1. Introduction

Sarcopenia is a skeletal muscle disorder characterized by the progressive loss of muscle mass, strength, and function[

1,

2]. The European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2) has established a diagnostic algorithm that includes the assessment of muscle strength, mass, and quality[

3]. Classified as a disease in the ICD-10-CM[

4], sarcopenia is common among older adults due to the progressive decline in skeletal muscle tissue beginning around the age of 40, increasing the risk of frailty and functional dependence[

5,

6].

Sarcopenia is associated with multiple comorbidities, including cancer[

7], obesity[

8,

9], and renal and cardiovascular diseases[

10]. Its prevalence is difficult to determine due to the wide range of diagnostic methods, such as the SARC-F questionnaire, bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA)[

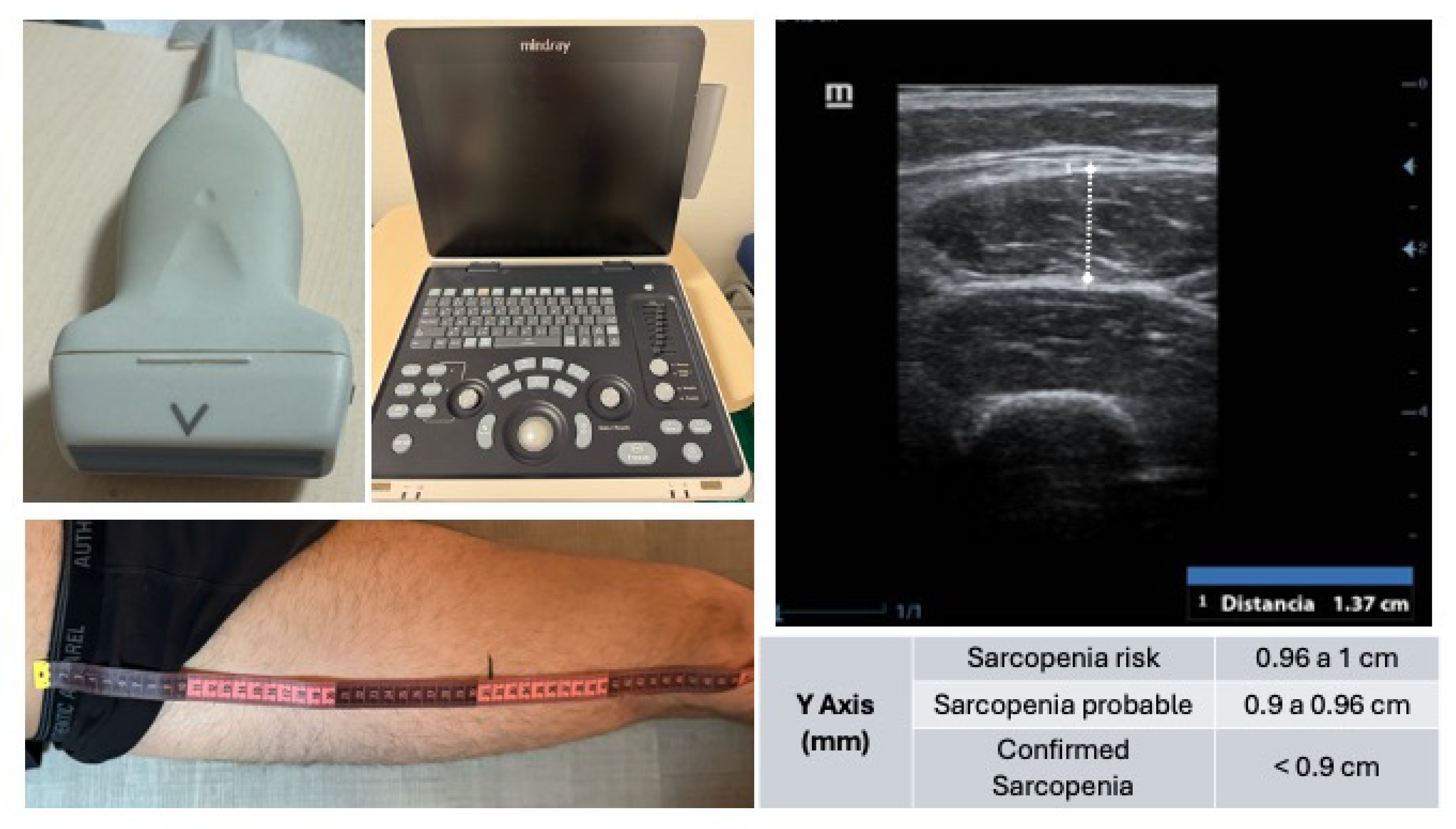

1]. Muscle ultrasound is a radiation-free, accessible tool used to measure rectus femoris thickness as a marker of sarcopenia[

11].

