Introduction:

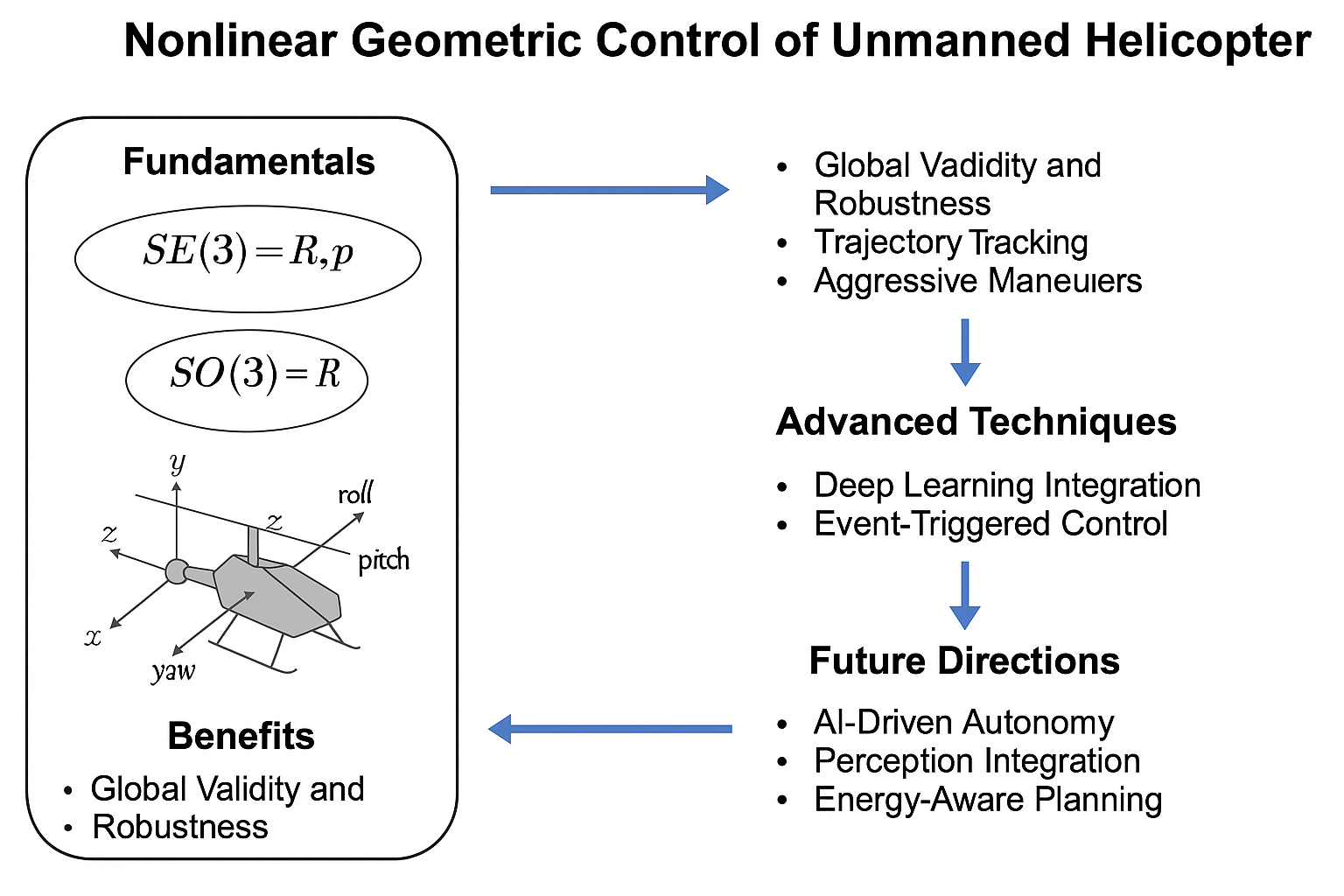

The control of unmanned helicopters has been a challenging problem in modern aerospace engineering due to their inherently nonlinear, underactuated, and highly coupled dynamics. Traditional linear control approaches often rely on local linearization around equilibrium points, which restricts their validity to small operating regions and prevents effective handling of large manoeuvres or external disturbances. To overcome these challenges, nonlinear geometric control has emerged as a mathematically rigorous and practically robust framework. Unlike conventional methods, geometric control is formulated directly on the configuration space of the system, often modelled as the special Euclidean group SE(3), which naturally represents both the position and orientation of a rigid body in three-dimensional space. By designing control laws on manifolds, this approach avoids issues associated with minimal angle representations such as Euler angle singularities, thereby ensuring global validity and smooth performance during aggressive or complex trajectories [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

Geometric control enables unmanned helicopters to achieve precise trajectory tracking, even under conditions of significant external disturbances or modelling uncertainties. For instance, Cai and Xian [

1] developed a nonlinear geometric control framework for helicopter-based payload transportation via diverse cables, demonstrating how the manifold-based approach can maintain stability while handling complex interactions between the helicopter and the suspended load. Similarly, Gu, Ma, and Xian [

2] advanced this field by incorporating convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for system identification and precise tracking control of nano-helicopters, highlighting the potential for integrating data-driven methods into the geometric control paradigm.

One of the defining features of geometric control is its ability to manage highly dynamic manoeuvres. Unlike linearized controllers, which may fail when the system undergoes fast rotations or large translational motions, geometric control inherently accounts for nonlinearities and the global topology of motion. This advantage was demonstrated in the work of Antal et al. [

4], where geometric methods enabled miniature quadcopters to perform aggressive manoeuvres such as backflipping. These findings underline the practical benefits of geometric control for applications where agility and precision are critical.

