Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results

Symbiotic Relationship

Evidence from Behavioral Experiments

Evidence from Neural Mechanism Experiments

Evidence from Genetic Control Experiments

Tension and Elasticity

Evidence for Tension

Evidence for Elasticity

4. Discussion

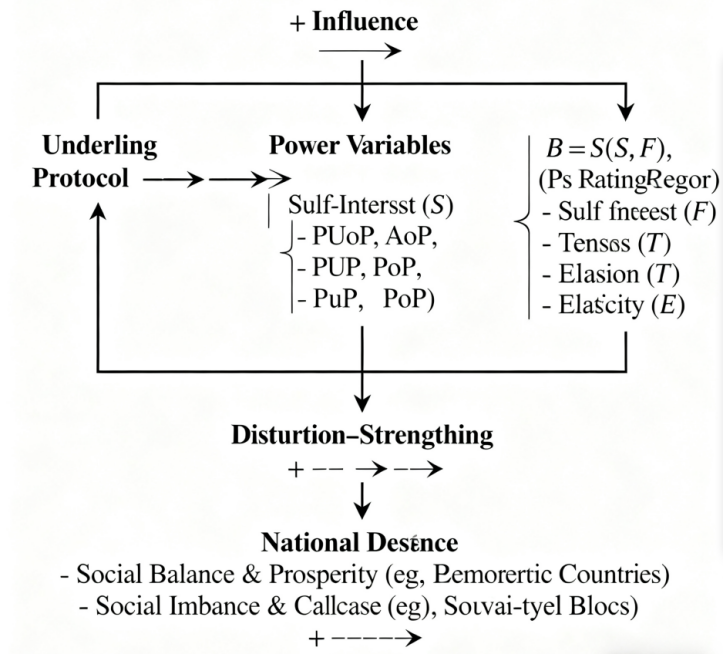

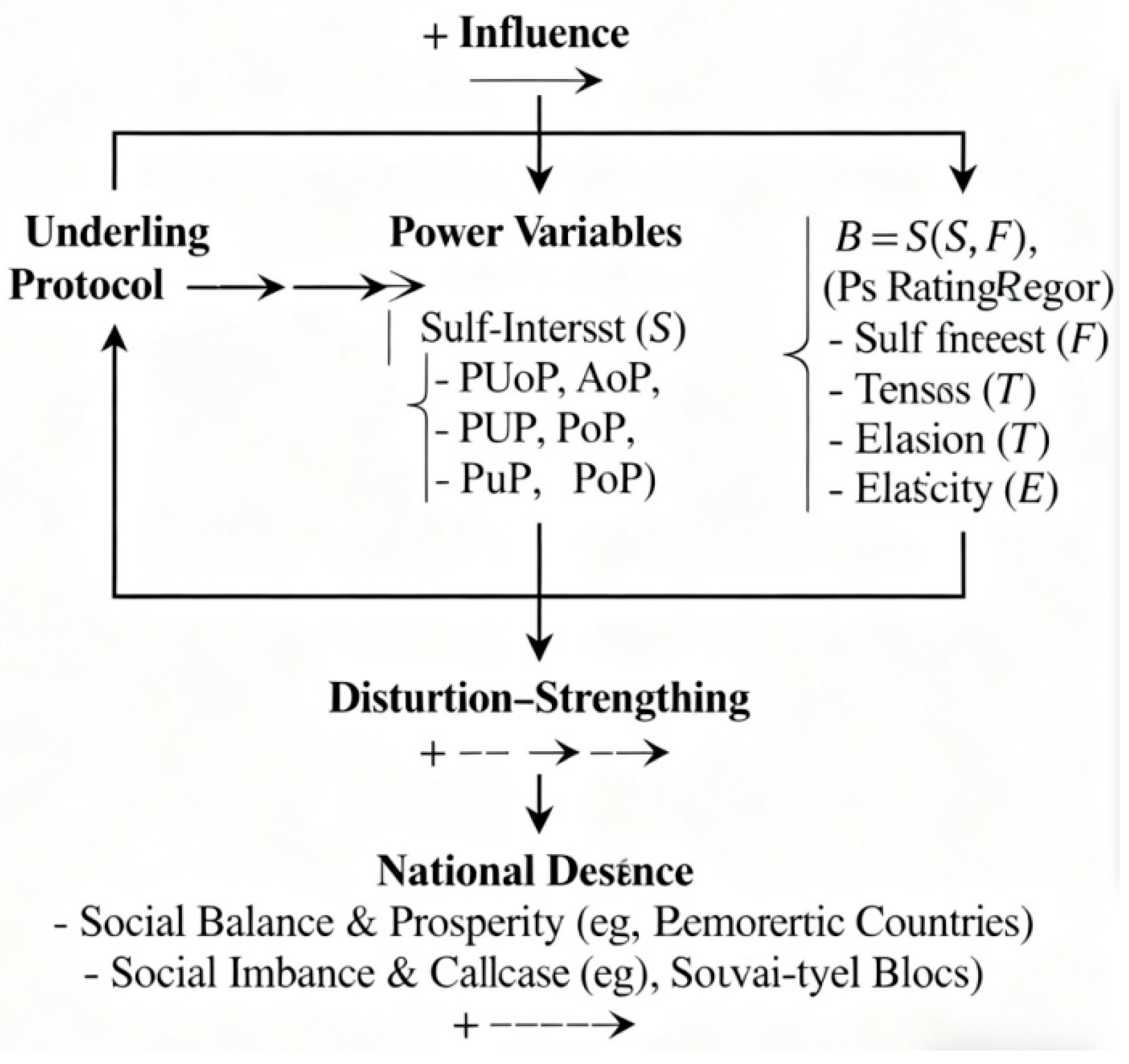

5. The Special Variable

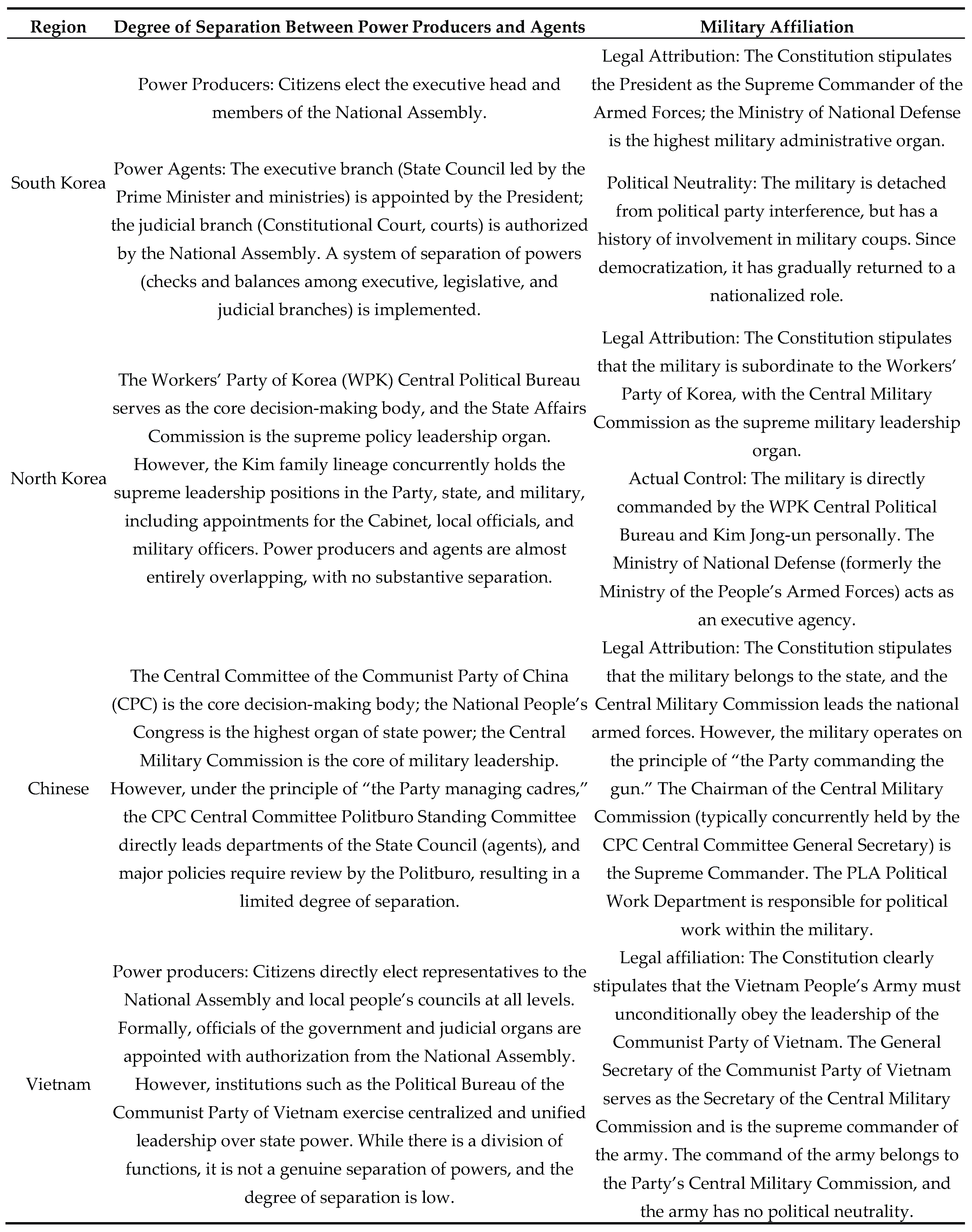

Contemporary Observations

Classification of Power

- Scores of 8.5–10 points fall into the category of Public Use of Power (PUoP);

- Scores of 7.0–8.4 points are classified as Flawed Democracies approximating Public Use of Power;

- Scores of 5.0–6.9 points are classified as Abuse of Power (AoP);

- Scores of 3.0–4.9 points are classified as Private use of public power (PuP);

- Scores of 0.0–2.9 points are classified as Privatization of Power (PoP).

Historical Observations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hsu M, Anen C, Quartz SR. The right and the good: distributive justice and neural encoding of equity and efficiency.Science.2008 May 23;320(5879):1092-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plato.(2010).The Republic(Gu Shouguan, Trans.). Changsha:Yuelu Press.(pp. 353d, 353e). ISBN 978-7-80761-373-2.

- 3a.Aristotle.(2003).Nicomachean Ethics(Liao Shenbai, Trans. & Annotated). Beijing: Commercial Press.(pp.1131a,1131b) ISBN7-100-03575-9.

- 3b.Aristotle.(2003).Nicomachean Ethics (Liao Shenbai,Trans.& Annotated). Beijing: Commercial Press. (pp. 134-151, Book V “Justice”, 1131a10-1135a10). “A ruler is the guardian of justice. Since he is the guardian of justice, he is also the guardian of equality”(p.148,1134b35). ISBN 7100035759.

- Hume, D. (1980).A Treatise of Human Nature(Vol. 1 & 2) (Guan Wenyun, Trans.; Zheng Zhixiang, Rev.).Beijing: Commercial Press. (Book III “Morals”). ISBN 7-100-01165-5.

- Kant, I. (2013).Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals: Annotated Edition (Li Qiuling, Trans. & Annotated). Beijing: China Renmin University Press. (Chapter 2 “Transition from Popular Moral Philosophy to the Metaphysics of Morals”). ISBN 978-7-300-16845-6.

- 6a. Smith, A.(2014).The Theory of Moral Sentiments(Jiang Ziqiang, Qin Beiyu, Zhu Zhongdi, & Shen Kaizhang, Trans.). Beijing: Commercial Press. (pp. 5-6, Book I, Section 1). ISBN 978-7-100-09943-1.

