Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. California Coastal Plan and Seawater Desalination Permitting

For each new or expanded coastal powerplant or other industrial installation using seawater for cooling, heating, or industrial processing, the best available site, design, technology, and mitigation measures feasible shall be used to minimize the intake and mortality of all forms of marine life.

The regional water board shall consider the following factors in determining feasibility of subsurface intakes:

- geotechnical data, hydrogeology, benthic topography, oceanographic conditions, presence of sensitive habitats,

- presence of sensitive species, energy use for the entire facility;

- design constraints (engineering, constructability), and

- project life cycle cost.

“Subsurface intakes shall not be determined to be economically infeasible solely because subsurface intakes may be more expensive than surface intakes. Subsurface intakes may be determined to be economically infeasible if the additional costs or lost profitability associated with subsurface intakes, as compared to surface intakes, would render the desalination facility not economically viable.”

2.2. Formation of a Panel to Evaluate Feasibility of Using Subsurface Intake Designs

- How should a proposed desalination permit applicant complete this analysis? (e.g., what is the process to be followed consistent with the terms in the Ocean Plan 2019, Chapter III, Section M?)

- What modeling is necessary for determining SSI feasibility? (e.g., what groundwater modeling will be needed to assess potential impacts to aquifers near the site for a given SSI and/or to SSI support design requirements [e.g., well spacing and numbers, infiltration rate and gallery size]?)

- What components of a geophysical survey (including lithologic data) are needed to determine SSI feasibility?

- What key characteristics should be considered for the known SSI technology types? What are known information gaps in SSI technologies?

- What criteria should be used to determine whether additional data collection is necessary? (e.g., what level of accuracy is needed to define key system design parameters that determine feasibility?)

- What metrics and criteria should be used to evaluate test-well data for subsurface feasibility? (e.g., how do test well data inform the need for and range of parameters to be used in groundwater modeling?)

- What readily available data can be used to evaluate a reasonable range of sites? (e.g., what should a project proponent search for to define a range of sites that will provide the desired water quantity and also will likely support an SSI?)

- What is a reasonable shelf life for various data types? (e.g., which type of data is likely variable over time requiring regular characterization?)

2.3. Panel Approach to Determining Feasibility

3. Results of the Panel Analysis

3.1. Subsurface Intake Systems Used for Seawater Desalination Plants

3.2. General Feasibility Factors Considered by the Panel

- • Technological: The project site and SSI combination should be capable of reliably providing the desired volume of desalinated water, sufficiently resilient against natural hazards such as sea level rise, capable of construction, and should have no deleterious impacts on local aquifers or wetlands.

- • Environmental: Construction of the SSI system should not result in unacceptable impacts to sensitive habitats and species within the zone of influence of the SSI footprint, including the indirect impacts that might result in damage to coastal freshwater aquifer dependent habitat and associated species and must avoid location near Marine Protected Areas (MPA) and State Water Quality Protection Areas (SWQPAs).

- • Economic: Capital and life cycle costs should be within a range that allows for likely available financing of the project. Typically, capital costs for SSIs are higher than open ocean intakes but these costs can be offset by lower operating costs and potential in other costs (e.g., disposal of treatment plant residuals). These benefits of SSI use would be incorporated into the life cycle cost analysis.

- • Social: Water supply affordability is the chief issue of social impact concern. Any incremental life cycle costs associated with SSIs (relative to other intake options) should not result in an undue economic burden on communities.

