1. Introduction

Biomass is a renewable energy resource and is widely available throughout the world. It is a net carbon-zero fuel source[

1,

2]. A large number of the world’s population, approximately 3.5 billion people, are dependent on biomass fuels for their day-to-day activities [

3,

4]. Especially in developing nations, a direct burning of biomass is the main source of fuel for cooking and space heating [

5,

6]. As part of the developing world, Ethiopia’s energy supply is mainly biomass-dependent, which accounts for 92-95% of the total energy requirement [

7,

8].

As reported by [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] using traditional biomass combustion, such as the three-stone fires, incurs a negative impact on health, environment, and socioeconomic development. Household air pollution from the combustion of solid fuels is one of the leading causes of child deaths [

14]. As of the 2019 WHO report, due to partial/poor thermal combustion of solid fuels, 3.8 million deaths per year occurred as a result of harmful pollutant exposure [

15].

The findings of [

16,

17,

18] assert that traditional biomass stoves have very poor thermal efficiency because of large amounts of heat losses. Due to this inefficiency, a large amount of firewood is consumed to perform specific tasks [

2,

19]. Forests are extensively degraded for firewood, which leads to environmental problems such as soil erosion and climate change [

19,

20,

21]. As a result, interventions are necessary to minimize energy losses and alleviate the negative environmental impacts of traditional biomass energy conversion methods. The adoption of improved biomass cook stove technology is being proposed by national and international entities to counter the limitations of traditional cooking stoves.

Research has been performed on thermal efficiency improvement and emission reduction of traditional biomass cooking stoves. The performance of improved cook stoves mainly depends on the design of stoves, the type of insulation materials, the body construction material, and fuel type [

22]. For instance, in the work of J. Okino et al. [

22] effect of insulation material on the thermal performance of ICSs was evaluated. The inclusion of insulation material helped to elevate the combustion chamber temperature by reducing heat loss, which in turn increased the overall thermal efficiency. Similar findings were also published by [

23,

24,

25].

Other studies were conducted by [

26,

27,

28,

29]

to evaluate how stove design and construction materials impact the efficiency of ICSs. Through the work of Chica et al. [

18] performance of existing plancha-type stoves was improved by modifying the structure of the body and using better materials. The thermal efficiency of their design exceeds the baseline three-stone cookstoves by 73%. On the other hand, Pasha. et al. [

28] performed pioneering work to design a modified Tchar stove. They developed an improved Tchar stove by merging the traditional Tchar gasifier with a charcoal stove into a single structure. The finding reveals that the modified Tchar stove exhibited better thermal performance with excellent structure compared to the traditional Tchar stove. Haile [

30] developed and tested a top-lit updraft natural draft gasifier stove. He optimized the space between the internal and external cylinders to preheat the secondary air before entering the combustion chamber. With this modification, an efficiency of 26.25%-32.3% for different feedstock fuels was achieved. Other scholars also demonstrate the potential of ICSs for fuel savings and emission reduction. Wassie et al [

31] analyzed the influence of ICSs on fuel consumption and pollutant emission. The finding was positive; utilization of ICSs reduced fuel consumption on average by 1.72-2.08 tons per household per year and 2.82-3.43 tCO

2e reduction per stove per year. Similarly, Dresen et al. [

32] demonstrated the influence of the famous ‘mirt’ ICSs on fuelwood saving and carbon emission reduction in Ethiopia. The outcome of the study revealed that using ‘mirt’ saved 40% fuelwood compared to the traditional biomass cookstove.

In Ethiopia, improved cooking stove technologies are being disseminated within the country by various factors. Despite distributing ICSs to different households, reliable thermal performance data is not available for cookstove users and distributors to select stoves. Additionally, research on the perceptions and barriers to the adoption of ICSs in Wereta, Ethiopia, revealed that the main obstacles to the adoption of ICS were low awareness, high prices, and age-related variables. In this study, the thermal performance of five charcoal cookstoves dispatched in the Wereta district was assessed and compared using the WBT. This study aims to play a vital role for government policymakers and ICSs consumers by enhancing their awareness of the performance of ICSs, which enables them to select the best ICSs based on real data.