Cardiovascular diseases such as heart failure and peripheral arterial disease may contribute to sarcopenia due to factors like oxidative stress and malnutrition[

12]. Likewise, cardiac surgery can lead to muscle mass loss due to immobilization[

10]. In respiratory conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), dyspnea and chronic inflammation worsen sarcopenia[

13]. There is also evidence of higher sarcopenia prevalence in patients with malignant digestive diseases[

14] and in oncology patients with cachexia, a metabolic syndrome involving loss of muscle mass and body weight[

15,

16].

Trauma is also associated with sarcopenia, as appropriate nutritional support can reduce rehabilitation time in cases such as hip fractures[

16]. Among metabolic disorders, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) contributes to sarcopenia through insulin resistance and lipid-induced muscle dysfunction[

17].

Given the clinical relevance of this condition, the present study aimed to evaluate the relationship between sarcopenia and various pathologies in patients admitted to the emergency department, to identify which diseases are associated with higher sarcopenia indices, and to determine the related in-hospital complications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was an observational, prospective, comparative, and cross-sectional study conducted at the Infanta Cristina University Hospital in Parla (Madrid, Spain). Sarcopenia was assessed by ultrasound, performed under the supervision of a liaison nurse, in all patients who presented to the emergency department. The results were compared across the different diagnosed pathologies.

This study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Puerta de Hierro University Hospital (ACT 245.23, 24/11/2023).

2.2. Study Population

The nutritional ultrasound program for the diagnosis of sarcopenia was implemented at the hospital in 2021. All patients presenting to the emergency department were evaluated using ultrasound, except for those who did not meet the inclusion criteria.

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

The study included all patients aged 18 years or older who presented to the Emergency Department of Infanta Cristina University Hospital between January and May 2023. To be eligible, patients had to be in stable clinical condition, allowing for ultrasound evaluation during their emergency department stay—either during prolonged observation or prior to hospital admission. Additionally, patients were required to have sufficient cognitive capacity to understand the information provided about the procedure and to give verbal consent for the assessment.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Patients were excluded from the study if, at the time of evaluation, they were in cardiac arrest (resuscitation bay), exhibited hemodynamic instability that precluded immediate ultrasound assessment, presented with an acute psychiatric condition that impaired cooperation, or had clinical presentations classified as high-resolution cases, where the short duration of stay in the emergency department did not allow for completion of the sarcopenia measurement protocol.

2.3. Sample Size

Assuming a 15% loss rate, a 95% confidence level, a 3% margin of error, and a 5% estimated proportion, an appropriate sample size of 150 participants was calculated.

2.4. Studied Variables

The following sociodemographic and clinical variables were collected: sex (male, female), age, nutritional ultrasound measurements of the rectus femoris (Y-axis, X-axis, and cross-sectional area), antidiabetic medication (metformin, sulfonylureas, sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (iSGLT2) inhibitors, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (iDPP-4) inhibitors, insulin, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1Ra) receptor agonists, and their respective combinations), reason for admission or observation (cardiovascular, respiratory, endocrine-metabolic, digestive, oncological, neurological, orthopedic, urological, hematological), and personal medical history (yes/no) of cardiovascular disease, digestive disease, respiratory disease, urological disease, hematological disease, neurological disease, diabetes mellitus, and active cancer.

Clinical outcomes assessed included: hospital admission (yes/no), C-reactive protein (CRP), lymphocyte count, total protein, albumin, development of complications (yes/no), type of complication (infectious, respiratory, cardiovascular), and in-hospital mortality (yes/no).

2.5. Intervention

All patients included in the study underwent a nutritional ultrasound assessment aimed at estimating their degree of sarcopenia. Prior to the procedure, each patient’s capacity to understand the purpose, implications, and rationale for their inclusion in the program was evaluated to ensure adequate informed cooperation.

