1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence, digital avatars have shown great potential in various application scenarios such as intelligent assistants, customer service, virtual reality, and film production. To meet the requirements of specific tasks, constructing highly realistic and personalized digital human faces has become a growing research focus.

Among these technologies, speech-driven talking head synthesis has emerged as a core component, aiming to generate synchronized lip movements and facial expressions based on speech input, thereby enabling natural and lifelike dynamic face generation. This technology plays a particularly important role in fields such as digital assistants [

1], virtual reality [

2], and visual effects in film production [

3], where higher demands are placed on visual realism and spatiotemporal coherence.

Although deep generative models have achieved significant progress in recent years [

1,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], existing methods still fall short of satisfying the increasing demand for high-quality and highly interactive digital avatars. Traditional approaches based on Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) [

10,

11,

12,

13] perform well in modeling lip movements, but often suffer from identity inconsistency, leading to visual artifacts such as unstable tooth size and fluctuating lip thickness during synthesis. Recently, NeRF-based methods have gained attention due to their ability to preserve facial details and maintain identity consistency. However, NeRF still faces several challenges in speech-driven talking head synthesis tasks, such as lip-sync mismatches, difficulty in controlling facial expressions, and unstable head poses-all of which negatively affect the naturalness and immersive quality of the generated videos.

Although many recent speech-driven talking head synthesis methods have made significant strides in improving synthesis quality and inference speed, several key challenges remain unresolved. For example, SyncTalk [

14], ER-NeRF [

15], and RAD-NeRF [

16] incorporate Instant-NGP [

17] technology to accelerate the generation of dynamic 3D avatars and enhance real-time performance. However, these methods still suffer from limitations in modeling precision and rendering fidelity. First, audio inputs are often affected by background noise, resulting in inaccurate feature extraction and subsequently degrading lip-sync accuracy and the naturalness of facial movements. Second, it remains challenging to fully model high-level correlations between audio and visual modalities during feature alignment, which is crucial for producing detailed and realistic dynamic expressions.

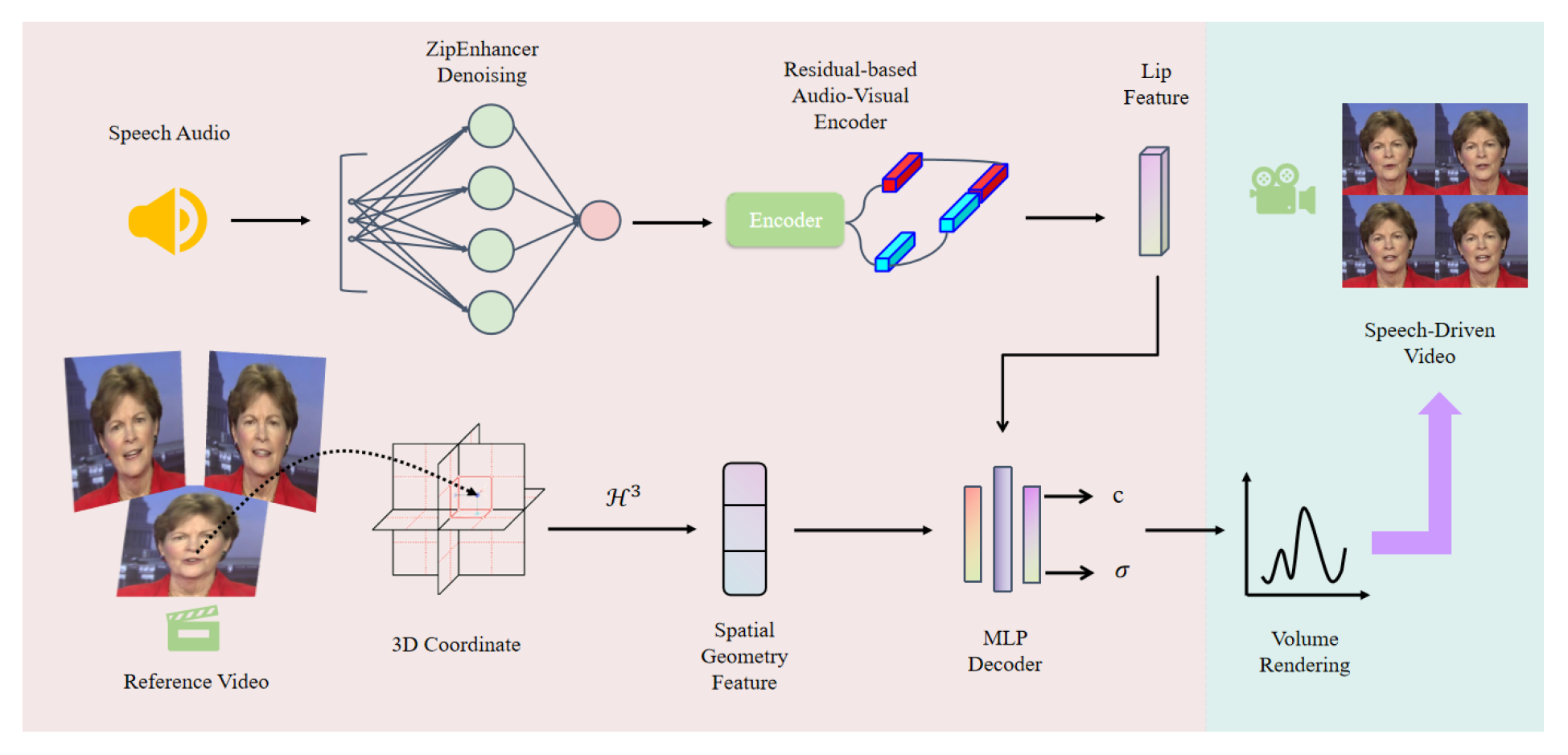

To address the aforementioned challenges, in this paper, we propose an enhanced speech-driven facial synthesis framework that focuses on improving audio-visual alignment accuracy and facial detail fidelity. Unlike previous approaches that directly feed raw audio into the encoder, our framework introduces a speech denoising module prior to the audio-visual encoding process. This effectively suppresses background noise interference, improving the clarity and stability of the audio signal at the source. By enhancing the expressiveness of speech features, our method allows for more accurate control of lip movements and facial dynamics, thereby significantly improving the naturalness of the synthesized avatars.

In addition, we design a Residual-based Audio-Visual Encoder to deeply extract and fuse the spatiotemporal correlations between audio and visual modalities. By incorporating residual connections, the encoder strengthens feature learning capacity and alleviates the gradient vanishing problem in high-dimensional spaces. This design improves the model’s accuracy in capturing complex facial dynamics and enhances the stability and consistency of audio-visual alignment. Notably, it delivers more natural motion restoration in detailed regions such as lips, cheeks, and jaw.

Experimental results demonstrate that our proposed method significantly outperforms existing models on several benchmark datasets, achieving noticeable improvements in lip-sync precision, facial expression naturalness, and overall visual fidelity. These advancements provide a solid foundation for building high-quality, photorealistic digital avatars and offer new insights for practical applications of speech-driven virtual humans.

In summary, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

Speech Denoising Module: We introduce a noise suppression component before the audio encoding stage to purify the input signal, reducing the impact of background noise and enhancing the usability of audio features.

Residual-based Audio-Visual Encoder: We propose a novel encoder architecture that leverages residual connections to improve cross-modal feature fusion and alignment, thereby enhancing modeling accuracy and visual output quality.

Extensive Experimental Validation: We conduct comprehensive quantitative and qualitative experiments across multiple datasets to evaluate the proposed method in terms of lip-sync accuracy, facial detail restoration, and visual realism. The results consistently demonstrate superior synthesis quality and robustness compared to existing approaches.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section II summarize related research achievement in the field of audio-driven talking head synthesis. Then in Section III, we present the details of our design, including the architecture and the neural networks. Subsequently, we provide experimental results to validate our design. Finally, Section V concludes the paper.

2. Related Works

Researchers have made substantial efforts to improve the performance of audio-driven talking head synthesis, introducing various denoising techniques to enhance signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and improve signal quality. The main achievements in this field are summarized as follows.

2.1. Audio-Driven Talking Head Synthesis

In recent years, audio-driven talking head synthesis based on GANs has attracted significant attention [

4,

7,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. While these methods have achieved notable progress in generating coherent video sequences, they still face challenges in maintaining identity consistency of the synthesized subjects. A typical class of approaches focuses on synthesizing the lip region [

5,

10,

11,

12,

13,

25], modeling lip movements to produce synchronized lip animations and enhance the expressiveness of talking heads. For instance, Wav2Lip [

5] introduces a lip-sync expert module to improve the accuracy of lip movements. However, due to its reliance on multiple reference frames for reconstruction, it demonstrates limited capability in preserving identity consistency.

