Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Molecular Plant Mechanisms for Combating Nematodes Infecting Crops

3. Current Problems Linked to Using R-Genes with Possible Genetic Solutions

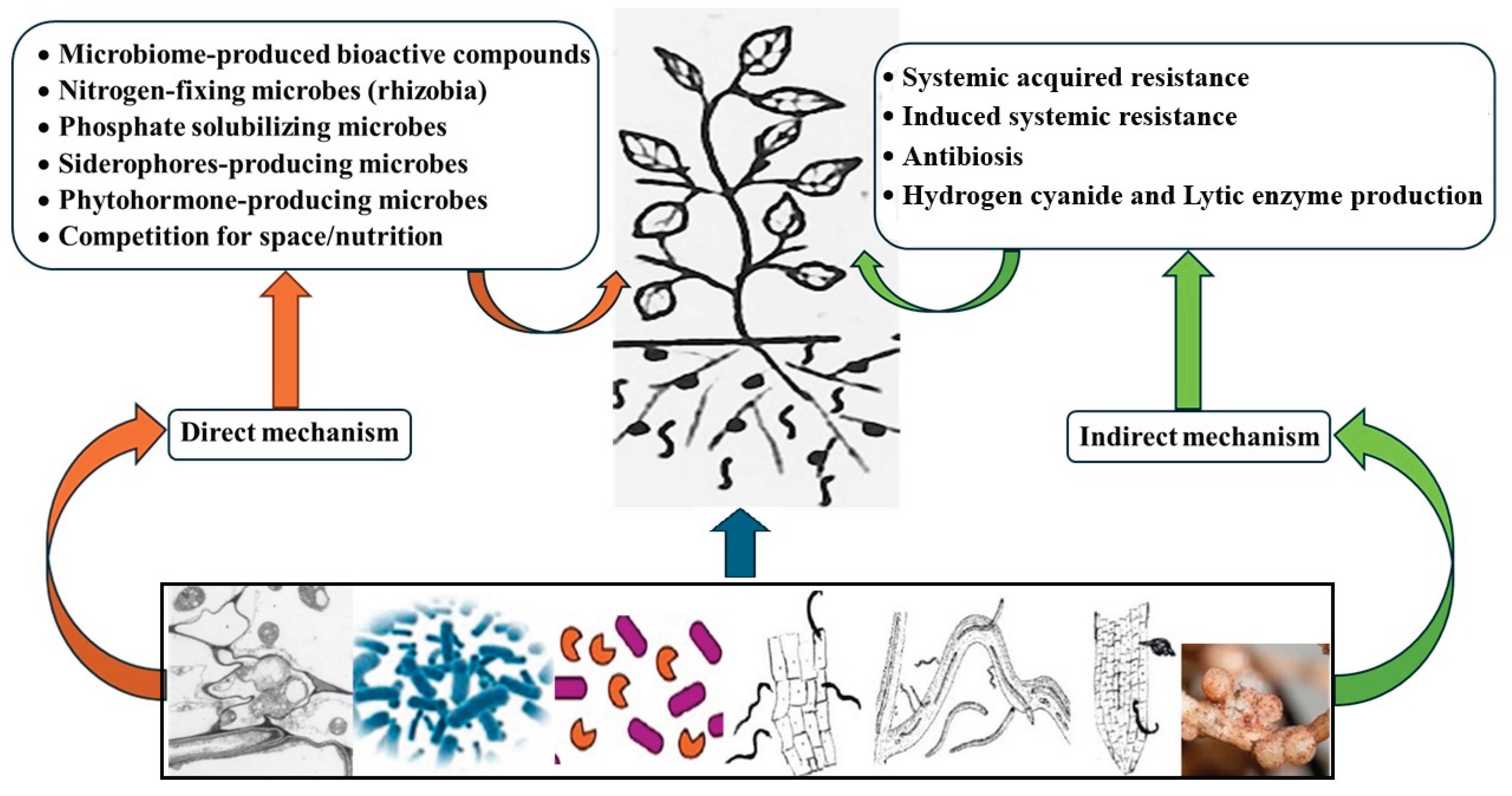

4. Beneficial Roles of Plant-Associated Microorganisms

4.1. General Benefits of These Microorganisms

4.2. Categories of Plant Microbiomes That Activate Its Immunity

4.4. Examples of Microbiomes That Molecularly Activate Plant Immunity

5. Upgrading Microbiome Role against PPN Species

5.1. Grasp of Basic Factors Governing Composition and Activity of Microbiomes

5.2. Manipulation of the Plant Microbiome Against PPNs

5.2.1. Consideration of Biotic and Abiotic Factors in the Settings

5.2.2. Examining the Exact Interactions for Components of the Microbial Consortia

5.2.3. Leveraging Plant Microbiomes for SAR Induction in Advanced Strategies

5.3. Widening Microbiome Role Against Further Important PPN Species

6. Microbiome Merits Serve to Raise Awareness and Increase Its Adoption

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Integrated nematode management strategies: Optimization of combined nematicidal and multi-functional inputs. Plants 2025, 14, 1004. [CrossRef]

- Sikora, R.A.; Desaeger, J.; Molendijk, L.P.G. (Eds.) Integrated Nematode Management: State-of-the-Art and Visions for the Future; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2022; 498p.

