Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Block-coupled solution procedure – Instead of using a segregated solution procedure, in which displacement increment components and the pressure increment are solved separately, a block-coupled system of linear algebraic equations (representing the discretised momentum and pressure increment equations) is solved for displacement and pressure increments simultaneously. This leads to a more robust and efficient solution process, as there is no need to apply user-defined under-relaxation to the displacement and pressure increments. The proposed block-coupled solution procedure is based on the procedure proposed by Professor M. Darwish and collaborators [9,10] for the solution of laminar incompressible flow problems on collocated unstructured FV grids. Later, a similar algorithm was implemented [11,12] in the OpenFOAM framework [13], which serves as the starting point for the implementation of an algorithm for solving incompressible elastic/hyperelastic solid deformations in this work.

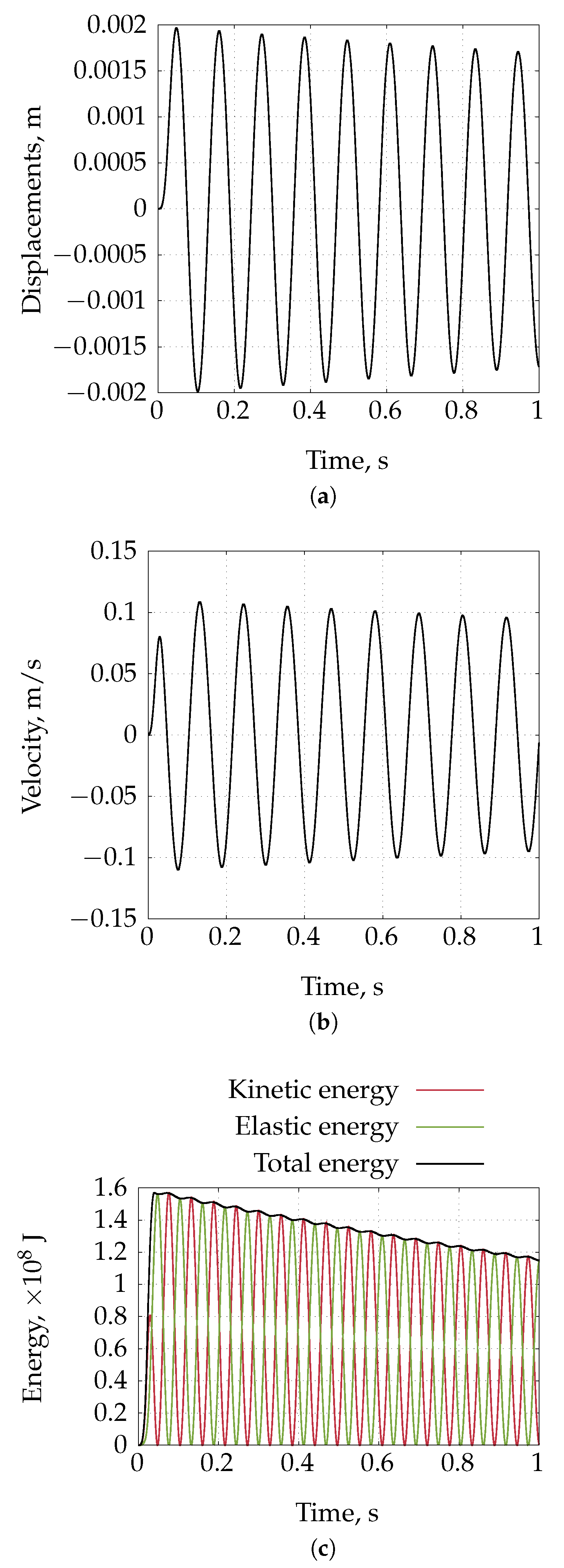

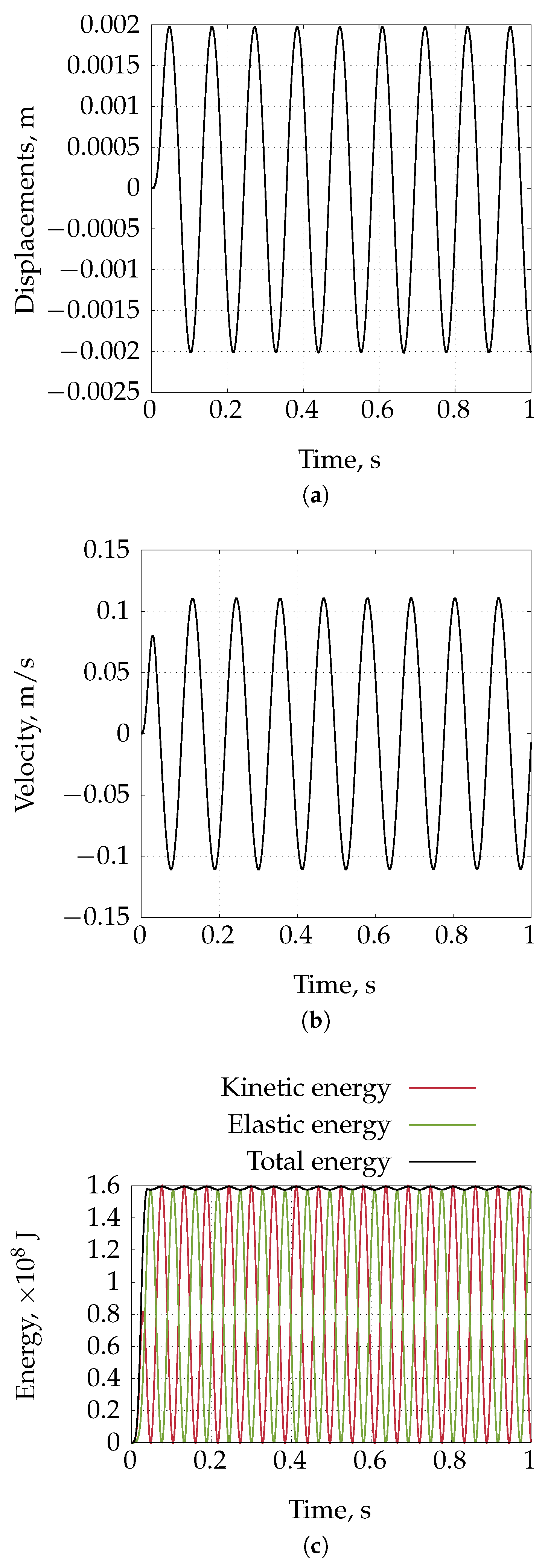

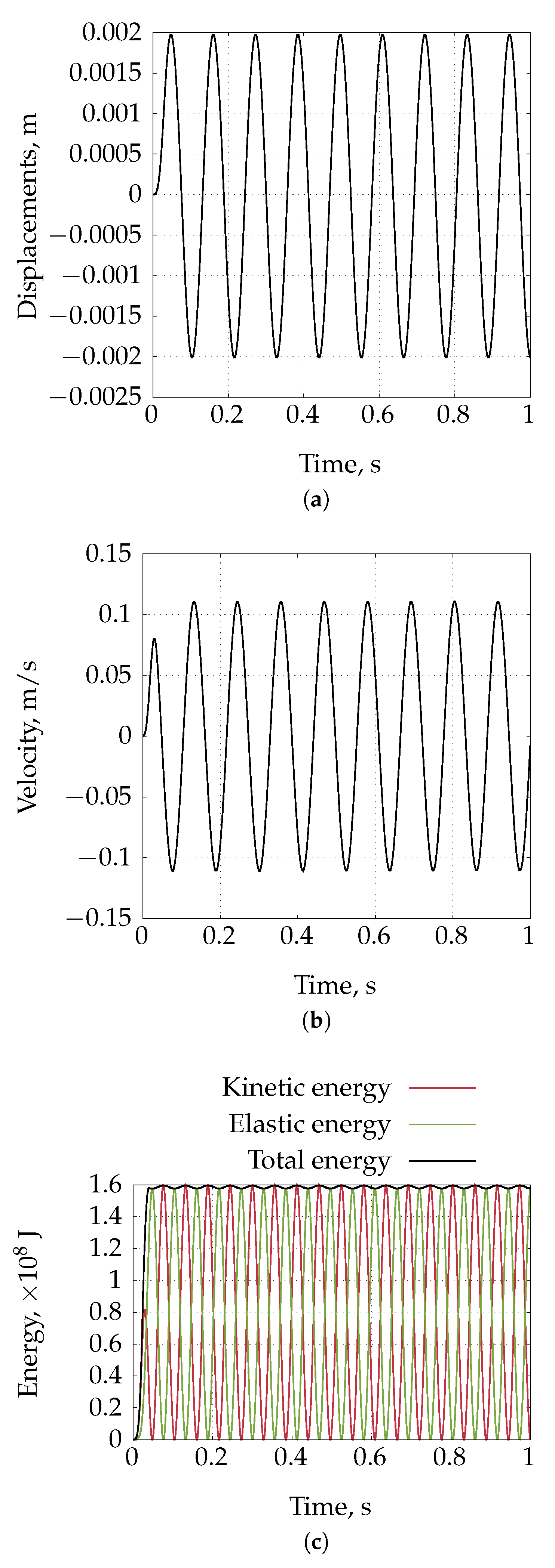

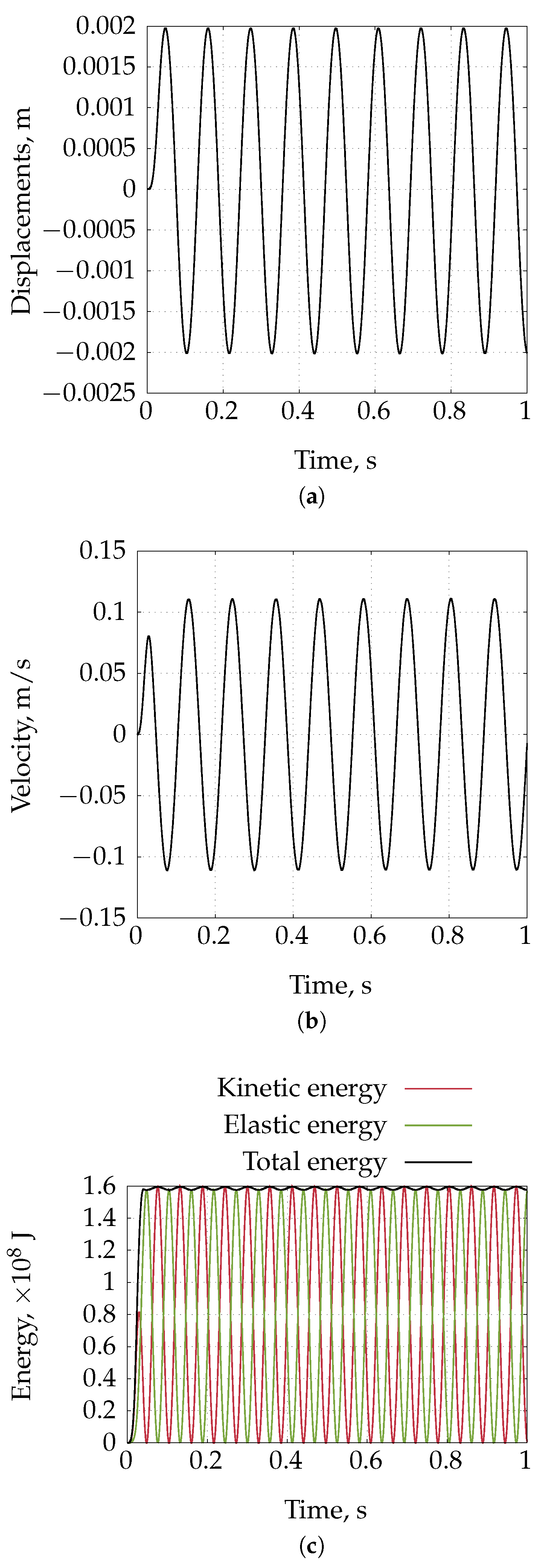

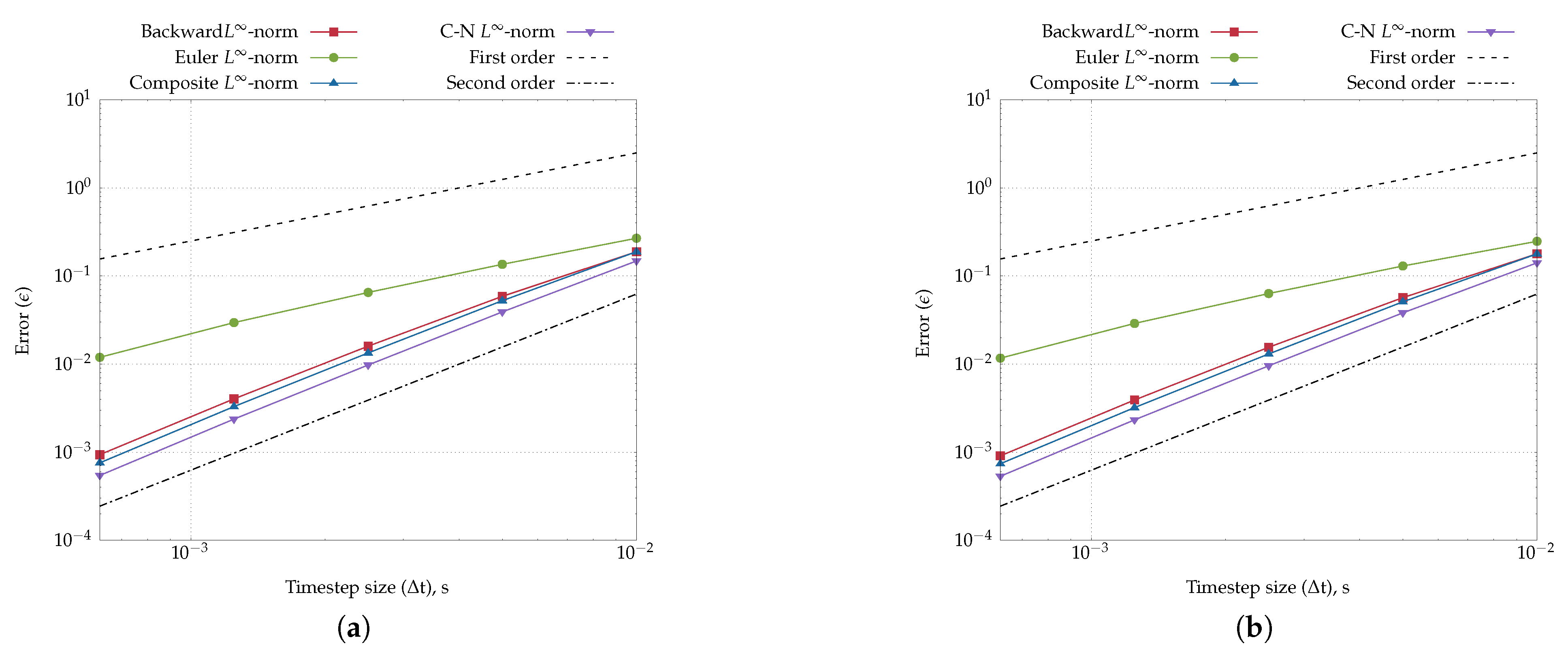

- Temporal discretisation - Emphasis is placed on the temporal accuracy of the model, as the ultimate objective is its application to fluid–structure interaction simulations in vascular flows. Four commonly used temporal discretisation schemes are implemented and tested, each incorporating a temporally consistent Rhie–Chow interpolation [14].

- Improved treatment of traction boundaries - Along the portions of the discretized spatial domain boundary where traction is specified, the displacement increment is calculated using the cell-face normal component obtained from the solution of the continuity (pressure increment) equation, while the remaining components are reconstructed using the selected constitutive equation. This approach provides substantially higher accuracy at the traction boundaries compared to the second-order extrapolation used in [4].

- Extended material applicability – The proposed FV solver is applicable to both linear elastic bodies and nonlinear hyperelastic materials described by arbitrary constitutive equations, with emphasis on constitutive relations used for modeling arterial walls and heart tissue (for exampe, Holzapfel-Gasser-Ogden (HGO) model [15] and Guccione model [16]).

