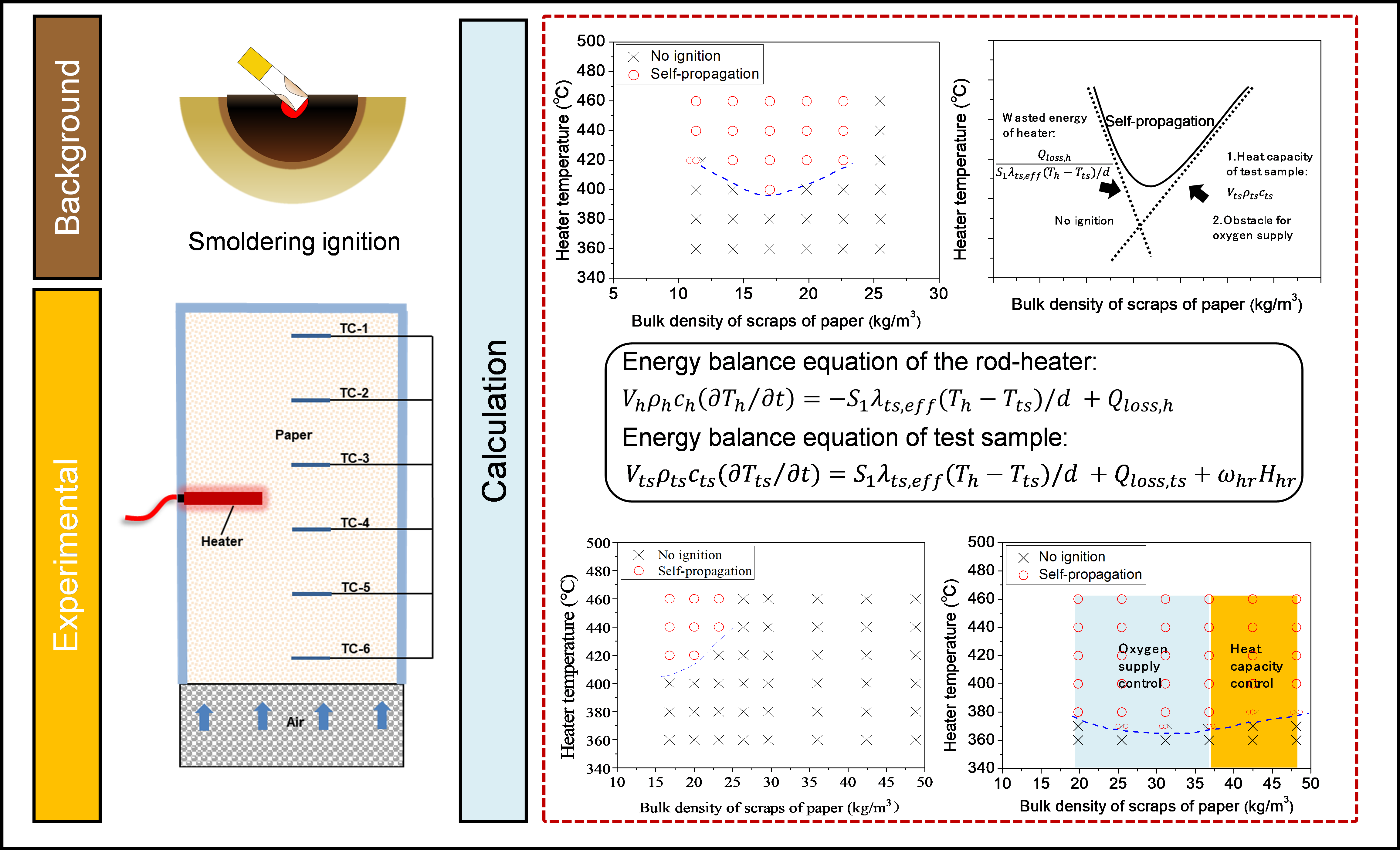

1. Introduction

Smoldering combustion is a low-temperature, slow, and flameless combustion phenomenon [

1,

2] that occurs as an oxidation reaction on the surface of porous fuels. This process relies on the heat generated from its own heterogeneous reactions to sustain its propagation. Smoldering combustion can be initiated by heat sources that are insufficient to produce a flame, and once initiated, it is difficult to extinguish. This characteristic is particularly evident in forest subterranean fires, which can burn for extended periods, ranging from days to months or even longer [

3,

4]. Furthermore, under certain conditions, smoldering combustion can transition into fully developed fires, resulting in significant economic losses. The burning process of smoldering combustion produces a substantial amount of toxic and harmful gases, which pose serious threats to both the social environment and human health.

Due to its critical importance in fire safety [

5], the fundamental characteristics of smoldering combustion have been extensively studied. Rein et al [

6] studied the effect of bulk density on smoldering combustion using polyurethane foam as an experimental sample. It was shown that the rate of smoldering propagation decreased with increasing density. Moussa et al [

7] proposed a two-step reaction mechanism for cellulosic materials, where the fuel is first pyrolyzed and then oxidized. The process of smoldering combustion is a complex process that consists of a combination of heat and mass transfer. The ignition point is determined by a delicate balance between the heat supplied by the reaction front, heat loss, and the heat generated by the chemical reaction [

8]. Therefore, there are many factors affecting the ignition of smoldering combustion. Hagen et al [

9] found that bulk density has a tremendous effect on the ignition temperature and weight loss of smoldering combustion. Hadden et al [

10] experimentally found that the critical heat flux of smoldering combustion increases with increasing sample size, and further that the increase in sample size increases the ignition limit of smoldering combustion. Xie et al [

11] investigated the effect of high bulk density, and the effect of wind velocity on the ignition characteristics of cotton bales and found that the ignition diffusion rate and peak temperature increased almost linearly with wind velocity due to the increase in oxygen supply. In addition, Walther et al [

12] found that the minimum energy required for ignition decreased as the oxygen mass fraction increased. Thus, bulk density, sample size, and air flow rate are important parameters affecting ignition.

