1. Introduction

Over the past decades, there has been a significant increase in steel production. In 2023 the total production of crude steel in the world has reached 1888.2 Mt [

1]. Mainly,

of this production originates from the blast furnace (BF) – basic oxygen furnace (BOF) route. BF – BOF route is associated with high

emissions, averaging about 2 tons

per ton steel. This is approximately four times higher than emissions from production with Electric Arc Furnaces (EAF) [

1]. To achieve circularity and net zero emission, future Direct Reduced Iron (DRI) based technologies will play a very important role and are being adapted for direct use of hydrogen. Scrap being an input material with lower emission is one of the solutions to mitigate

emissions. Steel scrap is used both in BOF as part of the ferrous input, and in EAF as

input material. However, introducing scrap in BOF comes with challenges, such as potentially deteriorating the final steel quality as a result of introducing unwanted tramp elements . In addition, the utilization of scrap in BOF is limited due to unavailability of external energy source to melt the scrap. Therefore, the heat cycle has to be planned carefully based on the details of the final product, hot metal, and scrap quality/composition. The heat cycle in BOF starts by charging different scrap sizes and types. Subsequently, the furnace is pivoted back and forth (rocked) to evenly distribute the scrap on the bottom of the converter and avoid the formation of scrap iceberg (scrap being above the hot metal interface) during the oxygen blowing. Before introducing the oxygen lance to refine the melt (also known as the blowing stage), the converter is tilted back to charge the hot metal. Finally, the refined crude steel is tapped for further processing (secondary steelmaking). During the blowing, large amount of heat and CO (

in post-combustion) is produced as a result of exothermic reactions. Therefore, simultaneous momentum, heat and mass (bottom stirring, scrap melting, dissolution of carbon from scrap and the exothermic reaction products) transfer phenomena prevail during the operation. From a mathematical point of view, the non-dimensional form of the momentum and energy equations introduces a group of dimensionless numbers as Reynolds (Re), Prandtl (Pr), and Nusselt (Nu) numbers (see reference [

2] chapter 13). Some of these dimensionless numbers appears in equation of changes (e.g., Re and Pr) and others in the boundary conditions (e.g. Nu). For a sphere immersed in hot metal, the dimensionless quantity (

) in Equation

1 can be used to describe both the temperature (T) and concentration (

) profiles. The dimensionless time (

) expressed as (

) (

c is the thermal or the molecular diffusivity coefficient for temperature or concentration transport respectively) also known as Fourier (

) number.

On the other hand, the moving solid-liquid interface (R) in the presence of convection, considering different densities and thermal conductivities of the scrap (

,

) and the hot metal (

,

) at the melting temperature (

) is described by the dimensionless Equation 2.

It is important to emphasize that the Stefan number

depends on the carbon concentration in scrap-hot metal system. This is because the melting temperature (

) is not a constant rather it’s a function of the carbon concentration (

) which can be obtained from the phase diagram for a given scrap composition.

Table A1 summarizes the relevant dimensionless numbers for heat and mass transfer problem.

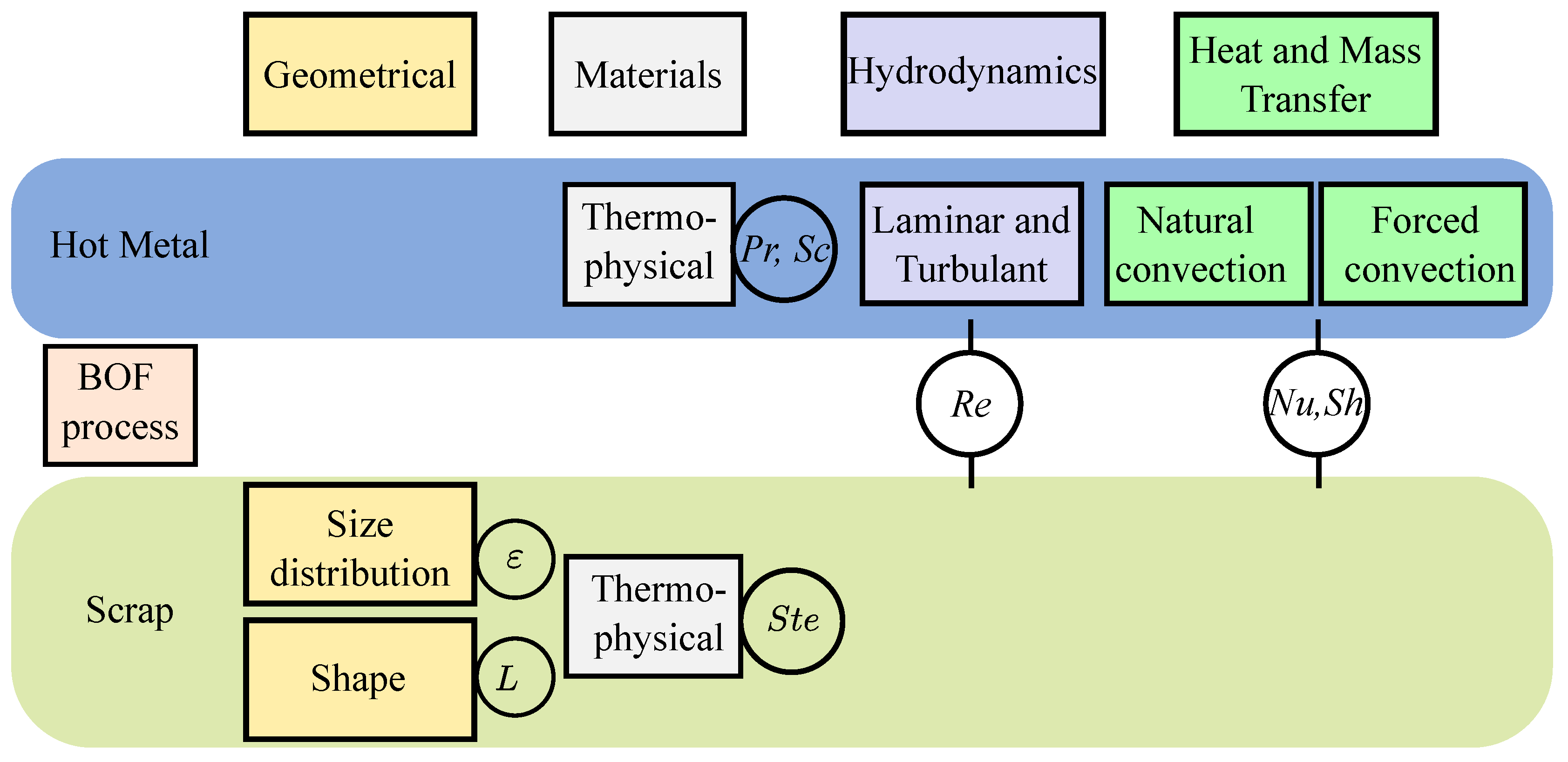

Figure 1 illustrates the source of different dimensionless numbers and their relation to scrap and hot metal in the BOF system.

The dependency of the Nu and Re numbers on the characteristic length scale (L) requires a prior knowledge of the scrap shape, which is essential for estimating their average values. Hence, estimating the average external heat transfer coefficient (h). Which quantifies the convective heat transfer per unit mass for each unit temperature in solid-fluid systems.

Due to the similarity between heat and mass transport equations, the heat (h) and mass (hm) transfer coefficients are described by analogous dimensionless correlations [

3]. While these coefficients can be analytically determined for simple systems using boundary layer approaches (e.g., flow over horizontal plate) [

4], they must be experimentally estimated for complex systems. There are various empirical and semi-empirical correlations have been developed to characterize these coefficients. These correlations are typically expressed in terms of dimensionless numbers Nu, Re and Pr or equivalently Sh, Re and Sc for mass transfer as shown in Equation 4.

It is worth mentioning, that the Prandtl number of liquid metals is very small (order of 0.01) compared to other fluids (e.g. order of 10 for water). This characteristic nature of liquid metals implies that the thermal boundary layer is larger than the momentum boundary layer. This affects the exponent of the Prandtl number in the dimensionless Equation 4. The exponent tends to be larger for fluids with low Prandtl number (e.g., liquid metal) compared to other fluids (e.g., water) [

3]. Furthermore, the temperature variation during the heat cycle (ranging between

to

) has a considerable influence on the thermophysical properties of the system [

5]. Therefore, for a steady-state flow of the hot metal over a scrap piece, the Nusselt (Nu) number depends on the characteristic length (L) of the scrap, variation of the thermophysical properties (Pr), the nature of the hot metal flow (laminar or turbulent) and the heat convection type (natural or forced).

