Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

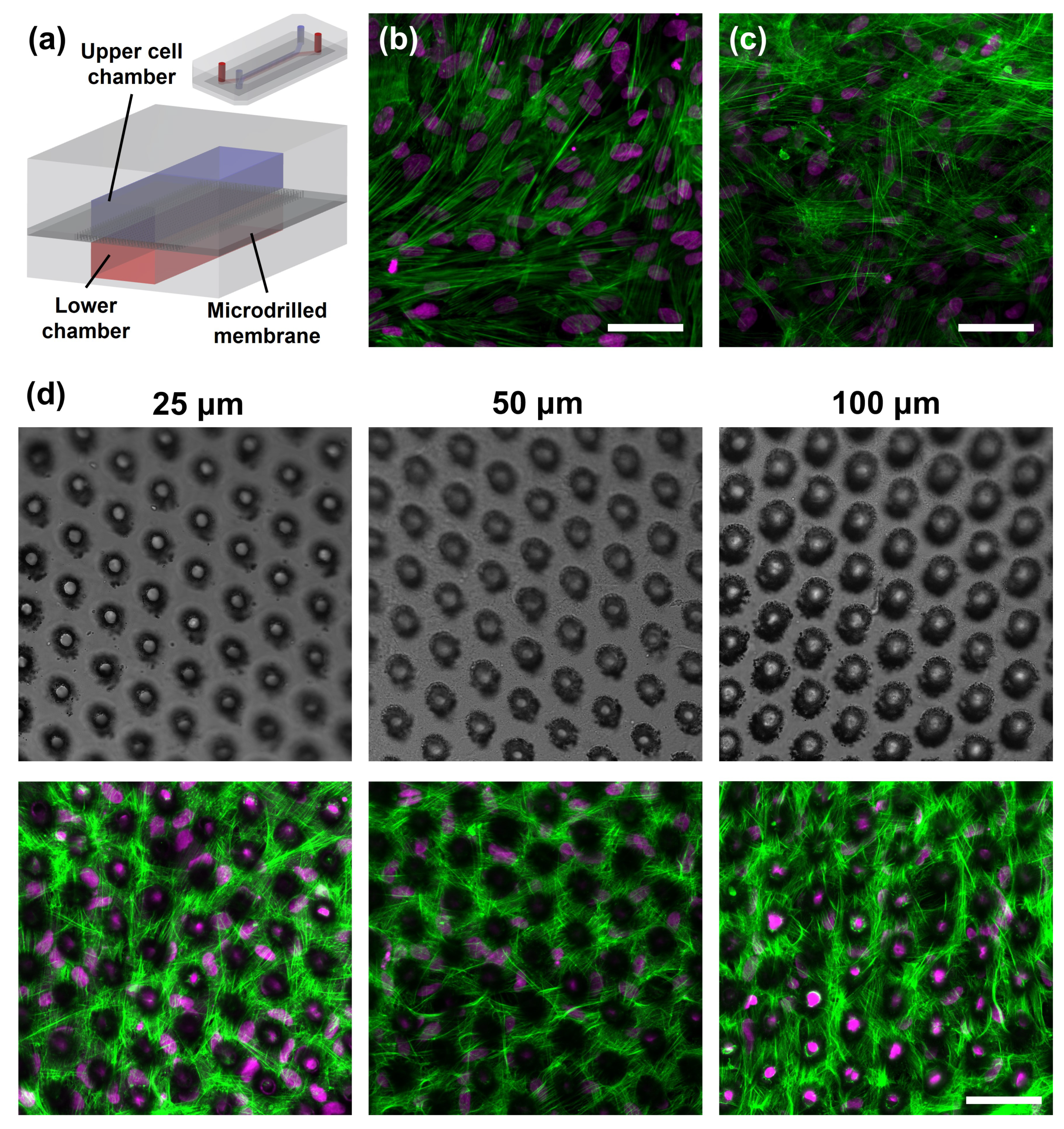

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. PDMS Membrane Preparation

2.3. Manufacturing of Microholes on PDMS Membrane Using FLM

2.4. Direct Optical Microscopy

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy Imaging

2.6. Determination of the Taper Angle of Holes

2.7. Mathematical Modeling of the PDMS Ablation Process

2.8. Cleaning and Assembling of OoC with Microdrilled PDMS Membranes

2.9. Cell Culture

2.10. Cell Staining

2.11. Inverted Optical and Confocal Microscopy

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Exploration of the Capabilities of FLM for Drilling PDMS Membranes