2. Materials and Methods

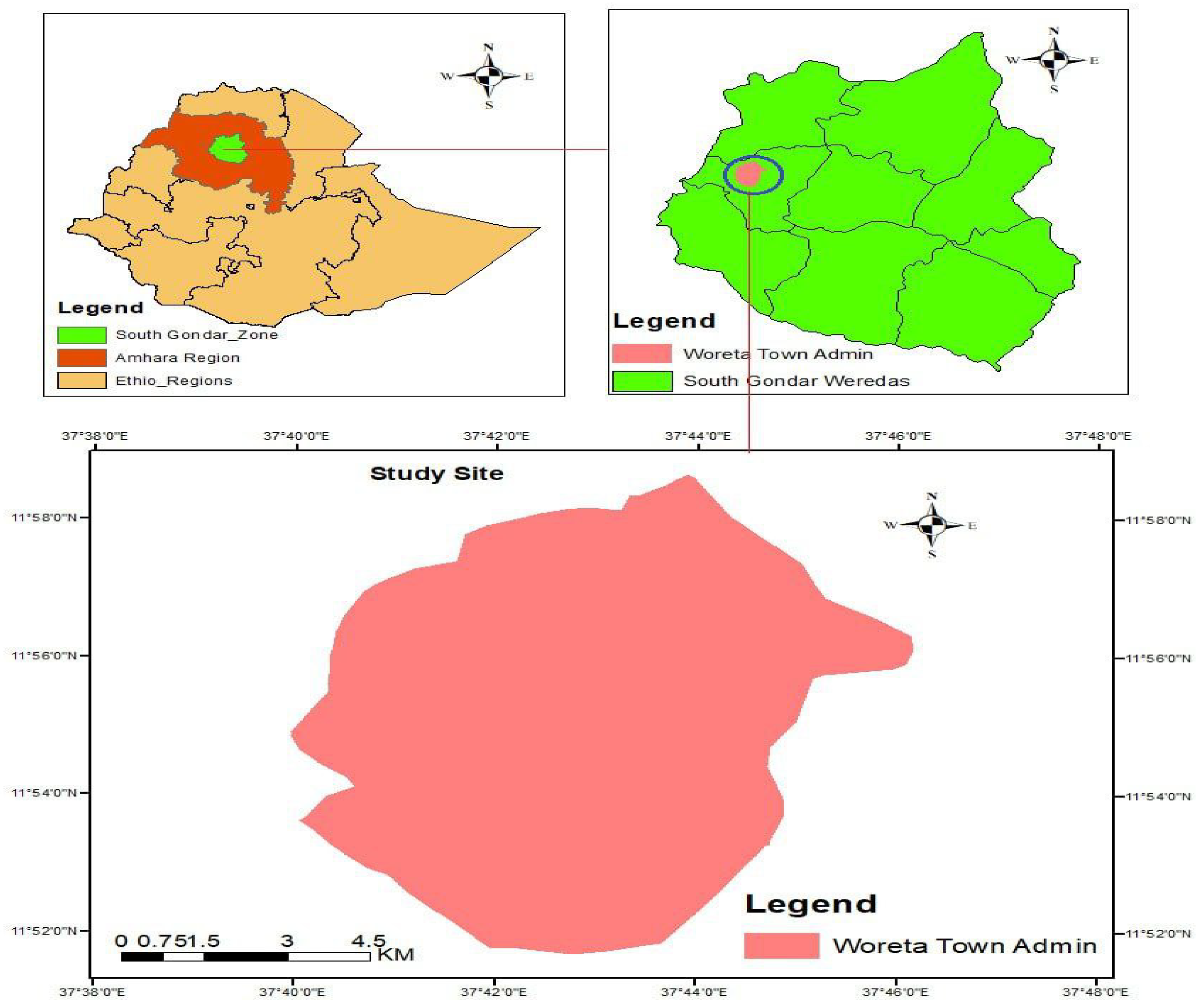

2.1. Study Area

The assessment was conducted in Fogera District, Wereta town. This is located in the Amhara Regional State of Ethiopia. It is part of the south Gondar zone, adjacent to Lake Tana. Located at a latitude of 11º57′N and a longitude of 37º35′E with an elevation of 1828 meters above sea level. The district has a temperature range of 6.3 °C to 33 °C. This area receives 1259 mm of annual rainfall on average. The province’s population is estimated to be 228,449, who live in a 117,405-hectare area [

33]. The primary energy source used by the homes in this area is biomass, which is charcoal.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area [

5].

Figure 1.

Map of the study area [

5].

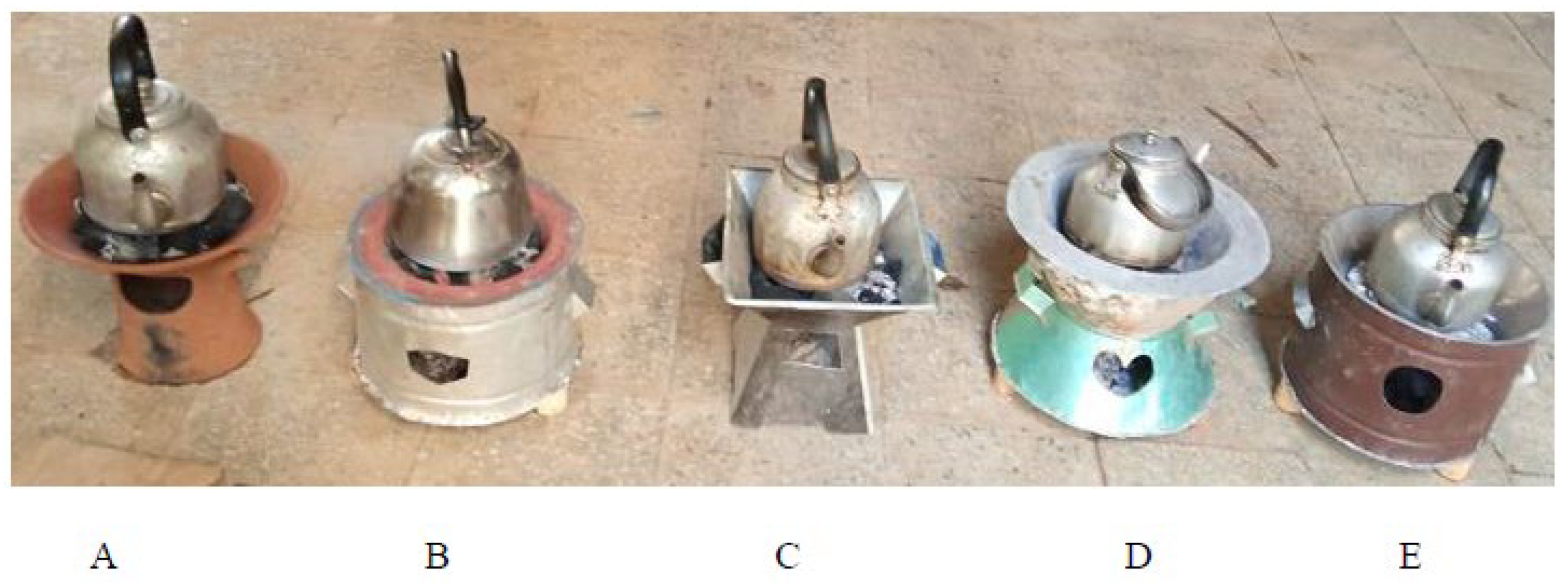

2.2. Selection of Five Improved Charcoal Cooking Stoves

Our research team conducted a study previously to examine the perception and barriers to improved charcoal cookstoves adoption in Wereta, Ethiopia. Accordingly, the most distributed charcoal cooking stoves in the community were traditional clay stoves (type 1), cylindrical stoves insulated with clay (type 2), rocket stoves without insulation (type 3), rocket stoves insulated with bricks (type 4), and cylindrical stoves without insulation (type 5), as presented in

Table 1 below [

5].

2.3. Fuel Used

The biomass fuel used in the study was purchased from the fuel wood market located in the city of Wereta. The most commonly available and used fuel was chosen, which was found to be eucalyptus charcoal. The fuel eucalyptus charcoal is cut into a convenient size, 6-10 cm in diameter and 20-30 cm long, and is taken, and the charcoal is dried by the sun, to avoid the effect of moisture content on performance. Before starting the test, the weighed quantity of fuel charcoal was stacked in small lots of 0.5 kg for each five cooking stoves. The fuel charcoal used has a higher calorific value (HHV) and lower calorific value (LHV) of 31,000 KJ/kg and 29,800 KJ/kg, respectively, and a fixed carbon content of 0.95% by mass.

2.3. Construction Details of the Five Selected ICSs

To avoid the effect of height (cm), the diameter of the combustion chamber (cm), the diameter of the air inlet (cm), and the weight (kg) of each stove on performance analysis, almost similar height, weight, and diameter were selected, except for the following construction details.

Type 1 charcoal cooking stove: All the body of the type 1 stove is made from clay, including the firebox and air-fuel inlet. This type of cooking stove is the first modified stove after the traditional three-stone stove in Ethiopia, and maintenance is difficult; once broken, it is mandatory to buy another stove from the market. No chimney is provided for smoke removal, and no air-fuel controller is installed, as shown in

Figure 2.

Type 2 charcoal cooking stoves: The body of the type 2 stove is made from steel insulated with clay, which reduces heat loss to the surroundings. This type of cooking stove is the first modified stove after the clay stove; maintenance is simpler than the clay stove and more difficult than the remaining three cooking stoves. It is cylindrical and has no chimney for smoke removal. The stove also consists of an ash collection box below the grate. The stove is provided with two handles for carrying it safely from one place to another.

Type 3 charcoal cooking stoves: All of its body is made from steel pipe from the outside and inside, and it has no insulation. The air-inlet shape varies from one local manufacturer to the other. This type of cooking stove is currently available in the market in different styles. Has no secondary air inlet and chimney for smoke removal.

Type 4 charcoal cooking stoves: This type of stove is made from a steel pipe, and it has brick insulation. Chimney and air fuel controllers are not provided. This type of ICS constitutes a sufficient secondary air inlet. It has a perforated hemispherical combustion chamber, and the pot is directly set on the charcoal.