The smoldering of municipal solid waste, often triggered by discarded cigarettes or other smoking-related materials, has consistently been identified as a leading contributor to the fire pathways through which urban spot fires are initiated. According to the CTIF Report No. 29 (2024) [

13], which provides a comprehensive analysis of global fire statistics for 2022, there were 640,093,000 residential fires, accounting for 23.1% of the total number of fires. Additionally, 51,564,000 fires were attributed to smoking-related factors, representing the third highest cause of fires among all contributing factors.

Despite extensive investigations into the smoldering behavior of various materials, limited information exists regarding the specific conditions required for smoldering to be initiated in paper scraps by a discarded cigarette. The ignition mechanism of fuel by a discarded cigarette butt fundamentally differs from that of flames or radiation [

14,

15]. When a cigarette butt comes into contact with a fuel, energy is transferred from the cigarette to the fuel and its surrounding environment. However, as the cigarette no longer receives a continuous energy supply, its temperature decreases, thereby creating distinct boundary conditions for the heat source. If the cigarette butt remains sufficiently hot, carbon oxidation or oxidative pyrolysis reactions within the fuel bed can sustain the propagation of the smoldering front, potentially leading to smoldering or the generation of flames [

16]. The ignition threshold of the fuel bed under these unique boundary conditions is influenced by various factors [

17]. Given that paper is a ubiquitous combustible material, this study employs common paper scraps as the experimental material to investigate the ignition process. In this study, we used a rod-heater to simulate the process of cigarette ignition of paper scraps. A series of experiments were conducted to vary the rod-heater temperature, paper scraps bulk density, length, and wind speed conditions to investigate the propagation characteristics of paper scraps smoldering and the effect on the ignition limit of paper scraps.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Samples

In the present research, shredded paper scraps (

Figure 1) derived from commonly used cellulose paper were selected as experimental samples. The physical properties of these paper scraps are summarized in

Table 1. The samples were prepared in lengths of 30 mm, 45 mm, 60 mm, and 75 mm to investigate the influence of length variations on their combustion characteristics. The width of the paper scraps was maintained at 30 mm to ensure a controlled variable, while the thickness was measured as 8.7×10

-3 mm.

The bulk density of the paper scraps was regulated within the range of 5 kg/m³ to 50 kg/m³. Specifically, when the bulk density was lower than 5 kg/m³, it became challenging to achieve a uniform sample within the combustion chamber. On the other hand, when the bulk density exceeded 50 kg/m³, it became difficult to compress and stabilize the sample within the combustion chamber.

2.2. Experimental Setup and Experimental Conditions

The experimental investigation of smoldering ignition in paper scraps was conducted using the apparatus illustrated in

Figure 2. This experimental setup consists of a combustion chamber, a base, a heating system, a gas supply system, a temperature acquisition system, and a digital camera. The combustion chamber is a transparent cylindrical container with a length of 0.20 m and an internal diameter of 0.15 m, mounted on a stainless-steel base. The lower surface of the base is equipped with an air diffuser and covered with ceramic balls, which fill the entire internal space of the base. An annular air diffuser located at the base of the pedestal contains eight pairs of diametrically opposed holes, ensuring uniform airflow into the combustion chamber.

To monitor temperature variation at different vertical positions within the porous fuel bed, six K-type thermocouples (denoted as TC1-TC6) are evenly spaced at 2 cm intervals along the vertical center axis, as illustrated in

Figure 2. Temperature data are recorded at 5-second intervals. A rod-heater, controlled by an ignition controller, is inserted into the combustion chamber through a hole in the wall of the glass tube. The rod-heater is positioned centrally, equidistant from both the top and bottom of the chamber. The precise positioning of the thermocouples relative to the rod-heater is also depicted in

Figure 2.

To minimize the influence of environmental factors, the ambient temperature was controlled within a range of 15-20 °C, and the relative humidity was maintained between 30% and 40% throughout the experiment. A specified length of paper scraps was placed inside the combustion chamber and compressed to a predetermined bulk density. Air was introduced into the chamber at a controlled flow rate through an air diffuser located at the chamber’s base, which incorporated a honeycomb structure filled with ceramic balls to ensure uniform airflow distribution.

The temperature of the rod-heater was gradually increased from 340 °C to 460 °C in 10 °C increments. Once the desired temperature was reached, the heating was stopped, and the rod-heater was inserted directly into the combustion chamber. The ignition limit of the paper scraps fuel bed was then recorded as a function of several factors, including the initial temperature, the bulk density of the fuel bed, the length of the paper scraps, and the airflow rate. In the present research, ignition was defined when self-sustained propagation of the smoldering front was observed by every thermocouple.

In this experimental setup, the length of the paper scraps was varied between 30 and 75 mm, the bulk density ranged from 5 to 50 kg/m³, and the airflow rate varied from 0 to 30 NL/min. To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the results, each set of conditions was repeated three times.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Ignition Limit of Paper Scraps at Different Bulk Densities Without an External Air Flow

This section focuses on the influence of paper scrap bulk density within the fuel bed on the ignition limit under conditions without externally forced airflow.

