1. Introduction

Aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃), commonly known as alumina, is a ceramic material widely used in numerous technological and industrial applications due to its excellent physical and mechanical properties [

1]. Typically, alumina exhibits low density and exceptional hardness, good thermal conductivity, high resistivity, and notable dielectric strength [

2,

3]. Moreover, from a chemical standpoint, alumina is highly resistant to corrosion and oxidation, showing excellent wear resistance and a high degree of biocompatibility [

4]. These properties make alumina an ideal candidate for cutting-edge applications in automotive, aerospace, and biomedicine, where the control of surface wettability is particularly challenging [

5,

6,

7].

Alumina surfaces with hydrophobic behavior, characterized by contact angles greater than 90°, have attracted a lot of attention due to their potential applications in microfluidics, lab-on-chip devices and as functional surfaces for the aerospace and automotive industries [

8]. Conversely, alumina hydrophilicity, typically associated with contact angles lower than 90°, has been exploited to promote cell adhesion and osseointegration [

9,

10], or in crucial aspects of biomedical applications such as joint prostheses (e.g., dental or hip implants) [

11,

12]. In this context, a comprehensive study of long-term hydrophilicity of alumina appears to be still missing in the current scientific literature.

Over the years, several methods have been developed to adjust the wettability response of alumina via surface modifications, including polymer coatings, UV irradiation, chemical-assisted and plasma treatments [

13,

14,

15]. However, those approaches often present some limitations in terms of process complexity and fabrication times. Laser processing is known to overcome these disadvantages and intrinsically guarantees improved precision, efficiency, and surface quality [

16,

17]. Noteworthy, laser processing has been proven to be highly effective in producing hydrophilic surfaces. Triantafyllidis

et al. [

19] experimentally studied the impact of CO

2 induced melting and re-solidification of refractory Al₂O₃ composite ceramics, observing a decrease of the fluid contact angle from 41.4° to 26.9°, which they attributed to an increase in surface roughness in relation to the laser power density. However, the authors exclusively focused on analyzing the initial modification of the contact angle, without evaluating the long-term stability of the laser-induced hydrophilicity. Jagdheesh

et al. [

8] incidentally observed highly hydrophilic properties on Al₂O₃ surfaces immediately after laser texturing with picosecond pulses and Kunz

et al. [

19] used femtosecond laser pulses to modify the wetting behavior on composite alumina, reporting a significant contact angle reduction but no evidence on hydrophilicity evolution over time. Cao

et al. [

20] and Wang

et al. [

21] reported on their experimental investigations with femtosecond laser pulses on alumina, demonstrating a threshold fluence of 10.39 J/cm² and 8.32 J/cm², respectively, and a hydrophilic contact angle of 57.9° after 240 hours and 56° after 360 hours. However, their results on time-dependent hydrophilicity were limited to a period of few days, without addressing whether that would finally stabilize or decay over time.

In this work, we address the entire range of wettability, from hydrophobicity to hydrophilicity, induced by femtosecond laser pulses on alumina surfaces, focusing on the evolution and temporal persistence of surface hydrophilicity over a period of six weeks, without the application of additional surface treatments.

2. Materials and Methods

The material used in this study was ADS-96R alumina (Al₂O₃) from CoorsTek, a ceramic substrate widely adopted as an industrial standard [

22]. Samples had dimensions of 88.9 × 88.9 mm² and a thickness of 0.64 mm. To remove surface impurities, all samples were cleaned before laser texturing by ultrasonication in acetone (AR, > 99.5%), ethanol (AR, 95%), and distilled water for 15 minutes each. Finally, the samples were air-dried at 70 °C.

To modify the morphology of the sample surface, we carried out laser direct writing in ambient air by employing a versatile solid-state laser Pharos SP 1.5 femtosecond laser system (Light Conversion), which offered a wide range of adjustable parameters (pulse duration, fluence, repetition rate, etc.) and significant flexibility for experimental optimization. The pulse duration was set to 190 fs, with a central wavelength of 1030 nm, and the laser repetition rate could be varied from single-shot operation up to 1 MHz. The emitted beam was nearly diffraction-limited (M² = 1.3) and linearly polarized. The laser beam was directed onto the sample surface using a galvo scanner (IntelliSCANN 14, SCAN-LAB) combined with a telecentric f-theta lens of 100 mm focal length, enabling precise control over the scanning process. The beam waist was measured to be 13.2 ± 0.1 μm (1/e2 peak intensity) by a CCD camera FireWire BeamPro (Model 2523 by Photon Inc.).

