1. Introduction

Natural products continue to serve as invaluable sources of bioactive compounds and functional materials, with melanins representing one of the most ubiquitous and structurally complex biopolymers found in nature [

1]. These dark pigments, distributed across diverse biological kingdoms from bacteria to mammals, exhibit remarkable physicochemical properties that have attracted increasing attention for biotechnological and industrial applications [

2,

3]. The growing interest in sustainable alternatives to synthetic materials has positioned natural melanins as promising candidates for advanced applications, particularly in emerging optoelectronic technologies where their unique combination of optical, electronic, and chemical properties offers distinct advantages [

3,

4].

Melanins constitute a heterogeneous family of high-molecular-weight pigments derived from the oxidative polymerization of phenolic and indole compounds [

5,

6]. Among the various melanin types, eumelanin stands out for its superior stability, biocompatibility, and functional properties, making it particularly attractive for technological applications [

7,

8]. The complex structure of eumelanin, composed of 5,6-dihydroxyindole (DHI) and 5,6-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid (DHICA) units, forms an extended conjugated system responsible for its characteristic broadband UV-visible absorption and electronic properties [

9,

10].

Recent advances in natural product chemistry have revealed the remarkable potential of melanins in optoelectronic applications, where their unique properties enable novel functionalities not achievable with conventional synthetic materials [

11,

12]. The ability of melanins to exhibit mixed electronic-ionic conductivity, hydration state-dependent electrical properties, and broad-spectrum UV absorption has opened new avenues for applications in solar energy conversion, optical materials, and electronic devices [

3,

13]. These discoveries have transformed melanins from simple pigments to sophisticated functional materials with demonstrated utility in cutting-edge technologies [

14,

15].

The traditional sources of melanin, including cuttlefish ink and mammalian tissues, present limitations in terms of sustainability, scalability, and consistency [

16,

17]. Plant-derived melanins offer compelling advantages, including renewable feedstock, reduced environmental impact, and potentially unique chemical compositions that may enhance functionality [

18,

19]. Among plant sources, seeds of the genus

Mucuna have emerged as up-and-coming candidates due to their exceptionally high L-DOPA content, the primary precursor for melanin biosynthesis, and their demonstrated bioactive properties, including antioxidant and neuroprotective effects [

20,

21].

Mucuna ceniza, a leguminous plant native to tropical regions of Mexico, represents an outstanding source for sustainable melanin production when cultivated under controlled organic conditions [

22,

23]. A recent comprehensive characterization of

M. ceniza seed extracts has revealed L-DOPA concentrations of up to 56% by weight in properly prepared extracts, representing one of the highest concentrations achievable through sustainable extraction methods [

24]. The standardized cultivation in Tepecoacuilco, Guerrero, Mexico, under organic conditions without chemicals or pesticides, ensures consistent quality and environmental sustainability while providing the high-quality precursor material essential for melanin biotransformation.

The bioactive properties of

Mucuna species extend beyond their utility as L-DOPA sources, with recent studies demonstrating significant antioxidant, neuroprotective, and anti-inflammatory properties [

25,

26]. These properties are particularly relevant for melanin production, as they suggest that the natural extracts may contribute additional functional characteristics to the final melanin product [

27]. The demonstrated ability of

M. pruriens extracts to prevent depression-like behaviours and reduce oxidative stress through mechanisms involving decreased lipid peroxidation and increased glutathione concentrations provides valuable insights into the antioxidant mechanisms that may be preserved in the melanin derived from these sources [

28,

29].

The development of standardized extraction protocols using green chemistry approaches has enabled the production of high-quality L-DOPA extracts suitable for biotechnological applications [

30]. The use of acetic and citric acids as extraction solvents, combined with lyophilization for product stabilization, offers a sustainable alternative to harsh chemical extraction methods while preserving the integrity of the L-DOPA precursor and its associated bioactive compounds. This approach aligns with current trends toward environmentally responsible natural product processing, ensuring the preservation of functional properties essential for advanced applications [

31].

The biotechnological production of melanin from standardized plant extracts involves the controlled oxidative polymerization of L-DOPA under optimized conditions that preserve the structural integrity and functional properties essential for advanced applications [

32]. This process can be systematically optimized through careful manipulation of pH, temperature, aeration, and agitation parameters in stirred-tank bioreactor systems [

33].

Comprehensive analytical characterization plays a crucial role in natural product chemistry, particularly for complex biopolymers like melanin, where structure-property relationships determine functional performance [

34]. State-of-the-art spectroscopic methods, including UV-visible, FTIR, and Raman spectroscopy, provide detailed insights into molecular structure, functional groups, and electronic properties [

2,

35]. These analytical approaches, combined with elemental analysis and chemical characterization, enable definitive identification and quality assessment of natural melanins while ensuring reproducibility and standardization.

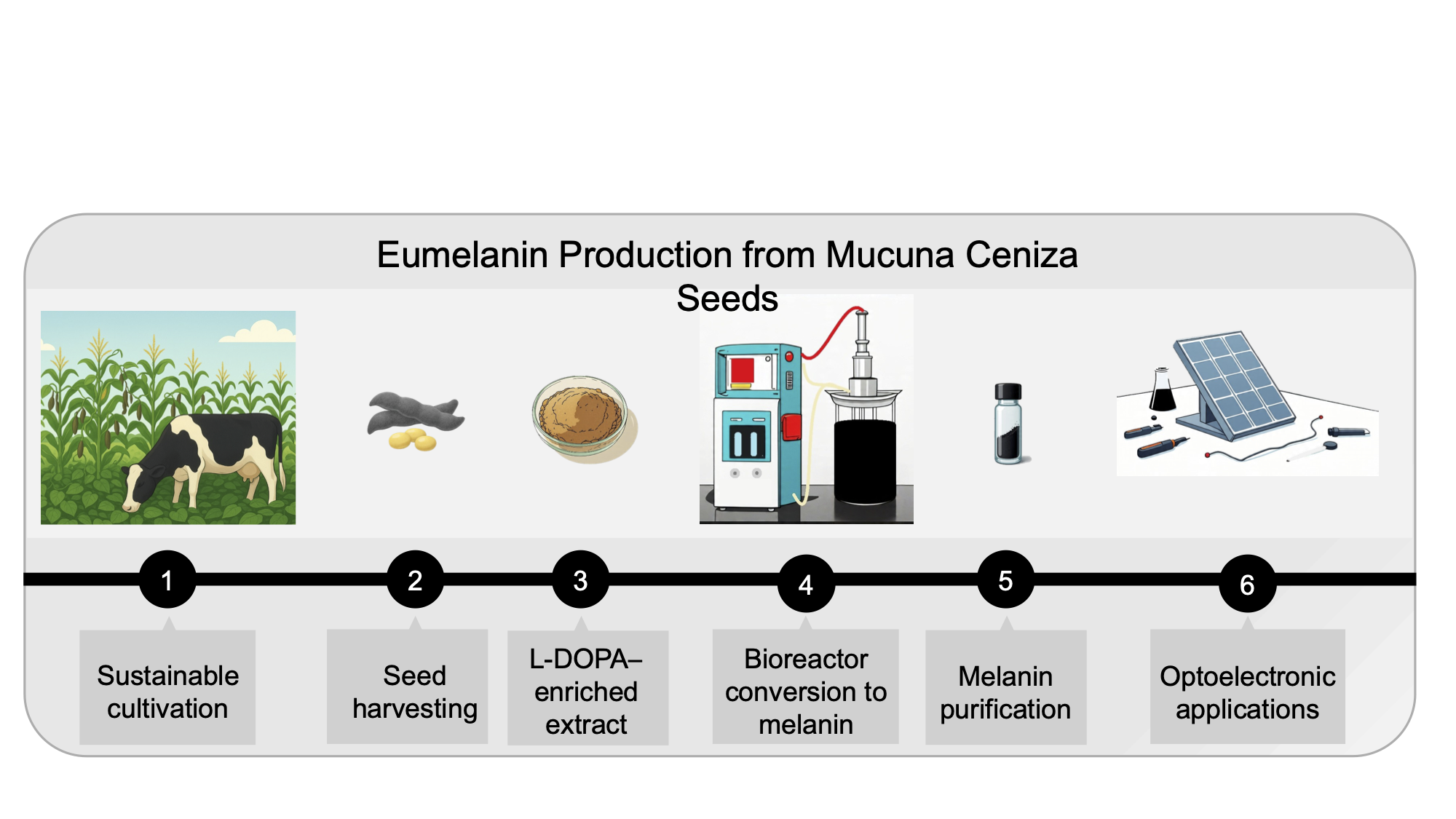

The present study addresses the critical need for comprehensive analytical characterization of melanin produced from standardized M. ceniza seed extracts through systematic application of state-of-the-art analytical methods. Our objectives include utilization of standardized, organically cultivated M. ceniza seeds and high-quality L-DOPA extracts as starting materials, optimization of biotechnological melanin production using stirred-tank bioreactor technology, comprehensive spectroscopic characterization using UV-Vis, FTIR, Raman, NMR spectroscopy, and elemental analysis for definitive melanin identification and classification, and evaluation of properties relevant to demonstrated optoelectronic applications.

