1. Introduction

The relationship between dietary intake and mental health is increasingly recognized as bidirectional and clinically relevant [

1,

2,

3,

4]. A growing body of research has highlighted the possible influence of nutrition on psychological processes, brain function, and psychiatric outcomes, including mood, cognition, behavior, and emotional regulation [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In parallel, the emergence of Nutritional Psychology as a new interdisciplinary field aims to systematize these findings, provide a shared theoretical framework, and create novel language, tools, and training to support the integration of nutritional science into clinical mental health practice [

13].

Despite this momentum, mental health and nutrition professionals often lack adequate training to implement such an integrated approach. Surveys show that between 47.5% and 66.3% of psychologists report no formal nutrition education, yet many still address dietary issues in therapy sessions [

14,

15]. Similarly, dietitians and nutritionists report some exposure to psychological content, often limited to basic undergraduate coursework, and feel underprepared to address mental health concerns within their scope of practice [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Nevertheless, interest in additional training remains high across both disciplines; up to 97% of respondents in recent studies expressed a desire to expand their knowledge of nutrition-mental health interconnections [

14,

15].

While promising models of interprofessional collaboration have emerged, such as Interprofessional Enhanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT-IE) in the treatment of eating disorders [

18], the systematic implementation of collaboration between psychologists and dietitians remains underdeveloped for broader mental health concerns, such as depression, anxiety, and emotion regulation [

16]. Similar gaps have also been observed in obesity and weight management, where psychological interventions such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Motivational Interviewing, and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) remain inconsistently implemented in community and Tier 2 care services, highlighting the need for systematic integration of essential evidence-based psychological approaches into primary care [

19]. In this regard, one of the central missions of the “Center for Nutritional Psychology (CNP)” is to promote collaboration and communication between the fields of nutrition and psychology by identifying and addressing existing barriers and by advancing the integration of nutritional approaches into broader mental health care [

20]. Barriers to this integration include a lack of formal interdisciplinary education, limited role clarity, absence of a shared clinical language, and fears of overstepping professional boundaries [

16,

17,

21]. Additional obstacles include aspects such as billing and financial feasibility [

17,

21].

To address these gaps, it is essential to better understand how professionals from both fields currently approach the nutrition–mental health interface, how they perceive collaboration, and what barriers and training needs they identify. The development of evidence-based educational programs and collaborative frameworks requires input from practitioners working at this intersection. Without this information, integration efforts may remain fragmented and lack ecological validity.

The present study aims to:

- -

Explore how much mental health and nutrition professionals currently engage with each other’s domains in clinical practice,

- -

Determine the nature and extent of their formal and informal training in nutrition related to mental health

- -

Identify perceived barriers and training gaps, and

- -

Assess interest in interdisciplinary collaboration, education, and training.

Through a structured online survey, we examined the frequency with which psychologists address nutrition and dietitians address mental health, the characteristics of their formal and informal training, their openness to evidence-based interdisciplinary education, and their actual experiences with interprofessional collaboration. By gathering both quantitative and qualitative data, this study seeks to inform the development of practical frameworks and training programs to support the growing field of Nutritional Psychology and its implementation in routine care.

2. Materials and Methods

This study presents a secondary analysis of data from an online survey conducted by CNP in 2025. The original survey was designed to explore current practices, training, perceived barriers, and attitudes toward interprofessional collaboration between mental health and nutrition professionals.

The questionnaire was developed collaboratively by a multidisciplinary team affiliated with CNP [

20]. It included items assessing professional background, frequency of addressing nutrition (among mental health professionals) or mental health (among nutrition professionals) in clinical practice, formal and informal training in nutrition related to mental health, perceived barriers to integration, interest in interdisciplinary training, and perceptions regarding the clinical utility of collaboration.

The answers provided by participants on formal and informal education were used to derive estimates of the quantity of training in nutrition-related to mental health that participants had received. For formal training, points were assigned as follows: 1 point for one undergraduate course, 2 points for a professional certificate, 3 points for more than one undergraduate course, and 4 points for graduate coursework. This was summed to produce the final score representing an estimate of the quantity of formal education in nutrition related to mental health. The quantity of informal training was estimated by simply counting the number of different sources/methods of informal knowledge participants listed (self-taught, workshops and similar activities, and professional activities or mentoring.

Respondents were also asked to rank seven common barriers to integration (lack of training, unclear professional boundaries, limited access to resources, time constraints, lack of a common language, reimbursement issues, and perceived lack of evidence) based on importance (from 1 = least important to 7 = most important). The survey combined both closed- and open-ended questions and was tailored to the respondent’s professional category (e.g., psychologist or dietitian) (see

Figure 1).

The survey was disseminated between May and July 2025 via professional mailing lists, social media channels, institutional networks, and direct outreach to clinicians affiliated with CNP and collaborating institutions. Eligibility criteria included being a licensed or in-training psychologist or other mental health professional, nutritionist, or dietitian. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, though respondents could optionally provide their email address to receive follow-up communications.

Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables, means, medians, and standard deviations were calculated for quantitative variables. Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparing mean ranks of variables that could be considered ordinal, while rank-biserial correlation coefficient (rᵣbis) was used as a measure of effect size. Exploratory factor analysis using the principal axis factoring method and varimax orthogonal rotation was used to explore the nature of associations between barrier rankings. Although participants were instructed to rank the barriers, it was noted that they treated these questions as rating scales, assigning each a value of 1 to 7 independently. It was deemed that this type of response sufficiently approximates Likert scale to justify the use of exploratory factor analysis. Analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel, JASP, and IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

