Introduction

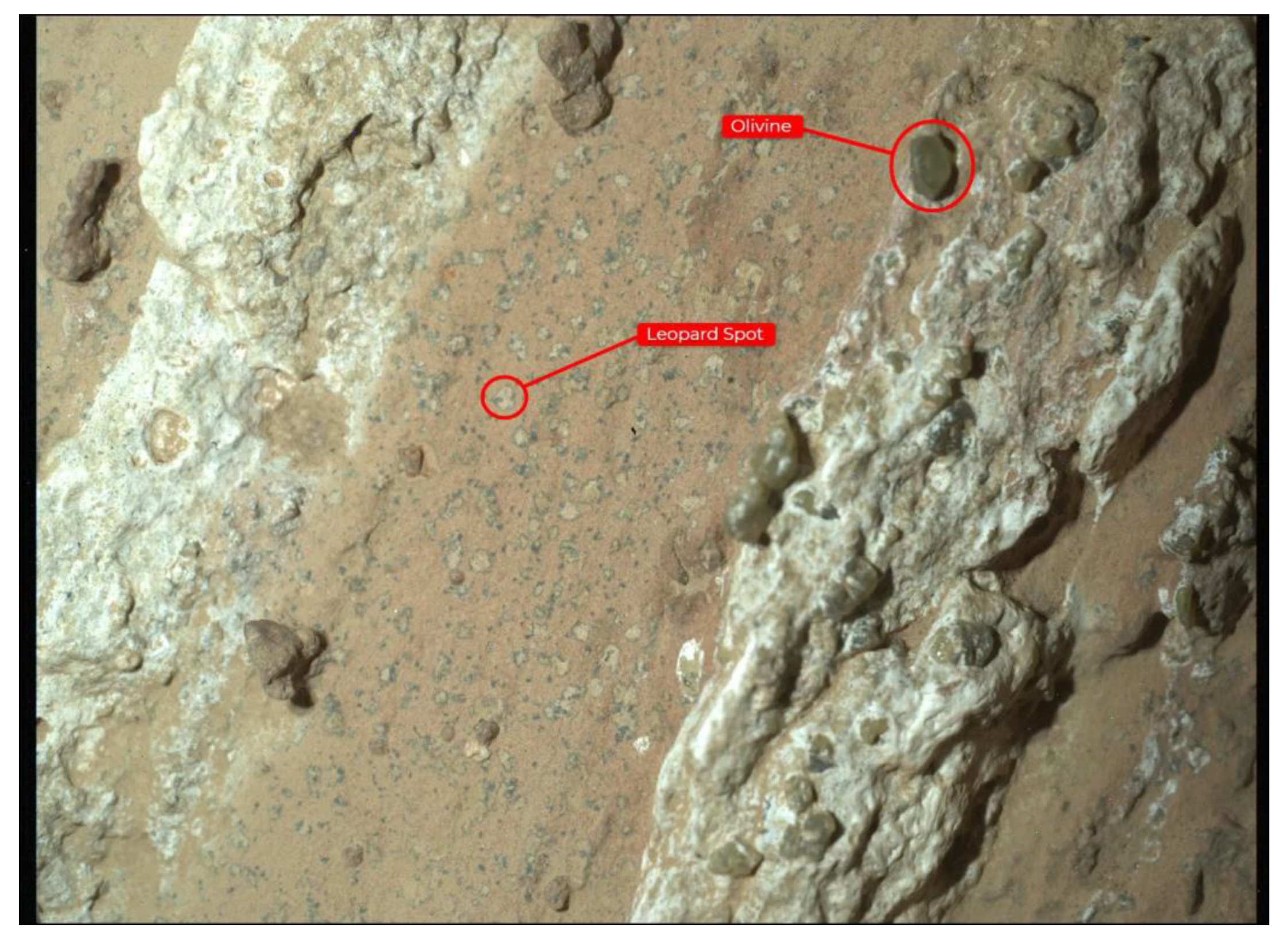

On Sept. 11, 2025, NASA held a press conference revealing that Perseverance has identified features in a Jezero Crater rock suggestive of ancient microbial processes. The rock, nicknamed “Cheyava Falls”, was cored in July 2024 (sample “Sapphire Canyon”) from sedimentary outcrops in the Bright Angel Formation. The rover’s instruments found “leopard spots” and “poppy-seed” shaped splotches on this reddish mudstone. These spots contain iron- and phosphorus-rich minerals (hydrated iron phosphate and iron sulfide) that on Earth often form via microbial redox reactions. As Acting NASA Administrator Sean Duffy noted, this “potential biosignature” is “the closest we have ever come to discovering life on Mars”, though he and scientists emphasized that life itself has not been found (NASA, 2025).

