1. Introduction

The Philippines has a diverse range of agricultural activities, including the production of poultry, fish, livestock, and crops. The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) reported an increase in farm products, including crops and fisheries, while noting a decrease in livestock. The estimated value of production in agriculture and fishing at constant 2018 prices was PhP 437.74 billion during the first quarter of 2025. This represented a 1.9 percent increase relative to the corresponding quarter of the prior year [

1]. In the first quarter of 2025, crop production in the Philippines was valued at PHP 249.61 billion at constant 2018 prices, reflecting a 1.0% increase. It contributed 57.0 percent to the overall value of production in agriculture and fisheries. The value of the palay output increased by 0.3 percent. During this period, the value of corn production declined by 5.1 percent [

2].

In 2023, lettuce production in the Philippines reached 4.58 thousand metric tons. In 2024, production is projected to reach 4,660 metric tons, representing a 1.75% increase from the previous year. The following years are expected to exhibit a consistent growth trend, with projected increases of 1.72% for 2025, 1.69% for 2026, 1.66% for 2027, and 1.63% for 2028. The projected Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) for the period from 2024 to 2028 is approximately 1.69% annually. Future trends to monitor include the potential effects of climate change on crop yields and developments in agricultural technology and practices [

3]. Agriculture Secretary Francisco P. Tiu Laurel Jr. emphasized the necessity for the Philippines to implement sustainable farming practices due to the increasing challenges presented by climate change, population growth, and diminishing agricultural land. In a nation often impacted by typhoons, the adoption of greenhouse technologies by Filipino farmers could enhance their ability to protect and cultivate crops throughout the year [

4,

5].

The United Nations established the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in 2019. It includes goals for ensuring food security and improving food production methods to make them more environmentally friendly. The 2030 Agenda aims to abolish all poverty, including extreme poverty. This is essential for global sustainability. [

6]. Advancements in efforts to eliminate hunger, enhance nutrition, and foster sustainable agriculture have been inconsistent, primarily influenced by persistent conflicts, global food crises, and challenges related to climate change. The Inter-agency and Expert Group has adopted a new set of seven sub-indicators on SDG Indicators to assess global progress in sustainable agriculture, covering economic, social, and environmental aspects. Data from 2021 revealed that the international status of productive and sustainable agriculture was moderately advanced, as evidenced by a score of 3.4 out of 5, indicating a slight improvement since 2015.[

7,

8]. Additionally, the vegetable industry in the production sector faces significant challenges, including limited climate-smart production technologies and a shortage of greenhouse facilities for crop production [

9].

Greenhouse farming is regarded as a precise and sustainable method within the realm of smart agriculture. While greenhouse gases can facilitate off-season crop growth in indoor environments, it is essential to monitor, control, and manage crop parameters at greenhouse farms with greater precision and security, particularly in harsh climate regions [

10]. Greenhouses are essential in contemporary agriculture, facilitating sustainable food production and promoting environmental conservation [

11]. Conventional greenhouses offer a protected environment for plants; however, they may lack precision and adaptability. The implementation of IoT-enabled greenhouses facilitates intelligent control of environmental conditions through the integration of networked data exchange protocols, actuators, and sensors [

12].

The optimal cultivation temperatures for lettuce range from 15.5 degrees Celsius to 28 degrees Celsius, with humidity levels between 80% and 90%, and specific soil composition requirements [

13,

14]. Intensive crop cultivation and inadequate soil management practices have resulted in agricultural soils globally possessing insufficient levels of essential nutrients for plant growth and experiencing considerable degradation. Lettuce generally exhibits a positive response to fertilizers, with balanced applications of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium yielding the highest production and optimal post-harvest quality [

15]. Monitoring essential soil parameters, including nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, alongside environmental factors such as temperature and moisture, optimizing lettuce growth processes in a greenhouse environment.

This study presents an IoT-based monitoring and automated fertilizer system designed to enhance the growth of Olmetie lettuce in greenhouse settings. The system offers advantages to farmers by enhancing lettuce growth quality while reducing the required workforce and effort through the implementation of optimal practices in innovative farming technologies and precision agriculture.

2. Materials and Methods

The development of an IoT-based monitoring system starts with defining the system requirements.

Table 1 outlines the phases of this research, which began with a literature review, followed by a field study and expert assistance, to determine key factors influencing lettuce cultivation in a greenhouse environment, including temperatures, humidity, light intensity, and soil NPK levels, like the developed system by the Department of Science and Technology (DOST)-funded ‘Project ATLANTIS’, which utilized an aquaponic greenhouse farming system incorporating the Internet of Things (IoT) to streamline the monitoring and regulation of plant nutrients and other factors affecting lettuce growth [

16].

