Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Cultivation

2.2. Experimental Treatments

2.3. Sampling

2.4. Metabolomic Analysis

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

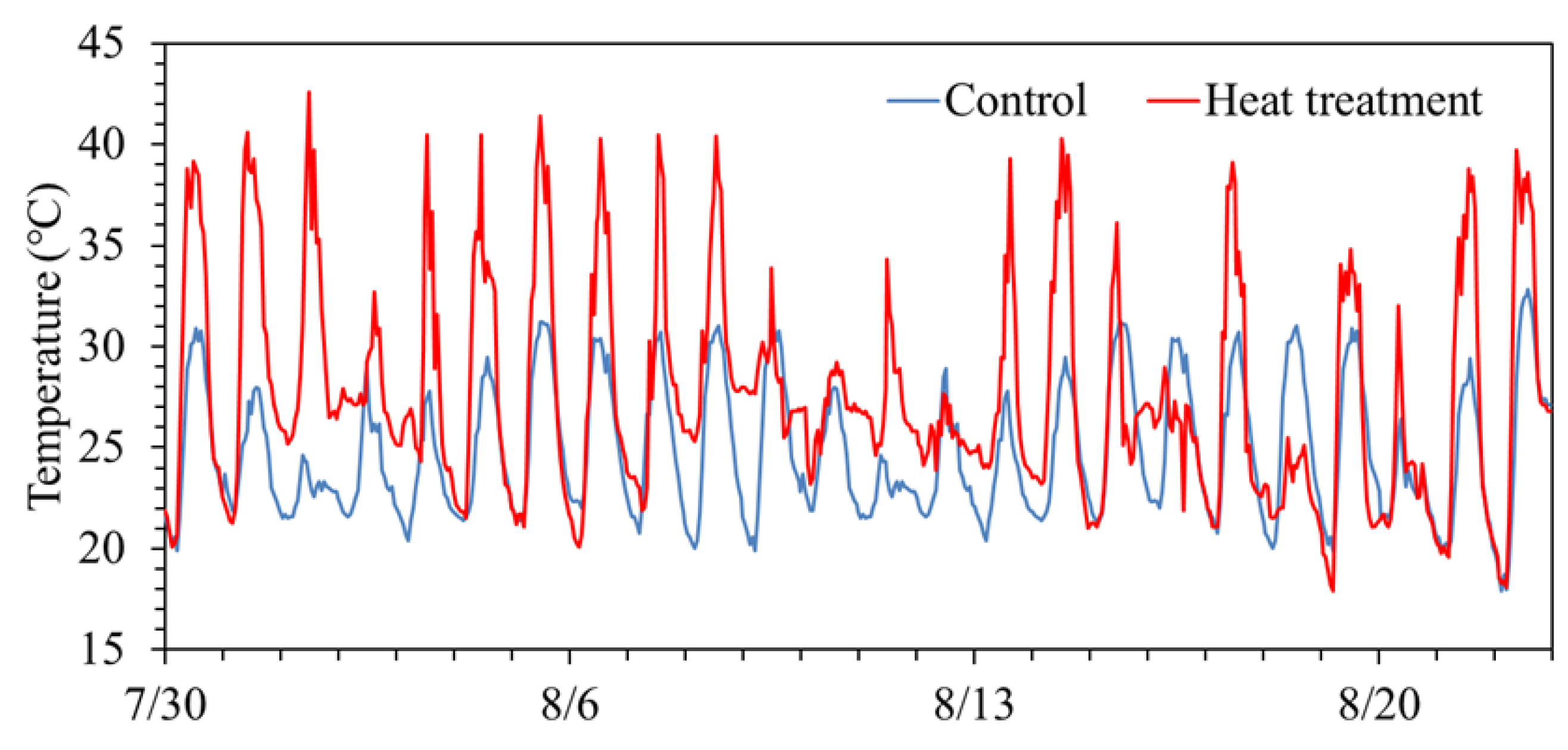

3.1. Temperature Conditions in Treatments

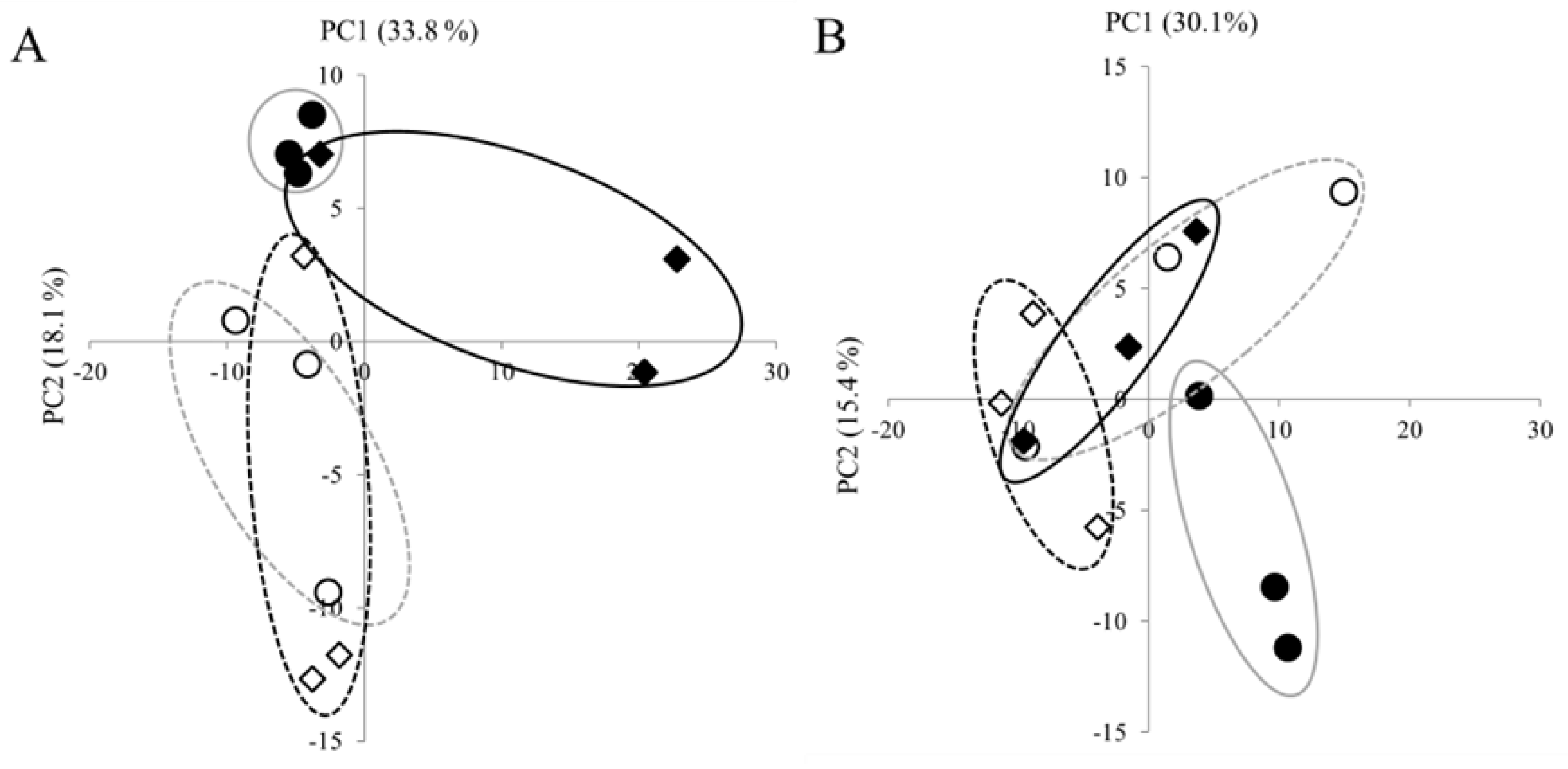

3.2. Effects of High Temperature on Metabolite Profiles in Panicles and Roots

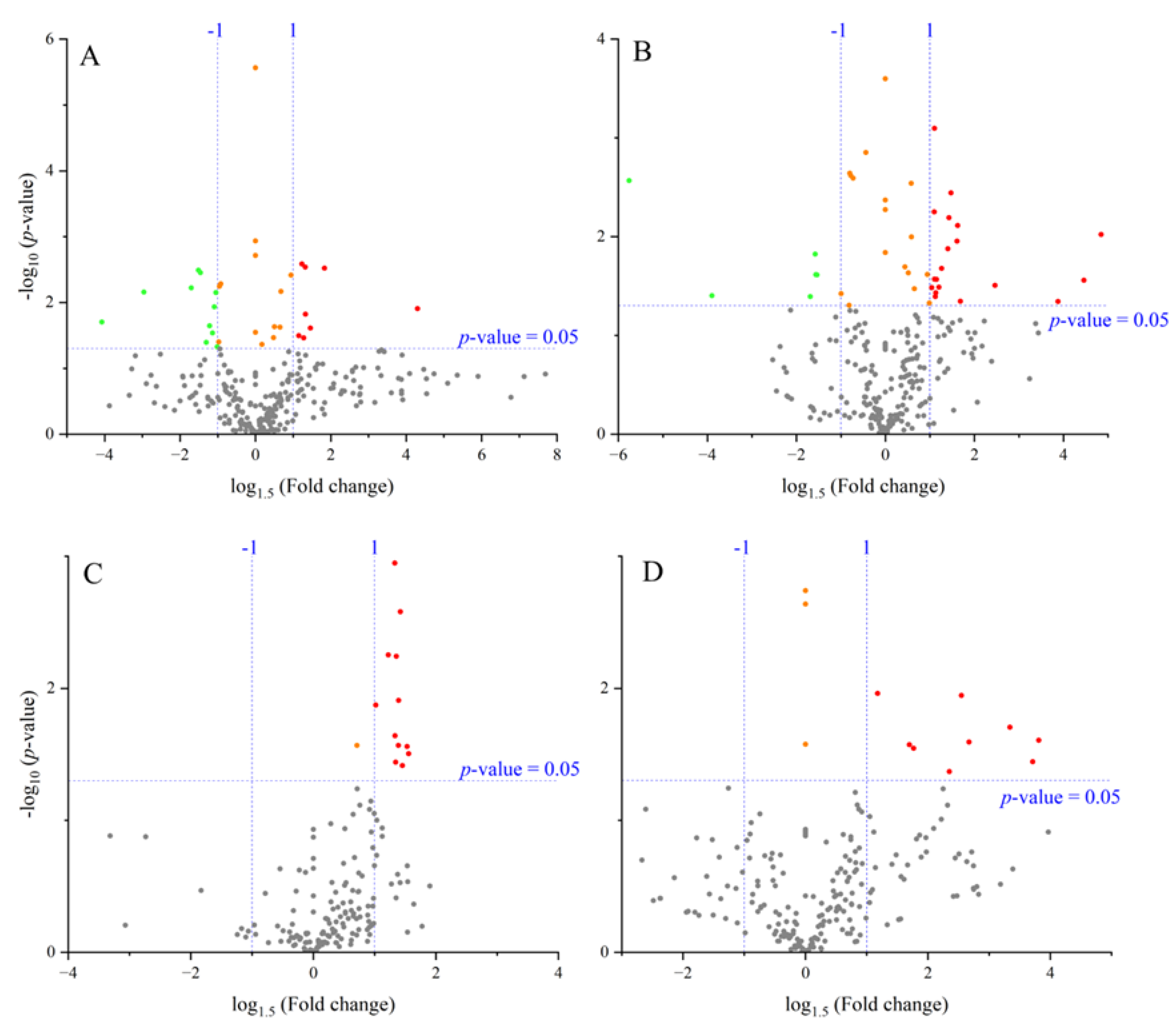

3.3. Metabolite-Level Responses to High Temperature

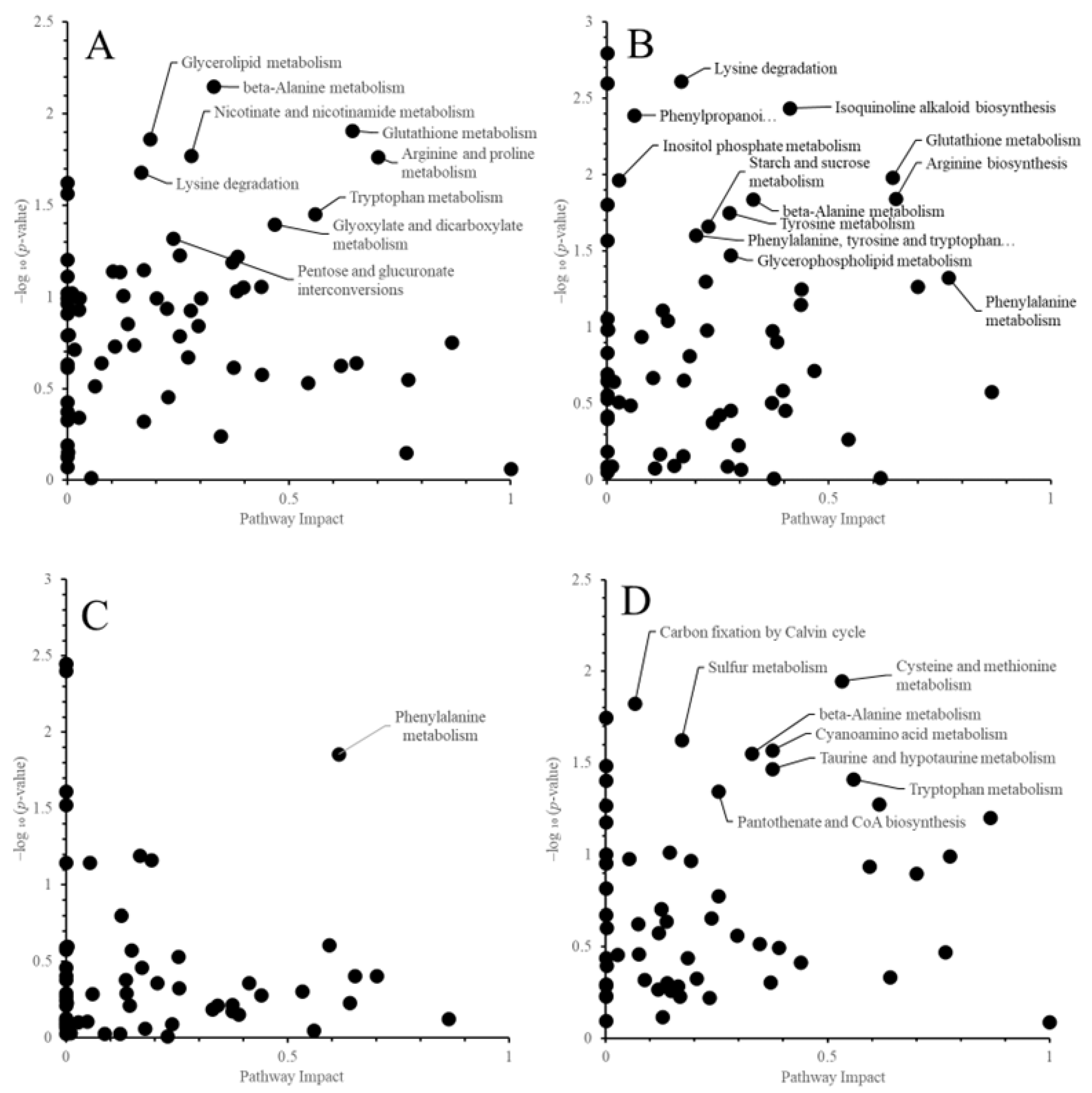

3.4. Pathway-Level Responses to High Temperature

4. Discussion

4.1. Metabolite-Level Responses to High Temperature

4.2. Pathway-Level Responses to High Temperature

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| GSSG | Oxidized glutathione |

