1. Introduction

Injera, a spongy flatbread made from teff, is Ethiopia’s staple and culturally significant food, consumed daily across nearly every household. Its preparation is highly energy-intensive, traditionally carried out using wood-fired stoves. This process contributes significantly to national fuelwood consumption and places pressure on forest resources. The inefficiency of conventional injera baking methods, particularly the widespread use of three-stone stoves, results in high energy demands and extensive environmental degradation [1].

Ethiopia’s energy mix remains dominated by traditional biomass sources, which account for approximately 89% of the total national energy supply. In contrast, modern energy sources such as petroleum and electricity contribute only 7.7% and 3%, respectively, despite large investments in hydropower infrastructure [2]. The ongoing reliance on firewood for injera baking not only limits progress toward sustainable energy goals but also accelerates deforestation.

Yet, Ethiopia is well-positioned to transition toward cleaner alternatives, particularly biogas. With an estimated 56 million cattle generating about 280,000 tons of manure daily [3], there is a substantial resource base for anaerobic digestion. Household-scale biogas systems can produce between 0.5 and 1.2 m³ of biogas per day from livestock manure [4]. Co-digestion with agricultural residues, such as cereal straws and coffee husks—of which over 12 million tons are produced annually—can further enhance methane output by up to 22% [5]. Additionally, integrating wastewater treatment streams, such as brewery effluent, has been shown to increase biogas production and improve waste management efficiency [6].

Technological developments are enhancing the performance and viability of biogas systems. Innovations such as artificial intelligence-based digester control, nanoparticle-enhanced microbial activity, and IoT-enabled monitoring have contributed to improved methane yield, thermal stability, and system reliability [7]. Financial feasibility studies in Ethiopia suggest that household-scale biogas systems can achieve economic viability within 3.2 to 4.1 years, depending on regional conditions [8]. However, widespread adoption faces several challenges, including high initial costs limited user maintenance capacity, and cultural preferences for traditional wood-fired injera preparation [9].

Despite these barriers, biogas technology presents a compelling pathway for Ethiopia’s energy transition [9]. It supports renewable energy production, reduces pressure on natural forest resources, and provides co-benefits such as digestate for use as organic fertilizer [10]. While biogas-based injera stoves represent a promising alternative to traditional biomass systems, current designs still exhibit limitations in heat distribution, which affects the uniformity of injera baking [11]. While solar cookers have been considered for injera preparation, their reliance on variable sunlight and limited heat output render them unsuitable for meeting the high and consistent thermal demands of traditional injera baking [12].

This research aims to develop and evaluate an optimized biogas stove specifically designed for injera baking, targeting four key areas: (1) improving thermal efficiency by enhancing heat transfer mechanisms; (2) maximizing fuel savings through air-fuel ratio optimization; (3) achieving uniform heat distribution compatible with traditional injera preparation methods; and (4) assessing environmental benefits such as firewood displacement and CO₂ emission reduction. The stove is intended to serve as a practical and culturally aligned solution for both household and small-scale commercial applications in rural and peri-urban Ethiopia.

2. Method and Materials

2.1. Design and Construction of the Biogas-Powered Injera Baking Stove

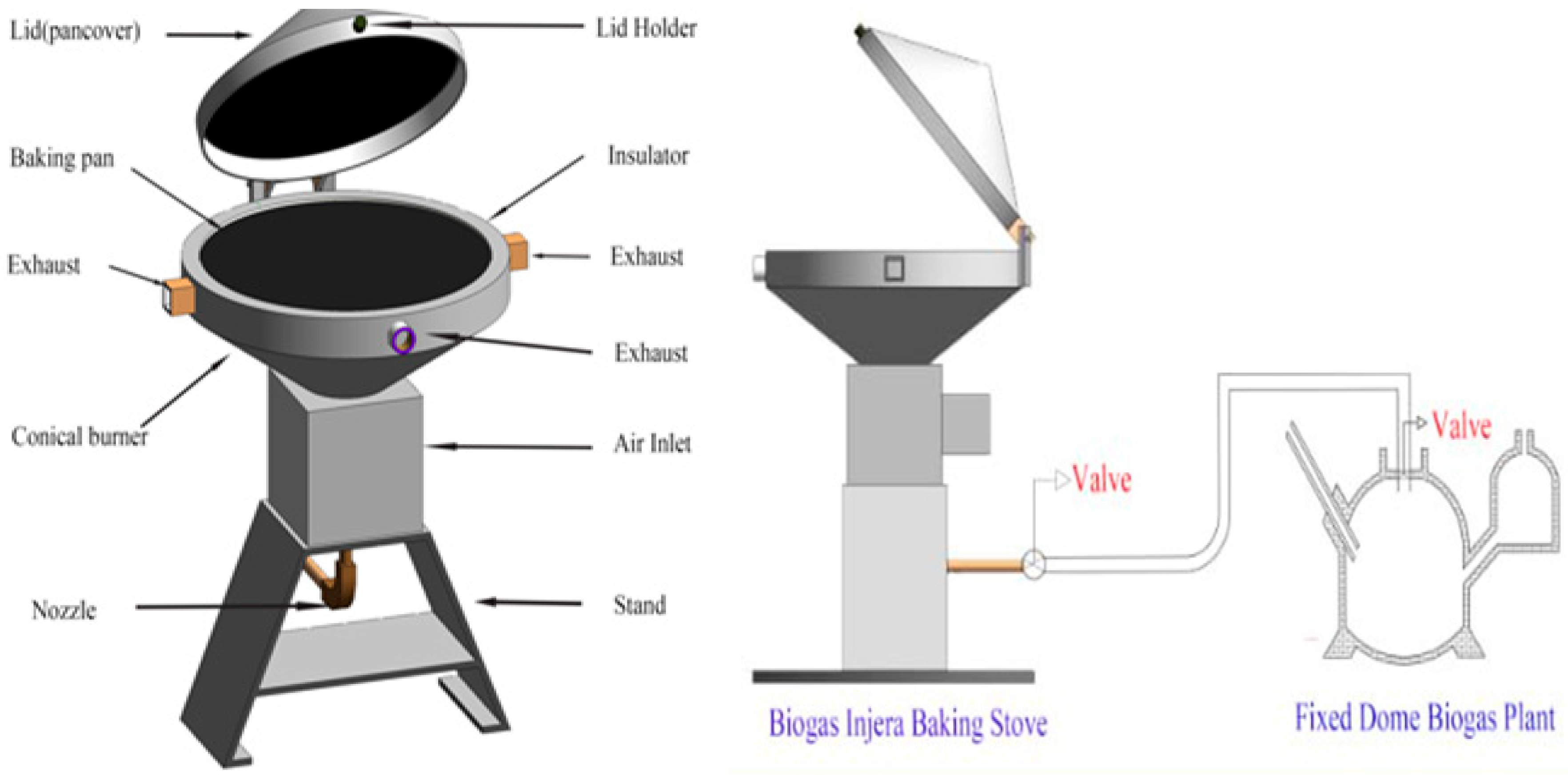

The biogas-powered injera baking stove was designed and constructed from mild steel, galvanized mild steel was used for the gas pipe. The stove was fabricated using a combination of rolling, cutting, drilling, and welding techniques. Gypsum was chosen as the insulating material. The design features a conical combustion chamber at the top of the stove, where combustion occurs. The combustion chamber, with a diameter of 450 mm and fixed at a 45° inclination.

Figure 1.

Biogas Injera baking stove.

Figure 1.

Biogas Injera baking stove.