Type 5 charcoal cooking stoves: It is made from a steel pipe without insulation. Compared to other stoves, maintenance is simple. There is no air inlet controller, as well as a chimney for smoke removal. Such of stove is installed with a secondary air inlet to provide sufficient air for combustion. The combustion chamber is perforated to let air in and to remove ashes. Below the chamber ash collector is available.

2.4. Performance Evaluation of ICSs

Different methods are applicable to compare the typical performance of various models of cookstoves. In this study water boiling test was employed to get the overall thermal efficiency of charcoal-burning stoves. This method was also used by various researchers [

1,

4,

34,

35,

36]. The experiments were carried out in triplicate, and the average was reported. According to the WBT protocol, the vessel was filled with water to occupy two-thirds of the volume [

28]. The initial temperature of water in all pots was noted using a laboratory thermometer. The temperature rise of water was noted at regular intervals (5min). The fire was extinguished in the ground immediately at the end of the test duration, and the quantity of residual water in all the pots was measured. The power rate, average fuel consumption, thermal efficiency, and time taken to boil water were determined for each charcoal cooking stove.

2.4.1. Thermal Properties Analysis of Improved Cooking Stoves

The temperature-corrected time to boil

The temperature-corrected time to boil

is a crucial variable that modifies the boiling time taken to reach 75°C to account for variations in starting temperatures and local boiling points [

28]. It is determined by Equation (1):

Where: is the final time,

is the initial time,

is the initial temperature of water (°C), and

is the local boiling point of water (°C).

Thermal efficiency

The thermal efficiency (η) of a biomass cook stove measures how much of the heat energy is transferred from the biomass to the cooking pot. It is the ratio of the energy absorbed by the water to the total energy of the fuel generated by combustion [

19]. Thermal efficiency is expressed by equation (2).

Where: is Mass of water (kg),

heat capacity (kJ/kg/°C),

and

are the initial and boiling temperature of the water (°C),

is the Mass of evaporated water (kg),

is Latent heat of water (kJ/kg),

and

are mass in (kg) and heating value (kJ/kg) of fuel, respectively.

Firepower Determination: is a ratio of the equivalent dry fuel energy consumed by the stove per unit of time [

37]. Mathematically, it is expressed as in Equation (3).

Burning Rate (BR): is the measure of fuel consumption to bring water to a boil. It is the ratio of fuel consumed to the duration of the test as expressed in Equation (4).

Where: Refers to mass of the consumed fuel during the test

Specific fuel consumption (SC, g/L): is the ratio of energy consumed to the amount of boiled water remaining in the pot [

18], then FCR can be estimated using Equation (5) below.

Where: the mass of liquid water present in the pots after the test and

refers to the equivalent dry fuel consumed

3. Results and Discussions

In this study, the performance of the stoves was measured by thermal efficiency (%), specific fuel consumption (g/L), fire power (kW), temperature corrected time to boil and burning rate. The results of these variables for the different phases are discussed below.

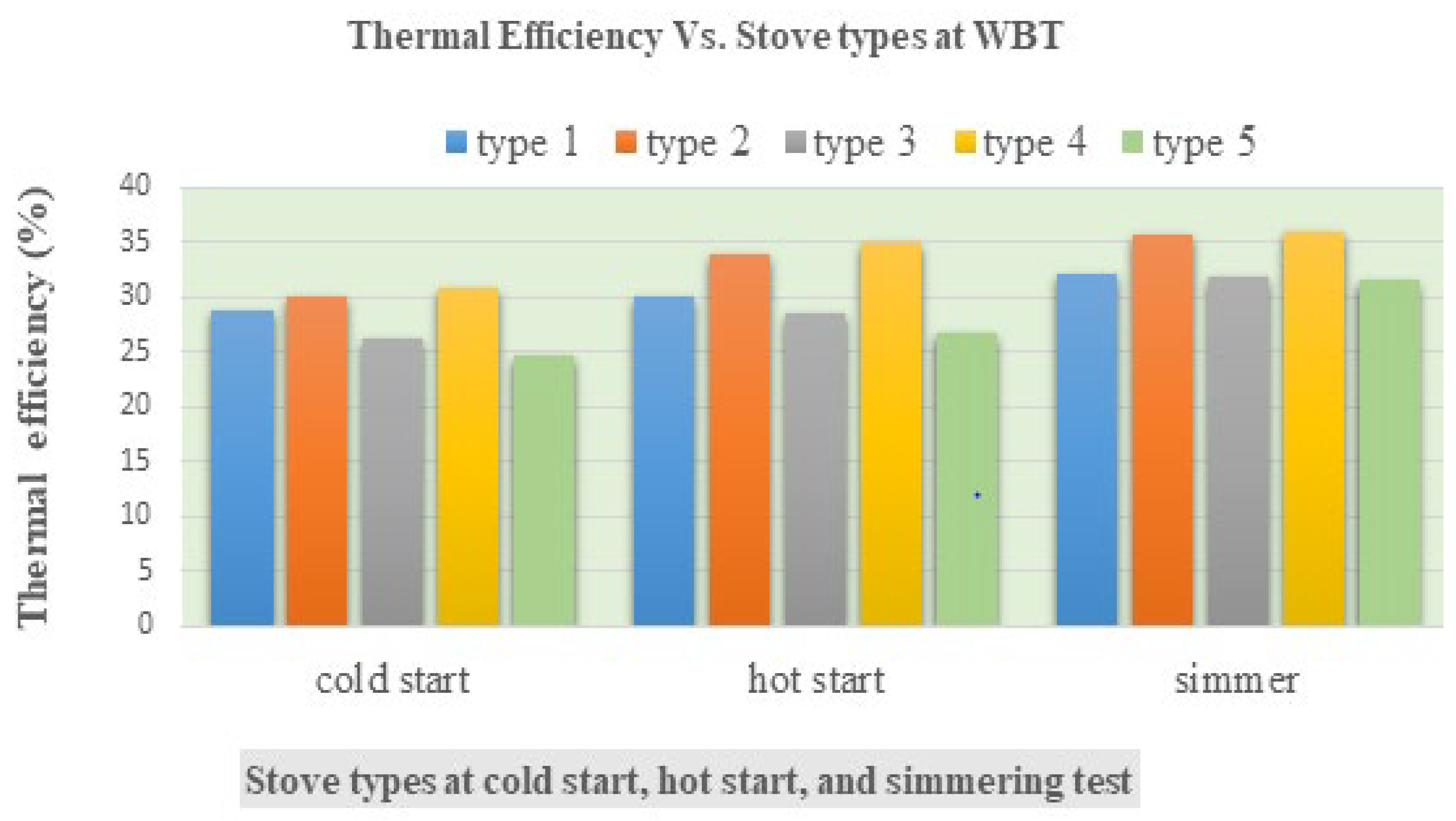

3.1. Thermal Efficiency

The thermal efficiencies of all five selected stoves are presented in

Figure 3.