Findings

Perseverance imaged and analyzed centimeter-scale spots and nodules in the rock that resemble terrestrial reduction halos. These are concentric rings and bleached zones (“leopard spots”) with dark centers (“poppy seeds”) caused by localized chemistry. High-resolution PIXL and SHERLOC scans showed that each black-rimmed splotch is enriched in iron phosphate (likely vivianite) and iron sulfide (likely greigite) (Hurowitz et al., 2025). On Earth, vivianite commonly forms in wet sediments around decaying organic matter, and greigite is often produced by sulfate-reducing microbes. The pattern (spots surrounded by rings) is nearly identical to features produced by microbial iron/sulfur cycling in Earth’s mudstones. Scientists on the mission noted that these textures are “easy to explain with early Martian life but very difficult to explain with only geological processes” (Hurowitz et al., 2025).

The Bright Angel mudstone contains organic carbon along with iron, sulfur, phosphorus and oxidized iron (rust) (Kizovski et al., 2025; Hurowitz et al., 2025). Instruments found that the spots carry a mineral signature of vivianite and greigite (Hurowitz et al., 2025). Both NASA scientists and independent analysts point out that on Earth, these minerals appear when microbes “eat” organic carbon and “breathe” iron or sulfate (Hurowitz et al., 2025). As NASA astrobiologist Joel Hurowitz explained, “on Earth, reactions like these, which combine organic matter and chemical compounds in mud to form new minerals like vivianite and greigite, are often driven by the activity of microbes” (NASA, 2025).

The team defines this find as a potential biosignature, a substance or structure possibly of biological origin but not yet confirmed. NASA’s press release and Hurowitz’s team emphasize caution; similar minerals can form abiotically (e.g., via heat or acid). However, the Cheyava Falls rock shows no evidence of high-temperature or acidic alteration (Kizovski et al., 2025; Hurowitz et al., 2025). As they put it, “All the ways we have of examining these rocks on the rover suggest that they were never heated in a way that could produce the leopard spots and poppy seeds” (Hurowitz et al., 2025). That suggests that the abiotic pathways known on Earth are unlikely here. In summary, the rock’s textures, chemistry, and organic content are so striking that Hurowitz et al. conclude they “warrant consideration as ‘potential biosignatures’” (Hurowitz et al., 2025). Image of the

“Cheyava Falls” rock taken by the WATSON instrument on NASA’s Perseverance rover (July 18, 2024) shown in

Figure 1.

Perseverance’s PIXL X-ray spectrometer and SHERLOC Raman spectrometer mapped the spots. They found organic molecules (a carbonaceous G-band signal) colocated with vivianite and greigite, indicating redox reactions between carbon, iron, and sulfur. The combination of nutrients (C, S, P, Fe^3+) in the mudstone could have powered microbial life. As Hurowitz noted, the rock’s chemistry “could have been a rich source of energy for microbial metabolisms”. However, he and colleagues stress that “chemical processes could cause similar reactions in the absence of biology,” so more data (ideally Earth lab analysis) is needed (Hurowitz et al., 2025).

The Nature paper makes clear that definitive proof awaits laboratory analysis of the actual rock sample on Earth (Hurowitz et al., 2025). The Perseverance cache contains the Sapphire Canyon core, and mission planners hope to return it. As Dr. Tice told reporters, bringing the sample home would allow searches “for microfossils if they exist” and isotopic studies far beyond rover capabilities. Meanwhile, the study adds a new category of “biosignature” features for Mars researchers to examine (NASA, 2025).