2.2. Instruments, Testing Protocol, and Data Collection

A comprehensive evaluation protocol was developed to assess the biogas-powered injera baking stove, combining controlled laboratory experiments with real-world field observations [13]. The study employed a comparative design, testing the biogas stove using standardized 45 cm clay mitad baking surfaces . All trials followed the ISO 19867-1 (2018) testing standards and were conducted in triplicate to ensure reliability. Key performance metrics included thermal efficiency measured through a modified Water Boiling Test [14], pressure was monitored using water manometers, baking time recorded with precision timers, and cooking surface temperature tracked via infrared thermometer [15]. Injera quality assessment incorporated both quantitative and qualitative measures, including pore uniformity (15±2 pores/in²) evaluated through visual inspection, thickness consistency (2.0±0.3 mm) verified with digital calipers, and mechanical properties tested via standardized folding procedures [16]. The economic analysis utilized established cost-benefit modeling techniques to calculate fuel savings and payback periods, while adhering to the Clean Cooking Alliance's Performance Testing Guidelines for quality assurance [17]. The study utilized various instruments and materials, including a digital weighing scale for measuring batter and injera mass, a thermal imaging camera and infrared thermometer for analyzing heat distribution across the baking pan, a biogas plant as the fuel source, a plastic tank for batter storage, a traditional sefied for removing cooked injera.

Biogas Flow Rate and Pressure

Volumetric biogas flow rates were measured with pressure U-water manometer gauge (

Figure 2), while flow dynamics were modeled using a modified Bernoulli equation, [18]

where Cd (0.85) is the discharge coefficient, A

0 the nozzle area, P the absolute pressure, and s the biogas density (0.94 kg/m³ at STP). The key equation (2) that relates gas pressure to flow is Bernoulli’s theorem (assuming incompressible flow) is as follows [19].

2.3. Preheating, Baking Time, and Idle Time

The thermal and operational performance of the optimized biogas injera stove was assessed by measuring three key time parameters: preheating time (duration to reach optimal baking temperature of 230 °C [20], baking time (active injera production period per batch), and idle time (intervals between batches with the stove lit but inactive) .

Measurements were conducted under standardized conditions with a fixed biogas flowrate of 0.6 m³/hr. Trained operators manually recorded timings using digital stopwatches. Data collection began at ignition (preheating), first batter pouring (baking), and between batches (idle). Each trial included three full baking cycles, with all values logged in triplicate to ensure consistency and reliability (ISO 19867-1:2018).

2.4. Surface Temperature

To support heat loss estimation and combustion analysis, surface temperatures were recorded at critical components of the stove: the top and bottom surfaces of the injera baking pan, the stove cover, the combustion chamber cone, and the insulation layer [21]. These measurements are crucial for identifying thermal gradients and loss pathways that impact efficiency and user safety [22].

Temperature data were collected under steady-state conditions using infrared thermometer placed at designated points on the stove body. The results are summarized in

Table 1.

2.5. Environmental Influence on Quality of Injera and Baking Time

Moisture content was analyzed using AOAC method [23] . Weight (W) of the dough and weight of water was placed in plastic container and weight of injera is measured after baking.

The initial moisture content (

M0) of the batter was determined by weighing the individual weight of water (Ww) and flour (wf) used in preparation.

M0 = Initial moisture content and It was calculated as follows [24].

= Weight of water

= Weight of flour

As the batter bakes, the moisture content M(t) changes as water evaporates. The rate of moisture loss can be modeled using the evaporation equation [25]:

Where:

α = Evaporation constant (depends on batter, airflow, and altitude).

Tinj = Injera surface temperature (°C).

Tambient = Ambient temperature (which varies with altitude)

= Initial Moisture Content

The baking time for injera was calculated using an evaporation-based model incorporating environmental parameters and a crust correction factor (

Table 2). The fundamental equation for baking time determination is:

t represents the total baking time (seconds)

M₀ is the initial moisture content of the batter (dimensionless)

M(t) is the target moisture content after baking (dimensionless)

α denotes the evaporation constant (s⁻¹°C⁻¹), adjusted for local conditions

Tinj is the injera surface temperature during baking (°C)

Tamb is the ambient temperature (°C)

C crust is the crust correction factor (dimensionless)

3. Energy Analysis

Heat transfer within the stove was analyzed using standard conduction, convection, and radiation equations. The total energy required for baking was modeled. The heat energy demand of a biogas-powered Injera baking stove can be calculated using the following fundamental equation [26]:

Where:

Q = Total heat energy required (in MJ )

= Mass of batter (Mitad)

Cp = Specific heat capacity of the batter

= Boiling Temp of water

Room Temp

Qloss = Heat lost to surroundings due to inefficiency (radiation, convection, conduction)

= (Initial moisture content and Final moisture content )

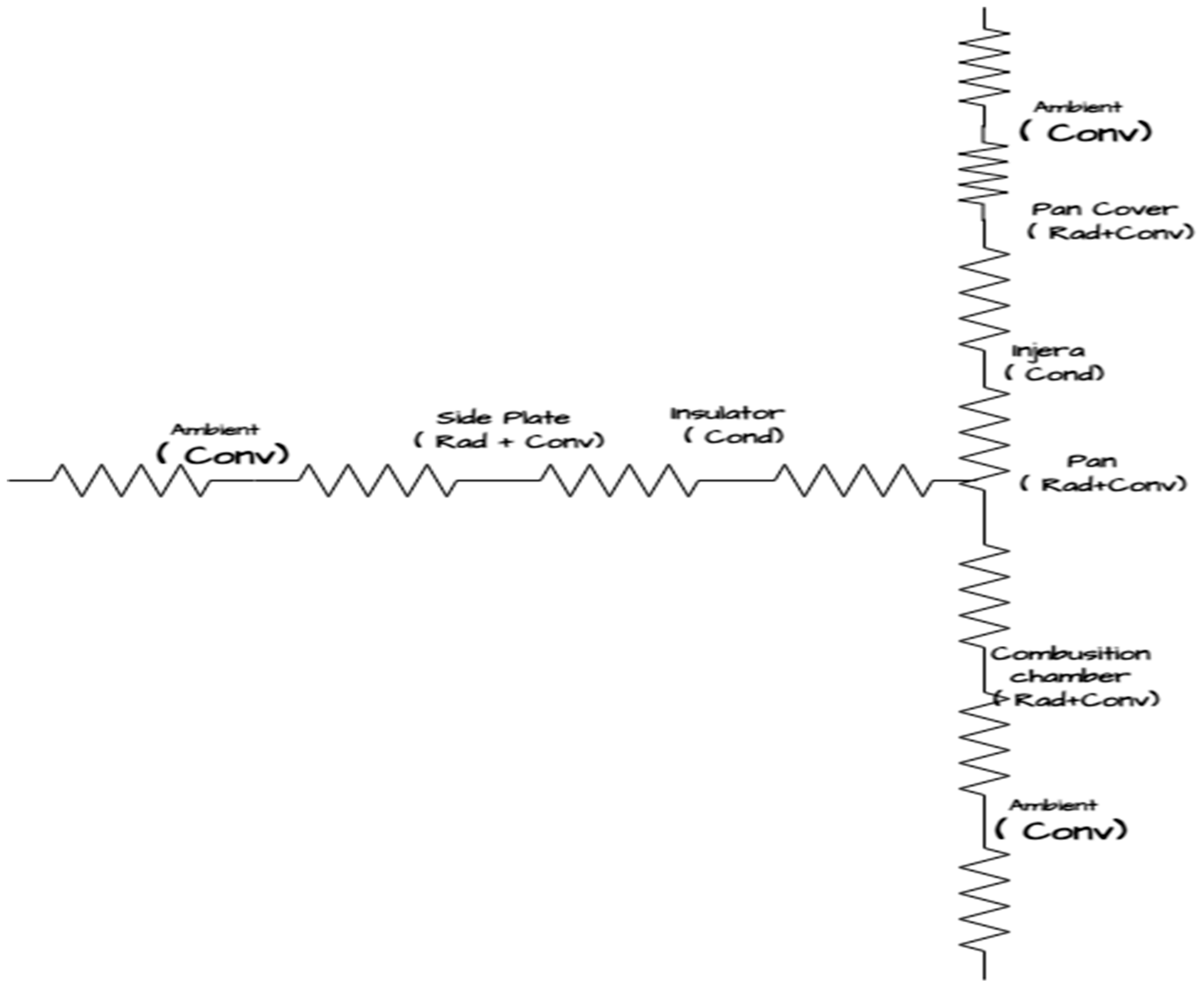

The major structural components contributing to heat loss include the aluminum pan cover, the bottom, and the side surfaces of the baking stove. Heat is transferred from the primary heat source—the injera baking pan—to the surrounding components and the baked product (injera).

