1. Introduction

Ocean acidification (OA), often termed “the other CO₂ problem,” is among the most pressing environmental challenges of the twenty-first century[

1,

2]. Anthropogenic CO₂ emissions have measurably decreased ocean pH[

3,

4] ; since the onset of the Industrial Revolution, mean oceanic pH has declined by ~0.1 units[

5]. As the ocean absorbs ~25–30% of atmospheric CO₂, carbonic acid forms and marine carbonate chemistry is altered. Under current emission trajectories, ocean pH is projected to decline by a further 0.3–0.4 units by 2100[

6]. This unprecedented rate of chemical change, occurring at a pace roughly 100 times faster than background variability over the past ~20 million years, poses profound challenges for organisms and ecosystems that have evolved under relatively stable chemical conditions[

7].

Marine microorganisms—including bacteria, archaea, protists, and phytoplankton—form the foundation of oceanic food webs and drive biogeochemical cycles that regulate climate and nutrient distributions[

8,

9]. These taxa account for roughly 50% of global primary production and are integral to carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur cycling[

10,

11]. Consequently, the structural and functional responses of microbial communities to changing carbonate chemistry have far-reaching implications for ecosystem stability, fisheries productivity, and global carbon-cycle dynamics[

12,

13]. As evidence accumulates for the sensitivity of microbial processes to carbonate-system perturbations, understanding OA impacts on microbial ecology has become increasingly urgent[

14,

15].

Deciphering how OA shapes microbial life requires confronting a multi-scale, multi-stressor problem. OA–microbe interactions are modulated by chemical, biological, and ecological processes that span spatial and temporal scales[

16,

17]. Perturbations in pH and carbonate chemistry can directly affect microbial physiology, influencing processes such as calcification in coccolithophores, nitrogen fixation in diazotrophs, and taxon-specific metabolic rates[

18,

19,

20]. At the cellular level, shifts in pH and carbonate-ion availability affect membrane stability, enzyme kinetics, and metabolic pathways, while altered CO₂ levels modulate carbon-fixation strategies and energy allocation. Community-level responses include changes in species composition, competitive interactions, and functional diversity that cascade through food webs and reshape ecosystem services [

21,

22,

23]. These responses frequently co-occur with other climate-related stressors—warming, nutrient-regime shifts, and deoxygenation—creating multiple-stressor contexts that challenge single-factor experimental designs[

24,

25,

26].

Research in this field has expanded rapidly over the past two decades, encompassing laboratory experiments, mesocosm studies, field observations, and modeling approaches[

27,

28,

29]. Investigations have addressed effects on individual microbial taxa, community-level responses, and ecosystem-scale consequences across diverse marine environments, from polar systems to tropical coral reefs[

27,

30,

31]. This growth has produced a large, cross-disciplinary literature that creates opportunities for synthesis but also challenges for identifying critical knowledge gaps. Given the complexity of microbial responses to OA and the intrinsically interdisciplinary nature of this topic, a comprehensive, field-specific synthesis is warranted[

32]. However, no dedicated bibliometric review focused on OA impacts on microbial ecology currently exists, limiting insight into collaboration patterns, conceptual shifts, and emerging priorities.

Bibliometric analysis provides a rigorous framework for characterizing the evolution, structure, and trends of scientific domains by examining publication trajectories, citation networks, co-authorship, and keyword co-occurrence[

33]. CiteSpace, a widely used visualization platform, enables mapping of knowledge domains and detection of emerging topics through network and temporal analyses[

34]. CiteSpace, a widely used visualization platform, enables mapping of knowledge domains and detection of emerging topics through network and temporal analyses[

35,

36]. Wang et al. analyzed climate-change adaptation research (1981–2016) and identified “vulnerability” as a core theme, with emphasis shifting from ecosystem adaptation to social dimensions such as risk management and the resilience of public and socio-economic systems[

37]. Similarly, Zhou et al. assessed 3,344 Web of Science records on marine microplastics, showing a transition of research hotspots from marine debris to microplastics—and more recently to nanoplastics—with ecotoxicological effects and health risks emerging as focal topics [

38]. Despite these advances, OA–microbe interactions have received limited bibliometric attention, even though they are central to anticipating ecosystem responses to global change. Mapping this literature can elucidate cross-institutional networks, delineate key knowledge clusters, and highlight emerging frontiers in marine microbial science[

39,

40]; moreover, understanding the bibliometric characteristics of this domain can inform research prioritization and policy development.

The present study addresses this knowledge gap by conducting a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of global research on OA impacts on microbial ecology, spanning the period from 2005 to 2025. This study addresses critical gaps through a comprehensive bibliometric investigation: (1) Historical trajectory analysis: Reconstructing the evolution of OA and microbial ecology research since 2005 through citation network mining and publication trend analysis. (2) Knowledge domain mapping: Identifying core research clusters and emerging frontiers using keyword co-occurrence, author collaboration networks, and institutional partnership analysis. (3) Future directions synthesis: Integrating temporal trend analysis with thematic evolution patterns to anticipate next-generation research paradigms in acidification-microbial interaction. By quantitatively mapping the knowledge domain, this study provides a comprehensive overview of what has been accomplished in this critical research area. It illuminates the collaborative structures, key research fronts, and conceptual shifts that have defined its progress, ultimately offering a data-driven perspective on strategic directions for future research.

2. Data and Methodology

2.1. Data Source and Retrieval Strategy

The bibliometric analysis was conducted using the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection database, selected for its comprehensive coverage of high-quality peer-reviewed literature and standardized bibliographic information essential for advanced bibliometric analyses[

41]. The Web of Science database provides consistent metadata across multiple disciplines and time periods, ensuring reliable identification of citation relationships, author affiliations, and journal classifications necessary for network construction and temporal evolution tracking[

42].

The literature search strategy was designed to capture research publications specifically addressing the intersection of OA and microbial ecology, while maintaining sufficient specificity to exclude tangentially related studies. Since WoS records show that the first manuscript involving the “Effect of Ocean Acidification on Microbial Ecology” was published in 2005[

5], we limited the scope of the study from 2005 to 2025. To ensure retrieval completeness and precision, the search strategy incorporated controlled vocabulary and natural language terms related to “ocean acidification” and “microbial ecology”, with the Boolean search query being iteratively refined through scope validation protocols as follows:

TI=("ocean acidification" OR "seawater acidification") AND TS=("microb*" OR "plankton" OR "phytoplankton" OR "bacterioplankton" OR "coccolithophore*" OR "cyanobacteria" OR "diatom*" OR "microbial community")

Duplicates were removed via CiteSpace's built-in deduplicator. Three independent reviewers assessed title/abstract relevance using the inclusion/exclusion criteria: (1) Document types: Articles, reviews, conference proceedings. (2) Language: English-only. (3) Subject filters: Marine & freshwater biology, environmental sciences, oceanography, microbiology, ecology, etc. (4) Exclusions: Totally irrelevant fields such as freshwater acidification, terrestrial soil chemistry, biomedical engineering, and studies focusing exclusively on macro-organisms without microbial components. After manual screening and deduplication, we ultimately obtained 495 articles related to OA impacts on microbial ecology as valid articles, which were then exported in the "RefWorks" plain text format with full metadata. The exported literature covers 20 years and records the emergence, expansion and maturity stages of marine acidification studies.

2.2. Bibliometric Analysis Framework

The bibliometric analysis employed CiteSpace version 6.3.R3 Advanced, a specialized software platform designed for visualizing and analyzing patterns in scientific literature through network-based approaches[

43]. CiteSpace was selected for its advanced capabilities in handling large bibliographic datasets, constructing multiple types of citation networks, and providing temporal visualization of research evolution patterns. The software's ability to integrate multiple analytical approaches within a unified framework enables comprehensive examination of research landscapes from complementary perspectives[

44].

The analysis proceeded through four primary modules: (1) Co-citation Network Analysis: Mapping relationships among frequently co-cited references, authors, and journals to reveal the intellectual backbone of the field; (2) Keyword Co-occurrence and Clustering: Identifying dominant research themes, their interconnections, and temporal evolution; (3) Collaboration Network Analysis: Examining the geographic, institutional, and author-level structure of scientific cooperation. (4) Citation Burst Detection: Detecting terms and references that have experienced sudden increases in attention, signaling research frontiers or paradigm shifts.

The analytical process was carried out in several sequential steps. First, a new CiteSpace project was created, and the complete records and cited reference data retrieved from the Web of Science Core Collection were imported into the workspace. Second, the relevant parameters were configured, including setting the time slicing to one-year intervals, with results from individual years subsequently merged to form an integrated view. Node types for analysis—such as author, keyword, journal, category, institution, country, and cited reference—were selected according to the specific research questions. For keyword and author visualizations, functions such as co-occurrence mapping, clustering, and burst detection were applied to reveal dominant thematic areas, track their evolution over time, and detect research hotspots. Likewise, author, institution, and country co-occurrence networks were constructed to map patterns of scholarly collaboration, with thresholds and pruning methods adjusted to highlight the most influential actors and partnerships.

Finally, through incorporating CiteSpace's Modularity (Q-value) and Silhouette (S-value) indicators, along with insights from citation bursts and cluster label interpretations, we conduct a detailed examination of node magnitude, linkage density, and key standout features in the visualization. This approach not only clarifies connections and intersections across various research themes but also uncovers emergent research hotspots and future directions through highly cited keywords or publications[

45]. By comparing these visual representations both longitudinally and transversely, this study examines the status and evolutionary trajectory of OA and microbial ecology research from the angles of cooperative networks, disciplinary scope, journal distribution, and keyword evolution, thereby offering valuable support for further studies or theoretical expansions.

2.3. Quality Assessment and Validation

Multiple quality assessment measures were implemented to ensure the reliability and validity of bibliometric results. Network modularity (Q-values) and mean silhouette scores (S-values) were calculated for all clustering analyses to assess the coherence and distinctiveness of identified research clusters. Modularity values above 0.3 indicate meaningful community structure, while silhouette scores above 0.7 suggest high cluster quality and internal consistency.

The temporal stability of identified patterns was assessed through sensitivity analysis, examining how changes in parameter settings or time windows affect core findings. Cross-validation procedures compared results obtained through different analytical approaches, ensuring that major conclusions remain consistent across multiple methodological perspectives. Manual verification of high-impact nodes and clusters was conducted to confirm that automated procedures accurately identified key research contributions and collaborative relationships.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Publications and Annual Growth

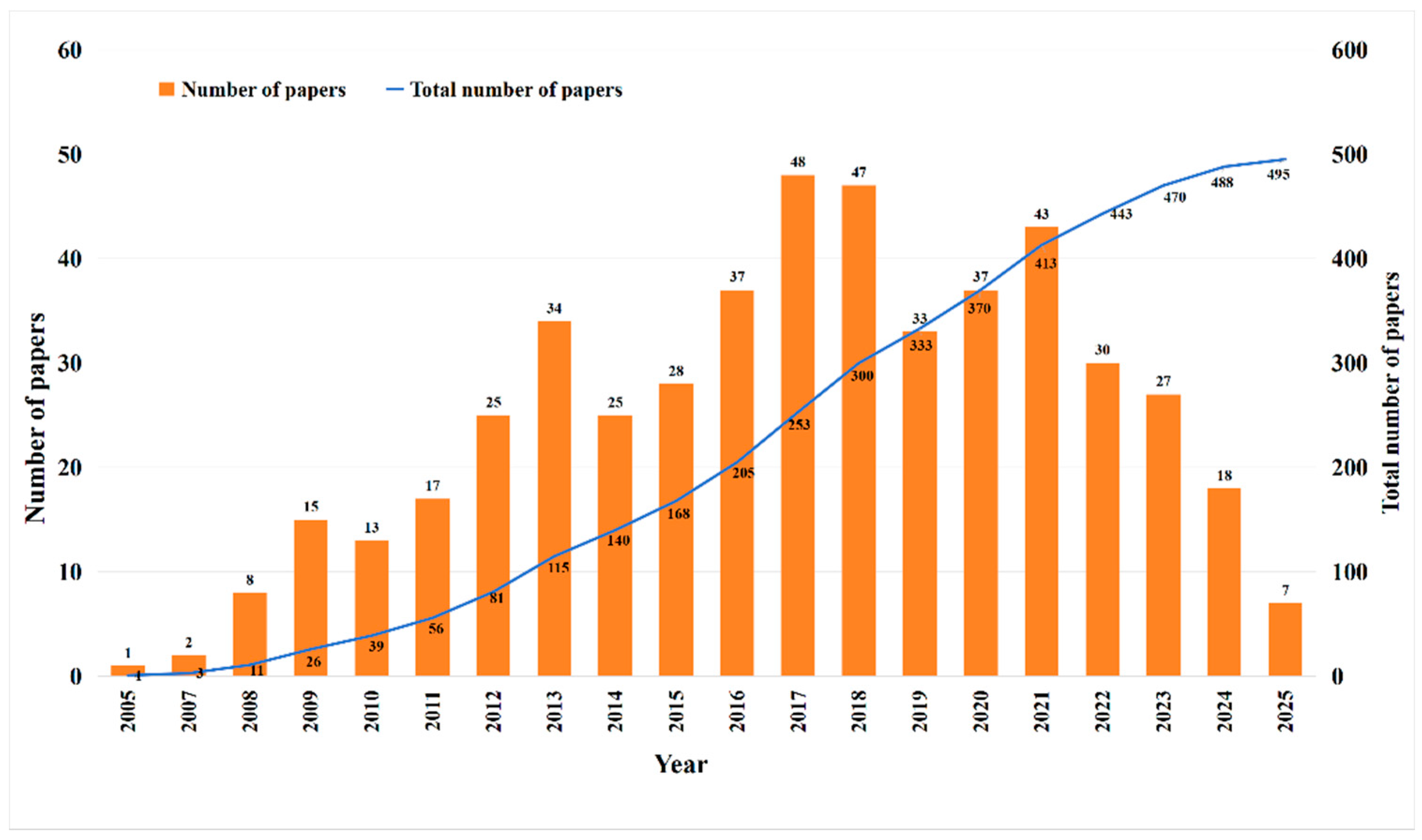

The temporal distribution of publications in OA and microbial ecology research exhibits a distinctive evolutionary pattern characterized by exponential growth, maturation, and recent stabilization phases spanning two decades (Fig.1). The initial emergence phase (2005-2010) demonstrates the field's nascent stage, with publication numbers remaining consistently low, ranging from 1-15 papers annually and a cumulative total reaching only 56 papers by 2011. This period represents the foundational years when OA research was establishing its conceptual framework and methodological approaches, with limited but steady scholarly interest reflected in the gradual accumulation of research contributions[

