Aishell-3 is a high-quality, multi-speaker Mandarin speech synthesis dataset publicly released by the AISHELL Foundation. It comprises 218 Mandarin Chinese speakers with a balanced gender distribution, making it suitable for multi-speaker modeling and voice conversion tasks. The dataset includes over 85,000 utterances with a total duration of approximately 85 hours. Recorded at a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz, 16-bit depth, in a professional studio environment, it ensures exceptional audio clarity. To construct the speech test set, we excluded 10 randomly selected speakers from the training process and randomly sampled 10 utterances per speaker, resulting in a total of 100 speech samples.

Opencpop is a dataset specifically designed for Chinese singing voice synthesis (SVS) and singing voice conversion (SVC) tasks, developed and released by the Pop Song Research Group. This dataset features the following characteristics: The recordings were captured in a professional, noise-free environment, making it highly suitable for singing research. The dataset was performed by a professional female singer to ensure clear articulation and consistent timbre. It encompasses 100 Chinese pop songs with a total duration of approximately 5.2 hours. The audio was sampled at 44.1 kHz with 16-bit PCM encoding. Word-by-word aligned lyrics annotations are provided to ensure rhythmic consistency during singing transitions. Additionally, precise pitch curves are included, facilitating accurate modeling of pitch variations. To construct the singing voice test set, we randomly selected 10 scores from the dataset that were not used in training and extracted 10 vocal segments from each score, resulting in a total of 100 singing samples.

