Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mosquito collections

2.2. DNA extraction and sequencing

2.3. Mitochondrial genome assembly and annotation

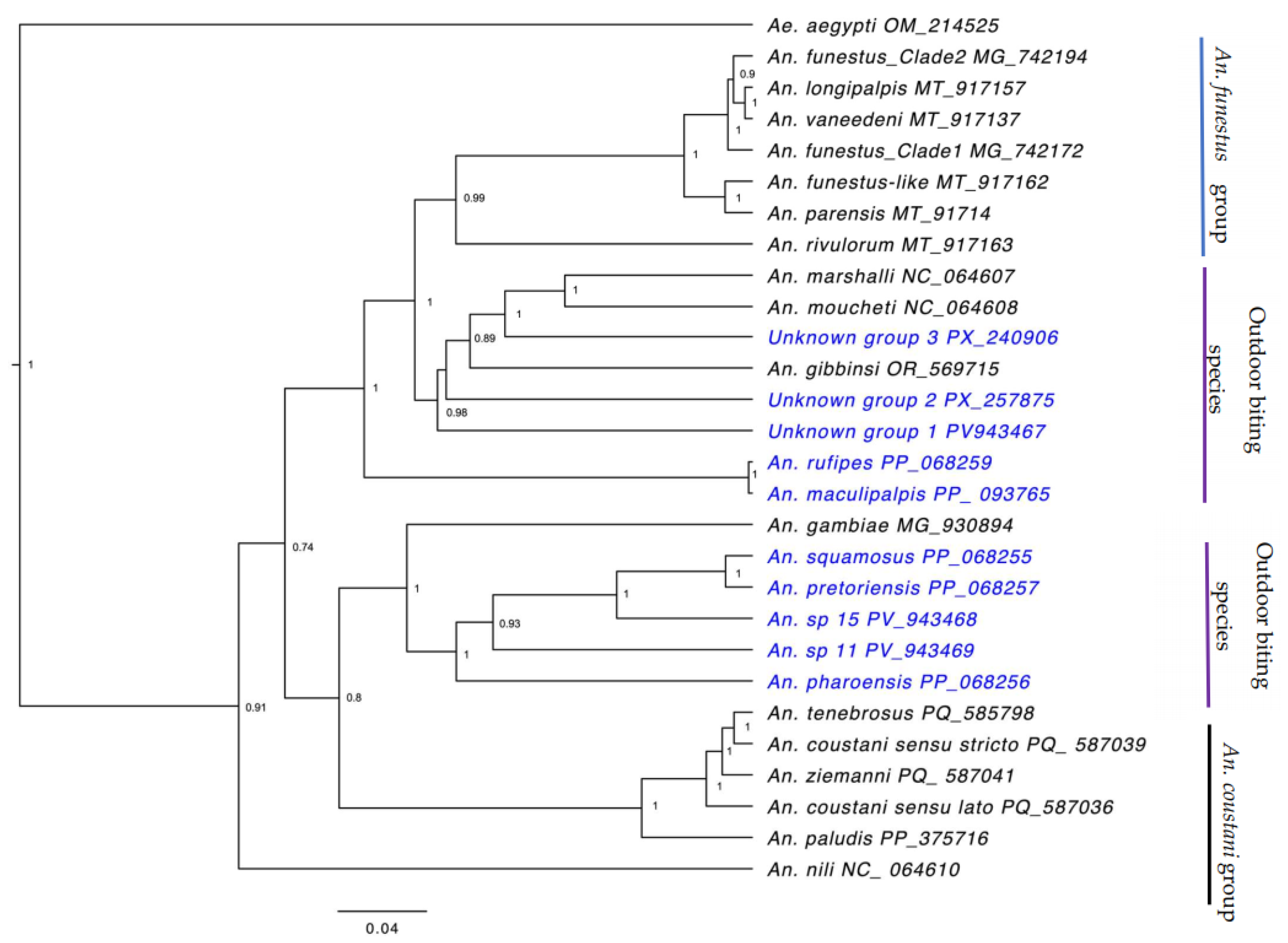

2.4. Phylogenetic analysis and tree construction

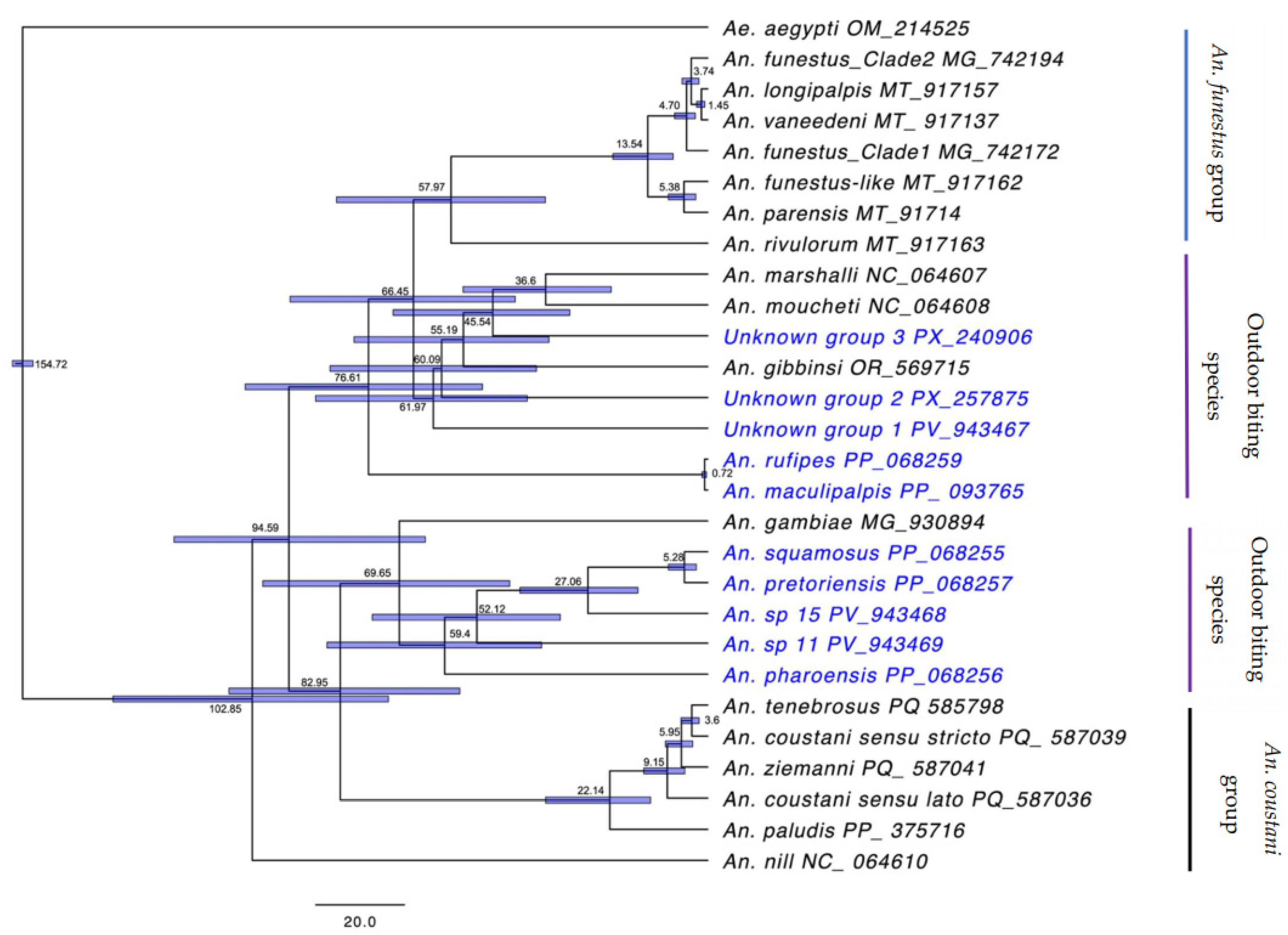

2.5. Dating time estimation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Rodriguez, M.H. Residual Malaria: Limitations of Current Vector Control Strategies to Eliminate Transmission in Residual Foci. J Infect Dis 2021, 223, S55–S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinszer, K.; Talisuna, A.O. Fighting Insecticide Resistance in Malaria Control. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2023, 23, 138–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrard-Smith, E.; Winskill, P.; Hamlet, A.; Ngufor, C.; N’Guessan, R.; Guelbeogo, M.W.; Sanou, A.; Nash, R.K.; Hill, A.; Russell, E.L.; et al. Optimising the Deployment of Vector Control Tools against Malaria: A Data-Informed Mod-elling Study. The Lancet Planetary Health 2022, 6, e100–e109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanou, A.; Nelli, L.; Guelbéogo, W.M.; Cissé, F.; Tapsoba, M.; Ouédraogo, P.; Sagnon, N.; Ranson, H.; Matthiopoulos, J.; Ferguson, H.M. Insecticide Resistance and Behavioural Adaptation as a Response to Long-Lasting Insecticidal Net Deployment in Malaria Vectors in the Cascades Region of Burkina Faso. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 17569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryce, J.; Medley, N.; Choi, L. Indoor Residual Spraying for Preventing Malaria in Communities Using Insecticide-treated Nets - Pryce, J - 2022 | Cochrane Library.

- Sherrard-Smith, E.; Ngufor, C.; Sanou, A.; Guelbeogo, M.W.; N’Guessan, R.; Elobolobo, E.; Saute, F.; Varela, K.; Chaccour, C.J.; Zulliger, R.; et al. Inferring the Epidemiological Benefit of Indoor Vector Control Interventions against Malaria from Mosquito Data. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, M.R.; Overgaard, H.J.; Abaga, S.; Reddy, V.P.; Caccone, A.; Kiszewski, A.E.; Slotman, M.A. Outdoor Host Seeking Behaviour of Anopheles gambiae Mosquitoes Following Initiation of Malaria Vector Control on Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. Malaria Journal 2011, 10, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiime, A.K.; Smith, D.L.; Kilama, M.; Rek, J.; Arinaitwe, E.; Nankabirwa, J.I.; Kamya, M.R.; Conrad, M.D.; Dorsey, G.; Akol, A.M.; et al. Impact of Vector Control Interventions on Malaria Transmission Intensity, Outdoor Vector Biting Rates and Anopheles Mosquito Species Composition in Tororo, Uganda. Malaria Journal 2019, 18, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, S.; Brandy Mosquito Vector Diversity and Malaria Transmission. Front. Malar. 2025, 3.