Figure 3 schematically represents the paths of heat flow through the stove structure, highlighting radiation and convection as the dominant heat transfer mechanisms. Accordingly, the total heat loss from the stove system was estimated by summing up radiative and convective losses from the top, bottom, and sides, based on the following equation derived from standard heat transfer principles [27].

Total heat loss (

Qlosses) was calculated as the sum of radiative (Q

rad) and convective (Q

conv) losses from each region in equation 4 :

Thermal energy losses were evaluated via radiation and convection from three critical regions as shown in

Figure 3.

Top: Baking pan → aluminum cover → ambient

Bottom: Baking pan → combustion cone → ambient

Side: Pan/cone → gypsum insulation → ambient

The net radiative heat transfer between two gray, diffuse surfaces with different temperatures and emissivity is described by the generalized Stefan–Boltzmann law [28]:

The convective heat transfer between the pan ,bottom, upper and side part of Stove :

Convection is the transfer of heat between a stove surface, combustion gases within the stove enclosures and ambient air.

The convective heat transfer is given by Newton’s law of cooling [18]

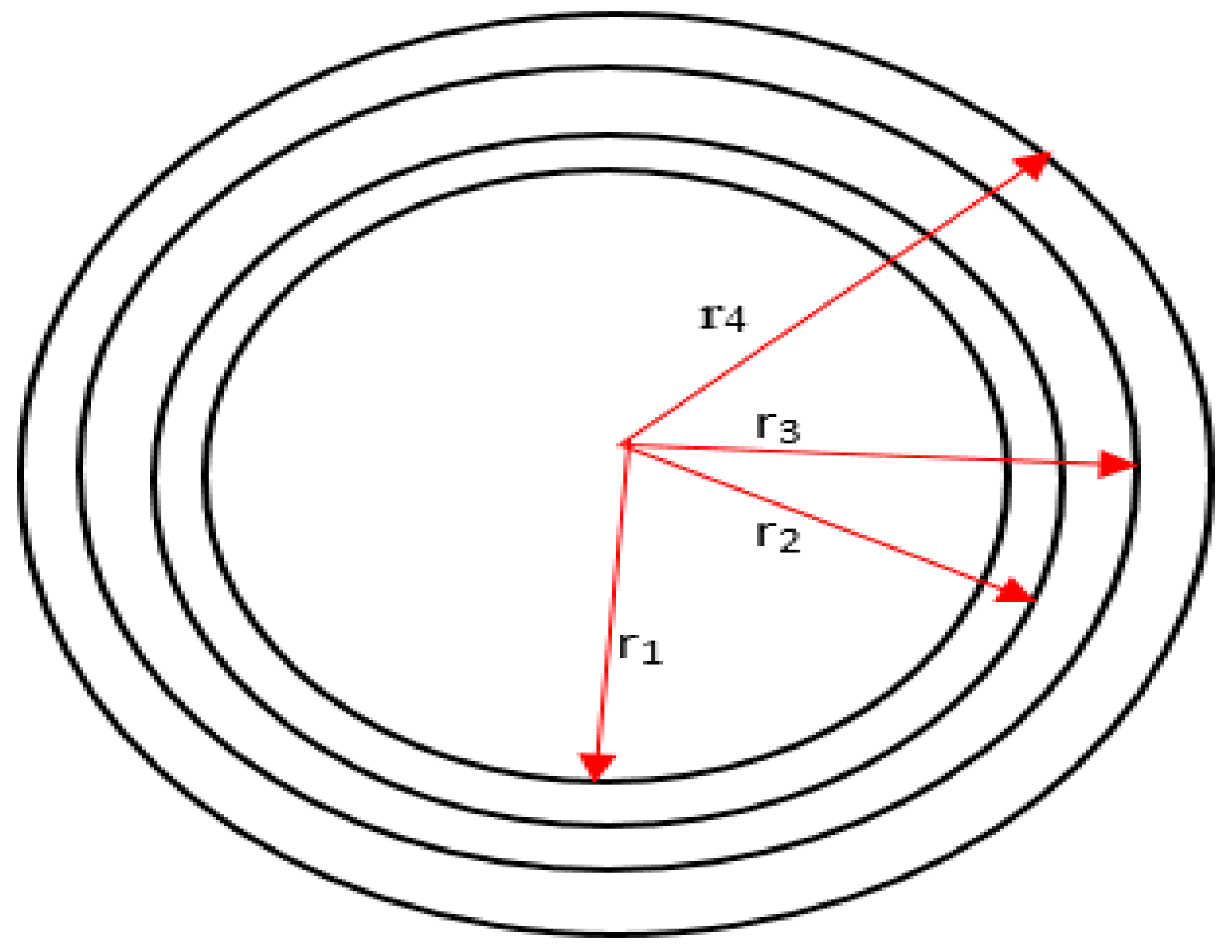

Heat Transfer Between the Pan and Side Part of the Stove

In this study, the upper part of the stove—comprising a cylindrical pan fabricated from mild steel and surrounded by gypsum insulation—serves as a critical pathway for heat flow [29]. The heat transfer between the pan and the side structure of the stove involves a series of heat transfer mechanisms: convection from the hot gases or inner stove volume to the inner surface of the steel wall, conduction through the wall, and convection from the outer wall surface to the ambient environment (

Figure 4). This layered mechanism governs the radial energy flow from the high-temperature stove interior to the external environment.

Where, is the temperature on the hot side (o c), is the temperature on the cold side (o c) and r1, r2, r3, r4 are the concentric radius of the internal diameter of different layers. Ks and Kg is the thermal conductivity of steel and gypsum, respectively (W/mK), hi and h0 are the convective heat transfer coefficient.

To accurately estimate the convective heat transfer coefficients in various parts of the biogas injera stove, empirical correlations based on Nusselt number (Nu) were employed (

Table 3). These correlations relate the Nusselt number to the Rayleigh number (Ra) and are applicable for natural convection regimes, as observed in the stove system. Following the guidelines in Reference [32]. This correlation is suitable for horizontal flat plates subjected to natural convection.

3.1. Thermal Efficiency

Thermal efficiency is a critical performance metric for evaluating the effectiveness of a biogas-powered injera baking stove, as it quantifies the proportion of energy extracted from the biogas fuel and converted into useful heat for baking injera [32]. In this study, thermal efficiency was evaluated based on both the sensible and latent heat involved in the baking process and the input energy derived from biogas consumption using parameters (

Table 4) [33].

The energy input to the stove is derived from the biogas used during the baking process. The biogas consumption is determined by the biogas flow rate and the calorific value of the biogas [34].

Total energy consumed= Total biogas consumed. Calorific value of biogas

Combustion Stoichiometry, Air–Fuel Equivalence Ratio (λ) and Flame Color

The combustion of gas involves mixing air with fuel gas, igniting the biogas resulting in air-gas mixture. The chemical reaction of combustion of biogas containing 60 % methane and 40 % carbon dioxide and air mixture is shown below [35].

To optimize combustion performance, stoichiometric analysis was conducted based on the biogas composition utilized in this study (60% CH₄ and 40% CO₂). The stoichiometric air requirement was determined to be approximately 5.72 m³ of air per 1 m³ of biogas, derived from complete oxidation of methane [10]:

Assuming standard ambient conditions, the required air volume was used to calculate the air–fuel equivalence ratio (λ), defined as [19]:

Combustion regimes were classified as follows:

λ = 1: Stoichiometric (ideal, blue flame),

λ < 1: Fuel-rich (incomplete combustion, yellow flame, soot),

λ > 1: Fuel-lean (cool flame, lower efficiency).