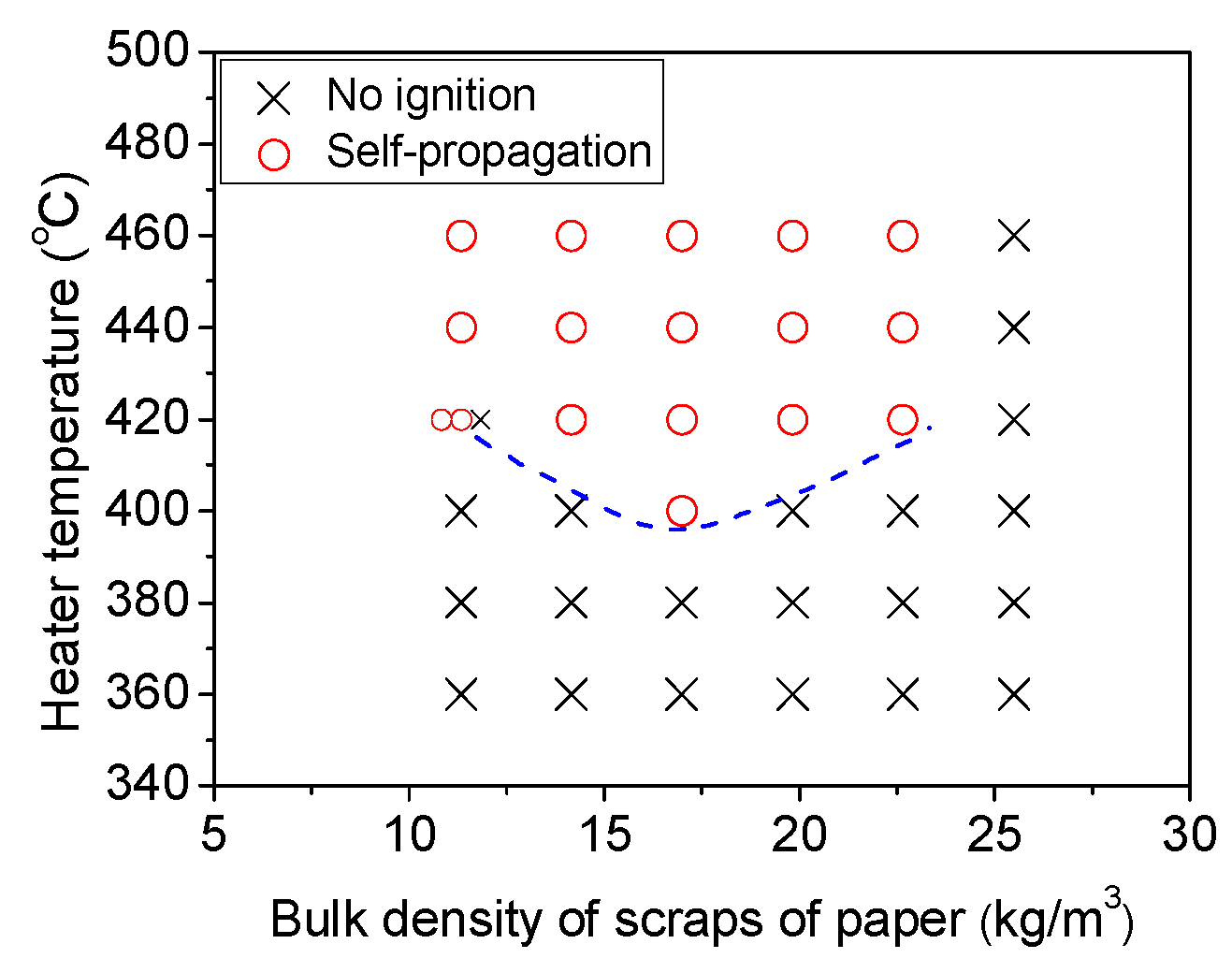

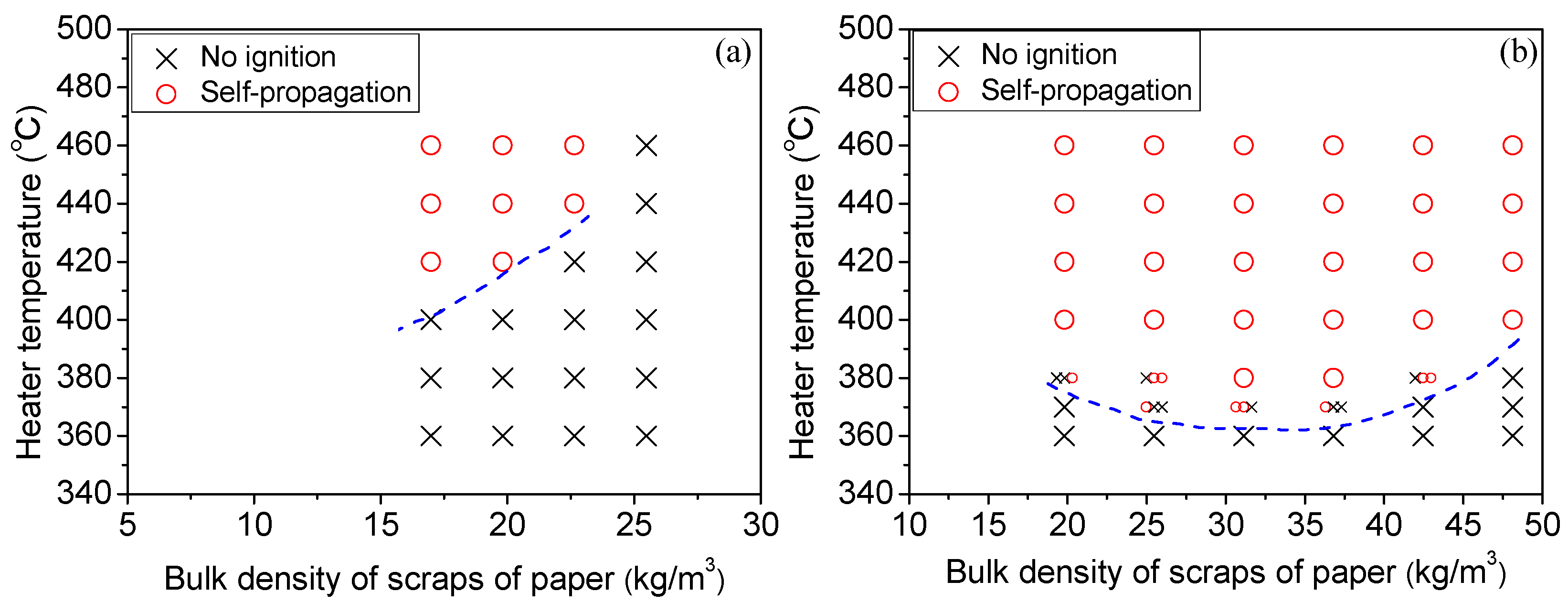

Figure 3 illustrates the trend of the smoldering ignition limit of paper scraps as the bulk density increases. Initially, the ignition limit decreases with increasing bulk density, but it subsequently increases with further increments in bulk density. At a bulk density of 12 kg/m³ and a rod-heater temperature of 420 °C, only one out of the three replicate experiments failed to ignite, while the other two successfully ignited. Consistent results were obtained across all three replicates for all other conditions.

As shown in

Figure 3, the ignition limit of paper scraps exhibits a U-shaped trend with increasing bulk density at a fixed paper scrap length. This behavior is attributed to the competitive effects of porosity, heat capacity, and oxygen supply. To qualitatively describe this U-shaped trend, a simple model is presented in this paper. Due to the cessation of electric current supply to the rod-heater when embedding it into the fuel bed, the temperature of the rod-heater decreased. This decrease is primarily attributed to heat loss, which includes heat transfer from the rod-heater to the test sample and heat loss to the surrounding air through convection or radiation. The energy balance equations of the rod-heater and the test sample are given as Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively:

Energy balance equation of the rod-heater:

Energy balance equation of test sample:

In Equation (1), the first term is the transient energy of the heater, the second term is the heat conduction from the rod-heater to the test sample, and the last term is the heat loss from the rod-heater to the ambient air due to convection or radiation and has negative value.

In Equation (2), the first term is the transient energy of the test sample, the second term is the heat conduction from the rod-heater to test sample, the third term is the heat loss of test sample to ambient and has negative value, and the last term gives the heat generated within the test sample.