2.1. Data Gathering

The data collection phase involved a review of relevant literature and existing systems, as well as the execution of interviews and surveys within lettuce farms in a pilot agricultural community located in Lucban, Quezon. The activities yielded essential insights into the awareness and perception of farmers regarding agricultural technologies, local cultivation practices, and technical requirements, as shown in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

2.2. Design and Development

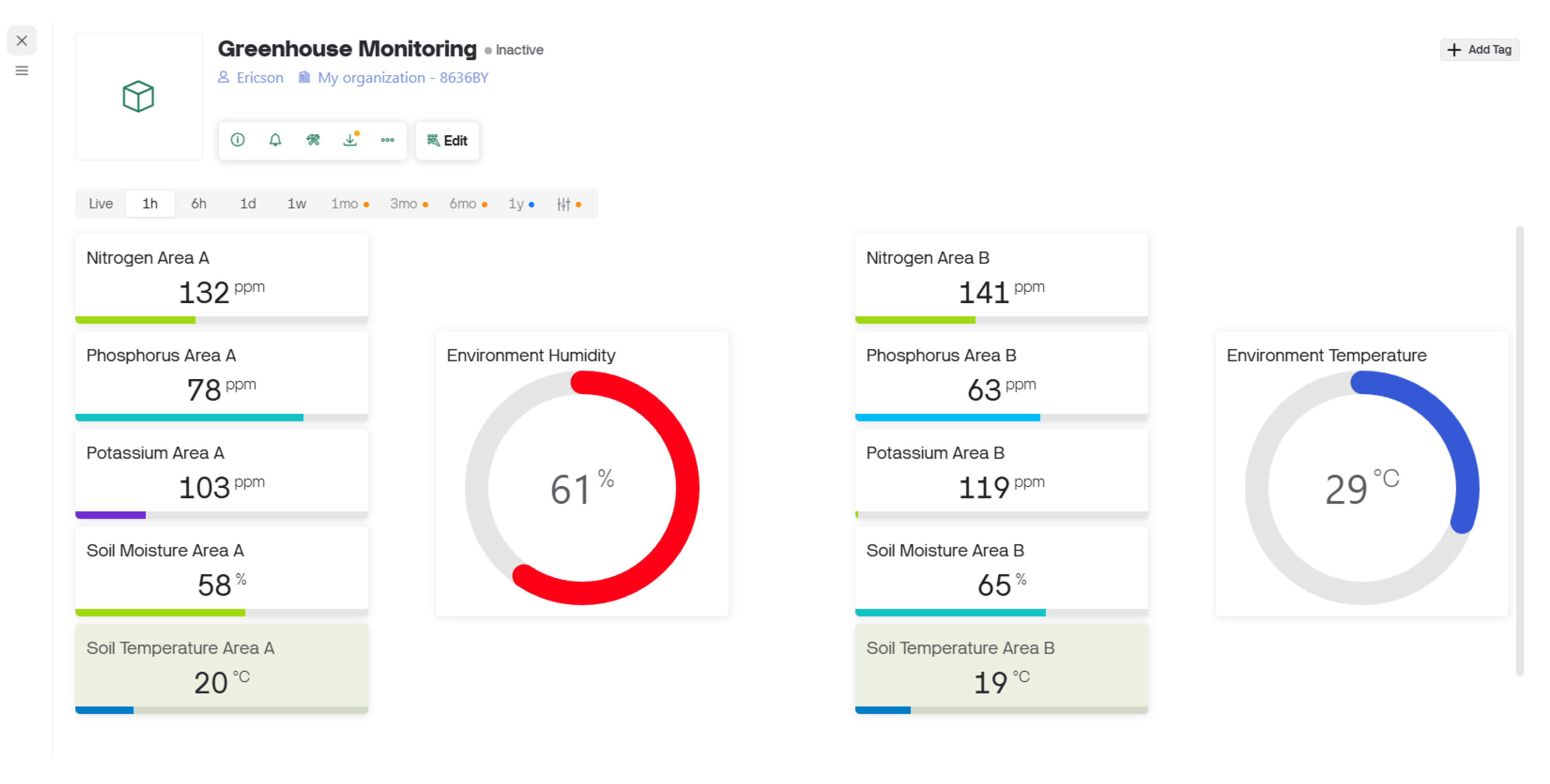

The greenhouse monitoring system is a real-time solution designed to support sustainable crop production. It integrates multiple sensors to measure soil conditions and environmental parameters, including NPK nutrients, soil moisture and temperature, light intensity, and both greenhouse environment humidity and temperature. These data are measured by the sensors and transmitted to the microcontroller, where they are displayed live in the Arduino Cloud dashboard. Another key feature of the automated fertilizer dispenser is that when the system detects NPK values below the threshold, it activates the dispenser and applies the fertilizer evenly to the crops.