Another important research direction lies in the development of event-driven geometric controllers. In resource-constrained environments, such as small-scale unmanned helicopters with limited onboard computational and communication capacity, continuous control updates can be inefficient. To address this, Ma, Gu, and Xian [

3] introduced event-triggered geometric control strategies that reduce computation while maintaining robustness and stability. This line of work shows that geometric control can be adapted to meet the practical demands of energy efficiency and real-time feasibility in embedded systems.

Furthermore, geometric control has been successfully applied to cooperative aerial tasks, payload transportation, and aerial manipulation. Goodarzi, Lee, and Lee [

5] pioneered the concept of geometric nonlinear PID control for quadrotors, providing a systematic framework to regulate motion on SE(3) with rigorous stability guarantees. Their contribution formed the basis for subsequent studies extending geometric control to multi-agent coordination and aerial robots with external payloads.

In a summery, nonlinear geometric control provides a unifying framework that bridges theoretical rigor with practical implementation in unmanned helicopters. By avoiding singularities, ensuring robustness, and enabling high-performance manoeuvres, this approach has become indispensable for advancing the state of the art in aerial robotics. The integration of modern machine learning techniques, such as CNNs, and event-triggered mechanisms further broadens its applicability to intelligent and resource-aware aerial systems. This review synthesizes the key contributions in the field, highlights challenges, and identifies promising future directions for the development of robust, adaptive, and autonomous unmanned helicopters.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section II explains the fundamental concepts of geometric control and highlights how it differs from conventional control approaches. Section III discusses the benefits and practical advantages of nonlinear geometric control for unmanned helicopters, focusing on robustness, trajectory tracking, and performance in dynamic environments. Section IV presents advanced techniques and applications, including hierarchical control architectures, integration with deep learning, payload transportation, and event-triggered control mechanisms. Section V presents the discussion on few recent geometric control strategies’ applied on quadrotor or UAV. Section VI concludes the paper by summarizing key insights, highlighting open research challenges, and suggesting future directions for developing autonomous, intelligent, and resource-efficient unmanned helicopter systems.