The effect of porosity can be explained as follows. The porosity decreases with the increase of bulk density, resulting in the increase of the effective thermal conductivity of the sample: () For a low bulk density case, a small amount of heat was transferred from the rod-heater to the test sample (2nd term in Equations (1) and (2)). due to the low effective thermal conductivity of the sample. Meanwhile, there was a large heat loss from the heater to ambient air. (3rd term in Equation (1)) The energy lost from the rod-heater is defined as the ratio of and , then as the bulk density increases, this ratio decreases and the rod-heater gives off less heat to the environment, making ignition relatively easy

Regarding the heat capacity effect, as the bulk density of the paper scrap fuel bed increases, the heat capacity of the paper scraps also increases. This leads to a higher ignition limit for the paper scraps (1st term in Equation (2)).

When considering the oxygen supply within the porous medium, the total amount of oxygen inside the bulk porous medium decreases with increasing bulk density, which makes oxygen delivery to high-temperature regions more challenging. This significantly impacts the last term in Equation (2), as the reaction rate for heat generation is defined by:, where is the oxygen concentration in the ambient, k represents the chemical control effect, and illustrates the diffusion control effect.

Through the analysis of the experiments, we have gained a better understanding of the U-shaped trend shown in

Figure 4. In the case of low bulk density (e.g., 12 kg/m³), porosity is the dominant factor influencing thermal conductivity. A higher porosity results in lower thermal conductivity, which in turn hinders effective heat transfer from the heating element to the fuel bed. Oxygen distributions between particles reached ambient level because the pore size was much greater than the characteristic thickness of the paper in the low-density range.

As the bulk density increases, the influence of oxygen supply and heat capacity becomes more significant in the ignition process of the fuel bed. Consequently, this leads to an increase in the ignition limit of the paper scraps as the bulk density rises.

3.2. The Influence of Paper Scrap Length Within the Fuel Bed on the Ignition Limit Without External Forced Air Flow

This section primarily discusses the effects of paper scrap length within the fuel bed on the ignition limit, in the absence of externally forced air flow.