5.2. Model Configuration

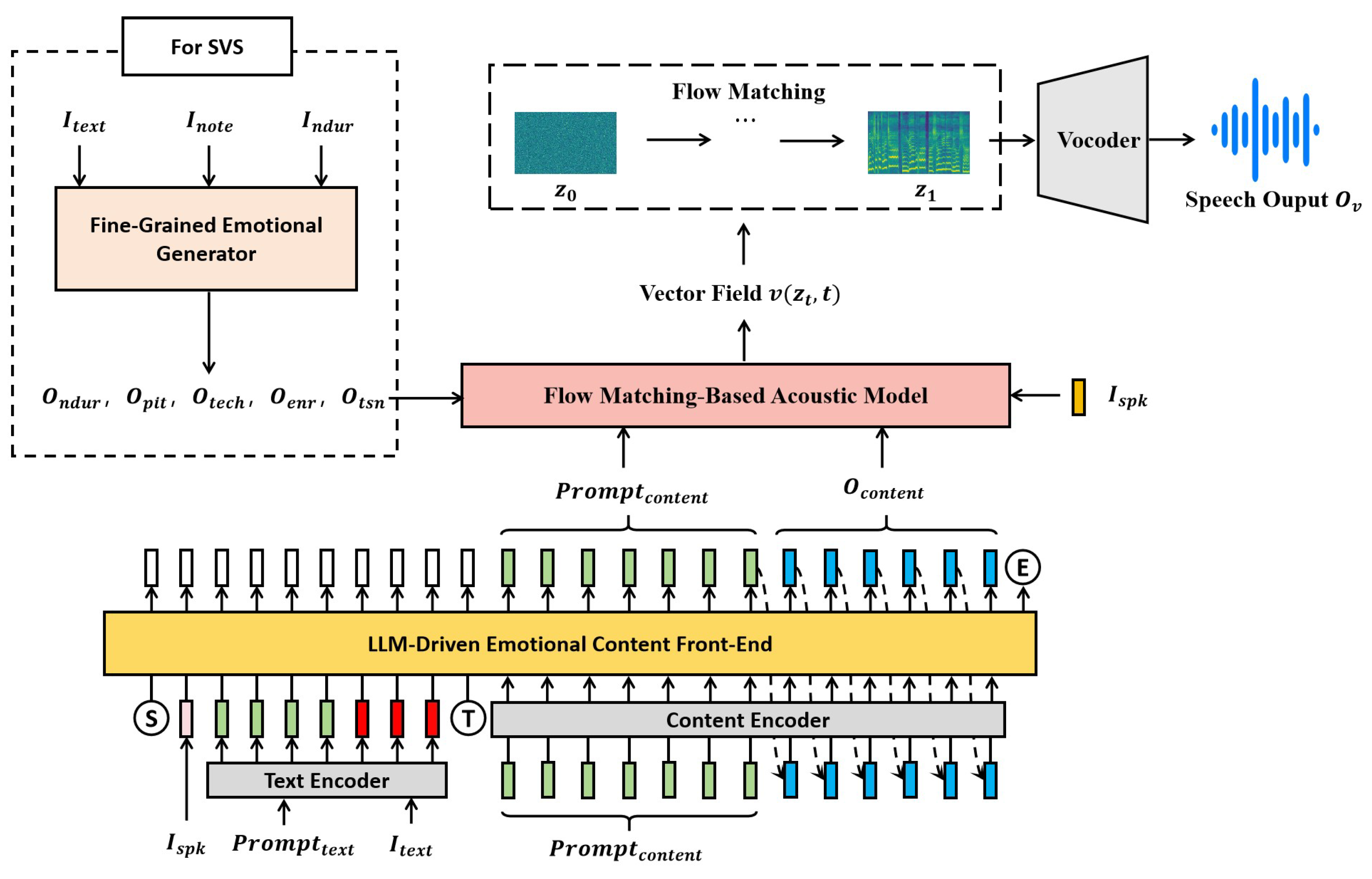

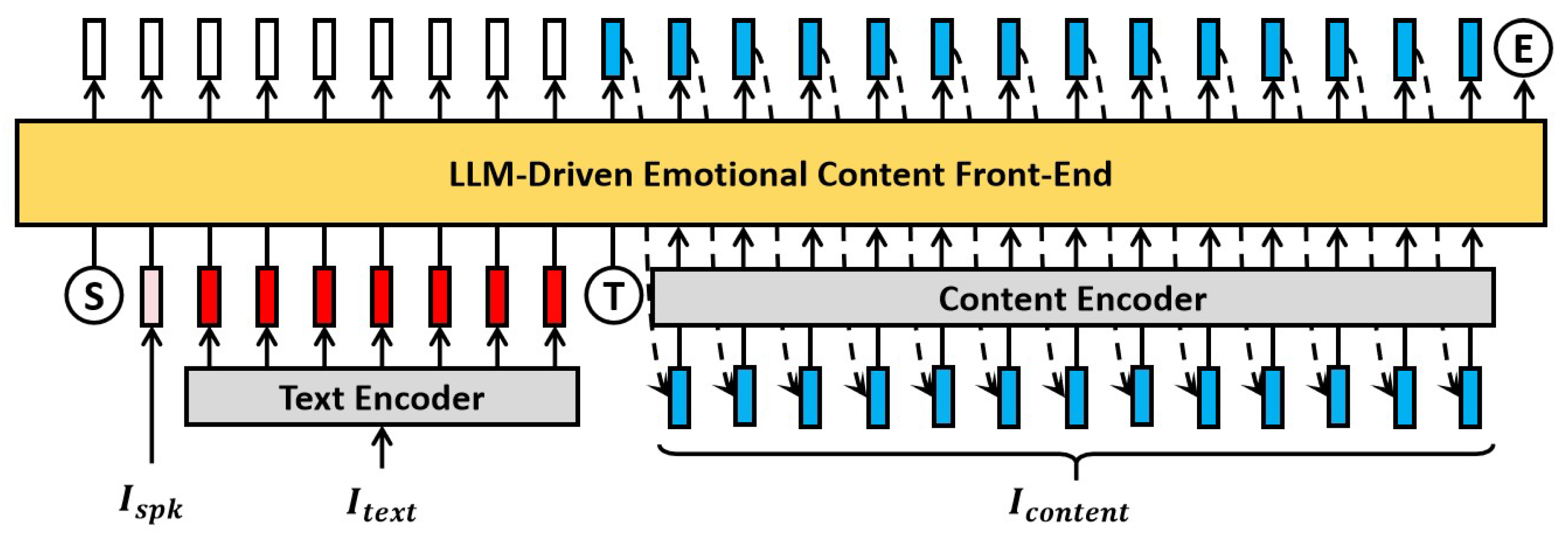

In the LLM-driven emotional content front-end, the input text has a vocabulary size of 51,866 and is first mapped to a 512-dimensional embedding. This embedding is then processed by a Transformer encoder consisting of 6 layers, 16 attention heads, a hidden dimension of 4096, and an output dimensionality of 1024, resulting in the text encoding . The input content representation is projected from 4096 to 1024 dimensions, yielding the content encoding . The input speaker embedding, originally 192-dimensional, is linearly projected to 1024 dimensions. The LLM itself adopts a Transformer encoder architecture with 14 blocks, 16 attention heads, a hidden size of 4096, and an output size of 1024. The final layer is a linear projection to a 4097-dimensional vector for predicting the one-hot encoding of the output content representation .

