1. Introduction: QFI as a Bridge Between Theory and Practice

Quantum Fisher information (QFI) has evolved from a mathematical construct in estimation theory into a practical design principle for quantum--enhanced sensing. By linking the geometry of quantum states to the ultimate precision limits set by the quantum Cramér–Rao bound, QFI offers a unifying language for analyzing how preparation, encoding, noise, and measurement jointly determine performance [

1,

2,

3]. Over the past decade, comprehensive reviews have consolidated this landscape—spanning atomic ensembles and photonics to solid-state devices—while clarifying QFI’s dual role as both a metrological bound and an entanglement witness [

1,

2,

4,

5]. Recent experiments have begun to validate these ideas directly, including solid-state demonstrations that estimate or bound QFI without full tomography, signaling a shift from concept to deployable metric [

6,

7].

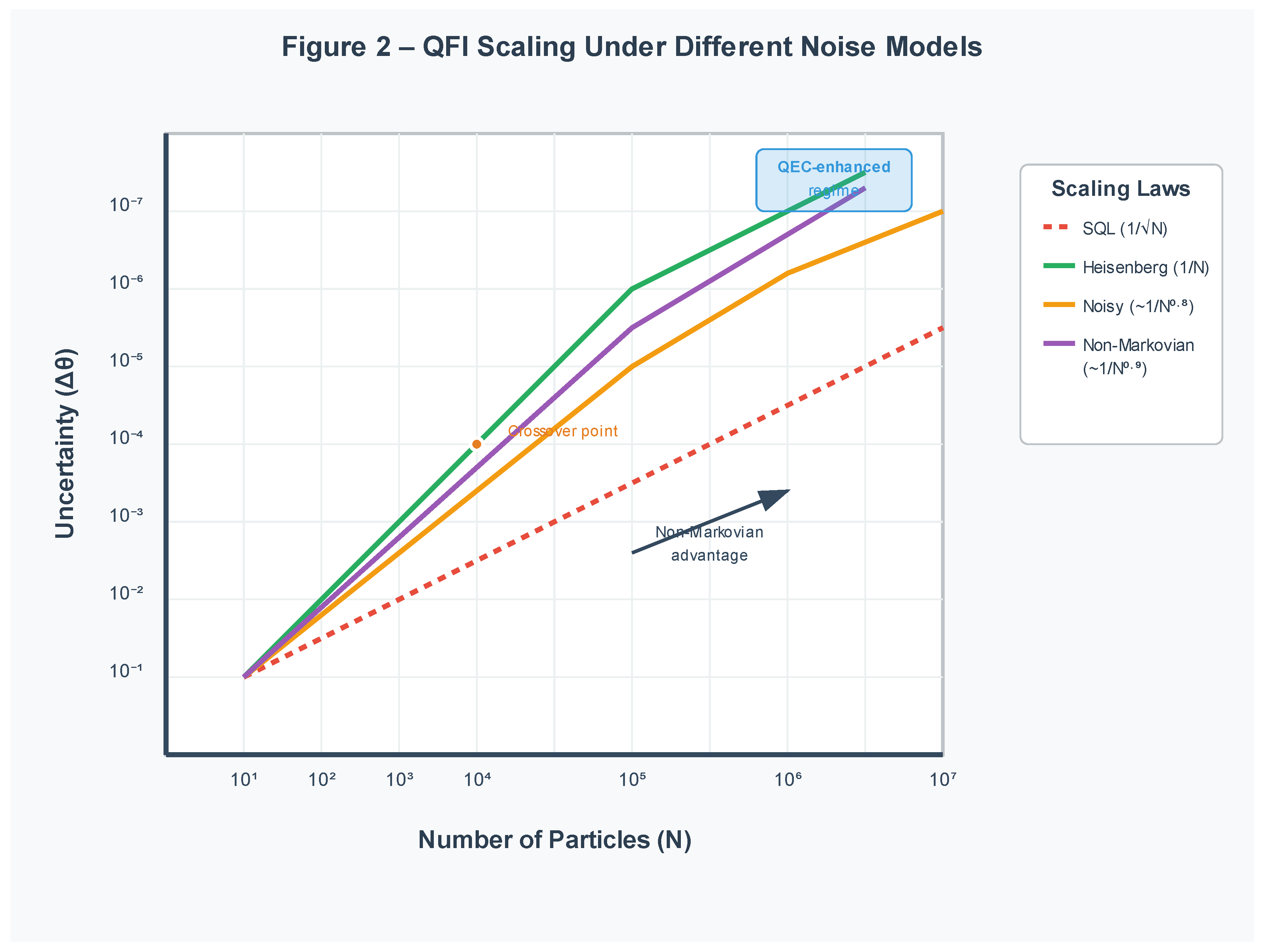

Yet the path from theory to practice is defined by tension: quantum advantages are fragile under realistic decoherence, and naïvely entangled probes often revert from Heisenberg scaling to the standard quantum limit in noisy settings [