In contrast, works such as [

4,

6,

8,

26] attempt full-face synthesis. While these methods improve the overall facial dynamics, they often struggle to maintain synchronization between facial expressions and head poses. To address the limitations of GAN-based methods in terms of generation speed and spatial consistency, recent studies have turned toward NeRF-based approaches.

With the rapid development of NeRF techniques [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32], their ability to efficiently model 3D structures has shown promising potential in talking head synthesis. However, traditional NeRF renderers are computationally intensive, slow to render, and require large memory, making them unsuitable for real-time applications.

To mitigate these issues, SSP-NeRF [

33] introduces a semantically guided sampling mechanism that effectively captures the varying impact of audio signals on different facial regions, thereby enhancing the modeling of local facial dynamics. RAD-NeRF [

16], built upon the Instant-NGP framework [

17], further improves rendering efficiency and visual quality. Nevertheless, it still relies on a complex audio processing pipeline, which increases the training burden and computational cost. Moreover, some multi-stage strategies [

34,

35] pretrain audio-visual alignment modules and utilize NeRF-based renderers to generate higher-quality images.

While these methods enhance expression fidelity, the additional training stages often introduce synchronization errors, limiting their effectiveness in tasks that demand high temporal and spatial consistency.

2.2. Speech Denoising Techniques

Speech Enhancement (SE) aims to improve the quality of speech signals degraded by complex acoustic environments, making device-captured audio clearer and more intelligible. By suppressing background noise and highlighting relevant speech components, SE provides more reliable audio inputs for downstream tasks such as speech communication and automatic speech recognition (ASR), thereby enhancing overall performance and human-computer interaction experiences.

Current mainstream SE methods can be broadly categorized into two types: time-domain models and time-frequency (TF) domain models. Time-domain approaches directly model the signal at the waveform level by encoding noisy waveforms into latent representations, which are then processed using architectures such as Transformers and reconstructed into clean speech [

36,

37]. In contrast, TF-domain methods first extract Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) features from the noisy signal, use deep neural networks to predict the frequency domain representation of clean speech, and finally apply the inverse STFT (ISTFT) to reconstruct the waveform [

38,

39].

To address the quality degradation under low SNR conditions, recent studies have incorporated complex-valued modeling in the TF domain and employed both explicit and implicit strategies for optimizing magnitude and phase estimation of STFT [

40], achieving significant improvements in speech restoration. Unlike ASR models that predominantly focus on temporal modeling (e.g., processing hidden features

) [

41], SE and Speech Separation (SS) [

42,

43] tasks typically retain both temporal and frequency dimensions. In processing feature tensors

, they often employ dual-path architectures to model along both

T and

F axes in parallel.

Although SE and SS models usually have fewer parameters (typically in the range of millions) compared to ASR models [

44], their dual-path mechanisms introduce notable computational costs. In recent years, the development of efficient ASR encoders such as Efficient Conformer [

45], Squeezeformer [

46], and Zipformer [

47] has significantly reduced the computational burden by introducing hierarchical downsampling mechanisms. For example, Squeezeformer applies a U-Net structure to downsample the temporal dimension of intermediate representations to 12.5 Hz, while Zipformer further introduces multi-level, non-uniform downsampling strategies to improve efficiency. Inspired by these advances, ZipEnhancer [

48] extends temporal downsampling techniques to SE models and combines them with frequency-domain downsampling, achieving a favorable trade-off between speech quality and computational efficiency. This development paves the way for lightweight and high-performance SE solutions.

3. RAE-NeRF Architecture Design

In this section, we present the proposed RAE-NeRF framework in detail, with an overview of the architecture illustrated in

Figure 1. First, we describe the core component of the ZipEnhancer model [

48] used in the speech denoising module-namely, the DualPath Zipformer Blocks. Then, we elaborate on the structure of our Residual-based Audio-Visual Encoder. Finally, we introduce the tri-plane hash representation employed to model spatial geometric information.

3.1. DualPathZipformer Blocks

3.1.1. Down-UPSampleStacks

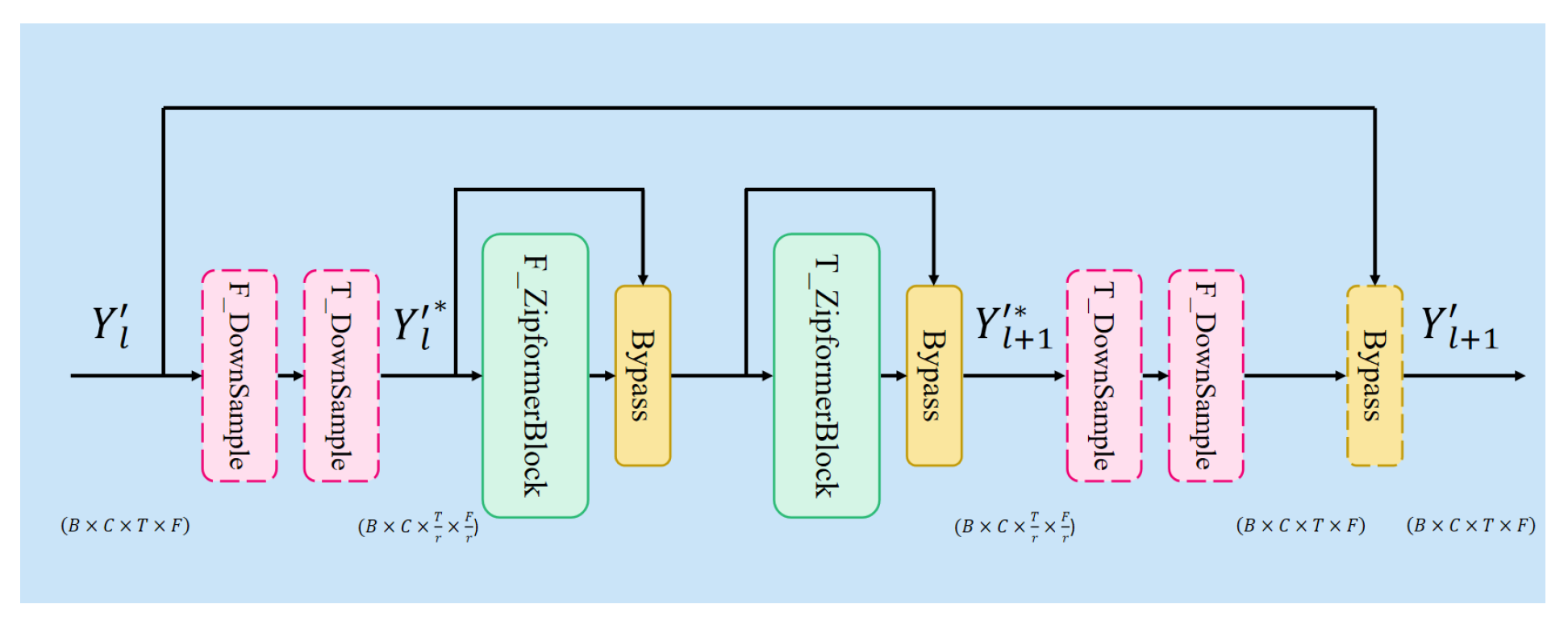

Unlike the single-path downsampling modules commonly used in automatic speech recognition (ASR), we adopt a dual-path structure for time-frequency domain modeling, which simultaneously performs upsampling and downsampling in both the time and frequency dimensions. As shown in

Figure 2, the Down-UPSampleStack consists of paired DownSample and UpSample modules to achieve symmetric compression and expansion along either the temporal or frequency axes.

Specifically, we denote the down-up modules in the temporal dimension as T_DownSample and T_UpSample, and their counterparts in the frequency dimension as F_DownSample and F_UpSample. The sampling factor is represented by r. Our sampling strategy follows the simple method used in Zipformer: the DownSample module applies r learnable scalar weights (normalized by softmax) to aggregate every r frames, whereas the UpSample module repeats each frame r times. Through this process, the original input feature map , where C is the number of channels, T is the temporal length, and F is the frequency dimension-is downsampled into at layer l. The downsampled features are then passed to a DualPath ZipformerBlock for efficient modeling in both time and frequency domains at a reduced frame rate.

In addition, a Bypass module, analogous to residual connections, is included to preserve unsampled information and enhance the model’s representational capacity. It is worth noting that the dashed DownSample components shown in

Figure 2 are optional and are omitted when

.