- EPA. Aldicarb; Cancellation Order for Amendments to Terminate Usesfed; Regist; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- EPA. Carbofuran; Product Cancellation Orderfed; Regist; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Molinari, S.; Leonetti, P. Resistance to plant parasites in tomato is induced by soil enrichment with specific bacterial and fungal rhizosphere microbiome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15416. [CrossRef]

- Robert-Seilaniantz, A.; Grant, M.; Jones, J.D. Hormone crosstalk in plant disease and defense: More than just jasmonate-salicylate antagonism. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 2011, 49, 317–343. [CrossRef]

- El-Sappah, A.H.; Islam, M.M.; El-Awady, H.H.; Yan, S.; Qi, S.; Liu, J.; Cheng, G.-T.; Liang, Y. Tomato natural resistance genes in controlling the root-knot nematode. Genes 2019, 10, 925. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Putker, V.; Goverse, A. Molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in host-specific resistance to cyst nematodes in crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 641582. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Understanding molecular plant–nematode interactions to develop alternative approaches for nematode control. Plants 2022, 11, 2141. [CrossRef]

- Klessig, D.F.; Manohar, M.; Baby, S.; Koch, A.; Danquah, W.B.; Luna, E.; Park, H.J.; Kolkman, J.M.; Turgeon, B.G.; Nelson, R. 1009 Nematode ascaroside enhances resistance in a broad spectrum of plant–pathogen systems. J. Phytopathol. 2019, 167, 1010 265-272.

- Sato, K.; Kadota, Y.; Shirasu, K. Plant immune responses to parasitic nematodes. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1165. [CrossRef]

- Dangl, J.L.; Jones, J.D. Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature 2001, 411, 826–833.

- Molinari, S. Can the plant immune system be activated against animal parasites such as nematodes? Nematology 2020, 22, 481–492. [CrossRef]

- Glazebrook, J. Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2005, 43, 205-227. [CrossRef]

- Mur, L.A.J.; Kenton, P.; Atzorn, R.; Miersch, O.; Wasternack, C. The outcomes of concentration-specific interactions between salicylate and jasmonate signaling include synergy, antagonism, and oxidative stress leading to cell death. Plant Physiol. 2006, 140, 249-262.

- Domínguez-Figueroa, J.; Gόmez-Rojas, A.; Escobar, C. Functional studies of plant transcription factors and their relevance in the plant root-knot nematode interaction. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1370532. [CrossRef]

- Kyndt, T.; Denil, S.; Haegeman, A.; Trooskens, G.; Bauters, L.; Van Criekinge, W.; et al. Transcriptional reprogramming by root knot and migratory nematode infection in rice. New Phytol. 2012, 196, 887–900. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Lin, B.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, H.; Huang, C.; Sun, T.; Long, C.; Liao, J.; Zhuo, K. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of the susceptibility gene OsHPP04 in rice confers enhanced resistance to rice root-knot nematode. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1134653. [CrossRef]

- Grunewald, W.; Karimi, M.; Wieczorek, K.; Van de Cappelle, E.; Wischnitzki, E.; Grundler, F.; Inzé, D.; Beeckman, T.; Gheysen, G. A role for AtWRKY23 in feeding site establishment of plant-parasitic nematodes. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 358–368. [CrossRef]

- Willig, J.J.; Guarneri, N.; van Loon, T.; Wahyuni, S..; Astudillo-Estévez, I.E.; Xu, L.; Willemsen, V.; Goverse, A.; Sterken, M.G.; Lozano-Torres, J.L.; Bakker, J.; Smant, G. Transcription factor WOX11 modulates tolerance to cyst nematodes via adventitious lateral root formation. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 799-811. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Huang, K.; Liu, R; Lai, Y.; Abad, P.; Favery, B.; Jian, H.; Ling, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xie, B.; Quentin, M.; Mao, Z. The root-knot nematode effector Mi2G02 hijacks a host plant trihelix transcription factor to promote nematode parasitism. Plant Commun. 2024, 5(2), 100723. [CrossRef]

- Chinnapandi, B.; Bucki, P.; Fitoussi, N.; Kolomiets, M.; Borrego, E.; Braun-Miyara, S. Tomato SlWRKY3 acts as a positive regulator for resistance against the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica by activating lipids and hormone-mediated defense-signaling pathways. Plant Signaling Behav. 2019, 14, 1601951. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, J.; Diaz-Manzano, F.E.; Saı́nchez, M.; Rosso, M.N.; Melillo, T.; Goh, T.; et al. A role for LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES-DOMAIN 16 during the interaction Arabidopsis-Meloidogyne spp. provides a molecular link between lateral root and root-knot nematode feeding site development. New Phytol. 2014, 203, 632–645. [CrossRef]