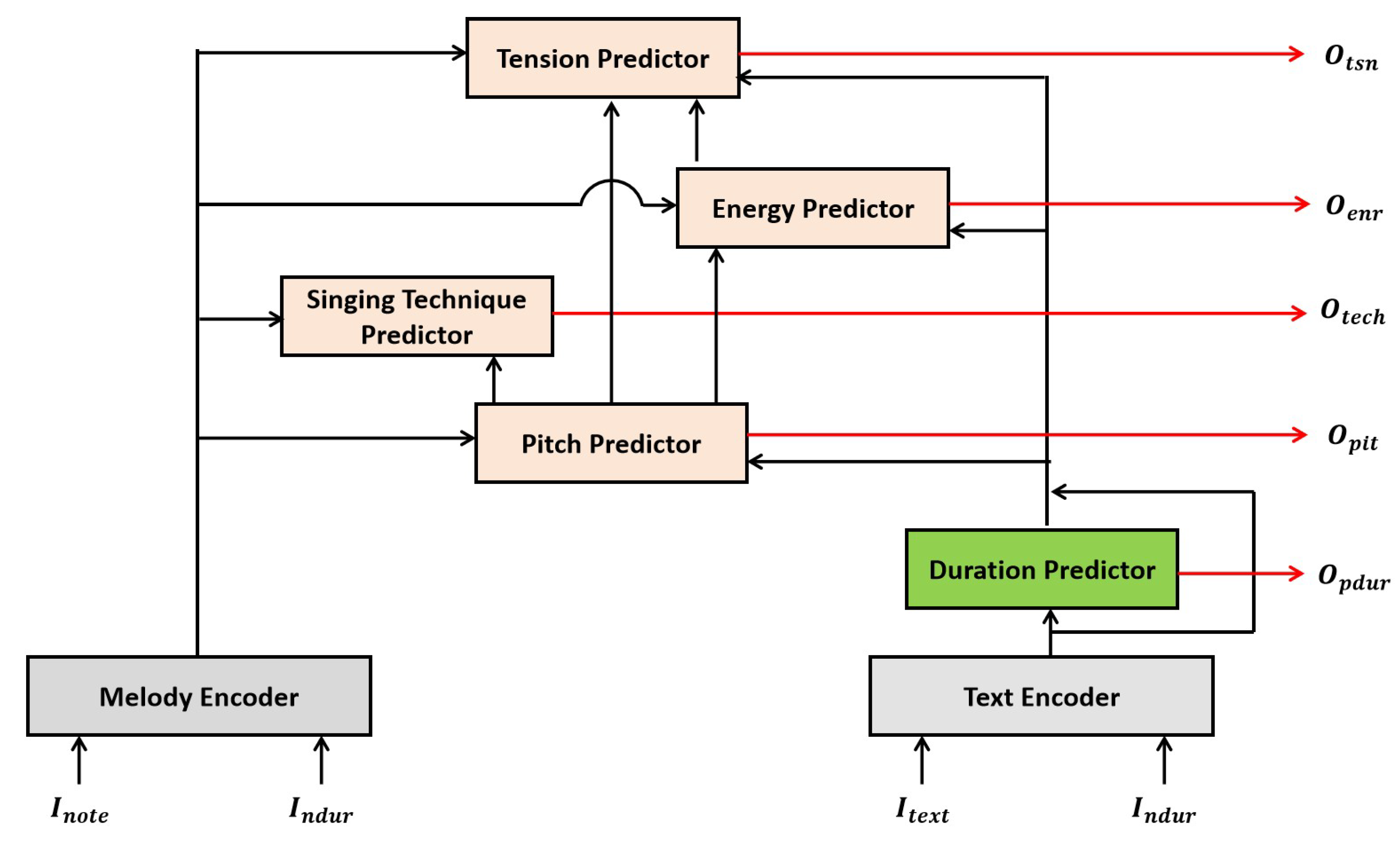

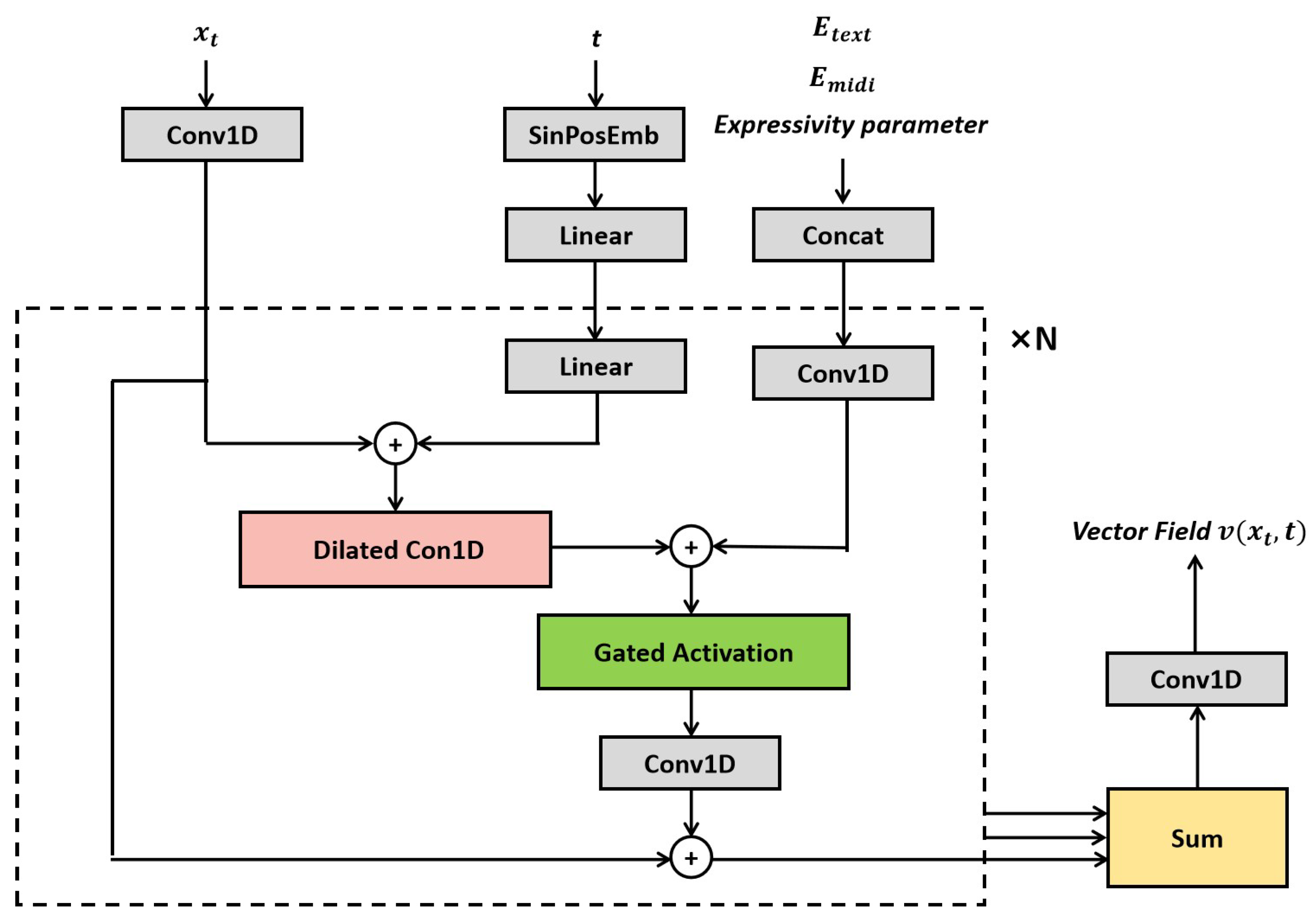

In the fine-grained singing expressiveness generator, the input text shares the same vocabulary size of 51,866 and is embedded into 256-dimensional vectors. The note input has a vocabulary size of 128 and is also embedded into 256-dimensional vectors. The note duration input is projected via a linear layer into 256 dimensions. Both the melody encoder and the text encoder adopt the same Transformer encoder structure, each consisting of 4 layers, 2 attention heads, and a hidden size of 256. The duration predictor is implemented as a single fully connected layer. The pitch predictor, singing technique predictor, energy predictor, and tension predictor are all implemented using flow matching. The underlying dilated convolutional network consists of 20 dilated convolution layers. The time step t and the flow matching distribution are first fused and projected into a 256-dimensional representation, which is then processed through the dilated convolutional layers to produce a 512-dimensional output. Expressive parameters, along with the melody encoding and the text encoding , are stacked and passed through a 1D convolutional layer to obtain a 512-dimensional hidden representation. A final convolutional layer outputs a 1-dimensional vector field .

In the flow matching-based acoustic model, the time encoding is first passed through a one-dimensional convolutional layer with an output channel size of to produce two parameters, and required for feature conditioning. The multi-head self-attention mechanism employs 4 attention heads with a hidden dimension of 400. The multilayer perceptron (MLP) consists of two linear layers, with a hidden size of 400 and an output size of , generating the conditional parameters Finally, the entire multi-dimensional perception network outputs a 100-dimensional predicted vector field through a one-dimensional convolutional layer.

5.4. Baseline Models and Evaluation Metrics

This work selects both emotional speech synthesis models and singing voice synthesis models as baselines to evaluate performance across speech and singing tasks. These baseline systems cover mainstream approaches based on variational autoencoders and diffusion models, ensuring comprehensive and scientifically rigorous comparisons.

(1) Baseline Models for Speech Synthesis:

1) VITS [

13] (ICML 2021): A classic speech synthesis model based on the variational autoencoder (VAE) architecture. It is widely adopted in TTS tasks for its efficient feature modeling capabilities.

2) Mixed Emotion TTS [

22] (IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 2022): A TTS model incorporating mixed emotional embeddings to improve emotional expressiveness.

3) EmoDiff [

23] (ICASSP 2023): An emotional speech synthesis method based on diffusion models, enabling expressive generation through emotion-aware denoising processes.