- 6b. Smith, A.(2014).The Theory of Moral Sentiments(Jiang Ziqiang, Qin Beiyu, Zhu Zhongdi, & Shen Kaizhang, Trans.). Beijing: Commercial Press. (pp. 102-103, Book II, Part II, Chapter 2 “Of the Sense of Justice, Remorse, and the Consciousness of Merit”). ISBN 978-7-100-09943-1.

- 6c. Smith, A. (2018). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (Guo Yanan, Trans.). Shantou: Shantou University Press. (p. 14, Book I, Chapter 2 “Of the Principle which Gives Occasion to the Division of Labour”) (reprinted June 20). ISBN 978-7-5658-3459-2.

- Rawls, J. (1988).A Theory of Justice (He Huaihong, et al., Trans.). Beijing: China Social Sciences Press. (Chapter 1 “Justice as Fairness”; Chapter 3 “The Original Position”) (reprinted May 2012). ISBN 978-7-5004-0244-2.

- Harsanyi, John (1977). Morality and the Theory of Rational Behavior. Social Research: An International Quarterly 44(4):623-656.

- Pareto,V.(2016).The Mind and Society (Revised Edition) (Tian Shigang, Trans.). Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press (China). (Chapter 9 “General Forms of Society”).ISBN 978-7-5097-8533-1.

- Wang, D. D. (2013).Lectures on New Political Economy: Reflections on Justice, Efficiency, and Public Choice in China. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House. (Preface; Lectures 1-3).ISBN 978-7-208-11470-8.

- Williamson, O. E. (2017). The Economic Institutions of Capitalism: Firms, Markets, Relational Contracting (Duan Yicai & Wang Wei, Trans.). Beijing: Commercial Press. (Chapter 2 “The Contractual Man”; Chapter 3 “The Governance of Contractual Relations”) (Original work published 1985). ISBN 978-7-100-13859-8.

- 12a. Hayek, F. A.(1997).The Constitution of Liberty (Deng Zhenglai, Zhang Shoudong, & Li Jingbing, Trans.). Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company. (pp. 80-81, Chapter 4 “Freedom, Reason, and Tradition”; Chapter 10 “Law, Command, and Order”). ISBN 7-108-01104-2.

- 12b. Hayek, F. A.(2021).Law, Legislation and Liberty (3 vols.) (Deng Zhenglai, Zhang Shoudong, & Li Jingbing, Trans.). Beijing: Encyclopedia of China Publishing House. ISBN 9787520209847.

- 12c.Hayek, F. A. (2000). The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism (Feng Keli, et al., Trans.). Beijing: China Social Sciences Press. (pp. 33-34, Chapter 2 “The Origins of Liberty, Property and Justice”; “Where there is no property, there is no justice”). (Series: Western Modern Thought Series). ISBN: 7-5004-2793-X.

- 13.Güth W.et al.,1982( Güth W.,Schmittberger R., Schwarze B.(1982). An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 3(4), 367–88.