3]. For example, Breitbarth et al. observed through the Mid-Universe experiment that surface seawater acidification led to increased iron bioavailability[

46]. The modest publication volume during these early years aligns with the typical pattern of emerging scientific disciplines, where initial investigations focus on establishing basic principles and experimental protocols rather than generating large volumes of empirical studies. At this stage, the potential of microorganisms to adapt to OA, whether through genetic changes at the species level or species succession at the community level, is unknown. Therefore, it is necessary to elucidate the effects of OA on key species and microbial diversity[

16].

Figure 1.

Number of articles published per year from 2005 to 2025.

Figure 1.

Number of articles published per year from 2005 to 2025.

The explosive growth phase (2011-2021) reveals the field's rapid expansion and increasing scientific recognition, with annual publication volumes demonstrating remarkable acceleration from 17 papers in 2011 to peak production of 48 papers in 2017. This exponential increase in research output, reflected in the cumulative total rising from 56 papers in 2011 to 413 papers by 2021, indicates the field's transition from a specialized niche to a mainstream research area within marine science. At this time, this phase of research has been extensively studied in various oceans around the world, with Hancock et al. showing that OA has a negative impact on autotrophs in the Southern Ocean[

47], while Wang's research in the Arctic Ocean showed that OA significantly changed the functional gene structure and evenness of the Arctic Ocean bacterioplankton community[

27]. The results of an in-situ short-term microscopic experiment in the South China Sea show that plankton communities in this subtropical coastal waters are insensitive to OA in terms of primary production and nutrient transfer from phytoplankton to zooplankton[

48]. The peak production years of 2017-2018 (48 and 47 papers respectively) suggest optimal research momentum, likely driven by increased funding availability, growing environmental awareness, and the establishment of standardized experimental methodologies that enabled more researchers to contribute meaningful investigations. The effects of OA and multiple stressors on microorganisms have also attracted widespread attention, and OA, combined with warming and deoxygenation, has been shown to stimulate production in primary producers[

17]. The sustained high productivity during this period, with the cumulative curve showing consistent steep ascent, demonstrates the field's successful integration into broader climate change and marine ecology research communities.

The recent stabilization phase (2022-2025) shows signs of field maturation, with annual publication volumes declining from the peak levels to approximately 18-30 papers per year, while the cumulative total approaches 495 papers by 2025. This stabilization pattern, characterized by the flattening cumulative curve and reduced annual variability, suggests that the field has entered a consolidation phase where research efforts are focusing on refining existing knowledge rather than rapid expansion. The decline in annual publications from 37 papers in 2020 to 18 papers in 2024 may reflect several factors including research saturation in certain areas, shift toward more comprehensive long-term studies, or redirection of research priorities toward specific applications and ecosystem-scale investigations[

49]. This temporal evolution demonstrates the natural progression of scientific disciplines from explosive growth phases to more focused, specialized investigation periods, indicating that OA and microbial ecology research has achieved sufficient maturity to support sustained, targeted scientific inquiry[

50].

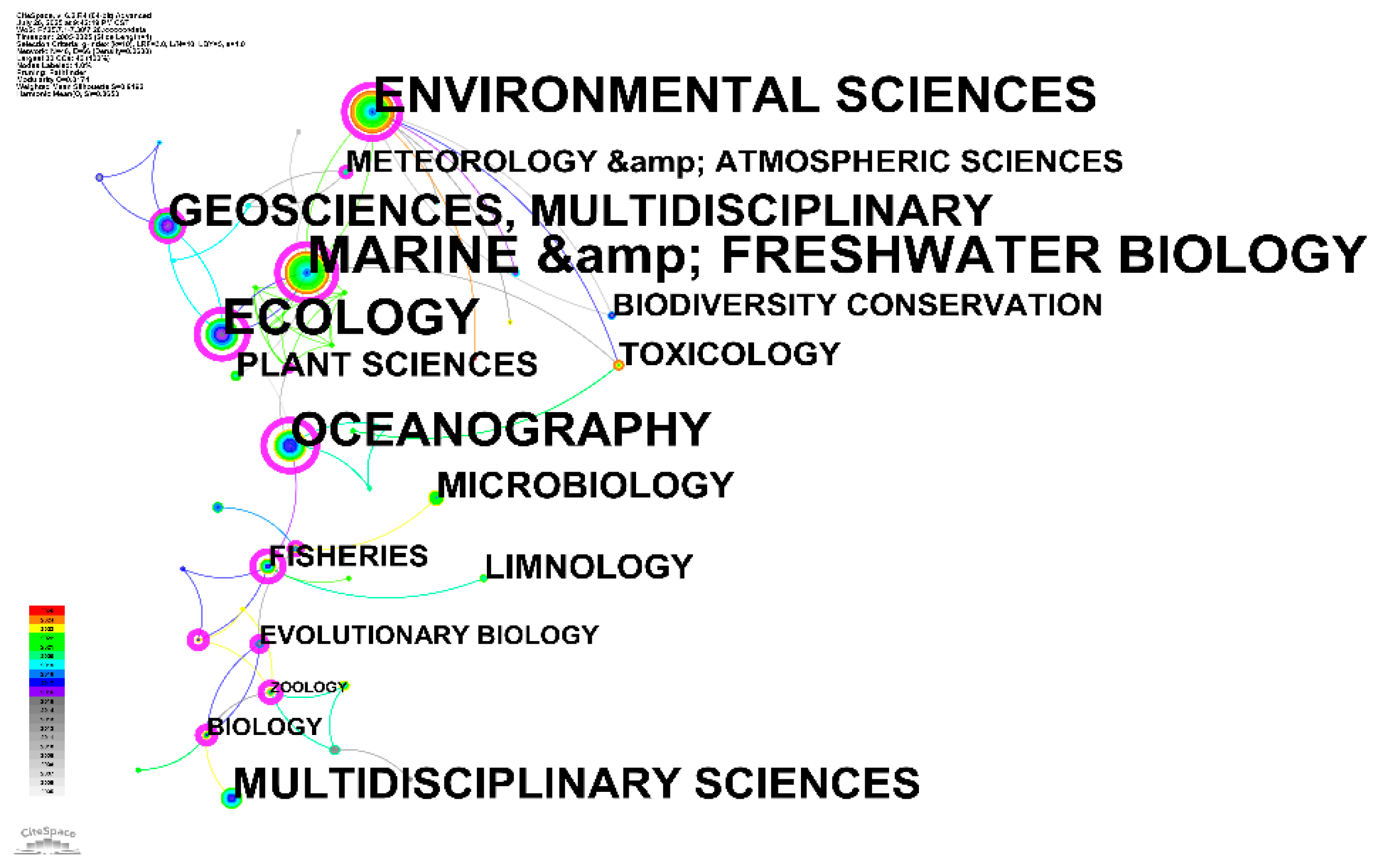

3.2. The Interdisciplinary Character of the Field

In order to further reveal the discipline structure and cross-convergence characteristics of the study of "the impact of OA on microbial ecology", this study used CiteSpace (v6.3.R3 Advanced) to construct a co-cited network map based on Web of Science Categories (Fig.2)。The discipline co-citation network analysis provides crucial insights into the interdisciplinary landscape and knowledge structure underlying OA and microbial ecology research. The visualization reveals a complex network of scientific disciplines that collectively contribute to understanding the multifaceted impacts of OA on marine microbial communities. The network demonstrates that OA and microbial ecology research is fundamentally anchored by several core disciplines. “Environmental Sciences” occupies the most prominent position in the network, reflecting its central role as an integrative discipline that synthesizes knowledge from multiple scientific domains. This positioning indicates that OA research is increasingly viewed through an environmental science lens, emphasizing ecosystem-level processes and human-environment interactions[

51].

Oceanography represents another foundational discipline, positioned strategically within the network to bridge physical and biological sciences. The prominence of oceanography reflects the fundamental importance of understanding ocean physics, chemistry, and circulation patterns in acidification research[

52,

53]. This discipline provides essential knowledge regarding carbonate chemistry dynamics, pH variability, and the spatial-temporal patterns of acidification across different ocean basins[

54,

55,

56]. The substantial presence of “Marine & Freshwater Biology” indicates the field's strong biological foundation, encompassing research on organism-level responses, community dynamics, and ecosystem functioning[

57,

58]. The connection between marine and freshwater biology suggests that acidification research extends beyond oceanic systems to include coastal and estuarine environments where freshwater-marine interaction create complex pH gradients[

59,

60].

Figure 2.

Co-occurrence network diagram for the subject area of acidification-microbial interaction.

Figure 2.

Co-occurrence network diagram for the subject area of acidification-microbial interaction.

The network structure reveals sophisticated patterns of disciplinary integration. “geosciences”, “multidisciplinary” serves as a critical bridging discipline, connecting earth system science approaches with biological and chemical perspectives[

61]. This positioning reflects the recognition that OA represents a global geochemical perturbation requiring earth system-level understanding[

62]. “Ecology” node occupies a central position within the biological sciences cluster, indicating its role in organizing knowledge about community-level and ecosystem-level responses to acidification. The strong connections between ecology and other biological disciplines suggest that ecological theory provides important conceptual frameworks for understanding how acidification cascades through marine food webs and alters ecosystem functioning[

63,

64]. The presence of “MICROBIOLOGY” as a distinct discipline highlights the specialized knowledge domain focused specifically on microbial responses to environmental change. Zhou et al. conducted manipulative experiments to assess the physiological and metabolic responses of nitrifying bacteria to OA under perturbations from anthropogenic nitrogen inputs. The results indicate that increased ammonium loading in estuarine and coastal waters mitigated the inhibitory effect of acidification on nitrification rates; however, oxidation of hydroxylamine by nitrifying bacteria enhanced the production of nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas, thereby potentially accelerating global climate change[

65]. Its positioning within the broader biological sciences network indicates successful integration of microbiological research with community ecology and ecosystem science approaches[

16].

The network structure demonstrates successful interdisciplinary synthesis, with multiple pathways connecting different knowledge domains. The positioning of “multidisciplinary Sciences” node at the periphery but with clear connections to core disciplines indicates the field's success in developing integrative approaches that transcend traditional disciplinary boundaries. “Limnology” appears as a specialized aquatic science discipline, contributing expertise on freshwater and coastal systems where acidification may interact with other environmental stressors. The presence of “Meteorology & Atmospheric Sciences” reflects the atmospheric component of the carbon cycle and the role of atmospheric CO₂ in driving acidification processes[

66,

67]. The discipline co-citation analysis demonstrates that OA and microbial ecology research represents a successful model of interdisciplinary environmental science, characterized by effective integration of diverse knowledge domains, strong connections between basic and applied research, and clear pathways for translating scientific knowledge into environmental solutions and policy applications.