(2) Baseline Models for Singing Voice Synthesis:

1) Visinger [

25] (ICASSP 2022): A singing voice synthesis model based on the VITS architecture, using a variational autoencoder framework for high-quality singing waveform generation.

2) Diffsinger [

26] (AAAI 2022): A diffusion-based singing synthesis model that progressively denoises latent representations to generate high-fidelity singing audio.

3) ComoSpeech [

19] (Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 2023): A state-of-the-art diffusion-based singing synthesis approach. It preserves high-frequency details and formant features during the generation process through a carefully designed denoising schedule, resulting in more natural and perceptually clearer singing output.

(3) Evaluation index:

1) Mean Opinion Score (MOS): A subjective evaluation metric that measures the naturalness of synthesized speech. Scores are provided by 10 native Mandarin speakers with good pitch perception.

2) Mel Cepstral Distortion (MCD): An objective metric that calculates the spectral distance between the converted speech and the target speech. Lower values indicate better conversion quality.

3) Word Error Rate (WER): Evaluates speech intelligibility by using an automatic speech recognition (ASR) system. Lower WER values indicate better intelligibility.

4) Speaker Mean Opinion Score (SMOS): A subjective measure of speaker similarity between converted and target speech. Evaluated by the same 10 Mandarin-speaking listeners, it reflects perceived voice timbre similarity.

5) Speaker Embedding Cosine Similarity (SECS): An objective metric based on cosine similarity between speaker embeddings of original and converted speech. Higher scores indicate better speaker identity preservation.

6) Variance Mean Opinion Score (VMOS): A subjective evaluation metric that assesses the emotional expressiveness of synthesized speech. Scores are provided by 10 listeners who are native Mandarin speakers with good pitch perception, aiming to evaluate how well the emotional content is conveyed in the synthesized speech.

7) Emotion Embedding Cosine Similarity (EECS): An objective metric based on the emo2vec [

39] emotional embedding model. It computes the cosine similarity between the emotion vectors of the synthesized speech and the target speech. Higher values indicate better emotional consistency and preservation.

8) F0 Pearson Correlation (FPC): This metric calculates the Pearson correlation coefficient between the pitch contours of the target and synthesized speech, measuring the pitch retention capability of the system. It is defined as:

where

and

denote the pitch trajectories of the target and synthesized speech, respectively. A correlation coefficient

indicates perfect pitch alignment (melodic consistency),

indicates no correlation, and

indicates an inverse correlation, implying extreme pitch mismatch.

5.5. Experimental Results

(1) Speech Synthesis

1) Speech Quality Evaluation

The primary objective of speech synthesis is to generate speech that is natural, clear, and expressive, achieving high-quality standards in terms of naturalness, timbre consistency, and intelligibility. To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed highly expressive speech synthesis system, we conducted experiments on a speech test set and assessed the results using MOS, MCD, and WER metrics.

As shown in

Table 1, the proposed LLFM-Voice significantly outperforms baseline models in speech quality, achieving the best results in both MOS (4.12) and WER (3.86%). Compared to VITS, LLFM-Voice leverages the contextual learning capability of large language models to more accurately model the relationship between text semantics and speech content, resulting in smoother and more natural synthesized speech. Additionally, the autoregressive emotional embedding employed in LLFM-Voice enables smoother emotional transitions across the speech sequence, further enhancing the naturalness of emotional expression. Compared to Mixed Emotion TTS, LLFM-Voice shows clear improvements in both MCD and WER. This demonstrates that autoregressive modeling with large language models can more precisely predict phonetic features, ensuring speech clarity and avoiding the phoneme blurring issues often caused by static emotional embeddings. Compared with EmoDiff, LLFM-Voice also yields superior results in MCD and WER. Although EmoDiff utilizes diffusion models to enhance emotional expressiveness, its denoising process may cause phoneme oversmoothing, which compromises clarity and fine-grained control of emotional variation. In contrast, LLFM-Voice, driven by a large language model-based content front-end, more effectively models prosody, rhythm, and dynamic emotional changes in speech, thereby significantly enhancing the expressiveness of the synthesized output.