In the following section, we determined the ablation threshold of alumina (Al₂O₃) in our experimental conditions and optimized the surface morphology to demonstrate for the first time to our best knowledge a stable and durable hydrophilicity induced by femtosecond laser micro-nanotexturing.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Ablation Threshold of Alumina with Femtosecond Laser Pulses

We have estimated the ablation threshold of alumina in our experimental conditions using the Liu method [

23], which is based on measuring the diameters of laser-induced craters formed on the surface of our samples. According to this method, the relationship between the ablation threshold fluence for N consecutive pulses and the crater sizes is expressed by the following equation:

where F

0 is the peak fluence, defined as:

and ω

0 is the Gaussian beam radius at 1/e

2, E

p is the pulse energy. Through linear fitting of Equation (1), the radius of the Gaussian laser beam and the threshold fluence for multiple pulses, F

th(N), were evaluated for each number of pulses N and repetition rate in

Table 1. Specifically, seven series of ablation craters were generated, each consisting of five matrices produced at different pulse energies. Within each matrix, each row was ablated with an increasing number of laser pulses, and the repetition frequency was kept constant and upper limited to 50 kHz by the maximum pulse energy available in our experiments. All parameters used for each series, matrix, and row are summarized in

Table 1.

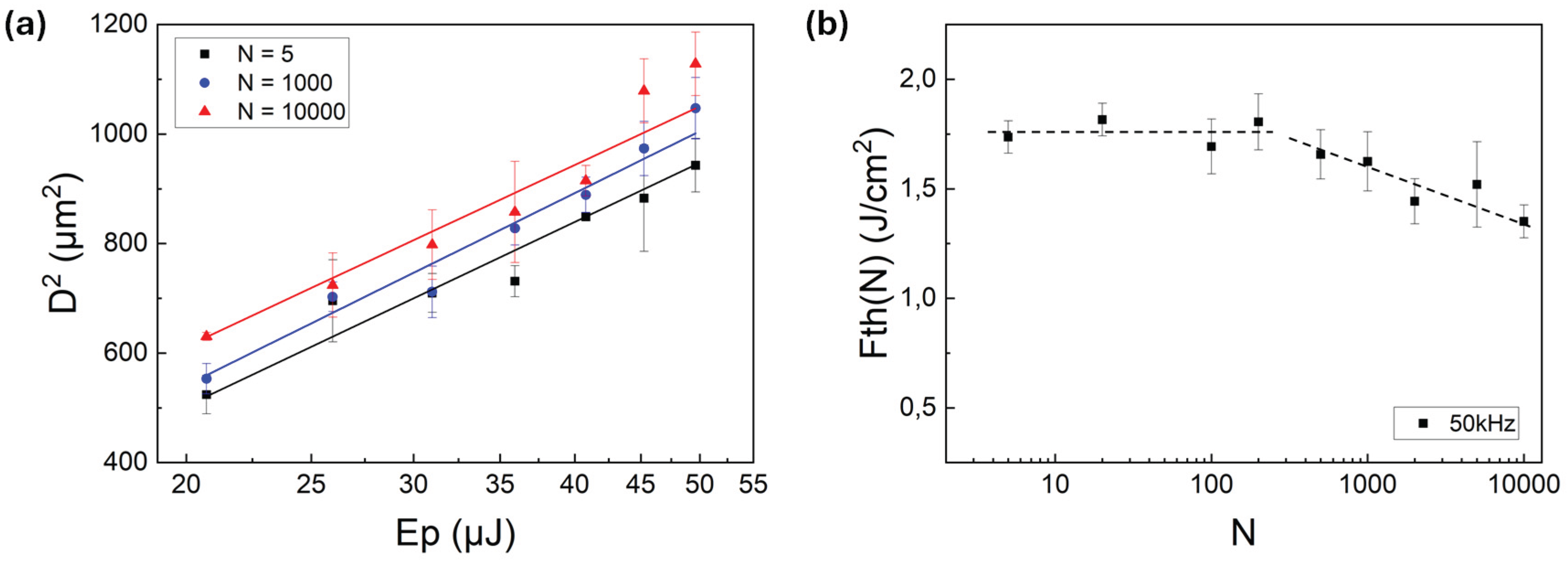

Figure 1(a) shows the semi-logarithmic graph of the squared crater diameter (D

2) as a function of pulse energy (E

p) for different pulse numbers (N) at the highest repetition rate (i.e. 50 kHz). Morphological and optical characterization of the craters were carried out using a Nikon Eclipse ME600 optical microscope equipped with ImageJ software.

