1. Introduction

The rapid rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria has triggered a global healthcare crisis, driving the need for alternative therapeutic strategies[

1]. One promising solution is the use of nanomaterials with inherent antibacterial properties, such as Carbon Quantum Dots (CQDs) [

2,

3,

4]. These carbon-based nanoparticles, typically less than 10 nanometers in diameter, are recognized for their biocompatibility, adjustable optical properties, and ease of surface modification. CQDs have attracted significant interest not only in bio imaging and drug delivery applications but also for their potential as antibacterial agents.

CQDs can be synthesized using various methods and carbon precursors, including natural products and waste materials, to yield different surface functional groups and unique antibacterial properties [

2,

3,

4]. The choice of carbon source and synthetic method significantly impacts the quality, properties, and functionality of carbon quantum dots (CQDs). Different carbon sources—such as natural products, organic waste, or synthetic compounds introduce unique molecular structures and compositions to the CQDs, resulting in diverse surface functional groups that influence key properties like solubility, stability, and biocompatibility. The carbon source also affects the optical, antibacterial, and bioactive properties of the prepared CQDs [

5,

6]. For instance, the emission wavelength and quantum yield of CQDs depend on the raw material used; carbon sources containing heteroatoms like nitrogen or sulfur enhance fluorescence and increase quantum yield compared to sources without heteroatoms. Additionally, natural carbon sources rich in bioactive compounds, such as polyphenols, can impart CQDs with inherent antibacterial properties, making them especially suited for biomedical applications.

The size, morphology, surface functionalization, yield, and purity of carbon quantum dots (CQDs) largely depend on the synthesis method used. Different approaches, such as hydrothermal, microwave, or pyrolysis methods, control factors like temperature, pressure, and reaction environment, which directly affect the size, shape, and mono-dispersity of CQDs. Smaller, more uniform particles with consistent morphology are ideal for optical applications and biological interactions.

Each synthesis method enables specific surface modifications. For instance, hydrothermal synthesis can introduce functional groups that enhance water solubility, while pyrolysis may yield a less functionalized surface. These surface groups are critical for applications such as drug delivery or antimicrobial action, where compatibility and binding capability are essential.

Moreover, synthesis methods vary in efficiency and yield. Techniques like hydrothermal and microwave synthesis typically produce higher yields of CQDs with fewer impurities, whereas others may require additional purification steps to eliminate by-products.

In summary, while the carbon source primarily dictates the elemental composition and initial functional groups of CQDs, the synthesis method controls particle size, morphology, and surface chemistry—factors essential for tailoring CQDs to applications in imaging, drug delivery, and antibacterial treatment.

Ferula asafoetida Linn. is the primary source of asafoetida, a pungent oleogum resin known for its strong sulfurous aroma and valuable medicinal and nutritional properties. Traditionally used for centuries as both a spice and a folk remedy [

7,

8,

9], recent studies have further demonstrated its antimicrobial effects [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Asafoetida is the dried latex extracted from the rhizome or taproot of several

Ferula species, which are perennial herbs in the carrot family. This resin is primarily produced in regions such as Iran, Afghanistan, Central Asia, northern India, and Northwest China.

Recently, CQDs are mainly used as visible/natural light activated antimicrobial agents [

3]. In this study we used Asafoetida powder as a carbon source in a green one-step hydrothermal method to synthesize CQDs. Copper-doped CQDs (Cu-CQDs) were also prepared from Asafoetida powder. Their antimicrobial effects were evaluated both in solution and when attached to the surface of PVC plastic coupons as a proof of concept.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Anhydrous copper sulfate was obtained from CHIMIQUES ACS CHEMICALS Inc., Canada. Absolute ethanol, n-hexane, Heptane, and ethyl acetate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Asafoetida was purchased from local supermarkets in Ahvaz, Khuzestan, Iran. Ultrapure water was used throughout the study. MEG-Cl for CQD attachment to the surface of plastic coupons was pre-synthesized by the Thompson group [

16]. LB and Agar were purchased from MedStore U of T (Toronto, Canada). Experiments were carried out with

Escherichia coli GFP (ATCC 25922GFP)

, and

Staphylococcus aureus KR3.

2.2. Instruments

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were captured on a Hitachi HT7700 TEM/STEM at 80 kV after dispersing the CQDs on a carbon-coated copper grid. For atomic force microscopy (AFM), CQDs were dispersed in acetone, and a drop of the suspension was placed on a mica sheet, with imaging conducted in tapping mode using a Bruker Inspire (Multimode 8) equipped with a NanoWorld Arrow-NCPt tip (force constant = 42 N/m, resonance frequency = 285 kHz, tip radius < 25 nm). Particle size analysis (PSA) was performed using a Scatteroscope I, Qudix (Korea). Functional groups on the CQDs were identified using a Vortex 70 FTIR (Bruker, Germany), and UV spectra were recorded with a VWR 1600 PC UV–Vis spectrophotometer (China). Luminescence spectra and measurements were taken with a Thermo Scientific luminescence spectrometer (USA) and a PerkinElmer FL6500. XPS analysis was conducted with a Theta Probe Angle-Resolved X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer System (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) located at Surface Interface Ontario (University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada).