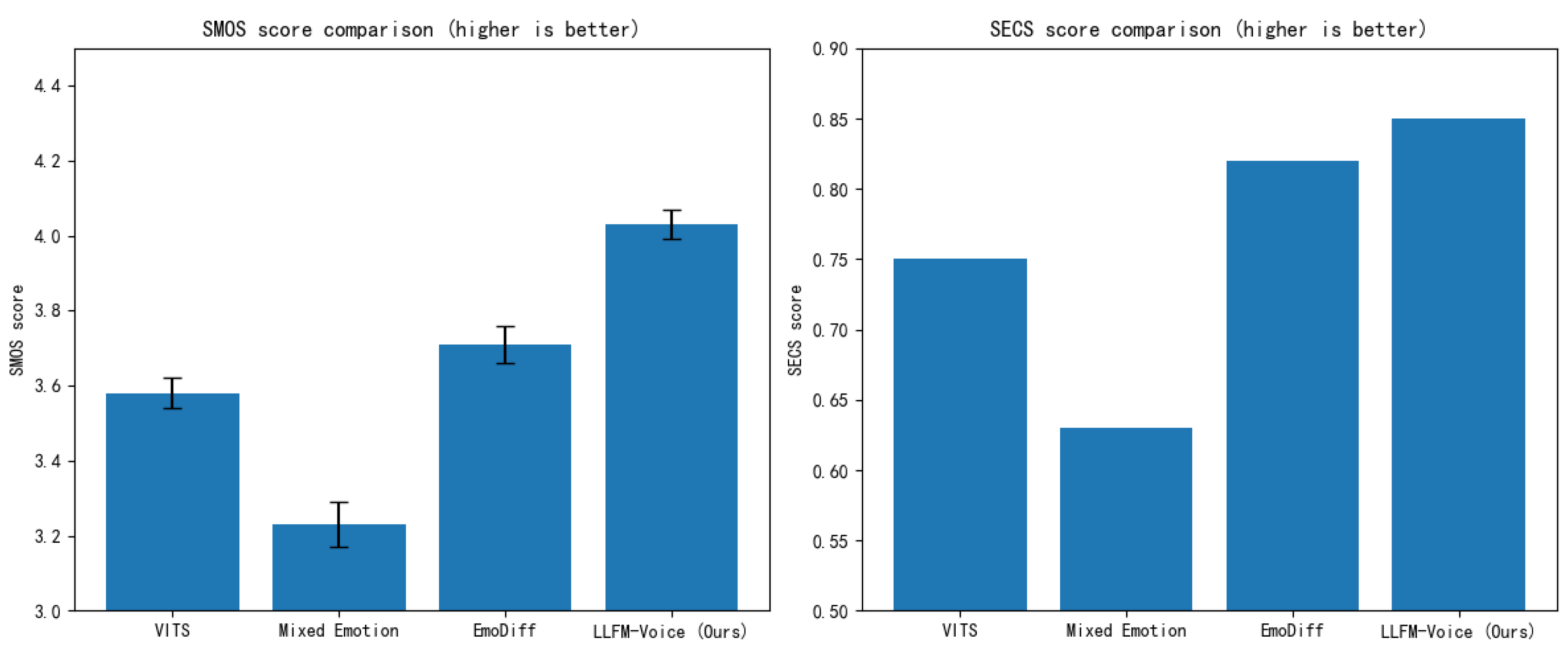

2) Speech Timbre Similarity Evaluation

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of different speech synthesis methods in terms of speaker timbre preservation, we utilize two metrics: Speaker Mean Opinion Score (SMOS) and Speaker Embedding Cosine Similarity (SECS).

As shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 8, LLFM-Voice demonstrates outstanding performance in both SMOS (4.03) and SECS (0.85), significantly outperforming VITS and Mixed Emotion TTS, and achieving speaker similarity scores comparable to EmoDiff. These results indicate that LLFM-Voice, through autoregressive modeling powered by a large language model, can more accurately predict speaker timbre features, producing synthetic speech that closely resembles the target speaker’s voice. Compared to VITS, LLFM-Voice shows substantial improvements in both SMOS and SECS, suggesting that VITS, which relies solely on a variational autoencoder to model timbre, may suffer from timbre blurring or loss of speaker individuality. In contrast, LLFM-Voice benefits from the contextual representation learned by the large language model, which effectively enhances speaker identity consistency. Relative to Mixed Emotion TTS, LLFM-Voice achieves a significant advantage in the SECS metric. This implies that traditional methods based on static emotional embeddings have limitations in timbre control and struggle to preserve speaker-specific characteristics. LLFM-Voice, by employing an autoregressive mechanism, allows the synthesized speech to gradually inherit the target speaker’s timbre features, thus improving stability and speaker fidelity. Compared to EmoDiff, LLFM-Voice yields a higher SMOS and slightly better SECS. Although EmoDiff, as a diffusion-based model, can improve speaker similarity to some extent, its denoising process may result in the loss of fine-grained timbre details, thereby affecting overall clarity. LLFM-Voice, on the other hand, leverages the semantic understanding and emotional embedding capabilities of large language models to maintain more natural and consistent timbre, while also delivering better subjective perceptual quality.

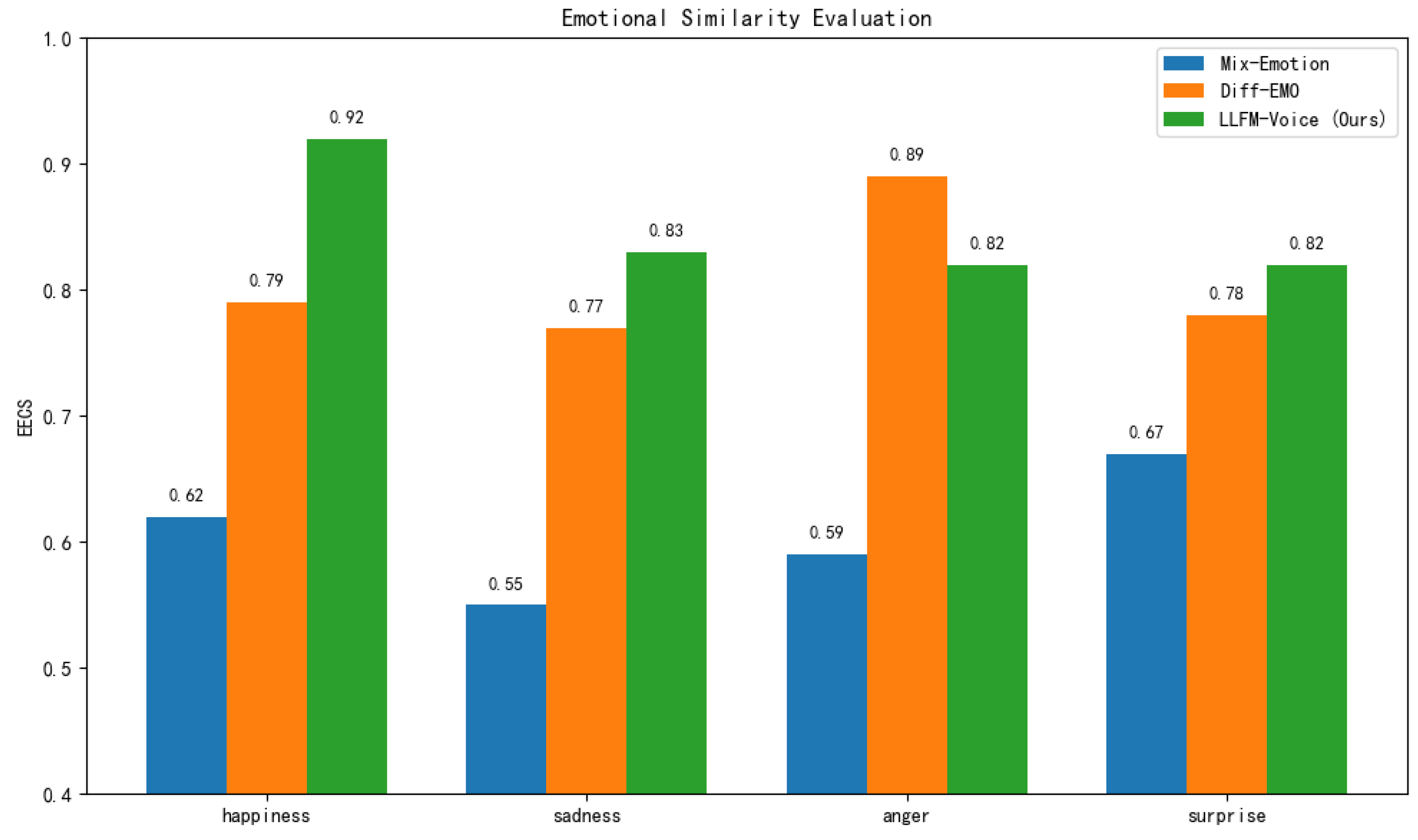

3) Emotional Similarity Evaluation

To evaluate the emotional expressiveness of different speech synthesis methods, we generated and assessed 100 synthesized utterances for each of four primary emotion categories: happiness, sadness, anger, and surprise. The textual content of each utterance was carefully designed to align with the target emotion. The Emotion Embedding Cosine Similarity (EECS) metric was used to measure emotional accuracy by calculating the cosine similarity between the emotional embedding of the synthesized speech and that of the target emotion. A higher EECS value indicates better emotional alignment.

