Submitted:

05 October 2024

Posted:

07 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Complex | [Zn(HC4O4)(H2O)4] | [Zn(C4O4)(H2O)4] | |

| CCDC | 929462 | - | - |

| Ref. | [43] | [51] | [9] |

| Empirical formula | C8H10O12Zn | ZnC4O4,4H2O | ZnC4O4,4H2O |

| Moiety formula | C8H10O12Zn | ‘C8 O16 Zn2’ | ‘C8 O16 Zn2’ |

| Formula mass | - | 249.48 | - |

| Crystal system | Triclinic | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space Group | P-1 | C2/c | Cc |

| a [Å] | 5.0919(5) | 8.986(2) | 9.012(2) |

| b [Å] | 7.3113(7) | 13.333(2) | 13.336(3) |

| c [Å] | 8.7536(7) | 6.694(3) | 6.746(2) |

| α [o] | 66.440(6) | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| β [o] | 77.254(7) | 99.67(2) | 99.33(2) |

| γ [o] | 75.480(7) | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| V [Å3] | 286.50(5) | 790.6(3) | 800.0 |

| Z | 1 | 4 | - |

| p[g.cm-1] | 2.107 | 2.096 | 2.07 |

| F000 | 184 | - | - |

| μ(Mo-K) [mm-1] | 2.216 | 31.9 | - |

| T [K] | 100 (2) | 120(2) | - |

| θ range | 4.68– 29.66 | 40–90 | - |

| Refl. collected | 3003 | 19653 | 2639 |

| Unique refl. | 1308 | 4140 | - |

| R1[2σ(I)] | 0.0513 | 0.023 | - |

| R1 (all data) | 0.0534 | 0.024 | 0.039 |

| wR2 | 0.1325 | 0.024 | 0.042 |

| GooF | 1.092 | - | - |

| Diff. peak/ hole [e/Å3] | 1.464/ -1.792 | 0.79/-1.13 | - |

| Complex | [Zn(C4O4)(H2O)4] | ||

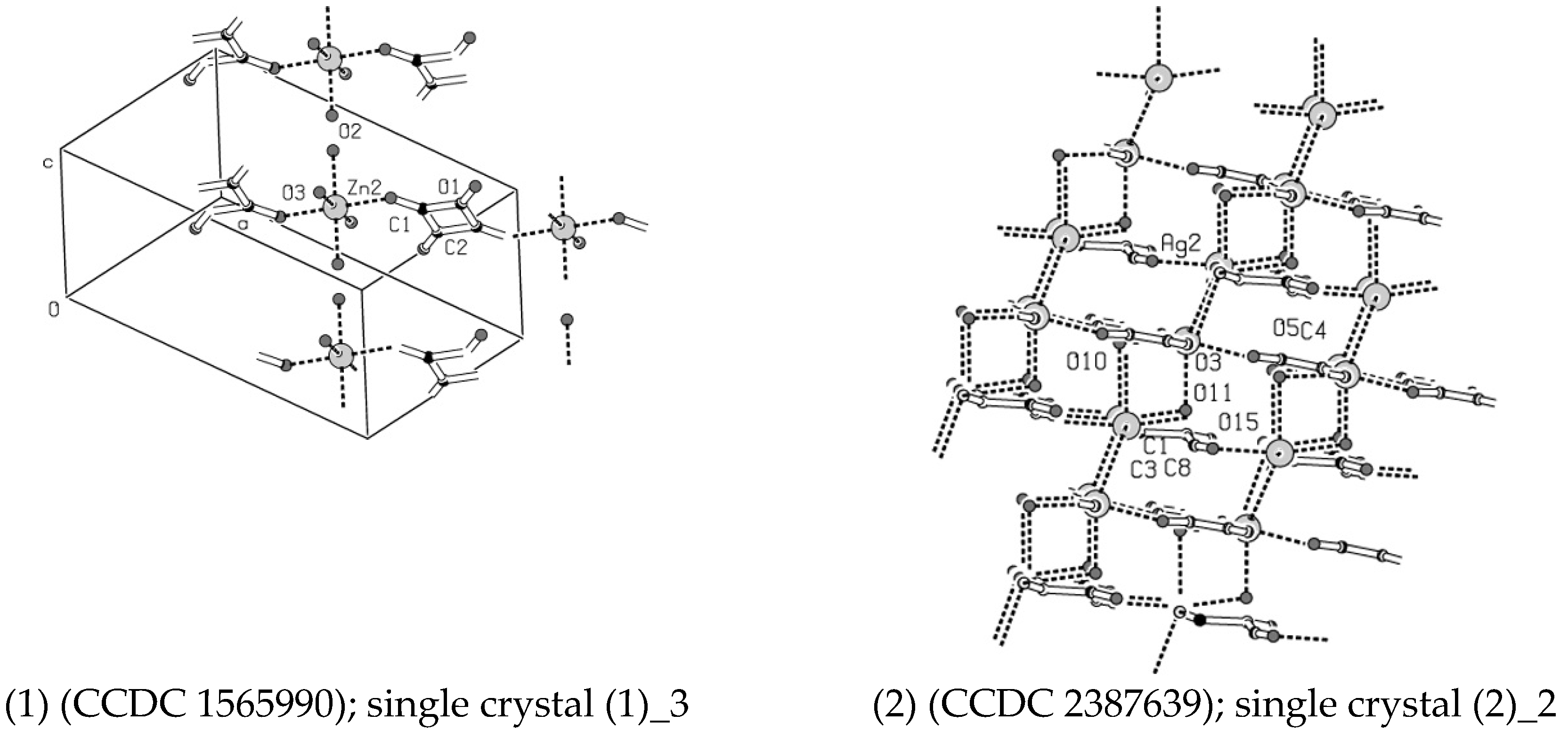

| CCDC | 1917571 | 1917547 | 1565990 |

| Single crystal | (1)_1 | (1)_2 | (1)_3 |

| Ref. | This work [55] | This work [56] | This work |

| Empirical formula | ZnC4O4,4H2O | ZnC4O4,4H2O | ZnC4O4,4H2O |

| Moiety formula | ‘C8 O16 Zn2’ | ‘C8 O16 Zn2’ | C4 O8 Zn |

| Formula mass | 482.82 | 482.82 | 241.41 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space Group | C2/c | C2/c | C2/c |

| a [Å] | 9.003(3) | 9.003(3) | 8.982(3) |

| b [Å] | 13.295(5) | 13.295(5) | 13.315(5) |

| c [Å] | 6.746(3) | 6.746(3) | 6.734(3) |

| α [o] | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| β [o] | 99.244(17) | 99.244(17) | 99.327(15) |

| γ [o] | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| V [Å3] | 797.0(5) | 797.0(5) | 794.7(5) |

| Z | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| p[g.cm-1] | 2.012 | 2.012 | 2.018 |

| F000 | 472 | 472 | 472 |

| μ(Mo-K) [mm-1] | 3.095 | 3.095 | 3.104 |

| T [K] | 293(2) | 300(2) | 293(2) |

| θ range | 4.33–25.29 | 4.33–25.11 | 2.76–25.12 |

| Refl. collected | 1180 | 1157 | 1200 |

| Unique refl. | 643 | 641 | 586 |

| R1[2σ(I)] | 0.0796 | 0.0581 | 0.0608 |

| R1 (all data) | 0.0906 | 0.1562 | 0.0660 |

| wR2 | 0.1937 | 0.1532 | 0.0721 |

| GooF | 1.013 | 1.383 | 1.128 |

| Diff. peak/ hole [e/Å3] | 1.414/-1.477 | 0.674/-1.059 | 1.835/-1.344 |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis

2.2. Analytical Instrumentation

2.3. Theory/Computations

2.4. Chemometrics

3. Results

3.1. Chromatographic and Mass Spectrometric Data on Solution

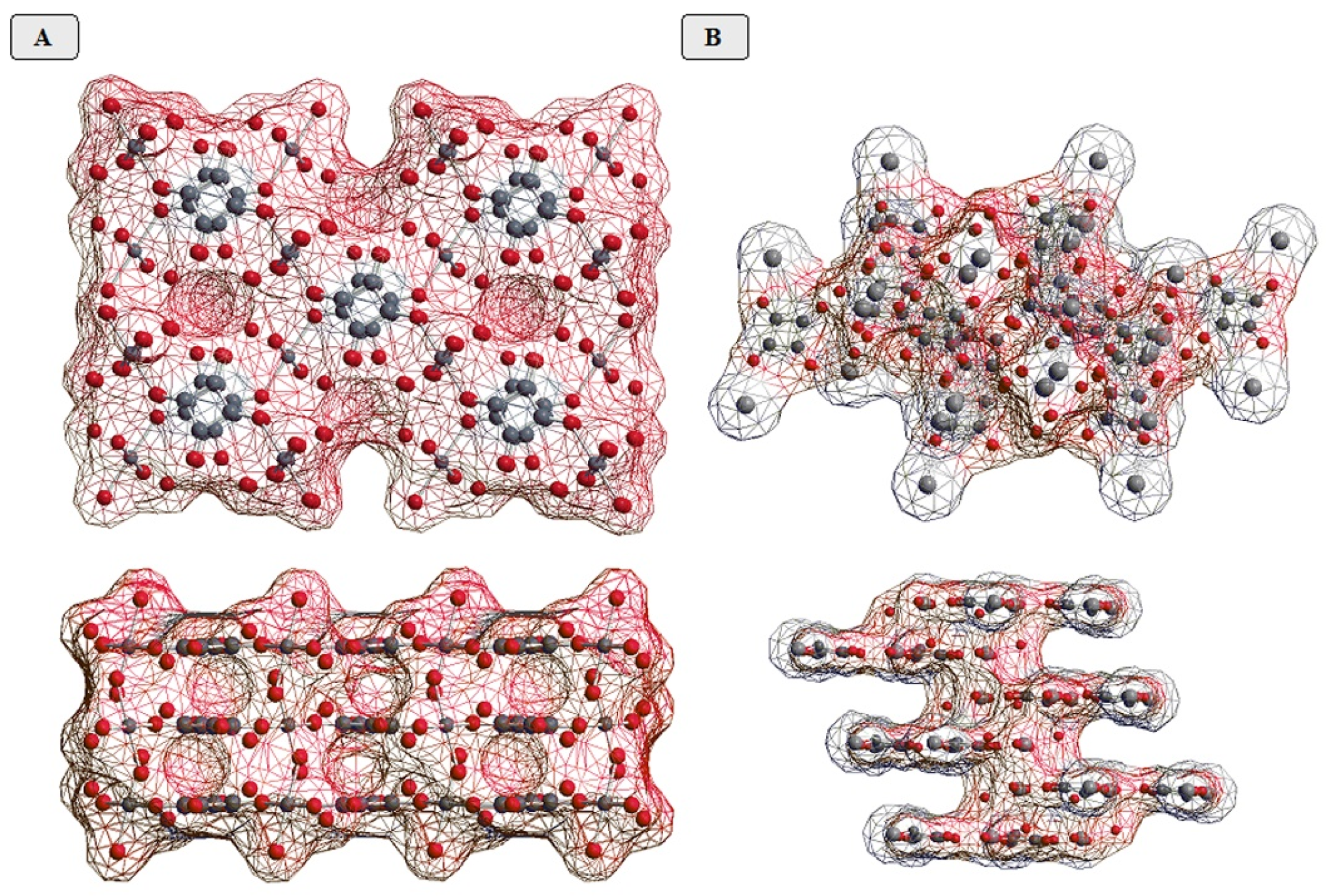

3.2. Crystallographic Data

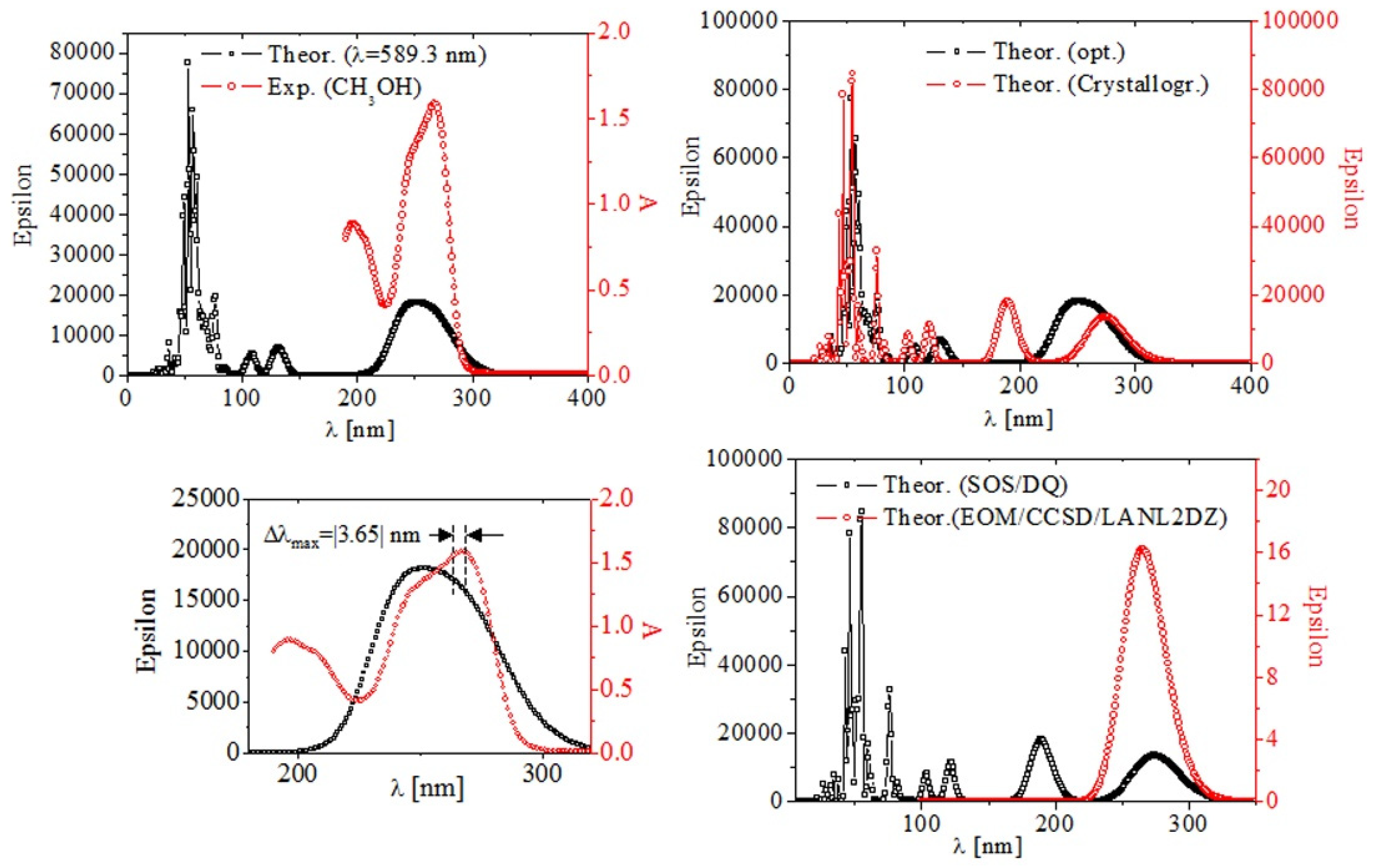

3.3. Electronic Optical Properties in Solution

3.4. Vibrational Properties in Crystalline State

3.5. Nonlinear Optical Properties

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qi, S., Cheng, P., Han, X., Ge, F., Shi, R., Xu, L., Li, G., Xu, J. Organic-inorganic hybrid antimony(III) halides for second harmonic generation. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22, 6545–6553. [CrossRef]

- Halasyamani, P., Zhang, W. Viewpoint: Inorganic materials for UV and deep-UV nonlinear-optical applications. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 12077–12085. [CrossRef]

- Liang, H., Yang, Y., Shao, L., Zhu, W., Liu, X., Hua, B., Huang, F. Nanoencapsulation-induced second harmonic generation in pillararene-based host-guest complex cocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 2870–2876.