3,

9]. In response, the field has moved on three intertwined frontiers that this Perspective highlights. First, noise is no longer treated solely as an adversary: non-Markovian and correlated environments can, in certain regimes, preserve or even revive metrological sensitivity, while quantum error correction (QEC) reframes noise management as an active resource for sensing [

10,

11,

12,

14,

15,

16]. Second, real-world sensing is rarely single-parameter. Multiparameter estimation exposes fundamental trade-offs arising from measurement incompatibility; recent bounds and geometric viewpoints provide operational criteria for when simultaneous estimation is truly advantageous [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Third, many-body platforms near criticality promise superlinear QFI scaling but raise questions of robustness, finite-size effects, and operational extraction in open systems [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Across all fronts, learning-based and randomized-measurement methods are making QFI measurable at scale on near-term devices [

49,

50,

51].

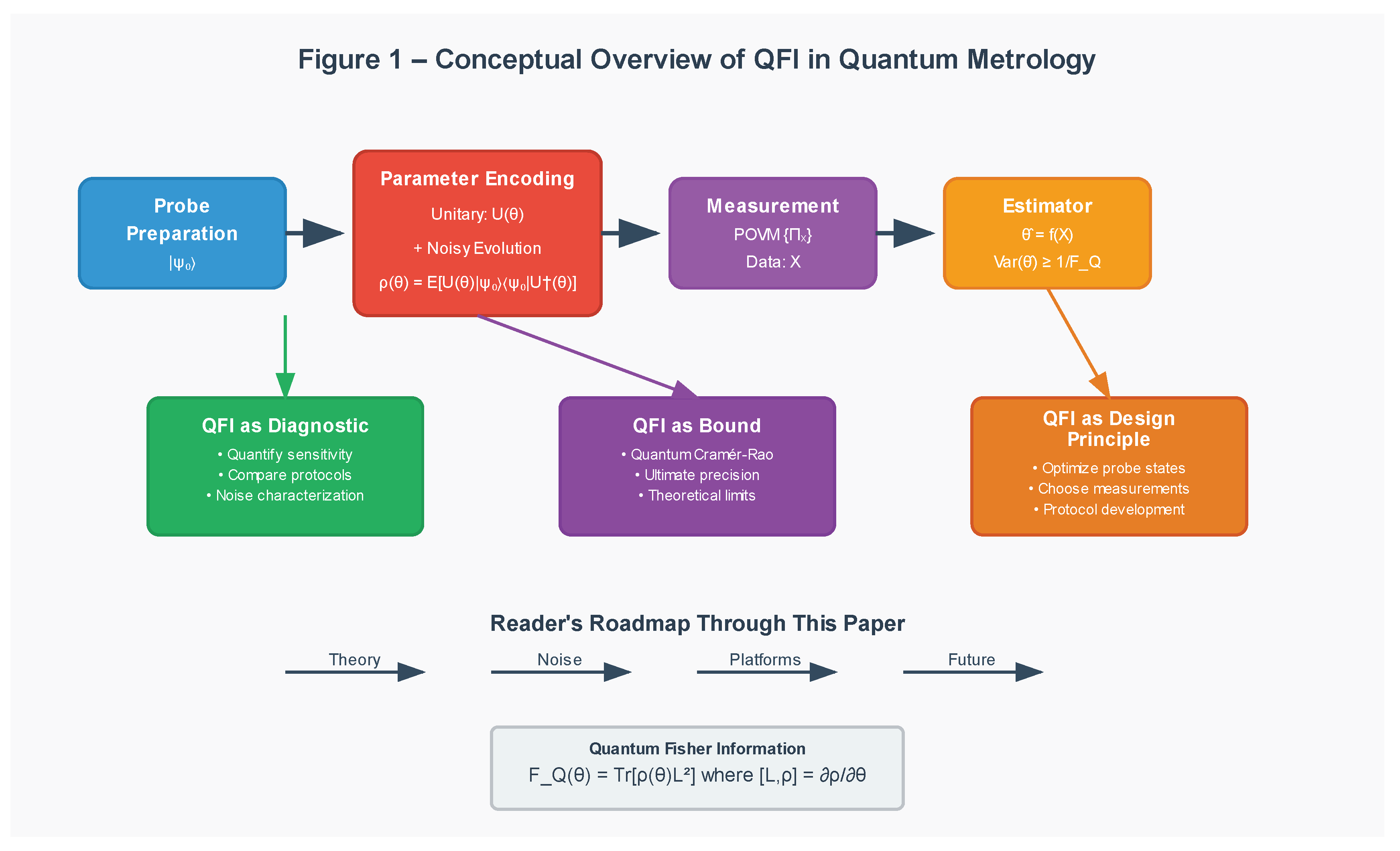

This article therefore argues for QFI beyond theory: as a diagnostic to certify resources (entanglement depth, coherence), a benchmark to compare platforms (photonic, atomic, solid-state, and networked sensors), and a design rule for noise-aware, resource-efficient protocols. We adopt a perspective style, emphasizing open problems and a forward-looking roadmap rather than exhaustive coverage.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Overview of QFI in Quantum Metrology.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Overview of QFI in Quantum Metrology.

2. Noise and Error Correction: The Double-Edged Sword

Quantum advantages in metrology are inevitably challenged by noise. Even modest levels of decoherence degrade Heisenberg scaling to the standard quantum limit (SQL), highlighting the fragility of entanglement-based protocols [

9,

10,

11]. Early theoretical work classified canonical noise channels—dephasing, amplitude damping, depolarization—and demonstrated that under phase-covariant noise, entangled probes cannot maintain super-classical scaling asymptotically [

12,

13,

14]. This pessimistic view was partially revised by recognizing that non-Markovian and time-correlated environments can transiently protect or even revive quantum Fisher information (QFI), enabling performance beyond what is possible in purely Markovian settings [

15,

16,

17].

A complementary response is quantum error correction (QEC). Unlike fault-tolerant computation, QEC for sensing does not require preserving full quantum information; only the parameter-encoding subspace must be protected. This distinction has spurred proposals for metrological codes that restore Heisenberg scaling under specific noise models [

21,

22,