This work makes a significant contribution to the field of natural product chemistry by providing the first detailed analytical characterization of melanin from standardized M. ceniza seed extracts, establishing reproducible methods for quality assessment, and demonstrating the potential for sustainable biotechnological production of high-value functional materials.

2. Results

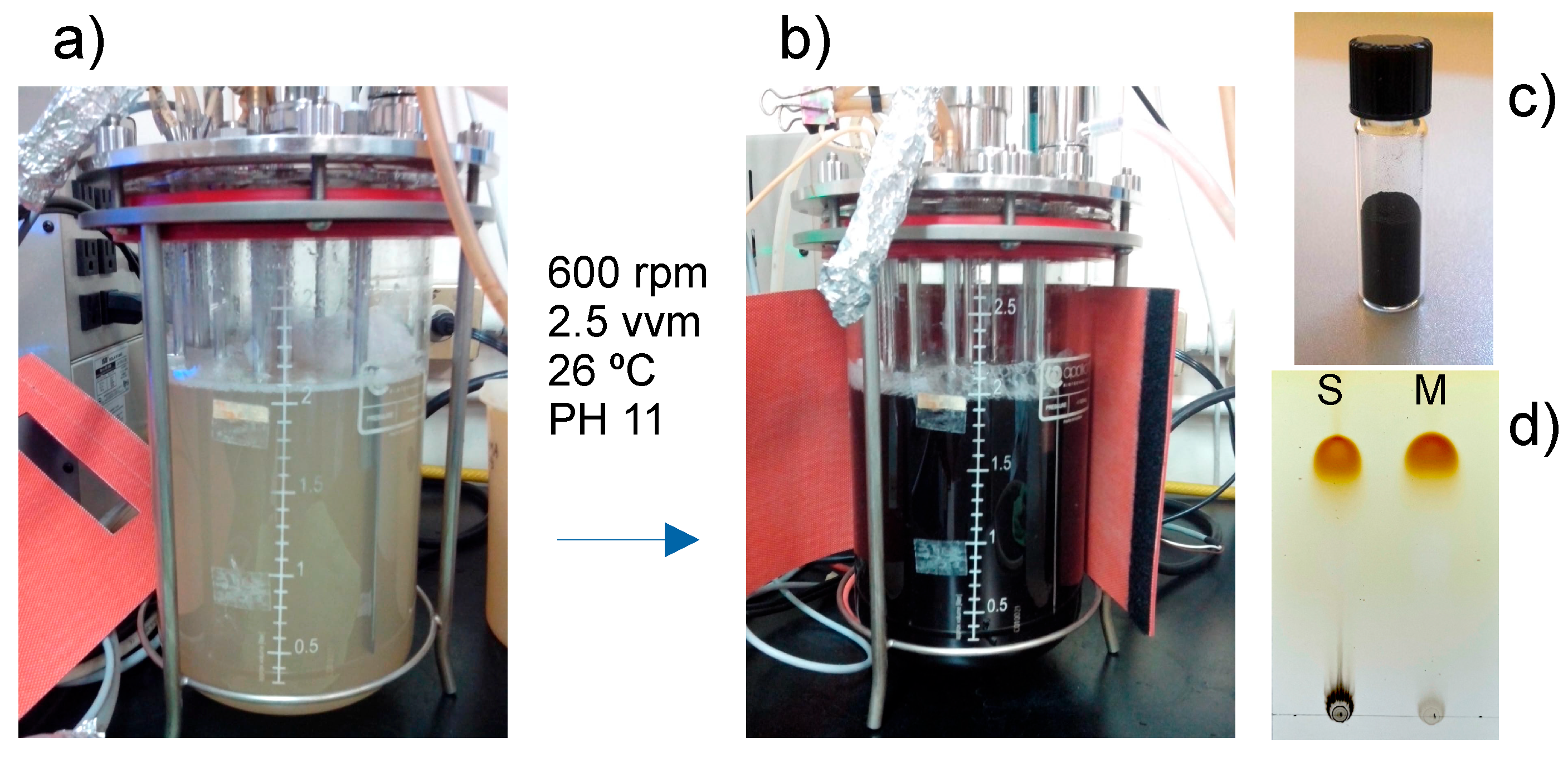

2.1. Standardized Melanin Preparation

The standardized L-DOPA extract obtained from organically cultivated

M. ceniza seeds demonstrated quality and consistency, with L-DOPA content of 56 ± 2% (w/w) maintained across multiple extraction batches [

24]. This remarkable concentration represents one of the highest L-DOPA yields achieved through sustainable extraction methods and compares favourably with synthetic L-DOPA preparations. For vegetal melanin obtention, the process optimization using this standardized extract achieved remarkable melanin production rates of 1526.23 ± 10.78 mg L⁻¹ h⁻¹ under optimal conditions (pH 11, 600 rpm agitation, 2.5 vvm aeration, 26 °C), representing the highest melanin production rates ever reported for plant-derived systems [

36,

37,

38]. TLC followed the conversion from L-DOPA to melanin with the absence of the band corresponding to L-DOPA when conversion was complete.

The optimization process involved a systematic evaluation of critical parameters affecting melanin formation from the complex plant extract matrix. As a proof of concept, it was initiated with the conversion of 100 mg of commercial L-DOPA (Sigma Co.) to melanin in a bioreactor (not show). The temperature at 26 °C was found to be optimal for maintaining melanin conversion while preventing the thermal degradation of sensitive bioactive compounds present in the plant extract [

39]. The alkaline pH conditions (pH 11) facilitated the oxidative polymerization of L-DOPA while maintaining the stability of the bioreactor system and ensuring complete substrate conversion (

Figure 1).

2.2. Elemental Analysis of Mucuna Ceniza Melanin

The results of elemental analysis of

Mucuna melanin powder show the typical pattern of other vegetal eumelanins [

2,

40]. With the C/N relationship (~4.05) and the nitrogen content of (11.85%) as typical of melanins with some protein content (

Table 1).

The difference with theoretical values suggests a significant incorporation of amino acids (N), amine and hydroxyl groups, and a more complex structure related to the theoretical melanin model. The resultant empirical formulae can be approached to C₄₈H₇₄N₁₀O₂₅S₀.₀₁. The few contents of S in the sample may indicate that it is eumelanin, unlike pheomelanins, which generally have more sulfur content [

41].