References

- Ishigooka, Y.; Kuwagata, T.; Nishimori, M.; Hasegawa, T.; Ohno, H. Spatial characterization of recent hot summers in Japan with agro-climatic indices related to rice production. Journal of Agricultural Meteorology 2011, 67, 209-224. [CrossRef]

- Morita, S.; Wada, H.; Matsue, Y. Countermeasures for heat damage in rice grain quality under climate change. Plant Prod. Sci. 2016, 19, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Tashiro, T.; Wardlaw, I.F. The effect of high temperature at different stages of ripening on grain set, grain weight and grain dimensions in the semi-dwarf wheat ‘Banks’. Ann. Bot. 1990, 65, 51-61. [CrossRef]

- Yamakawa, H.; Hakata, M. Atlas of rice grain filling-related metabolism under high temperature: joint analysis of metabolome and transcriptome demonstrated inhibition of starch accumulation and induction of amino acid accumulation. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010, 51, 795-809. [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.-L.; Zhou, H.-W.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Zhong, P.-A.; Huang, Y.-J. Comparative proteomic analysis of differentially expressed proteins in the early milky stage of rice grains during high temperature stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 655-671. [CrossRef]

- Mitsui, T.; Yamakawa, H.; Kobata, T. Molecular physiological aspects of chalking mechanism in rice grains under high-temperature stress. Plant Prod. Sci. 2016, 19, 22-29. [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Noctor, G. Redox homeostasis and antioxidant signaling: a metabolic interface between stress perception and physiological responses. The plant cell 2005, 17, 1866-1875. [CrossRef]

- Mei, W.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, G.; Deng, H.; Liu, X.; Lu, X.; Wang, F. Exogenous kinetin modulates ROS homeostasis to affect heat tolerance in rice seedlings. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 6252. [CrossRef]

- Mthiyane, P.; Aycan, M.; Mitsui, T. Strategic advancements in rice cultivation: Combating heat stress through genetic innovation and sustainable practices—A review. Stresses 2024, 4, 452-480. [CrossRef]

- Arai-Sanoh, Y.; Ishimaru, T.; Ohsumi, A.; Kondo, M. Effects of soil temperature on growth and root function in rice. Plant Prod. Sci. 2010, 13, 235-242. [CrossRef]

