1. Introduction

Currently, particular attention is being paid to sustainable management of nitrogen in agroecosystems. Among the various management techniques, precision agriculture principles occupy a prominent place.

Precision agriculture utilizes innovative technologies to create best sustainable farming practices (BSFPs) and aims to integrate them with modern approaches to the goals and objectives of agriculture and ecology. Cultivation systems must adhere to fundamental principles that, taken as a whole, define the basic standards of sustainable development. Precision agriculture can improve soil management and crop rotation while maintaining soil quality and water availability to support long-term agricultural production. Furthermore, sustainable precision agriculture can protect, recycle, replace, and maintain the natural resource base, including soils, water, and biodiversity, contributing to the preservation of natural capital. A key principle of precision agriculture is the economically and environmentally sound use of mineral and organic fertilizers. The Industry 4.0 methodology largely aligns with these principles. The concept of the fourth industrial revolution (Industry 4.0) was first formulated in 2011 as the introduction of cyber-physical systems into factory processes [

1]. It is envisioned that these systems will be integrated into a single network, communicate with each other in real time, self-configure, and learn new behavior patterns. Such networks will be able to organize production with fewer errors, interact with manufactured goods, and, if necessary, adapt to new consumer needs. For example, during production, a product will automatically determine the equipment capable of producing it. It is envisioned that all of this will occur completely autonomously, without human intervention. The Industry 4.0 concept is based on four principles:

• interoperability between humans and machines, which enables direct communication via the internet;

• transparency of information and the ability of systems to create a virtual copy of the physical world;

• technical assistance from machines to humans to combine large volumes of data and perform a number of tasks that are unsafe for humans;

• the ability of systems to independently make decisions [

2]. Ultimately, the practical implementation of Industry 4.0 boils down to the creation of as many electronic twins of production processes [

3,

4] and related technologies as possible.

Currently, Russia already has several government decrees in specific areas of Industry 4.0, including the national strategy for the development of artificial intelligence through 2030, approved by Presidential Decree No. 490 of October 10, 2019. This decree defines the goals, key areas, and mechanisms for the development of artificial intelligence, as does the federal project on artificial intelligence, approved on August 27, 2020, by the Presidium of the Government Commission on the Use of Information Technology to Improve the Quality of Life and Business Environment. This project is aimed at implementing this strategy and, accordingly, the concept for the development of regulation of relations in the field of artificial intelligence and robotics technologies, which was approved by Russian Government Order No. 2129-r of August 19.

The global population is growing, and with it, global demand for agricultural products. Farmers face increasing pressure to improve productivity per hectare across countries. This situation is exacerbated by climate fluctuations and stricter regulations, such as those on pesticides and fertilizers. Digital technologies can support farmers and facilitate their work by optimizing operational procedures and resource use or meeting demands for greater transparency in the agricultural value chain. The development of digital technologies means that agribusinesses can more accurately monitor livestock production, manage arable land, and manage production overall. This has become possible thanks to innovations in modern systems that create digital twins of agricultural processes. These include technologies such as sensor technology, digital positioning, visual detection systems, and data visualization. Structural transformation in agriculture also requires the adoption of digital technologies, which are more attractive because the potential savings or productivity gains are greater for larger enterprises. Overall, this will reduce inefficiencies in a number of production links, improve stages of the complex agricultural value chain as a whole, and eliminate negative externalities such as environmental and food pollution, as well as food and environmental security issues. Such technologies will enable the development of precision agriculture.

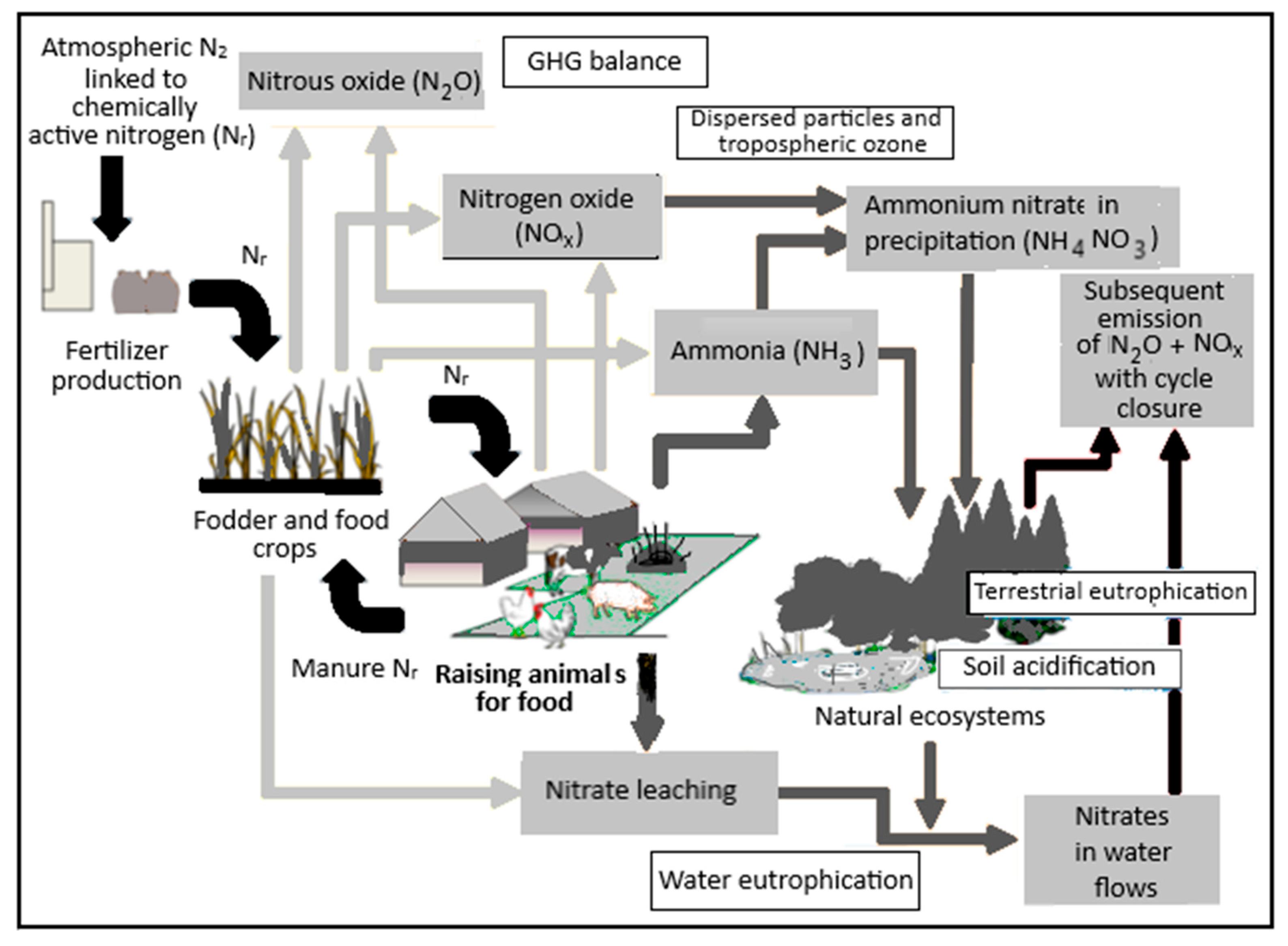

The main environmental risks associated with agriculture include the risks of using nitrogen fertilizers. Nitrogen is the main nutrient that forms the yield of all agricultural crops. The use of nitrogen mineral fertilizers is a factor determining food security in all regions of the Earth. However, nitrogen has a pronounced polyfunctionality, being both a biophilic element and a pollutant element [

5]. This is due to the fact that nitrogen is an important, but usually deficient nutrient for biological systems. However, the massive use of industrial nitrogen fertilizers has doubled the N fluxes in the global biogeochemical cycle, transforming it into an agrogeochemical cycle with many ecological consequences (

Figure 1).