- Liu, M., Tang, X., Zhang, Y., Ren, J., Wang, S., Wu, S., Mi, J., Huang, Y. Strategy for a rational design of deep-ultraviolet nonlinear optical materials from zeolites. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 15527–15536. [CrossRef]

- Meena, M., Ebinezer, B., Manikandan, E., Sundararajan, R., Shalini, M., Natarajan, R. Synthesis and optical characterizations of L-phenylalanine lithium sulphate (LPLS) semi-organic single crystal. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron 2023, 34, 395. [CrossRef]

- Manganelli, C., Pintus, P., Bonati, C. Modeling of strain-induced Pockels effect in silicon. Opt. Expr. 2015, 23, 28649. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B. Comment on “Comment on “Crystallographic and theoretical study of the atypical distorted octahedral geometry of the metal chromophore of zinc(II) bis((1R,2R)-1,2-diaminocyclohexane) dinitrate””. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1287, 135746. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B., Spiteller, M. Noncentrosymmetric organic crystals of barbiturates as potential nonlinear optical phores: experimental and theoretical analyses. Chem. Pap. 2019, 73, 2821–2844. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A., Riegler, E., lt, I., Böhme, H., Robl, C. Transition metal squarates, I. Chain structures M(C4O4).4H2O. Z. Naturforsch. 1986, 41b. 18–24.

- West, R. Niu, H. New aromatic anions. VII. Complexes of saquarate ion with some divalent and trivalent metals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 2589–2590.

- Jayaramulu, K., Krishna, K., George, S., Eswaramoorthy, M., Maji, T. Shape assisted fabrication of fluorescent cages of. [CrossRef]

- squarate based metal–organic coordination frameworks. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 3937–3939. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H., Wang, J., Zhai, Q. Development of MOF-5-like ultra-microporous metal-squarate frameworks for efficient acetylene storage and separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11. 21203–21210. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, H., Andac, O., Gorduk, S. Synthesis, characterization, and hydrogen storage capacities of polymeric squaric acid complexes containing 1-vinylimidazole. Polyhedron 2017, 133, 16–23. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Zhou, J., Shi, Z., Kuai, Y., Hu, Z., Cao, Z., Li, S. Microwave-assisted in-situ synthesis of low-dimensional perovskites within metal-organic frameworks for optoelectronic applications. Appl. Mater. Today 2024, 40, 102418. [CrossRef]

- Seco, J., Calahorro, A., Sebastian, E., Salinas-Castillo, A., Colacio, E., Rodriguez-Dieguez, A. Experimental and theoretical study of photoluminescence and magnetic properties of metal–organic polymers based on squarate and tetrazolate moieties containing linkers. New J. Chem. 2015, 39, 9926–9930. [CrossRef]

- Stone, J., Decoteau, E., Polinski, M. Synthesis and structural characterization of an air and water stable divalent Europium squarate prepared by in situ reduction. J. Solid State Chem. 2021, 297, 122048. [CrossRef]

- Mani, C. Berthold, T., Fechler, N. Cubism on the nanoscale: From squaric acid to porous carbon tubes. Small 2016, 21, 2906–2912.

- Vatani, P., Aliannezhadi, M., Tehrani, F. Improvement of optical and structural properties of ZIF-8 by producing multifunctional Zn/Co bimetallic ZIFs for wastewater treatment from copper ions and dye. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15434. [CrossRef]

- Getzner, L., Paliwoda, D., Vendier, L., Lawson-Daku, L., Rotaru, A., Molnar, G., Cobo, S., Bousseksou, A. Combining electron transfer, spin crossover, and redox properties in metal-organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7192. [CrossRef]

