1. Introduction

Since the 1990s, the amount of acreage devoted to transgenic maize cultivation has progressively increased. As of 2022, 15 countries cultivated transgenic maize across 66.2 million hectares, representing 32.9% of the global maize cultivation area [

1]. Genetically modified crops with insect resistance have been developed to efficiently manage target pests and decrease pesticide application [

2]. While transgenic maize offers many benefits, it may also pose various ecological and environmental concerns. The commercial introduction of transgenic maize has led to the need to assess the possible impacts of this technology on the environment, and among the likely undesirable impacts are the effects on non-target organisms [

3]. Some articls dealt with studies focused on arthropods at field and laboratory level [

4,

5,

6]. Some articles also exist of the effects on soil microorganisms [

7,

8] and soil-associated meso and macro-fauna [

9]. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct non-target organism biological assays on genetically modified corn before its large-scale commercial cultivation.

E.annulipes belongs to the

Euborellidae family within the Dermaptera order and is globally distributed. It is the most widespread species within the Dermaptera order [

10]. They are nocturnal creatures that hide in small caves, in crevices, or beneath rocks or debris during the day. Males and females can be distinguished from each other by the pincers at the end of their abdomen. This highly voracious nocturnal predator consumes prey from various insect orders, including Diptera [

11,

12], Hemiptera [

13], Lepidoptera [

14,

15], and Coleoptera [

16], making it a promising candidate for biological control programs. In China,

E. annulipes has been detected in more than ten provinces. As omnivorous animals, they prey on diverse prey in various crop fields [

17]. Our early investigation revealed that, in Chinese maize fields,

E. annulipes is also a common natural enemy insect that consumes the larvae and eggs of the maize borers

O. furnacalis, which aligns with the findings of Calumpang et al. [

18]. Additionally, when insect prey is scarce, it feeds on plants, fruits, and even pollen. Owing to its suitability for laboratory rearing, numerous related studies have been conducted abroad [

19], but research on

E.annulipes in China remains limited.

Currently, the transgenic maize DBN9936 (Cry1Ab+EPSPS) has been planted in several provinces in China and will be progressively promoted for widespread cultivation in the future. This study focused on the transgenic maize DBN9936 and simulated the feeding behavior of E.annulipes under natural conditions. Short-term and long-term feeding experiments were conducted on the diets, consisting of two types of maize with or without maize borers (O. furnacalis), fed to the earwigs. We monitored the survival rate, weight, length, reproductive efficiency, and activities of the superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) enzymes of the earwigs. Furthermore, we determined the residual concentration of the Cry1Ab protein in the earwigs’ bodies, eggs, and feces. On the basis of these data, we aim to gain deeper insights into the impact of transgenic maize on this omnivorous insect prior to its large-scale commercial cultivation in China.