2. Mathematical Model

2.1. Constitutive Equations

2.2. Resulting Set of Equations for Incompressible Solid

2.3. Initial and Boundary Conditions

3. Numerical Model

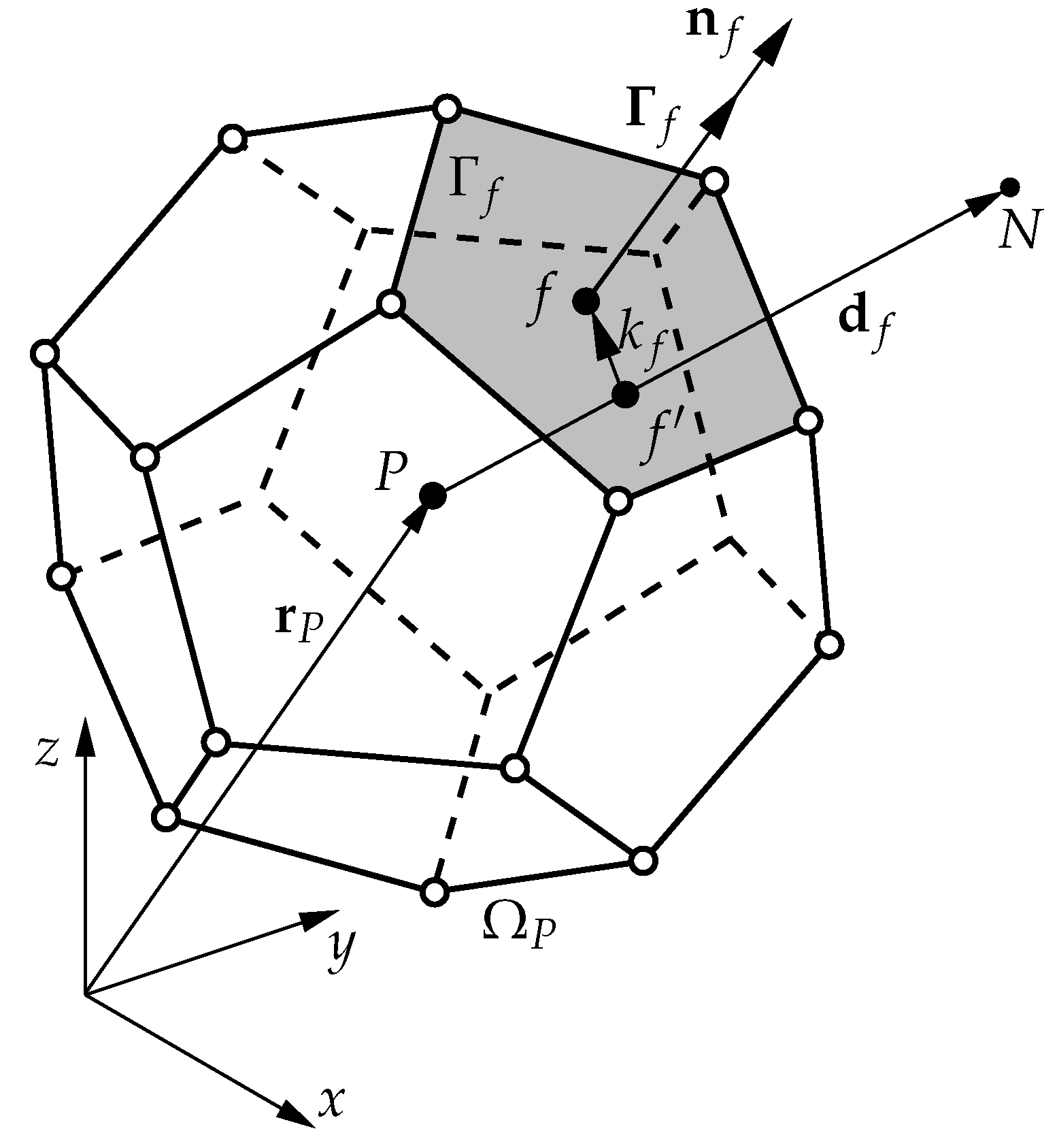

3.1. Solution Domain Discretization

3.2. Governing Equations Discretization

3.2.1. Momentum Equation Discretisation

- Euler scheme

- Crank-Nicolson scheme

- backward scheme

- composite scheme [21]: a simplified version is implemented here, where the Crank-Nicolson and backward scheme are applied alternately.