II. Fundamentals of Geometric Control

Nonlinear geometric control is fundamentally different from classical linear or approximate nonlinear control methods, as it is formulated directly on the global configuration space of the system. For unmanned helicopters, which are rigid bodies operating in three-dimensional space, this configuration space is naturally represented by the special Euclidean group, SE(3). SE(3) captures both the translational position and rotational orientation of the helicopter without the limitations of minimal coordinate parameterizations. By working on this manifold, geometric control eliminates the issues of singularities and discontinuities that arise in conventional representations such as Euler angles, thereby providing a mathematically elegant and globally valid framework for designing controllers [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

In geometric control, the helicopter’s state is considered as a point on a manifold, where its orientation is often represented using rotation matrices belonging to the special orthogonal group SO(3). Unlike Euler angles, which suffer from gimbal lock and singularities at specific orientations, rotation matrices and unit quaternions ensure smooth and consistent representation across the entire motion space. This manifold-based formulation provides a natural way to encode the system dynamics and design control laws that respect the global structure of rigid body motion. For instance, the dynamics of the helicopter on SE(3) can be decomposed into translational dynamics evolving in Euclidean space and rotational dynamics evolving on SO(3). This separation allows controllers to be designed with a deeper geometric understanding of the vehicle’s behavior.

Unlike traditional controllers that rely on approximations or coordinate-based linearization, geometric control is implemented directly on the nonlinear system dynamics. By exploiting the intrinsic properties of the manifold, the control laws preserve the geometry of motion and provide rigorous guarantees of stability. For example, attitude tracking can be achieved by defining error functions on SO(3) that measure the difference between desired and actual orientations in a coordinate-free manner. Such formulations not only simplify the control design but also lead to controllers that are more robust to modelling uncertainties and external disturbances. This direct design philosophy ensures that the system’s nonlinearities are not treated as “errors” to be compensated but as natural features of the dynamics to be leveraged for better performance.

One of the main motivations for geometric control lies in its ability to completely bypass singularities inherent in classical orientation representations. Euler angles, while intuitive, introduce singularities when the pitch angle approaches ±90°, leading to mathematical instability in the control system. Geometric control avoids these pitfalls by using globally valid representations like rotation matrices and quaternions. This ensures that unmanned helicopters can perform aggressive manoeuvres, such as flips, rolls, and coordinated payload swings, without the risk of control degradation or failure due to singularities. Such robustness is critical for advanced aerial missions, including high-speed navigation in cluttered environments, aerobatic manoeuvres, and cooperative tasks involving multiple UAVs.

The geometric approach has been validated in several experimental and theoretical works. Goodarzi, Lee, and Lee [

6] introduced geometric nonlinear PID control on SE(3), demonstrating the global stability and robustness of this method. Kober and Peters [

7] applied reinforcement learning in conjunction with geometric frameworks for autonomous helicopter flight, highlighting the synergy between data-driven techniques and rigorous geometric formulations. Subsequent works [

8,

9,

10,

11] have shown that geometric control provides a unified foundation for diverse UAV applications, from payload transportation to aerial manipulation and cooperative flight.

The mathematical modeling of a quadrotor helicopter is a prerequisite for the design of effective nonlinear geometric controllers. A quadrotor is an underactuated system with six degrees of freedom (DOF), three translational and three rotational but only four independent control inputs corresponding to the thrusts generated by the four rotors. This under actuation makes the control problem non-trivial, requiring a rigorous framework that can handle nonlinearities, coupling, and external disturbances.

Quadrotor Dynamics on SE(3): The configuration of a quadrotor is naturally described on the special Euclidean group SE(3), which consists of the position x ∈ R

3 and orientation R ∈ SO(3) of the vehicle. The equations of motion are given as:

where m is the mass, g is gravitational acceleration, f is the total thrust, e

3 = [0,0,1]ᵀ, R ∈ SO(3) is the rotation matrix, Ω ∈ R

3 is the angular velocity, J is the inertia matrix, M ∈ R

3 is the control moment, and Ω^ is the skew-symmetric matrix of Ω.