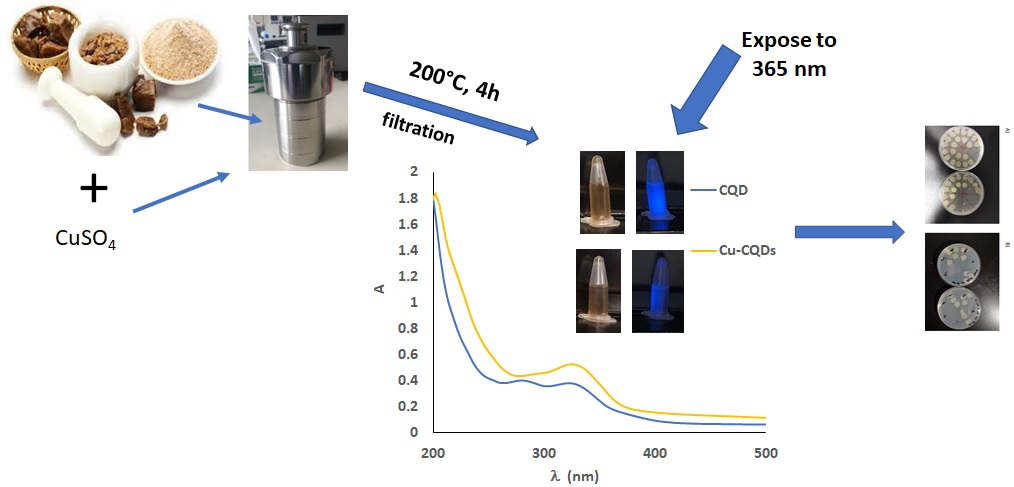

2.3. CQDs and Cu-CQDs Synthesis

CQDs and Cu-CQDs were prepared by hydrothermal method. About 100 mg of Asafoetida powder were dispersed in 40 mL ultrapure water in a Teflon linen of a stainless steels autoclave and the autoclave were tightened and heated in a muffle furnace at 200 °C for 4h. As for Cu-CQDs synthesis, 30 mg anhydrous copper sulphate was completely dissolved in 40 mL of ultrapure water in the Teflon linen, and 100 mg Asafoetida powder was added and stirred for 5 min then Teflon linen was placed in stainless steel body, tighten, and heated in an oven. After 4h the reactor was cooled down and the contents were centrifuged to remove any large particles. A brown solution was obtained in both cases; this solution was dialysed against distilled water; the dialysed samples were further purified by gel chromatography using a 9 × 0.5 cm silica gel column.

2.4. Antibacterial Evaluation

Fifty microliters (50 µL) of a 1% bacterial culture of either E. coli or S. aureus from overnight culture in LB medium was added to each well of a 96-well plate. To this was added either 50 µL of 100 mg mL-1 ampicillin (Positive Control), 50 µL of deionised water (negative control), or 50 µL of QD solution which was serially diluted from full concentration to 1/64 concentration; each condition had 3 replicates. The well plate was then incubated at 37°C with rotation at 120 rpm for 24 hours; the solution from each well was diluted to 1 mL in deionised water and its absorbance at 600 nm was measured. This value was subtracted from each measurement to control for absorbance by the dots themselves. Three spots of each diluted solution (20 μL) was spotted onto an agar plate, and grown overnight at 37°C. Colonies were then counted to determine the colony forming units (CFU) per mL for each solution.

2.5. Modification of Plastic

Plastic coupons (1 cm x 1 cm x 1.5 mm) were cut out from a PVC sheet. They were then rinsed with 1% solution of SDS in deionised water, followed by sonication for 5 minutes in the same solution. They were again rinsed with deionised water several times and finally rinsed with 95% ethanol solution. The coupons were then dried under a stream of nitrogen, followed by plasma cleaning in air (10 minutes per side). They were then stored in a humidity chamber (70% relative humidity) overnight.

The samples were transferred into pre-silanized test tubes, capped with rubber stoppers, and transferred into a glovebox with inert N2 atmosphere. 1 mL of MEG-Cl solution in heptane (1:1000) was added to each sample, and the samples stoppered and sealed with parafilm. They were removed from the glovebox and placed on a rotator at 120 rpm for 90 mins. After this they were rinsed with heptane, and then sonicated for 5 mins in heptane, and finally rinsed with 95% ethanol.

To each sample was added 1mL of QD solution (10.25 mg mL-1) in deionised water, to which was added 500 μL pyridine. The samples were rotated overnight, before the solution was removed and the samples were then rinsed with deionised water, followed by sonication in the deionised water for 5 minutes. The samples (plastic coupons) were then dried under a stream of air and stored in a clean vial until use. This procedure was applied to both CQDs and Cu-CQDs.

3. Results and Discussion

Using carbon quantum dots (CQDs) synthesized from plants as a carbon source in aqueous media represents a promising advancement in green chemistry and nanotechnology. For enhanced antibacterial activity, selecting plants with inherent antimicrobial properties offers additional benefits, as these plants can transfer their antibacterial agents to the surface of the as-prepared CQDs.

In this study, Asafoetida was chosen due to its known antimicrobial efficacy against pathogens such as Salmonella typhi, E. coli, S. aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Aspergillus niger, and Candida albicans [

17,

18,

19]. Given these properties, Asafoetida was used as a carbon source to produce CQDs containing antimicrobial functional groups. As-prepared CQDs were then tested for their antibacterial effects against E. coli and S. aureus. To enhance the antibactarial potential of the prepared CQDs, copper was also dopped into them and the results were compared.