- Zhen, B.; Li, H.; Niu, Q.; Qiu, H.; Tian, G.; Lu, H.; Zhou, X. Effects of combined high temperature and waterlogging stress at booting stage on root anatomy of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Water 2020, 12, 2524. [CrossRef]

- Soga, T.; Ohashi, Y.; Ueno, Y.; Naraoka, H.; Tomita, M.; Nishioka, T. Quantitative metabolome analysis using capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 2003, 2, 488-494. [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Hui, F.; Xu, L.; Viau, C.; Spigelman, A.F.; MacDonald, P.E.; Wishart, D.S.; Li, S. MetaboAnalyst 6.0: towards a unified platform for metabolomics data processing, analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W398-W406. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Shao, Q.; Yin, L.; Younis, A.; Zheng, B. Polyamine function in plants: metabolism, regulation on development, and roles in abiotic stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 9, 1945. [CrossRef]

- Kusano, T.; Berberich, T.; Tateda, C.; Takahashi, Y. Polyamines: essential factors for growth and survival. Planta 2008, 228, 367-381. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Gu, Q.; Dong, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, C.; Hu, W.; Pan, R.; Guan, Y.; Hu, J. Spermidine enhances heat tolerance of rice seeds by modulating endogenous starch and polyamine metabolism. Molecules 2019, 24, 1395. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Chen, W.; Ding, Y. Exogenous spermidine enhances the photosynthetic and antioxidant capacity of rice under heat stress during early grain-filling period. Funct. Plant Biol. 2018, 45, 911-921. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Hu, Q.; Pu, Q.; Chen, M.; Zhu, X.; Gao, C.; Zhou, G.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J. Spermidine enhanced free polyamine levels and expression of polyamine biosynthesis enzyme gene in rice spikelets under heat tolerance before heading. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8976. [CrossRef]

- Noctor, G.; Mhamdi, A.; Chaouch, S.; Han, Y.; Neukermans, J.; Marquez-Garcia, B.; Queval, G.; Foyer, C.H. Glutathione in plants: an integrated overview. Plant, cell & environment 2012, 35, 454-484. [CrossRef]

- Kavi Kishor, P.B.; Suravajhala, P.; Rathnagiri, P.; Sreenivasulu, N. Intriguing role of proline in redox potential conferring high temperature stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 867531. [CrossRef]

- Renzetti, M.; Funck, D.; Trovato, M. Proline and ROS: A unified mechanism in plant development and stress response? Plants 2024, 14, 2. [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Hou, L.; Liu, H.; Zhao, X. OsProDH negatively regulates thermotolerance in rice by modulating proline metabolism and reactive oxygen species scavenging. Rice 2020, 13, 61. [CrossRef]

- Francioso, A.; Baseggio Conrado, A.; Mosca, L.; Fontana, M. Chemistry and biochemistry of sulfur natural compounds: key intermediates of metabolism and redox biology. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020, 8294158. [CrossRef]

- Arnao, M.B.; Hernández-Ruiz, J. Melatonin: a new plant hormone and/or a plant master regulator? Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 38-48. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Yu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Sharma, R.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin synthesis and function: evolutionary history in animals and plants. Frontiers in endocrinology 2019, 10, 441357. [CrossRef]

- Sipari, N.; Lihavainen, J.; Keinänen, M. Metabolite Profiling of Paraquat Tolerant Arabidopsis thaliana Radical-induced Cell Death1 (rcd1)—A Mediator of Antioxidant Defence Mechanisms. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2034. [CrossRef]

- El-Azaz, J.; Moore, B.; Takeda-Kimura, Y.; Yokoyama, R.; Wijesingha Ahchige, M.; Chen, X.; Schneider, M.; Maeda, H.A. Coordinated regulation of the entry and exit steps of aromatic amino acid biosynthesis supports the dual lignin pathway in grasses. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 7242. [CrossRef]

- Ingrisano, R.; Tosato, E.; Trost, P.; Gurrieri, L.; Sparla, F. Proline, cysteine and branched-chain amino acids in abiotic stress response of land plants and microalgae. Plants 2023, 12, 3410. [CrossRef]