The objective of this study is to develop nitrogen management techniques in agroecosystems using Industry 4.0 approaches. The following research objectives can be identified:

• Efficiency of nitrogen use from mineral and organic fertilizers in agroecosystems;

• Forecasting plant nitrogen requirements;

• Modern methods for biologizing the nitrogen cycle;

• Computational platforms for studying complex N interactions in crop production systems;

• Precision farming as a method for managing the risks of nitrogen fertilizer application.

• Lifecycle management of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers.

It is also necessary to create electronic counterparts, preferably for all technological processes, to inform farmers about the agronomic, agrochemical, and environmental optimization of fertilizers used, primarily nitrogen, in precision farming systems.

2. Nitrogen Use Efficiency of Mineral and Organic Fertilizers in Agroecosystems

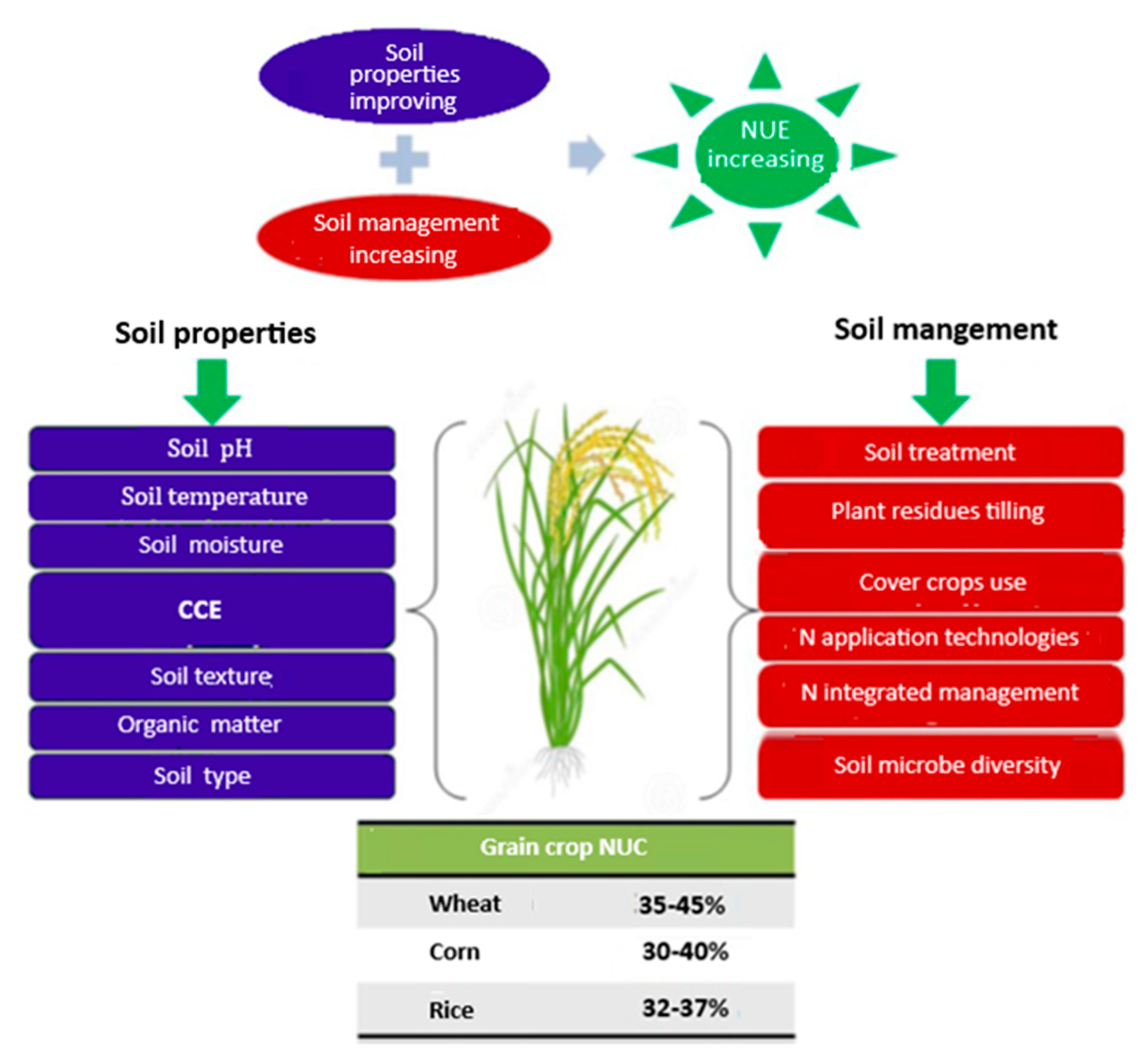

Nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) can be considered an environmental impact indicator, assessing the potential environmental risk of a given agroecosystem [

7]. This value is defined as the ratio of the amount of nitrogen entering an agroecosystem (farm, landscape, river basin, administrative region) to the amount of nitrogen in the resulting products at the system's output:

Figure 2 shows the basic scheme for estimating NUE values. Currently, the global average NUE values are no more than 40%, being somewhat higher in countries with sustainable development of agroecosystems (Western Europe, North America), and significantly lower in countries relying mainly on intensive application of nitrogen fertilizers (South and Southeast Asia). Low NUE values are accompanied by excessive accumulation of reactive nitrogen compounds (N

r in

Figure 1) in soils, natural waters, the atmosphere and food products [

8,

9]. Our experimental production data indicate a change in NUE values from 15 to 80%, and the maximum utilization of nitrogen by cabbage under production conditions was achieved with the application of the optimal nitrogen dose (fertilizer dose of 200 kg/ha and nitrogen-mineralizing capacity, NMC, of 390 kg/ha). This also corresponded to the maximum yield (120.5 t/ha). Taking into account the aftereffects of applied fertilizers, the doses of newly applied nitrogen can be significantly lower (from 50 to 125 kg/ha), which will correspond to total NUE values of 34 to 48% (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

If we consider the NUE values at the landscape level, i.e. taking into account the complete biogeochemical nitrogen cycle (see

Figure 1), these values will vary from negative values at low rates of applied mineral fertilizers from -0.5-20% to +55-60% for agricultural landscapes in intensive farming zones in the central zone of European Russia [

5].

Organizing the efficient use of manure as a fertilizer containing nitrogen in mineral and organic form is a major environmental problem in livestock farming, particularly in the Leningrad Region, Russia, with manure nitrogen considered the main source of pollution. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the initial data for making comprehensive decisions on animal and poultry manure management, and to create a centralized management system to reduce nitrogen losses and mitigate environmental risks. Nitrogen use efficiency values calculated at the regional and municipal level can be used as indicators. At the regional level, NUE values were 34%, and the nitrogen surplus was 103 kg N/ha/year. In eleven municipal districts, the average NUE value was 59%, and the average nitrogen surplus was 40 kg N/ha/year. Four districts were identified as "hot spots" with NUE values ranging from 1 to 37% and nitrogen surpluses ranging from 87 to 3082 kg N/ha/year. A scenario for the redistribution of organic fertilizers between the "hot spots" and "ecologically clean" districts is proposed [

10].

