1. Introduction

β-Diketonate ligands (R

1COCHR

3COR

2) are among the most versatile and widely exploited classes of precursors for metal–organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD) of thin films. Their tunable volatility, coordination flexibility, and favorable decomposition behavior make them especially suited for gas-phase delivery of metal centers. For example, fluorinated β-diketonate complexes M(tfac)

2(TMEDA) (M = Fe, Ni, Cu, Zn) have recently been demonstrated as effective MOCVD precursors to deposit both metal and metal oxide films, with controlled film quality (i.e., well-oriented ZnO thin films) and composition, thereby highlighting the critical role of ligand design in optimizing volatility and film quality [

1]. Previous results from our group have highlighted how γ-substitution (R

3 nature) can be exploited to tune the stability and reactivity (degradation mechanism) of titanium β-diketonate precursors, paving the way for the rational design of improved molecules for TiO

2 thin-film deposition [

2].

ZnO is an attractive target material due to its wide bandgap, biocompatibility, piezoelectric properties, and relevance in microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), actuators, sensors, photonics, and solar cells. β-Diketonate ligands (R

1COCHR

3COR

2) are particularly suitable for this purpose because they act as chelating ligands that promote electron delocalization when coordinated to metal ions. By forming donor–π–acceptor complexes with Zn

2+ ions, these ligands facilitate low-energy ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) [

3], enhancing multiphoton absorption and enabling controlled laser-induced material growth. Structural versatility can be achieved by modifying the R

1, R

2, and R

3 substituents, providing additional control over precursor properties.

The development of next-generation micro- and nanotechnologies for microelectronic, photonic, and MEMS/NEMS components requires fabrication processes that operate in three dimensions, are flexible, fast, and parallel, and scalable, while minimizing the use of environmentally costly elements [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Conventional micro synthetic techniques, however, are largely limited to 2.5D processing and cannot achieve true 3D structuring at the sub-micrometer scale [

9,

10,

11,

12]. High-throughput additive manufacturing is often restricted either to feature sizes of tens of micrometers or to organic polymers, limiting its applicability for functional inorganic materials [

13,

14,

15].

Ultrashort laser excitation induces complex coherent superpositions of excited states that evolve on femtosecond timescales through internal conversion or direct relaxation to the ground state, often accompanied by excess vibrational energy. These ultrafast processes depend on the metal center, ligand type, and excitation conditions, and can be tuned by adjusting the coordination environment to control solubility, electronic and optical properties, and decomposition pathways. Chemical deposition using femtosecond laser pulses offers a promising approach to achieve precise 3D growth of inorganic materials [

16]. This approach requires the design of molecular precursors that efficiently absorb multiphotonic excitation and undergo controlled ligand degradation. Nonlinear photolysis enables progressive growth of inorganic materials at sub-micrometer scales, providing a flexible route for 3D fabrication [

17]. The main challenges remain: (i) designing precursor molecules with high multiphoton absorption and efficient ligand decomposition, and (ii) understanding the ultrafast photo physics and photochemistry underlying the reactions [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

To date, such ligand architectures have not been systematically explored with ultrafast spectroscopic techniques. In this study, we report the synthesis and full characterization of a novel series of homoleptic and heteroleptic β-diketonate Zn(II) complexes. Their structural, thermal, and electronic properties were examined by X-ray diffraction, NMR, UV–Vis spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, and thermal analysis. In addition, femtosecond spectroscopy was employed to probe their excited-state dynamics, providing new insights into the photophysical behaviour of these complexes. We further investigate the influence of different ancillary ligands on stability, optical properties, and excited-state relaxation pathways. This comprehensive study establishes important structure–property relationships for Zn(II) β-diketonates, laying the groundwork for their future application as ZnO precursors and functional materials.

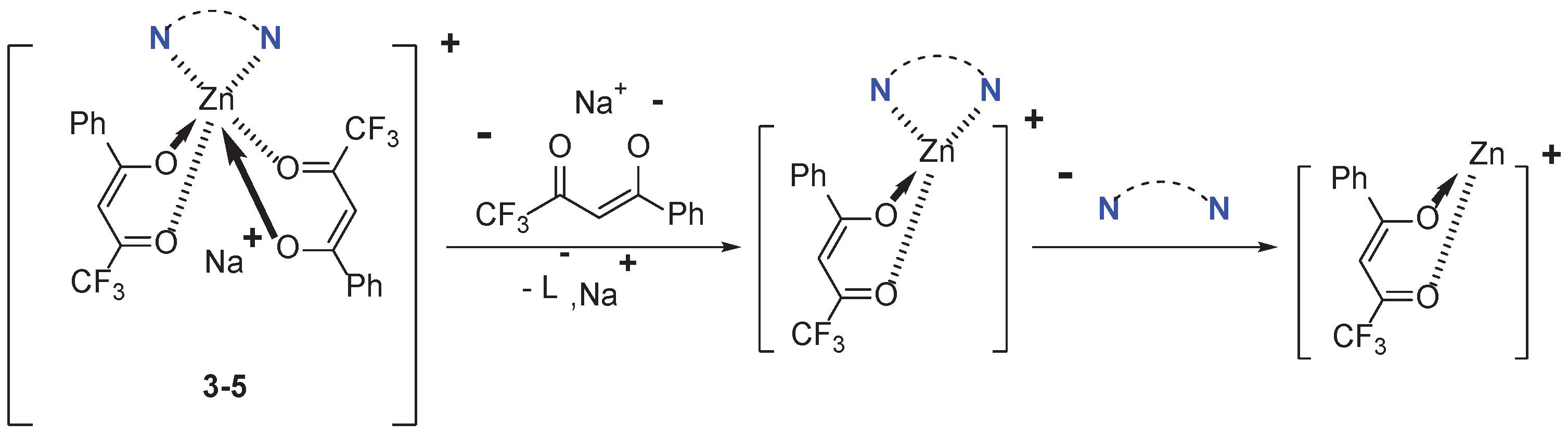

3. Discussion

In this work, we synthesized a novel family of Zn β-diketonate complexes, and report their photophysical properties for the first time with respect to potential laser deposition applications. Our study focuses on the characterization of transient species; their specific photoreactivity will be detailed in a forthcoming manuscript.

