Submitted:

25 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

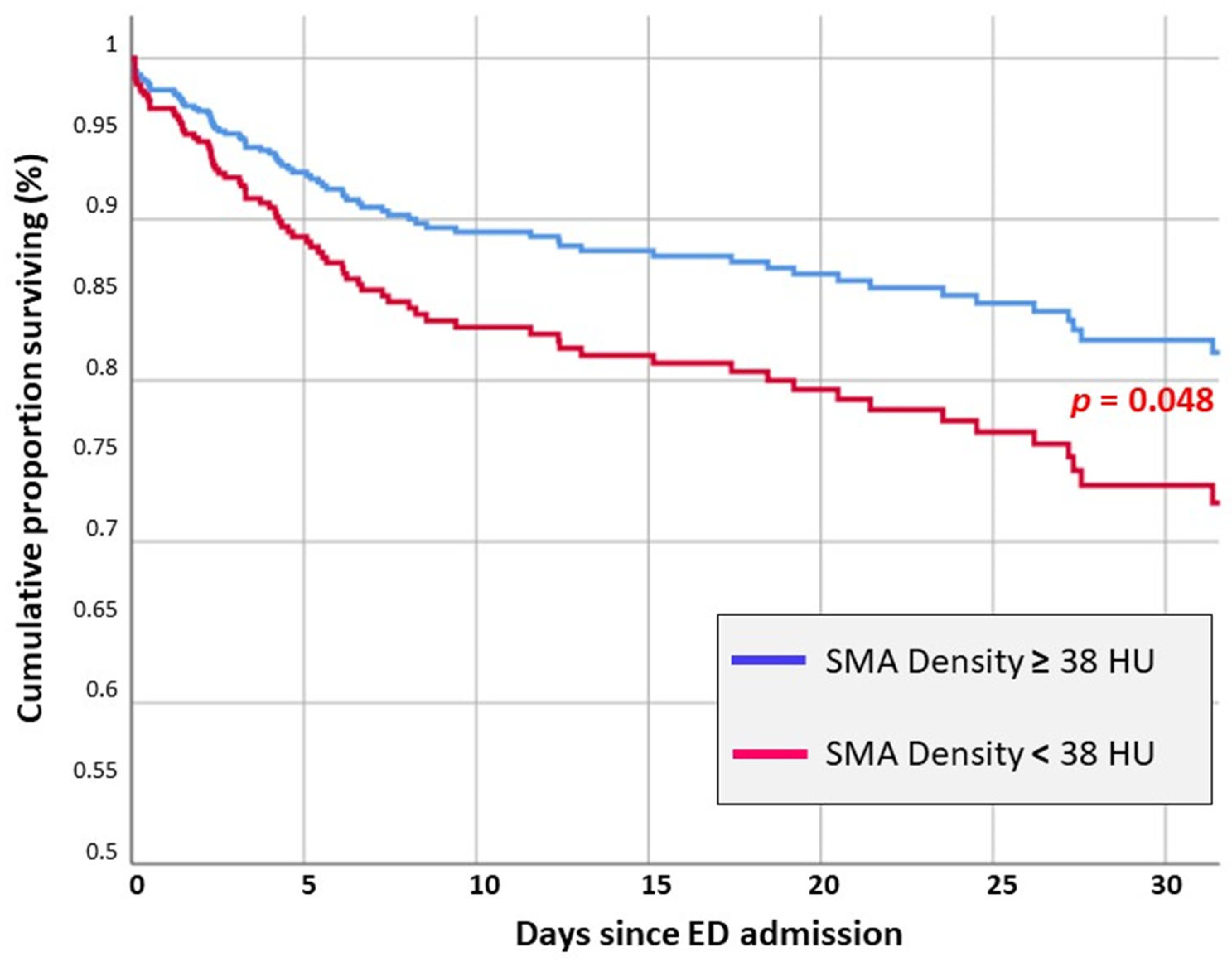

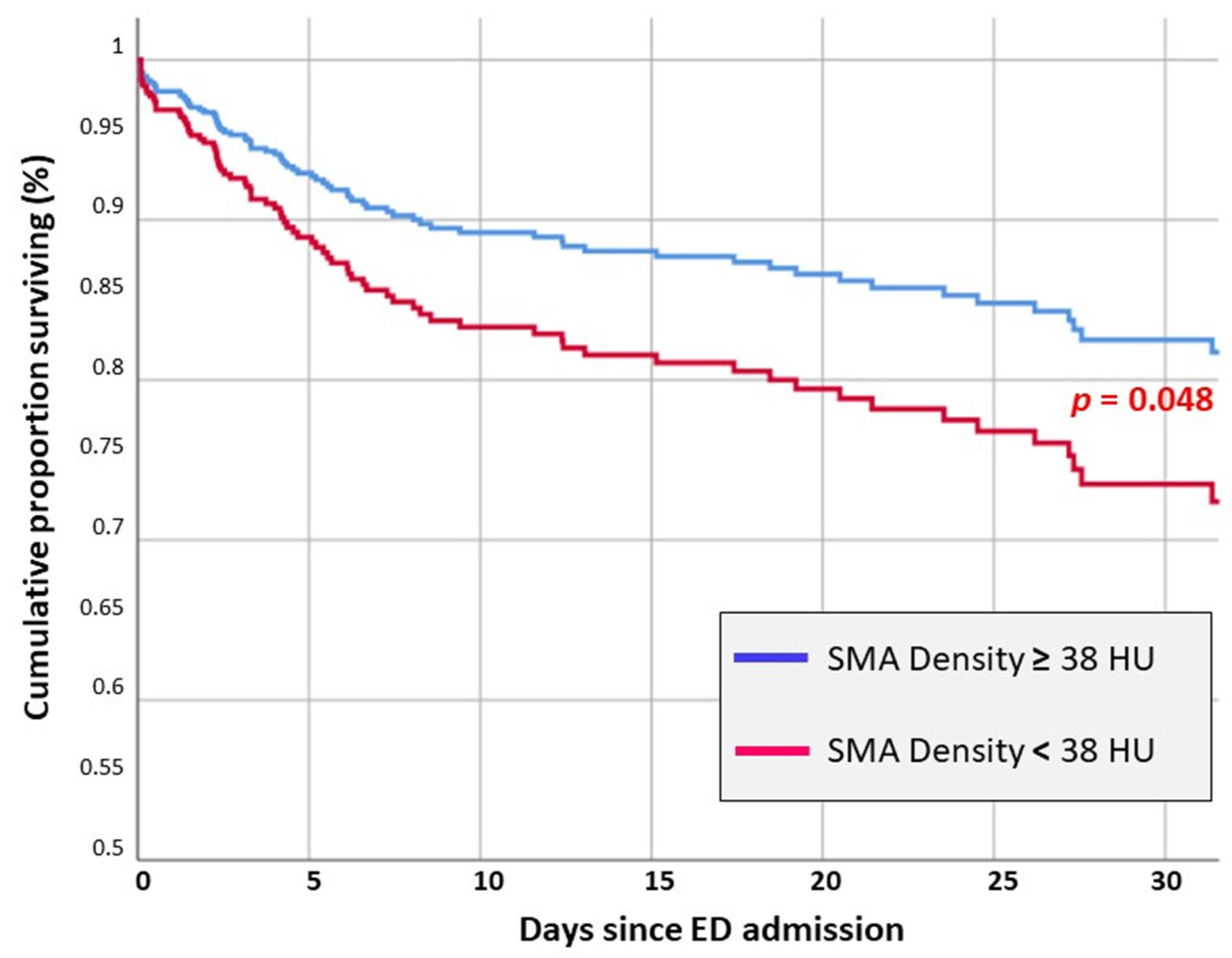

Background: In patients over 65 years who experience severe trauma the underlying health status has a significant impact on overall mortality. This study aims to assess if CT evaluation of skeletal muscle quality could be a risk stratification tool in the ED for these patients. Methods: Retrospective observational study between January 2018 and September 2021, including consecutive patients ≥ 65 years admitted to the ED for a major trauma (defined as Injury Severity Score > 15). Muscle quality analysis was made by specific software (Slice-O-Matic v5.0, Tomovision®, Montreal, QC, Canada) on a CT-Scan slice at the level of the third lumbar vertebra. Results: 263 patients were included (72.2% males, median age 76 [71-82]), and 88 (33.5%) deceased. The deceased patients had a significantly lower skeletal muscle area density (SMAd) compared to survivors. The multivariate Cox regression analysis confirmed that SMAd < 38 at the ED admission was an independent risk for death (adjusted HR 1.68 [1.1 – 2.7]). The analysis also revealed that, among the survivors after the first week of hospitalization, the patients with low SMAd had an increased risk of death (adjusted HR 3.12 [1.2 – 7.9]). Conclusions: The skeletal muscle density evaluated by a CT scan at ED admission could be a valuable risk stratification tool for patients ≥ 65 years with major trauma. In patients with SMAd <38 HU the in-hospital mortality risk could be particularly increased after the first week of hospitalization.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Variables

- Demographic data, including age and sex;

- Physiological parameters at ED admission including Glasgow Coma Scale, Respiratory rate, Systolic blood pressure;