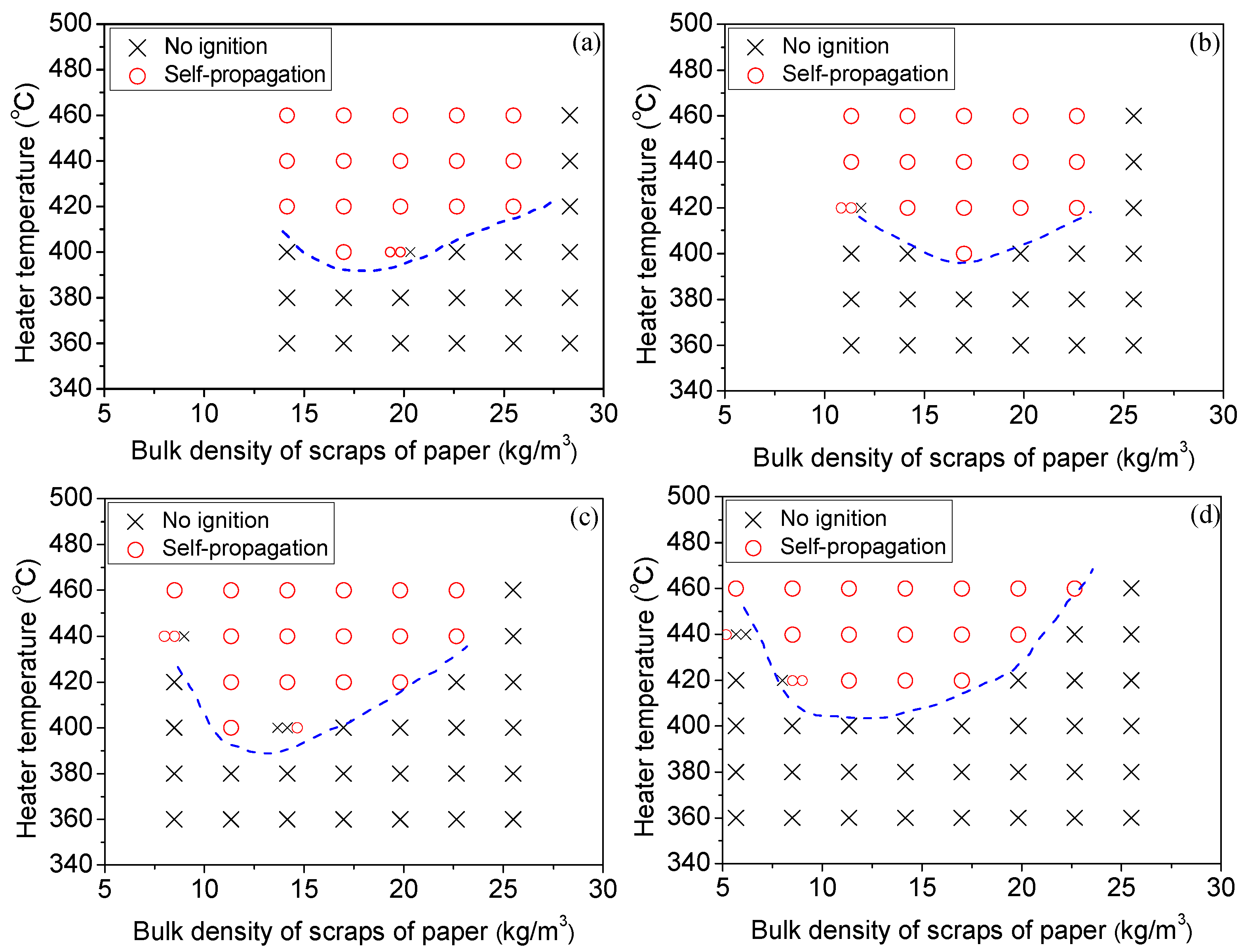

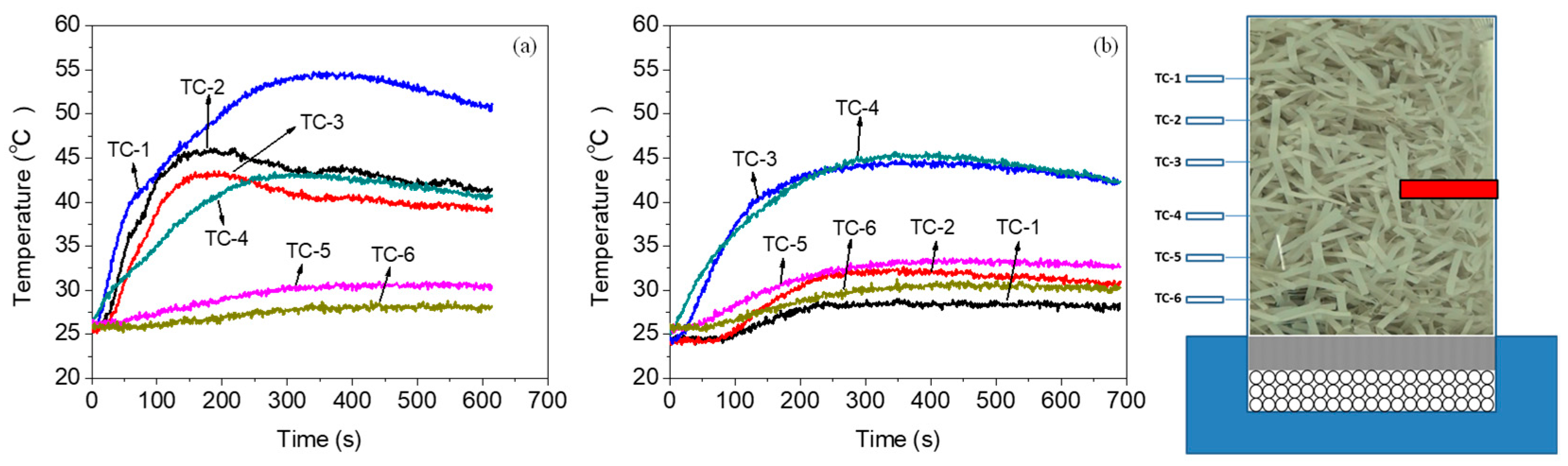

As shown in

Figure 5, the ignition limits of the paper scraps fuel bed across all tested sizes follow a U-shaped curve, which supports the accuracy of our previous analysis. The natural stacking density of small-sized paper scraps is approximately 15 kg/m³, while that of large-sized paper scraps is around 5 kg/m³. Within the low bulk density range (10–15 kg/m³), the lowest ignition temperatures for paper scraps with lengths of 45, 60, and 75 mm are 420 °C, 400 °C, and 420 °C, respectively. In this range, the effect of paper scrap length on the ignition limit is minimal. In the high bulk density range (15–25 kg/m³), for instance, at a bulk density of 16.98 kg/m³, the lowest ignition temperatures are 400 °C, 400 °C, 420 °C, and 420 °C for 30, 45, 60, and 75 mm paper scraps, respectively. At a bulk density of 19.81 kg/m³, the lowest ignition temperatures are 400 °C, 420 °C, 420 °C, and 440 °C for 30, 45, 60, and 75 mm paper scraps, respectively. At a bulk density of 22.5 kg/m³, the lowest ignition temperatures are 420 °C, 420 °C, 440 °C, and 460 °C for 30, 45, 60, and 75 mm paper scraps, respectively. Compared with low-density regions, the size of paper scraps has a more pronounced effect on the smoldering ignition limit of the fuel bed in high-density regions.