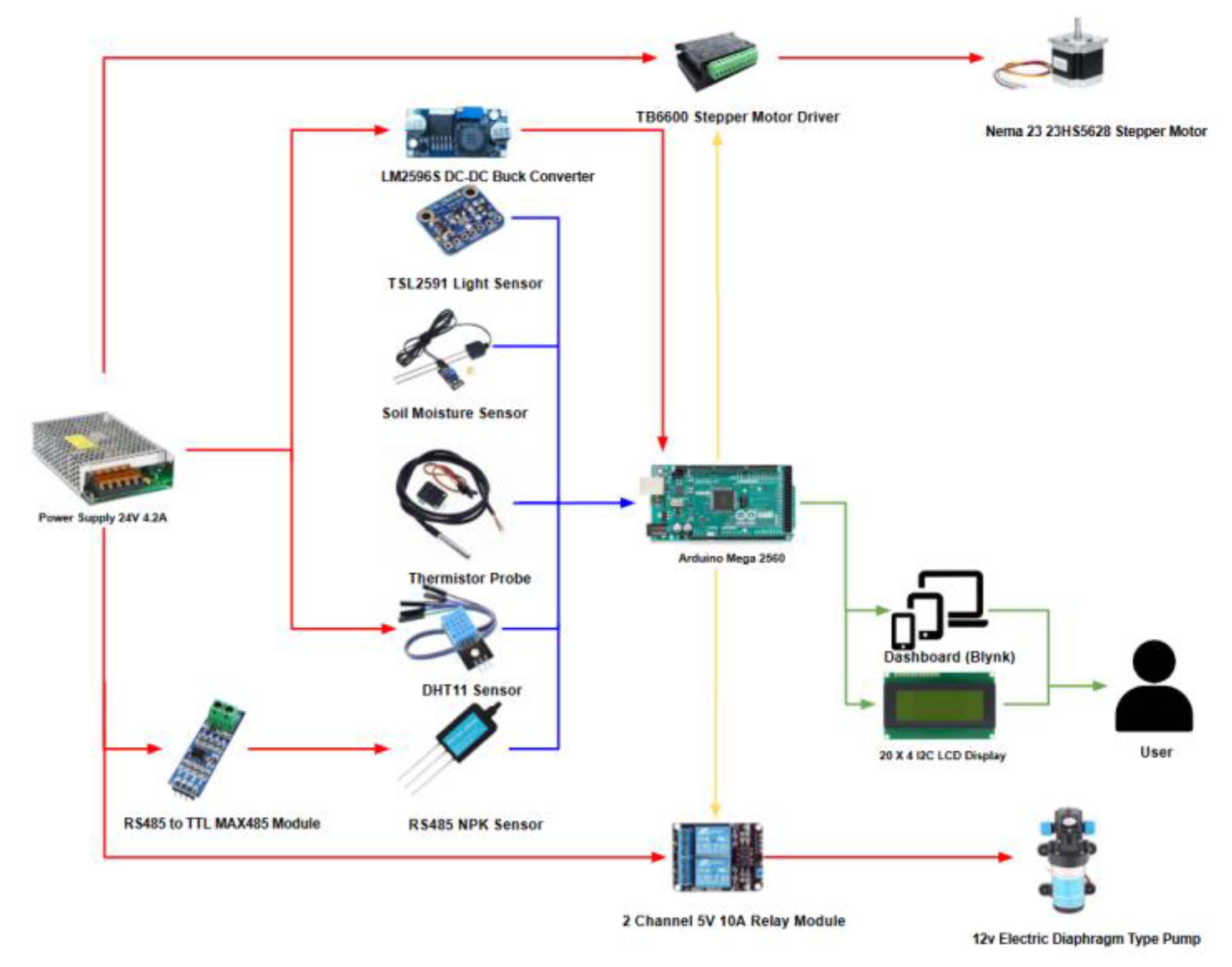

Figure 1 shows the system architecture of the greenhouse monitoring system and the automatic fertilizer dispensing system. The power is supplied by a 24V, 4.2A power supply, which is regulated using DC-DC buck converters to achieve the appropriate voltage levels. The Arduino Mega 2560 serves as the central microcontroller where the system would uses a range of sensors to monitor the essential parameter, an NPK sensor for the nutrients (Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium), a soil moisture to assess the water content of the soil, a thermistor probe to measure the soil temperature, a DHT sensor for environmental temperature and humidity measurement, and the light intensity sensor to track the amount of sunlight there is in the greenhouse.