2. Results

2.1. Short-Term Survival Rate, Body Weight, and Length of the Earwigs

2.1.1. Short-Term Survival Rate

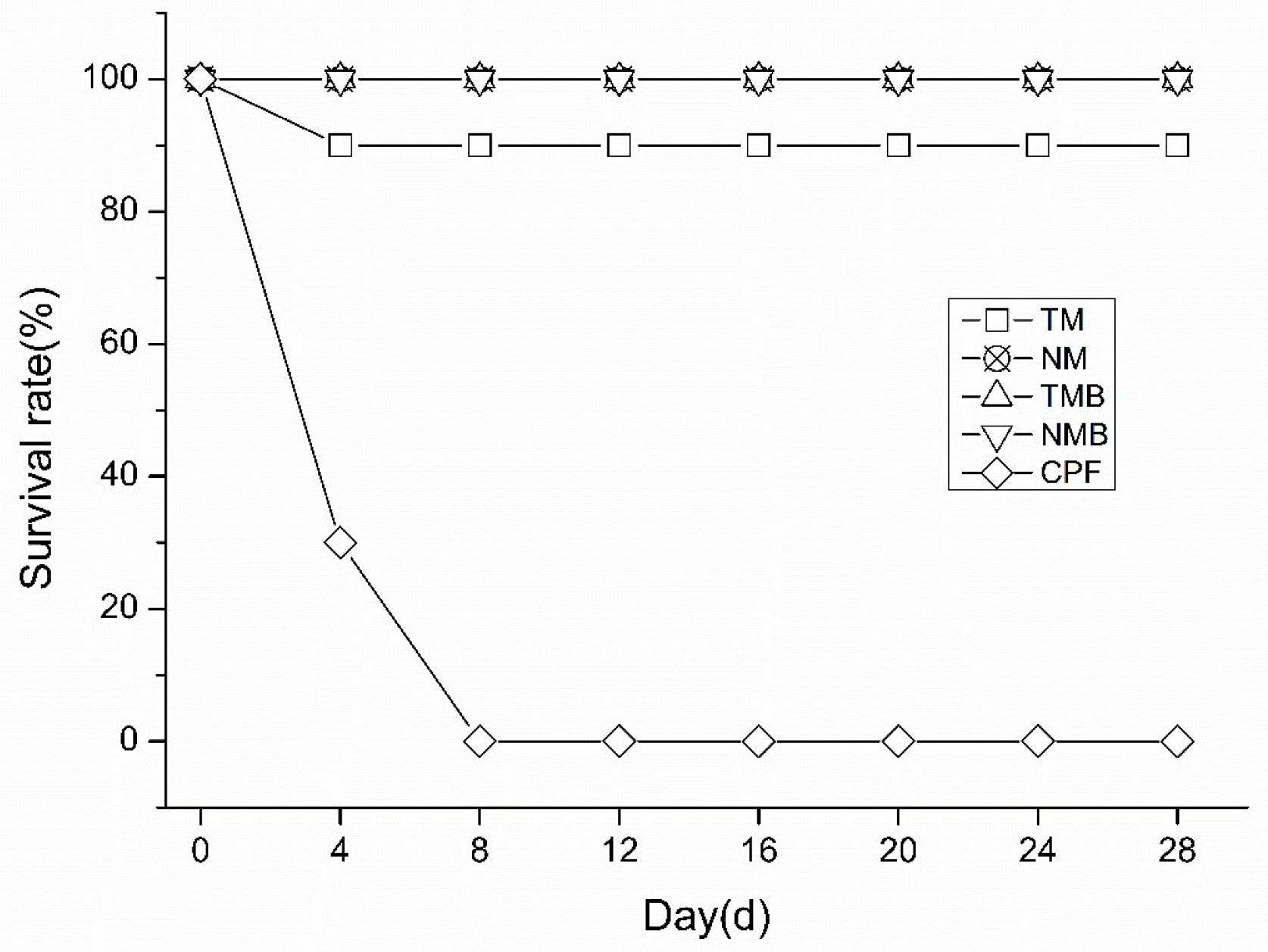

As shown in

Figure 1, all earwigs in the CPF group died within eight days, confirming their consumption of the artificial diet. In the remaining four treatments, only one earwig in the TM group died during the 28-day experiment, while the others remained healthy. No significant differences were detected between the transgenic and nontransgenic maize treatment groups.