The efficiency of the stove is influenced by various factors, including construction material, design principles, and geometries of the stove [

22]. The thermal efficiency of types 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 at the hot start was 30%, 34 %, 28.5%, 35%, and 26.7% respectively. From the result, type 5 showed lower thermal efficiency, whereas type 4 exhibited higher thermal efficiency. The superior thermal efficiency of type 4 might be attributed to the presence of thermal insulation, which limits undesirable heat loss to the surroundings and raises the internal temperature. Similar observation was reported by [

37] compared to the three-stone fire, the improved cookstove had better thermal efficiency due to the availability of insulation material. Additionally, the rocket shape of such kind of stoves may improve fuel burn rate by lifting hot gases upward and thereby enhancing natural draft. Whereas, the reason for low thermal efficiency for type 5 (cylindrical charcoal cook stoves) is likely to be heat losses to the surroundings due to the absence of insulation in the stove. A recent development on ICSs confirmed that the efficiency of traditional cookstoves could be enhanced with small improvements [

2].

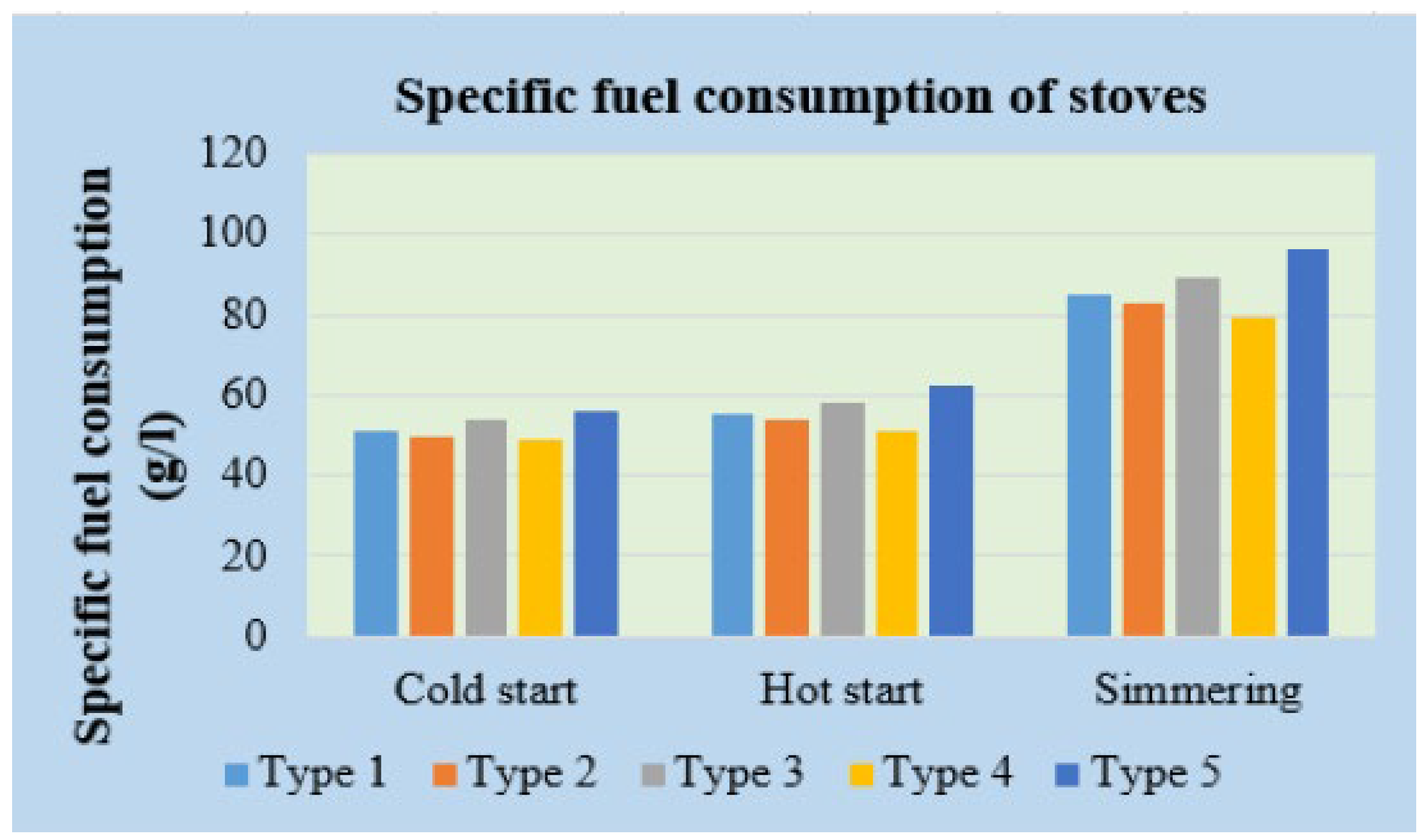

3.2. Specific Fuel Consumption

The specific fuel consumption of all the selected five stoves in the study area is presented in

Figure 4.

The fuel consumption (g/min) is the rate of biomass burned to boil a specific amount of water [

38].

Figure 4 illustrates the average specific fuel consumption of the five stoves at the cold, hot and simmering phases. The specific fuel consumption of types 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 at the hot start was 55, 53.6, 58, 51.2, and 62.5 g/L, respectively. Type 4 resembled the lowest average specific fuel consumption of 51.2 g/L at the hot start. As confirmed by the thermal efficiency test, this stove type consumes less amount of energy to perform similar tasks. As this stove type showed higher thermal efficiency, the amount of fuel consumed was lower. This might be due to the thermal insulation and the optimized design of the stove. Whereas, the highest specific fuel was consumed by Type 5 with 62.5 g/L. Type 1 has slower heat transfer, which means clay retains heat for longer periods, maintaining a steady cooking temperature with less fuel, unlike steel pipes heat up and cool down quickly. Though type 1 stoves are more traditional than others, it is better in specific fuel consumption than types 3 and 5. From the result, it is important to notice the influence of selecting appropriate materials and carefully considering the mechanical design of cook stoves to improve thermal efficiency and the overall performance.