Targeting λ ≈ 1 allowed for maximized combustion efficiency and thermal output while minimizing pollutant formation.

4. Economic Feasibility and Energy Saving Analysis: Input Parameters

The energy savings achieved by transitioning from a traditional wood-burning stove to a biogas stove for injera baking were quantified by comparing the energy consumption of both systems under standardized conditions (

Table 5). The energy savings (ES) were calculated as the difference between the energy required for wood combustion and that for biogas, expressed as [32]:

Where:

mFuel is the mass of fuel consumed (kg or m³),

CV Fuel is the calorific value (MJ/kg or MJ/m³),

η Stove is the stove efficiency expressed as a decimal

is the energy required using biomass,

stove is the energy used by the biogas stove.

To compute the amount of fuel required and the associated cost, following relationship was used [8,32,36]. The actual input energy Qi, needed to meet the useful energy demand depends on the thermal efficiency of the stove. To compare the cost-effectiveness of the biogas-based stove with the traditional wood-fired injera baking stove, we adopt an empirical framework that evaluates the cost of useful energy required for daily baking operations in a typical Ethiopian household [1,36,37]. The daily useful energy demand,

, required to bake injera is calculated as.

The actual input energy Qi, needed to meet the useful energy demand depends on the thermal efficiency of the stove

Where:

LHV = Lower Heating Value of the fuel

Cu = Unit cost of fuel

= Annual cost of fuel

= Cost of fuel

N= Number of injera baked per day,

E= Useful energy required per injera(MJ)

Qd= daily energy demand (MJ/day),

This study employs a quantitative optimization methodology to minimize the Levelized Cost of Biogas (LCB) for

injera baking through Excel-based modeling (

Table 6). The LCB model integrates variables such as feedstock availability, digester efficiency, and household energy demand, aligning with methodologies used in sub-Saharan Africa for decentralized biogas system.

The total Present Value (PV) of costs over the 20-year project lifespan quantifies the current monetary worth of all future expenditures, discounted at an annual rate of 11%. This analysis aggregates the initial capital investment (100/year). The O&M costs are discounted using the annuity formula [36].

The system's total biogas production is calculated by multiplying the daily output by the number of operational days over the project lifespan. The Levelized Cost of Biogas (LCB) is a financial metric that represents the average cost per unit of biogas produced over the entire lifespan of a biogas plant, accounting for all capital and operational expenses. It is expressed in USD per cubic meter (m³) of biogas and allows for [40].

5. Climate Mitigation Estimation

Assuming a potential adoption by five million rural households (

Table 7), national estimates for firewood savings and CO₂ emission reductions were computed to highlight the macro-level implications of technology transition [32,41,42].

= Annual CO₂ emissions from biomass stove (kg CO₂/year)

= Annual CO₂ emissions from biomass stove (kg CO₂/year)

6. Result and Discussion

6.1. Thermal Efficiency

The experimental evaluation of the biogas-powered injera baking stove demonstrated substantial thermal performance improvements when compared to conventional biomass-based stoves. The system achieved a measured thermal efficiency of 36%, representing more than a two-fold increase over traditional three-stone stoves, which typically operate at 10–15% [1,43] .

This notable improvement was primarily the result of several targeted technical innovations, including a precision-engineered 45° conical burner, 3 cm thick gypsum-based insulation, and optimized air-fuel mixing [44], where the excess air coefficient was maintained near λ ≈ 1, ensuring efficient combustion with minimal heat loss [32,45] .

In particular, the conical burner geometry promoted uniform flame distribution and stable blue flame characteristics, indicative of complete combustion, while the insulation minimized conductive losses to the stove body [46]. The integration of these design features enabled the system to reach a thermal efficiency comparable to or exceeding modern improved cookstoves used in other biomass or gas-based applications [47].

The stove's energy requirement per injera was also significantly reduced. On average, the biogas system required only 706 kJ per injera, compared to the 800–1,200 kJ typically consumed by firewood-based baking systems such as the Mirt stove or traditional three-stone arrangements [39]. This represents an energy reduction of approximately 40%, further emphasizing the stove’s efficiency and sustainability advantages.

In addition to improved fuel utilization, the biogas stove contributes to lower indoor air pollution, faster baking cycles, and enhanced user comfort, making it a compelling clean cooking solution aligned with national clean energy strategies and international climate mitigation frameworks [21].

6.2. Flame Color and Combustion Quality

The color of the flame serves as a visual diagnostic for combustion efficiency and completeness [48]. As illustrated in

Figure 5, the optimized biogas stove was designed to maintain a stable blue flame, signifying high combustion efficiency and effective thermal transfer to the baking surface. This feature not only improves overall energy utilization but also reduces indoor air pollution and enhances the quality of the injera. Visual flame assessment therefore serves as a practical and immediate indicator of combustion quality in household energy systems

. A blue flame typically indicates complete combustion, characterized by optimal air-fuel mixing and a high-temperature, clean-burning reaction that results in the efficient conversion of fuel to heat energy. This combustion state also ensures lower emissions of unburned hydrocarbons. In contrast, a yellow or orange flame is a sign of incomplete combustion, often caused by a deficiency in oxygen supply or poor mixing, which results in the formation of soot and other pollutants.