- Tabue, R.N.; Awono-Ambene, P.; Etang, J.; Atangana, J.; C, A.-N.; Toto, J.C.; Patchoke, S.; Leke, R.G.F.; Fondjo, E.; Mnzava, A.P.; et al. Role of Anopheles (Cellia) rufipes (Gough, 1910) and Other Local Anophelines in Human Malaria Transmission in the Northern Savannah of Cameroon: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Parasites & Vectors 2017, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saili, K.; de Jager, C.; Sangoro, O.P.; Nkya, T.E.; Masaninga, F.; Mwenya, M.; Sinyolo, A.; Hamainza, B.; Chanda, E.; Fillinger, U.; et al. Anopheles rufipes Implicated in Malaria Transmission Both Indoors and Outdoors alongside Anopheles funestus and Anopheles arabiensis in Rural South-East Zambia. Malaria Journal 2023, 22, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, D.E.; Healey, A.J.E.; McKeown, N.J.; Thomas, C.J.; Macarie, N.A.; Siaziyu, V.; Singini, D.; Liywalii, F.; Sakala, J.; Silumesii, A.; et al. Temporally Consistent Predominance and Distribution of Secondary Malaria Vectors in the Anopheles Community of the Upper Zambezi Floodplain. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornadel, C.M.; Norris, L.C.; Franco, V.; Norris, D.E. Unexpected Anthropophily in the Potential Secondary Malaria Vectors Anopheles coustani s. l. and Anopheles squamosus in Macha, Zambia.Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2011, 11, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendershot, A.L. Understanding the Role of An. Coustani Complex Members as Malaria Vector Species in the Democratic Republic of Congo. thesis, University of Notre Dame, 2021.