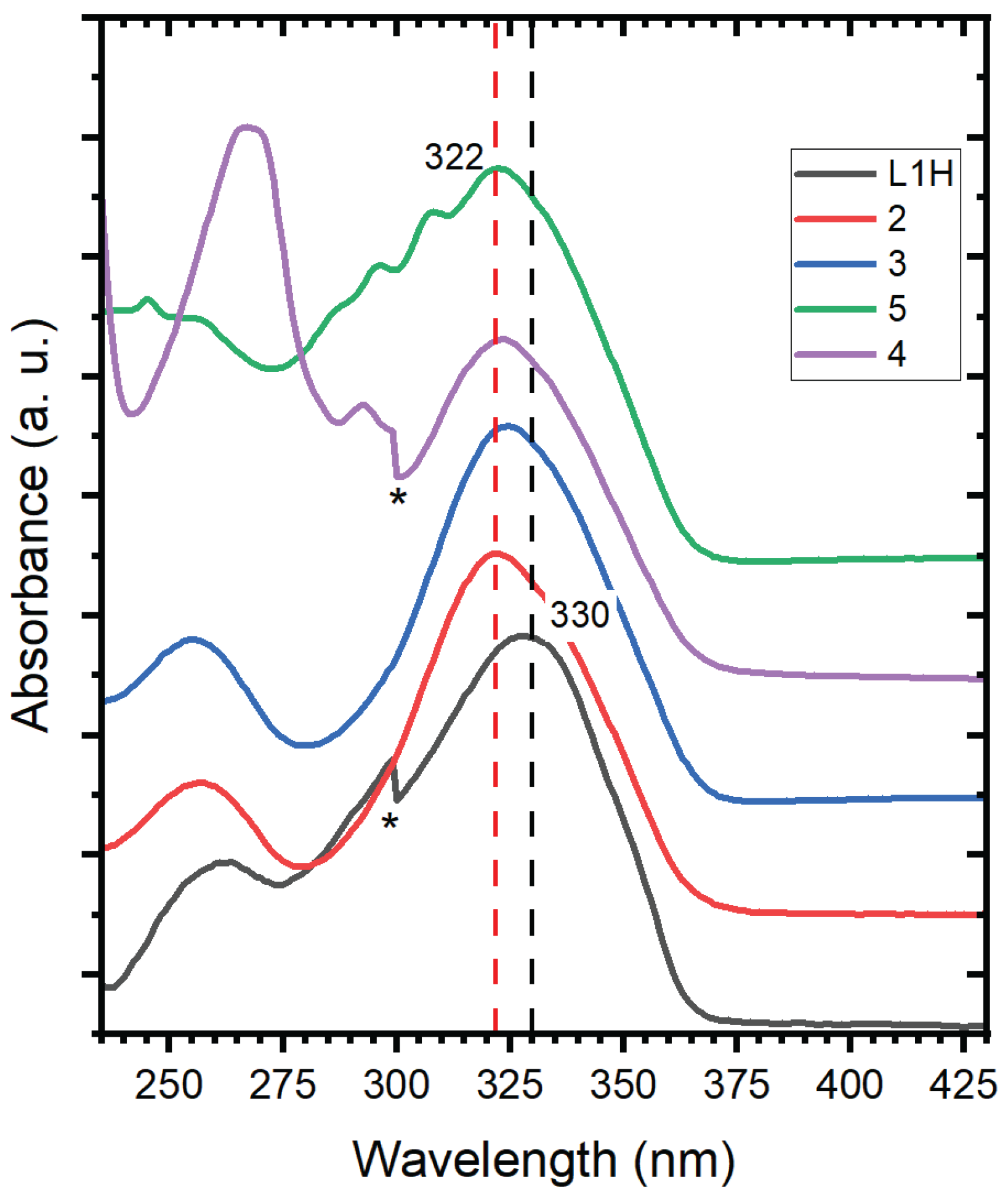

From the UV–Vis absorption spectra, it is evident that the lowest optically allowed electronic transition is the same for

L1H and complexes

1–5, irrespective of the nature of the ancillary ligand. This demonstrates that the chelated ring constitutes the main chromophore responsible for the optical transition, and that the first populated excited state upon absorption of a UV photon around 320 nm corresponds to the π→π* state of the