Based on the analysis of the U-shaped trend from the previous section, the smoldering ignition limit of the fuel bed in high-density regions is characterized by a larger heat capacity and limited oxygen availability in the fuel bed. This is most likely because, in high-density regions, the size of paper scraps influences the oxygen supply conditions within the fuel bed, while the heat capacity remains constant at a given bulk density. This is evidenced by the temperature distributions shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 6 illustrates the temperature distribution within the paper scraps fuel bed for two individual cases. The temperature profiles within the test sample, obtained at initial rod-heater temperatures of 400 °C and 440 °C, with paper scrap lengths of 30 mm and 75 mm at a bulk density of 14.15 kg/m³, are presented.

Figure 6a shows the temperature distribution for a paper scrap length of 30 mm, while

Figure 6b corresponds to a length of 75 mm. In both non-ignition cases, the temperatures recorded by all thermocouples remained below 100 °C. Nevertheless, a significant difference is observed between the two paper scrap lengths. For the 30 mm case, the temperatures in the upper part of the combustion chamber (TC-1 to TC-3) were higher than those in the lower part (TC-4 to TC-6). Notably, the local temperatures at TC-1 and TC-2 even exceeded that at TC-4, despite TC-4 being located closer to the rod-heater. A similar phenomenon was also reported in our previous research [

18]. This behavior can be attributed to the heat transfer characteristics within the porous medium: in addition to conduction and radiation from the rod-heater to the fuel bed, the upper region of the chamber received convective heat transfer induced by buoyancy-driven flow. Such convection played a critical role in enhancing the temperature of the paper scraps in the upper chamber. However, when the paper scrap length increased to 75 mm, this buoyancy-driven convection effect was strongly suppressed, resulting in a substantial reduction of convective heat transfer. Consequently, heat transfer was dominated by radiation and conduction, leading to higher temperatures near the heaters (TC-3 and TC-4) compared to locations farther away (TC-1, TC-2, TC-5, and TC-6). The suppression of natural convection in the fuel bed deteriorates oxygen supply, making the effect of paper scrap size on the smoldering ignition limit of the fuel bed more pronounced in high-density regions.

3.3. Ignition Limit of Paper Scraps with External Air Flow

In this section, we investigate the impact of the external air flow rate, introduced from the bottom of the fuel bed, on both the ignition limit and the smoldering propagation characteristics of the paper scraps. Given that the ignition limit in the high-density region is primarily governed by oxygen transport within the fuel bed, this part of the study focuses exclusively on the effect of air flow rate on the ignition limit of paper scraps in the high-density region.

Figure 7 shows the ignition limits of paper scraps without external airflow (

Figure 7a), with 10 NL/min external airflow rate (

Figure 7b). As discussed before, in the absence of an external air flow, the ignition limit increases when the bulk density increases from 17 kg/m

3 to 25 kg/m

3. However, at external airflow rates of 10 NL/min, the ignition limit of the paper scraps first decreases with increasing bulk density and then increases with a further increase in bulk density. Specifically, at a bulk density of 19.81 kg/m

3, the minimum initial rod-temperature required for ignition of the paper scraps without external airflow is 420 °C (

Figure 7a). In contrast, when an external airflow rate of 10 NL/min is applied, the minimum ignition temperature is significantly reduced to 380 °C (

Figure 7b). This enhanced ignition tendency with external airflow can be attributed to the increased oxygen supply to the fuel bed facilitated by the externally induced airflow.

In the presence of externally forced airflow, the ignition limit of paper scrap smoldering combustion once again exhibits a U-shaped trend with varying bulk density. Compared with the condition without forced airflow, however, the inflection point of the U-shaped curve shifts toward the higher-density region.

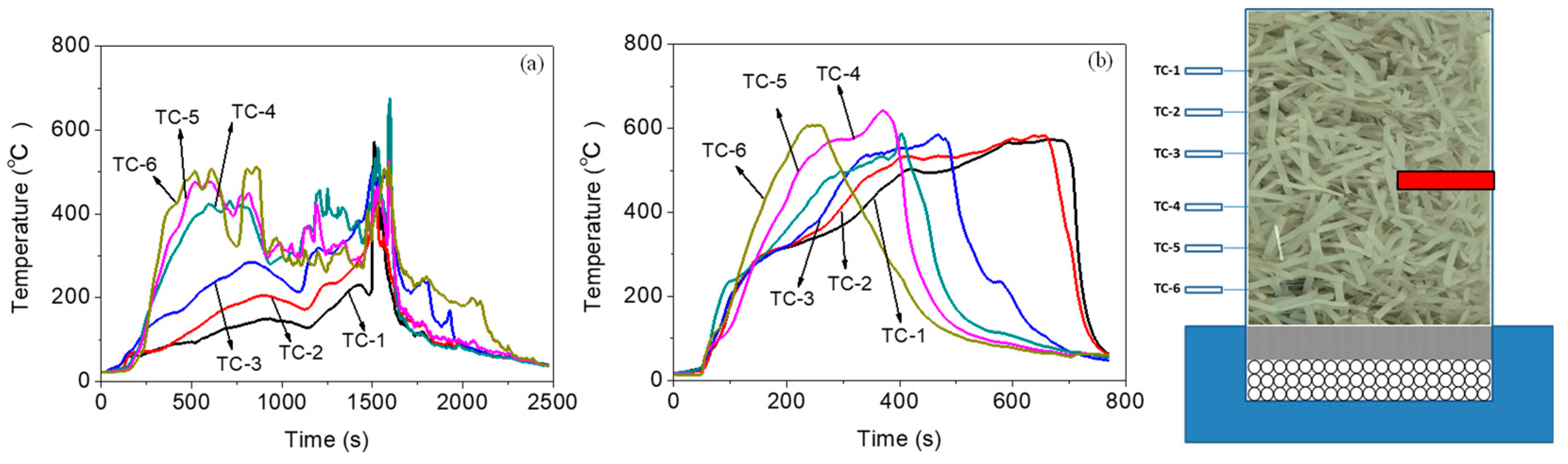

The effect of airflow on the temperature profiles in the vertical combustion chamber is presented in