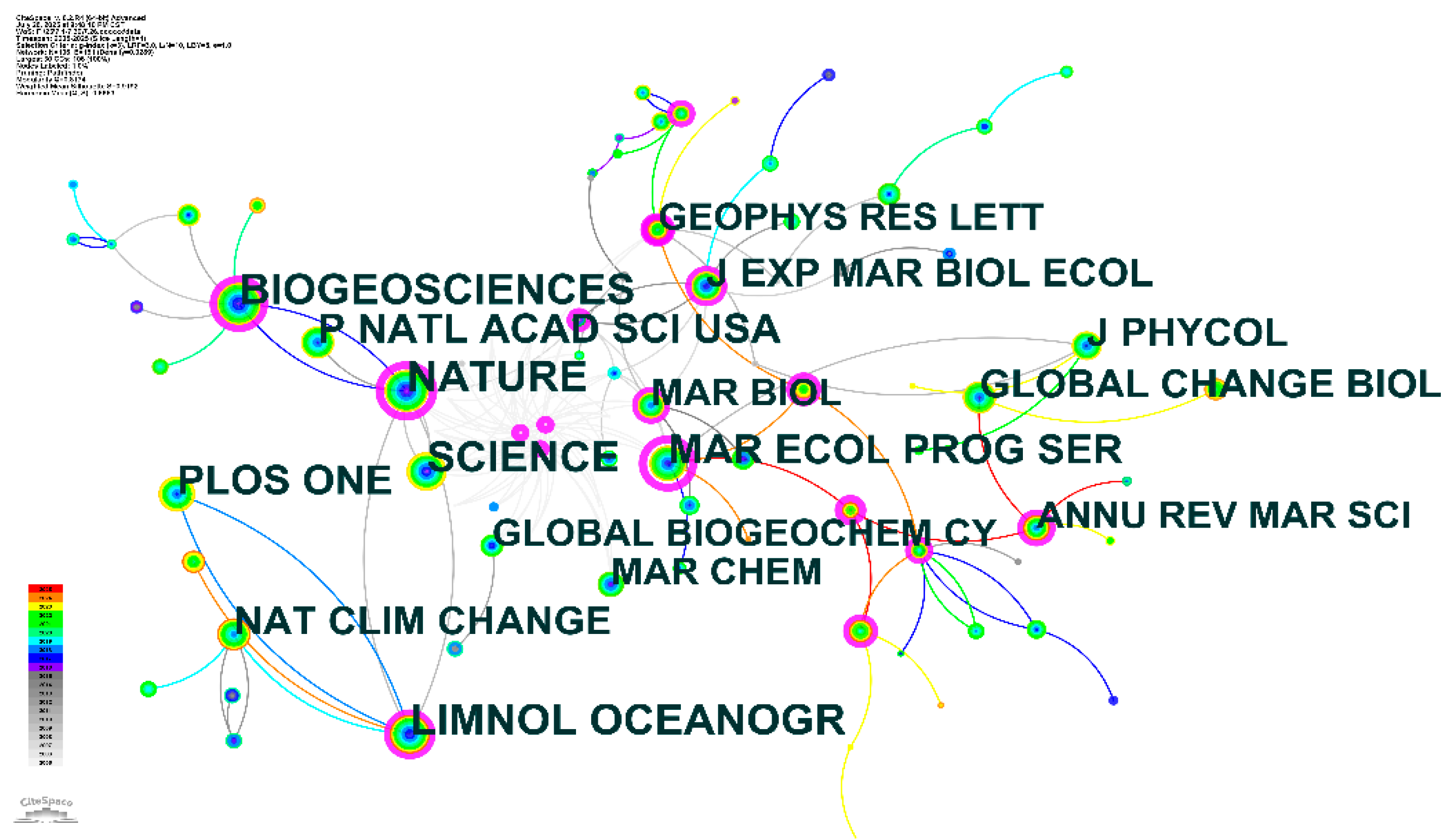

3.3. Journal Co-citation Network Analysis

The journal co-citation network analysis reveals the intellectual structure and disciplinary foundations of OA and microbial ecology research(Fig.3). The network visualization demonstrates distinct clustering patterns that reflect the interdisciplinary nature of this research field, with clear connections between marine biology, oceanography, climate science, and biogeochemistry journals. The central position of core journals such as NATURE, SCIENCE, and BIOGEOSCIENCES indicates their foundational role in establishing the theoretical framework for OA research. These high-impact journals serve as primary knowledge sources, with NATURE and SCIENCE providing seminal papers that define the field's conceptual boundaries, while BIOGEOSCIENCES contributes specialized research on biogeochemical processes[

68]. The prominence of LIMNOL OCEANOGR (Limnology and Oceanography) reflects the field's strong oceanographic foundation, emphasizing the importance of physical and chemical oceanography in understanding acidification processes[

69].

Figure 3.

Journal co-citation network of acidification-microbial interaction research.

Figure 3.

Journal co-citation network of acidification-microbial interaction research.

The network structure reveals several distinct research clusters. The marine ecology cluster, anchored by journals such as MAR BIOL (Marine Biology), MAR ECOL PROG SER (Marine Ecology Progress Series), and EXP MAR BIOL ECOL (Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology), represents the biological response component of acidification research. This cluster focuses on organism-level and community-level effects, encompassing experimental studies on microbial physiology, community dynamics, and ecosystem responses. The strong connections between these journals indicate substantial knowledge exchange regarding biological impacts and experimental methodologies. The oceanographic and chemical cluster, including GEOPHYS RES LETT (Geophysical Research Letters) and MAR CHEM (Marine Chemistry), emphasizes the fundamental role of ocean chemistry and physics in acidification research[

70]. These journals contribute essential knowledge regarding carbonate chemistry, pH dynamics, and the physical processes that govern acidification patterns across different ocean basins and depth layers[

71,

72].

The climate and global change cluster, represented by journals including GLOBAL CHANGE BIOL (Global Change Biology), NAT CLIM CHANGE (Nature Climate Change), and GLOBAL BIOGEOCHEM CY (Global Biogeochemical Cycles), demonstrates the field's integration with broader climate science research. This clustering pattern reflects the recognition that OA represents a critical component of global environmental change, requiring interdisciplinary approaches that combine climate modeling, biogeochemical cycling, and ecological research[

73,

74,

75].

The temporal dynamics reflected in the network's color coding indicate the evolution of research focus over time. Earlier research, represented by more traditional oceanographic and marine biology journals, established the foundational understanding of ocean chemistry and biological systems. More recent publications, indicated by warmer colors in the network, show increased representation in climate science and global change journals, reflecting the field's evolution toward broader environmental and policy relevance.

The presence of specialized journals such as J “PHYCOL” (Journal of Phycology) and “ANNU REV MAR SCI” (Annual Review of Marine Science) indicates the field's development of specialized knowledge domains while maintaining connections to broader scientific literature. The positioning of PLOS ONE within the network reflects the growing importance of open-access publishing in disseminating acidification research to diverse scientific communities. The network's connectivity patterns reveal strong interdisciplinary collaboration, with multiple connecting pathways between different journal clusters. This interconnectedness suggests that OA and microbial ecology research has successfully integrated knowledge from diverse scientific disciplines, creating a cohesive research framework that addresses the complexity of acidification impacts on marine ecosystems.

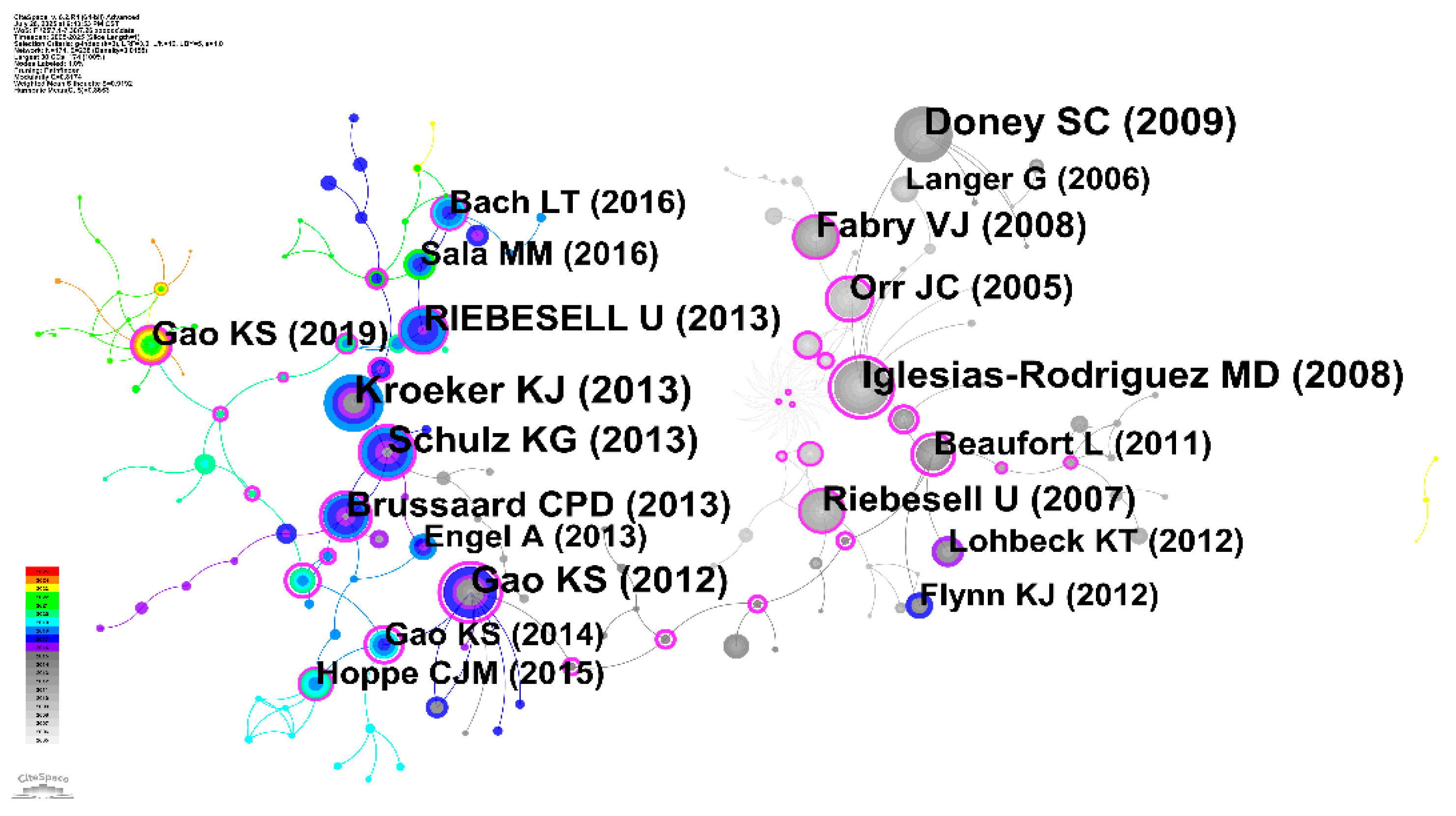

3.4 Literature Co-citation Network Analysis

The literature co-citation network (Fig.4) reveals three primary knowledge clusters that represent the foundational intellectual pillars of OA research. The central cluster, dominated by highly cited foundational works such as Orr et al. (2005) [

76] with 24 citations, Riebesell et al. (2007, 2013) [

77,

78] with 26 and 28 citations respectively, and Kroeker et al. (2013)[

79]with 37 citations, establishes the core theoretical framework for understanding OA impacts on marine ecosystems. This cluster demonstrates strong interconnectedness through co-citation relationships, indicating that these seminal papers consistently appear together in subsequent research, forming the conceptual backbone of the field. The prominence of Riebesell's multiple contributions across different years (2007, 2011, 2013) [

78,

79]; Gattuso, J. P., Bijma, J., Gehlen, M., Riebesell, U., & Turley, C. (2011). Effects of OA on pelagic organisms and ecosystems. Oxford University Press.) suggests sustained intellectual leadership, while the 2013 meta-analysis by Kroeker et al. represents a key synthesis point, examining the effects of OA on marine organisms, has become one of the core literature in this field [

79]. The second major cluster centers around experimental methodology and phytoplankton responses, anchored by works such as Iglesias-Rodriguez et al. (2008) [

80] with 34 citations and Beaufort et al. (2011) [

81] with 21 citations, which focus specifically on calcifying organisms and coccolithophores under acidification stress. This cluster's positioning in the network suggests it serves as a bridge between theoretical predictions and empirical observations, with strong citation relationships to both foundational theory papers and more recent experimental studies.

Figure 4.

Literature co-citation network for acidification-microbial interaction.

Figure 4.

Literature co-citation network for acidification-microbial interaction.

The temporal evolution visible in the network structure illuminates how research focus has shifted from early observational studies to sophisticated experimental approaches and ecosystem-level investigations. Early influential papers from 2005-2008, including Doney et al. (2009) [

3]and Fabry et al. (2008)[

7], established the basic chemical and biological principles of OA, forming dense co-citation relationships that persist throughout the network. The period from 2011-2013 represents a consolidation phase, with major synthesis works like Gao et al. (2012, 2014) [

82,

83] and multiple Riebesell publications creating a highly interconnected central hub that subsequent research consistently references. More recent studies from 2015-2019, including Bach et al. (2016, 2017) [

84,

85] and various specialized investigations, show increasingly diverse citation patterns, suggesting field maturation with specialized sub-disciplines emerging around specific organisms, experimental techniques, and ecosystem components. The network topology indicates that while foundational papers maintain their centrality, newer research is creating more specialized citation clusters, reflecting the field's evolution from broad theoretical understanding to detailed mechanistic investigations of specific microbial communities and biogeochemical processes under acidification scenarios[

86,

87].

The structural characteristics of the co-citation network further reveal the interdisciplinary nature of OA research and its integration with broader marine science disciplines. The positioning of key methodological papers, such as those by Schulz et al. (2013) [

88] and Brussaard et al. (2013) [

22] with 32 and 28 citations respectively, indicates strong methodological standardization within the field, with these works serving as essential references for experimental design and data interpretation. The network's hub-and-spoke configuration around central nodes suggests that while the field has diversified into specialized research areas, it maintains strong theoretical coherence through consistent reference to foundational works. This pattern is particularly evident in the clustering of papers addressing specific taxonomic groups or experimental approaches, which nonetheless maintain strong co-citation relationships with the core theoretical literature, ensuring conceptual continuity across diverse research applications and maintaining the field's intellectual unity despite increasing specialization.