L1H ligand. The ultrafast photodynamics observed for

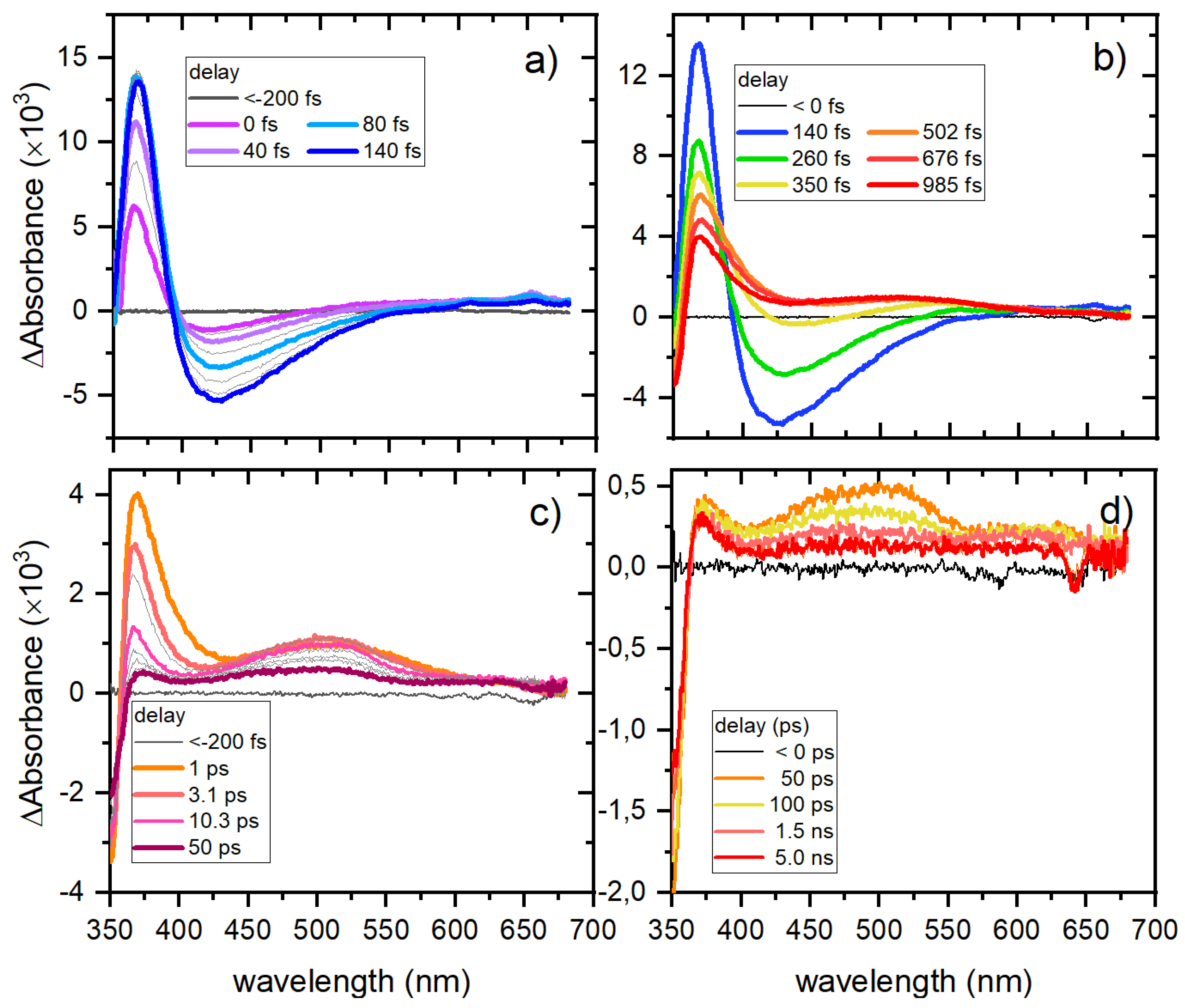

L1H are in good agreement with previous experimental and theoretical studies on β-diketones [

21]. The bright π→π* state corresponds to the S

2 state, which undergoes internal conversion to the S

1 n→π* state and to a hot S

0 ground state in less than 1 ps. Internal conversion to the ground state constitutes the main relaxation pathway, while the small absorption band observed on the picosecond timescale arises from a minor contribution of intersystem crossing (ISC) to the triplet state and the formation of a trans isomer. After several hundred picoseconds, the ground state is fully recovered.

