Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Soil Physicochemical Properties

2.2. Sequence Data Analysis

2.3. Microbial Richness and Diversity

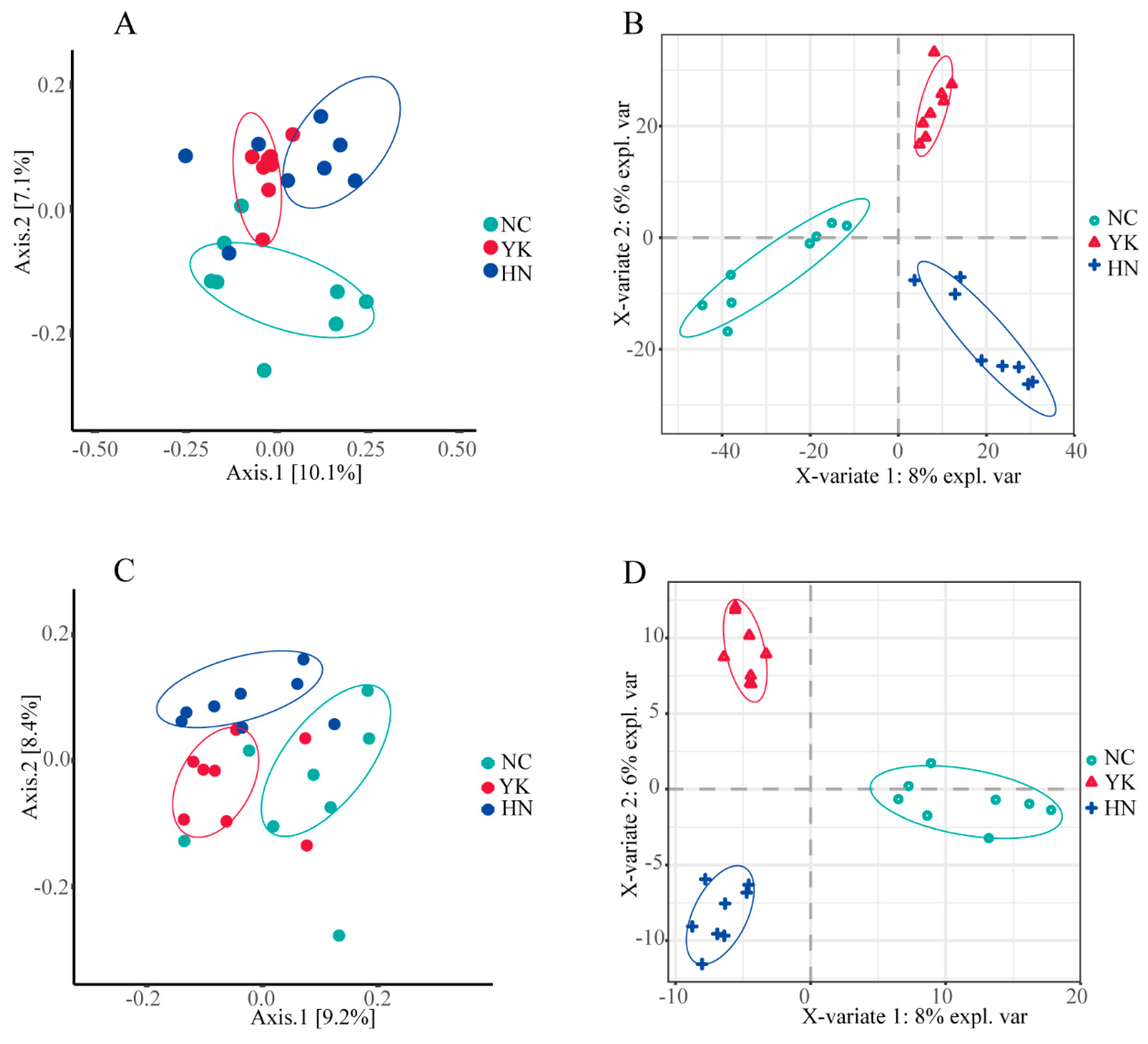

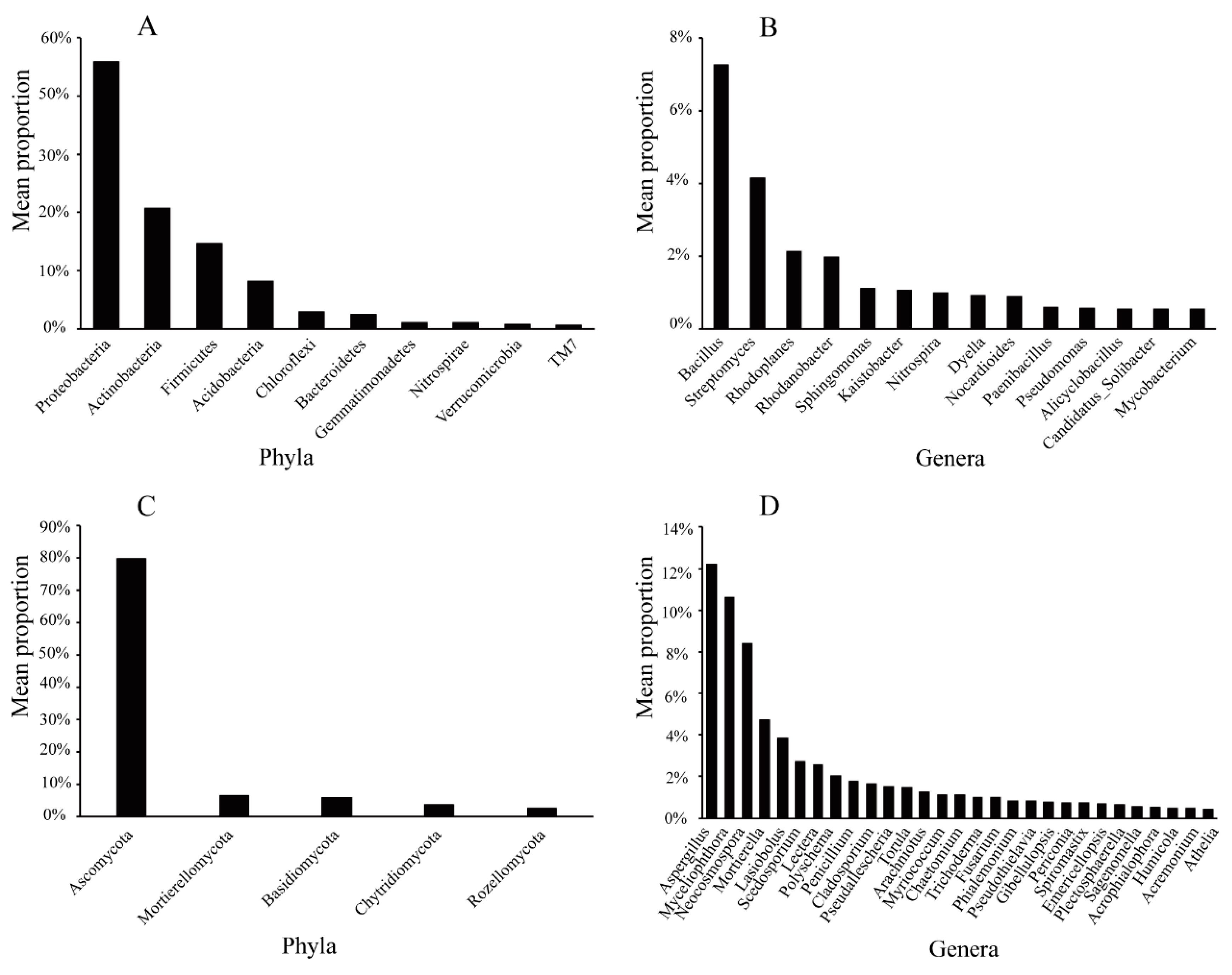

2.4. Composition of the Soil Microbial Community