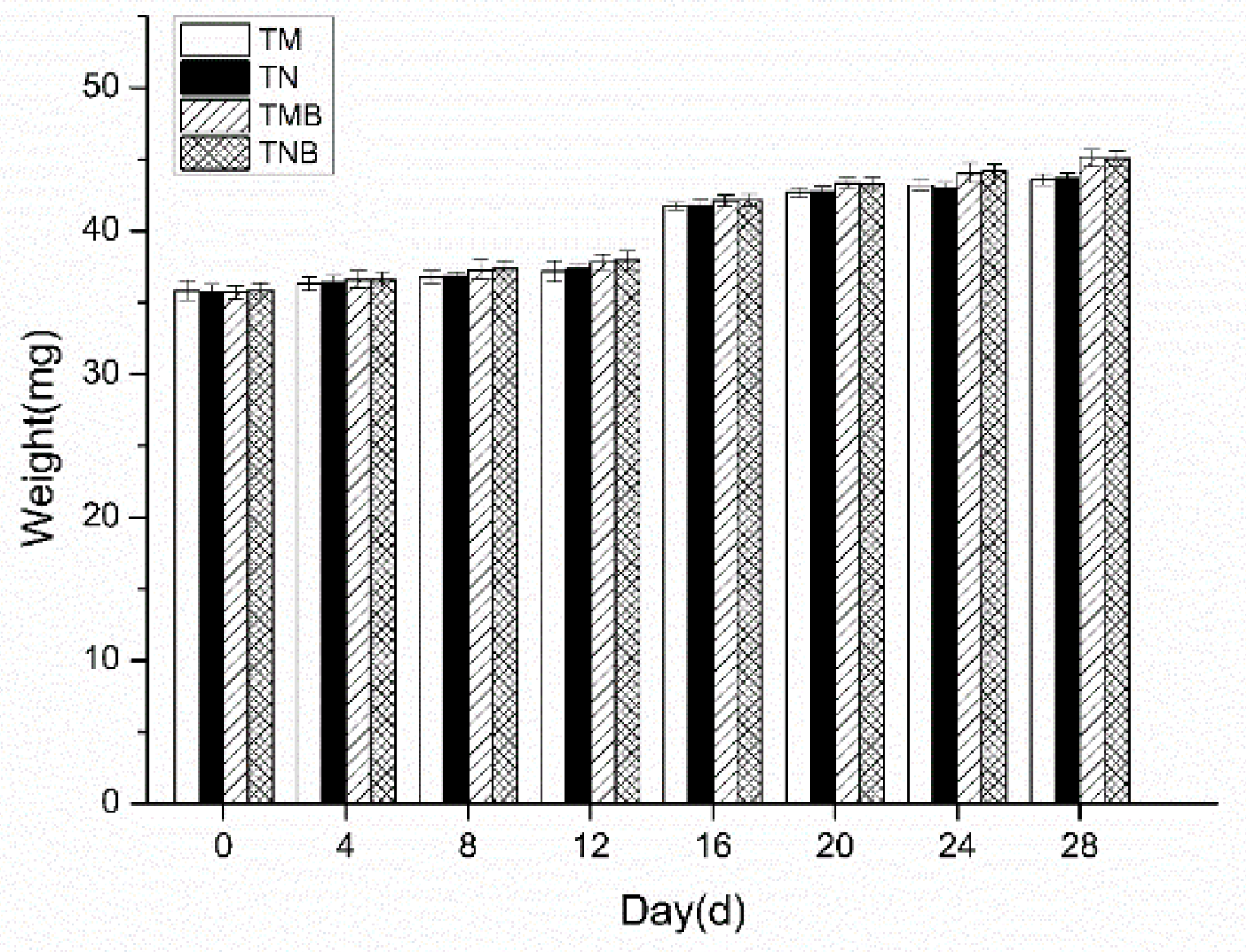

2.1.2. Body Weight in the Short-Term Experiment

The body weight changes in the earwigs over the 28-day experiment are presented in

Figure 2. Measurements taken every four days revealed a gradual increase in weight across all the treatments. No significant differences were detected between transgenic and nontransgenic maize in either artificial feed (P > 0.05) or maize borer-supplemented feed (P > 0.05).