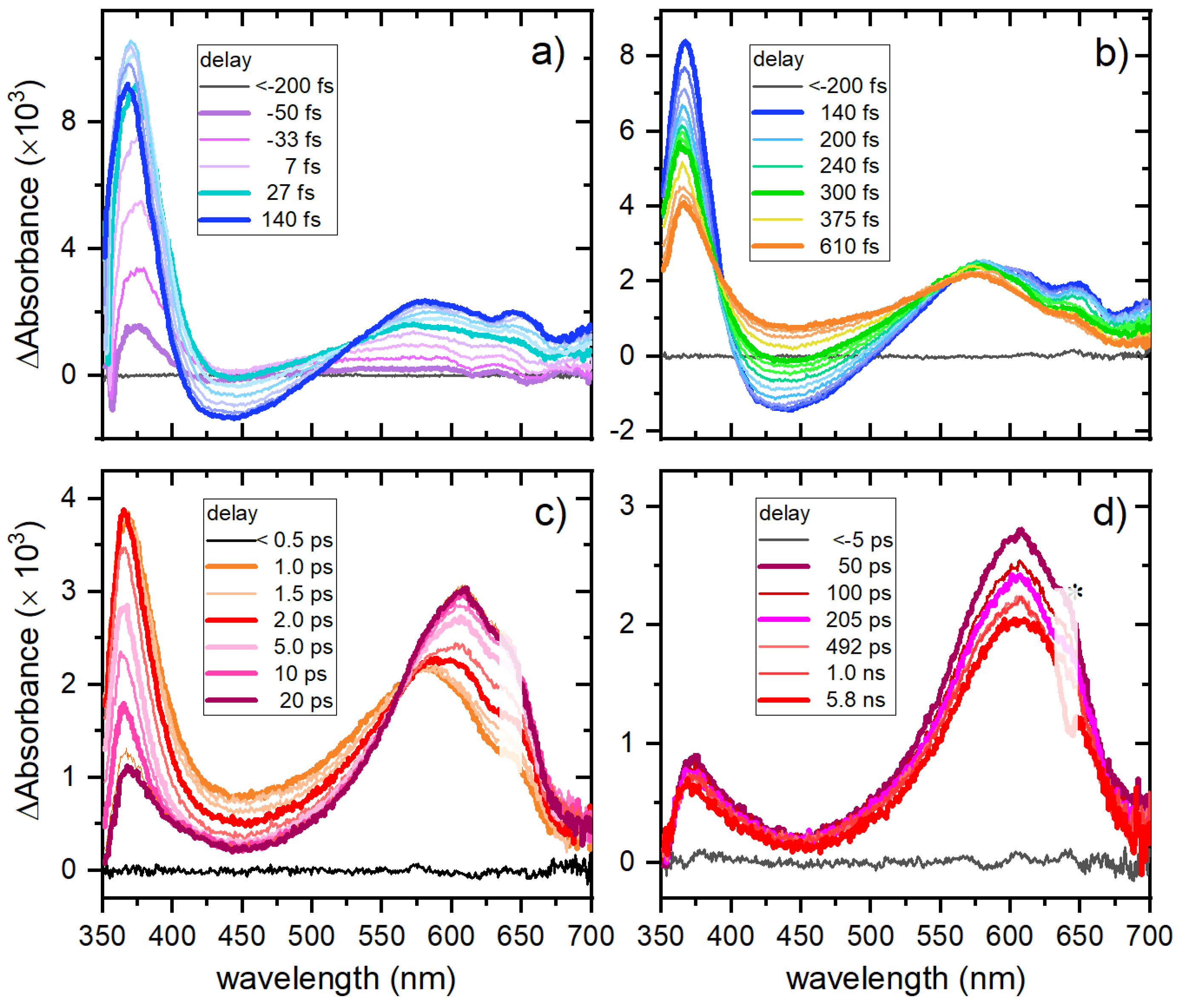

Chelation of Zn significantly modifies the photodynamics of the L1H moiety, even though the first populated state remains a π→π* state. The most notable effect of chelation is the hindrance of ultrafast internal conversion to the ground state due to the increased structural rigidity, resulting in a sequence of three observable transient species. Upon light absorption, the S2 π→π* state is first populated, followed by ultrafast internal conversion to the S1 state, which retains n→π* character but exhibits a stronger and red-shifted ESA band compared to L1H. This new ESA feature indicates that the chelated ring remains intact and may also involve a ligand-to-metal charge transfer contribution. The S1 state subsequently evolves into a new state, assigned to the triplet state of the β-diketonate ligand.

Theoretical calculations are needed to clarify the exact contributions of the n→π*, charge-transfer, or ligand-field character, but our data demonstrate that the ancillary ligands are not significantly involved. While for L1H the main photophysical pathway is ultrafast internal conversion to the ground state, in complexes 1–5 the majority of the absorbed energy remains trapped in the excited triplet state. This is a remarkable property, as the triplet state of the ketones is chemically active and can, for example, undergo hydrogen abstraction from the solvent leading to a potential pathway for complex destabilization. The photo reactivity of these compounds will be discussed in a separate study.

Overall, these results highlight the key role of Zn chelation in modulating the photo dynamics of β-diketonates, providing longer-lived excited states that may be advantageous for applications in laser deposition. The combination of ultrafast spectroscopy and preliminary computational analysis offers a coherent picture of the transient species involved and sets the stage for further studies aimed at understanding their photochemical behaviour and potential reactivity pathways.