The aforementioned transport coefficients are essential for determining the scrap melting rate in BOF steelmaking process. Inefficient heat and/or mass transfer can cause scrap agglomeration due to shell formation in a dense systems (i.e. at 0.38 dense scrap pile), leading to longer melting time [

6,

7] or unmelted scrap at the end of the tapping. Hence, caution must be taken when different sizes, shapes, and types of scrap are introduced.

To correctly quantify the melting rate of scrap with different sizes (L, and

) and types (Ste), flow characteristics (Re), temperature (Nu), and species (carbon) concentration distributions (Sh) at the local scale must be measured or predicted accurately. Different melting experiments have been performed to estimate heat, and mass transfer coefficients (e.g., Nu, and Sh) [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, these experiments are limited to simple shapes (e.g., rods, spheres), single materials type (e.g., steel, ice), and constant temperatures. Such limitations favor the use of numerical approaches to model the melting and dissolution of complex scrap shapes. There are different scales to model the current process [

17]. The scale range varies between macro (e.g., Two Fluid Model) to meso (e.g., CFD-DEM) to micro (e.g., PR-DNS) scale see reference [

18,

19] for different modeling approaches.

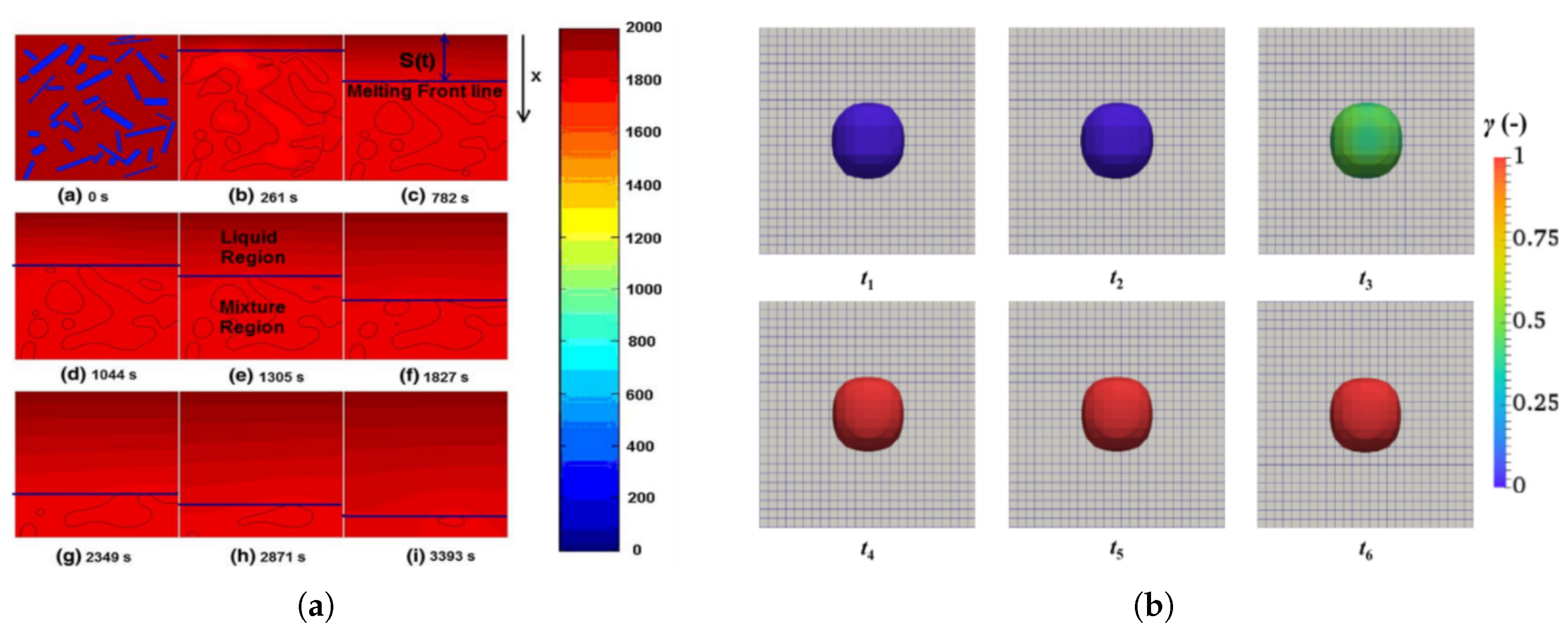

In the particulate systems, Particle Resolved Simulation (PR) has proven to be a reliable approach to capture different transport phenomena [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. However, it is computationally unfeasible for such large systems. Alternatively, particle unresolved modeling approaches such as Computational Fluid Dynamic coupled with Discrete Element Method (CFD-DEM) or Two-Fluid Model (TFM) are computationally cheaper, but they require closure relations for the multiphase mass, momentum and heat transport. In CFD-DEM approach, heat and mass transfer phenomena are evaluated using semi-empirical correlation (e.g., Gunn’s relation [

25]).

In the context of scrap-hot metal interaction, the used semi-empirical correlation should fulfill the following criteria. First, the correlation should be applicable to the operational conditions in the BOF. In other words, the correlation should be relevant within the Reynolds and Prandtl number range of the flow and temperature during the process. The flow conditions and temperature of the hot metal vary during the operation, starting at charging hot metal to gas stirring via bottom tuyeres, and to top lance blowing. It is expected that forced convective heat transfer prevails at the beginning of the hot metal charging [

26], followed by natural convection until the agitation of the hot metal bath starts using bottom tuyeres and the oxygen lance. Secondly, estimation of the Reynolds number for scrap particles, requires specification of a characteristic length of the actual scrap with a complete shape. It is worth noting that scrap size will increase at the initial time due to shell formation (solidification of the melt on the scrap) unless the scrap is preheated (to approximately

[

27]). Thirdly, the correlation should account for the influence of solid fraction of the scrap pile as it influences the heat transfer analogous to drag force in dense granular systems [

28]. Finally, it should be valid for low Prandtl number of liquid hot metal (order of

).

To understand the above mentioned criteria, relevant heat and mass transfer correlations for both natural and forced convection are listed and assessed in the next section. Furthermore, the influence of the solid fraction of the scrap bed (porosity) on the transport coefficients will be addressed. Finally, different modelling approaches with emphasis on CFD-DEM applicable to model the BOF process are outlined. Through this, the relevant existing heat and mass transfer correlations for low Prandtl numbers are reviewed and the impact of the solid fraction of the scrap bed on the transport coefficients within the CFD-DEM framework is highlighted.

2. Experimental Studies of Scrap Melting

Many experimental works found in literature investigate the melting behavior of steel scrap [

8,

12,

14]. However, these investigations are limited to a single melting object (e.g., sphere or a rod), or multiple similar objects distributed randomly [

29], or systematically [

6,

7]. Some studies use alternative materials such as water and ice (also known as cold models) [

11,

30,

31], aluminum [

32], or zinc [

10] to perform similarity analysis of the scrap melting in liquid hot metal. Some of these alternative material (e.g. cold models) offers the possibility of performing experiments with advanced measuring techniques (e.g., particle image velocimetry (PIV)) to estimate the melting rate accurately).

On the other hand, industrial-scale experiments remain scarce due to the difficulty of obtain uniform scrap input (e.g., size and shape, and composition) and experimental data during the heat cycle. Furthermore, the lack of non-invasive techniques at high temperature conditions (

) poses extra safety concerns. In the BOF, both mass and heat transfer occur during the heat cycle, and the rate of heat and mass transfer varies during the cycle as a result of the exothermic reactions [

18], as well as the stirring (and oxygen blowing) conditions of the hot metal bath [

33]. The latter defines the nature of the external heat and mass transfer processes. For a flow driven by a concentration (or density) gradient the convective heat transfer is natural. Whereas, forced convective arises when the flow results due to the action of external forces. The following sub-sections summarize the experimental studies in natural and forced convection and their corresponding correlations. While the last sub-section highlights the influence of the solid fraction in the scrap pile and its influence on the melting rate.