3.1. Spectroscopic Evaluation of CQDs

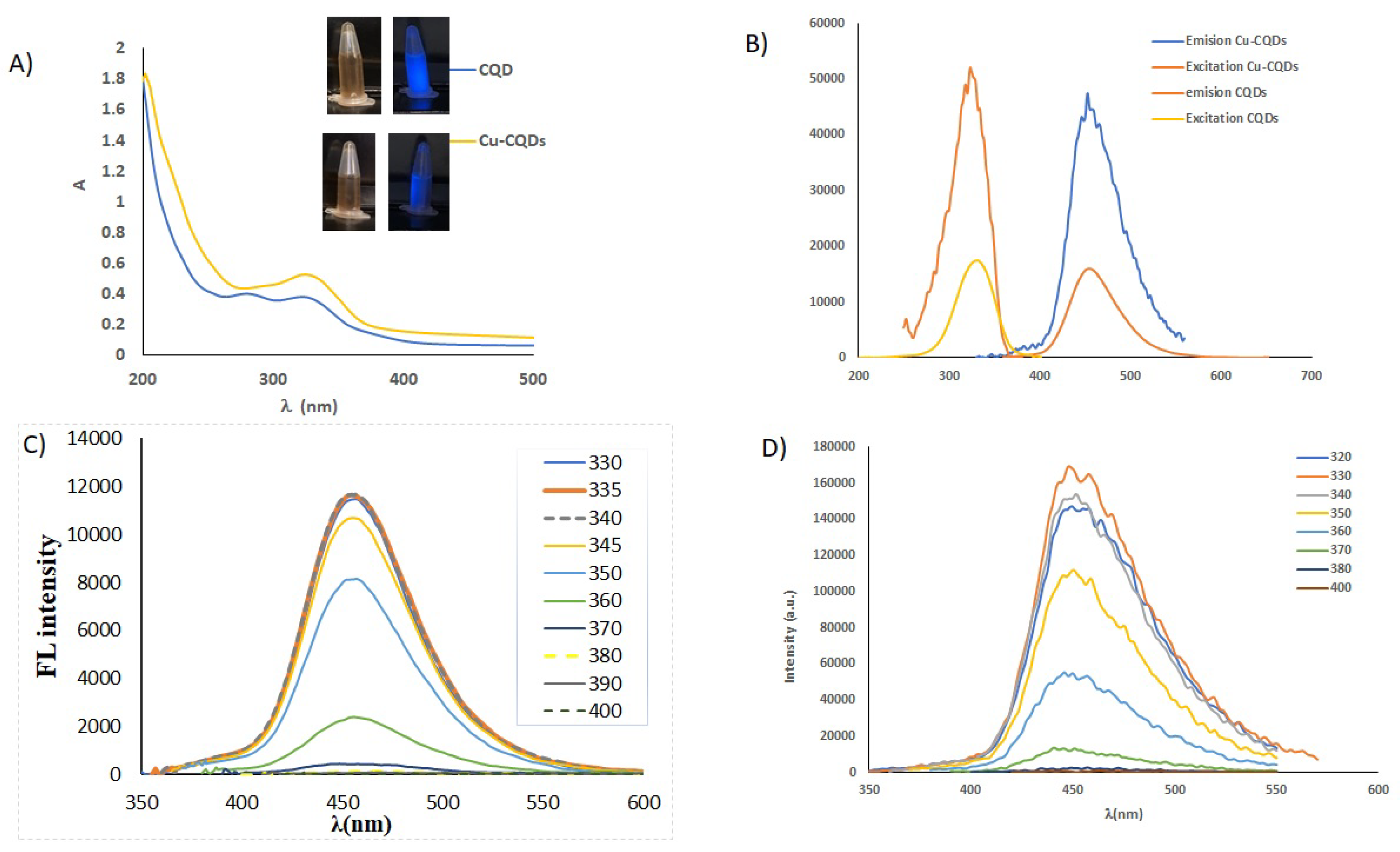

UV/Vis, and fluorscence behaviour of CQDs and Cu-CQDs are illustrated in

Figure 1. As it is obvious the water soluble carbon dots are brown under daylight and illuminate blue light while irradiated by 360 nm. Cu-CQDs blue emmision is more intense than that of CQDs. UV-Vis spectra (

Figure 1A) of both particles are sligthly different, a good indication of copper dopping in as-prepared carbon quantum dots. CQDs have absorption maxima at 280 nm and 335 nm but Cu-CQDs has a absorption maxima at 335 nm. The absorption band at around 340 nm in carbon dots is often associated with

n→π transitions, typically attributed to the presence of surface functional groups or defects containing oxygen- or nitrogen-containing groups, such as C=O (carbonyl) or N-H groups. These groups can form energy states within the carbon dot structure that absorb light in the UV range, around 340 nm [

20,

21]. One study reports how the presence of specific functional groups, like C=O and C–OH, alters the optical and photoluminescent properties, leading to characteristic UV-visible absorption bands (typically in the 260–340 nm range) due to n→π* and π→π* transitions [

22].

Additionally, this absorption band can indicate surface states and defect sites that play a role in the electronic structure of CQDs, often contributing to their photoluminescent properties and possibly influencing their antibacterial activity. By modifying the functional groups or surface passivation of CQDs, this absorption peak can often be tuned, affecting the CQDs' emission properties and interactions with biological targets [

23]. Direct band gap of CQDs and Cu-CQDs determined by Tauc plots using the corresponding UV/Vis spectra [

24,

25] were in the range of 3.39-4.47 eV, and 3.4-4.5 eV, respectively. No significant changes in the band gaps are observed on Cu doping and indicates that both particles have approximately the same sizes.

Quantum effect and surface functional groups determine the photoluminescence properties of the quantum dots [

6,

21,

23]. Fluorescence emission of CQDs and Cu-CQDs (

Figure 1B-D) shows excitation wavelength independent emission profile indicating that uniform surface states are available in as-prepared dots. Maximum emission intensity is observed at 450 nm and 455 nm while excited at 335 nm and 330 nm for CQDs and Cu-CQDs, consequently. Emission intensity is higher in Cu-CQDs (

Figure 1B), fluorescence quantum yield for CQDs and Cu-CQDs were 37% and 73.4%, respectively (for the detailed of quantum yield determination see supplementary material). When CQDs are doped with copper, highly luminescent carbon dots are produced. A higher quantum yield may indicate a more rigid structure of CQDs due to copper doping.