Due to the relatively low NUE values for different agricultural systems, further N losses occur along biogeochemical (agrogeochemical) chains before it is consumed. Increasing NUE is one of four key areas of action identified to reduce N losses to the environment: The other three are shifting either (2) toward dietary trends—increasing consumption of plant foods in high-income countries; (3) toward reducing food loss and waste; and/or (4) reducing biofuel production from food products.

Among the relevant approaches for managing agrogeochemical nitrogen flows discussed in the current scientific literature using promising research and development (R&D) areas for addressing these issues, four broad areas can be distinguished: soil nitrogen cycling, systems agronomy, biological nitrogen fixation (BNF), and plant breeding (genetics). All of these areas fit within the precision agriculture paradigm and align with the principles of Industry 4.0. Their application in agriculture in general, and especially in the form of electronic twins of process operations, for managing nitrogen flows, as well as phosphorus and other fertilizer elements, in agroecosystems is highly relevant.

2.1. Predicting Crop Nitrogen Needs

Nitrogen is used most efficiently when its availability in the soil is synchronized with plant uptake. This synchronization is a complex technological challenge, especially for annual crops typical of most high-yield agricultural systems. For example, many cereal crops have a growing season of 90-100 days, but they take up N and accumulate biomass at a significant rate only during a specific period (30-40 days in mid-season). In particular, in corn crops, N uptake rates reach 5 kg/ha per day for 3-4 weeks and can decline rapidly. Meanwhile, nitrogen mineralization in the soil occurs throughout the growing season when soils are not too dry or too cold to support biological activity. This asynchrony between when nitrogen is available and when it is needed creates the potential for N loss and is the primary cause of low NUE in most agronomic systems. Depending on the crop rotation system and the environment, achieving synchrony can be challenging due to variable weather, equipment delivery times, labor availability, and other constraints and sources of uncertainty. First, plant nitrogen requirements are difficult to predict based on the data available at the time of fertilization decisions and possible future weather scenarios. Nitrogen requirements can also vary greatly depending on landscape complexity within a given year and even from year to year in the same location. Second, estimating N flux rates through the soil agrogeochemical cycle is difficult, especially in temperate climates. In these regions, nitrogen inputs from soil organic matter mineralization and its removal through denitrification and leaching into groundwater vary greatly from year to year and from field to field. Addressing these issues, which are inherent to different cropping systems, remains challenging.

Assessing the Nitrogen-Mineralizing Capacity of Soils in Agroecosystems

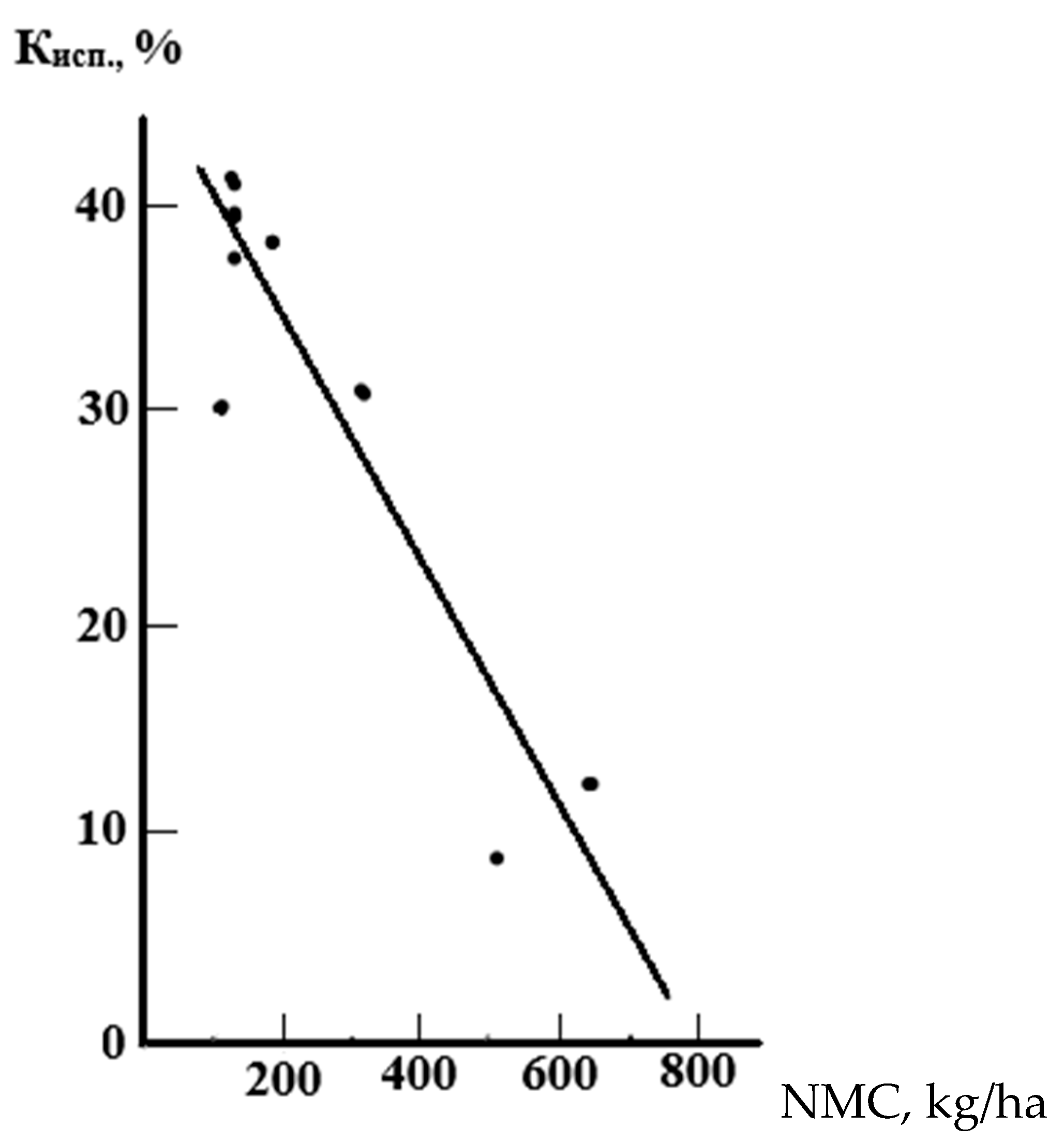

One way to address these issues is to determine the nitrogen-mineralizing capacity of soils (NMC). NMC values include a summary assessment of nitrogen transformation in the soil under the influence of fertilizer rates, hydrothermal parameters (temperature, precipitation), agrochemical soil parameters, microbiological activity, etc. NMC is the amount of organic nitrogen in the soil capable of mineralization during the projected growing season. These values include nitrogen absorbed by plants, re-immobilized by microorganisms, lost through leaching and denitrification, and remaining in an available form after the end of the growing season. A quantitative assessment of soil NMC, which is a key criterion for the development of the agrogeochemical nitrogen cycle, can be performed using a method for determining the mineralizable soil nitrogen equivalent to the availability of fertilizer nitrogen. This method is performed by composting soil samples with increasing doses of nitrogen fertilizers. Soil samples are composted under optimal temperature (18-28°C) and moisture (60% FWHC) conditions for 4 weeks with a series of 4-6 doses of nitrogen fertilizers equivalent to those planned for various agricultural crops. The NMC value itself is determined by finding the first derivative of a quadratic regression equation describing the accumulation of available nitrogen (nitrates and exchangeable ammonium) in the soil depending on the applied nitrogen fertilizer doses. In long-term experiments with 15N-labeled nitrogen fertilizers conducted under various soil, climatic, and environmental conditions, it was found that NMC (x) values had a significant inverse correlation with NFU values or NUE values (y):

y = 43.4 – 0.0550 x, r = - 0.928, P0.01

A similar correlation was observed for the total amount of nitrogen available to plants (total N-(NO3- + NH4 +exch) and NMC):

y = 44.5 – 0.0449 x, r = - 0.942, P0.01.