It was observed that as both pulse energy and the number of pulses increased, the squared crater diameter increased linearly, indicating that the ablation area also increased with higher energy. By extrapolating the ablation threshold fluence for each pulse number from the intercept of the linear fitting in

Figure 1(a), we calculated an average ablation threshold of 1.63 ± 0.16 J/cm².

Figure 1(b) shows the relationship between multi-pulse ablation threshold fluence F

th(N) and number of laser pulses N at the same repetition frequency of 50 kHz. It was observed that for N values less than or equal to 200 pulses, the threshold fluence F

th(N) remained nearly constant, in accordance with results shown by Andriukaitis

et al. [

24], who analyzed the threshold fluence in similar conditions to reveal a rapid saturation in the range 100÷1000 fs-pulses, both in single-pulse and in MHz/GHz burst regime. Nonetheless, a slight decrease in the multi-pulse ablation threshold fluence was shown in

Figure 1(b) for N > 200 pulses, which can be rather interpreted as the incubation effect [

25,

26,

27].

3.2. Role of Femtosecond Laser Microtexturing on Alumina Wettability

We employed an effective strategy of laser processing [

28,

29] to access various wettability regimes on Al

2O

3 targets and establish a long-term stability of their hydrophilic character. Specifically, we modified the surface morphology with femtosecond laser pulses to create an optimal periodic geometry, which was induced by overlapping cross scanning patterns to generate square-shaped structures, separated by a hatch of 150 μm, followed by a 45° square-shaped pattern.