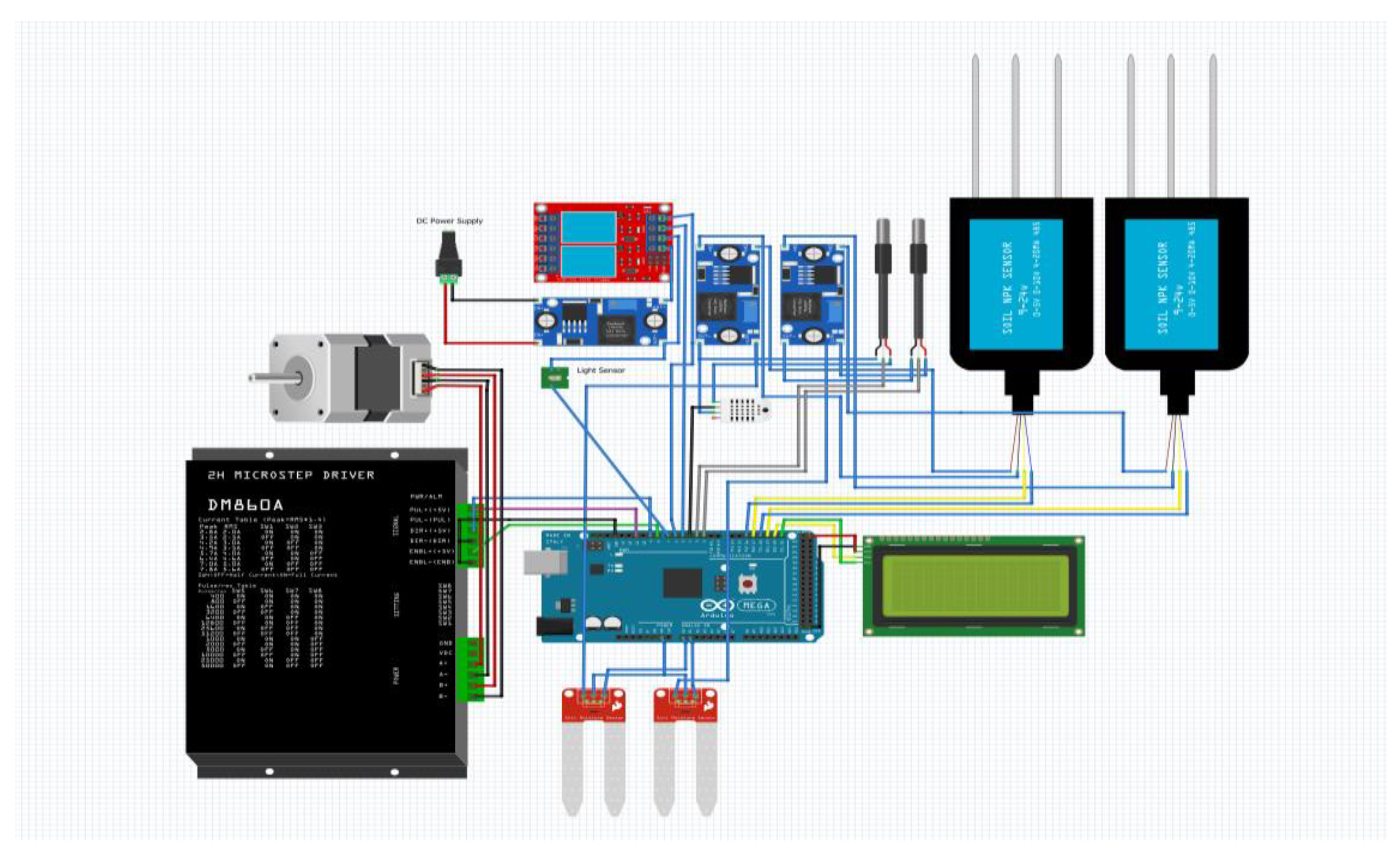

Figure 2 illustrates the circuit diagram that shows the integration of key hardware elements used in creating the Greenhouse Monitoring and Control System prototype. The Arduino Mega 2560, which serves as the core control unit, is powered by the power supply, which forms the foundation of the device. Five (5) sensors: soil temperature, soil moisture, DHT11 (Temperature and Humidity), tsl2561 light sensors, and the NPK sensors are used in greenhouse monitoring to improve control and management of nutrients.