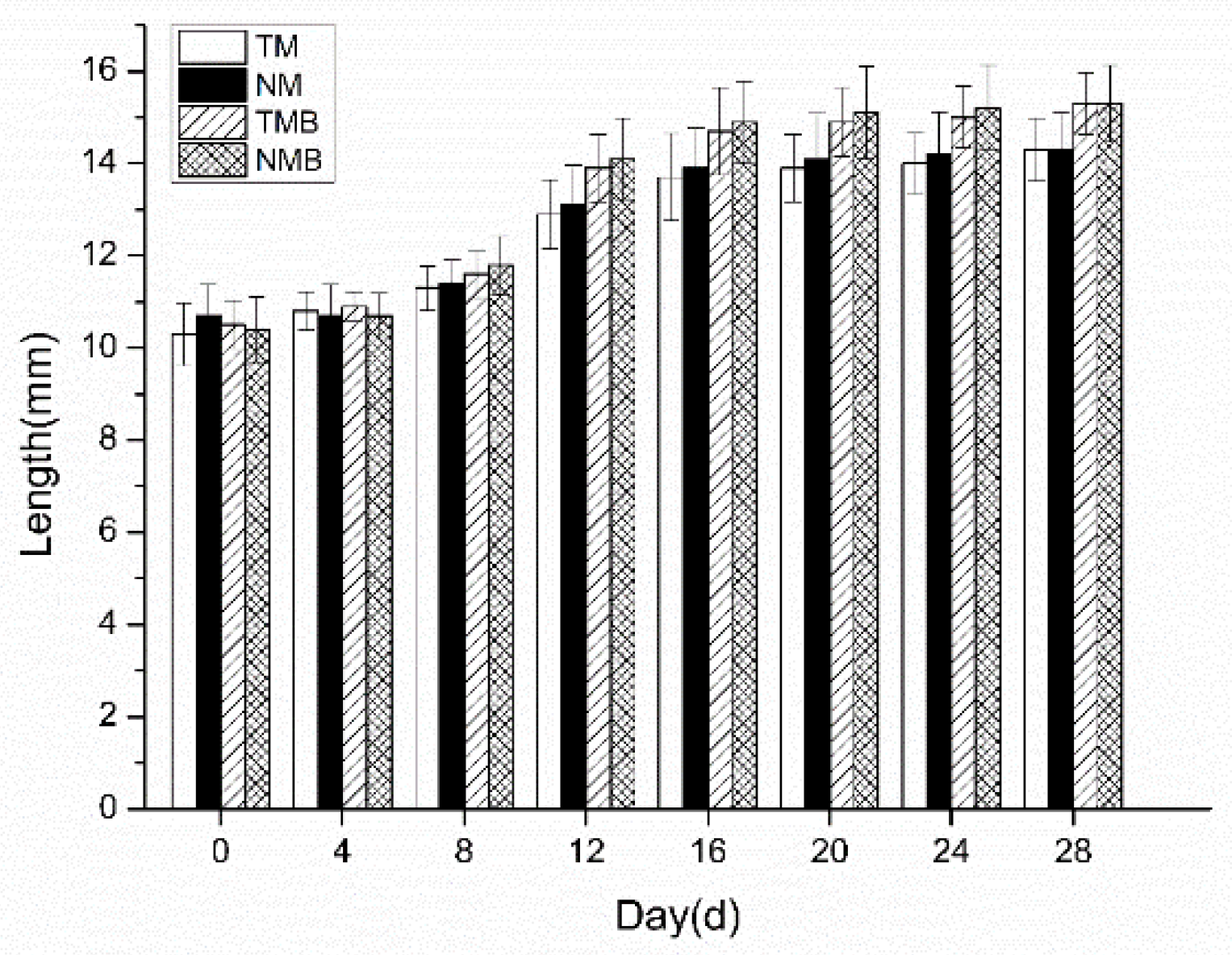

2.1.3. Body Length in Short-Term Experiment

Figure 3.

Body length of earwigs in four treatments: transgenic maize treatment (TM), nontransgenic maize treatment (NM), transgenic maize borer treatment (TMB), and notransgenic maize borer treatment (NMB).

Figure 3.

Body length of earwigs in four treatments: transgenic maize treatment (TM), nontransgenic maize treatment (NM), transgenic maize borer treatment (TMB), and notransgenic maize borer treatment (NMB).

2.2. SOD and CAT Enzyme Activity in Earwigs after the Short-Term Experiment

The superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity at the end of the 28-day experiment is summarized in

Table 1. The SOD activity was 36.68±0.75 U/mg in the TM treatment group and 36.66±0.59 U/mg in the NM treatment group. No significant differences were found between these two treatments. The SOD activity was 37.81±0.46 U/mg in the TMB treatment group and 37.66±0.33 U/mg in the NMB treatment group. TMB and NMB treatments resulted in greater SOD activity than did TM or NM treatment, and the difference was significant (P≤ 0.05).

Catalase (CAT) activity was slightly greater in the TMB and NMB treatment groups than in the TM and NM treatment groups, although the difference was not significant (P > 0.05). No notable differences were observed between the transgenic and nontransgenic maize treatment groups.

2.3. Long-term Experiment Involving Earwig Reproduction

Egg production across treatments is detailed in

Table 2. During spawning, the earwigs in the pure maize treatment groups laid 53.4 ± 5.78 and 51.6 ± 6.02 eggs, whereas those in the maize borer treatment groups laid 64.6 ± 5.04 and 62.4 ± 4.08 eggs. Earwigs fed maize borer larvae produced significantly more eggs, but no differences were detected between transgenic and nontransgenic maize groups.

After artificial incubation, hatchability was marginally greater in the maize borer treatment groups (TMB and NMB treatments) than in the pure artificial feed treatment groups (TM and NM treatments), although the difference was not significant (P > 0.05). Overall, no significant differences in hatchability were detected among the treatment groups.

Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences (P≤0.05).