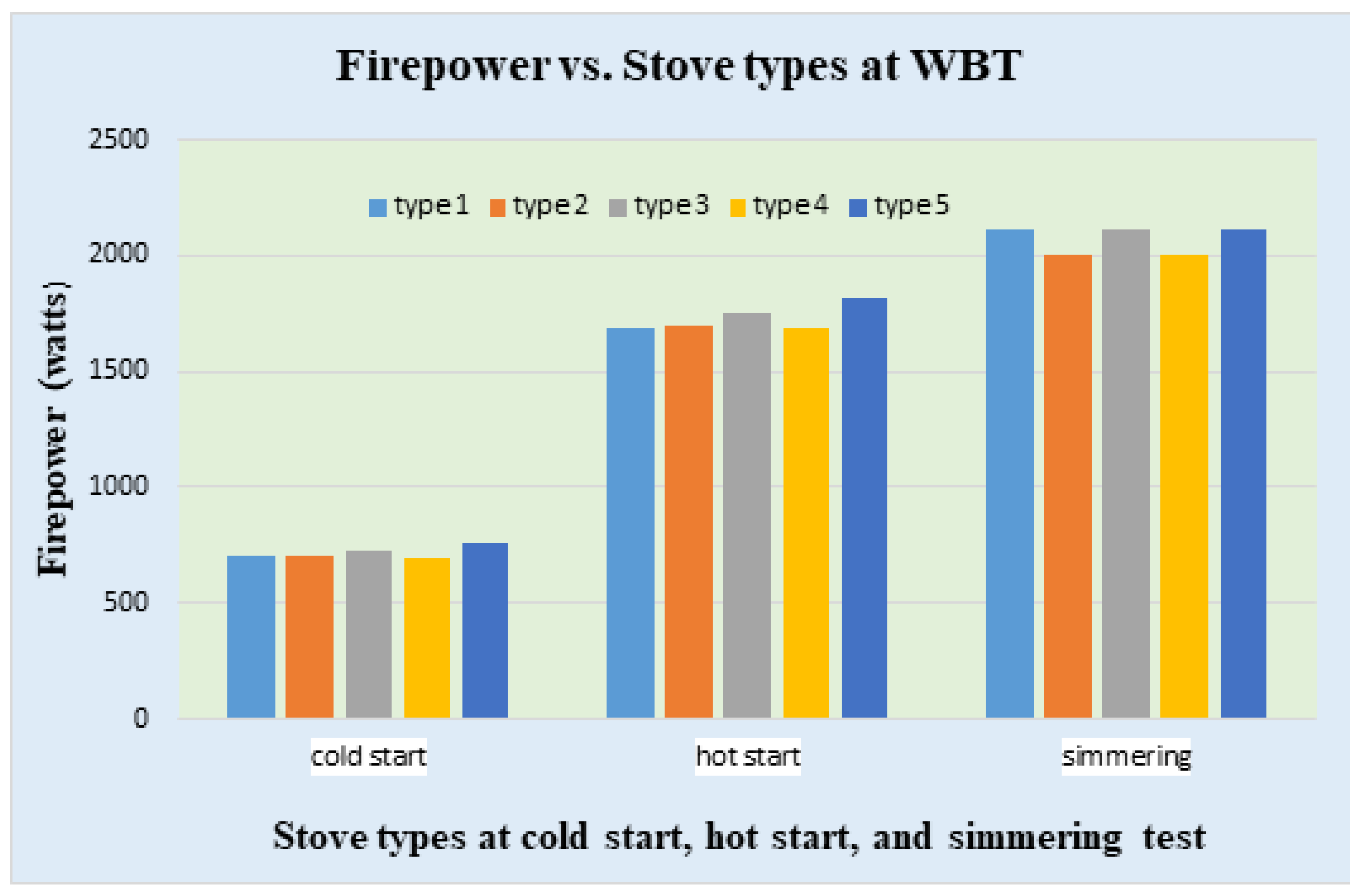

3.3. Firepower

The firepower of all five selected stoves in the study area is presented in

Figure 5.

The average firepower (W) consumed by the five stoves to boil water at cold start, hot start, and simmering phases is displayed in

Figure 5. The result showed that stove types 1, 3, and 5 generated more compared to types 2 and 4. From the result, it was noted that stoves with higher thermal efficiencies (types 2 and 4) had lower firepower. This implies that less energy is consumed by type 2 and type 4 stoves to boil the same amount of water. Similar findings were also observed by [

2,

7].

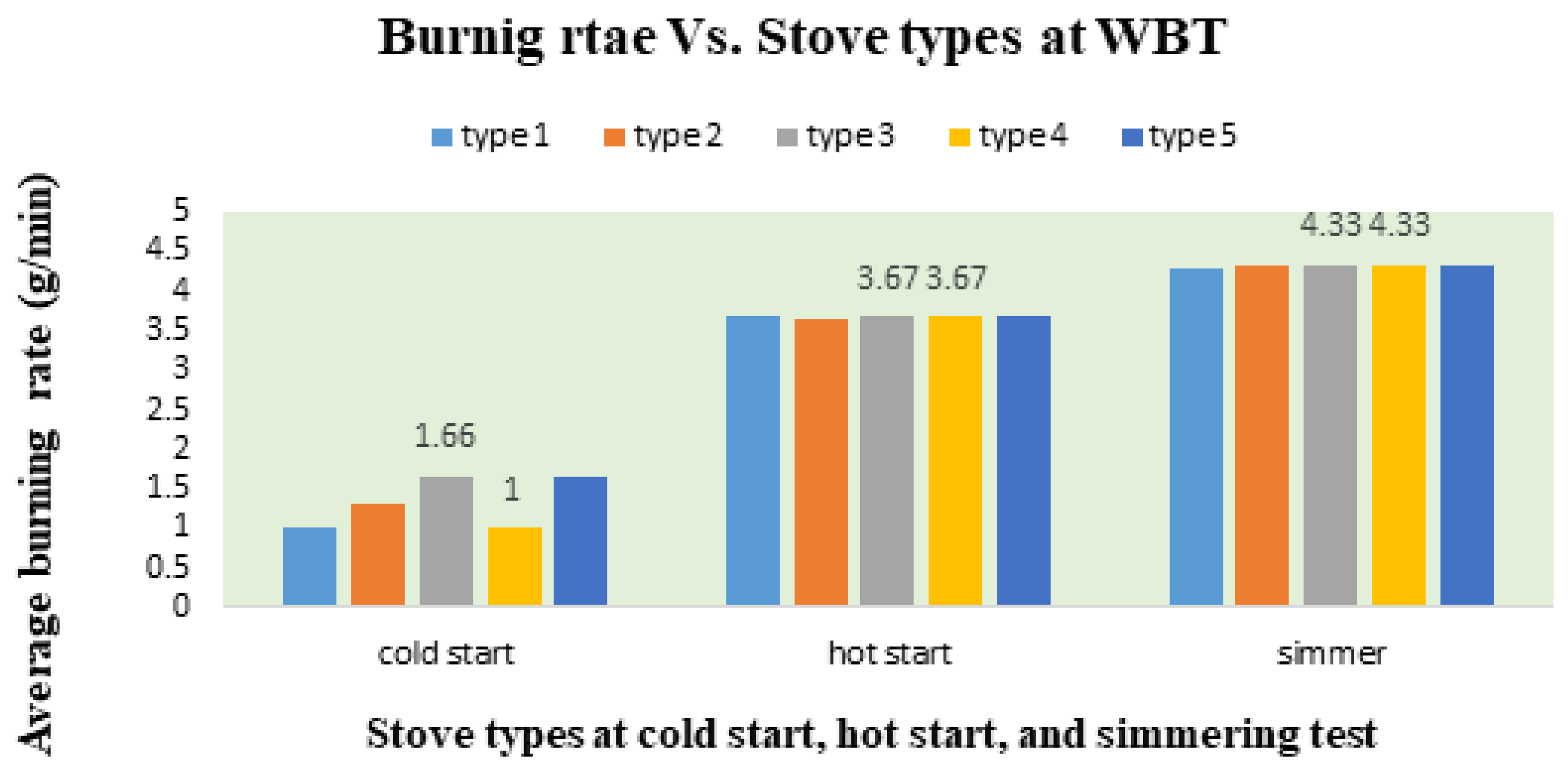

3.4. Burning Rate

The differences in burning rates for the stove types selected in the study area are shown in

Figure 6.