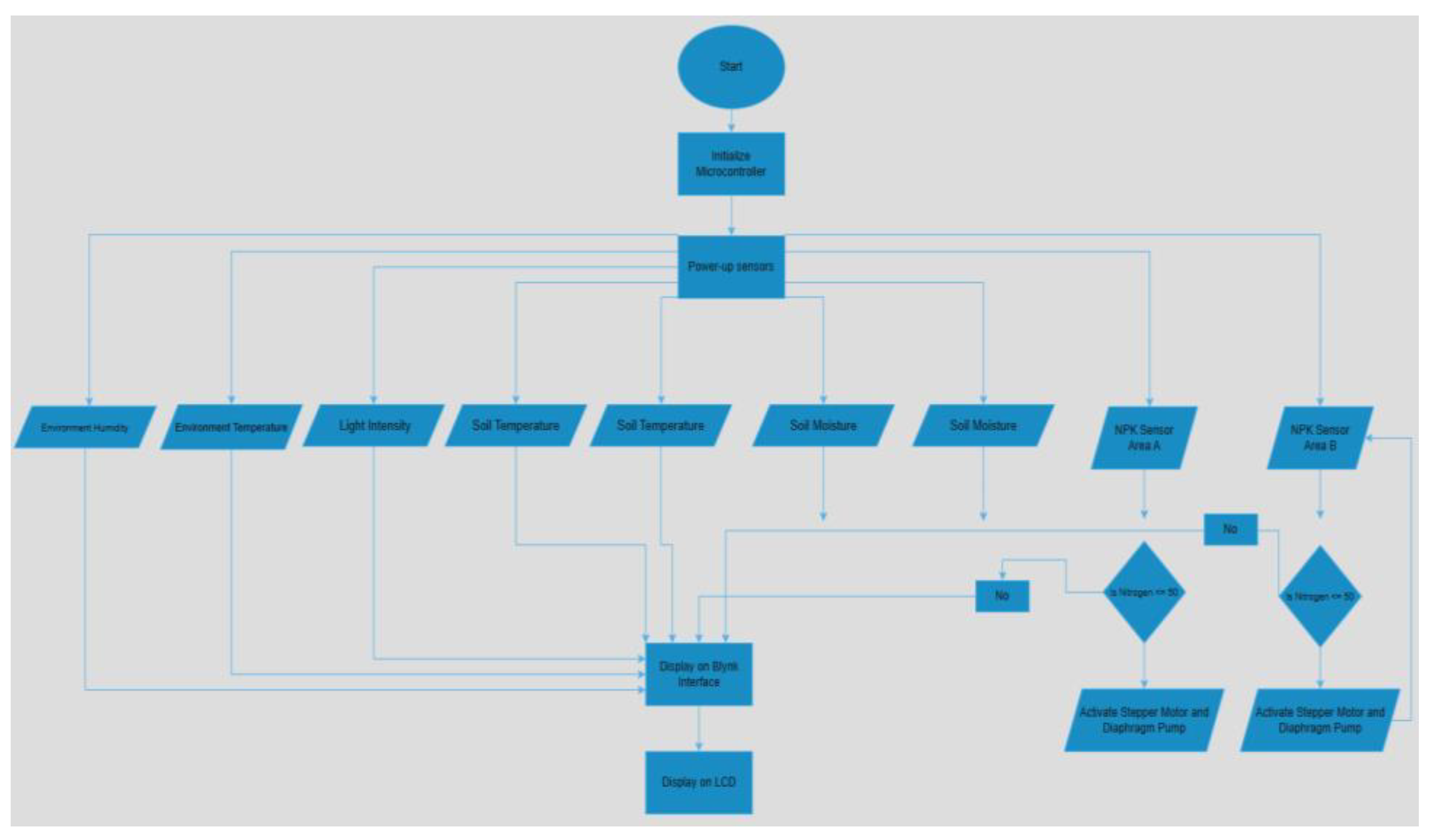

Figure 3 shows the system flowchart of the greenhouse management system, which begins with the microcontroller initializing the sensors and modules. These sensors collect soil data, which is read by the microcontroller and displayed on both the LCD and Blynk dashboard. If it functions properly, the system continuously monitors soil conditions. Two NPK sensors placed in different greenhouse areas trigger the automatic fertilizer dispenser when nutrient levels fall below set thresholds. This creates a continuous feedback loop, ensuring optimal conditions for Olmetie Lettuce with minimal human intervention.