2.3. Spectroscopic Characterization and Structural Authentication

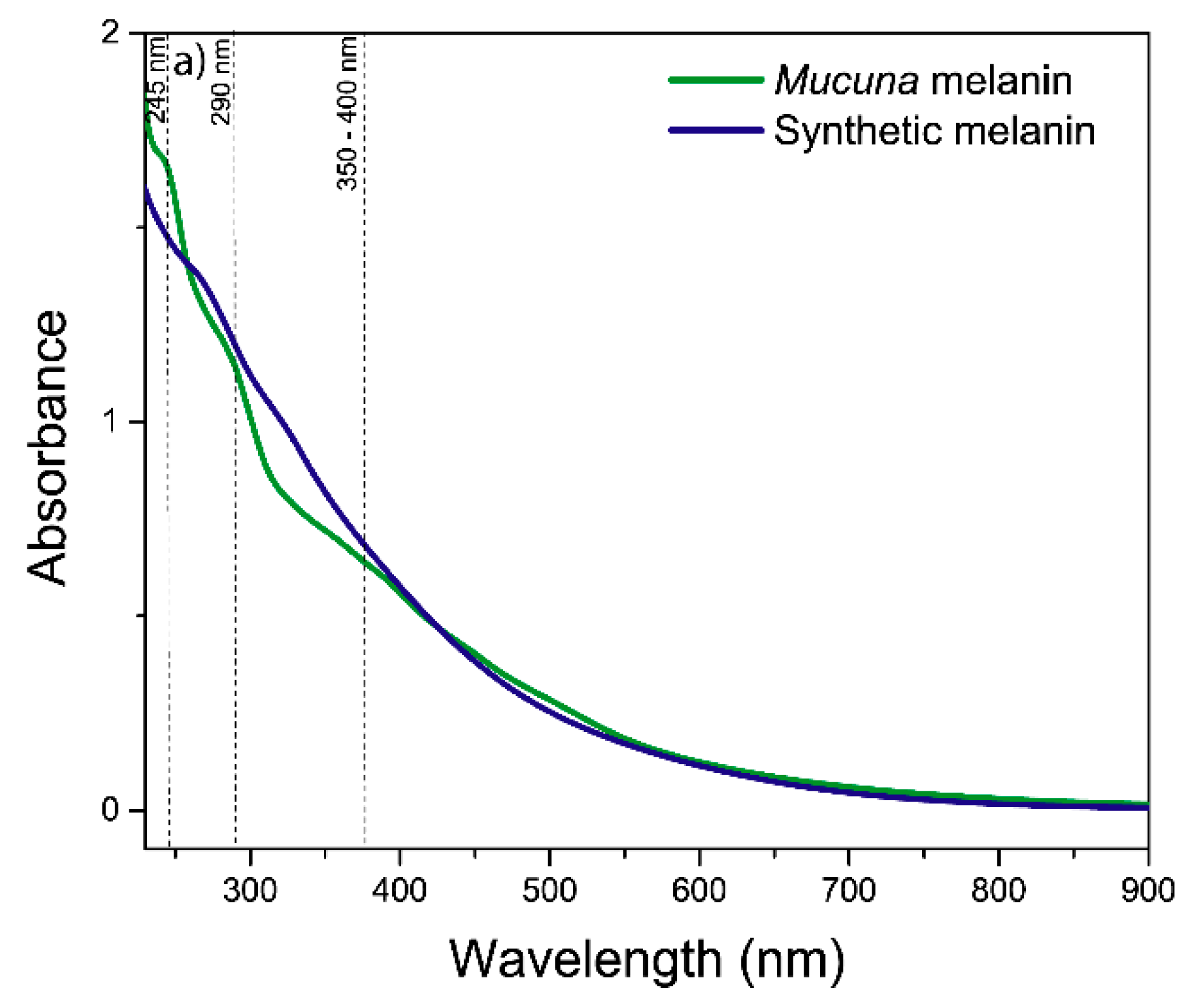

2.3.1. UV-Visible Absorption Spectrum

UV-visible spectroscopic analysis confirmed the identity of melanin and revealed characteristic absorption properties consistent with the authentic eumelanin structure [

42]. The absorption spectrum exhibited the characteristic monotonic decrease in absorbance with increasing wavelength and a linear correlation between the logarithm of the absorbance and wavelength for

Mucuna and synthetic melanin (

Figure S1), a diagnostic feature that distinguishes melanin from other natural pigments [

43]. The maximum peak absorption at 225-290 nm may correspond to the protein content of biological melanins, and the general pattern is characteristic of an amorphous and geometrically disordered polymeric biomaterial, such as eumelanin from diverse sources [

44,

45].

Figure 2.

UV-visible spectrum analysis of melanins.

Figure 2.

UV-visible spectrum analysis of melanins.

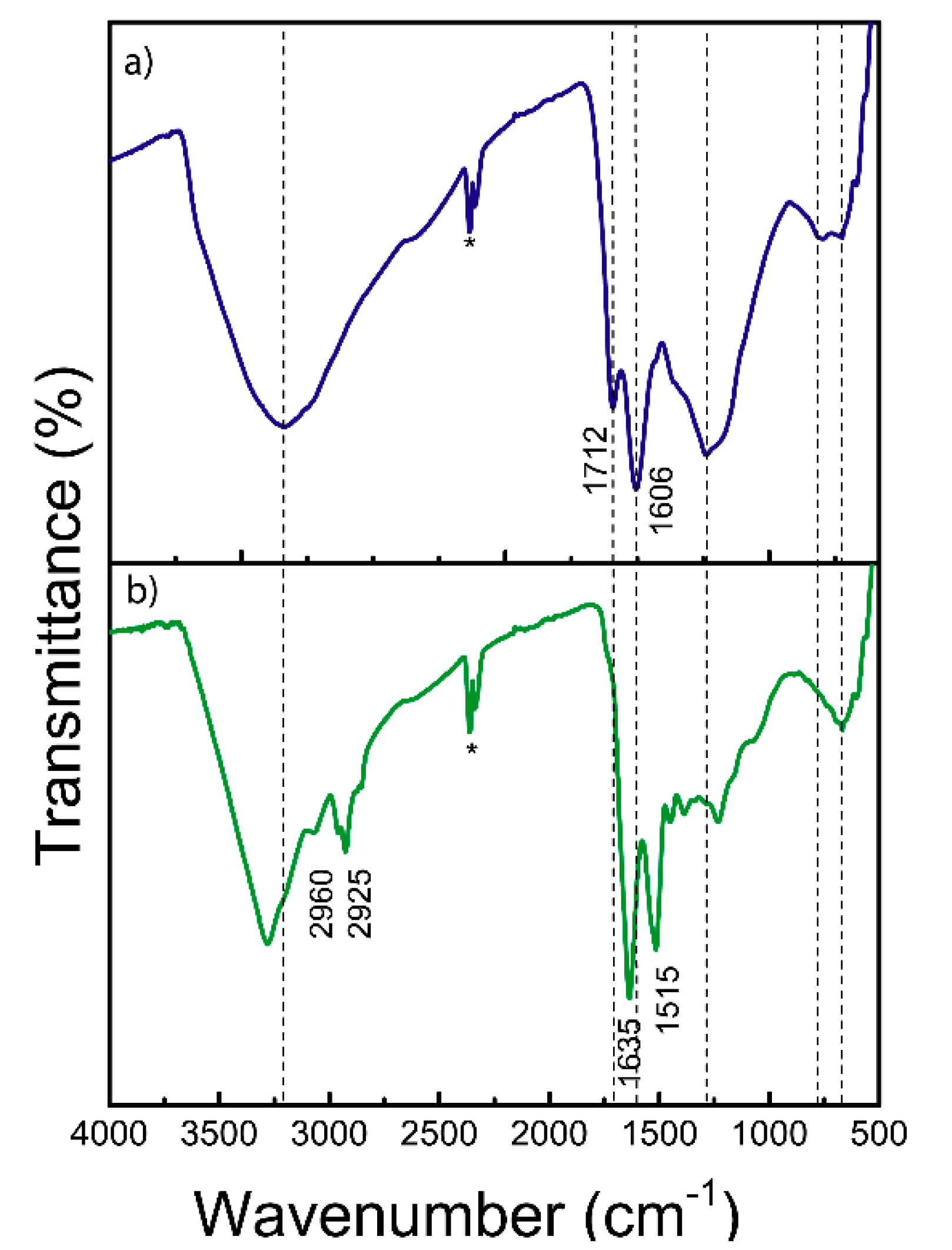

2.3.2. FTIR Spectroscopy Analysis

The FTIR spectroscopy shows molecular vibrations when infrared radiation interacts with chemical bonds. In melanins, these vibrations correspond mainly to aromatic, carbonylic, and hydroxylic functional groups [

41]. Melanins show a relatively complex pattern due to their heterogeneous composition. In the broad region ~3400-3200 cm⁻¹ is the characteristic -OH and N-H stretches of phenolic, carboxylic, and aromatic amino acids (

Figure 3). The absorption bands at 2960 and 2925 cm⁻¹ are attributed to aliphatic C–H stretching vibration [

46]. A prominent band at 1635 cm⁻¹ corresponds to C=C stretching within the indole ring, while the features at 1515 and 1454 cm⁻¹ are associated with C–H deformation and coupled vibrational modes [

47]. The broad region spanning 1000–1300 cm⁻¹ can be ascribed to C–N stretching vibrations of the indole moiety [

47]. Signals below 1000 cm⁻¹ indicate the presence of aromatic ring structures, potentially with substitution patterns. Additionally, the aliphatic C–C stretching observed at 1453 cm⁻¹ may reflect the presence of protein residues closely associated with the melanin matrix [

48]. It is observed that the absence of a peak between 700–600 cm

-1 (

Figure S2), typical of sulphur groups in pheomelanins [

49], indicates again that this is probably eumelanin. Finally, the differences between the two spectra are attributed to the different chemical environments around the functional groups.