3.1.2. ZipformerBlock

In the Dual-Path structure, both the F_ZipformerBlock and T_ZipformerBlock share the same model architecture. For the compressed feature within a mini-batch, shaped as , where B is the batch size, the data is first reshaped to and fed into the F_ZipformerBlock to capture frequency-domain dependencies. Then, it is reshaped to and passed through the T_ZipformerBlock to model temporal correlations. The final output is the updated feature representation .

3.1.3. Bypass

The Bypass module introduces a learnable residual connection that flexibly integrates the input

x and the output

y of a wrapped intermediate module. The output is defined as:

where

w denotes a learnable channel-wise weight, and ⊙ indicates element-wise multiplication along the channel dimension. A smaller value of

w indicates a higher tendency to bypass the intermediate module, thereby preserving more of the original input signal.

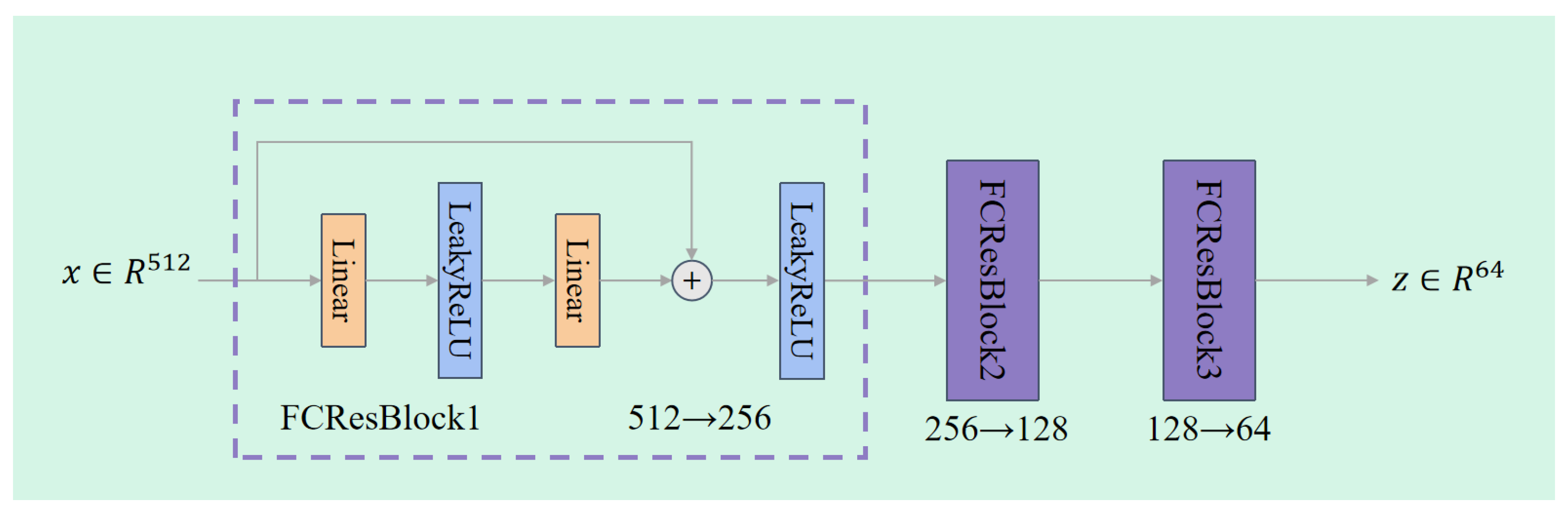

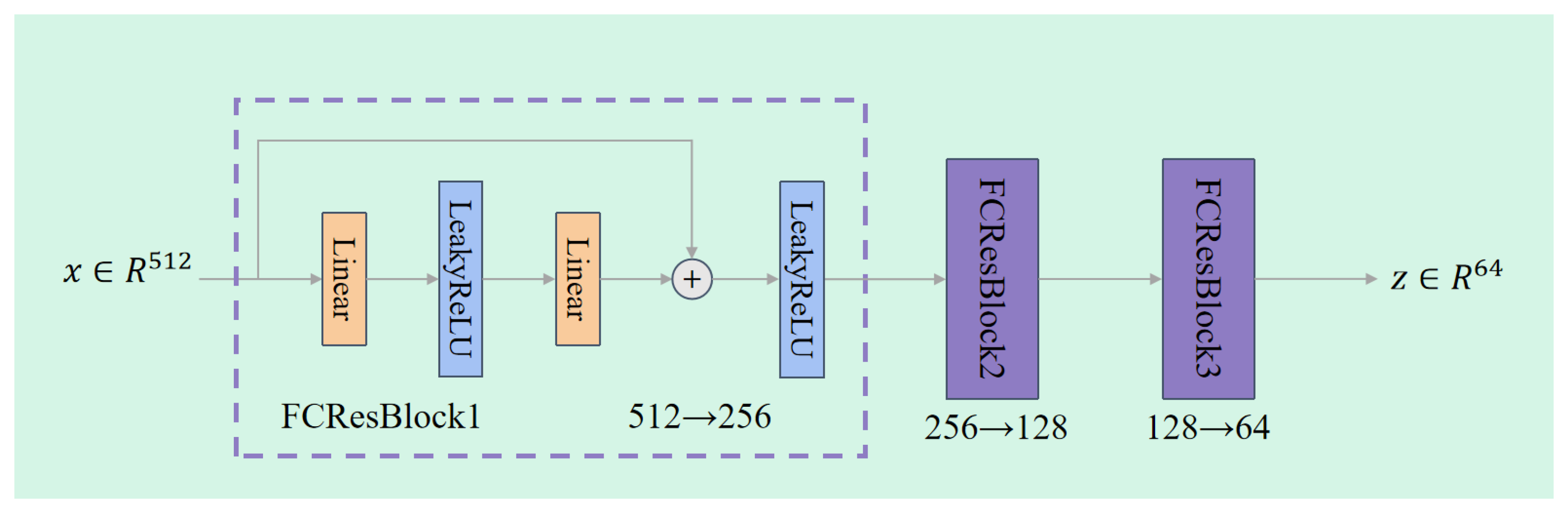

3.2. Residual-Based Audio-Visual Encoder

To effectively extract deep semantic information from input audio features, we design a residual-connected audio encoder module, termed the Residual-based Audio-visual Encoder. This module consists of multiple Fully Connected Residual Blocks (FCResBlocks), which help maintain the network’s expressive capacity while improving training stability.

3.2.1. Network Architecture

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the input to the Residual-based Audio-Visual Encoder is a 512-dimensional audio feature vector. After passing through three FCResBlocks, it is mapped to a low-dimensional audio representation of size

(set to 64 in our implementation). The transformation process is listed as follows:

First FCResBlock: Input dimension = 512, Output dimension = 256;

Second FCResBlock: Input dimension = 256, Output dimension = 128;

Third FCResBlock: Input dimension = 128, Output dimension = .

Each FCResBlock contains two fully connected (Linear) layers, with a LeakyReLU activation in between. A residual connection is employed to preserve low-level information from the input. The detailed formulation is provided in Equation

4.

3.2.2. Definition of FCResBlock

Given an input feature

, the output

of an FCResBlock is defined as:

Here, , , and are learnable weight matrices, and , , and are their corresponding biases. This structure ensures that essential information from the input is retained during the transformation process, helping to mitigate the vanishing gradient problem.

Figure 3.

The overall architecture of Residual-based Audio-visual Encoder.

Figure 3.

The overall architecture of Residual-based Audio-visual Encoder.

3.2.3. Down-UPSampleStacks

Unlike the single-path downsampling modules commonly used in automatic speech recognition (ASR), we adopt a dual-path structure for time-frequency domain modeling, which simultaneously performs upsampling and downsampling in both the time and frequency dimensions. As shown in

Figure 2, the Down-UPSampleStack consists of paired DownSample and UpSample modules to achieve symmetric compression and expansion along either the temporal or frequency axes.

Specifically, we denote the down-up modules in the temporal dimension as T_DownSample and T_UpSample, and their counterparts in the frequency dimension as F_DownSample and F_UpSample. The sampling factor is represented by r. Our sampling strategy follows the simple method used in Zipformer: the DownSample module applies r learnable scalar weights (normalized by softmax) to aggregate every r frames, whereas the UpSample module repeats each frame r times. Through this process, the original input feature map , where C is the number of channels, T is the temporal length, and F is the frequency dimension-is downsampled into at layer l. The downsampled features are then passed to a DualPath ZipformerBlock for efficient modeling in both time and frequency domains at a reduced frame rate.

In addition, a Bypass module, analogous to residual connections, is included to preserve unsampled information and enhance the model’s representational capacity. It is worth noting that the dashed DownSample components shown in

Figure 2 are optional and are omitted when

.