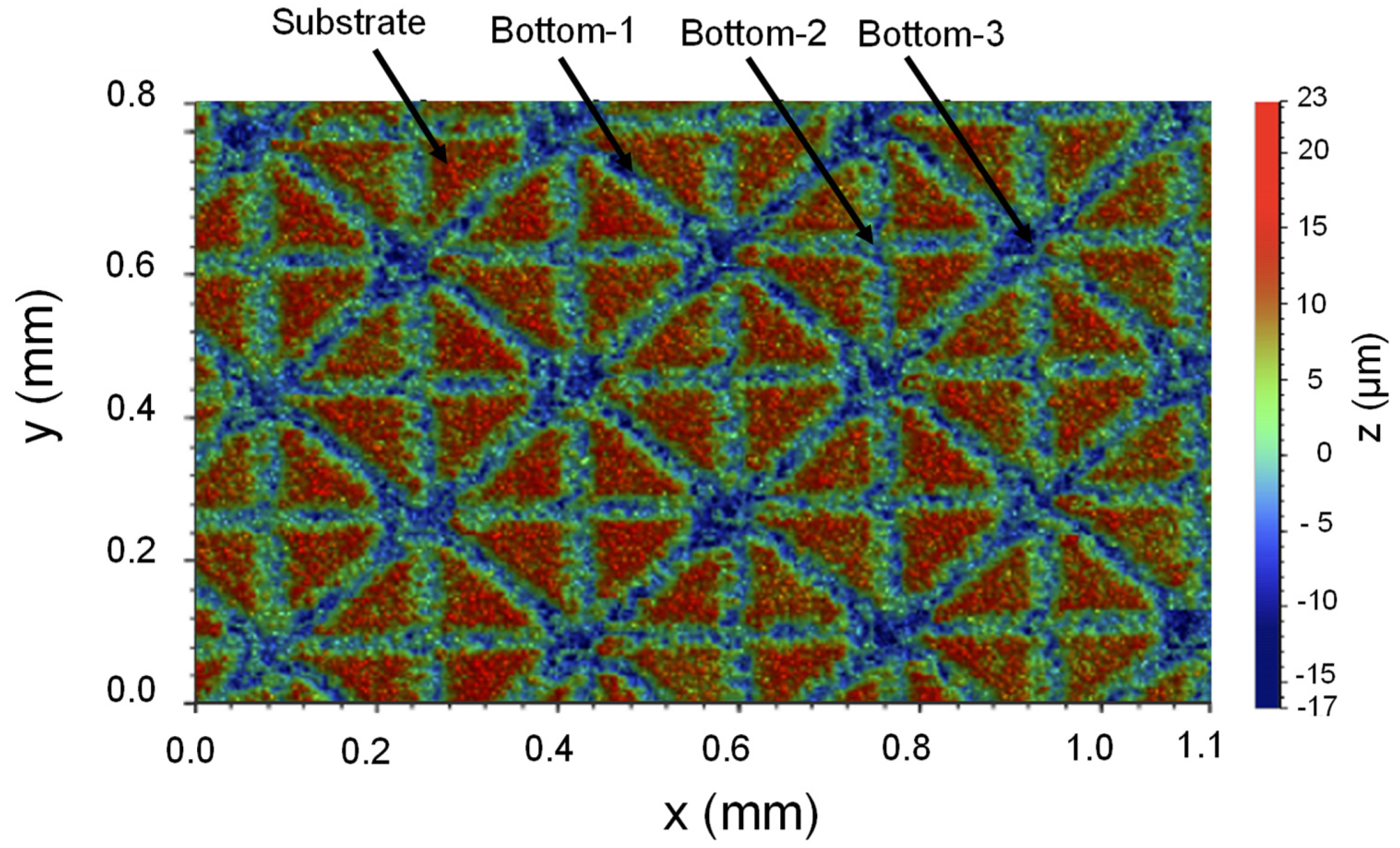

Figure 2 shown a representative contour plot of those micro-nanostructures as taken by a profilometer (CountourGT InMotion; Bruker, USA), with laser parameters being optimized at the maximum available pulse energy of 49.6 µJ for a fixed rep. rate of 50 kHz. The beam scanning speed was set at 20 mm/s to inscribe periodic grooves with a depth of 17.1 ± 0.1 µm relative to the intact surface, which in turn featured a roughness of about 3.4 ± 0.1 µm. In the 3D image, different regions of the textured surface are highlighted: the pristine substrate and three areas labeled bottom-1, bottom-2, and bottom-3, corresponding to one, two, and four laser passes over the same spot, respectively. This variation in the number of laser passes was intentionally set in accordance with our laser strategy. Consequently, some areas received multiple overlaps of laser exposure, leading to different groove depths and roughness.

We investigated various scanning speeds (ranging from 20 to 750 mm/s) at a fixed pulse energy and repetition frequency, aiming to fine-tune the groove depth only. In

Table 2, we summarized the outcome: the groove depth became progressively shallower with increasing scanning speed, as expected [

29].