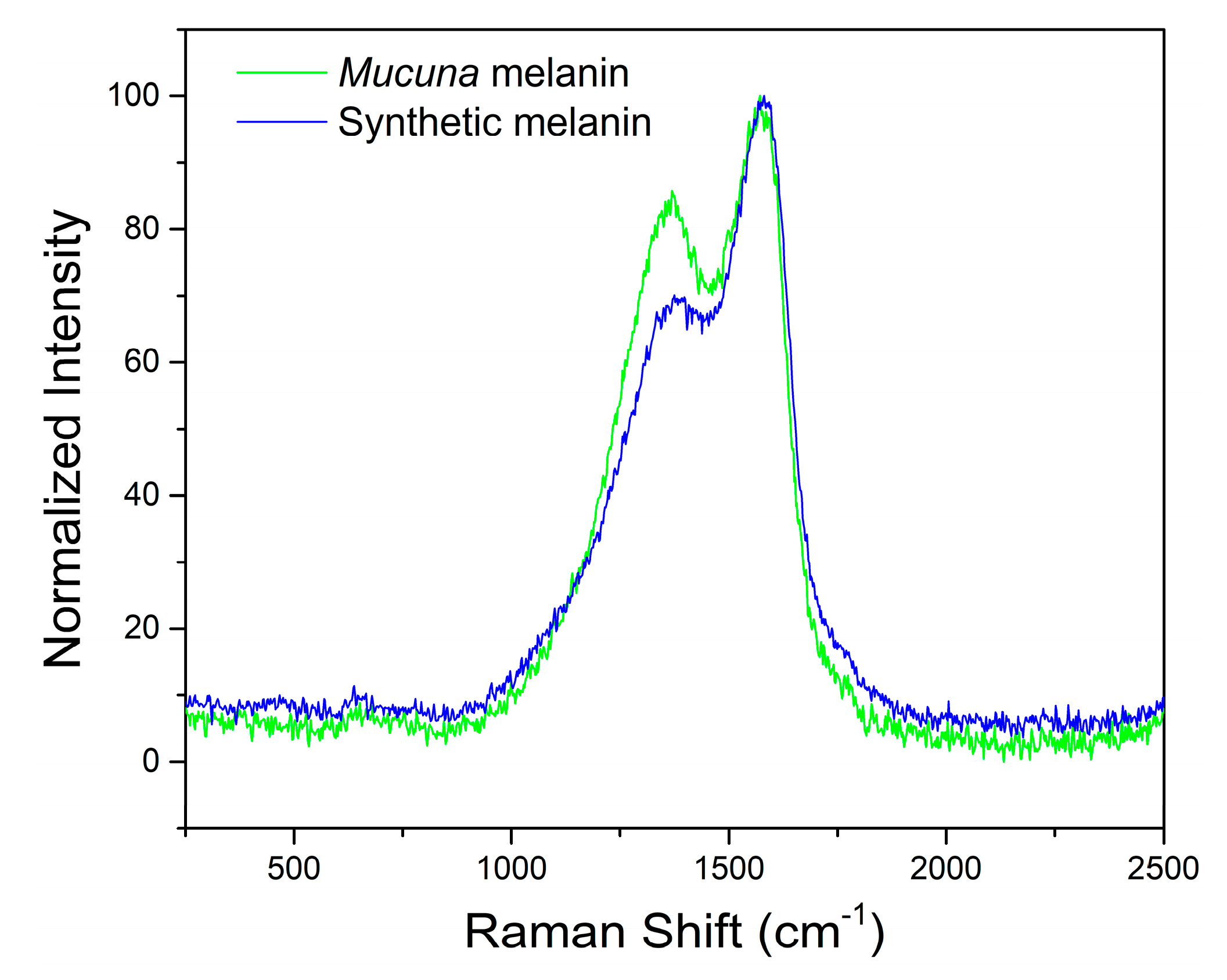

2.3.3. Raman Spectroscopy

The Raman spectroscopy is based on the phenomenon of inelastic dispersion of monochromatic light (laser) when it interacts with vibrational molecular modes, particularly in conjugated aromatic rings, such as those that form the polymeric structure of melanins. This technique provided complementary structural information to FTIR. It confirmed the eumelanin identity through characteristic vibrational bands at 1380 and 1580 cm⁻¹ (

Figure 4). The prominent peak in synthetic melanin at 1580 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the aromatic rings’ breathing modes and C=C stretching vibrations, characteristic of the indole-based polymer backbone typical of eumelanin structures [

50]. The 1380 cm⁻¹ peak in eumelanin Raman spectra originates from linear stretching of C-C bonds within aromatic rings, with contributions from C-H vibrations in methyl and methylene groups [

51].

In the

Mucuna melanin, a more prominent peak at 1380 cm

-1 is observed, which could indicate a more complex conjugated structure attributable to a different subunit composition compared with the synthetic one. The characteristic profile of the band within the 550–1200 cm⁻¹ region indicates a high abundance of DHI units. In contrast, the absence of significant spectral broadening in the 1650–2300 cm⁻¹ region suggests a high DHI:DHICA ratio in the

Mucuna melanin [

51]. This analysis confirms the identity as eumelanin when compared to other studies with natural melanins [

52,

53].

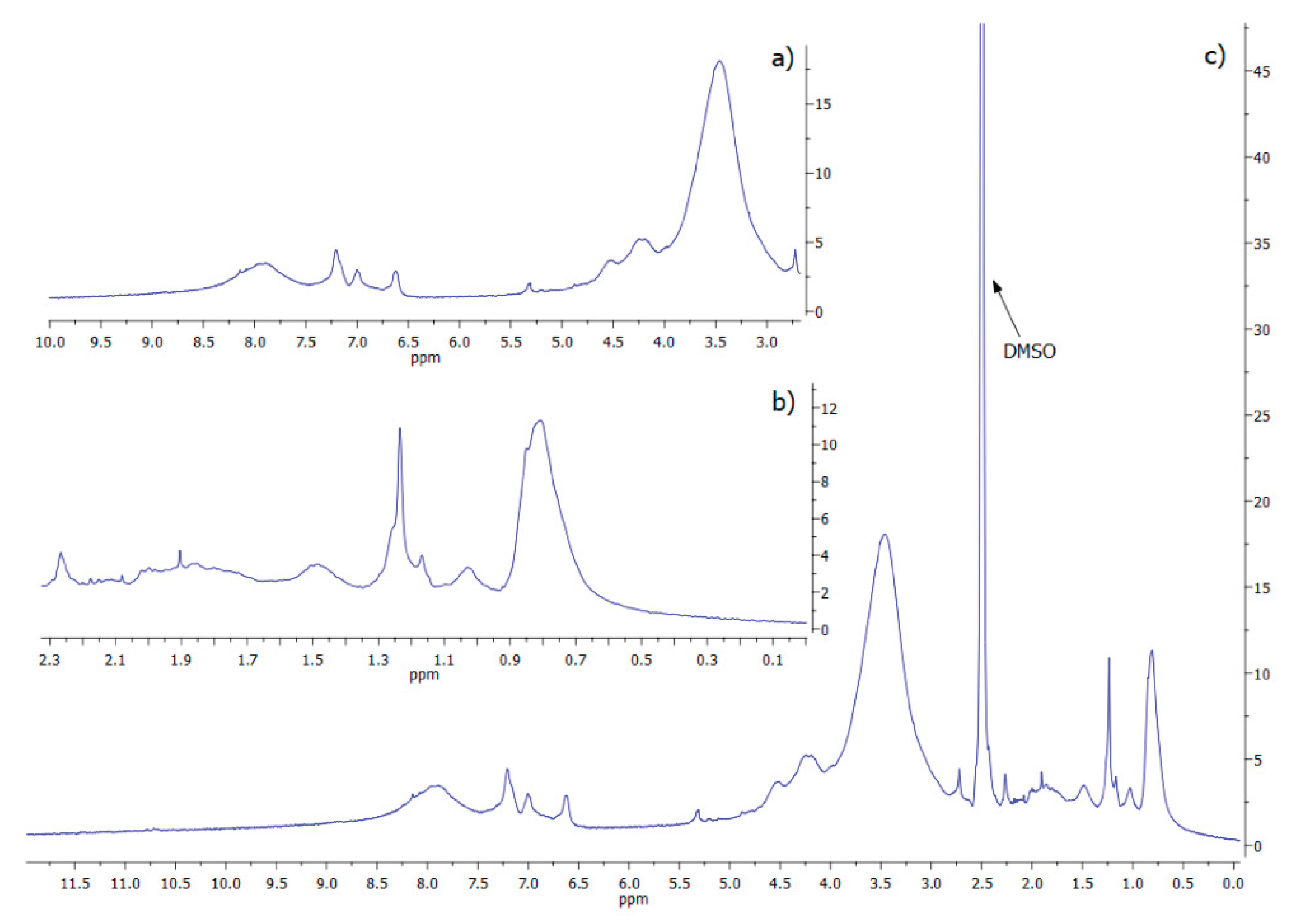

2.3.4. NMR Spectroscopy

The ¹H-NMR spectral chemical shift (δ) is represented as parts per million (ppm) to be comparable across different instruments. In

Figure 5, the ¹H-NMR spectrum of

Mucuna eumelanin is presented. Due to the chemical complexity of melanin’s structure and its supramolecular interactions, a spectrum with broad signals is obtained. The solvent residual peak (DMSO) is clearly present at 2.5 ppm, and for a better appreciation, the spectrum is divided into insets 5a and 5b, alongside the DMSO peak.