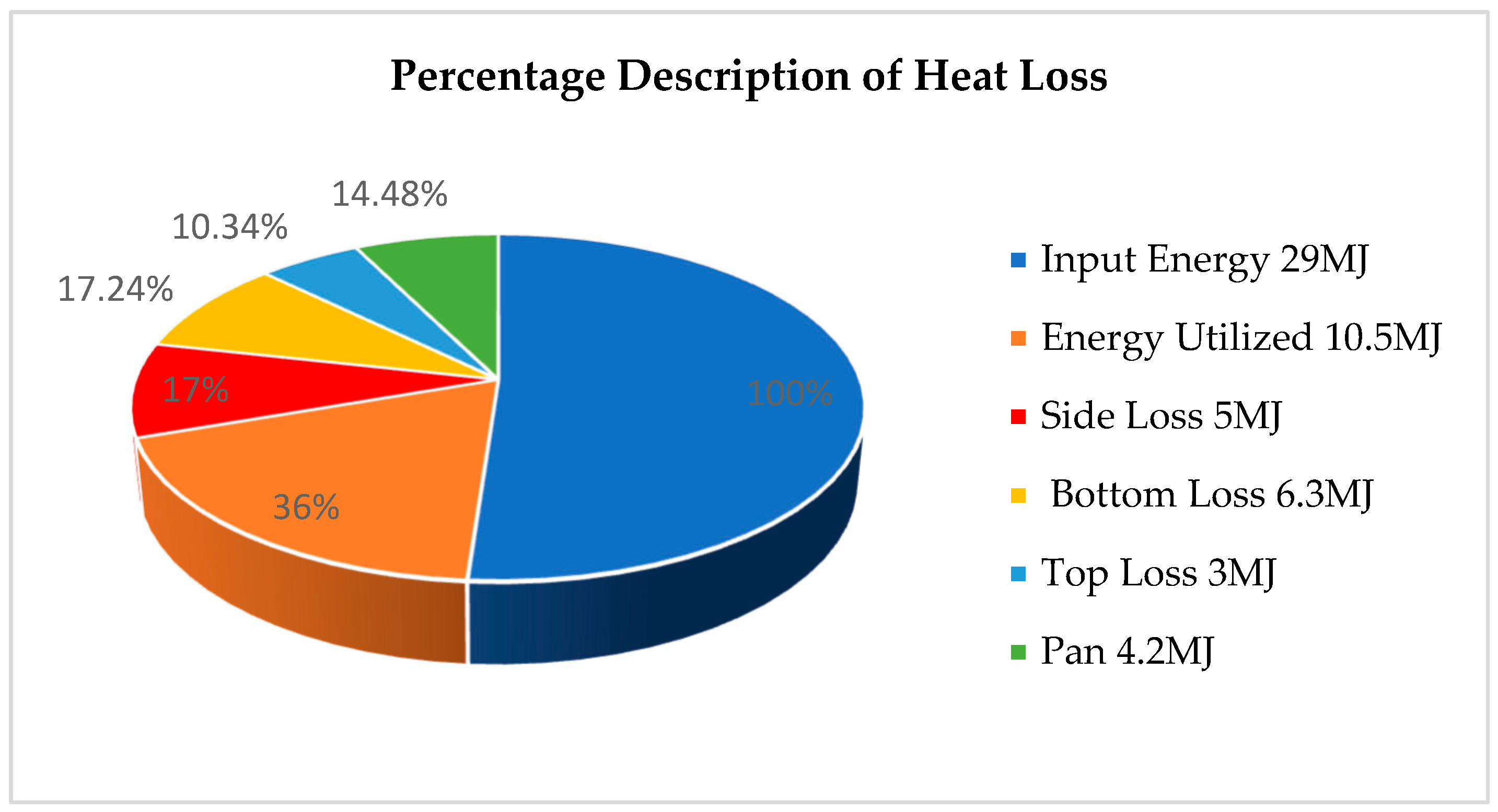

6.3. Heat Loss Characteristics

Accurate evaluation of heat loss pathways in biogas-powered injera baking stoves is essential for improving overall system efficiency. Based on analytical calculations, the heat losses during each baking cycle were estimated from various stove surfaces: 4.2 MJ from the sides, 5 MJ from the bottom, 6.3 MJ from the pan surface, and 3 MJ from the top, as illustrated in

Figure 6. These values correspond to 17.4% heat loss through the bottom, 17% through the sides, 14.48% through the pan, and 10.34% through the top, relative to a total input energy of 29 MJ required to bake 15 injera.

These findings align with earlier studies indicating that uninsulated or poorly shielded stove components can result in substantial thermal losses, especially from the bottom and lateral walls, which are in continuous contact with ambient air or poorly conductive materials [21]. Moreover, radiative and convective heat loss from the pan and top surfaces contributes to overall inefficiency if not properly mitigated through insulation or heat recirculation designs. Hence, addressing these thermal loss points is critical for improving the energy performance and fuel economy of the stove.

6.4. Temperature Profile During Stove Operation

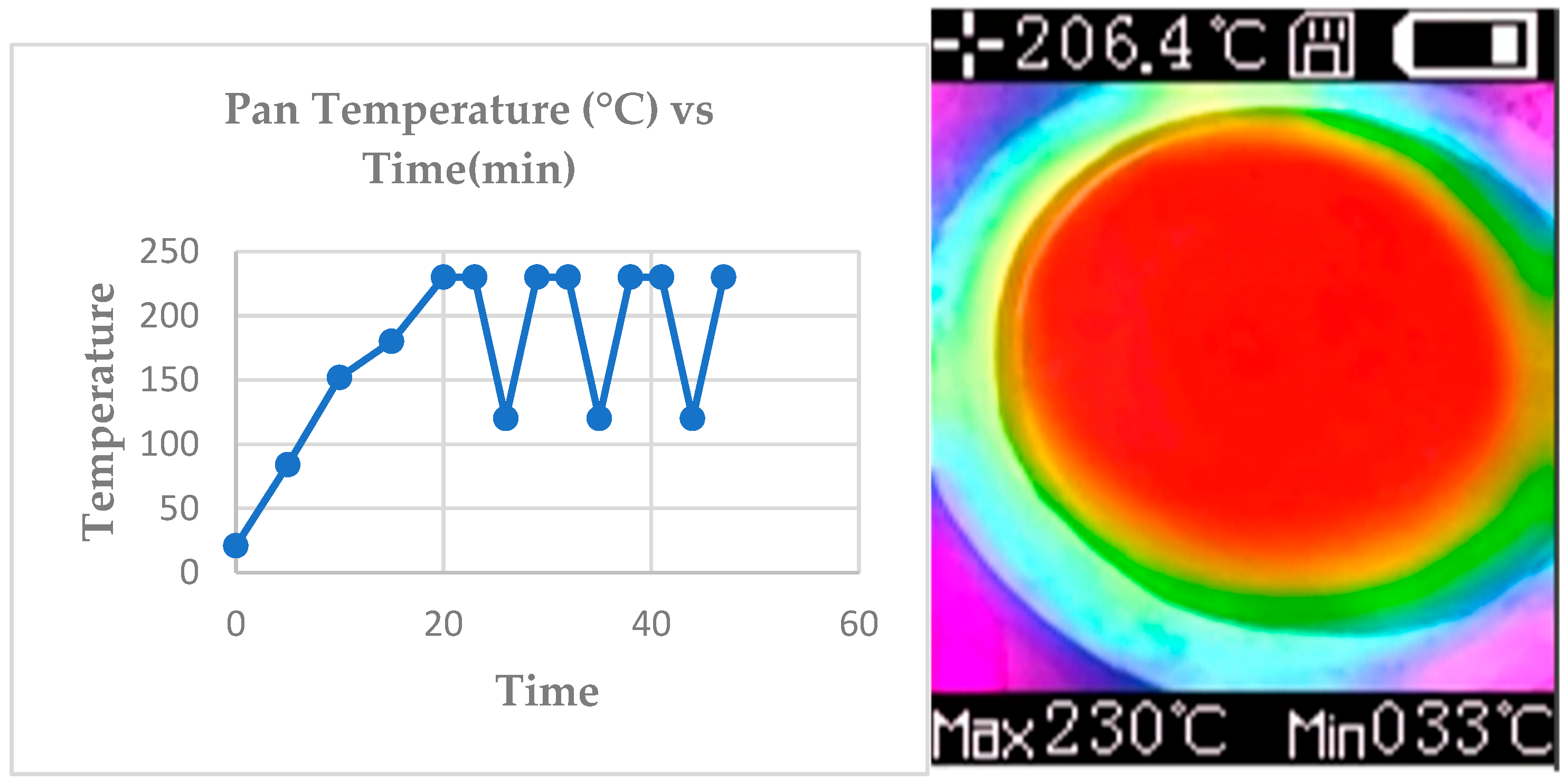

The temperature profile observed during the operation of the biogas injera baking stove reveals three distinct thermal phases: preheating, active baking, and idle. As shown in

Figure 7a, the preheating phase is marked by a gradual rise in temperature from ambient conditions 21°C to the target baking temperature of 230°C within 20 minutes. This rapid thermal response suggests efficient biogas combustion and high heat transfer efficiency between the burner and the pan surface [44]. The ability to reach baking temperatures quickly is a key performance indicator, signifying low energy losses and strong thermal coupling [29] .

During the active baking phase, the pan temperature stabilized around 230°C, with minimal fluctuations. This stability indicates a consistent combustion process and uniform thermal output, which are essential for ensuring even heat distribution and the formation of quality injera with uniform texture and eyelet patterns [2]. Maintaining a steady baking temperature also minimizes variations in injera quality across batches, which is crucial for household acceptability.

As the baking session progresses, a gradual temperature decline is observed during the idle phase, although the surface temperature remains above 120°C for a significant period. This residual heat is beneficial, as it supports immediate subsequent baking without the need for complete reheating—thus reducing biogas consumption [40]. The stove’s ability to retain heat reflects high thermal inertia and effective insulation design, which are advantageous both in terms of energy efficiency and user convenience [49].

Overall, the observed thermal behavior across the three phases—rapid preheating, stable baking, and heat retention—demonstrates the stove’s high energy performance and its suitability for continuous injera baking in domestic contexts [50]. Thermal imaging revealed exceptional heat distribution uniformity across the injera baking surface (

Figure 7b), with temperature differentials consistently maintained within 25°C, a substantial improvement over earlier stove models ([11]). This uniformity in heat distribution was primarily attributed to the conical flame geometry of the optimized biogas burner, which ensured even heat application across the 45 cm clay pan surface—a critical factor for achieving proper injera structure and texture.