2.1. Melting in Presence of Natural Convection

The natural (free) convection happens due to buoyancy forces caused by density differences in the fluid [

34]. These differences are usually initiated by temperature, or concentration gradients or a combination of both.

For a heated vertical plate, these temperature gradients create density differences between the bulk fluid and the fluid near the plate surface. These differences induce buoyancy forces and lead to fluid motion. The dimensionless form of the conservation equations of mass, momentum and energy gives a set of dimensionless numbers. These dimensionless numbers are Reynolds, Prandtl and Grashof . The Grashof number represent the ratio of the buoyancy force to the viscous force. The nature of the convection is determined by the ratio of Gr and Re as following [

34]: natural convection is dominant if

, forced convection is dominant if

and mixed (combined) convection for

. From the solution of the boundary layer equations for a vertical plate, the Nusselt number (heat transfer coefficient) can be expressed as a function of Prandtl and Grashof numbers [

3,

34] as in Equation

5

Even though heat and mass transfer are similar phenomena, there is still less attention given to the strong coupled-nature of these two in the BOF. Such strong coupling is attributed to the large heat produced during oxygen blowing. As a simplification researchers tend to study these phenomena individually assuming small gradients in the neglected key variables.

Churchill [

35] developed correlation 10 given in

Table 1 for a single sphere to estimate the heat transfer coefficient for natural convection for laminar flow conditions. The correlation is valid for all ranges of Prandtl and Grashof numbers. Argyropoulos et al. [

16] conducted a similar work on liquid metals for a single sphere under natural and forced convection. Argyropoulos performed experiments on aluminum and steel spheres submerged in their respective melts. The set up consisted of a stationary melt to mimic natural convection heat transfer. Argyropoulos stated that correlation 11 showed a better fit to the experimental results compared to Churchill [

35] and Raithby [

36] correlations. However, the range of the experiments is too narrow to generalize this statement. Shell formation was observed by recording the temperature profile at the center of the sphere. The temperature profile was flat for the first 10 seconds and later started to increase, indicating the starting of the melting of the sphere. This shell formation delays the melting of the scrap, which is not favorable in BOF process. An earlier work of Ehrich et al. [

9,

37] attempted to estimate the shell size and the melting time analytically of a sphere by solving the heat transfer equations in the spherical coordinate system. The model consisted of a concentric shell and core of different materials. They were able to identify two limiting cases for such a system. First, when the thermal conductivity is equal to zero, the melting profile is linear, and no shell is formed. Second, for a high thermal conductivity (close to infinity) shell size reaches approximately

of the initial radius. Perez et al. [

38] modified the model of Ehrich to account for the variation of heat transfer coefficient and the thermophysical properties. The modified model showed larger shell sizes compared to Ehrich model. It is important to emphasize that the experimental results of Ehrich et al. did not capture the shell formation while Perez’s experiments successfully did.