- Kishor, P.K.; Suravajhala, R.; Rajasheker, G.; Marka, N.; Shridhar, K.K.; Dhulala, D.; Scinthia, K.P.; Divya, K.; Doma, M.; Edupuganti, S. Lysine, lysine-rich, serine, and serine-rich proteins: link between metabolism, development, and abiotic stress tolerance and the role of ncRNAs in their regulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 546213. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Xian, Y.; Wang, F.; Luo, C.; Song, W.; Xie, S.; Chen, X.; Cao, A.; Li, H.; Liu, H. Comparative transcriptome analysis of leaves during early stages of chilling stress in two different chilling-tolerant brown-fiber cotton cultivars. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0246801. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Kwon, H.; Kim, M.Y.; Lee, S.-H. RNA-seq profiling in leaf tissues of two soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr.) cultivars that show contrasting responses to drought stress during early developmental stages. Mol. Breed. 2023, 43, 42. [CrossRef]

| Control | Heat treatment | Temperature difference |

||

| Fusaotome | Day time | 26.7 | 30.5 | 3.8 |

| Night tine | 22.1 | 24.8 | 2.7 | |

| Aktakomachi | Day time | 26.5 | 31.8 | 5.3 |

| Night tine | 22.3 | 24.6 | 2.3 |

| Fusaotome | Akitakomachi | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substances | Heat / Control | p-value | Substances | Heat / Control | p-value | |

| Increase | ||||||

| Triethanolamine | 5.72 | 0.012 | Ornithine | 7.13 | 0.010 | |

| Spermidine | 2.10 | 0.003 | Pyroglutamine | 6.10 | 0.028 | |

| N-Acetylalanine | 1.81 | 0.025 | Anthranilic acid | 4.81 | 0.045 | |

| Alloisoleucine | 1.71 | 0.015 | N-(1-Deoxy-1-fructosyl)valine | 2.72 | 0.031 | |

| Glutamic acid gamma-methyl ester | 1.71 | 0.003 | Lys | 1.98 | 0.045 | |

| Val | 1.68 | 0.035 | N6-Methyllysine | 1.93 | 0.008 | |

| 2-Methylserine | 1.65 | 0.003 | Spermidine | 1.92 | 0.011 | |

| Citric acid | 1.59 | 0.032 | Theobromine | 1.82 | 0.004 | |

| Oxalic acid | 1.78 | 0.006 | ||||

| Citrulline | 1.77 | 0.013 | ||||

| Saccharopine | 1.67 | 0.021 | ||||

| Arg | 1.63 | 0.033 | ||||

| Asn | 1.59 | 0.027 | ||||

| Sinapic acid | 1.58 | 0.037 | ||||

| Dimethylaminoethanol | 1.58 | 0.040 | ||||

| N-Acetylornithine | 1.56 | 0.027 | ||||

| Gln | 1.56 | 0.001 | ||||

| Nω-Methylarginine | 1.56 | 0.006 | ||||

| Isocitric acid | 1.52 | 0.033 | ||||

| Decrease | ||||||

| Thiamine phosphate | 0.19 | 0.020 | Cadaverine | 0.10 | 0.003 | |

| Serotonin | 0.30 | 0.007 | γ-Glu-Cys | 0.21 | 0.040 | |

| Threonic acid | 0.50 | 0.006 | Quinic acid | 0.50 | 0.040 | |

| 2-Deoxyribonic acid | 0.54 | 0.003 | Shikimic acid | 0.53 | 0.015 | |

| Glyceric acid | 0.55 | 0.004 | Sedoheptulose 7-phosphate | 0.53 | 0.024 | |

| AMP | 0.59 | 0.040 | Galacturonic acid | 0.54 | 0.024 | |

| Phosphoenolpyruvic acid | 0.61 | 0.023 | ||||

| 3-Phosphoglyceric acid | 0.63 | 0.029 | ||||

| Tyrosine methyl ester | 0.64 | 0.012 | ||||

| Ribulose 5-phosphate | 0.65 | 0.007 | ||||

| Ascorbate 2-glucoside | 0.66 | 0.047 | ||||

| Fusaotome | Akitakomachi | |||||

| Substances | Heat / Control | p-value | Substances | Heat / Control | p-value | |

| Increase | ||||||

| Lys | 1.88 | 0.031 | Glucuronic acid | 4.69 | 0.025 | |

| Arg | 1.86 | 0.028 | Ile-Pro-Pro | 4.51 | 0.036 | |

| Met | 1.80 | 0.038 | Thiaproline | 3.87 | 0.020 | |

| Val | 1.78 | 0.003 | 2-Methylthiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid | 2.96 | 0.026 | |