- 14.Knoch D,Pascual-Leone A,Meyer K,Treyer V,Fehr E. Diminishing reciprocal fairness by disrupting the right prefrontal cortex.Science.2006 Nov 3;314(5800):829-32. [CrossRef]

- 15.Colin F.Camerer(2003).Behavioral Game Theory:Experiments in Strategic Interaction,New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- 16.Henrich J, Boyd R, Bowles S, Camerer C, Fehr E, Gintis H, McElreath R, Alvard M, Barr A, Ensminger J, Henrich NS, Hill K, Gil-White F, Gurven M, Marlowe FW, Patton JQ, Tracer D. “Economic man” in cross-cultural perspective: behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies. Behav Brain Sci. 2005 Dec;28(6):795-815; discussion 815-55. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 17.Feng C, Luo YJ, Krueger F. Neural signatures of fairness-related normative decision making in the ultimatum game: a coordinate-based meta-analysis.Hum Brain Mapp.2015 Feb;36(2):591-602. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 18.Wang Y, Zheng D, Chen J, Rao LL, Li S, Zhou Y. Born for fairness: evidence of genetic contribution to a neural basis of fairness intuition. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2019 May 31;14(5):539-548. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- 19.Satpute AB, Lieberman MD. Integrating automatic and controlled processes into neurocognitive models of social cognition. Brain Res. 2006 Mar 24;1079(1):86-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 20.Lieberman MD. Social cognitive neuroscience: a review of core processes. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:259-89. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 21.Barkow J. Cosmides L& Tooby J. Cognitive adaptations forsocial exchange.Barkow J. Cosmides L& Tooby J., editors,The adapied mind(pp.163-228). New York:Oxford University Press.1992.z-library.

- 22.Ulf Büntgen et al.,2500 Years of European Climate Variability and Human Susceptibility.Science331,578-582(2011). [CrossRef]

- 23.Qiang Chen:Climate shocks, dynastic cycles and nomadic conquests: evidence from historical China Oxford Economic Papers Pub Date : 2014-10-25. [CrossRef]

- 24.G. Feichtinger,C.V.Forst,C. Piccardi:A nonlinear dynamical model for the dynastic cycle.Chaos, Solitons & Fractals Pub Date : 1996-2. [CrossRef]

- 25. C. Y. Cyrus Chu,Ronald D. Lee:Famine, revolt, and the dynastic cycle Journal of Population Economics Pub Date : 1994-11. [CrossRef]

- 26.G. Feichtinger , A. J. Novak:Differential game model of the dynastic cycle: 3D-canonical system with a stable limit cycle.Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications(IF1.5)Pub Date:1994-03-01. [CrossRef]

- 27.Stoynov, Pavel.(2018). The Chinese dynastic cycle - historical and quantitative overview. Eleventh International Conference.3-10. Financial and Actuarial Mathematics-FAM-2018 6-10.09.2018,Sofia,Bulgaria Sixth International Conference;IT in Education, Art, Research and Business-ITERB-2018 6-10.09.2018, Sofia, Bulgaria.

- 28.Randall Collins:Prediction in Macrosociology: The Case of the Soviet Collapse American Journal of Sociology (IF 3.6) Pub Date : 1995-05-01. [CrossRef]

- 29.Lu, Peng & Chen, Dianhan. (2021). The life cycle model of Chinese empire dynamics (221 BC–1912 AD). The Journal of Mathematical Sociology.47.1-37. 10.1080/0022250X.2021.1981311.

- 30.Camerer, Colin F, Thaler, Richard H. Ultimatums, dictators and manners[J]. Journal of Economic Perspectives,1995,(9): P.214,P.216. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.9.2.209.

- 31.Daniel Kahneman, Jack L. Knetsch & Richard H. 1986. “Fairness and the Assumptions of Economics,” The Journal of Business, University of Chicago Press, vol. 59(4), PP.285-300, October.Handle: RePEc:ucp:jnlbus:v:59:y:1986:i:4:p:s285-300.

- 32.Falk A, Fehr E, Fischbacher U. On the nature of fair behavior. Economic Inquiry. 2003;41(1):20–26.

- 33.Luke Garrod.(2009).Investigating Motives Behind Punishment and Sacrifice:A Within-Subject Analysis. SSRN Electronic Journal. 10.2139/ssrn.1499888.

- 34.Yamagishi T, Horita Y, Takagishi H, Shinada M, Tanida S, Cook KS. The private rejection of unfair offers and emotional commitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Jul 14;106(28):11520-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 35.Chen, Y. F., Zhou, Y. A., & Song, Z. F. (2011). “Do People Care About Distributive Motivation or Distributive Outcome?” Economic Research Journal,(6),pp.31–44.

- 36.Ruan, Q. S., & Huang, X. H.(2005). “A Review of Western Research on Fairness Preference Theory.” Foreign Economics & Management, (6), pp. 10–16. (Supported by Sino-US Higher Education Cooperation Project, Project No.

- 37.Blount, S. (1995). When social outcomes aren’t fair: The effect of causal attributions on preferences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,63(2),131-144. [CrossRef]

- 38.Sanfey AG, Rilling JK, Aronson JA, Nystrom LE, Cohen JD. The neural basis of economic decision-making in the Ultimatum Game. Science. 2003 Jun 13;300(5626):1755-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 39a. Axelrod, R. (2007). The Evolution of Cooperation (Revised Edition) (Wu Zhijian, Trans.). Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House. (pp. 22-36). ISBN 9787208071452.

- 39b. Axelrod, R. (2008). The Complexity of Cooperation: Based on Models of Competition and Cooperation Among Participants (Liang Jie, Gao Xiaomei, et al., Trans.). Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House. (pp. 20-26). ISBN 9787208075702.

- 40.Xiao Han, Shangmei Ma, Wen-Xu Wang, Angel Sánchez, H. Eugene Stanley, Shinan Cao, Boyu Zhang:Coordination of network heterogeneity and individual preferences promotes collective fairness,Patterns,2025,101293,ISSN 2666-3899. [CrossRef]

- 41.Buckholtz JW, Asplund CL, Dux PE, Zald DH, Gore JC, Jones OD, Marois R. The neural correlates of third-party punishment. Neuron.2008 Dec 10;60(5):930-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 42.Ernst Fehr, Georg Kirchsteiger, Arno Riedl, Does Fairness Prevent Market Clearing? An Experimental Investigation,The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 108, Issue 2, May 1993, Pages 437–459. [CrossRef]

- 43a.Ernst Fehr& Simon Gächter(1999). Cooperation and Punishment in Public Goods Experiments. American Economic Review. 980-994.

- 43b.Ernst Fehr& Simon Gächter, (2002). Altruistic Punishment in Humans. Nature. 415. 137-40. 10.1038/415137a.

- 43c.Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2000). Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. The American Economic Review, 90 (4): 980-994.