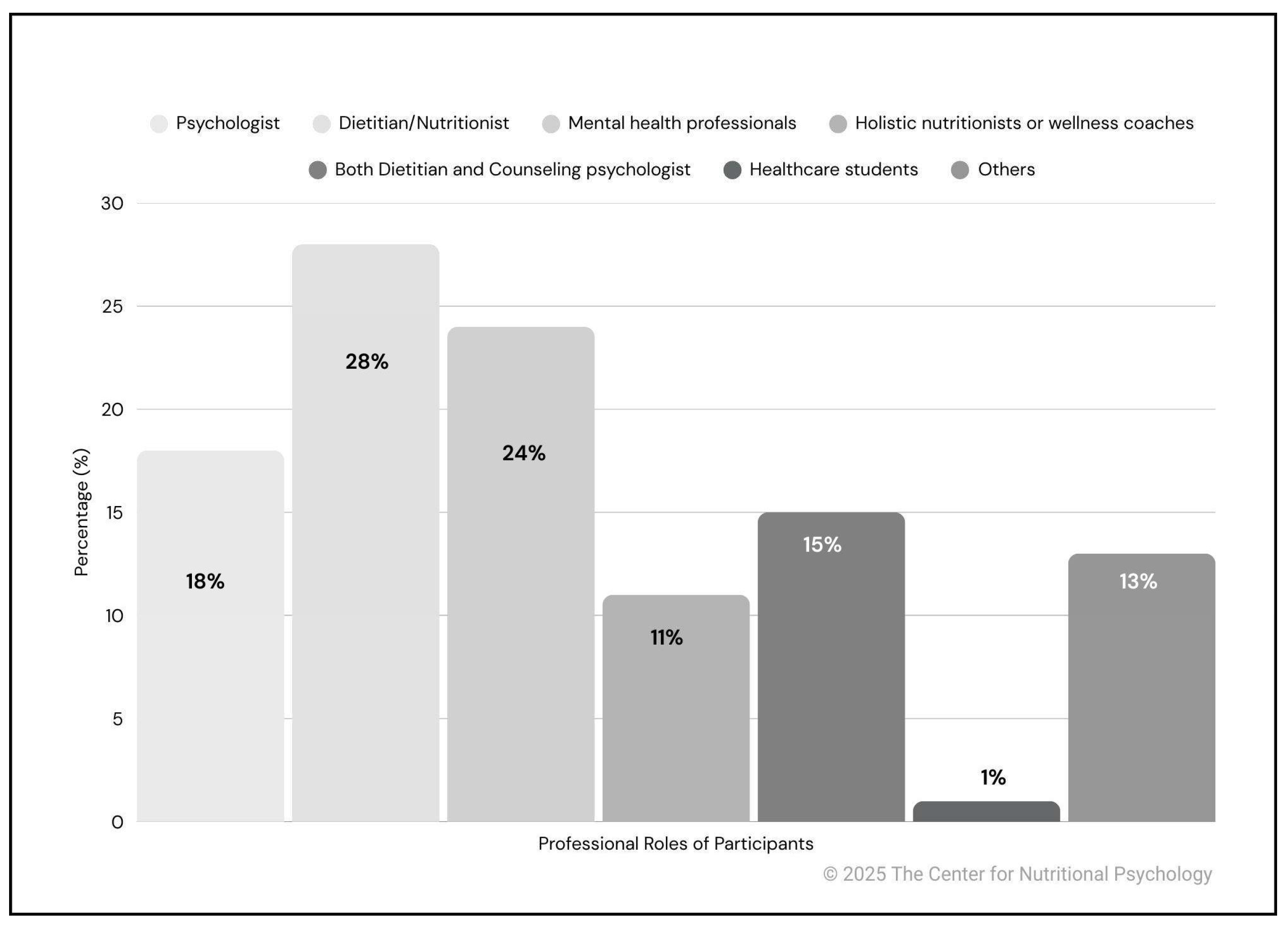

A total of 199 professionals completed the survey (

Figure 2). The most represented category was dietitians/nutritionists, with 56 respondents (28%), followed by mental health professionals, including LPCCs, LMFTs, LMHCs, and NBCCs (47 respondents; 24%), and psychologists (36 respondents; 18%). In addition, two participants declared being both a dietitian and a counseling psychologist (2; 1%). Other participants included holistic nutritionists or wellness coaches (22; 11%) and healthcare students (10; 5%). The “Other” professionals group represented 26 participants (13%) and included educators (12; 6%) and chefs (6; 3%). Smaller proportions were registered nurses (4; 2%), and managers (2; 1%), while individual respondents identified as an advocate, and a physical therapist (1 each; 0.5%). Overall, if survey participants are grouped by the professional field they work in, 51% work in mental healthcare, while 37% are in the field of nutrition in one way or another. 12% were students, educators, and belonged to other professions.