23]. Experiments in trapped ions and superconducting qubits have begun to demonstrate QEC-enhanced sensing protocols, albeit with high resource overhead [

24,

25,

26]. Hybrid approaches, such as combining QEC with dynamical decoupling or variational error mitigation, suggest a continuum of strategies between passive robustness and active correction [

27,

28].

Open questions persist: Can we systematically classify “QFI-friendly” noise channels? What are the minimal overheads for practical QEC-assisted sensing? How should one balance error correction against probe number, entanglement depth, and measurement resources [

29,

30,

31]? Answering these will determine whether noise is merely a limitation—or a resource to be harnessed—in the roadmap towards practical quantum-enhanced sensing.

Figure 2.

QFI Scaling Under Different Noise Models.

Figure 2.

QFI Scaling Under Different Noise Models.

3. Multiparameter Estimation and Many-Body Frontiers

Realistic quantum sensing scenarios often involve estimating multiple parameters simultaneously—magnetic field components, phases in interferometry, or couplings in many-body Hamiltonians. The natural framework here is the quantum Fisher information matrix (QFIM), which generalizes QFI to the multiparameter domain [

28,

29,

30]. While the QFIM sets a matrix version of the quantum Cramér–Rao bound, attainability is not guaranteed: optimal measurements for different parameters may be incompatible, leading to a fundamental tension between precision and compatibility [

31,

32,

33]. Geometric approaches and information-theoretic metrics have clarified these trade-offs, but a complete operational characterization remains elusive [

34].

Parallel to multiparameter challenges, many-body quantum systems near criticality offer striking opportunities. Close to quantum phase transitions, QFI can scale super-extensively, reflecting the system’s diverging susceptibility [

35,

36,

37]. This property has been exploited to certify multipartite entanglement depth in spin models, cold-atom lattices, and Bose–Einstein condensates [

38,

39]. Yet critical systems are inherently fragile: decoherence, finite-size effects, and non-equilibrium dynamics can suppress the promised advantages [

40,

41]. Extracting metrological gain in practice requires carefully balancing entanglement generation with environmental resilience.

Recent proposals bridge these themes, showing that multiparameter estimation in many-body platforms could unlock new sensing paradigms—such as simultaneous field imaging or Hamiltonian learning [

42,

43]. Still, key open problems remain: devising compatible measurement strategies, quantifying robustness under realistic noise, and scaling beyond proof-of-concept demonstrations [

44,

45]. Addressing these questions will decide whether QFIM and criticality move from elegant theory into deployable quantum technologies.