3.1.1. Effect of Drilling Time and Pulse Energy on Microholes Dimensions Using FLM

3.1.2. Influence of the Main Process Parameters on Picrohole Quality

3.2. Numerical Simulation of Femtosecond Laser Pulse and PDMS Interaction

3.2.1. Temporal Evolution of the Electron Density for a Single Laser Pulse

3.2.2. Effect of Pulse Energy on the Electron Density

3.2.3. Simulation of Material Removal by Laser Ablation

3.3. Scalability of the FLM for Large PDMS Membranes

3.4. Effectiveness of Debris Removal from Processed Membranes

3.5. In vitro Experimental Validation of the Assembled Membranes

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OoC | Organ-on-a-chip |

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| MEMS | Microelectromechanical systems |

| FLM | Femtosecond laser micromachining |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| RT | Room temperature |

| CPA | Chirped Pulse Amplification |

| CCD | Charge-coupled device |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| Coefficients of determination | |

| HAZ | Heat-affected zone |

Appendix A. Results of the linear regression analyses of the experimental data

| Thickness | Exposure time | Diameter | Equation | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 600 | Upper | 0.9741 | |

| Lower | 0.9650 | |||

| 1000 | Upper | 0.9605 | ||

| Lower | 0.9789 | |||

| 1400 | Upper | 0.9526 | ||

| Lower | 0.9714 | |||

| 50 | 600 | Upper | 0.9861 | |

| Lower | 0.9835 | |||

| 1000 | Upper | 0.8864 | ||

| Lower | 0.9659 | |||

| 1400 | Upper | 0.9409 | ||

| Lower | 0.9353 | |||

| 100 | 600 | Upper | 0.9677 | |

| Lower | 0.9953 | |||

| 1000 | Upper | 0.9593 | ||

| Lower | 0.9239 | |||

| 1400 | Upper | 0.9850 | ||

| Lower | 0.9334 |

| Thickness | Pulse Energy | Diameter | Equation | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 4 | Upper | 0.9714 | |