3.2.4. ZipformerBlock

In the Dual-Path structure, both the F_ZipformerBlock and T_ZipformerBlock share the same model architecture. For the compressed feature within a mini-batch, shaped as , where B is the batch size, the data is first reshaped to and fed into the F_ZipformerBlock to capture frequency-domain dependencies. Then, it is reshaped to and passed through the T_ZipformerBlock to model temporal correlations. The final output is the updated feature representation .

3.2.5. Bypass

The Bypass module introduces a learnable residual connection that flexibly integrates the input

x and the output

y of a wrapped intermediate module. The output is defined as:

where

w denotes a learnable channel-wise weight, and ⊙ indicates element-wise multiplication along the channel dimension. A smaller value of

w indicates a higher tendency to bypass the intermediate module, thereby preserving more of the original input signal.

3.3. Residual-Based Audio-Visual Encoder

To effectively extract deep semantic information from input audio features, we design a residual-connected audio encoder module, termed the Residual-based Audio-visual Encoder. This module consists of multiple Fully Connected Residual Blocks (FCResBlocks), which help maintain the network’s expressive capacity while improving training stability.

3.3.1. Network Architecture

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the input to the Residual-based Audio-Visual Encoder is a 512-dimensional audio feature vector. After passing through three FCResBlocks, it is mapped to a low-dimensional audio representation of size

(set to 64 in our implementation). The transformation process is as follows:

First FCResBlock: Input dimension = 512, Output dimension = 256;

Second FCResBlock: Input dimension = 256, Output dimension = 128;

Third FCResBlock: Input dimension = 128, Output dimension = .

Each FCResBlock contains two fully connected (Linear) layers, with a LeakyReLU activation in between. A residual connection is employed to preserve low-level information from the input. The detailed formulation is provided in Equation

4.

3.3.2. Definition of FCResBlock

Given an input feature

, the output

of an FCResBlock is defined as:

Here, , , and are learnable weight matrices, and , , and are their corresponding biases. This structure ensures that essential information from the input is retained during the transformation process, helping mitigate the vanishing gradient problem.

Figure 4.

The overall architecture of Residual-based Audio-visual Encoder.

Figure 4.

The overall architecture of Residual-based Audio-visual Encoder.

3.3.3. Overall Module Workflow

The complete structure of the Residual-based Audio-Visual Encoder is shown in

Figure 4. Suppose the input is a 3D tensor

, where

B is the batch size and

T is the time window size (defaulting to 16). The model encodes each frame independently along the temporal dimension, resulting in an audio representation

, which is used for subsequent cross-modal alignment or task-specific modeling.

3.4. Tri-Plane Hash Representation

To represent a static 3D scene, NeRF [

27] leverages multi-view images and their corresponding camera poses to construct an implicit function

for scene modeling. The function is defined as

, where

denotes a point in 3D space and

indicates the viewing direction. The output consists of

, representing the radiance color at that location in the given direction, and

, representing the volumetric density at that location.

The color value

of each pixel in the final rendered image is obtained by integrating the volumetric information sampled along a ray

originating from the camera position

o in the direction

d. The integration is computed as follows:

Here,

and

represent the near and far bounds of sampling along the ray, respectively.

is the accumulated transmittance, which measures the probability that the ray is not occluded from the origin up to time

t. It is defined as:

To alleviate hash collisions and enhance feature representation capabilities, we introduce three orthogonal 2D hash grids [

15]. Specifically, a 3D spatial coordinate

is encoded using three multi-resolution 2D hash encoders from different projection directions, following the design in [

17]. Each encoder projects the 3D point onto a 2D plane and maps the projected coordinates

to a feature vector, as defined by:

Here, the output feature

encodes geometric information on the projection plane

, where

L denotes the number of resolution levels and

D is the feature dimensionality at each resolution level. We denote the multi-resolution hash encoder on plane

as

.

The final geometric feature vector

is obtained by concatenating the hash features from three orthogonal planes XY, YZ, and XZ:

where ⊕ denotes the concatenation operation.

The resulting feature

, together with the viewing direction

d, the lip feature

, and the expression feature

, is fed into an MLP decoder. The overall implicit function based on the tri-plane hash representation is defined as:

where

denotes the combination of the three hash encoders

,

, and

as specified in Equation

7.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Settings

The dataset used in our experiments consists of two parts: one comprises publicly available video sources, including datasets from [

33,

49,

50]; the other consists of internally recorded videos, covering speech content in English, Chinese, and Korean. On average, each video contains approximately 6160 frames. The internally recorded videos have a frame rate of 30 frames per second (FPS), while the publicly available datasets operate at 25 FPS. In terms of resolution, internal videos are

, videos from the AD-NeRF dataset [

49] are

, and other public videos are

. All videos feature centrally aligned human portraits.

For both qualitative and quantitative performance comparisons, we selected two NeRF-based methods as baselines: ER-NeRF [

15] and SyncTalk [

14], as well as a GAN-based method, Wav2Lip [

5].

The training of our model is divided into two stages. In the coarse stage, the portrait head model undergoes 100,000 training iterations. This is followed by a fine stage with an additional 25,000 iterations to further improve synthesis quality. We employ 2D hash encoders with a resolution level of

and a feature dimension

. In each iteration,

rays are sampled for optimization. We use the AdamW optimizer [

51], with a learning rate of 0.01 for the hash encoders and 0.001 for all other modules. All training processes are conducted on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU, with the total training time being approximately 2 hours.