The ultrasound examination was performed during the emergency department stay, either when the patient required prolonged observation or had a pending hospital admission. At the same time, relevant clinical data were collected, including the reason for admission, personal medical history, and current medications.

The muscle ultrasound was conducted using a Mindray Z50® ultrasound system equipped with a linear transducer, optimized for high-resolution imaging of superficial skeletal muscle tissue. The patient was placed in a supine position with the lower limbs relaxed to minimize muscle tension.

The anatomical reference points for the measurement were the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and the superior border of the patella. The total distance between these landmarks was measured, and the probe was positioned at the junction of the distal third of this segment, a location providing optimal visualization of the rectus femoris muscle (

Figure 1).

After applying conductive gel to the skin, the transducer was placed perpendicularly to the muscle fibers in the transverse (short-axis) plane. Great care was taken to avoid any probe angulation, as oblique positioning can lead to erroneous measurements. Once the muscle architecture was clearly identified—typically including the skin, subcutaneous tissue, vastus lateralis, rectus femoris, and femoral bone interface—the image was frozen and the anteroposterior thickness of the rectus femoris (Y-axis) was measured, along with other optional parameters (X-axis, cross-sectional area).

Following the ultrasound assessment, relevant laboratory values (e.g., C-reactive protein, lymphocyte count, total protein, and albumin levels) were recorded from the electronic health records. Additionally, at one month post-admission, a retrospective review of the patients’ clinical course was conducted to identify any in-hospital complications (e.g., infections, cardiovascular or respiratory events) and to register mortality (exitus) where applicable.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All study variables were examined to assess their distribution. Categorical variables were described using the percentage associated with each response option, while quantitative variables were summarized using the mean, standard deviation (SD), and range. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 29 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Population

A total of 150 patients were included. Among the participants, 52.00% were male. The mean age was 70.70 years (SD 18.15). Thirty percent of participants were diabetic, of whom 24.00% were treated with oral antidiabetic agents, with metformin being the most commonly used (8.70%). Additionally, 30.70% of the patients had a cancer diagnosis. The most frequent comorbidities were cardiovascular diseases, present in 60% of the patients (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

3.2. Clinical Outcomes one Month After Admission

Among the 150 patients presenting to the emergency department at HUIC, 61.3% required hospital admission, and 42% of those developed complications. The most common complications were infectious in nature (20%). The number of patients who died during hospitalization was 7 (4.7%) (

Table 3).