In summary, NASA’s Sep. 11 announcement centers on a Perseverance rock sample with intricate “leopard spot” mineral textures and organic-rich chemistry consistent with microbe-driven reactions. These clues, iron-phosphate and iron-sulfide patterns entwined with carbon, meet the agency’s criteria for a potential biosignature. The findings have been peer-reviewed (Hurowitz et al., 2025). While tantalizing, the evidence is not conclusive; NASA and scientists reiterate that alternative explanations remain possible and that only the return of the sample to Earth will provide the final answer (Hurowitz et al., 2025). Based on the current data, let’s speculate on the possibility of an ancient microorganism.

Analysis and Speculation of the Findings

Jezero’s Paleoenvironment

Jezero crater (~45 km diameter) hosted a lake with river-fed deltas around 3.8–3.2 Ga (Kizovski et al.,2025; Mangold et al., 2020). Early Mars likely had a dense CO₂–H₂ atmosphere creating a temperate, “warm and wet” climate with mean temperatures near or above freezing (Hurowitz et al., 2025; Ramirez et al., 2014; Wordsworth, 2016). The sedimentary record, including mudstones and layered beds, indicates episodic river flows and persistent standing water (Hurowitz et al., 2025). Spectroscopy suggests that these waters were briny or saline, and geochemical proxies imply a near-neutral pH buffered by Mg–Fe carbonates. Overall, Jezero’s environment was cold by Earth standards but had hydrous, anoxic, and chemically diverse conditions broadly compatible with microbial habitability. (Hurowitz et al., 2025).

Potential Metabolic Pathways

Perseverance detected rich redox chemistry in these sediments, with abundant oxidized iron, phosphorus, sulfur, and organic carbon (Hurowitz et al., 2025). Micron-scale nodules of vivianite-group minerals (ferrous iron phosphate) and greigite (iron sulfide) were observed in association with organic-rich layers. On Earth, such minerals often arise in water-rich, low-temperature environments influenced by microbial metabolisms (Hurowitz et al., 2025). On Earth, vivianite precipitates where Fe(III)-reducing bacteria act on organic detritus, and greigite often forms via biological sulfate reduction. Thus, the presence of Fe³⁺ (as oxidized iron), sulfate, and phosphate in Jezero’s waters could fuel chemosynthesis. In fact, rover scientists note that these conditions are consistent with microbes “eating organic matter and ‘breathing’ rust and sulfate” (Hurowitz et al., 2025).