| Leu | 1.76 | 0.012 | Uric acid | 2.81 | 0.011 | |

| γ-Glu-Phe | 1.76 | 0.027 | Cysteine glutathione disulfide | 2.59 | 0.043 | |

| Ile | 1.73 | 0.006 | N-Acetylgalactosamine | 2.05 | 0.028 | |

| γ-Glu-Ile γ-Glu-Leu |

1.72 | 0.036 | N-Acetyllysine | 1.99 | 0.027 | |

| Phe | 1.72 | 0.023 | Oxalic acid | 1.61 | 0.011 | |

| Pro | 1.71 | 0.001 | ||||

| γ-Glu-Val | 1.64 | 0.006 | ||||

| Thr | 1.51 | 0.013 | ||||

| Fusaotome | Akitakomachi | |||||||

| Pathway | Pathway Impact |

–log ₁₀ (p-value) |

Score | Pathway Impact |

–log ₁₀ (p-value) |

Score | Score difference |

|

| Tryptophan metabolism | 0.56 | 1.45 | 0.81 | 0.37 | 0.98 | 0.36 | 0.45 | |

| Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.38 | |

| Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism | 0.28 | 1.77 | 0.49 | 0.28 | 0.46 | 0.13 | 0.37 | |

| Arginine and proline metabolism | 0.70 | 1.77 | 1.24 | 0.70 | 1.27 | 0.89 | 0.35 | |

| Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | 0.47 | 1.40 | 0.65 | 0.47 | 0.72 | 0.34 | 0.32 | |

| Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | 0.38 | 1.22 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.18 | 0.28 | |

| Pyruvate metabolism | 0.30 | 0.99 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.28 | |

| Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | 0.37 | 1.19 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.51 | 0.19 | 0.25 | |

| Taurine and hypotaurine metabolism | 0.38 | 0.61 | 0.23 | 0.38 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.23 | |

| Pentose and glucuronate interconversions | 0.24 | 1.32 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.09 | 0.22 | |

| Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis | 0.25 | 1.23 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.11 | 0.20 | |

| Glycerolipid metabolism | 0.19 | 1.86 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.81 | 0.15 | 0.20 | |

| Glycolysis or Gluconeogenesis | 0.40 | 1.05 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.59 | 0.23 | 0.19 | |

| Vitamin B6 metabolism | 0.30 | 0.84 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.18 | |

| Thiamine metabolism | 0.27 | 0.67 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.16 | |

| Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.87 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.15 | |

| Cysteine and methionine metabolism | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.29 | 0.54 | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.14 | |

| Riboflavin metabolism | 0.12 | 1.14 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.11 | |

| beta-Alanine metabolism | 0.33 | 2.15 | 0.71 | 0.33 | 1.84 | 0.61 | 0.10 | |

| One carbon pool by folate | 0.15 | 0.74 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.10 | |

| Fusaotome | Akitakomachi | |||||||

| Pathway | Pathway Impact |

–log ₁₀ (p-value) |

Score | Pathway Impact |

–log ₁₀ (p-value) |

Score | Score difference |

|

| Isoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis | 0.76 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.41 | 2.43 | 1.00 | -0.89 | |

| Arginine biosynthesis | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.42 | 0.65 | 1.84 | 1.20 | -0.78 | |

| Phenylalanine metabolism | 0.77 | 0.55 | 0.42 | 0.77 | 1.33 | 1.02 | -0.60 | |

| Tyrosine metabolism | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 1.75 | 0.48 | -0.40 | |

| Pyrimidine metabolism | 0.44 | 0.58 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 1.25 | 0.55 | -0.29 | |

| Starch and sucrose metabolism | 0.23 | 0.46 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 1.66 | 0.38 | -0.27 | |

| Lysine degradation | 0.17 | 1.68 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 2.61 | 0.43 | -0.15 | |

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 0.28 | 0.93 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 1.47 | 0.41 | -0.15 | |

| Phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis | 0.20 | 0.99 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 1.60 | 0.32 | -0.12 | |

| Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis | 0.06 | 0.51 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 2.39 | 0.15 | -0.12 | |

| Purine metabolism | 0.25 | 0.79 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 1.30 | 0.29 | -0.09 | |

| Glutathione metabolism | 0.64 | 1.91 | 1.23 | 0.64 | 1.98 | 1.28 | -0.05 | |

| Inositol phosphate metabolism | 0.03 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 1.97 | 0.05 | -0.04 | |

| Pentose phosphate pathway | 0.44 | 1.06 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 1.15 | 0.50 | -0.04 | |

| Butanoate metabolism | 0.14 | 0.85 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 1.04 | 0.14 | -0.03 | |

| Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.49 | 0.03 | -0.03 | |

| Biotin metabolism | 0.08 | 0.64 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.94 | 0.07 | -0.02 | |

| Biosynthesis of various plant secondary metabolites | 0.13 | 1.01 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 1.11 | 0.14 | -0.01 | |

| Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism | 0.22 | 0.94 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.98 | 0.22 | -0.01 | |

| Lipoic acid metabolism | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Fusaotome | Akitakomachi | |||||||

| Pathway | Pathway Impact |

–log ₁₀ (p-value) |

Score | Pathway Impact |

–log ₁₀ (p-value) |

Score | Score difference |

|

| Phenylalanine metabolism | 0.62 | 1.86 | 1.14 | 0.62 | 1.28 | 0.78 | 0.36 | |

| Lysine degradation | 0.17 | 1.19 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.16 | |

| Phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis | 0.19 | 1.16 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.97 | 0.19 | 0.04 | |