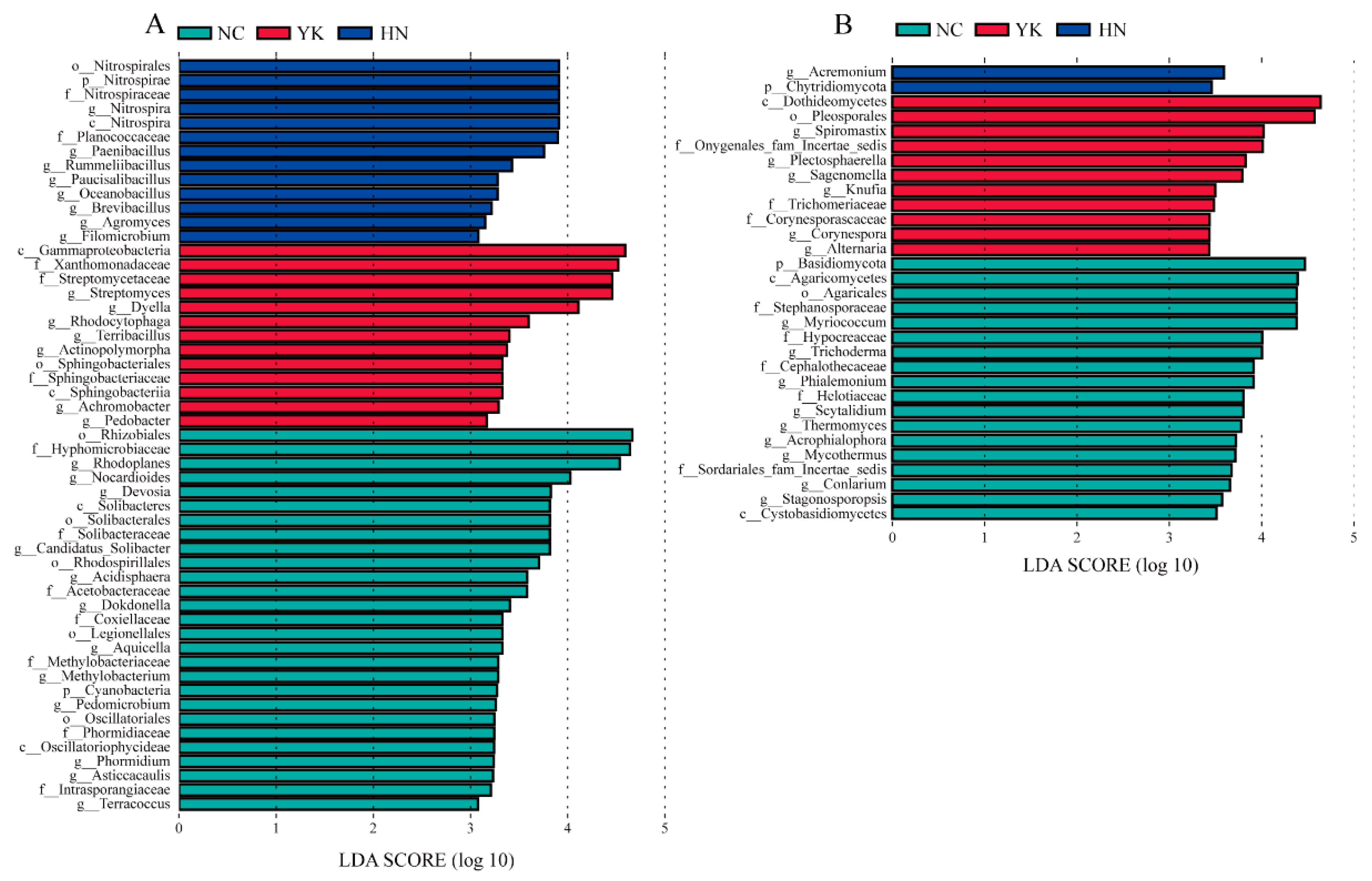

2.5. LEfSe Analysis Revealed Differences in Soil Microbial Genera

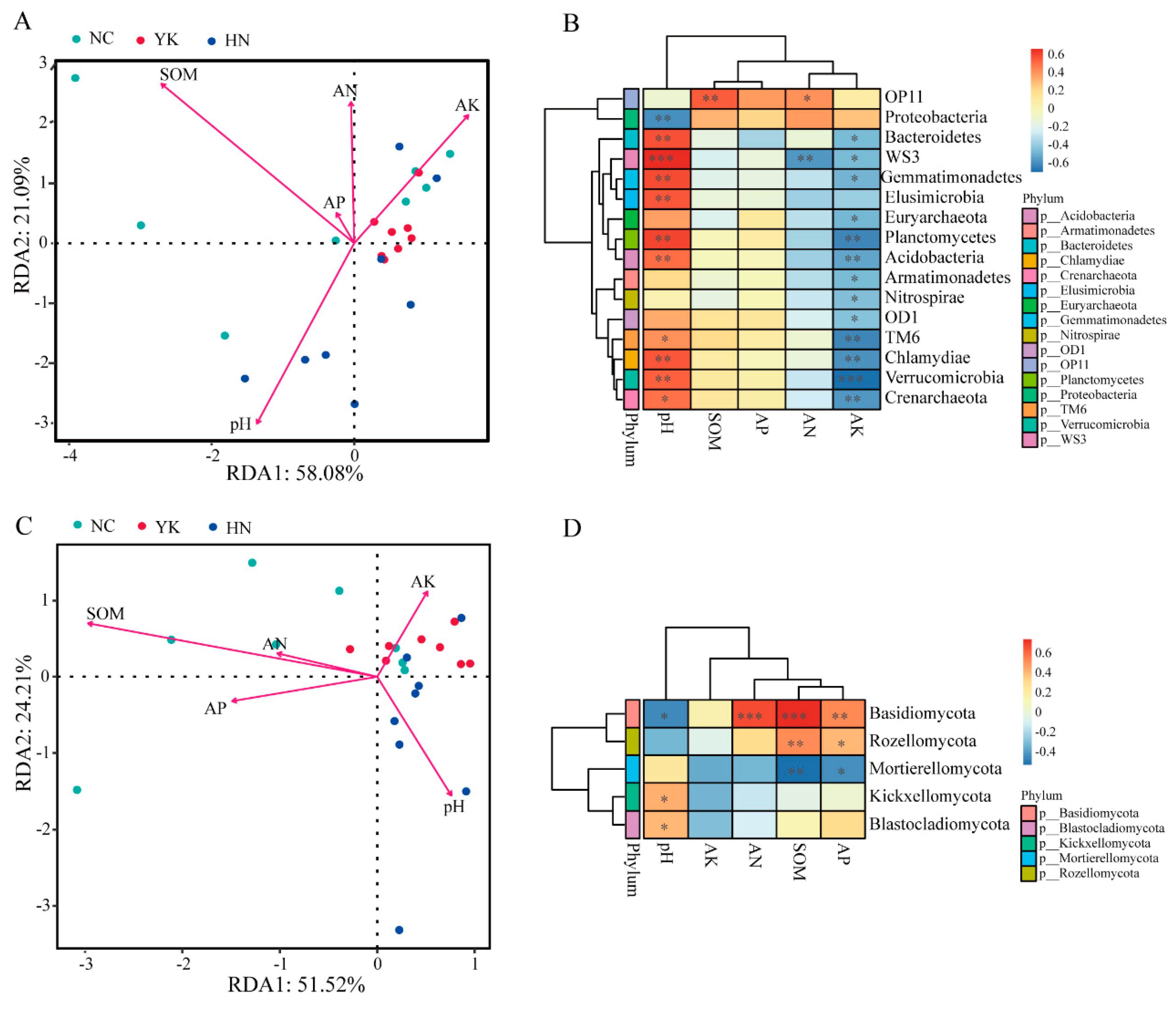

2.6. Associations Between Soil Microbial Communities and Environmental Factors

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Design and Collection of Soil Samples