As shown in

Table 3 and

Figure 9, LLFM-Voice outperforms both Mix-Emotion and Diff-EMO across all emotion categories, achieving the highest EECS scores. This demonstrates that LLFM-Voice possesses more accurate emotional modeling capabilities and can generate speech that more closely reflects the intended emotional state. Compared to Mix-Emotion, LLFM-Voice shows substantial improvements in all categories. This suggests that traditional methods relying on mixed emotional embeddings face limitations in controlling emotional intensity and dynamic variation, often resulting in flat or less expressive synthesized speech. In contrast, LLFM-Voice benefits from the contextual modeling strength of large language models, enabling more precise prediction of emotional cues and producing speech with more natural intensity and expressive detail. When compared to Diff-EMO, LLFM-Voice performs better in the categories of happiness, sadness, and surprise, while slightly underperforming in the anger category. This implies that diffusion models may hold certain advantages in modeling extreme or highly intense emotions. However, the denoising process inherent to diffusion models may lead to the loss of subtle emotional details, affecting the overall stability of emotional expression. LLFM-Voice, driven by the autoregressive learning capacity of large language models, is able to capture the dynamic evolution of emotion within context, resulting in smoother and more natural emotional transitions in the synthesized speech.

(2) Singing Voice Synthesis

1) Singing Voice Quality Evaluation

To comprehensively evaluate the quality of synthesized singing voices, we adopt three metrics: MOS, MCD, and WER, which respectively assess perceptual quality, timbre fidelity, and intelligibility.

As shown in

Table 4, LLFM-Voice achieves the best performance across all evaluation metrics. It obtains the highest MOS (4.18), and also surpasses all baseline models in MCD (5.23) and WER (5.87%), demonstrating its ability to generate singing voices with higher audio fidelity, clarity, and naturalness, while improving overall intelligibility. Compared to Visinger, LLFM-Voice shows significant improvements on all metrics. This indicates that although the VITS-based Visinger can effectively learn the mapping between phonemes and acoustic features, it still struggles with capturing expressive nuances, maintaining timbre stability, and handling detailed control. In contrast, LLFM-Voice benefits from a large language model-driven autoregressive content front-end, which enhances semantic-acoustic alignment and results in more naturally expressive and fluent singing voices. Compared to Diffsinger, LLFM-Voice also outperforms in MOS, MCD, and WER. While diffusion models like Diffsinger improve perceptual quality through progressive denoising, they may introduce artifacts or timbre distortion, especially in melodic segments with significant pitch variation. LLFM-Voice addresses this limitation by employing hierarchical modeling of expressive features, allowing dynamic adjustment of energy, pitch, and vocal techniques in response to melodic changes, thereby improving both quality and intelligibility. When compared to ComoSpeech, LLFM-Voice achieves better MOS and MCD scores, though it shows a slightly higher WER. This suggests that ComoSpeech, with its diffusion probabilistic modeling, has advantages in modeling high-frequency details and formant structures, contributing to clearer audio quality. However, its longer iterative inference process may introduce instability, which can negatively affect lyric intelligibility. LLFM-Voice, by integrating the semantic modeling capability of large language models with fine-grained control of singing expressiveness, ensures high-quality synthesis while improving the coherence and emotional layering of the singing voice, thus offering a superior overall listening experience.