Geometric Control on SE(3): The goal is to track a desired trajectory (x_d(t), R_d(t)) by designing feedback laws directly on the manifold SE(3). The position and velocity errors are defined as:

The desired thrust is computed as:

The attitude error on SO(3) is defined as:

The control moment is given by:

Stability Analysis: A candidate Lyapunov function for stability proof is:

where the attitude error function is

Its derivative along system trajectories satisfies:

for positive constants c

1, c

2, c

3, c

4, which guarantees exponential convergence of errors.

III. Benefits of Geometric Control for Unmanned Helicopters

Geometric control offers several distinct advantages over classical linear and approximate nonlinear control methods when applied to unmanned helicopters. These benefits arise from its intrinsic ability to capture the nonlinearities of rigid-body motion, provide globally valid formulations, and maintain stability under highly dynamic conditions. The three primary benefits are robustness, precise trajectory tracking, and enhanced performance, which together make geometric control an indispensable tool for advanced aerial robotics [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Unmanned helicopters typically operate in complex and uncertain environments, where external disturbances such as wind gusts, payload swings, or sensor noise can significantly degrade performance. Conventional linearized controllers are highly sensitive to modeling errors and may lose stability outside their narrow operating regions. In contrast, geometric control addresses the nonlinearities of helicopter dynamics directly on SE(3), leading to inherently more robust performance. By defining error dynamics in a coordinate-free manner, geometric controllers maintain stability and performance even when confronted with unmodeled dynamics or parameter variations. Experimental studies have demonstrated that helicopters controlled under geometric frameworks can recover from unexpected disturbances and maintain their intended flight paths with minimal deviation [

12,

13]. This robustness is particularly important for missions involving outdoor environments, urban navigation, or cooperative operations where unpredictability is unavoidable.

A critical requirement for unmanned helicopters is the ability to track complex reference trajectories with high accuracy. Geometric control is particularly well-suited for this task because it avoids singularities and discontinuities in orientation representation. For example, Antal et al. [

14] demonstrated nonlinear geometric control for backflipping miniature quadcopters, a manoeuvre that is difficult to achieve reliably with conventional methods due to rapid orientation changes. Similarly, Cai and Xian [

15] showed that geometric control enables UAVs to transport payloads via suspended cables while maintaining precise trajectory tracking, even in the presence of coupling effects between the UAV and the load. Furthermore, Kumar and Xian [

16] extended these methods to UAVs carrying swinging loads, ensuring both the vehicle and payload follow desired trajectories. These examples highlight that geometric control can achieve precise tracking not only for nominal flight paths but also for highly aggressive and dynamic manoeuvres.

Beyond robustness and tracking accuracy, geometric control improves overall system performance by providing faster response times, effective damping of oscillations, and reliable operation during high-speed manoeuvres. One of the common challenges in helicopter operations is the oscillatory motion induced by suspended payloads or rapid attitude changes. Geometric controllers, by exploiting manifold-based formulations, inherently stabilize such oscillations and ensure smoother flight trajectories. For example, Mellinger and Kumar [

17] demonstrated that geometric methods effectively dampen payload swings during transportation, thereby increasing mission safety and efficiency. Subsequent studies [

18,

19,

20] confirmed that geometric control not only improves accuracy but also reduces control energy requirements, making it more efficient in long-duration or resource-constrained missions. This enhanced performance makes geometric control highly attractive for applications such as aerial inspection, search and rescue, and precision delivery, where reliability and agility are equally critical.

IV. Advanced Techniques and Applications of Geometric Control

While the fundamentals of geometric control provide a solid foundation for robust and globally valid UAV control, recent research has explored advanced techniques and novel applications that extend its capabilities. These enhancements address practical challenges such as scalability, computational efficiency, and adaptability to uncertain and dynamic environments. Four key directions are hierarchical control architectures, integration with deep learning, payload transportation, and event-driven control mechanisms [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

Geometric control has often been implemented in a hierarchical framework, where different control loops are designed for rotational and translational dynamics. In such schemes, the inner loop typically stabilizes the rotational dynamics on SO(3), while the outer loop manages translational motion, path tracking, or payload dynamics. This separation simplifies the control design and ensures fast response for attitude regulation, which is critical for aerial vehicles with underactuated dynamics. For example, Cai and Xian [

21] demonstrated a hierarchical geometric control design for helicopters transporting payloads via suspended cables, where the inner attitude controller stabilized the UAV orientation, and the outer loop coordinated the payload swing suppression. Similarly, Kumar and Xian [

22] extended hierarchical geometric designs to UAV systems under coupled load dynamics, highlighting the scalability of such approaches to cooperative and multi-agent tasks.