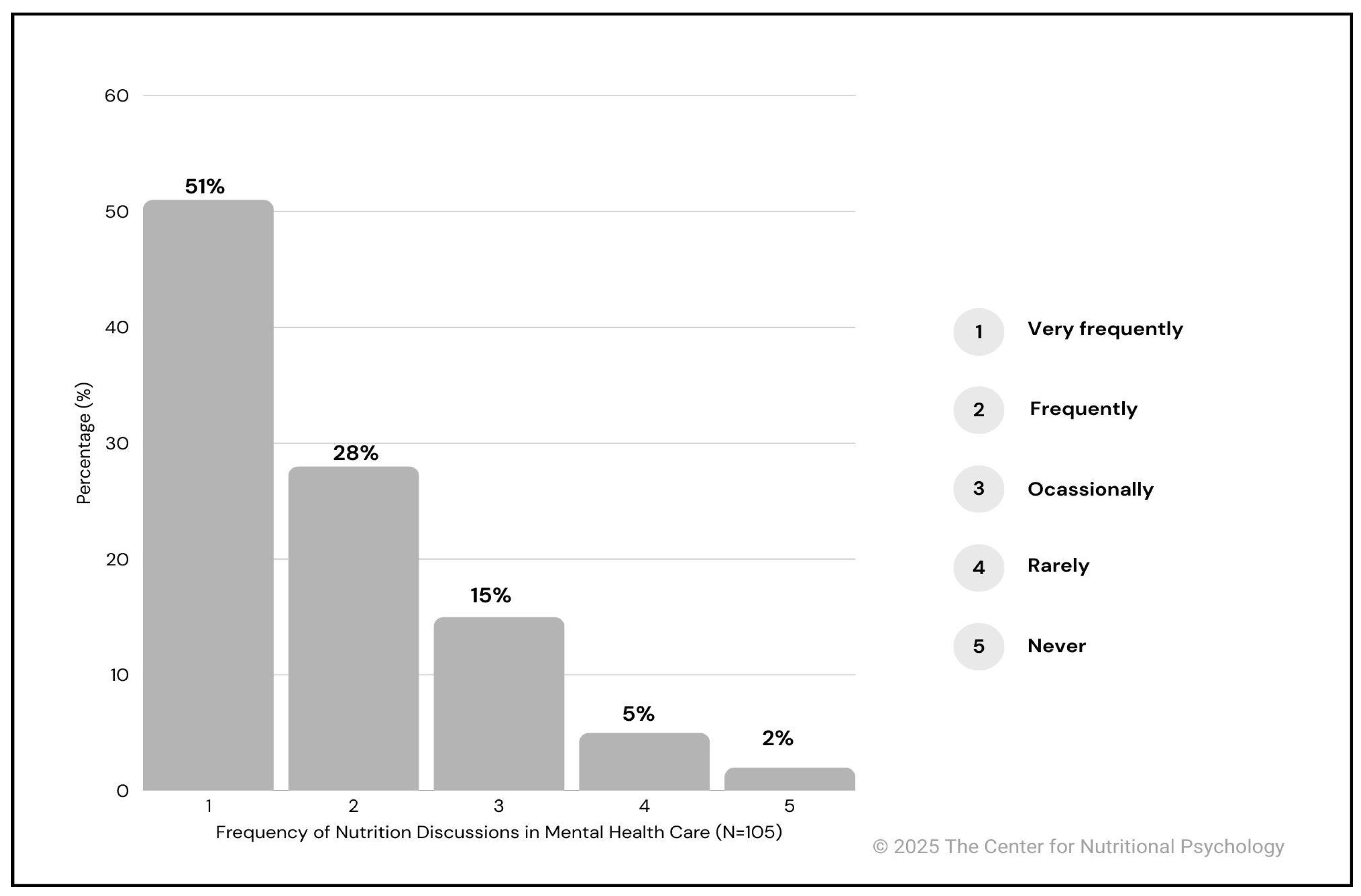

3.1. How Often Do Psychologists Address Nutrition, and Dietitians Address Mental Health?

Among participants who identified as psychologists or other mental health professionals (n = 105), 51% (n = 53) reported discussing nutrition very frequently in their clinical practice, and 28% (n = 29) reported doing so frequently. An additional 15% (n = 16) reported addressing nutrition occasionally, while 5% (n = 5) did so rarely. Only 2 participants (2%) reported never discussing nutrition in their sessions. These findings indicate that the vast majority of mental health professionals surveyed (98.1%) do address nutrition to some extent in clinical settings. Results are illustrated in

Figure 3.