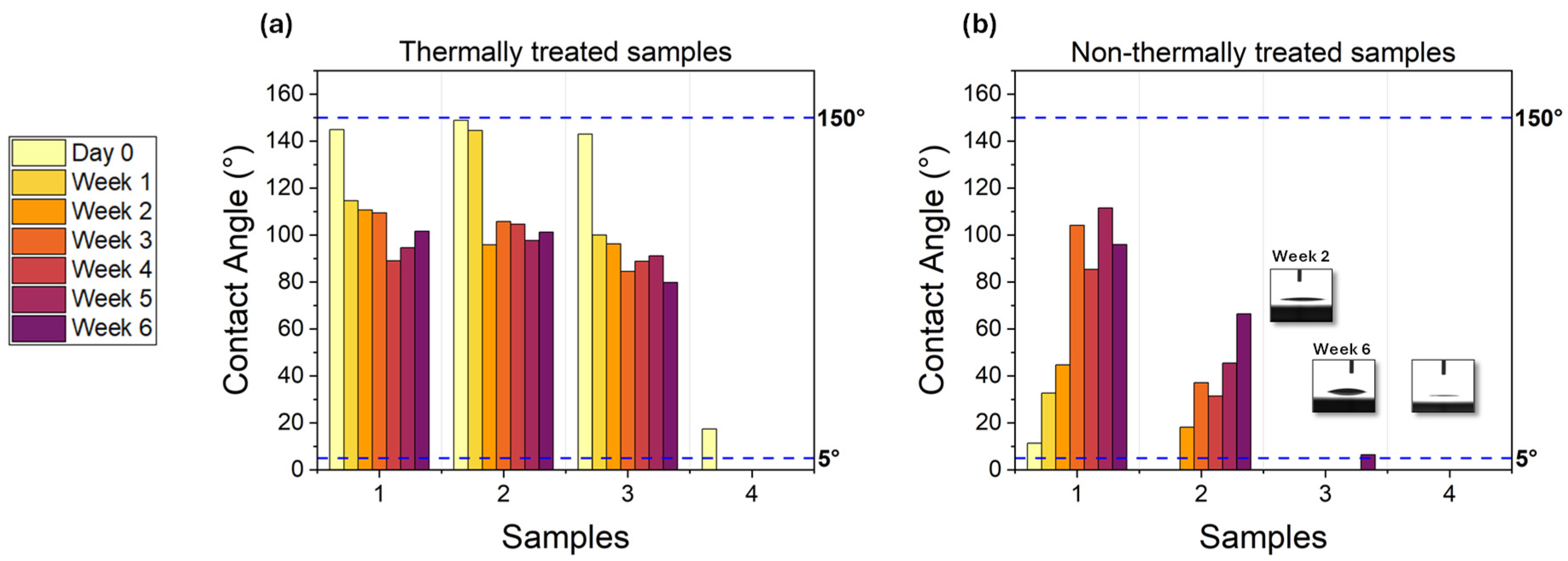

Figure 3 shows how the wetting response of our samples in

Table 2 would evolve over a time-interval of 6 weeks in air atmosphere. Specifically, the wettability dynamics of laser-textured surfaces with increasing groove depth (see labels 1 to 4 in

Figure 3) was assessed by static water contact angle measurements using an Optical Contact Angle Goniometer (OCA 25 by Dataphysics). To ensure a metrological grade measurement, a set of 3 µL water droplets were deposited on several areas of each sample, and the average value of the resulting contact angles was evaluated. Noteworthy, samples were stored at room temperature between consecutive measurements, and the contact angles were monitored on daily basis, from day 0 to week 6, although only weekly values have been plotted in

Figure 3 for clarity.

The comparison between contact angle dynamics of both thermally and non-thermally treated samples is shown in

Figure 3(a) and 3(b), respectively. The thermal treatment consisted of heating the samples at 120 ± 1 °C for 3 hours in ambient air, as widely employed to promote the wettability stabilization of similar laser-textured structures [

28,

29,

30,

31]. This thermal aging procedure, with rather mild annealing conditions, was here purposely adopted to accelerate the surface enrichment with oxides and organic contaminants, and to expedite the settlement of the wetting response immediately after laser texturing (i.e., without waiting for a standard room temperature aging period of tens of days).

Initially, samples 1–3 in

Figure 3(a) exhibited an almost superhydrophobic regime induced by the thermal treatment, with contact angles as high as 148.9 ± 0.1°, in accordance with results previously observed by Lang

et al. in similar conditions [

32]. However, such a hydrophobic character was not persistent, with contact angles progressively drifting to a saturation value around 90° within 6 weeks of testing. This behaviour is consistent with the time-dependent chemistry stabilization expected at the surface of thermally treated samples [

28,

30]. Similarly, a comparable trend of monotonic reduction in the contact angle was revealed on pristine (i.e. unstructured) samples subjected to thermal annealing, which displayed an initial contact angle of 83.4 ± 0.1° reaching a plateau point of 46.3 ± 0.1° after few days. Analogously, a plateau point of 46.1 ± 0.1° was measured on unstructured and non-thermally treated samples (not shown in

Figure 3).

Remarkably, sample 4 in

Figure 3(a) displayed an unexpected hydrophilicity on day 0, rapidly evolving into a steady super-hydrophilic regime which lasted all over the testing time and featured an average contact angle always below 5°. We ascribed this behavior to the laser-induced morphology at the surface and speculated on the role played by grooves with certain depth and roughness, which may accommodate more fluid into the microstructures, thus promoting a hydrophilic character of the sample.

Figure 3(b) shows wettability dynamics on non-thermally treated samples: a gradual increase of the contact angle from day 0 to the sixth week was plausibly due to natural aging and surface contamination in air atmosphere. Despite such a gradual increase, all samples except for sample 1 maintained a contact angle below 90° throughout the observation period, demonstrating a persistent hydrophilicity of Al₂O₃ surfaces via femtosecond laser texturing. Noteworthy, samples 3 and 4 exhibited a long-lasting superhydrophilic regime (< 5°), with their specific morphology fostering very-low contact angles in time, with values even below the instrument sensitivity. Although the comparison with sample 3 in

Figure 3(a) may appear to some extent controversial, these preliminary results validated the explicit correlation between fs-laser strategy and long-term superhydrophilicity of alumina, opening to more refined design of micro-nanostructure at the surface to establish a robust control on the Al₂O₃ wettability.