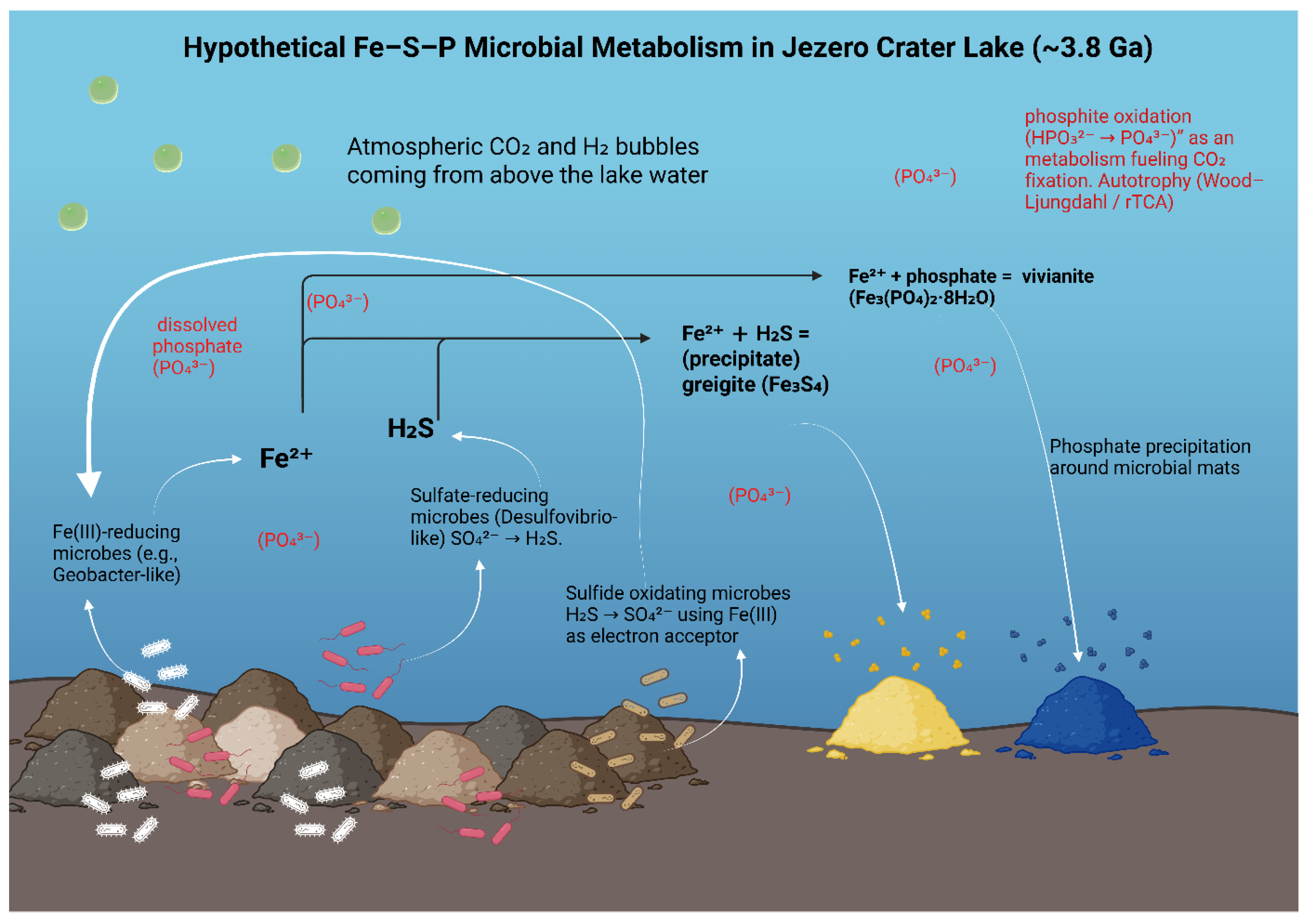

Analogous to Geobacter and Desulfovibrio, Martian microbes could have reduced Fe(III) to Fe²⁺ and SO₄²⁻ to H₂S. The resulting sulfide would combine with Fe²⁺ to precipitate greigite. Conversely, sulfide-oxidizers (e.g., MISO bacteria) could recycle H₂S back to sulfate using Fe(III) as an electron acceptor, completing a coupled Fe–S cycle (Picard et al., 2018; Berg et al., 2020). On Mars, one group of microbes could produce sulfide and another consume it, consistent with the spotted mineral textures.

If reduced phosphorus (phosphite, HPO₃²⁻) was available from basalt alteration or meteoritic sources, microbes could have oxidized it to phosphate for energy. Laboratory studies show phosphite dehydrogenase can drive CO₂ fixation via phosphite oxidation (Figueroa et al., 2018). Even without phosphite, dissimilatory phosphate reduction under anoxic conditions could cycle phosphorus (Mao et al., 2023).

With abundant CO₂, autotrophic pathways such as the Wood–Ljungdahl or reverse TCA cycles are plausible. Detected organic carbon (Raman “G-band”) could also support heterotrophy. If H₂ concentrations were elevated, methanogens could generate CH₄ from CO₂, echoing early Earth conditions.

Together, these metabolisms suggest that Martian microbes, if present, would likely have been anaerobic chemolithotrophs or organotrophs exploiting Fe, S, and P redox couples.