3.5. The Global Architecture of Scientific Production and Collaboration

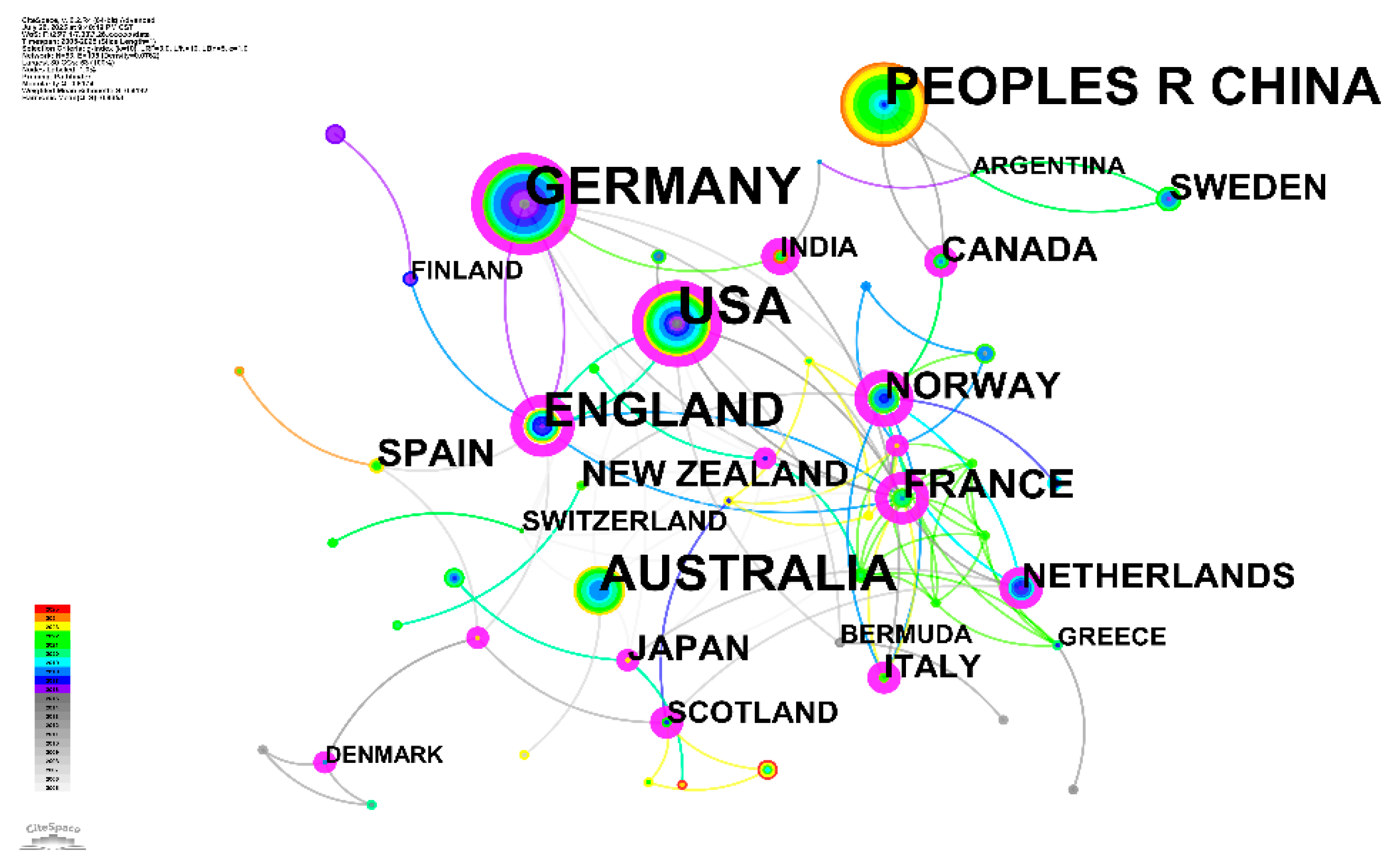

The social and organizational structure of a scientific field dictates the flow of knowledge, the formation of consensus, and the direction of future research. Collaborative network analysis reveals that research on the impact of OA on microorganisms worldwide exhibits highly collaborative, multipolar, yet hierarchical characteristics. This network is composed of influential research teams comprising key countries, core research institutions, and closely connected researchers. The national collaboration network consists of 53 countries, presenting a globally distributed yet uneven research landscape (Fig.5). The network is dominated by three major countries: China, the USA, and Germany. These countries are represented by the largest nodes, indicating the highest publication output. Additionally, the USA and Germany exhibit high betweenness centrality (indicated by purple rings), suggesting they play a pivotal role as bridges in international information flow. Following closely are other high-output countries, including the UK, France, Australia, and Norway, which form a mature research core.

Figure 5.

Country co-occurrence map for acidification-microbial interaction research.

Figure 5.

Country co-occurrence map for acidification-microbial interaction research.

A notable feature of the network is China's prominent and central position. The multi-colored citation rings on the ‘PEOPLES R CHINA’ node, with a strong emphasis on recent years (yellow and orange outer rings), point to its rapid emergence as a major power in this field of research. Currently, there are some connections between China and countries such as Canada and Argentina, indicating strategic engagement involving joint research projects, shared experimental platforms, and significant knowledge exchange. However, compared to countries like the USA and Germany, China still needs to enhance its international cooperation. This integrated growth model will enable China to not only become an important research producer but also a core and indispensable node in the global network.

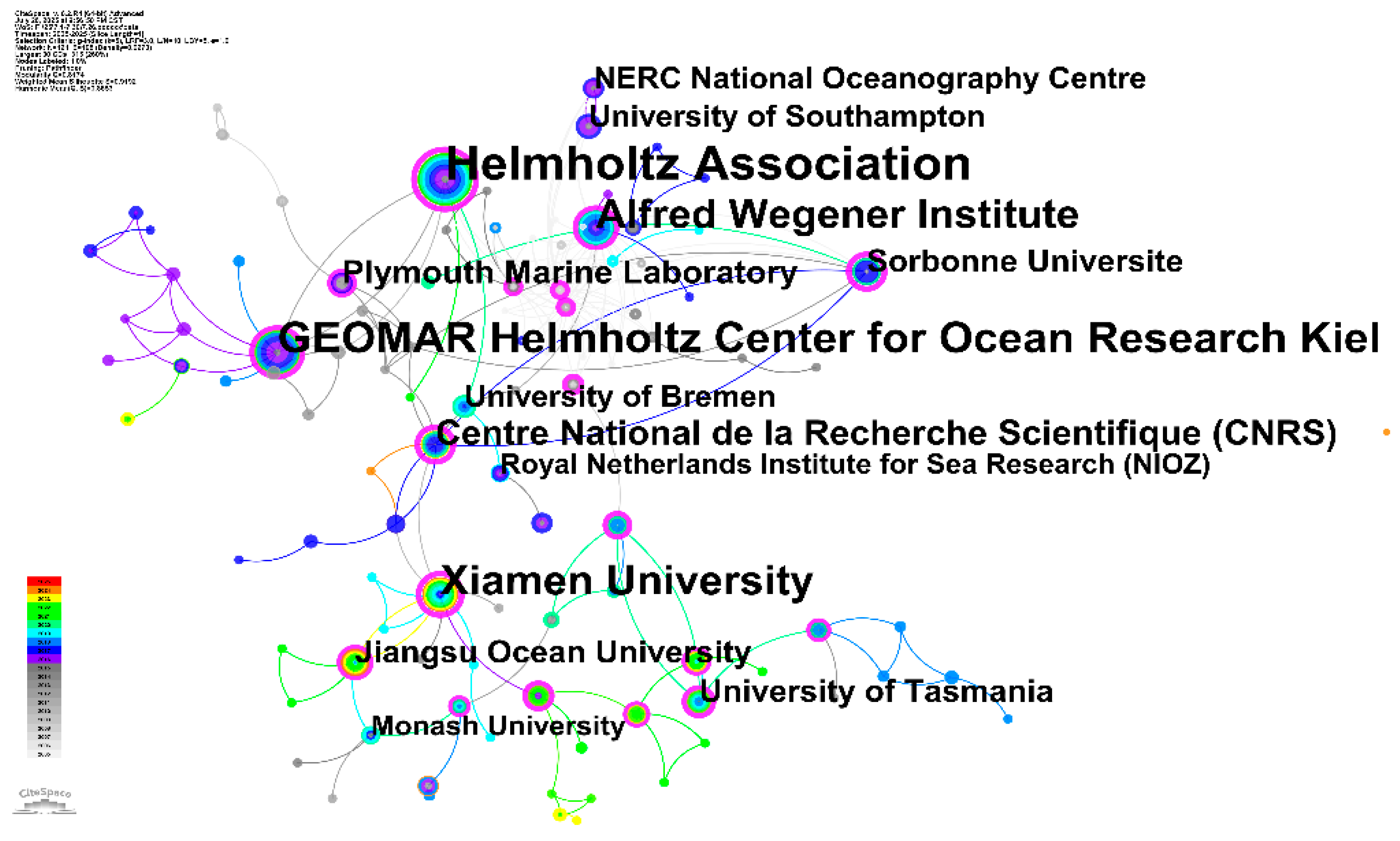

The institutional co-citation network analysis (Fig.6) reveals the global research infrastructure and collaborative patterns underlying OA and microbial ecology research. The network visualization demonstrates a well-established international research community characterized by strong European leadership, emerging Asia-Pacific contributions, and strategic institutional partnerships that span multiple continents.

Figure 6.

Institution co-occurrence map for acidification-microbial interaction research.

Figure 6.

Institution co-occurrence map for acidification-microbial interaction research.

The network structure clearly demonstrates European dominance in OA and microbial ecology research. GEOMAR Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research Kiel occupies the most prominent central position in the network, indicating its role as a global leader in this research domain. GEOMAR's centrality reflects its comprehensive research programs spanning from molecular-level studies of microbial responses to ecosystem-scale investigations of acidification impacts. The institution's strong position suggests it serves as a critical knowledge hub, facilitating collaboration and knowledge exchange across the international research community. The Helmholtz Association appears as a distinct network node, highlighting the important role of this German research organization in coordinating large-scale, interdisciplinary research efforts. The Helmholtz Association's involvement indicates that OA research benefits from substantial institutional support for long-term, coordinated research programs that transcend individual laboratory capabilities. The Alfred Wegener Institute represents another major German contribution to the field, particularly renowned for polar and marine research [

89,

90]. Its position in the network reflects the critical importance of polar regions in global acidification research, as these environments experience particularly rapid acidification and serve as sentinel systems for understanding global change impacts on marine ecosystems [

27,

91,

92].

In addition, Plymouth Marine Laboratory in the United Kingdom occupies a strategic position, bridging European continental research with UK-based institutions. The Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) represents France's substantial contribution to the field, indicating the importance of the French national research system in advancing OA science. The node of CNRS suggests strong integration between French research institutions and the broader European research network, facilitating knowledge transfer and collaborative research initiatives.

Meanwhile, the network reveals significant Asia-Pacific research contributions, indicating the global expansion of acidification research capacity. Xiamen University occupies a prominent position, representing China's growing leadership in marine science research. The university's centrality suggests it serves as a major hub for acidification research in the Asia-Pacific region, facilitating regional collaboration and contributing unique perspectives on acidification impacts in tropical and subtropical systems. The positioning of Chinese institutions suggests successful integration with international research networks while developing independent research capabilities. Monash University and the University of Tasmania represent Australia's significant contributions to acidification research. Tasmania's prominence is particularly notable given its strategic location in the Southern Ocean, where rapid acidification intersects with unique marine ecosystems[

93]. These Australian institutions contribute essential knowledge regarding acidification impacts in the Southern Hemisphere and on cold-water marine communities.

The color ring of nodes in the network suggests an evolution from European-dominated research toward more globally distributed research capacity. Earlier research phases, indicated by cooler colors, show strong European foundations, while more recent developments, shown in warmer colors, indicate expanded global participation and emerging research leadership from Asia-Pacific institutions. The institutional co-citation network demonstrates that OA and microbial ecology research has developed into a truly global scientific enterprise characterized by strong international collaboration, distributed research capacity, and emerging leadership from multiple continents. The network structure suggests several important implications for future research development: First, the continued prominence of European institutions indicates sustained research leadership, while the emergence of Asia-Pacific institutions suggests expanding global research capacity. Second, the network structure facilitates knowledge transfer and collaborative research across diverse marine environments, from polar seas to tropical oceans. Third, the institutional diversity supports multiple research approaches, from reductionist laboratory studies to ecosystem-scale field investigations. The institutional analysis reveals that global research capacity in OA and microbial ecology is well-positioned to address the complex, multi-scale challenges associated with understanding and predicting acidification impacts on marine microbial communities in the context of ongoing global environmental change.