- Kenzhebayeva, Y., Kulachenkov, N., Rzhevskiy, S., Slepukhin, P., Shilovskikh, V., Efimova, V., Alekseevskiy, P., Gor, G., Emelianova, A., Shipilovskikh, S., Yushina, I., Krylov, A., Pavlov, D., Fedin, V., Potapov, A., Milichko, V. Light-driven anisotropy of 2D metal-organic framework single crystal for repeatable optical modulation. Commun. Mater. 2024, 5, 48. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H., Xu, X.; Qiao, X.; Kottilil, D., Shi, D., Fan, W.; Yuan, Y.; Yu, X.; Babusenan, A.; Zhang, M.; Ji, W. Tunable nonlinear optical properties based on metal-organic framework single crystals. Adv. Optical Mater. 2024, 12, 2302405. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chung, W.; Lin, H.; Dai, S.; Shiu, J.; Lee, G.; Sheu, H.; Lee, W. Assembly of two Zinc(II)-squarate coordination polymers with noncovalent and covalent bonds derived from flexible ligands, 1,2-bis(4-pyridyl)ethane (dpe). CrystEngComm 2011, 13, 2130–2136. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yin, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, C. Uncommon 3D twofold interpenetrated zinc phosphate consisting of inorganic chains and mixed ligands for highly efficient dye removal ability using its nanosized particles. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 7964–7969. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ke, S.; Hsieh, Y.; Huang, S.; Wang, T.; Lee, G.; Chuang, Y. Water de/adsorption associated with single-crystal-to-single crystal structural transformation of a series of two-dimensional metal-organic frameworks, [M(bipy)(C4O4)(H2O)2].3H2O (M = Mn, Fe, and Zn, and bipy = 4,4′-bipyridine). J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2019, 66, 1031–1040.

- Mautner, F.; Fischer, R.; Grant, A.; Romain, D.; Salem, N.; Louka, F.; Massoud, S. Copper(II) and zinc(II) complexes bridged by benzenoid aromatic oxocarbon and dicarboxylate dianions. Polyhedron 2023, 234, 116327. [CrossRef]

- Dan, M.; Sivashankar, K.; Cheetham, A.; Rao, C. Amine-templated metal squarates. J. Solid State Chem. 2003, 174, 60–68. [CrossRef]

- Basile, M.; Unruh, D.; Streicher, L.; Forbes, T. Spectral analysis of the uranyl squarate and croconate system: Evaluating differences between the solution and solid-state phases. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 5330–5341. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.; Riegler, E.; Robl, C. Ubergangs metallquadratate, III Über die trikline Käfigstruktur des (MC4O4.2H2O).3 CH3COOH.H2O (M = Zn2+, Mn2+). Z. Naturforsch. 1986, 41b, 1333–1336.

- Weiss, A.; Riegler, E.; Robl, C. Transition metal squarates, On the Structure of cubic (MC4O4.2H2O).CH3COOH.H2O (M = Zn2+, Ni2+). Z. Naturforsch. 1986, 41b, 1329–1332.

- Kirchmaier, R.; Altin, E.; Lentz, A. Crystal structure of tetraaqua-2-pyrazine-zinc(II) squarate, [Zn(H2O)4(C4H4N2)](C4O4). Z. Kristallogr. NCS 2004, 219, 33–34.

- Ucar, I.; Karabulut, B.; Bulut, A.; Bueyue kguengoer, O. Synthesis, crystal structure, Cu2+ doped EPR and voltammetric studies of bis[N-(2-hydroxyethyl)ethylenediamine]zinc(II) squarate monohydrate. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2007, 68, 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Bulut, A.; Ucar, L.; Kalyoncu, T.; Yerli, Y.; Bueyuekguengoer, O. Structural and magnetic properties of one-dimensional squarate bridged coordination polymers containing 2-aminomethylpyridine ligand. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 2010, 20, 793–801. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, C.; Lee, G.; Tsai, H. Syntheses, structures, and magnetic properties of two 1D, mixed-ligand, metal coordination polymers, [M(C4O4)(dpa)(OH2)] (M = CoII, NiII, and ZnII; dpa = 2,2′-dipyridylamine) and [Cu(C4O4)(dpa)(H2O)]2.(H2O). Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 2005, 1334–1342. [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.; Chen, W.; Zhou, H.; Morsali, A. Tuning redox activity in metal–organic frameworks: From structure to application. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 517, 216004. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chuo, C.; Lee, G.; Wang, C. Self-assembly of two mixed-ligands metal-organic coordination polymers. Inorganic Chem. Commun. 2003, 6, 135–140. [CrossRef]

- Rostami, A.; Colin, A.; Li, X.; Chudzinski, M.; Lough, A.; Taylor, M. N,N’-diarylsquaramides: General, high-yielding synthesis and applications in colorimetric anion sensing. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 3983–3992. [CrossRef]

- Piggot, P.; Seenarine, S.; Hall, L. Complexes of aminosquarate ligands with first-row transition metals and lanthanides: New insights into their hydrolysis. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 5243–5251. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, J.; Shi, Z.; Kuai, Y.; Hu, Z.; Cao, Z.; Li, S. Microwave-assisted in-situ synthesis of low-dimensional perovskites within metal-organic frameworks for optoelectronic applications. Appl. Mater. Today 2024, 40, 102418. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M.; Stochastic dynamic electrospray ionization mass spectrometric diffusion parameters and 3D structural determination of complexes of AgI-ion—experimental and theoretical 3 treatment. Int. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 292, 111307. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, I.; Spiteller, M. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometric solvate cluster and multiply charged ions a stochastic dynamic approach to 3D structural analysis. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 731.

- Ivanova, I.; Spiteller, M. Electrospray ionization stochastic dynamic mass spectrometric 3D structural analysis of ZnII-ion containing complexes in solution. Inorg. Nano-Met. Chem. 2022, 52, 1407–1429. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Mir, M. Photomechanical properties in metal-organic crystals. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 7555–7565. [CrossRef]

- Serb, M.; Braun, B.; Oprea, O.; Dumitru, F. Synthesis, crystal structure and thermal decomposition study of new [tetraaqua-bis-(monohydrogensquarate)]zinc(II) complex. Digest J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2013, 8, 797–804.