4.2. Determination of Physicochemical Properties

4.3. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

4.4. Bioinformatics Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mukherjee, A.; Debnath, P.; Ghosh, S.K.; Medda, P.K. Biological control of papaya aphid (Aphis gossypii Glover) using entomopathogenic fungi. Vegetos 2020, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, S.; Coutts, B.A.; Edwards, O.R.; de Almeida, L.; Ximenes, A.; Jones, R.A.C. Papaya ringspot virus populations from east timorese and northern Australian cucurbit crops: biological and molecular properties, and absence of genetic connectivity. Plant Dis. 2017, 101, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, N.; Huang, Q.; Yin, G.; Guo, A.; Wang, X.; Xiong, Z.; Liu, Z. Complete genome of Hainan papaya ringspot virus using small RNA deep sequencing. Virus Genes 2014, 48, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirugnanavel, A.; Balamohan, T.N.; Karunakaran, G.; Manoranjitham, S.K. Effect of papaya ringspot virus on growth, yield and quality of papaya (Carica papaya) cultivars. Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2015, 85, 1069–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, S.H.; Harmiyati, T.; Adnan, A.M. Insect vector and seedborne transmission of Papaya ringspot virus. Jurnal Fitopatologi Indonesia 2022, 18, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Yan, X.; Fu, M.; Liu, D.; Awan, A.W.; Chen, P.; Rasheed, S.M.; Gao, L.; Zhang, R. Interactive effect of biological agents chitosan, lentinan and ningnanmycin on Papaya Ringspot Virus resistance in papaya (Carica papaya L.). Molecules 2022, 27, 7474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleshwaraswamy, C.; Krishnakumar, N.; Chandrashekara, K.; Vani, A. Efficacy of insecticides and oils on feeding behaviour of Aphis gossypii Glover and transmission of papaya ringspot virus (PRSV). Karnataka Journal of Agricultural Sciences 2012, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Gonsalves, D. Control of papaya ringspot virus in papaya: a case study. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1998, 36, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruanjan, P.; Kertbundit, S.; Juříček, M. Post-transcriptional gene silencing is involved in resistance of transgenic papayas to papaya ringspot virus. Biologia Plantarum 2007, 51, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Perween, S.; Ansari, A.M. Resistance to Papaya Ringspot Virus a Review. Agriculture Association of Textile Chemical and Critical Reviews Journal 2023, 11, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, R.L.; Vismans, G.; Yu, K.; Song, Y.; de Jonge, R.; Burgman, W.P.; Burmølle, M.; Herschend, J.; Bakker, P.A.H.M.; Pieterse, C.M.J. Disease-induced assemblage of a plant-beneficial bacterial consortium. The ISME journal 2018, 12, 1496–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Putten, W.H.; Bardgett, R.D.; Bever, J.D.; Bezemer, T.M.; Casper, B.B.; Fukami, T.; Kardol, P.; Klironomos, J.N.; Kulmatiski, A.; Schweitzer, J.A.; et al. Plant–soil feedbacks: the past, the present and future challenges. J. Ecol. 2013, 101, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudenhöffer, J.H.; Scheu, S.; Jousset, A. Systemic enrichment of antifungal traits in the rhizosphere microbiome after pathogen attack. J. Ecol. 2016, 104, 1566–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Casa Vargas, J.M.; Schlatter, D.C.; Hagerty, C.H.; Hulbert, S.H.; Paulitz, T.C. Rhizosphere community selection reveals bacteria associated with reduced root disease. Microbiome 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.M.; Kong, H.G.; Song, G.C.; Ryu, C.M. Disruption of Firmicutes and Actinobacteria abundance in tomato rhizosphere causes the incidence of bacterial wilt disease. The ISME Journal 2021, 15, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, F.; Liang, J.; Zhao, P.; Tsui, C.K.M.; Cai, L. Cross-kingdom synthetic microbiota supports tomato suppression of Fusarium wilt disease. Nature Communications 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, M.; Shen, Z.; Wang, B.; Jousset, A.; Geisen, S.; Ravanbakhsh, M.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; Li, R.; et al. Intercropping with Trifolium repens contributes disease suppression of banana Fusarium wilt by reshaping soil protistan communities. Agric., Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 361, 108797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loon, L.; Bakker, P.; Pieterse, C. Systemic resistance induced by rhizosphere bacteria. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1998, 36, 453–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, G.; Rybakova, D.; Grube, M.; Köberl, M. The plant microbiome explored: implications for experimental botany. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgarelli, D.; Garrido-Oter, R.; Münch, P.C.; Weiman, A.; Dröge, J.; Pan, Y.; McHardy, A.C.; Schulze-Lefert, P. Structure and function of the bacterial root microbiota in wild and domesticated barley. Cell Host & Microbe 2015, 17, 392–403. [Google Scholar]