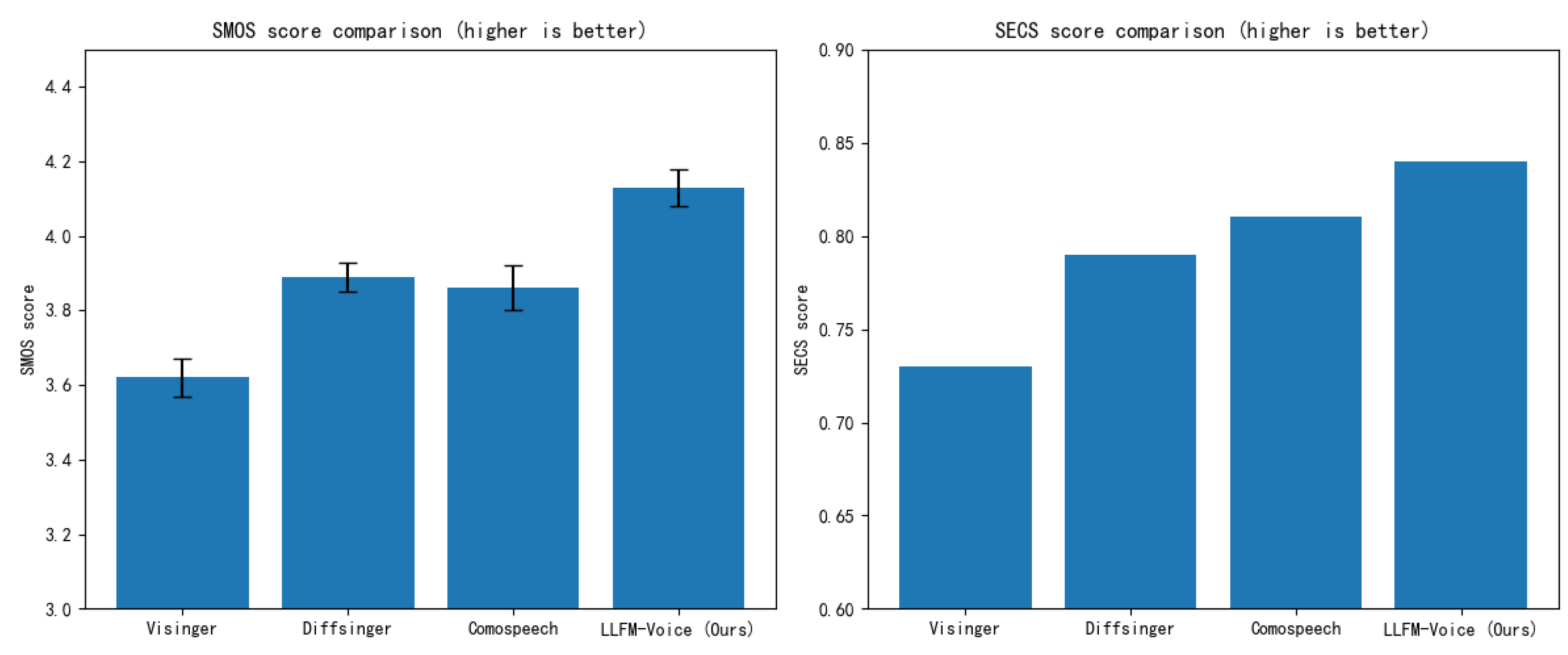

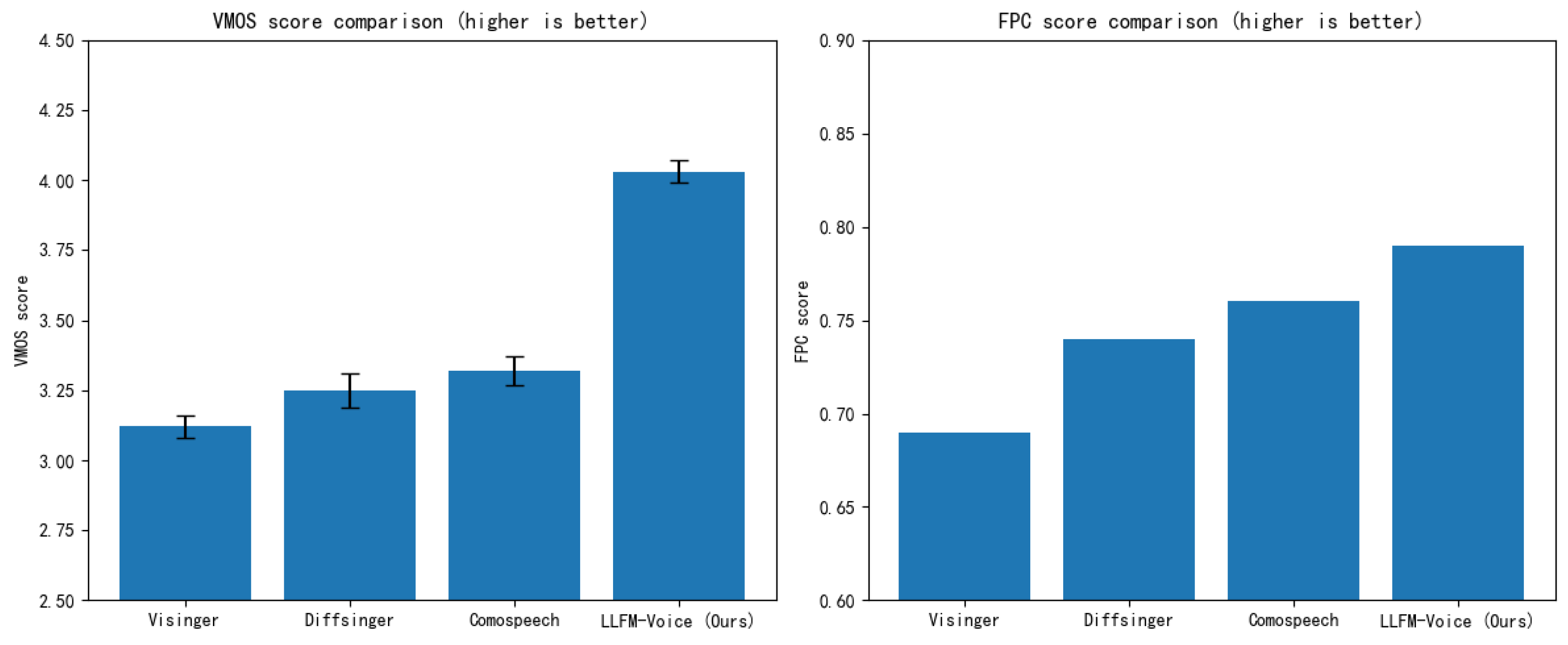

2) Singing Voice Timbre Similarity Evaluation

To evaluate the timbre consistency of different singing voice synthesis methods, we adopt two core metrics: Speaker Mean Opinion Score (SMOS) and Speaker Embedding Cosine Similarity (SECS).

As shown in

Table 5 and

Figure 10, LLFM-Voice achieves the best performance in both SMOS (4.13) and SECS (0.84), demonstrating superior timbre preservation capabilities compared to all baseline methods. Compared to Visinger, LLFM-Voice shows substantial improvements in both SMOS and SECS. This suggests that while Visinger, built on the VITS architecture, can capture acoustic features, it struggles with timbre stability, especially over long singing sequences, where timbre drift may occur. In contrast, LLFM-Voice leverages an autoregressive content front-end combined with fine-grained emotional control, allowing the synthesized timbre to remain consistent throughout extended singing passages and across variations in pitch and rhythm. When compared to Diffsinger, LLFM-Voice outperforms in SECS, indicating that diffusion models may suffer from timbre degradation during the denoising process. The stochastic nature of diffusion sampling may also introduce timbre variance, resulting in less stable vocal output. LLFM-Voice, on the other hand, benefits from semantically grounded modeling powered by large language models, which strengthens the alignment between text, melody, and vocal timbre, leading to improved consistency. Relative to ComoSpeech, LLFM-Voice achieves a higher SMOS score, though the improvement in SECS is marginal. This suggests that ComoSpeech, based on DDPM-style progressive denoising, has certain advantages in preserving fine-grained timbre details. However, its diffusion process may introduce nonlinear distortions, leading to slightly reduced subjective timbre consistency. By contrast, LLFM-Voice employs hierarchical modeling of expressive features, allowing the synthesized timbre to adapt more naturally to pitch and prosodic changes while better matching the target voice, thus enhancing the perceived timbre coherence.