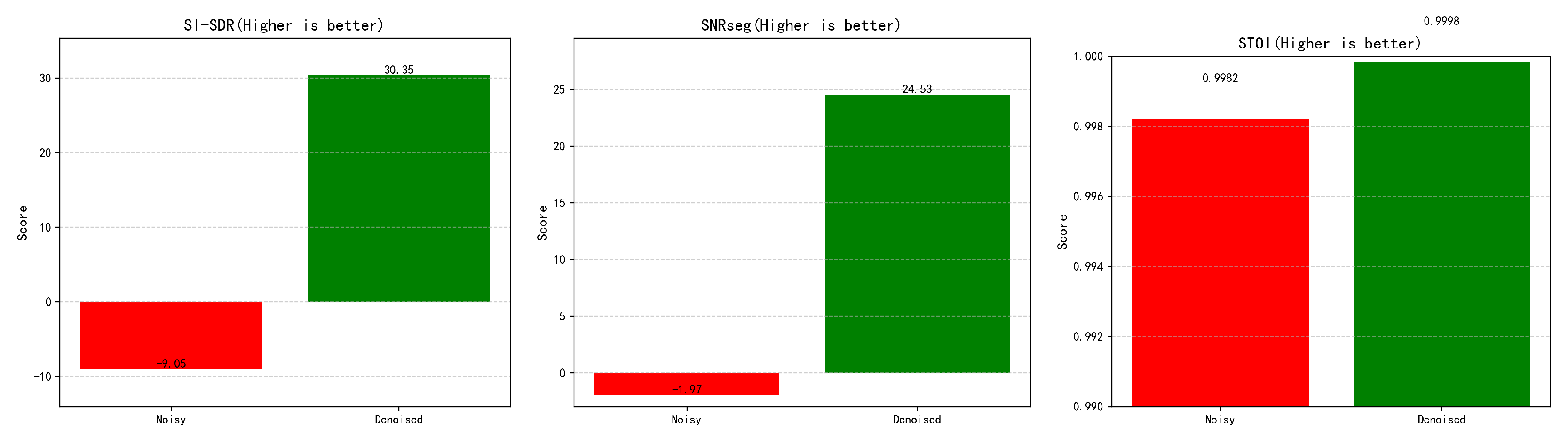

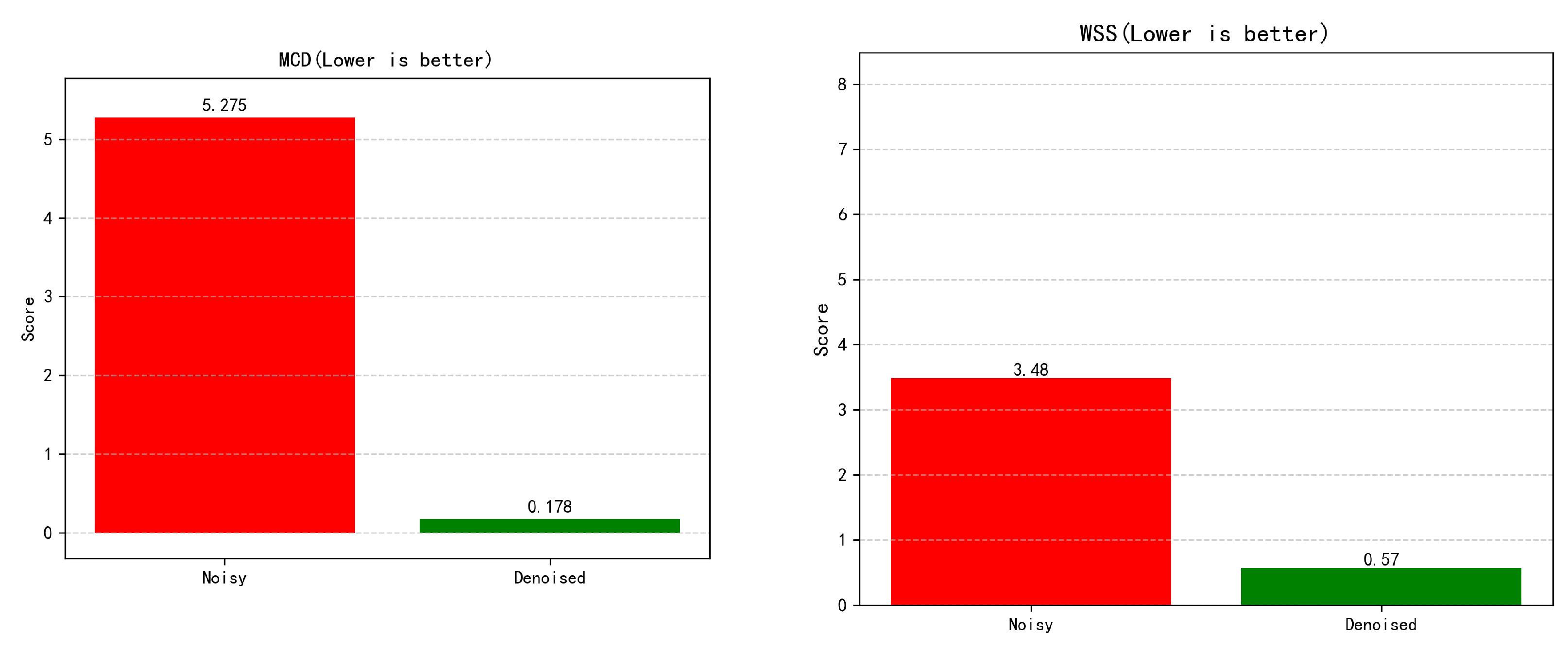

4.2. Denoising Performance Analysis

To evaluate the denoising effectiveness of the proposed ZipEnhancer network, we conducted a quantitative analysis using audio clips extracted from videos of six speakers in the publicly available dataset provided by [

34].

We employed five widely adopted objective evaluation metrics to assess speech quality and intelligibility: Segmental Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNRseg), Weighted Spectral Slope (WSS), Short-Time Objective Intelligibility (STOI), Scale-Invariant Signal-to-Distortion Ratio (SI-SDR) [

52], and Mel-Cepstral Distance (MCD) [

53].

As illustrated in the

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 , we conducted a comprehensive quantitative evaluation of the ZipEnhancer module using five objective metrics. For the SI-SDR metric, the denoised speech achieved a score of 30.35 dB, representing a substantial improvement over the noisy input’s score of -9.05 dB. This significant gain indicates that the denoised signal is much closer to the original clean speech in terms of spectral power distribution, with interference effectively suppressed.

In terms of SNRseg, the segmental signal-to-noise ratio increased from -1.97 dB for the noisy input to 24.53 dB after denoising, demonstrating that the energy of speech segments relative to noise was greatly enhanced. Regarding the STOI metric, the denoised speech achieved a score of 0.9998, compared to 0.9982 for the noisy signal, indicating improved short-time intelligibility. This suggests that the denoised speech is more comprehensible and thus more suitable for downstream applications such as speech recognition and communication.

For the MCD metric, the denoised speech yielded a score of 0.178, significantly lower than the 5.275 measured for the noisy input. This reflects a major reduction in spectral distortion and a notable enhancement in perceived audio quality. Lastly, the WSS score dropped from 3.48 (noisy input) to 0.57 (denoised), indicating that the spectral tilt of the denoised signal more closely resembles that of the clean reference, thereby improving the naturalness and realism of the speech.

Taken together, the results across all five evaluation metrics consistently demonstrate that the ZipEnhancer network exhibits strong denoising performance in both speech quality and intelligibility. These improvements provide a robust foundation for subsequent talking-head synthesis tasks.

4.3. Quantitative Evaluation

Full Reference Quality Assessment To comprehensively evaluate the quality of the generated images, we employ several full-reference image quality metrics, including Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) [

54], Multi-Scale Structural Similarity (MS-SSIM), and Frechet Inception Distance (FID) [

55]. These metrics measure different aspects of image clarity, structural fidelity, and perceptual similarity.

No Reference Quality Assessment Given that high PSNR images may still exhibit perceptual inconsistencies in texture details [

56], we further incorporate two no-reference quality assessment methods for more precise and perceptually aligned evaluations: the Natural Image Quality Evaluator (NIQE) [

57] and the Blind/Referenceless Image Spatial Quality Evaluator (BRISQUE) [

58]. These metrics help assess the perceptual realism of generated images without relying on reference ground truths.

Synchronization Assessment To evaluate facial motion accuracy and synchronization, we adopt the Landmark Distance (LMD) metric, which measures the spatial discrepancy between predicted and ground-truth facial landmarks. A lower LMD score indicates better temporal alignment and motion fidelity.

Evaluation Results The quantitative evaluation results for head reconstruction are summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2. We compare our method with existing GAN-based and NeRF-based approaches. It can be observed that our method achieves superior performance across all image quality metrics. Moreover, in terms of facial motion synchronization, our approach outperforms most competing methods, demonstrating its effectiveness in both visual quality and temporal consistency.

In the full reference quality evaluation (in

Table 1), RAE-NeRF achieves a PSNR value of 42.642164, which is slightly higher than that of SyncTalk (42.492073) and significantly surpasses those of Wav2Lip and ER-NeRF. This indicates that RAE-NeRF generates images with lower luminance error and higher clarity. Regarding structural similarity, the SSIM score of RAE-NeRF reaches 0.999274, which is close to SyncTalk’s 0.999254 and notably higher than those of the other two methods. This suggests that RAE-NeRF effectively preserves structural details and produces images highly consistent with the original. In terms of perceptual quality, RAE-NeRF achieves the lowest LPIPS score (0.003332), indicating that its outputs are perceptually closest to the ground truth and visually more realistic. Furthermore, the FID score of RAE-NeRF is 1.401045, also the lowest among the four methods, demonstrating that the distribution of its generated images closely matches that of real images.

In the no reference quality and synchronization evaluation (in

Table 2), RAE-NeRF shows superior performance as well. For lip motion synchronization, the LMD score of RAE-NeRF is 1.090, outperforming Wav2Lip (2.0289) and ER-NeRF (1.9174), and even better than SyncTalk (1.9961), indicating more accurate alignment between facial motion and speech. In terms of no-reference image quality metrics, RAE-NeRF achieves a BRISQUE score of 49.8398, lower than those of Wav2Lip and ER-NeRF, and comparable to SyncTalk (49.9054), reflecting a good balance of naturalness and perceptual quality. Its NIQE score is 7.3829, slightly lower than those of Wav2Lip (7.4609) and ER-NeRF (7.4267), and nearly identical to SyncTalk (7.3830), further confirming the superior perceptual quality of RAE-NeRF under no-reference conditions.

Taken together, the results from

Table 1 and

Table 2 demonstrate that our RAE-NeRF model consistently outperforms existing methods in both visual quality and dynamic accuracy. It not only ensures high image fidelity, structural consistency, and perceptual realism, but also achieves more precise synchronization of facial motion with speech, offering a robust and high-quality solution for head reconstruction tasks.