- Molinari, S.; Farano, A.C.; Leonetti, P. Root-knot nematode early infection suppresses immune response and elicits the antioxidant system in tomato. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12602. [CrossRef]

- Llorens, E.; González-Hernández, A.I.; Scalschi, L.; Fernández-Crespo, E.; Camañes, G.; Vicedo, B.; García-Agustín, P. Priming mediated stress and cross-stress tolerance in plants: Concepts and opportunities. In Priming-mediated stress and cross-stress tolerance in crop plants; Hossain, M.A., Liu, F., Burritt, D. J., Fujita, M., Huang, B., Eds; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Seah, S.; Telleen, A.C.; Williamson, V.M. Introgressed and endogenous Mi-1 gene clusters in tomato differ by complex rearrangements in flanking sequences and show sequence exchange and diversifying selection among homologues. Theoret. Appl. Gen. 2007, 114, 1289–1302. [CrossRef]

- Ammiraju, J.S.S.; Veremis, J.C.; Huang, X.; Roberts, P.A.; Kaloshian, I. The heat-stable, root-knot nematode resistance gene Mi-9 from Lycopersicum peruvianum is localized on the short arm of chromosome 6. Theoret. Appl. Gen. 2003, 106, 478–484. [CrossRef]

- Molinari, S. Resistance and virulence in plant-nematode interactions. In Nematodes; Boeri, F., Chung, J.A., Eds.; Nova Science Publisher, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 59–82.

- Devran, Z.; Özalp, T.; Studholme, D.J.; Tör, M. Mapping of the gene in tomato conferring resistance to root-knot nematodes at high soil temperature. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1267399. [CrossRef]

- Kahn, T.W.; Duck, N.B.; McCarville, M.T.A. Bacillus thuringiensis Cry protein controls soybean cyst nematode in transgenic soybean plants. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3380. [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.; Yuan, M.; Wei, H.; Li, J.; Ding, B.; Wang, J.; Lu, W.; Koch, G. Identification of resistant sources from Glycine max against soybean cyst nematode. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1143676. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; He, Y.; Hsiao, T.T.; Wang, C.J.; Tian, Z.; Yeh, K.W. Pyramiding taro cystatin and fungal chitinase genes driven by a synthetic promoter enhances resistance in tomato to root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Plant Sci. 2015, 231, 74–81. [CrossRef]

- Youssef, M.M.A.; Eissa, M.F.M. The rice root nematode, Hirschmanniella oryzae, its identification, economic importance and control measures in Egypt: a review. Arch. Phytopathol. Pl. Protect. 2014, 47, 2340–2351. [CrossRef]

- Mantelin, S.; Thorpe, P.; Jones, J.T. Suppression of plant defences by plant-parasitic nematodes. Adv. Botanical Res. 2015, 73, 325-337. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, R.; Bakker, J.; Gommers, F. Selection of virulent and avirulent lines of Globodera rostochiensis for the H1 resistance gene in Solanum tuberosum ssp. andigena CPC 1673. Rev. Nématol. 1990, 13, 265–268.

- Castagnone-Sereno, P. Genetic variability of nematodes: A threat to the durability of plant resistance genes? Euphytica 2002, 124, 193–199.

- Xu, J.; Narabu, T.; Mizukubo, T.; Hibi, T. A molecular marker correlated with selected virulence against the tomato resistance gene Mi in Meloidogyne incognita, M. javanica and M. arenaria. Phytopathology 2001, 91, 377–382.

- Molinari, S. Antioxidant enzymes in (a)virulent populations of root-knot nematodes. Nematology 2009, 11, 689–697. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Disease complexes involving multiple nematodes. In Nematode Disease Complexes in Agricultural Crops; Khan, M.R., Ed.; CABI, Wallingford, UK, 2025; pp. 219-242. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Optimizing biological control agents for controlling nematodes of tomato in Egypt. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Cont. 2020, 30, 58. [CrossRef]

- Noling, J.W. Nematode management in tomatoes, peppers, and eggplant. University of Florida, IFAS, publication Series no. ENY-032, USA, p 16.