The broad resonance observed around 8.0 ppm was assigned to hydroxyl (–OH) groups attached to aromatic rings (

Figure 5a). Additionally, the signals appearing between 6.5 and 7.3 ppm were attributed to aromatic protons of indole and/or pyrrole moieties. The signals in the region of 4.5–5.4 ppm were consistent with vinylic protons (C=C–H) adjacent to nitrogen and/or oxygen atoms [

54]. Finally, the resonances detected between 3.2 and 4.2 ppm were ascribed to methylene or methyl groups bonded to heteroatoms such as nitrogen or oxygen (CH

2OH) [

40], which is consistent with hydroxylated side chains or partially oxidized aliphatic components within the eumelanin polymer matrix.

The presence of an NH-group linked to indole was attributed to the signals within the range of 1.3 – 2.3 ppm [

40]. Finally, the peaks visible in the aliphatic region (

Figure 5b) correspond to alkyl groups in eumelanins (0.5-2.5 ppm). The multiple peaks in this zone are likely contributed to by methylene bridges and the incorporation of lipids and fatty acids during eumelanin production, as well as residual proteins [

2]. No peaks corresponding to carboxylic acid protons (typically expected at 10–12 ppm) attributable to DHICA units were detected. Combined with Raman analysis, these results indicate that

Mucuna melanin is predominantly composed of DHI moieties. Interestingly, comparison of the

1H-NMR spectrum of

Mucuna melanin with

Catharsius molossus L. melanin shows remarkable similarities (

Figure S3), which indicates the same structure in the two types of melanin [

48].

Additionally, the liquid

13C-NMR spectrum displayed only a limited number of resonances (

Figure S4). The most intense signal appeared at 171 ppm, consistent with carbonyl carbons from peptide bonds, carboxyl or amide side-chain groups, and carbonyl functionalities associated with eumelanin quinones [

54].

3. Discussion

Melanin represents one of the most ubiquitous and functionally diverse biopolymers found across living organisms, from microorganisms to higher animals and plants. Their intense research is partly due to the search for new sources of materials with desired characteristics [

55]. The social trends demand sustainable ways of production [

56]. Therefore, the availability of biomaterials is relevant for future societies. Particularly, melanins have long been a promising biomaterial due to their optical and electronic properties [

57]. There are many reviews and proof of concepts in their applications [

58,

59,

60]; however, until now, there is no industry based on melanins due to their scarcity and prohibitively high cost [

16,

61].

Here, we show that it is possible to obtain melanin in a renewable way at a cost that could be competitive for industrial applications. The

Mucuna plants from which they are extracted, leguminous plants, provide multiple environmental benefits through their cultivation: contributing to soil recovery with their biomass [

62], enhancing soil nutrition by bacteria fixing and incorporating nitrogen in their roots [

63], and protecting small species with their abundant foliage. The plant is used as a cover crop and intercrop mainly with maize [

64].

The classification of melanins into five major types—eumelanin, pheomelanin, neuromelanin, allomelanin, and pyomelanin—provides a framework for understanding the chemical and functional diversity of these remarkable biopolymers [

65]. Each type exhibits unique structural features and properties that reflect its specific biosynthetic pathways and biological functions.

Eumelanins are described as present in animals and plants and represent the most abundant and well-studied form of melanin, characterized by its dark brown to black coloration. This heterogeneous polymer, composed primarily of 5,6-dihydroxyindole (DHI) and 5,6-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid (DHICA) units, is derived from the oxidative polymerization of dopaquinone. The relative proportion of DHI and DHICA subunits significantly influences the physicochemical properties of the resulting eumelanin polymer. This result makes sense since the melanin here produced is derived from an extract enriched in L-DOPA [

24].

Recent research has revealed that eumelanin exhibits a hierarchical organization, with oligomeric sheets forming proto-particles that subsequently aggregate into larger, anti-spherical particles. This structural organization contributes to eumelanin’s unique optical and electronic properties, making it an attractive material for bioelectronics applications [

66]. The polymer’s ability to conduct both electrons and ions, combined with its biocompatibility, has led to its investigation in organic electronics and biomedical devices [

67]. The elemental analysis and the more common spectroscopic analyses presented here confirm that the melanin extracted in this way from

Mucuna pruriens var. ceniza corresponds to authentic eumelanin.

There are numerous reports on the beneficial biological activity of

Mucuna pruriens, primarily the seeds [

68,

69,

70]. In particular, the L-DOPA-enriched extract from which melanin is obtained has been shown to prevent depression-like behaviors after a mild traumatic brain injury, with evidence of reducing oxidative stress and diminishing lipid peroxidation, and increasing reduced glutathione in specific brain areas [

29].

On the other hand, the melanin described here has already shown potential applications in optoelectronic technologies, validating the technological relevance of its comprehensive characterization and sustainable production approach. In one first study, melanin/PSi composites show their potential for increasing radiative recombination centers at melanin-PSi heterojunctions as indicated by an increment of silicon-hydrogen (Si–H) and silicon-oxygen (Si–O) defects, as proven by infrared (FT-IR). A remarkable decrease in microsecond-time components in the pristine PSi towards nanosecond decay times with melanin indicates an increase in radiative recombination centers. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) shows the distribution of small grains of melanin on the surface of the PSi up to the appearance of a melanin thin film [

71]. In a second study, melanin increases the energy efficiency of a solar panel by 3% (with a total increment in the solar cell conversion efficiency of around 44%), which depends on the uniform distribution of the melanin/PSP colloidal solution over the glass [

72].

A third study demonstrated that eco-friendly and low-cost materials (melanin + FeOx) can be utilized to fabricate supercapacitors capable of operating optimally at high temperatures (70 ºC), owing to the enhancement of ion conductivity through the electrodes. This device maintained a high capacitance retention of 84–88 % after 5000 cycles of charge-discharge or 1000 bending cycles. Raman and XPS spectroscopies revealed a higher presence of oxygen-vacancy defects and Fe

3+/Fe

2+ species on electrodes made with melanin and FeOx [

73].

The sustainable production approach developed in this study addresses critical environmental and economic considerations for commercial melanin production. The organic cultivation methods ensure environmental sustainability while maintaining consistent product quality over 10 years of annual production. The green extraction protocols using organic acids eliminate the need for toxic solvents and reduce environmental impact while preserving bioactive properties. The production economics compare favourably with synthetic melanin alternatives, particularly when considering the additional functional benefits derived from the natural source material. The demonstrated production rates and yields support commercial viability, with potential for further optimization through bioprocess engineering and scale-up strategies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Standardized Cultivation

Mucuna ceniza seeds were obtained from plants cultivated under organic conditions in Tepecoacuilco, State of Guerrero, Mexico (18°18′0″ N, 99°29′0″ W). The cultivation was conducted on farmland fertilized exclusively with cattle manure, without the use of synthetic chemicals or pesticides, thereby ensuring compliance with organic certification standards and promoting environmental sustainability. The cultivation process was entirely dependent on the natural rain-based season, typically extending from June to October. Seeds were harvested at optimal maturity, cleaned to remove debris, and stored under controlled conditions (4 °C, 60% relative humidity) to preserve L-DOPA content and prevent degradation of bioactive compounds.

4.2. Sustainable L-DOPA Extraction and Standardization

The standardized extraction procedure involved grindin g clean, dried

M. ceniza seeds through a 2 mm mesh, thereby increasing the surface area for extraction while maintaining cellular integrity and preserving bioactive compounds. The ground material was extracted with aqueous solutions of acetic acid (2% v/v) and citric acid (1% w/v) at room temperature for 24 hours under continuous agitation. The extract was filtered, concentrated under reduced pressure, and lyophilized to obtain a stable powder enriched in L-DOPA [

24].