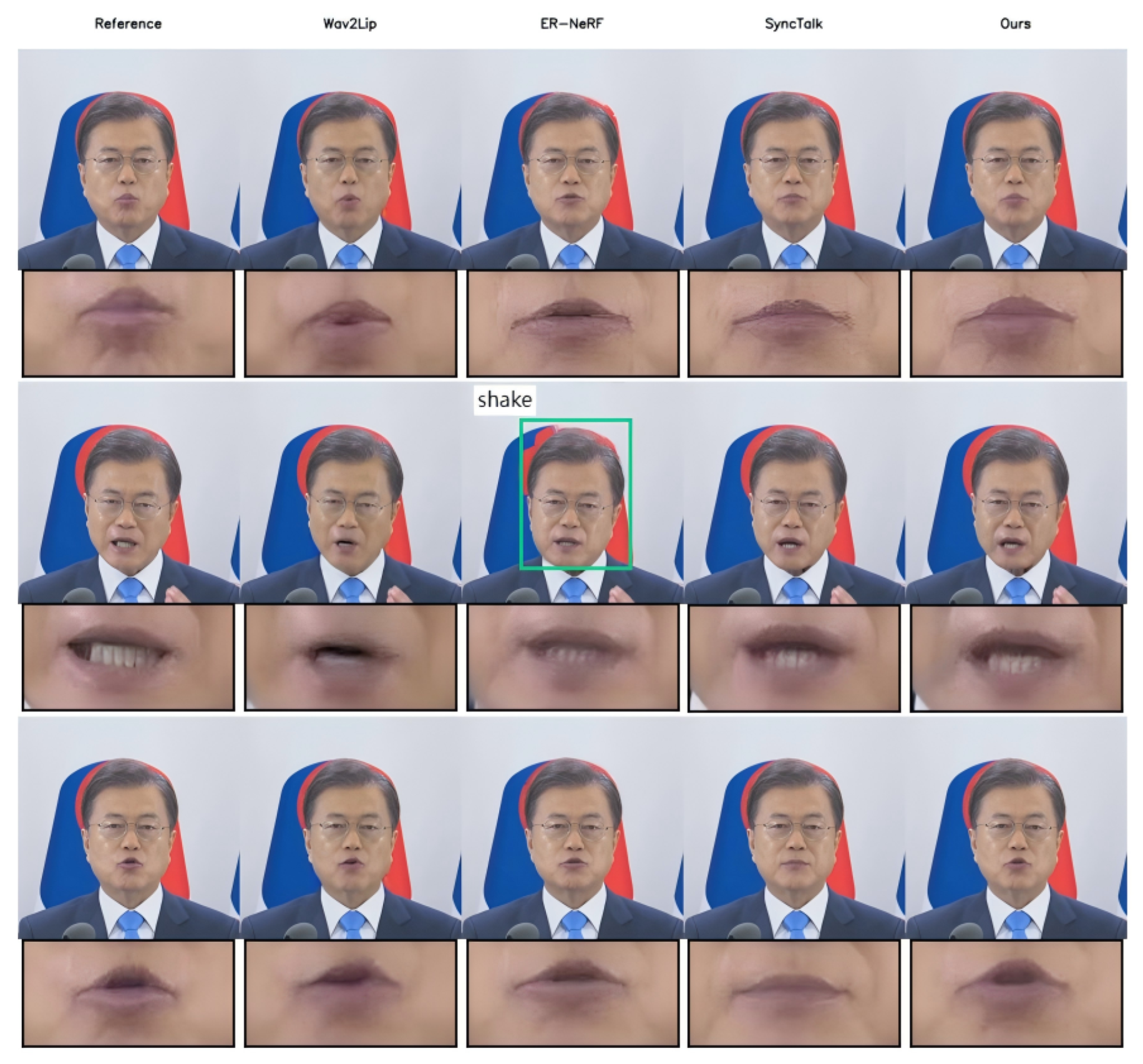

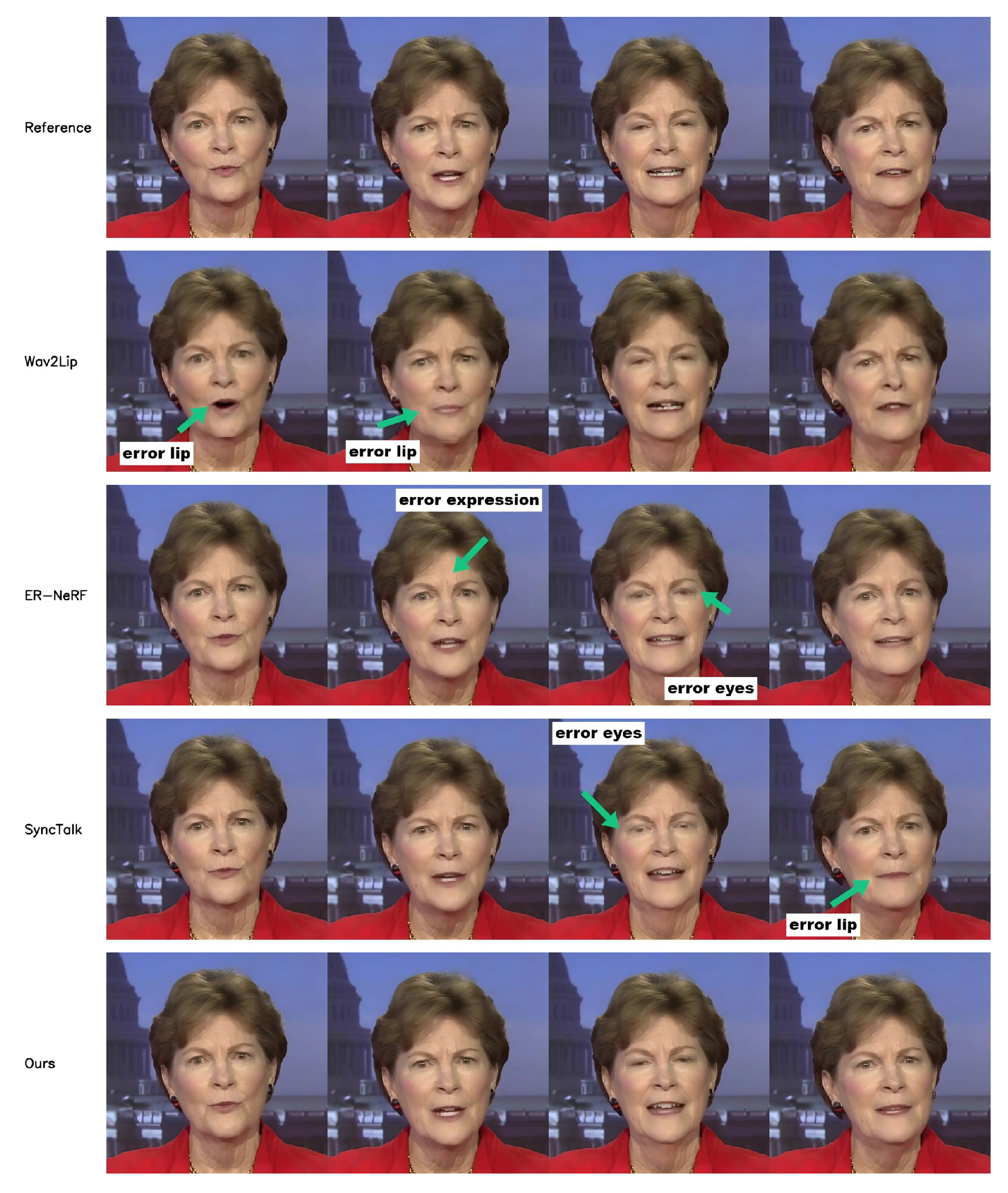

4.4. Qualitative Evaluation

Compared with existing methods such as Wav2Lip, ER-NeRF, and SyncTalk, the proposed RAE-NeRF demonstrates significant advantages across multiple dimensions, as illustrated in

Figure 7. Overall, the generated videos achieve superior alignment with reference frames, more accurate lip-sync, and more natural facial expressions. Specifically, the lip movements generated by our method closely mirror the dynamic articulation patterns of real human speech. The eye gaze and facial expressions are also highly consistent with those in the original video, resulting in a strong sense of realism and naturalness. In contrast, Wav2Lip exhibits noticeable lip-sync errors in certain frames; ER-NeRF occasionally generates mismatched expressions or gaze directions; and SyncTalk suffers from incorrect mouth shapes and blinking artifacts in some frames, negatively impacting synchronization and visual quality.

In terms of eye movement, our method accurately captures and reproduces natural eyeball motion and maintains a realistic blinking frequency, effectively avoiding the “dead-eye” effect. This enhances the liveliness and emotional expressiveness of the generated faces. In comparison, SyncTalk shows considerable discrepancies in the eye region across several frames, while ER-NeRF suffers from slight misalignment or uneven blinking, leading to a more artificial appearance. By precisely modeling the dynamics from reference videos, our method significantly improves realism and immersion in conversational scenarios.

Regarding facial detail preservation, our method produces clearer facial features and retains more comprehensive details, including skin textures, consistent lighting, and facial shadows, resulting in visual outputs highly similar to the reference video. Wav2Lip, on the other hand, generates blurry results in some frames, while ER-NeRF and SyncTalk show limitations in rendering fine-grained textures.

In terms of facial expression generation, our method enables precise control over gaze direction, eyebrow movement, and subtle facial variations synchronized with speech rhythm, further enhancing the realism of synthesized videos. By contrast, SyncTalk shows weaker coordination between eye and mouth movements in some frames, and ER-NeRF produces relatively static facial expressions, lacking dynamic variation.