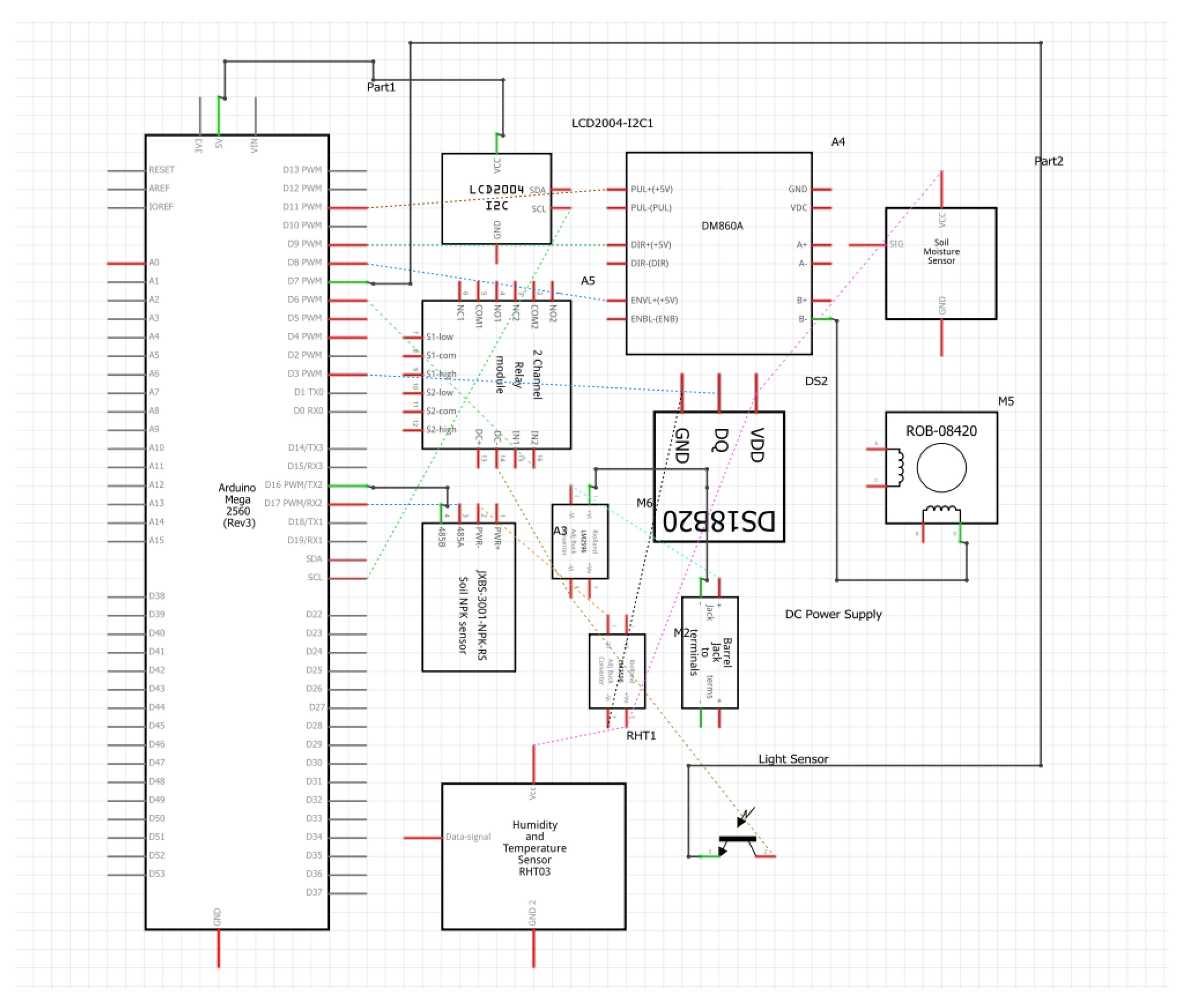

Figure 4 illustrates the schematic diagram of the greenhouse management system and the automatic fertilizer management system. The core of the system is the Arduino Mega 2560 microcontroller, which interfaces with various sensors and other modules. The soil moisture is directly connected to the microcontroller, while the NPK sensor is linked through an RS-485 module. The thermistor probe is also connected directly to the microcontroller. The environmental condition sensors, such as the DHT11 and the light intensity sensor, directly track and send data to the microcontroller. To present the real-time data, an I2C LCD is used. A stepper motor driver (DM860A) and the diaphragm pump control the mechanical dispensing of the fertilizer. The DC power supply powers the system, with voltage regulation managed through the converters to provide stable 5V and 12V outputs for various components.

3. Results and Discussion

Table 4 presents the optimal values for lettuce growth in a greenhouse environment. The different parameters include the NPK nutrients, soil temperature and moisture, and the temperature and humidity of the greenhouse. Those parameters were considered during the construction of the greenhouse and fabrication of the prototype.