4.3. Melanin Conversion Optimization in Biorreactor

Melanin production was conducted in a 3-L stirred-tank bioreactor (Applikon, The Netherlands) using the standardized L-DOPA extract as starting material. The bioreactor system was equipped with two six-blade Rushton turbines for efficient mixing and mass transfer, essential for the oxidative polymerization reactions leading to melanin formation.

Temperature control was achieved using a jacketed vessel connected to a thermostatic bath, which maintained a temperature of 26 °C, based on preliminary optimization studies. The pH was maintained at 11.0 using automated addition of 1 M NaOH solution. Aeration was provided at 2.5 vvm (volume of air per volume of medium per minute) through a sparger system to ensure adequate oxygen supply for the oxidative polymerization process.

The biotransformation process was monitored through regular sampling and analysis of L-DOPA consumption, by TLC, and pH stability.

4.4. Melanin Isolation and Purification

Following biotransformation, the melanin product was isolated through a multi-step purification process designed to remove residual substrate, salts, and other impurities while preserving the polymer structure. The bioreactor contents were acidified to pH 3.0 to precipitate the melanin, which was then collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 minutes. The crude melanin was washed repeatedly with distilled water until the washings were colorless, followed by acid washing (0.1 M HCl) to remove metal ions and alkaline washing (0.1 M NaOH) to remove low-molecular-weight impurities. The purified melanin was lyophilized and stored under desiccated conditions for analytical characterization.

4.5. Elemental Analysis

Elemental composition (C, H, N, S) was determined using a CHNS elemental analyzer (PerkinElmer 2400 Series II) with acetanilide as standard. Samples were combusted at 925 °C in a pure oxygen atmosphere, and combustion products were analysed by gas chromatography with thermal conductivity detection.

4.6. Thin Layer Chromatography

Melanin samples (20 mg) were dissolved in 1 mL DMSO, sonicated for 5 minutes, and applied to silica gel TLC plates (Merck 60 F254). Development was performed using a n-butanol:acetic acid:water (70:20:10 v/v/v) mobile phase, and melanin spots were visualized with iodine staining.

4.7. Analytical Characterization Methods

4.7.1. UV-Visible Spectroscopy

UV-visible spectra were recorded using a double-beam spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-2600) in the wavelength range of 200-900 nm. 20 mg of synthetic (from Sigma, prepared by oxidation of tyrosine with hydrogen peroxide) and vegetal melanin samples were dissolved in 1 mL DMSO. The mixture was vigorously shaken for 2 min and then ultrasonicated for 5 min. For the lecture, the sample was diluted 1:10 with distilled water, and the baseline correction was performed using the solvent blank, and the spectra were normalized for comparative analysis.

4.7.2. FTIR Spectroscopy

Melanin samples were analysed using mid-infrared spectroscopy with attenuated total reflectance (ATR) equipped with a diamond crystal (Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS50). 5 mg of melanin was placed directly on the ATR crystal with optimal pressure applied to ensure spectral uniformity. Spectra were obtained by averaging 64 scans at a 4 cm⁻¹ resolution over the range of 4000-500 cm⁻¹, under ambient conditions.

4.7.3. Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectra were acquired using a DXR3xi Raman imaging microscope (Thermo Scientific, USA) equipped with a 10X objective and a confocal pinhole set to 25 μm in diameter. The excitation wavelength was 532 nm with power settings of 2-5 mW to prevent sample degradation. Spectra were acquired over the range of 100-3500 cm⁻¹ with a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹.

4.7.4. NMR Spectroscopy

¹H and ¹³C-NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance spectrometer operating at 300 MHz, using DMSO-d6 as solvent and tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal standard.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. When applied, statistical significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software.

5. Conclusions

The decade-long organic cultivation of Mucuna pruriens var. ceniza and standardized extraction protocols have established a reliable supply chain for high-quality starting material, yielding L-DOPA concentrations of 56% (w/w)—among the highest reported for sustainable extraction methods. This approach not only preserves the bioactive compounds responsible for the demonstrated antioxidant and neuroprotective properties of Mucuna extracts but also enables the optimized biotechnological production process that sets a new benchmark for plant-derived melanin synthesis, achieving unprecedented production rates of 1526.23 ± 10.78 mg L⁻¹ h⁻¹.

Comprehensive analytical characterization through elemental composition analysis provided definitive classification of the product as eumelanin, while multi-technique spectroscopic validation using UV-visible, FTIR, Raman, and NMR spectroscopy confirmed the production of authentic eumelanin with structural characteristics equivalent to commercial synthetic standards. Notably, the M. ceniza-derived eumelanin exhibits enhanced nitrogen content (11.85%), suggesting the incorporation of amino acid moieties that could confer superior biocompatibility and provide additional functional groups for chemical modification.

The integration of sustainable production methodology with proven optoelectronic capabilities positions this eumelanin as a high-value natural product that addresses critical environmental and economic considerations essential for commercial viability. The demonstrated scalability and reproducibility of the process, combined with the exceptional purity and functional properties of the final product, establish a compelling case for industrial implementation.

This study not only validates Mucuna ceniza as a sustainable source for eumelanin production but also opens new avenues for the development of bio-based, high-performance materials that can reduce our dependence on synthetic counterparts while potentially offering enhanced functionality. The work represents a significant advancement in the field of natural product biotechnology and sustainable materials science.

Future research should focus on exploring the full potential of this novel eumelanin in specific optoelectronic applications, including organic photovoltaics, biocompatible sensors, and energy storage devices. Additionally, further investigation into the structure-property relationships governing its unique performance characteristics will be crucial for optimizing its application-specific properties and unlocking its full commercial potential.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Linear correlation between the logarithm of the absorbance and wavelength for melanins; Figure S2: FTIR spectrum of Mucuna and synthetic melanins; Figure S3: H-NMR spectra comparison of Mucuna melanin and Catharsius molossus L. melanins; Figure S4: Liquid 13C-NMR spectrum of Mucuna melanin.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L.H.-O. and A.M.-A.; methodology, A.L.H.-O., P.A.H.-H., A.R.-S., D.M.P.-C., D.C.-O., A.H.-G. and M.A.R.-V.; validation, A.L.H.-O.; formal analysis, P.A.H-H., A.R.-S., D.M.P.-C., D.C.-O., A.H.-G.; investigation, A.L.H.-O., M.A.R.-V. and A.M.-A.; resources, A.L.H.-O. and A.M.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, P.A.H.-H., A.M.-A.; writing—review and editing, A.M.-A., P.A.H.-H.; visualization, P.A.H-H., A. R.-S., D.M.P.-C., D.C.-O., and A.H.-G.; supervision, A.L.H.-O. and A.M.-A.; project administration, A.L.H.-O. and A.M.-A.; funding acquisition, A.L.H.-O. and A.M.-A.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Evogenia and IDEA Guanajuato through the grant numbers CFINN-0058 (2015-2017), MA-CFINN0997 (2018-2019) and MA-CFINN0965 (2020-2021), and the APC was funded by Evogenia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/

supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The Authors thank Lilian Iraís Olvera Garza, María de la Paz Orta Pérez, Eden Morales Narvaéz, Mercedes G. López Pérez, Rubi Reséndiz Ramírez, Alicia Chagolla, and Berenice Cuevas for their help with analytical methods and equipment used at Cinvestav and UNAM.

