116, 2956–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loffreda, S.; et al. Leptin regulates proinflammatory immune responses. FASEB J 1998, 12, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, J.P.; et al. Obesity is a neuroendocrine disease. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey, K.A.; et al. Hypothalamic proinflammatory lipid metabolism links obesity to impaired actue insulin action. Cell Metab 2009, 10, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jais, A.; Brüning, J.C. Hypothalamic inflammation in obesity and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest 2017, 127, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, G.R.; Lehar, J. Exploring combinatorial chemical space for drug discovery. Nat Chem Biol 2009, 5, 640–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.; et al. Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises. Mol Pharm 2007, 4, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupaimoole, R.; Slack, F.J. MicroRNA therapeutics: towards a new generation of medicines. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2017, 16, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheedy, F.J.; et al. Negative regulation of TLR4-induced NF-κB signaling by microRNA-146a in human monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 10526–10531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, R.M.; et al. MicroRNA-146a and microRNA-155 can cooperate to suppress specific innate immune signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 14437–14442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runtsch, M.C.; et al. Anti-inflammatory microRNA-146a protects mice from diet-induced metabolic disease. PLoS Genet 2019, 15, e1007970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffari, M.; et al. Association of MicroRNA-146a with Type 1 and 2 Diabetes and Their Related Complications. J Diabetes Res 2023, 2023, 2587104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barutta, F.; et al. MicroRNA 146a is associated with diabetic complications and can be modulated by anti-inflammatory treatments. Transl Med 2021, 19, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roganović, J.; et al. Downregulation of microRNA-146a in diabetes, obesity and hypertension. J Physiol Biochem 2021, 77, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; et al. Nanoparticle–microRNA-146a-5p polyplexes ameliorate diabetic peripheral neuropathy by modulating inflammation and apoptosis. Biomaterials 2019, 218, 119330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baur, J.A.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: the in vivo evidence. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2006, 5, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howitz, K.T.; et al. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature 2003, 425, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagouge, M.; et al. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha. Cell 2006, 127, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanno, M.; et al. Induction of the mammalian Sirtuin SIRT1 by oxidative stress and its role in regulating antioxidant gene expression. Cell 2007, 130, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; et al. Synergistic anti-inflammatory effects and mechanisms of the combination of resveratrol and curcumin in human vascular endothelial cells and rodent aorta. J Nutr Biochem 2022, 103, 108960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csaki, C.; et al. Synergistic chondroprotective effects of curcumin and resveratrol in human articular chondrocytes: inhibition of IL-1β-induced NF-κB-mediated inflammation and catabolism. Arthritis Res Ther 2009, 11, R81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, B.B.; Harikumar, K.B. Potential therapeutic effects of curcumin, the anti-inflammatory agent, against neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, pulmonary, metabolic, autoimmune and neoplastic diseases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2009, 41, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobin, C.; et al. Curcumin blocks cytokine-mediated NF-kappa B activation and proinflammatory gene expression by inhibiting an inhibitory factor I-kappa B kinase. J Immunol 1999, 163, 3474–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; et al. Curcumin modulates miR-146a and miR-155 expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Clin Immunol 2018, 38, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishodia, S.; et al. The role of curcumin in cancer therapy. Curr Probl Cancer 2005, 29, 7–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jager, R.; et al. Comparative absorption of three commercially available curcumin formulations in healthy volunteers. Nutr J 2014, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; et al. Exosomes from adipose tissues derived mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing MicroRNA-146a alleviate diabetic osteoporosis in rats. Cell Mol Bioeng 2022, 15, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenchov, R.; et al. Lipid Nanoparticles—From Liposomes to mRNA Vaccine Technology. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 16982–17015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; et al. Nanoparticle-mediated delivery of microRNA-146a to the brain for the treatment of neuroinflammation. Biomaterials 2018, 162, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Andaloussi, S.; et al. Exosomes for targeted drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2013, 65, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; et al. From Bone Remodeling to Wound Healing: An miR-146a-5p-Loaded Nanocarrier Targets Endothelial Cells to Promote Angiogenesis. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2024, 16, 20078–20090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing microRNA-146a inhibit inflammation and promote repair in a rat model of acute lung injury. Stem Cell Res Ther 2019, 10, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jais, A.; Brüning, J.C. Hypothalamic inflammation in obesity and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest 2017, 127, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, N.C.; et al. Dimethyl sulfoxide: an exceptional solvent and a versatile biological and pharmacological tool. Life Sci 2003, 74, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brayton, C.F. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO): a review. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1986, 189, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; et al. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation in murine macrophages. Inflammation 2019, 42, 1801–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latz, E.; et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nat Rev Immunol 2013, 13, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, J.P.; et al. Obesity is a neuroendocrine disease. J Clin Invest 2012, 122, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thackaberry, E.A.; et al. Tolerability and recommended solvent dose limits for common pharmaceutical vehicles in preclinical toxicity studies. Crit Rev Toxicol 2014, 44, 701–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, B.K.; et al. Adverse reactions of dimethyl sulfoxide in humans: a systematic review. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2019, 57, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernster, L.; Dallner, G. Biochemical, physiological and medical aspects of ubiquinone function. Biochim Biophys Acta 1995, 1271, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littarru, G.P.; Tiano, L. Bioenergetic and antioxidant properties of coenzyme Q10: new developments and therapeutic perspectives. Arch Biochem Biophys 2007, 463, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowell, B.B.; Shulman, G.I. Mitochondrial dysfunction and type 2 diabetes. Science 2017, 357, 1087–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R. Coenzyme Q10: The essential nutrient. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2011, 3, 466–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, L.; et al. Effects of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on inflammatory markers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol Res 2017, 119, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghibu, S.; et al. Alpha-lipoic acid: a new therapeutic option for metabolic syndrome and related diseases. J Med Life 2009, 2, 382–387. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, D.; et al. Efficacy and safety of intravenous high-dose alpha-lipoic acid in the treatment of symptomatic diabetic polyneuropathy. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 2268–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahm, J.R.; et al. Alpha-lipoic acid improves endothelial function and reduces inflammatory markers in patients with type 2 diabetes. Metabolism 2008, 57, 1547–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; et al. Glutathione metabolism and its implications for health. J Nutr 2004, 134, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witschi, A.; et al. The systemic availability of oral glutathione (GSH) is poor. J Clin Pharmacol 1992, 32, 1014–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröge, W.; Breitkreutz, R. Glutathione and immune function. Proc Nutr Soc 2000, 59, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding, J.P.H.; et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med 2021, 384, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff, A.M.; et al. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. N Engl J Med 2022, 387, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, R.; et al. Resveratrol-loaded solid lipid nanoparticle improves insulin resistance through targeting expression of SNARE proteins in adipose and muscle tissue in rats with type 2 diabetes. Nanoscale Res Lett 2019, 14, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madsen, B.K.; et al. Adverse reactions of dimethyl sulfoxide in humans: a systematic review. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2019, 57, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; et al. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation in murine macrophages. Inflammation 2019, 42, 1801–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenchov, R.; et al. Lipid Nanoparticles—From Liposomes to mRNA Vaccine Technology. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 16982–17015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | Proposed Integrated Approach (Injectables) | GLP-1/GIP Agonists (e.g., Semaglutide) | Bariatric Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Mechanism of Action | Direct modulation of LGCI (via miR-146a, DMSO, Curcumin, Resveratrol), combating oxidative stress, and mitochondrial optimization. | Increased insulin secretion (glucose-dependent), delayed gastric emptying, appetite suppression (incretin action). | Gastric restriction and/or malabsorption; intestinal hormonal modulation (e.g., increased GLP-1, PYY). |

| Weight Loss Efficacy | Hypothetical. Efficacy is expected by restoring leptin sensitivity and reducing hypothalamic inflammation, addressing the root cause of central dysfunction. | High. Significant weight loss (up to 20-25% of body weight with new generations of dual agonists). | Very High. Sustained weight loss of 25-35%. |

| Action on Chronic Inflammation | Direct and Multi-target. Main focus on suppressing the NF-κB pathway, NLRP3 inflammasome, and restoring miR-146a. | Indirect. Reduction of inflammation secondary to weight loss and metabolic improvement. | Indirect. Reduction of inflammation secondary to weight loss and beneficial alteration of the gut microbiota. |

| Restoration of Leptin Sensitivity | Direct. Inclusion of agents (DMSO, miR-146a, Resveratrol) targeting hypothalamic neuroinflammation and central signaling. | Indirect. Improvement secondary to weight loss, with no direct molecular target on hypothalamic inflammation. | Indirect. Improvement secondary to weight loss. |

| Clinical Status | Hypothetical/Translational Proposal. Requires rigorous validation in preclinical and phase I/II clinical trials. | Gold-Standard. Approved and widely used for the treatment of obesity and T2DM. | Gold-Standard. Established treatment for severe obesity and refractory T2DM. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).