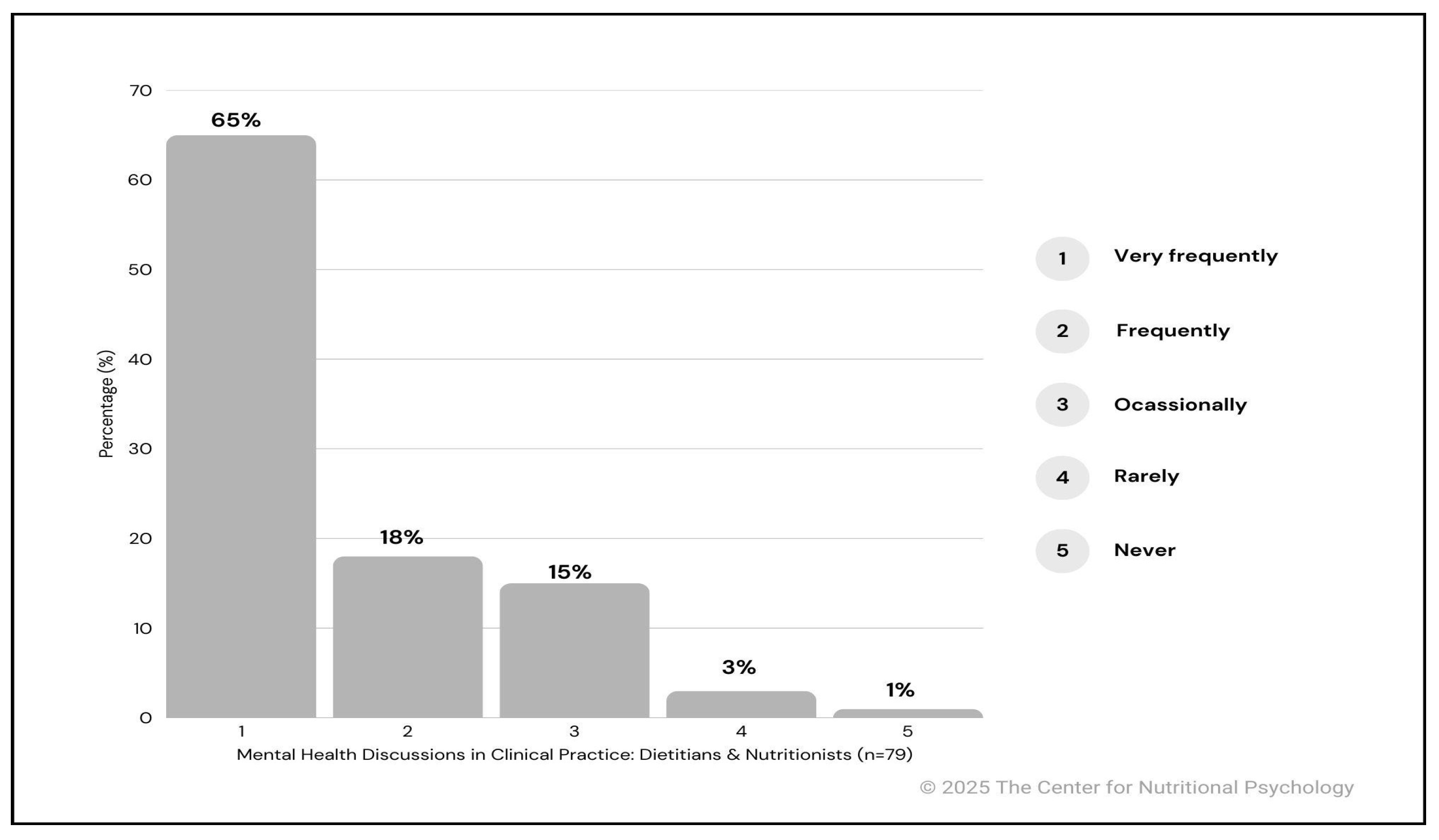

Conversely, among respondents identifying as dietitians or nutritionists (n = 79), the majority (98.7%) reported routinely addressing mental health in their clinical work. Specifically, 51 participants (65%) stated they do so very frequently, while 18 (23%) indicated they do so frequently. Only a small number of participants reported addressing mental health occasionally (7; 9%), rarely (2; 3%), or never (1; 1%). These data suggest that among nutrition professionals who do discuss mental health, most do so frequently or very frequently (88%). Results are presented in

Figure 4.

If the reported frequencies are treated as ordinal values and central tendencies of how often mental health professionals address nutrition are compared with how often nutrition specialists address mental health issues, results showed that nutrition specialists report addressing mental health issues (M=3.450, SD=0.790) a bit more often than mental health professionals report addressing nutrition (M=3.178, SD=1.004). However, the result of the Mann-Whitney U test comparing mean ranks of these two groups is not statistically significant, while the effect size indicates a small difference (U=2.611, p=.107, rᵣbis=0.138).

3.2. Formal and Informal Training and Interest in Nutrition Related to Mental Health

Despite growing interest, structured educational pathways in nutritional psychology remain limited. Among the respondents (n = 199), 44% (n = 87) reported having received no formal training. Among those who have received training, the most frequently reported forms were professional certificates or training programs (30%; n = 60), followed by graduate-level coursework (17%; n = 33). A smaller proportion reported having completed more than one undergraduate course (13%; n = 25), a single undergraduate course (12%; n = 24), or combinations of undergraduate and graduate training (4%; n = 7). Notably, a limited number of participants (5%; n = 10) indicated receiving both graduate education and professional certifications. Overall, while some professionals reported exposure to formal educational pathways, these findings underscore the persistence of a significant gap in structured nutrition training among those working in mental health fields.

Comparing mental health professionals and participants whose primary area of work is in the field of nutrition on the quantity of education in nutrition related to mental health, results show that the difference between the two groups is not statistically significant, while the difference size is practically 0 (see

Table 1). Comparing the two groups on the frequency of specific types of formal education, results again indicated no statistically significant differences between nutrition professionals and mental health professionals.

When asked, “If you had formal training and resources, would you incorporate nutritional psychology into your practice?”, of those respondents (n = 186), the vast majority (91%; n = 170) answered “Yes”, while 4% (n = 7) responded “Maybe”. Eight participants (4%) provided open-ended responses revealing three main themes:

Already practicing (3%; n = 6): Respondents reported incorporating nutritional psychology due to prior training or dual credentials.

Advocacy roles (0.5%; n = 1): One already worked to raise awareness and promote education on the topic.

Future intent (0.5; n = 1): One expressed interest in integration contingent on future training.

These findings point to a strong professional interest and a pressing need for formal training pathways.

Regarding informal training in nutrition related to mental health, a substantial portion of respondents reported engaging in self-directed learning. Specifically, 84% (n = 168) indicated being self-taught through resources such as books, research, or webinars, either alone or in combination with other forms of informal training. Additionally, 65% (n = 130) reported participation in non-degree workshops, online courses, or webinars. Informal mentoring or on-the-job professional experience was mentioned by 39% (n = 77) of respondents. In contrast, only a small fraction (7%; n = 14) reported having no informal training at all. These findings suggest that in the absence of structured academic pathways, many professionals turn to informal, self-guided, or experiential routes to acquire nutrition-related knowledge.

Comparing mental health and nutrition professionals in terms of the types and quantity of informal training related to mental health, the results again indicate no statistically significant or substantial differences. All Cramer’s V values are very low and close to 0 (see

Table 1), and none of them are statistically significant, although the percentage of participants from the field of nutrition reporting having each of the three types of informal education is higher compared to the percentage of participants from the field of mental health. Comparing the overall number of types of informal training reported (informal training quantity), the results of the U test are close to the conventional threshold of 0.05 (see

Table 1). At the same time, the effect size measure indicates a small difference.