2.4. Cry1Ab Protein Concentrations in Earwigs

Following long-term feeding, the Cry1Ab protein from transgenic maize DBN9936 was detected in the feces of earwigs that were fed transgenic maize (

Table 3). No Cry1Ab protein was detected in earwig tissues or eggs across all the treatment groups. In the TM treatment (transgenic maize) and TMB treatment (transgenic maize + borer) groups, the fecal Cry1Ab concentrations were 383.6 ± 15.42 ng/g and 364.8 ± 12.32 ng/g, respectively.

3. Discussion

E.annulipes is a quintessential omnivorous insect prevalent in agricultural fields [

20]. In this study,

E.annulipes was employed as a non-target organism to assess the biological safety of transgenic maize on omnivorous insects. To simulate natural earwig conditions, two feeding methods were established: (1) a maize-based artificial diet and (2) a maize-based artificial diet supplemented with maize borer larvae.

3.1. Short-Term Experiment

During the 28-day rearing period, the earwigs in every treatment exhibited normal growth, except for those exposed to chlorpyrifos, which resulted in mortality within 8 days. These findings demonstrate that both feeding methods effectively evaluated the environmental safety of transgenic maize on

E.annulipes, confirming that transgenic maize did not cause earwig mortality. These results align with previous research by Bernal et al. [

21] and Li et al. [

22]. Additionally, earwig body weight and length were monitored throughout the experiment. Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences in these parameters between the transgenic and nontransgenic maize treatment groups, which is consistent with the findings of Frizzas et al. [

23] and Jianrong et al. [

24]. Notably, earwigs that were fed diets containing maize borer larvae presented marginally greater body weights and lengths than those fed pure maize diets did, although this difference was not statistically significant. Short-term experiments confirmed that transgenic maize had no adverse effects on earwig mortality, body weight, or body length. However, earwigs in the insect-supplemented treatment group presented improved growth.

Following the short-term experiment, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) activities were measured in each treatment. No significant differences in these enzymes were observed between the transgenic and nontransgenic maize treatment groups, which is consistent with findings reported by Bai et al. [

25] on

Folsomia candida. However, earwigs that were fed maize borer larvae presented elevated activities of both enzymes, with a statistically significant increase in SOD activity. These findings suggest that incorporating maize borer larvae into the diet may trigger physiological responses in omnivorous insects, leading to increased activity of certain essential enzymes.

3.2. Long-Term Experiment

The long-term data revealed no significant differences in egg production or hatching rates between the transgenic and nontransgenic maize treatment groups. However, compared with earwigs that were fed maize borer larvae, those fed maize-only diets presented significantly reduced egg production. Rankin et al. [

26] reported similar trends, reporting greater reproductive efficiency in female earwigs fed protein-rich diets (e.g., cat food) than in those maintained on honey and fructose. These findings, including our results, suggest that predation on other insects enhances earwig growth and reproduction.

Finally, the Cry1Ab protein content was analyzed in earwig tissues, eggs, and feces. No Cry1Ab protein was detected in earwig tissues or eggs across any treatment groups. High concentrations of Cry1Ab were detected only in the fecal matter from the transgenic maize treatment groups, indicating that the protein passed through the digestive tract without being absorbed into the tissues or transferred to the eggs.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Animals

E. annulipes was sourced from maize fields in Yunnan Province and reared at the Key Laboratory of Environmental Protection Biodiversity and Biosafety in Jiangsu Province, China. Species identification was confirmed on the basis of body and leg colors as described by Kocarek [

27].

The maize borer O. furnacalis was sourced from maize fields in Yunnan Province and reared at the Key Laboratory of Environmental Protection Biodiversity and Biosafety in Jiangsu Province, China.

4.2. Artificial Feed

The feed mixture consisted of 300 g of ground transgenic maize flour (DBN9936) or nontransgenic maize flour (DBN318), 50 g of yeast powder, and 1000 mL of water. The mixture was stirred and sterilized and then stored in a refrigerator for future use.

4.3. Artificial Soil

The artificial soil was composed of 10% peat soil, 20% kaolin, 69% yellow sand, and 1% calcium carbonate. The pH was adjusted to 5.0–7.0, with a water content of approximately 50%, according to ISO 15952 [

28]. The soil was then sterilized and dried for future use.

4.4. Rearing Conditions

Individual earwigs were reared in glass beakers with an approximately 3 cm layer of artificial soil. Upon reaching maturity, the larvae were paired for reproduction. The light‒dark cycle was set to 12:12 (light:dark), with the light intensity ranging from 20 to 40 lx. The soil moisture was maintained to keep the middle layer slightly moist. The air temperature was maintained at 25 °C, with a humidity range of 50%–70%.