NMC values generally account for more than 70–75% of the total nitrogen available to plants during the growing season, i.e., they are decisive. Their assessment allows us to diagnose the nitrogen regime of soils and the possibility of using nitrogen fertilizers, since, as shown, the coefficients of use of these fertilizers are closely related to the values of NMC of soils: they increase with a decrease in the amount of soil mineralizable nitrogen and decrease with its increase (

Figure 3).

Therefore, from an agrogeochemical perspective, determining the nitrogen-mineralizing capacity of soils allows for a sufficiently accurate determination of the nitrogen available to plants during the upcoming growing season and forecasting the need for nitrogen fertilizers for the planned yield of crops. In turn, optimal use of nitrogen fertilizers helps reduce the negative consequences of their irrational application.

Thus, the nitrogen-mineralizing capacity of soils is a comprehensive quantitative indicator for characterizing the main processes of the agrogeochemical nitrogen cycle (immobilization ↔ mobilization) and assessing the impact of nitrogen fertilizers on these processes. Determining this value allows for the prediction and modeling of various aspects of nitrogen transformation in the soil, assessing the accumulation and dynamics of mobile mineral nitrogen compounds in the soil, and nitrogen conversion in systems such as soil-fertilizer-plant and soil-water. The efficiency of using both fertilizer nitrogen and soil nitrogen is also increased.

Relevant databases have been created for various soil and climate regions, allowing them to be included in models for assessing nitrogen requirements for the planned growing season [

11,

12]. This makes it possible to create electronic counterparts of agrochemical technologies for determining nitrogen doses.

2.2. Current Challenges in Biologization of the Nitrogen Cycle

In recent years, advances in molecular biology and modern genome editing tools have the potential to biologize the nitrogen cycle by developing varieties with improved NUE, although further research is needed to achieve these goals. The integration of all these approaches will lead to sustainable crop production through the effective management of environmental stresses under the current climate change scenario. Furthermore, plant epigenetics, which is a conserved mechanism for regulating gene expression that includes histone modification, DNA methylation, non-coding RNA, and chromatin remodeling, can be considered a new and effective tool for increasing NUE in agroecosystems [

13].

Thus, the concept of nitrogen-fixing wheat is a noble aspiration that would revolutionize grain crop cultivation, but its practical implementation is costly. Despite decades of research, the processes associated with both phytobacterial symbiosis and the nitrogen fixation process itself are still relatively poorly understood. Basic research already provides insight into potential mechanisms for overcoming the challenges associated with both the creation of artificial symbioses and genetic modification approaches for biological nitrogen fixation. However, a significant gap still exists between current progress in developing model systems and the actual implementation of these systems in wheat plants [

14,

15].

It is also unknown to what extent the proposed methods will improve wheat yield. Studies with transgenic

E. coli species have demonstrated very low nitrogenase activity, approximately 10% of that of native

Paenibacillus sp. WLY78. This is insufficient to ensure full diazotrophic growth, but it can still be used as a means of reducing the amount of nitrogen required from other sources (such as traditional fertilizers). Nevertheless, the potential end result justifies the means. At this stage of biotechnology development, some progress in the development of nitrogen-fixing wheat can be expected. Whether it is possible to grow crops that survive solely by using N

2 from the air as a nitrogen source or whether this results in only a modest increase in wheat yield, the need to improve global food production requires such research [

16].

Also important is research aimed at assessing the associations of nitrogen-fixing bacteria in combination with nitrogen from mineral fertilizers in rice cultivation [

17]. Klebsiella pneumonia and

Azospirillum brasilense were applied, and urea was used as a fertilizer at rates of 0, 25, 50, and 75 kg/ha. The results revealed that inoculation of upland rice with nitrogen-fixing bacteria can increase the formation of shoots, stems, and dried root weight, as well as total plant biomass. The effect of

A. brasilense on increasing tillering, dry mass of biomass (shoots and roots), and total nitrogen uptake showed a tendency to increase compared to

K. pneumonia. Differences in nitrogen fertilizers had no significant impact on any measured parameters, with the exception of plant nitrogen content. The interaction of bacteria and nitrogen fertilizers also had virtually no effect on any measured parameters.

When assessing the potential importance of techniques aimed at biologizing the nitrogen cycle in growing staple grain crops in agroecosystems, it should be emphasized that bringing this research to Industry 4.0 technologies will require significant effort and is more likely a medium- to long-term prospect.

A more realistic option is the use of biofertilizers, such as specialized bio- and nano-fertilizers, which could represent a breakthrough in increasing nitrogen use efficiency and reducing nitrogen pollution. These technologies have already been developed, making it possible to use these techniques when applying nitrogen to agricultural crops [

18].