- 44.de Quervain DJ, Fischbacher U, Treyer V, Schellhammer M, Schnyder U, Buck A, Fehr E. The neural basis of altruistic punishment.Science.2004 Aug 27;305(5688):1254-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 45.Stallen M,Rossi F,Heijne A,Smidts A,De Dreu CKW,Sanfey AG.Neurobiological Mechanisms of Responding to Injustice. J Neurosci. 2018 Mar 21;38(12):2944-2954. [CrossRef]

- 46.Henrich, Joseph, and others (eds), Foundations of Human Sociality: Economic Experiments and Ethnographic Evidence from Fifteen Small-Scale Societies (Oxford, 2004;online edn,Oxford Academic,20 Jan.2005). [CrossRef]

- 47.Brosnan, S., de Waal, F. Monkeys reject unequal pay.Nature 425, 297–299 (2003). [CrossRef]

- 48.Proctor, D., Williamson, R. A., de Waal, F. B. M., & Brosnan, S. F. (2013). Chimpanzees play the ultimatum game. *Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences*, *110*(6), 2070–2075. [CrossRef]

- 49.Hu J, Hu Y, Li Y, Zhou X. Computational and Neurobiological Substrates of Cost-Benefit Integration in Altruistic Helping Decision. J Neurosci. 2021 Apr 14;41(15):3545-3561. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 50.Liu Y.et al,2019(Liu Y.,Li S.,Lin,W.et al.Oxytocin modulates social value representations in the amygdala.Nat Neurosci 22,633–641(2019). [CrossRef]

- 51.Hu X, Zhang Y, Liu X, Guo Y, Liu C, Mai X. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation over the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex on fairness-related decision-making. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2022 Aug 1;17(8):695-702. [CrossRef]

- 52.Koenigs M, Tranel D. Irrational economic decision-making after ventromedial prefrontal damage: evidence from the Ultimatum Game. The Journal of Neuroscience : the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007 Jan;27(4):951-956. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 53.Sanfey AG, Loewenstein G, McClure SM, Cohen JD. Neuroeconomics: cross-currents in research on decision-making. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006 Mar;10(3):108-16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 54.Sanfey AG, Chang LJ. Multiple systems in decision making.Ann N Y Acad Sci.2008 Apr;1128:53-62. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 55.Buckholtz JW, Marois R. The roots of modern justice: cognitive and neural foundations of social norms and their enforcement.Nat Neurosci.2012 Apr 15;15(5):655-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 56.Gospic K, Sundberg M, Maeder J, Fransson P, Petrovic P, Isacsson G, Karlström A, Ingvar M. Altruism costs-the cheap signal from amygdala. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014 Sep;9(9):1325-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- 57.Brüne M, Scheele D, Heinisch C, Tas C, Wischniewski J, Güntürkün O. Empathy moderates the effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex on costly punishment. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44747. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 58.Fehr E, Camerer CF. Social neuroeconomics: the neural circuitry of social preferences. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007 Oct;11(10):419-27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 59.Bouchard TJ Jr, Lykken DT, McGue M, Segal NL, Tellegen A. Sources of human psychological differences:the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart.Science.1990 Oct12;250(4978):223-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 60.Bouchard, T. J., Jr., & McGue, M..Genetic and environmental influences on human psychological differences.J Neurobiol.2003 Jan;54(1):4-45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 61.Burnham TC. High-testosterone men reject low ultimatum game offers. Proc Biol Sci. 2007 Sep 22;274(1623):2327-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 62.Wallace B, Cesarini D, Lichtenstein P, Johannesson M. Heritability of ultimatum game responder behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Oct 2;104(40):15631-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 63.Myrseth KO, Fishbach A, Trope Y. Counteractive self-control.Psychol Sci.2009 Feb;20(2):159-63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinsson, P., Myrseth K.O.R.,Wollbrant C.(2014). Social dilemmas: when self-control benefits cooperation.Journal of Economic Psychology,45,213-236. [CrossRef]

- 65.Rubinstein A. (2007). Instinctive and cognitive reasoning: a study of response times. The Economic Journal, 117(523), 1243–59.

- 66.Rand DG, Greene JD, Nowak MA. Spontaneous giving and calculated greed. Nature. 2012 Sep 20;489(7416):427-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 67.Van’t Wout M., Chang L.J., Sanfey A.G. (2010). The influence of emotion regulation on social interactive decision-making. Emotion, 10(6), 815–21. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3057682/.

- 68.Dunn B.D., Evans D., Makarova D., White J., Clark L. (2012). Gut feelings and the reaction to perceived inequity: the interplay between bodily responses, regulation, and perception shapes the rejection of unfair offers on the ultimatum game.Cognitive,Affective&Behavioral Neuroscience,12(3),419-29.https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13415-012-0092-z.

- 69.Achtziger A., Alós-Ferrer C., Wagner A.K. (2016). The impact of self-control depletion on social preferences in the ultimatum game. Journal of Economic Psychology, 53,1-16.ISSN 0167-4870. [CrossRef]

- 70.Sütterlin S, Herbert C, Schmitt M, Kübler A, Vögele C. Overcoming selfishness: reciprocity, inhibition, and cardiac-autonomic control in the ultimatum game. Front Psychol. 2011 Jul 27;2:173. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 71.Halali E., Bereby-Meyer Y., Meiran N. (2014). Between self-interest and reciprocity: the social bright side of self-control failure. Journal of Experimental Psychology General, 143(2), 745–55.

- 72.Adam Bear, David G. Rand(2016). Intuition, deliberation, and the evolution of cooperation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(4), 936-941. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4743833/.

- 73.Sanfey AG. Social decision-making: insights from game theory and neuroscience. Science. 2007 Oct 26;318(5850):598-602. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 74.Rilling JK, Sanfey AG. The neuroscience of social decision-making. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62:23-48. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehr, E. ,Schmidt K.M.(1999).A Theory of Fairness,Competition,and Cooperation.The Quarterly Journal of Economics,Volume 114,Issue 3,August 1999,Pages 817-868. [CrossRef]

- 76.Fehr E, Fischbacher U, Gächter S. Strong reciprocity, human cooperation, and the enforcement of social norms. Hum Nat. 2002 Mar;13(1):1-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 77.Bowles S, Gintis H.The evolution of strong reciprocity: cooperation in heterogeneous populations. Theor Popul Biol. 2004 Feb;65(1):17-28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 78.Pillutla, M. M., & Murnighan, J. K. (1996). Unfairness, anger, and spite: Emotional rejections of ultimatum offers.Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 68(3), 208–224. [CrossRef]

- 79.Harlé KM, Chang LJ, van ‘t Wout M, Sanfey AG. The neural mechanisms of affect infusion in social economic decision-making: a mediating role of the anterior insula. Neuroimage. 2012 ;61(1):32-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 80.Hu X, Mai X. Social value orientation modulates fairness processing during social decision-making: evidence from behavior and brain potentials. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2021 Jul 6;16(7):670-682. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- 81.Kaltwasser et al.,2016Kaltwasser L, Hildebrandt A, Wilhelm O, Sommer W. Behavioral and neuronal determinants of negative reciprocity in the ultimatum game. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2016 Oct;11(10):1608-1617. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- 82.Boyd R, Gintis H, Bowles S, Richerson PJ. The evolution of altruistic punishment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Mar 18;100(6):3531-3535. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- 83.Hardin G.(1968).The Tragedy of the Commons.Science162,1243-1248(1968). [CrossRef]

- 84.Rankin, Daniel J. et al.The tragedy of the commons in evolutionary biology.Trends in Ecology & Evolution(2007.12), Volume 22, Issue 12, 643 - 651.

- 85.Soler,M.(2012) Costly Signaling, Ritual and Cooperation: Evidence from Candomblé, an Afro-Brazilian Religion.Evolution and Human Behavior,33,346-356. [CrossRef]

- 86. Salahshour, M.Evolution of costly signaling and partial cooperation. Sci Rep 9, 8792 (2019). [CrossRef]

- 87.Wang H, Wu X, Xu J, Zhu R, Zhang S, Xu Z, et al. (2024) Acute stress during witnessing injustice shifts third-party interventions from punishing the perpetrator to helping the victim. PLoS Biol 22(5):e3002195. [CrossRef]

- 88.Decety J, Yoder KJ. The Emerging Social Neuroscience of Justice Motivation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2017 Jan;21(1):6-14. [CrossRef]

- 89.Boehm, C.(2012).Moral origins: The evolution of virtue,altruism,and shame.Basic Books/Hachette Book Group.ISBN:0465020480.