4. Materials and Methods

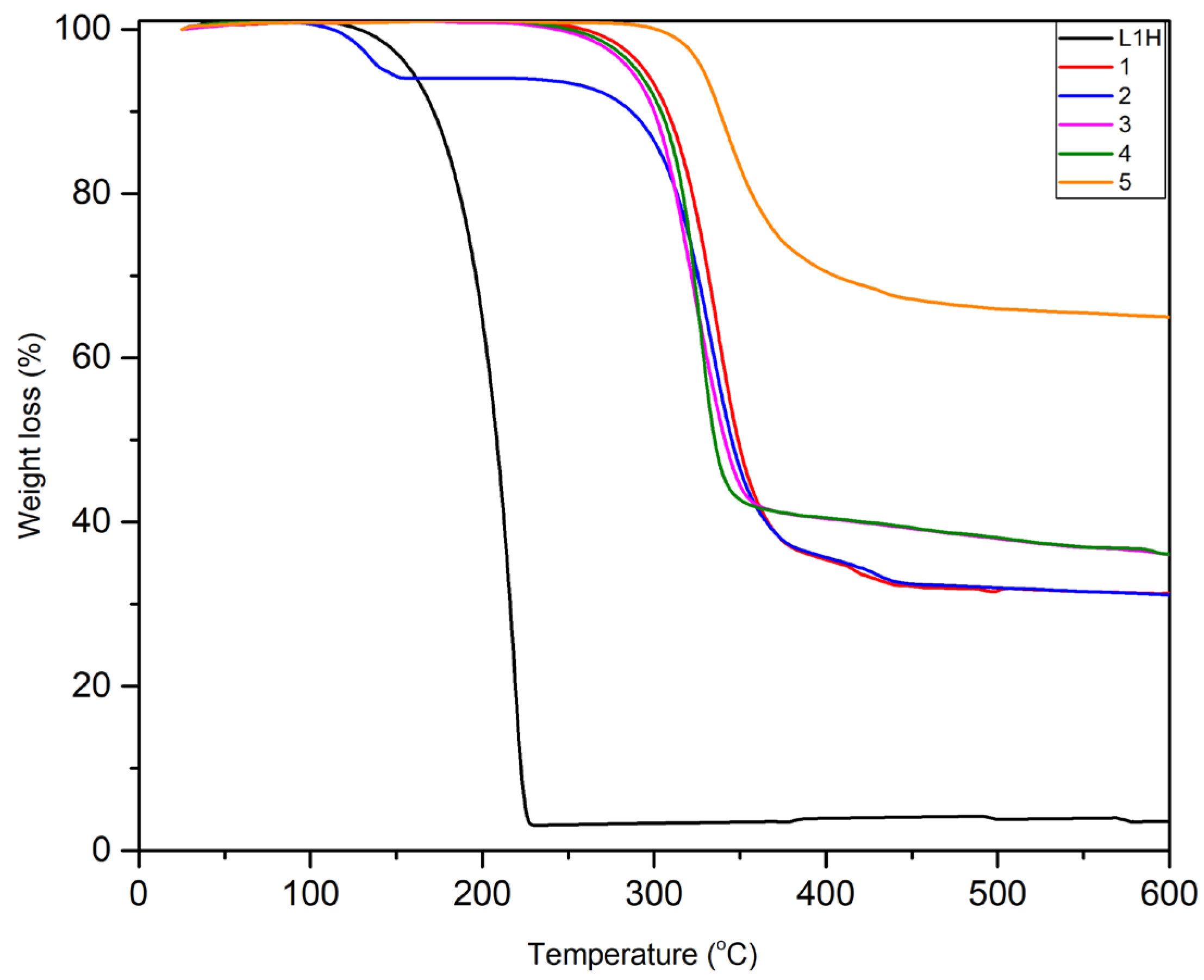

The FT-infrared spectra (FT-IR) of the ligand and complexes were recorded using a Nicolet iS50 FT-IR spectrometer. UV-visible absorbance measurements were performed using Thermo Scientific Evolution 220 dual-beam spectrophotometer at a scan rate 1 nm / sec.

1H and

19F NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker SampleXpress 300 MHz spectrometer (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, m = multiplet). ESI/FAB mass spectra were recorded using an Impact II mass spectrometer by electrospray ionization (ESI); FAB conditions are indicated in the Supporting Information. Thermal behavior was analyzed using a METTLER TOLEDO TGA 2 Star System under a nitrogen atmosphere at a scan rate of 5 K min

−1. Femtosecond transient absorption measurements have been carried out using the set-up described in [

22]. Briefly, the system consists of a 5 W Astrella laser delivering 35 fs pulses used to seed an OPA and a Helios UV–vis transient absorption spectrometer. All the measurements were performed in solution using a 1 mm flowing cell.