Figure 8. In the absence of external airflow (

Figure 8a), the smoldering front was first detected at the bottom thermocouple (TC-6) and subsequently propagated upward, a behavior that has been previously identified and explained in detail in our earlier study [

18]. When an airflow of 30 NL/min was introduced (

Figure 8b), the smoldering front followed the same pattern but propagated at a substantially higher rate. This acceleration was attributed to the oxygen-diffusion-limited nature of the smoldering process, whereby the additional airflow enhanced oxygen availability [

19], leading to higher sample temperatures and faster front propagation.

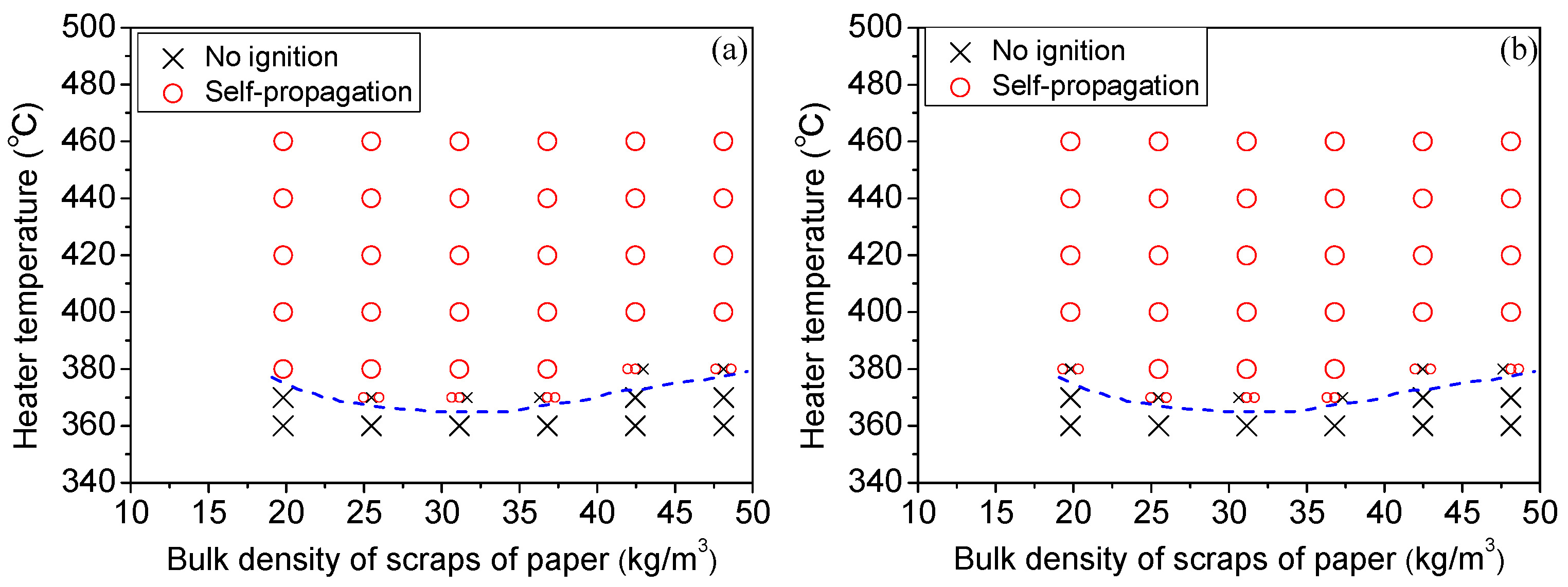

The effect of paper scrap length on the ignition limit of smoldering combustion under external airflow is presented in

Figure 9.

Figure 9a,b show the minimum temperatures required for smoldering at different bulk densities for paper scraps of 30 mm and 60 mm in length, respectively. The results indicate that increasing the paper scrap length had no significant influence on the ignition limit with the presence of external forced airflow. In particular, no appreciable rise in the minimum ignition temperature was observed with longer paper scraps under the 30 NL/min airflow conditions. This can be explained by the fact that, under forced airflow, the convective heat transfer from the rod-heater to the test sample was not hindered by the increase in scrap length.

It should be noted that in this study, the influence of longer paper scrap lengths on the ignition limit was not comprehensively examined under external airflow conditions. It is hypothesized that at greater lengths, convective heat transfer from the rod-heater to the sample may be reduced, potentially requiring higher ignition temperatures or stronger airflow to sustain smoldering. Further investigations will be carried out to clarify the effect of extended paper scrap lengths on smoldering ignition limits under forced airflow.

4. Summary and Conclusions

This paper investigates the ignition temperature and smoldering propagation characteristics of paper scrap under varying conditions, including paper scrap length, bulk density, and externally forced airflow rate. The effects of these factors on the ignition limit of the paper scrap fuel bed have been discussed. The main findings are as follows:

(1) In the absence of external airflow and with a fixed paper scrap length, the ignition limit of smoldering paper scrap exhibits a clear U-shaped trend as bulk density increases. This trend is attributed to the complex interplay between porosity, heat capacity, and oxygen supply within the fuel bed.

(2) In the absence of external airflow, the length of paper scraps had no significant effect on the ignition limit in the low bulk density range. However, in the high bulk density range, the ignition limit increased with scrap length. This phenomenon can be attributed to the suppression of natural convection within the fuel bed, which reduces oxygen supply and thereby makes the influence of scrap size on the smoldering ignition limit more pronounced under high-density conditions.