3.6 Influential Authors Network Analysis

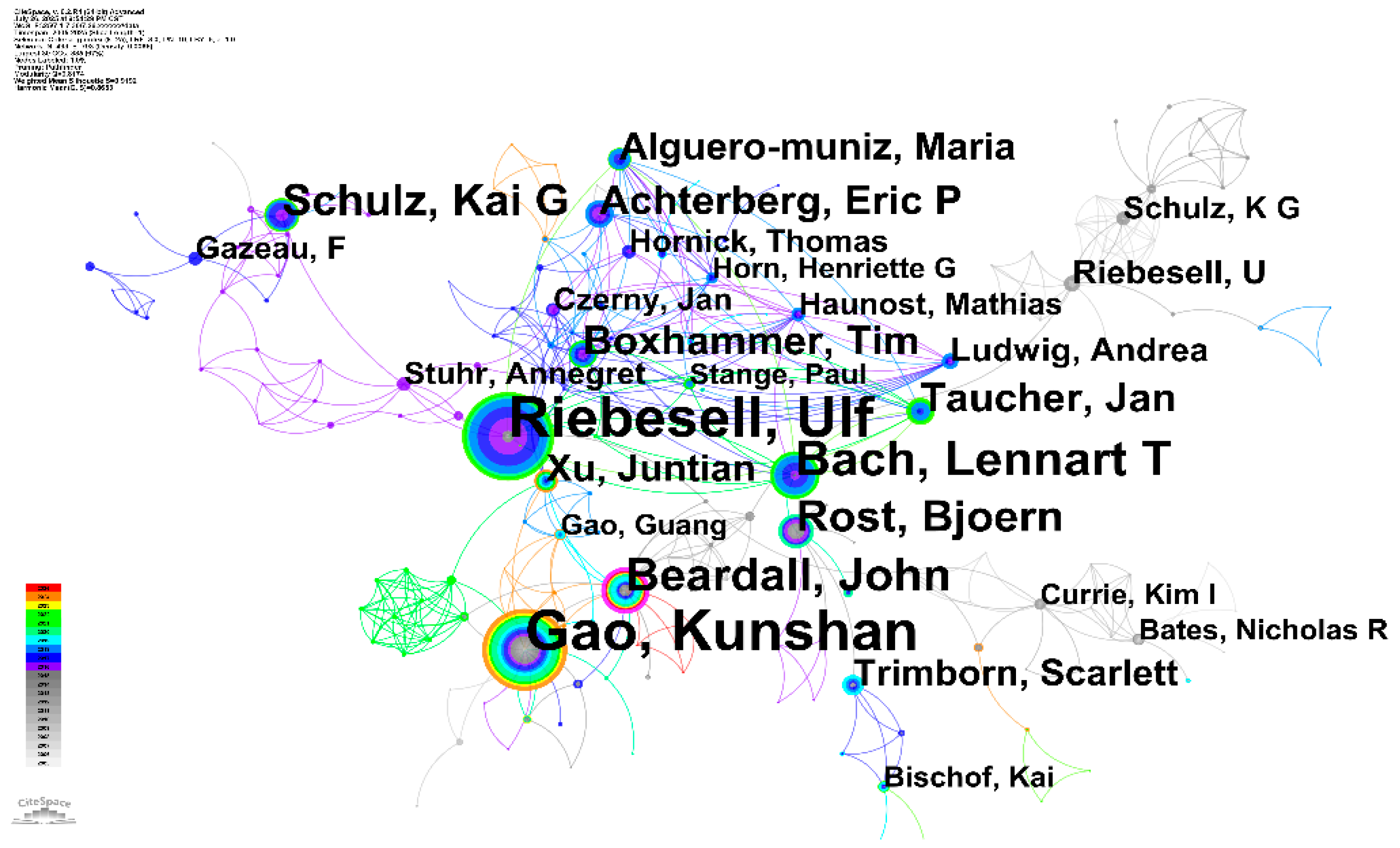

The comprehensive analysis of author networks in OA impacts research on microbial ecology reveals both the collaborative structure of the research community and the intellectual foundations that have shaped the field's development. The author collaboration network demonstrates a well-established international research community characterized by strong partnerships and distinct research clusters, while the co-citation analysis illuminates the conceptual framework and knowledge base that underpins current understanding of OA impacts on microbial systems (Fig.7).

Figure 7.

Author co-occurrence map for acidification-microbial interaction research.

Figure 7.

Author co-occurrence map for acidification-microbial interaction research.

The author collaboration network consisting of 491 authors, analysis reveals several prominent research groups. The high modularity (Q = 0.8174) and mean silhouette score (S = 0.9192) indicate that the network is clearly divided into distinct and highly coherent research clusters, suggesting that research in this domain is primarily conducted by several relatively independent, yet interconnected, scientific communities. The most prolific author, indicated by the largest node size, is Ulf Riebesell, followed by other highly productive researchers such as Kunshan Gao, Lennart T. Bach, and Beardall, John. Meanwhile, Ulf Riebesell, Kunshan Gao and John Beardall et,al. also serve as important bridges within the network. Analysis of the primary clusters reveals the key collaborative powerhouses in this research area. The largest and most central cluster is a tightly-knit group led by Ulf Riebesell, with core members including Lennart T. Bach, Tim Boxhammer, Kai G. Schulz, and Eric P. Achterberg. The color rings of these nodes, spanning from blue to vibrant green and yellow, demonstrate this group's long-standing and sustained contributions to the field. A second major cluster is centered around Kunshan Gao, who frequently collaborates with John Beardall and Juntian Xu. The bright, warm-colored rings of Gao's node signify a significant volume of high-impact research in more recent years. Other notable, albeit smaller, clusters include a group associated with Fabrice Gazeau and another involving Nicholas R. Bates and Kim I. Currie. The temporal evolution shown by the color links indicates that while foundational collaborations were established by these core groups, the field has seen a dynamic expansion of its collaborative web over time, integrating new researchers and fostering inter-cluster connections.

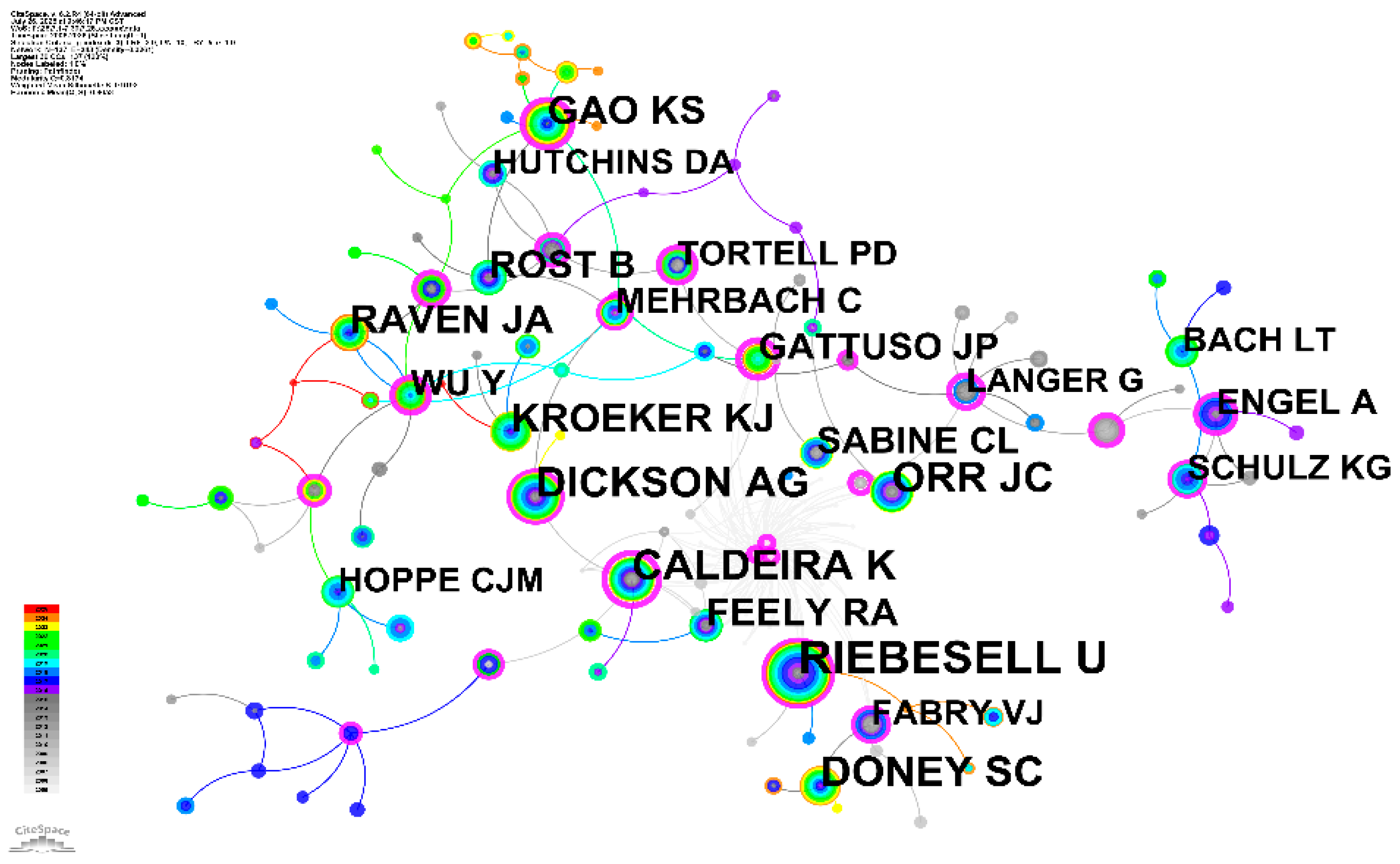

The co-citation network of authors delineates the intellectual foundation and the primary research fronts of the field (Fig.8). In contrast, the author co-citation cluster map emphasizes scholarly impact rather than collaboration [

32]. The network is composed of 136nodes, characterized by a high modularity (Q = 0.8174) and a strong silhouette score (S = 0.9192). These metrics signify that the field's knowledge base is structured around several distinct and highly coherent intellectual clusters. The node size, representing the citation frequency, identifies the most influential scholars whose works are cornerstones of this research domain. The most prominent nodes belong to U. Riebesell, K. Caldeira, Gao KS, J. C. Orr, J.-P. Gattuso, and S. C. Doney, indicating their status as the most highly cited and foundational authors. Furthermore, several of these key authors, notably K. Caldeira, Gao KS, and J.-P. Gattuso, exhibit the highest betweenness centrality, signifying that their work serves a pivotal bridging function, connecting different sub-fields and forming the central intellectual backbone of the research area.

Figure 8.

Author co-citation map for acidification-microbial interaction research.

Figure 8.

Author co-citation map for acidification-microbial interaction research.

The clustering within the network reveals several major research fronts. A large, central cluster comprising the aforementioned foundational authors (Caldeira, Feely, Orr, Gattuso, Riebesell, Doney) represents the core intellectual domain, likely focused on the fundamental biogeochemistry, global-scale impacts, and initial conceptualization of OA. A second significant cluster includes K. S. Gao, D. A. Hutchins, B. Rost, and J. A. Raven, suggesting a research front concentrated on the physiological and ecological responses of phytoplankton and primary producers to changing ocean chemistry[

94,

95,

96,

97]. Another distinct group, featuring L. T. Bach, A. Engel, and K. G. Schulz, points to a specialized focus, possibly on the role of specific plankton groups like coccolithophores and their influence on biogeochemical cycles[

85,

98,

99]. Notably, the small but central cluster of A. G. Dickson and C. Mehrbach highlights the critical importance of their foundational work on seawater carbonate system measurements, which underpins the methodological consistency of the entire field[

100]. The temporal aspect, illustrated by the multi-colored rings on nodes like Riebesell and Caldeira, shows their sustained citation impact over the entire study period, confirming the long-term relevance of their foundational contributions.