- Acute Injury Scale (AIS) scores and the Injury Severity Score (ISS). The scores were blindly calculated for each patient by three authors (MP, LF, GT) based on the clinical records and the radiological findings.

- Information about clinical history and comorbidities was assessed with the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), a validated score used to predict the risk of death one year after hospitalization in patients with a high comorbidities burden.

- The average length of stay (LOS) was calculated from the time of the ED admission to the time of discharge or death.

- Laboratory tests, including hemoglobin, white blood cells, platelet count, fibrinogen, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, glucose, creatinine, urea, nitrogen, and blood gas analysis results (pH, lactates, bicarbonates)

- Assessment of muscle quality. Body composition analysis was performed on a single axial CT-Scan slice (DICOM image format) at the level of the third lumbar vertebra (L3), using specific software (Slice-O-Matic v5.0, Tomovision®, Montreal, QC, Canada). Image analysis was performed by two investigators with over five years imaging experience and blinded to outcomes, to minimize the introduction of bias. The cross-sectional area of skeletal muscle (SMA), subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT), and visceral adipose tissue (VAT) were analyzed based on pre-established thresholds of Hounsfield Units (HU): SMA - 29 to 150, SAT - 190 to - 30, and VAT - 150 to - 50. Skeletal muscle area density (SMAd) was calculated by finding the mean of the HU of SMA. Similarly, the mean HU density was calculated for VAT (VATd), and SAT (SATd)[21]. Supplementary Figure S1 shows a sample of the CT images used for the calculations.

2.2. Study Endpoints