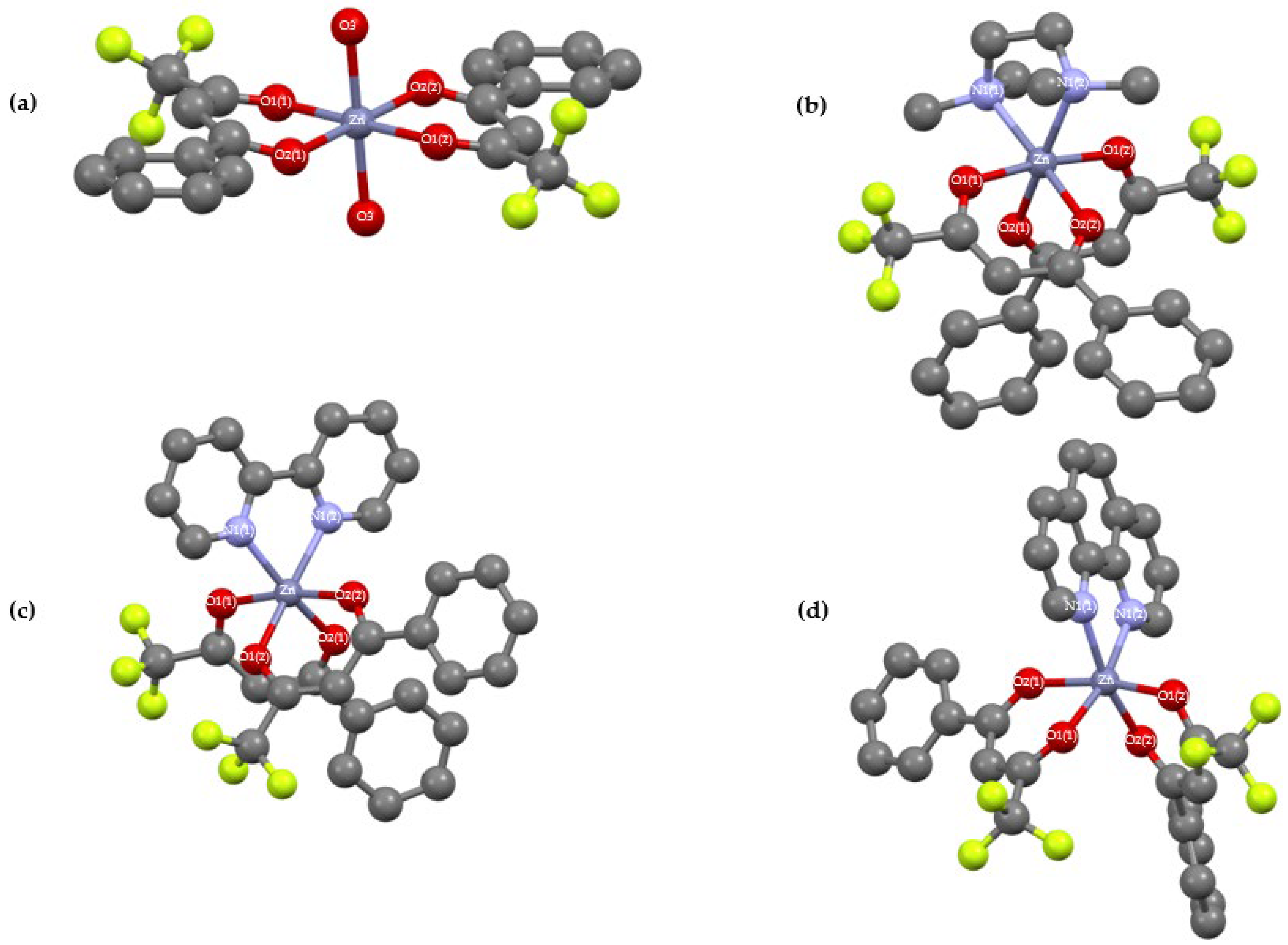

Single crystal X-ray diffraction data of complexes 2-5 were measured using ω scans with Mo Kα radiation at 100 K. The diffraction pattern was indexed and the total number of runs and images was based on the strategy calculation from the program CrysAlisPro system (CCD 43.125a 64-bit (release 04-06-2024)). The maximum resolution that was achieved was Θ = 30.615° (0.70 Å). The unit cell was refined using CrysAlisPro 1.171.43.124a (Rigaku OD, 2024) on 20645 reflections, 64% of the observed reflections. Data reduction, scaling and absorption corrections were performed using CrysAlisPro (Rigaku Oxford Diffraction). A multi-scan absorption correction (SCALE3 ABSPACK) was applied. The dataset is 100% complete to 30.615° in θ. The absorption coefficient (μ) is 0.945 mm−1 at λ = 0.71073 Å. Minimum and maximum transmissions are 0.768 and 1.000. Data were collected at 100 K. Cell parameters and orientation matrices were determined from 36 frames of 2 D diffraction images. The data were corrected for Lorentz and polarization effects.

ZnEt2 (CAS no: 557-20-0) in toluene solution (2 M) and 4,4,4-trifluoro-1-phenylbutane-1,3-dione (L1H) (CAS no: 720-94-5) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific and Merck-Sigma Aldrich companies, respectively and used without further purification. Nitrogen-based Lewis bases : N,N,N’,N’-Tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA, CAS no: 612-00-3), 2,2’ bipyridine (bipy, CAS no: 366-18-7) and 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (o-phen, CAS no: 66-71-7) were purchased from Merck-Sigma Aldrich and Alfa Aesar companies, respectively, and used without any further purification.

L1H : C10H7O2F3. 216 g.mol-1. 1H NMR (MHz, CD2Cl2, δ ppm) : 7.97 (2H, d, J = 7.23 Hz, HCar) ; 7.66 (1H, t, J = 7.38 H, HCar) ; 7.53 (2H, t, J = 7.7 Hz, HCar) ; 6.62 (1H, s, -CH-). 19F NMR (CD2Cl2, δ ppm) : 76.86. FT-IR (cm-1) : 3126 cm-1 (υCsp2 / Csp3 – H), 1600 cm-1 (υC=O), 1480 cm-1. ESI (m/z) : [M + H]+ = 217.04. UV-vis (absolute ethanol) : λ1max = 327 nm. Band gap = 3.79 eV.