4.5. Short-Term Experiments

Fourth-instar earwigs of similar body length and weight were selected, with five males and five females in each treatment.

Transgenic maize treatment (TM): Earwigs were fed artificial feed containing transgenic maize flour (DBN9936). The feed was placed on a small piece of filter paper in the feeding container and replaced daily.

Nontransgenic maize treatment (NM): The transgenic maize flour in the TM treatment was replaced with nontransgenic maize flour (DBN318).

Transgenic maize borer treatment (TMB): Newly hatched maize borer larvae were added to the TM treatment for 24 h, after which the earwigs were placed in the container.

Nontransgenic maize borer (NMB) treatment: Transgenic maize flour in the TMB treatment was replaced with nontransgenic maize flour (DBN318).

Chlorpyrifos treatment (CPF): A 5% chlorpyrifos solution was added to the artificial feed as a positive control.

All the treatments lasted for 28 days, and the weight, length, and survival of the earwigs were recorded every 4 days.

4.6. Long-Term Experiment

Fourth-instar earwigs were fed according to the short-term experimental treatments. Each treatment consisted of five replicates, with one male and one female in each replicate. Each container included wet, absorbent paper folded into a W shape to provide a site for females until the first oviposition and hatching. After the first spawning, the number of eggs and hatching rates were recorded.

4.7. Enzyme Activity Experiment

After the short-term experiments, the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) in the earwigs were measured using kits from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.8. Cry1Ab Protein Residue Experiment

After the long-term experiments, Cry1Ab protein levels in individuals from each treatment group were measured using the ELISA with an Envirologix monitoring kit (USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Data processing and analysis were performed using SPSS. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the least significant difference (LSD, α = 0.05) test were used to evaluate differences among treatments.

5. Conclusions

This study simulated two pathways by which E.annulipes might acquire exogenous proteins from transgenic maize under field conditions. The results demonstrated that the consumption of transgenic maize had no adverse effects on earwig survival, growth, or reproductive capacity. Furthermore, E.annulipes, an omnivorous predator, maintained normal survival and reproduction when fed a maize-based diet, whereas supplementation with maize borer larvae increased growth and reproductive performance. The underlying mechanisms for these occurrences remain unclear, and whether these traits are common among omnivorous insects warrants further investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.F. and B.L.; methodology, Z.F. and L.L.; software, Z.F. and Z.R.; investigation, W.S., Q.Y. and L.Z.; data curation, X.Y.; writing—review and editing, Z.F., L.L. and X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Biological Breeding-National Science and Technology Major Project (2023ZD04062; 2022ZD04021).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- ISAAA: Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2023.

- Stuart J S. The human health benefits from GM crops [J].Plant Biotechnology Journal, 2020, 18:887-888.

- Resende D C, Mendes S M, Marucci R C, et al. Does Bt maize cultivation affect the non-target insect community in the agro ecosystem[J]. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia, 2016, 60(1): 82-93.

- O’Callaghan, M., Glare, T.R., Burgess, E.P.J., Malone, L.A.. Effects of plants genetically modified for insect resistance on non-target organisms. Annu. Rev. Entomol,2005,50, 271–292.

- Lövei GL, Arpaia S. The impact of transgenic plants on natural enemies a critical review of laboratory studies. Entomol Exp Appl,2005, 114:1–14.

- Romeis J, Meissle M, Bigler F. Transgenic crops expressing Bacillus thuringiensis toxins and biological control. Nat Biotechnol,2006,24:63–71.

- Widmer, F. Assessing effects of transgenic crops on soil microbial communities. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol, 2007, 107:207–234.

- Filion, M. Do transgenic plants affect rhizobacteria populations? Microbial Biotechnol,2008, 1:463–475.

- Icoz I, Stotzky G. Fate and effects of insect-resistant Bt crops in soil ecosystems. Soil Biol Biochem,2008, 40:559–586.

- Kocarek P, Dvorak L, Kirstova M. Euborellia annulipes (Dermaptera: Anisolabididae), a new alien earwig in Central European greenhouses: potential pest or beneficial inhabitant [J]. Applied Entomology and Zoology, 2015, 50: 201-206.