3.2.2. Discretised Pressure Equation

3.2.3. Calculation of Gradients

3.2.4. Mesh Vertices Displacement

3.2.5. Initial and Boundary Condition

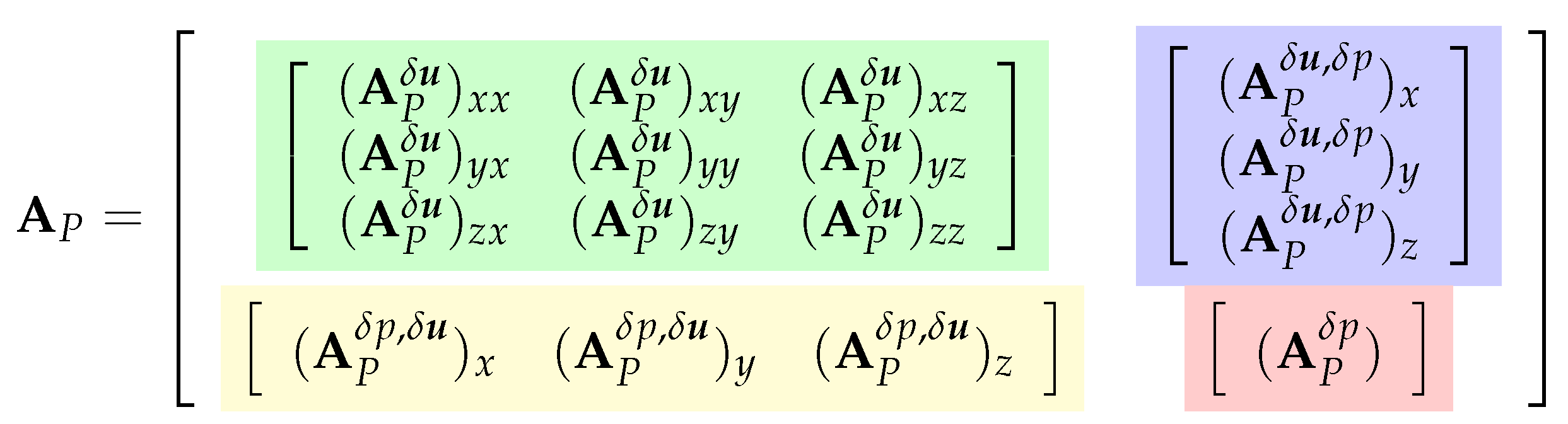

3.2.6. Final Block-Coupled System of Linear Algebraic Equations

3.3. Solution Procedure

| Algorithm 1 Block coupled solution procedure. |

|

4. Results

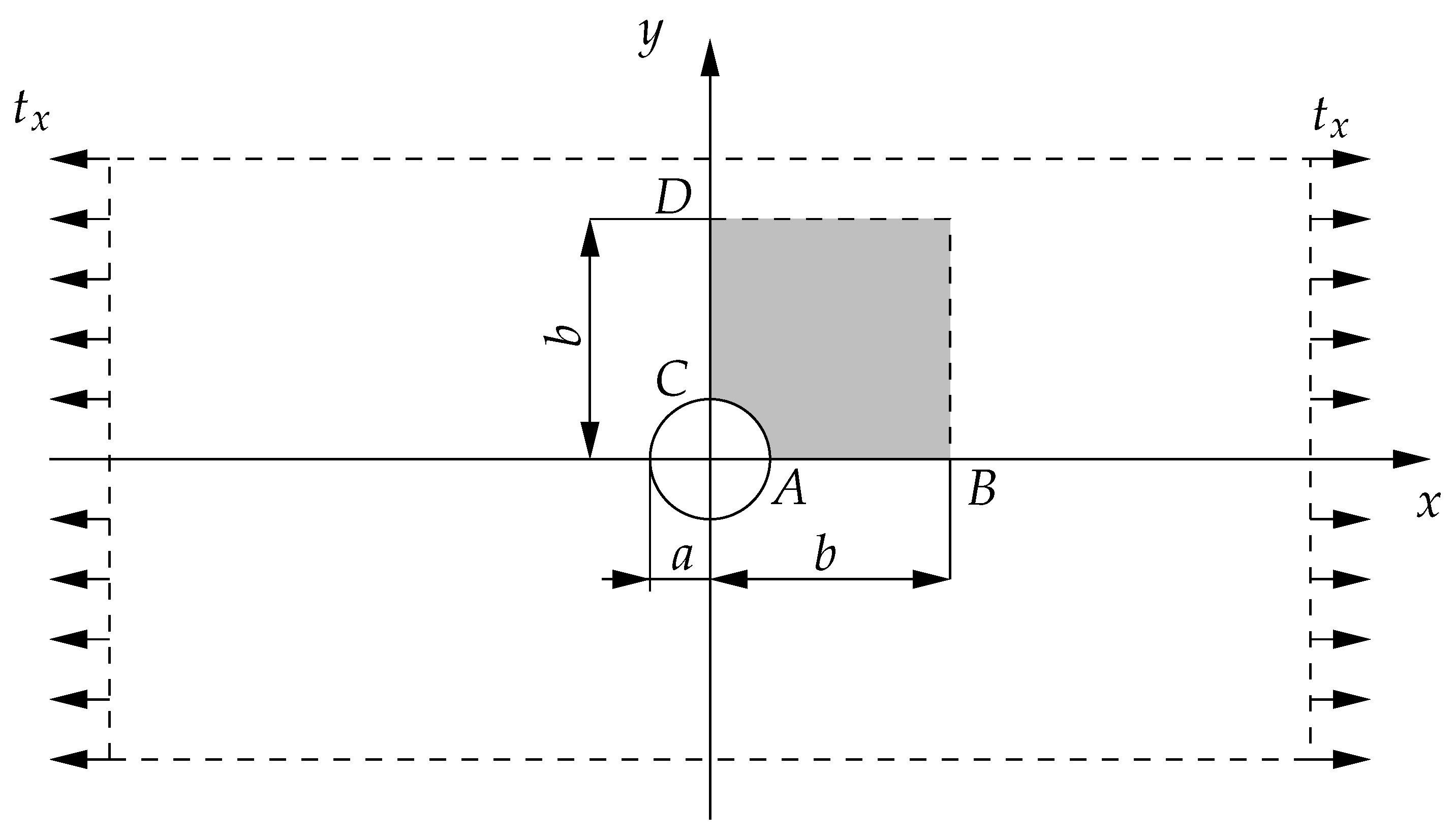

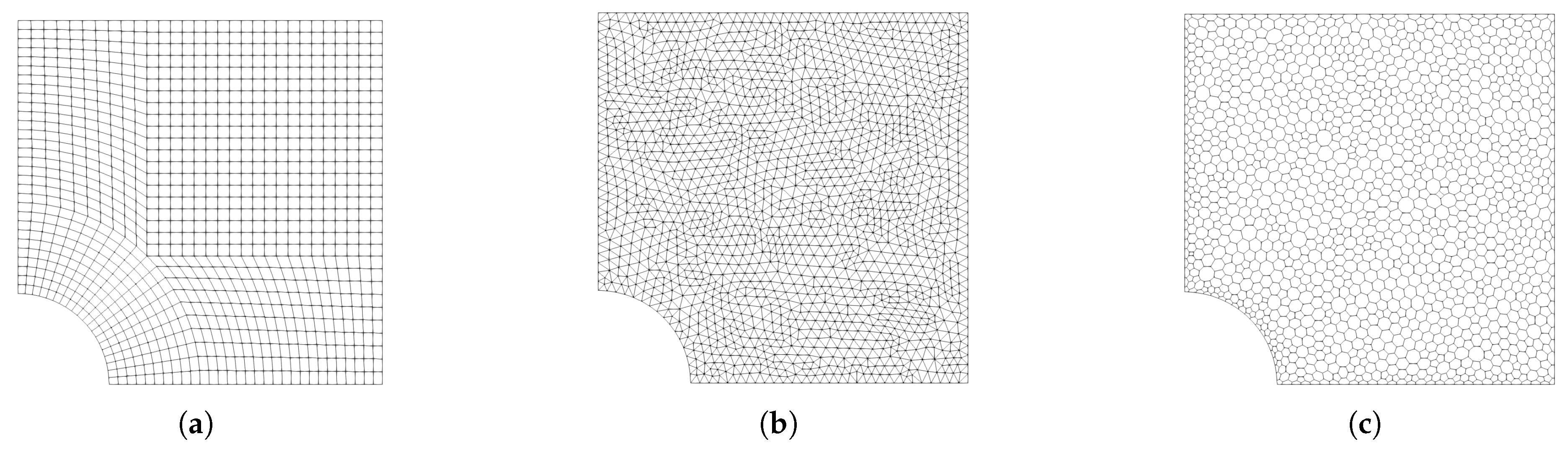

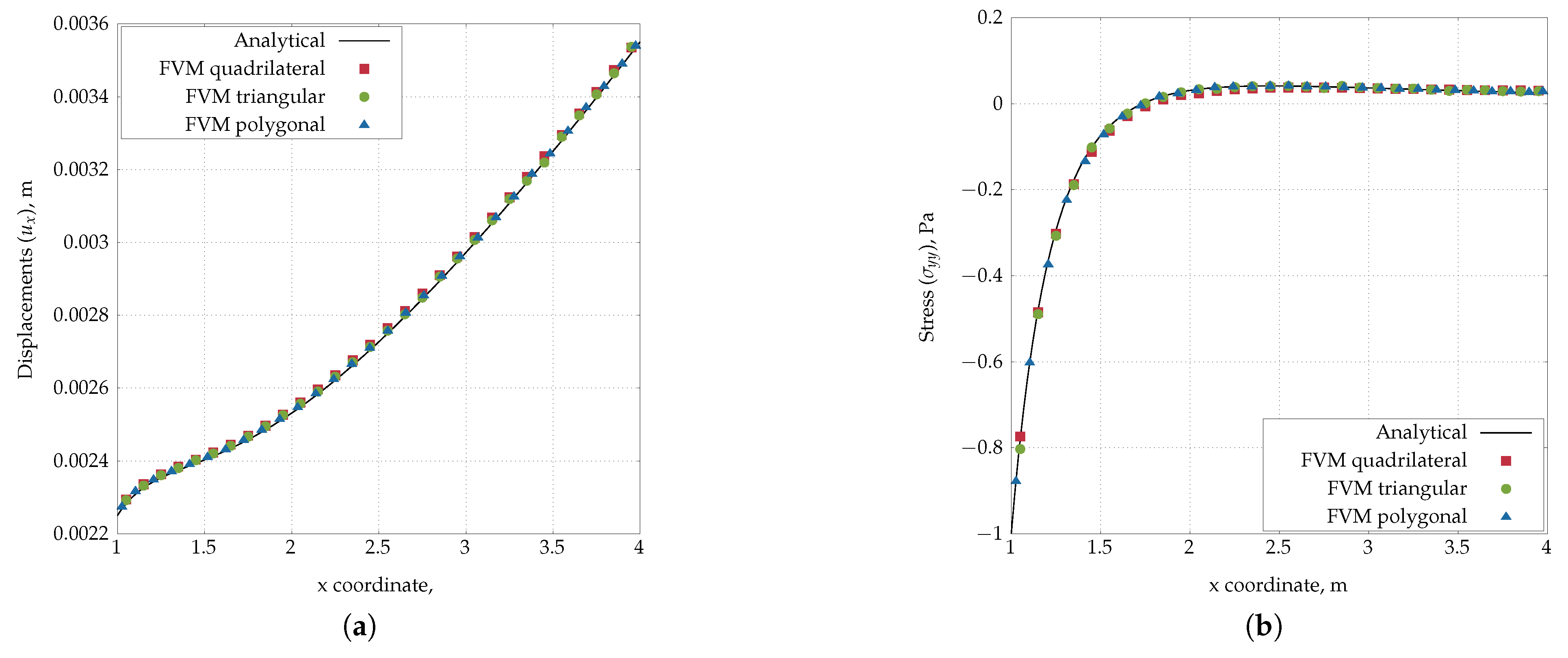

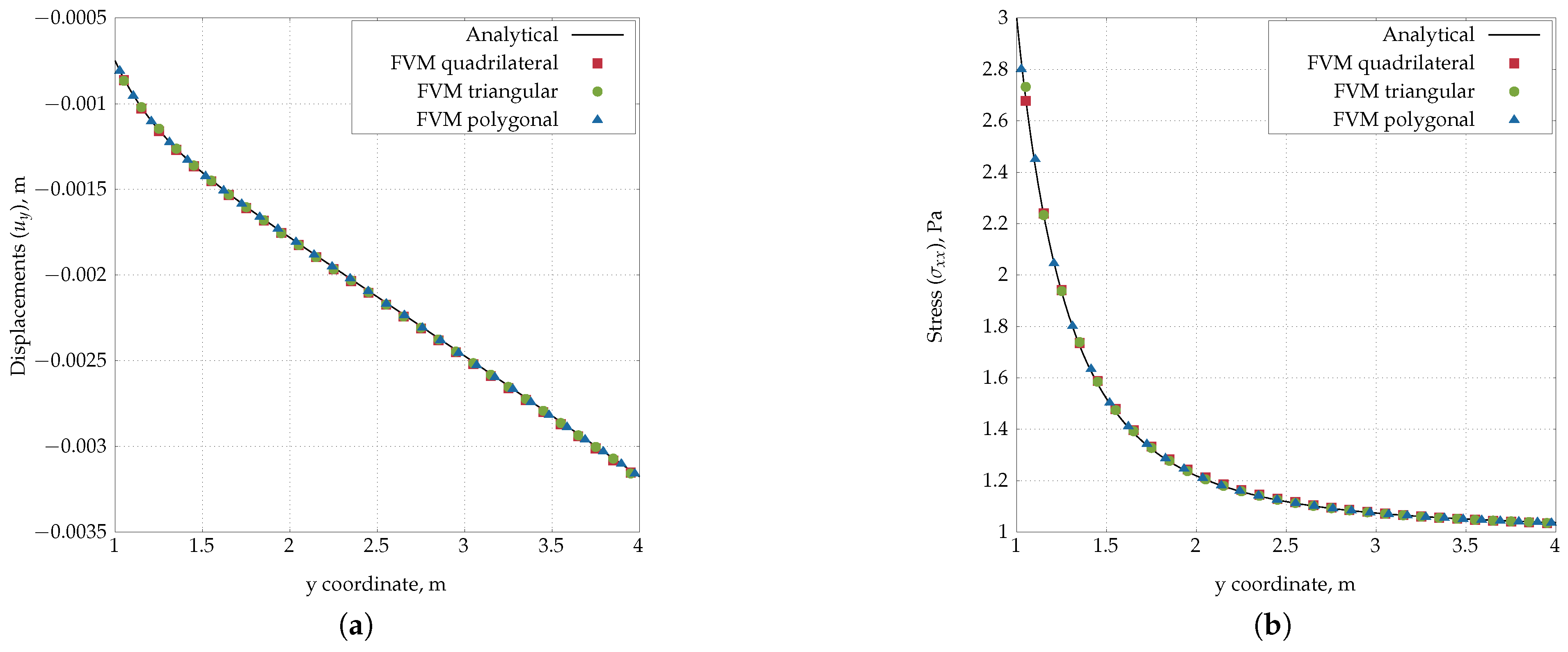

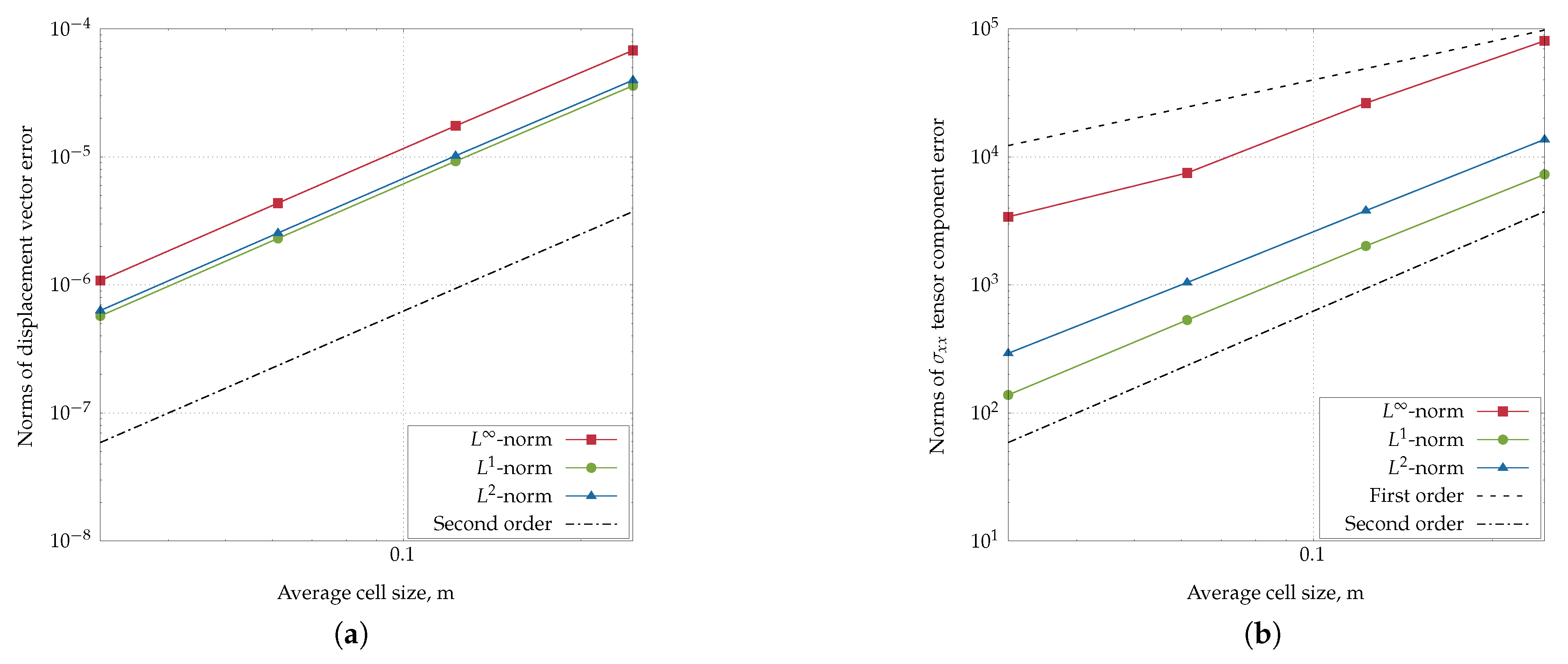

4.1. Infinite Plate with a Circular Hole Subjected to Uniform Tension

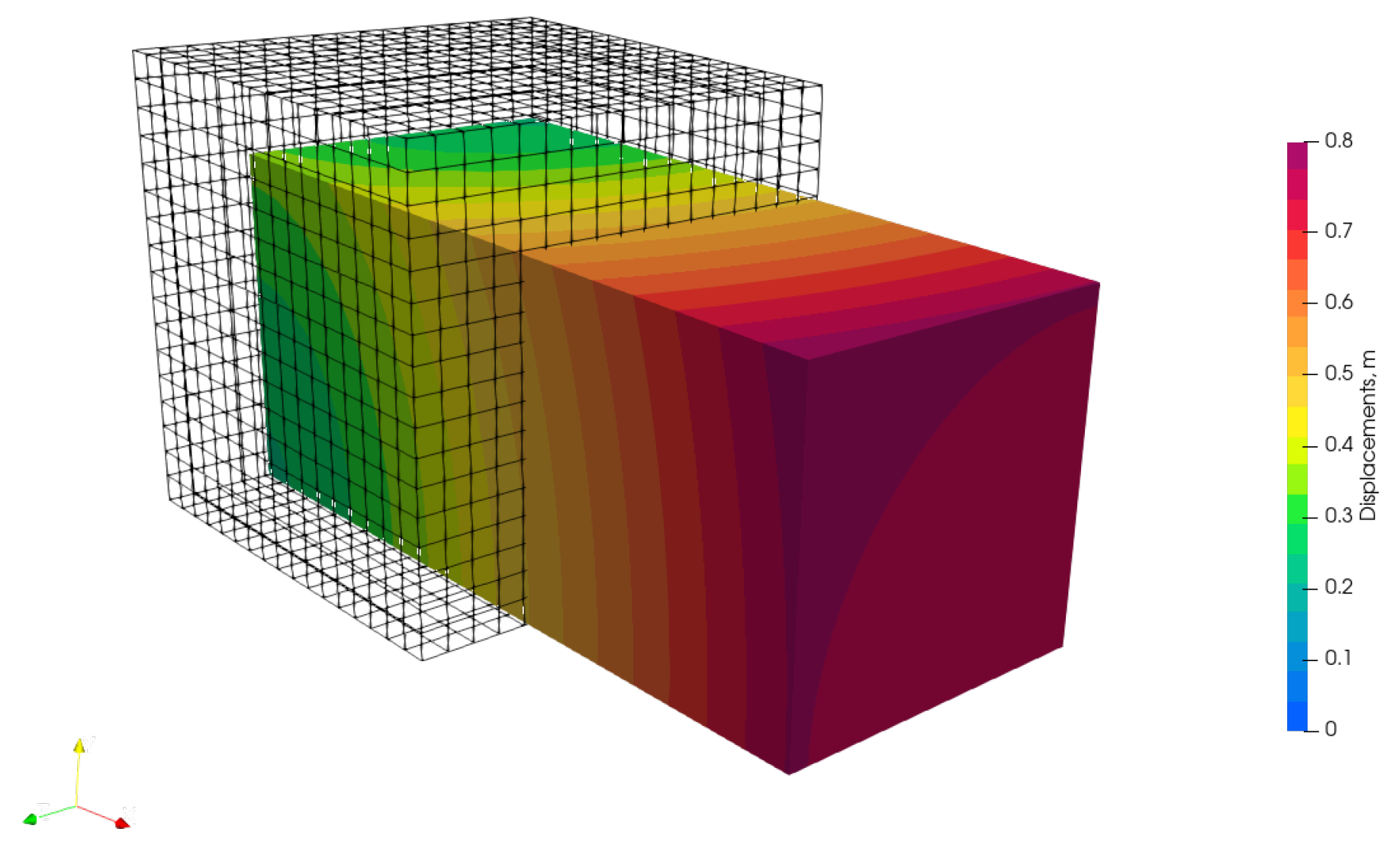

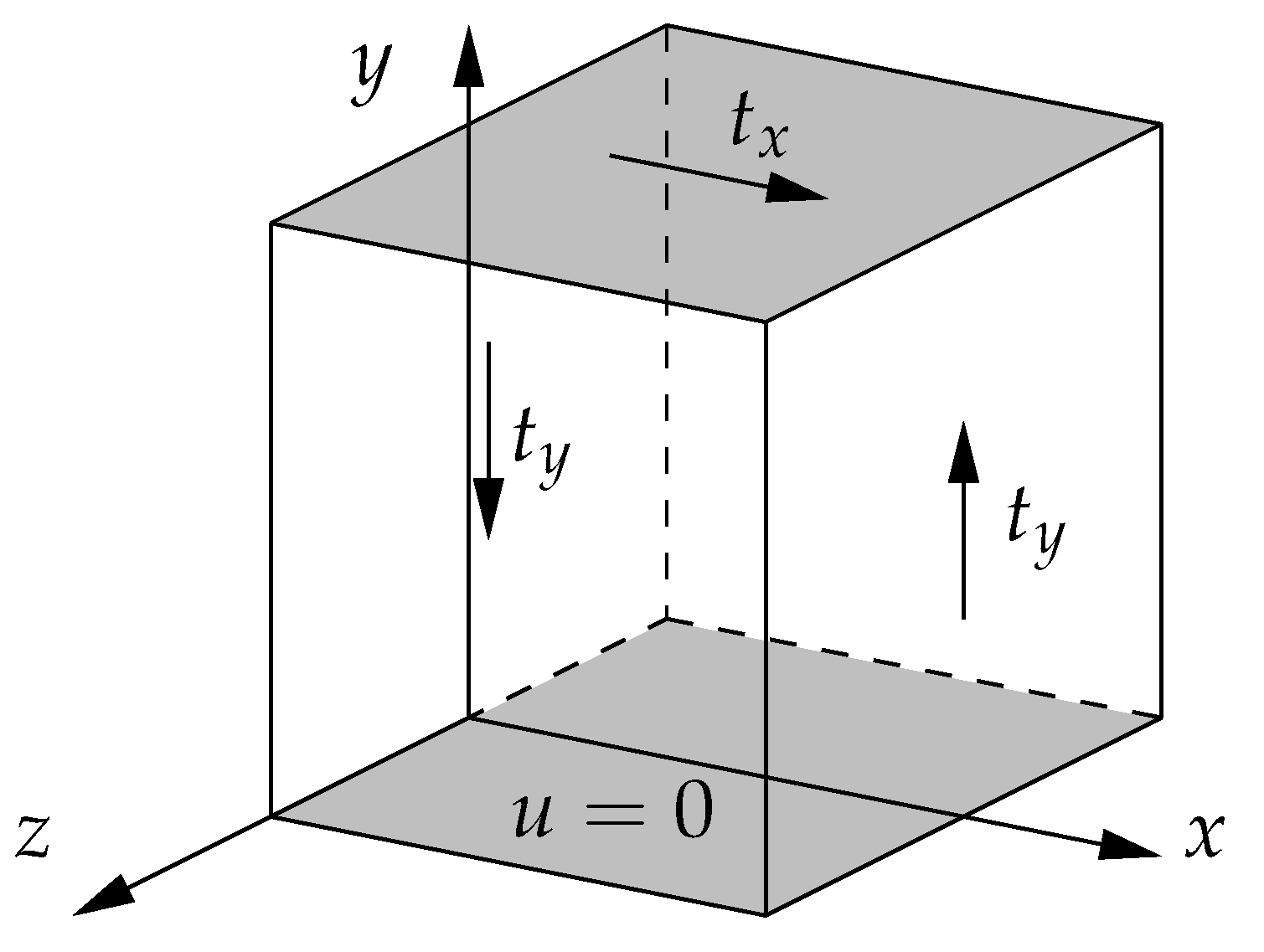

4.2. Uniaxial Extension and Simple Shear Tests

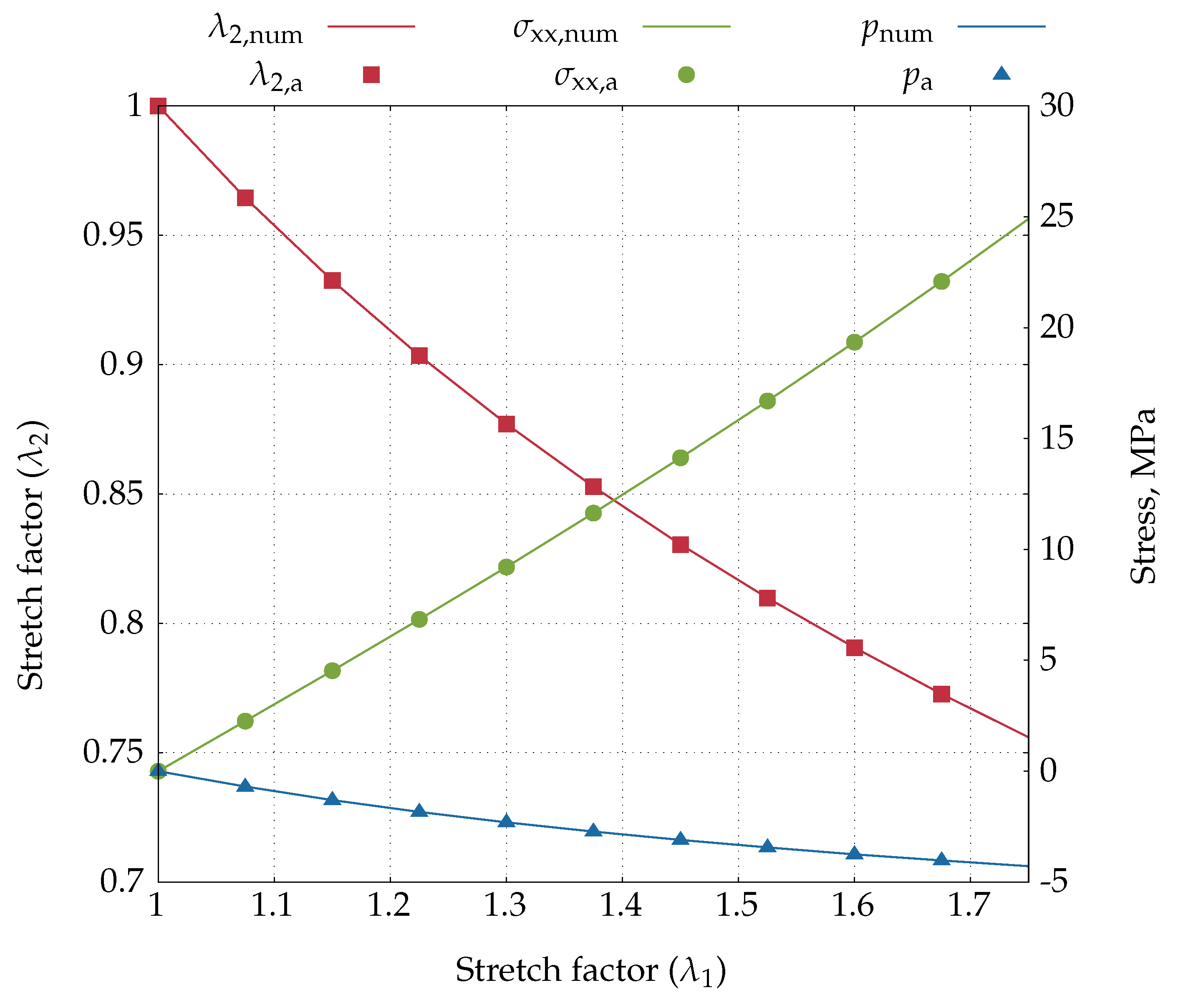

4.2.1. Uniaxial Extension Test

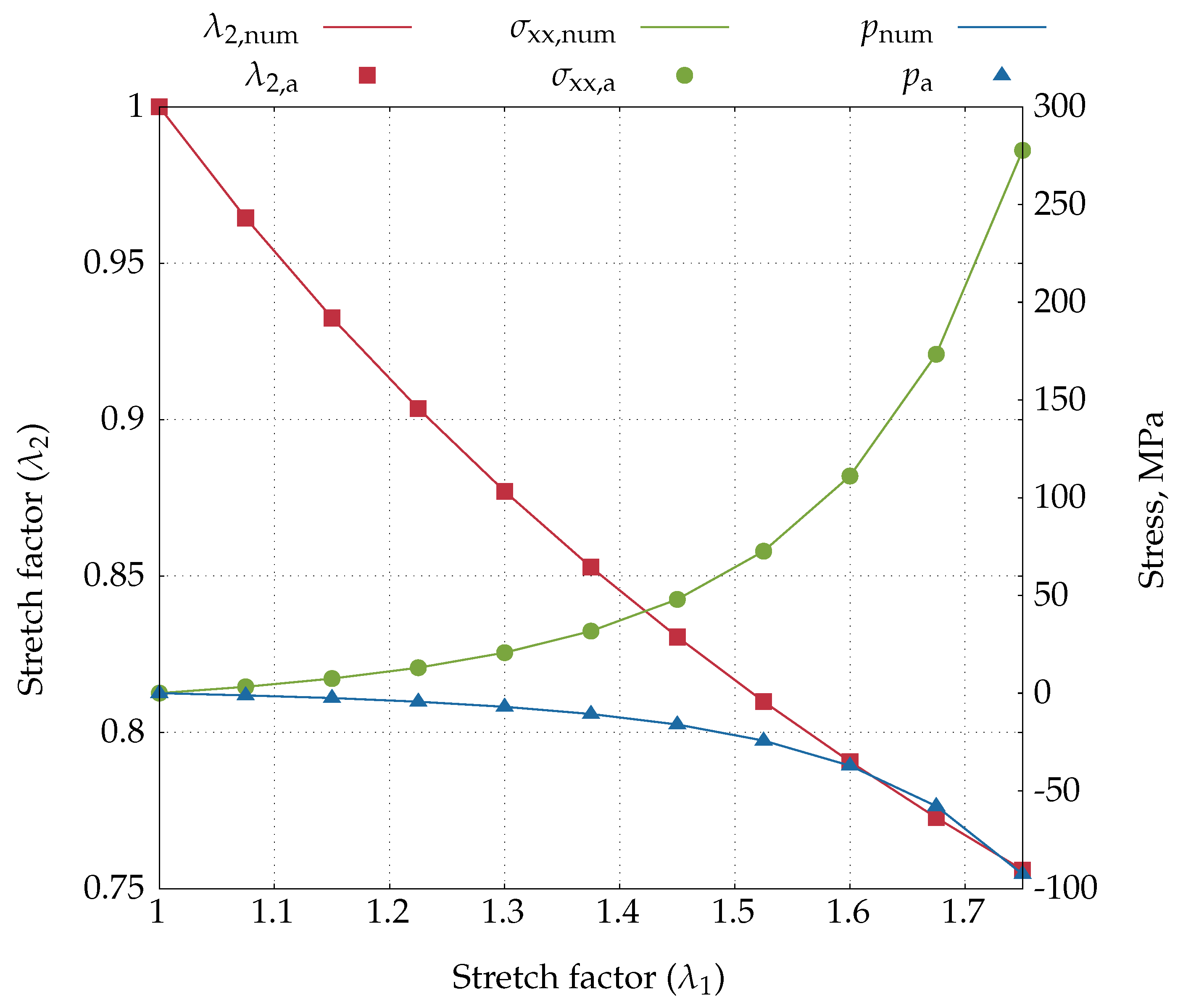

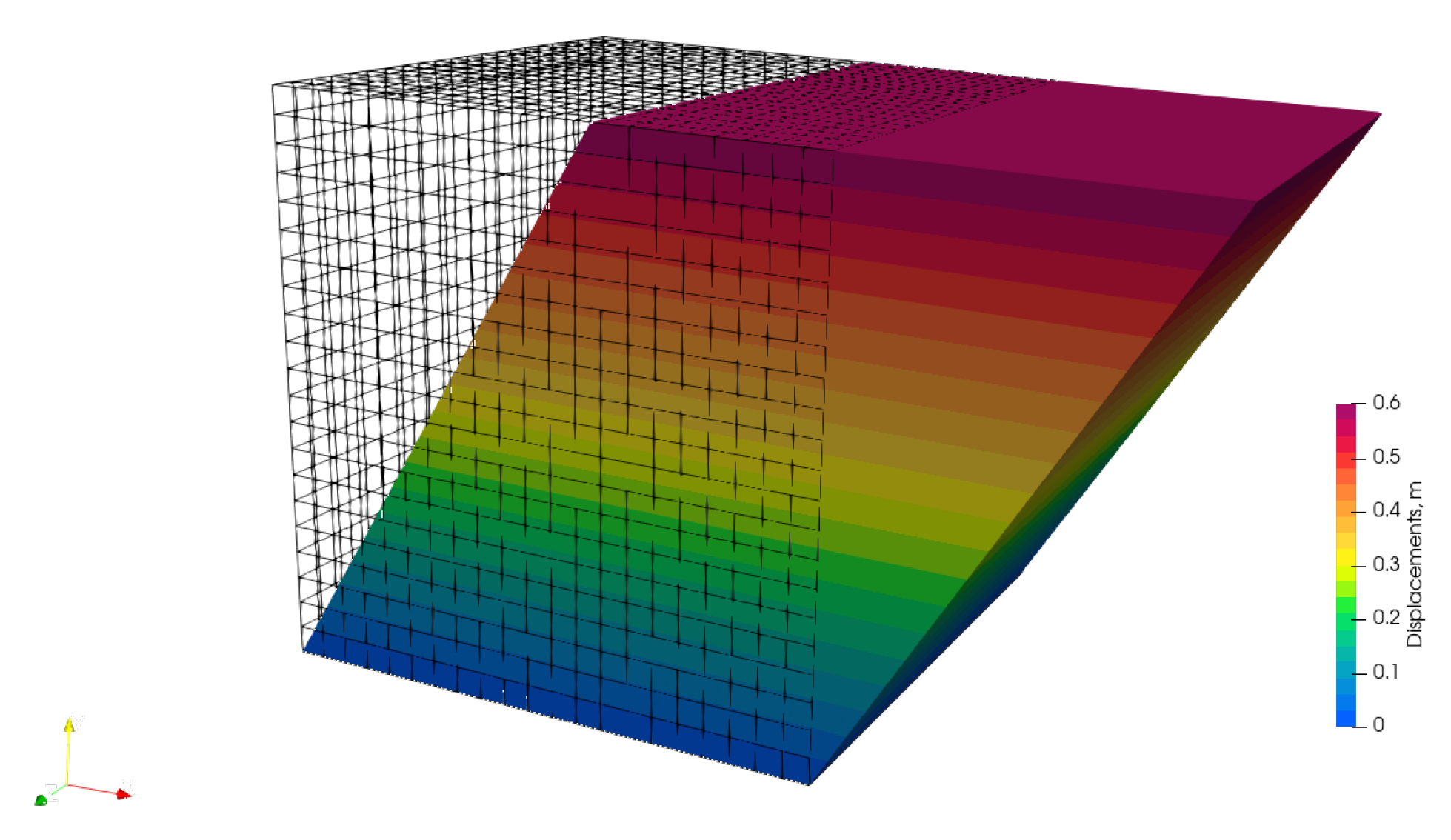

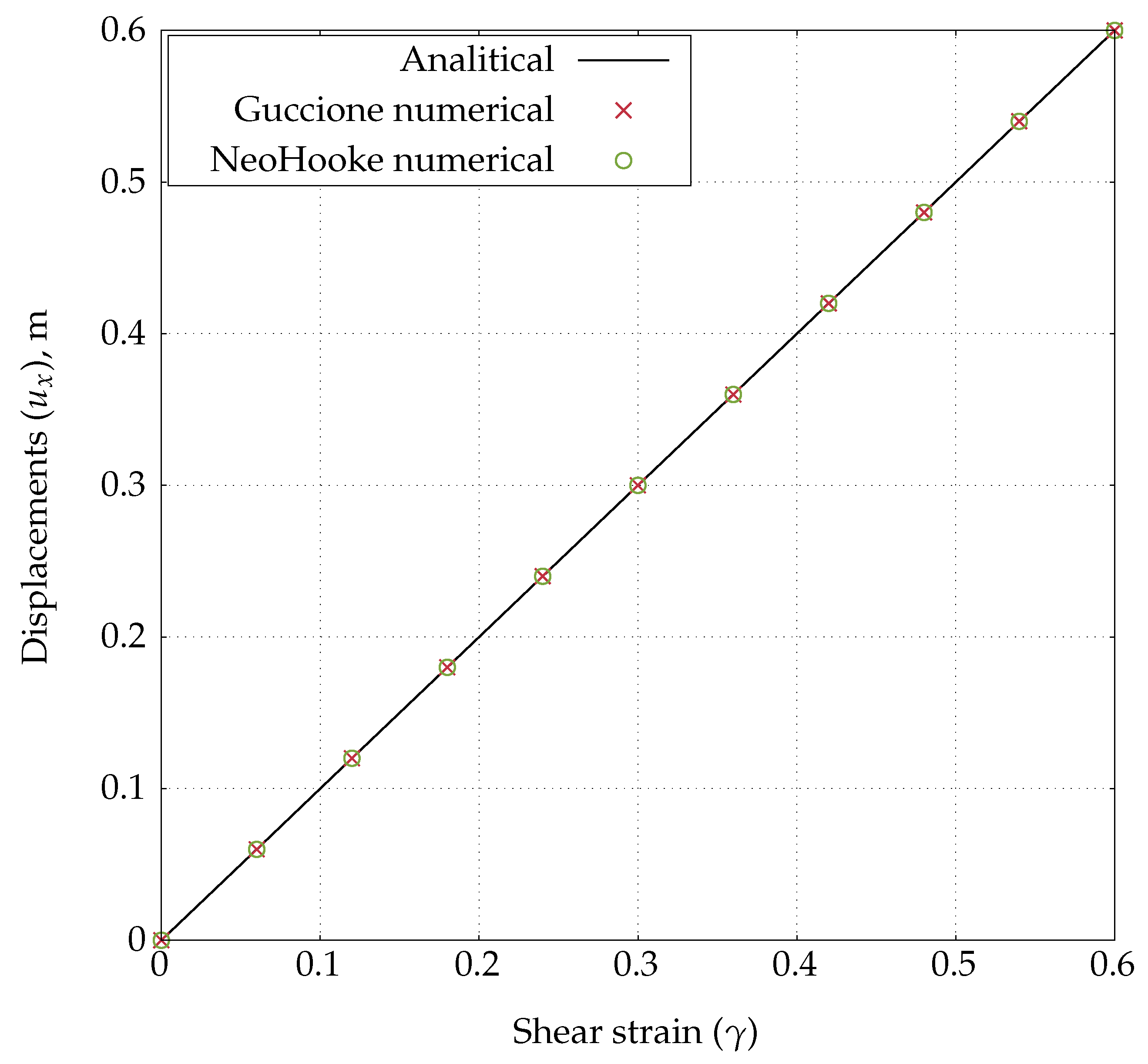

4.2.2. Simple Shear Test

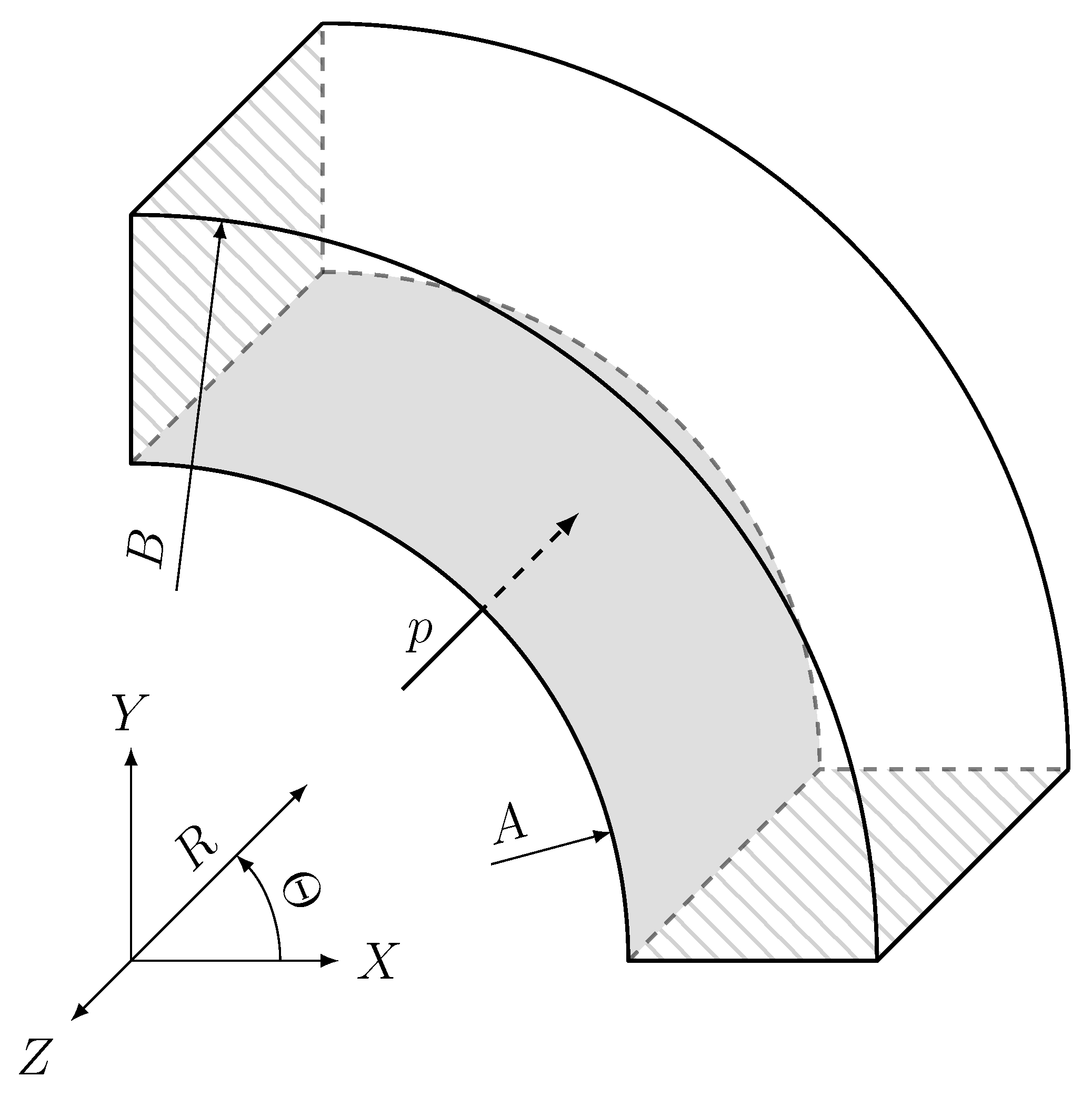

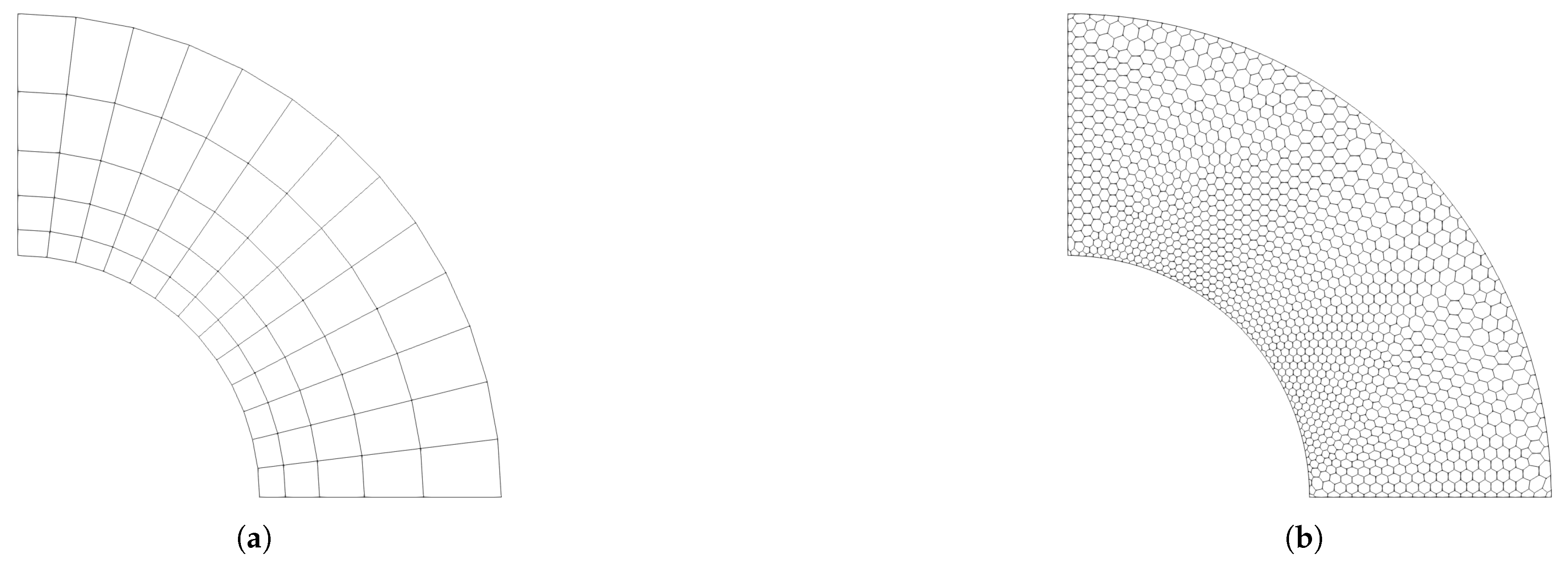

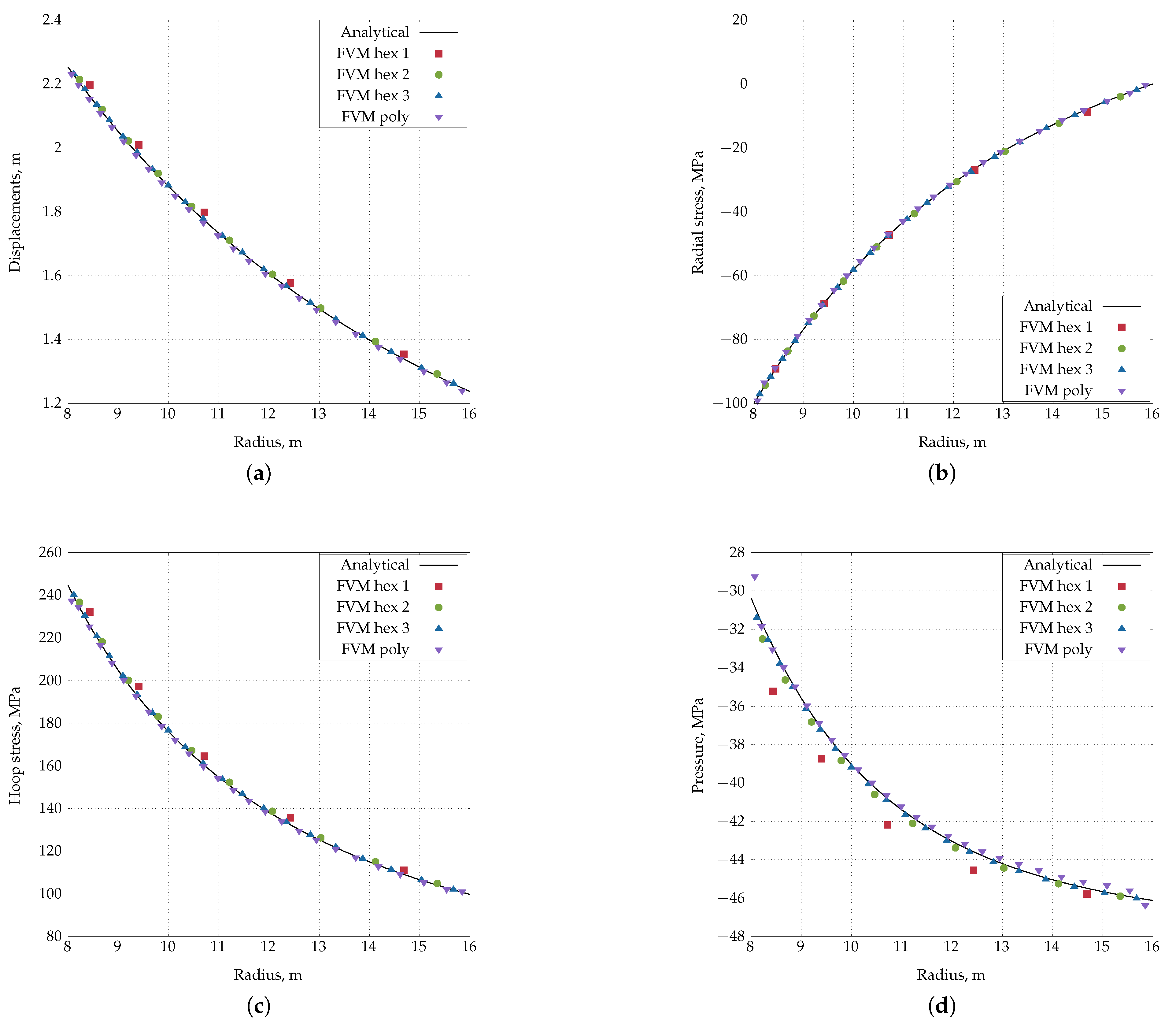

4.3. Inflation of a Thick-Wall Cylinder

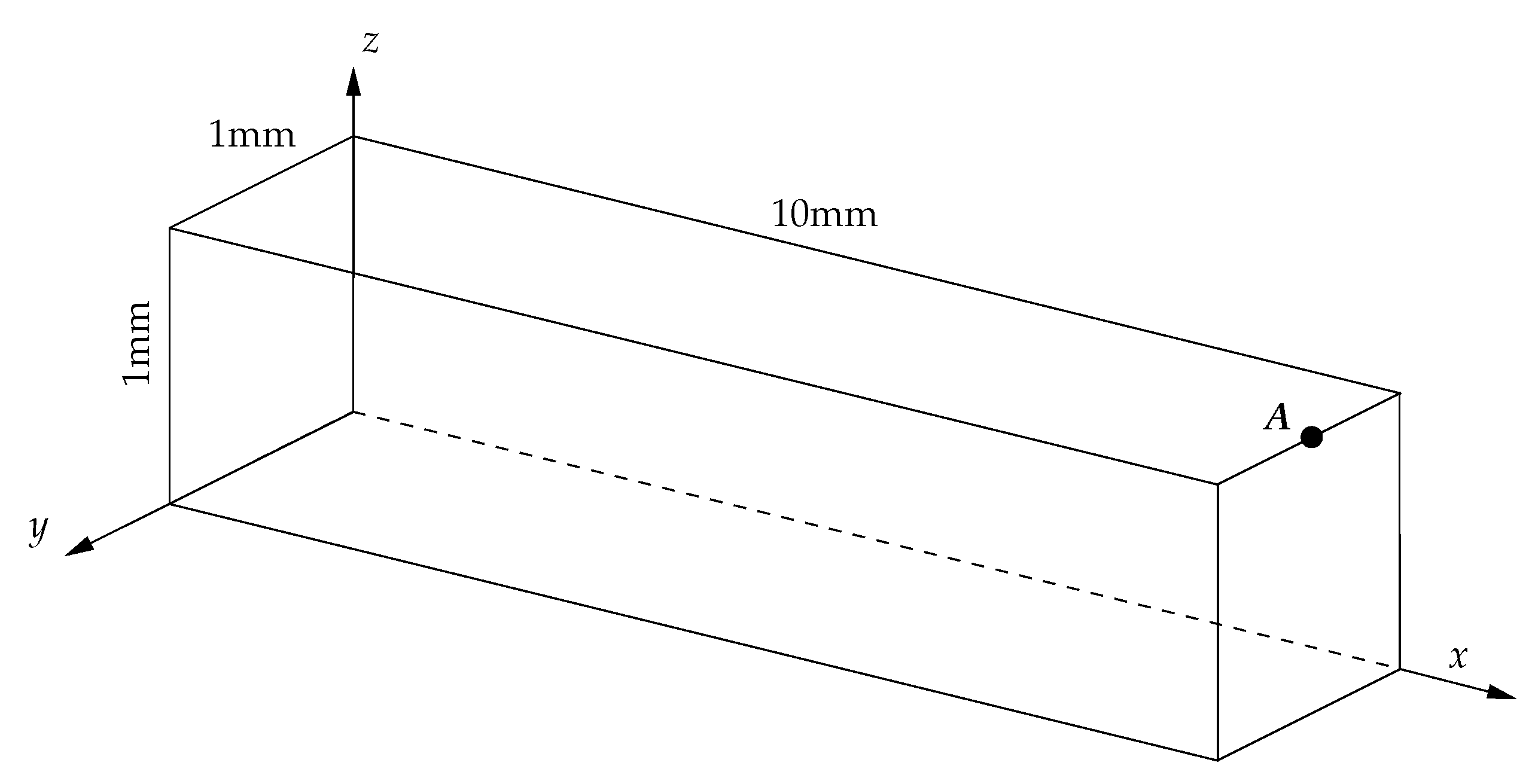

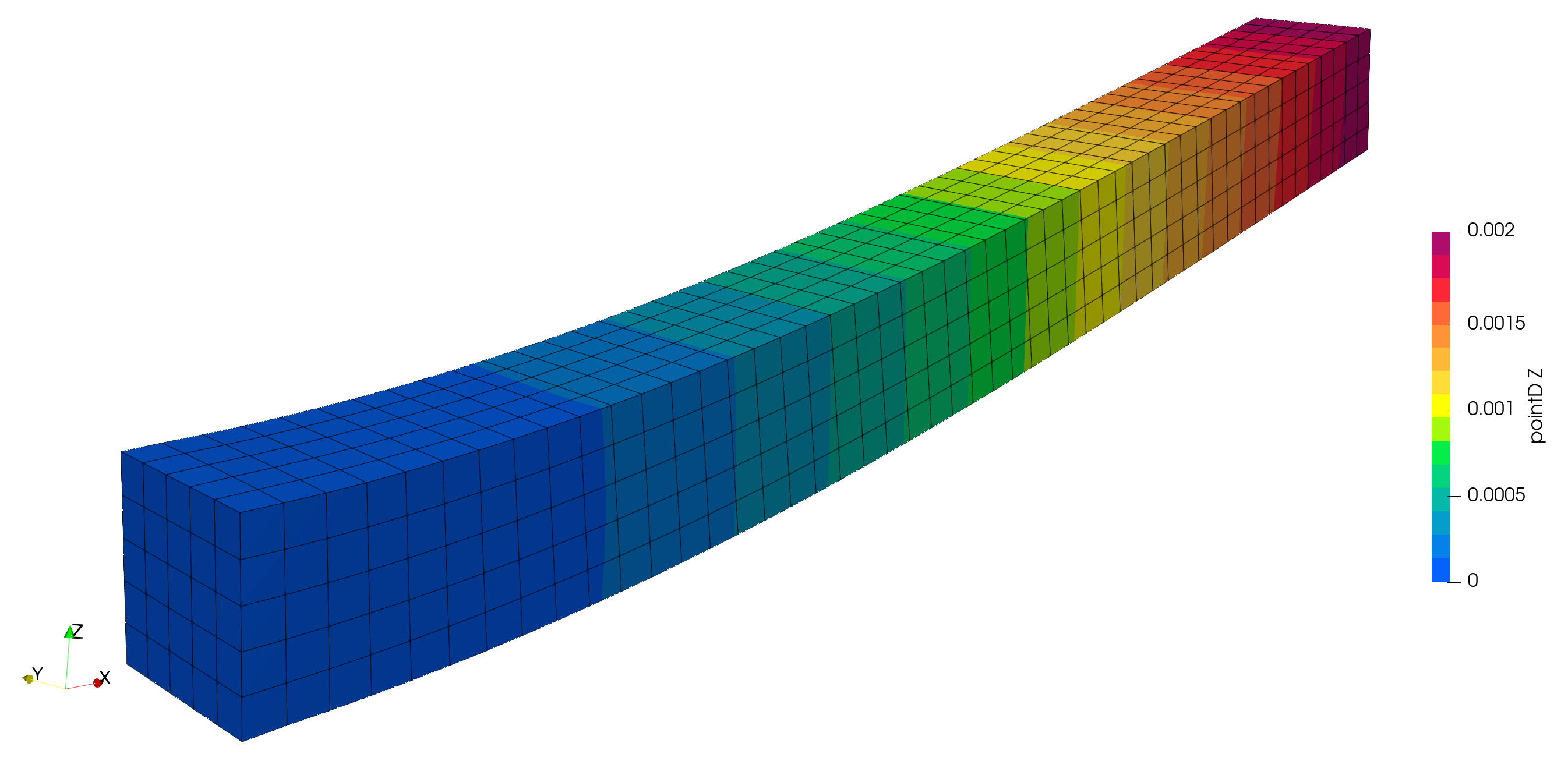

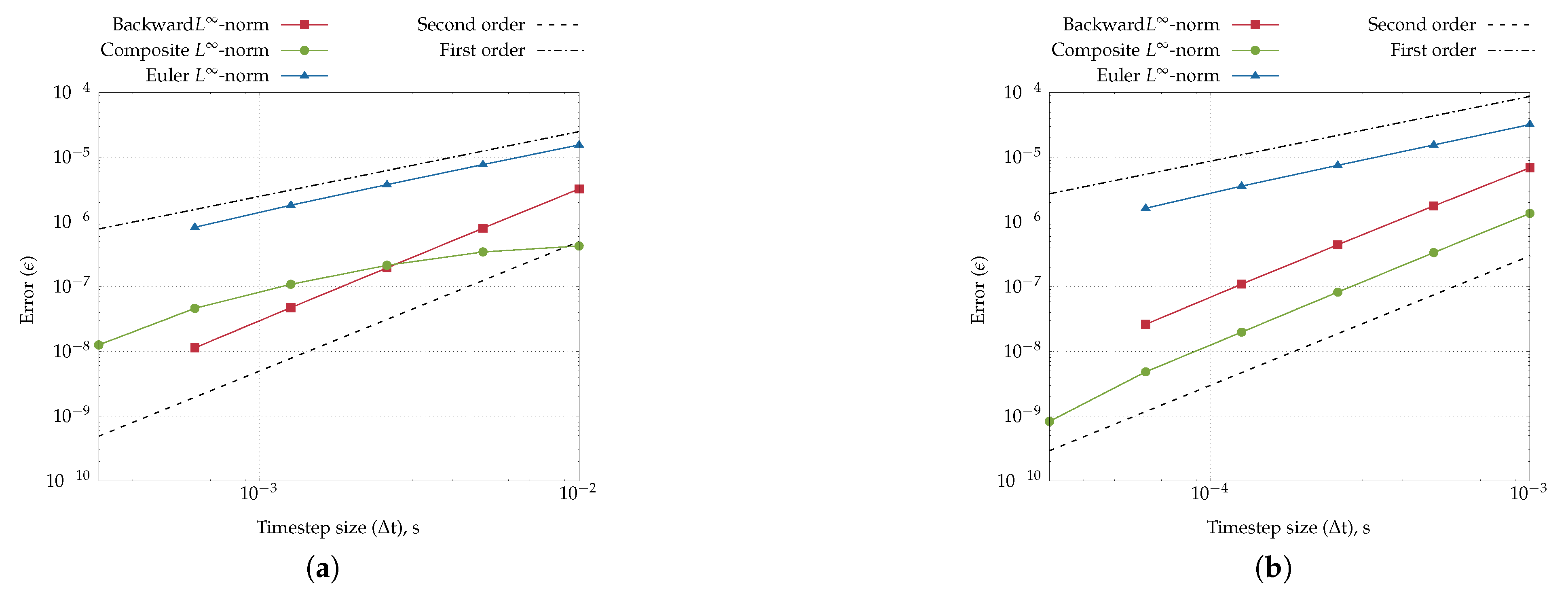

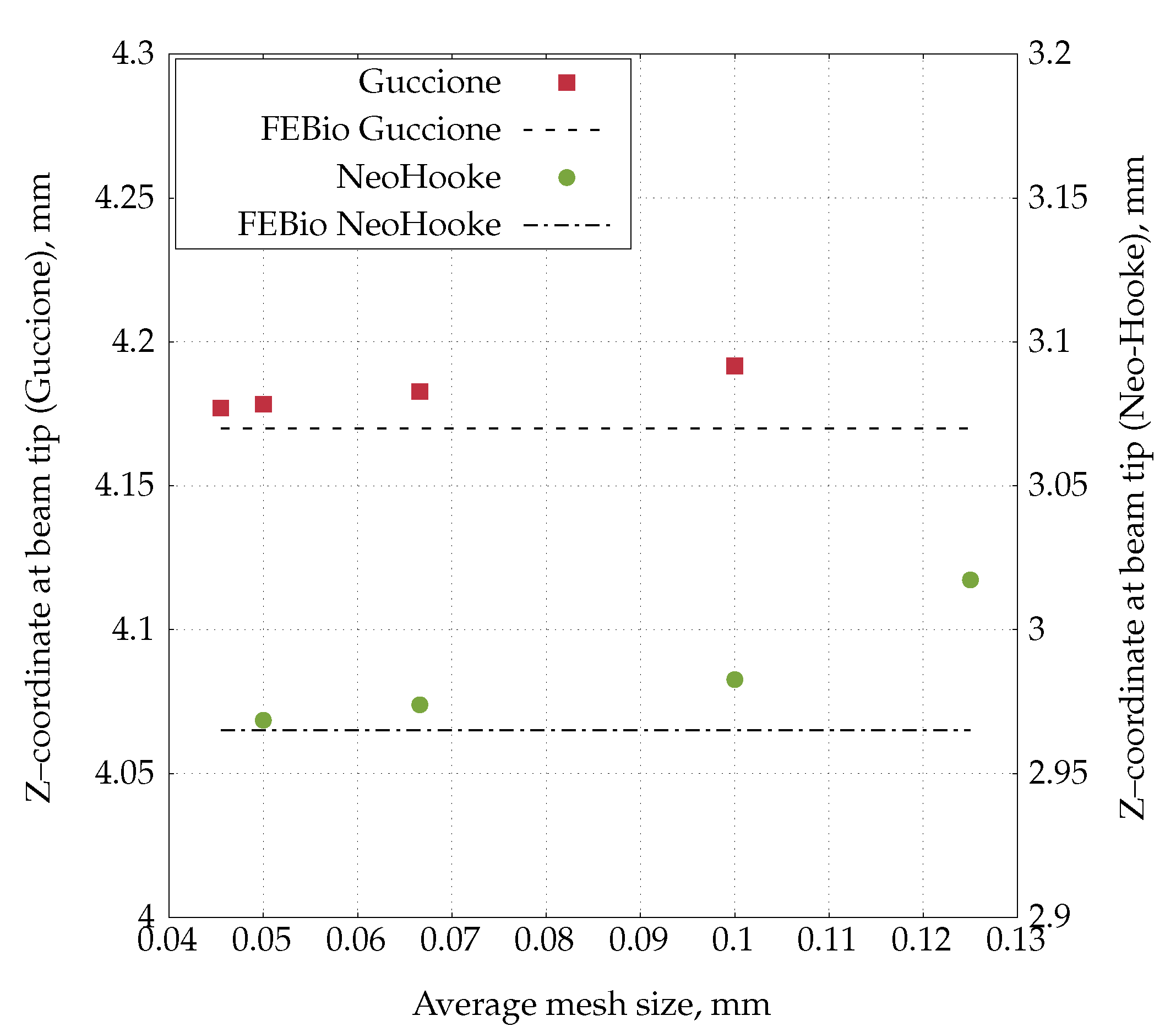

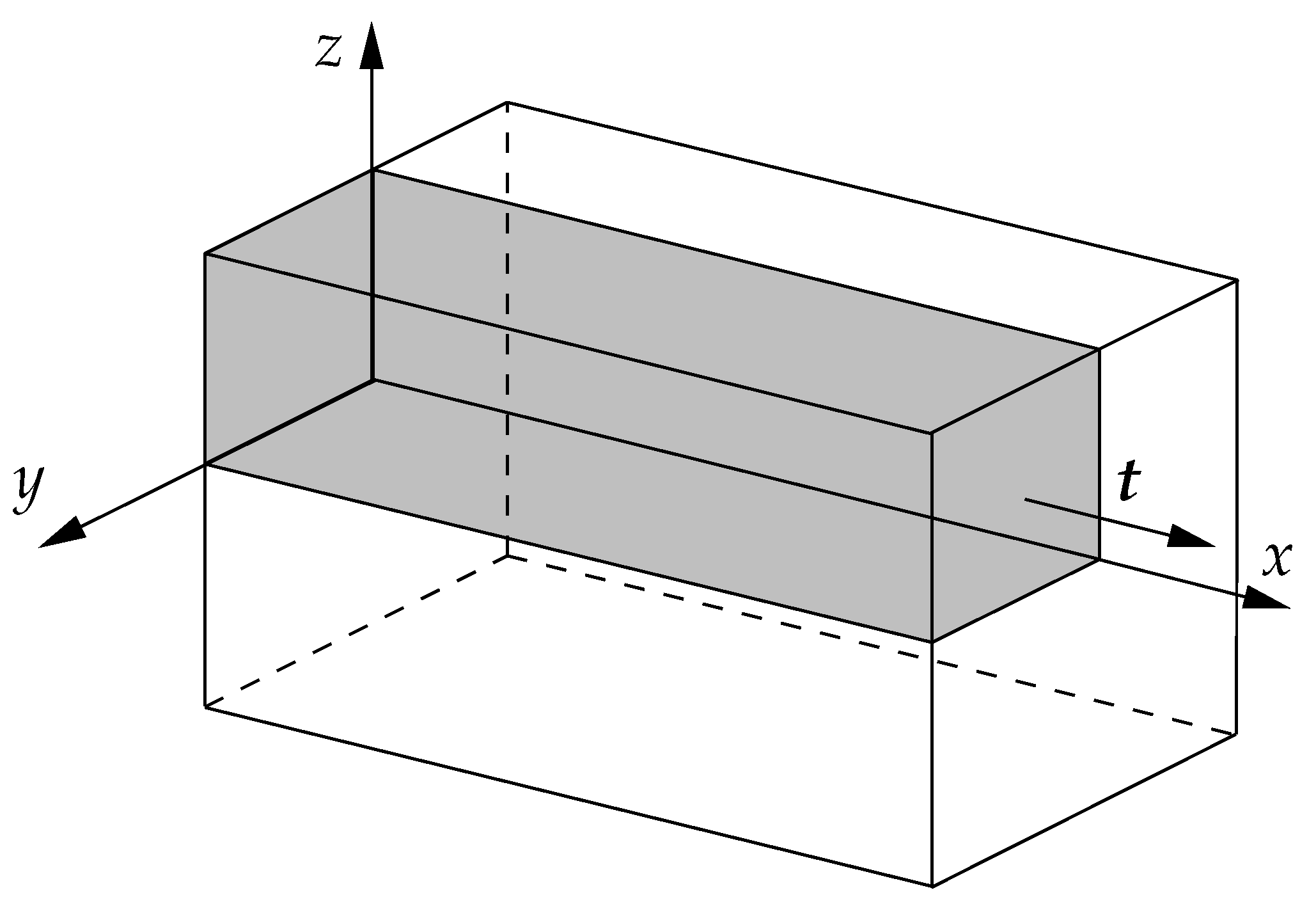

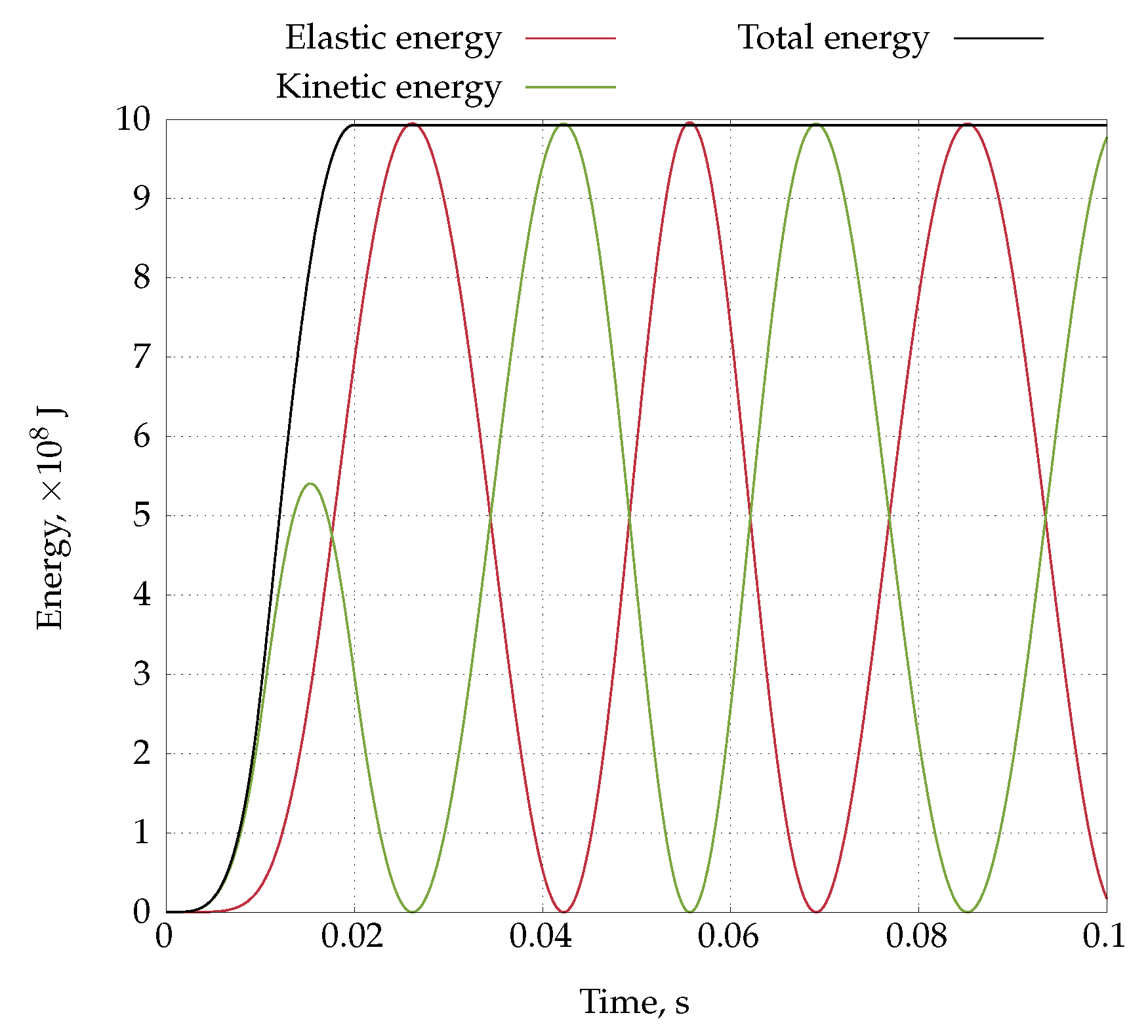

4.4. Heart Tissue Beam

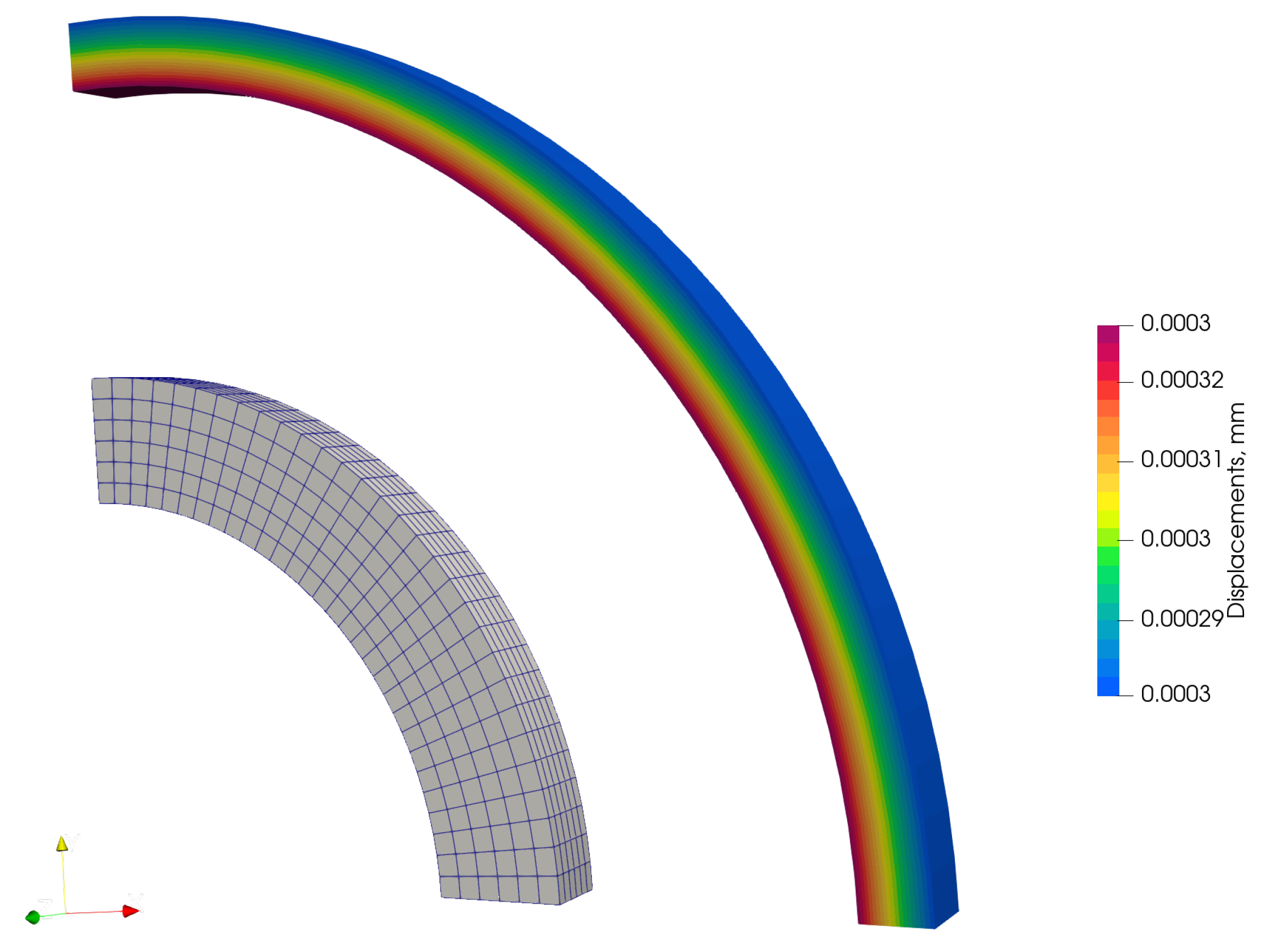

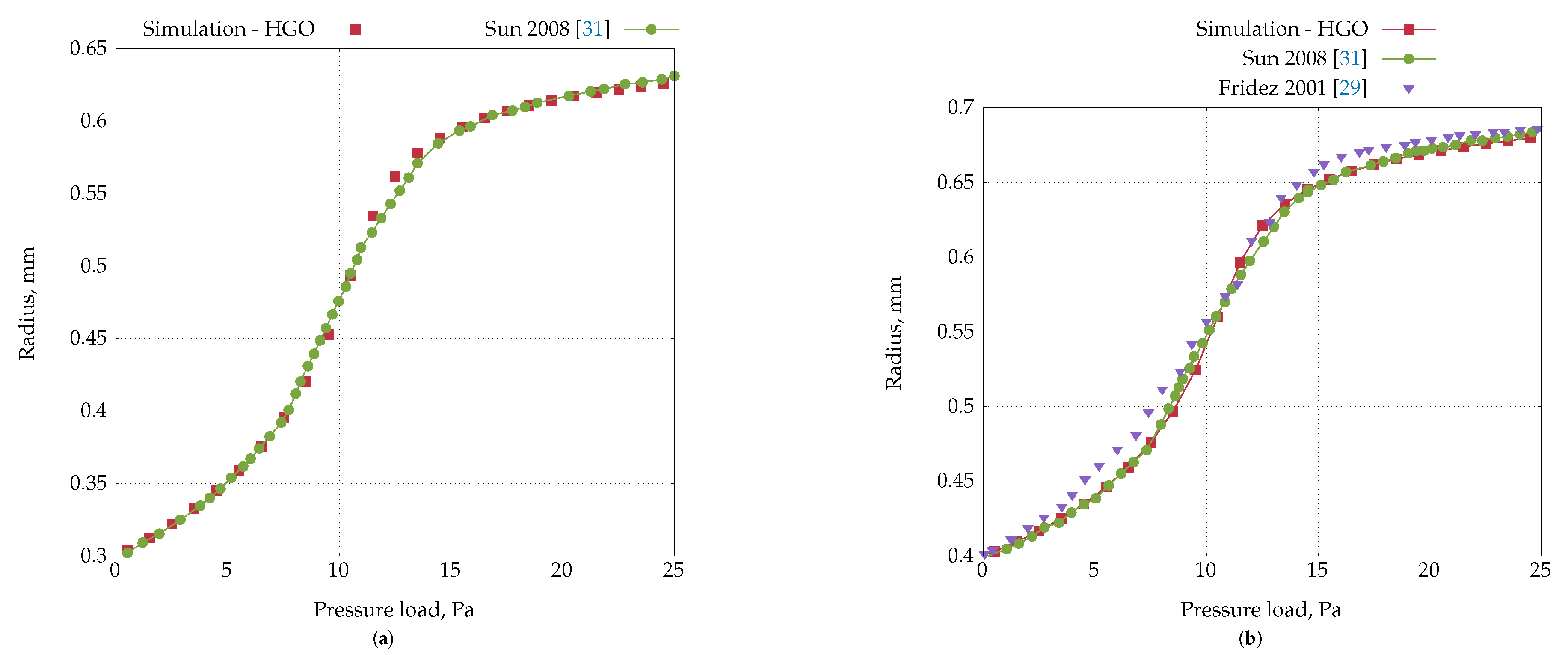

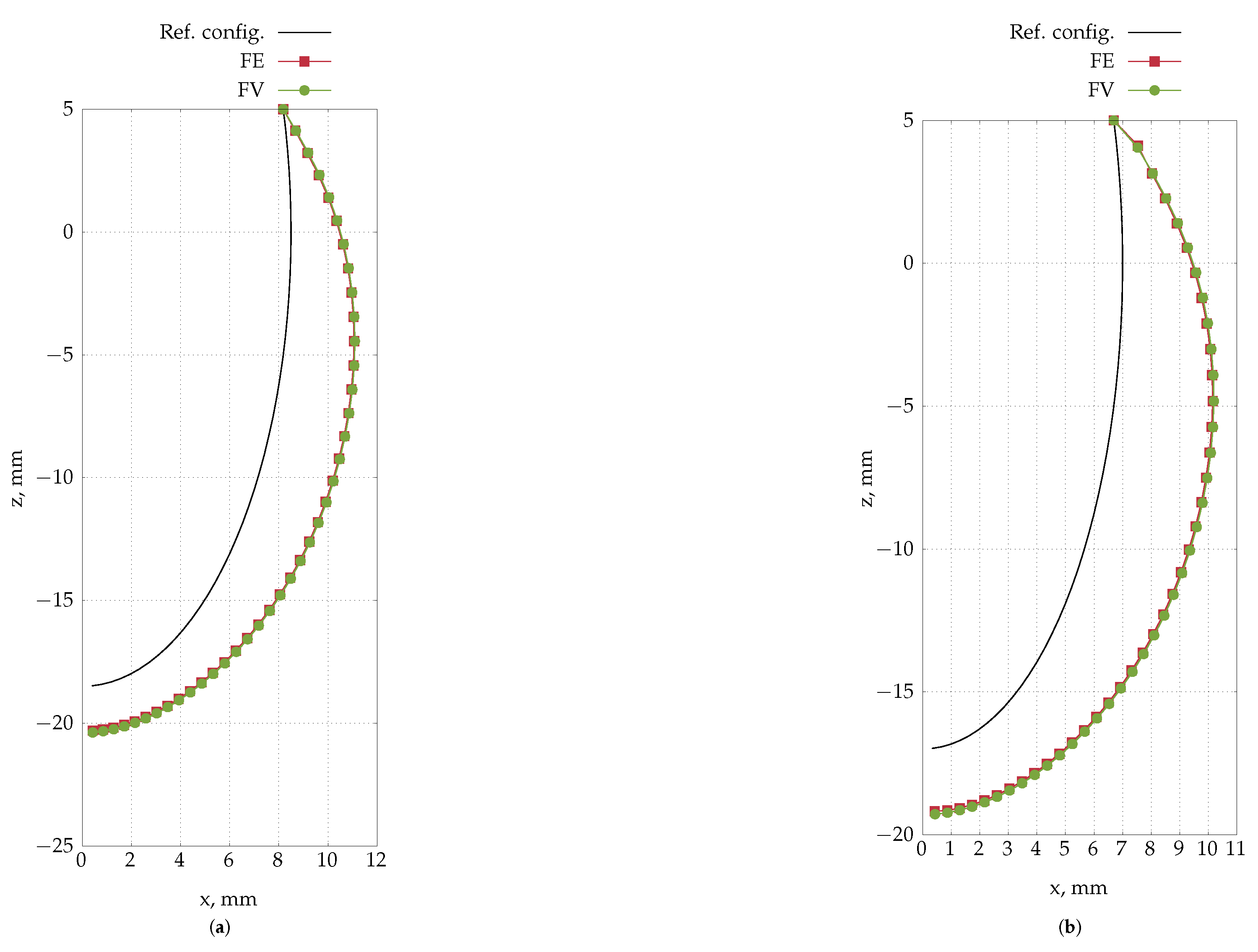

4.5. Inflation of a Rat Carotid Artery

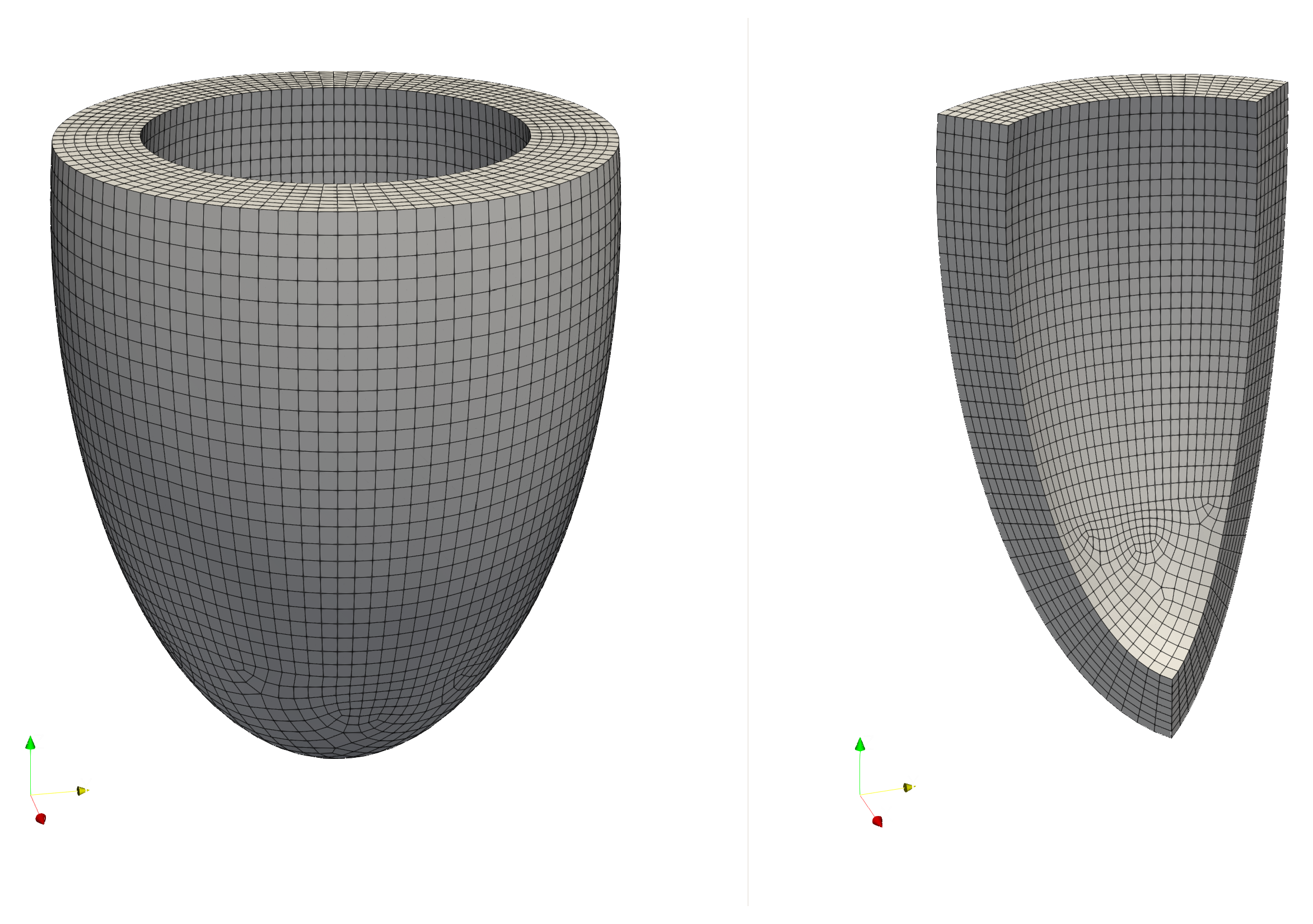

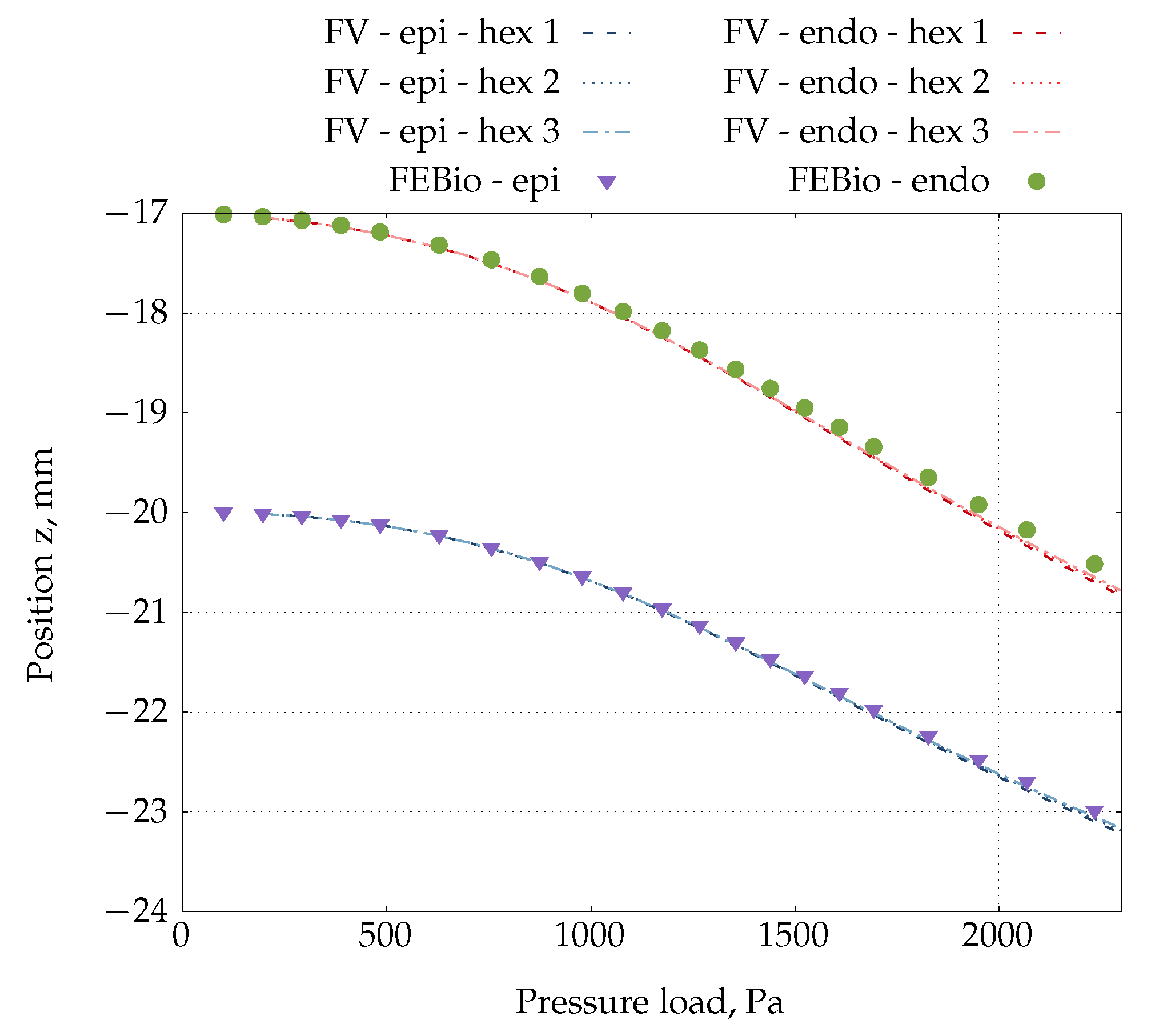

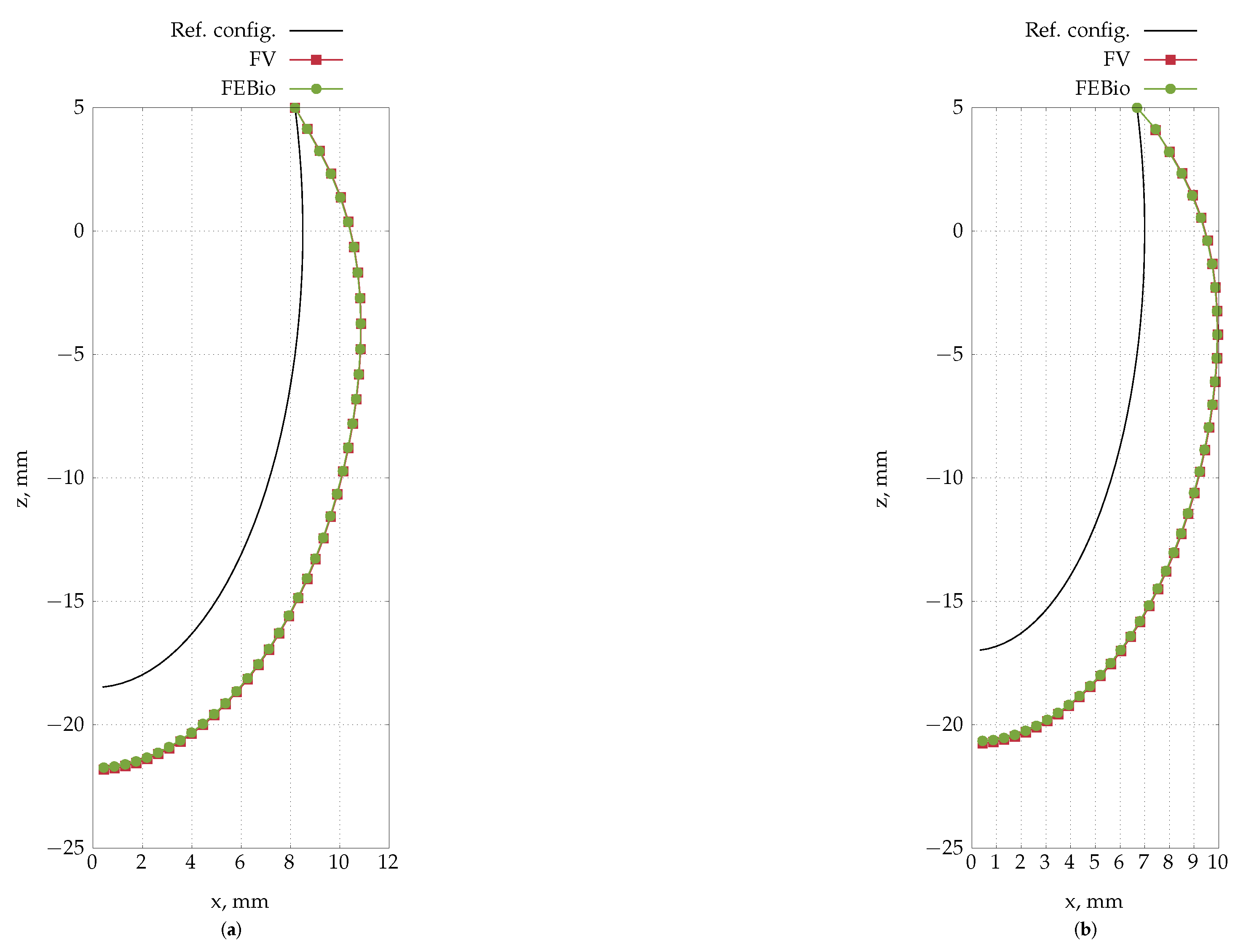

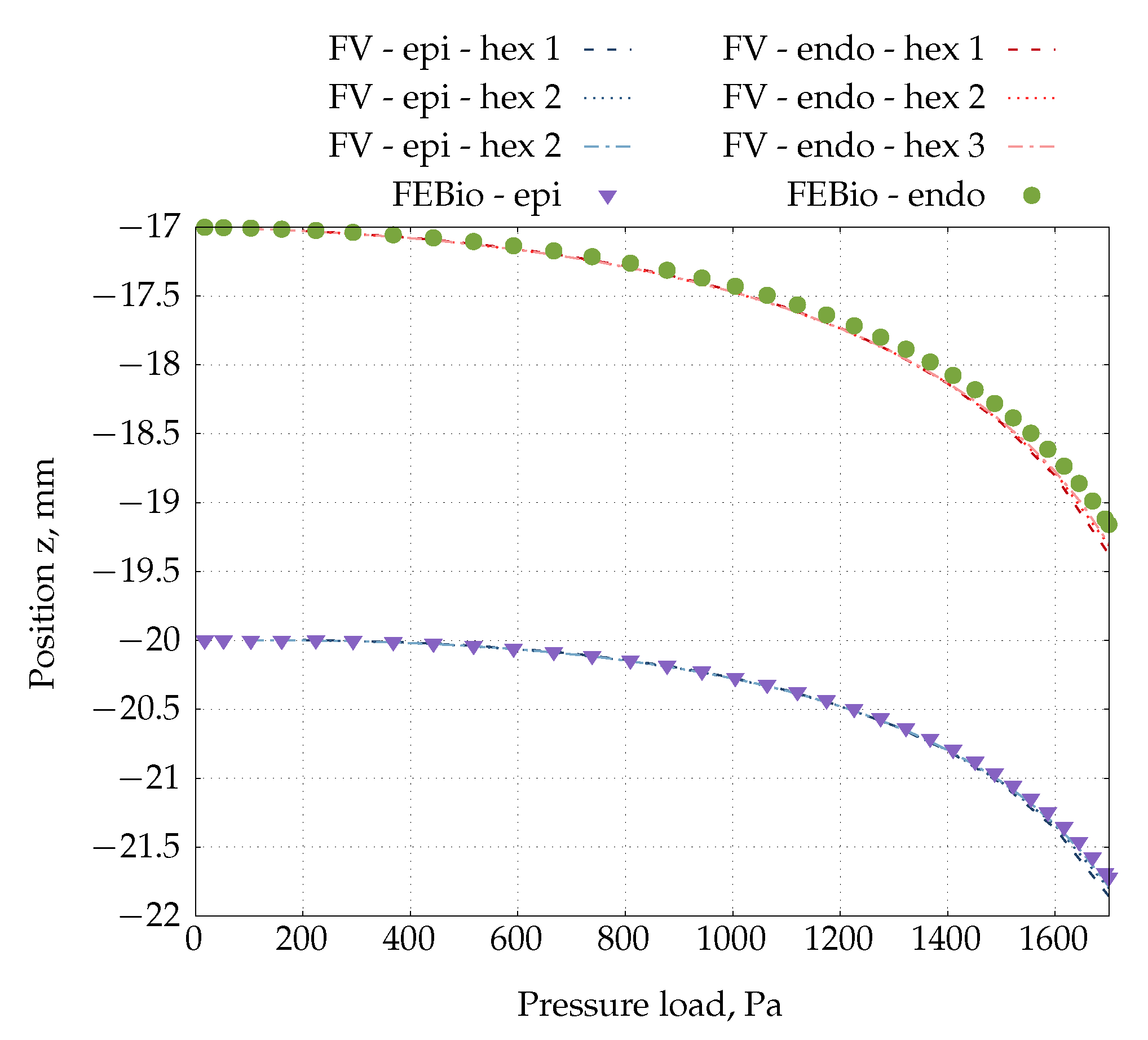

4.6. Inflation of an Idealised Ventricle

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| FE | Finite Element |