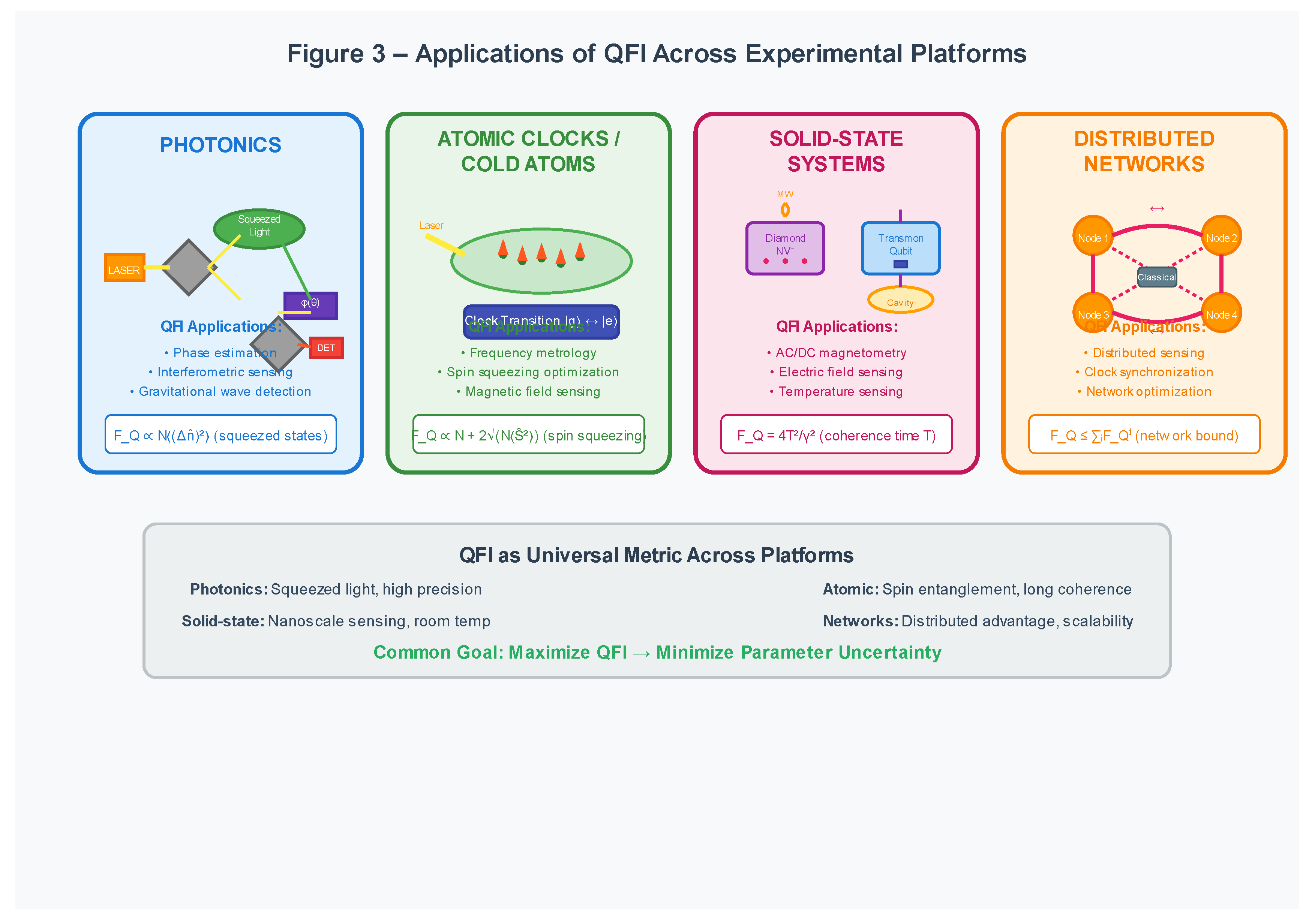

4. Platforms and Emerging Scalable Methods

The practical impact of quantum Fisher information (QFI) depends critically on its realization across diverse experimental platforms. Photonic systems, such as squeezed-light interferometers, have provided some of the earliest demonstrations of QFI-based sensitivity enhancement, including sub-shot-noise phase estimation in gravitational wave detectors [

6,

46]. Atomic clocks and cold-atom ensembles use collective spin squeezing and entanglement to surpass classical timekeeping limits, with QFI serving as a rigorous benchmark for precision gains [

47,

48]. In the solid state, nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers in diamond and superconducting qubits have begun to validate QFI directly through randomized measurements, opening the path to scalable sensing with condensed-matter systems [

49,

50]. Finally, distributed quantum sensor networks employ entanglement across separated nodes to enable spatially resolved field measurements, where QFI quantifies the trade-offs between global entanglement and local robustness [

51,

52].