- Hussey, R.S.; Mims, C.W. Ultrastructure of esophageal glands and their secretory granules in the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Protoplasma 1990, 156, 9-18. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Q.; Wei, J.Z.; Tan, A.; Aroian, R.V. Resistance to root-knot nematode in tomato roots expressing a nematicidal Bacillus thuringiensis crystal protein. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2007, 5, 455-464. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Q.; Tan, A.; Voegtline, M.; Bekele, S.; Chen, C.-S.; Aroian, R.V. Expression of Cry5B protein from Bacillus thuringiensis in plant roots confers resistance to root-knot nematode. Biol. Control 2008, 47, 97-102. [CrossRef]

- Urwin, P.E.; Mcpherson, M.J.; Atkinson, H.J. Enhanced transgenic plant resistance to nematodes by dual proteinase inhibitor constructs. Planta 1998, 204, 472-479. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Guzmán, P.; Kumar, A.; de los Santos-Villalobos, S.; Parra-Cota, F.I.; Orozco-Mosqueda, M.d.C.; Fadiji, A.E.; Hyder, S.; Babalola, O.O.; Santoyo, G. Trichoderma species: Our best fungal allies in the biocontrol of plant diseases - A review. Plants 2023, 12, 432. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.J.; Jackson, T.A. Progress in the commercialization of bionematicides. BioControl 2013, 58, 715–722. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Upgrading strategies for managing nematode pests on profitable crops. Plants 2024, 13, 1558. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, D.; Bhagawati, B. Management of Meloidogyne incognita and Rhizoctonia solani complex on okra through integration of Trichoderma viride, Glomus fasciculatum and mustard cake. Indian J. Nematol. 2014, 44, 139–143.

- Youssef, M.M.A.; El-Nagdi, W.M.A.; Abd-El-Khair, H.; Elkelany, U.S.; Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M.; Dawood, M.G. Is use of two Trichoderma species sole or combined with a plant extract effective for the biocontrol Meloidogyne incognita on potato and soil microorganisms diversity? Pakistan J. Nematol. 2023, 41, 153–164. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Biological control agents of plant-parasitic nematodes: A review. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Cont. 2016, 26(2), 423-429. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/pdf/10.5555/20163278720.

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Pasteuria species for nematodes management in organic farms. In Sustainable Management of Nematodes in Agriculture, Vol.2: Role of Microbes-Assisted Strategies. Sustainability in Plant and Crop Protection, vol 19; Chaudhary, K.K., Meghvansi, M.K., Siddiqui, S., Eds; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 265-296. [CrossRef]

- Topalović, O.; Heuer, H. Plant-nematode interactions assisted by microbes in the rhizosphere. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2019, 30, 75-88. [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, C.M.J.; Zamioudis, C.; Berendsen, R.L.; Weller, D.M.; Van Wees, S.C.M.; Bakker, P.A.H.M. Induced systemic resistance by beneficial microbes. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 2014, 52, 347-375. [CrossRef]

- Kour, S.; Sharma, N.; Kumar, D.; Ali, M.; Sharma, R.; Parkirti, P.; Vikram, V.; Ohri, P. Role of beneficial microorganisms in vegetable crop production and stress tolerance. In Growth Regulation and Quality Improvement of Vegetable Crops; Ahammed, G.J., Zhou, J., Eds; Springer: Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Paszkowski, U. Mutualism and parasitism: the yin and yang of plant symbioses. Curr. Opin. Pl Biol. 2006, 8, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Zipfel, C.; Oldoryd, G.E.D. Plant signalling in symbiosis and immunity. Nature 2017, 543, 328-336. [CrossRef]

- Molinari, S.; Leonetti, P. Bio-control agents activate plant immune response and prime susceptible tomato against root-knot nematodes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213230. [CrossRef]

- Pozo,M.J; Azcón-Aguilar, C. Unraveling mycorrhiza-induced resistance. Curr. Opin. Pl Biol. 2007, 10, 393-398. [CrossRef]

- Conrath, U.; Beckers, G.J.M.; Langenbach, C.J.G.; Jaskiewicz, M.R. Priming for enhanced defense. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 2015, 53, 97-119. [CrossRef]

- Vos, C.M.; Tesfahun, A.N.; Panis, B.; De Waele, D.; Elsen, A. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi induce systemic resistance in tomato against the sedentary nematode Meloidogyne incognita and the migratory nematode Pratylenchus penetrans. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2012, 61, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M.; Askary, T.H. Fungal and bacterial nematicides in integrated nematode management strategies. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Cont. 2018, 28, 74. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Optimizing safe approaches to manage plant-parasitic nematodes. Plants 2021, 10, 1911. [CrossRef]

- Schouten, A. Mechanisms involved in nematode control by endophytic fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2016, 54, 121–142. [CrossRef]

- Ghahremani, Z.; Escudero, N.; Saus, E.; Gabaldón, T.; Sorribas, F.J. Pochonia chlamydosporia induces plant-dependent systemic resistance to Meloidogyne incognita. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 945. [CrossRef]

- Könker, J.; Zenker, S.; Meierhenrich, A.; Patel, A.; Dietz, K-J. Pochonia chlamydosporia synergistically supports systemic plant defense response in Phacelia tanacetifolia against Meloidogyne hapla. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1497575. [CrossRef]

- Elshahawy, I.; Saied, N.; Abd-El-Kareem, F.; Abd-Elgawad, M. Enhanced activity of Trichoderma asperellum introduced in solarized soil and its implications on the integrated control of strawberry-black root rot. Heliyon 2024, 10, 1016. [CrossRef]