During the hot and simmer phases, all stoves burned approximately equal amounts of fuel within a specific amount of time. This means, once the stoves warm up, their fuel consumption remains constant, regardless of stove type. On the other hand, during the cold start phase, the burning rates for type 1, type 2, type 3, type 4, and type 5 stoves were 1.12, 1.33, 1.67, 1, and 1.6 g/min, respectively. This implies there is a significant variation in the combustion behavior of the different stove types. The highest burning rates were exhibited by types 3 and 5, which indicate that the release of thermal energy was very fast. This may be beneficial for cooking quickly, but it can also mean inefficient fuel use when the heat has not been transferred effectively to the cooking vessel. On the other hand, type 4 had the lowest burning rate of 1 g/min and is best at conserving fuel. All in all, these differences underscore the need for optimizing stove design not only for the combustion rate of fuel but also the efficiency of heat transfer for the intended cooking use.

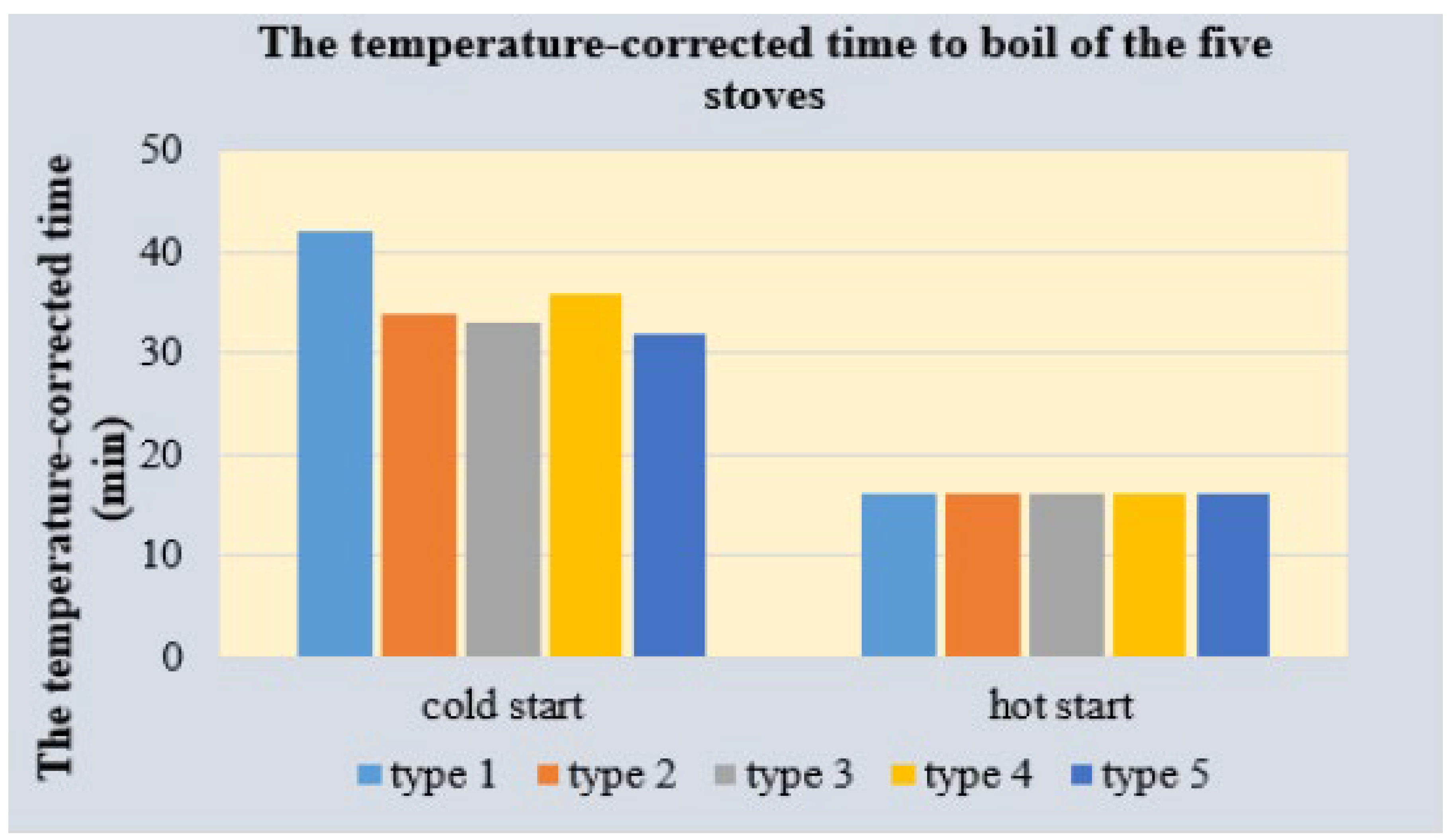

3.5. Temp-Corrected Time to Boil (TCTB)

Figure 7 compares the average temperature-corrected time to boil water for each of the five stoves. At the cold start, type 1 took the longest time to boil (42 minutes), while type 5 was the shortest (32 minutes). The body of Type 1 is fully made from clay; as a result, the weight of these stoves is high. Due to this, a significant amount of energy will be consumed to pre-heat the body of the stove; as a result, the time required to boil the water was high. Similar results were published by [

18]. Whereas type 5 required the lowest temp-corrected time to boil, this might be due to the low thermal mass allowed for rapid heat-up. In type 2, the metal body conducts heat quickly, but the clay insulation retains heat, reducing losses. In this stove, it still requires some heat-up time due to the insulation, but it performs better than a fully clay stove. Type 3 is made up of metal and has low thermal mass, so it heats up quickly. However, a lack of insulation means heat outflows rapidly, making it less efficient in retaining heat. It is faster than a clay stove but less consistent due to heat loss. In type 4, the insulation reduces heat loss, keeping the combustion chamber hotter, and it takes slightly longer than an uninsulated rocket stove, but it performs better once heated.

3.6. Ranking of Selected Improved Charcoal Cookingstoves

In this study, the main criteria for ranking improved charcoal cooking stoves are performance. The experimental stoves can be ranked from best to least using the performance analysis presented before. The criteria considered are the time to boil, fuel consumption rate, burning rate, firepower, and thermal efficiency. Although Ethiopia is the third country in the production of charcoal next to Brazil and Nigeria [

39,

40], it is important to compare stoves based on thermal efficiency, average fuel consumption, firepower (w), and time taken to boil water. Different scholars have different views on the selection of stoves. For instance, for communities that have high availability of charcoal, less cost it is recommended to evaluate using thermal efficiency. In the other case, for societies where biomass fuel/charcoal is costly, it is essential to evaluate using average fuel consumption. Finally, for those who have less time, it is necessary to consider the time taken to boil/cook, especially for those government employees in Ethiopia.