Beyond specific platforms, new methods are emerging to make QFI scalable and experimentally accessible. Full tomography is infeasible for many-body systems, so randomized measurements and classical shadows have been proposed to estimate QFI efficiently from limited data [

49]. Machine learning approaches—ranging from neural-network state reconstruction to reinforcement learning for measurement optimization—further extend QFI’s reach into complex regimes where analytic evaluation is impossible [

50,

52]. These techniques align with the broader NISQ agenda: exploiting approximate, data-driven strategies to extract useful metrological resources without requiring full error-corrected quantum computation.

Together, these advances suggest that QFI is no longer confined to abstract models. It is becoming a practical diagnostic across photonics, atomic, solid-state, and networked architectures—positioning it as a unifying framework for assessing and comparing quantum technologies on the path to real-world deployment.

Figure 3.

Applications of QFI Across Experimental Platforms.

Figure 3.

Applications of QFI Across Experimental Platforms.

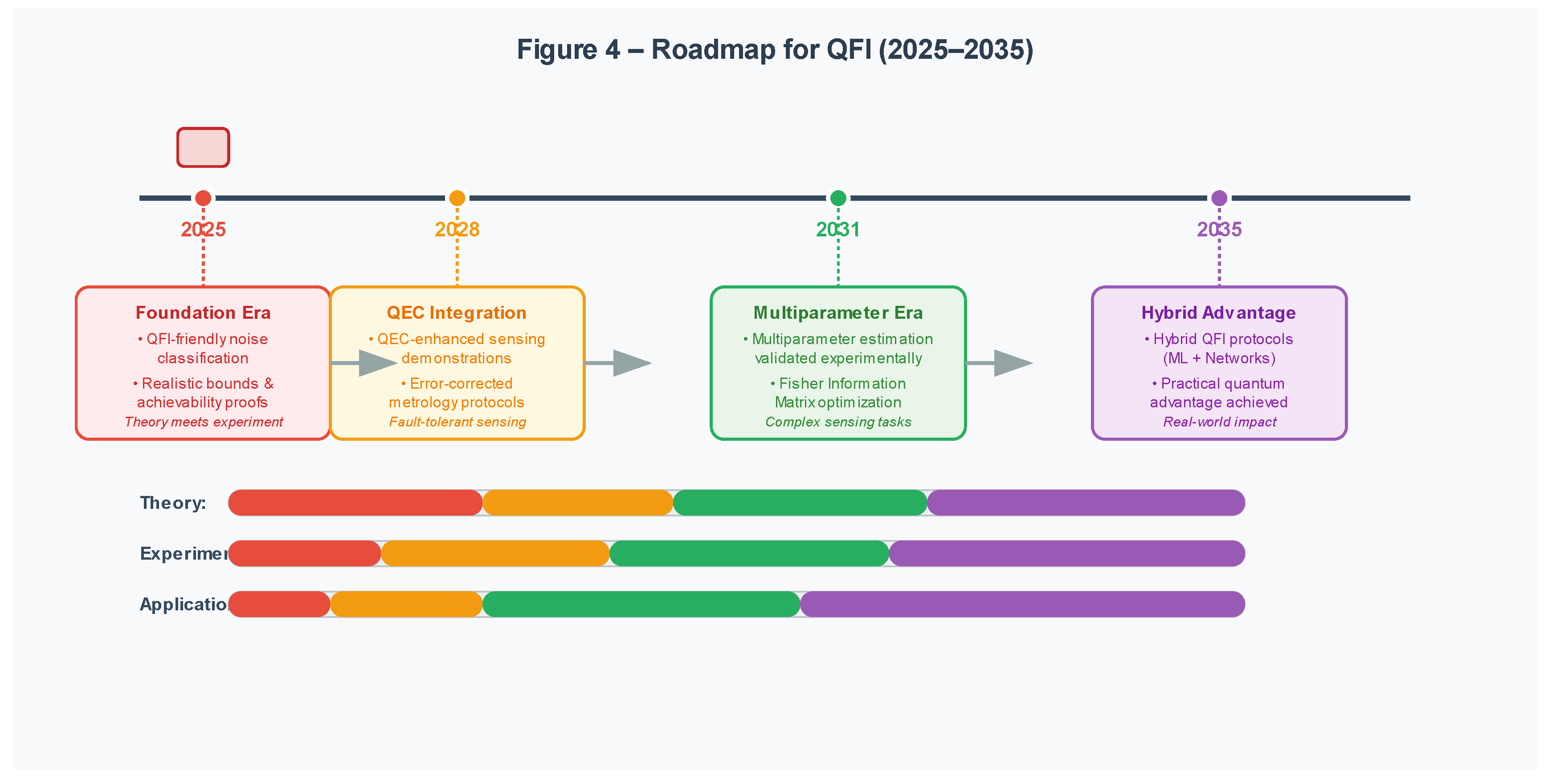

5. Outlook and Roadmap

As quantum Fisher information (QFI) matures into a practical benchmark for sensing, the next decade will be defined by addressing a set of open challenges that cut across theory, platforms, and scalability.

Table 1 summarizes these challenges: classifying noise channels that preserve QFI, reducing the overhead of quantum error correction (QEC) in sensing protocols, resolving multiparameter incompatibility, harnessing critical systems without succumbing to decoherence, and scaling randomized or learning-based estimation to many-body devices. Each represents both a barrier and an opportunity for innovation.

Looking ahead, we envision a roadmap for QFI-driven quantum metrology. By 2025, efforts will likely consolidate around identifying “QFI-friendly” noise environments and refining theoretical bounds for realistic channels. By 2028, QEC-enhanced protocols could achieve proof-of-principle demonstrations where active error management restores Heisenberg-like scaling. By 2031, multiparameter estimation and compatible measurement strategies should move from theoretical proposals to experimental validation, particularly in many-body platforms. By 2035, the integration of QFI with hybrid quantum technologies—including distributed sensor networks and machine learning–assisted devices—could deliver practical quantum advantage in real-world sensing tasks.