3.3. Policy Recommendations

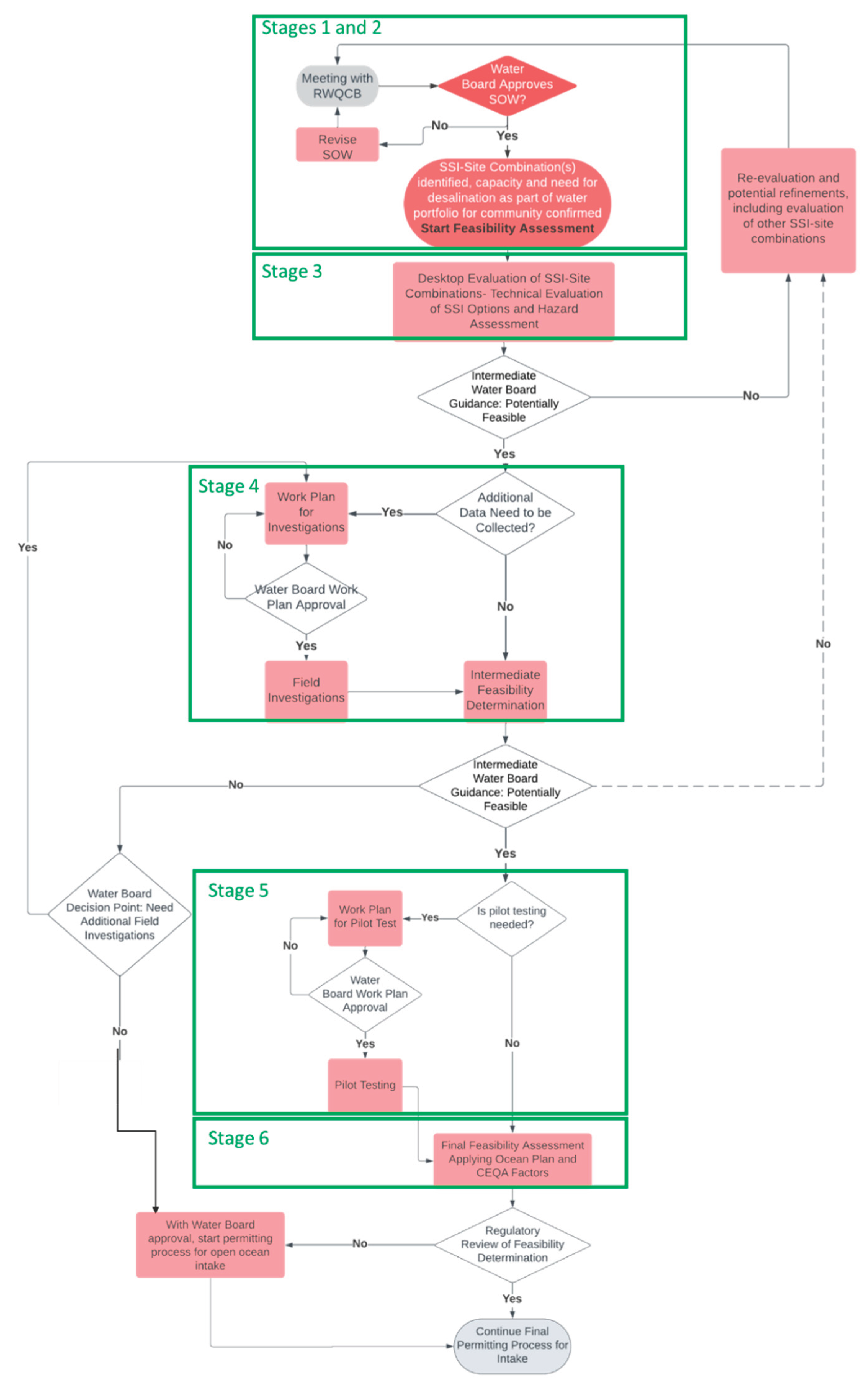

- Obtaining a permit from the Regional Water Boards for a desalination project in California requires a project proponent to complete multiple tasks before receiving a Regional Water Board Water Code section 13142.5(b) determination under Chapter III.M.2.a.(1) of the Ocean Plan. The completion of these tasks may take several years. Thus, the Panel recommends that the evaluation of SSIs be streamlined for completion within a maximum of three years. Given that preceding tasks will constrain the intake capacity, site, and applicable SSI combinations to be evaluated in the FA step, this recommended duration should be achievable absent the need for scaled pilot tests with the assumption that regional boards will have sufficient resources to provide interim guidance at identified transition points with the six proposed stages of the FA process (See Figure 1).

- Life cycle costs and thus unit prices for water delivered by a desalination plant will likely be higher than costs for other sources of water supply based on the experience of Panel members. In some cases, life cycle costs comparing open intakes with SSI may be lower due to lower pretreatment costs prior to membrane treatment (i.e., reverse osmosis) and other factors. However, the use of a SSI may increase overall life cycle costs and uncertainty, given their relatively limited application at a scale above 38,000 m3/d (10 MGD) of produced water and associated financial risk. These economic consequences may pose significant challenges to obtain financing for desalination facilities with hydraulic capacities exceeding this scale. One option that could be considered by the State is to provide some form of financial instrument that would mitigate the financial risks associated with early adopters using SSIs at scales larger than 38,000 m3/d.