Cellular Adaptations

If such organisms existed, their physiology would have required resilience to Jezero’s environmental stresses. Cells may have produced extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) to trap minerals and organics, forming biofilms. On Earth, vivianite often nucleates on decomposing biomass (Rothe et al., 2016), suggesting Martian mats could serve similar roles. Implying Martian mats could nucleate Fe–P minerals. Used conductive appendages such as type-IV pili for extracellular electron transfer, analogous to MISO bacteria adhering to Fe-oxides. Cell membranes would need robust chemistry (e.g., archaeal ether lipids or bacterial hopanoids) to resist UV and oxidants. Pigments (carotenoids, melanin-like) could shield against radiation. Biochemistry would be dominated by iron–sulfur proteins (ferredoxins, cytochrome-like) and phosphate-based energy carriers (ATP/GTP-like), given the Fe/S/P-rich setting. Cells could accumulate polyphosphate granules and sulfur globules during nutrient-rich periods, buffering against lean times. These reserves also sequester key elements (P and S) for later use. Hypothetical Fe–S–P microbial metabolism cycle in Jezero’s ancient lake (~3.8 Ga) is demonstrated in

Figure 2.

The abundance of phosphorus and organic matter also suggests that genetic polymers with phosphate backbones (DNA/RNA-like) were feasible, pointing toward a biochemistry not radically different from Earth’s.

Community and Ecosystem-Level Analogues

At the community scale, Jezero’s microbial ecosystem may have resembled anaerobic wetlands or lakebeds on Earth. Stratified mats could have cycled nutrients; surface layers oxidize organics and reduce sulfate and Fe(III), and deeper layers oxidize sulfide while reducing iron (Toner et al., 2012; Quevedo et al., 2021). This activity would produce the spotted Fe–P mineral textures observed by Perseverance.

Over time, microbial mats may have cemented sediments into lithified nodules, preserving biosignature structures. Periodic drying would force communities into dormancy (spores or cysts-like), with rapid regrowth upon rehydration (Bradley et al., 2025). In such a system, carbon, nitrogen, sulfur, and phosphorus would be internally recycled, while atmospheric CO₂ (and possibly H₂) provided external inputs (Baumann et al., 2022). Taken together, these processes suggest a self-sustaining microbial ecosystem functionally comparable to Earth’s anaerobic wetlands, yet shaped by Mars’s unique Fe–S–P geochemistry. Although Perseverance has not yet identified nitrogen-bearing minerals in Jezero’s sediments, nitrogen cycling cannot be excluded. On Earth, microbial processes such as denitrification, anammox, and nitrogen fixation operate in tandem with Fe–S redox metabolisms in lakebeds and wetlands, sustaining community productivity under anoxia (Baumann et al., 2022). If even trace nitrate or ammonium was available on early Mars, analogous pathways could have supported or complemented Fe–S–P metabolisms in Jezero’s ecosystem.

Implications

The discovery of mineral–organic associations in Jezero’s sediments has implications beyond Mars itself. If these structures indeed reflect microbial metabolisms, they strengthen the case that Mars once hosted a biosphere with striking parallels to Earth’s. The co-location of carbon, iron, sulfur, and phosphorus, coupled with microbially plausible mineral textures, suggests that life on both planets may have relied on similar geochemical niches. This raises the possibility that the fundamental rules of biochemistry are not unique to Earth but emerge naturally under comparable conditions.

A further implication concerns interplanetary exchange. Meteorites of Martian origin, such as ALH84001 recovered from Antarctica, demonstrate that rocks are routinely ejected from Mars and delivered to Earth and vice versa (McKay et al., 1996). If life or prebiotic systems arose on either planet, panspermia through impact transfer becomes a viable mechanism for spreading biology across the inner solar system. Microbes shielded within ejecta could, in principle, survive interplanetary transit and seed habitable environments elsewhere. Thus, Jezero’s potential biosignatures may not only document an independent Martian biosphere but also hint at deep genetic or biochemical kinship between terrestrial and Martian life.

These findings also reshape the astrobiological framework for exploration. If redox-active microbial metabolisms operated in Jezero’s Lake, similar systems could persist in subsurface aquifers or cryo-protected niches today. More broadly, they underscore that habitable environments and microbial-scale biospheres might be common wherever liquid water, redox gradients, and essential nutrients coincide. The Martian evidence, therefore, carries implications for icy moons such as Europa and Enceladus, and for the general probability of life in the universe.