- Leonetti, P.; Zonno, M.C.; Molinari, S.; Altomare, C. Induction of SA-signaling pathway and ethylene biosynthesis in Trichoderma harzianum-treated tomato plants after infection of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Pl. Cell Rep. 2017, 36, 621-631. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Medina, A.; Fernandez, I.; Lok, G.B.; Pozo, M.J.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Van Wees, S.C.M. Shifting from priming of salicylic acid- to jasmonic acid-regulated defences by Trichoderma protects tomato against the root knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. New Phytol. 2017, 213, 1363-1377. [CrossRef]

- Druzhinina, I.S.; Seidl-Seiboth, V.; Herrera-Estrella, A.; Horwitz, B.A.; Kenerley, C.M.; Monte, E.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Zeilinger, S.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Kubicek, C.P. Trichoderma: the genomics of opportunistic success. Nature Rev. 2011, 9, 749-759. [CrossRef]

- Van Dessel, P.; Coyne, D.; Dubois, T.; De Waele, D.; Franco, J. In vitro nematicidal effect of endophytic Fusarium oxysporum against Radopholus similis, Pratylenchus goodeyi and Helicotylenchus multicinctus. Nematropica 2011, 41, 154-160.

- Waweru, B.W.; Losenge, T.; Kahangi, E.M.; Dubois, T.; Coyne, D. Potential biological control of lesion nematodes on banana using Kenyan strains of endophytic Fusarium oxysporum. Nematology 2013, 15, 101–107. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, A.R.; Sikora, R.A. Biological control of Radopholus similis in banana by combined application of the mutualistic endophyte Fusarium oxysporum strain 162, the egg pathogen Paecilomyces lilacinus strain 251 and the antagonistic bacteria Bacillus firmus. BioControl 2009, 54, 263–272. [CrossRef]

- Kisaakye, J.; Fourie, H.; Haukeland, S.; Kisitu, J.; Nakimera, S.; Cortada, L.; Subramanian, S.; Coyne, D. Endophytic non-pathogenic Fusarium oxysporum-derived dual benefit for nematode management and improved banana (Musa spp.) productivity. Agriculture 2022, 12, 125. [CrossRef]

- Rigobelo, E.C.; Nicodemo, D.; Babalola, O.O.; Desoignies, N. Purpureocillium lilacinum as an agent of nematode control and plant growth-promoting fungi. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1225. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Takishita, Y.; Zhou, G.; Smith, D.L. Plant associated rhizobacteria for biocontrol and plant growth enhancement. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 634796. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Backer, R.; Subramanian, S.; Smith, D. Phytomicrobiome coordination signals hold potential for climate change-resilient agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 634. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.P.; Sharma, C.; Pathak, P.; Kanaujia, A.; Saxena, M.J.; Kalra, A. Management of phyto-parasitic nematodes using bacteria and fungi and their consortia as biocontrol agents. Environ. Sci.: Adv. 2025, 4, 335–354. [CrossRef]

- Myresiotis, C.K.; Vryzas, Z.; Papadopoulu-Mourkidou, E. Enhanced root uptake of acibenzolar-S-methyl (ASM) by tomato plants inoculated with selected Bacillus plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR). Appl. Soil Ecol. 2014, 77, 26–33. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Bacillus species: Prospects and applications for root-knot disease management. In Microbial biostimulants: Biorational pesticides for management of plant pathogens; Ahmad, F., Pandey, R., Eds.; Apple Academic Press: New Jersey, USA, 2025; pp. 79-105. https://appleacademicpress.com/microbial-biostimulants-biorational-pesticides-for-management-of-plant-pathogens/9781774916247.

- Tonelli, M.L.; Figueredo, M.S.; Rodríguez, J.; Fabra, A.; Ibañez, F. Induced systemic resistance-like responses elicited by rhizobia. Pl. Soil 2020, 448, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Pires, D.; Vicente, C.S.L.; Menéndez, E.; Faria, J.M.S.; Rusinque, L.; Camacho, M.J.; Inácio, M.L. The fight against plant-parasitic nematodes: Current status of bacterial and fungal biocontrol agents. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1178. [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.T.; Mitchum, M.G.; Zhang, S.; Wallace, J.G. Li, Z. Soybean microbiome composition and the impact of host plant resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1326882. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Exploiting plant-phytonematode interactions to upgrade safe and effective nematode control. Life 2022, 12, 1916. [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M.S.; Tayyab, M.; Baillo, E.H.; Islam, M.M.; Islam, W.; Li, X. Plant microbiome technology for sustainable agriculture. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1500260. [CrossRef]

- Neal, J.L.; Atkinson, T.G.; Larson, R.I. Changes in the rhizosphere microflora of spring wheat induced by disomic substitution of a chromosome. Can. J. Microbiol. 1970, 16, 153–158. [CrossRef]

- Chaparro, J.M.; Badri, D.V.; Vivanco, J.M. Rhizosphere microbiome assemblage is affected by plant development. ISME J. 2014, 8, 790–803. [CrossRef]