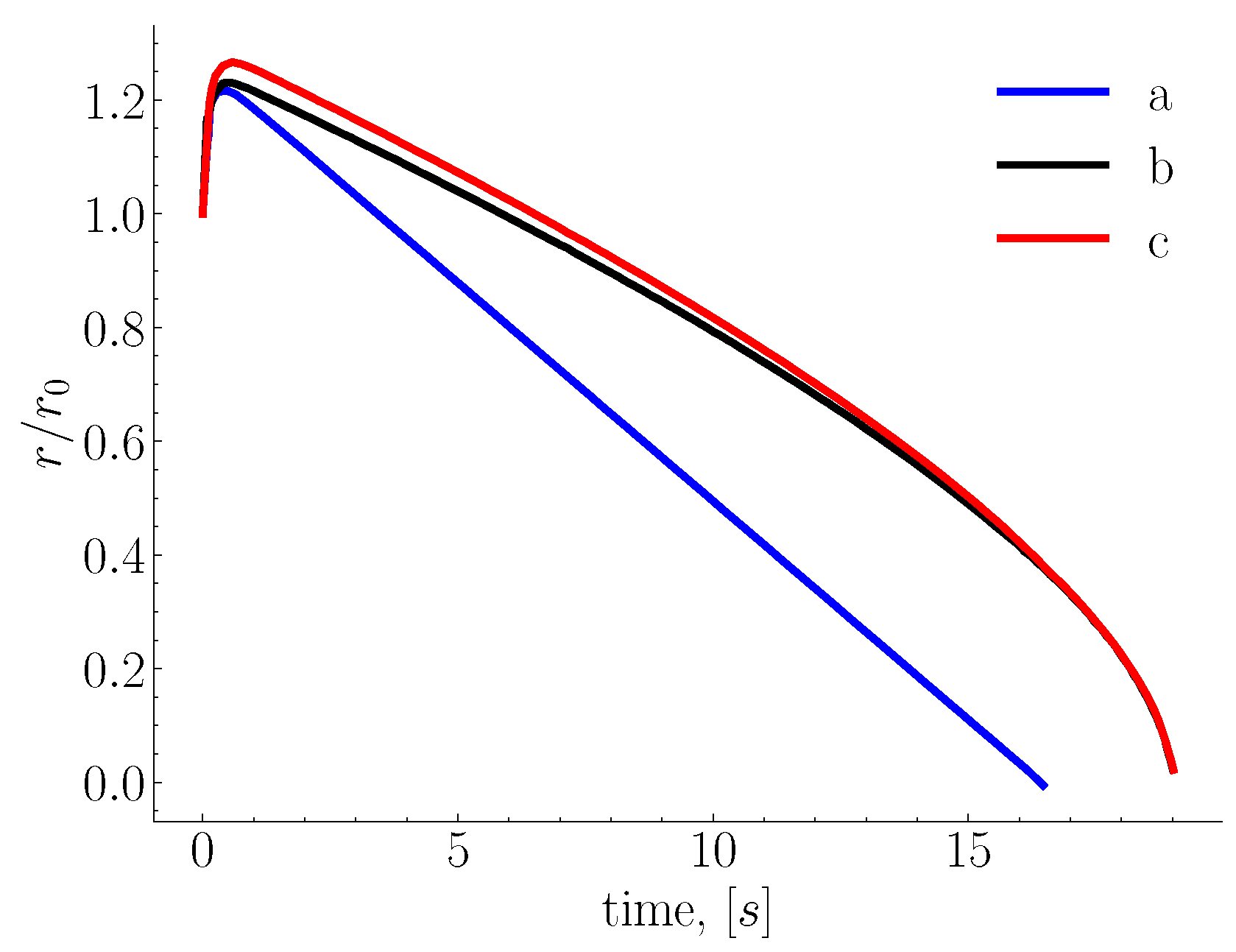

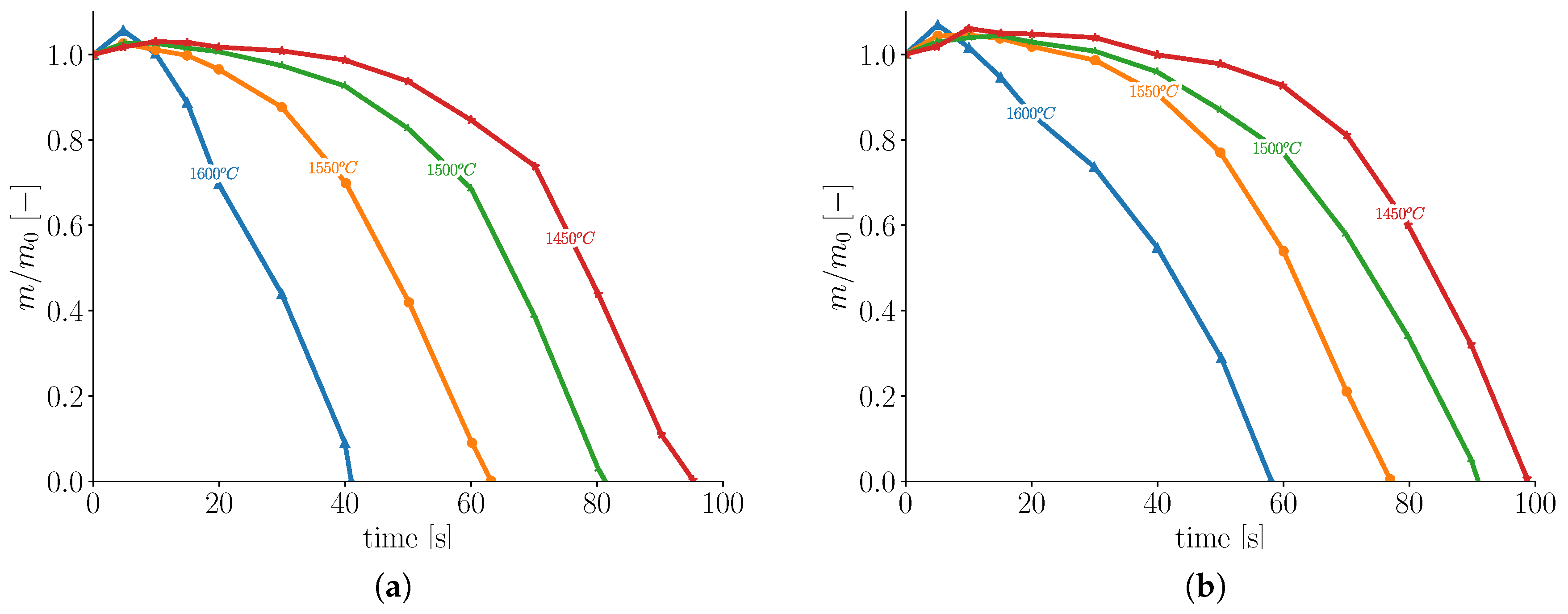

Figure 2 shows the normalized melting profile of a sphere whose initial radius is 0.975 cm. The observed increase in size is due to the shell formation, which is influenced by the temperature difference, thermophysical properties and heat transfer coefficient.

Many experiments have been conducted on single vertical rod immersed in hot metal. However, Nusselt correlations for vertical rods are obtained using approximations valid for vertical flat plate configuration [

39]. Fujii et al. [

40] used the local Nusselt number based on a vertical plate correlation to estimate the local Nusselt number for a vertical cylinder. A common method of obtaining the Nusselt number for vertical cylinders uses the thin boundary approximation as explained in reference [

41]. For a vertical cylinder in a laminar flow, the Nusselt number is given by correlation

6.

where

is the Nusselt number for a thick laminar boundary layer on a plate of the same length as the cylinder and obtained using the following correlation:

Here,

is the Nusselt for a thin boundary layer on a plate of the same length obtain from correlation

Table 1 without the term

. The parameter

is defined in Equation

8 for a cylinder of length and diameter L and D respectively.

Churchill and Chu [

42,

43] formulated a Nusselt correlation for natural convection given by Equation 12, applicable to laminar flow for a vertical plate. They indicated that the relation covers a wide range of Rayleigh and Prandtl numbers, and it can also predict the mass transfer. Subsequently, Churchill [

44] devised a general Nusselt correlation adaptable to various object shapes. The correlation aims to cover both natural and forced convection regions by taking the ratio between the Nusselt number for natural and forced convection. Churchill and Bernstein [

45] attempted to estimate the Nusselt number for a cylinder aiming to cover a wide range of Reynolds numbers (laminar and turbulent). However, they indicated that the relation is not accurate in the intermediate (transition) regime

.

Recently, Xi et al. [

46] studied experimentally the melting of cylindrical and squared steel bars. The authors did not mention the value of the heat transfer coefficient used in their experiments. Nonetheless, they investigated the influence of the initial temperature of both the melt and the steel bars on the melting. The result revealed that an increase in the initial temperature of the melt decrease the melting time of the steel bars. Hence, confirming the linear decrease of the melting time reported by Li et al. [

27]. However, the square bars showed more pronounced shell formation compared to the round bars. This is related to the high surface area of the square bars. Thus, square bars tend to have a longer melting time compared to the round bar.

Figure 3 shows mass based normalized melting profiles of both round and square bars at an initial temperature of

submerged in a bath of the same material at different temperatures.

The dissolution of steel has been also studied experimentally under isothermal temperatures [

8,

12,

47,

48]. Such studies allow the quantification of the mass transfer coefficient due to carbon diffusion from the liquid melt to the solid steel. Szekely et al. [

8] used a constant heat transfer coefficient ranging between

to study the dissolution rate of steel rods in a hot metal bath. The carbon concentration in the bath and the rods were in the range of

and

, respectively. The temperature was kept below the melting temperature of the steel rods. They showed that the rod started to melt while the bath temperature was below the melting temperature of the steel. In this case, the melting was driven by carbon diffusion into the steel rod. Additionally, shell formation was observed.

Wright [

12] used the results of iron rod dissolution in Fe-C quiescent melt to fit a Sherwood correlation

9 as a function of the Grashof and Schmidt numbers valid for

.

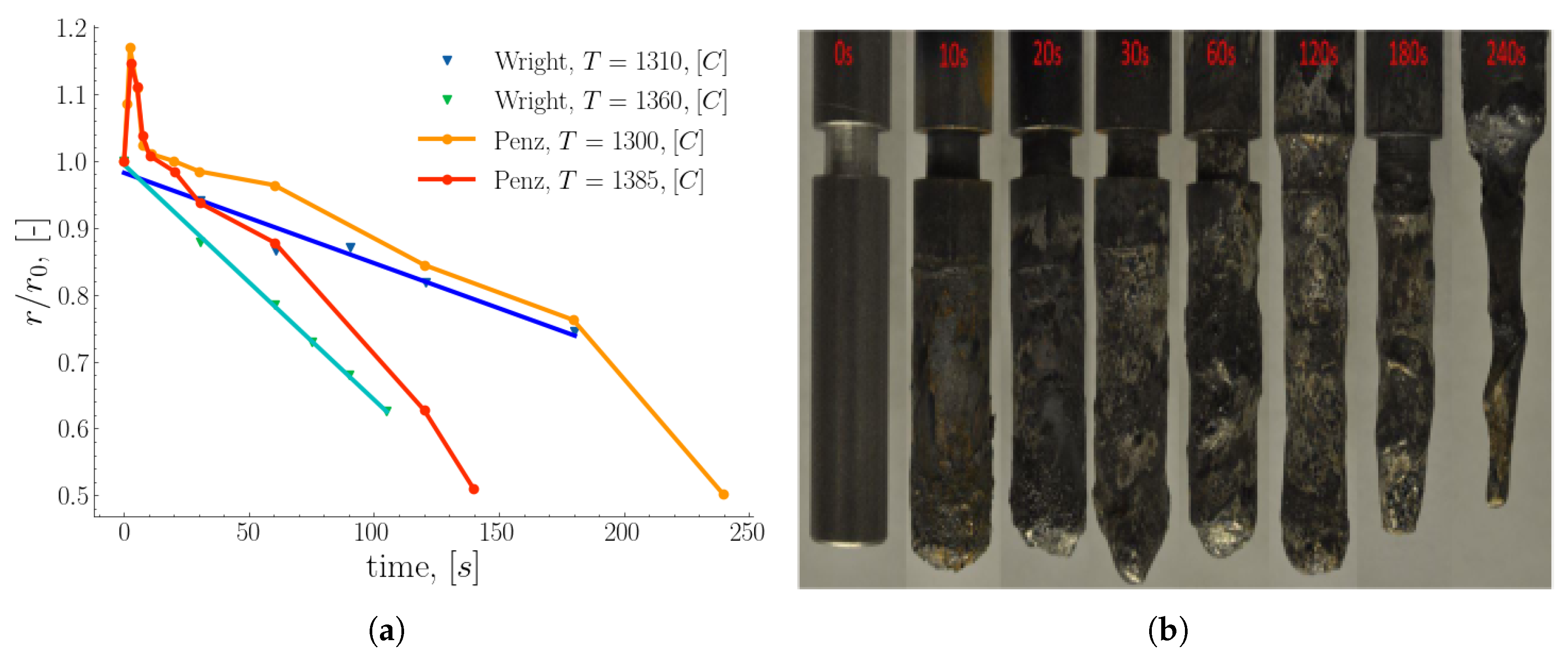

The dissolution rate of the rods was estimated from the variation of the rod diameter and the immersion time. Additionally, Wright investigated the influence of the temperature and carbon content of the melt on the dissolution rate. The result of the temperature variation shown in

Figure 4 (a) indicates an increase in the dissolution rate as a function of the melt temperature.