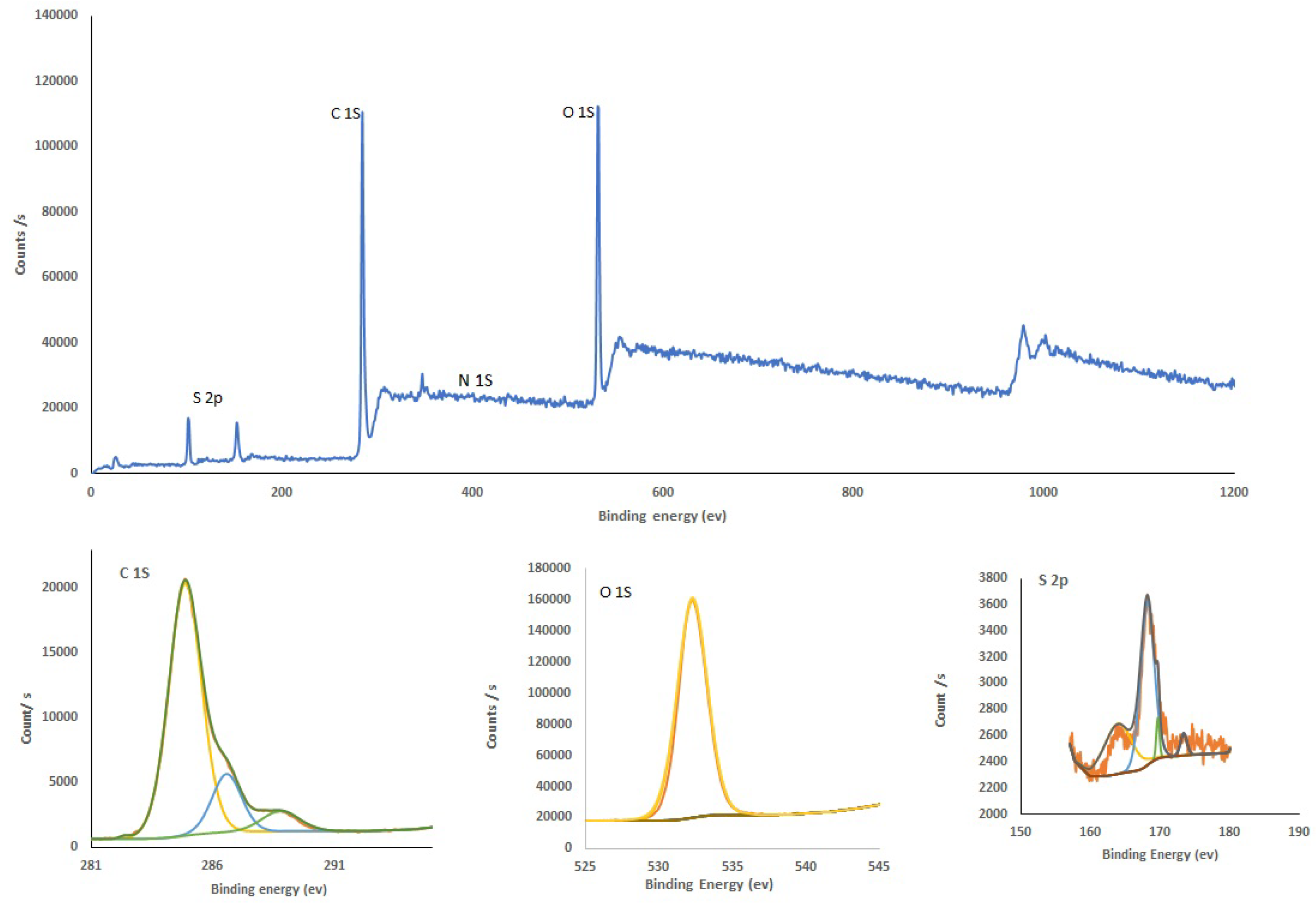

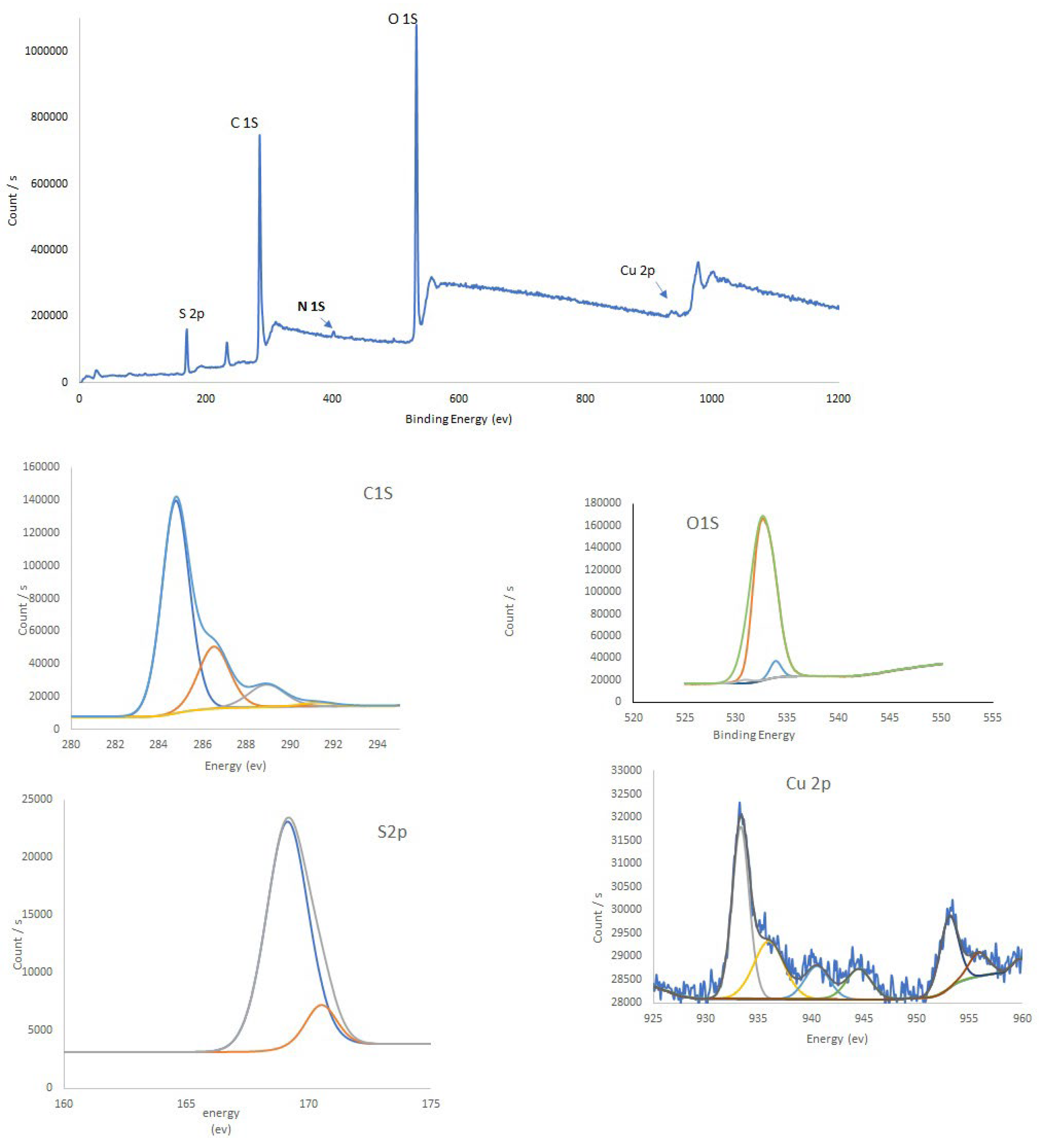

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) provides valuable insights into the luminescence properties of carbon quantum dots (CQDs) by analyzing their surface chemistry and electronic structure. XPS identifies the elements present on the CQD surface, along with their oxidation states. This is crucial because specific elements and oxidation states influence the energy levels within the CQDs, which affect luminescence. For example, doping carbon quantum dots with metals (like copper) or modifying them with specific functional groups can introduce new electronic states that enhance or tune luminescence. XPS detects functional groups or defects on the CQD surface. These surface features can serve as sites for electron or hole trapping, impacting the CQDs’ emission properties. For instance, oxygen-containing functional groups often enhance photoluminescence by creating trap states that contribute to radiative recombination. XPS also reveals shifts in binding energy, indicating changes in electronic structure. Shifts in binding energies can suggest stronger quantum confinement or altered electronic interactions, which can lead to increased or shifted luminescence wavelengths. For example, if copper doping causes a shift in binding energies, it could be linked to enhanced rigidity in the CQD structure, contributing to higher luminescence stability.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 present the XPS spectra for as-prepared CQDs and Cu-CQDs, respectively. By comparing two survays one can realized that Cu and N peaks are appreaes when copper dopped carbon dots are preapered. O1s in CQDs (

Figure 2) showes a peak in the range of 526-540 eV that has a maximum arund 532.38. deconvolution of this peak shows a sigle peak and it confirms that hydroxyl functianal group in as prepared CQDs. While copper is added to the carbon source before synthesis O1s was deconvoluted to three different peaks (

Figure 3) and identifying the presence of C-O and C=O. it appears since Cu form complexes on the surface of Cu-CQDs (ref). FTIR spectrum also confir,s the functional groups (See supplementary material)