| CSM | Computational Solid Mechanics |

| FV | Finite Volume |

| SIMPLE | Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure Linked Equations |

| FSI | Fluid-structure interaction |

| CV | Control volume |

| HGO | Holzapfel-Gasser-Ogden |

| CRC | Consistent Rhie-Chow |

Appendix A Instantaneous Shear Modulus Approximation

Appendix B Linear System Coefficients

Appendix C Consistent Rhie-Chow Interpolation

Appendix D Material Laws

Appendix D.1. HGO Model

Appendix D.2. Guccione Model

Appendix A Pressurized Cylinder Equations

References

- Sussman, T.; Bathe, K.J. A finite element formulation for nonlinear incompressible elastic and inelastic analysis. Computers and Structures 1987, 26, 357–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardiff, P.; Demirdžić, I. Thirty Years of the Finite Volume Method for Solid Mechanics. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2021, 28, 3721–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheel, M.A. A mixed finite volume formulation for determining the small strain deformation of incompressible materials. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 1999, 44, 1843–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijelonja, I.; Demirdžić, I.; Muzaferija, S. A finite volume method for large strain analysis of incompressible hyperelastic materials. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 2005, 64, 1594–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijelonja, I.; Demirdžić, I.; Muzaferija, S. A finite volume method for incompressible linear elasticity. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2006, 195, 6378–6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijelonja, I.; Demirdžić, I.; Muzaferija, S. Mixed finite volume method for linear thermoelasticity at all Poisson’s ratios. Numerical Heat Transfer, Part A: Applications 2017, 72, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patankar, S.; Spalding, D. A calculation procedure for heat, mass and momentum transfer in three-dimensional parabolic flows. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 1972, 15, 1787–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhie, C.M.; Chow, W.L. Numerical study of the turbulent flow past an airfoil with trailing edge separation. AIAA Journal 1983, 21, 1525–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, M.; Sraj, I.; Moukalled, F. A coupled finite volume solver for the solution of incompressible flows on unstructured grids. Journal of Computational Physics 2009, 228, 180–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangani, L.; Alloush, M.M.; Lindegger, R.; Hanimann, L.; Darwish, M. A Pressure-Based Fully-Coupled Flow Algorithm for the Control Volume Finite Element Method. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uroić, T.; Jasak, H. Block-selective algebraic multigrid for implicitly coupled pressure-velocity system. Computers & Fluids 2018, 167, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.; Vukčević, V.; Uroić, T.; Simoes, R.; Carneiro, O.; Jasak, H.; Nóbrega, J. A coupled finite volume flow solver for the solution of incompressible viscoelastic flows. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2019, 265, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, H.G.; Tabor, G.; Jasak, H.; Fureby, C. A tensorial approach to computational continuum mechanics using object-oriented techniques. Computers in Physics 1998, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, P.; Denner, F.; Abdol-Azis, M.H.; Marquis, A.; van Wachem, B.G. Unified formulation of the momentum-weighted interpolation for collocated variable arrangements. Journal of Computational Physics 2018, 375, 177–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzapfel, G.A.; Gasser, T.C.; Ogden, R.W. A new constitutive