Penz et al. [

50,

51] studied experimentally and numerically the dissolution of steel rods in liquid hot metal driven by the concentration gradient. They investigated the dissolution rate of the steel rod in both static and rotating modes. The modes of the rod are intended to mimic natural and forced convection caused by the flow of the hot metal in the BOF process. Their study revealed that the rate of dissolution using a rotating rod is higher (approximately twice) compared to the static rod under the same conditions. Also, shell formation was observed for almost 10 seconds, concluding that the size of the shell strongly depends on the initial temperature of the rod and the melt. The maximum shell thickness was estimated to amount

of the initial radius [

49]. They estimated the mass transfer using the liquidus carbon concentration at equilibrium temperature.

Figure 4 (b) shows the distorted shape of the melted steel rods at different immersion times [

49]. In their numerical work, Penz et al. [

52] used the Nusselt correlation 13 given in

Table 1 for a vertical rod to estimate the heat transfer coefficient. They solved the heat transfer equation in cylindrical coordinates considering only the variation of the temperature in the radial direction. Their solution showed a higher heat transfer coefficient than the experimental results by a factor of 10. They associated this difference to the shell formation, and the gases trapped between the shell and the rod which reduced the external heat transfer values. Later, Deng et al. [

53] indicated that there is also an axial variation of temperature, and it is not constant as Penz et al. [

52] assumed. They mentioned that the temperature variation between the top and the bottom introduces a circulation flow between the top and the bottom of the melt. At a later time, the system reaches thermal equilibrium where this circulation flow is driven by the concentration gradient.

Table 1.

Average Nusselt correlations for natural convection for sphere, vertical plate, and vertical cylinder valid for low Prandtl number.

Table 1.

Average Nusselt correlations for natural convection for sphere, vertical plate, and vertical cylinder valid for low Prandtl number.

| Shape |

Reference |

Range |

Correlation |

| Sphere |

[35] |

,

|

(10) |

| Sphere |

[16] |

,

|

(11) |

| V.P. |

[43] |

|

(12) |

| V.C. |

[52,54] |

,

|

(13) |

2.2. Melting in Presence of Forced Convection

Forced convection heat transfer is present when the flow of the hot metal is driven by pressure difference induced by external sources. Such flows typically lead to a thinner momentum boundary layer compared to the natural convection one. In such conditions, the heat transport is dominated by the convection. One of the earlier studies to estimate the heat transfer coefficient in forced convective flows was conducted by Whitaker [

55]. Whitaker developed an empirical correlation given in Equation 14 for flow past a single sphere.

The above correlation is valid in the range of

,

and

for

,

and

respectively. Whitaker assumed constant thermophysical properties of the fluid, except for the viscosity. This means that the heat transfer coefficient is a function of the fluid viscosity at different temperatures of the system. The viscosity ratio

is estimated at the bulk fluid temperature and at the surface temperature of the sphere. Ranz-Marshall [

56] developed correlation 15 for the evaporation of single drops valid for Reynolds and Prandtl numbers in the range of

and

, respectively.

Argyropoulos et al. [

16] investigated the sensitivity of Nu correlation to low Prandtl values by fitting a semi-empirical correlation 22 to steel and aluminum experiments data for a sphere in its melt. The exponent of the Prandtl number in the correlation 22 was found to be higher than the one in Hsu, Sideman (see reference [

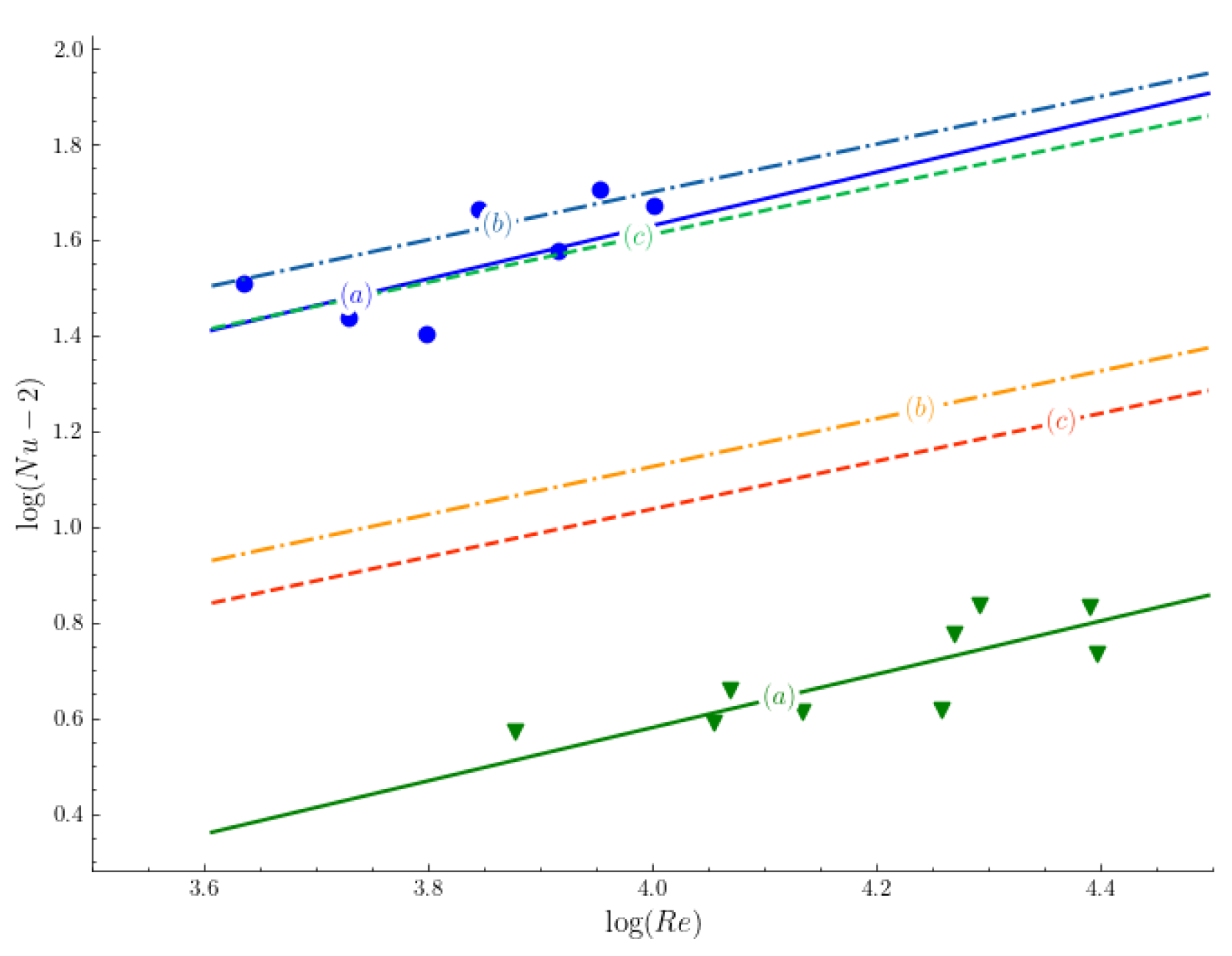

16]), Whitaker and Gunn’s correlations. It is noteworthy that correlation 22 produced a better fit when it was compared to Hsu and Sideman correlations.

Figure 5 shows the experimental results of aluminum (triangles) and steel (circles) for Sideman and Hsu correlations (lines b, and c respectively) with Argyropoulos et al. [

16] correlation (line a). In addition, Argyropoulos et al. [

32] observed shell formation, and estimated the mass increase of the sphere to be between

and

. This estimation of the shell thickness is high compared to the results of Xi et al. [

46] and Li et al. [

27]. Nonetheless, it is still within the calculated range of Ehrich et al. [

9]. Both Aziz et al. [

57] and Hao et al. [

30] did not report shell formation for ice-water system with

temperature difference and ice being at

. Melissari and Argyropoulos [

13] developed a dimensionless correlation 16 based on theoretical study for immersed sphere over a wide range (

) of low Prandtl numbers and applicable in the range of (

) for Re. The power of the Prandtl number in the correlation is still higher than Whitaker and Gunn’s but it is lower than the experimental fitted correlation 22. A direct numerical simulation was conducted by Rodriguez et al. [

58] to evaluate different theoretical and experimental based correlations.