- Goupeyou-Youmsi, J.; Rakotondranaivo, T.; Puchot, N.; Peterson, I.; Girod, R.; Vigan-Womas, I.; Paul, R.; Ndiath, M.O.; Bourgouin, C. Differential Contribution of Anopheles Coustani and Anopheles Arabiensis to the Transmission of Plasmodium Falciparum and Plasmodium Vivax in Two Neighbouring Villages of Madagascar. Parasites & Vectors 2020, 13, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sougoufara, S.; Ottih, E.C.; Tripet, F. The Need for New Vector Control Approaches Targeting Outdoor Biting Anopheline Malaria Vector Communities. Parasites & Vectors 2020, 13, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, N.F.; Laurent, B.S.; Sikaala, C.H.; Hamainza, B.; Chanda, J.; Chinula, D.; Krishnankutty, S.M.; Mueller, J.D.; Deason, N.A.; Hoang, Q.T.; et al. Unexpected Diversity of Anopheles Species in Eastern Zambia: Implications for Evalu-ating Vector Behavior and Interventions Using Molecular Tools. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 17952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.; Hemming-Schroeder, E.; Wang, X.; Kibret, S.; Zhou, G.; Atieli, H.; Lee, M.-C.; Afrane, Y.A.; Githeko, A.K.; Yan, G. Extensive New Anopheles Cryptic Species Involved in Human Malaria Transmission in Western Kenya. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 16139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, J.C.; Norris, D.E. Implicating Cryptic and Novel Anophelines as Malaria Vectors in Africa. Insects 2017, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.M.; Ciubotariu, I.I.; Muleba, M.; Lupiya, J.; Mbewe, D.; Simubali, L.; Mudenda, T.; Gebhardt, M.E.; Carpi, G.; Malcolm, A.N.; et al. Multiple Novel Clades of Anopheline Mosquitoes Caught Outdoors in Northern Zambia. Front. Trop. Dis 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, M. Key to the Females of Afrotropical Anopheles Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Malaria Journal 2020, 19, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraes Zenker, M.; Portella, T.P.; Pessoa, F.A.C.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Galetti, P.M. Low Coverage of Species Con-strains the Use of DNA Barcoding to Assess Mosquito Biodiversity. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 7432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, J.R.; Wahid, I.; Sudirman, R.; Small, S.T.; Hendershot, A.L.; Baskin, R.N.; Burton, T.A.; Makuru, V.; Xiao, H.; Yu, X.; et al. Molecular Analysis Reveals a High Diversity of Anopheles Species in Karama, West Sulawesi, Indonesia. Parasites & Vectors 2020, 13, 379. [CrossRef]

- Neafsey, Daniel E. , Robert M. Waterhouse, Mohammad R. Abai, Sergey S. Aganezov, Max A. Alekseyev, James E. Allen, James Amon et al. Highly evolvable malaria vectors: the genomes of 16 Anopheles mosquitoes. Science 2015, 347, 1258522.