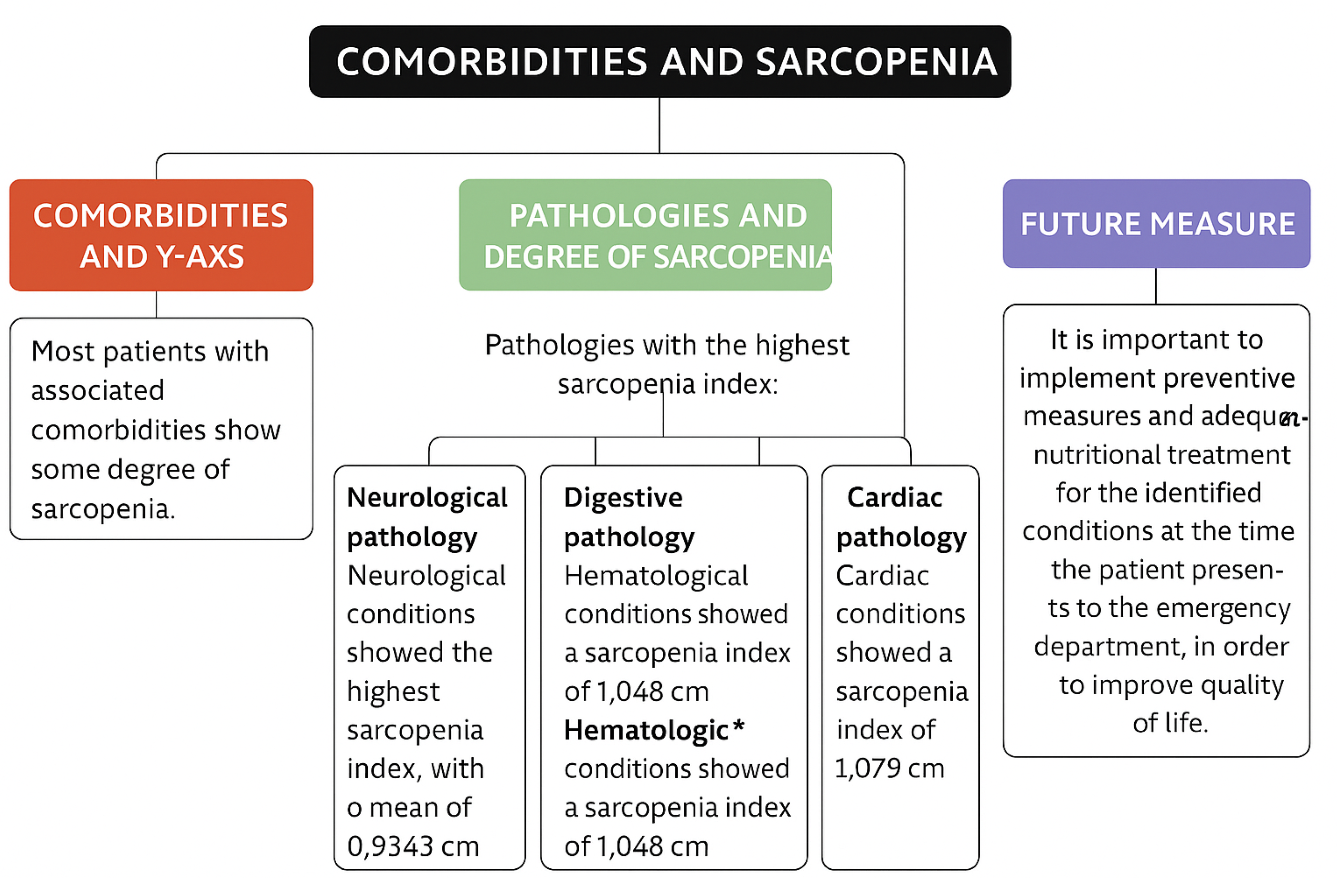

3.3. Relationship Between Sarcopenia and Comorbidities

The most significant sarcopenia values were observed in patients with neurological conditions, with a mean rectus femoris Y-axis measurement of 0.93 cm (

Table 5).

3.4. Relationship Between Sarcopenia and Complications

Among the patients included in the sample, 42% experienced complications during hospitalization. The sarcopenia index was notably lower in patients who developed complications compared to those who did not (1.0786 (SD 0.34) vs. 1.2414 (SD 0.38)) (

Table 6).

4. Discussion

This study describes the sarcopenia outcomes of patients who presented to the emergency department, as well as the prevalence of the condition according to different underlying diseases. Sarcopenia has often been reported as a comorbidity of cardiac conditions. A literature review identified sarcopenia as one of the most important factors contributing to impaired physical function and the progression of cardiovascular disease[

5]. In the present study, cardiovascular disease was the most frequent reason for emergency consultation (20.70%) and also the most common comorbidity, with 91 out of 150 patients having a history of cardiovascular disease.

Stroke ranked as the second leading cause of death in Spain during the first half of 2023, following ischemic heart disease[

18]. Sarcopenia has been linked to such conditions due to its role in capillary alterations in skeletal muscle tissue and its association with neuronal degeneration[

19]. In ischemic stroke, cerebral injury leads to synaptic remodeling, including alterations in motor neuron innervation, which increases the likelihood of developing sarcopenia. Among the 150 participants, neurological pathology showed the highest degree of sarcopenia, with a mean Y-axis measurement of 0.93 cm in the rectus femoris. However, this group was relatively small, as only 23 out of 150 patients presented with neurological symptoms. Most were ischemic stroke survivors with one or more cardiovascular risk factors, though other clinical conditions such as epilepsy were also represented.

A descriptive observational study of 303 patients with digestive diseases showed that 32.00% had a diagnosis of sarcopenia. Sarcopenia prevalence was reported as 22.20% in gastrointestinal disease, 36.60% in biliary-pancreatic disease, and 36.90% in hepatic disease[

14]. A literature review further concluded that early-onset Crohn’s disease and advanced-age ulcerative colitis were associated with a higher risk of sarcopenia due to the malabsorption and inflammation characteristic of these conditions[

20]. The present study supports this evidence, showing that patients with digestive diseases had the second highest prevalence of sarcopenia, with a mean Y-axis measurement of 1.05 cm.