Their simulation results revealed that correlation 22 underestimates the heat transfer coefficient while correlation 16 overestimates it. It is worth noting that Witt correlation 25 performed better than correlation 22 relative to the simulation results.

The bottom blown gas in BOF enhances the melting of scrap. This has been investigated by many researchers [

11,

31,

32,

59] in a context of heat transfer of a single sphere in a plume. Iguchi et al. [

11] investigated the influence of turbulence intensity of the flow using both water jet and bubbling gas on a single ice sphere. The results indicated high heat transfer in case of the gas plume. The reason is associated to the difference in the turbulence effect induced by the plume jet. This effect reduces the thickness of the boundary layer. Therefore, enhancing the heat transfer and increasing the Nusselt number. Iguchi modified Whitaker correlation to account for the turbulence intensity (

) by multiplying the left hand side of Equation 14 with

. Argyropoulos et al. [

32,

59] also quantified the turbulence effect of the flow using two spheres of different materials. The spheres were made of aluminum and steel and immersed in their melts. Forced convection heat transfer was induced by means of rotating the sphere and introducing argon gas plume. The results shows that the Nusselt number for the plume is higher than the rotating sphere setup. Hence, confirming the results of Iguchi et al. [

11]. The effect of shape variation during the melting on the heat transfer has an influence on the heat flux due to the variation of surface area. Hao et al. [

30] studied the effect of shape variation in ice water system using image analysis. The effect of shape variation was quantified by measuring an equivalent surface and volume particle diameters. Small variation between surface based and volume based diameter was observed at the end of the melting time. Nonetheless, the diameter profiles are identical for both surface based and volume based diameters. They developed correlation 17 to calculate the Nusselt number. However, their empirical correlation is only applicable to a narrow range of Prandtl numbers (

).

While the above studies focused on the heat transfer coefficient by estimating the Nusselt number, Wright [

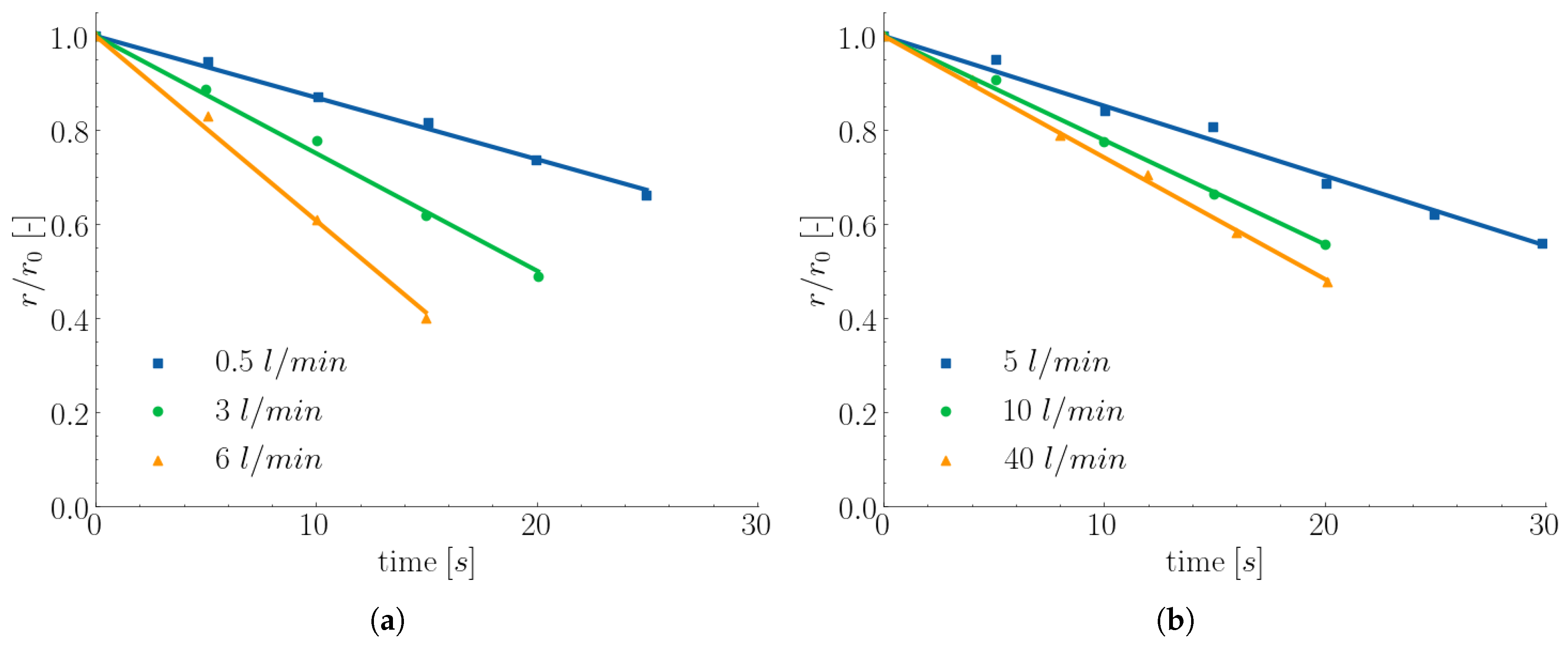

12] estimated the mass transfer coefficient for melting of steel rods in isothermal system of Fe-C melt. The melt was agitated using nitrogen gas injected at the bottom. Rods of the same radius (6 mm) and different lengths have been used in two different amount of Fe-C melt (with different furnaces capacities). This was necessary to ensure that the initial carbon concentration was not affected by the carbon dissolution into the rods. The dissolution rate under the influence of turbulent forced convection was estimated by plotting the rod diameter versus the immersion time as a function of different gas flow rates. The results revealed a linear relation between the diameter variation and the time for different gas flows, indicating a constant melting rate as shown in

Figure 6. The obtained mass transfer coefficient under forced convection was found to be depending on the gas flow rate and more precisely on the plume velocity. Furthermore, the variation of the melting rate between different curves is becoming smaller indicating that an increase of the gas flow rate above a specific flow rate will give rise to poor heat transfer as stated by Wright.

Figure 6.

Dissolution of 6 mm radius steel rods (composition:

,

, at bath Temperature

, and carbon concentration

) in different nitrogen gas flow rates in (

a) 1 kg iron bath and (

b) 25 kg iron bath [

12].

Figure 6.

Dissolution of 6 mm radius steel rods (composition:

,

, at bath Temperature

, and carbon concentration

) in different nitrogen gas flow rates in (

a) 1 kg iron bath and (

b) 25 kg iron bath [

12].