The temperature variation of only 25°C across the pan surface is significantly lower than the 55°C variation observed in previous biogas injera baking stoves ([11], reflecting the benefits of improved burner design and pan contact efficiency. Such thermal consistency enhances not only product quality—resulting in uniformly browned, evenly cooked injera—but also contributes to energy savings, as less heat is wasted or unevenly distributed [51].

Moreover, the stable thermal profile reduces the likelihood of undercooked or burnt sections, which often occur with irregular heat zones in traditional setups. These improvements confirm that targeted burner geometry and improved heat transfer mechanisms can significantly elevate both the efficiency and performance of injera baking stoves [47].

When comparing the current biogas stove's performance with that of previous studies, several notable improvements were observed. The initial heating time in this study was reduced to 20 minutes, compared to 25 minutes. Additionally, the baking time for each injera was reduced to 3 minutes, compared to 4 minutes in the earlier study. The reheat time was also shorter, dropping from 4 minutes to 3minutes, thus improving the stove's overall efficiency [52].

These findings suggest that improvements in stove design, such as better heat distribution and faster heating, have contributed to the enhanced performance observed in this study. Furthermore, the lower energy consumption and faster baking times are likely to lead to higher productivity and lower operating costs, making biogas stoves a more viable option for household injera baking.

6.5. CO₂ Mitigation of Biogas Injera Baking Stove

Based on the specified parameters, the annual injera consumption for 5 million rural Ethiopian households is estimated at approximately 7.375 billion kilograms. Utilizing respective specific fuel consumption values, this translates into an estimated 3.944 billion kilograms of wood for traditional biomass stoves and 1.800 billion cubic meters of biogas for improved biogas stoves.

Applying standard CO₂ emission factors—1.83 kg CO₂/kg for wood and 1.9 kg CO₂/m³ for biogas—the total direct combustion-related annual CO₂ emissions are estimated at 7.22 million tons for biomass stoves and 3.42 million tons for biogas stoves. A comparative summary is provided in

Table 2. These results indicate a potential annual reduction of approximately 3.8 million tons of CO₂ if biogas stoves were adopted by the 5 million households currently using biomass.

It is important to note that this analysis focuses exclusively on direct emissions from fuel combustion. However, the broader environmental benefits of biogas adoption extend well beyond these calculations.

The findings underscore that even partial adoption of biogas stoves—reaching 5 million of Ethiopia’s 22 million rural households—can yield significant and measurable climate benefits. Nationwide scaling of this transition could substantially contribute to Ethiopia’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement. Additionally, it aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG 13 (Climate Action), reinforcing the multifaceted value of clean cooking technologies in rural development and climate strategies.

6.6. Energy-Saving Benefits of the Biogas Injera Baking Stove

The analysis reveals a substantial energy saving when transitioning from traditional biomass (wood-fired) stoves to biogas-powered stoves for injera baking in rural Ethiopia. For a population of 5 million households consuming a total of 7.375 billion kilograms of injera annually, the traditional wood-fired stoves require approximately 3.944 billion kilograms of wood, equating to a total energy consumption of 59,160 (TJ). In contrast, the same demand can be met using 1.800 billion cubic meters of biogas, which corresponds to only 36 billion MJ of energy. This translates to a net energy saving of 23,160 TJ per year, or roughly 6.43 TWh. These savings stem from the higher combustion efficiency and better heat transfer characteristics of biogas stoves, as well as the absence of energy losses associated with moisture content in firewood. The 39% reduction in energy use not only underscores the superior thermal performance of biogas stoves but also indicates their potential to significantly lower the national energy burden associated with household cooking. Furthermore, this improvement in energy efficiency directly supports climate goals, resource conservation, and household energy resilience in off-grid rural areas.

6.7. Injera Quality

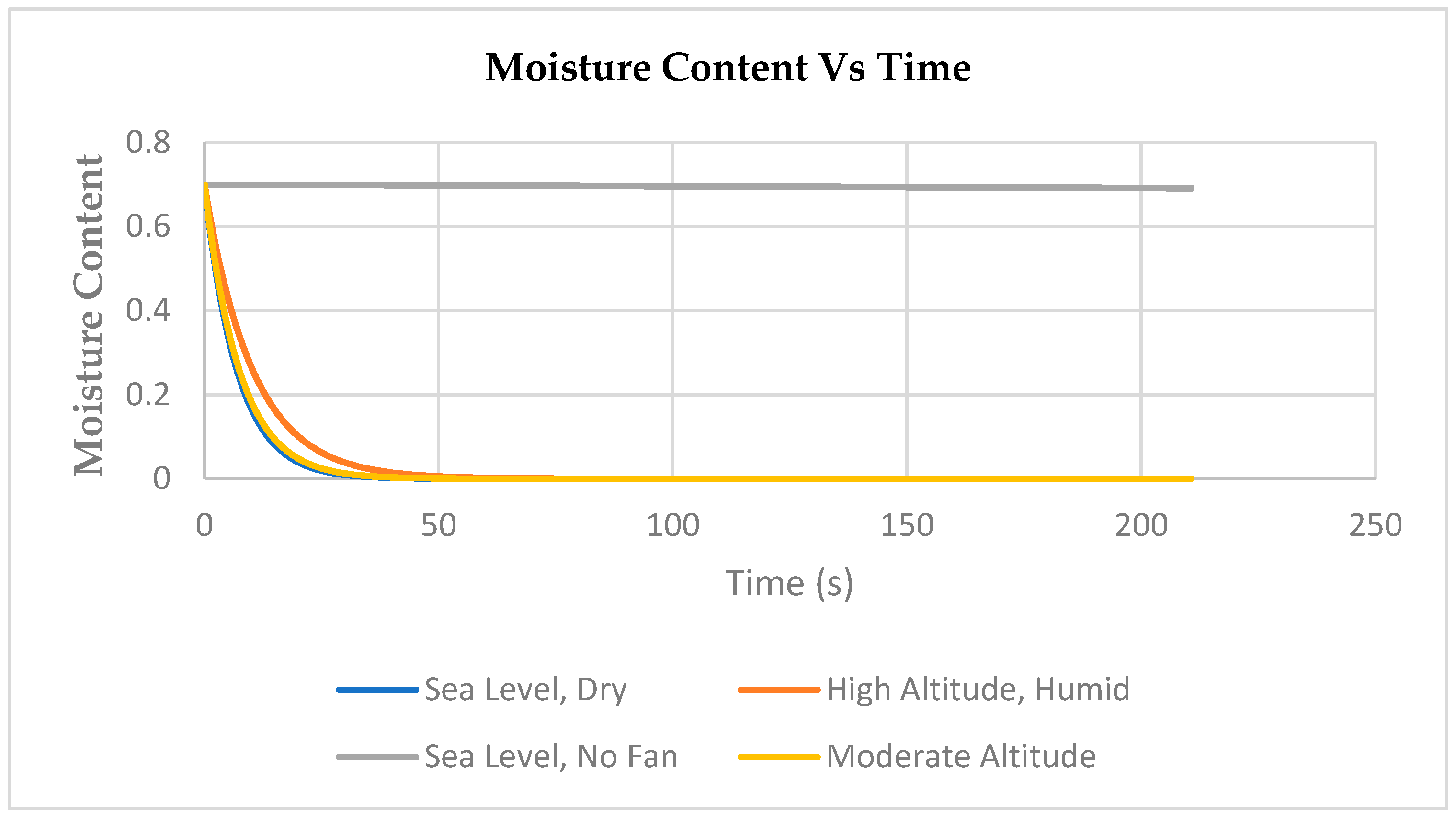

Environmental conditions—particularly ambient temperature, relative humidity, and altitude—significantly affect moisture loss during injera baking and influence final product quality [24,33]. As ambient temperature rises, air holds more water vapor, accelerating moisture evaporation from the batter [40,51]. Moderate heat improves drying efficiency, but excessive temperatures can lead to over-drying, surface cracking, and a loss of the desired soft and spongy texture. Careful thermal management is therefore essential to retain moisture without underbaking [24].Relative humidity influences the evaporation gradient. Low humidity accelerates moisture loss, potentially producing injera that is dry and brittle. In contrast, high humidity slows moisture removal, yielding a softer texture but increasing the risk of stickiness or underbaking unless heat input or baking duration is adjusted (

Table 8). Combined, high temperature and low humidity maximize moisture loss but often degrade softness and structural integrity. Conversely, lower temperatures with high humidity retain moisture but can result in incomplete baking. These findings emphasize the importance of environmentally adaptive baking strategies.