framework for arterial wall mechanics and a comparative study of material models. Journal of Elasticity 2000, 61, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guccione, J.M.; McCulloch, A.D.; Waldman, L.K. Passive material properties of intact ventricular myocardium determined from a cylindrical model. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 1991, 113, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardiff, P.; Karač, A.; De Jaeger, P.; Jasak, H.; Nagy, J.; Ivanković, A.; Tuković, Ž. An open-source finite volume toolbox for solid mechanics and fluid-solid interaction simulations, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Cardiff, P.; Batistić, I.; Tuković, Ž. solids4foam: A toolbox for performing solid mechanics and fluid-solid interaction simulations in OpenFOAM. Journal of Open Source Software 2025, 10, 7407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirdžić, I.; Cardiff, P. Symmetry plane boundary conditions for cell-centered finite-volume continuum mechanics. Numerical Heat Transfer, Part B: Fundamentals 2022, 83, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathe, K.J.; Baig, M.M.I. On a composite implicit time integration procedure for nonlinear dynamics. Computers & Structures 2005, 83, 2513–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathe, K.J.; Noh, G.C. On a composite implicit time integration procedure for nonlinear dynamics. Computers & Structures 2005, 83, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuković, Ž.; Perić, M.; Jasak, H. Consistent second-order time-accurate non-iterative PISO-algorithm. Computers & Fluids 2018, 166, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirdžić, I.; Muzaferija, S. Numerical method for coupled fluid flow, heat transfer and stress analysis using unstructured moving meshes with cells of arbitrary topology. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 1995, 125, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuković, Ž.; Karač, A.; Cardiff, P.; Jasak, H.; Ivanković, A. OpenFOAM Finite Volume Solver for Fluid-Solid Interaction. Transactions of FAMENA 2018, 42, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, S.A.; Ellis, B.J.; Ateshian, G.A.; Weiss, J.A. FEBio: Finite Elements for Biomechanics. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 2012, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, S.A.; Ateshian, G.A.; Weiss, J.A. FEBio: History and Advances. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering 2017, 19, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoshenko, S.; Goodier, J. Theory of Elasticity; McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1970.

- Land, S.; Gurev, V.; Arens, S.; Augustin, C.M.; Baron, L.; Blake, R.; Bradley, C.; Castro, S.; Crozier, A.; Favino, M.; et al. Verification of cardiac mechanics software: benchmark problems and solutions for testing active and passive material behaviour. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2015, 471, 20150641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P., F.; A., M.; H., M.; JJ., M.; K., H.; N., S. Short-Term biomechanical adaptation of the rat carotid to acute hypertension: contribution of smooth muscle. Annals of Biomedical Engineering 2001, 29, 26–34. 2001, 29, 26–34. [CrossRef]

- Zulliger, M.A.; Fridez, P.; Hayashi, K.; Stergiopulos, N. A strain energy function for arteries accounting for wall composition and structure. Journal of Biomechanics 2004, 37, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Chaikof, E.L.; Levenston, M.E. Numerical Approximation of Tangent Moduli for Finite Element Implementations of Nonlinear Hyperelastic Material Models. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 2008, 130, 061003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | When there is no difference between initial and current configuration like in the case of linear elasticity, subscript next to the ∇ operator is omitted. |