- Bressan, M.; Roncato, M.-A.; Bellvert, F.; Comte, G.; Haichar, F.E.Z.; Achouak, W.; et al. Exogenous glucosinolate produced by Arabidopsis thaliana has an impact on microbes in the rhizosphere and plant roots. ISME J. 2009, 3, 1243-1257. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Wei, X.; Cui, Y.; Gu, X.; Li, X.; Yoshigan, T.; Abd-Elgawad, M.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.; Ruan, W.; Rasmann, S. Direct antagonistic effect of entomopathogenic nematodes and their symbiotic bacteria on root-knot nematodes migration toward tomato roots. Pl Soil 2023, 484, 441-455. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad M.M.M. Transformational technologies for more uptakes of entomopathogenic nematodes. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Cont. 2025, 35:1. [CrossRef]

- Meidani, C.; Savvidis, A.; Lampropoulou, E.; Sagia, A.; Katsifas, E.; Monokrousos, N.; Hatzinikolaou, D.G.; Karagouni, A.D.; Giannoutsou, E.; Adamakis, I.-D.S. et al. The nematicidal potential of bioactive Streptomyces strains isolated from Greek rhizosphere soils tested on Arabidopsis plants of varying susceptibility to Meloidogyne spp. Plants 2020, 9, 699. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Expanding biological control spectra of entomopathogenic nematodes to tick pests. Pakistan J. Nematol. 2025, 43(1), 09-22. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Challenges in field application of biopesticides for successful crop pest management. In Pest management: Methods, applications and challenges; Askary, T., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc., New York, USA, 2022; pp. 331-366. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.; El-Mougy, N.S.; El-Gamal, N.G.; Abdel-Kader, M.M.; Mohamed, M. Protective treatments against soilborne pathogens in citrus orchards. J. Pl. Protect. Res. 2010, 50(4), 512-519.

- Chowdhury, S.P.; Hartmann, A.; Gao, X.; Borriss, R. Biocontrol mechanism by root-associated Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42–a review. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 137829. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Nanonematicides: production, mechanisms, efficacy, opportunities and challenges. Nematology 2024, 26(5), 479-489. [CrossRef]

- Abd-El-Kareem, F.; Elshahawy, I.E.; Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Application of Bacillus pumilus isolates for management of black rot disease in strawberry. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Cont. 2021, 31, 25. [CrossRef]

- Ajijah, N.; Fiodor, A.; Pandey, A.K.; Rana, A.; Pranaw, K. Plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) with biofilm-forming ability: A multifaceted agent for sustainable agriculture. Diversity 2023, 15, 112. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.L.F.; Roberts, D.P. Combinations of biocontrol agents for management of plant-parasitic nematodes and soilborne plant-pathogenic fungi. J. Nematol. 2002, 34, 1–8. PMID: 19265899; PMCID: PMC2620533.

- Liu, X.; Mei, S.; Salles, J.F. Inoculated microbial consortia perform better than single strains in living soil: A meta-analysis. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 190, 105011. [CrossRef]

- El-Nagdi, W.M.A.; Youssef, M. M.A.; Abd-El-Khair, H.; Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Effect of certain organic amendments and Trichoderma species on the root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita infecting pea (Pisum sativum L.) plants. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Cont. 2019, 29, 75. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.L.F.; Roberts, D.P.; Chitwood, D.J.; Carta, L.K.; Lumsden, R.D.; Mao, W. Application of Burkholderia cepacia and Trichoderma virens, alone and in combinations, against Meloidogyne incognita on bell pepper. Nematropica 2001, 31, 75–86.

- Ali, A.A.I.; Mahgoub, S.A.; Ahmed, A.F.; Mosa, W.F.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Mohamed, M.D.; Alomran, M.M.; Al-Gheffari, H.K.; El-Tarabily, K.A.; AbuQamar, S.F.; et al. Utilizing endophytic plant growth-promoting bacteria and the nematophagous fungus Purpureocillium lilacinum as biocontrol agents against the root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita) on tomato plants. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2024, 170, 417–436. [CrossRef]

- Molinari, S.; Akbarimotlagh, M.; Leonetti, P. Tomato root colonization by exogenously inoculated arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi induces resistance against root-knot nematodes in a dose-dependent manner. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8920. [CrossRef]

- Topalović, O.; Vestergård, M. Can microorganisms assist the survival and parasitism of plant-parasitic nematodes? Trends Parasitol. 2021, 37, 947–958. [CrossRef]

- Trejo-Meléndez, V.J.; Contreras-Garduño, J. Master of puppets: How microbiota drive the nematoda ecology and evolution?.” Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e71549. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M.; Duncan, L.W.; Hammam, M.M.A.; Elborai, F.; Shehata, I.E. Effect of mulching manures and use of Heterorhabditis bacteriophora on strawberry fruit yield, Temnorhynchus baal and Meloidogyne javanica under field conditions. Arab J. Plant Prot. 2024, 42, 306–317. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, X. Steering soil microbiome to enhance soil system resilience. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 45, 743–753. [CrossRef]