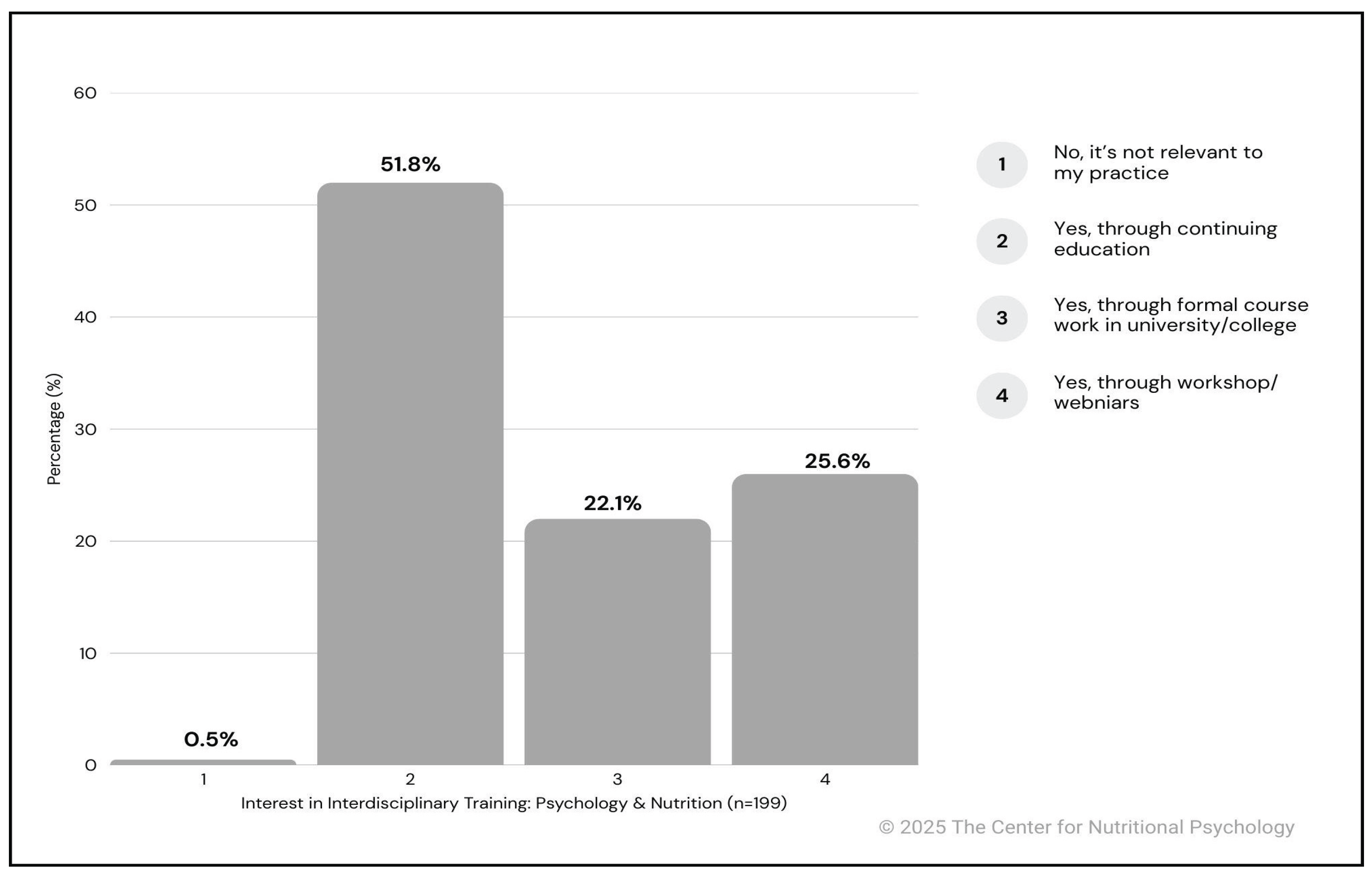

When asked whether they would be interested in evidence-based, interdisciplinary training bridging the psychological and nutritional sciences, 99.5% of respondents (n = 198) expressed a positive response. Over half of the sample (51.8%; n = 103) indicated interest in receiving such training through continuing education, followed by workshops or webinars (25.6%; n = 51) and formal academic coursework (22.1%; n = 44). Only one respondent (0.5%) reported that such training would not be relevant to their professional practice.

These results (see

Figure 5) highlight a strong and widespread interest in interdisciplinary education among professionals working in mental health and nutrition, reinforcing the need for accessible, structured programs to support integration between the two fields.

3.3. Perceived Barriers to Integrating Nutrition into Mental Health Care

Respondents were asked to rank seven predefined potential barriers to the integration of nutrition into mental health care on a scale from 1 (least important) to 7 (most important).

The most frequently cited barrier was the “Lack of training”, which received the highest average importance rating (M = 5.11, SD = 1.91). Notably, 54% of respondents (n = 88) ranked it as either the most important barrier (7) or the second most important (6), and 65% (n = 107) assigned it one of the top three ranks, highlighting a clear perception of insufficient formal education in this area. The “Unclear professional boundaries” also emerged as a major obstacle (M = 4.36, SD = 2.08), with 23.3% (n = 38) ranking it as the most important barrier and nearly 50% (n = 81) placing it within the top three ranks. Similarly, the “Limited access to nutrition resources” (M = 4.01, SD = 1.98) was considered highly relevant by respondents, with 28% (n = 45) ranking it in positions 6 or 7, and 43% (n = 68) placing it within the top three.

The “Time constraints in sessions” received a moderate level of concern (M = 3.45, SD = 1.97), with 24% (n = 38) of respondents rating it as the least important barrier (rank 1), and only 18% (n = 28) ranking it as a major concern (positions 6 or 7)

In contrast, the “Lack of evidence” was perceived as the least critical barrier (M = 2.98, SD = 2.14). A large portion of respondents, 39.0% (n = 60), ranked it as the least important, and over half (54.5%; n = 84) placed it in positions 1 or 2. Only 10.4% (n = 16) considered it the most important barrier, suggesting that most professionals do not view the scientific basis of nutritional interventions as a primary limitation.

Similarly, the “Lack of a common language” received limited concern overall (M = 3.84, SD = 1.95). While it showed a more even distribution across the scale, only 12.0% (n = 19) of respondents rated it as the most important barrier, and nearly 30% (n = 47) placed it in the bottom two positions.

Looking into the associations between how participants ranked specific barriers, exploratory factor analysis was conducted, treating the assigned ranks as ratings.

Loadings and eigenvalues of factors extracted from participants’ responses about barriers for integrating nutrition into mental health, treated as ratings, varimax rotation was applied and principal axis factoring

Professional barriers (factor 1) Resource barriers - factor 2 Uniqueness

Eigenvalues 22.90% 19.80%

Unclear professional boundaries 0.681 0.524

Lack of common language 0.597 0.607

Lack of training 0.584 0.613

Time constraint in sessions 0.380 0.823

Limited access to nutrition resources 0.936 0.093

Lack of evidence 0.431 0.778

Inspection of factor loadings indicates that participants seem to group ratings into two latent dimensions - professional barriers, represented primarily by unclear professional boundaries, lack of common language and training, and resource barriers, primarily represented by limited access to nutrition resources.

Table 3.

Barriers to integrating nutrition into mental health, as perceived by mental health and nutrition professionals.

Table 3.