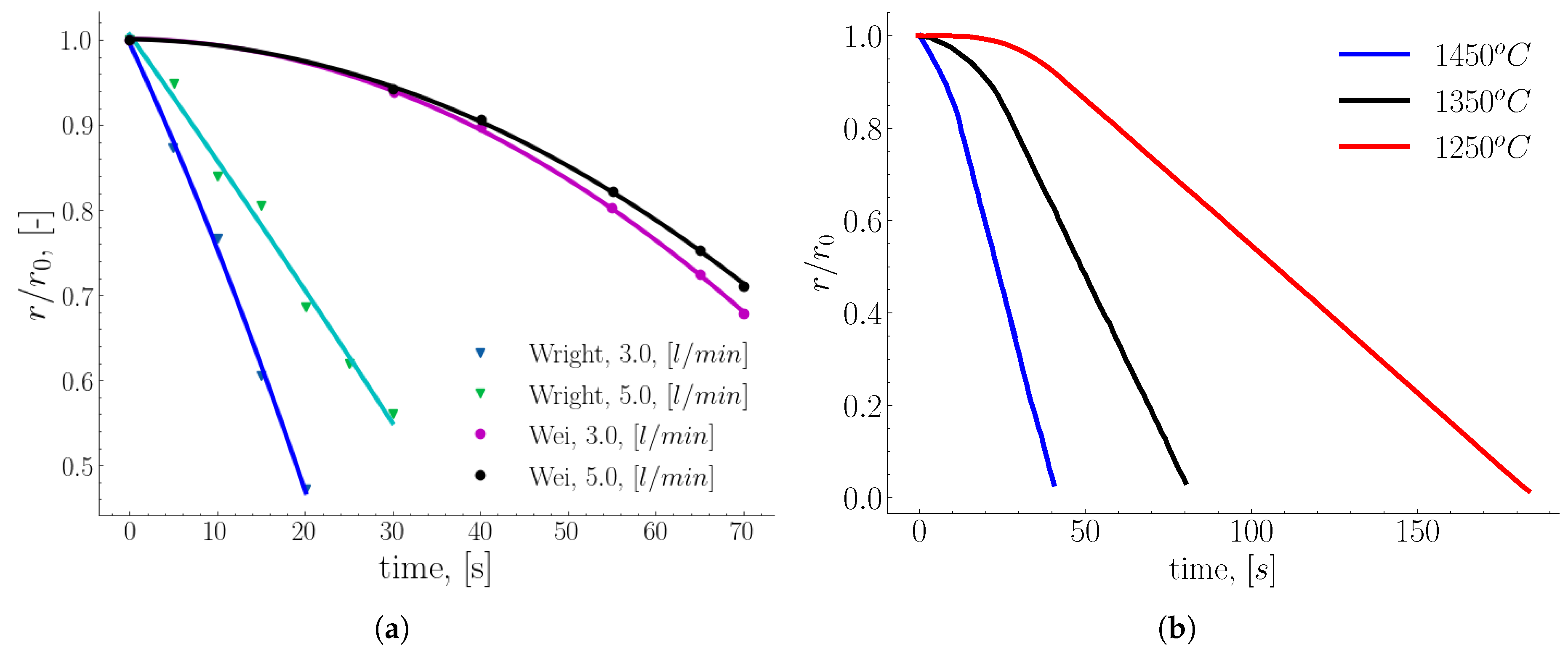

Figure 7.

Melting rods with different stirring aids (

a) rod specification: radius r0 = 6 mm, composition:

,

, bath specification

,

, stirring gas is Nitrogen [

12]. Wei’s rod specification: intial radii (

) are 10 and 25 mm, composition:

,

, and molten bath temperature

and

[

60], (

b) dimensionless melting profile of a rotating (923 rpm) carbon steel rod (radius

mm) immersed in liquid Fe-C at different molten bath temperatures [

47].

Figure 7.

Melting rods with different stirring aids (

a) rod specification: radius r0 = 6 mm, composition:

,

, bath specification

,

, stirring gas is Nitrogen [

12]. Wei’s rod specification: intial radii (

) are 10 and 25 mm, composition:

,

, and molten bath temperature

and

[

60], (

b) dimensionless melting profile of a rotating (923 rpm) carbon steel rod (radius

mm) immersed in liquid Fe-C at different molten bath temperatures [

47].

A similar study was reported by Wei et al. [

60] to estimate the dissolution of steel rods in 150 kg induction furnace. The rods were immersed in a pig iron melt of carbon content

. The melt was agitated using bottom blown nitrogen gas at different flow rates of 3, 5 and 7 l/min. The results of Wei et al. [

60] showed an increase of the dissolution rate proportional to carbon concentration gradient and the agitation intensity in accordance with the results reported by Wright [

12]. However, from a quantitative point of view, the melting profile obtained by Wei et al. [

60] shows a linear melting rate, while the results of Wright [

12] show a constant melting rate as shown in

Figure 7 (a). It is noteworthy, that the initial carbon concentration gradient for Wei et al. [

60] and Wright [

12] experiments are

and

, respectively; while the temperature of the melt for both is

. This variation in melting rate could be related to the different composition of the rods. Another study was performed by Isobe [

47] to estimate the dissolution rate of steel rods in a 5 ton converter. Isobe modified Lommel and Chalmers correlation [

61] to account for small dissolution rate as given in Equation 18.

where (

) is the moving mass transfer coefficient relative the moving interface. The melting profile of Isobe model for a single rod is shown in

Figure 7 (b). Isobe obtained a non-dimensional correlation as given in Equation 19 for a rotated rod.

Furthermore, the melting profile of the rod showed a non-linear trend for the first

of the melting time agreeing with The results of Wei et al. [

60] and linear profile for the remaining of the melting time similar to Wright [

12]. For different shapes other than spheres and cylinders, Kurobe et al. [

10] studied the melting process of a prism shape object. The cold model (ice-water) was employed to investigate the melting of a zinc ingot in a hot dip plating bath. A thermal similarity analysis was performed using two correlations applicable for liquid metals and water to estimate the Nusselt value. It is worth mentioning that the equivalent surface diameter of the prism has been chosen as the characteristic length of the prism. They indicated the importance of including the turbulence intensity in the scaling correlations as presented by Equation 20

Also, Shukla et al. [

31] performed cold model experiments on different shapes, namely, sphere, cylinder, and plate. Bottom argon gas was used to induce forced convection heat transfer. They found that the melting rate (

) is not influenced by the shape of the object in contrast to the melting time. Shukla et al. [

31] fitted a Nusselt correlation of the form

to estimate c and n coefficients for each shape individually and all shapes together. The estimated error in the coefficients for all shapes together for that shown in correlation 21 is greater than the ones obtained for the individual shapes.

This variation could be attributed to the sensitivity of the correlation to the choice of the characteristic length scale. Cao et al. [

62] used ice cured with quartz particles in 80 ton water converter. Different sizes of the cured ice (plate shape) were used to model scrap melting in the BOF. The result indicates a better mixing and heat distribution for small scrap pieces. Therefore, the study suggests to avoid large scrap pieces during BOF operation.

Table 2.

Nusselt correlations for the forced convection regime based on experimental measurements.

Table 2.

Nusselt correlations for the forced convection regime based on experimental measurements.

| Shape |

Reference |

Range |

Correlation |

| Sphere |

[16] |

,

|

(22) |

| Sphere |

[59] |

,

|

(23) |

| Sphere |

[32] |

,

|

(24) |

| Sphere |

[63] |

,

|

(25) |

2.3. Influence of Scrap Solid Fraction on The Heat Transfer in Liquid Hot Metal

An analogy exists between heat transfer and drag forces in bulk particulate systems [

18,

25,

28]. Just as drag forces can contribute to particle clustering in fluidized beds (alongside other factors such as particle-particle collisions), heat transfer processes lead to the formation of hot and cold zones within the system. Consequently, accurate prediction of heat transfer in high solid fraction systems (characterized by low voidage in scrap piles) is crucial for determining operational stability. Hot/cold zone was observed by Gaye et al. [

64] in industrial BOF experiments. They noticed that in some cases the melting time of small scrap pieces is longer than the large ones in a typical converter condition, indicating that temperature was not uniformly distributed over the different scrap pieces.

The influence of the porosity on the Nusselt correlation was indicated by Whitaker. He developed correlation (25) applicable to staggered cylinders and granular systems (e.g., packed bed). However, it is only applicable for porosity (voidage ) less than

and Prandtl number

and recommended for Reynolds number above 50.