3.7 Keyword Co-occurrence Network Analysis

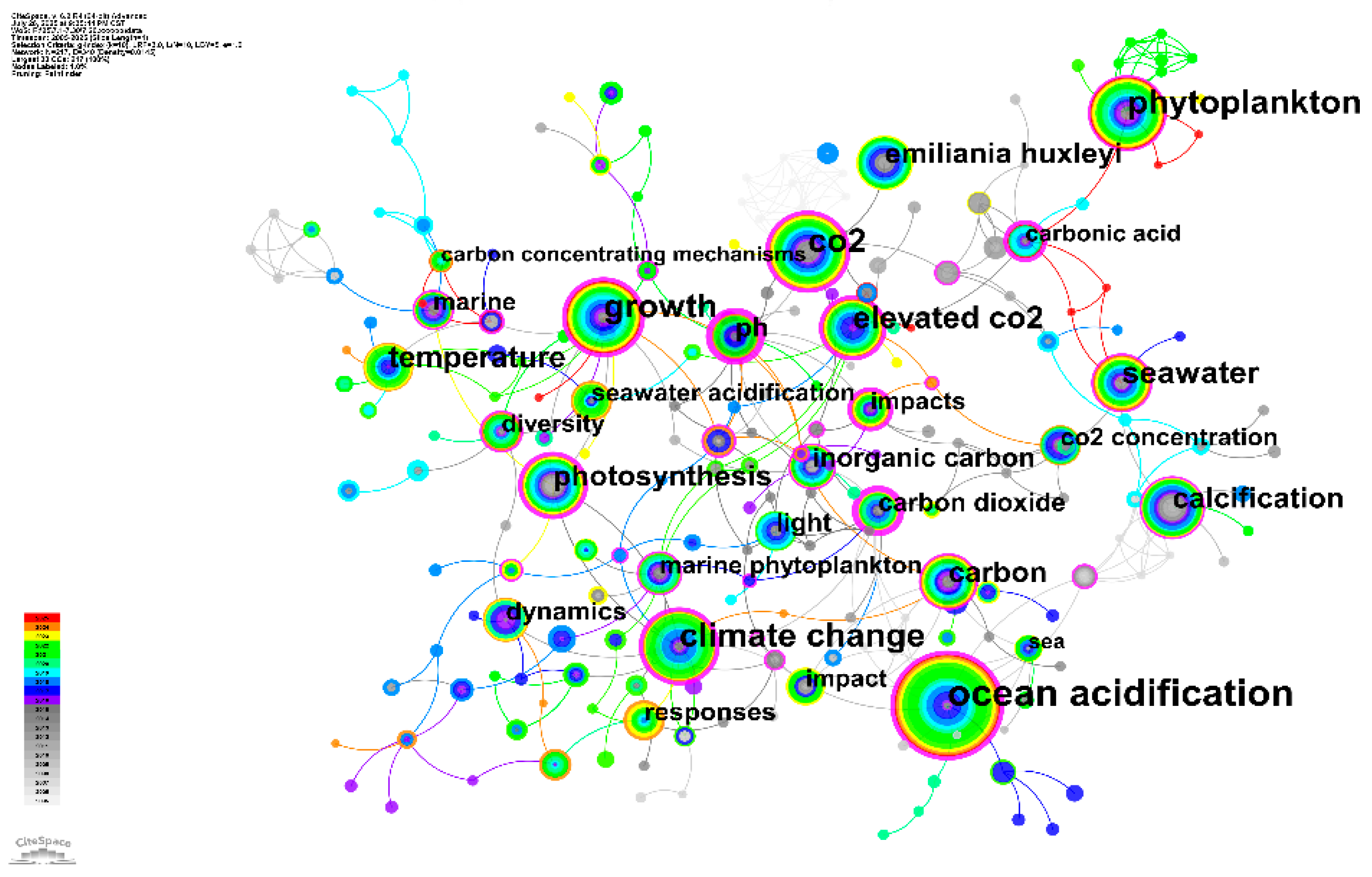

The keyword co-occurrence network reveals a sophisticated conceptual architecture that illuminates the multidisciplinary nature and thematic evolution of OA research affecting microbial ecosystems (Fig.9). The network structure demonstrates a hierarchical organization with "ocean acidification" serving as the dominant central hub, exhibiting the largest node size and highest connectivity, which reflects its role as the primary unifying concept that connects all research themes within this domain. The positioning of core concepts such as "climate change," "CO2," "elevated CO2," and "seawater acidification" in close proximity to the central hub indicates their fundamental importance as driving forces and mechanistic frameworks that underpin the entire research field. This central cluster effectively represents the biogeochemical foundation of the discipline, where atmospheric carbon dioxide increases lead to ocean chemistry changes that cascade through marine ecosystems. The strong interconnectedness among these foundational terms, evidenced by thick connecting lines and overlapping temporal patterns shown in the color gradients, suggests that researchers consistently examine these concepts together, creating a stable theoretical core that persists across different research approaches and time periods.

Figure 9.

Keyword co-occurrence map for acidification-microbial interaction research.

Figure 9.

Keyword co-occurrence map for acidification-microbial interaction research.

The network topology further reveals distinct thematic clusters that represent specialized research domains within the broader field, each focusing on specific biological responses and ecological processes under acidification stress. The prominent positioning of “phytoplankton,” “marine phytoplankton,” and “Emiliania huxleyi” indicates a strong focus on primary producers, particularly calcifying species that serve as model organisms for understanding acidification impacts on marine food webs[

99,

101,

102]. The close association of these biological terms with process-oriented keywords such as “calcification,” “photosynthesis,” “growth,” and “carbon concentrating mechanisms” demonstrates how research has evolved from simple organismal responses to detailed mechanistic investigations of physiological and biochemical adaptations[

103,

104,

105]. Zhang et al. conducted land-based mesocosm experiments in the South China Sea to evaluate the effects of OA on phytoplankton photosynthetic capacity, community composition, and functional diversity. The results indicate that OA consistently inhibited marine primary production[

106]. The temporal color coding within these clusters suggests that while early research focused on broad organismal responses, more recent investigations have delved into specific cellular and molecular mechanisms, reflecting the field's progression toward mechanistic understanding of acidification effects on microbial communities and their biogeochemical functions[

107,

108]. An integrative analysis combining metabolomics and 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing elucidated the underlying mechanisms by which

Macrocystis pyrifera and its symbiotic bacteria respond to OA. OA altered the structure of the

M. pyrifera–associated microbiome, shifted its metabolic profile, and reshaped microbe–metabolite interactions. Stress-responsive molecules—including fatty-acid metabolites, oxylipins, and hormone-like compounds—emerged as key metabolomic indicators[

109].

The network structure also reveals important methodological and contextual dimensions that highlight the experimental sophistication and environmental relevance of contemporary OA research. The positioning of terms such as “temperature,” “impacts,” “responses,” and “dynamics” in intermediate network positions suggests their role as bridging concepts that connect fundamental acidification processes with broader ecological and environmental contexts. The integration of “diversity” and “inorganic carbon” within the network architecture indicates that research has expanded beyond single-species studies to encompass community-level responses and biogeochemical cycling implications[

86,

110,

111]. The temporal evolution visible through color gradients shows how methodological approaches have become increasingly sophisticated, with recent research incorporating multiple stressor interaction, long-term experimental designs, and ecosystem-scale investigations. This network configuration demonstrates that OA research has matured into a comprehensive discipline that integrates chemical, biological, and ecological perspectives to understand how changing ocean chemistry affects microbial communities and their critical roles in marine ecosystem functioning and global biogeochemical cycles.

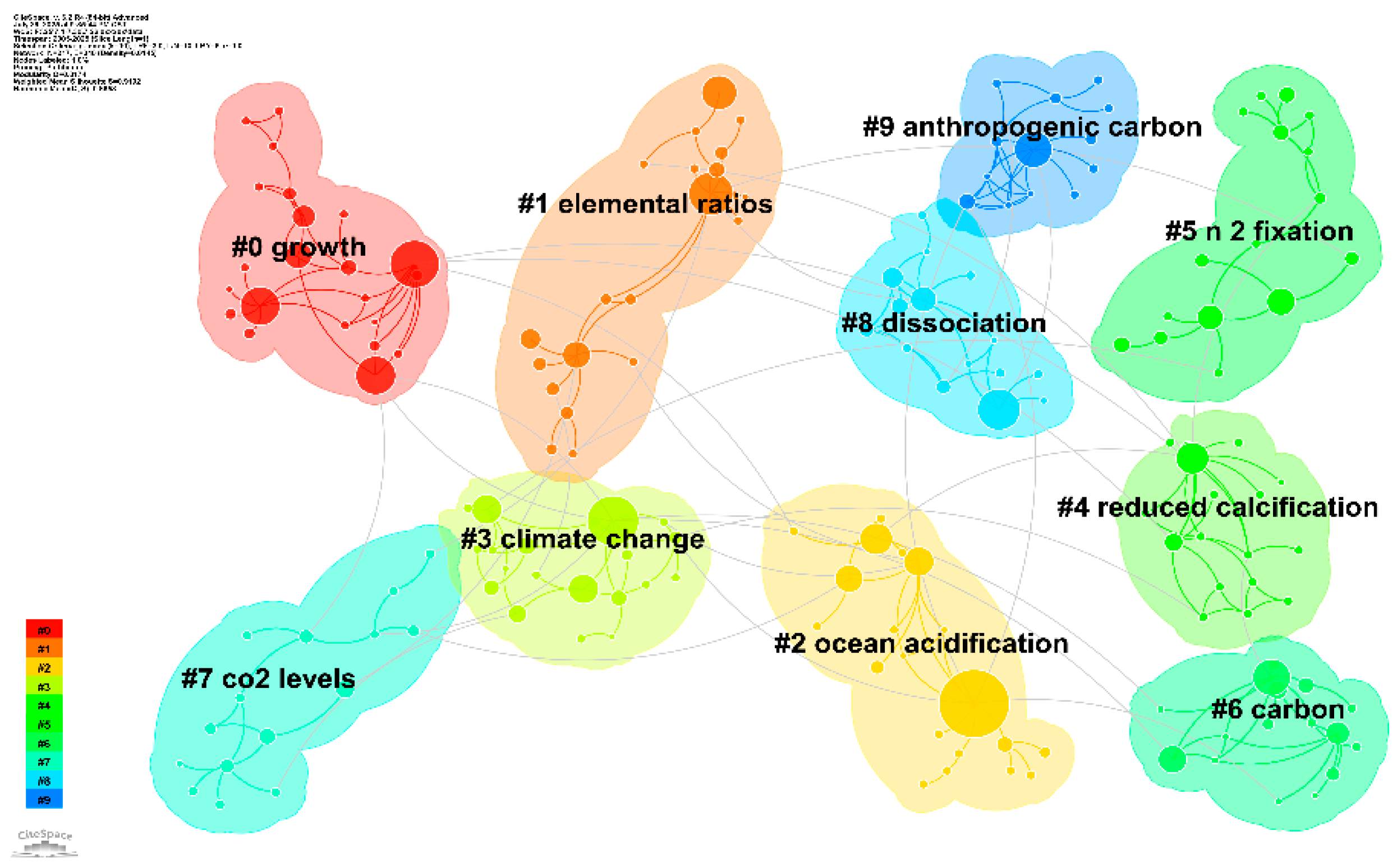

3.8 Keyword Clustering Map Analysis

The keyword clustering map generated from the CiteSpace analysis reveals ten major thematic clusters in the field of OA’s impact on microbial ecology, each representing a cohesive body of literature centered around specific research foci (Fig10). The clustering quality is high, as indicated by the modularity (Q = 0.8146) and mean silhouette value (S = 0.9192), suggesting well-defined, internally consistent research areas. The largest and most prominent cluster (#0) is labeled “growth,” encompassing studies that investigate microbial growth responses to lowered pH and elevated pCO₂[

112,

113,

114]. These works often employ laboratory microcosms or mesocosms to assess physiological plasticity and shifts in productivity across diverse microbial taxa[

115,

116]. Closely connected to this cluster is cluster #1, “elemental ratios,” which focuses on changes in the stoichiometry of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus under acidified conditions. This body of work often intersects with studies on nutrient limitation and phytoplankton functional groups, providing a mechanistic understanding of altered biogeochemical cycling[

117].

Figure 10.

Co-occurring keyword cluster network.

Figure 10.

Co-occurring keyword cluster network.

Cluster #2, “ocean acidification,” serves as a central thematic bridge, linked to nearly all other clusters, reflecting its role as a foundational concept that integrates physiological, ecological, and biogeochemical dimensions. Its proximity to clusters such as #3 (“climate change”) and #7 (“CO₂ levels”) further highlights the convergence of acidification research with broader climate-related stressors. Cluster #4, “reduced calcification,” and cluster #5, “N₂ fixation,” represent specialized but increasingly interconnected areas, as studies reveal how changes in carbonate chemistry and trace metal bioavailability under acidification scenarios may influence both calcifying organisms and diazotrophic microbial communities[

118,

119]. The presence of cluster #6, labeled simply “carbon,” suggests a cross-cutting interest in carbon cycling, encompassing carbon fixation, respiration, and dissolved organic carbon dynamics[

120]. Meanwhile, clusters #8 (“dissociation”) and #9 (“anthropogenic carbon”) represent more chemically or modeling-oriented subfields, emphasizing carbonate system equilibrium and anthropogenic CO₂ attribution, respectively [

113,

121].

The clustering structure demonstrates a field that is both thematically diverse and intellectually integrated. The adjacency and interconnectivity of clusters reflect a growing trend toward interdisciplinary inquiry—linking microbial physiology with global change biology and Earth system processes. The clear boundaries between clusters such as “elemental ratios,” “N₂ fixation,” and “reduced calcification” also suggest that while conceptual bridges are emerging, further interdisciplinary collaboration across subfields remains a promising direction for future research.