- Mondal, A.; Das, D.; Chaudhuri, N. Thermal studies of nickel(II) squarate complexes of triamines in the solid state. J. Therm. Anal. Cal. 1999, 55, 165–173. [CrossRef]

- Maji, T.; Das, D.; Chaudhuri, N. Preparation, characterization and solid state thermal studies of cadmium(II) squarate complexes ofhane-1,2-diamine and its serivatives. J. Therm. Anal. Cal. 2001, 63, 617–627. [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Ghosh, A.; Chaudhuri, N. Preparation, characterization, and solid state thermal studies of nickel(II) squarate complexes of 1,2-Ethanediamine and its derivatives. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1997, 70, 789–797. [CrossRef]

- Maji, T.; Das, D.; Chaudhuri, N. Thermal studies of copper(II) squarate complexes of diamines in the solid state. J. Therm. Anal. Cal. 2002, 68, 319–328. [CrossRef]

- Yeşilel, O.; Ölmez, H.; Soylu, S. Synthesis and spectrothermal studies of thermochromic diamine complexes of cobalt(III), nickel(II) and copper(II) squarate. Crystal structure of [Co(en)3](sq)1.5.6H2O. Trans. Met. Chem. 2006, 31, 396–404. [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, H. Squaric acid: Reactions with certain metals. Michrochem. J. 1972, 17, 443–455. [CrossRef]

- Moritomo, Y.; Koshihara, S.; Tokura, Y. Asymmetric-to-ceritrosymmetric structure change of molecules in squaric acid crystal: Evidence for pressure-induced change of correlated proton potentlats. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 93, 5429–5435. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Wang, C.; Chen, K.; Lee, G.; Wang, Y. Bond characterization of metal squarate complexes [MII(C4O4)(H2O)4; M = Fe, Co, Ni, Zn, J. Phys. Chem. A 1999, 103, 156–165. [CrossRef]

- Robl, C.; Kuhs, W. Hydrogen bonding in the chain-like coordination polymer ZnC4O4.4H2O: A neutron diffraction study. J. Solid State Chem. 1988, 75, 15–20. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. AgI and ZnII complexes with possible application as NLO materials—crystal structures and properties. Polyhedron 2011, 30, 241–245. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. CCDC 771415: Experimental crystal structure determination, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. CCDC 1917571: Experimental crystal structure determination, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. CCDC 1917547: Experimental crystal structure determination, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Spek, A. Single-crystal structure validation with the program PLATON. J. Appl. Cryst. 2003, 36, 7–13. [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Experimental phasing with SHELXC/D/E: combining chain tracing with density modification. Acta Crysallogr. D 2010, 66, 479–485. [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Phase annealing in SHELX-90: direct methods for larger structures. Acta Crystallogr. A 1990, 46, 467–473. [CrossRef]

- Blessing, R. An empirical correction for absorption anisotropy. Acta Crystallogr. 1995, A51, 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Spek, A. Single-crystal structure validation with the program PLATON. J. App.Crystallogr. 2003, 36, 7–13. [CrossRef]

- [http://www.ccp14.ac.uk/ccp/web-mirrors/mallinson/~paul/xd.html (XD2016)].

- Momma, K.; Ikeda, T.; Belik, A.; Izumi, F. Dysnomia, a computer program for maximum-entropy method (MEM) analysis and its performance in the MEM-based pattern fitting. Powder Diffr. 2013, 28, 184–192. [CrossRef]

- [http://www.crystallography.fr/crm2/fr/services/logiciels/MoPro.htm].

- [http://www.chem.gla.ac.uk/~louis/software/wingx/].

- Dunitz, J.; Schomaker, V.; Trueblood, K. Interpretation of atomic displacement parameters from diffraction studies of crystals. J. Phys. Chem. 1988, 92, 856–867. [CrossRef]

- Dunitz, J.; Maverick, E.; Trueblood, K. Atomic Motions in Molecular Crystals from Diffraction Measurements. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 1988, 27, 880–895. [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.; Trucks, G.; Schlegel,. H et al. (2009) (1998), Gaussian 09, 98. Gaussian Inc, Pittsburgh.

- [https ://www.dalto nprogram.org/download.html].

- Gordon, M.; Schmidt, M. Advances in electronic structure theory: GAMESS a decade later. In: Dykstra C, Frenking G, Kim K, Scuseria G (eds) Theory and Applications of Computational Chemistry: the first forty years. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2005, pp 1167–1189.

- [www.gauss ian.com/g_prod/gv5.htm].

- Zhao, Z.; Truhlar, D. Density functionals with broad applicability in chemistry. Acct.s Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 157–167. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acct. 2008, 120, 215–241. [CrossRef]

- Hay, P.; Wadt, W. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for K to Au including the outermost core orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 299.

- Burkert, U.; Allinger, N. Molecular mechanics in ACS Monograph 177. American Chemical Society, Washington DC, 1982, pp 1–339.

- Allinger, L. Conformational analysis. 130. MM2. A hydrocarbon force field utilizing V1 and V2 torsional terms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 8127–8134.