- Bulgarelli, D.; Rott, M.; Schlaeppi, K.; Ver Loren van Themaat, E.; Ahmadinejad, N.; Assenza, F.; Rauf, P.; Huettel, B.; Reinhardt, R.; Schmelzer, E. Revealing structure and assembly cues for Arabidopsis root-inhabiting bacterial microbiota. Nature 2012, 488, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busby, P.E.; Soman, C.; Wagner, M.R.; Friesen, M.L.; Kremer, J.; Bennett, A.; Morsy, M.; Eisen, J.A.; Leach, J.E.; Dangl, J.L. Research priorities for harnessing plant microbiomes in sustainable agriculture. PLoS Biol. 2017, 15, e2001793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrillo, G.; Teixeira, P.J.P.L.; Paredes, S.H.; Law, T.F.; De Lorenzo, L.; Feltcher, M.E.; Finkel, O.M.; Breakfield, N.W.; Mieczkowski, P.; Jones, C.D.; et al. Root microbiota drive direct integration of phosphate stress and immunity. Nature 2017, 543, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, J.E.; Triplett, L.R.; Argueso, C.T.; Trivedi, P. Communication in the phytobiome. Cell 2017, 169, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, D.S.; Lebeis, S.L.; Paredes, S.H.; Yourstone, S.; Gehring, J.; Malfatti, S.; Tremblay, J.; Engelbrektson, A.; Kunin, V.; Rio, T.G.d.; et al. Defining the core Arabidopsis thaliana root microbiome. Nature 2012, 488, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.B.; Vogel, C.; Bai, Y.; Vorholt, J.A. The plant microbiota: systems-level insights and perspectives. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2016, 50, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, W.A.; Jin, Z.; Youngblut, N.; Wallace, J.G.; Sutter, J.; Zhang, W.; González-Peña, A.; Peiffer, J.; Koren, O.; Shi, Q.; et al. Large-scale replicated field study of maize rhizosphere identifies heritable microbes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 7368–7373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Cai, Z. Highly connected taxa located in the microbial network are prevalent in the rhizosphere soil of healthy plant. Biol. Fertility Soils 2019, 55, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Jin, N.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Meng, X.; Xie, Y.; Wu, Y.; Luo, S.; Lyu, J.; Yu, J. Changes in the microbial structure of the root soil and the yield of Chinese baby cabbage by chemical fertilizer reduction with bio-organic fertilizer application. Microbiology Spectrum 2022, 10, e01215–e01222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Wang, X.; Hou, R.; Lu, C.; Fan, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Q.; Friman, V.-P.; et al. Rhizosphere phage communities drive soil suppressiveness to bacterial wilt disease. Microbiome 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Lin, M.; Rensing, C.; Qin, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J.; Wu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, S.; Lin, W. Plant-mediated rhizospheric interactions in intraspecific intercropping alleviate the replanting disease of Radix pseudostellariae. Plant Soil 2020, 454, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Jing, F.; Sun, W.; Liu, J.; Jiang, G. Soil microbial communities changed with a continuously monocropped processing tomato system. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B — Soil & Plant Science 2018, 68, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, A.L.d.R.; Bhering, A.d.S.; do Carmo, M.G.; Andreote, F.D.; Dias, A.C.; Coelho, I.d.S. Bacterial composition in brassica-cultivated soils with low and high severity of clubroot. J. Phytopathol. 2020, 168, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daims, H.; Lebedeva, E.V.; Pjevac, P.; Han, P.; Herbold, C.; Albertsen, M.; Jehmlich, N.; Palatinszky, M.; Vierheilig, J.; Bulaev, A.; et al. Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria. Nature 2015, 528, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; He, Z.-Y.; Hu, H.-W.; He, J.-Z. Niche specialization of comammox Nitrospira in terrestrial ecosystems: oligotrophic or copiotrophic? Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kessel, M.A.; Speth, D.R.; Albertsen, M.; Nielsen, P.H.; Op den Camp, H.J.; Kartal, B.; Jetten, M.S.; Lücker, S. Complete nitrification by a single microorganism. Nature 2015, 528, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Han, C.; Zhu, G. Comammox bacterial abundance, activity, and contribution in agricultural rhizosphere soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 727, 138563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Evans, S.E.; Friesen, M.L.; Tiemann, L.K. Effect of nitrogen fertilization on the abundance of nitrogen cycling genes in agricultural soils: a meta-analysis of field studies. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 127, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Peng, Y.; Li, B.; Guo, J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, S. Biological removal of nitrogen from wastewater. Reviews of environmental contamination and toxicology 2008, 159–195. [Google Scholar]