Barriers to integrating nutrition into mental health, as perceived by mental health and nutrition professionals.

| |

Mental health professionals |

Nutrition professionals |

|

|

|

| |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD |

Mann-Whitney U statistic |

sig. |

rᵣbis |

| Lack of evidence |

2.965 (2.106) |

2.878 (2.157) |

2.168 |

0.774 |

-0.029 |

| Lack of training |

5.033 (1.917) |

5.094 (2.031) |

2.292 |

0.690 |

0.039 |

| Lack of common language |

3.809 (1.936) |

3.882 (2.113) |

2.234 |

0.877 |

0.016 |

| Unclear professional boundaries |

4.663 (2.034) |

4.038 (2.142) |

2.810 |

0.078* |

-0.175 |

| Time constraint in sessions |

3.178 (1.946) |

3.875 (2.049) |

1.736 |

0.054* |

0.197 |

| Limited access to nutrition resources |

4.022 (1.834) |

3.880 (2.387) |

2.391 |

0.696 |

-0.040 |

| Factor score - Professional barriers |

0.060 (0.968) |

-0.041 (1.122) |

2.092 |

0.655 |

-0.047 |

| Factor score - Resource barriers |

-0.025 (0.947) |

-0.015 (1.185) |

1.978 |

0.928 |

0.010 |

Comparing mental health and nutrition professionals in how they ranked specific barriers, results showed that the differences that are the closest to statistical significance are on unclear professional boundaries and time constraints in sessions (see

Table 2). More specifically, mental health professionals view unclear professional boundaries as more important than nutrition professionals. On the other hand, nutrition professionals see time constraints in sessions as a more important barrier than mental health professionals do.

These results collectively highlight that structural and educational gaps, rather than epistemological doubts, are the most prominent perceived obstacles to integrating nutrition into clinical mental health care.

In addition to ranking predefined barriers, respondents were also given the option to select one or multiple additional barriers from a multiple-choice list, and were invited to add open-text responses through an “Other (please specify)” field. These additional responses provided further insight into context-specific concerns not fully captured by the core ranking items. The most frequently cited concern was the risk of working outside one’s scope of practice, reported by 29% of respondents (n = 58), reflecting a broad awareness of ethical, legal, and professional boundaries when incorporating nutritional components into psychological care. Another commonly reported issue was a lack of confidence in nutrition knowledge, selected by 22% (n = 43), suggesting that many professionals feel underprepared to discuss or apply nutritional concepts in clinical settings. Similarly, ethical or liability concerns were endorsed by 23% (n = 45), pointing to perceived legal risks and responsibilities associated with offering advice in an area that may lie outside one’s formal expertise.

Practical concerns also emerged. Fear of confusing or overwhelming clients was reported by 21% of respondents (n = 41), while billing concerns were cited by 16% (n = 31), indicating that both communication complexity and financial feasibility may limit the willingness or ability to integrate nutritional strategies. Less frequently mentioned concerns included interdisciplinary overlap, lack of insurance coverage, the cost of food, and the difficulty of applying nutritional interventions in a personalized way, all of which were primarily captured through open-ended responses.

Notably, 30% of respondents (n = 60) reported having no specific concerns, indicating that a considerable proportion of professionals hold a favorable or at least neutral view toward the integration of nutrition into mental health care.

3.5. Education in Nutrition in Mental Health, Barriers, and Discussing Nutrition/Mental Health with Patients

When exploring correlations between the quantity of formal and informal education about nutrition in mental health with perceptions of barriers and frequency of discussing mental health (by nutrition professionals) or nutrition (by mental health professionals), results generally indicated that nutrition professionals with more training, either informal or formal (see

Table 4), about nutrition in mental health reported discussing mental health with their patients. Similarly, mental health professionals with more training of this type tended to report discussing nutrition with their patients more frequently. Among mental health professionals, the quantity of formal education was more strongly associated with the frequency of discussing nutrition in practice than the quantity of informal education. This may suggest that formal education in nutrition for mental health professionals makes them more confident to discuss nutrition in practice than informal education does.

Looking at barriers, results indicate that participants with more informal education tended to rate lack of evidence as a less important barrier. On the other hand, participants with more formal training tended to rate lack of training as a less important barrier to integrating nutrition into mental health.

3.6. Perceptions and Experiences of Interprofessional Collaboration

When asked whether interprofessional collaboration between mental health and nutrition professionals would improve patient outcomes, the vast majority of respondents expressed a strongly positive view. Specifically, 87% (n = 170) reported they strongly agree, and 12% (n = 22) stated they agree. Only 1% (n = 2) were neutral, none expressed disagreement, and just 1 participant (0.5%) expressed strong disagreement.

These findings reflect a nearly unanimous consensus among respondents regarding the perceived benefit of integrated care approaches, reinforcing the notion that interdisciplinary collaboration is not only desirable but considered crucial for improving clinical effectiveness.

Despite this clear consensus on the potential benefits of collaboration, actual experience in collaborative practice was more varied. While 26% (n = 42) reported collaborating with a dietitian or nutritionist regularly, and 26% (n = 41) reported doing so occasionally, nearly half of the respondents (48%; n = 78) had never collaborated in patient care, though 56 of them (35%) indicated that they would like to.

Among those who reported past or ongoing collaboration, qualitative responses revealed a wide range of modalities. The most commonly reported forms included shared care planning, client referrals, joint sessions, and interdisciplinary consultation. Additional examples included co-development of treatment plans, participation in multidisciplinary team meetings, informal knowledge exchange, and collaboration in educational or community-based programs. These narratives underscore the diversity of existing collaborative practices and suggest substantial openness among professionals to integrated models of care.

These results highlight a strong perceived value of interdisciplinary collaboration and a clear interest in expanding such partnerships, although opportunities for direct collaborative practice remain limited for many professionals.

4. Discussion

This study examined the current landscape of interdisciplinary integration between mental health and nutrition professionals by analyzing self-reported training, clinical practices, perceived barriers, and interest in collaborative care models. The findings highlight a strong and widespread professional interest in bridging psychological and nutritional sciences, despite limited access to structured educational pathways and relatively infrequent interprofessional collaboration in practice.