- Casida, M. Time-dependent density functional response theory for molecules. In Recent Advances in Density Functional Methods 155–192 (World Scientific, 1995).

- Van Gisbergen, S.; Snijders, J.; Baerends, E. Implementation of time-dependent density functional response equations. Comput. Phys. Comm. 1999, 118, 119–138. [CrossRef]

- Hirata, S.; Head-Gordon, M. Time-dependent density functional theory within the Tamm–Dancoff approximation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999, 314, 291–299. [CrossRef]

- Kelley. C. Iterative Methods for optimization, SIAM Front. Appl. Mathematics, 2009; 18. [CrossRef]

- Otto. M. Chemometrics, 3rd ed. Wiley, Weinheim, 2017; pp. 1-383.

- [http://de.openoffice.org].

- Madsen, K.; Nielsen, H.; Tingleff, T. Informatics and mathematical modelling, 2nd Ed. DTU Press, 2004.

- Miller, J.; Miller. J. Statistics and chemometrics for analytical chemistry. Pentice Hall, London, 1988; pp. 1–271.

- Taylor, J. Quality assurance of chemical measurements. Lewis Publishers, Inc. Michigan, 1987, pp. 1–328.

- Schroee, G.; Trenkler, D. Exact and randomization distributions of Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests two or three samples. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 1995, 20, 185–202. [CrossRef]

- Fay, F.; Proschan, M. Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney or t-test? On assumptions for hypothesis tests and multiple interpretations of decision rules. Stat. Surv. 2010, 4, 1–39.

- Freidlin, B.; Gastwir. J. Should the median test be retired from general use? Am. Stat. 2000, 54, 161–164.

- Brown, M.; Kelley, H.; Galwey, A.; Mohamed, M. A thermoanalytical study of thermal decomposition of silver squarate. Thermochim. Acta.1988, 127, 139–158. [CrossRef]

- Galwey, A.; Mohamedt, M. Brown, M. Thermal decomposition of silver squarate. J. Chem. Soc.Faraday Trans. 1 1988, 84, 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, L.; Howard, L. Electronic structure of aqueous squaric acid and its anions. J. Phys. Chem. 1973, 77, 314–318. [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulos, S.; Diniz, R.; Yoshida, M.; Speziali, N.; dos Santos, H.; Junqueira, G.; de Oliveira, L. Vibrational spectroscopy and aromaticity investigation of squarate salts: A theoretical and experimental approach. J. Mol. Struct. 2006, 794, 63–70. [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.; Amaral, J.; de Olivieira, L. Raman spectra of some transition metal squarate and croconate complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 1991, 243, 223–232. [CrossRef]

| Complex | [Ag(C4O4)O] n | [Ag(C4O4)O] n | [Ag(C4O4)O] n |

| CCDC | 771415 | 2387639 | 2387641 |

| Single crystal | (2)_1 | (2)_2 | (2)_3 |

| Refs. | [53,54] | This work | This work |

| Empirical formula | C4AgO5 | C4AgO5 | C4AgO5 |

| Moiety formula | C4AgO5 | C4AgO5 | C4AgO5 |

| Formula mass | 235.91 | 459.81 | 235.91 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space Group | C2/c | Cc | C2/c |

| a [Å] | 13.572(9) | 13.491(11) | 13.594(6) |

| b [Å] | 8.229(6) | 8.233(11) | 8.251(3) |

| c [Å] | 11.108(7) | 11.038(13) | 11.107(4) |

| α [o] | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| β [o] | 118.142(17) | 117.94(5) | 118.094(11) |

| γ [o] | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| V [Å3] | 1093.9(12) | 1083(2) | 1099.0(7) |

| Z | 8 | 4 | 8 |

| p[g.cm-1] | 2.865 | 2.820 | 2.852 |

| F000 | 888 | 864 | 888 |

| μ(Mo-K) [mm-1] | 3.561 | 3.666 | 3.617 |

| T [K] | 199(2) | 300(2) | 300(2) |

| θ range | 3.00–25.07 | 3.01–24.94 | 3.00–25.24 |

| Refl. collected | 3173 | 1555 | 1655 |

| Unique refl. | 951 | 1034 | 963 |

| R1[2σ(I)] | 0.0558 | 0.1544 | 0.2323 |

| R1 (all data) | 0.0587 | 0.1781 | 0.0944 |

| wR2 | 0.1819 | 0.3626 | 0.1044 |

| GooF | 0.952 | 2.026 | 1.003 |

| Diff. peak/ hole [e/Å3] | 2.591/ -1.161 | 3.374/-2.879 | 3.344/-1.724 |

| Electric dipole moment | |||

| [a.u.] | Debye | 10-30 SI | |

| μtot | 0.317187D-01 | 0.806208D-01 | 0.268922 |

| μx | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| μy | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| μz | 0.317187D-01 | 0.806208D-01 | 0.268922 |