Beyond its immediate significance, this discovery compels a refinement of how biosignatures are defined and sought in planetary exploration. The co-occurrence of vivianite, greigite, and organic carbon highlights the need to focus not only on single molecular or mineral markers, but on integrated mineral–organic textures that emerge from redox-driven ecosystems. At the same time, caution is essential; both vivianite and greigite can, under certain conditions, precipitate abiotically, which underscores the importance of laboratory-based isotopic analyses and nanoscale imaging once samples are returned to Earth. Earth analog environments, such as ferruginous lakes, wetland sediments, and deltaic mudstones, provide vital testbeds for distinguishing biological from abiotic mineralization pathways, offering methodological frameworks that can be applied directly to Jezero samples. In this sense, the Martian findings do not merely suggest life is possible, but also sharpen the scientific toolkit with which future biosignature claims must be validated.

Conclusion

A carbon-based, anaerobic biosphere using iron–sulfur–phosphate chemistries is fully consistent with Jezero’s ancient lake environment. The co-location of organic carbon with vivianite and greigite is difficult to explain by abiotic processes at low temperature. Indeed, scientists emphasize that known chemistry would require high heat to form these sulfur minerals, so “we have to seriously consider” a biological origin in >3-billion-year-old lake mud (Rothe et al., 2016). These mineral–organic associations meet NASA’s definition of potential biosignatures (Des Marais et al., 2008). Definitive proof will require returned samples and laboratory analysis, but the present evidence is fully compatible with a Martian microbial community adapted to Jezero’s unique geochemistry (Hurowitz et al., 2025). Looking ahead, Jezero Crater should be regarded as a model system for testing hypotheses about ancient extraterrestrial life. The stakes are profound; the eventual return of the Sapphire Canyon core will either substantiate or overturn decades of speculation about Martian biospheres and their resemblance to Earth’s earliest microbial ecosystems. While Fe–S–P metabolisms likely dominated Jezero’s redox landscape, nitrogen cycling should not be overlooked. Even trace nitrate or ammonium could have enabled denitrification, anammox, or nitrogen fixation, providing complementary pathways to sustain community productivity alongside iron, sulfur, and phosphorus metabolisms (Baumann et al., 2022). Confirmation of biogenic origins would reshape our definition of habitable environments and anchor Fe–S–P redox metabolisms as a universal biosignature framework. Even in the absence of definitive life detection, these findings refine the search strategy for astrobiology, guiding exploration not only on Mars but also in analogous environments on icy moons such as Europa and Enceladus, and in exoplanetary systems where redox-active sediments may exist. Jezero’s mineral–organic associations therefore serve as both a critical test case and a springboard for developing the next generation of life-detection missions.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the NASA Perseverance mission team for making the Jezero Crater data publicly available. Gratitude is also extended to colleagues and mentors who provided valuable discussions and encouragement during the preparation of this work. Also, I sincerely thank Prof. Nuran Çiçek for taking me into her care, guiding my work, and providing understanding and belief in me throughout this process.

Author Disclosure Statement

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Funding Statement

No specific funding was received for this work.

Data Availability

No new data were generated or analyzed in support of this research.

References

- Baumann, K. B. L., Thoma, R., Callbeck, C. M., Niederdorfer, R., Schubert, C. J., Müller, B., Lever, M. A., & Bürgmann, H. (2022). Microbial nitrogen transformation potential in sediments of two contrasting lakes is spatially structured but seasonally stable. mSphere, 7(1), e01013-21. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J. A., et al. (2025) Microbial dormancy as an ecological and biogeochemical regulator on Earth, Nature Communications, 16, Article 3909. [CrossRef]

- Berg, J. S., Duverger, A., Cordier, L., Laberty-Robert, C., Guyot, F., & Miot, J. (2020) Rapid pyritization in the presence of a sulfur/sulfate-reducing bacterial consortium enriched from ferruginous and phosphate-rich lake water, Scientific Reports, 10: 8264. [CrossRef]