The thermal performance in this study followed the order TYPE 4 > TYPE 2 > TYPE 1> TYPE 3 > TYPE 5. Regarding fuel consumption at hot start, the results obtained were TYPE 5 > TYPE 3 > TYPE 1 > TYPE 2 > TYPE 4. In addition, fire power rate, which is the average power utilization to boil water, was obtained following the order as TYPE 4 < TYPE 2 < TYPE 1 < TYPE 3 < TYPE 5. Whereas the burning rate of the five stoves follows the order TYPE 4 < TYPE 1 < TYPE 2 < TYPE 5 < TYPE 3. In case of Temp-corrected time to boil (TCTB) at the cold start, the following results were obtained in the order TYPE 5 < TYPE 3 < TYPE 2 < TYPE 4 < TYPE 1 and at the hot start, all stove types show almost similar Temp-corrected time to boil (TCTB).

Overall, in this study, it is recommended for the community to use Type 4 charcoal cooking stoves. Furthermore, in this study area, for those who have an economic problem, to buy more modified/improved charcoal cooking stoves, it is recommended to use TYPE 1 (clay stove) rather than using TYPE 3 and TYPE 5. Thus, the Type 4 stove (rocket stove with insulation) had a better performance and low burning rate compared to others is generally recommended, and it is imperative to change Ethiopia’s cooking technologies policy. Finally, non-governmental organizations, private investors and emergency relief organizations should introduce this type of stove in all communities by providing a financial subsidy for low-income communities.

4. Conclusions

Energy poverty is high in developing countries, and people use a variety of types of charcoal cooking stoves in Wereta town. Water boiling test results demonstrate significant variations in performance across the five stove types. Type 4 (Rocket stove with insulation) emerged as the most efficient, exhibiting the highest thermal efficiency (35%). Type 2 (cylindrical stove insulated with mud) also performed well, ranking second in overall efficiency. In contrast, Type 5 had the lowest thermal efficiency (26.7%) and the highest specific fuel consumption (52 g/L). These performance differences can be attributed to variations in stove design, insulation, thermal mass and material conductivity. Stoves with poor insulation and higher thermal mass tend to consume more fuel, leading to lower thermal efficiency and greater environmental impact. To sum up, the government should integrate high-efficiency stoves (particularly Type 4 and Type 2) into national energy programs to reduce deforestation caused by excessive fuel consumption. Additionally, stakeholders should educate users on the economic and environmental benefits of adopting improved stoves, emphasizing fuel savings and reducing emissions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Shumet Geremew Asabie: Conceptualization, Methodology, and Software, Data collection and analysis, Writing- Original draft preparation, Visualization, Investigation, Supervision, and Validation. Wondimhunegne Misganaw Alemu: Conceptualization, Methodology, and Software, Data collection, Visualization, Reviewing, and Editing. Getu Maru Demelash: Conceptualization, Methodology, and Software, Supervision, Reviewing, Editing, and Validation.

Funding

The authors declare that there is no funding for the preparation and publication of this article.

Ethical approval

This study did not involve human life directly, clinical trials, or animal experiments requiring ethical approval. The assessment was based on publicly available data, field observations, and previous studies. Where applicable, the study complied with the ethical guidelines of Gafat Institute of Technology Research and community service directorate, Debre Tabor University.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this study are accessible from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

We, the authors, declare that there are no known competing financial interests for the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Debre Tabor University for providing support and access to Laboratory, under the Chemical Engineering Department. Furthermore, we authors acknowledge Teshale Adane (PhD) for his guidance and seminar presentation on how to prepare and submit a manuscript in reputable journals.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and consent to its publication in the Journal of Energy, Sustainability, and Society.

References

- K. De La Hoz C and W. A. González, “Energy performance and variability of an improved top-lit updraft biomass cookstove under a water boiling test protocol,” Energy Sources, Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff., vol. 00, no. 00, pp. 1–20, 2020, doi: 10.1080/15567036.2020.1819473. [CrossRef]

- M. Rasoulkhani, M. Ebrahimi-Nik, M. H. Abbaspour-Fard, and A. Rohani, “Comparative evaluation of the performance of an improved biomass cook stove and the traditional stoves of Iran,” Sustain. Environ. Res., vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 438–443, 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.serj.2018.08.001. [CrossRef]

- Tariku Woldesemayate and S. M. Atnaw, “A review on design and performance of improved biomass cook stoves,” in Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social-Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering, LNICST, Springer International Publishing, 2020, pp. 557–565. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-43690-2_41. [CrossRef]

- E. Chica and J. F. Pérez, “Development and performance evaluation of an improved biomass cookstove for isolated communities from developing countries,” Case Stud. Therm. Eng., vol. 14, no. March, p. 100435, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.csite.2019.100435. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Ashagrie, S. G. Asabie, W. M. Alemu, A. S. Tadesse, T. Dires, and G. Maru, “Perception and barriers to improved charcoal cookstoves adoption in Wereta, Ethiopia,” BMC Public Health, vol. 24, no. 1, p. 3454, Dec. 2024, doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-20938-3. [CrossRef]

- T. Makonese and C. M. Bradnum, “Design and performance evaluation of wood-burning cookstoves for low-income households in South Africa,” J. Energy South. Africa, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 1–12, 2018, doi: 10.17159/2413-3051/2018/V29I4A4529. [CrossRef]

- Manaye, S. Amaha, Y. Gufi, B. Tesfamariam, A. Worku, and H. Abrha, “Fuelwood use and carbon emission reduction of improved biomass cookstoves: evidence from kitchen performance tests in Tigray, Ethiopia,” Energy. Sustain. Soc., vol. 12, no. 1, Dec. 2022, doi: 10.1186/s13705-022-00355-3. [CrossRef]

- Gizachew and M. Tolera, “Adoption and kitchen performance test of improved cook stove in the Bale Eco-Region of Ethiopia,” Energy Sustain. Dev., vol. 45, pp. 186–189, 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2018.07.002. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen et al., “Efficiencies and pollutant emissions from forced-draft biomass-pellet semi-gasifier stoves: Comparison of International and Chinese water boiling test protocols,” Energy Sustain. Dev., vol. 32, pp. 22–30, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2016.02.008. [CrossRef]

- P. Arora, P. Das, S. Jain, and V. V. N. Kishore, “A laboratory based comparative study of Indian biomass cookstove testing protocol and water boiling test,” Energy Sustain. Dev., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 81–88, 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2014.06.001. [CrossRef]

- J. Hafner et al., “A quantitative performance assessment of improved cooking stoves and traditional three-stone-fire stoves using a two-pot test design in Chamwino, Dodoma, Tanzania,” Environ. Res. Lett., vol. 13, no. 2, 2018, doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa9da3. [CrossRef]

- B. A. Shanono, I. Diso, and I. Garba, “Performance and Emission Characteristics of Liquid Biofuels Cooking Stoves,” vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 219–238, 2020.

- G. Boafo-Mensah, K. M. Darkwa, and G. Laryea, “Effect of combustion chamber material on the performance of an improved biomass cookstove,” Case Stud. Therm. Eng., vol. 21, p. 100688, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.csite.2020.100688. [CrossRef]

- “Global Burden of Disease 2021,” 2021.