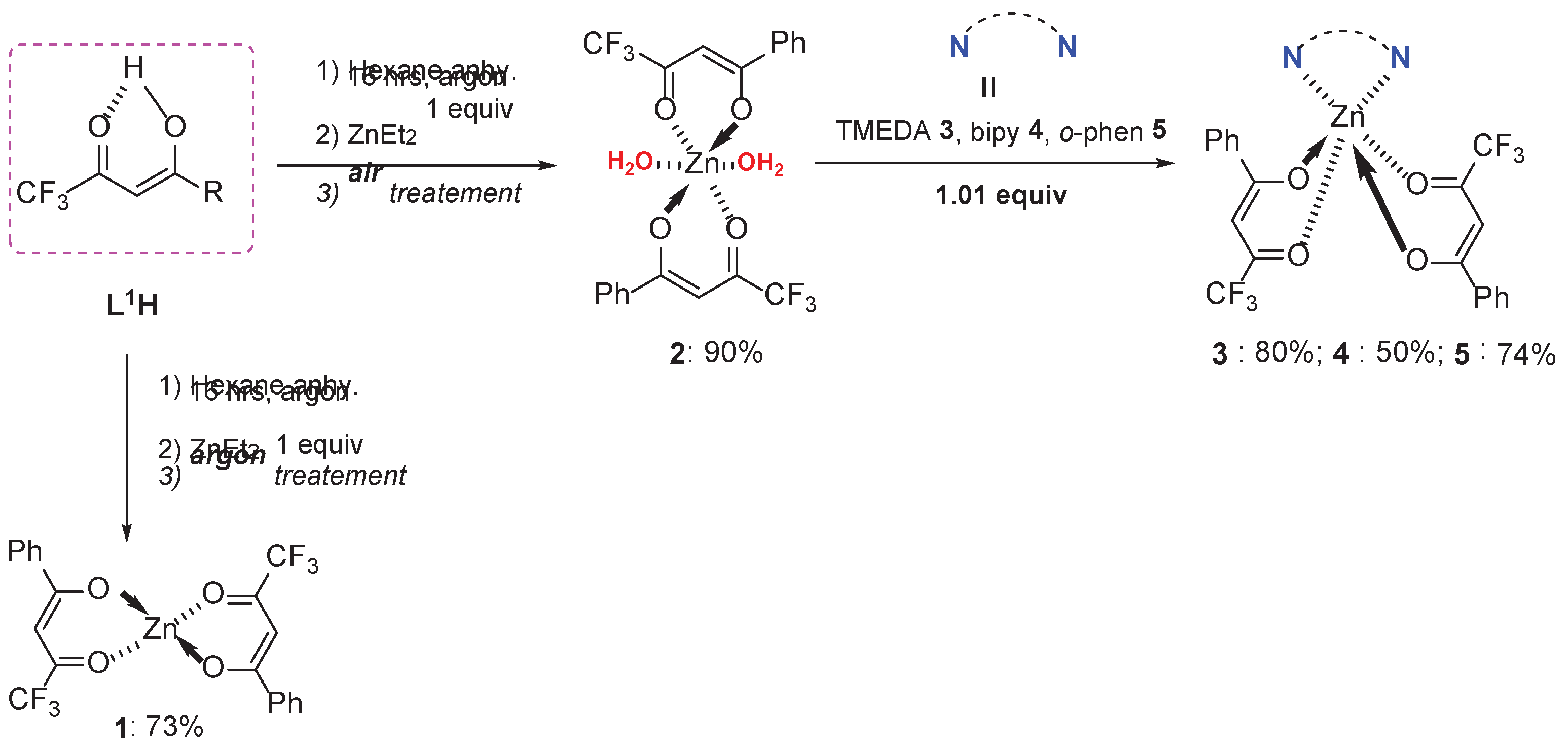

General Procedure for the Synthesis of the Complexes 1-5

The synthesis (via Brønsted acid-base reaction), characterizations and purification of the non-hydrated complex

1 was performed under argon, starting from ligand

L1H (

Scheme 1, left). The same reaction but treated under air led to the hydrated counterpart

2 (

Scheme 1, right). Heteroleptic zinc complexes

3-

5 were produced when nitrogen chelating Lewis base (LB) ligands such as TMEDA, bipy or

o-phen) were added to the medium in a respective molar ratio Zn:LB of 1:1.

[Zn(L1)2]m (1)

Under argon, 1 g of 4,4,4-trifluoro-1-phenylbutane-1,3-dione (L1H) (4.62 mmol) was vigorously stirred and dissolved in anhydrous hexane (20 mL). 3 mL of toluene solution of ZnEt2 (2.31 mmol) were added dropwise at room temperature and the mixture was stirred overnight. The solvent was removed under vacuum and the resulting white solid was washed with anhydrous hexane and dried under vacuum to give 1 g of 1 (yield = 73 %). 1 was then stored in a glove box. The complex is soluble in polar solvents like acetone, tetrahydrofuran, acetonitrile and slightly soluble in dichloromethane, chloroform.

1 : C20H12O4F6Zn. MW = 495 g.mol-1. 1H NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm) : 7.99 (4H, d, J = 7.43 Hz, HCar) ; 7.6 (2H, t, J = 7.36 Hz, HCar) ; 7.48 (4H, t, J = 7.36 Hz, HCar) ; 6.63 (2H, s, -CH-). 19F NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm) : -75.55.

[Zn(L1)2(H2O)2] (2)

The same procedure used for the synthesis of compound 1 was repeated, except the reaction mixture was exposed to air immediately after the reaction was stopped. After solvent removal via rotary evaporation, a resulting white solid of 2 (2.2 g, 90 %) was obtained and collected by filtration after being washed by hexane. The complex is soluble in polar solvents such as acetone, tetrahydrofuran, acetonitrile, and slightly soluble in dichloromethane and chloroform. Colourless single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained by slow evaporation from an acetonitrile solution of 2.

2 : C20H16O6F6Zn. MW = 531 g.mol-1 1H NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm) : 7.92 (4H, d, J = 8.16 Hz, HCar) ; 7.6 (2H, t, J = 7.05 Hz, HCar) ; 7.48 (4H, t, J = 7.92 Hz, HCar) ; 6.6 (2H, s, -CH-). 19F NMR (CDCl3, δ ppm) : -75.58 ppm. FT-IR (cm-1) : 3363 cm-1 (υO–H of H2O), 3070 cm-1 (υCsp2 – H), 1606 cm-1 (υC=O), 1573 cm-1 (υC=C), 1311 cm-1 (υC–O). ESI (m/z) : [M + Na+]+ = 516.98. UV-vis (Absolute ethanol) : λ1max = 328 nm. Band gap = 3.78 eV.