Despite the robustness of geometric controllers, they remain sensitive to unmodeled dynamics, actuator faults, or environmental variations. To address this, researchers have begun integrating deep learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), into geometric control frameworks. CNNs provide powerful system identification capabilities by learning complex, nonlinear mappings between inputs and outputs from flight data. Gu, Ma, and Xian [

23] presented CNN-enhanced geometric control for nano-helicopters, achieving precise tracking despite significant modelling uncertainties. Such hybrid approaches combine the rigor of geometric control with the adaptability of data-driven learning, paving the way for intelligent UAVs capable of autonomously compensating for structural changes, payload variations, or unforeseen disturbances.

One of the most compelling applications of geometric control is in aerial load transportation, where helicopters are tasked with carrying suspended payloads or interacting physically with the environment. Conventional controllers often struggle with payload swing dynamics, which can destabilize the vehicle. Geometric control, by exploiting manifold-based error formulations, ensures that both the UAV and payload follow the desired trajectory with minimized oscillation. Cai and Xian [

24] demonstrated this capability for helicopters transporting payloads with diverse cables, while Kumar and Xian [

25] applied similar approaches to UAVs with nonlinear swinging dynamics. These studies highlight the practicality of geometric control in applications such as disaster relief, precision delivery, and construction, where UAVs must safely and efficiently carry heavy or delicate loads.

A major challenge in small-scale unmanned helicopters is the limited availability of onboard computation and communication resources. Continuous-time controllers require frequent updates, which may not be feasible in resource-constrained settings. Event-triggered geometric control addresses this by updating control inputs only when necessary, based on predefined triggering conditions. Ma, Gu, and Xian [

26] proposed an event-driven robust geometric controller for nano-helicopters, significantly reducing communication while preserving stability and robustness. Later works [

27] confirmed that event-triggered mechanisms can maintain geometric control performance with fewer updates, making this approach particularly valuable for UAV swarms, long-duration missions, and real-time embedded platforms [

28,

29,

30].

V. Discussion

In

Table 1, we show and compare some different versions of geometric control of quadrotor or UAV. The fundamental geometric formulations on SE(3) ([

31,

43]) establish globally valid, singularity-free controllers for quadrotor trajectory tracking. They avoid Euler angle singularities and provide a clean theoretical framework. Finite-time variants ([

33]) enhance transient response but may introduce chattering issues. These works form the baseline architecture for most subsequent geometric control research. Disturbance attenuation is addressed via H∞ design ([

38]), uncertainty disturbance estimators ([

41]), and interval observers ([

42]) to handle unknown inputs.

Model-free or disturbance-compensated designs ([

35,

40]) reduce dependence on exact modeling, which is critical in outdoor flights subject to wind gusts. These methods improve practical applicability, though often at the cost of increased tuning complexity or conservatism. Geometric control extends to tethered formations ([

32]), cooperative payload transport ([

36]), and formation stability in swarms ([

49]). These works show the versatility of geometric methods beyond single vehicles. However, they frequently assume idealized sensing/communication, and robustness to real-world latency or packet loss remains an open challenge. Cable-suspended payload transport is a particularly challenging domain. Geometric control with swing dynamics mitigation ([

37]) and vision–inertial adaptive feedback ([

50]) demonstrate practical relevance for aerial logistics. While effective in reducing oscillations, these approaches face challenges in strong disturbances (e.g., wind) and sensor pipeline delays. Expanding geometric control to unaligned thrust systems ([

44]) and bicopters ([

45]) shows adaptability to non-standard platforms. These works highlight geometric control’s structural flexibility, though validation is typically limited and aerodynamic simplifications may restrict scalability. Trajectory generation using geometric frameworks ([

46,

48]) integrates constraints such as energy, safety, and aggressive maneuvers. Approximate optimal controllers ([

47]) bridge control and planning by reducing computational complexity. While not always full controllers, these frameworks are key enablers for high-level autonomy in long-range or acrobatic missions.