Regarding hematological conditions, a direct relationship was also observed with sarcopenia. A cross-sectional study indicated that low hematocrit, decreased hemoglobin levels—as in anemia—and increased IL-6 were associated with a greater likelihood of sarcopenia[

21]. Similarly, our findings placed hematological conditions as the third leading group in terms of sarcopenia prevalence, with a mean of 1.05 cm.

Finally, patients with respiratory conditions in this study exhibited the lowest degrees of sarcopenia, as there were no substantial numerical differences in Y-axis means between patients with or without a respiratory history. However, certain respiratory conditions, such as pneumonia, are associated with inflammation that promotes muscle atrophy via a pro-inflammatory cytokine cascade[

19]. It is noteworthy that the majority of complications observed after hospital admission in this study were infectious respiratory events, often requiring extended hospital stays and contributing to physical decline and muscle mass loss.

Despite the variation in the frequency of diagnoses and Y-axis measurements, most patients with any of the comorbidities listed above showed some degree of sarcopenia, with Y-axis means generally around 1.0–1.1 cm. The results of this study demonstrate that neurological pathology was associated with the lowest muscle thickness and highest sarcopenia index, with a mean of 0.93 cm, followed by digestive, hematological, and cardiac conditions with means of 1.05 cm, 1.05 cm, and 1.08 cm, respectively. (

Figure 2).

5. Conclusions

Sarcopenia is highly prevalent among patients presenting to the emergency department, regardless of the primary reason for consultation, particularly in those with chronic comorbidities.

Neurological conditions showed the highest association with severe sarcopenia, followed by digestive, hematological, and cardiovascular diseases, based on rectus femoris muscle ultrasound measurements.

Muscle ultrasound is a feasible, non-invasive screening tool in the emergency setting, offering objective evaluation of muscle mass that may help stratify clinical risk.

A higher degree of sarcopenia was associated with an increased risk of in-hospital complications, supporting its role as an early marker of frailty and clinical deterioration.

The assessment of sarcopenia should be integrated into emergency care protocols, especially for older adults and patients with neurological, digestive, or hematological conditions.

Further research is warranted to develop targeted nutritional and physical interventions that can improve clinical outcomes beginning from the emergency department phase.

6. Study Limitations

This study was conducted at a single hospital center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations or clinical settings.

The cross-sectional observational design does not allow for the establishment of causal relationships between sarcopenia and clinical outcomes.

Although the sample size was adequately estimated, it may not have been large enough to detect subtle differences between certain clinical subgroups.

Data on baseline functional status, physical activity levels, and nutritional intake were not collected, despite being relevant factors in the development of sarcopenia.

7. Future Research Directions

Expand the study to multiple centers with varying healthcare characteristics and patient populations to validate and compare findings.

Design longitudinal studies to evaluate the progression of sarcopenia and its impact on medium- and long-term clinical outcomes.

Assess the effectiveness of early nutritional and physical interventions initiated in the emergency department to prevent functional decline.

Include additional variables such as functional assessment, nutritional status, systemic inflammation, and quality of life measures.

Investigate the use of muscle ultrasound as a dynamic marker for therapeutic response monitoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.G. and N.M.; methodology, N.M.; software, N.M.; validation, V.S., F.G. and N.M.; formal analysis, N.M.; investigation, V.S.; resources, F.G.; data curation, N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, F.G.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, F.R.; supervision, F.R.; project administration, N.M.; funding acquisition, F.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded through the funds of the IDIPHISA Foundation (Research Institute of the Puerta de Hierro University Hospital), with which the Infanta Cristina University Hospital in Madrid was affiliated, grant number

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Puerta de Hierro University Hospital (ACT 245.23).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the staff of the Emergency Department of the Infanta Cristina University Hospital for their collaboration and patience during the data collection process. Special thanks to the nursing team and nursing assistants for their continued support and involvement throughout the ultrasound assessments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASIS |

anterior superior iliac spine |

| BIA |

Bioelectrical impedance analysis |

| COPD |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CRP |

C-reactive protein |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| DEXA |