- De Santis Sica, P.; Shirata, E.S.; Rios, F.A.; Brandao Filho, J.U.T.; Schwan Estrada, K.R.F.; Oliveira, R.S.d. Impact of N-fixing bacterium 'Nitrospirillum amazonense'on quality and quantitative parameters of sugarcane under field condition. Australian Journal of Crop Science 2020, 14, 1870–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.J.; Park, T.S.; Kim, K.H.; Jeon, C.O.; Lee, H.I.; Chang, W.S.; Aslam, Z.; Chung, Y.R. Nitrospirillum irinus sp. nov., a diazotrophic bacterium isolated from the rhizosphere soil of Iris and emended description of the genus Nitrospirillum. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2015, 108, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Y.; Wang, T.; Huang, Q.; Guo, H.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Q.; Shen, Q.; Ling, N. Core species impact plant health by enhancing soil microbial cooperation and network complexity during community coalescence. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 188, 109231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ash, C.; Priest, F.G.; Collins, M.D. Molecular identification of rRNA group 3 bacilli (Ash, Farrow, Wallbanks and Collins) using a PCR probe test: proposal for the creation of a new genus Paenibacillus. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 1993, 64, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grady, E.N.; MacDonald, J.; Liu, L.; Richman, A.; Yuan, Z.C. Current knowledge and perspectives of Paenibacillus: a review. Microbial Cell Factories 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phi, Q.-T.; Park, Y.-M.; Seul, K.-J.; Ryu, C.-M.; Park, S.-H.; Kim, J.-G.; Ghim, S.-Y. Assessment of root-associated Paenibacillus polymyxa groups on growth promotion and induced systemic resistance in pepper. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2010, 20, 1605–1613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Han, H.; Hou, J.; Bao, F.; Tan, H.; Lou, X.; Wang, G.; Zhao, F. Control of maize sheath blight and elicit induced systemic resistance using Paenibacillus polymyxa strain SF05. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Q.; Zhang, J.; Fu, Q.; Hao, G.; Liang, C.; Duan, F.; Zhao, H.; Song, W. Biocontrol efficacy and induced resistance of Paenibacillus polymyxa J2-4 against Meloidogyne incognita infection in cucumber. Phytopathology® 2024, 114, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkhalek, A.; Al-Askar, A.A.; Elbeaino, T.; Moawad, H.; El-Gendi, H. Protective and curative activities of Paenibacillus polymyxa against Zucchini yellow mosaic virus infestation in squash plants. Biology 2022, 11, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, A.; Prasad, P.; Das, S.N.; Kalam, S.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Reddy, M.S.; El Enshasy, H. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) as green bioinoculants: recent developments, constraints, and prospects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loni, P.P.; Patil, J.U.; Phugare, S.S.; Bajekal, S.S. Purification and characterization of alkaline chitinase from Paenibacillus pasadenensis NCIM 5434. J. Basic Microbiol. 2014, 54, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, K.; Rajabpour, A.; Parizipour, G.; Yarahmadi, F. Insecticidal bioactive compounds derived from Cladosporium cladosporioides (Fresen.) GA de Vries and Acremonium zeylanicum (Petch) W. Gams & HC Evans. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection 2023, 130, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinson, N.P.; Mann, R.C.; Giri, K.; Malipatil, M.; Kaur, J.; Spangenberg, G.; Valenzuela, I. Novel bioassay to assess antibiotic effects of fungal endophytes on aphids. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0228813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, R.; van der Sluijs, M.; Biere, A.; Harvey, J.A.; Bezemer, T.M. Plant community composition but not plant traits determine the outcome of soil legacy effects on plants and insects. J. Ecol. 2018, 106, 1217–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kos, M.; Tuijl, M.A.B.; de Roo, J.; Mulder, P.P.J.; Bezemer, T.M. Species-specific plant–soil feedback effects on above-ground plant–insect interactions. J. Ecol. 2015, 103, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, R.; Biere, A.; Bezemer, T.M. Plant traits shape soil legacy effects on individual plant–insect interactions. Oikos 2020, 129, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huberty, M.; Steinauer, K.; Heinen, R.; Jongen, R.; Hannula, S.E.; Choi, Y.H.; Bezemer, T.M. Temporal changes in plant–soil feedback effects on microbial networks, leaf metabolomics and plant–insect interactions. J. Ecol. 2022, 110, 1328–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Jin, L.; Jin, N.; Xie, J.; Xiao, X.; Hu, L.; Tang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Niu, L.; Yu, J. Effects of different vegetable rotations on fungal community structure in continuous tomato cropping matrix in greenhouse. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Wang, C. Background nutrients and bacterial community evolution determine 13C-17β-estradiol mineralization in lake sediment microcosms. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2304–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zu, C.; Wang, C.; Yang, J.; Yu, H.; Wu, H. Different responses of rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soil microbial communities to consecutive Piper nigrum L. monoculture. Scientific Reports 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Kaehler, B.D.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.; Bolyen, E.; Knight, R.; Huttley, G.A.; Gregory Caporaso, J. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome 2018, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Taxonomic level | 16S | ITS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of unique features |