- Recent policies from several agencies addressing environmental justice concerns over water rates require that any permit applicant must conduct an affordability assessment to evaluate the impacts of incremental increases in costs on low-income ratepayers. This will need to be considered in any future amendments to the Ocean Plan.

- Given the potential for subsurface connectivity between coastal wetlands or coastal freshwater aquifers and SSI source waters, the Panel recommends that this concern receive careful consideration both during the analyses conducted in the FA and during post-construction monitoring of source-water salinity. Regular reporting on source-water salinity should be required in any plant operating plan if there is a risk of impacts inferred from groundwater modeling studies of the site-SSI combination.

4. Discussion

4.1. Difficulties Obtaining Environmental Permits for Construction of Desalination Plants in California

4.2. Seawater Desalination: Water Sustainability and Resilience in California

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reisner, M. Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water. Penguin Books, New York, 1986.

- Carle, D. An introduction to water in California. University of California Press, Berkley, CA, 2004.

- Hanak, E.; Lund, J.; Dinar, A.; Gray, B.; Howitt, R.; Mount, J.; Moyle, P.; Thompson, B. Managing California’s Water: From Conflict to Reconciliation. Public Policy Institute of California, San Francisco, CA, 2011.

- Poland, J.F.; Lofgren, B.E.; Ireland, R.L.; Pugh, R.G. Land subsidence in the San Joaquin Valley, California, as of 1972. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 437-H, 78 pp., 1975. http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/pp437H.

- Bean, R.T. Pioneering field study of hydro compaction in the San Joaquin Valley, In Land Subsidence ― Case Studies and Current Research; Borchers, J.W., Ed.; Proceedings of the Dr. Joseph F. Poland Symposium on Land Subsidence, Association of Engineering Geologists Special Publication 8, 1998, 37-44.

- Smith, R.G.; Majumdar, S. 2020. Groundwater storage loss associated with land subsidence in western United States mapped using machine learning. Water Resourc. Res. 2020, 56 (7), e2019WR026621.

- MacDonald, G.M. Severe and sustained drought in southern California and the West: Present conditions and insights from the past on causes and impacts. Quaternary International 2007, 11, 173-174. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, G.M.; Kremenetski, V.; Hidalgo, H.C. Southern California and the perfect drought: Simultaneous prolonged drought in southern California and the Sacramento and Colorado River systems. Quaternary International 2008, 188(1), 11-23.

- MacDonald, G.M.; Rian, S.; Hidalgo, H.C. Southern California and “The Perfect Drought”. In Colorado River Basin Climate. California Department of Water Resources. Sacramento, California, 2008.

- Woodhouse, C.A.; Meko, D.M.; Bigio, E.R. A long view of southern California water supply. J. Am. Water Res. Assoc. 2020, 4, 212-229.

- Gleick, P.H. Safeguarding our water - making every drop count. Sci. Am. 2001, 284(2), 40-45.

- Perry C. Accounting for water; stocks, flows, and values. In Inclusive wealth report 2012 measuring progress toward sustainability, Edited by UNU-IHPD and UNEP, pp. 215–230, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2012. https://europa.eu/capacity4d ev/file/11228/download?token=hF31YA_j.

- Badiuzzaman, P.; McLaughlin, E.; McCauley, D. Substituting freshwater: Can ocean desalination and water recycling capacities substitute for groundwater depletion in California. J. Environ. Manage. 2017, 201, 123-135.

- Heokstra, A.Y. The Water Footprint of Modern Consumer Society. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020.

- Griffin, D.; Anchukaitis, K.J. How Unusual is the 2012–2014 California Drought?. Geophys. Res. Letters 2014, 41(24), 9017–9023. [CrossRef]

- Lund, J.; Medellin-Azuara, J.; Durand, J.; Stone, K. Lessons from California’s 2012–2016 drought. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manage. 2018, 144, 2012–2016. [CrossRef]

- Stine, S. Extreme and persistent drought in California and Patagonia during medieval time. Nature 1994, 369, 546-549.