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Study Cohort and Baseline Characteristic

3.2. Muscular Quality Assessment

3.3. Multivariate Analysis for Survival

3.4. Early and Late Mortality Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ED | Emergency Department |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| ISS | Injury Severity Score |

| AIS | Acute Injury Scale |

| CCI | Charson Comorbidity Index |

| LOS | Length of Stay |

| SMA | Skeletal Muscle Area |

| SAT | Subcutaneous Adipose tissue |

| VAT | Visceral Adipose tissue |

| HU | Hounsfield Units |

| SMAd | Skeletal Muscle Area Density |

| VATd | Visceral Muscle Area Density |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

References

- Bengtsson, T.; Scott, K. Population aging and the future of the welfare state: the example of Sweden. Population and Development Review 2011, 37, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanasi, E.; Ayilavarapu, S.; Jones, J. The aging population: demographics and the biology of aging. Periodontology 2000 2016, 72, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenvi, C.L.; Platts-Mills, T.F. Managing the Elderly Emergency Department Patient. Annals of emergency medicine 2019, 73, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonne, S.; Schuerer, D.J. Trauma in the older adult: epidemiology and evolving geriatric trauma principles. Clinics in geriatric medicine 2013, 29, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, A. Trauma in the elderly: Burden or opportunity? Injury 2015, 46, 1701–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Eurostat - Accidents and injuries statistics - https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Accidents_and_injuries_statistics#Deaths_from_accidents.2C_injuries_and_assault (Accessed on January 9, 2024).