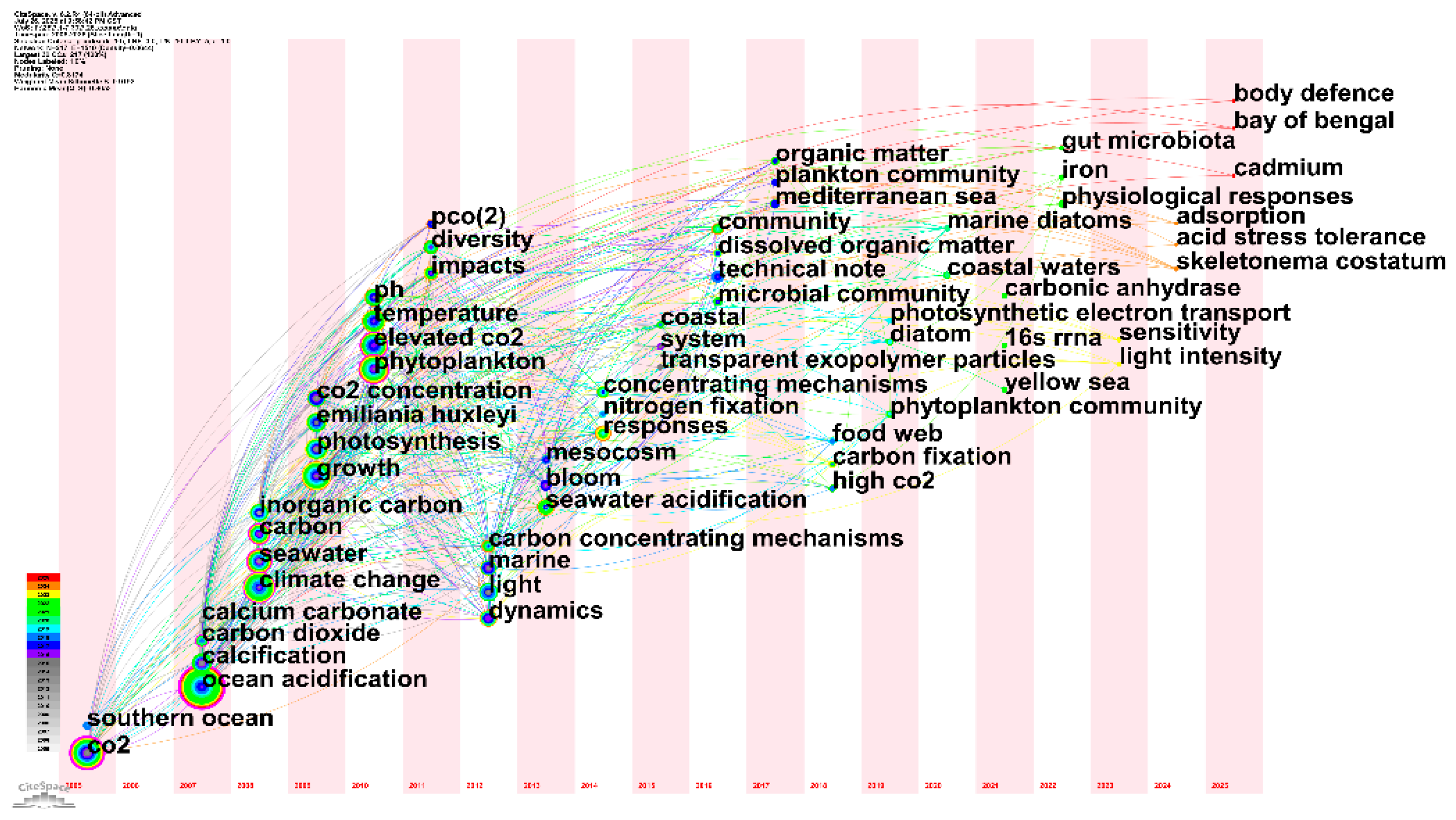

3.9 Temporal Evolution of Research Keyword

The timeline visualization of keyword emergence reveals distinct phases of conceptual evolution in OA research, demonstrating a clear progression from foundational chemical concepts to sophisticated biological and ecological investigations spanning two decades (Fig.11). The early foundational period (2005-2010) is characterized by the establishment of core chemical and physical parameters, with fundamental terms such as "CO2," "carbon dioxide," "ocean acidification," and "southern ocean" appearing as the initial conceptual framework. This period represents the essential groundwork where researchers established the basic chemistry of OA, with "calcium carbonate" and "calcification" emerging as critical early concepts that linked atmospheric CO2 increases to direct impacts on marine calcifying organisms[

14]. The positioning of "seawater" and "climate change" during this phase indicates that early research focused on understanding the basic mechanistic relationships between global carbon cycling and ocean chemistry changes[

122,

123], establishing the environmental context that would drive all subsequent microbiology investigations.

Figure 11.

Time zone view of keywords of acidification-microbial interaction.

Figure 11.

Time zone view of keywords of acidification-microbial interaction.

The intermediate expansion phase (2011-2016) demonstrates substantial thematic diversification as research transitioned from basic chemistry to biological responses and ecological processes. The emergence of organism-specific terms such as "Emiliania huxleyi" and "phytoplankton" alongside process-oriented concepts like "photosynthesis," "growth," and "carbon concentrating mechanisms" reveals how the field evolved to examine specific biological responses to acidification stress[

99,

124]. The appearance of methodological terms including "elevated CO2," "CO2 concentration," and "inorganic carbon" during this period indicates increasing experimental sophistication, with researchers developing standardized approaches to manipulate and measure acidification effects[

79,

125]. The temporal clustering of "mesocosm," "bloom," and "responses" suggests that this phase was characterized by scaled experimental approaches that moved beyond simple laboratory studies to more realistic ecological simulations, representing a critical methodological advancement that enabled more comprehensive understanding of acidification impacts on marine ecosystems[

84,

126].

The recent specialization phase (2017-2025) reveals remarkable thematic diversification and increasing integration with broader marine ecology and environmental science disciplines. The emergence of highly specialized terms such as "16s rrna," "carbonic anhydrase," and "photosynthetic electron transport" indicates that research has progressed to molecular and cellular levels, examining specific physiological and biochemical mechanisms underlying acidification responses[

127,

128]. A recent study reported that the marine bacterium

Pseudomonas sihuiensis -BFB-6S adapts to the adverse effects of OA by modulating extracellular polymeric substances(EPS). Variations in OA levels modify the EPS matrix, altering the total contents of proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids, as well as fluorophore composition and the relative abundance of aromatic amino acids such as tryptophan and tyrosine[

129]. The appearance of ecosystem-level concepts including "food web," "community," "microbial community," and "plankton community" demonstrates concurrent scaling up to understand broader ecological implications beyond individual organism responses[

130]. The integration of environmental context terms such as "mediterranean sea," "bay of bengal," "coastal waters," and "yellow sea" reflects increasing recognition of regional variability and ecosystem-specific responses to acidification. The recent emergence of interdisciplinary concepts like "acid stress tolerance," "physiological responses," and "adsorption" suggests that the field is expanding to incorporate stress biology, environmental chemistry, and biogeochemical cycling perspectives, indicating maturation into a comprehensive interdisciplinary research domain that addresses acidification impacts across multiple biological scales and environmental contexts[

131,

132].

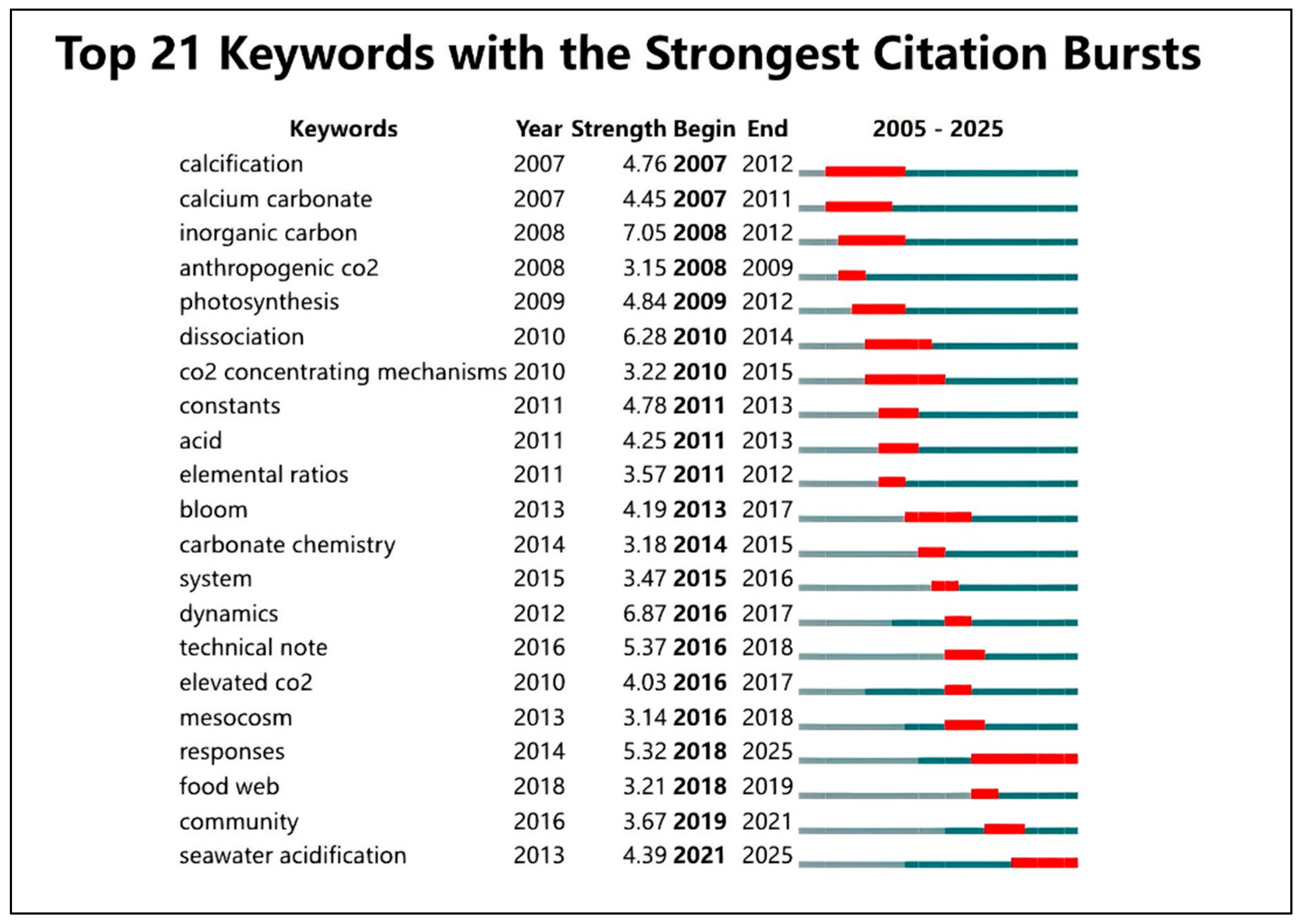

3.10 Citation Burst Analysis of Research Keywords

The citation burst analysis reveals distinct phases of research intensity and paradigm shifts in OA studies, characterized by temporal patterns of keyword emergence that reflect the field's evolution from fundamental chemical understanding to complex biological and ecological investigations (Fig.13). The early burst period demonstrates strong research focus on foundational biogeochemical processes, with "calcification" (strength 4.76, 2007-2012) and "calcium carbonate" (strength 4.45, 2007-2011) representing the initial core concerns about direct impacts of acidification on calcifying organisms. The concurrent emergence of "inorganic carbon" as the strongest early burst (strength 7.05, 2008-2012) indicates intensive research efforts to understand carbon chemistry dynamics in seawater, while "photosynthesis" (strength 4.84, 2009-2012) reflects early recognition that acidification affects not only calcification but also primary productivity. The appearance of "anthropogenic CO2" (strength 3.15, 2008-2009) and "dissociation" (strength 6.28, 2010-2014) during this period establishes the human causation framework and chemical mechanistic understanding that became fundamental to the field, with " CO2 concentrating mechanisms" (strength 3.22, 2010-2015) indicating early investigations into physiological adaptations of marine microorganisms to changing carbonate chemistry[

132].

Figure 12.

Top 21 keywords with the strongest citation bursts (2005–2025).

Figure 12.

Top 21 keywords with the strongest citation bursts (2005–2025).

The intermediate methodological intensification phase reveals a shift toward experimental sophistication and ecological scaling, characterized by bursts in methodological and analytical approaches that enabled more comprehensive investigations of acidification impacts. The emergence of "constants" (strength 4.78, 2011-2013) and "acid" (strength 4.25, 2011-2013) reflects intensification of chemical measurement standardization, while "elemental ratios" (strength 3.57, 2011-2012) indicates increasing attention to biogeochemical stoichiometry under acidification stress. The delayed but strong burst of "bloom" (strength 4.19, 2013-2017) demonstrates growing interest in population-level responses and ecological phenomena, coinciding with "carbonate chemistry" (strength 3.18, 2014-2015) and "system" (strength 3.47, 2015-2016) which reflect more comprehensive ecosystem-level investigations. The notable temporal displacement of "dynamics" (strength 6.87, 2016-2017) and "elevated co2" (strength 4.03, 2016-2017) from their initial appearance years suggests that these concepts gained renewed research intensity as experimental approaches matured, while "technical note" (strength 5.37, 2016-2018) and "mesocosm" (strength 3.14, 2016-2018) indicate methodological advances in controlled experimental systems that enabled more realistic ecological simulations.