- 90a.Nowak MA, Sigmund K, 1993.Nowak, M.A. and Sigmund, K. (1993) A Strategy of Win-Stay, Lose Shift That Outperforms Tit-for-Tat in the Prisoner’s Dilemma Game. Nature, 364, 56-58.

- 90b.Nowak MA, Sigmund K. Evolution of indirect reciprocity by image scoring. Nature.1998 Jun 11;393(6685):573-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, MA. MartinA.Nowak,Five Rules for the Evolution of Cooperation.Science 314(5805), 1560-1563 (2006). [CrossRef]

- 92.Wedekind C, Milinski M. Cooperation through image scoring in humans. Science. 2000 ;288(5467):850-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 93.Marsh AA, Stoycos SA, Brethel-Haurwitz KM, Robinson P, VanMeter JW, Cardinale EM. Neural and cognitive characteristics of extraordinary altruists. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Oct 21;111(42):15036-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- 94.Sonne JWH, Gash DM. Psychopathy to Altruism: Neurobiology of the Selfish-Selfless Spectrum. Front Psychol. 2018 Apr 19;9:575. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 95.Bickart KC, Dickerson BC, Barrett LF. The amygdala as a hub in brain networks that support social life. Neuropsychologia. 2014 Oct;63:235-48. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- 96.Knoch D, Schneider F, Schunk D, Hohmann M, Fehr E. Disrupting the prefrontal cortex diminishes the human ability to build a good reputation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(49):20895-20899. [CrossRef]

- 97.Charles Marsh,Indirect reciprocity and reputation management: Interdisciplinary findings from evolutionary biology and economics,Public Relations Review,Volume 44,Issue 4,2018,Pages 463-470,ISSN 0363-8111. [CrossRef]

- 98.Hatemi PK, Medland SE, Klemmensen R, Oskarsson S, Littvay L, Dawes CT, Verhulst B, McDermott R, Nørgaard AS, Klofstad CA, Christensen K, Johannesson M, Magnusson PK, Eaves LJ, Martin NG. Genetic influences on political ideologies: twin analyses of 19 measures of political ideologies from five democracies and genome-wide findings from three populations. Behav Genet. 2014 May;44(3):282-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 99.Schultz W. Multiple reward signals in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2000 Dec;1(3):199-207. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 100.J. P. O’Doherty, Reward representations and reward-related learning in the human brain: Insights from neuroimaging, Curr. Opin. Neurobiol., 14 (6): 769-776 (2004).

- 101.Harbaugh WT, Mayr U, Burghart DR. Neural responses to taxation and voluntary giving reveal motives for charitable donations.Science,2007 Jun 15;316(5831):1622-1625. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 102.Greene JD, Sommerville RB, Nystrom LE, Darley JM, Cohen JD. An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science. 2001 Sep 14;293(5537):2105-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 103.M. R. Delgado, R. H. Frank, E. A. Phelps,Perceptions of moral character modulate the neural systems of reward during the trust game Nat. Neurosci.8, 1611 (2005).

- 104. Krueger F, McCabe K, Moll J, Kriegeskorte N, Zahn R, Strenziok M, Heinecke A, Grafman J. Neural correlates of trust. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Dec 11;104(50):20084-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 105.Moll J, Krueger F, Zahn R, Pardini M, de Oliveira-Souza R, Grafman J. Human fronto-mesolimbic networks guide decisions about charitable donation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Oct 17;103(42):15623-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- 106.Singer T, Seymour B, O’Doherty JP, Stephan KE, Dolan RJ, Frith CD. Empathic neural responses are modulated by the perceived fairness of others. Nature. 2006 Jan 26;439(7075):466-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- 107.Kuhnen CM, Knutson B. The neural basis of financial risk taking. Neuron. 2005 Sep 1;47(5):763-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 108.Preuschoff K, Bossaerts P, Quartz SR. Neural differentiation of expected reward and risk in human subcortical structures. Neuron. 2006 Aug 3;51(3):381-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 109.Feng, Z. H., Wang, K., Wang, C. Q., Meng, Y., Zhu, C. Y., Jin, S. C., & Zhou, S. S. (2006). “The Neural Mechanism of Disgust Emotion Processing.” Chinese Journal of Neurology, 39(10), pp. 655-658.

- 110.Ramirez F, Moscarello JM, LeDoux JE, Sears RM. Active avoidance requires a serial basal amygdala to nucleus accumbens shell circuit.J Neurosci.2015 Feb 25;35(8):3470-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 111.Veselic S, Muller TH, Gutierrez E, Behrens TEJ, Hunt LT, Butler JL, Kennerley SW. A cognitive map for value-guided choice in ventromedial prefrontal cortex. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 Dec 16:2023.12.15.571895. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 112.Farinha AC ,Maia TV.People exert more effort to avoid losses than to obtain gains. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2021 Sep;150(9):1837-1853. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 113.Harbaugh, W. T., Krause, K., & Vesterlund, L. (2001). Are adults better behaved than children? Age, experience, and the endowment effect. Economics Letters, 70(2), 175-181.

- 114.Noritake,A., Ninomiya,T., Kobayashi,K. et al. Chemogenetic dissection of a prefrontal-hypothalamic circuit for socially subjective reward valuation in macaques.Nat Commun 14,4372 (2023). [CrossRef]

- 115.Ishii,K.& Eisen, C.(2020,). Socioeconomic Status and Cultural Difference.Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology.Retrieved 13 Aug.2025. https://oxfordre.com/psychology/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.001.0001/acrefore-9780190236557-e-584.

- 116.Jung Yul Kwon, Alexandra S. Wormley, Michael E.W. Varnum,Changing cultures, changing brains: A framework for integrating cultural neuroscience and cultural change research,Biological Psychology,Volume 162,2021,108087,ISSN 0301-0511. [CrossRef]

- 117.Xinmu Hu, Xiaoqin Mai, Social value orientation modulates fairness processing during social decision-making: evidence from behavior and brain potentials, Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, Volume 16, Issue 7, 21, Pages 670–682. [CrossRef]

- 118.Pugh ZH, Huang J, Leshin J, Lindquist KA, Nam CS. Culture and gender modulate dlPFC integration in the emotional brain: evidence from dynamic causal modeling. Cogn Neurodyn. 2023 Feb;17(1):153-168. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 119.Sutter M. Outcomes versus intentions: on the nature of fair behavior and its development with age. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2007;28: 69-78.

- 120.Güroğlu B, van den Bos W, Rombouts SA, Crone EA. Unfair? It depends: neural correlates of fairness in social context. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2010 Dec;5(4):414-423. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 121.Güroğlu B, van den Bos W, van Dijk E, Rombouts SA, Crone EA. Dissociable brain networks involved in development of fairness considerations: understanding intentionality behind unfairness. Neuroimage. 2011 Jul 15;57(2):634-641. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 122.Bohnet I, Frey BS. Social distance and other-regarding behavior in dictator games: comment. The American Economic Review. 1999;89:335-339.

- 123.Buchan, N. R., Croson, R. T. A., Johnson, E. J., & Wu, G. (2005). Gain and Loss Ultimatums. In J. Morgan (Ed.), Advances in Applied Microeconomics (Vol. 13, pp. 1–24). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- 124.Zhou, X., & Wu, Y. (2011). Sharing losses and sharing gains: Increased demand for fairness under adversity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(3), 582–588.