- Lee Díaz, A.S.; Macheda, D.; Saha, H.; Ploll, U.; Orine, D.; Biere, A. Tackling the context-dependency of microbial-induced resistance. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1293. [CrossRef]

- Hammam, M.M.A.; Abd-El-Khair, H.; El-Nagdi, W.M.A.; Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Can agricultural practices in strawberry fields induce plant–nematode interaction towards Meloidogyne-suppressive soils? Life 2022, 12, 1572. [CrossRef]

- Kepenekci, I.; Hazir, S.; Oksal, E.; Lewis, E.E. Application methods of Steinernema feltiae, Xenorhabdus bovienii and Purpureocillium lilacinum to control root-knot nematodes in greenhouse tomato systems. Crop Prot. 2018, 108, 31–38. [CrossRef]

- Hammam, M.M.A.; Shehata, I.E.; Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Biocontrol of plant-parasitic nematodes by entomopathogenic nematodes: Case studies for further optimization. Arab J. Plant Prot. 2025, 43, In Press.

- Dritsoulas, A.; El-Borai, F.E.; Shehata, I.E.; Hammam, M.M.; El-Ashry, R.M.; Mohamed, M.M.; Abd-Elgawad, M.M.; Duncan, L.W. Reclaimed desert habitats favor entomopathogenic nematode and microarthropod abundance compared to ancient farmlands in the Nile Basin. J. Nematol. 2021, 53, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Rodriguez-Saona, C.; Zalucki, M.P.; Liu, S.S.; Desneux, N. A theoretical framework to improve the adoption of green integrated pest management tactics. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 337. [CrossRef]

- Uroz, S.; Courty, P.; Oger, P. Plant symbionts are engineers of the plant-associated microbiome. Trends Pl. Sci. 2019, 24, 905–916. [CrossRef]

- Afridi, M.S.; Ali, S.; Salam, A.K.; Terra, W.C.; Hafeez, A.; Sumaira, , et al. Plant microbiome engineering: hopes or hypes. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11, 1782. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.M.M.; Ahmad, E.M.; Martínez-Medina, A.; Aly, M.A.M. Effective approaches to study the plant-root knot nematode interaction. Pl. Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 141, 332–342. [CrossRef]

- O’Halloran, D.M. CRISPR-PN2: a flexible and genome-aware platform for diverse CRISPR experiments in parasitic nematodes. BioTechniques 2001, 71, 495–498. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Nematode spatial distribution in the service of biological pest control. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Cont. 2024, 34, 3. [CrossRef]

- Dastogeer, G.; Kao-Kniffin, J.; Okazaki, S. Editorial: plant microbiome: diversity, functions, and applications. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1039212. [CrossRef]

- Malayejerdi, Z.; Pouresmaeil, O. Current applications of the microbiome engineering and its future: a brief review. J. Curr. Biomed. Rep. 2020, 1, 48–51. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Crop genomics for climate resilient agriculture. In Innovations in Climate Resilient Agriculture; Rajan, R., Ahmad, F., Pandey, K., Eds.; Springer, Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 207-225. [CrossRef]

- Tülek, A.; Kepenekçi, ˙I.; Oksal, E.; Hazir, S. Comparative effects of entomopathogenic fungi and nematodes and bacterial supernatants against rice white tip nematode. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest. Cont. 2018, 28, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Vicente, C.S.L.; Soares, M.; Faria, J.M.S.; Espada, M.; Mota, M.; Nóbrega, F.; Ramos, A.P.; Inácio, M.L. Fungal communities of the pine wilt disease complex: Studying the interaction of ophiostomatales with Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1650. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ponpandian, L.N.; Kim, H.; Jeon, J.; Hwang, B.S.; Lee, S.K.; Park, S.-C.; Bae, H. Distribution and diversity of bacterial endophytes from four Pinus species and their efficacy as biocontrol agents for devastating pine wood nematodes. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Jeon, H.W.; Mannaa, M.; Jeong, S.I.; Kim, J.; Kim, J., et al. Induction of resistance against pine wilt disease caused by Bursaphelenchus xylophilus using selected pine endophytic bacteria. Pl. Pathol. 2019, 68, 434–444. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.R.; Ives, L.; Adusei-Fosu, K.; Jordan, K.S. Ditylenchus dipsaci and Fusarium oxysporum on garlic: One plus one does not equal two. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2021, 43, 749–759. [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Bulut, A.; Shrestha, B.; Matera, C.; Grundler, F.M.W.; Schleker, A.S.S. Bacillus firmus I-1582 promotes plant growth and impairs infection and development of the cyst nematode Heterodera schachtii over two generations. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Liu, Q.; Jian, H. Bacillus cereus a potential strain infested cereal cyst nematode (Heterodera avenae). Pakistan J. Nematol. 2019, 37, 53–61. [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, T.; Antoniolli, Z.I.; Sordi, E.; Carvalho, I.R.; Bortoluzzi, E.C. Use of the Glomus etunicatum as biocontrol agent of the soybean cyst nematode. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e7310615132. [CrossRef]

- Parkunan, V.; Johnson, C.S.; Eisenback, J.D. Biological and chemical induction of resistance to the Globodera tabacum solanacearum in oriental and flue-cured tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.). J. Nematol. 2009, 41, 203–210. PMID: 22736815; PMCID: PMC3380491. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xiang, N.; Lawrence, K.S.; Kloepper, J.W.; Donald, P.A. Biological control of Rotylenchulus reniformis on soybean by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Nematropica 2018, 48, 116–125.