A central finding concerns the lack of formal training in nutritional psychology across professional groups. The extent of this lack was similar among groups of mental health professionals and nutrition professionals. Over 44% of respondents reported no formal education in the complementary field, and the most common form of training consisted of non-degree certificates or workshops. While only a minority had completed graduate-level coursework or comprehensive academic programs, a large proportion (86%) reported engaging in self-directed learning, such as reading, online webinars, and informal mentoring, indicating a strong intrinsic motivation to acquire relevant knowledge. These findings are consistent with previous studies [

14,

17] that have identified a persistent gap between professional interest and institutional support. Notably, 99.5% of respondents expressed interest in evidence-based interdisciplinary training, confirming a clear unmet educational demand. Results also show a correlation between the quantity of training in the complementary field and the frequency with which they discuss it in their practice. The more training participants had, the more likely they were to discuss the topics from the complementary field.

Despite the lack of formal preparation, the majority of psychologists and other mental health professionals (98.1%) reported addressing nutrition to some extent in clinical sessions, and nearly all nutritionists (98.7%) reported discussing mental health. These findings suggest that professionals on both sides already recognize the relevance of integration and are attempting to implement it within their current scope, albeit informally. However, this widespread engagement also raises concerns about competence and boundaries, as many operate without standardized training or collaborative frameworks.

Barriers to integration were reported at both systemic and subjective levels. The most critical barrier was the lack of training, followed by unclear professional boundaries and limited access to nutrition-related resources. These were perceived as more significant than concerns about time constraints or the scientific basis of nutritional psychology, which were rated as the least relevant obstacles. This suggests that the conceptual legitimacy of nutritional interventions in mental health care is largely accepted, and that the main barriers lie in practical implementation, role clarity, and infrastructure. Analysis showed that these barriers can be grouped into professional barriers and resource barriers. Nutrition professionals and mental health professionals perceived these barriers as similarly important. However, mental health professionals viewed unclear professional boundaries as a more important barrier compared to nutrition professionals, but nutrition professionals viewed a lack of time in a session as a more important barrier compared to mental health professionals.

Additional concerns emerged from open-ended responses and included the risk of operating outside one’s professional scope (29%), low confidence in nutrition-related knowledge (22%), legal or ethical concerns (22%), and fear of confusing or overwhelming clients (21%). Billing and insurance issues were also reported (15%), underscoring how financial and regulatory contexts shape clinical feasibility. These concerns reveal both personal uncertainty and structural limitations and point to the need for clear, interdisciplinary guidelines that protect professional roles while fostering cooperation.

While nearly all participants (99%) believed that collaboration between psychologists and nutritionists could improve patient outcomes, fewer than half reported any past collaborative experience, and only 26% reported engaging in regular interprofessional care. This striking discrepancy between perceived value and actual implementation underscores the need for institutional support, defined pathways, and accessible models of collaboration. Nonetheless, among those who had collaborated, qualitative responses indicated a rich diversity of modalities, including shared care planning, referrals, joint sessions, co-treatment, and informal consultations, demonstrating that integrated practice is both feasible and, in some cases, already well-established.

These findings point toward a clear set of priorities for advancing a coherent model of integrated care. As a foundational step, the development of structured and evidence-based interdisciplinary educational and training programs, ranging from foundational workshops to advanced academic curricula, is crucial to bridging the current educational gap and ensuring ethical and competent practice. Equally important is the clarification of professional boundaries and scopes of practice through the publication of joint guidelines by regulatory bodies and professional associations. Establishing a shared clinical language, promoting interdisciplinary supervision models, and creating institutional infrastructures that support co-treatment and referral pathways would further facilitate collaborative implementation. Policy-level interventions, including reimbursement reform and expanded insurance coverage, are also necessary to remove structural barriers and ensure the financial sustainability of integrated care. Finally, future research should evaluate the impact of these interventions on patient outcomes, team functioning, and healthcare efficiency. In summary, the results of this study can serve as a roadmap to guide the development of structured, sustainable, and ethically sound models for integrating psychological and nutritional care.

5. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the data were based on self-reports, which introduces the possibility of recall bias and social desirability effects. It is also likely that respondents with a pre-existing interest in the integration of nutrition and mental health were more inclined to participate, potentially inflating estimates of engagement or enthusiasm. Second, the sample was not stratified by region, level of experience, or practice setting, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Third, while open-text responses were rich and thematically informative, they were analyzed using topic modeling and manual categorization, without formal qualitative coding procedures; therefore, they should be interpreted as exploratory. Finally, the cross-sectional design does not allow for causal inferences regarding the impact of training or collaboration on clinical outcomes.

Despite these limitations, the study offers a comprehensive overview of current attitudes, experiences, and perceived needs among professionals working at the intersection of nutrition and mental health. The results highlight not only a substantial readiness for interdisciplinary integration but also concrete educational, systemic, and regulatory gaps that must be addressed to translate interest into effective clinical practice.

6. Conclusions

This study provides an updated overview of how professionals in the fields of nutrition and mental health perceive, implement, and envision interdisciplinary collaboration. The findings reveal a clear mismatch between strong professional interest in integration and the limited availability of formal training and structured collaborative opportunities. While many practitioners are already engaging in cross-disciplinary conversations and interventions, often driven by self-education or informal partnerships, significant gaps remain in terms of educational infrastructure, institutional support, and role clarity.

The near-unanimous consensus on the benefits of collaboration underscores the urgency of developing accessible, evidence-based training pathways that prepare professionals to work across disciplinary boundaries without compromising ethical standards or professional identity. Furthermore, the range of collaborative modalities already in use, despite systemic barriers, suggests a strong foundation on which more formalized, sustainable models of integrated care could be built.