- Des Marais, D.J., Nuth, J.A., Allamandola, L.J., Boss, A.P., Farmer, J.D., Hoehler, T.M., Jakosky, B.M., Meadows, V.S., Pohorille, A., Runnegar, B. & Spormann, A.M., 2008. The NASA Astrobiology Roadmap. Astrobiology, 8(4), pp.715–730. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, I. A., Barnum, T. P., Somasekhar, P. Y., Carlström, C., et al. (2018) Metagenomics-guided analysis of microbial chemolithoautotrophic phosphite oxidation yields evidence of a seventh natural CO₂ fixation pathway, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 115(1): E92-E101. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, D. E., Dang, Y., Walker, D. J. F., & Lovley, D. R. (2016) The electrically conductive pili (e-pili) of Geobacter species are essential for extracellular electron transfer to Fe(III) oxides, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 80(4), pp. 1219-1224. [CrossRef]

- Hurowitz, J.A., Tice, M.M., Allwood, A.C., Cable, M.L., Hand, K.P., Murphy, A.E., et al. (2025). Redox-driven mineral and organic associations in Jezero Crater, Mars. Nature, 645, pp. 332–340. [CrossRef]

- Kizovski, T.V., Schmidt, M.E., O’Neil, L., Jones, M.W.M., Tosca, N.J., Klevang, D.A., Hurowitz, J.A., Adcock, C.T., Hausrath, E.M., Siebach, K.L., Wolf, Z.U., Sharma, S., Vanbommel, S.J., Mccubbin, F.M., Cloutis, E., Cable, M.L., Liu, Y., Clark, B.C., Treiman, A.H., Tice, M.M., Catling, D.C., Maki, J., Bosak, T., Weiss, B.P., Fairén, A.G., Christian, J.R., Knight, A.L., Shumway, A.O., Randazzo, N.R., Jørgensen, P.S., Lawson, P.R., Wade, L., Heirwegh, C., Elam, W.T., Allwood, A.C., 2025. Fe-phosphates in Jezero Crater as evidence for an ancient habitable environment on Mars. Nature Communications 16. [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z., Fleming, J. R., Mayans, O., Frey, J., Schleheck, D., Schink, B., & Müller, N. (2023). AMP-dependent phosphite dehydrogenase, a phosphorylating enzyme in dissimilatory phosphite oxidation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 120(45), e2309743120. [CrossRef]

- McKay, D.S., Gibson, E.K., Thomas-Keprta, K.L., Vali, H., Romanek, C.S., Clemett, S.J., Chillier, X.D.F., Maechling, C.R. & Zare, R.N. (1996) Search for past life on Mars: Possible relic biogenic activity in Martian meteorite ALH84001, Science, 273(5277), pp. 924–930. [CrossRef]

- NASA (2025). Perseverance finds a rock with “leopard spots” in Jezero Crater. NASA Science. Available at: https://www.nasa.gov/news-release/nasa-says-mars-rover-discovered-potential-biosignature-last-year/.

- Toner, B. M., Berquó, T. S., Michel, F. M., Sorensen, J. V., Templeton, A. S., & Edwards, K. J. (2012). Mineralogy of iron microbial mats from loihi seamount. Frontiers in Microbiology, 3, 118. [CrossRef]

- Picard, A., Amelinckx, S., Benning, L. G., Helmle, K., & Girguis, P. R. (2018). Sulfate-reducing bacteria influence the nucleation and growth of mackinawite and greigite under low-temperature anoxic conditions, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 220, pp. 367-384. [CrossRef]

- Quevedo, C. P., et al. (2021) The Potential Role of S- and Fe-Cycling Bacteria on Fe-bearing Mineral Precipitation in Soils and Sediments Subject to Fluctuating Redox Conditions, Minerals, 11(10): 1148. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, R. M., Kopparapu, R., Zugger, M. E., Robinson, T. D., Freedman, R., & Kasting, J. F. (2014). Warming early Mars with CO₂ and H₂. Nature Geoscience, 7(1), 59–63. [CrossRef]

- Rothe, M., Takahashi, R., Itoh, K., Watanabe, M., & Kida, K. (2016) The occurrence, identification and environmental significance of vivianite in paddy field soil, Japan, Science of the Total Environment, 566-567, pp. 1035-1044. [CrossRef]

- Wordsworth, R. D. (2016). The Climate of Early Mars. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 44, 381–408. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).