Conflicts of Interest

Evogenia has registered the commercial mark “biomelanin” for this vegetal melanin. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DHI |

5,6-dihydroxyindole |

| DHICA |

5,6-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid |

| vvm |

volume of air per volume of medium per minute |

| DMSO |

Dimethyl sulfoxide |

References

- Solano, F. Melanins: Skin Pigments and Much More—Types, Structural Models, Biological Functions, and Formation Routes. New J. Sci. 2014, 2014, 498276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pralea, I.-E.; Moldovan, R.-C.; Petrache, A.-M.; Ilieș, M.; Hegheș, S.-C.; Ielciu, I.; Nicoară, R.; Moldovan, M.; Ene, M.; Radu, M.; et al. From Extraction to Advanced Analytical Methods: The Challenges of Melanin Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bothma, J.P.; de Boor, J.; Divakar, U.; Schwenn, P.E.; Meredith, P. Device-Quality Electrically Conducting Melanin Thin Films. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 3539–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, P.; Sarna, T. The Physical and Chemical Properties of Eumelanin. Pigment Cell Res. 2006, 19, 572–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surwase, S.N.; Jadhav, S.B.; Phugare, S.S.; Jadhav, J.P. Optimization of Melanin Production by Brevundimonas Sp. SGJ Using Response Surface Methodology. 3 Biotech 2013, 3, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, A.B.; Fitzpatrick, T.B. Biochemistry of Melanin Formation. Physiol. Rev. 1950, 30, 91–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Liu, M.; Huang, H.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Y. Recent Advances and Progress on Melanin-like Materials and Their Biomedical Applications. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 1858–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuzzubbo, S.; Carpentier, A.F. Applications of Melanin and Melanin-Like Nanoparticles in Cancer Therapy: A Review of Recent Advances. Cancers 2021, 13, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczek, A.; Kondoh, H.; Mishima, Y. Composition of Mammalian Eumelanins: Analyses of DHICA-Derived Units in Pigments From Hair and Melanoma Cells. Pigment Cell Res. 1996, 9, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peles, D.N.; Lin, E.; Wakamatsu, K.; Ito, S.; Simon, J.D. Ultraviolet Absorption Coefficients of Melanosomes Containing Eumelanin As Related to the Relative Content of DHI and DHICA. J Phys Chem Lett 2010, 1, 2391–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulin, J.V.; Coleone, A.P.; Batagin-Neto, A.; Burwell, G.; Meredith, P.; Graeff, C.F.O.; Mostert, A.B. Melanin Thin-Films: A Perspective on Optical and Electrical Properties. J Mater Chem C 2021, 9, 8345–8358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A.; Ghosh, D. Elucidating the Structure of Melanin and Its Structure–Property Correlation. Acc Chem Res 2025, 58, 1509–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulin, J.V.; Graeff, C.F.O. From Nature to Organic (Bio)Electronics: A Review on Melanin-Inspired Materials. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 14514–14531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, W.; Razak, N.N.A.N.A.; Dheyab, M.A.; Salem, F.; Aziz, A.A.; Alanezi, S.T.; Oladzadabbasabadi, N.; Ghasemlou, M. Melanin-Driven Green Synthesis and Surface Modification of Metal and Metal-Oxide Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 2503017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallini, C.; Vitiello, G.; Adinolfi, B.; Silvestri, B.; Armanetti, P.; Manini, P.; Pezzella, A.; d’Ischia, M.; Luciani, G.; Menichetti, L. Melanin and Melanin-Like Hybrid Materials in Regenerative Medicine. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Naggar, N.E.-A.; Saber, W.I.A. Natural Melanin: Current Trends, and Future Approaches, with Especial Reference to Microbial Source. Polymers 2022, 14, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Rahman, S.; Abbas, S.A.; Singh, A.; Rahman, U.; Sharma, M.; Mir, N.R.; Kapoor, N.; Kurian, N.K. Melanin: Comprehensive Insights into Pathways and Sustainable Applications. Curr Pharmacol Rep 2025, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glagoleva, A.Y.; Shoeva, O.Y.; Khlestkina, E.K. Melanin Pigment in Plants: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghajanyan, A.E.; Hambardzumyan, A.A.; Minasyan, E.V.; Hovhannisyan, G.J.; Yeghiyan, K.I.; Soghomonyan, T.M.; Avetisyan, S.V.; Sakanyan, V.A.; Tsaturyan, A.H. Efficient Isolation and Characterization of Functional Melanin from Various Plant Sources. Int J Food Sci Tech 2024, 59, 3545–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamdar, S.; Joshi, S.; Bapat, V.; Jadhav, J. Innovative Use of Mucuna Monosperma (Wight) Callus Cultures for Continuous Production of Melanin by Using Statistically Optimized Biotransformation Medium. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 170, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisden, C.M.; Adesogan, A.T.; Szabo, N.J. Effect of Sonication and Two Solvent Extraction Methods on the L-Dopa Concentration and Nutritional Value of Mucuna Pruriens 2008.