Moreover, our method excels in head pose consistency and stability, naturally reproducing variations in head orientation, tilt, and movement as observed in the reference video. ER-NeRF exhibits visible jitter in some frames, while SyncTalk, though generally stable, occasionally generates slightly rigid facial details.

Figure 8.

Lip motion comparison results.

Figure 8.

Lip motion comparison results.

Finally, in terms of lip motion, our method achieves higher accuracy and naturalness in modeling lip opening, shape variation, and movement trajectory. The generated results align closely with the reference video frames, effectively reflecting the dynamic articulatory patterns of human speech, thereby enhancing the realism and immersive experience of the synthesized talking-head videos.

4.5. Audio-video Encoder

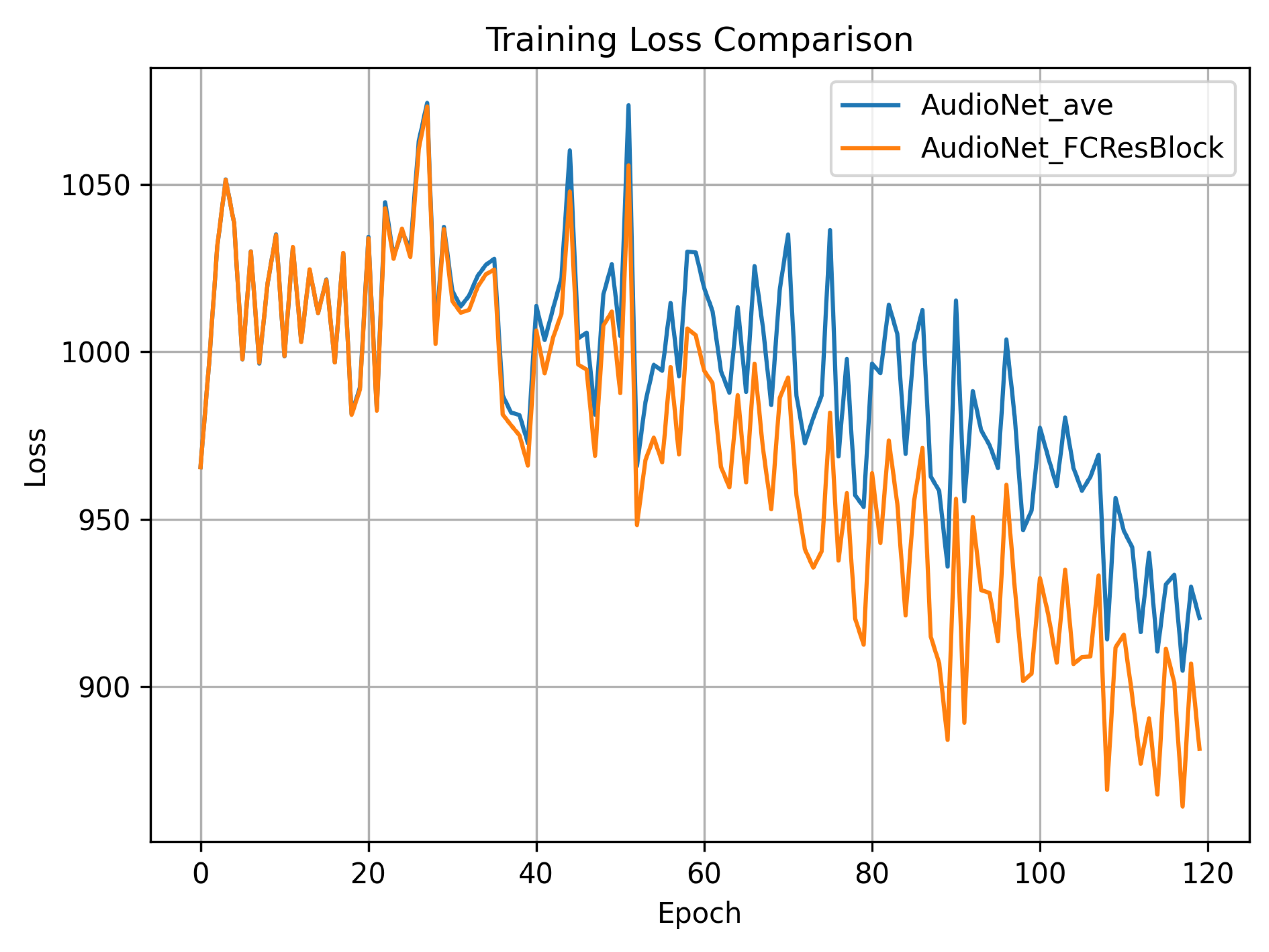

We extracted the Audio-video Encoder used in SyncTalk (AudioNet_ave) and our proposed Residual-based Audio-visual Encoder (AudioNet_FCResBlock), and trained them on simulated noisy audio data to compare their convergence behavior in terms of training loss. As shown in the

Figure 9, both models exhibit significant loss fluctuations during the initial training phase (approximately the first 40 epochs), but the overall trend indicates convergence. As training progresses, the loss of AudioNet_FCResBlock decreases more rapidly and becomes noticeably lower than that of AudioNet_ave after around 80 epochs, demonstrating its superior robustness and feature extraction capability. Furthermore, AudioNet_FCResBlock shows a more stable convergence trajectory throughout training, and achieves a significantly lower final loss value. These experimental results indicate that the proposed residual structure contributes to improved model fitting and generalization when dealing with noise-contaminated speech data, validating the effectiveness of our design in the talking head synthesis task.

5. Conclusion

This paper proposes an enhanced speech-driven facial synthesis framework, RAE-NeRF, aiming to address the instability, imprecise expression control, and suboptimal 3D reconstruction quality often encountered in existing methods under noisy speech conditions. The RAE-NeRF framework consists of three key modules: (1) the ZipEnhancer module, which effectively enhances speech clarity and provides robust audio features for subsequent processing; (2) a residual-based audio-visual encoder that introduces a residual structure to efficiently fuse audio and visual features, thereby improving expression-driving accuracy; and (3) a tri-plane hash encoder that enables high-quality 3D facial modeling and rendering while maintaining computational efficiency. Experiments on multiple datasets demonstrate that RAE-NeRF outperforms current mainstream methods in terms of realism, facial synchronization, and noise robustness. Notably, even under poor speech quality conditions, the proposed framework maintains stable and natural facial synthesis performance, showcasing strong robustness and generalization ability. Future work will explore the extension of RAE-NeRF to multi-language and diverse emotional states, and incorporate emotion recognition mechanisms to enhance the naturalness and intelligence of virtual human interactions.

References

- Thies, J.; Elgharib, M.; Tewari, A.; Theobalt, C.; Nießner, M. Neural voice puppetry: Audio-driven facial reenactment. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part XVI 16. Springer, 2020, pp. 716–731.

- Peng, Z.; Luo, Y.; Shi, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhu, X.; Liu, H.; He, J.; Fan, Z. Selftalk: A self-supervised commutative training diagram to comprehend 3d talking faces. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 2023, pp. 5292–5301.

- Kim, H.; Garrido, P.; Tewari, A.; Xu, W.; Thies, J.; Niessner, M.; Pérez, P.; Richardt, C.; Zollhöfer, M.; Theobalt, C. Deep video portraits. ACM transactions on graphics (TOG) 2018, 37, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Maddox, R.K.; Duan, Z.; Xu, C. Hierarchical cross-modal talking face generation with dynamic pixel-wise loss. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 7832–7841.

- Prajwal, K.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Namboodiri, V.P.; Jawahar, C. A lip sync expert is all you need for speech to lip generation in the wild. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th ACM international conference on multimedia, 2020, pp. 484–492.

- Zhou, Y.; Han, X.; Shechtman, E.; Echevarria, J.; Kalogerakis, E.; Li, D. Makelttalk: speaker-aware talking-head animation. ACM Transactions On Graphics (TOG) 2020, 39, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Sun, Y.; Wu, W.; Loy, C.C.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z. Pose-controllable talking face generation by implicitly modularized audio-visual representation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021, pp. 4176–4186.

- Lu, Y.; Chai, J.; Cao, X. Live speech portraits: real-time photorealistic talking-head animation. ACM Transactions on Graphics (ToG) 2021, 40, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, M.; Ni, S.; Budagavi, M.; Guo, X. Facial: Synthesizing dynamic talking face with implicit attribute learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 3867–3876.

- Guan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Hu, T.; Wang, K.; He, D.; Feng, H.; Liu, J.; Ding, E.; Liu, Z.; et al. Stylesync: High-fidelity generalized and personalized lip sync in style-based generator. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 1505–1515.