| 2 | Discretisation of temporal solution domain will be described later, but one can define here previous time instance , while current time instance is , where is the time-step size. |

| 3 | In the Neo-Hookean model, the shear modulus remains constant. In contrast, for example, in the HGO model the shear modulus coincides with that of the Neo-Hookean model in the undeformed state, but it evolves with deformation of the elastic body |

| 4 | It is usual practice to use iterative solution procedure to solve non-linear problems in computational mechanic. Even in the case of linear problems, iterative solution procedure have to be used in the framework of FV method since different kinds of corrections related to preservation of accuracy are applied using differed correction approach. |

| 5 | In the remainder of this manuscript, the operator denotes the calculation of cell-face values by linear interpolation of neighbouring cell-centre values without skewness correction, as defined in Equation (27), whereas the operator denotes the linear interpolation with skewness correction, as defined in Equation (26). Left-hand side superscript in the above operators indicates mesh configuration on which linear interpolation is performed and on which gradient for skewness correction is calculated. |

| 6 | The contribution arising from the normal derivative of the normal displacement increment is neglected, as it is tensorial in nature and would significantly increase the complexity of deriving the pressure increment equation. |

| 7 | In reality, the mesh is 3-D and consists of one layer of prismatic cells with quadrilateral, triangular and polygonal base. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).