- American College of Surgeon - National Trauma Database Registry - https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/quality/national-trauma-data-bank/reports-and-publications/ (Accessed on January 9, 2024).

- Fogel, J.F.; Hyman, R.B.; Rock, B.; Wolf-Klein, G. Predictors of hospital length of stay and nursing home placement in an elderly medical population. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2000, 1, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stonko, D.P.; Etchill, E.W.; Giuliano, K.A.; DiBrito, S.R.; Eisenson, D.; Heinrichs, T.; Morrison, J.J.; Haut, E.R.; Kent, A.J. Failure to Rescue in Geriatric Trauma: The Impact of Any Complication Increases with Age and Injury Severity in Elderly Trauma Patients. The American surgeon 2021, 87, 1760–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loftus, T.J.; Brakenridge, S.C.; Murphy, T.W.; Nguyen, L.L.; Moore, F.A.; Efron, P.A.; Mohr, A.M. Anemia and blood transfusion in elderly trauma patients. The Journal of surgical research 2018, 229, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, D.J.; Schwab, C.W.; Kauder, D. Comorbidity and the elderly trauma patient. World journal of surgery 1996, 20, 1113–1119; discussion 1119-1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucoin, S.; McIsaac, D.I. Emergency General Surgery in Older Adults: A Review. Anesthesiol Clin. 2019, 37, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, C.Y.; Bajani, F.; Bokhari, M.; Starr, F.; Messer, T.; Kaminsky, M.; Dennis, A.; Schlanser, V.; Mis, J.; Poulakidas, S.; et al. Age itself or age-associated comorbidities? A nationwide analysis of outcomes of geriatric trauma. European journal of trauma and emergency surgery : official publication of the European Trauma Society 2022, 48, 2873–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences 2001, 56, M146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqarni, A.G.; Gladman, J.R.F.; Obasi, A.A.; Ollivere, B. Does frailty status predict outcome in major trauma in older people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2023, 52, afad073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marzetti, E.; Calvani, R.; Tosato, M.; Cesari, M.; Di Bari, M.; Cherubini, A.; Collamati, A.; D'Angelo, E.; Pahor, M.; Bernabei, R.; et al. Sarcopenia: an overview. Aging clinical and experimental research 2017, 29, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliafico, A.S.; Bignotti, B.; Torri, L.; Rossi, F. Sarcopenia: how to measure, when and why. La Radiologia medica 2022, 127, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picca, A.; Coelho-Junior, H.J.; Calvani, R.; Marzetti, E.; Vetrano, D.L. Biomarkers shared by frailty and sarcopenia in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing research reviews 2022, 73, 101530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza-Valderrama, D.; Marco, E.; Dávalos-Yerovi, V.; Muns, M.D.; Tejero-Sánchez, M.; Duarte, E.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, D. Sarcopenia, Malnutrition, and Cachexia: Adapting Definitions and Terminology of Nutritional Disorders in Older People with Cancer. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Zhao, R.; Wan, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Shen, X.; Wu, X. Sarcopenia and adverse health-related outcomes: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. Cancer medicine 2020, 9, 7964–7978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covino, M.; Salini, S.; Russo, A.; De Matteis, G.; Simeoni, B.; Maccauro, G.; Sganga, G.; Landi, F.; Gasbarrini, A.; Franceschi, F. Frailty Assessment in the Emergency Department for Patients ≥80 Years Undergoing Urgent Major Surgical Procedures. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022, 23, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covino, M.; Russo, A.; Salini, S.; De Matteis, G.; Simeoni, B.; Della Polla, D.; Sandroni, C.; Landi, F.; Gasbarrini, A.; Franceschi, F. Frailty Assessment in the Emergency Department for Risk Stratification of COVID-19 Patients Aged ≥80 Years. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021, 22, 1845–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chianca, V.; Albano, D.; Messina, C.; Gitto, S.; Ruffo, G.; Guarino, S.; Del Grande, F.; Sconfienza, L.M. Sarcopenia: imaging assessment and clinical application. Abdominal radiology (New York) 2022, 47, 3205–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardito, F.; Coppola, A.; Rinninella, E.; Razionale, F.; Pulcini, G.; Carano, D.; Cintoni, M.; Mele, M.C.; Barbaro, B.; Giuliante, F. Preoperative Assessment of Skeletal Muscle Mass and Muscle Quality Using Computed Tomography: Incidence of Sarcopenia in Patients with Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma Selected for Liver Resection. Journal of clinical medicine 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardoscia, L.; Besutti, G.; Pellegrini, M.; Pagano, M.; Bonelli, C.; Bonelli, E.; Braglia, L.; Cozzi, S.; Roncali, M.; Iotti, C.; et al. Impact of low skeletal muscle mass and quality on clinical outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing (chemo)radiation. Frontiers in nutrition 2022, 9, 994499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sueyoshi, Y.; Ogawa, T.; Koike, M.; Hamazato, M.; Hokama, R.; Tokashiki, S.; Nakayama, Y. Improved activities of daily living in elderly patients with increased skeletal muscle mass during vertebral compression fracture rehabilitation. European geriatric medicine 2022, 13, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazzini, B.; Märkl, T.; Costas, C.; Blobner, M.; Schaller, S.J.; Prowle, J.; Puthucheary, Z.; Wackerhage, H. The rate and assessment of muscle wasting during critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2023, 27, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xi, F.; Tan, S.; Gao, T.; Ding, W.; Sun, J.; Wei, C.; Li, W.; Yu, W. Low skeletal muscle mass predicts poor clinical outcomes in patients with abdominal trauma. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.) 2021, 89, 111229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.J.; Martinez, P.F.; Pagan, L.U.; Damatto, R.L.; Cezar, M.D.M.; Lima, A.R.R.; Okoshi, K.; Okoshi, M.P. Skeletal muscle aging: influence of oxidative stress and physical exercise. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 20428–20440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazaud, B. Inflammation and Skeletal Muscle Regeneration: Leave It to the Macrophages! Trends in immunology 2020, 41, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianci, R.; Franza, L.; Massaro, M.G.; Borriello, R.; Tota, A.; Pallozzi, M.; De Vito, F.; Gambassi, G. The Crosstalk between Gut Microbiota, Intestinal Immunological Niche and Visceral Adipose Tissue as a New Model for the Pathogenesis of Metabolic and Inflammatory Diseases: The Paradigm of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Current medicinal chemistry 2022, 29, 3189–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, J.M.; Gavitt, B.J.; Nomellini, V.; Dobson, G.P.; Letson, H.L.; Shackelford, S.A. Immunotherapeutic options for inflammation in trauma. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery 2020, 89, S77–s82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamboni, M.; Nori, N.; Brunelli, A.; Zoico, E. How does adipose tissue contribute to inflammageing? Experimental gerontology 2021, 143, 111162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granic, A.; Sayer, A.A.; Robinson, S.M. Dietary Patterns, Skeletal Muscle Health, and Sarcopenia in Older Adults. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, F.; Domingos, C.; Monteiro, D.; Morouço, P. A Review on Aging, Sarcopenia, Falls, and Resistance Training in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. International journal of environmental research and public health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzoccoli, G. Body composition: Where and when. European journal of radiology 2016, 85, 1456–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akazawa, N.; Okawa, N.; Hino, T.; Tsuji, R.; Tamura, K.; Moriyama, H. Higher malnutrition risk is related to increased intramuscular adipose tissue of the quadriceps in older inpatients: A cross-sectional study. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2020, 39, 2586–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioffrè-Florio, M.; Murabito, L.M.; Visalli, C.; Pergolizzi, F.P.; Famà, F. Trauma in elderly patients: a study of prevalence, comorbidities and gender differences. Il Giornale di chirurgia 2018, 39, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, F.; Wilson, A.; Bailey, M.; Pilcher, D.; Gabbe, B.; Bellomo, R. Comparison of Intensive Care and Trauma-specific Scoring Systems in Critically Ill Patients. Injury. 2021, 52, 2543–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kehoe, A.; Rennie, S.; Smith, J.E. Glasgow Coma Scale is unreliable for the prediction of severe head injury in elderly trauma patients. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ 2015, 32, 613–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochems, D.; Leenen, L.P.H.; Hietbrink, F.; Houwert, R.M.; van Wessem, K.J.P. Increased reduction in exsanguination rates leaves brain injury as the only major cause of death in blunt trauma. Injury. 2018, 49, 1661–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brohi, K.; Gruen, R.L.; Holcomb, J.B. Why are bleeding trauma patients still dying? Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45, 709–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsden, M.; Carden, R.; Navaratne, L.; Smith, I.M.; Penn-Barwell, J.G.; Kraven, L.M.; Brohi, K.; Tai, N.R.M.; Bowley, D.M. Outcomes following trauma laparotomy for hypotensive trauma patients: A UK military and civilian perspective. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018, 85, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvin, J.A.; Maxim, T.; Inaba, K.; Martinez-Aguilar, M.A.; King, D.R.; Choudhry, A.J.; Zielinski, M.D.; Akinyeye, S.; Todd, S.R.; Griffin, R.L.; Kerby, J.D.; Bailey, J.A.; Livingston, D.H.; Cunningham, K.; Stein, D.M.; Cattin, L.; Bulger, E.M.; Wilson, A.; Undurraga Perl, V.J.; Schreiber, M.A.; Cherry-Bukowiec, J.R.; Alam, H.B.; Holcomb, J.B. Mortality after emergent trauma laparotomy: A multicenter, retrospective study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017, 83, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Seyfer, A.E.; Seaber, A.V.; Dombrose, F.A.; Urbaniak, J.R. Coagulation changes in elective surgery and trauma. Annals of surgery 1981, 193, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, R.K.; Rizor, J.H.; Damiani, M.P.; Powers, A.J.; Fagnani, J.T.; Monie, D.L.; Cooper, S.S.; Griffiths, A.D.; Hellenthal, N.J. The Impact of Anticoagulation on Trauma Outcomes : An National Trauma Data Bank Study. The American surgeon 2020, 86, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, P.C.; Dixon, B.E.; Savage, S.A.; Carroll, A.E.; Newgard, C.D.; Tignanelli, C.J.; Hemmila, M.R.; Timsina, L. Comparison of a trauma comorbidity index with other measures of comorbidities to estimate risk of trauma mortality. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine 2021, 28, 1150–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkbuli, A.; Yaras, R.; Elghoroury, A.; Boneva, D.; Hai, S.; McKenney, M. Comorbidities in Trauma Injury Severity Scoring System: Refining Current Trauma Scoring System. The American surgeon 2019, 85, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.W.; Muller, A.; Sigal, A.; Fernandez, F. Anemia at Discharge in Elderly Trauma Patients Is Not Associated with Six-Month Mortality. The American surgeon 2019, 85, 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungor, O.; Ulu, S.; Hasbal, N.B.; Anker, S.D.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Effects of hormonal changes on sarcopenia in chronic kidney disease: where are we now and what can we do? J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2021, 12, 1380–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