Future efforts should focus on creating accredited interdisciplinary curricula, clarifying professional scopes of practice, and supporting institutional policies that facilitate team-based approaches. By addressing these areas, the field can move from isolated efforts to a coherent and effective model of nutritional-psychological integration in clinical care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G., V.H., and E.M.; Methodology, R.G., V.H., and E.M.; Validation, R.G., V.H., and E.M.; Formal Analysis, R.G., V.H., and E.M.; Investigation, R.G., V.H., and E.M.; Resources, R.G., V.H., and E.M.; Data Curation, R.G., V.H., and E.M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, R.G., V.H., and E.M.; Writing—Review and Editing, R.G., V.H., and E.M.; Visualization, R.G., V.H., and E.M.; Supervision, R.G., V.H., and E.M.; Project Administration, R.G., V.H., and E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Vladimir Hedrih’s work on the study was supported by the project of the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Niš, Serbia - Popularization of science and scientific publications in the sphere of psychology and social policy, project number 423/1-3-01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it represents a secondary analysis of data collected by the Center for Nutritional Psychology (CNP).

Informed Consent Statement

This study represents a secondary analysis of data previously collected by the Center for Nutritional Psychology (CNP). Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the original data collection.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors. Due to privacy restrictions, raw survey responses cannot be publicly shared.

Conflicts of Interest

The Center for Nutritional Psychology provides training in the field of nutritional psychology. No financial or contractual arrangements influenced the design, analysis, or reporting of this study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CNP |

Center for Nutritional Psychology |

| CBT-IE |

Interprofessional Enhanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| CBT |

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| ACT |

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy |

| LPCCs |

Licensed Professional Clinical Counselors |

| LMFTs |

Licensed Marriage and Family Therapists |

| LMHCs |

Licensed Mental Health Counselors |

| NBCCs |

National Board for Certified Counselors |

References

- Banta, J.E.; Segovia-Siapco, G.; Crocker, C.B.; Montoya, D.; Alhusseini, N. Mental Health Status and Dietary Intake among California Adults: A Population-Based Survey. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2019, 70, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Głąbska, D.; Guzek, D.; Groele, B.; Gutkowska, K. Fruit and Vegetable Intake and Mental Health in Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neil, A.; Quirk, S.E.; Housden, S.; Brennan, S.L.; Williams, L.J.; Pasco, J.A.; Berk, M.; Jacka, F.N. Relationship between Diet and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Am J Public Health 2014, 104, e31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teasdale, S.B.; Ward, P.B.; Samaras, K.; Firth, J.; Stubbs, B.; Tripodi, E.; Burrows, T.L. Dietary Intake of People with Severe Mental Illness: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2019, 214, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firth, J.; Marx, W.; Dash, S.; Carney, R.; Teasdale, S.B.; Solmi, M.; Stubbs, B.; Schuch, F.B.; Carvalho, A.F.; Jacka, F.; et al. The Effects of Dietary Improvement on Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Psychosom Med 2019, 81, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horovitz, O. Nutritional Psychology: Review the Interplay Between Nutrition and Mental Health. Nutrition Reviews 2025, 83, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacka, F.N. Nutritional Psychiatry: Where to Next? EBioMedicine 2017, 17, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Petersen, K.S.; Hibbeln, J.R.; Hurley, D.; Kolick, V.; Peoples, S.; Rodriguez, N.; Woodward-Lopez, G. Nutrition and Behavioral Health Disorders: Depression and Anxiety. Nutrition Reviews 2021, 79, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, H.R. Nutrition, Brain Function and Cognitive Performance. Appetite 2003, 40, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, L.B.; Braga Tibães, J.R.; Sanches, M.; Jacka, F.; Berk, M.; Teixeira, A.L. Nutrition-Based Interventions for Mood Disorders. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 2021, 21, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melzer, T.M.; Manosso, L.M.; Yau, S.-Y.; Gil-Mohapel, J.; Brocardo, P.S. In Pursuit of Healthy Aging: Effects of Nutrition on Brain Function. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sochacka, K.; Kotowska, A.; Lachowicz-Wiśniewska, S. The Role of Gut Microbiota, Nutrition, and Physical Activity in Depression and Obesity-Interdependent Mechanisms/Co-Occurrence. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroebele-Benschop, N.; Hedrih, V.; Behairy, S.; Pervaiz, N.; Morphew-Lu, E. Conceptual Framework for Nutritional Psychology as a New Field of Research. Behavioral Sciences 2025, 15, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litta, A.; Nannavecchia, A.M.; Ferrandina, M.; Favia, V.; Minò, M.V.; Vacca, A. Nutrition in Mental Health: Insight from a Survey Among Psychiatrists and Psychologists. Psychiatr Danub 2024, 36, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mörkl, S.; Stell, L.; Buhai, D.V.; Schweinzer, M.; Wagner-Skacel, J.; Vajda, C.; Lackner, S.; Bengesser, S.A.; Lahousen, T.; Painold, A.; et al. “An Apple a Day”?: Psychiatrists, Psychologists and Psychotherapists Report Poor Literacy for Nutritional Medicine: International Survey Spanning 52 Countries. Nutrients 2021, 13, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stromsnes, W. Nutrition Counseling Practices Among Psychologists. University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations 2024, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Stenz, C.F.H.; Jansen, K.L. Nutrition and Depression: Collaboration between Psychologists and Dietitians in Depression Treatment. Translational Issues in Psychological Science 2023, 9, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, M.; Heruc, G.; Byrne, S.; Wright, O.R.L. Collaborative Dietetic and Psychological Care in Interprofessional Enhanced Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Adults with Anorexia Nervosa: A Novel Treatment Approach. J Eat Disord 2023, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basri, H.; Al-Waadh, M.; Mohammed, Z. From Margins to Mainstream: Making Psychological Interventions for the Treatment of Obesity and Weight Management Core to NHS Primary Care. Cureus 2025. [CrossRef]

- The Center for Nutritional Psychology. Available online: https://www.nutritional-psychology.org/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Rich, K.; Murray, K.; Smith, H.; Jelbart, N. Interprofessional Practice in Health: A Qualitative Study in Psychologists, Exercise Physiologists, and Dietitians. Journal of Interprofessional Care 2021, 35, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).