- Wang, J.; Qian, X.; Zhang, M.; Tan, R.T.; Li, H. Seeing what you said: Talking face generation guided by a lip reading expert. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 14653–14662.

- Zhang, Z.; Hu, Z.; Deng, W.; Fan, C.; Lv, T.; Ding, Y. Dinet: Deformation inpainting network for realistic face visually dubbing on high resolution video. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2023, Vol. 37, pp. 3543–3551.

- Zhong, W.; Fang, C.; Cai, Y.; Wei, P.; Zhao, G.; Lin, L.; Li, G. Identity-preserving talking face generation with landmark and appearance priors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 9729–9738.

- Peng, Z.; Hu, W.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, H.; He, J.; Liu, H.; Fan, Z. Synctalk: The devil is in the synchronization for talking head synthesis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 666–676.

- Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Bai, X.; Zhou, J.; Gu, L. Efficient region-aware neural radiance fields for high-fidelity talking portrait synthesis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 7568–7578.

- Tang, J.; Wang, K.; Zhou, H.; Chen, X.; He, D.; Hu, T.; Liu, J.; Zeng, G.; Wang, J. Real-time neural radiance talking portrait synthesis via audio-spatial decomposition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.12368 2022.

- Müller, T.; Evans, A.; Schied, C.; Keller, A. Instant neural graphics primitives with a multiresolution hash encoding. ACM transactions on graphics (TOG) 2022, 41, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, Z.; Maddox, R.K.; Duan, Z.; Xu, C. Lip movements generation at a glance. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 520–535.

- Das, D.; Biswas, S.; Sinha, S.; Bhowmick, B. Speech-driven facial animation using cascaded gans for learning of motion and texture. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part XXX 16. Springer, 2020, pp. 408–424.

- KR, P.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Philip, J.; Jha, A.; Namboodiri, V.; Jawahar, C. Towards automatic face-to-face translation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 27th ACM international conference on multimedia, 2019, pp. 1428–1436.

- Meshry, M.; Suri, S.; Davis, L.S.; Shrivastava, A. Learned spatial representations for few-shot talking-head synthesis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 13829–13838.

- Song, L.; Wu, W.; Qian, C.; He, R.; Loy, C.C. Everybody’s talkin’: Let me talk as you want. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2022, 17, 585–598. [CrossRef]

- Vougioukas, K.; Petridis, S.; Pantic, M. Realistic speech-driven facial animation with gans. International Journal of Computer Vision 2020, 128, 1398–1413. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Luo, P.; Wang, X. Talking face generation by adversarially disentangled audio-visual representation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2019, Vol. 33, pp. 9299–9306.

- Sun, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, K.; Wu, Q.; Hong, Z.; Liu, J.; Ding, E.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Hideki, K. Masked lip-sync prediction by audio-visual contextual exploitation in transformers. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH Asia 2022 Conference Papers, 2022, pp. 1–9.

- Wang, S.; Li, L.; Ding, Y.; Fan, C.; Yu, X. Audio2head: Audio-driven one-shot talking-head generation with natural head motion. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.09293 2021.

- Mildenhall, B.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Tancik, M.; Barron, J.T.; Ramamoorthi, R.; Ng, R. Nerf: Representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis. Communications of the ACM 2021, 65, 99–106. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, B.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, J.; Bai, X. Multi-view stereo in the deep learning era: A comprehensive review. Displays 2021, 70, 102102. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhou, L.; Bai, X.; Wang, C.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, J. Learning multi-view visual correspondences with self-supervision. Displays 2022, 72, 102160. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Bai, X.; Ning, X.; Zhou, J.; Hancock, E. Uncertainty estimation for stereo matching based on evidential deep learning. pattern recognition 2022, 124, 108498. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Bai, X.; Wang, C.; Huang, L.; Chen, Y.; Gu, L.; Zhou, J.; Harada, T.; Hancock, E.R. Revisiting domain generalized stereo matching networks from a feature consistency perspective. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 13001–13011.

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Bai, X.; Yu, S.; Yu, K.; Li, Z.; Yang, K. Adaptive unimodal cost volume filtering for deep stereo matching. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2020, Vol. 34, pp. 12926–12934.

- Liu, X.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, H.; Wu, W.; Zhou, B. Semantic-aware implicit neural audio-driven video portrait generation. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision. Springer, 2022, pp. 106–125.

- Ye, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Ren, Y.; Liu, J.; He, J.; Zhao, Z. Geneface: Generalized and high-fidelity audio-driven 3d talking face synthesis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.13430 2023.

- Chatziagapi, A.; Athar, S.; Jain, A.; Rohith, M.; Bhat, V.; Samaras, D. LipNeRF: What is the right feature space to lip-sync a NeRF? In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 17th International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–8.

- Kim, E.; Seo, H. SE-Conformer: Time-Domain Speech Enhancement Using Conformer. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, 2021, pp. 2736–2740.

- Kong, Z.; Ping, W.; Dantrey, A.; Catanzaro, B. Speech denoising in the waveform domain with self-attention. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2022-2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2022, pp. 7867–7871.

- Zhao, S.; Ma, B.; Watcharasupat, K.N.; Gan, W.S. FRCRN: Boosting feature representation using frequency recurrence for monaural speech enhancement. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2022-2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2022, pp. 9281–9285.

- Valentini-Botinhao, C.; Yamagishi, J. Speech enhancement of noisy and reverberant speech for text-to-speech. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing 2018, 26, 1420–1433. [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Li, A.; Zheng, C.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Dual-branch attention-in-attention transformer for single-channel speech enhancement. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2022-2022 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2022, pp. 7847–7851.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30.

- Luo, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yoshioka, T. Dual-path rnn: efficient long sequence modeling for time-domain single-channel speech separation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2020, pp. 46–50.

- Subakan, C.; Ravanelli, M.; Cornell, S.; Bronzi, M.; Zhong, J. Attention is all you need in speech separation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021-2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2021, pp. 21–25.

- Chen, H.; Yu, J.; Weng, C. Complexity scaling for speech denoising. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024-2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2024, pp. 12276–12280.

- Burchi, M.; Vielzeuf, V. Efficient conformer: Progressive downsampling and grouped attention for automatic speech recognition. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding Workshop (ASRU). IEEE, 2021, pp. 8–15.

- Kim, S.; Gholami, A.; Shaw, A.; Lee, N.; Mangalam, K.; Malik, J.; Mahoney, M.W.; Keutzer, K. Squeezeformer: An efficient transformer for automatic speech recognition. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 9361–9373.

- Yao, Z.; Guo, L.; Yang, X.; Kang, W.; Kuang, F.; Yang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Lin, L.; Povey, D. Zipformer: A faster and better encoder for automatic speech recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.11230 2023.

- Wang, H.; Tian, B. ZipEnhancer: Dual-Path Down-Up Sampling-based Zipformer for Monaural Speech Enhancement. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.05183 2025.

- Guo, Y.; Chen, K.; Liang, S.; Liu, Y.J.; Bao, H.; Zhang, J. Ad-nerf: Audio driven neural radiance fields for talking head synthesis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 5784–5794.

- Shen, S.; Li, W.; Zhu, Z.; Duan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Lu, J. Learning dynamic facial radiance fields for few-shot talking head synthesis. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision. Springer, 2022, pp. 666–682.

- Loshchilov, I. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.05101 2017.

- Roux, J.L.; Wisdom, S.; Erdogan, H.; Hershey, J.R. SDR - Half-baked or Well Done? In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2019 - 2019 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2019, pp. 626–630. [CrossRef]

- Kubichek, R. Mel-cepstral distance measure for objective speech quality assessment. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of IEEE Pacific Rim Conference on Communications Computers and Signal Processing, 1993, Vol. 1, pp. 125–128 vol.1. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A.; Shechtman, E.; Wang, O. The unreasonable effectiveness of deep features as a perceptual metric. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 586–595.

- Heusel, M.; Ramsauer, H.; Unterthiner, T.; Nessler, B.; Hochreiter, S. Gans trained by a two time-scale update rule converge to a local nash equilibrium. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30.

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Dong, C.; Qiao, Y. Ranksrgan: Generative adversarial networks with ranker for image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019, pp. 3096–3105.

- Mittal, A.; Soundararajan, R.; Bovik, A.C. Making a "completely blind" image quality analyzer. IEEE Signal processing letters 2012, 20, 209–212. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Moorthy, A.K.; Bovik, A.C. No-reference image quality assessment in the spatial domain. IEEE Transactions on image processing 2012, 21, 4695–4708. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).