- Jones, T.L.; Brown, G.; Raab, L.M.; McVicar, J.; Spaulding, G.; Kennett, D.J.; York, A.; Walker, P.L. Environmental imperatives reconsidered: Demographic crisis in western North America during the Medieval Climate Anomality. Current Anthropology 1999, 40, 137-156.

- Jones, T.L. Late Holocene cultural complexity along the California coast. In Catalysts to Complexity: Late Holocene Societies of the California Coast. Erlandson, T.M.; Jones, J.L., Eds. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, pp. 1-12, 2002.

- Case, R.A.; MacDonald, G.M. Tree ring reconstruction of streamflow for three Canadian Prairie rivers. J. Am . Water Res. Assoc. 2003, 39, 703-716.

- Kennett, D.J.; Kennett, J.P. Competitive and cooperative responses to climate instability in southern California. Am. Antiquity 2000, 65, 379-393.

- Arnell, N.W.; Gosling, S.N. The impacts of climate change on river flood risk at the global scale. Climatic Change 2016, 134, 387–401. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Mishra, A.; Trenberth, K.E. Climate change and drought: a Perspective on drought indices. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2018, 4, 145–163. [CrossRef]

- Gleick, P.H.; Haasz, D.; Henges-Jeck, C.; Srinivasan, V.; Wolff, G.; Cushing, K.K.; Mann, A. Waste Not, Want Not: The Potential for Urban Water Conservation in California. Pacific Institute for Studies in Development, Environment, and Security, Oakland, CA, 2003.

- Gleick, P.H.; Cooley, H.; Groves, D. California Water 2030: An Efficient Future. Pacific Institute for Studies in Development, Environment, and Security, Oakland, CA, 2005.

- Missimer, T.M.; Danser, P.A.; Amy, G.L.; Pankratz, T. Analysis of a water crisis: The metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia Regional water supply conflict. Water Policy 2014, 16, 669-689. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, K.; Yamada, R.; Callahan, N.V.; Bianes, V.; Chamberlain, D.; Suydam, T.; Raton, G. Integrating desalinated seawater with existing supplies and delivery systems. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 2014, 106(2), 58-63.

- McFarland, P.H. Water industry veteran pivotal in fate of milestone desalination plant. Engin. News-Record 2016, 275(19), 34.

- Cooley, H.; Gleick, P.H.; Wolff, G. Desalination, with a Grain of Salt: A California Perspective. Pacific Institute for Studies in Development, Environmental, and Security, Oakland, CA, USA, 100 pp., 2006.

- Cooley, H.; Heberger, M. Key issues in seawater desalination in California: Energy and greenhouse gas emissions. Pacific Institute for Studies in Development, Environmental, and Security, Oakland, CA, USA, 2013.

- Miller, S.; Shemer, H.; Semlat, R. Energy and environmental issues in desalination. Desalination 2015, 316, 2-8.

- Heihsel, M.; Lenzen, M.; Malik, A.; Geschke, A. The carbon footprint of desalination, Desalination 2019, 454, 71-81.

- Lattemann, S.; Höpner, T. Environmental impact and impact assessment of seawater desalination. Desalination 2008, 220, 1-15.

- Cooley, H.; Ajam, N.; Heberger, M. Key Issues in Seawater Desalination in California: Marine Impacts. Pacific Institute for Studies in Development, Environmental, and Security, Oakland, CA, USA, 2013.

- California Water Boards. Desalination Facilities Intakes, Brine Discharges, and the Incorporation of Other Non-substantive Changes. Environmental Protection Agency, Sacramento, CA, USA, 2014.

- Shahabi, M.P.; McHugh, A.; Anda, M.; Goen, H. Environmental life cycle assessment of seawater reverse osmosis desalination plant powered by renewable energy. Renew. Energy 2012, 67, 53-58.

- Missimer, T. M.; Maliva, R.G. Environmental issues in seawater RO desalination: Intakes and outfalls. Desalination 2017, 434, 198-215. [CrossRef]

- Missimer, T.M.; Jones, B.; Maliva, R.G. Intakes and Outfalls for Seawater Reverse Osmosis Desalination Facilities: Innovations and Environmental Impacts. Springer, Dordecht, The Netherlands, 2015.

- Roberts, P.J.W.; Ferrier, A.; Daviero, G.J. Mixing in inclined dense jets. J. Hydraul. Eng. Div. Am. Soc. Civil Eng. 1997, 123(8), 693-699.