- Bartilol, B.; Omuoyo, D.; Karisa, J.; Ominde, K.; Mbogo, C.; Mwangangi, J.; Maia, M.; Rono, M.K. Vectorial Capacity and TEP1 Genotypes of Anopheles gambiae sensu lato Mosquitoes on the Kenyan Coast. Parasites & Vectors 2022, 15, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máquina, M.; Opiyo, M.A.; Cuamba, N.; Marrenjo, D.; Rodrigues, M.; Armando, S.; Nhate, S.; Luis, F.; Saúte, F.; Candrinho, B.; et al. Multiple Anopheles Species Complicate Downstream Analysis and Decision-Making in a Malaria Pre-Elimination Area in Southern Mozambique. Malar J 2024, 23, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustapha, A.M.; Musembi, S.; Nyamache, A.K.; Machani, M.G.; Kosgei, J.; Wamuyu, L.; Ochomo, E.; Lobo, N.F. Secondary Malaria Vectors in Western Kenya Include Novel Species with Unexpectedly High Densities and Parasite Infection Rates. Parasites & Vectors 2021, 14, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assa, A.; Eligo, N.; Massebo, F. Anopheles Mosquito Diversity, Entomological Indicators of Malaria Transmission and Challenges of Morphological Identification in Southwestern Ethiopia. Trop Med Health 2023, 51, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepomichene, T.N.J.J.; Tata, E.; Boyer, S. Malaria Case in Madagascar, Probable Implication of a New Vector, Anopheles Coustani. Malar J 2015, 14, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.M.; Ciubotariu, I.I.; Gebhardt, M.E.; Lupiya, J.S.; Mbewe, D.; Muleba, M.; Stevenson, J.C.; Norris, D.E. Evalu-ation of Anopheline Diversity and Abundance across Outdoor Collection Schemes Utilizing CDC Light Traps in Nch-elenge District, Zambia. Insects 2024, 15, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciubotariu, I.I.; Jones, C.M.; Kobayashi, T.; Bobanga, T.; Muleba, M.; Pringle, J.C.; Stevenson, J.C.; Carpi, G.; Norris, D.E. for the Southern and Central Africa International Centers of Excellence for Malaria Research Genetic Diversity of Anopheles Coustani (Diptera: Culicidae) in Malaria Transmission Foci in Southern and Central Africa. Journal of Medical Entomology 2020, 57, 1782–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomé, G.; Riddin, M.; Braack, L. Species Composition, Seasonal Abundance, and Biting Behavior of Malaria Vectors in Rural Conhane Village, Southern Mozambique. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebhardt, M.E.; Krizek, R.S.; Coetzee, M.; Koekemoer, L.L.; Dahan-Moss, Y.; Mbewe, D.; Lupiya, J.S.; Muleba, M.; Stevenson, J.C.; Moss, W.J.; et al. Expanded Geographic Distribution and Host Preference of Anopheles Gibbinsi (Anopheles Species 6) in Northern Zambia. Malaria Journal 2022, 21, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.; Patel, N.; Marshall, C.; Gripkey, H.; Ditter, R.E.; Crepeau, M.W.; Toilibou, A.; Amina, Y.; Cornel, A.J.; Lee, Y.; et al. Population Genetics of Anopheles Pretoriensis in Grande Comore Island. Insects 2022, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio-nkondjio, C.; Kerah, C.H.; Simard, F.; Awono-ambene, P.; Chouaibou, M.; Tchuinkam, T.; Fontenille, D. Complexity of the Malaria Vectorial System in Cameroon: Contribution of Secondary Vectors to Malaria Transmission. Journal of Medical Entomology 2006, 43, 1215–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calzolari, M.; Bellin, N.; Dottori, M.; Torri, D.; Di Luca, M.; Rossi, V.; Magoga, G.; Montagna, M. Integrated Taxon-omy to Advance Species Delimitation of the Anopheles Maculipennis Complex. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 30914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, S.; Gebhardt, M.E.; Simubali, L.; Saili, K.; Hamwata, W.; Chilusu, H.; Muleba, M.; McMeniman, C.J.; Mar-tin, A.C.; Moss, W.J.; et al. Phylogenetic Taxonomy of the Zambian Anopheles Coustani Group Using a Mitogenomics Approach. Malaria Journal 2025, 24, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Li, L.; Men, X. Mitochondrial DNA as a Molecular Marker in Insect Ecology: Current Status and Future Prospects. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 2021, 114, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.; Crepeau, M.; Lee, Y.; Gripkey, H.; Rompão, H.; Cornel, A.J.; Pinto, J.; Lanzaro, G.C. Complete Mitoge-nome Sequence of Anopheles Coustani from São Tomé Island. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2020, 5, 3376–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.-H.; He, S.-L.; Fu, W.-B.; Yan, Z.-T.; Hu, Y.-J.; Yuan, H.; Wang, M.-B.; Chen, B. Mitogenome-Based Phyloge-ny of Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Insect Sci 2024, 31, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.-H.; He, S.-L.; Fu, W.-B.; Yan, Z.-T.; Hu, Y.-J.; Yuan, H.; Wang, M.-B.; Chen, B. Mitogenome-Based Phyloge-ny of Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Insect Science 2024, 31, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohmann, K.; Mirarab, S.; Bafna, V.; Gilbert, M.T.P. Beyond DNA Barcoding: The Unrealized Potential of Genome Skim Data in Sample Identification. Molecular Ecology 2020, 29, 2521–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yan, Z.-T.; Fu, W.-B.; Yuan, H.; Li, X.-D.; Chen, B. Complete Mitogenomes of Anopheles peditaeniatus and Anopheles nitidus and Phylogenetic Relationships within the Genus Anopheles Inferred from Mitogenomes. Parasites & Vectors 2021, 14, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Villegas, L.; Assis-Geraldo, J.; Koerich, L.B.; Collier, T.C.; Lee, Y.; Main, B.J.; Rodrigues, N.B.; Orfano, A.S.; Pires, A.C.A.M.; Campolina, T.B.; et al. Characterization of the Complete Mitogenome of Anopheles aquasalis, and Phylo-genetic Divergences among Anopheles from Diverse Geographic Zones. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0219523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, R.; Gebhardt, M.E.; Lupiya, J.S.; Muleba, M.; Norris, D.E. The First Complete Mitochondrional Genome of Anopheles Gibbinsi Using a Skimming Sequencing Approach. F1000Res 2024, 13, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierckxsens, N.; Mardulyn, P.; Smits, G. NOVOPlasty: De Novo Assembly of Organelle Genomes from Whole Ge-nome Data. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, e18. [Google Scholar]