- T. Abasiryu, A. Ayuba, and A. Zira, “Performance evaluation of some locally fabricated cookstoves in Mubi, Adamawa State, Nigeria,” Niger. J. Technol., vol. 35, no. 1, p. 48, 2015, doi: 10.4314/njt.v35i1.8. [CrossRef]

- K. B. Sutar, R. Singh, A. Karmakar, and V. Rathore, “Experimental investigation on thermal performance of three natural draft biomass cookstoves,” Energy Effic., vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 749–755, 2019, doi: 10.1007/s12053-018-9705-x. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, L. Duanmu, P. Yuan, M. Ning, and Y. Liu, “Experimental Study of Thermal Performance Comparison Based on the Traditional and Multifunctional Biomass Stoves in China,” Procedia Eng., vol. 121, pp. 845–853, 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2015.09.039. [CrossRef]

- E. Chica and J. F. Pérez, “Development and performance evaluation of an improved biomass cookstove for isolated communities from developing countries,” Case Stud. Therm. Eng., vol. 14, no. May, p. 100435, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.csite.2019.100435. [CrossRef]

- B. Ayalew, M. Bahir, and E. Engineering, “Design and Performance Evaluation of Rocket Stove for Cleaner Cooking in Rural Ethiopia SUBJECT AREAS”, doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-19148/v1. [CrossRef]

- C. Someswararao, G. Prasanna Kumar, and C. V. V. Satyanarayana, “Performance evaluation of improved cook stoves,” Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol., vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 621–624, 2012, doi: 10.22271/tpi.2020.v9.i8b.5012. [CrossRef]

- Tariku Woldesemayate and S. M. Atnaw, “A Review on Design and Performance of Improved Biomass Cook Stoves BT - Advances of Science and Technology,” N. G. Habtu, D. W. Ayele, S. W. Fanta, B. T. Admasu, and M. A. Bitew, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020, pp. 557–565.

- J. Okino, A. J. Komakech, J. Wanyama, H. Ssegane, E. Olomo, and T. Omara, “Performance Characteristics of a Cooking Stove Improved with Sawdust as an Insulation Material,” J. Renew. Energy, vol. 2021, pp. 1–12, May 2021, doi: 10.1155/2021/9969806. [CrossRef]

- G. Boafo-mensah, K. Mensah, and G. Laryea, “Case Studies in Thermal Engineering Effect of combustion chamber material on the performance of an improved biomass cookstove,” Case Stud. Therm. Eng., vol. 21, no. April, p. 100688, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.csite.2020.100688. [CrossRef]

- P. Adhikari, A. Adhikari, S. K. Dhital, B. Shrestha, and H. B. Dura, “Design and Performance Analysis of Institutional Cooking Stove for High Hill Rural Community of Nepal,” Kathmandu Univ. J. Sci. Eng. Technol., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–5, 2020, doi: 10.3126/kuset.v14i1.63466. [CrossRef]

- Bantu, G. Nuwagaba, S. Kizza, and Y. K. Turinayo, “Design of an Improved Cooking Stove Using High Density Heated Rocks and Heat Retaining Techniques,” J. Renew. Energy, vol. 2018, pp. 1–9, 2018, doi: 10.1155/2018/9620103. [CrossRef]

- E. Chica and J. F. Pérez, “Case Studies in Thermal Engineering Development and performance evaluation of an improved biomass cookstove for isolated communities from developing countries,” Case Stud. Therm. Eng., vol. 14, no. March, p. 100435, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.csite.2019.100435. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Ghiwe et al., “The Influence of Stove Materials on the Combustion Performance of a Hybrid Draft Biomass Cookstove The Influence of Stove Materials on the Combustion Performance of a Hybrid Draft Biomass Cookstove,” 2022, doi: 10.1080/00102202.2022.2138710. [CrossRef]

- F. Pasha, M. A. Ali, H. Roy, and M. M. Rahman, “Designing a modified Tchar stove and evaluation of its thermal performance,” Clean. Chem. Eng., vol. 5, no. January, p. 100096, 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.clce.2023.100096. [CrossRef]

- K. Mutuku, F. Njoka, and M. Hawi, “Design , Development and Evaluation of a Modified Improved Charcoal Cookstove for Space Heat and Power Generation,” vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 119–129, 2022.

- Hailu, “Development and performance analysis of top lit updraft: natural draft gasifier stoves with various feed stocks,” Heliyon, vol. 8, no. 8, Aug. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10163. [CrossRef]

- Y. T. Wassie and M. S. Adaramola, “Analysis of potential fuel savings, economic and environmental effects of improved biomass cookstoves in rural Ethiopia,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 280, Jan. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124700. [CrossRef]

- E. Dresen, B. DeVries, M. Herold, L. Verchot, and R. Müller, “Fuelwood savings and carbon emission reductions by the use of improved cooking stoves in an afromontane forest, Ethiopia,” Land, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 1137–1157, Jun. 2014, doi: 10.3390/land3031137. [CrossRef]

- Y. A. Zerihun, “The benefits of the use of biogas energy in rural areas in Ethiopia: A case study from the Amhara National Regional State, Fogera District,” African J. Environ. Sci. Technol., vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 332–345, 2015, doi: 10.5897/ajest2014.1838. [CrossRef]

- Garland, S. Delapena, R. Prasad, C. L’Orange, D. Alexander, and M. Johnson, “Black carbon cookstove emissions: A field assessment of 19 stove/fuel combinations,” Atmos. Environ., vol. 169, pp. 140–149, 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.08.040. [CrossRef]

- L. Kåre, H. Mtoro, and M. Ulrich, “Multiple biomass fuels and improved cook stoves from Tanzania assessed with the Water Boiling Test,” Sustain. ENERGY Technol. ASSESSMENTS, vol. 14, pp. 63–73, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.seta.2016.01.004. [CrossRef]

- A. Mekonnen, “Thermal efficiency improvement and emission reduction potential by adopting improved biomass cookstoves for sauce-cooking process in rural Ethiopia,” Case Stud. Therm. Eng., vol. 38, Oct. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.csite.2022.102315. [CrossRef]

- T. Abasiryu, A. Ayuba, and A. Zira, “Performance Evaluation of Some Locally Fabricated Cookstoves in Mubi, Adamawa State, Nigeria,” Niger. J. Technol., vol. 35, no. 1, p. 48, 2015, doi: 10.4314/njt.v35i1.8. [CrossRef]

- K. González, William A. & De La Hoz, “Energy performance and variability of an improved top-lit updraft biomass cookstove under a water boiling test protocol.,” Taylor & Francis. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2020.1819473. [CrossRef]

- J. van Dam, THE CHARCOAL TRANSITION Greening the charcoal value chain to mitigate climate change and improve local livelihoods. Rome, 2017. [Online]. Available: THE CHARCOAL TRANSITION%0AGreening the charcoal value chain to mitigate climate change and improve local livelihoods%0AFOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS.

- Tazebew, S. Sato, S. Addisu, E. Bekele, A. Alemu, and B. Belay, “Improving traditional charcoal production system for sustainable charcoal income and environmental benefits in highlands of Ethiopia,” Heliyon, vol. 9, no. 9, p. e19787, 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19787. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).