VI. Conclusion and Future Directions

Nonlinear geometric control has emerged as a powerful paradigm for addressing the challenges of unmanned helicopter flight. By formulating control laws directly on manifolds, this approach avoids singularities and achieves precise tracking even under uncertainties and external disturbances. The review demonstrates how geometric control enhances robustness, ensures stability during aggressive maneuvers, and enables efficient payload transport. Furthermore, recent advancements in deep learning integration and event-driven mechanisms highlight the potential for intelligent and resource-efficient UAV operations. Despite these advances, future research must address open challenges such as scalability to multi-agent systems, adaptation under dynamic environments, and seamless fusion with perception-driven autonomy. This comprehensive review provides a foundation for researchers and practitioners to develop next-generation UAV systems leveraging geometric control principles.

References

- J. Cai and B. Xian, “Nonlinear Geometric Control Design for a Helicopter UAV Transportation System via Diverse Cables,” Conference Paper, Jul. 2023. [Online]. Available: ResearchGate.

- Gu, X.; Xian, B.; Liu, M.; Ma, A. CNN based precise nonlinear tracking control for a nano unmanned helicopter: Theory and implementation. ISA Trans. 2025, 164, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, A.; Gu, X.; Xian, B. Event-Driven Robust Geometric Control for a Nano Unmanned Helicopter. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 14272–14283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antal, P.; Péni, T.; Tóth, R. Nonlinear Control Method for Backflipping with Miniature Quadcopters. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Goodarzi, D. Lee, T. Lee, “Geometric Nonlinear PID Control of a Quadrotor UAV on SE(3),” in Proceedings of the 2013 European Control Conference (ECC), Zürich, Switzerland, July 17–19, 2013, pp. 3583–3588. (Also available via arXiv).

- F. Goodarzi, D. F. Goodarzi, D. Lee, and T. Lee, “Geometric Nonlinear PID Control of a Quadrotor UAV on SE(3),” in Proc. European Control Conference (ECC), Zürich, Switzerland, Jul. 2013, pp.3845–3850.

- J. Kober and J. Peters, “Autonomous Helicopter Flight Using Reinforcement Learning,” in Adaptive Learning Methods for Nonlinear System Control, Springer, 2011, pp. 147–176.

- Ma, A.; Gu, X.; Xian, B. Event-Driven Robust Geometric Control for a Nano Unmanned Helicopter. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 14272–14283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. A. Ryll, D. Bicego, and A. Franchi, “A Multi-Rotor UAV Modified Geometric Attitude Controller,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, May 2014, pp.3432–3437.

- Madgwick, S.O.H.; Harrison, A.J.L.; Vaidyanathan, R. Estimation of IMU and MARG orientation using a gradient descent algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics, Zurich, Switzerland, 29 June–1 July 2011, (Also discussed in Keeping a Good Attitude: A Quaternion-Based Orientation Filter, NIH Tech Report, 2015). [CrossRef]

- D. Mellinger and V. Kumar, “Mathematical Modeling and Control of a Quadrotor with a Payload,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Karlsruhe, Germany, May 2013, pp. 3264–3269.

- Gu, X.; Xian, B.; Liu, M.; Ma, A. CNN based precise nonlinear tracking control for a nano unmanned helicopter: Theory and implementation. ISA Trans. 2025, 164, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Cai and B. Xian, “Nonlinear geometric control design for a helicopter UAV transportation system via diverse cables,” in Proc. IEEE Conf. Decision and Control (CDC), Cancún, Mexico, Dec. 2022.