| Dipole polarizability | |||

| α(0,0) | [au] | [10-24 esu] | [10-40 SI] |

| αiso | 0.425867D+03 | 0.631070D+02 | 0.702160D+02 |

| αaniso | 0.986272D+03 | 0.146150D+03 | 0.162614D+03 |

| αxx | 0.633700D+03 | 0.939047D+02 | 0.104483D+03 |

| αyx | 0.103717D+03 | 0.153692D+02 | 0.171006D+02 |

| αyy | 0.154964D+03 | 0.229634D+02 | 0.255502D+02 |

| αzx | -0.500754D+03 | -0.742041D+02 | -0.825632D+02 |

| αzy | -0.495223D+02 | -0.733845D+01 | -0.816513D+01 |

| αzz | 0.488936D+03 | 0.724529D+02 | 0.806147D+02 |

| α(-ω,ω) ω=455.6 nm | [au] | 10-24 esu | 10-40 SI |

| αiso | 0.153553D+03 | 0.227542D+02 | 0.253175D+02 |

| αaniso | 0.587493D+03 | 0.870575D+02 | 0.968645D+02 |

| αxx | 0.327207D+03 | 0.484871D+02 | 0.539492D+02 |

| αyx | 0.227125D+02 | 0.336565D+01 | 0.374479D+01 |

| αyy | -0.970495D+02 | -0.143813D+02 | -0.160013D+02 |

| αzx | -0.241757D+03 | -0.358247D+02 | -0.398603D+02 |

| αzy | -0.815340D+02 | -0.120821D+02 | -0.134431D+02 |

| αzz | 0.230502D+03 | 0.341568D+02 | 0.380046D+02 |

| First dipole hyperpolarizability | |||

| β(0;0,0) | [a.u.] | [10-30 esu] | [10-50 SI] |

| β|| (z) | 0.450178D+01 | 0.388919D-01 | 0.144343D-01 |

| β_|_(z) | 0.150059D+01 | 0.129640D-01 | 0.481145D-02 |

| βx | -0.369368D+02 | -0.319105 | -0.118433 |

| βy | -0.124310D+02 | -0.107394 | -0.398583D-01 |

| βz | 0.225089D+02 | 0.194459 | 0.721717D-01 |

| β|| | 0.900112D+01 | 0.777627D-01 | 0.288609D-01 |

| βxxx | -0.819435D+01 | -0.707928D-01 | -0.262740D-01 |

| βxxy | -0.923337D+01 | -0.797692D-01 | -0.296055D-01 |

| βyxy | -0.164386D+01 | -0.142017D-01 | -0.527081D-02 |

| βyyy | -0.358041D+01 | -0.309320D-01 | -0.114801D-01 |

| βxxz | 0.736136 | 0.635964D-02 | 0.236032D-02 |

| βyxz | -0.210114D+01 | -0.181522D-01 | -0.673702D-02 |

| βyyz | -0.191303D+01 | -0.165271D-01 | -0.613386D-02 |

| βzxz | -0.247405D+01 | -0.213738D-01 | -0.793269D-02 |

| βzyz | 0.867012D+01 | 0.749031D-01 | 0.277995D-01 |

| βzzz | 0.867986D+01 | 0.749873D-01 | 0.278308D-01 |

| β(-ω,ω,0) ω= 455.6 nm | |||

| [a.u.] | [10-30 esu] | [10-50 SI] | |

| β|| (z) | -0.106836D+04 | -0.922982D+01 | -0.342556D+01 |

| β_|_(z) | -0.999635D+02 | -0.863607 | -0.320519 |

| βx | 0.408269D+04 | 0.352712D+02 | 0.130906D+02 |

| βy | -0.271454D+04 | -0.234515D+02 | -0.870381D+01 |

| βz | -0.534181D+04 | -0.461491D+02 | -0.171278D+02 |

| β|| | 0.145013D+04 | 0.125280D+02 | 0.464965D+01 |

| βxxx | 0.396853D+03 | 0.342850D+01 | 0.127246D+01 |

| βyxx | 0.621301D+02 | 0.536756 | 0.199212 |

| βyyx | -0.322483D+03 | -0.278600D+01 | -0.103400D+01 |

| βzxx | -0.327435D+03 | -0.282878D+01 | -0.104987D+01 |

| βzyx | -0.113067D+03 | -0.976813 | -0.362535 |

| βzzx | 0.279499D+03 | 0.241465D+01 | 0.896175 |

| βxxy | -0.425822D+03 | -0.367877D+01 | -0.136534D+01 |

| βyxy | 0.705009D+03 | 0.609073D+01 | 0.226051D+01 |

| βyyy | -0.423235D+03 | -0.365642D+01 | -0.135704D+01 |

| βzxy | 0.496533D+03 | 0.428966D+01 | 0.159207D+01 |

| βzyy | -0.962529D+03 | -0.831550D+01 | -0.308622D+01 |

| βzzy | -0.752474D+03 | -0.650079D+01 | -0.241270D+01 |

| βxxz | -0.843863D+03 | -0.729032D+01 | -0.270573D+01 |

| βyxz | 0.220077D+03 | 0.190130D+01 | 0.705647 |

| βyyz | 0.322371D+03 | 0.278504D+01 | 0.103364D+01 |

| βzxz | 0.762547D+03 | 0.658781D+01 | 0.244500D+01 |

| βzyz | -0.195401D+03 | -0.168811D+01 | -0.626526D+00 |

| βzzz | -0.746798D+03 | -0.645175D+01 | -0.239450D+01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).