- 125.Guo X, Zheng L, Zhu L, Li J, Wang Q, Dienes Z, Yang Z. Increased neural responses to unfairness in a loss context. Neuroimage. 2013 Aug 15;77:246-253. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 126.Konow J. Fair shares: accountability and cognitive dissonance in allocation decisions. The American Economic Review. 2000;90:1072–1091.

- 127.Cappelen AW, Hole AD, Sorensen EO, Tungodden B. The pluralism of fairness ideals: an experimental approach. The American Economic Review. 2007;97(3):818–827.

- 128.Almås I, Cappelen AW, Sørensen EØ, Tungodden B. Fairness and the Development of Inequality Acceptance.Science328,1176-1178(2010). [CrossRef]

- 129.Guo X, Zheng L, Cheng X, Chen M, Zhu L, Li J, Chen L, Yang Z. Neural responses to unfairness and fairness depend on self-contribution to the income. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014 Oct;9(10):1498-1505. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 130.Okun, A. M. (2013).Equality and Efficiency: The Big Tradeoff (Chen Tao, Trans.). Beijing: China Social Sciences Press. (p.1,Chapter 1).ISBN 978-7-5161-1757-6.

- 131.Fehr,E.,Gächter,S.& Kirchsteiger G.(1997):”Reciprocity as a Contract Enforcement Device: Experimental Evidence.” Econometrica 65, 833-860.

- 132a.Engelmann, D.& Strobel, M.(2004). Inequality Aversion, Efficiency, and Maximin Preferences in Simple Distribution Experiments. American Economic Review, 94, 857-869. [CrossRef]

- 132b.Engelmann,D.& Strobel, M.(2006).”Inequality Aversion, Efficiency, and Maximin Preferences in Simple Distribution Experiments: Reply.” American Economic Review,96 (5):1918-1923.

- 133.Fehr, Ernst, Michael Naef,& Klaus M. Schmidt.2006.”Inequality Aversion, Efficiency, and Maximin Preferences in Simple Distribution Experiments: Comment.” American Economic Review 96 (5):1912-1917. [CrossRef]

- 134.Debowicz, D., Saporiti, A., & Wang, Y. (2021). Redistribution, Power Sharing, and Inequality Concern.Social Choice and Welfare,57(2), 197-228. [CrossRef]

- 135.Le,M.T.,Saporiti,A.,&Wang,Y.(2021). Distributive politics with other-regarding preferences. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 23(2), 203–227.

- 136.Le, M. T., Saporiti, A., Inequity aversion and the stability of majority rule, Public Choice, 10.1007/s11127-024-01208-7, (2024).

- 137a.Smith,H.(1977).The Russians(Volume I)(Shanghai Editorial Group for International Affairs Digest, Trans.).Shanghai People’s Publishing House (Internal Distribution).pp.395-397.ISBN:3171-341.

- 137b.Smith, H. (1978). The Russians (Volume II) (Shanghai Editorial Group for International Affairs Digest, Trans.). Shanghai People’s Publishing House (Internal Distribution). “Chapter 19: The Outside World: The Scope of Privilege and Pariahdom,” pp. 363-380. ISBN: 3188-9.

- 138.Myers, D. G. (2016). Social Psychology (11th Edition) (Hou Yubo et al., Trans.). Beijing: Posts & Telecom Press. p. 272. (Reprinted 24). ISBN: 978-7-115-41004-7.

- 139.Xu, C.(2024). Institutional Genes: The Origins of China’s Institutions and Totalitarianism (National Taiwan University Press, Ed.) (Vol. 1). Taipei: National Taiwan University Press. (Chapter 6, The Institutional Gene of Totalitarian Ideology; Section 1, Originating from Christianity: The Münster Totalitarian Regime). ISBN: 9789863508984.

- 140.Wikipedia:Kibbutz;”The question was not whethergroup settlement was preferable to individual settlement; it wasrather one of either group settlement or no settlement at all.

- 141.Paula M. Rayman(1982):《Kibbutz Community and Nation Building》,Princeton University Press,2014,ISBN 13:9781400856589.

- 142.Jin, J.(2010).”Game Theory Analysis of the Structural Theory of Internal Stakeholders of Enterprises.” Statistics & Decision, 2010.

- 143.Bo,W.,Chuanhe,H.,Wenzhong,Y.,Feng,D.& Liya,X.(2011).An Incentive-Cooperative Forwarding Model Based on Punishment Mechanism in Wireless Ad Hoc Networks.Journal of Computer Research and Development, 48, 398.

- 144a. Stavrianos, L. S. (2006). A Global History: From Prehistory to the 21st Century (Seventh Revised Edition) (Wu Xiangying, Liang Chimin, Dong Shuhui, & Wang Chang, Trans.). Beijing: Peking University Press. (pp. 7-9).

- 144b. Stavrianos, L. S. (2006). A Global History: From Prehistory to the 21st Century (Seventh Revised Edition) (Wu Xiangying, Liang Chimin, Dong Shuhui, & Wang Chang, Trans.). Beijing: Peking University Press. (pp. 37-39).

- 145.Rachel C. Forbes, Robb Willer, Jennifer E. Stellar:Power as a moral magnifier: Moral outrage is amplified when the powerful transgress.Journal of Experimental Social Psychology(IF3.1) Pub Date:2025-08-08. [CrossRef]

- 146a. Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2014). Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty (Deng Bochen & Wu Guoqing, Trans.). Taipei: Acropolis Books. (pp. 465-470, Chapter 15 “Understanding Wealth and Poverty”). ISBN 13: 9789868879348.

- 146b. Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2014). Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty (Deng Bochen & Wu Guoqing, Trans.). Taipei: Acropolis Books. (pp. 102-103, Chapter 3 “The Making of Wealth and Poverty”; pp. 458-459, Chapter 15 “Understanding Wealth and Poverty”). ISBN 13: 9789868879348.

- 147.North, D. C. (1994). Institutions,Institutional Change and Economic Performance (Liu Shouying,Trans.).Shanghai:Shanghai Sanlian Publishing House.(pp.3-9,100).ISBN: 7542606611.

- 148.Dalio, R.(2021).Principles: The Changing World Order(Cui Pingping & Liu Bo, Trans.). Beijing: China CITIC Press Group. (Chapter 5 “The Big Cycle of Internal Order and Disorder”; Chapter 12 “The Rise of China and the Renminbi’s Big Cycle: ‘How the Typical Dynastic Cycle Occurs’“). ISBN: 9787521719499.

- 149.Voslensky, M.(1984).《Nomenklatura: The Soviet Ruling Class》,New York:Doubleday,ISBN-10:0385176570.

- 150.Fitzpatrick, S. (2000).《Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times: Soviet Russia in the 1930s》,Oxford University Press,ISBN 13:9780195050011.

- 151a. Weber, M. (2004). The Sociology of Domination (Kang Le & Jian Huimei, Trans.). Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press. (pp. 159-164, Chapter 3 “Patriarchal Domination and Patrimonial Domination” [“China”]). ISBN 7563345280.

- 151b.Weber, M. (2004). The Sociology of Domination (Kang Le & Jian Huimei, Trans.). Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press. (Chapter 3 “Patriarchal Domination and Patrimonial Domination”). ISBN 7563345280.