4. Conclusions

In summary, this study demonstrates that femtosecond laser micro-nanoprocessing can effectively modulate the wettability of alumina surfaces, enabling long-lasting hydrophilicity on Al₂O₃ substrates without the need for additional chemical or physical treatments.

The average ablation threshold was accurately determined under our experimental conditions to identify an optimal operational strategy for fs-laser tailoring the surface morphology of alumina. By fine-tuning the pattern design and systematically varying groove depth and roughness, we established a direct correlation between surface morphology and wetting response of alumina. Notably, non-thermally treated samples maintained a super- or hydrophilic state throughout the entire testing period, except for samples with shallow grooves. Aging period and fs-laser strategy may be refined to settle hydrophilicity endurance on thermally treated samples, except for samples with deep grooves.

These preliminary outcomes provide a valuable starting point for future investigations and address key gaps in the current scientific literature, demonstrating a long-term stability of hydrophilic behavior on alumina over much longer period than previously reported. Such a capability to control and stabilize hydrophilic states on alumina opens new opportunities for biomedical applications. In particular, the enhanced and durable hydrophilicity can promote cell adhesion and osseointegration, which are critical for joint prostheses, such as dental or hip implants, where long-term stability and reproducibility of wetting properties are essential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and F.P.M.; methodology, A.S., F.P.M., C.G.; software, A.S.; formal analysis, A.S., F.P.M., C.G.; L.P., M.P.; investigation, A.S. L.P., M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., F.P.M; writing—review and editing, F.P.M., C.G, A.V. and A.A.; visualization, A.S., L.P., M.P.; supervision, F.P.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by MUR in the framework of the PRIN 2022 PNRR Project “Surface and Interface acoustic wave-driven Microfluidic devices BAsed on fs-laser technology for particle sorting (SIMBA)” (grant number: Prot. P2022LMRKB) and the project “Quantum Sensing and Modeling for One-Health (QuaSiModO)” (CUP: H97G23000100001).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Auerkari, P. Mechanical and physical properties of engineering alumina ceramics, Vol. 23; Technical Research Centre of Finland: Espoo, Finland, 1996.

- Wang, X.C.; Zheng, H.Y.; Chu, P.L.; Tan, J.L.; Teh, K.M.; Liu, T.; Tay, G.H. Femtosecond laser drilling of alumina ceramic substrates. Appl. Phys. A 2010, 101, 271–278 . [CrossRef]

- Perrie, W.; Rushton, A.; Gill, M.; Fox, P.; O’Neill, W. Femtosecond laser micro-structuring of alumina ceramic. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2005, 248, 213–217. [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Xia, Y.; Zheng, S.; Yang, C.; Qi, H.; Jaffery, S.H.I. Effect of surface modification on wettability and tribology by laser texturing in Al₂O₃. Appl. Opt. 2021, 60, 4434–4442.

- Liang, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Li, K.; Xiang, Y.; Jia, X. Laser drilling of alumina ceramic substrates: A review. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 167, 109828. [CrossRef]

- Rung, S.; Häcker, N.; Hellmann, R. Micromachining of alumina using a high-power ultrashort-pulsed laser. Materials 2022, 15, 5328. [CrossRef]

- Leese, H.; Bhurtun, V.; Lee, K.P.; Mattia, D. Wetting behaviour of hydrophilic and hydrophobic nanostructured porous anodic alumina. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2013, 420, 53–58. [CrossRef]

- Jagdheesh, R. Fabrication of a superhydrophobic Al₂O₃ surface using picosecond laser pulses. Langmuir 2014, 30, 12067–12073.

- Silva, J. R. S.; Santos, L. N. R. M.; Farias, R. M. C.; Sousa, B. V.; Neves, G. A.; Menezes, R. R. Alumina applied in bone regeneration: Porous α-alumina and transition alumina. Cerâmica, 2022, 68, 355-363. [CrossRef]

- Rafikova, G.; Piatnitskaia, S.; Shapovalova, E.; Chugunov, S.; Kireev, V.; Ialiukhova, D.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Interaction of ceramic implant materials with immune system. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4200. [CrossRef]

- Solarino, G.; Vicenti, G.; Piazzolla, A.; Piconi, C.; Moretti, B. Ceramic-Ceramic Hip Arthroplasty. Ital. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2013, 142–152.