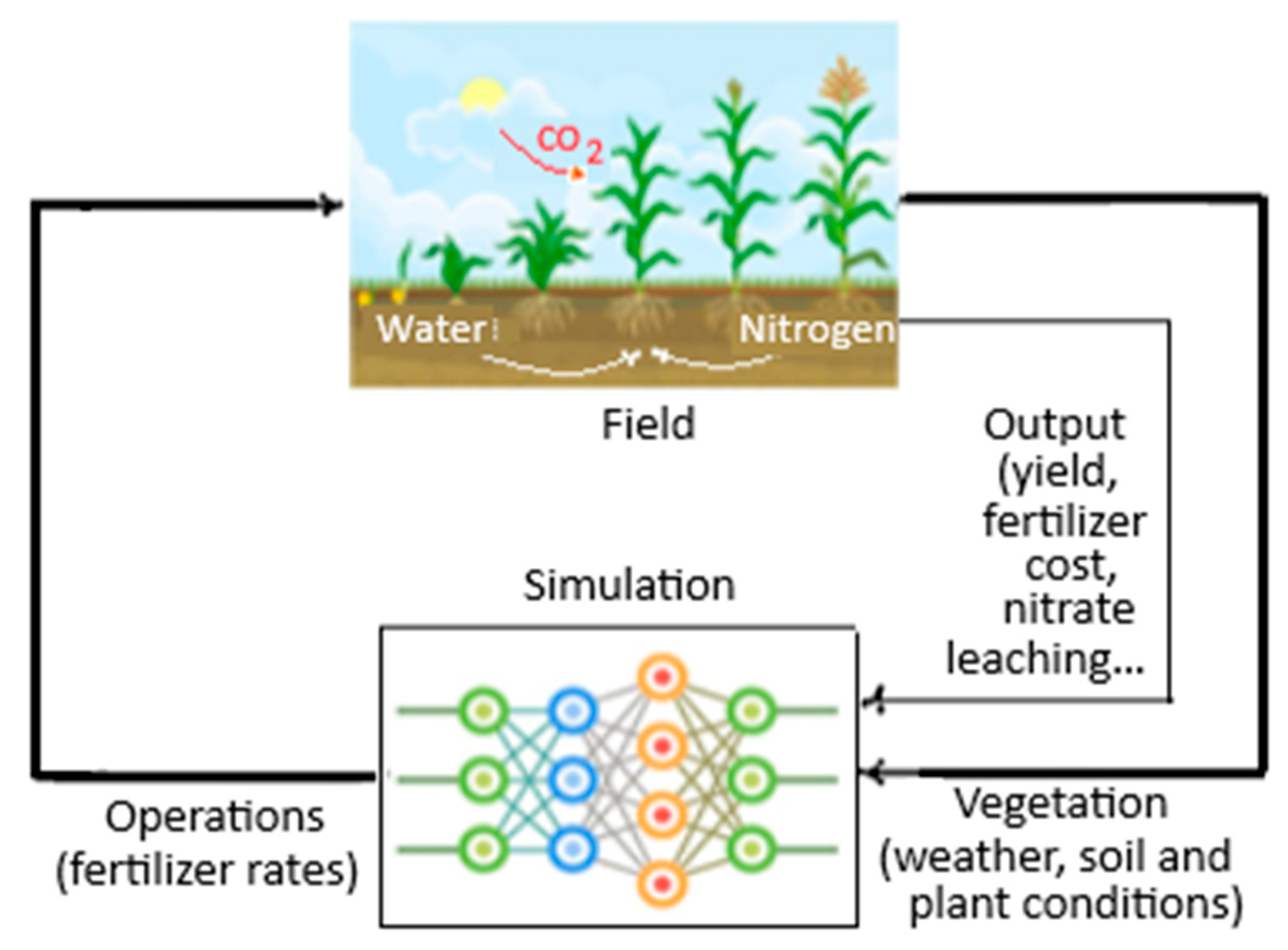

3. Computational Platforms for Studying Complex N Interactions in Crop Production Systems

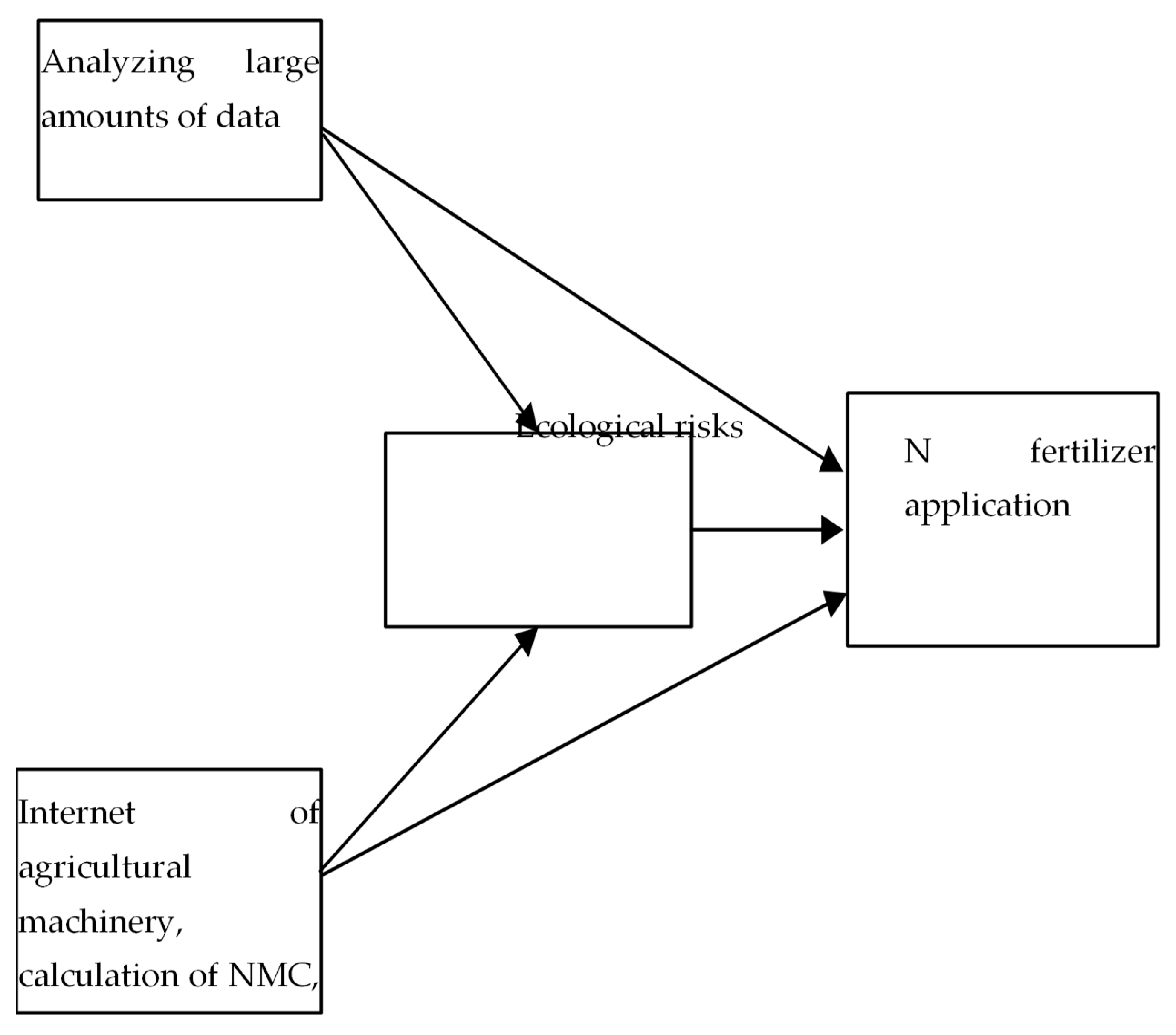

Computer models can serve as tools for on-farm management decisions, helping to improve nitrogen use efficiency for livestock, predict and protect water quality, and promote the use of best sustainable farming practices (BSFPs) in crop production. Predictive models can help identify vulnerabilities related to nitrogen and greenhouse gas emissions. Crop and livestock producers are increasingly required to develop nutrient management plans to demonstrate that their operations have sufficient crop acreage, seasonal land availability, manure storage capacity, and fertilizer application equipment. Commercial fertilizers and other nutrient inputs used in fields must be managed in both an economically and environmentally responsible manner. Computer software has been and will be used to develop these plans. New software for nutrient management planning must increasingly account for the temporal and spatial nature of nutrient management, accommodate regional conditions and changing regulatory reporting requirements, utilize national databases and standards, and take advantage of modern software technologies, including those based on Industry 4.0 principles. A general scheme of modern modeling approaches incorporating elements of artificial intelligence are shown in

Figure 4.

Potential scenarios for cropping systems, nitrogen, and/or water management should essentially be developed in collaboration with local producers, commodity groups, and advocacy organizations. However, when comparing model results from different management scenarios, the uncertainty of the results obtained from calibration and validation studies should be considered.

When selecting management scenarios, including environmental risks, even greater potential differences must be considered. Significant progress has been made in developing computer modeling tools, for example, for characterizing N2O gas emissions. Currently, modeling is primarily used to study how N2O emissions are related to changes in land management, soil structure, and precipitation, as well as to describe how annual N2O emissions can be reliably modeled for some local and managed systems. Reducing nitrogen gas losses from soils relies heavily on land management, but generalizations based solely on nitrogen inputs from soil and water are limited by the need to consider important factors such as soil structure, soil organic matter content, and the timing of agronomic and agrochemical interventions. Low nitrogen gas emissions from natural soils, intermediate emissions from dryland agriculture, and high emissions from irrigated agricultural lands were modeled. Seasonal patterns of nitrogen gas emissions and differences in mean emissions were modeled for various cropping systems: pasture grasses, winter wheat rotations with conventional fallow and no-till, winter wheat/corn/no-till fallow, and irrigated corn and silage production. Water use, tillage, seeding/fallowing timing, and fertilization all impact nitrogen gas emission reduction, further complicating land use information. NUE values in production agriculture are often low, resulting in excessive losses of excess nitrogen to groundwater as NO3–, gaseous emissions of NH3 and N2O, as well as surface runoff and erosion. Field studies exploring potential BSFPs practices are labor-intensive and expensive and cannot cover all scenarios.