- 152a.Montesquieu. (2011). The Spirit of the Laws (2 Vols.) (Xu Minglong, Trans.). Beijing: Commercial Press. (Chapter 7 “The Relationship Between the Different Principles of the Three Governments and Laws on Frugality, Luxury, and the Status of Women”, Section 7 “The Fatal Consequences of Luxury in China”). ISBN 978-7-100-08001-9.

- 152b.Montesquieu. (2011). The Spirit of the Laws (2 Vols.) (Xu Minglong, Trans.). Beijing: Commercial Press. (Chapter 11, Section 6 “The Political System of England”). ISBN 978-7-100-08001-9.

- 152c.Montesquieu. (1962). Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and Their Decline; with: Reflections on Taste (Wan Ling, Trans.). Beijing: Commercial Press. (p. 54, Chapter 10 “On the Corruption of the Romans”) (Reprinted 1997). ISBN 7-100-01870-6 / 1149.

- 153.Hegel, G. W. F. (2001). The Philosophy of History (Wang Zaoshi, Trans.). Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House. (p. 115, pp. 117-137). ISBN 7-80622-847-0.

- 154.Xia, Z. Y. (2015). A History of Ancient China. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. (Part 2 “Medieval History”, Chapter 1 “The Era of Prosperity (Qin and Han Dynasties)”, Section 17 “Emperor Wen’s Governance of Huang-Lao Thought”). ISBN 978-7-101-09809-9.

- 155.Liang, S. M. (2005). The Essence of Chinese Culture. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House. (pp. 191-211, Chapter 11 “Circulating Between Order and Chaos Without Revolution: ‘Periodic Chaos’“). ISBN 7-208-05507-6.

- 156.Fairbank, J. and E. Reischauer (1960) East Asia: The Great Tradition. Boston, PP.115-116.

- 157.The Bible. Exodus 19:5-6.

- 158.Dong, Z. S. (2012). Chunqiu Fanlu (Zhang Shiliang, Zhong Zhaopeng, & Zhou Guitian, Trans. & Annotated). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. (Reprinted 17). ISBN 978-7-101-08566-2.

- 159.Hobbes, T. (2009). Leviathan (Li Sifu & Li Ting, Trans.). Beijing: Commercial Press. ISBN 978-7-100-06161-2.

- 160.Rousseau, J. J. (1980). The Social Contract (He Zhaowu, Trans.). Beijing: Commercial Press. ISBN 7-100-00492-6.

- 161. Locke, J. (2011). Two Treatises of Government (Second Treatise) (Ye Qifang & Qu Junong, Trans.). Beijing: Commercial Press. (Chapter 2 “Of the State of Nature”). ISBN 978-7-100-07955-6.

- 162.Nietzsche, F.(2018).The Will to Power (Sun Zhouxing, Trans.). Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House. ISBN 978-7-208-15017-1.

- 163.Dershowitz, A. M. (2014).Rights from Wrongs: A Secular Theory of the Origins of Rights (Huang Yuwen, Trans.). Beijing: Peking University Press. (p. 8, Introduction). ISBN 978-7-301-23536-2.

- 164.Buss, D. M. (2015). Evolutionary Psychology: The New Science of the Mind (4th Edition) (Zhang Yong & Jiang Ke, Trans.; Xiong Zhehong, Ed.). Beijing: Commercial Press. (p. 311) (Reprinted 22). ISBN 978-7-100-11053-2. 20 September.

- 165.Boehm, C.(2012).Moral origins: The evolution of virtue, altruism, and shame.Basic Books/Hachette Book Group.ISBN :0465020480.

- 166.He, JZ., Wang, RW., Jensen, C. et al. Asymmetric interaction paired with a super-rational strategy might resolve the tragedy of the commons without requiring recognition or negotiation. Sci Rep 5, 7715 (2015). [CrossRef]

- 167.(美)路易斯·亨利·摩尔根(Lewis Henry Morgan)著;李培茱译《美洲土著的房屋和家庭生活(Houses and House-Life of the American Aborigines,1881)》,北京:中国社会科学出版社,1985.统一书号11190-150.

- 168.Eleanor Leacock:“Women’s Status in EgalitarianSociety:Implications for Social Evolution”,Current Anthropology Volume 19, No. 2,1 June I978.

- https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/204025.

- 169.Sunde, Uwe. (2006). Wirtschaftliche Entwicklung und Demokratie - Ist Demokratie ein Wohlstandsmotor oder ein Wohlstandsprodukt?.Perspektiven der Wirtschaftspolitik.7.471-499. 10.1111/j.1468-2516.2006.00223.x.

- 170.Tasker, Peter (25 February 2016). “Peter Tasker: The flawed ‘science’ behind democracy rankings”. Nikkei Asia.

- 171.Manaev, Oleg; Manayeva, Natalie; Dzmitry, Yuran ().”More State than Nation: Lukashenko’s Belarus”.Journal of International Affairs.65(1):93–113.

- 172.Wikipedia:The Economist Democracy Index. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Economist_Democracy_Index#cite_note-index2015-6.

- 173a.Uruguay Country Overview Page on the World Bank Official Website: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/uruguay.

- 173b.High-Income Countries Comparison Page of the World Bank: https://data.worldbank.org.cn/?locations=CR-XD.

- 173c.Mauritius Country Overview Page of the World Bank: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/mauritius/overview.

- 173d.United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Human Development Report: https://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/MUS.

- 174.Hochmüller, M., & Müller, M. M. (2023). The Myth of Demilitarization in Costa Rica: Following the abolition of the Army, narratives celebrating Central America’s most peaceful nation have masked a militarized policing model shaped by U.S.-sponsored counterinsurgency. NACLA Report on the Americas, 55(4), 370–376. [CrossRef]

- 175.Zhang, J. H. (2013). “The Construction, Expansion and Evolution of the Concept of the ‘Nordic Model’: A Study from the Perspective of Social Policy.” Chinese Journal of European Studies, No. 2, pp. 105-119.

- 176.Arrian. (1979). The Anabasis of Alexander (E. Iliff Robson, English Trans.; Li Huo, Chinese Trans.). Beijing: Commercial Press. (Reprinted 2007). ISBN: 710003812X.

- 177.Barthold, W. (1984). Fourteen Lectures on the History of the Turks in Central Asia (Luo Zhiping, Trans.). Beijing: China Social Sciences Press. (pp. 143-162, Lecture 8 “The Khans of Khwarazm Facing the Mongol Invasion”). ISBN: 11190119.

- 178.Feng, Z. M. (1975). A Comprehensive History of the West (Vol. 3: Greek City-States) (Sparta, Athens). Taipei: Yenching Cultural Enterprise Co., Ltd.

- 179.Boardman, J., et al. (Eds.).(2015).The Oxford History of the Roman World (Guo Xiaoling, et al., Trans.). Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press. ISBN: 978-7-303-16087-7.

- 180.Norwich, J. J.(2021).A History of Venice: The Maritime Republic(Yang Leyan,Trans.).Nanjing:Yilin Press.(Part 3 “European Power”).ISBN 978-7-5447-8577-8.E-book:https://reader.101-g.

- 181.Steven A.Epstein.Genoa and the Genoese, 958-1528[M].P.46.Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.1996.

- 182a. Brownworth, L. (2016). Lost to the West: The Forgotten Byzantine Empire That Rescued Western Civilization (Wu Siya, Trans.). Beijing: China CITIC Press. (Reprinted 2017). ISBN: 9787508668444.