All Patients n 263 |

Survived n 175 |

Deceased n 88 |

p value |

|

| Age | 76 [71-82] | 75 [69-81] | 78 [74-85] | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 179 (72.2%) | 132 (75.4%) | 47 (64.4%) | 0.088 |

| Injury severity | ||||

| ISS | 26 [20-33] | 25 [17-33] | 29 [25-33] | <0.001 |

| AIS Head Neck | 3 [2-5] | 3 [0-4] | 5 [4-5] | <0.001 |

| AIS Face | 0 [0-2] | 0 [0-2] | 0 [0-1.5] | 0.724 |

| AIS Chest | 2 [0-4] | 2 [0-4] | 0 [0-3] | 0.066 |

| AIS Abdomen | 0 [0-0] | 0 [0-2] | 0 [0-0] | 0.124 |

| AIS Pelvi-Extremity | 0 [0-2] | 1 [0-3] | 0 [0-2] | 0.028 |

| AIS External | 0 [0-1] | 1 [0-1] | 0 [0-1] | 0.027 |

| APACHE II | 20 [15-26] | 17 [14-21] | 27 [24-30] | <0.001 |

| Laboratory Values at ED admission | ||||

| Hb (mg/dL) | 12.8 [11.2-14] | 13.1 [11.4-14.2] | 11.9 [10.2-13.5] | <0.001 |

| WBC (*109) | 13.2 [9.19-16.84] | 13.3 [9.48-16.47] | 12.6 [9-19.5] | 0.638 |

| PLT | 205 [156-257] | 208 [169-253] | 183 [148-268] | 0.319 |

| Fibrinogen | 287 [250-335] | 285 [252-327] | 290 [244-365] | 0.421 |

| aPTT | 28.6 [25.5-34.4] | 27.2 [24.9-31.7] | 33.6 [28.5-39.5] | <0.001 |

| Glucose | 158 [133-207] | 152 [131-200] | 170 [135-209] | 0.081 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.01 [0.8-1.26] | 1 [0.8-1.23] | 1.05 [0.8-1.36] | 0.437 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 20 [17-24] | 20 [17-24] | 20.5 [18-28.8] | 0.574 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 2.5 [1.8-3.5] | 2.5 [1.8-3.4] | 2.7 [1.7-7.8] | 0.725 |

| Muscular parameters at CT scan evaluation | ||||

| SMA | 151.2 [122.5 / 170.5] | 153.8 [127.7 / 169.8] | 140.5 [112.3 / 173.9] | 0.204 |

| VAT Area | 144.3 [77.2 / 218.9] | 158.9 [87.9 / 222.3] | 128.3 [77.9 / 202.1] | 0.112 |

| SAT Area | 150.9 [110.2 / 207.5] | 154.4 [113.3 / 211.45] | 142 [98.67 / 191.1] | 0.119 |

| SMA Density | 41.6 [34.72 / 47.8] | 41.9 [35.9 / 48.1] | 37.9 [32.2 / 45.7] | 0.009 |

| VAT Density | -83.4 [-87.2 / -78.0] | -83.9 [-87.9 / -79.5] | -82.5 [-86.1 / -75.6] | 0.047 |

| SAT Density | -85.0 [-89.0 / -78.9] | -85.7 [-89.8 / -80.0] | -82.6 [-87.8 / -77.8] | 0.029 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| CCI | 4 [3-5] | 4 [3-5] | 4 [3-5] | 0.053 |

| History of CAD | 19 (7.7%) | 14 (8%) | 5 (6.8%) | 1.000 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 5 (2%) | 2 (1.1%) | 3 (4.1%) | 0.154 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 26 (10.5%) | 17 (9.7%) | 9 (12.3%) | 0.649 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 13 (5.2%) | 8 (4.6%) | 5 (6.8%) | 0.534 |

| Dementia | 8 (3.2%) | 5 (2.9%) | 3 (4.1%) | 0.696 |

| COPD | 30 (12.1%) | 25 (14.3%) | 5 (6.8%) | 0.134 |

| Diabetes | 3 (13.7%) | 24 (13.7%) | 10 (13.7%) | 1.000 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 20 (8.1%) | 10 (5.7%) | 10 (13.7%) | 0.043 |