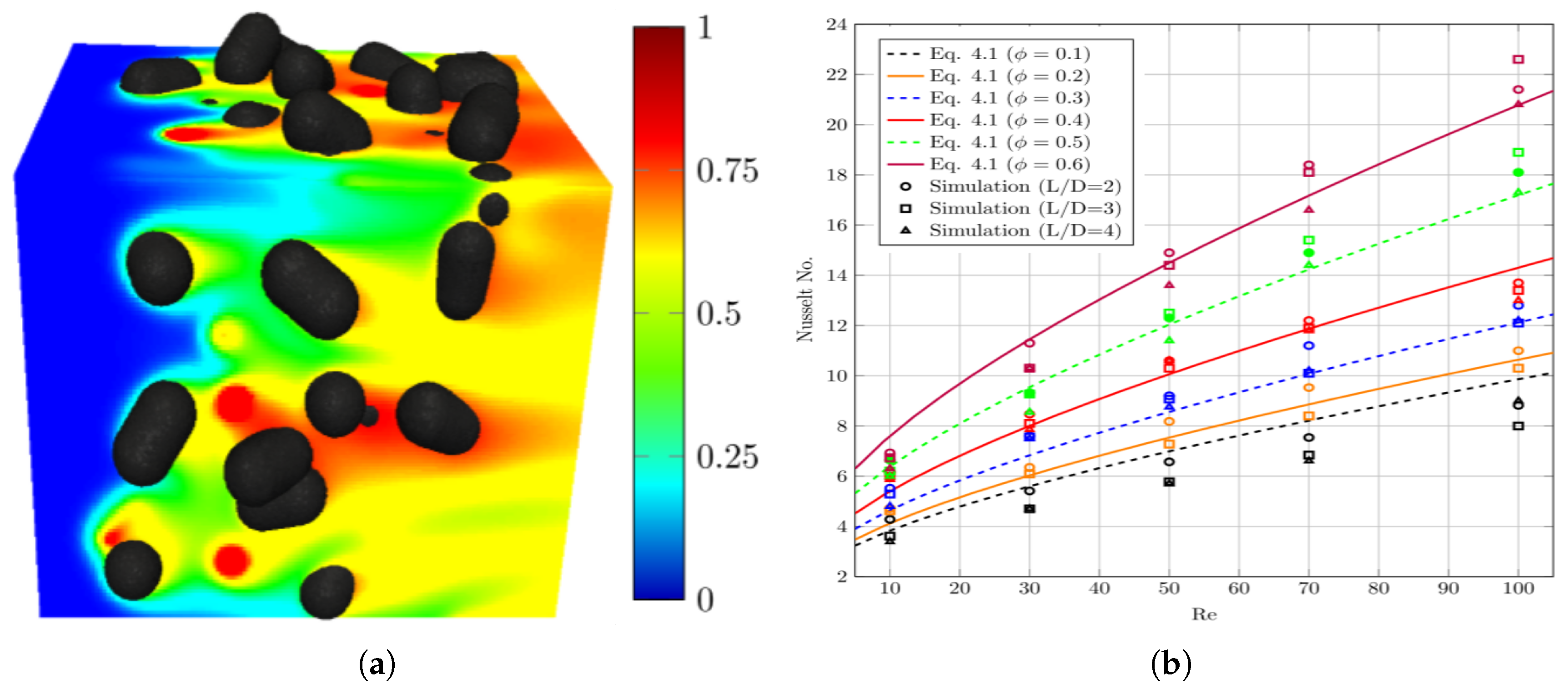

By introducing the porosity (voidage fraction

) as an independent variable in Nusselt correlation, Gunn [

25] derived one of the widely used correlations given in Equation 27 for dense systems.

where

,

,

,

,

and

. In contrast to Whitaker[

55], Gunn’s correlation is applicable to systems with a porosity range between

, and for Reynolds and Prandtl numbers, in the range of

, and

, respectively. Nonetheless, the sensitivity of Gunn’s correlation to Prandtl variation below 0.6 (e.g., in case of liquid steel) has not been quantified.

Also, Jiang et al.[

29] studied the convective melting of a spherical ice packed bed system under both gravity and microgravity conditions. Their results showed that the average Nusselt number of the bulk particle system is less compared to the single particle under identical conditions. It is worth mentioning that the heat transfer in the Jiang studies was enhanced by the convective nature of the flow.

On the other hand, the influence of the porosity in a quiescent melt on the melting dynamics has been investigated by Li et al. [

6]. They studied the melting behavior of two and multiple rods in quiescent melt. They classified the influence of the spacing between the immersed rods in hot metal into three melting categories. These categories are: (i) independent melting rods, (ii) partially agglomerate rods, and (iii) fully agglomerate melting rods. This has an important effect on the process operation, since the melting time is not determined by the melting of a single object anymore, rather by the state of the agglomerated objects. Their multi-rods experiment showed that the melting time increases non-linearly with increasing solid fraction. Similarly, Xi et al. [

7] studied the melting behavior in porous structures finding that high porosity (near 1) leads to independent melting of the objects, low porosity (below

) results in partially independent melting, and very low porosity causes fully dependent (agglomerated) melting. Their findings further confirmed the results of Li et al. [

6]. It is important to point out that in the above studies [

6,

7] the heat transport was performed under natural convection conditions, while the heat transfer in [

24,

29,

64] was convective melting driven by fluid flow. Because of the influence of porosity variation on the melting time (

t). Xi et al. [

7] developed a correlation 28 (27) to predict the melting time (

t) of multiple objects from the melting time of its single constituent (

). The correlation requires the prior knowledge of the melting time of the scrap influenced by porosity, preheating, liquid temperature, and the effect of stirring to estimate

,

,

, and

factors respectively. These factors represent the ratio of the melting time between the investigated system to single scrap under these four variations.

For the definition of these factors the reader is referred to [

7]. Although, relation 28 is developed for EAF, a similar derivation can be performed for basic oxygen furnace.

Finally, in BOF operation, both the melting rate and the melting time are important. The former is strongly influenced by material composition, state of the melt (e.g. temperature, carbon concentration), flow hydrodynamics (e.g., laminar, turbulence, stirring type) and nature of the heat and mass transfer (natural or forced). On the other hand the melting time depends on the melting rate and on the shape of the object.

Melting of single objects (e.g., sphere , rod) in quiescent melt are commonly used to study heat, mass transfer. These experiments are useful in estimating the maximum shell thickness. However, from operational perspective, the shell thickness in a scrap pile is strongly influenced by the pile porosity (solid fraction), which is very important for the stability of BOF operation. Additionally, the shell thickness depends on the Nusselt and Stefan numbers. Here, it is important to emphasize the dependency of the Stefan number on the carbon concentration. On the other hand, the selection of the correct characteristic length is crucial in estimating the heat transfer coefficient which depend on the used Nusselt correlation.

To simulate the melting of scrap, a mathematical relation for the Nusselt correlation is essential. Gunn’s correlation has been used extensively to model heat and mass transfer (especially in the field of fluidized and packed ped). For the dependence of the Stefan number on the concentration of carbon, a correlation from phase diagram can be utilized to correlate the concentration and temperature at the liquidus phase as in reference [

47][47]. However, the suitability of Gunn’s correlation for non-spherical particles and low Prandtl number, which still needs further investigation [

65,

66]. Furthermore, the shell formation in the scrap pile still needs further study. This is because there are varieties of possible shell formation scenarios e.g., individual behavior as in single object experiment, or agglomeration of few scrap pieces, or agglomeration of the whole pile, or formation of an exterior layer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Mohammed B. A. Hassan, Florian Charruault, Bapin Rout, Frank Schrama, Hans Kuipers and Yongxinag Yang; methodology, Mohammed B. A. Hassan, Florian Charruault, Bapin Rout, Frank Schrama, Hans Kuipers and Yongxinag Yang.; formal analysis, Florian Charruault; investigation, Mohammed B. A. Hassan, Florian Charruault, Bapin Rout, Frank Schrama, Hans Kuipers and Yongxinag Yang; methodology, Mohammed B. A. Hassan, Florian Charruault, Bapin Rout, Frank Schrama, Hans Kuipers and Yongxinag Yang; resources, Mohammed B. A. Hassan, Florian Charruault, Bapin Rout, Frank Schrama, Hans Kuipers and Yongxinag Yang; methodology, Mohammed B. A. Hassan, Florian Charruault, Bapin Rout, Frank Schrama, Hans Kuipers and Yongxinag Yang; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Mohammed B. A. Hassan; writing—review and editing, Mohammed B. A. Hassan, Florian Charruault, Bapin Rout, Frank Schrama, Hans Kuipers and Yongxinag Yang; visualization, Mohammed B. A. Hassan, Florian Charruault, Bapin Rout, Frank Schrama, Hans Kuipers and Yongxinag Yang.; supervision, Florian Charruault, Bapin Rout, Frank Schrama, Hans Kuipers and Yongxinag Yang; project administration, Florian Charruault, Bapin Rout, Frank Schrama, Hans Kuipers and Yongxinag Yang; funding acquisition,Florian Charruault, Bapin Rout, Frank Schrama, Hans Kuipers and Yongxinag Yang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.