This progression is neither linear nor exclusive: advances in one domain will inform others. For example, scalable estimation techniques developed for solid-state systems may find application in atomic clocks; conversely, noise insights from photonics could shape distributed networks. What unites these directions is the recognition that QFI is not only a diagnostic of resources but also a design principle for technologies. Framing QFI as a catalyst for quantum advantage ensures that its role will extend beyond bounding performance to shaping the trajectory of quantum sensing in the decades to come.

Figure 4.

Roadmap for QFI (2025–2035).

Figure 4.

Roadmap for QFI (2025–2035).

6. Conclusions

Quantum Fisher information (QFI) has matured from a theoretical construct into a versatile framework that bridges quantum information theory, condensed-matter physics, and experimental metrology. Over the past decade, it has proven invaluable as both a diagnostic—certifying entanglement depth, coherence, and resource scaling—and as a benchmark for comparing platforms ranging from photonics and atomic clocks to solid-state devices and distributed networks.

Yet QFI’s future impact depends on whether its insights can be operationalized into practical protocols. Noise management through non-Markovian effects and QEC, measurement compatibility in multiparameter estimation, robustness of critical many-body systems, and scalable estimation methods remain central open problems. Progress on these fronts will determine if QFI can deliver not only theoretical bounds but also real quantum advantage in noisy intermediate-scale quantum devices.

As outlined in our roadmap, the next decade offers a clear research trajectory: from identifying favorable noise environments and demonstrating QEC-enhanced sensing, to validating multiparameter strategies and integrating QFI into hybrid, learning-assisted platforms. By embracing QFI as both a unifying diagnostic and a design principle, the community has the opportunity to transform precision sensing from a conceptual frontier into one of the earliest tangible applications of the quantum revolution.

References

- Paris, M. G. A. Quantum estimation for quantum technology. Int. J. Quantum Inf. 2009, 7, 125–137. [CrossRef]

- Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Advances in quantum metrology. Nat. Photonics 2011, 5, 222–229. [CrossRef]

- Demkowicz-Dobrzański, R., Jarzyna, M. & Kołodyński, J. Quantum limits in optical interferometry. Prog. Opt. 2015, 60, 345–435. [CrossRef]

- Pezzè, L. & Smerzi, A. Quantum theory of phase estimation. In Atom Interferometry (eds Tino, G. M. & Kasevich, M. A.) 691–741 (IOS Press, 2014).