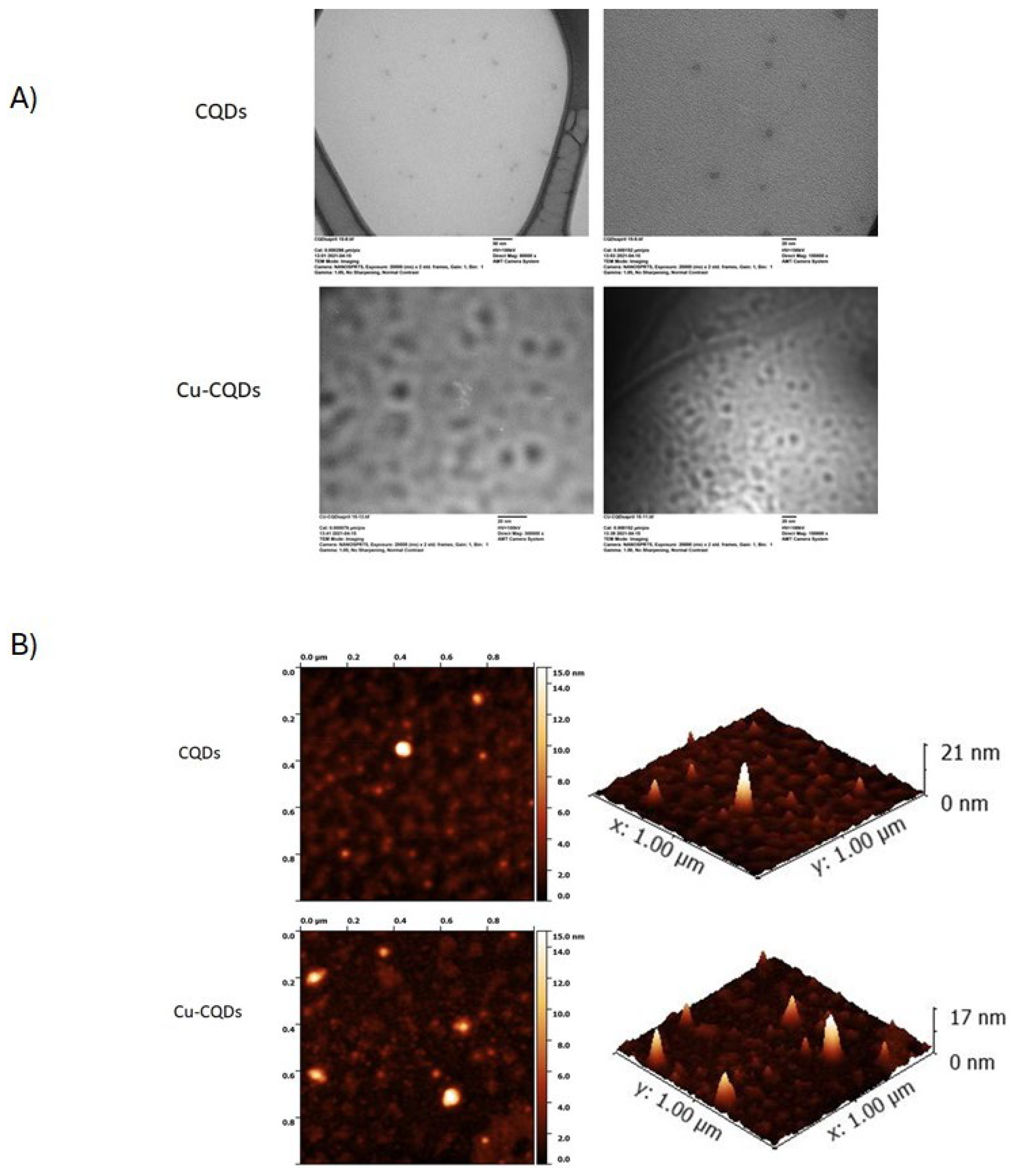

3.2. Microscopic Evaluations of CQDs

TEM and AFM are commonly used techniques to analyze their morphology, size, and surface characteristics of nanoparticles. TEM provides high-resolution images of CQDs, typically showing spherical or quasi-spherical nanoparticles with sizes in the range of 2–10 nm. TEM image and AFM of CQDs and Cu-CQDs confirms formation of quantum dots as it is indicated in the figures (

Figure 4).

If CQDs tend to aggregate, TEM can show clusters instead of well-dispersed dots. This can happen due to functional groups or improper dispersion.

AFM reveals surface topography and height. Bright spots in AFM indicates the CQDs (

Figure 4B) and height profile shows their thickness. In AFM 3D surface image, height distribution is observed. A uniform height distribution suggests monodispersity of the particles, while variation indicates aggregation or non-uniform functionalizations. CQDs with a thickness of 1–3 nm suggests a single or few-layered graphene-like structure. If the thickness is higher (>3 nm), it indicates stacked or functionalized CQDs.

Figure 4A shows shows some degree of aggregation of both CQDs. Also higher thickness of some particles coated on the mica sheet for Cu-CQDs may be an indication of functionalization or more aggregation in Cu-CQDs. TEM images of the Cu-CQDs also shows some degree of aggregation.