The optimized biogas stove consistently produced injera with high-quality characteristics: uniform thickness (2.0 ± 0.2 mm), porosity (15–17 pores/in²), and excellent flexibility—able to fold 180° without cracking (

Figure 8). These properties align with traditional tests and cultural standards in Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa [53].Its symmetrical, conical burner design ensured even heat distribution, promoting the formation of the characteristic "eyes" (honeycomb structure) and consistent surface browning. Shelf-life tests showed injera maintained freshness and palatability for up to 72 hours, equaling or surpassing traditional biomass-baked injera [54].

At higher altitudes, reduced atmospheric pressure lowers the boiling point of water, extending baking times and slowing moisture evaporation (

Figure 9). This can lead to denser, less spongy injera if stove parameters—such as biogas flow and heat intensity—are not adjusted to compensate for reduced heat transfer efficiency. These findings highlight the critical need to tailor stove operation and baking strategies to local environmental conditions to ensure consistent product quality.

6.8. Economical Feasibility

The economic comparison between biogas and wood-fired stoves reveals significant long-term advantages for biogas adoption. On an annual basis, the biogas stove demonstrates superior cost-efficiency, consuming only 0.244 m³ of fuel per kilogram of injera prepared, resulting in an annual expenditure of approximately $54/ year for an average household. In contrast, traditional wood stoves require 0.535kg of fuel per kilogram of injera, leading to yearly costs of about $0. 79/year. This translates to substantial savings of $25 annually (a 31% reduction in fuel expenses) for households that switch to biogas technology.

While the initial investment of $1,895 for the combined stove and digester system may appear prohibitive, the payback period analysis shows this cost can be recovered through fuel savings alone within seven years [53]. The financial viability improves markedly with supportive policies - when a 50% subsidy is applied, the payback period is effectively halved to just 3.5 years. These economic benefits are further enhanced when considering the additional value of slurry byproducts for agricultural use and the avoided costs associated with health impacts from wood smoke exposure. The long-term economic proposition becomes even more compelling when factoring in the rising costs of firewood due to increasing scarcity and the time savings from reduced fuel collection burdens, particularly for women and children in rural households.

7. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive evaluation of an optimized biogas-powered injera baking stove, highlighting its significant improvements in thermal efficiency, energy savings, emission reductions, and product quality compared to conventional biomass-based systems. The stove achieved a thermal efficiency of 36%, more than double that of traditional three-stone stoves, primarily due to design enhancements including a precision-engineered 45° conical burner and optimized combustion air-fuel ratios.

The system demonstrated exceptional energy savings—reducing energy consumption by approximately 23,160 TJ or 6,430 GWh. annually across 5 million rural households. This translates to a 39% reduction in energy use compared to biomass-based baking systems. Additionally, the stove’s ability to maintain a stable blue flame and uniform heat distribution across the baking surface ensures efficient energy utilization and consistent injera quality.

In terms of environmental benefits, the transition from biomass to biogas cooking could reduce national CO₂ emissions by 3.8 million tonnes per year, contributing directly to Ethiopia’s climate commitments under the Paris Agreement. These reductions are primarily attributed to lower specific fuel consumption and more complete combustion rather than differences in emission factors.

The biogas stove also produced injera that met traditional sensory and cultural quality standards, including optimal porosity, flexibility, softness, and uniform thickness, affirming that technological advancement need not compromise culinary authenticity.

Overall, the findings strongly support the biogas stove as a sustainable and culturally appropriate clean cooking solution. Its deployment at scale holds the potential to simultaneously address critical energy access, environmental, and health challenges in Ethiopia and other regions with similar socio-economic and energy contexts. Future work should explore integration with AI-based optimization systems, localized biogas supply chains, and policy frameworks to enhance scalability and adoption.

Author Contributions

Author 1: - Taha Abdella (PhD Candidate) -Design, experimental Test and article writing. Author 2: - Demiss Alemu (PhD) – Conceptualization of the whole research and validation. Author 3: - Kamil Dino (PhD)- Developed article organization and Writing

Data Availability Statement

Authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interest in carrying out this study

References

- Beyene, A.D.; Koch, S.F. Clean fuel-saving technology adoption in urban Ethiopia. Energy Econ. 2013, 36, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, AH. Design and development of solar parabolic concentrator, closed-loop pressurized hot water for a household baking system – For the case of injera baking in Ethiopia. Heliyon [Internet]. 2024 Jul [cited 2025 Mar 25];10(13):e33733. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier. 2405. [Google Scholar]

- Central Statiscal Agency. Ethiopia Live Stock Population. Federal Democratic of Ethiopia; 2020.

- Tucho, G.T.; Moll, H.C.; Uiterkamp, A.J.M.S.; Nonhebel, S. Problems with Biogas Implementation in Developing Countries from the Perspective of Labor Requirements. Energies 2016, 9, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaineb, D.; Morgan, L.; Salma, T.; Simon, L.; Yann, L.; Lega, B.F.; Habib, H.; Ahmed, K. A Review of Operational Conditions of the Agroforestry Residues Biomethanization for Bioenergy Production Through Solid-State Anaerobic Digestion (SS-AD). Energies 2025, 18, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, D.; Li, L.; Appleby, G. A Review of Renewable Energy Technologies in Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTPs). Energies 2024, 17, 6084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.; Clifford, M.; Selby, G. Towards fair, just and equitable energy ecosystems through smart monitoring of household-scale biogas plants in Kenya. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddafa, T.; Melka, Y.; Sime, G. Cost-benefit Analysis and Financial Viability of Household Biogas Plant Investment in South Ethiopia. Sustain. Energy Res. 2023, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benti, N.E.; Gurmesa, G.S.; Argaw, T.; Aneseyee, A.B.; Gunta, S.; Kassahun, G.B.; Aga, G.S.; Asfaw, A.A. The current status, challenges and prospects of using biomass energy in Ethiopia. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2021, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarika, J. Global Potential of Biogas. World Biogas Association; 2019.

- Nega, D.T.; Yirgu, B.M.; Demissie, S.W. Improved biogas ‘Injera’ bakery stove design, assemble and its baking pan floor temperature distribution test. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2021, 61, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, A.A.; Nydal, O.J.; Amibe, D.A. Performance Investigation of Solar Powered Injera Baking Oven for Indoor Cooking. ISES Solar World Congress 2011. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, GermanyDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–11.

- Petro, L.M.; Machunda, R.; Tumbo, S.; Kivevele, T. Theoretical and Experimental Performance Analysis of a Novel Domestic Biogas Burner. J. Energy 2020, 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailis, R.; Berrueta, V.; Chengappa, C.; Dutta, K.; Edwards, R.; Masera, O.; Still, D.; Smith, K.R. Performance testing for monitoring improved biomass stove interventions: experiences of the Household Energy and Health Project. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2007, 11, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofiane Mazeghrane. A manometric method for monitoring biogas production in anaerobic bioreactors. In 2015.

- Neela, S.; Fanta, S.W. Injera (An Ethnic, Traditional Staple Food of Ethiopia): A review on Traditional Practice to Scientific Developments. J. Ethn. Foods 2020, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddafa, T.; Melka, Y.; Sime, G. Cost-benefit Analysis and Financial Viability of Household Biogas Plant Investment in South Ethiopia. Sustain. Energy Res. 2023, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- engel YA, Ghajar AJ. Heat and mass transfer: fundamentals & applications. 5th edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2015. 968 p.