| Malignancy | 17 (6.9%) | 13 (7.4%) | 4 (5.5%) | 0.784 |

|

ROC Curve Area |

p value |

Youden Index Cut-Off Value |

Sensitivity [95% CI] |

Specificity [95% CI] |

|

| Age | 0.638 [0.577 – 0.696] |

<0.001 | > 75 | 69.3 [58.6 – 78.7] |

52.0 [44.3 – 59.6] |

| ISS | 0.649 [0.588 – 0.707] |

<0.001 | < 24 | 82.9 [73.4 – 90.1] |

42.9 [35.4 – 50.5] |

| APACHE II | 0.939 [0.902 – 0.964] |

<0.001 | > 22 | 82.9 [73.4 – 90.1] |

86.9 [80.9 – 91.5] |

| aPTT | 0.727 [0.669 – 0.780] |

<0.001 | > 31.6 | 64.7 [53.9 – 74.7] |

74.8 [67.8 – 81.1] |

| Muscular CT scan parameter | |||||

| SMA Density | 0.599 [0.537 – 0.658] |

0.038 | < 38 | 52.3 [41.4 – 63.0] |

73.1 [65.9 – 79.6] |

| VAT Density | 0.575 [0.513 – 0.635] |

0.047 | > -77 | 31.8 [22.3 – 42.6] |

82.8 [76.4 – 88.1] |

| SAT Density | 0.582 [0.520 – 0.643] |

0.026 | > -83 | 51.4 [40.2 – 61.9] |

63.4 [55.8 – 70.6] |

| Variable | Beta | Wald | Odds Ratio [95% CI] | p |

| Age > 75 years | 0.327 | 1.330 | 1.39 [0.79 – 2.42] | 0.249 |

| ISS > 24 | 1.054 | 12.905 | 2.87 [1.61 – 5.10] | <0.001 |

| APACHE II > 22 | 2.048 | 45.426 | 7.75 [4.27 – 14.07] | <0.001 |

| aPTT > 31.6” | 0.579 | 5.251 | 1.78 [1.09 – 2.93] | 0.022 |

| SMA Density <38 HU | 0.519 | 4.836 | 1.68 [1.06 – 2.67] | 0.028 |

| SAT Density > -83 HU | 0.149 | 0.311 | 1.16 [0.68 – 1.96] | 0.577 |

| VAT Density > -77 HU | 0.197 | 0.466 | 1.22 [0.69 – 2.14] | 0.495 |

| Model 1 – Factors affecting mortality risk within 7 days since admission | ||||

| Variable | Beta | Wald | Hazard Ratio [95% CI] | p |

| Age > 75 | 0.632 | 3.837 | 1.88 [1.00 – 3.54] | 0.050 |

| ISS > 24 | 1.320 | 10.186 | 3.74 [1.66 – 8.41] | 0.001 |

| APACHE II > 22 | 1.528 | 18.736 | 4.61 [2.31 – 9.20] | <0.001 |

| aPTT > 31.6” | 0.684 | 5.019 | 1.98 [1.09 – 3.61] | 0.025 |

| SMA Density <38 HU | 0.239 | 0.724 | 1.27 [0.73 – 2.20] | 0.395 |

| SAT Density > -83 HU | -0.047 | 0.019 | 0.89 [0.48 – 1.88] | 0.891 |

| VAT Density > -77 HU | -0.243 | 0.408 | 0.78 [0.37 – 1.65] | 0.523 |

| Model 2 – Factors affecting mortality risk starting from 7 days since admission. The cases deceased within days were considered as “censored” in this regression model. | ||||

| Variable | Beta | Wald | Hazard Ratio [95% CI] | p |

| Age > 75 | 0.167 | 0.162 | 1.18 [0.52 – 2.66] | 0.688 |

| ISS > 24 | 0.669 | 2.370 | 1.95 [0.83 – 4.57] | 0.124 |

| APACHE II > 22 | 3.096 | 22.637 | 22.11 [6.18 – 79.15] | <0.001 |

| aPTT > 31.6” | 0.064 | 0.016 | 1.06 [0.39 – 2.90] | 0.900 |

| SMA Density <38 HU | 1.137 | 5.771 | 3.12 [1.23 – 7.88] | 0.016 |

| SAT Density > -83 HU | -0.350 | 0.386 | 0.71 [0.23 – 2.12] | 0.534 |

| VAT Density > -77 HU | -0.019 | 0.001 | 0.98 [0.29 – 3.34] | 0.976 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).