| Lower | 0.9278 | |||

| 10 | Upper | 0.9616 | ||

| Lower | 0.9641 | |||

| 16 | Upper | 0.9857 | ||

| Lower | 0.9233 | |||

| 50 | 4 | Upper | 0.8520 | |

| Lower | 0.9335 | |||

| 10 | Upper | 0.7831 | ||

| Lower | 0.8031 | |||

| 16 | Upper | 0.9447 | ||

| Lower | 0.4810 | |||

| 100 | 4 | Upper | 0.5122 | |

| Lower | 0.9550 | |||

| 10 | Upper | 0.8748 | ||

| Lower | 0.9559 | |||

| 16 | Upper | 0.8912 | ||

| Lower | 0.8792 |

Appendix B. Additional Simulation for 12 μJ pulse energy

References

- Tajeddin, A.; Mustafaoglu, N. Design and Fabrication of Organ-on-Chips: Promises and Challenges. Micromachines 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.H.; Esch, M.B.; Prot, J.M.; Long, C.J.; Smith, A.; Hickman, J.J.; Shuler, M.L. Microfabricated mammalian organ systems and their integration into models of whole animals and humans. Lab Chip 2013, 13, 1201–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huh, D.; Kim, H.J.; Fraser, J.P.; Shea, D.E.; Khan, M.; Bahinski, A.; Hamilton, G.A.; Ingber, D.E. Microfabrication of human organs-on-chips. Nature Protocols 2013, 8, 2135–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosadegh, B.; Agarwal, M.; Torisawa, Y.s.; Takayama, S. Simultaneous fabrication of PDMS through-holes for three-dimensional microfluidic applications. Lab Chip 2010, 10, 1983–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, D.; Matthews, B.D.; Mammoto, A.; Montoya-Zavala, M.; Hsin, H.Y.; Ingber, D.E. Reconstituting Organ-Level Lung Functions on a Chip. Science 2010, 328, 1662–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirós-Solano, W.F.; Gaio, N.; Stassen, O.M.J.A.; Arik, Y.B.; Silvestri, C.; Van Engeland, N.C.A.; Van der Meer, A.; Passier, R.; Sahlgren, C.M.; Bouten, C.V.C.; et al. Microfabricated tuneable and transferable porous PDMS membranes for Organs-on-Chips. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 13524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, A.; Fleischman, A.J.; Roy, S. Characterization of Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Properties for Biomedical Micro/Nanosystems. Biomedical Microdevices 2005, 7, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, B.K.; Jafek, A.R.; Lambert, C.J.; Goenner, B.L.; Moghimifam, H.; Nze, U.C.; Kamarapu, S.K. A Review of Current Methods in Microfluidic Device Fabrication and Future Commercialization Prospects. Inventions 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Xia, Y.; Whitesides, G.M. Soft lithography for micro- and nanoscale patterning. Nature Protocols 2010, 5, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.J.; Oh, D.J.; Jung, P.G.; Lee, S.M.; Go, J.S.; Kim, J.H.; Hwang, K.Y.; Ko, J.S. Dry etching of polydimethylsiloxane using microwave plasma. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 2009, 19, 095010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yao, Z.; Hou, Z.; Song, J. Processing and Profile Control of Microhole Array for PDMS Mask with Femtosecond Laser. Micromachines 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feit, M.; Komashko, A.; Rubenchik, A. Ultra-short pulse laser interaction with transparent dielectrics. Applied Physics A 2004, 79, 1657–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, B.C.; Feit, M.D.; Herman, S.; Rubenchik, A.M.; Shore, B.W.; Perry, M.D. Nanosecond-to-femtosecond laser-induced breakdown in dielectrics. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 53, 1749–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Du, D.; Mourou, G. Laser ablation and micromachining with ultrashort laser pulses. IEEE Journal of Quantum Electronics 1997, 33, 1706–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobyev, A.Y.; Guo, C. Direct femtosecond laser surface nano/microstructuring and its applications. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2013, 7, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaser, A.S.; Khan, S.A.; Ganeev, R.A.; Stratakis, E. Recent Advances in Femtosecond Laser-Induced Surface Structuring for Oil–Water Separation. Applied Sciences 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Guo, Z. Ultra-short pulsed laser PDMS thin-layer separation and micro-fabrication. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 2009, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishi, S.; Cubaud, T.; Longtin, J.P. Ultrafast laser machining of tapered microchannels in glass and PDMS. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 2012, 50, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.K.; Chen, S.C.; Huang, W.L.; Hsu, K.P.; Gorday, K.A.V.; Wang, T.; Wang, J. Direct Micromachining of Microfluidic Channels on Biodegradable Materials Using Laser Ablation. Polymers 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshehri, A.M.; Hadjiantoniou, S.; Hickey, R.J.; Al-Rekabi, Z.; Harden, J.L.; Pelling, A.E.; Bhardwaj, V.R. Selective cell adhesion on femtosecond laser-microstructured polydimethylsiloxane. Biomedical Materials 2016, 11, 015014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torino, S.; Conte, L.; Iodice, M.; Coppola, G.; Prien, R.D. PDMS membranes as sensing element in optical sensors for gas detection in water. Sensing and Bio-Sensing Research 2017, 16, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keldysh, L. Ionization in field of a strong electromagnetic wave. Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Physics 1965, 20, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkayar, G.; Lötters, J.C.; Tichem, M.; Ghatkesar, M.K. Toward a modular, integrated, miniaturized, and portable microfluidic flow control architecture for organs-on-chips applications. Biomicrofluidics 2022, 16, 021302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo-Lucea, C.; Bellver, C.; Gandia, C.; Sanz-Garcia, A.; Esteban, F.J.; Mirabet, V.; Forte, G.; Moreno, I.; Lezameta, M.; Ayuso-Sacido, A.; et al. A Xenogeneic-Free Protocol for Isolation and Expansion of Human Adipose Stem Cells for Clinical Uses. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudiuso, C.; Giannuzzi, G.; Volpe, A.; Lugarà, P.M.; Choquet, I.; Ancona, A. Incubation during laser ablation with bursts of femtosecond pulses with picosecond delays. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 3801–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, M.; Tam, A.C. On the saturation effect in the picosecond near ultraviolet laser ablation of polyimide. Journal of Applied Physics 1989, 65, 2591–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Perrie, W.; Edwardson, S.; Fearon, E.; Dearden, G.; Watkins, K. Effects of laser operating parameters on metals micromachining with ultrafast lasers. Applied Surface Science 2009, 256, 1514–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudach, S.; Bonse, J.; Kautek, W. Ablation experiments on polyimide with femtosecond laser pulses. Applied Physics A 1999, 69, S395–S398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Li, M.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; He, M.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S. Numerical simulation and investigation of ultra-short pulse laser ablation on Ti6Al4V and stainless steel. AIP Advances 2023, 13, 065018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, D.; Hagenlocher, C.; Weber, R.; Röcker, C.; Abdou Ahmed, M.; Graf, T. Model for designing process strategies in ultrafast laser micromachining at high average powers. Materials & Design 2024, 242, 113007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Collision factor, 1 | 1/s | |

| Bandgap of PDMS, | 4.2 | eV |

| Free electron energy, | 0.5 | eV |

| Refractive index of PDMS, | 1.4235 | - |

| Relative permittivity of PDMS, | - | |

| Critical electron density, | 1/m3 | |

| Recombination coefficient, 1 | cm3/s | |

| 1 Reference values for water. |

| Parameter | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Laser wavelength, | 800 | |

| Pulse duration, | 60 | |

| Repetition rate, f | 5 | |

| Laser spot diameter, | 7 | |

| Thickness of PDMS membranes, | 25, 50, 100 | |

| Exposure time, | 800, 1000, 1200, 1400, 1600, 1800 | |

| Pulse energy, | 4, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20 |

| Thickness | Entrance Diameter | Exit Diameter | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Model | Experimental | Model | |||

| 25 | 14.02 ± 0.15 | 14.15 | 0.93% | 10.83 ± 0.09 | 11.24 | 3.79% |

| 50 | 12.41 ± 0.12 | 14.53 | 17.08% | 10.44 ± 0.10 | 9.77 | 6.42% |

| 100 | 12.28 ± 0.22 | 14.39 | 17.18% | 9.25 ± 0.07 | 9.35 | 1.08% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).