- Antal, P.; Péni, T.; Tóth, R. Nonlinear Control Method for Backflipping with Miniature Quadcopters. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar and, B. Xian, “Nonlinear control strategies for a UAV carrying a load with swing dynamics,”ISATrans.,vol.129,pp89–101,2022.

- J. Cai and B. Xian, “Nonlinear geometric control design for a helicopter UAV transportation system via diverse cables,” in Proc. IEEE Conf. Decision and Control (CDC), Cancún, Mexico, Dec. 2022.

- Kumar and, B. Xian, “Nonlinear control strategies for a UAV carrying a load with swing dynamics,” ISA Trans., vol. 129, pp. 89–101, 2022.

- J. Cai and B. Xian, “Nonlinear geometric control design for a helicopter UAV transportation system via diverse cables,” in Proc. IEEE Conf. Decision and Control (CDC), Cancún, Mexico, Dec. 2022.

- Ma, A.; Gu, X.; Xian, B. Event-Driven Robust Geometric Control for a Nano Unmanned Helicopter. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 14272–14283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antal, P.; Péni, T.; Tóth, R. Nonlinear Control Method for Backflipping with Miniature Quadcopters. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Cai and B. Xian, “Nonlinear geometric control design for a helicopter UAV transportation system via diverse cables,” in Proc. IEEE Conf. Decision and Control (CDC), Cancún, Mexico,Dec.2022.

- Kumar and, B. Xian, “Nonlinear control strategies for a UAV carrying a load with swing dynamics,” ISA Transactions, vol. 129, pp. 89–101, 2022.

- Gu, X.; Xian, B.; Liu, M.; Ma, A. CNN based precise nonlinear tracking control for a nano unmanned helicopter: Theory and implementation. ISA Trans. 2025, 164, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Cai and B. Xian, “Nonlinear geometric control design for a helicopter UAV transportation system via diverse cables,” in Proc. IEEE Conf. Decision and Control (CDC), Cancún, Mexico, Dec. 2022.

- Kumar and, B. Xian, “Nonlinear control strategies for a UAV carrying a load with swing dynamics,” ISA Transactions, vol. 129, pp. 89–101, 2022.

- Gu, X.; Xian, B.; Liu, M.; Ma, A. CNN based precise nonlinear tracking control for a nano unmanned helicopter: Theory and implementation. ISA Trans. 2025, 164, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.; Gu, X.; Xian, B. Event-Driven Robust Geometric Control for a Nano Unmanned Helicopter. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 14272–14283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Zeng, X. Y. Zeng, X. Yan, and J. Zhou, “Active disturbance rejection geometric control of quadrotor under arbitrary initial attitudes,” Control Engineering Practice, 2025.

- Lei, B.; Liu, B.; Wang, C. Robust Geometric Control for a Quadrotor UAV with Extended Kalman Filter Estimation. Actuators 2024, 13, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Zeng, X. Y. Zeng, X. Yan, and J. Zhou, “Geometric control of a quadrotor UAV on SO(3) with actuator constraints: a cascade nonlinear constrained control approach,” [preprint / conference version], 2025.

- M. Sharma and S. Singla. Geometric Tracking Control of a Quadrotor on SE(3) using Left Tracking Error. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kosarnovsky, B.; Arogeti, S. Geometric and constrained control for a string of tethered drones. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2020, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Kar, I. Geometric control of quadrotor with finite-time convergence and improved transients. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2021, 52, 1396–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Zhan et al., “Geometric-based prescribed performance control for unmanned aerial manipulator,” ISA Transactions (Elsevier), 2022.

- Zhao, C.; Burlion, L. Geometric Model Free Trajectory Tracking Control on SE(3). IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.; Colombo, L. Geometric Control of Two Quadrotors Carrying a Rigid Rod with Elastic Cables. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2022, 32, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yuan, X.; Zhu, B. Geometric control for trajectory-tracking of a quadrotor UAV with suspended load. IET Control. Theory Appl. 2022, 16, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Aslam and I. Kar, “H∞ inverse optimal attitude tracking on SE(3),” Int. J. Control (Taylor & Francis), 2023.