- Byttebier, B., & Fischer, S. Predation on eggs of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae): Temporal dynamics and identification of potential predators during the winter season in a temperate region. Journal of Medical Entomology, 2019, 56, 737– 743.

- Tangkawanit, U., Seehavet, S., & Siri, N. The potential of Labidura riparia and Euborellia annulipes (Dermaptera) as predators of house fly in livestock. Songklanakarin Journal of Science and Technology, 2021, 43, 603–607.

- Oliveira, L. V. Q., Oliveria, R., Nascimento Júnior, J. L., Silva, I. T. F. A., Barbosa, V. O., & Batista, J. L.. Capacidade de busca da tesourinha Euborellia annulipes sobre o pulgão Brevicoryne bras sicae (Hemiptera: Aphididae). PesquisAgro, 2019, 2, 3– 10.

- Nunes G D S, Dantas T A V, Souza M D S D,et al.Life stage and population density of Plutella xylostella affect the predation behavior of Euborellia annulipes[J].Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 2019, 167(6).

- Silva AB, Batista JL, Brito CH. Capacidade predatória de Euborellia annulipes (Lucas, 1847) sobre Spodoptera frugiperda (Smith, 1797). Acta Scientiarum Agronomy, 2009, 31 (1): 7–11.

- Lemos, W. P., Ramalho, F. S., & Zanuncio, J. C. Age- dependent fecundity and life- fertility tables for Euborellia annulipes (Lucas) (Dermaptera: Anisolabididae) a cotton boll weevil predator in laboratory studies with an artificial diet. Environmental Entomology, 2003, 32,592-601.

- Chen Yixin Fauna of China: Insects Volume 35, Coleoptera [M]. Science Press, 2004.

- Calumpang S M F, Navasero M V.Behavioral Response of the Asian Maize Borer Ostrinia furnacalis Guenee (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) and the Earwig Euborelia annulipes Lucas (Dermaptera: Anisolabiidae) to Selected Crops and Weeds Associated with Sweet Maize [J].Philippine Agriculturist, 2013, 96(1):48-54.

- Silva AB, Batista JL, Brito CH. Aspectos biológicos de Euborellia annulipes (Dermaptera: Anisolabididae) alimentada com o pulgão Hyadaphis foeniculi (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Revista Caatinga, 2010, 23:21-27.

- Kocarek P, Dvorak L, Kirstova M. Euborellia annulipes (Dermaptera: Anisolabididae), a new alien earwig in Central European greenhouses: potential pest or beneficial inhabitant [J]. Applied Entomology and Zoology, 2015, 50: 201-206.

- Bernal CC, Aguda RM, Cohen MB, Effect of rice lines transformed with Bacillus thuringiensis toxin genes on the brown planthopper and its predator Cyrtorhinus lividipennis. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 2002, 102(1): 21–28.

- Li FF, Ye GY, Wu Q, Peng YF, Chen XX, Arthropod abundance and diversity in Bt and non-Bt rice fields. Environmental Entomology, 2007, 36(3): 646–654.

- Frizzas M R, Silveira Neto S, Oliveira C M, et al. Genetically modified maize on fall armyworm and earwig populations under field conditions [J]. 2014:203-209.

- Jianrong Huang, Guoping Li, Bing Liu, Yu Gao, Kongming Wu, Hongqiang Feng, Field evaluation the effect of two transgenic Bt maize events on predatory arthropods in the Huang-Huai-Hai summer maize-growing region of China, Environmental Entomology, Volume 53, Issue 3, June 2024, Pages 398–405.

- Bai,Yaoyu,Yan,et al.Effects of Transgenic Bt Rice on Growth, Reproduction, and Superoxide Dismutase Activity of Folsomia candida (Collembola: Isotomidae) in Laboratory Studies[J].jnl. econ. entom. 2011, 104(6):1892-1899.

- Rankin S M, Dossat H B, Garcia K M. Effects of diet and mating status upon corpus allatum activity, oocyte growth, and salivary gland size in the ring-legged earwig[J]. Entomologia experimental is et applicata, 1997, 83(1): 31-40.

- Kocarek P. Euborellia ornata sp. nov. from Nepal (Dermaptera: Anisolabididae). Acta Entomologica Musei Nationalis Pragae, 2011, 51 (2): 391-395.

- ISO 15952:2018, Soil quality - Effects of pollutants on juvenile land snails (Helicidae) - Determination of the effects on growth by soil contamination.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).