- Roberts, P.J.W. Near field dynamics of concentrate discharges and diffuser design. In Intakes and Outfalls for Seawater Reverse Osmosis Desalination Facilities: Innovations and Environmental Impacts; Missimer, T.M.; Jones, B.; Maliva, R.G., Eds. Springer, Dordecht, The Netherlands, pp. 369-396, 2015.

- El Saliby, J.; Okour, Y.; Shon, H.K.; Kandasamy, J.; Kim, I.S. Desalination plants in Australia, review and facts. Desalination 2009, 247, 1-13.

- Palmer, N. Changing perception of the value of urban water in Australia following investment in seawater desalination. Desal. Water Treat. 2012, 43, 298-307. [CrossRef]

- Crisp, G. P. Desalination and water reuse-sustainably drought proofing Australia. Desal. Water Treat. 2021, 42(1-3), 323-332.

- Denson, T. Desalination and California’s Water Problem: The Viability of the Desalination Industry Through the Lens of California’s New Desalination Rules and Development. Georgetown Law Center, Washington, D.C., 2016. https://gielr.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/zsk00416000713.pdf.

- Missimer, T.M. The California Ocean Plan: Does it eliminate the development of large-capacity SWRO plants in California? Proceedings, American Membrane Technology Association/American Water Works Association, 2016 Membrane Technology Conference & Exposition, San Antonio, Texas, Feb. 1-5, 2016.

- Bittner, R.; Kavanaugh, M.; Feeney, M.; Maliva, R.G.; Missimer, T.M. Technical feasibility of subsurface intake designs for the proposed Poseidon water desalination facility at Huntington Beach, California. Independent Scientific Advisory Panel, California Coastal Commission and Poseidon Resources (Surfside) LLC Final Report, 2014.

- Bittner, R.; Clements, J.; Dale, L.; Lee, S.; Kavanaugh, M.; Missimer, T.M. Phase 2 report: Feasibility of subsurface intake designs for the proposed Poseidon water desalination facility at Huntington Beach, California. Independent Scientific Advisory Panel, California Coastal Commission and Poseidon Resources (Surfside) LLC Final Report, 2015.

- California Environmental Protection Agency (Ocean Plan). California Ocean Plan. State Water Resources Control Board, 1001 I Street, Sacramento, CA, USA, 2019.

- State of California. California’s Water Supply Strategy: Adapting to a Hotter, Drier Climate. 2022. Online at: https://resources.ca.gov/-/media/CNRA-Website/files/initiatives/water-resilience/CA-water-supply-strategy.pdf.

- California Department of Water Resources. California Water Plan Update, 2023. Online at : https://water.ca.gov/Programs/California-Water-Plan/Update-2023.

- Clements, J.; Kavanaugh, M.C.; Largier, J.L.; Maliva, R.G.; Missimer, T.M.; L. Moulton-Post, L.; Stokes-Draut, J.R. Final desalination subsurface intake panel report. Prepared by the Subsurface Intake Expert Panel and Facilitated and convened by Concur, Inc., 2024.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Water and climate change. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2020. UNESCO, Paris, France. Online: https://repository.unescap.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/f2446069-c3a0-42bf-bc88-3e655ff3b2e1/content.

- Yang, Y.C.E.; Son, K.; Hung, F.; Tidwell, V. Impact of climate change on adaptive management decisions in the face of water scarcity. J. Hydrology 2020, 588, 125015. [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M. Global water shortage and potable water safety; Today’s concern and tomorrow’s crisis. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106936. [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L.; Sangiorgio, M. Global water gaps under future warming levels. Nature Communications, 2025, 16, 1192. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, G.M. Water, climate change, and sustainability in the southwest. PNAS 2020, 107(50), 21,256-21,262. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.K.; Zhu, T.; Lund, J.R.; Howitt, R.E.; Jenkins, M.W.; Pulido, M.A.; Tauber, M.; R.S. Ritzema, I.C. Ferreira. Climate warming and water management adaptation for California, Climatic Change 2006, 76, 361-387. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, K.G.; Udall, B.; Wang, J.; EKuhn, E.; Salehabadi, H.; Schmidt, J.C.. What will it take to stabilize the Colorado River? Science 2022, 377, 373–375.