- Niu, H.; Xie, A.; Zhu, S.; Hu, Y.; Yan, X.; Wang, X. Anti-disturbance Trajectory Tracking Control for a Quadrotor UAV with Input Constraints⋆. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2023, 56, 9300–9305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Wang et al., “Geometric prescribed-time control of quadrotors with AESO,” Int. J. Robust and Nonlinear Control (Wiley), 2024.

- Y. Hu et al., “UDE-based geometry trajectory tracking for quadrotor,” Asian Journal of Control (Wiley), 2024.

- K. Yan et al., “Interval Observer-based Robust Trajectory Tracking Control for QUAV,” Int. Journal of Control, Automation and Systems (Springer), 2024.

- J. Madeiras et al., “Trajectory tracking of a quadrotor via full-state feedback without inner–outer loop,” Aerospace Science and Technology (Elsevier), 2024.

- S. Zhong et al., “Geometric Tracking Control of a Quadrotor with Tilted Propellers,” Proc. IEEE AIM, 2024.

- V. R. Vundela et al., “Nonlinear Attitude and Altitude Tracking for Bicopter,” International Journal of Aerospace Engineering (Wiley/Hindawi), 2024.

- J. Pinto et al., “Planning Aggressive Drone Manoeuvres: A Geometric Perspective,” Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems (Springer), 2025.

- Yao, J.; Nekoo, S.R.; Xin, M. Approximate optimal control design for quadrotors: A computationally fast solution. Optim. Control. Appl. Methods 2023, 45, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Akshya et al., “Geometric Optimisation of UAV Trajectories,” Journal of King Saud University – Computer and Information Sciences (Elsevier), 2025.

- J. Li et al., “Formation flight approach and experiment for multiple quadrotors,” Int. J. Robust and Nonlinear Control (Wiley), 2025.

- Wang, S.; Chen, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y. Adaptive trajectory tracking of UAV with a cable-suspended load using vision-inertial-based estimation. Automatica 2023, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Overview comparison among recent research work for geometric control approach.

Table 1.

Overview comparison among recent research work for geometric control approach.

| Reference |

Focus Area / Characteristics |

Strengths / Advantages |

Limitations / Disadvantages |

Applications |

| [31,33,43] |

Core SE(3)-based trajectory tracking; finite-time and unified control formulations |

Global, singularity-free design; improved transient response; simplified architecture |

Chattering near manifold; less modular than cascade designs |

General quadrotor trajectory tracking |

| [34,35,38,40,41,42] |

Robust geometric control under uncertainties and disturbances |

Disturbance attenuation; reduced modeling effort; robustness to wind |

Complex parameter tuning; conservatism in observer bounds |

Outdoor flights, wind/gust environments, safety-critical missions |

| [32,36,49] |

Geometric cooperative control for multi-agent and tethered systems |

Explicit constraint handling; cooperative payload transport; formation stability |

Assumes ideal communication/sensing; limited disturbance validation |

Tethered inspection, swarm flight, cooperative logistics |

| [37,50] |

Payload swing dynamics with geometric tracking and adaptive feedback |

Attenuates oscillations; robust to payload variation; vision–inertial integration |

Performance limited in strong winds; sensor latency issues |

Cable-suspended load transport, aerial logistics |

| [44,45] |

Control for non-standard morphologies (unaligned thrust, bicopters) |

Handles tilted-prop configurations; extends to bicopters |

Limited experimental scope; simplified aerodynamics |

Nonstandard aerial vehicles, minimal-rotor platforms |

| [46,47,48,49,50] |

Geometric trajectory generation, planning, and optimization |

Covers aggressive maneuvers, multi-objective optimization, energy minimization |

Primarily planning; relies on assumptions of controller coupling |

Acrobatics, long-range and energy-aware missions |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).