The contemporary research expansion phase demonstrates sustained research intensity in ecological and community-level investigations, with "responses" showing the most prolonged and intense burst pattern (strength 5.32, 2018-2025), indicating that understanding biological and ecological responses remains the primary research focus. The sequential emergence of "food web" (strength 3.21, 2018-2019) and "community" (strength 3.67, 2019-2021) reflects the field's evolution toward ecosystem-level understanding, examining how acidification cascades through marine ecological networks rather than focusing solely on individual organism responses. High biodiversity can buffer against the adverse effects of OA, primarily through increased food-resource availability and strengthened microbe–host symbioses[

133].The recent emergence of "seawater acidification" (strength 4.39, 2021-2025) as a distinct burst term suggests conceptual refinement and increased specificity in research approaches, potentially indicating growing recognition of seawater chemistry complexity beyond simple pH changes. This temporal pattern of citation bursts demonstrates that OA research has maintained consistent research intensity while continuously evolving in scope and methodological sophistication, progressing from fundamental chemical understanding through experimental methodology development to contemporary ecosystem-scale investigations that integrate multiple biological levels and environmental contexts.

4. Prospects for OA and Microbial Ecology Research Field

4.1. Integration of Advanced Molecular Technologies and Systems Biology

The temporal evolution of research keywords, progressing from basic chemical parameters to sophisticated biological investigations, signals an imminent transformation through cutting-edge molecular technologies. The field's demonstrated capacity for interdisciplinary integration, evidenced by the strong connections between microbiology, ecology, and environmental sciences disciplines, provides an ideal foundation for incorporating multi-omics approaches that will revolutionize our mechanistic understanding of acidification impacts[

134].

Future research will increasingly leverage integrated genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics approaches to dissect the complex molecular networks governing microbial adaptation to acidification stress. These systems-level investigations will reveal previously hidden regulatory mechanisms, metabolic reprogramming patterns, and evolutionary adaptation strategies that traditional physiological approaches cannot detect[

135]. The application of single-cell sequencing technologies will enable researchers to examine individual microbial responses within complex communities[

136], revealing how cellular heterogeneity contributes to community-level resilience under acidification stress.

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms with multi-omics datasets represents a particularly promising frontier[

137]. These computational approaches will enable predictive modeling of microbial community responses based on molecular signatures, facilitating the identification of early warning indicators for ecosystem-scale changes[

138]. Advanced bioinformatics platforms will integrate environmental data with molecular profiles to develop predictive models capable of forecasting community restructuring under future acidification scenarios[

139].

4.2 Expansion of Temporal and Spatial Research Scales

The current research landscape, while demonstrating strong international collaboration across 53 countries, remains predominantly focused on short-term experimental studies and geographically constrained investigations. The network analysis revealing strong institutional partnerships provides a foundation for coordinated long-term monitoring programs that will capture the full spectrum of microbial community dynamics under progressive acidification scenarios.

Future research initiatives will establish global observatory networks leveraging autonomous underwater vehicles equipped with advanced chemical and biological sensors, enabling continuous monitoring of microbial community structure and function across diverse marine environments[

140]. These expanded observational capabilities will facilitate the detection of subtle ecosystem changes, regime shifts, and tipping points that cannot be captured through traditional experimental approaches. The development of standardized protocols for long-term microbial community monitoring will enable comparative studies across different ocean basins, revealing how regional environmental variability influences acidification impacts[

141,

142]. Future research will integrate physical oceanography, biogeochemistry, and microbial ecology measurements to provide comprehensive understanding of how acidification effects cascade through marine ecosystems over decadal timescales[

143,

144].

4.3 Multiple Stressor Interaction and Climate Change Integration

The keyword co-occurrence network analysis demonstrating strong connections between OA and climate change research indicates critical opportunities for comprehensive multiple stressor investigations. The positioning of terms such as “temperature,” “dynamics,” and “responses” as bridging concepts suggests that the field is well-positioned to examine interactive effects of acidification with warming, deoxygenation, and changing nutrient regimes.

Future experimental facilities will incorporate sophisticated environmental control systems capable of simulating multiple climate stressors simultaneously, enabling researchers to identify synergistic, antagonistic, and additive effects that fundamentally alter predictions based on single-stressor studies[

132,

145]. These multiple stressor approaches will be particularly critical for understanding how acidification impacts cascade through marine food webs under realistic environmental conditions[

146]. The development of Earth system models that integrate microbial community dynamics with global biogeochemical cycles represents a major frontier for understanding how local acidification impacts scale to global carbon cycling patterns[

75,

147]. These modeling efforts will require close collaboration between microbial ecologists, oceanographers, and climate scientists to develop mechanistic representations of microbial processes suitable for incorporation into Earth system models.

4.4 Develop a New Generation of Experimental Systems

The citation burst analysis revealing methodological intensification through terms like “mesocosm,” “technical note,” and “system” indicates continued opportunities for technological innovation that will revolutionize research capabilities. Future experimental systems should incorporate real-time molecular monitoring capabilities, enabling researchers to track gene expression changes, metabolic activities, and community composition dynamics during acidification experiments.

Advanced bioreactor systems will enable precise control of multiple environmental variables while maintaining realistic ecological complexity[

29]. These systems will incorporate microfluidic technologies for studying microbial interactions at microscales, automated sampling systems for high-temporal resolution measurements, and in situ chemical sensors for continuous monitoring of carbonate system parameters.

The development of portable, field-deployable experimental systems will enable acidification research in previously inaccessible environments, from deep-sea hydrothermal vents to polar ice-edge ecosystems[

148,

149]. These technological advances will expand the geographic and environmental scope of acidification research, revealing how microbial communities respond to acidification across the full spectrum of marine environments [

150].

4.5 Computational Biology and Data Integration

The current dominance of specific model organisms, particularly Emiliania huxleyi, presents opportunities for expanding the taxonomic breadth of acidification research[

151]. Future investigations will increasingly incorporate diverse microbial taxa, including previously understudied groups such as marine archaea, viruses, and symbiotic microorganisms[

152,

153,

154]. Comparative approaches across different evolutionary lineages will reveal fundamental principles governing acidification responses and identify universal versus lineage-specific adaptation mechanisms[

155]. These expanded taxonomic investigations will provide more comprehensive understanding of how entire microbial communities reorganize under changing chemical conditions.

Meanwhile, the mature collaborative network structure provides a foundation for unprecedented data integration efforts that will transform predictive capabilities. Future research will leverage cloud-computing platforms and standardized data formats to enable seamless integration of datasets from diverse research groups[

156]. Machine learning approaches applied to these integrated datasets will enable the development of predictive models capable of forecasting microbial community responses to future environmental scenarios with unprecedented accuracy[

137,

138]. Deep learning algorithms will identify complex patterns in multi-dimensional datasets that traditional statistical approaches cannot detect, revealing hidden relationships between environmental variables and microbial community dynamics[

157,

158].

The development of digital twins of marine microbial ecosystems will represent a transformative advance, enabling researchers to simulate complex ecological scenarios and test management strategies in virtual environments before implementing them in natural systems[

159]. These computational models will integrate molecular-level processes with ecosystem-scale dynamics, providing comprehensive platforms for understanding acidification impacts across multiple biological and temporal scales[

160].

4.6. Interdisciplinary Synthesis and Knowledge Integration

The disciplinary co-citation network demonstrating successful integration between environmental sciences, oceanography, and microbiology provides a foundation for developing mechanistic models that connect molecular-level processes with ecosystem-scale functions. Future research will increasingly focus on identifying the key scaling relationships that govern how cellular-level responses to acidification manifest as community-level and ecosystem-level changes[

161].

The development of theoretical frameworks that integrate concepts from molecular biology, community ecology, and Earth system science will enable more accurate predictions of how microbial communities will respond to ongoing environmental changes. These interdisciplinary approaches will require novel mathematical modeling techniques that can represent biological processes operating across vastly different spatial and temporal scales. Multi-scale experimental approaches will combine laboratory studies of isolated microbial strains with mesocosm investigations of community dynamics and field studies of natural ecosystem responses [

162,

163,

164]. This integrated experimental strategy will enable researchers to identify which laboratory-observed phenomena translate to ecologically relevant community-level changes under natural conditions.

4.7. Policy-Science Interface Development

The evolution of research themes toward ecosystem-level understanding and the strong connections with climate science research indicate growing potential for policy-relevant research outcomes. The institutional network analysis revealing strong connections between research institutions and the presence of multidisciplinary science approaches provides a foundation for translating fundamental research findings into actionable information for marine resource management.

Future research will increasingly focus on developing microbial indicators for ocean health assessment that can be incorporated into existing monitoring programs. These biological indicators will provide early warning capabilities for detecting ecosystem changes before they become apparent through traditional physical and chemical measurements. The development of decision-support tools that integrate acidification research findings with socioeconomic considerations will enable more effective policy development for marine conservation and climate change mitigation [

162]. These tools will translate complex scientific information into accessible formats that can inform policy decisions at local, national, and international levels [

165].

5. Limitations and Methodological Considerations

Several methodological limitations should be considered when interpreting results from this bibliometric analysis. The exclusive reliance on Web of Science data may introduce coverage bias, potentially underrepresenting research published in journals not indexed by this database or publications in languages other than English. The search strategy, while designed to optimize precision and recall, may have excluded some relevant publications that employ different terminological conventions or focus on related but distinct research questions.

Citation-based measures inherently reflect past research impact rather than current scientific quality or future potential, potentially creating temporal biases that favor older publications over recent contributions. Self-citation patterns and disciplinary citation practices may influence network structures in ways that do not accurately reflect knowledge flows or collaborative relationships. The 20-year temporal scope, while comprehensive for this relatively young field, may not capture important earlier foundational work that established the conceptual framework for OA research.

These limitations are inherent to bibliometric approaches and do not invalidate the principal findings, but rather provide important context for interpreting results and identifying opportunities for complementary analytical approaches. The comprehensive multi-method framework employed in this study helps mitigate individual methodological limitations by providing multiple perspectives on the same underlying research landscape, enhancing the robustness and reliability of principal conclusions.

Finally, while structural variation analysis and co-citation clustering provide valuable insights into the intellectual organization of the field, they do not directly evaluate the quality, reproducibility, or methodological rigor of the underlying studies. Integrating bibliometric findings with systematic reviews or meta-analyses could offer a more comprehensive assessment of research progress.

6. Conclusion

This comprehensive bibliometric analysis of 495 publications spanning 2005-2025 provides the first systematic quantitative assessment of the global research landscape on OA impacts on microbial ecology. The field has demonstrated a clear evolutionary trajectory characterized by three distinct phases: an emergence period (2005–2010) in which foundational concepts were established; an exponential-growth phase (2011–2021), with annual outputs increasing from 17 to 48 articles and cumulative records from 56 to 413; a recent stabilization phase (2022–2025) indicating maturation and strategic consolidation. The knowledge base is highly interdisciplinary, anchored in environmental sciences and integrating oceanography, marine biology, ecology, and microbiology. The global collaboration network spans 53 countries in a multipolar yet hierarchical structure led by China, the United States, and Germany; institutional networks show European leadership—particularly the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel—alongside growing Asia–Pacific contributions led by Xiamen University. Co-authorship analyses identify influential clusters centered on Ulf Riebesell, Kunshan Gao, and John Beardall, whose sustained contributions—together with seminal works by Orr et al. (2005), Kroeker et al. (2013), and multiple publications by Riebesell and colleagues—have shaped the field’s theoretical foundations.

Thematic evolution progressed from basic chemical parameters (CO₂, calcification) to complex biological and ecological processes (community dynamics, physiological responses, food web interaction). Keyword clustering revealed ten major domains centered on “growth,” “elemental ratios,” and “ocean acidification”. Citation-burst analysis indicates that “responses” (strength = 5.32, 2018–2025) is the most active contemporary frontier, reflecting a shift toward ecosystem-scale impact assessment and mechanistic understanding of microbial community restructuring under OA stress. The field’s maturation is evidenced by high network modularity values (Q > 0.8) and strong silhouette scores (S > 0.9), indicating well-defined research clusters with high internal coherence. Future research trajectories point toward four strategic directions: advanced molecular technology integration including multi-omics and single-cell approaches, temporal and spatial scale expansion through global observatory networks, multiple stressor interaction investigations incorporating warming and deoxygenation effects, and ecosystem-level integration connecting molecular processes with biogeochemical cycles. Collectively, the OA–microbe research landscape has matured into a highly internationalized, interdisciplinary domain poised to inform predictions of marine ecosystem responses to global change and to support climate science, marine conservation policy, and Earth-system modeling.

References

- Schönberg, C.H.L.; Fang, J.K.H.; Carreiro-Silva, M.; Tribollet, A.; Wisshak, M.; Norkko, J. Bioerosion: the other ocean acidification problem. ICES Journal of Marine Science 2017, 74, 895-925. [CrossRef]

- Gaylord, B.; Kroeker, K.J.; Sunday, J.M.; Anderson, K.M.; Barry, J.P.; Brown, N.E.; Connell, S.D.; Dupont, S.; Fabricius, K.E.; Hall-Spencer, J.M.; et al. Ocean acidification through the lens of ecological theory. Ecology 2015, 96, 3-15. [CrossRef]

- Doney, S.C.; Fabry, V.J.; Feely, R.A.; Kleypas, J.A. Ocean Acidification: The Other CO2Problem. Annual Review of Marine Science 2009, 1, 169-192. [CrossRef]