- 182b. Brownworth, L. (2016). Lost to the West: The Forgotten Byzantine Empire That Rescued Western Civilization (Wu Siya, Trans.). Beijing: China CITIC Press. (pp. 53-54, Chapter 4 “Barbarians and Christians”) (Reprinted 2017). ISBN: 9787508668444.

- 183.Balfour, P. (2018).The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire (Luan Lifu, Trans.). Beijing: China CITIC Press. (Appendix: List of Ottoman Sultans). ISBN: 9787508689845.

- 184a. Li, A. S. (2011). Ancient Kingdoms of Africa (Li Anshan, Author). Beijing: Peking University Press. (pp. 39-64, Chapter 2 “Black Pharaohs Ruling Ancient Egypt (Kush)”; pp. 65-88, Chapter 3 “Descendants of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (Aksum)”). ISBN: 978-7-301-18234-5.

- 184b. Li, A. S. (2015). “Nubian Civilization: The Pride of Africa.” Civilization, (03). (Retrieved from CNKI).Tu, E. K. (1985). “The Kingdom of Kush (Part 2): The Meroitic Period.” West Asia and Africa, (04). (Retrieved from CNKI).

- 184c. Li, A. S. (2011). Ancient Kingdoms of Africa (Li Anshan, Author). Beijing: Peking University Press. (pp. 81-82, Chapter 3 “Descendants of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba”). ISBN 978-7-301-18234-5.

- 185.Adejumobi, S. A. (2009).A History of Ethiopia (Dong Xiaochuan, Trans.). Beijing: Commercial Press. (p. 17, Chapter 1 “Ethiopia: Intellectual and Cultural Background”). ISBN: 978-7-100-06899-4.

- 186.Xu, Z. W. (2003).A History of Denmark: The Fairy-Tale Kingdom Sailing into the New Century. Taipei: Sanmin Book Co., Ltd. ISBN: 9571438456.

- 187.Andersson, I. (1963). A History of Sweden (Vols. 1 & 2) (Su Gongjun, Trans.). Beijing: Commercial Press. (Reprinted 1972). Uniform Book Number: 11017-130.

- 188.Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project Expert Group (Ed.). (2001). Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project: Interim Report (1996-2000) - Abridged Version. Beijing: World Publishing Corporation. ISBN: 7506241382.

- 189.Sakamoto, T. (2008).A History of Japan (Wang Xiangrong, Wu Yin, & Han Tieying, Trans.). Beijing: China Social Sciences Press. (Chapter 2 “Early Ancient Period”, Section 2 “The Establishment of a Unified State: ‘Wo of Wei’“) (Reprinted 14). ISBN 978-7-5004-6860-8.

- 190.Machiavelli, N.(2017).Discourses on Livy (Feng Keli, Trans.). Beijing: Central Compilation & Translation Press.(p. 361, Book III, Chapter 9, Section 2)(comparing the different responses of the Romans and Venetians to fortune).ISBN: 978-7-5117-3333-7.

- 191.Li, L. G. (2024).From the Roman Empire to the Holy Roman Empire: European Politics and Political Ideas (3rd-9th Centuries). Beijing: Peking University Press. ISBN: 9787301348840.

- 192.Bloch, M. (2004). Feudal Society (Vols. 1 & 2) (Zhang Xushan, et al., Trans. & Rev.). Beijing: Commercial Press. ISBN: 9787100041843.

- 192.Febvre, L. (2014). Martin Luther: A Destiny (Wang Yonghuan & Xiao Huafeng, Trans.). Shanghai: Shanghai Sanlian Publishing House. pp. 129-130. ISBN 978-7-5426-4953-9.

- 194.Macfarlane, A. (2022). China, Japan, Europe and the Anglo-sphere: A Comparative Analysis (Xun Xiaoya, Trans.). Beijing: China Science and Technology Press. (Chapter 1 “Four Civilizations”, Section 2 “The Japanese Cultural Sphere”). ISBN: 9787504693778.

- 195a. Zuo, Q. M. (2012).Zuo Zhuan(Vol. 2) (p.974, “Chenggong Year 13”). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. ISBN: 9787101088335.

- 195b.Zuo Zhuan (Vol. 1) (p.219, “Zhuanggong Year 11”). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2012. ISBN: 9787101088335.

- 196.Song, Z. H. (Ed.). (2011). A History of the Shang Dynasty (11 Vols.): Vol. 4 The Shang State and Society (by Wang Y. X. & Xu Y. H.) (Chapter 2 “The Shang King as the Supreme Leader of the Aristocratic Ruling Class”; Chapter 3 “The Aristocratic Ruling Class of the Shang Dynasty”; Chapter 6 “The State of the Shang Dynasty”); Vol. 10 Geography and Vassal States of the Shang Dynasty (by Sun Y. B. & Lin H.) (Chapter 6 “Shang Dynasty Vassal States”, Section 2 “The Relationship Between the Shang Dynasty and Vassal States”). Beijing: China Social Sciences Press. ISBN 9787500489245.

- 197.Bu, X. Q. (Chief Compiler). (2016). A General History of China (5 Vols.). Hefei: Anhui Education Publishing House. (Reprinted 24). ISBN 978-7-5080-8666-8.

- 198a. “What has the emperor’s family affairs to do with outsiders?” Ouyang Xiu, comp. New Book of Tang · Juan 223 (Part 1) · Liezhuan 148 (Part 1) · “Traitors (Part 1)” · “Biography of Li Linfu”. Hancheng Network (Guoxue Baodian). https://guoxue.httpcn.com/html/book/CQPWKOKO/KOAZKOCQPW.

- 198b. “How dare I not obey orders concerning Your Excellency’s family affairs?” Book of Zhou · Juan 11 · Liezhuan 3 · “Biography of Yuwen Hu, Duke Dang of Jin”. Hancheng Network (Guoxue Baodian). https://guoxue.httpcn.com/html/book/CQRNTBXV/KOXVXVILRN.

- 199.Pang, G. Q. (2023). “From the Perspective of Legal Codification: The Transformation of the Byzantine Empire in the 7th-8th Centuries.” Historical Research, (01). (Retrieved from Official Account of the Chinese Academy of History on Tencent News, , 2023).

- 200.Chen, Z. Q. (1999). “A Study on the Characteristics of the Byzantine Imperial Succession System.” Social Sciences in China, No. 1, pp. 180-194. (Retrieved from National Social Science Database, CNKI).

- 201.Wang, S. Y. (2023). Governing the Empire: The Political System of the Ottoman Empire. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House. (Chapter 1 “Suleiman’s Legislation and the Institutional Construction of the Ottoman Empire”, Section 2 “’Suleiman’s Legislation’ in the Heyday of the Empire”). ISBN: 9787208181830. (This book is the final research achievement of the Key Project of the National Social Science Fund of China “Study on the Political System of the Ottoman Empire” (Project No.: 16ASS001)).

- 202.Jason Goodwin:《LORDS OF THE HORIZONS》Part I Curves and Arabesques.6.The Palace.Random House.2010,ISBN9788151115217.eBook.

- 203.Stuart Munro-Hay:《Aksum An African Civilization of Late Antiquity》VII The Monarchy 3.Dual Kingship,PP156-157,Edinburgh Univ Press,English,1991,ISBN:9780748601066.

- 204.Huntington, S. (1998). The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (Liu Junning, Trans.). Shanghai: Shanghai Sanlian Publishing House. ISBN: 7-5426-1143-7.

- 205.United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2024, March 13). 2023/24 Human Development Report: Wealthy Countries Set New HDI Records, While Half of Poor Nations Face Development Reversals. https://www.undp.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).