(3) In the presence of externally forced airflow, the ignition limit of paper scrap smoldering combustion once again exhibits a U-shaped trend with varying bulk density. Compared with the condition without forced airflow, however, the inflection point of the U-shaped curve shifts toward the higher-density region.

(4) Within the range of externally forced airflow rates examined in the present study, the length of paper scraps had no significant effect on the smoldering ignition limit.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, Y.D.; data curation, Z.X. and Q.H.; supervision, X.S. (Xianwen Shen); resources, H.Y.; writing—review and editing, M.Y. and X.S. (Xue Shen); methodology laboratory, J.S. and Y.T.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (Grant No. KJQN202001549, No. KJQN202101543), School-level scientific research project of Chongqing City University of Science and Technology (CKKY2024005), and the Graduate Innovation Program Project of Chongqing University of Science and Technology (YKJCX2420332).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (Grant No. KJQN202001549, No. KJQN202101543), School-level scientific research project of Chongqing City University of Science and Technology (CKKY2024005), and the Graduate Innovation Program Project of Chongqing University of Science and Technology (YKJCX2420332).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| Letters |

|

Greek symbols |

|

| V |

volume |

ρ |

bulk density |

| c |

specific heat |

λ |

thermal conductivity |

| T |

temperature |

σ |

Stefan–Boltzmann constant |

| t |

time |

ϕ |

porosity |

| S1 |

heat conduction surface from heater to test sample |

ε |

emissivity |

| d |

conduction distance |

ω |

reaction rate |

| Dp |

pore diameter in the porous |

Subscripts |

|

| Q |

heat |

h |

heater |

| C |

concentration |

ts |

test sample |

| k |

reaction rate constant |

loss |

heat loss |

| h |

mass transfer coefficient |

hr |

heat release |

| H |

reaction heat |

intrinsic |

intrinsic |

| |

O2

|

oxygen |

|

ambient |

| eff |

effective |

| air |

air |

References

- Fernandez-Anez, N.; Christensen, K.; Rein, G. Two-Dimensional Model of Smouldering Combustion Using Multi-Layer Cellular Automaton: The Role of Ignition Location and Direction of Airflow. Fire Safety Journal 2017, 91, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlemiller, T.; Lucca, D. An Experimental Comparison of Forward and Reverse Smolder Propagation in Permeable Fuel Beds. Combustion and Flame 1983, 54, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlemiller, T.J. MODELING OF SMOLDERING COMBUSTION PROPAGATION. Progress in Energy & Combustion Science 1985, s11, 277–310. [Google Scholar]

- Hadden, R.M. Smouldering and Self-Sustaining Reactions in Solids: An Experimental Approach. university of edinburgh 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, H.; Amin, R.; Heidari, M.; Kotsovinos, P.; Rein, G. Structural Hazards of Smouldering Fires in Timber Buildings. Fire Safety Journal 2023, 140, 103861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, S.V.; Rein, G.; Ellzey, J.L.; Ezekoye, O.A.; Torero, J.L. Kinetic and Fuel Property Effects on Forward Smoldering Combustion. Combustion and Flame 2000, 120, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, N.A.; Toong, T.Y.; Garris, C.A. Mechanism of Smoldering of Cellulosic Materials. Symposium (International) on Combustion 1977, 16, 1447–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torero, J.L.; Gerhard, J.I.; Martins, M.F.; Zanoni, M.A.B.; Rashwan, T.L.; Brown, J.K. Processes Defining Smouldering Combustion: Integrated Review and Synthesis. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2020, 81, 100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, B.C.; Frette, V.; Kleppe, G.; Arntzen, B.J. Onset of Smoldering in Cotton: Effects of Density. Fire Safety Journal 2011, 46, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadden, R.; Alkatib, A.; Rein, G.; Torero, J.L. Radiant Ignition of Polyurethane Foam: The Effect of Sample Size. Fire Technol 2014, 50, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Qu, Y.; Huang, X. Smoldering Fire of High-Density Cotton Bale Under Concurrent Wind. Fire Technol 2020, 56, 2241–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, D.C.; Anthenien, R.A.; Fernandez-Pello, A.C. Smolder Ignition of Polyurethane Foam: E!Ect of Oxygen Concentration. Fire Safety Journal 2000, 34, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CTIF Report. Available online: https://ctif.org/sites/default/files/2024-06/CTIF_Report29_ERG.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Stocker, D.P.; Olson, S.L.; Urban, D.L.; Torero, J.L.; Walther, D.C.; Carlos Fernande-Pello, A. Small-Scale Smoldering Combustion Experiments in Microgravity. Symposium (International) on Combustion 1996, 26, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, J.L.; Zak, C.D.; Song, J.; Fernandez-Pello, C. Smoldering Spot Ignition of Natural Fuels by a Hot Metal Particle. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 2017, 36, 3211–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Huang, X.; Chen, H.; Liu, N. Interaction between Flaming and Smouldering in Hot-Particle Ignition of Forest Fuels and Effects of Moisture and Wind. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2017, 26, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xu, J.; Wu, X.; Wang, H. Smoldering Ignition and Transition to Flaming Combustion of Pine Needle Fuel Beds: Effects of Bulk Density and Heat Supply. Fire 2024, 7, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Fujita, O. Experimental Investigation on the Smoldering Limit of Scraps of Paper Initiated by a Cylindrical Rod Heater. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 2019, 37, 4099–4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SFPE Handbook of Fire Protection Engineering; Hurley, M. J., Gottuk, D., Hall, J.R., Harada, K., Kuligowski, E., Puchovsky, M., Torero, J., Watts, J.M., Wieczorek, C., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4939-2564-3. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).