[Zn(L1)2(TMEDA)] (3)

531 mg of [Zn(L1)2(H2O)2] 2 (1 mmol) and 0.18 mL of TMEDA (1.2 mmol) were mixed in 10 mL of THF and the mixture stirred for 18 hrs at room temperature. Both THF and TMEDA were removed by rotary evaporator at 65 oC. The resulting white solid 3 (0.46 g, 80 %) was washed with hexane (20 mL) and collected and dried on a Büchner. The complex is moderately soluble in highly polar solvents such as acetone and acetonitrile but only slightly soluble in less polar solvents such as dichloromethane, chloroform and others. Colorless single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained by slow evaporation from a saturated acetonitrile solution of 3.

3 : C26H28O4F6N2Zn. MW = 611 g.mol-1. 1H NMR ((CD3)2CO, δ ppm) : 7.91 (4H, d, J = 7.21 Hz, HCar) ; 7.50 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, HCar) ; 7.39 (4H, t, J = 7.52 Hz, HCar) ; 6.28 (2H, s, -CH-) ; 2.85 (4H, s, -CH2N) ; 2.49 (12H, s, CH3N).19F NMR ((CD3)2CO, δ ppm) : 100.89 ppm. FT-IR (cm-1) : 2800-3070 cm-1 (υCsp2 / Csp3– H),1621 cm-1 (υC=O), 1573 cm-1 (υC=C), 1311 cm-1 (υC–O). ESI (m/z) : ESI (m/z) : [M + Na+]+ = 633.11. UV-vis (absolute ethanol) : λ1max = 323 nm. Band gap = 3.84 eV.

[Zn(L1)2(bipy)] (4)

The same procedure used for the synthesis of compound 3 was followed to give 4 by mixing 531 mg of 2 (1 mmol) and 187.5 mg of bipyridine (1.2 mmol) in 10 mL THF. After stirring, the resulting white solid 4 (0.334 g, 50 %) was obtained and washed with an ethyl acetate-hexane mixture (2:8) to remove the excess of bipyridine. The complex is soluble in polar solvents like acetone, tetrahydrofuran, acetonitrile and slightly soluble in dichloromethane and chloroform. Colorless single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained by slow evaporation from a saturated acetonitrile solution of 4.

4 : C30H20O4F6N2Zn. MW = 651 g.mol-1 1H NMR ((CD3)2CO, δ ppm) : 8.82 (2H, d, J = 4.36 Hz, HCbipy) ; 8.67 (2H, d, J = 8.24 Hz, HCbipy) ; 8.33 (2H, td, 3J = 1.4 Hz, 4J = 9.07 Hz, HCbipy) ; 7.85 (6H, m, HCbipy + HCar) ; 7.5 (2H, t, J = 7.34 Hz, HCar) ; 7.39 (4H, t, J = 7.5 Hz, HCar) ; 6.33 (2H, s, -CH-). 19F NMR ((CD3)2CO, δ ppm) : 101.19 ppm. FT-IR (cm-1) : 3029-3114 cm-1 (υCsp2 / Csp3– H), 1612 cm-1 (υC=O), 1577 cm-1 (υC=C), 1311 cm-1 (υC–O). ESI (m/z) : [M + Na+]+ = 673.05. UV-vis (absolute ethanol) : λ1max = 324 nm. Band gap = 3.83 eV.

[Zn(L1)2(o-phen)] (5)

The same procedure used for the synthesis of compound 4 was followed for 5 by mixing 531 mg of 2 (1 mmol) and 218 mg of 1,10-phenanthroline.H2O (1.1 mmol) in 10 mL THF. 5 (0.50 g, 74 %) was collected after its impure form 5 was dissolved in CH3CN (50 mL : 10 mL for each 100 mg of product) in order to remove the excess of 1,10-phenanthroline which precipitated. This is followed by washing with hexane (20 mL) and drying on a Büchner to obtain the pure complex. The complex is soluble in polar solvents like acetone, tetrahydrofuran, acetonitrile and slightly soluble in dichloromethane and chloroform. Colourless single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained by slow evaporation from a saturated acetonitrile solution of 5.

5 : C32H20O4F6N2Zn. MW = 675 g.mol-1. 1H NMR ((CD3)2CO, δ ppm) : 9.13 (2H, dd, J = 4.16 Hz and J = 1.31 Hz, HCo-phen) ; 8.86 (2H, dd, J = 8.33 Hz and J = 1.34 Hz, HCo-phen) ; 8.23 (2H, dd, J = 8.22 Hz and J = 4.3 Hz, HCo-phen) ; 8.14 (2H, q, J = 8.2 Hz, HCo-phen) ; 7.89 (4H, d, J = 7.22 Hz, HCar) ; 7.49 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, HCar) ; 7.4 (4H, t, J = 7.44 Hz, HCar) ; 6.4 (2H, s, -CH-). 19F NMR ((CD3)2CO, δ ppm) : 101.27 ppm. FT-IR (cm-1) 3025-3070 cm-1 (υCsp2 / Csp3– H), 1610 cm-1 (υC=O), 1575 cm-1 (υC=C), 1286 cm-1 (υC–O). ESI (m/z) : [M + Na+]+ = 697.05. UV-vis (absolute ethanol) : λ1max = 322 nm. Band gap = 3.85 eV.