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 0.15 | 0.58 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.03 | |

| Biosynthesis of various plant secondary metabolites | 0.13 | 0.80 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.71 | 0.09 | 0.01 | |

| Starch and sucrose metabolism | 0.13 | 0.38 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.01 | |

| Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis | 0.05 | 1.15 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.98 | 0.05 | 0.01 | |

| Propanoate metabolism | 0.00 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Glucosinolate biosynthesis | 0.00 | 2.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.75 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation | 0.00 | 2.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.75 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Valine, leucine and isoleucine biosynthesis | 0.00 | 2.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.49 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Tropane, piperidine and pyridine alkaloid biosynthesis | 0.00 | 1.61 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.95 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| D-Amino acid metabolism | 0.00 | 1.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Sphingolipid metabolism | 0.00 | 1.15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Ubiquinone and other terpenoid-quinone biosynthesis | 0.00 | 0.58 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Selenocompound metabolism | 0.00 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Caffeine metabolism | 0.00 | 0.41 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Inositol phosphate metabolism | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Monobactam biosynthesis | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Porphyrin metabolism | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Fusaotome | Akitakomachi | |||||||

| Pathway | Pathway Impact |

–log ₁₀ (p-value) |

Score | Pathway Impact |

–log ₁₀ (p-value) |

Score | Score difference |

|

| Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism | 0.863 | 0.125 | 0.108 | 0.867 | 1.202 | 1.042 | -0.934 | |

| Cysteine and methionine metabolism | 0.532 | 0.307 | 0.164 | 0.532 | 1.947 | 1.036 | -0.873 | |

| Tryptophan metabolism | 0.558 | 0.051 | 0.028 | 0.558 | 1.410 | 0.787 | -0.758 | |

| Cyanoamino acid metabolism | 0.375 | 0.220 | 0.083 | 0.375 | 1.570 | 0.589 | -0.506 | |

| Arginine biosynthesis | 0.651 | 0.407 | 0.265 | 0.775 | 0.992 | 0.769 | -0.504 | |

| Taurine and hypotaurine metabolism | 0.375 | 0.177 | 0.066 | 0.375 | 1.466 | 0.550 | -0.484 | |

| beta-Alanine metabolism | 0.329 | 0.191 | 0.063 | 0.329 | 1.551 | 0.511 | -0.448 | |

| Arginine and proline metabolism | 0.700 | 0.409 | 0.286 | 0.700 | 0.897 | 0.628 | -0.342 | |

| Isoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis | 0.412 | 0.363 | 0.149 | 0.765 | 0.468 | 0.358 | -0.209 | |

| Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis | 0.253 | 0.532 | 0.135 | 0.253 | 1.345 | 0.341 | -0.206 | |

| Sulfur metabolism | 0.171 | 0.464 | 0.079 | 0.171 | 1.626 | 0.278 | -0.199 | |

| Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism | 0.593 | 0.610 | 0.362 | 0.593 | 0.934 | 0.554 | -0.192 | |

| Vitamin B6 metabolism | 0.229 | 0.013 | 0.003 | 0.295 | 0.562 | 0.166 | -0.163 | |

| Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism | 0.238 | 0.094 | 0.022 | 0.238 | 0.656 | 0.156 | -0.134 | |

| Pyrimidine metabolism | 0.390 | 0.154 | 0.060 | 0.390 | 0.495 | 0.193 | -0.133 | |

| Pyruvate metabolism | 0.144 | 0.214 | 0.031 | 0.144 | 1.012 | 0.145 | -0.114 | |

| One carbon pool by folate | 0.254 | 0.326 | 0.083 | 0.254 | 0.773 | 0.196 | -0.113 | |

| Tyrosine metabolism | 0.205 | 0.363 | 0.075 | 0.346 | 0.514 | 0.178 | -0.103 | |

| Carbon fixation by Calvin cycle | 0.059 | 0.290 | 0.017 | 0.065 | 1.823 | 0.119 | -0.102 | |

| Purine metabolism | 0.179 | 0.065 | 0.012 | 0.184 | 0.436 | 0.080 | -0.069 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).