- Al-Moameri, H.H.; Nahi, Z.M.; Rzaij, D.R.; Al-Sharify, N.T. A review on the biomedical applications of alumina. J. Eng. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 24, 28–36. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Liu, X.; Akbulut, O.; Hu, J.; Suib, S.L.; Kong, J.; Stellacci, F. Superwetting nanowire membranes for selective absorption. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008, 3, 332–336. [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, T.; Saito, N.; Takai, O. Correlation of cell adhesive behaviors on superhydrophobic, superhydrophilic, and micropatterned superhydrophobic/superhydrophilic surfaces to their surface chemistry. Langmuir 2010, 26, 8147–8154. [CrossRef]

- Passerone, A.; Valenza, F.; Muolo, M.L. A review of transition metals diborides: from wettability studies to joining. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 47, 8275–8289. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.W.; Kuo, C.P. Evaluation of surface roughness in laser-assisted machining of aluminum oxide ceramics with Taguchi method. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2007, 47, 141–147. [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Guan, K.; Lu, L.; Zhang, J.; Lu, N.; Guan, Y. Engineered functional surfaces by laser microprocessing for biomedical applications. Engineering 2018, 4, 822–830. [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllidis, D.; Li, L.; Stott, F.H. The effects of laser-induced modification of surface roughness of Al₂O₃-based ceramics on fluid contact angle. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 390, 271–277. [CrossRef]

- Kunz, C.; Bartolome, J.F.; Gnecco, E.; Muller, F.A.; Graf, S. Selective generation of laser-induced periodic surface structures on Al₂O₃-ZrO₂-Nb composites. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 434, 582–587. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Wang, Z.; He, W.; Guan, Y. Fabrication of superhydrophilic surface on alumina ceramic by ultrafast laser microprocessing. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 557, 149842. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guan, Y. Super Hydrophilic Surface Fabricated on Alumina Ceramic by Ultrafast Laser Microprocessing. J. Laser Micro/Nanoeng. 2021, 16, 237–241.

- CoorsTek. Al₂O₃ Thick-Film Ceramic Substrates Design Guide. Available online: https://www.coorstek.com (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Liu, J.M. Simple technique for measurements of pulsed Gaussian-beam spot sizes. Opt. Lett. 1982, 7, 196–198. [CrossRef]

- Andriukaitis, D. Examining Ablation Efficiency in Alumina Ceramics Utilizing Femtosecond Laser with MHz/GHz Burst Regime. Ph.D. Thesis, Vilniaus Universitetas, Vilnius, Lithuania, 2024.

- Di Niso, F.; Gaudiuso, C.; Sibillano, T.; Mezzapesa, F. P.; Ancona, A.; Lugarà, P. M. Role of heat accumulation on the incubation effect in multi-shot laser ablation of stainless steel at high repetition rates. Opt. express, 2014, 22, 12200-12210 . [CrossRef]

- Sfregola, F.A.; De Palo, R.; Gaudiuso, C.; Mezzapesa, F.P.; Patimisco, P.; Ancona, A.; Volpe, A. Influence of working parameters on multi-shot femtosecond laser surface ablation of lithium niobate. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 177, 111067. [CrossRef]

- De Palo, R.; Volpe, A.; Gaudiuso, C.; Patimisco, P.; Spagnolo, V.; Ancona, A. Threshold fluence and incubation during multi-pulse ultrafast laser ablation of quartz. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 44908–44917 . [CrossRef]

- Volpe, A.; Covella, S.; Gaudiuso, C.; Ancona, A. Improving the laser texture strategy to get superhydrophobic aluminum alloy surfaces. Coatings 2021, 11, 369. [CrossRef]

- Gaudiuso, C.; Fanelli, F.; Volpe, A.; Ancona, A.; Buogo, S.; Mezzapesa, F.P. Unlocking Ultrasound Manipulation by Laser-Engineered Hierarchical Nanostructures. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2025, submitted.

- Ngo, C.V.; Chun, D.M. Fast wettability transition from hydrophilic to superhydrophobic laser-textured stainless steel surfaces under low-temperature annealing. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 409, 232–240. [CrossRef]

- Mezzapesa, F.P.; Gaudiuso, C.; Volpe, A.; Ancona, A.; Mauro, S.; Buogo, S. Underwater acoustic camouflage by wettability transition on laser textured superhydrophobic metasurfaces. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 11, 2400124. [CrossRef]

- Lang, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, M.; Sun, X. Femtosecond laser patterned alumina ceramics surface towards enhanced superhydrophobic performance. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 15426–15434.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).