- Tóth, G. & Apellaniz, I. Quantum metrology from a quantum information science perspective. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 2014, 47, 424006. [CrossRef]

- Pezzè, L. et al. Quantum metrology with nonclassical states of atomic ensembles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2018, 90, 035005. [CrossRef]

- Friis, N. et al. Entanglement witnesses from Fisher information. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 117, 010402.

- Hauke, P., Heyl, M., Tagliacozzo, L. & Zoller, P. Measuring multipartite entanglement through dynamic susceptibilities. Nat. Phys. 2016, 12, 778–782. [CrossRef]

- Escher, B. M., de Matos Filho, R. L. & Davidovich, L. General framework for estimating the ultimate precision limit in noisy quantum-enhanced metrology. Nat. Phys. 2011, 7, 406–411. [CrossRef]

- Demkowicz-Dobrzański, R. & Maccone, L. Using entanglement against noise in quantum metrology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 250801. [CrossRef]

- Chaves, R., Brask, J. B., Markiewicz, M., Kołodyński, J. & Acín, A. Noisy metrology beyond the standard quantum limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 120401. [CrossRef]

- Knysh, S., Chen, E. H. & Durkin, G. A. True limits to precision via unique quantum probe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 95, 260502.

- Smirne, A., Kołodyński, J., Huelga, S. F. & Demkowicz-Dobrzański, R. Ultimate precision limits for noisy frequency estimation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 120801. [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, Y., Benjamin, S. C. & Fitzsimons, J. Magnetic field sensing beyond the standard quantum limit using 10-spin NOON states. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 86, 012103. [CrossRef]

- Chin, A. W. et al. Quantum metrology in non-Markovian environments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 233601. [CrossRef]

- Smirne, A., Lim, H.-T., Huelga, S. F. & Plenio, M. B. Quantum metrology with non-Markovian noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 120801. [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, C., Buscemi, F., Bordone, P. & Paris, M. G. A. Quantum metrology with non-Markovian environments. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 89, 032114. [CrossRef]

- Dür, W., Skotiniotis, M., Fröwis, F. & Kraus, B. Improved quantum metrology using quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 080801. [CrossRef]

- Arrad, G., Vinkler, Y., Aharonov, D. & Retzker, A. Increasing sensing resolution with error correction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 150801. [CrossRef]

- Kessler, E. M., Lovchinsky, I., Sushkov, A. O. & Lukin, M. D. Quantum error correction for metrology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 150802. [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Martí, D. A., Gefen, T., Aharonov, D., Retzker, A. & Plenio, M. B. Quantum error correction-enhanced magnetometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 200501. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S., Zhang, M., Preskill, J. & Jiang, L. Achieving the Heisenberg limit in quantum metrology using quantum error correction. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 78. [CrossRef]

- Layden, D., Zhou, S., Cappellaro, P. & Jiang, L. Ancilla-free quantum error correction codes for quantum metrology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 040502. [CrossRef]

- Kessler, E. M. et al. Quantum error correction for precision measurement. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 86, 012116. [CrossRef]

- Unden, T. et al. Quantum metrology enhanced by repetitive quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 230502. [CrossRef]

- Gefen, T., Aharonov, D. & Retzker, A. Error correction for quantum sensing. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2019, 1, 94–97.

- Demkowicz-Dobrzański, R., Czajkowski, J. & Sekatski, P. Adaptive strategies for quantum metrology. New J. Phys. 2019, 21, 113053.

- Albarelli, F., Barbieri, M., Genoni, M. G. & Gianani, I. A perspective on multiparameter quantum metrology: from theoretical tools to applications in quantum imaging. Phys. Lett. A 2020, 384, 126311. [CrossRef]

- Ragy, S., Jarzyna, M. & Demkowicz-Dobrzański, R. Compatibility in multiparameter quantum metrology. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 94, 052108. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, J., Yang, Y. & Hayashi, M. Quantum Fisher information matrices and multiparameter estimation. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 2020, 53, 453001.

- Szczykulska, M., Baumgratz, T. & Datta, A. Multi-parameter quantum metrology. Adv. Phys. X 2016, 1, 621–639. [CrossRef]

- Šafránek, D. Simple expression for the quantum Fisher information matrix. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 95, 052320.