The use of simulation models with N recycling components, coupled with appropriate field studies, offers a methodology that can help identify on-farm best sustainable practices that can improve nitrogen use efficiency, but at a lower cost. Credible BSFPs research using modeling tools must follow a clearly defined path, including model selection and applicability, adaptation and calibration, sensitivity analysis, data requirements and availability, and interpretation of results and model limitations.

An important part of these BSFPs modeling studies is early and ongoing engagement with local producers and farm-specific field research programs to create digital twins of these technologies.

4. Precision Farming as a Nitrogen Fertilizer Risk Management Technique

Diffuse pollution caused by fertilizer use in agriculture has become a difficult-to-solve global problem. A systematic review of published papers examines the relationships between nitrogen fertilizer use efficiency, NUE, point and diffuse pollution, and farmer policies and management practices. Low NUE (approximately 40% globally) means that approximately 60% of nitrogen is a potential source of environmental pollution. Numerous studies demonstrate a direct relationship between nitrogen fertilizer application in agriculture and diffuse pollution resulting from evaporation, leaching, and runoff. Improving NUE is key to reducing the environmental risks of such pollution. There is also a wealth of literature describing, developing, and demonstrating the effectiveness of methods and procedures that help improve NUE and reduce its negative impacts at both the local and global levels [

7,

8]. To some extent, they have already been incorporated into legislation in some countries (primarily in the European Union). However, these standards have not been generally accepted by farmers, and they are reluctant to implement them in practice. Existing research in this area attributes this behavior to a lack of awareness, which predetermines their reluctance to change agronomic and agrochemical production management practices. Some studies report a defensive attitude among farmers, caused by a lack of information about the reality and scale of the problem caused by nitrogen fertilizer application. Demonstrating the environmental problems associated with current levels of diffuse nitrogen pollution allows for a better understanding of the factors influencing farmer behavior. This approach will enable the development of more effective policies for the widespread implementation of better nitrogen management systems and, ultimately, will lead to a reduction in diffuse nitrogen pollution by improving NUE.

This will also reduce the likelihood of the associated environmental risks (

Figure 5).

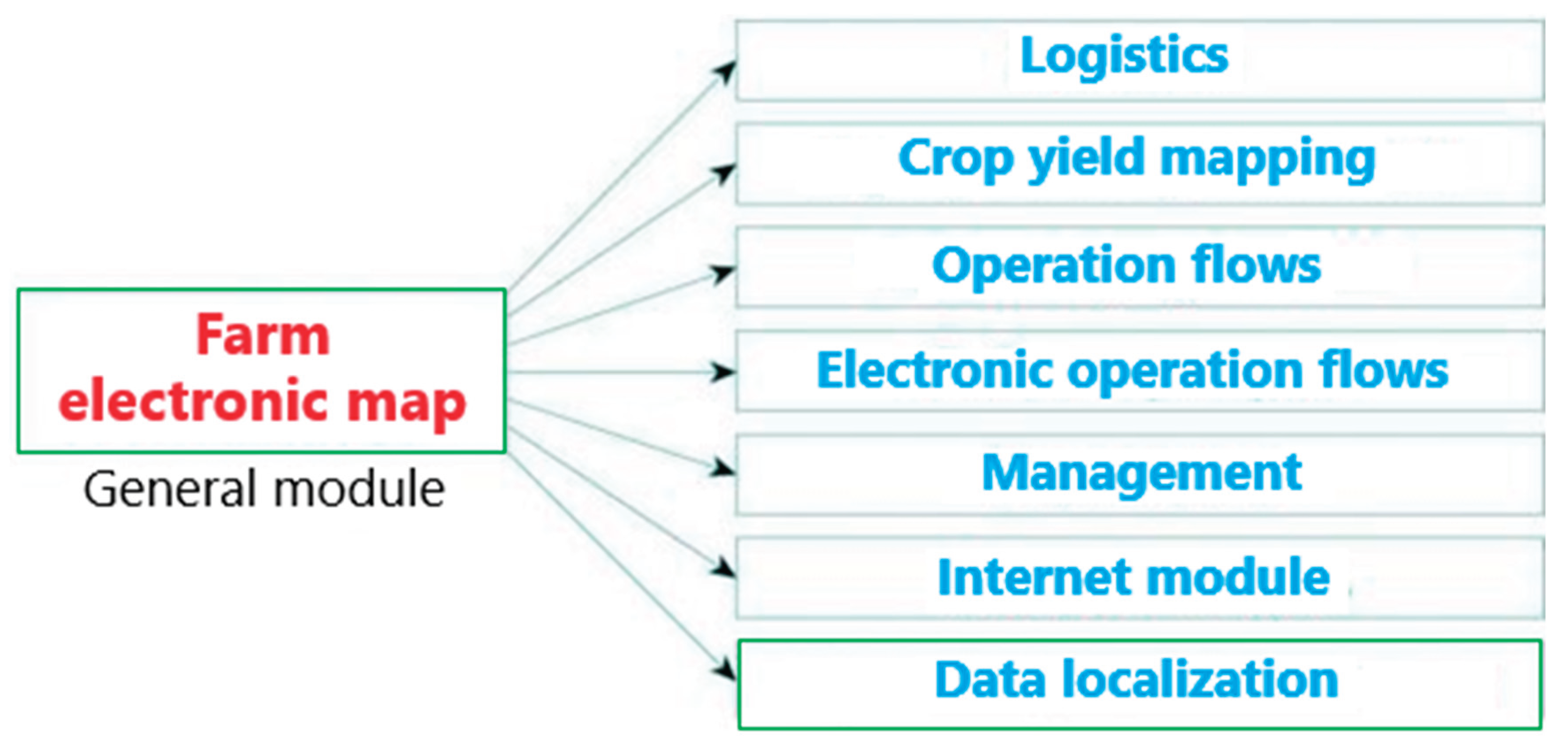

A key element in managing the environmental risks of nitrogen application in agroecosystems is the implementation of precision agriculture technologies. It should be noted that precision agriculture represents a combination of various Industry 4.0 advances. These multiple combinations are typically interconnected and require continuous improvement. Let's consider the combination of various technologies that enable the creation of their electronic counterparts:

• The Global Positioning System (GPS), which comprises a set of 24 satellites located around the Earth's circumference, whose signals can be processed by a ground-based receiver to determine geographic location. The probability that this situation on the ground will be within 10-15 meters of the actual position is 95%. GPS allows for precise mapping of farm locations and, along with appropriate programming, informs the owner about the condition of the crops being grown and the need for agronomic and agrochemical interventions;

• Geographic Information System (GIS), which is software that imports, exports, and manages spatiotemporal geographic information, allowing for the exploration of various farm management options by viewing layers of information and their corresponding technological practices;

• Grid sampling, corresponding to the division of the field into matrices of approximately 0.5-5 hectares. Soil sampling within the grid cells helps determine optimal fertilizer application rates. Multiple samples are collected from each cell, mixed, and sent to a research laboratory for analysis;