3.1. Prototype Assembly and Testing

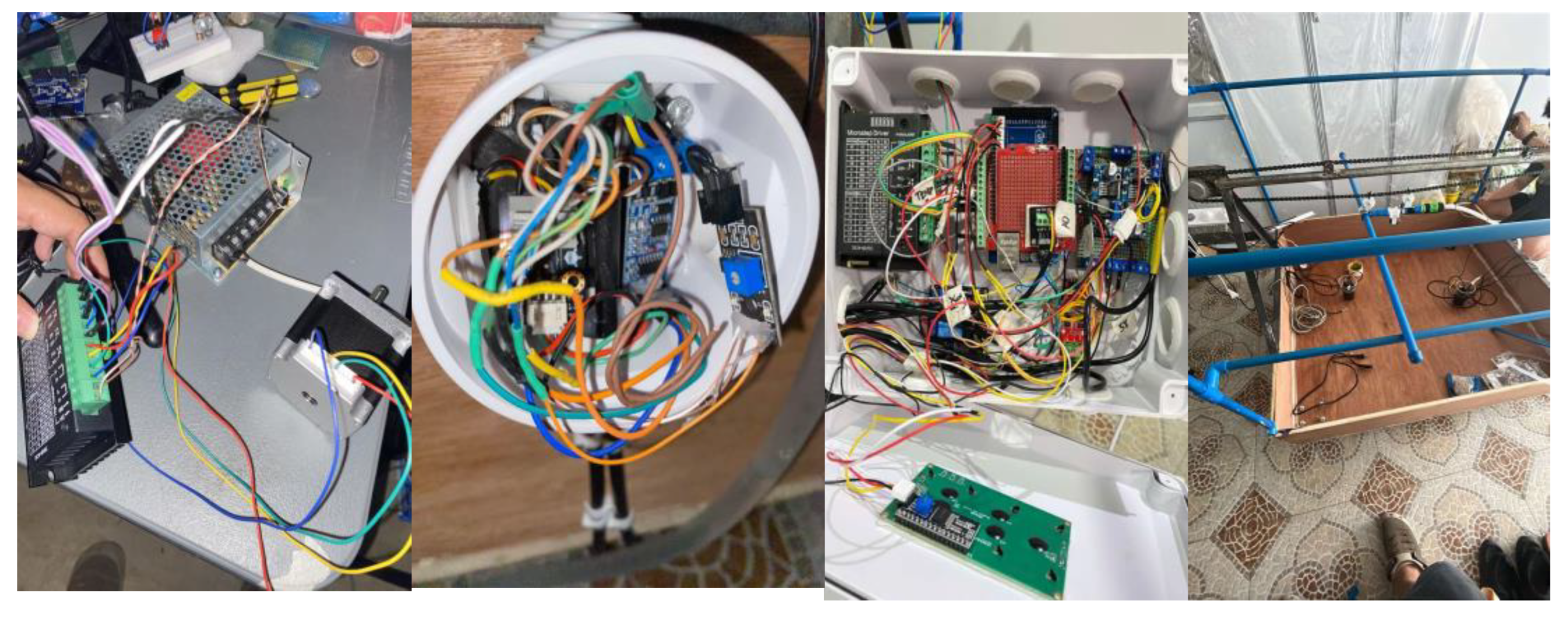

Each component was separately built and tested to confirm its functionality and guarantee operational efficiency.

Figure 5 illustrates the integration of the greenhouse monitoring and fertilizer dispensing system, which entailed connecting essential hardware components, including the Arduino Mega 2560, power supply, DHT11 sensor, soil moisture and temperature sensors, NPK sensor, and light intensity sensor. Adherence to proper cabling methods and electrical safety protocols was rigorously maintained during the installation. A prototype greenhouse frame was created to enable remote system testing following successful integration. This entailed meticulous cutting and construction of wood according to designated measurements to construct a singular greenhouse plot.

The prototype’s initial testing was performed in the established greenhouse setting, as depicted in

Figure 6. The illustration also depicts real-time surveillance of environmental factors through the I2C LCD panel. Concurrently, these characteristics were relayed and shown on the Blynk dashboard, as illustrated in

Figure 7. The fertilizer distribution system successfully elevated the NPK levels to their ideal range throughout testing, showcasing its responsiveness and performance.

4. Conclusion

The implementation of the IoT-Based Monitoring and Automatic Fertilizer System for Optimizing Olmetie Lettuce Growth in Greenhouse Environments has proven to be highly effective and practical, as evidenced by the local farmers of Kopia-Sipag Farmers’ Village. Farmers reported increased confidence in managing crop conditions, improved understanding of real-time soil status, and greater satisfaction with the timely use of fertilizers. The use of Arduino Cloud and the Blynk dashboard provided clear and accessible monitoring tools that can be utilized without requiring extensive technical knowledge. Overall, the prototype shows a strong potential to enhance precision agriculture practices. The prototype may also be used in a wide variety of crops that can be produced in a greenhouse environment.

Acknowledgement

The authors are deeply acknowledging the assistance of Manuel S. Enverga University Foundation and the College of Engineering in providing us with the data required to conduct this research. Our endeavour would not have been a success without their support.

References

- Philippine Statistics Authority, “First Quarter 2025 Value of Production in Philippine Agriculture and Fisheries,” May 2025. Accessed: Jul. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://psa.gov.ph/system/files/aad/Full%20Report%2C%20First%20Quarter%202025%20Value%20of%20Production%20in%20Agriculture%20and%20Fisheries_signed.pdf.