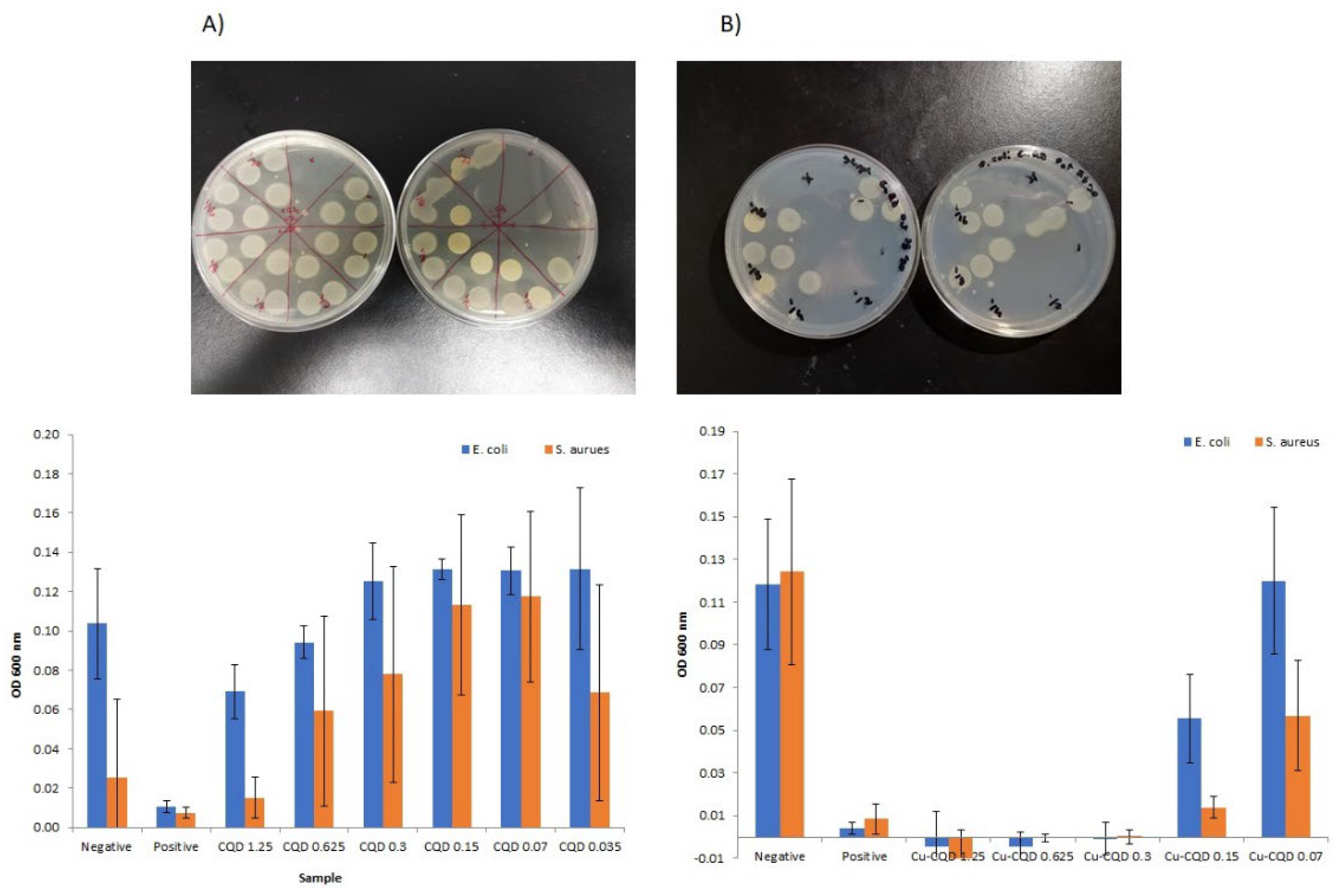

3.3. Antibacterial Activities of as-Prepared CQDs

As a proof of concept on antibacterial activity of CQDs and Cu-CQDs against Ecoli as gram negative bacteria and S. Aureus as representative of a gram positive bacteria was evaluated by both agar plate and solution methods. As it is indicated in

Figure 5 both particles have higher antibacterial activity against S. Arusu. Cu-CQDs antibacterial activity is much more higher than CQDs alone (

Figure 5P). The graphs represent the optical density (OD 600 nm) of bacterial growth for

E. coli (blue bars) and

S. aureus (orange bars) under different treatments with CQDs and Cu-CQDs at varying concentrations. The positive control and the negative control are penicillin and distilled water, respectively. No complete inhibition is observed for CQDs, as OD values remain relatively high. CQD 1.25 mg/mL shows the lowest bacterial growth, but inhibition is incomplete for both

E. coli and

S. aureus. Cu-CQD up to 0.3 mg/mL has zero OD values, indicating nearly complete bacterial inhibition for both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Lower concentrations (e.g., 0.15 mg/mL and below) show increased bacterial growth, still showing less than 50 percent growth inhibition for

S. aureus. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) appears to be 0.3 mg/mL for Cu-CQDs, as this is the lowest concentration showing complete bacterial inhibition. CQDs do not achieve full inhibition at any tested concentration but show a reduction in bacterial growth at 1.25 mg/mL.

E. coli is a Gram-negative bacterium with a thin peptidoglycan layer and an outer membrane containing lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which makes it more resistant to antibiotics. In contrast, S. aureus does not have an outer membrane but has a thick peptidoglycan layer. The lower activity of CQDs against E. coli compared to S. aureus is likely due to reduced interaction of the CQDs with the outer membrane of E. coli.

Copper exhibits strong antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive (S. aureus) and Gram-negative (E. coli) bacteria through multiple mechanisms that disrupt bacterial survival. Therefore, copper-based materials, such as Cu-CQDs, demonstrate strong antibacterial activity due to reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, membrane disruption, enzyme inactivation, and DNA damage. In this study, Cu-CQDs showed stronger antibacterial activity against S. aureus, while E. coli exhibited some resistance due to its outer membrane barrier, despite having a thin peptidoglycan layer. It is probable that ROS cause oxidative stress, leading to lipid peroxidation (damaging bacterial membranes), DNA degradation, protein oxidation, and enzyme inactivation. The precise mechanism of interaction requires further investigation.

E. coli removal from catheter surfaces is crucial for several reasons. First its entire role in catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) and other healthcare-associated infections are well-known [

26,

27,

28]. E. coli is one of the primary pathogens responsible for CAUTIs. E. coli can form biofilms on catheter surfaces, creating a protective environment that makes the bacteria more resistant to antibiotics and host immune responses. Biofilm-associated infections are difficult to treat and often lead to persistent infections. Biofilm-forming E. coli can also develop antibiotic resistance, making infections harder to treat. Catheter-related infections can lead to severe complications, including bloodstream infections and sepsis. Eliminating E. coli from catheter surfaces reduces the risk of systemic infections and associated morbidity and mortality. Preventing bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation can also help reduce the need for antibiotics and slow the emergence of resistant strains. Bacterial colonization can lead to catheter blockages and malfunction, necessitating frequent replacements. Preventing E. coli adhesion helps maintain catheter function and reduces the need for repeated interventions [

27,

28,

29].