- Incropera FP, DeWitt DP, Bergman TL, Lavine AS, editors. Fundamentals of heat and mass transfer. 6. ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2007. 997 p.

- Jones, R.; Diehl, J.C.; Simons, L.; Verwaal, M. The development of an energy efficient electric Mitad for baking injeras in Ethiopia. 2017 International Conference on the Domestic Use of Energy (DUE). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, South AfricaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 75–82.

- Adem, K.D.; Ambie, D.A.; Arnavat, M.P.; Henriksen, U.B.; Ahrenfeldt, J.; Thomsen, T.P. First injera baking biomass gasifier stove to reduce indoor air pollution, and fuel use. AIMS Energy 2019, 7, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisay, A.K.; Kebede, M.S.; Chanie, A.M. Development of an enhanced electrical injera baking pan (Ethiopian Traditional mitad) using steel powder additives and gypsum insulation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz W, AOAC International, editors. Official methods of analysis of AOAC International. 18. ed., current through rev. 1, 2006. Gaithersburg, Md: AOAC International; 2006. 2400 p.

- Getenet, G. Heat Transfer Anysis During the process of injera baking by Finite element method. [Addis Ababa]: Addis Ababa institute of technology; 2011.

- Singh RP, Heldman DR. Introduction to food engineering. 4th ed. Amsterdam: Acad. Press, Elsevier; 2009. 841 p. (Food science and technology, international series).

- Hailu AD, Hassen AA. Experimental Investigation and Loss Quantification in Injera Baking Process. 2018;1(1).

- Abdella, T.; Alemu, D.; Dino, K. Design and experimental investigation of an LPG injera baking stove for sustainable energy use in Ethiopia. Discov. Energy 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafere, AT. Experimental Investigation on Performance Characterstics and Efficiency of Electric Injera Baking [Thesis]. [Addis Ababa]: Addis Ababa University School of Graduate Studies Institute of Technology Energy Technology Department; 2011.

- Abdella, T. Experimental Investigation of Biogas Injera Baking Stove Using Circular Ring Pipe Burner [Internet]. In Review; 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 22]. Available from: https://www.researchsquare. 3558. [Google Scholar]

- Hinojosa, J.; Cabanillas, R.; Alvarez, G.; Estrada, C. Nusselt number for the natural convection and surface thermal radiation in a square tilted open cavity. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2005, 32, 1184–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herwig, H. What Exactly is the Nusselt Number in Convective Heat Transfer Problems and are There Alternatives? Entropy 2016, 18, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoa, D.O.; Oloo, T.; Kasaine, S. The Efficiency of the Energy Saving Stoves in Amboseli Ecosystem-Analysis of Time, Energy and Carbon Emissions Savings. Open J. Energy Effic. 2017, 06, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede D, Kiflu A. Design of Biogas Stove for Injera Baking Application. 2014;1(1).

- Itodo, I.; Agyo, G.; Yusuf, P. Performance evaluation of a biogas stove for cooking in Nigeria. J. Energy South. Afr. 2007, 18, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameel MK, Mustafa MA, Ahmed HS, Mohammed AJ, Ghazy H, Shakir MN, et al. Biogas: Production, properties, applications, economic and challenges: A review. Results in Chemistry [Internet]. 2024 Jan [cited 2025 Mar 27];7:101549. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier. 2211.

- Novak Pintarič Z, Kravanja Z. The Importance of using Discounted Cash Flow Methodology in Techno-economic Analyses of Energy and Chemical Production Plants. J sustain dev energy water environ syst [Internet]. 2017 Jun [cited 2025 Apr 22];5(2):163–76. Available from: http://www.sdewes.org/jsdewes/pid5. 0140.

- Wang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wu, G.; Zhan, X. A critical review on dry anaerobic digestion of organic waste: Characteristics, operational conditions, and improvement strategies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa Yosef. Assessing Enviromental Benifts of Mirt Stove. Addis Ababa University School of Graduate Studies, Enviromental Science Program; 2007.

- Dresen, E.; DeVries, B.; Herold, M.; Verchot, L.; Müller, R. Fuelwood Savings and Carbon Emission Reductions by the Use of Improved Cooking Stoves in an Afromontane Forest, Ethiopia. Land 2014, 3, 1137–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banooni, S.; Hosseinalipour, S.M.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Taheran, E.; Bahiraei, M.; Taherkhani, P. Baking of Flat Bread in an Impingement Oven: An Experimental Study of Heat Transfer and Quality Aspects. Dry. Technol. 2008, 26, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, G.A.; Melka, Y.; Sime, G.; Yirga, F.; Marie, M.; Haile, M. Biogas technology in fuelwood saving and carbon emission reduction in southern Ethiopia. Heliyon 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaye, A.; Amaha, S.; Gufi, Y.; Tesfamariam, B.; Worku, A.; Abrha, H. Fuelwood use and carbon emission reduction of improved biomass cookstoves: evidence from kitchen performance tests in Tigray, Ethiopia. Energy, Sustain. Soc. 2022, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfay, A.H.; Tsegay, K.; Kahsay, M.B.; Hailu, M.H.; Adaramola, M.S. Performance comparison of three prototype biomass stoves with traditional and Mirt stoves for baking Injera. Energy, Sustain. Soc. 2024, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wae-Hayee, M.; Yeranee, K.; Suksuwan, W.; Nuntadusit, C. Effect of burner-to-plate distance on heat transfer rate in a domestic stove using LPG. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouki Ghenai, Isam Janajreh. Combustion of Renewable Biogas Fuels. JEPE [Internet]. 2015 Oct 28 [cited 2025 Apr 13];9(10). Available from: http://www.davidpublisher.org/index.php/Home/Article/index?id=19269.

- Pinho, C.; Delgado, J.M.; Ferreira, V.; Pilão, R. Influence of Burner Geometry on Flame Characteristics of Propane-Air Mixture: Experimental and Numerical Studies. Defect Diffus. Forum 2008, 273-276, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yu, Z. Design and Decomposition Analysis of Mixing Zone Structures on Flame Dynamics for a Swirl Burner. Energies 2020, 13, 6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito K, Ihara H, Tatsuta S, Fujita O. Quantitative characterization of flame color and its application. Introduction of CIE 1931 standard colorimetric system. TransJSME, B [Internet]. 1990 [cited 2025 Mar 26];56(531):3508–13. Available from: http://www.jstage.jst.go. 1979.

- Begum, A.; Habiba, U.; Aziz, M. ; Mazumder Design of an Improved Traditional Baking Oven and evaluation of Baking Performance. J. Bangladesh Agric. Univ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H Tesfay A, H Hailu M, A Gebrerufael F, S Adaramola M. Implementation and Status of Biogas Technology in Ethiopia- Case of Tigray Region. mejs [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Mar 25];12(2):257–73. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index. 9 May 2069.

- Dagnaw, H.B.; Woldegiorgis, A.Z.; Kebede, K.A. Influence of nitrogen fertilizer rate and variety on tef [Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) Trotter] nutritional composition and sensory quality of a staple bread (Injera). PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0295491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilhate Leta Chala. Energy efficient injera baking with biogas in Ethiopia. German: HOHENHEIM; 2019.

- Mohammed AS, Atnaw SM, Desta M. The Biogas Technology Development in Ethiopia: The Status, and the Role of Private Sectors, Academic Institutions, and Research Centers. In: Sulaiman SA, editor. Energy and Environment in the Tropics [Internet]. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2023 [cited 2025 Mar 26]. p. 227–43. (Lecture Notes in Energy; vol. 92). Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-19-6688-0_14.

- Addis Ababa University; Ashagrie, Z. ; Abate, D. Improvement of injera shelf life through the use of chemical preservatives. Afr. J. Food, Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2012, 12, 6409–6423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).