- Aballay, E.; Prodan, S.; Correa, P.; Allende, J. Assessment of rhizobacterial consortia to manage plant parasitic nematodes of grapevine. Crop Prot. 2020, 131, 105103. [CrossRef]

- Wong-Villarreal, A.; Méndez-Santiago, E.W.; Gómez-Rodríguez, O.; Aguilar-Marcelino, L.; García, D.C.; García-Maldonado, J.Q.; Hernández-Velázquez, V.M.; Yañez-Ocampo, G.; Espinosa-Zaragoza, S.; Ramírez-González, S.I.; et al. Nematicidal activity of the endophyte Serratia ureilytica against Nacobbus aberrans in Chili plants (Capsicum annuum L.) and identification of genes related to biological control. Plants 2021, 10, 2655. [CrossRef]

- Elsen, A.; Gervacio, D.; Swennen, R.; de Waele, D. AMF-induced biocontrol against plant- parasitic nematodes in Musa sp.: a systemic effect. Mycorrhiza 2008, 18, 251–256. [CrossRef]

- Van Overbeek, L.S.; Leiss, K.A.; Bac-Molenaar, J.A.; Duhamel, M. Plant resilience - role of chemical and microbial elicitors on metabolome and microbiome. Available online: file:///C:/Users/Mahfouzz/Desktop/WPR-1043_LR_Plantresilience_metabolomeandmicrobiome.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Plant-parasitic nematodes and their biocontrol agents: Current status and future vistas. In Management of Phytonematodes: Recent Advances and Future Challenges, 1st ed.; Ansari, R., Rizvi, R., Mahmood, I., Eds.; Springer, Singapore, 2020; pp. 171–203.

- Tiwari, M.; Pati, D.; Mohapatra, R.; Sahu, B.B.; Singh, P. Impact of microbes in plant immunity and priming induced inheritance: A sustainable approach for crop protection. Plant Stress 2022, 4, 100072. [CrossRef]

- Turgut-Kara, N.; Arikan, B.; Celik, H. Epigenetic memory and priming in plants. Genetica 2020, 148(2), 47–54. . [CrossRef]

- Richard, M.M.S.; Gratias, A.; Meyers, B.C.; Geffroy V. Molecular mechanisms that limit the costs of NLR-mediated resistance in plants. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 19, 2516-2523. [CrossRef]

- Timper, P. Conserving and enhancing biological control of nematodes. J. Nematol. 2014, 46, 75–89. [PubMed].

- Osman, H.A.I.; Ameen, H.H.; Hammam, M.M.A.; El-Sayed, G.M.; Elkelany, U.S.; Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Antagonistic potential of an Egyptian entomopathogenic nematode, compost and two native endophytic bacteria isolates against the root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita) infecting potato under field conditions. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Cont. 2022, 32, 137. [CrossRef]

| TF | Plant | Gene/Genotype/TF | Function /nematode species | Ref. |

| WRKY | Arabidopsis thaliana | AtWRKY23 | Knocking down its expression lowered Heterodera schachtii infection | [19] |

| WOX11 | Arabidopsis thaliana | LBD16 and other WOX genes | Forming lateral roots to reduce the impact of H. schachtii infections | [20] |

| GT-3a (a trihelix TF) | Arabidopsis thaliana | TOZ and RAD23C | Its stabilization by Meloidogyne incognita effectors led to suppress related plant genes and ease the formation of the giant cells. | [21] |

| SlWRKY3 | Solanum lycopersicum | SlWRKY23 | Upregulated resistance to M. javanica via shikimate pathway activation | [22] |

| SLWRKY72a/SLWRKY72b | S. lycopersicum | Mi-1 induces effector-triggered immunity | Upregulating activator of immune response against M. incognita | [23] |

| WRKY | Oryza sativa | OsWRKY34, OsWRKY36, and OsWRKY62 | Their overexpression suppresses the defense-related genes, implying that they function as a negative regulator of innate immunity against Meloidogyne graminicola | [17] |

| WRKY | Oryza sativa | OsWRKY62,OsWRKY70 and OsWRKY11 | Their early up-regulation induced oxidative stress against Hirschmanniella oryzae, that is, up-regulated 3 Peroxidase precursors and 2 glutathione S-transferases | [17] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).