- Proctor, T. J., Knott, P. A. & Dunningham, J. A. Multiparameter estimation in networked quantum sensors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 080501. [CrossRef]

- Rubio, J., Knott, P. A., Proctor, T. J. & Dunningham, J. A. Quantum sensing networks for multiparameter estimation. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 2020, 53, 344001. [CrossRef]

- Zanardi, P., Paris, M. G. A. & Campos Venuti, L. Quantum criticality as a resource for quantum estimation. Phys. Rev. A 2008, 78, 042105. [CrossRef]

- Hauke, P., Cucchietti, F. M., Tagliacozzo, L., Deutsch, J. M. & Lewenstein, M. Can one trust quantum simulators? Rep. Prog. Phys. 2012, 75, 082401. [CrossRef]

- Frérot, I. & Roscilde, T. Quantum critical metrology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 020402. [CrossRef]

- Pezzè, L., Gabbrielli, M., Lepori, L. & Smerzi, A. Multipartite entanglement in topological quantum phases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 250401. [CrossRef]

- Gabbrielli, M., Pezzè, L. & Smerzi, A. Multipartite entanglement at finite temperature critical points. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 070401.

- Rams, M. M., Mohseni, M. & Życzkowski, K. Quantum metrology at quantum critical points. New J. Phys. 2021, 23, 033034.

- Zhou, H. et al. Simultaneous estimation of magnetic field and temperature in spin models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 220503.

- Gebhart, V., Nichols, R. & Paris, M. G. A. Quantum multiparameter estimation in many-body systems. Phys. Rev. A 2020, 102, 062601.

- Šafránek, D. & Demkowicz-Dobrzański, R. Multiparameter estimation with critical systems. New J. Phys. 2022, 24, 043033.

- Demkowicz-Dobrzański, R. et al. Multiparameter quantum metrology with generalized measurements. New J. Phys. 2023, 25, 063004.

- Sidhu, J. S. & Kok, P. Geometric perspective on multiparameter quantum metrology. AVS Quantum Sci. 2020, 2, 014701.

- Caves, C. M. Quantum-mechanical noise in an interferometer. Phys. Rev. D 1981, 23, 1693–1708. [CrossRef]

- Leroux, I. D., Schleier-Smith, M. H. & Vuletić, V. Implementation of cavity squeezing of a collective atomic spin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 250801. [CrossRef]

- Hosten, O., Engelsen, N. J., Krishnakumar, R. & Kasevich, M. A. Measurement noise 100 times lower than the quantum projection limit using entangled atoms. Nature 2016, 529, 505–508. [CrossRef]

- Elben, A. et al. Randomized measurements of entanglement and coherence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 200501.

- Huang, H.-Y. et al. Predicting many-body quantum dynamics with deep learning. Nat. Phys. 2020, 16, 1050–1056.

- Proctor, T. J. et al. Measuring multiparameter quantum metrological usefulness of noisy states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 020502.

- Koczor, B. & Benjamin, S. C. Estimating quantum Fisher information from randomized measurements. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2019, 12, 064044.

Table 1.

Open Challenges in QFI.

Table 1.

Open Challenges in QFI.

| Domain |

Typical Platform / Model |

Scaling Law |

Key Achievements (last decade) |

Open Challenges |

| Noise Models |

Markovian, Non-Markovian, Correlated Noise |

SQL → Heisenberg-like |

Taxonomy of noise impacts, partial QEC integration |

Realistic noise-tailored bounds, correlated noise handling |

| Platforms – Photonics |

Squeezed light, interferometers |

∼ 1/N (with squeezing) |

LIGO-level gravitational wave detection |

Loss resilience, scalable entanglement |

| Platforms – Cold Atoms / Clocks |

Spin-squeezed ensembles, optical clocks |

∼ 1/N + corrections |

Record clock precision, spin squeezing benchmarks |

Decoherence in large ensembles, multiparameter estimation |

| Platforms – Solid-State |

NV centers, superconducting qubits |

∼ T² scaling (coherence) |

Room-temp magnetometry, nanoscale sensing |

Coherence extension, noise-protected protocols |

| Networks / Distributed |

Multi-node sensors, hybrid quantum-classical |

≤ ∑F_Q (network bound) |

Synchronization demos, first distributed protocols |

Scalability, latency, hybrid ML-QFI protocols |

| Theory & Bounds |

Quantum Cramér–Rao, Bayesian, multiparameter |

Var ≥ 1/F_Q |

Generalized QFI bounds, geometry of estimation |

Tight multiparameter bounds, resource trade-offs |

| Applications |

Metrology, sensing, biomedical, navigation |

Context-dependent |

Quantum-enhanced sensing benchmarks |

Integration with infrastructure, cost-effective deployment |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).