- Richter, B.D.; Lambhir, G.; Marston, L.; Dhakal, S.; Sangha, L.S.; Rushforth, R.R.; Wei, D.; Ruddell, B.L.; Davis, K.F.; Hernandez-Cruz, A.; Sandoval-Solis, S.; Schmidt, J.C. New water accounting reveals why the Colorado River no longer reaches the sea. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 134.

- Overpeck, J.; Udall, J.B. Climate change and the aridification of North America. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11856–11858.

- Udall, B.; Overpeck, J. The twenty-first century Colorado River hot drought and implications for the future. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 2404–2418.

- Womble, P.; Gorelick, S.M.; Thompson, Jr., B.H.; Hernandez-Suarez, J.S. A strategic environmental water rights market for Colorado River allocation. Nature Sus. 2025, 8, 925-935. [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.A. Los Angles water supply impacts from a M7.8 San Andres Earthquake scenario. AQUA – Water Infrastructure Systems, Ecosystems, and Society, 2010, 59(6,7), 408. [CrossRef]

| Intake Type | Description |

| Beach wells | Shallow vertical wells producing from beach or shallow rock deposits |

| Horizontal or Ranney collector well | A large diameter caisson from which lateral perforated spokes are advanced out from the caisson toward or under a proximate water body |

| Slant or angle wells | Wells drilled at an angle from the shore under an adjacent water body to induce downward flow in the well through the overlying sediments. |

| Horizontal wells | Shallowly buried screens fanning out beneath the seafloor installed by directional drilling from the shore. |

| Beach (surf zone) galleries | A slow sand filter that is constructed beneath the intertidal zone of the beach. |

| Seabed galleries or seabed infiltration galleries | A slow sand filter that is constructed beneath the subtidal zone. |

| Tunnel intakes |

Tunnel constructed underlying the beach area with a series of collectors, commonly drilled upward into the overlying aquifer |

| Factor Type | Feasibility Consideration |

|---|---|

| TECHNOLOGICAL | |

| Constructability | The site-SSI combination should be capable of providing the desired volume (capacity) of desalinated water. It must be physically possible to construct the system in the vicinity of the treatment plant. Physical conditions at the site should be stable enough so that the system could operate reasonably consistently over its planned lifetime (typically 30 years). Ability to obtain permits associated with the SSI from other agencies in a reasonable time (e.g., land use permits). |

| Reliability | The raw water must be of suitable quality, which is herein assumed to be similar to local seawater that has not undergone rock-fluid interactions that are averse to treatment processes (e.g., iron or manganese concentration increases). Ability of the intake to function and ability to access for O & M performance. Ability to rehabilitate the intake, for example to address clogging using known and proven technologies. |

| Risk of system failure | Owner of the system should have confidence that the SSI system will meet all design goals before committing to construction of a full-scale intake system and treatment plant. Pilot testing of the intake system should be conducted, if necessary. The system should not be vulnerable to adverse geological or human processes including sediment erosion and deposition and spills of chemicals that would affect the treatment process. Practical and affordable options should be available to maintain and repair the system if required. |

| ENVIRONMENTAL | SSI implementation (e.g., sitting, construction, maintenance) should avoid to the maximum extent feasible, the disturbance of sensitive habitats and native species, and ensure that the intake structures are not located within an MPA or SWPA. Specific environmental factors for feasibility in the Ocean Plan include sensitive habitats, sensitive species, and indirect effects, such as the SSI withdrawal of groundwater from a coastal freshwater aquifer or aquifer-dependent sensitive habitat (wetlands) and/or associated sensitive species that have a significant impact. |

| SOCIAL | Water affordability |

| ECONOMIC | Construction and operation (life cycle costs) costs for a given intake type should be competitive with other intake types and not be so high as to render a desalination project not economically viable. The perceived project engineering risk should be low enough that financing can be obtained (based on use of the technology at other comparable locations and at similar design capacities). Additional incremental life cycle costs associated with SSIs (relative to surface intakes or other water supply alternatives) should not cause an undue economic burden for low-income households in the form of significant increases in the cost of basic water services. Any additional incremental costs should also not result in delayed investments necessary to meet regulatory requirements that protect public health. The contractor market should be competitive with multiple potential bidders for projects. An SSI should not be significantly more energy intensive (i.e., have a greater carbon footprint) than other intake options based on annual energy use assessments. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).