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry |

| EWGSOP2 |

European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People |

| GLP-1ra |

glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist |

| DPP-IVi |

dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors |

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| SGLT-2i |

sodium-glucose co-transporter inhibitors |

| T2DM |

Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

References

- Montero-Errasquín, B.; Cruz-Jentoft, A. Sarcopenia. Medicine - Programa de Formación Médica Continuada Acreditado 2022, 13, 3643–3648. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Tocino, M.L.; Cigarrán, S.; Ureña, P.; González Casaus, M.L.; Mas-Fontao, S.; Gracia Iguacel, C.; Ortíz, A.; Gonzalez Parra, E. Definición y evolución del concepto de sarcopenia. Nefrología 2024, 44, 323–330. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age and Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; Morley, J.E.; Von Haehling, S. Welcome to the ICD-10 code for sarcopenia. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle 2016, 7, 512–514. [CrossRef]

- He, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Ye, H. Relationship Between Sarcopenia and Cardiovascular Diseases in the Elderly: An Overview. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2021, 8, 743710. [CrossRef]

- Morley, J.E. Frailty and sarcopenia in elderly. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift 2016, 128, 439–445. [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Zhao, R.; Wan, Q.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Shen, X.; Wu, X. Sarcopenia and adverse health-related outcomes: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. Cancer Medicine 2020, 9, 7964–7978. [CrossRef]

- Carbone, S.; Lavie, C.J.; Arena, R. Obesity and Heart Failure: Focus on the Obesity Paradox. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2017, 92, 266–279. [CrossRef]

- Batsis, J.A.; Villareal, D.T. Sarcopenic obesity in older adults: aetiology, epidemiology and treatment strategies. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2018, 14, 513–537. [CrossRef]

- Damluji, A.A.; Alfaraidhy, M.; AlHajri, N.; Rohant, N.N.; Kumar, M.; Al Malouf, C.; Bahrainy, S.; Ji Kwak, M.; Batchelor, W.B.; Forman, D.E.; et al. Sarcopenia and Cardiovascular Diseases. Circulation 2023, 147, 1534–1553. [CrossRef]

- Tagliafico, A.S.; Bignotti, B.; Torri, L.; Rossi, F. Sarcopenia: how to measure, when and why. La radiologia medica 2022, 127, 228–237. [CrossRef]

- Curcio, F.; Testa, G.; Liguori, I.; Papillo, M.; Flocco, V.; Panicara, V.; Galizia, G.; Della-Morte, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Cacciatore, F.; et al. Sarcopenia and Heart Failure. Nutrients 2020, 12, 211. [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Yan, L.; Tong, R.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, J.; Wang, Q.; Hou, G.; et al. Ultrasound Assessment of the Rectus Femoris in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Predicts Sarcopenia. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2022, Volume 17, 2801–2810. [CrossRef]

- Onishi, S.; Shiraki, M.; Nishimura, K.; Hanai, T.; Moriwaki, H.; Shimizu, M. Prevalence of Sarcopenia and Its Relationship with Nutritional State and Quality of Life in Patients with Digestive Diseases. Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology 2018, 64, 445–453. [CrossRef]

- Colloca, G.; Di Capua, B.; Bellieni, A.; Cesari, M.; Marzetti, E.; Valentini, V.; Calvani, R. Muscoloskeletal aging, sarcopenia and cancer. Journal of Geriatric Oncology 2019, 10, 504–509. [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, M.; Becerra, R.; Galvis, J.C. Sarcopenia versus Caquexia. Revista Repertorio de Medicina y Cirugía 2015, 24, 7–15. [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Cánovas, J.; López-Sampalo, A.; Cobos-Palacios, L.; Ricci, M.; Hernández-Negrín, H.; Mancebo-Sevilla, J.J.; Álvarez Recio, E.; López-Carmona, M.D.; Pérez-Belmonte, L.M.; Gómez-Huelgas, R.; et al. Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Elderly Patients with Frailty and/or Sarcopenia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 8677. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. INEbase: Operaciones estadísticas, 2025. Accessed: 2025-05-11.

- Imamura, M.; Nozoe, M.; Kubo, H.; Shimada, S. Association between premorbid sarcopenia and neurological deterioration in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 2023, 224, 107527. [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; Nakamura, S.; Miyazaki, T.; Kakimoto, K.; Fukunishi, S.; Asai, A.; Nishiguchi, S.; Higuchi, K. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Sarcopenia: Its Mechanism and Clinical Importance. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2021, 10, 4214. [CrossRef]

- Pillatt, A.P.; Franz, L.B.B.; Berlezi, E.M.; Schneider, R.H. Relationship between hematological, endocrine and immunological markers and sarcopenia in the elderly. Acta Fisiátrica 2022, 29, 67–74. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).