3) Evaluation of Emotional Expressiveness in Singing Voice Synthesis

To assess the emotional expressiveness of different singing voice synthesis methods, we adopt two key metrics: Variance Mean Opinion Score (VMOS) and F0 Pearson Correlation (FPC).

As shown in

Table 6 and

Figure 11, LLFM-Voice achieves the best performance on both VMOS (4.03) and FPC (0.79), demonstrating its ability to generate singing voices that are not only natural but also rich in emotional expressiveness. Compared to Visinger, LLFM-Voice shows significant improvements in both metrics. While Visinger, based on the VITS architecture, can generate clear singing audio, it exhibits limitations in expressive control, particularly when handling highly dynamic emotional transitions. In contrast, LLFM-Voice leverages an autoregressive content front-end, enabling dynamic adjustments of pitch, rhythm, and energy throughout long-form singing sequences, resulting in more accurate emotional portrayal. Relative to Diffsinger, LLFM-Voice also shows marked improvements in both VMOS and FPC. Although diffusion models can retain some emotional cues during the denoising process, their non-autoregressive architecture often leads to discontinuities in emotional progression, resulting in rigid transitions. LLFM-Voice, with its context-aware modeling capability powered by a large language model, ensures smoother emotional flow and more natural expressiveness in synthesized singing. When compared to ComoSpeech, LLFM-Voice demonstrates a more noticeable gain in VMOS, while the improvement in FPC is relatively modest. This suggests that ComoSpeech, using DDPM-based progressive denoising, excels in preserving detailed acoustic features and prosodic stability. However, its pitch variation tends to be relatively flat, limiting its ability to express dynamic emotional changes. In contrast, LLFM-Voice employs hierarchical modeling of expressive singing features, allowing finer control over pitch, vocal techniques, energy, and tension, thereby enhancing emotional depth and dynamic variation in synthesized singing.

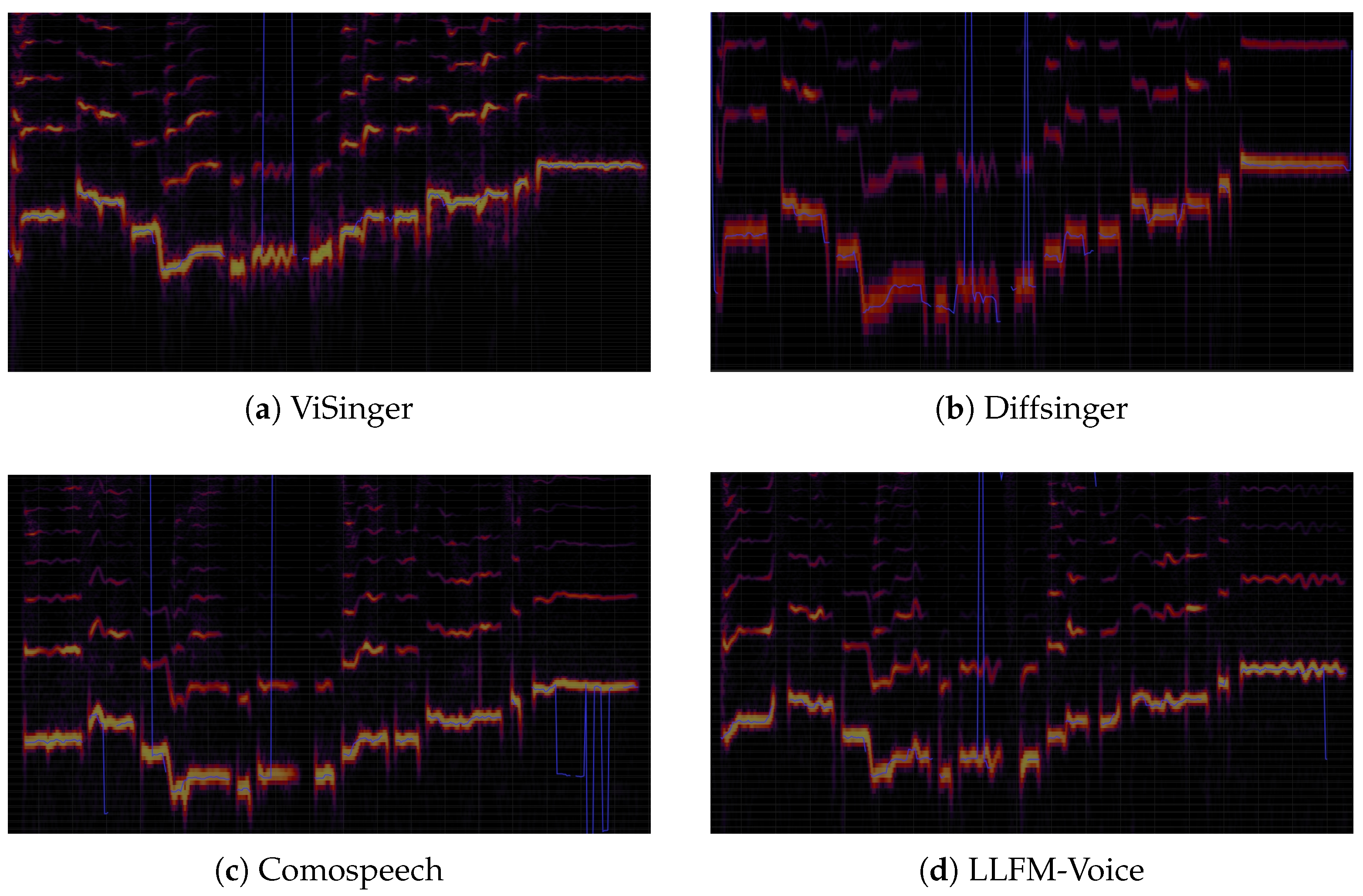

As illustrated in

Figure 12, we further analyzed the pitch contour of generated singing voices. LLFM-Voice is capable of producing vibrato with natural tremolo characteristics during sustained notes, as well as appropriate melodic ornaments such as pitch slides and turns, based on emotional semantics. Thanks to the contextual modeling of the large language model, the system achieves smooth pitch transitions between phonetic units. In contrast, Visinger and ComoSpeech, despite offering some level of pitch control, lack musical expressiveness in the form of ornamental techniques like vibrato or pitch transitions. Diffsinger can synthesize vibrato in certain segments, but its lack of strong contextual continuity often leads to abrupt transitions.