- Bernt, M.; Donath, A.; Jühling, F.; Externbrink, F.; Florentz, C.; Fritzsch, G.; Pütz, J.; Middendorf, M.; Stadler, P.F. MITOS: Improved de Novo Metazoan Mitochondrial Genome Annotation. Mol Phylogenet Evol 2013, 69, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada, D. jModelTest: Phylogenetic Model Averaging. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2008, 25, 1253–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, R.; Heled, J.; Kühnert, D.; Vaughan, T.; Wu, C.-H.; Xie, D.; Suchard, M.A.; Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J. BEAST 2: A Software Platform for Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis. PLOS Computational Biology 2014, 10, e1003537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywinski, J.; Grushko, O.G.; Besansky, N.J. Analysis of the Complete Mitochondrial DNA from Anopheles funestus: An Improved Dipteran Mitochondrial Genome Annotation and a Temporal Dimension of Mosquito Evolution. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 2006, 39, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouafou, L.; Makanga, B.K.; Rahola, N.; Boddé, M.; Ngangué, M.F.; Daron, J.; Berger, A.; Mouillaud, T.; Makunin, A.; Korlević, P.; et al. Host Preference Patterns in Domestic and Wild Settings: Insights into Anopheles Feeding Behavior. Evol Appl 2024, 17, e13693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, M.E.; Searle, K.M.; Kobayashi, T.; Shields, T.M.; Hamapumbu, H.; Simubali, L.; Mudenda, T.; Thuma, P.E.; Stevenson, J.C.; Moss, W.J.; et al. Understudied Anophelines Contribute to Malaria Transmission in a Low-Transmission Setting in the Choma District, Southern Province, Zambia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2022, 106, 1406–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, M.; McKenzie, B.A.; Rabaovola, B.; Sutcliffe, A.; Dotson, E.; Zohdy, S. Widespread Zoophagy and Detection of Plasmodium Spp. in Anopheles Mosquitoes in Southeastern Madagascar. Malaria Journal 2021, 20, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschale, Y.; Getachew, A.; Yewhalaw, D.; De Cristofaro, A.; Sciarretta, A.; Atenafu, G. Systematic Review of Sporo-zoite Infection Rate of Anopheles Mosquitoes in Ethiopia, 2001–2021. Parasites & Vectors 2023, 16, 437. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, J.E.; Ciubotariu, I.I.; Simubali, L.; Mudenda, T.; Moss, W.J.; Carpi, G.; Norris, D.E.; Stevenson, J.C.; on be-half of Southern and Central Africa International Centers of Excellence for Malaria Research Phylogenetic Complexity of Morphologically Identified Anopheles squamosus in Southern Zambia. Insects 2021, 12, 146. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Dryden, D.S.; Broder, B.A.; Tadimari, A.; Tanachaiwiwat, P.; Mathias, D.K.; Thongsripong, P.; Reeves, L.E.; Ali, R.L.M.N.; Gebhardt, M.E.; et al. A Comprehensive Review: Biology of Anopheles squamosus, an Understudied Malaria Vector in Africa. Insects 2025, 16, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Identification | Contig Size | GC % | AT % | GenBank Accession # |

| Morphological | ||||

| An. pretoriensis | 15348 | 23.0 | 77.0 | PP_068257 |

| An. pharoensis | 15346 | 23.7 | 76.3 | PP_068256 |

| An. rufipes | 15362 | 22.9 | 77.1 | PP_068259 |

| An. squamosus | 15349 | 23.1 | 76.9 | PP_068255 |

| An. maculipalpis | 15361 | 23.4 | 76.6 | PP_093765 |

| Molecular | ||||

| Species 11 | 15350 | 23.1 | 76.9 | PV_943469 |

| Species 15 | 15354 | 22.8 | 77.2 | PV_943468 |

| Unknown group 1 | 15398 | 21.1 | 78.9 | PV_943467 |

| Unknown group 2 | 15534 | 23.1 | 76.9 | PX_257875 |

| Unknown group 3 | 15436 | 20.3 | 79.7 | PX_240906 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).