- Philippine Statistics Authority, “Volume of Production of Agriculture and Fisheries for Q1 2025,” May 2025, Accessed: Jul. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/csd/1_Volume%20of%20Production%20of%20Agriculture%20and%20Fisheries%20for%20Q1%202025%20-%20MTF-PSJ-RPA_ONS-signed.pdf.

- Reportlinker.com, “Forecast: Chicory and Lettuce Production in Philippines.” Accessed: Jul. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.reportlinker.com/dataset/267c182d9c9f5bab4d6ae371cbaee384c452831f.

- DA Press Office, “2025 Sustainable Agriculture Forum (April 30, 2025).” Accessed: Jul. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.da.gov.ph/gallery/2025-sustainable-agriculture-forum-april-30-2025/.

- DA Press Office, “DAR: Greenhouses enable farmers to produce crops year-round.” Accessed: Jul. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.da.gov.ph/dar-greenhouses-enable-farmers-to-produce-crops-year-round/.

- R. C. Maaño, R. A. Maaño, P. J. De Castro, E. Chavez, S. De Castro, and C. Maligalig, “SmartHatch: An Internet of Things-Based Temperature and Humidity Monitoring System for Poultry Egg Incubation and Hatchability,” in 2023 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology, ICoICT 2023, Sep. 2023, pp. 178–183. [CrossRef]

- United Nations, “The Sustainable Development Goals Report.” Accessed: Jul. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2024/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2024.pdf.

- United Nations, “Progress Towards the Sustainable Development Goals,” Apr. 2025. Accessed: Jul. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2024/.

- Department of Agriculture - Bureau of Agricultural Research, “Philippine Vegetable Industry Roadmap 2021-2025,” 2022. Accessed: Jul. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.pcaf.da.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Philippine-Vegetable-Industry-Roadmap-2021-2025.pdf.

- K. M. Hosny, W. M. El-Hady, and F. M. Samy, “Technologies, Protocols, and applications of Internet of Things in greenhouse Farming: A survey of recent advances,” Mar. 01, 2025, China Agricultural University. [CrossRef]

- B. Singh, V. K. Pundhir, S. Gangotri, V. Bharadwaj, S. Sharma, and L. Batra, “An intelligent greenhouse monitoring and control system employing Internet of Things,” Journal of Information and Optimization Sciences, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 571–579, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Swathi Manoharan, Chong Peng Lean, Chen Li, Kong Feng Yuan, Ng Poh Kiat, and Mohammed Reyasudin Basir Khan, “IoT-enabled Greenhouse Systems: Optimizing Plant Growth and Efficiency,” Malaysian Journal of Science and Advanced Technology, pp. 169–179, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Petropoulou et al., “Lettuce Production in Intelligent Greenhouses—3D Imaging and Computer Vision for Plant Spacing Decisions,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 6, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- O. R. Zandvakili et al., “Influence of nitrogen source and rate on lettuce yield and quality,” Agron J, Dec. 2021, Accessed: Jul. 14, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://acsess.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/agj2.20966.

- J. Hong et al., “Evaluation of the Effects of Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium Applications on the Growth, Yield, and Quality of Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.),” Agronomy, vol. 12, no. 10, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Valdeavilla and O. Domingo, “Dost Atlantis Project Developed an Automated Greenhouse for Lettuce and Tilapia,” May 2024. Accessed: Jul. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.pcaarrd.dost.gov.ph/index.php/quick-information-dispatch-qid-articles/dost-atlantis-project-developed-an-automated-greenhouse-for-lettuce-and-tilapia.

- A. D. G. Santillano-Cazares, E. A. Montoya-Camacho, M. A. González-Vázquez, J. A. Gutiérrez-Martínez, and J.I. Rico-García, “A sensor-based smart irrigation system for greenhouse cultivation of lettuce based on soil moisture and temperature conditions,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 13, Art. no. 5881, Jul. 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10353484/.

- N. A. Rahman, M. F. Abd Wahid, M. R. Yusop, and M. A. A. Aziz,”Importance of soil temperature for the growth of temperate crops under a tropical climate and functional role of soil microbial diversity,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 15, no. 10, Oct. 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6031386/.

- Horticulture South Africa, “Lettuce fertilizer application tables according to soil types,” [Online]. Available: https://www.horticulture.org.za/lettuce-fertilizer-application-tables-according-to-soil-types/.

- INSONGREEN, “How to grow lettuce in a greenhouse: Step-by-step guide,” [Online]. Available: https://www.insongreen.com/how-to-grow-lettuce-in-a-greenhouse-step-by-step-guide/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).