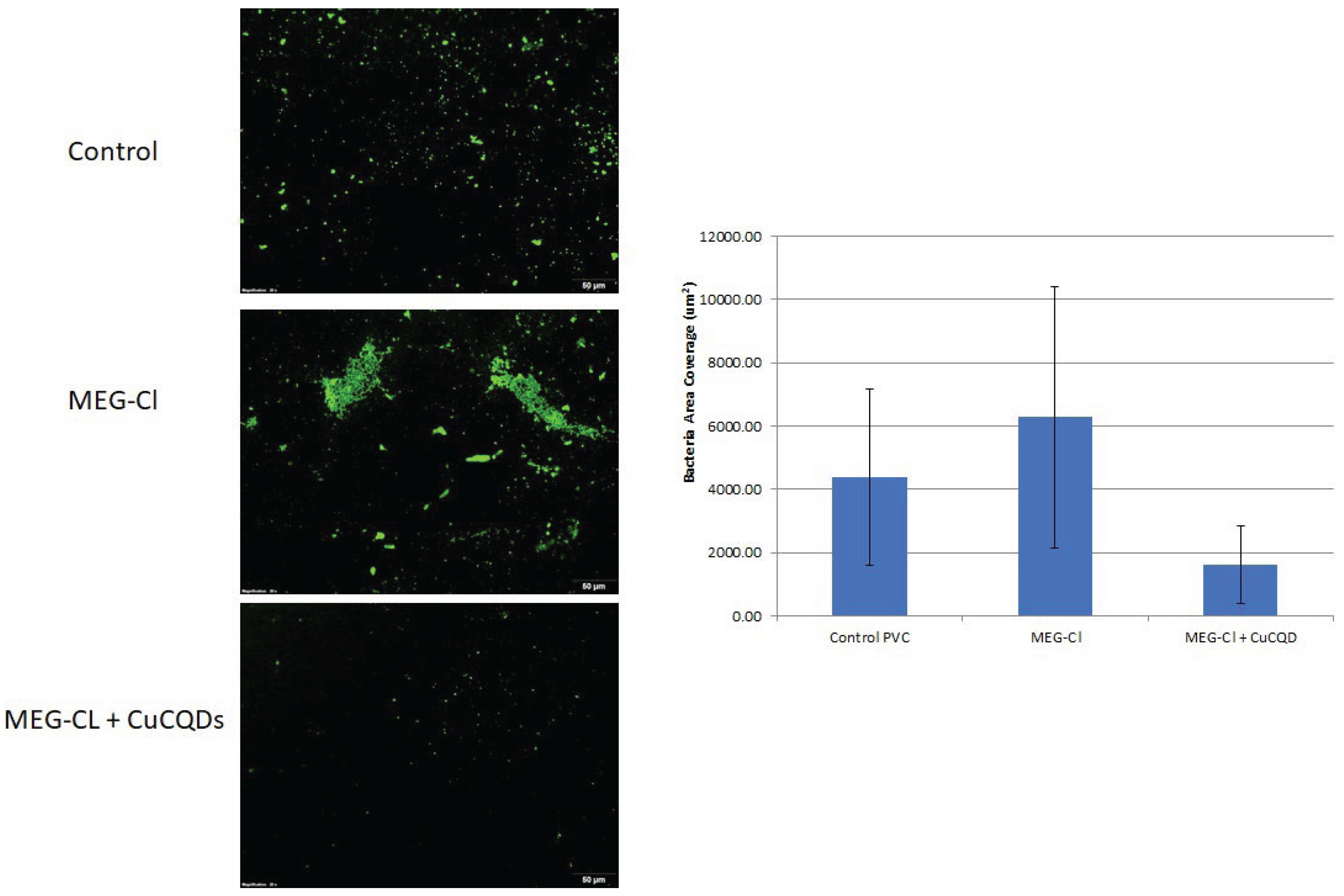

Given these factors, we tried to attach CuCQDs on the surface of the PVC and evaluate the E. coli growth on PVC surface in comparison with the uncoated PVCs. The PVC coupons were observed under the fluorescence microscope and the number of bacteria after 24h of incubation at 37 °C was counted. As it is illustrated in

Figure 6 E. coli growth was significantly reduced. Therefore, it can potentially be as antimicrobial agent without light activation and can be used as coating of the catheter or any other medical devices and even can have potential industrial uses.

Recently, thermoplastic elastomer doped with CQDs has been introduced as antibacterial material suitable for catheters after one hour of exposure to blue light [

30]. They have also been suggested for use in personal medicine and other industries. Additionally, CuCQDs demonstrated significant antibacterial activity (

Figure 6) against E. coli even in the absence of light, making them highly desirable and easily applicable in catheter materials.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a green synthesis approach was utilized to fabricate antibacterial carbon quantum dots (CQDs) using Asafoetida as the primary carbon source. Asafoetida was specifically selected due to its well-documented natural antibacterial properties. Importantly, during the synthesis process, the bioactive functional groups from Asafoetida were preserved on the surface of the CQDs. These functional groups are believed to contribute significantly to the antibacterial performance of the resulting material. The main objective of this work was to develop antibacterial quantum dots that could function effectively without the need for external light activation, offering a practical advantage for real-world applications. Furthermore, the CQDs were doped with copper to enhance their antibacterial efficiency. The resulting copper-doped CQDs derived from Asafoetida exhibited strong and reliable antibacterial activity against tested microorganisms, demonstrating their potential as effective, eco-friendly antibacterial agents.

Compared to traditional extraction methods for deriving antibacterial compounds from plants, CQDs are safe, faster to prepare, and produced in a more environmentally friendly process, as they do not require organic solvents. The hydrothermal method was selected for CQD synthesis due to its higher yield and production of purer quantum dots. Furthermore, copper doping was applied to the CQDs to enhance their antibacterial activity as it was also observed in this study. As-prepared CQDs showed higher antibacterial activity against S. Aureus. Research into antimicrobial coatings aims to prevent bacterial attachment and biofilm formation, offering a promising strategy for long-term infection control in catheterized patients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the immobilization of CQDs on a plastic surface for potential antibacterial and antifouling applications to using medical catheters or other medical devices.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Z. Ramezani; Methodology, Z. Ramezani, B. De La Franier, A. Ameri; Validation and Formal analysis, Z. Ramezani, B. De La Franier; Investigation, Z. Ramerzani, B. De La Franier,, A. Khayat; Resources; Z. Ramezani, M. Thompson, A. Ameri; Writing original draft preparation, A. Khayat, A. Ameri; Writing-Review and editing Z. Ramezani, M. Thompson, B. De La Franier; Supervision, Z. Ramezani, M. Thompson.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

Authors gratefully acknowledged support from both Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences and University of Toronto.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AFM |

Atomic Force Microscope |

| TEM |

Transmision Electron Microscope |

| CQDs |

Carbon quantum dots |

| Cu-CQDs |

Copper-dopped carbon quantum dots |

| CAUTIs |

catheter-associated urinary tract infections |

| PVC |

Poly vinyl chloride |

| MEG-Cl |

|

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| LPS |

Lipopolysaccharides |

| MIC |

minimum inhibitory concentration |

| XPS |

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| GFP |

Green fluorescence protein |

References

- Ventola CL (2015) The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. P & T : a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management 40 (4):277-283.

- Kadam P, Puri S, Kosurkar P (2022) ANTIMICROBIAL EFFECTS OF SILVER NANOPARTICLES SYNTHESIZED USING A TRADITIONAL PHYTOPRODUCT, ASAFOETIDA GUM AGAINST PERIODONTAL OPPORTUNISTIC PATHOGENS. Ann For Res 65 (1):5134-5141.