- Castillo-Caamal, J.B.; Jiménez-Osornio, J.J.; López-Pérez, A.; Aguilar-Cordero, W.; Castillo-Caamal, A.M. Feeding Mucuna Beans to Small Ruminants of Mayan Farmers in the Yucatán Peninsula, México. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosystems 2003, 1, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Koutika, L.-S.; Hauser, S.; Henrot, J. Soil Organic Matter Assessment in Natural Regrowth, Pueraria Phaseoloides and Mucuna Pruriens Fallow. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Orihuela, A.L.; Castro-Cerritos, K.V.; López, M.G.; Martínez-Antonio, A. Compound Characterization of a Mucuna Seed Extract: L-Dopa, Arginine, Stizolamine, and Some Fructooligosaccharides. Compounds 2023, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, B.J.; Suman, B.; Venkataswamy, M.; ThyagaRaju, K. The Traditional Uses and Pharmacological Activities of Mucuna Pruriens (l) Dc: A Comprehensive Review. Indoam. J. Pharm. Res. 2017, 7516–7525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampariello, L.R.; Cortelazzo, A.; Guerranti, R.; Sticozzi, C.; Valacchi, G. The Magic Velvet Bean of Mucuna Pruriens. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2012, 2, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theansungnoen, T.; Nitthikan, N.; Wilai, M.; Chaiwut, P.; Kiattisin, K.; Intharuksa, A. Phytochemical Analysis and Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Antiaging Activities of Ethanolic Seed Extracts of Four Mucuna Species. Cosmetics 2022, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Bermudez, A.; Diaz-Ruiz, A.; Silva-García, L.R.; Gines-Francisco, E.M.; Noriega-Navarro, R.; Rios, C.; Romero-Sánchez, H.A.; Arroyo, D.; Landa, A.; Navarro, L. Mucuna Pruriens, a Possible Treatment for Depressive Disorders. Neurol. Int. 2024, 16, 1509–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Bermudez, A.; Trejo-Chávez, R.; Martínez-Vargas, M.; Pérez-Arredondo, A.; de los Ángeles Martínez-Cardenas, M.; Diaz-Ruiz, A.; Rios, C.; Romero-Sánchez, H.A.; Martínez-Antonio, A.; Navarro, L. Effect of Mucuna Pruriens Seed Extract on Depression-like Behavior Derived from Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats. Biomed. Taipei 2024, 14, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanani, T.; Singh, R.; Shah, S.; Kumari, P.; Kumar, S. Comparison of Green Extraction Methods with Conventional Extraction Method for Extract Yield, L-DOPA Concentration and Antioxidant Activity of Mucuna Pruriens Seed. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2015, 8, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesoro, C.; Lelario, F.; Ciriello, R.; Bianco, G.; Di Capua, A.; Acquavia, M.A. An Overview of Methods for L-Dopa Extraction and Analytical Determination in Plant Matrices. Separations 2022, 9, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran-Ly, A.N.; Reyes, C.; Schwarze, F.W.M.R.; Ribera, J. Microbial Production of Melanin and Its Various Applications. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 36, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghajanyan, A.E.; Vardanyan, A.A.; Hovsepyan, A.C.; Hambardzumyan, A.A.; Filipenia, V.; Saghyan, A.C. Development of Technology for Obtaining Water-Soluble Bacterial Melanin and Determination of Some of Pigment Properties. BioTechnologia 2017, 98, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Zhou, X.; McCallum, N.C.; Hu, Z.; Ni, Q.Z.; Kapoor, U.; Heil, C.M.; Cay, K.S.; Zand, T.; Mantanona, A.J.; et al. Unraveling the Structure and Function of Melanin through Synthesis. J Am Chem Soc 2021, 143, 2622–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harki, E.; Talou, T.; Dargent, R. Purification, Characterisation and Analysis of Melanin Extracted from Tuber Melanosporum Vitt. Food Chem. 1997, 58, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Liu, X.; Xiang, K.; Chen, L.; Wu, X.; Lin, W.; Zheng, M.; Fu, J. Characterization of the Physicochemical Properties and Extraction Optimization of Natural Melanin from Inonotus Hispidus Mushroom. Food Chem. 2019, 277, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Xie, C.; Fan, G.; Gu, Z.; Han, Y. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Melanin from Auricularia Auricula Fruit Bodies. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2010, 11, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomovskiy, I.; Podgorbunskikh, E.; Lomovsky, O. Effect of Ultra-Fine Grinding on the Structure of Plant Raw Materials and the Kinetics of Melanin Extraction. Processes 2021, 9, 2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwannarach, N.; Kumla, J.; Watanabe, B.; Matsui, K.; Lumyong, S. Characterization of Melanin and Optimal Conditions for Pigment Production by an Endophytic Fungus, Spissiomyces Endophytica SDBR-CMU319. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakamatsu, K.; Ito, S. Recent Advances in Characterization of Melanin Pigments in Biological Samples. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 8305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; Cui, L.; Wang, X.; Cai, N.; Li, H.; Ren, S.; Li, T.; Shu, L. Synthesis and Structural Characteristics Analysis of Melanin Pigments Induced by Blue Light in Morchella Sextelata. Front Microbiol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhusudhan, D.N.; Mazhari, B.B.Z.; Dastager, S.G.; Agsar, D. Production and Cytotoxicity of Extracellular Insoluble and Droplets of Soluble Melanin by Streptomyces Lusitanus DMZ-3. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 306895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Xing, R.; Yang, H.; Gao, K.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Yu, H.; Li, P. Eumelanin: A Natural Antioxidant Isolated from Squid Ink by New Enzymatic Technique and Prediction of Its Structural Tetramer. LWT 2023, 188, 115464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozzi, V.; Perna, G.; Carmone, P.; Gallone, A.; Lastella, M.; Mezzenga, E.; Quartucci, G.; Ambrico, M.; Augelli, V.; Biagi, P.F.; et al. Optical and Photoelectronic Properties of Melanin. Thin Solid Films 2006, 511–512, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, F. Melanin and Melanin-Related Polymers as Materials with Biomedical and Biotechnological Applications—Cuttlefish Ink and Mussel Foot Proteins as Inspired Biomolecules. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-EL-Aziz, A.S.; Abed, N.N.; Mahfouz, A.Y.; Fathy, R.M. Production and Characterization of Melanin Pigment from Black Fungus Curvularia Soli AS21 ON076460 Assisted Gamma Rays for Promising Medical Uses. Microb Cell Fact 2024, 23, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, G.; Lasalvia, M.; Capozzi, V. Vibrational Spectroscopy of Synthetic and Natural Eumelanin. Polym. Int. 2016, 65, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, C.; Ma, J.; Tan, C.; Yang, Z.; Ye, F.; Long, C.; Ye, S.; Hou, D. Preparation of Melanin from Catharsius Molossus L. and Preliminary Study on Its Chemical Structure. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2015, 119, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khatib, M.; Harir, M.; Costa, J.; Baratto, M.C.; Schiavo, I.; Trabalzini, L.; Pollini, S.; Rossolini, G.M.; Basosi, R.; Pogni, R. Spectroscopic Characterization of Natural Melanin from a Streptomyces Cyaneofuscatus Strain and Comparison with Melanin Enzymatically Synthesized by Tyrosinase and Laccase. Molecules 2018, 23, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno, S.A.; Shamir, J. Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) and FTIR Characterization of the Sepia Melanin Pigment Used in Works of Art. J. Mol. Struct. 2008, 873, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván, I.; Araujo-Andrade, C.; Marro, M.; Loza-Alvarez, P.; Wakamatsu, K. Raman Spectroscopy Quantification of Eumelanin Subunits in Natural Unaltered Pigments. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2018, 31, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Md, H.L.; Chen, M.X.K.; M.d, A.A.; M.d, D.I.M.; Zeng, H. Raman Spectroscopy of in Vivo Cutaneous Melanin. JBO 2004, 9, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván, I.; Jorge, A. Dispersive Raman Spectroscopy Allows the Identification and Quantification of Melanin Types. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 1425–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xiao, J.; Liu, B.; Zhuang, Y.; Sun, L. Study on the Preparation and Chemical Structure Characterization of Melanin from Boletus Griseus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabor, D.P.; Roch, L.M.; Saikin, S.K.; Kreisbeck, C.; Sheberla, D.; Montoya, J.H.; Dwaraknath, S.; Aykol, M.; Ortiz, C.; Tribukait, H.; et al. Accelerating the Discovery of Materials for Clean Energy in the Era of Smart Automation. Nat Rev Mater 2018, 3, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegab, H.; Shaban, I.; Jamil, M.; Khanna, N. Toward Sustainable Future: Strategies, Indicators, and Challenges for Implementing Sustainable Production Systems. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 36, e00617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, W.; Gu, Z.; Wang, L.; Guo, L.; Ma, S.; Li, C.; Sun, J.; Han, B.; Chang, J. Recent Advances and Progress on Melanin: From Source to Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eom, T.; Ozlu, B.; Ivanová, L.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Krajčovič, J.; Shim, B.S. Multifunctional Natural and Synthetic Melanin for Bioelectronic Applications: A Review. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 5489–5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcovici, I.; Coricovac, D.; Pinzaru, I.; Macasoi, I.G.; Popescu, R.; Chioibas, R.; Zupko, I.; Dehelean, C.A. Melanin and Melanin-Functionalized Nanoparticles as Promising Tools in Cancer Research—A Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Rhim, J.-W. New Insight into Melanin for Food Packaging and Biotechnology Applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 4629–4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsouko, E.; Tolia, E.; Sarris, D. Microbial Melanin: Renewable Feedstock and Emerging Applications in Food-Related Systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayaka, D.M.N.S.; Udumann, S.S.; Nuwarapaksha, T.D.; Atapattu, A.J.; Dissanayaka, D.M.N.S.; Udumann, S.S.; Nuwarapaksha, T.D.; Atapattu, A.J. Harnessing the Potential of Mucuna Cover Cropping: A Comprehensive Review of Its Agronomic and Environmental Benefits. C 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magadlela, A.; Makhaye, N.; Pérez-Fernández, M. Symbionts in Mucuna Pruriens Stimulate Plant Performance through Nitrogen Fixation and Improved Phosphorus Acquisition. J Plant Ecol 2021, 14, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Caamal, J.B.; Caamal-Maldonado, J.A.; Jiménez-Osornio, J.J.M.; Bautista-Zúñiga, F.; Amaya-Castro, M.J.; Rodríguez-Carrillo, R. Evaluación de Tres Leguminosas Como Coberturas Asociadas Con Maíz En El Trópico Subhúmedo. Agron. Mesoam. 2010, 21, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yang, H.; Liu, S.; Yu, H.; Li, D.; Li, P.; Xing, R. Melanin: Insights into Structure, Analysis, and Biological Activities for Future Development. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 7528–7543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heppner, F.; Al-Shamery, N.; See Lee, P.; Bredow, T. Tuning Melanin: Theoretical Analysis of Functional Group Impact on Electrochemical and Optical Properties. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 5251–5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostert, A.B. Melanin, the What, the Why and the How: An Introductory Review for Materials Scientists Interested in Flexible and Versatile Polymers. Polymers 2021, 13, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoud, F.; Ismail, A.; Zaher, R.; El Majzoub, R.; Abou-Abbas, L. Mucuna Pruriens Treatment for Parkinson Disease: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. Park. Dis. 2025, 2025, 1319419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite Tavares, R.; Vasconcelos, M.H. de A.; Mathias Dorand, V.A.; Junior, E.U.T.; Toscano, L. de L.T.; Queiroz, R.T. de; Francisco Alves, A.; Magnani, M.; Guzman-Quevedo, O.; Aquino, J. Mucuna Pruriens Treatment Shows Anti-Obesity and Intestinal Health Effects in Obese Rats. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 6479–6489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei, S.; Dagadu, P.; Amoah, B.Y.; Hammond, G.N.A.; Nortey, E.; Obeng-Kyeremeh, R.; Orabueze, I.C.; Asare, G.A. Moderate Doses of Mucuna Pruriens Seed Powder Is Safe and Improves Sperm Count and Motility. Phytomedicine Plus 2023, 3, 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez-Lara, A.; Coutino-Gonzalez, E.; Morales-Morales, F.; Ávila-Gutiérrez, M.A.; Carrillo-Lopez, J.; Hernández-Orihuela, A.L.; Martínez Antonio, A. Vegetal Melanin-Induced Radiative Recombination Centers in Porous Silicon. Opt. Mater. 2023, 143, 114182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez-Lara, A.; Bautista-Bustamante, E.; Morales-Morales, F.; Moreno-Moreno, M.; Mendoza-Ramirez, M.C.; Morales-Sánchez, A.; Hernández-Orihuela, L.; Antonio, A.M. Synergistic Effects of Vegetal Melanin and Porous Silicon Powder to Improve the Efficiency of Solar Panel. Sol. Energy 2025, 287, 113241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua-Chávez, M.L.; Garcés-Patiño, L.A.; Rodriguez-Gonzalez, C.; Meza-Gordillo, R.; Martínez-Antonio, A.; Ruiz-Baltazar, A. de J.; Oliva, J. The Role of Green Redox Powder (Melanin) to Enhance the Capacitance of Graphene/FeOx Based Supercapacitors. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2025, 102, 102048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).