Percent of classified reads |

Number of unique features |

Percent of classified reads |

|

| Domain | 2 | 100.00 | 5 | 100 |

| Phylum | 41 | 99.84 | 11 | 93.56 |

| Class | 121 | 99.61 | 31 | 88.47 |

| Order | 192 | 95.43 | 75 | 88.20 |

| Family | 241 | 81.02 | 163 | 86.39 |

| Genus | 411 | 36.14 | 314 | 74.05 |

| Species | 238 | 11.87 | 424 | 43.95 |

| Soil sample | Phylum | Class | Order | Family | Genus | Species | OTU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | NC (Diseased plant) | 11 | 26 | 66 | 135 | 235 | 273 | 1205 |

| YK (Diseased plant) | 10 | 27 | 61 | 130 | 227 | 266 | 1034 | |

| HN (Healthy plant) | 11 | 26 | 62 | 124 | 207 | 260 | 1105 | |

| Bacteria | NC (Diseased plant) | 40 | 109 | 173 | 216 | 306 | 160 | 7193 |

| YK (Diseased plant) | 35 | 103 | 161 | 213 | 309 | 154 | 6733 | |

| HN (Healthy plant) | 39 | 111 | 171 | 217 | 317 | 175 | 8009 |

| Taxon group | Soil Sample | OTUs | Chao 1 index | Shannon diversity | Simpson index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | NC | 1652.88 ± 439.71a | 1661.62 ± 441.88 a | 8.80 ± 1.13 a | 0.99 ± 0.01 a |

| YK | 1524.5 ± 57.47 a | 1530.87 ± 56.96 a | 8.53 ± 0.31 a | 0.99 ± 0.05 a | |

| HN | 1768.5 ± 334.14 a | 1781.21 ± 336.21 a | 9.00 ± 0.81 a | 0.99 ± 0.01 a | |

| Fungi | NC | 276.63 ± 41.64 a | 276.63 ±41.64 a | 5.64 ± 0.64 a | 0.95 ± 0.34 a |

| YK | 262.38 ± 35.64 a | 262.38 ±35.64 a | 5.44 ± 0.44 a | 0.94 ± 0.04 a | |

| HN | 273.38 ±36.35 a | 273.38 ± 36.35 a | 5.35 ± 0.33 a | 0.94 ± 0.24 a |

| Comparison groups | Bray-Curtis anosim-pairwise | Unweighted UniFrac anosim-pairwise | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P | R | P | ||

|

16S |

NC-YK | 0.40 | 0.003 | 0.31 | 0.004 |

| NC-HN | 0.23 | 0.025 | 0.17 | 0.047 | |

| HN-YK | 0.22 | 0.013 | 0.17 | 0.025 | |

|

ITS |

NC-YK | 0.28 | 0.004 | 0.15 | 0.021 |

| NC-HN | 0.19 | 0.013 | 0.31 | 0.002 | |

| HN-YK | 0.32 | 0.003 | 0.20 | 0.007 | |

| Taxonomic level | Taxon | NC | YK | HN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Nitrospirae | 0.10 ± 0.17** | 0.92 ± 0.28** | 1.55 ± 0.49 |

| Gemmatimonadetes | 0.97 ± 0.45* | 1.07 ± 0.31 | 1.48 ± 0.49 | |

| Chloroflexi | 3.00 ± 0.73* | 2.49 ± 0.54 | 3.55 ± 0.94 | |

| TM7 | 0.52 ± 0.45 | 1.07 ± 0.41** | 0.44 ± 0.34 | |

| Genus | Nitrospira | 0.83 ± 0.13** | 0.79 ± 0.27** | 1.35 ± 0.41 |

| Paenibacillus | 0.35 ± 0.12** | 0.58 ± 0.19 | 0.83 ± 0.38 | |

| Rhodanobacter | 1.44 ± 0.89 | 3.17 ± 2.38* | 1.34 ± 0.83 | |

| Sphingomonas | 0.86 ± 0.26 | 1.70 ± 1.28* | 0.78 ± 0.46 | |

| Dyella | 0.42 ± 0.11 | 1.68 ± 1.04** | 0.65 ± 0.52 |

| Taxonomic level | Taxon | NC | YK | HN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Glomeromycota | 0.01 ± 0.19* | 0.01 ± 0.012* | 0.47 ± 0.71 |

| Mortierellomycota | 2.63 ± 1.60* | 6.45 ± 5.89 | 8.58 ± 5.77 | |

| Basidiomycota | 2.03 ± 2.29* | 3.29 ± 2.02 | 2.75 ± 3.01 | |

| Genus | Neocosmospora | 7.78 ± 4.82 | 6.13 ± 2.73* | 11.36 ± 4.18 |

| Trichoderma | 1.82 ± 1.34* | 0.62 ± 0.59 | 0.61 ± 0.47 | |

| Polyschema | 0.26 ± 0.54 | 4.85 ± 5.60* | 1.03 ± 1.84 | |

| Acremonium | 0.21 ± 0.18** | 0.48 ± 0.43 | 0.71 ± 0.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).