- Dong X, Liang W, Meziani MJ, Sun YP, Yang L (2020) Carbon Dots as Potent Antimicrobial Agents. Theranostics 10 (2):671-686. [CrossRef]

- Devanesan S, Ponmurugan K, AlSalhi MS, Al-Dhabi NA (2020) Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Efficacy of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized Using a Traditional Phytoproduct, Asafoetida Gum. Int J Nanomedicine 15:4351-4362. [CrossRef]

- Ramezani Z, Thompson M (2023) Quantum Dots in Viral and Bacterial Detection. In: Thompson M, Ramezani Z (eds) Quantum Dots in Bioanalytical Chemistry and Medicine, vol 22. Royal Society of Chemistry, p 0. [CrossRef]

- Thompson M, Ramezani Z (2023) Quantum Dots in Bioanalytical Chemistry and Medicine. RSC,.

- Shahrajabian MH, Sun W, Soleymani A, Khoshkaram M, Cheng Q (2021) Asafoetida, god's food, a natural medicine. Pharmacognosy Communications 11 (1):36-39.

- Shahrajabian MH, Sun W, Cheng Q (2021) Asafoetida, natural medicine for future. Current Nutrition & Food Science 17 (9):922-926.

- Niazmand R, Razavizadeh BM (2021) Ferula asafoetida: chemical composition, thermal behavior, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of leaf and gum hydroalcoholic extracts. J Food Sci Technol 58 (6):2148-2159. [CrossRef]

- KAMATH KA, NASIM I (2020) Antimicrobial Effect of Ferula Asafoetida against Escherichia Coli when Incorporated in Commercially Available Intracanal Medicament-Calcium Hydroxide: An In Vitro Study. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research (09752366).

- Boghrati Z, Iranshahi M (2019) Ferula species: A rich source of antimicrobial compounds. Journal of herbal medicine 16:100244.

- Charu Singh, Parmar RS (2018) Antimicrobial Activity of Resin of Asafoetida (Hing) against Certain Human Pathogenic Bacteria. Advance in Bioresearch 19 (1):161-164. [CrossRef]

- Akhlaghi M, Abbasi M, Safari Y, Amiri R, Yoosefpour N (2018) Data set on the antibacterial effects of the hydro-alcoholic extract of Ferula assafoetida plant on Listeria monocytogenes. Data in brief 20:667-671.

- Bashyal S, Rai S, Abdul O (2017) Invitro analysis of phytochemicals and investigation of antimicrobial activity using crude extracts of Ferula assa-foetida stems. METHODS 4 (12).

- Amalraj A, Gopi S (2017) Biological activities and medicinal properties of Asafoetida: A review. J Tradit Complement Med 7 (3):347-359. [CrossRef]

- De La Franier B, Jankowski A, Thompson M (2017) Functionalizable self-assembled trichlorosilyl-based monolayer for application in biosensor technology. Applied Surface Science 414:435-441. [CrossRef]

- Kumarasamy S, Subramaniam S, Ranganathan M, Rathinavel T, Alagarsamy P (2022) Characterization of Asafoetida Resin Silver Nanoparticles and Efficacy of Antioxidant, Antimicrobial Inhibition. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Nanotechnology(IJPSN) 15 (3). [CrossRef]

- S. D. Patil, S. Shinde, P. Kandpile, Jain AS (2015) EVALUATION OF ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITY OF ASAFOETIDA. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research 6 (2). [CrossRef]

- Kang C-G, Hah D-S, Kim C-H, Kim Y-H, Kim E, Kim J-S (2011) Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity of the Methanol Extracts from 8 Traditional Medicinal Plants. Toxicological Research 27 (1):31-36. [CrossRef]

- Zhu S, Song Y, Zhao X, Shao J, Zhang J, Yang B (2015) The photoluminescence mechanism in carbon dots (graphene quantum dots, carbon nanodots, and polymer dots): current state and future perspective. Nano Research 8 (2):355-381. [CrossRef]

- Ramezani Z, Qorbanpour M, Rahbar N (2018) Green synthesis of carbon quantum dots using quince fruit (Cydonia oblonga) powder as carbon precursor: Application in cell imaging and As3+ determination. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 549:58-66. [CrossRef]

- Etefa HF, Tessema AA, Dejene FB (2024) Carbon Dots for Future Prospects: Synthesis, Characterizations and Recent Applications: A Review (2019–2023). C 10 (3):60.

- Ramezani Z, Thompson M (2023) How Functionalization Affects the Detection Ability of Quantum Dots. In: Thompson M, Ramezani Z (eds) Quantum Dots in Bioanalytical Chemistry and Medicine, vol 22. Royal Society of Chemistry, p 0. [CrossRef]

- Mursyalaat V, Variani VI, Arsyad WOS, Firihu MZ (2023) The development of program for calculating the band gap energy of semiconductor material based on UV-Vis spectrum using delphi 7.0. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2498 (1). [CrossRef]

- Khalil Z, Farrukh MA (2021) An efficient nanofiltration system containing mixture of rice husk ash and Fe/CeO2–SiO2 nanocomposite for the removal of azo dye and pesticide. Pure and Applied Chemistry 93 (5):607-621. doi:doi:10.1515/pac-2020-1003.

- Trautner BW, Darouiche RO (2004) Role of biofilm in catheter-associated urinary tract infection. American journal of infection control 32 (3):177-183. [CrossRef]

- Patra D, Ghosh S, Mukherjee S, Acharya Y, Mukherjee R, Haldar J (2024) Antimicrobial nanocomposite coatings for rapid intervention against catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Nanoscale 16 (23):11109-11125. [CrossRef]

- Won D-S, Lee H, Park Y, Chae M, Kim Y-C, Lim B, Kang M-H, Ok M-R, Jung H-D, Park J-H (2024) Dual-Layer Nanoengineered Urinary Catheters for Enhanced Antimicrobial Efficacy and Reduced Cytotoxicity. Advanced Healthcare Materials 13 (31):2401700. [CrossRef]

- Tailly T, MacPhee RA, Cadieux P, Burton JP, Dalsin J, Wattengel C, Koepsel J, Razvi H (2021) Evaluation of Polyethylene Glycol-Based Antimicrobial Coatings on Urinary Catheters in the Prevention of Escherichia coli Infections in a Rabbit Model. Journal of endourology 35 (1):116-121. [CrossRef]

- Shaalan M, Vykydalová A, Švajdlenková H, Kroneková Z, Marković ZM, Kováčová M, Špitálský Z (2024) Antibacterial activity of 3D printed thermoplastic elastomers doped with carbon quantum dots for biomedical applications. Polymer Bulletin 81 (14):13009-13025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).