• Variable Rate Technology (VRT), which includes modern field equipment with an optional electronic control unit (ECU) and installed GPS, can meet the requirements for variable nitrogen fertilizer application rates and/or irrigation rates. Sprinklers and a rotating disc unit with an ECU and GPS have been successfully used for regular irrigation. When mapping the required nutrients for VRT, it is important to consider not only the rate of fertilizer application that increases yield, but also the rate of fertilizer application that increases agronomic and environmental efficiency;

• Yield maps, which are created by processing information from a GPS-equipped adjustable combine header, for example, in conjunction with a yield recording system. A yield map records the movement of grain through the header while simultaneously storing the actual location in the field;

• Remote sensors, which generally represent classes of aerial or satellite sensors. They can display differences in field shades according to changes in soil type and crop levels, field boundaries, windbreaks, irrigation canals, etc. Aerial and satellite images can be used to create electronic maps reflecting plant health;

• Direct sensors, which are used to quantify soil parameters, such as nitrogen content and soil pH, and crop parameters, as a tractor with a sensor moves across the field;

• Computer hardware and software for verifying information integrated with other innovative precision agriculture components and available in user-friendly formats such as maps, charts, sketches, or reports;

• Precision irrigation techniques have recently been refined for commercial use in sprinkler irrigation systems, allowing for the control of irrigation machines using GPS-based controllers. Remote control systems and sensors are being developed to monitor soil and plant conditions, including water and nitrogen index, and environmental conditions, as well as irrigation boundaries [

19].

One of the main advantages of precision agriculture is the ability to significantly reduce the application rates of nitrogen, phosphorus, and other fertilizers, as well as the application rates of herbicides, manure, and seeds. Using sensors and software that focus on economically and environmentally optimal yields, farmers can gain insight into how much nitrogen to apply through mineral and organic fertilizers within BSFPs, and this data can also support them in the long term [

6,

20].

Differences in plant and soil data can also be used to define field contour management zones using a combination of sensing, geostatistics, and interpolation methods. However, when developing site-specific recommendations for precision agriculture, the dynamic nature of soil nitrogen and the efficiency of its uptake by crops across different landscapes must also be taken into account. Furthermore, recommendations based on indicators during the growing season cannot guide pre-planting decisions.

Furthermore, an integrative site-specific approach to nitrogen management links georeferenced decision support models with dynamic biogeochemical models that simulate outcomes based on relevant crop, soil, weather, and management factors. Models simulating N conditions (e.g., DBs based on NMS values) can then be validated using field measurements collected during the growing season.

Thus, precision farming technologies are compatible within the framework of an adaptive N management system, which uses specific empirical data for specific field- or contour-level areas to improve model accuracy.

Let's look at specific fertilizer management techniques using nitrogen as an example. Computer modelling and decision support models for soil-crop systems that focus on the nitrogen cycle, particularly when combined with economic and geographic information systems (GIS), are viable alternatives that can facilitate the evaluation of different combinations of management scenarios and how they affect the nitrogen use efficiency of a cropping system (for ex., wheat, corn or rice) for a given set of conditions. These models are a complex series of algorithms and databases that can interact with different conditions and serve as mechanical tools for evaluating different scenarios and their impact on the efficiency of nutrient use, particularly nitrogen (nitrogen use efficiency, NUE), and the sustainability of the system (

Figure 6).

Ultimately, data from these various sources can be combined using machine learning or other methods to provide the necessary assessments and automated recommendations using Industry 4.0 technologies.

Crop sensing data and geo-referenced management data can be used to calculate and display NUE values in space and time (

Figure 7).

Precision agriculture is an approach to farm management that aims to identify methods that optimize the use of resources, in this case, nitrogen fertilizers. Precision agriculture does not focus exclusively on nitrogen management, but improving its use efficiency is also included, as is managing environmental risks. Management at the site-specific level can improve NUE, increase profits, and/or minimize the risk of unproductive losses.

The better plants utilize nitrogen from fertilizer and the more actively the uptake amount is absorbed, the higher its agrochemical efficiency or the return on investment of nitrogen fertilizer through increased yield of the main product. An example of the use of precision agriculture technologies in Northwest Russia [

21] is available. Fertilizers and other resources were similar to those used in high-intensity farming, but nitrogen (ammonium nitrate) and potassium (potassium chloride) fertilizers were applied differentially, taking into account the heterogeneous nitrogen and potassium contents in the soil, using precision application methods. Mineral fertilizers were applied as follows. In the control variant (high-intensity technology), fertilizers were distributed uniformly across the entire field. In the experimental variants (precision farming technology), fertilizers were differentiated based on the nutrient content of the soil (initial data). Fertilizer was applied using an Amazon ZA-M 1500 solid fertilizer spreader with an onboard computer and GPS. Variations were also implemented using improved precision farming technologies, which were implemented through more informative and differentiated nitrogen application based on the optical properties of wheat leaves.

The return on investment for increasing yield per kilogram of fertilizer nutrients depends on the dose, timing of application, and crop type. Differential application of fertilizers increases the return on investment of 1 kg of nitrogen fertilizer while increasing grain yield in both studied varieties (from 27.7% to 210% for the Ester variety and from 43.5% to 250% for the Krasnoufimsky-100 variety).

5. Fertilizer Lifecycle Management

Product lifecycle management (PLCM) is an integrated information system approach with the ultimate goal of creating competitive products that outperform in various aspects, such as profitability, customer satisfaction, speed to market, and environmental performance. An PLC system is based on data from all stages of a product's lifecycle, from concept development to processing. Thus, PLC includes the management of product, process, and engineering data at the production, supply chain, and marketing levels. Applying PLC approaches promotes sustainable innovation through optimized product and process design, improved forecasting capabilities, enhanced market understanding, prototyping performance, and more. Importantly, it also includes monitoring emissions, waste, resource consumption, and recycling. PLCM is a direct function of the Industry 4.0 transformation, given the significant increase in the production of more complex products with shorter lifecycles. Consider, as an example, a life cycle assessment (LCA) framework for assessing the environmental risks of eutrophication of surface water ecosystems due to the application of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers in agroecosystems. Intensive application of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers to agricultural lands for crop nutrition has led to eutrophication, nutrient enrichment of water bodies, accompanied by excessive algal growth, deoxygenation, and loss of aquatic biodiversity. Life cycle assessment of fertilizers is often used to determine the environmental impacts of fertilizers. However, the lack of suitable methodologies for assessing the distribution and transfer of nutrients from soils hinders comparisons, especially at the regional level. Using a recently developed spatially-based nutrient distribution and transfer model (fate factor, FF), the LCA framework assessed the global spatial variability of nutrient losses due to crop fertilizer application and their relative impacts on aquatic biodiversity, in particular species richness [

22]. FF metrics assess the fate of N and P and their transfer from soils (croplands, pastures, and wildlands) to freshwater environments. Results indicate significant variability in inputs, loads, and impacts due to differences in nutrient distribution, transport, and impacts within local environmental contexts. This variability is reflected in significant differences between the widely used nutrient use efficiency indicator and the ultimate impacts of specific crops on water bodies. High-yielding crops (corn, rice, wheat, sugarcane, and soybeans) with the highest fertilizer inputs did not necessarily have the greatest impacts on water bodies. Variability in ranks was found across the assessment stages (fertilizer application, crop production, and impacts on water bodies), particularly for wheat and sugarcane. High global spatial variability in impacts on aquatic biodiversity is demonstrated, with significant biodiversity loss occurring outside regions with the highest production volumes. This suggests that global biodiversity impacts depend on local conditions beyond the field (e.g., the fate and transport of nutrients to the receptor environment, as well as the vulnerability of the receptor environment). When making decisions about strategic fertilizer pollution control and identifying sustainable crop suppliers, the impacts on water resources resulting from fertilizer use for specific crops should be considered. The development of improved FFs should be used to support spatially-specific and site-specific studies of nutrient migration from soils.

Although life cycle assessment is still difficult at the current level of development of modeling approaches for creating digital twins of fertilizer application technologies, in the medium and long term, this will be a mandatory component of Industry 4.0 applications in agriculture in general and nitrogen use in particular.

6. Conclusion

New, innovative developments in nitrogen management in agroecosystems in the era of Industry 4.0, combined with the principles of Industry 4.0 ideology, offer the opportunity to address progress, opportunities, and challenges in agricultural farming and address a number of pressing issues.

First and foremost, this is due to the fact that nitrogen is an essential, yet typically scarce, nutrient for biological systems. However, the widespread use of industrial nitrogen fertilizers has doubled N fluxes in the global biogeochemical cycle, transforming it into an agrogeochemical cycle with numerous environmental consequences.

Accordingly, this review of current achievements and challenges related to nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) in agriculture has identified areas of potential and necessary research in the field of nitrogen agrogeochemistry, its cycling in agroecosystems, and precision farming as a key agronomic practice for achieving sustainable nitrogen use in agriculture. It has been demonstrated that quantitative assessments of NUE, as an environmental indicator, can help farmers reduce the risk of N losses on farms or in fields. This can also be useful for regional or supply chain assessments. As an example, split-application technology can significantly reduce nitrogen losses.

Furthermore, assessing the nitrogen-mineralizing capacity of soils is another important technological indicator of Industry 4.0. This enables the quantitative assessment of crop nitrogen requirements during the growing season.

Existing decision support tools examine all aspects of N at the soil-crop interface – from gene expression, crop physiology, and phenology to soil processes and behavior prediction. Precision agriculture, based on the use of digital twins of agronomic and agrochemical processes, is a key technological element of Industry 4.0.

The approaches discussed require the use of large data sets. Next-generation computational platforms can help study complex N interactions in crop production systems to inform scientists, farmers, and management, determine research priorities, and improve understanding of emerging complexities. These computational frameworks include statistical models, process-based mechanistic modeling models, and hybrids of these.

Thus, the implementation of Industry 4.0 technologies will increase the efficiency of nitrogen management in agroecosystems. This aligns with precision agriculture techniques as a combination of best practices for its sustainable development. Such practices can only be implemented using digital twins of existing agronomic and agrochemical technologies, enabling economic and environmental optimization of nitrogen use in agriculture.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Fernandes, J. , Reis J., Melгo N., Teixeira L. and Amorim M. The role of industry 4.0 and BPMN [business process model and notation] in the arise of condition-based and predictive maintenance: A case study in the automotive industry // Applied Sciences, 2021, 11(8):3438.

- Yumaev E., A. Innovation and industrial policy in the light of the transition to Industry 4.0: foreign trends and challenges for Russia // Journal of Economic Theory. 2017. No. 2, pp. .181-185.

- Arno, O.B. , Arabsky A.K., Bashkin V.N. Innovative development of Gazprom Dobycha Yamburg LLC. Similarities and differences in methods of preventing potential disasters // Gas Industry. 2021. Spec. Issue 1 (184). pp. 26-34.

- Bhagat P. R., Naz F., Magda R. Role of Industry 4.0 Technologies in enhancing sustainable firm performance and green practices // Acta Polytechnica Hungarica. 2022 Vol. 19, No. 8, 229-247.

- Bashkin, V.N. Industry 4.0: risk management of nitrogen fertilizers application. Issues of risk analysis. 2024. Vol. 21. No. 4. pp. 68-81. [CrossRef]

- The European Nitrogen Assessment (Sutton M.A., Ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011, 664 p.

- Udvardi, M. , Below F.E., Castellano M.J., Eagle A.J., Giller K.E., Ladha J.K., Liu X., Maaz T.M., Nova-Franco B., Raghuram N., Robertson G.P., Roy S., Saha M., Schmidt S., Tegeder M., York L.M. and Peters J.W. A Research Road Map for Responsible Use of Agricultural Nitrogen // Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021. V. 5:660155. [CrossRef]

- Rudoy, E.V. , Petukhova M.S., Ryumkin S.V., Truflyak E.V., Kurchenko N.Y. A scientifically based forecast of the development of precision agriculture in Russia. Novosibirsk: IC NGAU "Golden Ear", 2021. 138 p.

- Bashkin V.N., Alekseev A.O. Global food security and fundamental role of fertilizer. Part 1. Global food security and fertilizer production // Issues of Risk Analysis. 2022;19(3):60-73. [CrossRef]

- Bruhanov, А.Yu. , Vasiljev E.V., Kozlova N.P., Shalavina Е.V. Nitrogen and purposes of agriculture sustainable development // AgroEcoEngineering. 2022. No 2(111). p. 3-13.

- Bashkin V., N. Increasing the efficiency of nitrogen use: assessing the nitrogen-mineralizing capability of soils // Russian Agricultural Sciences, 2022, Vol. 48, No. 4, pp. 283–289. [CrossRef]

- Bashkin V., N. Estimation of nitrogen mineralizing capacity in different soil-ecological regions // Natural resources use and protection in Russia, 2022, No 3, pp. 117-122.

- Mahboob W., Guozheng Yang, Muhammad Irfan. Crop nitrogen (N) utilization mechanism and strategies to improve N use efficiency // Acta Physiologiae Plantarum, 2023, V. 45:52. [CrossRef]

- Bashkin V., N. Modern problems of agriculture biologization // Life of the Earth. 2022, V. 44, No 2. p. 180–191. [CrossRef]

- Javed T, I I, Singhal RK, Shabbir R, Shah AN, Kumar P, Jinger D, Dharmappa PM, Shad MA, Saha D, Anuragi H, Adamski R and Siuta D. Recent advances in agronomic and physio-molecular approaches for improving nitrogen use efficiency in crop plants // Front. Plant Sci., 2022, 13:877544. [CrossRef]

- Watson Lee James, Rahmani Tara Puri Ducha. A glimpse of the nitrogen-fixing wheat possibility// J. Nat. Scien. & Math. Res. 2022, Vol. 8 No. 1, С. 1-9. http://journal.walisongo.ac.id/index.php/jnsmr.

- Yusminah Hala. The effect of nitrogen-fixing bacteria towards upland rice plant growth and nitrogen content // IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2020, Vol. 484, 012086, IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Dalmau, J. , Berbel J. , Ordóñez-Fernández R. Nitrogen fertilization. A review of the risks associated with the inefficiency of its use and policy responses // Sustainability 2021, 13, 5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang M, Hassan MA, Xu K, Zheng C, Rasheed A, Zhang Y, Jin X, Xia X, Xiao Y and He Z. Assessment of winter water and nitrogen use efficiencies through uav-based multispectral phenotyping in wheat // Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11:927. [CrossRef]

- Haroon, M. , Idrees F., Naushahi H. A. Afzal R., Usman M., Qadir T., Husnain R. Nitrogen use efficiency: farming practices and sustainability // Journal of Experimental Agriculture International 36(3): 1-11, 2019; Article no. JEAI.48798. [CrossRef]

- Lekomtsev P., Komarov A. Maintaining soil fertility by optimizing the use of nitrogen fertilizers in precision farming system // BIO Web of Conferences 67, 02002 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Jwaideh, M.A.A. , Sutanudjaja E.H., Dalin C. Global impacts of nitrogen and phosphorus fertiliser use for major crops on aquatic biodiversity // The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 2022, 4 July. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).